Abstract

T cells are crucial for immune functions to maintain health and prevent disease. T cell development occurs in a stepwise process in the thymus and mainly generates CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets. Upon antigen stimulation, naïve T cells differentiate into CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic effector and memory cells, mediating direct killing, diverse immune regulatory function, and long-term protection. In response to acute and chronic infections and tumors, T cells adopt distinct differentiation trajectories and develop into a range of heterogeneous populations with various phenotype, differentiation potential, and functionality under precise and elaborate regulations of transcriptional and epigenetic programs. Abnormal T-cell immunity can initiate and promote the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of T cell development, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell classification, and differentiation in physiological settings. We further elaborate the heterogeneity, differentiation, functionality, and regulation network of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in infectious disease, chronic infection and tumor, and autoimmune disease, highlighting the exhausted CD8+ T cell differentiation trajectory, CD4+ T cell helper function, T cell contributions to immunotherapy and autoimmune pathogenesis. We also discuss the development and function of γδ T cells in tissue surveillance, infection, and tumor immunity. Finally, we summarized current T-cell-based immunotherapies in both cancer and autoimmune diseases, with an emphasis on their clinical applications. A better understanding of T cell immunity provides insight into developing novel prophylactic and therapeutic strategies in human diseases.

Subject terms: Adaptive immunity, Tumour immunology, Infectious diseases, Immunological disorders

Introduction

T lymphocytes (T cells) are the major cell components of the adaptive immune system, responsible for mediating cell-based immune responses to keep the host healthy and prevent various types of diseases. T cells are developed from bone marrow (BM)-derived thymocyte progenitors in the thymus, and broadly grouped into CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells in addition to rear populations of γδ T cells and natural killer T (NKT) cells. αβ T cells recognize antigens that are presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Upon recognition of cognate antigens (signals 1) by T cell receptor (TCR) and costimulatory molecules (signals 2) on APCs, and cytokines (signals 3), naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells undergo activation, clonal expansion, and differentiation to execute their effector functions of killing infected cells, producing cytokines and regulating immune responses. A small population of T cells develops into memory T cells which exhibit rapid effector functions upon reencountering the same antigens and provide the host with potent and long-term protection. In parallel, there exists a subpopulation of CD4+ T cells, named regulatory T (Treg) cells, that maintain peripheral immune tolerance. Over the past few decades, our knowledge of T cells regarding their classification, differentiation, cellular and molecular regulatory mechanisms, particularly phenotypes and functions in healthy conditions and immune-related diseases, has expanded significantly. Hence, novel strategies engaging T cell functions have been extensively developed and demonstrated unprecedented clinical efficacy in the past few decades.

In this review, we comprehensively summarize the current understandings of T cell biology and functions in both physiological and pathological settings, including the following points: (1) describe the T cell development regarding their differentiation process, T cell lineage commitment, β-selection, and CD4/CD8 lineage choice; (2) introduce major CD4+ and CD8+ T cell classification, differentiation, and the underlying regulatory mechanisms; (3) further discuss how CD8+ and CD4+ T cells respond, differentiate and contribute in infectious diseases, chronic infections and tumors, and autoimmune diseases; (4) γδ T cell development, effector subsets and function in tissue surveillance, infection, and tumor immunity; (5) T cell-based immunotherapies in cancer and autoimmune diseases and their clinical applications. Specifically, we highlight the cell signature, differentiation trajectory, regulatory mechanisms, and contributions to anti-tumor immunity of exhausted CD8+ T cells, as well as the roles of CD4+ T cells in helping CD8+ T cell responses.

