Abstract

There is increasing effort in both the inpatient and outpatient setting to improve care, function, and quality of life for children with congenital heart disease, and to decrease complications. As the mortality rates of surgical procedures for congenital heart disease decrease, improvement in perioperative morbidity and quality of life have become key metrics of quality of care. Quality of life and function in patients with congenital heart disease can be affected by multiple factors: the underlying heart condition, cardiac surgery, complications, and medical treatment. Some of the functional areas affected are motor abilities, exercise capacity, feeding, speech, cognition, and psychosocial adjustment. Rehabilitation interventions aim to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life for those with physical impairments or disabilities. Interventions such as exercise training have been extensively evaluated in adults with acquired heart disease, and rehabilitation interventions for pediatric patients with congenital heart disease have similar potential to improve perioperative morbidity and quality of life. However, literature regarding the pediatric population is limited. We have gathered a multidisciplinary team of experts from major institutions to create evidence- and practice-based guidelines for pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs in both inpatient and outpatient settings. To improve the quality of life of pediatric patients with congenital heart disease, we propose the use of individualized multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs that include: medical management; neuropsychology; nursing care; rehabilitation equipment; physical, occupational, speech, and feeding therapies; and exercise training.

Keywords: children, heart, rehabilitation, function, cardiac

1. Introduction

In pediatric patients with congenital heart disease (CHD), postcardiac surgery morbidity and mortality have decreased over the past decades. In the United States, survival in the first year of life for children with critical CHD (i.e., those for whom surgery or intervention is needed) is 75.2% vs. 97.1% for those with non-critical CHD (1). However, a growing body of research has found that some pediatric patients with CHD experience long-term functional impairment and some degree of disability following surgery, particularly concerning functional outcomes (2, 3), neurodevelopment (3, 4), and exercise capacity (5, 6).

There are only a few pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs and there is little published research about their effectiveness. Recent research showed that almost half of patients that undergo surgery for CHD required some sort of rehabilitation therapy in the acute postoperative period (2). In contrast, in adults with acquired heart disease, the benefits of post-surgical cardiac rehabilitation have been widely proven. However, only 10%–20% of those adult patients who would benefit from this type of intervention participate in a rehabilitation program (7).

Rehabilitation management of pediatric cardiac patients frequently starts in the inpatient acute setting, especially for children with severe cardiac defects who spend a significant amount of time in the hospital, and it continues in the outpatient setting (2). Of those pediatric programs documented in the literature, most use a team format, and they include inpatient acute care programs, home-based programs, and outpatient-based programs. The outpatient exercise training programs have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of their particular models of management, and they measure patient improvement using outcome metrics such as maximal oxygen consumption, exercise tolerance, and quality of life (8).

We offer these definitions for the reader's ease:

“Neurodevelopment” refers to the neurologic and developmental trajectory of a child.

“Functional outcomes” refer to the neurodevelopmental trajectory of children as well as their reported re-integration into their communities, ability to gain independence, and overall quality of life.

“Function” is a key tenet in rehabilitation and encompasses all aspects of daily life, including mobility, communication, feeding, and other activities of daily living.

“Rehabilitation management” includes an interdisciplinary approach to improving function as defined previously. We include key components of this rehabilitation team further in this paper.

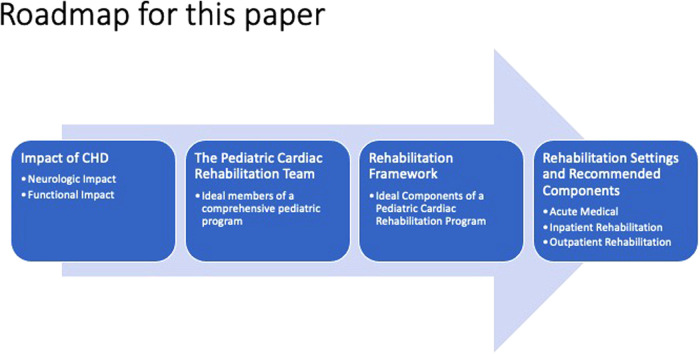

In this paper, we briefly discuss the functional deficits in CHD and then explore the potential role of each member of the multidisciplinary pediatric cardiac rehabilitation team in addressing them (Table 1). We then propose a framework for multidisciplinary pediatric cardiac rehabilitation in both inpatient and outpatient settings (Figure 1), and we highlight the unique considerations of such programs for pediatric CHD vs. those addressing adult-acquired heart disease.

Table 1.

Roles of the multidisciplinary team.

| Team member | Role |

|---|---|

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation Physicians (Pediatric Physiatrists) |

|

| Cardiologists/cardiovascular surgeons |

|

| Nursing |

|

| Exercise physiologist |

|

| Speech-language Pathologists |

|

| Physical therapists |

|

| Occupational Therapists |

|

| Psychologists and neuropsychologists |

|

Figure 1.

Roadmap.

2. Our goal

Our goal is to provide a framework for developing a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program to improve long-term function and quality of life for pediatric patients with CHD. In the course of this paper we will:

-

•

Increase awareness of specific functional complications related to CHD

-

•

Provide a rehabilitation framework for pediatric patients with CHD

-

•

Offer recommendations to decrease the functional impact of CHD surgery and associated complications

-

•

Provide recommendations to improve the quality of life in pediatric patients with CHD

-

•

Give guidance on educating parents and patients to help decrease anxiety regarding physical activity

-

•

Promote a cardio-healthy lifestyle with physical activity and an appropriate heart-healthy diet, decrease CV risk factors, and increase medication compliance

-

•

Demonstrate how to provide functional support throughout childhood and into adulthood

-

•

Provide guidance on helping pediatric patients achieve maximum independence

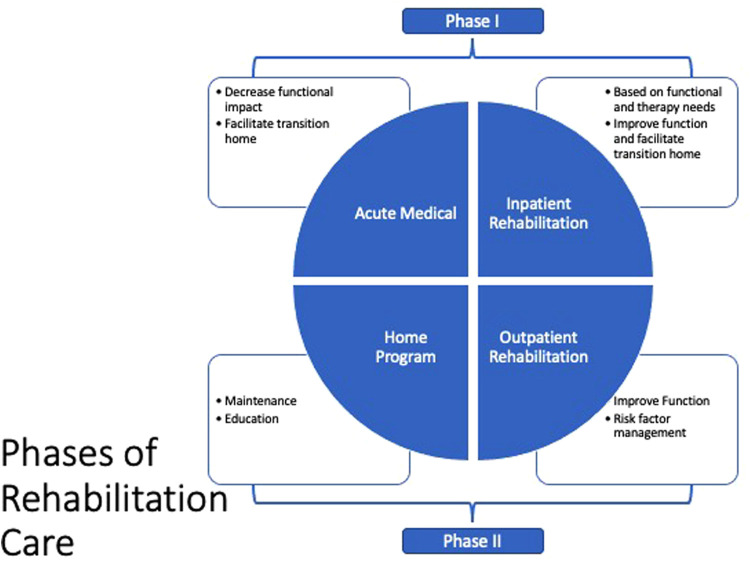

We believe there are two essential time points for providing rehabilitation care for pediatric patients with CHD (Figure 2).

