Abstract

Background

Electronic health record (EHR) systems are mentioned in several studies as tools for improving healthcare quality in developed and developing nations. However, there is a research gap in presenting the status of EHR adoption in low-income countries (LICs). Therefore, this study systematically reviews articles that discuss the adoption of EHR systems status, opportunities and challenges for improving healthcare quality in LICs.

Methods

We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in articles selected from PubMed, Science Direct, IEEE Xplore, citations and manual searches. We focused on peer-reviewed articles published from January 2017 to 30 September 2022, and those focusing on the status, challenges or opportunities of EHR adoption in LICs. However, we excluded articles that did not consider EHR in LICs, reviews or secondary representations of existing knowledge. Joanna Briggs Institute checklists were used to appraise the articles to minimise the risk of bias.

Results

We identified 12 studies for the review. The finding indicated EHR systems are not well implemented and are at a pilot stage in various LICs. The barriers to EHR adoption were poor infrastructure, lack of management commitment, standards, interoperability, support, experience and poor EHR systems. However, healthcare providers’ perception, their goodwill to use EMR and the immaturity of health information exchange infrastructure are key facilitators for EHR adoption in LICs.

Conclusion

Most LICs are adopting EHR systems, although it is at an early stage of implementation. EHR systems adoption is facilitated or influenced by people, environment, tools, tasks and the interaction among these factors.

Keywords: Electronic Health Records

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Research findings show that electronic health record (EHR)/EMR is being implemented in low-income countries (LICs) despite various challenges influencing its success. However, no empirical evidence is built on systematically collected and analysed studies across LICs that could be used to develop a better implementation strategy.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The study identified that LICs are struggling to adopt EHR systems, but they are failing at the initial stages due to people-related barriers, environment-related barriers, infrastructure-related barriers and poor integration of the system with people.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study could help LICs to properly adopt and use EHR systems considering the barriers identified.

Introduction

According to the WHO definition, quality of healthcare is the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes.1 Currently, with advancements in digital technology, most of the work in the healthcare sector is becoming digitised and efficient.2 This could significantly improve the quality of healthcare3 4 compared with the traditional approach. The electronic health record (EHR) system is at the forefront of implementation in healthcare institutions to enhance the quality of healthcare.5

The EHR system is a digital way of capturing, storing, and using patient information by authorised healthcare providers to deliver healthcare services effectively.6 EHR systems enable data-driven clinical decision-making to improve healthcare quality. Gatiti et al 7 noted that the proper adoption of EHR systems could boost the quality of healthcare by enhancing patient safety and ensuring effective, efficient, timely, equitable and patient-centred care.

Despite the benefits of EHR systems, problems or unintended consequences are hampering the successful adoption and use of EHR systems in healthcare settings. The most common are physician burn-out,8–10 failure of expectations,8 EHR market saturation,8 innovation vacuum,8 data obfuscation,8 interoperability,11 privacy in data sharing,12 protracted to complete tasks,13 interruption of tasks and workarounds at point of care13 and misalignment of technology and clinical context.11 In addition to these, DeWane et al 14 and Gagnon et al 15 noted data duplication errors during decision-making, intermittent system delays and workflow interruptions as unintended consequences of EHR systems. Generally, unintended consequences could have a severe impact on the diagnostic and therapeutic processes undertaken by healthcare professionals at points of care, eventually jeopardising patients’ safety and well-being.13

EHR system has been used in developed countries since its inception in the USA in the 1960s.16 Since then, its impact in enhancing the quality of healthcare has been clear both in the developed and developing world. In developed countries, where EHR systems have undergone an established implementation strategy, there is increased success and health worker satisfaction and decreased delays and chances of usability being compromised.17 However, despite increased use in developed countries, multiple studies conducted in developing countries indicated the adoption of an EHR system is still lagging18; hence, multiple factors play a role in technology adoption and use. A study conducted in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Saudi Arabia indicated that EHR adoption is challenged by inadequate training,19–23 poor infrastructure,19 21–23 lack of technical support,19 21–23 poor communication between users21 and absence of regulations and implementation framework.22 Furthermore, the findings from Jung et al 24 showed that EHR implementation is not an easy task even for countries advancing from developing to developed, let alone developing countries.

EHR implementation or adoption in most low-income countries (LICs) is lagging and affected by multifaceted challenges. Some of these barriers are economy,25 26 infrastructure25 and policy.26 In addition to these, healthcare professionals’ readiness,27 poor collaboration among stakeholders,28 and relying on software provided by non-governmental organizations (NGOs)28 are affecting EHR adoption in LICs. However, due to the development of open-source systems, support from international donors and homegrown software development campaign29; EHR adoption in LICs is becoming feasible and a future direction.