T cell development

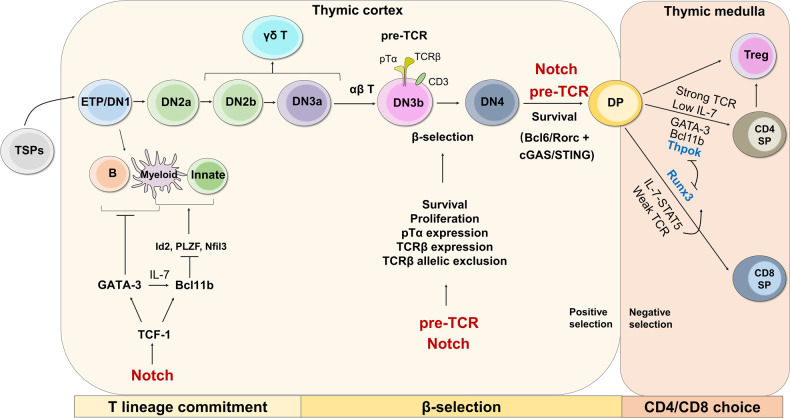

T cell development begins with BM-derived thymic seeding progenitors (TSPs) in the thymus, where T cells undergo a series of developmental stages including double negative (CD4−CD8−, DN), double positive (CD4+CD8+, DP), and single positive (CD4−CD8+ or CD4+CD8−, SP)1–3 (Fig. 1). DN thymocytes can be divided into four distinct stages from DN1 to DN4 based on CD44 and CD25 expression among lineage negative population.2,4–6 Upon Notch signaling, ETPs (DN1) acquire CD25 expression and progress into the DN2a stage, which launches the T cell lineage commitment.4,5 Bifurcation of αβ and γδ T cell lineage occurs at DN2b and DN3a stage along with upregulation of genes associated with TCRγ, TCRδ, and TCRβ rearrangement.7 A functional pre-TCR complex, consisting of CD3 protein, TCRβ and invariant pre-TCRα (pTα), drives DN3 cells to DN4, CD4+CD8− immature single positive (ISP), and DP cell development.7 Those expressing a TCRβ chain can initiate TCRα rearrangement and then form a fully functional αβTCR on the surface, which recognizes MHC I- or MHC II-peptide complexes presented by thymic APCs to become either CD8+ SP or CD4+ SP thymocytes.8 On one hand, the interaction of peptide-MHC with moderate affinity rescues DP thymocytes from apoptosis (known as positive selection) in the thymic cortex and progresses into the SP stage.8 On the other hand, recognition of self-peptide triggers immense death (known as negative selection) or skews CD4+ T cells towards Treg cells in the thymic medulla.9 The following three steps and relevant signals are required for T cell fate decision and development.

Fig. 1.

Overview of thymocyte development and regulatory mechanism. T cell development experiences three key steps: T cell lineage commitment, β-selection, and CD4/CD8 lineage choice, where T cells undergo sequential developmental stages from TSPs to DN, DP, and SP. ETPs (DN1) possess the potential to differentiate into B cells, myeloid cells, and innate-type of T cells, while DN3 can differentiate into γδ T cells. Induced by Notch signaling, transcription factors TCF-1, GATA-3, and Bcl11b play critical roles in promoting T cell lineage commitment by limiting other lineage differentiation. A pre-TCR complex consisting of TCRβ, pTα, and CD3 molecules on DN3 enforces β-selection and DN3 to DN4 development. Both pre-TCR and Notch signaling play critical roles in driving β-selection and DN to DP transition. Following positive and negative selection in the thymic cortex and medulla, respectively, DP cells differentiate into either CD4+ SP under the regulation of strong TCR and Thpok or CD8+ SP under the regulation of weak TCR and Runx3

Orchestrated trajectory for T cell lineage commitment

ETPs still possess the potential to differentiate into other immune cell lineages, such as B cells, NK cells, dendritic and myeloid cells.10,11 How ETPs commit to T cell lineage and lose the ability to convert to alternative lineages? It is well-appreciated that Notch signaling is essential for the initial commitment of T cell lineage in the thymus.12,13 Notch1 signaling induces the expression of transcription factor (TF) T cell factor 1 (TCF-1, encoded by Tcf7), which is required for the generation, survival, and proliferation of ETPs.14–16 TCF-1 promotes the upregulation of T cell-specific TFs GATA-3 and Bcl11b,15,16 and GATA-3 as well as IL-7/IL-7R signal are required for Bcl11b activation.17–19 GATA-3 suppresses both B cell and myeloid cell differentiation in TCF-1-deficient ETPs,15 whereas Bcl11b restricts the progenitor differentiation into innate lymphoid and myeloid lineages.20–22 Mechanistically, Bcl11b blocks expression of Id2, PLZF, and Nfil3 expression,21,23,24 in which Id2-repressed E protein E2A is critical for innate lymphoid cells including NK cell development,25–27 while PLZF and Nfil3 promote innate-type T cell development.28–30 Hence, enforced expression of Bcl11b can restore the DN1 to DN2 transition block resulted from TCF-1 deficiency.15 Future research needs to clarify whether GATA-3 facilitates T cell lineage and limits other lineages independent of Bcl11b. Taken together, following T cell lineage specification, the committed DN2b cells completely step on the T cell development journey.31