Acute post-surgery (Phase I): In this period, the aim is to decrease the acute functional impact of the surgical intervention and possible post-surgical complications, and facilitate the transition home. Acute post-surgery care can take place in the acute medical setting, acute inpatient rehabilitation or a long-term acute care setting. This phase is more relevant in CHD vs. adults with acquired heart disease.

Post-surgery (Phase II): This subacute phase, which is analogous to the same phase in acquired heart disease, includes exercise training for older pediatric patients and cardiovascular risk factor management adapted to the functional needs of the pediatric patient population. Additional outpatient rehabilitation therapy services may also be needed.

Figure 2.

Rehabilitation settings.

3. Functional deficits in CHD

3.1. Neurologic

Children born with complex CHD have smaller and more immature brains at birth compared to children without CHD (9). This brain immaturity could increase the risk of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), which is associated with cerebral palsy, after cardiac surgery. The most common cause of stroke in children is CHD itself or the surgery for CHD. Additionally, brain injury affects 55% of neonates in the peri-cardiac surgery period, with most of these cases being PVL (10). In patients who require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support, stroke incidence is higher—around 12.3% (11). For patients who required a ventricular assist device (VAD), the incidence of having at least one stroke is 29% (12). This neurologic injury makes them susceptible to having some form of motor, speech, cognitive, or feeding disability, which in turn affects their activities of daily living.

Longer-term abnormal neurodevelopment outcomes have been extensively described in patients with CHD (3, 13). These deficits are varied, affecting areas of functioning such as language (14), executive function (15), and visual processing (16) skills, and they can adversely affect school performance and quality of life. Multiple risk factors have been identified, including chronic cyanosis, genetic and syndromic abnormalities, medical and surgical therapies, brain injury, comorbidities, and a lack of exposure to normal developmental stimuli in the intensive care unit (ICU) (13).

As more neurodevelopmental follow-up programs are established and refined, neurologists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, and other health providers have outlined their experiences and recommendations for the care of children with congenital heartdefects (17, 18). In addition, the American Heart Associationandthe American Academy of Pediatrics have published their respective guidelines for the evaluation and management of developmental and neuropsychological outcomes among children with CHD (13). Most recently, the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative provided guidance on developmental evaluations from birth through age 5 and on neuropsychological evaluations for school-age children (18, 19).Although these collective recommendations and guidelines arecritical in directingthe neurodevelopmental care of childrenwith CHD, theydo not specifically address the functionalneeds of CHD patients. Our framework attempts to fill this critical gap.

3.2. Feeding

Feeding difficulties are not uncommon in patients with CHD (20). Up to 50% of neonates with complex CHD require tube feeding at discharge following cardiac surgery (21). These feeding disorders can persist over time in over 20% of these patients (22). The etiology of feeding difficulties is thought to be multifactorial: abnormal development of the operculum in the brain of patients with complex CHD that is related to feeding and speech difficulties (9); decreased intake or increased energetic expenditure in heart failure (23); brain injury (24); vocal cord dysfunction (25); suck-swallow-breathe discoordination; laryngopharyngeal dysfunction (26); and reflux or oral aversion after prolonged intubation. Feeding difficulties can lead to complications such as aspirations (27), prolonged hospitalization, and, importantly, an adverse effect on patients' growth and development (28).

3.3. Speech and language

In CHD, speech and language difficulties include delays and/or impairments in the motor and cognitive aspects of communicative functioning (29–31), which can range in severity from mild to severe. Deficits in speech production, including articulation or phonological disorders, motor speech disorders, voice and/or resonance disorders, and dysfluencies may also be present (32). Patients are at risk of receptive and/or expressive language difficulties, as well as challenges in social pragmatics that may be part of autism spectrum disorder or in isolation (29, 33). Finally, it is not uncommon in this patient population to observe language-based learning disabilities and deficits in attention and executive functioning, which can also impact communicative functioning (34).

3.4. Exercise capacity

An active lifestyle plays a critical role in health outcomes. As noted above, neurological and cognitive impairments can also impact exercise capacity and physical activity. Thus, it is important to consider all aspects of health-related fitness. This is important because exercise and physical activity are two different constructs (the former is a subcomponent of the latter) and each can result in different outcomes, all of which are important to long-term health in complex CHD.

Patients with complex CHD tend to have lower median oxygen consumption (peak VO2), the gold standard measurement of peak aerobic exercise capacity (35), which in this patient population is related to morbidity and mortality (6, 36). A number of studies have shown that decreased exercise capacity can improve with physical activity in patients with CHD (37). Limited literature is available at this time on pediatric CHD patients and improvement in outcomes. However, recent data suggests that exercise training in children with CHD may improve exercise parameters as well as quality of life, without serious adverse outcomes (38, 39). In addition to peak VO2, it is important to understand other health-related components of a patient's fitness, including movement deficits, muscular fitness, barriers to physical activity, and physical activity preferences.

4. The rehabilitation framework

We believe rehabilitation intervention in CHD patients should be a multidisciplinary team effort. We describe the potential team members and their roles in Table 1. While the roles are described as independent, there is significant overlap between different professionals in both assessments and interventions. Different functional impairments might be addressed in multiple rehabilitation therapy domains, such as deconditioning or weakness treated with both physical therapy and exercise training.

4.1. Inpatient rehabilitation in CHD (Phase I)

Inpatient rehabilitation generally takes place in the hospital setting after cardiac surgery or hospitalization for heart failure. With guidance from the cardiology and cardiovascular surgery team, plans for therapeutic rehabilitation interventions should be developed and initiated as soon as possible to optimize mobility and prevent complications during the post-CHD and -transplant surgical course. As most acute medical inpatient settings have limited physical and occupational therapy resources, inpatient rehabilitation management frequently falls to the bedside nursing staff. Nurses are also among the first care team members to interact with and assess post-operative patients; in the ICU, early assessment and recognition of neurological, vocal, feeding, and motor abilities begin immediately after surgery thus increasing the opportunity for more timely rehabilitation interventions.

