Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association of vitamin D intake with dyslipidaemia and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in Brazilian children and identify the main food group sources of this nutrient in the sample.

Design

A cross-sectional study carried out with a representative sample. Blood was collected after 12 h of fasting. Laboratory tests were performed to determine total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL cholesterol, TAG, apoB, apoA1, 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone. Dietary intake was evaluated by a 24 h recall.

Setting

Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Subjects

Children between 8 and 9 years old enrolled in urban schools (n 378).

Results

We found an elevated prevalence of inadequate vitamin D intake (91·3 %), dyslipidaemia (72·8 %) and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency (56·2 %). The food groups that contributed the most to vitamin D intake were dairy products and fish. Lower vitamin D intake was associated with increased prevalence of both low HDL-C (prevalence ratio=2·51; 95 % CI 1·02, 6·18; P<0·05) and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency (prevalence ratio=1·61; 95 % CI 1·01, 2·58; P<0·05).

Conclusions

Given the elevated prevalence of inadequate vitamin D intake and its association with low HDL-C and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency, it is important to develop specific actions in food and nutritional education as well as programmes that stimulate and facilitate access to vitamin D food sources, such as dairy products and fish.

Keywords: Micronutrients, Nutritional Deficiency, Dyslipidaemia, Dairy products, Fish

Vitamin D is a pro-hormone whose activated metabolite regulates bone, Ca and P metabolism( 1 ). The main source of this vitamin is endogenous synthesis through the skin in response to solar UVB radiation. It may also be obtained from foods (dairy products, eggs, cold-water fish, mushrooms), supplements and food fortification( 2 , 3 ).

During childhood, vitamin D effects on bone are especially obvious( 4 ), but vitamin D is also linked to lower risk of infections and allergies( 5 ), type 1 diabetes mellitus( 6 ), hypertension( 7 ) and obesity( 8 ). In 2011, the Institute of Medicine established the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) of 10 μg vitamin D/d (400 UI/d) and the RDA of 15 μg vitamin D/d (600 UI/d) for ages 1 to 70 years( 9 ). These recommendations consider only the maintenance of bone health and do not address the prevention of cardiometabolic and autoimmune illnesses( 9 ).

Vitamin D deficiency is considered a global public health problem, with high prevalence in different age groups, even in low-latitude countries where more UVB radiation is available( 10 ). Studies in Brazil, a country close to the equator, have shown that the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency varies between 67·9 %( 11 ) and 90·6 %( 12 ) in children and adolescents. This scenario, observed already in childhood, may be due to the little time spent in outdoor activities, use of sunscreens and low consumption of foods rich in vitamin D( 13 , 14 ).

Insufficient vitamin D intake is common in the child population. Studies from Europe and North America have shown high prevalence of consumption below the EAR( 15 , 16 ). The identification of the main food sources of vitamin D in Brazil may contribute to specific public health interventions for children and their families. Despite knowing the importance of consuming these food sources, there is no consensus on the association between vitamin D intake and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration( 13 , 15 , 17 ).

As the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency has increased, the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors such as alterations in lipid profile has increased in the paediatric population( 18 ). In Brazilian children and adolescents, the prevalence of dyslipidaemia varies between 29·7 %( 19 ) and 66·7 %( 20 ). Studies with children and adolescents have shown associations between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and lipid profile markers( 21 , 22 ). Nevertheless, the relationship between vitamin D intake and these markers has not been confirmed in the literature, especially in children( 23 ).

In this context, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the association of vitamin D intake with lipid profile markers and serum 25(OH)D concentration in Brazilian children, as well as to identify main groups of food sources for vitamin D in this population. Our hypothesis is that low vitamin D intake is associated with a worse lipid profile and lower serum 25(OH)D concentration already in childhood.

Methods

Study and population design

The present study was a cross-sectional study of a representative sample of children between 8 and 9 years of age enrolled in public and private schools in the urban area of Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The city is in the Zona da Mata region of Minas Gerais (latitude 20°45′14″S, longitude 42°52′55″W), with a population of 72 220, of whom 93·2 % live in the urban area, and a Human Development Index of 0·775( 24 ). In 2015, the city had seventeen public schools and seven private schools for children aged from 8 to 9 years.

The 8–9-year-old age group comprises prepubescent children, wherein it is likely already to find cardiometabolic alterations that extend into adulthood( 25 ).

The study is part of the Survey of Health Assessment of Schoolchildren (PASE), which aimed to evaluate cardiovascular health of children in the city of Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Sampling

The sample size was calculated using the software Epi Info version 7.2 from the total number of children aged 8 and 9 years (n 1464) enrolled in all urban schools in 2015. Considering the analysis of multiple outcomes, the sample was calculated on the basis of 50 % prevalence, 5 % error tolerated, 95 % CI, 5 % significance level and 20 % dropout rate, resulting in the sample size of 366 children.

The schoolchildren were selected by stratified random sampling. The sample from each school met the proportionality ratio of students enrolled by age and sex. The selection of children was done by random simple draw until the necessary number for each school was completed.

After selection, the children’s guardians were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the study. The objectives and methodology of the study were then explained to the guardians and a first meeting was arranged. At this time, the steps were discussed and those who would like to participate signed an informed consent form.