On top of this, there is a research gap in identifying the existing situation of EHR adoption in LICs despite some efforts made in low-middle-income and middle-income countries. Therefore, this review aimed to examine the status, challenges and opportunities of adopting EHR systems to enhance the quality of healthcare delivery in LICs. It is hoped that the review will provide effective support for the local developers, healthcare providers, different stakeholders and funders in the course of developing or adopting EHR systems. We conducted the review based on the following questions:

RQ1: What is the status of HER systems adoption in LICs?

RQ2: What are the challenges influencing the adoption of EHR systems in LICs?

RQ3: What opportunities are facilitating the adoption of EHR systems in LICs?

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 checklist was used to conduct this review.30

Eligibility criteria

We used the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in table 1 to identify articles that meet the study objectives.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | |

| Inclusion | 1. Articles that present the status, challenges and opportunities of EHR adoption in LICs |

| 2. Articles published in English starting from January 2017 to 30 September 2022 | |

| 3. Peer-reviewed journal articles | |

| Exclusion | 1. Articles do not explicitly discuss EHR adoption, its challenges and opportunities in LICs |

| 2. Articles on EHR adoption in countries other than LICs | |

| 3. Books, book chapters, conference papers, symposiums, review articles and non-English scripts |

EHR, electronic health record; LICs, low-income countries.

Information sources and search strategy

PubMed, Science Direct and IEEE Xplore were the electronic databases used for the literature search. We conducted the search using keywords based on four concepts, namely “electronic health record,” “adoption,” “quality of healthcare,” and “developing countries.” Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms were also used to supplement the keyword search in the PubMed database, hence it is a controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles. We conducted forward and backward citation searches on significant search results and manual searches on health informatics journals found in developing countries. We presented the search strategies in table 2.

Table 2.

Information sources and search strategy

| Date of the search | Database | Search query | Filters | Search result |

| 28 September 2022 | PubMed | (("Electronic Health Records"[MeSH Terms] OR "electronic health record*"[Title/Abstract] OR "electronic medical record*"[Title/Abstract] OR "computerized medical record*"[Title/Abstract] OR "EHR"[Title/Abstract] OR "EMR"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("Adoption"[Title/Abstract] OR "application"[Title/Abstract] OR "utilization"[Title/Abstract] OR "acceptance"[Title/Abstract] OR "implementation"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("Quality of Health Care"[MeSH Terms] OR "Health Care Quality"[Title/Abstract] OR "Quality of Healthcare"[Title/Abstract] OR "Healthcare Quality"[Title/Abstract] OR "Quality of Care"[Title/Abstract] OR "Care Quality"[Title/Abstract] OR "pharmacy audit*"[Title/Abstract] OR "Audit Pharmacy"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("Developing Countries"[MeSH Terms] OR "developing countr*"[Title/Abstract] OR "developing nation*"[Title/Abstract] OR "economically developing nation*"[Title/Abstract] OR "economically developing countr*"[Title/Abstract] OR "emergent nation*"[Title/Abstract] OR "least developed countr*"[Title/Abstract] OR "low income countr*"[Title/Abstract] OR "underdeveloped nation*"[Title/Abstract])) AND (2017:2022[pdat]) | Year of publication between 2017 and 2022 | 39 |

| 28 September 2022 | Science Direct | Year: 2017–2022 Title, abstract, keywords: ("electronic health records" OR EMR OR EHR) AND (adoption OR implementation) AND "Quality of healthcare" AND ("developing countries" OR "low-income countries" OR "developing nations") Article type: Research articles |

Year of publication between 2017 and 2022, Research articles | 44 |

| 28 September 2022 | IEEE Xplore | ("All Metadata":"electronic health record*" OR "All Metadata":"electronic medical record*" OR "All Metadata":"computerized medical record*" OR "All Metadata":EHR OR "All Metadata":EMR) AND ("All Metadata":"developing countr*" OR "All Metadata":"low income countr*") You Refined By: Content-Type: Journals, Early Access Articles Year: 2017-2022 |

Journals, early access articles, Year of publication between 2017 and 2022 | 12 |

| 29 September 2022 | Citation search+other journals | "electronic health records" AND "name of LIC" OR "electronic medical records" AND "name of LIC" |

Year of publication between 2017 and 2022, empirical research articles | 14 |

Selection process

We imported the search results from all databases and citation searches into EndNote to begin the selection process. First, we removed duplicate records. After doing so, we screened the remaining records to detect subject relevance with the research objectives considering their title and, or abstract. Next, full-text articles were identified for retrieval. Finally, articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected for qualitative analysis and synthesis. The author (WJ) validated the entire selection process to ensure its accuracy.