While monitoring the patient's tolerance to aerobic and therapeutic exercise, physiatrists can ensure therapeutic activities are aligned with the patient's goals, medical status, and function. During the hospital course, the physiatrist will assess and determine the appropriate level of rehabilitation services required after discharge, such as inpatient rehabilitation, an intensive day rehabilitation program, or an outpatient rehabilitation plan. Maintenance of safe activity is critical at this juncture to mitigate the effects of debility known to occur in the acute inpatient setting. In the pediatric population, minimal adverse outcomes have been reported with early mobilization programs and they are often used by bedside nursing (40).

There is already a precedent for inpatient pediatric rehabilitation for patients with heart failure and for those with ventricular assist devices (8). Patients in these programs have, on average, three to five sessions of therapy per week, with no adverse effects reported. With this existing framework in mind, we make the following proposals for implementing a pediatric rehabilitation program in the inpatient setting.

4.1.1. Nursing

Nurses are unique in that they are among the first team members to assess patients' functional health and they also spend the most direct care time with patients. Nursing assessments, therefore, provide early and rapid evaluation of potential threats to functional health, allowing for more timely communication with the overseeing provider and necessary specialists. Nursing is also able to institute supportive interventions for vocal, feeding, and motor disabilities before a patient is deemed ready for formal physical and occupational therapies. Once a patient is screened by physiatry and the rehabilitation therapists, nursing plays an essential role in ensuring therapy recommendations are tolerated by the patient and, if so, followed. Nursing also plays a large role in patient education, including but not limited to medication management, symptom awareness and management, and discharge readiness, all of which are specific to each patient. When transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation facility is likely, nursing plays a significant role in guiding and preparing the patient and family for that transition.

4.1.2. Physical and occupational therapy

Physical and occupational therapy plays a vital role in caring for pediatric patients who are hospitalized for CHD. These patients are at increased risk of prolonged immobility, which often results in long-term sequelae that can be best supported through a wide range of therapeutic activities. These activities begin with early mobilization, i.e., a patient's active participation in therapeutic activity within 48–72 h of admission, upon hemodynamic stability, or when the medical team deems it appropriate (40, 41).

The goals of care for physical therapy and occupational therapy are to maximize functional mobility and independence while minimizing the deleterious effects of bedrest and to prevent deconditioning; to assess and facilitate achievement of developmental milestones and to help provide appropriate recommendations for follow-up services upon discharge.

The child should be examined and evaluated for physical and occupational therapy, with individualized interventions (Tables 2–4) recommended that are neurodevelopmentally appropriate and specific to the child's functional deficits.

Table 2.

Clinical assessment and education considerations for physical and occupational therapy.

| Review of the electronic medical record and patient/family interview |

|---|

|

| Parent and patient education |

|

Table 4.

Assessment and intervention considerations for occupational therapy (as applicable, assessment and intervention should be patient specific and not all of the following variables may be included depending on patients age, cognitive level, needs, etc.)

| Assessment domain | Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Activities of daily living |

|

|

| Aerobic capacity/endurance |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal screen |

|

|

ADLs activity of daily living, HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, RPP rate pressure product, RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and METS metabolic equivalents, O2 sat oxygen saturation.

Table 3.

Assessment and intervention considerations for physical therapy (as applicable, assessment and intervention should be patient specific and not all of the following variables may be included depending on patients age, cognitive level, needs, etc.).

| Assessment domain | Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic capacity/endurance |

|

|

| Mobility |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal screen |

|

|

HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and METS metabolic equivalents, O2 sat oxygen saturation.

4.1.3. Speech and language therapy

Children with CHD are vulnerable to speech and language delays (29–31) which may warrant consultation with speech and language pathologist (SLP) services. These include baseline communication challenges, acute changes (e.g., due to stroke, vocal cord paralysis, ventilation requirements, etc.), or the effects of prolonged hospitalization. Early consultation may facilitate ongoing developmental support, communication access and patient-provider communication, and maintenance of skills. Table 5 outlines additional considerations for inpatient assessment of, and interventions for, speech, language, and communication needs in children with CHD.

Table 5.

Assessment and intervention considerations for speech, language, and communication: (as applicable, assessment and intervention should be patient specific and not all of the following variables may be included depending on patients age, cognitive level, needs, etc.).

| Assessment domain | Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bedside environment |

|

|

| Cognition |

|

|

| Sensory profile |

|

|

| Expressive communication |

|

|

| Receptive communication |

|

|

| Literacy |

|

|

| Physical communication access |

|

|

| Vocabulary selection |

|

|

4.1.4. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

If a patient presents as non-speaking or with functional communication difficulty (e.g., due to mechanical ventilation), the use of AAC strategies may be required to establish reliable communication during hospitalization (45). The SLP should conduct a feature-matched assessment by matching the patient's strengths, skills, and needs to available tools and strategies (46), which may include a variety of no-tech, low-tech (e.g., communication boards, writing tools), and high-technology (e.g., speech-generating devices). If the child has receptive language issues, communication partners can use strategies to supplement language input. It should be noted that AAC does not impede the development of spoken language (47, 48) and may in fact increase speech production (49).

4.1.5. Feeding and swallowing

Regardless of cardiac anatomy, all patients with CHD are at risk for feeding difficulties (50), failure to thrive, and dysphagia (20). Feeding difficulties and dysphagia are thought to be related to many of the concomitant issues mentioned above. Many newborns are discharged home with feeding tubes, given the difficulty of transitioning to full oral feeds (51). Infants benefit from early feeding interventions pre-operatively, as well as post-operatively, to avoid the need for gastrostomy placement (52). Research has demonstrated that infants with feeding difficulties are at increased risk of feeding struggles that persist in childhood (50), and therefore early speech-language pathology involvement is imperative.

Feeding assessment and management both for the in- and outpatient setting are further detailed in Tables 6, 7.

Table 6.

General assessment considerations for feeding.

| Assessment considerations |

|---|

| Review of the electronic medical record |

|

| Obtain feeding history through chart review and parent report |

|

NGT, nasogastric tube; GT, gastric tube.

Table 7.

Feeding and swallowing Management in the pediatric acute in and outpatient care setting: Assessment considerations (as applicable, assessments should be patient specific and not all of the following variables may be included during assessment depending on the patient's age, cognitive level, risk assessment, etc.) the screening, assessment, and intervention should be patient-specific and account for neurological etiology (e.g. stroke), cognition (e.g. attention to task, sedation, etc.), sensory domains (e.g. vision and hearing), and age.

| Assessment domain | Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Pre-feeding intervention

|

|

|

|

|

Assess feeding skills during an oral trial:

|

Changes in nipple flow rate.

|

|

|

Feeding environment

|

MBBS modified barium swallow study, FEES fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing.