Children were excluded from the study if they had health problems which affected their nutritional state or body composition; chronic use of medication that affected the metabolism of vitamin D (corticoids, anticonvulsants, antifungals), glucose and/or lipids; and use of vitamin and mineral supplements for the last three months. When the guardians could not be contacted after three attempts, they were also excluded.

A pilot study was made with 10 % of the sample (n 37), including children aged 8–9 years enrolled in a school selected randomly. These children did not participate in the final sample. The pilot study was carried out to test the questionnaires.

Covariables

A semi-structured questionnaire eliciting socio-economic and demographic information, such as age, sex, skin colour, area of residence, school type, income per capita, mother’s age and education, was applied. Income per capita and mother’s age and education were classified according to the sample median. The guardians declared their children’s ethnicity according to the race/skin colour categories used by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics( 26 ). The presence of maternal and paternal dyslipidaemia was self-reported in a semi-structured questionnaire.

A questionnaire about lifestyle, which was developed in another study( 27 ) with the same study population as ours, was applied to estimate screen time per day (hours spent watching television, playing video games, using cell phones, computers, etc.). Sedentary behaviour was classified as screen time more than 2 h/d( 28 ).

The season of study was that of blood sampling. Sun exposure was evaluated by using reports of time the child spent in outdoor activities like walking to school or playing in the backyard or on the street.

Anthropometry and body composition evaluation

Weight and height were measured by a standard and regularly standardized methodology( 29 ) using respectively a digital electronic scale (Tanita® model BC 553, Arlington Heights, IL, USA), with 150 kg capacity and 100 g accuracy, and a 2 m portable vertical stadiometer (Alturexata®, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) scaled in millimetres. These values were used to calculate the children’s BMI (=[(body mass (kg)]/[height (m)]2).

The body composition of the children was evaluated by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar Prodigy Advance; GE Medical Systems Lunar, Milwaukee, WI, USA) to obtain body fat. These examinations were carried out in the morning after an overnight fast at the sector of Image Diagnosis of the Federal University of Viçosa’s Health Division by a specially trained technician. During the exam, the children were in a supine position until data were collected, wearing light clothes without any metal accessories.

Biochemical analysis

Blood tests were performed after 12 h of fasting at the Laboratory of Clinical Analysis of the Federal University of Viçosa. The samples were collected by venepuncture and the serum separated was stored in 1·5 ml Eppendorf tubes at −80°C for biochemical profile measurements, including lipid profile (total cholesterol (TC), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), TAG), apolipoproteins (apoB and apoA1), 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), glucose and insulin.

The lipid profile and glucose were determined with the enzymatic colorimetric method, using the commercial kit Bioclin® (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) and measured using automatic analysing equipment (BS-200 Mindray®, Nanshan, China) at the Laboratory of Clinical Analysis at the Department of Nutrition and Health at the Federal University of Viçosa. The corresponding kits were used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

ApoB and apoA1 were determined using the kinetic nephelometry method (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) and classified according to the 90th percentile of the sample because of the lack of specific cut-off points for children. Therefore, the apoB:apoA1 ratio was calculated using the 90th percentile of the sample as cut-off point.

25(OH)D, PTH and insulin were determined by the chemiluminescence immunoassay method at the Brazil Diagnosis Laboratory. 25(OH)D was obtained by the ARCHITECT® (Abbott Diagnostics, Lake Forest, IL, USA) 25-OH Vitamin D test with a correlation coefficient of ≥0·80 for serum samples when compared with the LIAISON® (DiaSorin, Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) 25-OH Vitamin D Total test and with a cumulative within- and between-assay variance of ≤10 %. The Access® Intact PTH test (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) was used for PTH. Serum insulin was measured by the Elecsys Insulin® test (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with detection limit of 0·200–1·000 μU/ml.

The classification of lipid profile components was made according to the update of the Brazilian directives on dyslipidaemias and atherosclerosis prevention of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology( 30 ).

The concentration of 25(OH)D was expressed in ng/ml (1 ng/ml=2·5 nmol/l) and defined as deficiency (<20 ng/ml), insufficiency (≥20–<30 ng/ml) and sufficiency (≥30 ng/ml)( 31 ).

Fasting values of glucose and insulin were used to calculate the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index, obtained by the formula: {[fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mmol/ml)]/22·5}( 32 ).

Dietary evaluation

Food consumption was evaluated by three 24 h dietary recalls on three non-consecutive days, one of these tests being made at the weekend. The children responded to the food questionnaire with their guardians, preferentially with the guardian directly involved with the child’s diet. For children who ate at school, researchers collected information from the child and completed it with data from the school when necessary. The number of daily meals was obtained with the 24 h dietary recall. In order to help children and guardians to determine portion sizes, we used household utensils and a photo album of utensils and different portions of foods( 33 ).

The analysis of dietary data was carried out with Diet Pro® 5i software version 5.8. Intakes of vitamin D and energy were evaluated. Due to different preparation habits and addition of sugar, salt and soya oil, some foods had a chemical composition different from their nutritional facts. These new values were computed with recipes standardized by the team, nutrition fact labels and food database tables. The Food Database: Support for Nutritional Decisions( 34 ) was used.

The adequacy of vitamin D intake was compared with the EAR of 10 µg vitamin D/d (400 UI/d)( 9 ). Adjustments were made for intra-individual variability as proposed by Willett( 35 ).