DN-DP transition driven by β-selection

Following the accomplishment of TCRβ rearrangement, DN3 cells expressing pre-TCR assembled with the TCRβ chain together with pTα and CD3 molecules (known as β-selection) differentiate into αβ T cells, otherwise, skew into γδ T cells.7,32,33 To date, two major signals are involved in the β-selection process: pre-TCR and Notch signaling. The pre-TCR signaling prevents thymocytes from apoptosis, stimulates their proliferation, induces allelic exclusion at the TCRβ locus in DN3b cells post-β-selection and promotes DN to DP transition.34–37 However, pre-TCR signaling alone is not sufficient for thymocyte development, as isolated DN3 thymocytes fail to differentiate into DP cells in the absence of a stromal cell-derived Notch signal.38–40 Notch signaling has been shown to promote T lineage commitment,41 thymocyte survival,42 DN to DP stage transition,42 and expression of pre-TCR components.43,44 Recently, Notch-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) mediates proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins, which becomes a prerequisite for thymocyte β-selection.45 Pre-TCR and Notch signaling, by targeting ubiquitin ligase subunits Fbxl1 and Fbxl12, respectively, promote the cell cycle progression of β-selected thymocytes via accelerating degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Cdkn1b.46 Furthermore, β-selected thymocytes form an immunological synapse to promote proliferation, which relies on the cooperation between Notch and pre-TCR signaling.47 Interestingly, pre-TCR independent mechanisms also regulate thymocyte development. Recent studies from our and other groups demonstrated that zinc finger protein Zfp335 controlled thymocyte survival and DN to DP transition by inducing Bcl-6/Rorc expression or cGAS/STING suppression in a pre-TCR independent manner.48,49

Choice to become CD4+ or CD8+ T cells

Following positive selection, DP cells bearing MHC class I- or MHC class II-TCRs differentiate into either CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, termed as CD4/CD8 lineage choice.50,51 A well-known theory holds that DP thymocytes received positive selection signals initially terminate CD8 gene transcription and become CD4+CD8lo intermediate cells which further progress into CD4+ or CD8+ T cells depending on TCR signaling or cytokines stimulation.52–54 Persistent and strong TCR signals in intermediate thymocytes trigger differentiation into CD4+CD8- SP cells largely by inhibiting IL-7-mediated signaling, whereas transient and weak TCR signals force these cells into CD4-CD8+ SP cells, which relies on signals from IL-7 and other common gamma chain (γc) cytokines.55–57

Thpok and Runx3 are two antagonistic TFs controlling the lineage choice between CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Thpok is highly expressed in CD4+ but not CD8+ thymocytes, and serves as a master regulator for CD4 lineage commitment.58,59 Mice with Thpok depletion or a missense mutation lack CD4+ T cells,58,60–63 whereas ectopic expression of Thpok strongly drives DP thymocytes into CD4+ SP cells.58,59 Mechanistically, Thpok represses Runx3 and CD8 lineage-related genes.61,64,65 In contrast, Runx3 facilitates CD8+ T cell development by directly downregulating CD4 and Thpok expression.62,66 In addition, Bcl11b promotes CD4 lineage commitment by directly targeting to several Thpok locus67,68 and Runx3 promoter region.67 TCR signaling-induced GATA-3 is also required for CD4 lineage commitment by enhancing Thpok expression,69,70 while the IL-7-STAT5 axis acts upstream of Runx3 to enhance its expression and promote CD8+ T cell development.71 Therefore, the balance between Thpok and Runx3 decides the lineage choice of CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells.