Data collection process, data items, analysis and synthesis

The data collection process started by identifying the main concepts in the three research questions that appear as results or findings in each of the reviewed articles. This approach formed a conceptual basis for data extraction under the corresponding heading in a Microsoft Word document. The headings include the authors’ name, publication year, research design, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, study population, sample size and sampling techniques. Moreover, the findings from each of the studies included were extracted as EHR functions, challenges, opportunities and healthcare quality indicators addressed. Content analysis was used to organise related concepts under the categories EHR in LICs, challenges of EHR adoption in LICs, opportunities of EHR in LICs and EHR and healthcare quality in LICs. Finally, narrative synthesis and ordering of the evidence were conducted in each of the four categories by comparing and contrasting with previous studies conducted on the topics.

Risk of bias

Each study included in the review was subject to an appraisal using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists.31 32 Accordingly, we selected and included studies with an optimum score based on the requirements in the checklist. Further, to avoid selection bias, we strictly followed the protocol. In doing so, to some extent, we managed the risk of bias in selection, analysis and reporting.

Results

Study selection

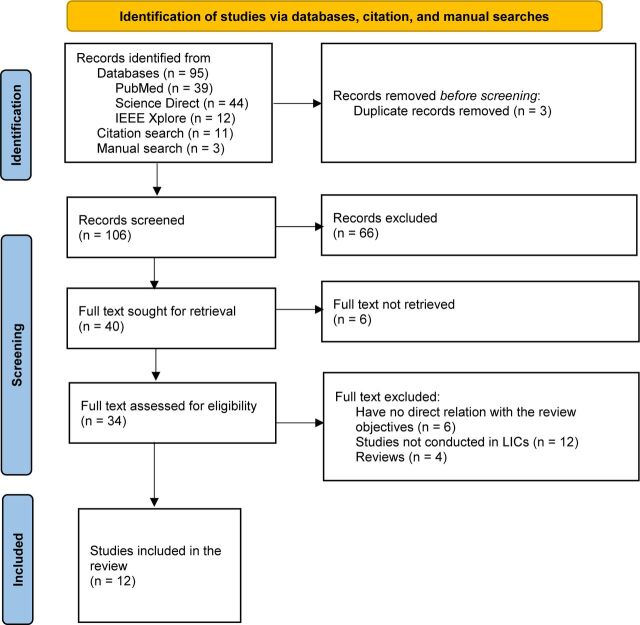

As presented in figure 1, we retrieved 109 records following the search strategy defined. We removed three records that were duplicates. Further, we excluded 66 records after reviewing titles and, or abstracts. Out of 40 studies sought for retrieval, we discarded six as a result of not finding their full text. Out of 34 studies accessed for eligibility, we included 12, which qualified for the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the overall selection process to show studies included and excluded (modified from Page et al 30). LICs, low-income countries; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristics

In this review, we used the world bank classification of 2023 to identify LICs.33 The studies selected systematically from this group were four from Ethiopia, two from Uganda and one from each remaining country: Gabon, Rwanda, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Angola and LICs altogether (Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Mozambique). Based on the type of study; five were quantitative, two were qualitative, three were mixed-type, one was agile software development and one was situational analysis. The details of each study are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Study characteristics

| Author(s) | Country | Article title | Study design/method of data collection | Data analysis technique |

| Bagayoko et al 42 | Gabon | Implementation of a national electronic health information system in Gabon: a survey of healthcare providers’ perceptions | Cross-sectional survey/questionnaire | Logistic regression |

| Bisrat et al 43 | Ethiopia | Implementation challenges and perception of care providers on Electronic Medical Records at St. Paul’s and Ayder Hospitals, Ethiopia | Cross-sectional survey/questionnaire and Interview | Descriptive analysis and thematic analysis |

| Fraser et al 40 | Rwanda | User Perceptions and Use of an Enhanced Electronic Health Record in Rwanda With and Without Clinical Alerts: Cross-sectional Survey | Cross-sectional survey/interviews, observation and free text | Thematic analysis and descriptive analysis |

| Liang et al 39 | Uganda | A Locally Developed Electronic Health Platform in Uganda: Development and Implementation of Stre@mline | Cross-sectional survey/questionnaire | Descriptive analysis |

| Mkalira Msiska et al 44 | Malawi | Factors affecting the utilisation of electronic medical records system in Malawian central hospitals | Cross-sectional survey/questionnaire and Interview | Descriptive analysis and χ2 test |