The main food sources of vitamin D were grouped into dairy products, eggs and fish, according to the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population (2006)( 36 ), and expressed as grams. The medians of consumption of these food groups were used for the analyses.

To control for the effect of energy consumption on the nutrients evaluated, we used the residual method proposed by Willett and Stampfer( 37 ).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Stata statistical software package version 13.0. The continuous variables were tested for normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample by socio-economic, demographic, lifestyle, food consumption, lipid profile and 25(OH)D status variables. Means and standard deviations were used for parametric variables, and median and interquartile ranges were used for non-parametric variables. Categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage.

The association between categorical variables was examined by Pearson’s χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences between two independent groups were evaluated by Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney test. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were obtained to evaluate the correlation of vitamin D intake with lipid profile markers and serum 25(OH)D concentration.

Stepwise multiple regression was applied to identify the main food groups that predicted the consumption of vitamin D( 35 ).

Bivariate analysis was carried out using Poisson regression with robust variance, with lipid profile and 25(OH)D status as dependent variables and dietary intake of vitamin D as the explanatory variable. The model that tested the association between vitamin D intake and lipid profile was adjusted for the following variables: age, sex, income per capita, BMI, maternal and paternal dyslipidaemia, sedentary behaviour and number of daily meals. On the other hand, the model that tested the association between vitamin D intake and 25(OH)D status was adjusted for age, sex, income per capita, skin colour, sun exposure, season, PTH, body fat percentage, HOMA-IR and maternal education. Using the backward procedure, the predictor variables that reached P value smaller than 20 % (P<0·20) were inserted into the Poisson regression with robust variance. From the complete model, the variable that contributed least (largest P value) was removed. The procedure was repeated until all the variables present in the model had statistical significance (P<0·05). The goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate the adjustment of the final model. We considered the group with vitamin D intake ≥10 μg/d as reference. The prevalence ratio (PR) with 95 % CI was used as an effect value. For all tests performed, the significance was defined as P<0·05.

Ethical aspects

The study was conducted according to the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee in Research on Humans of the Federal University of Viçosa (protocol: 663.171/2014). It was also approved by the Municipal Secretariat of Education, by the Regional Education Superintendent and by the school boards.

Results

At the end of the data collection, 4·2 % of the survey respondents were excluded due to the non-accomplishment of all stages of the research. A sample of 378 children was assessed, most being girls (52·1 %), non-black (88·6 %), urban residents (98·4 %) and from public schools (70·9 %). A high prevalence of inadequate vitamin D intake was observed (91·3 %). A lower intake of vitamin D was found for girls, those who had fewer than five meals per day and those whose consumption of dairy products and fish was below the sample median (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vitamin D intake according to sociodemographic, lifestyle and food consumption characteristics of urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

| Vitamin D intake (µg/d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | Median | IQR | P value |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 181 | 47·9 | 2·33 | 0·84–5·26 | 0·024* |

| Female | 197 | 52·1 | 1·77 | 0·42–4·03 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 8 | 183 | 48·4 | 2·15 | 0·68–5·03 | 0·404 |

| 9 | 195 | 51·6 | 1·92 | 0·61–4·28 | |

| Skin colour | |||||

| Black | 43 | 11·4 | 1·58 | 0·20–3·65 | 0·116 |

| Non-black | 335 | 88·6 | 2·09 | 0·67–4·94 | |

| Residence area | |||||

| Urban | 372 | 98·4 | 2·00 | 0·67–4·66 | 0·810 |

| Rural | 6 | 1·6 | 1·12 | 0·31–12·86 | |

| School type | |||||

| Public | 268 | 70·9 | 1·95 | 0·62–4·84 | 0·895 |

| Private | 110 | 29·1 | 2·21 | 0·69–3·97 | |

| Income per capita (R$) | |||||

| ≥500·00 (≥$US 159·10) | 173 | 45·8 | 2·28 | 0·74–5·22 | 0·237 |

| <500·00 (<$US 159·10) | 205 | 54·2 | 1·74 | 0·53–4·50 | |

| Maternal age (years) | |||||

| <35 | 127 | 43·8 | 1·67 | 0·52–3·81 | 0·104 |

| ≥35 | 163 | 56·2 | 2·16 | 0·73–5·32 | |

| Maternal education (years) | |||||

| <8 | 96 | 25·5 | 1·67 | 0·49–4·45 | 0·211 |

| ≥8 | 280 | 74·5 | 2·16 | 0·77–4·95 | |

| Sedentary behaviour | |||||

| Yes | 180 | 47·6 | 2·20 | 0·73–5·25 | 0·156 |

| No | 198 | 52·4 | 1·82 | 0·55–4·38 | |

| Solar exposure (min/d) | |||||

| ≥20 | 354 | 93·7 | 1·94 | 0·62–4·82 | 0·435 |

| <20 | 24 | 6·3 | 3·35 | 1·41–3·97 | |

| Number of meals/d | |||||

| ≥5 | 158 | 41·8 | 2·56 | 1·10–5·37 | 0·002* |

| <5 | 220 | 58·2 | 1·55 | 0·28–3·61 | |

| Dairy consumption (g/d)† | |||||

| <169·22 | 198 | 52·4 | 0·71 | 0·20–1·52 | <0·001* |

| ≥169·22 | 180 | 47·5 | 4·34 | 2·47–7·49 | |

| Egg consumption (g/d)† | |||||

| <16·67 | 245 | 64·8 | 1·91 | 0·68–4·50 | 0·685 |

| ≥16·67 | 133 | 35·2 | 2·28 | 0·53–5·34 | |

| Fish consumption (g/d)† | |||||

| <6·67 | 370 | 98·4 | 1·95 | 0·65–4·56 | 0·036* |

| ≥6·67 | 6 | 1·6 | 7·84 | 2·73–19·74 | |

IQR, interquartile range.