4.1.6. Psychology and neuropsychology

4.1.6.1. Psychological and neuropsychological screening

Children in ICUs and those in inpatient medical and rehabilitation units can benefit from systematic and focused psychological and neuropsychological consultation to: identify those with the highest risk of developmental, cognitive, and psychosocial concerns; aid with connecting patients and families with needed support; prepare children and families for the next stages of recovery; and provide guidance on additional neuropsychologic and developmental evaluation throughout recovery (58, 59). For more details see Table 8.

Table 8.

Psychological and neuropsychological evaluation and intervention.

| Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations | |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient developmental care |

|

|

| Developmental and neuropsychological evaluations |

|

|

| Cognitive Rehabilitation and Academic Remediation |

|

|

| Mental Health Care |

|

|

| Family Mental Health Care |

|

|

A portion of children in cardiac ICUs display delirium, a clinical syndrome with acute disturbance in consciousness and cognition that can fluctuate throughout the day (70). In many ICUs, regular screening for delirium is being implemented. However, it should be noted that patients can screen positive for delirium in cases of hypnotic-related iatrogenic withdrawal (71), the anticholinergic syndrome (72), brain injury, developmental delays, or neuroirritability. Misdiagnoses have significant implications for medical management and outcomes (73). Even though the symptoms of many patients with delirium resolve rapidly (likely because the delirium was a temporary effect of anesthesia or sedation), a portion have persistent symptoms during their intensive care stay.

4.1.6.2. Psychological care

Families of infants with CHD need family-centered care in cardiac ICUs, as the stress of hospitalization can have long-lasting developmental and psychosocial implications (21). Pediatric mental health providers should be readily available in inpatient units, not only to address the distress associated with critical illness and lengthy hospital stays but also to foster healthy behaviors, promote treatment compliance, and help develop self-efficacy (74). This is particularly important for older children and adolescents. Psychological care is further detailed in Table 8.

4.1.7. Discharge planning from acute in-hospital stays

Patients may require additional rehabilitation support upon discharge, depending on the complexity of their cardiac disease and their medical needs, skilled nursing needs, and functional level at discharge. This additional support may include acute inpatient rehabilitation, outpatient interventions, or home-based care.

Inpatient options:

-

•

Discharge to acute inpatient rehabilitation, in which the focus is on the continued delivery of acute medical management, required skilled nursing care, and intensive attention to function. Patients receive three hours of rehabilitation therapy per day.

-

•

Discharge to long-term acute care (LTAC), where the goal is to provide medical management and necessary skilled nursing care. There is no minimum amount of required therapy.

Outpatient options:

-

•

Discharge to early intervention services or school-based therapies, pending qualification for such services.

-

•

Discharge to an outpatient rehabilitation therapy program.

-

•

School-based rehabilitation therapies and accommodations.

4.2. Outpatient Rehabilitation Program (Phase II)

Outpatient rehabilitation for children is equivalent to Phase II of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Adults with Acquired Heart Disease. However, since surgery in pediatric patients can occur in infancy or early childhood, outpatient rehabilitation may need to be initiated several years after the initial surgery. This is because certain functional difficulties or disabilities may not be recognized until several years after initial surgery and/or the patients might be too young to participate in certain types of rehabilitation therapy. However, when feasible, interventions should start early and be adapted to the appropriate developmental needs of each CHD patient.

This phase of rehabilitation should include aspects of the more classical cardiac rehabilitation program suggested by the American Heart Association (AHA) (75) and American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACPVR) (76), such as exercise training, but adapted to meet the unique rehabilitation needs of children and adolescents (as previously described in these recommendations).

4.2.1. Physical and occupational therapy

Physical and occupational therapy are an essential part of the outpatient rehabilitation program. The goals, assessments, and interventions of both physical and occupational therapy are similar in the inpatient and outpatient settings. These have been extensively detailed in our recommendations for inpatient care and would similarly apply to the outpatient setting (Tables 2–4).

4.2.2. Exercise training

Low exercise capacity is a predictor of hospitalization and death for children with CHD (5, 36). A number of studies have demonstrated that exercise training improves peak VO2 after CHD surgery in children and adolescents (37, 77–79) and no adverse effects have been noted (Tables 9–11).

Table 9.

General considerations for exercise training.

| Assessment considerations |

|---|

| Review of the electronic medical record |

|

| Obtain exercise history through chart review and parent/child report |

|

Table 11.

Precautions and considerations for exercise training in congenital heart disease.

| Recommendations/precautions by type of CHD (85) |

|---|

| Certain hereditary cardiomyopathy, long QT syndrome, other congenital channelopathies, and congenital coronary artery anomalies that can cause arrhythmias considered higher risk for arrhythmias. These patients should follow recommendations from the Heart Rhythm Society Guidelines (93) |

Patients with these conditions are encouraged to participate in activities with low-moderate dynamic and static component (94):

|

Table 10.

Exercise training program.

| Assessment domain | Assessment considerations | Intervention considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased exercise capacity (39, 80–82) | An initial cardiopulmonary exercise test to understand decreased exercise capacity, safety and guide intervention | Currently no consensus on risk stratification:

|

| General CHD Counseling | Assess:

|

|

| Physical Activity Counseling (85–87) |

|

|

The goal of outpatient exercise training (both pre- and postoperatively) is to not only improve exercise capacity and physical activity but also provide the patient with tools and support to become as functional and independent as possible and to improve their overall quality of life. Over the past few years, there has been a major effort to develop more structured cardiac rehabilitation/exercise training programs (39, 80, 81) to provide a framework for these types of interventions. However, the effect of structured rehabilitation/exercise training programs on patient outcomes has yet to be demonstrated.

4.2.3. Speech and language therapy

4.2.3.1. Outpatient speech and language assessment

Throughout their childhood, children with CHD often require periodic monitoring of their speech and language development on an outpatient basis (13). Assessments provided by a speech-language pathologist consider the child's age, individual needs and skills, and etiology of deficits (e.g., developmental vs. acquired). Evaluations may target a range of speech, language, pragmatic, and cognitive skills using standardized testing, criterion-referenced measures, and clinical observation to collect diagnostic information (31). Table 5 outlines possible components and considerations for a comprehensive evaluation of speech, language, and related skills in children with CHD.

4.2.3.2. Outpatient speech and language intervention

The typical goal of speech and language intervention is to optimize overall communicative function, thereby supporting social and academic potential, enhancing emotional well-being, reducing frustration, and improving overall quality of life. Treatment frequency and intensity may change over time based on the number and types of skill areas targeted and the consolidation of learned skills (95–98). Outpatient therapies may be supported in community clinics (e.g., hospital or private clinics and centers), early intervention programs, or in schools (in either individual or group settings.) Children less able to use spoken language to support daily communication may also need augmentative and alternative communication strategies. Over time, changes in health status or the need for subsequent cardiac surgery may impact communication skills and/or the type of intervention approach required to maximize benefit. Therefore, ongoing monitoring and multidisciplinary coordination are recommended. Table 5 details outpatient speech assessment and intervention.

