Abstract

Dementia is a chronic, progressive disease that is now much more widely recognised and treated. Patients with dementia may require palliative care when they reach the end stage of their illness, or they may have mild–moderate cognitive symptoms comorbid with a life-limiting illness. The variety of presentations necessitates a highly individual approach to care planning, and patients should be encouraged to set their own goals and contribute to advanced care planning where possible. Assessment and management of distressing symptoms at the end of life can be greatly helped by a detailed knowledge of the individuals’ prior wishes, interdisciplinary communication and recognition of changes in presentation that may result from new symptoms, for example, onset of pain, nutritional deficits and infection. To navigate complexity at the end of life, open communication that involves patients and families in decisions, and is responsive to their needs is vital and can vastly improve subjective experiences. Complex ethical dilemmas may pervade both the illness of dementia and provision of palliative care; we consider how ethical issues (eg, providing care under restraint) influence complex decisions relating to resuscitation, artificial nutrition and treatment refusal in order to optimise quality of life.

Keywords: mental health

Introduction

Provision of high-quality dementia care and palliative care may present a number of practical and ethical challenges. Provision of palliative care to people with dementia can be particularly complex and will require close attention to individual goals and an interdisciplinary approach using the skills of the multidisciplinary team. In preparing this paper, we have in mind that rising dementia prevalence globally1 means that patients with dementia will more commonly present to palliative care physicians, where dementia is a comorbidity to other life-limiting conditions, and that an increasing number of individuals with severe dementia may require palliative care specifically in relation to their cognitive disorder.

The provision of palliative care for patients with dementia is enshrined within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Dementia guidelines.2 These guidelines suggest incorporating a palliative care approach that considers physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs to maximise the quality of life for individual patients, for example, through management of pain, nutrition and advance care planning. For patients at the stage in their illness where palliative care may be appropriate, there are likely to be many benefits to patients and their families of a palliative approach that is holistic, person centred and focuses on quality of life. The approach taken to communication and management of complex issues will vary significantly depending on individual circumstances and dementia severity. In this paper, we summarise an approach to diagnosis of dementia, assessment and management of common symptoms at the end of life, approaches to communication and a discussion of ethical issues.

Methods

The search strategy used PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar and the Cochrane Database, using the terms ‘dementia’, ‘palliative care’ and ‘end of life’ from 2000 to January 2018. These databases aimed to access a wide variety of literature pertinent to this clinical issue, using a wide timescale to ensure inclusivity. This search was completed on 20 January 2018. Studies were included in this review due to their quality and their clinical relevance.

Diagnosing dementia

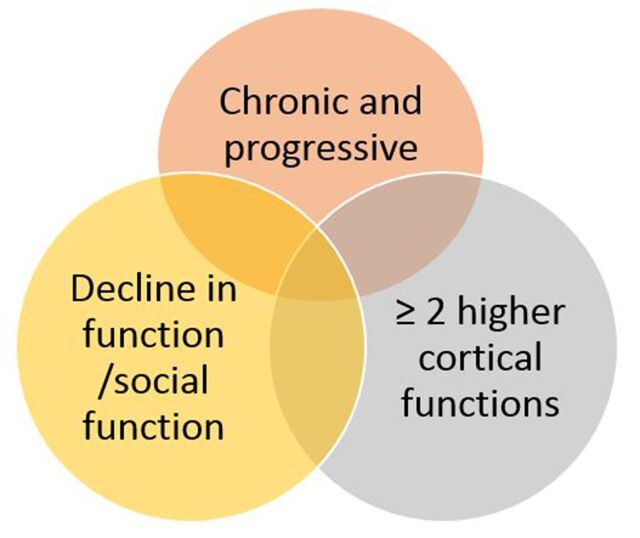

Dementia is a broad term encompassing a range of conditions, each with particular presenting features. At its core, it is a chronic and progressive condition with a duration of at least 6 months, affecting two or more higher cortical functions, and with an adverse effect on occupational or social function (see figure 1). The symptoms should not be due to psychiatric disease or delirium, and patients should be alert and conscious.3 Common cognitive changes are amnesia, aphasia, apraxia, disorientation and altered executive function. These may be accompanied by a range of non-cognitive symptoms, including apathy, personality change, low mood, anxiety and irritability.