P<0·05 (Mann–Whitney test).

Classification according to the median of average three-day consumption.

Vitamin D intake showed a direct correlation with serum 25(OH)D concentration (r=0·205; P<0·001) and HDL-C (r=0·135; P=0·047) but was not correlated with other lipid factors (data not shown).

In relation to the lipid profile, most children showed dyslipidaemia (72·8 %), while 12·8 and 43·4 % of the children had deficiency and insufficiency of vitamin D, respectively. Children with inadequate consumption of vitamin D had lower concentrations of HDL-C (P=0·018) and 25(OH)D (P=0·020; Table 2). This finding persisted after adjustment of the regression model, in which insufficient vitamin D intake increased the prevalence of low HDL-C (PR=2·51; 95 % CI 1·02, 6·18; P<0·05) and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency (PR=1·61; 95 % CI 1·01, 2·58; P<0·05; Table 3).

Table 2.

Alterations in lipid profile and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration according to vitamin D intake in urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

| Vitamin D intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | <10 μg/d | ≥10 μg/d | |||||

| Marker | n | % | n | % | n | % | P value |

| TC (mg/dl) | |||||||

| ≥170 | 87 | 23·1 | 78 | 89·2 | 9 | 10·8 | 0·282 |

| <170 | 290 | 76·9 | 267 | 91·9 | 23 | 8·1 | |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | |||||||

| ≤45 | 112 | 29·8 | 103 | 96·3 | 4 | 3·7 | 0·018* |

| >45 | 264 | 70·2 | 220 | 89·1 | 27 | 10·9 | |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | |||||||

| ≥110 | 52 | 13·8 | 44 | 85·4 | 8 | 14·6 | 0·093 |

| <110 | 324 | 86·2 | 300 | 92·5 | 24 | 7·5 | |

| TAG (mg/dl) | |||||||

| ≥75 | 178 | 47·2 | 158 | 89·0 | 20 | 11·0 | 0·134 |

| <75 | 199 | 52·8 | 186 | 93·4 | 13 | 6·6 | |

| ApoB (mg/dl)† | |||||||

| ≥107 | 30 | 11·6 | 27 | 90·0 | 3 | 10·0 | 0·452 |

| <107 | 228 | 88·4 | 210 | 92·1 | 18 | 7·9 | |

| ApoA1 (mg/dl)† | |||||||

| <161 | 318 | 89·8 | 293 | 92·1 | 25 | 7·9 | 0·079 |

| ≥161 | 36 | 10·2 | 30 | 83·3 | 6 | 16·7 | |

| ApoB:apoA1† | |||||||

| ≥1 | 28 | 10·9 | 27 | 96·4 | 1 | 3·6 | 0·304 |

| <1 | 229 | 89·1 | 209 | 91·3 | 20 | 8·7 | |

| 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | |||||||

| ≥30 | 165 | 43·9 | 138 | 87·3 | 20 | 12·7 | 0·020* |

| <30 | 211 | 56·1 | 185 | 94·4 | 11 | 5·6 | |

TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol.

P<0·05 (Fisher’s exact test).

Classification according to the 90th percentile of the sample.

Table 3.

Association of vitamin D intake with lipid profile markers and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration in urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

| Vitamin D intake | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 μg/d | ≥10 μg/d | |||

| Marker | PR | 95% CI | P value | (Ref.) |

| TC (≥170 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 0·79 | 0·44, 1·41 | 0·423 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 0·72 | 0·36, 1·41 | 0·341 | 1·00 |

| HDL-C (≤45 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 2·47 | 0·98, 6·26 | 0·056 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 2·51 | 1·02, 6·18 | 0·040* | 1·00 |

| LDL-C (≥110 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 0·54 | 0·27, 1·10 | 0·091 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 0·52 | 0·25, 1·07 | 0·083 | 1·00 |

| TAG (≥75 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 0·77 | 0·57, 1·04 | 0·092 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 0·81 | 0·57, 1·15 | 0·246 | 1·00 |

| ApoB (≥107 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 0·80 | 0·26, 2·42 | 0·689 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 0·55 | 0·19, 1·68 | 0·301 | 1·00 |

| ApoA1 (<161 mg/dl) | ||||

| Crude | 1·12 | 0·94, 1·34 | 0·191 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 1·12 | 0·95, 1·33 | 0·167 | 1·00 |

| ApoB:apoA1 (≥1·00) | ||||

| Crude | 2·40 | 0·34, 16·87 | 0·378 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted† | 2·42 | 0·36, 16·15 | 0·362 | 1·00 |

| 25(OH)D (<30 ng/ml) | ||||

| Crude | 1·61 | 0·99, 2·62 | 0·053 | 1·00 |

| Adjusted‡ | 1·61 | 1·01, 2·58 | 0·049* | 1·00 |

PR, prevalence ratio; Ref., reference category; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; PTH, parathyroid hormone; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance.