| Oumer et al 38 | Ethiopia | Utilisation, Determinants and Prospects of Electronic Medical Records in Ethiopia | Cross-sectional survey/questionnaire | Descriptive analysis, bivariate and multivariate logistic regression |

| Oza et al 34 | Sierra Leone | Development and Deployment of the OpenMRS-Ebola Electronic Health Record System for an Ebola Treatment Centre in Sierra Leone | Agile software development/questionnaire | Not mentioned |

| Robbiati et al 35 | Angola | Improving TB Surveillance and Patients' Quality of Care Through Improved Data Collection in Angola: Development of an Electronic Medical Record System in Two Health Facilities of Luanda | Not mentioned/meetings, interviews, site visits and observation | Situational analysis |

| Were et al 41 | Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Mozambique | mUzima Mobile Electronic Health Record (EHR) System: Development and Implementation at Scale | Not mentioned/mHealth evidence reporting assessment checklist | Not mentioned |

| Ahmed et al 37 | Ethiopia | Intention to use electronic medical record and its predictors among healthcare providers at referral hospitals, north-West Ethiopia, 2019: using unified theory of acceptance and use technology 2 (UTAUT2) model | Cross-sectional explanatory/questionnaire and in-depth interview | Structural Equation Model, χ2 test and thematic analysis |

| Kabukye et al 54 | Uganda | User Requirements for an Electronic Medical Records System for Oncology in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Uganda | Qualitative study/FGD and interview | Content and thematic analysis |

| Ngusie et al 36 | Ethiopia | Healthcare providers’ readiness for electronic health record adoption: a cross-sectional study during pre-implementation phase | Cross-sectional/questionnaire | Multivariate logistic regression |

FGD, focus group discussion.

EHR in low-income countries

In this review, 9 of the 12 studies showed some of the major functions of EHR/EMR in LICs. The first one is the OpenMRS-Ebola, which was implemented in Sierra Leone. The system can track patients’ vital signs, medication, intravenous fluid ordering and monitoring, laboratory results, and clinician notes, and export data for clinical decision-making.34 EMR systems are being used to enhance tuberculosis surveillance and control in Angola.35

In Ethiopia, studies were conducted to assess the healthcare providers’ technological and organisational readiness and the level of EHR adoption. The findings indicated that the overall readiness of healthcare providers was inadequate.36 Ahmed et al 37 noted that 39.8% of healthcare providers surveyed showed a score above the mean intention to use EMR in northwest Ethiopia. Whereas, a study by Oumer et al 38 in eastern Ethiopia showed optimal EMR usage level. These findings portray that EHR systems are not adopted as expected to address quality healthcare in the country.

In Uganda, a locally developed EHR platform (Stre@mline) is highly accepted and used despite implementation challenges.39 The system can monitor patients, control stock levels, provide early warning and capture prescription errors. Similarly, Fraser et al 40 noted that OpenMRS in Rwanda supports healthcare delivery by managing patient records, making informed decisions, and providing useful alerts and reminders. Finally, mUzima is a mobile-based EMR system that is providing quality healthcare in countries like Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Mozambique.41

Barriers and facilitators to EHR adoption in LICs

Five studies identified barriers to EHR adoption in LICs, as presented in table 4. Dominantly, lack of training,40 42–44 poor infrastructure,40 43 44 lack of management commitment,40 43 lack of standards40 43 44 and absence of interoperability43 are the barriers observed. Bagayoko et al 42 identified the quality of a system, support, information, actual use, satisfaction and impact as potential barriers. Oza et al 34 showed that inconsistency in EHR systems creates an enormous challenge. In addition to this argument, experience is another barrier to adopting EHR as a health professional over 5 years of experience had two times higher odds of using EMR than early career workers.38 Overall, in most LICs, EHR adoption exists in the preimplementation phase.36

Table 4.

Barriers and facilitators to EHR adoption in LICs

| Work system factors | EHR system adoption in LICs to enhance the quality of healthcare | |

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

| People | Awareness, experience, resistance, lack of training | Providing alerts Perception to use EHR |

| Environmental | Interoperability with other systems, finance, absence of explicit policy, lack of standards, lack of management commitment, quality of a system | Immaturity of health information exchange infrastructure in LICs |

| Tools | Poor infrastructure | |

| Tasks | The partnership among stakeholders to design and adopt EHR systems. | |

| Interaction between people, environments, tools and tasks | Poor integration of the EHR system with people, infrastructure, functions and other existing systems. | |

EHR, electronic health record; LICs, low-income countries.