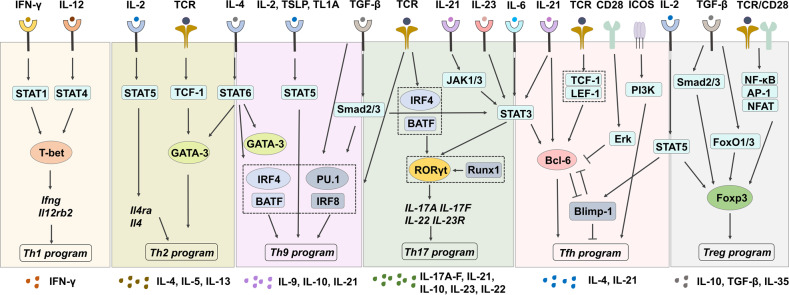

CD4+ T cell classification and differentaiton

CD4+ T helper (Th) cells are a heterogeneous group of T cells playing central roles in almost all aspects of immune responses. CD4+ T cells can be activated by peptide-MHC class II complex on APCs, costimulatory stimulation, and cytokine signaling72–74 and differentiate into several subsets with a distinct expression of surface molecules, cytokines, and key TFs,75,76 such as Th1, Th2, Treg, follicular helper T (Tfh), Th17, Th9, Th22, and CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), etc.77 Here, we will introduce six major Th subsets and the regulatory pathways of their differentiation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine signalings regulate CD4+ Th cell differentiation. Upon TCR stimulation, naïve CD4+ T cells can be differentiated into distinct effector Th subsets under different cytokines and costimulatory stimulation. IFN-γ and IL-12 drive Th1 cell differentiation by inducing the master TF T-bet expression through STAT1 and STAT4, respectively. Th2 cells are induced by TCR-stimulated TCF-1 activation and cytokine IL-2 and IL-4 signaling, expressing key TF GATA-3. Th9 cells are induced under TCR stimulation in the presence of IL-4 and TGF-β, and enhanced development by STAT5 activation. While IL-6 and TGF-β drive Th17 cell differentiation, IL-21 and IL-23 stabilize Th17 lineage by inducing RORγt. Cytokines IL-6 and IL-21 promote, while IL-2 inhibits Tfh cell differentiation. Costimulatory signaling from CD28 and ICOS play opposite roles in Tfh cell development. Treg cells can be differentiated upon TCR/CD28 stimulation in the presence of TGF-β and IL-2 through inducing Foxp3 expression. Shared cytokines are illustrated between cells: IL-4 for Th2 and Th9, TGF-β for Th9 and Th17, IL-6 for Th17 and Tfh, and IL-2 for Tfh and Treg cells. The same cytokines may induce different downstream signaling cascade and differentiation fate. For instance, IL-6-induced STAT3 activation leads to the expression of RORγt in Th17 cells but Bcl-6 in Tfh cells. Signaling complexes formed are indicated in the dashed squares

Th1 cells are the major participants in protecting hosts against intracellular bacteria and viruses by producing the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ. IL-12 and IFN-γ are two cytokines essential for Th1 differentiation.78 TCR stimulation and IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling induce the expression of T-bet (encoded by Tbx21), the major TF driving Th1 differentiation while suppressing Th2/Th17 lineages.79,80 T-bet can directly bind to the Ifng gene to increase the expression of IFN-γ80,81 and meanwhile promote the expression of IL-12Rβ2, conferring IL-12 responsiveness.82 IL-12 signaling via STAT4 activation, in turn, maintains T-bet expression.83 These feedback loops all contribute to Th1 differentiation.