Figure 1.

Diagnosing dementia.

Rates of dementia diagnosis are rising4; however, patients may still present without a formal dementia diagnosis. Where this is suspected, a cognitive history from the patient and collateral history from an informant will signpost towards a diagnosis. Blood should be taken to screen for reversible causes of cognitive impairment (full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, thyroid unction tests, B12, folate, glucose and calcium), as recommended by NICE.2 Referral for a more detailed neurocognitive assessment at a memory clinic may be appropriate.

Predicting poor outcome

Cognitive assessment of dementia can provide a useful overview of dementia severity; however, prognosis varies on the stage of cognitive disorder and also on comorbidities, particularly those relating to cardiovascular disease. Despite the current availability of literature giving estimates of life expectancy,5 predicting death is notoriously difficult even in the later stages of the illness and prognosis varies considerably among individuals. There are several factors that may be interpreted as indicating a higher likelihood of death within a matter of months, such as aspiration pneumonia, but even existing prognostic tools are only modest in their ability to inform the estimate.6 7 Thus, there are real challenges in conveying both the poor prognosis itself and the level of uncertainty in predicting terminal events.

In those with severe dementia, where a comorbid life-limiting illness is suspected (eg, cancer), there can be a reluctance to investigate patients. While it is important to be mindful of their overall quality of life and the need to limit unnecessary investigations, even in those with severe dementia, accurate diagnosis of underlying conditions can be crucial to help guide treatment, aid prognosis and assess the need for palliative care.

Goals of care

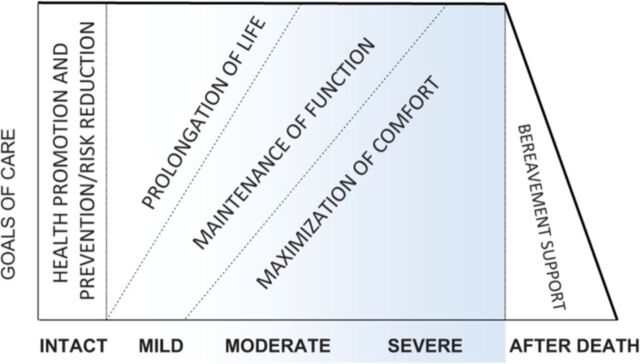

Individual priorities and goals of care will vary significantly depending on the stage of dementia (see figure 2), and discussions need to be tailored to the stage of illness. It is important, however, that complex decisions are discussed at a relatively early stage, when a person with dementia may be actively involved in care planning. Advance care planning allows patients and their families the opportunity to discuss future wishes and goals of care, for example, resuscitation, nutrition, location of end-of-life care and limits on treatment.8 These issues are equally pertinent for individuals with dementia, as they are for those with other terminal illnesses. Making reference to any pre-existing legal statements and consulting a Lasting Power of Attorney (if available) is important. There are resources to aid advance planning, which include emergency healthcare plans, advance statements and advance decisions to refuse treatment.9 While the format of the plans themselves may vary, the hallmark of an effective plan is one which is clearly documented, readily accessible and which can adapt to change in response to the person’s care needs.

Figure 2.

Dementia progression: changing care goals and priorities.11

A frank discussion about the nature, challenges and progression of the disease early on will enable patients to receive medical care consistent with their values, goals and preferences.10 In the later stage of dementia, the emphasis of the care plan is generally the promotion of comfort and symptom control as the primary goal.11 The CASCADE study followed 323 nursing home residents with advanced dementia for 22 months to assess progression and outcomes. It found that residents whose families and carers had an understanding of the clinical course and poor prognosis were less likely to undergo burdensome interventions in the final days of life.12 Another study focusing on goals of care, palliative treatment plans and intervention in dementia leads to half as many hospital transfers for nursing home residents with advanced dementia.13

Assessment and management of symptoms

Pain

Assessment

Pain can be a significant, under-reported and undertreated problem in patients with dementia.14 Pain behaviours can be complex and individualised and can be associated with depression, functional impairment and agitated behaviour.15 Clinically, recognising distress is an important first step.16 There are a number of pain assessment tools available, for example, PAINAD (Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale).17 It considers breathing, negative vocalisation, facial expressions, body language and the ability to be consoled. Important factors identified in a recent study highlighted three key elements to identifying an overall picture of pain: time to get to know the individual and their carers to identify cues, interdisciplinary communication and availability and range of pain management resources.18