Four studies identified facilitators to HER adoption in LICs, as presented in table 4. Bisrat et al 43 found 70%–95% of healthcare providers have a favourable perception of using EMR systems. Similarly, Oumer et al 38 identified that about 85% of healthcare professionals demonstrated goodwill in using EMR systems. Fraser et al 40 noted the role of EHR systems in supporting patient care by providing alerts ahead of complications. The immaturity of health information exchange infrastructure in many LICs provides an opportunity to enhance EHR systems by incorporating mobile-based systems.41

Table 4 illustrates people and environment-related factors are both facilitating and impeding EHR adoption in LICs. While tool-related factors influence, task-related factors are facilitating EHR adoption. Overall, poor integration of EHR among the work systems factors affects EHR adoption. The absence of facilitators under tools and interaction among the four work systems indicated an insufficiency of technology and lack of management support to facilitate EHR adoption, respectively.

EHR and healthcare quality in LICs

EHR systems are improving healthcare delivery in both developing and developed countries. An empirical work reported from Rwanda,40 Uganda39 and Malawi44 showed that EHR systems improve healthcare by managing patient information, supporting informed decisions and providing useful alerts. In developed nations, EHR-based clinical trials are providing evidence about treatment strategies, patient safety, care and health policy decisions.45 Based on the WHO definition, this review considered seven quality indicators of healthcare: Safety, effectiveness, people-centredness, timeliness, efficiency, equity and integrated service.1

Safety

In terms of safety, the finding presented by Fraser et al 40 signified the role of openMRS system in supporting patient care by providing alerts. Additionally, Liang et al 39 mentioned the significance of EHR systems in maintaining patient safety features, which in turn has improved care for more than 60 000 patients in Uganda. This indicates implementation of an EHR system is highly important to ensure patient safety.

Effectiveness

In this review, Mkalira Msiska et al 44 noted EMR systems help generate more accurate information that can reduce medical errors. This could improve the decision-making capability of healthcare workers for effective patient management. Liang et al 39 mentioned that the locally developed EHR platform is capable of managing patient information and related healthcare services. Further, Fraser et al 40 indicated the effectiveness of openMRS despite the infrastructure limitation in Rwanda. These all assertions prove the significance of adopting EHR systems in delivering effective healthcare services.

People-centredness

In this review, the findings of Liang et al 39 reported that the partnership between healthcare providers and developers is significant to the design and adoption of user-centred technologies. The mUzima (mobile health) application is an example of how technologies can be used to promote healthcare for people at large.41 The finding also indicated the adoption of mUzima across multiple LICs and for numerous core healthcare domains. These findings depict, EHR systems that are well communicated with the users during the design and adoption phases would yield a better outcome.

Timeliness

The review identified the benefits of EHR systems in facilitating contacting patients to ensure good ongoing care in place.39 Mkalira Msiska et al 44 finding affirmed the introduction of EMR systems in Malawi healthcare helped to assess patients within a short period. Similarly, a survey by Oumer et al 38 found that 75% of health professionals agreed EMRs can improve timely patient care. These findings affirm the significance of EHR systems in providing timely care for patients in LICs.

Efficiency

The findings from Liang et al 39 indicated that EHR platforms play a crucial role in improving clinical efficiency. This could help healthcare professionals to carry out their duty on time and help patients not to wait too long to get treatments. Further, Mkalira Msiska et al 44 noted that the EMR system is more efficient in assessing more patients in a short period than traditional systems. Thus, adopting EHR systems can help improve healthcare quality by providing efficient services.

Equity

In this review, Were et al 41 stressed the use of the EHR system in delivering healthcare services by avoiding geographical barriers. The study identified that such systems could extend the reach of EHR systems within resource-limited settings as opposed to siloed mhealth applications. Further, Mkalira Msiska et al 44 underlined the significance of EHR systems in reaching every patient awaiting healthcare services with no bias. EHR systems provide healthcare services without geographical, economical and social limitations.

Integrated

In this review, the findings of Oza et al 34 showed that OpenMRS is the most comprehensive, adaptable clinical EHR built for a low-resource setting. The system is interoperable with other EHR systems to provide integrated healthcare services. Liang et al 39 noted that EHR platforms are being used to support patient care, live control of stock medicines, forward warnings to pharmacists and recognise prescription errors before causing harm. These findings elucidate the role of EHR systems in providing integrated quality healthcare services for patients.