Goodness-of-fit test (used to evaluate the adjustment of the final model), P>0·05.

P<0·05.

Adjusted for age, sex, income per capita, BMI, maternal and paternal dyslipidaemia, sedentary behaviour and number of daily meals.

Adjusted for age, sex, income per capita, skin colour, solar exposure, season, PTH, body fat percentage, HOMA-IR and maternal education.

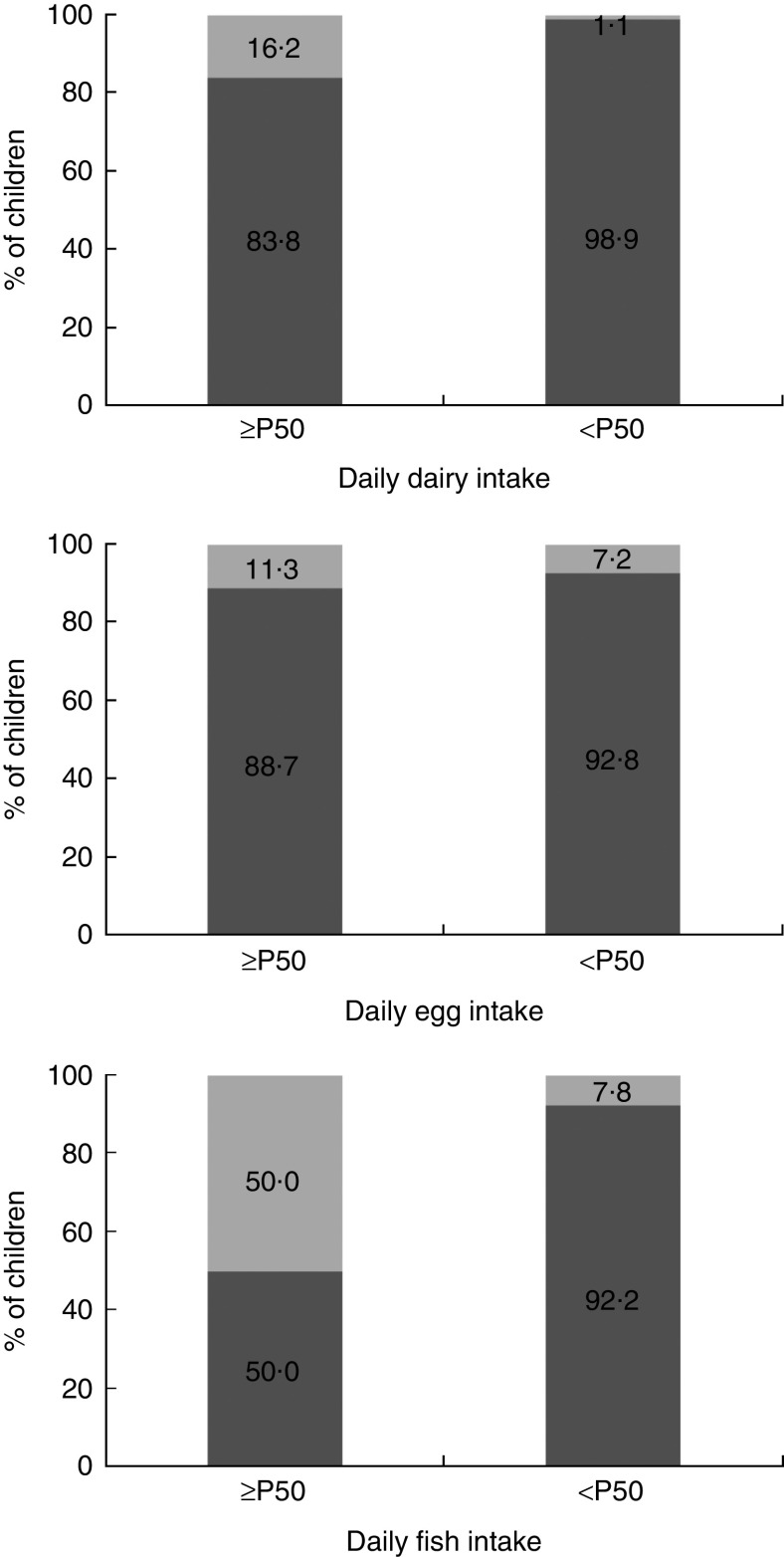

Greater consumption of dairy products and fish contributed to adequacy of vitamin D intake (Table 4; Fig. 1). Between the sexes, the only difference was that boys had higher average consumption of dairy products (boys, 201·29 g; girls, 168·25 g; P<0·05; data not shown).

Table 4.

Main food group sources of vitamin D consumed by urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015

| Food group | R 2 | Accumulated R 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy products | 0·59 | 0·59 |

| Fish | 0·06 | 0·65 |

| Eggs | 0·03 | 0·68 |

Fig. 1.