Management

Ageing is related to a high incidence of painful conditions, including musculoskeletal (such as arthritis) and neuropathic pain (as a result of diabetes or stroke).19 It is therefore important to consider a patient’s medical history. Non-pharmacological pain management strategies such as patient repositioning can be valuable.18 When considering pharmacological management, it is important to consider potential side effects, including worsening confusion.18 Considering the possible cause of the pain and working using the principles of the WHO analgesic ladder20 are good initial steps, for example, commencing regular paracetamol. When a patient might not be able to request analgesia, making sure it is ‘by the clock’ is important.20 Choosing an analgesic depends partly on ease of administration; oral routes where possible are easiest. Transdermal medication can be helpful if an oral route is challenging. In exceptional cases, covert medication may need to be considered, following an assessment of capacity and a best-interests decision.21

Behavioural issues

Assessment

Agitation and aggression are common problems in dementia.22 These behaviours may be an active attempt by the person to express an unmet need.23 Therefore, having a clear idea of what is happening and what the person is normally like is essential, as terms like ‘aggression’ and ‘wandering’ are non-specific.22 Using an assessment tool such as the DisDAT assessment may be helpful to put the distress into context, for example, anxiety can be more common in patients who have suffered from it at other times in life.16 23 An alternative is the use of ‘ABC’ charts, so that the Antecedents, Behaviour and Consequences can be clearly documented, and any behavioural patterns noted to guide further management.

Management

If there is an identifiable unmet need, then treating it can reduce agitation.17 These can be physical things like pain, constipation, fatigue or maybe side effects from the introduction of a new medication.23 Non-pharmacological approaches should be considered first line and can include environmental modification, sensory stimulation and attempts to improve communication.23 Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication may have a role in reducing agitation, but it is unclear whether this is of benefit in palliative care settings.24 Antipsychotics are the most commonly prescribed drug for challenging behaviour,23 but should be prescribed bearing in mind their significant side-effect profile, including falls, increased risk of cerebrovascular events, drowsiness and extrapyramidal symptoms.25 Despite these side effects, medications such as risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine may be beneficial (off-license) in severe agitation or psychosis, or where behaviour is putting the patient or others at risk.23 Antipsychotics should be avoided in Lewy body dementia due to a higher risk of adverse events. Benzodiazepines may be considered in the last days of life. In one study, it was in the final 2 days before death that sedating medications like midazolam were more widely used.26

Nutrition

Assessment

Weight loss is common in dementia primarily due to reduced calorie intake.12 Struggling to eat adequate calories in advanced dementia can be due to many reasons including appetite loss, poor oral health, forgetting to eat, agnosia (not recognising food), apraxia, communication problems, swallowing problems, anxiety, distraction, distress and when there is comorbid infection.27 Loss of a safe swallow can lead to aspiration, which occurs in around 30% of this cohort of patients.27 It may be appropriate for a dietician to assess nutrition and/or a speech and language therapist to assess swallowing.

Management

There are simple strategies that can be helpful including supplementation of food, presentation of food (pre-cut, softer or smaller portions), allowing additional time for meals, and encouragement and support when eating.27 28 Keeping a patient with advanced dementia ‘nil by mouth’ for a period of time can mean that they never regain their swallow as they may lose the autonomic memory of oral feeding.27 If they are still keen to or able to eat, then it may be that a best-interests decision process is required if they are at risk of aspiration.

Families, care staff and medical teams may question whether to provide nutrition and hydration either in the form of nasogastric (NG) feeding, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding or parenterally. In the USA, artificial nutrition is more commonly used; in the CASCADE trial, 8% of the patients studied were tube fed with 7.3% undergoing tube feeding in the last 3 months of life.12 Murphy and Lipman compared a group who had a PEG tube inserted and were fed with a similar size group who did not receive artificial nutrition.29 It showed no survival benefit with artificial nutrition. The evidence suggests that NG or PEG placement does not improve overall functional status, prevent aspiration or extend life and can be associated with a greater mortality.30 NG tubes can be uncomfortable and inserting PEG tubes comes with risks of complications.27 It is helpful if a patient and the family have advance plans around nutrition and also have had the opportunity to have conversations about the benefits and burdens of different interventions.