Th2 cells, defined by expression of TF GATA-3 and cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, protect the host against helminth infections, facilitate tissue repair, as well as contribute to chronic inflammation such as asthma and allergy.84 IL-4 secreted by dendritic cells (DCs) and innate lymphoid cell group 2 (ILC2) binds to IL-4R on CD4+ T cells, leading to the expression of GATA-3 through STAT6 phosphorylation and subsequent production of Th2-related cytokines.85 Autocrine production of IL-4 by activated CD4+ T cells further promotes Th2 differentiation.86 In addtion, GATA-3 mediates the repression of Th1 cell development by sliencing Th1-related genes such as Tbx21, Ifng, Stat4, and Il12rb2.87 STAT5 signaling primed by IL-2 is required for maintaining the expression of Il4ra and increasing the accessibility of Il4 chromatin.87,88 Other TFs such as NFAT1, c-Maf, IRF4, and JunB can promote Th2 program by inducing IL-4 production.87 In addition, TCF-1, activated by TCR stimulation, has been found to initiate Th2 cell differentiation by promoting GATA-3 expression.89

Th9 cells are a newly identified subset of CD4+ T cells, playing critical roles in infectious diseases, allergy, cancer, and autoimmune immunity.90–94 Th9 cells can be induced in vitro by TCR stimulation in the presence of IL-4 and TGF-β, and are characterized by expressing high levels of IL-9 and prominent TFs IRF4 and PU.1.90,95–97 Besides IL-9, IL-10, and IL-21 are also produced by Th9 cells.98 STAT6 phosphorylation mediated by IL-4 signaling induces expression of GATA-3, IRF4 and BATF to promote IL-9 transcription and Th9 cell development.99,100 Besides, TGF-β signaling activates Smads (Smad2/3), PU.1 and IRF8, contributing to Th9 cell differentiation.99,100 Furthermore, IRF4, PU.1, IRF8, and BATF form a TF complex which binds to Il9 locus and regulate Th9 differentiation.101 In addition, STAT5 phosphorylation induced by IL-2, TSLP, and TL1A promotes Th9 cell development.99 The differentiation of Th9 cells is also regulated by costimulation signaling (CD28, OX40, GITR, Notch, and DR3) and other cytokines (IL-1, IL-25, IL-7, and IL-21).91,99,100

Th17 cells, characterized by expression of featured cytokines IL-17A-F, IL-21, IL-10, IL-23, and IL-22, and steroid receptor–type nuclear receptor RORγt as the master TF,102 contribute to protection against extracellular pathogens, especially at mucosal tissue,103 as well as chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases.104 IL-6 and TGF-β drive Th17 cell differentiation while IL-21 and IL-23 stabilize Th17 lineage.105–109 IL-6 prompts the expression of RORγt by phosphorylation of STAT3, while inhibits the expression of Foxp3 induced by TGF-β.110 RORγt induces the expression of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, and IL-23R by directly targeting to their promoters.111 TGF-β signaling through Smad2/3 could sustain STAT3 activation.112 Autocrine IL-21 activates STAT3 through Janus kinase (JAK)1/3 activation, which can further increase the expression of IL-23R and confer IL-23 responsiveness of Th17 cells.113 IL-23 then enhances STAT3 activation to stabilize Th17 development.114 Recent studies have revealed a great degree of plasticity of Th17 cells depending on the presence of TGF-β. TGF-β and IL-6 induce the “classical” Th17 cells characterized by the production of IL-17, IL-21, and IL-10, whereas IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23 induce “pathogenic” Th17 cells producing high levels of IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and IL-22.115–117 Besides RORγt, TCR signal induced transcriptional complex formed by IRF4 and BATF contributes to the initial chromatin accessibility of Th17-related genes such as Il17, Il21, Il23r, and RORc, as well as Foxp3 suppression.118–120 Runx1 enhances Th17 development through both inducing and directly interacting with RORγt.121,122 Other TFs, including RORα, c-Maf, p65, NFAT, and c-Rel, also participate in Th17 differentiation.123–127