Discussion

Status of EHR adoption, challenges and opportunities in LICs

This review aims to examine the status, challenges and opportunities of adopting EHR systems to enhance the quality of healthcare delivery in LICs. In most LICs, donors provide support to establish EHR systems, which usually fail for many reasons. For example, in Ethiopia, the Smart Care system, which is supported by donors, is not functioning at full scale as expected due to low economic readiness.46 It is failing at a pilot stage in many of the hospitals where the system is implemented.43 Further, Ngusie et al 36 noted that, in most LICs, EHR implementation exists at the preimplementation stage. This affirms that countries should first identify organisational, technological, social and economic readiness before adopting EHR systems.46

However, in countries such as Uganda, locally developed EHR platforms are being used to enhance patient care.39 The openMRS system in Rwanda is also making a notable influence in supporting healthcare delivery by providing informed decisions, alerts and reminders.40 Further, studies conducted in Sierra Leone and Angola indicated that open-source EMR systems are enhancing clinical care and clinical decision-making.34 35 These findings show that EHR systems are currently being practised in LICs despite the challenges reported. It is also in line with the findings reported in low-income and-middle-income countries.47 Therefore, LICs should work hard towards adopting open-source EMR systems which fit the shortcomings of the economy and user-friendliness.

Most of the challenges for the failure of EHR adoption in LICs were lack of training, infrastructure, management commitment, standards, consistency, interoperability, quality of systems, support, use, information, satisfaction and impact of the system.34 40 42–44 Further, Oumer et al 38 added the impact of healthcare providers’ experience on affecting EHR adoption as experienced have twice higher odds of using EMR than early career workers. Most of these challenges are similar to those reported in studies conducted in middle-income countries.19–23 Furthermore, a scoping review of studies published between 2005 and 2020 on PubMed, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore and ACM Digital Library reported similar challenges as the current study.48 Therefore, every LICs needs to develop strategies, legislations, regulations and a framework of implementation that can address the mentioned challenges before adopting or implementing EHR systems.

Moreover, EHR adoption might pose unanticipated challenges to existing healthcare systems if not managed appropriately. Windle et al 49 in their findings indicated the perception of clinicians on the impact of EHR in impeding the workflow and communication, and prolonging their workday. EHR implementation causes physician burn-out due to contributing factors like increased documentation, which are significantly underestimated.50 These challenges need critical attention and should be addressed during the preimplementation phase.

Despite the various factors influencing the success of EHR adoption, there are opportunities that can maximise its potential. The most important scenario is a good perception of healthcare providers in using EMR systems.43 Also, most healthcare professionals are open-minded about using such systems whenever deployed or adopted.38 Moreover, the health information exchange infrastructure in LICs is immature or absent. These findings are in line with those mentioned in the studies conducted by Amend et al 51 which considers stakeholder readiness, change management, accessibility and ownership, EHR structure and external factors as key facilitators for EHR adoption.

Multiple studies indicated the impact of EHR systems in capitalising on quality in healthcare delivery.34 38–41 44 Studies conducted in countries other than LICs indicated the significance of EHR systems in enhancing the quality of healthcare in terms of safety, effectiveness, people-centredness, timeliness, efficiency, equity and provision of integrated services.52 53 This study portrayed a clear image of EHR systems adoption status, challenges and opportunities in LICs to enhance the quality of healthcare delivery.

Conclusion

EHR adoption is at early stage in most LICs, with different types of EHRs being used. It is facilitated or influenced by people, environment, tools, tasks and the interaction among these four factors. Unanticipated challenges such as physician burn-out are creating a challenge in slowing down EHR adoption.

Strengths

The review followed a protocol to select and synthesise relevant studies on the topic. Further, it identified research gaps to be addressed by future researchers. Overall, because of absence of previous systematic reviews in LICs, the findings could help develop implementation strategies and policies.

Limitations

The search result was vulnerable to various problems, such as reporting bias or lack of enough research outputs from LICs, as only studies from eight countries out of 28 were included. Additionally, a literature search was conducted only on PubMed, Science Direct, IEEE Xplore and journals of health informatics in developing countries. However, the quality of the studies was not compromised by following the review protocol.

Implications for practice, policy and future research

The review findings suggest all actors involved in EHR systems should collaborate effectively to yield a better outcome in healthcare delivery. This can be supported through EHR adoption policies, which are currently missing in many countries. Future research should focus on comparative studies on the practice of EHR systems in developing and developed countries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jimma University, Institute of Technology for arranging the schedule and essential resources altogether to complete this work.

Footnotes

@Misganaw2012

Contributors: In this systematic review, MTW contributed to the conception, design, database searching, full-text screening and write-up of the manuscript. WJ contributed by evaluating and assuring the quality of the review’s study selection, analysis, synthesis and edition of the manuscript. The final draft of the manuscript was read, edited, and approved for publication by MTW and WJ .