4.3. Feeding and swallowing

4.3.1. Outpatient feeding and swallowing evaluation

Evaluation of feeding and swallowing function is based on current skills, age, nutritional needs, and parental preferences/concerns. Those who required assisted feeding preoperatively are at greater risk of being discharged with a feeding tube (51). For infants, assessment typically focuses on bottle feeding and/or breastfeeding, with a comprehensive evaluation of the infant's sucking skills, coordination of the nutritive sucking pattern, and endurance for feeding. Infants who undergo cardiac surgery within the first month of life may demonstrate feeding difficulties that span the first two or more years of life (99) and therefore benefit from subsequent evaluation. Assessments in children focus on a larger variety of drinking delivery methods and food textures to evaluate oral motor skills, swallowing, and sensory-based feeding difficulties. Table 6 further outlines feeding and swallowing assessment methods and considerations for infants and children with CHD (Table 6).

4.3.2. Outpatient feeding and swallowing intervention

Outpatient feeding and swallowing intervention plans are determined based on the evaluation of patients’ skills, areas of need, age, and service availability. Infant feeding treatment typically targets changes in the feeding environment, positioning during feeding, nipple flow rate, or other therapeutic interventions to improve the feeding dynamic. As indicated, treatment may also target oral aversion and feeding difficulties for infants who do not yet accept oral feeding. Therapeutic interventions are recommended when aspiration is observed during the instrumental assessment. When patients do not respond to these interventions, altered liquid consistencies may be trialed with close monitoring and in collaboration with the medical team due to potential gastrointestinal morbidities.

Children may present with feeding difficulties that are multi-factorial, including oral-motor delays, sensory-based difficulties, learned behavioral difficulties, and ongoing or newly acquired aspiration. Longer-term intervention plans may be established to support these needs. Given the sometimes slow and gradual progression of skills and potentially complex difficulties demonstrated by children, caregiver education and counseling are also typically provided (Table 7).

4.4. Psychology and neuropsychology

4.4.1. Psychological and neuropsychological evaluations

Patients with CHD should be screened for developmental, neuropsychological, and psychosocial concerns in the outpatient setting; this can help the rehabilitation team individualize targets and services for each patient. For guidelines on the recommended timing of follow-up evaluations, assessment tools, and special testing considerations, readers are referred to the guidelines for neurodevelopmental follow-up clinics with children with congenital heart defects (13, 18, 19) (Table 8).

4.4.2. Psychological care

Psychologists and neuropsychologists in outpatient rehabilitation programs can provide cognitive rehabilitation designed to teach specific cognitive skills and establish compensatory mechanisms for impaired cognitive domains (Table 8). Psychologists can also help foster healthy behaviors; promote treatment compliance; address emotional distress, disruptive behaviors, and social skills deficits; and support pain management and sleep hygiene. Some patients might benefit from additional evaluation by psychiatry. In addition, psychologists may be involved in mental health interventions for families, who are at risk of traumatic stress and other concerns (100) and whose mental health can impact the beneficial effect of exercise training programs on pediatric patients' quality of life (101).

Psychological care may improve not only psychosocial health but also physical health. In a meta-analysis of 23 randomized controlled trials involving adult cardiac patients, psychological care reduced emotional distress and improved systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and cholesterol levels (101). In a study of a pediatric cardiac rehabilitation program with a stress management component, physiological measurements were similarly improved, although the study did not separate the effects of exercise training, health education, and stress management (67). Research has also found associations between physical and emotional health among youths who have completed cardiac rehabilitation (102), and between emotional health and daily physical activity among children with CHDs (38).

5. Discussion

Rehabilitation needs in pediatric patients with CHD are very different from those of adults with acquired heart disease. As such, rehabilitation programs for patients with CHD should be designed to support the array of functional difficulties described here, and this article provides a valuable framework for developing such programs. Given the lack of available literature and data on pediatric cardiac rehabilitation, we developed this framework based on expert recommendations regarding best practices. The individuals contributing to this article respectively have expertise in rehabilitation, cardiology, cardiac surgery, and neuropsychology, all with a specific focus on our target pediatric population. Our framework addresses rehabilitation in both the inpatient and outpatient settings and incorporates roles for a multidisciplinary pediatric cardiac rehabilitation team. Further research is needed to quantify the impact of these multidisciplinary interventions and help us continue to tailor these programs to the specific needs of the pediatric cardiac population.