Vitamin D intake ( , <10 µg/d;

, <10 µg/d;  , ≥10 µg/d) according to the consumption of dairy products, eggs and fish (equal to or greater than the median, ≥P50; less than the median, <P50) by urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015. Dairy intake: P50=169·2 g/d (P<0·001*); egg intake: P50=16·7 g/d (P=0·184); fish intake: P50=6·7 g/d (P=0·009). *P<0·05 (Fisher’s exact test)

, ≥10 µg/d) according to the consumption of dairy products, eggs and fish (equal to or greater than the median, ≥P50; less than the median, <P50) by urban schoolchildren aged 8–9 years (n 378), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015. Dairy intake: P50=169·2 g/d (P<0·001*); egg intake: P50=16·7 g/d (P=0·184); fish intake: P50=6·7 g/d (P=0·009). *P<0·05 (Fisher’s exact test)

Discussion

Vitamin D intake by most children was lower than that recommended by the Institute of Medicine, with dairy products and fish accounting for most of its intake. The inadequate vitamin D intake was associated with higher prevalence of low HDL-C and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency. More than half of the children had dyslipidaemia and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency.

Research in Europe has shown an inverse association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and adverse lipid profile during childhood and adolescence( 38 , 39 ). Considering this association, it is important to know the effect of vitamin D intake on serum lipids, especially in children who have shown high levels of dyslipidaemia. So far, the present study has been one of few to evaluate the association between vitamin D intake and lipid profile in children. A study with Portuguese adolescents showed that low vitamin D intake was associated with a worse metabolic profile, including low HDL-C( 23 ). In New Zealand, children fed milk fortified with vitamin D had serum concentrations of HDL-C improved( 40 ). However, a clinical trial carried out with children in Iran found no effects of vitamin D supplementation on serum concentrations of HDL-C and other lipid profile markers( 41 ). The results of the present study point out the necessity for experimental and interventional research to further investigate the effect of vitamin D intake on HDL-C concentration and other serum lipids.

One mechanism that could explain this relationship would be the participation of vitamin D in the regulation of reverse cholesterol transport through macrophages( 42 ). Reverse cholesterol transport carries cholesterol out of lipid-laden macrophage sponge cells in atherosclerotic plaque, as HDL-C, for clearance from the circulation( 43 ).

We found an association between vitamin D intake and serum 25(OH)D concentration in children. A longitudinal study in Iceland with children aged 1 to 6 years found similar results, showing that vitamin D intake was a predictor of serum 25(OH)D concentration( 44 ). Another study in Sweden reported that adequate vitamin D intake had greater influence on serum 25(OH)D concentration than regional latitude( 45 ). Although sun exposure is responsible for most of the serum concentration of 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3), vitamin D intake is also important, especially in the winter season, when there is a lower incidence of UVB rays( 1 ).

Other research in paediatric populations from different places corroborates our results, showing high prevalence of inadequate vitamin D intake( 46 , 47 ). In this way, one can see the difficulty in reaching the daily recommendation for vitamin D, highlighting the necessity of better food and nutritional education as well as programmes that stimulate access to these foods.

In the present study population, the main sources of vitamin D were dairy products and fish. In Brazil, few foods are enriched with vitamin D, unlike other countries, where policies exist that stimulate food fortification with this nutrient( 48 , 49 ). Moreover, it is observed that there is a worldwide tendency of decreased consumption of milk products, replacing them by sugar-sweetened beverages( 50 ). In relation to fish, it is known that regular consumption is low, especially in Minas Gerais( 51 ). However, each region or country has its own main food sources of vitamin D. One study including a number of European countries identified fish as the main source for adolescents( 52 ). Another study with Spanish schoolchildren found that eggs were the main source( 53 ), unlike the present study, where eggs were not as important.

Differences in vitamin D intake between the sexes may be explained by the fact that boys consume more dairy products, as also shown by the National Research on School Health (PeNSE), where a larger proportion of boys (58·3 %) than girls (49·7 %) consumed milk( 54 ). The results of the present study are in line with other studies across the world showing that boys consume more vitamin D( 55 , 56 ).

It is important to stimulate outdoor activities, as well as the consumption of food sources of vitamin D, because of the high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in the children of our population. In another study with adolescents in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil, deficiency and insufficiency of vitamin D was also found (1·25 and 70·6 %, respectively)( 57 ). In the current study, the majority of children had sun exposure over 20 min/d (93·7 %) and it was conducted in a region with high incident UVB. Other studies with children in countries in low latitudes such as India or Lebanon have shown similar results( 58 , 59 ).

Our results point out the necessity of planning and implementing public health policies that stimulate outdoor activities in schools and elsewhere. Other strategies may be adopted, such as food and nutritional education activities, stimulating the consumption of source foods, as well as facilitating access of families to these foods. Generalized supplementation of the population is not recommended by the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabology( 60 ). However, a policy of food fortification should be encouraged in foods that are part of Brazilian children’s eating habits, such as cereals and dairy products, as a proven strategy for reducing the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency.