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. WHO . Fact sheet: quality health services. World Health Organization; 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/quality-health-services [Accessed 6 Oct 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chakraborty S, Bhatt V, Chakravorty T. Impact of Digital technology adoption on care service orchestration, agility, and responsiveness. Int J Sci Technol Res (New Delhi) 2020;9:4581–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauer AM, Thielke SM, Katon W, et al. Aligning health information Technologies with effective service delivery models to improve chronic disease care. Prev Med 2014;66:167–72. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kutney-Lee A, Sloane DM, Bowles KH, et al. Electronic health record adoption and nurse reports of usability and quality of care: the role of work environment. Appl Clin Inform 2019;10:129–39. 10.1055/s-0039-1678551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aldosari B. Patients' safety in the era of EMR/EHR automation. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2017;9:230–3. 10.1016/j.imu.2017.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muhaise H, Kareyo DM, Muwanga-Zake P. Factors influencing the adoption of electronic health record systems in developing countries: A case of Uganda. ASRJETS 2019;61:160–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gatiti P, Ndirangu E, Mwangi J, et al. Enhancing Healthcare quality in hospitals through electronic health records: A systematic review. J Health Inform Dev Ctries 2021;15. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colicchio TK, Cimino JJ, Del Fiol G. Unintended consequences of nationwide electronic health record adoption: challenges and opportunities in the post-meaningful use era. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13313. 10.2196/13313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA. Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: are we ignoring the real cause. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:50–1. 10.7326/M18-0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tajirian T, Stergiopoulos V, Strudwick G, et al. The influence of electronic health record use on physician burnout: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19274. 10.2196/19274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alami H, Lehoux P, Gagnon M-P, et al. Rethinking the electronic health record through the quadruple aim: time to align its value with the health system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:32. 10.1186/s12911-020-1048-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shah SM, Khan RA. Secondary use of electronic health record: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access 2020;8:136947–65. 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3011099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogundaini O, de la Harpe R, McLean N. Unintended consequences of technology-enabled work activities experienced by Healthcare professionals in tertiary hospitals of sub-Saharan Africa. AJSTID 2022;14:876–85. 10.1080/20421338.2021.1899556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeWane M, Waldman R, Waldman S. Cell phone etiquette in the clinical arena: A professionalism imperative for Healthcare. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2019;49:79–83. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gagnon M-P, Ngangue P, Payne-Gagnon J, et al. M-health adoption by Healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:212–20. 10.1093/jamia/ocv052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Net Health . The history of electronic health records (Ehrs) - updated. 2022. Available: https://www.nethealth.com/the-history-of-electronic-health-records-ehrs/

- 17. Aguirre RR, Suarez O, Fuentes M, et al. Electronic health record implementation: A review of resources and tools. Cureus 2019;11:e5649. 10.7759/cureus.5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parks R, Wigand RT, Othmani MB, et al. Electronic health records implementation in Morocco: challenges of silo efforts and recommendations for improvements. Int J Med Inform 2019;129:430–7. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adedeji P, Irinoye O, Ikono R, et al. Factors influencing the use of electronic health records among nurses in a teaching hospital in Nigeria. J Health Inform Dev Ctries 2018;12. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alboliteeh M. A cross-sectional study of nurses’ perception toward utilization and barriers of electronic health record. MJHR 2022;26. 10.7454/msk.v26i3.1369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Essuman LR, Apaak D, Ansah EW, et al. Factors associated with the utilization of electronic medical records in the Eastern region of Ghana. Health Policy and Technology 2020;9:362–7. 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katurura MC, Cilliers L. Electronic health record system in the public health care sector of South Africa: A systematic literature review. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2018;10:e1–8. 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Muinga N, Magare S, Monda J, et al. Digital health systems in Kenyan public hospitals: a mixed-methods survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:2. 10.1186/s12911-019-1005-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jung SY, Lee K, Lee H-Y, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to implementation of nationwide electronic health records in the Russian far East: A qualitative analysis. Int J Med Inform 2020;143:104244. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Irshad R, Ghafoor N. Infrastructure and economic growth: evidence from lower middle-income countries. J Knowl Econ 2023;14:161–79. 10.1007/s13132-021-00855-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steinbach R. growth in low-income countries: evolution, prospects, and Policies . July 2019. 10.1596/1813-9450-8949 [DOI]

- 27. Awol SM, Birhanu AY, Mekonnen ZA, et al. Health professionals' readiness and its associated factors to implement electronic medical record system in four selected primary hospitals in Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract 2020;11:147–54. 10.2147/AMEP.S233368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tolera A, Oljira L, Dingeta T, et al. Electronic medical record use and associated factors among Healthcare professionals at public health facilities in dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia: A mixed-method study. Front Digit Health 2022;4:935945. 10.3389/fdgth.2022.935945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colicchio TK, Cimino JJ. Twilighted Homegrown systems: the experience of six traditional electronic health record developers in the post–meaningful use era. Appl Clin Inform 2020;11:356–65. 10.1055/s-0040-1710310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:179–87. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk in. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI. 2020. 10.46658/JBIRM-190-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Bank . Countries classified as low-income countries (2023 World Bank). 2023. Available: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/low-income-countries