Author contributions

AT and UA contributed to guideline conception, design, writing and editing of the paper. JV, LH, MC, KC, RS, LS, KW, DB, NG, TP, JB, SC, MG, MN. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Oster ME, Lee KA, Honein MA, Riehle-Colarusso T, Shin M, Correa A. Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. (2013) 131(5):e1502–8. 10.1542/peds.2012-3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ubeda Tikkanen A, Nathan M, Sleeper LA, Flavin M, Lewis A, Nimec D, et al. Predictors of postoperative rehabilitation therapy following congenital heart surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. (2018) 7(10):e008094. 10.1161/JAHA.117.008094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White BR, Rogers LS, Kirschen MP. Recent advances in our understanding of neurodevelopmental outcomes in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2019) 31(6):783–8. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellinger D, Newburger J. Neuropsychological, psychosocial, and quality-of-life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. (2010) 29(2):87–92. 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2010.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes SM, Alexander ME, Graham DA, Khairy P, Clair M, Rodriguez E, et al. Exercise testing identifies patients at increased risk for morbidity and mortality following fontan surgery. Congenit Heart Dis. (2011) 6(4):294–303. 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giardini A, Hager A, Lammers AE, Derrick G, Muller J, Diller GP, et al. Ventilatory efficiency and aerobic capacity predict event-free survival in adults with atrial repair for complete transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2009) 53(17):1548–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. (2001) 345(12):892–902. 10.1056/NEJMra001529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akamagwuna U, Balady D. Pediatric cardiac rehabilitation: a review. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. (2019) 7(2):67–80. 10.1007/s40141-019-00216-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Licht DJ, Shera DM, Clancy RR, Wernovsky G, Montenegro LM, Nicolson SC, et al. Brain maturation is delayed in infants with complex congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2009) 137(3):529–36; discussion 536–7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyvandi S, Chau V, Guo T, Xu D, Glass HC, Synnes A, et al. Neonatal brain injury and timing of neurodevelopmental assessment in patients with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 71(18):1986–96. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werho DK, Pasquali SK, Yu S, Donohue J, Annich GM, Thiagarajan RR, et al. Epidemiology of stroke in pediatric cardiac surgical patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. (2015) 100(5):1751–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan LC, Ichord RN, Reinhartz O, Humpl T, Pruthi S, Tjossem C, et al. Neurological complications and outcomes in the Berlin heart EXCOR® pediatric investigational device exemption trial. J Am Heart Assoc. (2015) 4(1):e001429. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2012) 126(9):1143–72. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calderon J, Willaime M, Lelong N, Bonnet D, Houyel L, Ballon M, et al. Population-based study of cognitive outcomes in congenital heart defects. Arch Dis Child. (2018) 103(1):49–56. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanz JH, Wang J, Berl MM, Armour AC, Cheng YI, Donofrio MT. Executive function and psychosocial quality of life in school age children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. (2018) 202:63–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bean Jaworski JL, White MT, DeMaso DR, Newburger JW, Bellinger DC, Cassidy AR. Visuospatial processing in adolescents with critical congenital heart disease: organization, integration, and implications for academic achievement. Child Neuropsychol. (2018) 24(4):451–68. 10.1080/09297049.2017.1283396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy AR, Ilardi D, Bowen SR, Hampton LE, Heinrich KP, Loman MM, et al. [Formula: see text]congenital heart disease: a primer for the pediatric neuropsychologist. Child Neuropsychol. (2018) 24(7):859–902. 10.1080/09297049.2017.1373758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Butcher JL, Latal B, Sadhwani A, Rollins CK, Brosig Soto CL, et al. Neurodevelopmental evaluation strategies for children with congenital heart disease aged birth through 5 years: recommendations from the cardiac neurodevelopmental outcome collaborative. Cardiol Young. (2020) 30(11):1609–22. 10.1017/S1047951120003534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilardi D, Sanz JH, Cassidy AR, Sananes R, Rollins CK, Ullman Shade C, et al. Neurodevelopmental evaluation for school-age children with congenital heart disease: recommendations from the cardiac neurodevelopmental outcome collaborative. Cardiol Young. (2020) 30(11):1623–36. 10.1017/S1047951120003546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai H, Lim A. Neurodevelopmental intervention strategies to improve oral feeding skills in infants with congenital heart defects. ASHA Perspectives. (2019) 4(6):1492–7. 10.1044/2019_PERS-SIG13-2019-0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medoff-Cooper B, Ravishankar C. Nutrition and growth in congenital heart disease: a challenge in children. Curr Opin Cardiol. (2013) 28(2):122–9. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835dd005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurer I, Latal B, Geissmann H, Knirsch W, Bauersfeld U, Balmer C. Prevalence and predictors of later feeding disorders in children who underwent neonatal cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. (2011) 21(3):303–9. 10.1017/S1047951110001976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwalbe-Terilli CR, Hartman DH, Nagle ML, Gallagher PR, Ittenbach RF, Burnham NB, et al. Enteral feeding and caloric intake in neonates after cardiac surgery. Am J Crit Care. (2009) 18(1):52–7. 10.4037/ajcc2009405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh A, Tabbutt S, Xu D, Barkovich AJ, Miller S, McQuillen P, et al. Impact of perioperative brain injury and development on feeding modality in infants with single ventricle heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. (2019) 8(10):e012291. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner ML, Halstead LA, Rubinstein CS, Atz AM, Andrews D, Bradley SM. Laryngopharyngeal dysfunction after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2005) 130(5):1293–301. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies RR, Carver SW, Schmidt R, Keskeny H, Hoch J, Pizarro C. Laryngopharyngeal dysfunction independent of vocal fold palsy in infants after aortic arch interventions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2013) (2):617–24.e2. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karsch E, Irving SY, Aylward BS, Mahle WT. The prevalence and effects of aspiration among neonates at the time of discharge. Cardiol Young. (2017) 27(7):1241–7. 10.1017/S104795111600278X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medoff-Cooper B, Irving SY, Hanlon AL, Golfenshtein N, Radcliffe J, Stallings VA, et al. The association among feeding mode, growth, and developmental outcomes in infants with Complex congenital heart disease at 6 and 12 months of age. J Pediatr. (2016) 169:154–9.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fourdain S, St-Denis A, Harvey J, Birca A, Carmant L, Gallagher A, et al. Language development in children with congenital heart disease aged 12–24 months. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. (2019) 23(3):491–9. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nattel SN, Adrianzen L, Kessler EC, Andelfinger G, Dehaes M, Côté-Corriveau G, et al. Congenital heart disease and neurodevelopment: clinical manifestations, genetics, mechanisms, and implications. Can J Cardiol. (2017) 33(12):1543–55. 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solot CB, Sell D, Mayne A, Baylis AL, Persson C, Jackson O, et al. Speech-Language disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: best practices for diagnosis and management. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. (2019) 28(3):984–99. 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-16-0147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hövels-Gürich HH, Bauer SB, Schnitker R, Willmes-von Hinckeldey K, Messmer BJ, Seghaye MC, et al. Long-term outcome of speech and language in children after corrective surgery for cyanotic or acyanotic cardiac defects in infancy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. (2008) 12(5):378–86. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonini TN, Dreyer WJ, Caudle SE. Neurodevelopmental functioning in children being evaluated for heart transplant prior to 2 years of age. Child Neuropsychol. (2018) 24(1):46–60. 10.1080/09297049.2016.1223283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venchiarutti M, Vergine M, Zilli T, Sommariva G, Gortan AJ, Crescentini C, et al. Neuropsychological impairment in children with class 1 congenital heart disease. Percept Mot Skills. (2019) 126(5):797–814. 10.1177/0031512519856766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inuzuka R, Diller GP, Borgia F, Benson L, Tay EL, Alonso-Gonzalez R, et al. Comprehensive use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing identifies adults with congenital heart disease at increased mortality risk in the medium term. Circulation. (2012) 125(2):250–9. 10.1161/circulationaha.111.058719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diller GP, Giardini A, Dimopoulos K, Gargiulo G, Muller J, Derrick G, et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in contemporary fontan patients: results from a multicenter study including cardiopulmonary exercise testing in 321 patients. Eur Heart J. (2010) 31(24):3073–83. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ubeda Tikkanen A, Opotowsky AR, Bhatt AB, Landzberg MJ, Rhodes J. Physical activity is associated with improved aerobic exercise capacity over time in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168(5):4685–91. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, Rabideau N, Fulton DR, Gauthier NS, et al. Sustained effects of cardiac rehabilitation in children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. (2006) 118(3):e586–93. 10.1542/peds.2006-0264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duppen N, Takken T, Hopman MT, ten Harkel AD, Dulfer K, Utens EM, et al. Systematic review of the effects of physical exercise training programmes in children and young adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168(3):1779–87. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.05.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuello-Garcia CA, Mai SHC, Simpson R, Al-Harbi S, Choong K. Early mobilization in critically ill children: a systematic review. J Pediatr. (2018) 203:25–33.e6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Association APT. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.