We highlight that the present study is one of the few in the world to have evaluated the relationship between consumption of vitamin D and dyslipidaemia, as well as vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in childhood. However, the study is limited by use of a cross-sectional design, not allowing us to establish causality. Moreover, there is still no consensus on the cut-off points for normal apoB and apoA1 for the paediatric population to infer its prevalence. Another point is that the nutritional fact labels of most foods include no information about their vitamin D content. Even though the 24 h dietary recall has its own limitations because it depends on the memory of the interviewee and does not predict habitual intake, adjustments were made( 35 , 37 ). Energy intake was adjusted for intra-individual variability to minimize possible biases, and photo albums were provided showing household utensils and examples of portion sizes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study has found that Brazilian children have a high prevalence of inadequate vitamin D intake, dyslipidaemia and 25(OH)D insufficiency/deficiency. Inadequate intake was associated with low HDL-C and vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency. Dairy products and fish were the groups that provided the largest contribution to vitamin D intake. The importance of better food and nutritional education and programmes stimulating and facilitating access to source foods is also highlighted. Moreover, experimental research and interventional studies are needed to better understand the effect of vitamin D intake on serum concentrations of HDL-C and other lipids in childhood.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for financial support; BIOCLIN® for providing material for biochemical analysis; the Research Support Foundation of State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for the granting of a doctor’s scholarship to M.S.F. and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for the scholarships granted to L.G.S., M.A.S. and N.P.R. They also thank all the children who participated in this work and their guardians. Financial support: This work was supported by the CNPq (grant number 478910/2013-4). The CNPq had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. Authorship: M.S.F. assisted the conception and design of this work, assisted data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, conducted the literature search, as well as wrote the manuscript. L.G.S. and M.A.S. revised and approved the final version to be published. N.P.R. assisted data collection, revised and approved the final version to be published. J.F.N. designed the study including the data collection, coordinated and supervised and approved the final version to be published. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all the procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Federal University of Viçosa (case number 663.171/2014). Moreover, this project was presented to the Municipal Department of Education, the Regional Superintendent of Education and principals of schools. All participants, as well as their responsible parents/guardians, were informed about the objectives of the research and informed consent was obtained from all children’s parents.

References

- 1. Holick MF (2007) Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 357, 266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schmid A & Walther B (2013) Natural vitamin D content in animal products. Adv Nutr 4, 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holick MF & Chen TC (2008) Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr 87, issue 4, 1080S–1086S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cashman KD (2007) Vitamin D in childhood and adolescence. Postgrad Med J 83, 230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aryan Z, Rezaei N & Camargo CA Jr (2017) Vitamin D status, aeroallergen sensitization, and allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Rev Immunol 36, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franchi B, Piazza M, Sandri M et al. (2014) Vitamin D at the onset of type 1 diabetes in Italian children. Eur J Pediatr 173, 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Petersen RA, Dalskov SM, Sørensen LB et al. (2015) Vitamin D status is associated with cardiometabolic markers in 8–11-year-old children, independently of body fat and physical activity. Br J Nutr 114, 1647–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunha KA, Magalhães EIS, Loureiro LMR et al. (2015) Calcium intake, serum vitamin D and obesity in children: is there an association? Rev Paul Pediatr 33, 222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute of Medicine (2011) Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palacios C & Gonzalez L (2014) Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 144, 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Santos BR, Mascarenhas LP, Satler F et al. (2012) Vitamin D deficiency in girls from South Brazil: a cross-sectional study on prevalence and association with vitamin D receptor gene variants. BMC Pediatrics 12, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lourenço BH, Qi L, Willett WC et al. (2014) FTO genotype, vitamin D status, and weight gain during childhood. Diabetes 63, 808–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Voortman T, van den Hooven EH, Heijboer AC et al. (2015) Vitamin D deficiency in school-age children is associated with sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. J Nutr 145, 791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bezrati I, Fradj MKB, Ouerghi N et al. (2016) Vitamin D inadequacy is widespread in Tunisian active boys is related to diet but not to adiposity or insulin resistance. Libyan J Med 11, 31258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soininen S, Eloranta AM, Lindi V et al. (2016) Determinants of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration in Finnish children: the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) study. Br J Nutr 115, 1080–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munasinghe LL, Willows N, Yuan Y et al. (2015) Dietary reference intakes for vitamin D based on the revised 2010 dietary guidelines are not being met by children in Alberta, Canada. Nutr Res 35, 956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Julián C, González-Gross M, Breidenassel C et al. (2017) 25-Hydroxyvitamin D is differentially associated with calcium intakes of Northern, Central, and Southern European adolescents: results from the HELENA study. Nutrition 36, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta N, Shah P, Nayyar S et al. (2013) Childhood obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Indian J Pediatr 80, Suppl. 1, S28–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franca E & Alves JG (2006) Dyslipidemia among adolescents and children from Pernambuco. Arq Bras Cardiol 87, 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carvalho DF, Paiva AA, Melo AS et al. (2007) Blood lipid levels and nutritional status of adolescents. Rev Bras Epidemiol 10, 491–498. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rusconi RE, De Cosmi V, Gianluca G et al. (2015) Vitamin D insufficiency in obese children and relation with lipid profile. Int J Food Sci Nutr 66, 132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Daghri NM, Sabico S, Al-Saleh Y et al. (2016) Calculated adiposity and lipid indices in healthy Arab children as influenced by vitamin D status. J Clin Lipidol 10, 775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moreira C, Moreira P, Abreu S et al. (2014) Vitamin D intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 12, 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2017) Cidades@ – Minas Gerais: Viçosa. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; available at http://cod.ibge.gov.br/690 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barker DJ, Osmond TJ, Forsen E et al. (2005) Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med 353, 1802–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2011) Indicadores Sociais. Uma análise dos resultados do universo do Censo Demográfico 2010. Estudos & Pesquisas: informações demográfica e socioeconômica. http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/default.shtm (accessed November 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andaki ACR (2010) Prediction of metabolic syndrome in children through of anthropometric measurements and physical activity level. Masters Dissertation, Federal University of Viçosa; available at http://www.locus.ufv.br/handle/123456789/2720