There are occasional situations where tube feeding may have additional benefits, for example, administration of medications for patients with Parkinson’s disease who are unable to swallow.27 Subcutaneous or intravenous fluids are occasionally used during an acute illness for short-term support27; however, caution is needed due to the risk of fluid overload,28 and they are not generally appropriate at the very end of life.11

Infections

Assessment

Infections, particularly pneumonia and urinary infections, are common in advanced dementia and can often be terminal events.31 Patients frequently present with an unexplained change in behaviour such as agitation or increased confusion.32 Therefore, any change in behaviour should be a trigger to check for signs of infection. Antibiotic use is extensive—a study looking at antimicrobial use found that 66% of patients with advanced dementia received at least one course of antibiotics over a 322-day period, with administration increasing significantly as patients approached death.33 While there may be acute individual benefits, high levels of antimicrobial use may lead to an increase in individual treatment burden, Clostridium difficile infection34 and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.33 There can be complications associated with administration, drug side effects and the distress of investigations.

Management

The decision whether to treat an infection in a patient with advanced dementia needs to align with the patients’ goals of care. If treatment is necessary, it should be based on a clinical assessment of severity, for example, CURB-65,35 and antimicrobial use, for example, local antimicrobial guidelines. One study investigated treatment of pneumonia in nursing home residents with advanced dementia and found that antimicrobial treatment was associated with prolonged survival but not improved comfort.36 This was also borne out in the CASCADE study that highlighted prolonged survival in these patients, but with increased discomfort.12 If comfort is the goal, then the main focus should be on treating symptoms with palliation.37

Communication with family and carers

Communication with carers and families is an integral part of caring for patients with dementia. One qualitative study reviewing end-of-life care in older people in acute wards highlighted that carers’ experience of the end-of-life care of their relative was enhanced when a mutual understanding was achieved with healthcare professionals. Those who felt unsure about what was happening were much more likely to be distressed by their relative’s end-of-life care.38 When considering what can be done to improve communication, four key areas have been highlighted, which can lead to satisfactory involvement: feeling that information is shared, feeling included in decision-making, feeling that there is someone you can contact when you need to and feeling that the service is responsive to your needs.39 Guidance and support is needed by families as they transition from a curative mindset to a more comfort-led approach.40 Open communication and a trusting relationship is integral to this process.27

Ethical issues

Care of a patient with dementia towards the end of their life may necessitate complex discussions about their treatment and care. A culture of openness in the face of these challenging subjects has been found to lead to better outcomes. The Delphi study defines optimal palliative care in dementia, informed by the available literature and global panel of 89 experts.11 It outlines the importance of person-centred care, communication and shared decision-making that anticipates and plans for potential difficulties. Despite the need for care planning and discussion around pre-terminal events, the rate of hospital admission and trials of various treatments are high in patients with advanced dementia.12 The consensus of the Delphi study on avoiding overly aggressive, burdensome or futile treatment advises prudence when considering an acute admission and to place it in context of the individual’s goals of care.

When caring for a person with dementia, particularly at the later stages, there may be situations where they may be resistive of various types of care intervention (washing, toileting, dressing, having medications administered and feeding). Staff involved in giving such care may be called on to make decisions regarding whether or not to undertake the intervention in the context of judicious restraint, sometimes termed ‘forced care’.41 Forced care is viewed under the Mental Capacity Act42 as a type of restraint.43 The use of restraint in people who lack capacity is considered acceptable, or at least free from the threat of liability, provided that two conditions are met: that “the person taking action must reasonably believe that restraint is necessary to prevent harm to the person who lacks capacity, and the amount or type of restraint used and the amount of time it lasts must be a proportionate response to the likelihood and seriousness of harm”.42 The guidance also clearly states that carers should consider less restrictive options before using restraint.42 Thus, there exists a tension between the desire to provide basic interventions (washing, changing soiled pads) and the very action of providing this care precipitating distress. The exploration of when to give care and when not to give care links with the need to provide measures of comfort to the dying person. Symptoms may manifest as resistance, aggression or other behavioural disturbance. In order to navigate these situations successfully, there needs to be consideration of what basic care to provide and whether any form of restraint is justified. The perspectives of all care givers must be explored, along with tools to assess behaviours supported by nursing and specialist psychiatric team input.