- 42.Hashem MD, Nelliot A, Needham DM. Early mobilization and rehabilitation in the ICU: moving back to the future. Respir Care. (2016) 61(7):971–9. 10.4187/respcare.04741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clifton A, Cruz G, Patel Y, Cahalin LP, Moore JG. Sternal precautions and prone positioning of infants following median sternotomy: a nationwide survey. Pediatr Phys Ther. (2020) 32(4):339–45. 10.1097/PEP.0000000000000734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitchford EA, Webster EK. Clinical validity of the test of gross motor development-3 in children with disabilities from the U.S. national normative sample. Adapt Phys Activ Q. (2021) 38(1):62–78. 10.1123/apaq.2020-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blackstone SW, Beukelman DR, Yorkston KM. Patient-Provider communication: Roles for speech-language pathologists and other health care professionals. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beukelman D, Mirenda P. Augmentative and alternative communication: supporting children and adults with Complex communication needs. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: P.H. Brookes Publishing; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Millar DC, Light JC, Schlosser RW. The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities: a research review. J Speech Lang Hear Res. (2006) 49(2):248–64. 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlosser RW, Wendt O. Effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: a systematic review. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. (2008) 17(3):212–30. 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blischak D, Lombardino L, Dyson A. Use of speech-generating devices: in support of natural speech. Augment Altern Commun. (2003) 19(1):29–35. 10.1080/0743461032000056478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pados BF. Symptoms of problematic feeding in children with CHD compared to healthy peers. Cardiol Young. (2019) 29(2):152–61. 10.1017/S1047951118001981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kogon BE, Ramaswamy V, Todd K, Plattner C, Kirshbom PM, Kanter KR, et al. Feeding difficulty in newborns following congenital heart surgery. Congenit Heart Dis. (2007) 2(5):332–7. 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2007.00121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehrmann DE, Mulvahill M, Harendt S, Church J, Stimmler A, Vichayavilas P, et al. Toward standardization of care: the feeding readiness assessment after congenital cardiac surgery. Congenit Heart Dis. (2018) 13(1):31–7. 10.1111/chd.12550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmeister J, Zaborek N, Thibeault SL. Postextubation dysphagia in pediatric populations: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Pediatr. (2019) 211:126–133.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaker CS. Cue-based feeding in the NICU: using the infant's communication as a guide. Neonatal Netw. (2013) 32(6):404–8. 10.1891/0730-0832.32.6.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Satter E. Eat and feed with joy (Accessed January 18, 2021).

- 56.Ross E, Toomey K. 2011 SOS approach to feeding article ASHA, perspectives on swallowing and swallowing disorders (Dysphagia), Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 58–93. October 2011. Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia). (2019) 20:82–7. 10.1044/sasd20.3.82 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fishbein M, Cox S, Swenny C, Mogren C, Walbert L, Fraker C. Food chaining: a systematic approach for the treatment of children with feeding aversion. Nutr Clin Pract. (2006) 21(2):182–4. 10.1177/0115426506021002182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dodd JN, Hall TA, Guilliams K, Guerriero RM, Wagner A, Malone S, et al. Optimizing neurocritical care follow-up through the integration of neuropsychology. Pediatr Neurol. (2018) 89:58–62. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Treble-Barna A, Beers SR, Houtrow AJ, Ortiz-Aguayo R, Valenta C, Stanger M, et al. PICU-Based Rehabilitation and outcomes assessment: a survey of pediatric critical care physicians. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2019) 20(6):e274–282. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calderon J, Bellinger DC, Hartigan C, Lord A, Stopp C, Wypij D, et al. Improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: protocol for a randomised controlled trial of working memory training. BMJ Open. (2019) 9(2):e023304. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jordan LC, Siciliano RE, Cole DA, Lee CA, Patel NJ, Murphy LK, et al. Cognitive training in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a pilot randomized trial. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. (2019) 57:101185. 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2019.101185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takacs ZK, Kassai R. The efficacy of different interventions to foster children's executive function skills: a series of meta-analyses. Psychol Bull. (2019) 145(7):653–97. 10.1037/bul0000195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gayes LA, Steele RG. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing interventions for pediatric health behavior change. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2014) 82(3):521–35. 10.1037/a0035917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas R, Abell B, Webb HJ, Avdagic E, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Parent-Child interaction therapy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2017) 140(3):e20170352. 10.1542/peds.2017-0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing R, Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2004) 43(8):930–59. 10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klingbeil DA, Renshaw TL, Willenbrink JB, Copek RA, Chan KT, Haddock A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: a comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J Sch Psychol. (2017) 63:77–103. 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palermo TM, Eccleston C, Lewandowski AS, Williams AC, Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. Pain. (2010) 148(3):387–97. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. J Pediatr Psychol. (2014) 39(8):932–48. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bucholz EM, Sleeper LA, Goldberg CS, Pasquali SK, Anderson BR, Gaynor JW, et al. Socioeconomic Status and long-term outcomes in single ventricle heart disease. Pediatrics. (2020) 146(4):e20201240. 10.1542/peds.2020-1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chorna O, Baldwin HS, Neumaier J, Gogliotti S, Powers D, Mouvery A, et al. Feasibility of a team approach to Complex congenital heart defect neurodevelopmental follow-up: early experience of a combined cardiology/neonatal intensive care unit follow-up program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2016) 9(4):432–40. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.002614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Madden K, Burns MM, Tasker RC. Differentiating delirium from sedative/hypnotic-related iatrogenic withdrawal syndrome: lack of specificity in pediatric critical care assessment tools. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2017) 18(6):580–8. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holstege CP, Borek HA. Toxidromes. Crit Care Clin. (2012) 28(4):479–98. 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ubeda Tikkanen A, Kudchadkar SR, Goldberg SW, Suskauer SJ. Acquired brain injury in the pediatric intensive care unit: special considerations for delirium protocols. J Pediatr Intensive Care. (2020) 10(4):243–7. 10.1055/s-0040-1719045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Curran T, Gauthier N, Duty SM, Pojednic R. Identifying elements for a comprehensive paediatric cardiac rehabilitation programme. Cardiol Young. (2020) 30(10):1473–81. 10.1017/S1047951120002346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leon AS, Franklin BA, Costa F, Balady GJ, Berra KA, Stewart KJ, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: an American heart association scientific statement from the council on clinical cardiology (subcommittee on exercise, cardiac rehabilitation, and prevention) and the council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism (subcommittee on physical activity), in collaboration with the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation. Circulation. (2005) 111(3):369–76. 10.1161/01.cir.0000151788.08740.5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rehabilitation AAoCaP. Guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs. 5th ed. Champagne, Il: Human Kinetics; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, Rabideau N, Fulton DR, Gauthier NS, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on the exercise function of children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. (2005) 116(6):1339–45. 10.1542/peds.2004-2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Longmuir PE, Tremblay MS, Goode RC. Postoperative exercise training develops normal levels of physical activity in a group of children following cardiac surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. (1990) 11(3):126–30. 10.1007/BF02238841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Opotowsky AR, Rhodes J, Landzberg MJ, Bhatt AB, Shafer KM, Yeh DD, et al. A randomized trial comparing cardiac rehabilitation to standard of care for adults with congenital heart disease. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. (2018) 9(2):185–93. 10.1177/2150135117752123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tikkanen AU, Oyaga AR, Riano OA, Alvaro EM, Rhodes J. Paediatric cardiac rehabilitation in congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Cardiol Young. (2012) 22(3):241–50. 10.1017/s1047951111002010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ubeda Tikkanen A, Gauthier N. Cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training. In: Rhodes J, Alexander ME, Opotowsky AR, editors. Exercise physiology for the pediatric and congenital cardiologist. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; (2019). p. 201–8. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gauthier N, Curran T, O'Neill JA, Alexander ME, Rhodes J. Establishing a comprehensive pediatric cardiac fitness and rehabilitation program for congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. (2020) 41(8):1569–79. 10.1007/s00246-020-02413-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Budts W, Pieles GE, Roos-Hesselink JW, Sanz de la Garza M, D'Ascenzi F, Giannakoulas G, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive sport in adolescent and adult athletes with congenital heart disease (CHD): position statement of the sports cardiology & exercise section of the European association of preventive cardiology (EAPC), the European society of cardiology (ESC) working group on adult congenital heart disease and the sports cardiology, physical activity and prevention working group of the association for European paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. (2020) 41(43):4191–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paridon SM, Alpert BS, Boas SR, Cabrera ME, Caldarera LL, Daniels SR, et al. Clinical stress testing in the pediatric age group: a statement from the American heart association council on cardiovascular disease in the young, committee on atherosclerosis, hypertension, and obesity in youth. Circulation. (2006) 113(15):1905–20. 10.1161/circulationaha.106.174375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Takken T, Giardini A, Reybrouck T, Gewillig M, Hovels-Gurich HH, Longmuir PE, et al. Recommendations for physical activity, recreation sport, and exercise training in paediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a report from the exercise, basic & translational research section of the European association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation, the European congenital heart and lung exercise group, and the association for European paediatric cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2012) 19(5):1034–65. 10.1177/1741826711420000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Longmuir PE, Brothers JA, de Ferranti SD, Hayman LL, Van Hare GF, Matherne GP, et al. Promotion of physical activity for children and adults with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2013) 127(21):2147–59. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318293688f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.(CDC) CfDCaP. Physical Activity Recommendations. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/children/index.htm