- 34. Oza S, Jazayeri D, Teich JM, et al. Development and deployment of the Openmrs-Ebola electronic health record system for an Ebola treatment center in Sierra Leone. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e294. 10.2196/jmir.7881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robbiati C, Tosti ME, Mezzabotta G, et al. Improving TB surveillance and patients' quality of care through improved data collection in Angola: development of an electronic medical record system in two health facilities of Luanda. Front Public Health 2022;10:745928. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.745928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ngusie HS, Kassie SY, Chereka AA, et al. Healthcare providers' readiness for electronic health record adoption: a cross-sectional study during pre-implementation phase. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:282. 10.1186/s12913-022-07688-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahmed MH, Bogale AD, Tilahun B, et al. Intention to use electronic medical record and its predictors among health care providers at referral hospitals, North-West Ethiopia, 2019: using unified theory of acceptance and use technology 2(Utaut2) model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:207. 10.1186/s12911-020-01222-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oumer A, Muhye A, Dagne I, et al. Utilization, determinants, and prospects of electronic medical records in Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int 2021;2021:2230618. 10.1155/2021/2230618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang L, Wiens MO, Lubega P, et al. A locally developed electronic health platform in Uganda: development and implementation of Stre@Mline. JMIR Form Res 2018;2:e20. 10.2196/formative.9658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fraser HSF, Mugisha M, Remera E, et al. User perceptions and use of an enhanced electronic health record in Rwanda with and without clinical alerts: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Med Inform 2022;10:e32305. 10.2196/32305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Were MC, Savai S, Mokaya B, et al. mUzima mobile electronic health record (EHR) system: development and implementation at scale. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e26381. 10.2196/26381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bagayoko CO, Tchuente J, Traoré D, et al. Implementation of a national electronic health information system in Gabon: a survey of Healthcare providers’ perceptions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:202. 10.1186/s12911-020-01213-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bisrat A, Minda D, Assamnew B, et al. Implementation challenges and perception of care providers on electronic medical records at St. Paul’s and Ayder hospitals, Ethiopia. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021;21:306. 10.1186/s12911-021-01670-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mkalira Msiska KE, Kumitawa A, Kumwenda B. Factors affecting the utilisation of electronic medical records system in Malawian central hospitals. Malawi Med J 2017;29:247–53. 10.4314/mmj.v29i3.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abdel-Kader K, Jhamb M. EHR-based clinical trials: the next generation of evidence EHR-based clinical trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:1050–2. 10.2215/CJN.11860919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fanta GB, Pretorius L, Erasmus L. Hospitals' readiness to implement sustainable Smartcare systems in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2019 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET); Portland, OR, USA. 10.23919/PICMET.2019.8893824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kabukye JK, de Keizer N, Cornet R. Assessment of organizational readiness to implement an electronic health record system in a low-resource settings cancer hospital: A cross-sectional survey. PLOS ONE 2020;15:e0234711. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsai CH, Eghdam A, Davoody N, et al. Effects of electronic health record implementation and barriers to adoption and use: A. Life 2020;10:327. 10.3390/life10120327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Windle JR, Windle TA, Shamavu KY, et al. Roadmap to a more useful and usable electronic health record. Cardiovascular Digital Health Journal 2021;2:301–11. 10.1016/j.cvdhj.2021.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Starren JB, Tierney WM, Williams MS, et al. A retrospective look at the predictions and recommendations from the 2009 AMIA policy meeting: did we see EHR-related clinician burnout coming J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021;28:948–54. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Amend J, Eymann T, Kauffmann AL, et al. Deriving Facilitators for electronic health record implementation: A systematic literature review of opportunities and challenges. ECIS 2022 Research Papers2022;

- 52. Acholonu RG, Raphael JL. The influence of the electronic health record on achieving equity and eliminating health disparities for children. Pediatr Ann 2022;51:e112–7. 10.3928/19382359-20220215-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parzen-Johnson S, Kronforst KD, Shah RM, et al. Use of the electronic health record to optimize antimicrobial Prescribing. Clin Ther 2021;43:1681–8. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kabukye JK, Koch S, Cornet R, et al. User requirements for an electronic medical records system for oncology in developing countries: A case study of Uganda. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2017;2017:1004–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.