Location of care

When questioned about ideal location of death, over two-thirds of people would prefer to die in their own homes44; however, there has been a gradual shift to deaths in hospitals or other formal care homes, particularly in those aged over 65.45 According to a 2010 report by the National End of Life Intelligence Network, 58.4% of people aged 75 and over died in hospital, 12.1% died in nursing homes and 10.0% of deaths were in residential homes. Only 15.5% of people aged 75 and over died in their own residence and 3.1% of deaths were in a hospice, a much lower proportion than in all other age groups.46

Care homes

The Alzheimer’s Society estimates the prevalence of dementia in care homes at 69.0% (62.7% for men and 71.2% for women).47 People move into formal care at many different stages in their illness, but once in care the likelihood of death in this setting is high.48 There are many potential difficulties in managing the palliative stage of dementia within this setting, particularly availability of access to both senior primary care and specialist palliative input, lack of co-ordination of professionals involved in palliation, lack of staff confidence and training.49

Hospices

There are particularly low rates of admission to hospice care for patients with diagnoses of dementia. There exists some tension between the need for specialist input regarding the management of symptom control at the end of life, and the emphasis of hospice placements being reserved for those with the most complex and challenging end-of-life needs. While hospice environments may be excellent for many people, they may not always be appropriate for those with severe dementia. For example, hospice environments designed to provide easy access to outside space may not be appropriate for a patient who is prone to disorientation and may leave the building and be unable to find their way back. The majority of symptoms found at the end of life in dementia may not necessarily warrant an admission to a hospice; however, input and particularly guidance in the form of outreach may be invaluable in allowing a person with dementia to die in a more appropriate environment or without a move being required.

Hospital

Many patients’ ideal place of death would not be in hospital, particularly if that death is anticipated. There will be occasions when a move to hospital may be necessary or preferred, for example, in the instance of a fall and likely fractured bone, admission to hospital may be the only way of ensuring adequate symptom control and pain relief. While hospital admission may not be desired, it may provide continuity of care, intensive management of symptoms and relief of carer stress. Comprehensive, advanced care planning, structured on an individual basis, is invaluable in assisting and reducing unwanted admissions, and ensuring this is used only when necessary and appropriate.

Conclusion

The underlying message from much of the literature refers to the need for an individualistic, person-centred approach, which incorporates their personal narrative, and the physical, psychological and spiritual dimensions to their life.50 For patients with dementia, there may be particular communication challenges and additional nuances to consider in relation to advanced care planning and ethical issues in care. It is clear that there is much to be gained for patients and their families by adopting, at the right stage, a palliative focus to treatment. For palliative care specialists, greater knowledge about assessment, diagnosis and management of dementia may inform their holistic approach to individuals. It is important that this specialist knowledge is available in a variety of settings and that clinicians from different backgrounds feel confident in conducting difficult conversations about sensitive issues in relation to resuscitation, tube feeding, treating infections and hospital transfer, and can commence treatment with a palliative focus.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Prince M. World Alzheimer’s report 2015. London: The Global Impact of Dementia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. NICE. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. London: NICE, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. International Classification of Disease: version 10. 2016. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/icdonlineversions/en/ (accessed 18 Jan 2018).

- 4. Donegan K, Fox N, Black N, et al. Trends in diagnosis and treatment for people with dementia in the UK from 2005 to 2015: a longitudinal retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e149–56. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30031-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanetti O, Solerte SB, Cantoni F. Life expectancy in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;49(Suppl 1):237–43. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Steen JT, Mitchell SL, Frijters DH, et al. Prediction of 6-month mortality in nursing home residents with advanced dementia: validity of a risk score. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:464–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hughes J, Lloyd Williams M, Sachs G. Advance care planning and palliative care in dementia: a view from the Netherlands, in ‘Supportive care for the person with dementia’. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Gold Standards Framework. www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk (accessed 18 Jan 2018).