- 88.Voss C, Dean PH, Gardner RF, Duncombe SL, Harris KC. Validity and reliability of the physical activity questionnaire for children (PAQ-C) and adolescents (PAQ-A) in individuals with congenital heart disease. PLoS One. (2017) 12(4):e0175806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in children: validation of the physical activity enjoyment scale. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2009) 21(S1):S116–129. 10.1080/10413200802593612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stracciolini A, Berbert L, Nohelty E, Zwicker R, Weller E, Sugimoto D, et al. Attitudes and behaviors of physical activity in children: findings from the play, lifestyle & activity in youth (PLAY) questionnaire. PM&R. (2022) 14(5):535–50. 10.1002/pmrj.12794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zamani Sani SH, Fathirezaie Z, Brand S, Pühse U, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Gerber M, et al. Physical activity and self-esteem: testing direct and indirect relationships associated with psychological and physical mechanisms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2016) 12:2617–25. 10.2147/ndt.s116811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Arlinghaus KR, Daundasekara SS, Zaidi Y, Johnston CA. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess barriers and facilitators to physical activity among hispanic youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2021) 53(8):1666–74. 10.1249/mss.0000000000002634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heidbuchel H, Adami PE, Antz M, Braunschweig F, Delise P, Scherr D, et al. Recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activity and competitive sports in patients with arrhythmias and potentially arrhythmogenic conditions: part 1: supraventricular arrhythmias. A position statement of the section of sports cardiology and exercise from the European association of preventive cardiology (EAPC) and the European heart rhythm association (EHRA), both associations of the European society of cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2020) 28(14):1539–51. 10.1177/2047487320925635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mitchell JH, Haskell W, Snell P, Van Camp SP. Task force 8: classification of sports. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 45(8):1364–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Farquharson K, Tambyraja SR, Justice LM. Contributions to gain in speech sound production accuracy for children with speech sound disorders: exploring child and therapy factors. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. (2020) 51(2):457–68. 10.1044/2019_LSHSS-19-00079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yoder P, Woynaroski T, Fey M, Warren S. Effects of dose frequency of early communication intervention in young children with and without down syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. (2014) 119(1):17–32. 10.1352/1944-7558-119.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Justice LM, Logan J, Jiang H, Schmitt MB. Algorithm-Driven dosage decisions (AD3): optimizing treatment for children with language impairment. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. (2017) 26(1):57–68. 10.1044/2016_AJSLP-15-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Allen MM. Intervention efficacy and intensity for children with speech sound disorder. J Speech Lang Hear Res. (2013) 56(3):865–77. 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0076) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Medoff-Cooper B, Irving SY. Innovative strategies for feeding and nutrition in infants with congenitally malformed hearts. Cardiol Young. (2009) 19(Suppl 2):90–5. 10.1017/S1047951109991673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rossi A, De Ranieri C, Tabarini P, Di Ciommo V, Di Donato R, Biondi G, et al. The department of psychology within a pediatric cardiac transplant unit. Transplant Proc. (2011) 43(4):1164–7. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dulfer K, Duppen N, Van Dijk AP, Kuipers IM, Van Domburg RT, Verhulst FC, et al. Parental mental health moderates the efficacy of exercise training on health-related quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. (2015) 36(1):33–40. 10.1007/s00246-014-0961-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Balfour IC, Drimmer AM, Nouri S, Pennington DG, Hemkens CL, Harvey LL. Pediatric cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Dis Child. (1991) 145(6):627–30. 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160060045018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]