- 28. American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Communications and Media (2013) Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132, 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization (1995) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report Series no. 854. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed]

- 30. Faludi AA, Izar MCO, Saraiva JFK et al. (2017) Update of the Brazilian directives on dyslipidemias and atherosclerosis prevention. Arq Bras Cardiol 109, 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA et al. (2011) Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 1911–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS et al. (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zabotto CB, Veanna RPT & Gil MF (1996) Registro Fotográfico Para Inquéritos Dietéticos: Utensílios e Porções. Goiânia: Nepa-Unicamp. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Philippi ST (2002) Tabela de Composição de Alimentos: Suporte para Decisão Nutricional, 2ª ed. Brasília: Coronário. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Willett W (2013) Nutritional Epidemiology , 3th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ministério da Saúde (2006) Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira: Promovendo a Alimentação Saudável. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Willett WC & Stampfer MJ (1986) Total energy intake: implications for epidemiological analyses. Am J Epidemiol 124, 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Ortega RM, González-Rodríguez LG et al. (2011) Vitamin D deficiency is an independent predictor of elevated triglycerides in Spanish school children. Eur J Nutr 50, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pacifico L, Anania C, Osborn JF et al. (2011) Low 25(OH)D3 levels are associated with total adiposity, metabolic syndrome, and hypertension in Caucasian children and adolescents. Eur J Endocrinol 165, 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Graham D, Kira G, Conaglen J et al. (2009) Vitamin D status of year 3 children and supplementation through schools with fortified milk. Public Health Nutr 12, 2329–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelishadi R, Salek S, Sakek M et al. (2014) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in children with metabolic syndrome: a triple-masked controlled trial. J Pediatr (Rio J) 90, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matsuura F, Wang N, Chen W et al. (2006) HDL from CETP-deficient subjects shows enhanced ability to promote cholesterol efflux from macrophages in an apoE- and ABCG1-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest 116, 1435–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rye KA, Bursill CA, Lambert G et al. (2009) The metabolism and anti-atherogenic properties of HDL. J Lipid Res 50, Suppl, S195–S200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thorisdottir B, Gunnarsdottir I, Steingrimsdottir L et al. (2016) Vitamin D intake and status in 6-year-old Icelandic children followed up from infancy. Nutrients 8, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Åkeson PK, Lind T, Hernell O et al. (2016) Serum vitamin D depends Less on latitude than on skin color and dietary intake during early winter in Northern Europe. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 62, 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Raimundo FV, Bueno AL, Moulin CC et al. (2010) Variação sazonal de níveis de 25-hidroxivitamina D sérica e ingestão dietética de vitamina D em crianças e adolescentes com baixa estatura. Rev HCPA & Fac Med Univ Fed Rio Gd do Sul 30, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ortega Anta RM, González-Rodríguez LG, Jiménez Ortega AI et al. (2012) Ingesta insuficiente de vitamina D en población infantil española; condicionantes del problema y bases para su mejora. Nutr Hosp 27, 1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Calvo MS & Whiting SJ (2013) Survey of current vitamin D food fortification practices in the United States and Canada. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 136, 211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Black LJ, Walton J, Flynn A et al. (2015) Small increments in vitamin D intake by Irish adults over a decade show that strategic initiatives to fortify the food supply are needed. J Nutr 145, 969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dror DK & Allen LH (2014) Dairy product intake in children and adolescents in developed countries: trends, nutritional contribution, and a review of association with health outcomes. Nutr Rev 72, 68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jaime PC, Stopa SR, Oliveira TP et al. (2015) Prevalence and sociodemographic distribution of healthy eating markers, National Health Survey, Brazil 2013. Epidemiol Serv Saude 24, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Julián C, Mouratidou T, Vicente-Rodriguez G et al. (2017) Dietary sources and sociodemographic and lifestyle factors affecting vitamin D and calcium intakes in European adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) Study. Public Health Nutr 20, 1593–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aparicio Vizuete A, López-Sobaler AM, López Plaza B et al. (2013) Ingesta de vitamina D en una muestra representativa de la población española de 7 a 16 años. Diferencias en el aporte y las fuentes alimentarias de la vitamina en función de la edad. Nutr Hosp 28, 1657–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2009) Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar 2009. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Boucher-Berry C, Speiser PW, Carey DE et al. (2012) Vitamin D, osteocalcin and risk for adiposity as co-morbidities in middle school children. J Bone Miner Res 27, 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salamoun MM, Kizirian AS, Tannous RI et al. (2005) Low calcium and vitamin D intake in healthy children and adolescents and their correlates. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Oliveira RM, Novaes JF, Azeredo LM et al. (2014) Association of vitamin D insufficiency with adiposity and metabolic disorders in Brazilian adolescents. Public Health Nutr 17, 787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Reddy D et al. (2005) Vitamin D and bone mineral density status of healthy schoolchildren in northern India. Am J Clin Nutr 82, 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Nabulsi M, Choucair M et al. (2001) Hypovitaminosis D in healthy schoolchildren. Pediatrics 107, E53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Maeda SS, Borba VZC, Camargo MBR et al. (2014) Recommendations of the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabology (SBEM) for the diagnosis and treatment of hypovitaminosis D. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab 58, 411–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]