- 9. Deciding right: a North East initiative for making care decisions in advance Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust Kent: Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–32. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197–209. 10.1177/0269216313493685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, et al. Effect of the goals of care intervention for advanced dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:24–31. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown CA. Pain in communication impaired residents with dementia: analysis of Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) data. Dementia 2010;9:375–89. 10.1177/1471301210375337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burns M, McIlfatrick S. Palliative care in dementia: literature review of nurses' knowledge and attitudes towards pain assessment. Int J Palliat Nurs 2015;21:400–7. 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.8.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jordan A, Regnard C, O’Brien JT, et al. Pain and distress in advanced dementia: choosing the right tools for the job. Palliat Med 2012;26:873–8. 10.1177/0269216311412227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S. The utility of pain assessment for analgesic use in persons with dementia. Pain 2008;134:16–23. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lichtner V, Dowding D, Allcock N, et al. The assessment and management of pain in patients with dementia in hospital settings: a multi-case exploratory study from a decision making perspective. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:427. 10.1186/s12913-016-1690-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guerriero F, Sgarlata C. Pain management in dementia: so far, not so good. Geriatr Gerontol 2016;64:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reid C, Davies A. The World Health Organization three-step analgesic ladder comes of age. Palliat Med 2004;18:175–6. 10.1191/0269216304pm897ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. NICE. Managing Medicines in Care Homes. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc/SC1.jsp.

- 22. Krishnamoorthy A, Anderson D. Managing challenging behaviour in older adults with dementia. Prog Neurol Psychiatry 2011;15:20–6. 10.1002/pnp.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stokes G. Challenging behaviour in dementia: a person centred approach. Bicester: Winslow Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ 2015;350:h369. 10.1136/bmj.h369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD003476. 10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hendriks SA, Smalbrugge M, Hertogh CM, et al. Dying with dementia: symptoms, treatment, and quality of life in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:710–20. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harwood RH. Feeding decisions in advanced dementia. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014;44:232–7. 10.4997/JRCPE.2014.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ying I. Artificial nutrition and hydration in advanced dementia. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:245e125–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1351–3. 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cervo FA, Bryan L, Farber S. To PEG or not to PEG: a review of evidence for placing feeding tubes in advanced dementia and the decision-making process. Geriatrics 2006;61:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitchell S. Palliative care of patients with advanced dementia: UpToDate Inc, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Capewell A, Hazell E. UTIs and Dementia Factsheet 528LP. Alzheimer’s Soc. 2015. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/info/20029/daily_living/1174/urinary_tract_infections_utis_and_dementia/3 (accessed 5 Jan 2018).

- 33. D’Agata E, Mitchell SL. Patterns of antimicrobial use among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:357–62. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Archbald-Pannone LR, McMurry TL, Guerrant RL, et al. Delirium and other clinical factors with Clostridium difficile infection that predict mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:690–3. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu JL, Xu F, Zhou H, et al. Expanded CURB-65: a new score system predicts severity of community-acquired pneumonia with superior efficiency. Sci Rep 2016;6:22911. 10.1038/srep22911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Givens JL, Jones RN, Shaffer ML, et al. Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1102–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mitchell SL. Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2533–40. 10.1056/NEJMcp1412652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caswell G, Pollock K, Harwood R, et al. Communication between family carers and health professionals about end-of-life care for older people in the acute hospital setting: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:35. 10.1186/s12904-015-0032-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walker E, Dewar BJ. How do we facilitate carers' involvement in decision making? J Adv Nurs 2001;34:329–37. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van der Steen JT. Dying with dementia: what we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;22:37–55. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sells D, Howarth A. The forced care framework: guidance for staff. Jounral Dement Care 2014;22:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mental Capacity Act. 2005: Code of Practice. London. 2007. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497253/Mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice.pdf.

- 43. UK Public General Acts. The Mental capacity Act 2005. London: UK Public General Acts, 2005. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, et al. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2006–15. 10.1093/annonc/mdr602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Where people die (1974–2030): past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliat Med 2008;22:33–41. 10.1177/0269216307084606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Public Health England. Public Health England’s National End of Life Care Intelligence Network (NEoLCIN). http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/home (accessed 22 Jan 2018).

- 47. Dementia UK. Update (second edition). 2014. http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=2323.

- 48. Cartwright JC. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities as places for dying. Annu Rev Nurs Res 2002;20:231–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dening KH, Greenish W, Jones L, et al. Barriers to providing end-of-life care for people with dementia: a whole-system qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:103–7. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hughes J, Baldwin C. Ethical issues in dementia care, making difficult decisions. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2006. [Google Scholar]