Tfh cells are specialized CD4+ Th cells involved in supporting humoral immune responses by promoting B cell proliferation and maturation, germinal center (GC) response, and high-affinity antibody production.80,128,129 Tfh cells are featured by high expression of surface markers PD-1 and CXCR5, costimulatory receptors CD40, CD40LG, and ICOS, cytokines IL-4 and IL-21, signaling molecules SAP, as well as TF STAT3 and Bcl-6.128 Tfh cells play central roles in regulating antibody responses during infectious diseases, allergy, autoimmune diseases, and vaccination.130–132 Tfh cell development is mainly regulated by the master TF Bcl-6133 which primarily represses alternative, non-Tfh, cell fates.134–136 Bcl-6 constrains Th1, Th2 and Th17 cell differentiation by repressing their lineage-defining TFs T-bet, GATA-3, and RORγt expression.133,137,138 Suppression of B lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1, encoded by Prdm1) by Bcl-6 is also required for Tfh lineage.139 TCF-1 is involved in early induction of Bcl-6 by orchestrating with LEF-1.140,141 Other TFs, such as BATF, STAT1/3/4/5, Foxp1, KLF2, IRF4, Ets1, BACH2, Ascl2, Tox2, and Bhlhe40, have been also identified in regulating Tfh cell development.136,142–144 Additionally, Tfh cell development is regulated by costimulatory signaling in which CD28 stimulation activates ERK to suppress Tfh cell differentiation,145 whereas ICOS activates PI3K to promote and maintain Tfh cells.146 In terms of the driver cytokines for Tfh cells, IL-6 and IL-21 promote the differentiation of Tfh cells by acting STAT3 and inducing Bcl-6 expression, respectively.147,148 However, IL-2/STAT5 signaling strongly inhibits Tfh development by inducing Blimp-1 expression.149,150

Treg cells are a specialized CD4+ T cell subset for maintaining immune tolerance by suppressing an immune response. Treg cells are characterized by high expression of IL-2 receptor alpha chain (IL-2Rα, CD25), inhibitory cytokines IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-35, and master TF Foxp3.151,152 Two major subsets of Treg cells are identified based on their developmental origin: thymic Treg (tTreg) cells, also known as natural Treg (nTreg) cells that derive from thymus, and induced Treg (iTreg) cells that differentiate from conventional CD4+ T (Tconv) cells in the periphery after antigen stimulation and in the presence of TGF-β and IL-2.153,154 Given the importance of Foxp3, regulation of Foxp3 expression is critical for Treg cell development, maintenance, and function, in which both transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms are involved.155–158 TCR/CD28 stimulation triggers Foxp3 expression by inducing bindings of NF-κB, AP-1 and NFAT to Foxp3 enhancer/promoter regions.153,159–161 In addition, TGF-β enhances Foxp3 transcription by inducing bindings of phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3, as well as forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) and FoxO3 to the conserved non-coding sequences (CNSs) region of Foxp3.162 As the downstream of IL-2 signaling, STAT5 also increases the expression of Foxp3 through binding to CNS0 and CNS2.163,164 Regulation of Foxp3 stability will be further discussed in autoimmune disease section.

CD8+ T cell differentiation and regulation

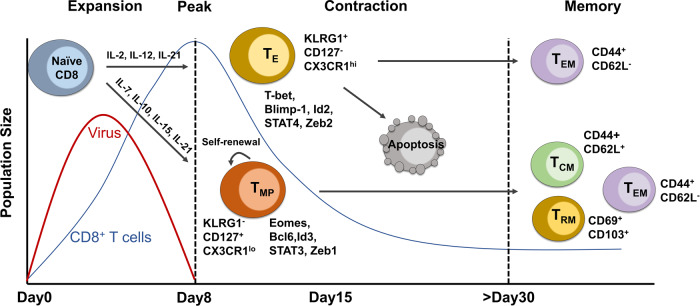

CD8+ T cells play critical roles in fighting against intracellular pathogens as well as eliminating malignant cells in cancer.165 Upon antigen stimulation, naïve CD8+ T cells undergo robust expansion to give rise to effector and memory T cells. Effector CD8+ T cells, known as CD8+ CTLs, can directly induce target cell death by the interaction between Fas/Fas ligand, and secretion of cytolytic mediator perforin, which creates pores in the target cells allowing the delivery of granule serine proteases (granzymes), to induce apoptosis. Memory CD8+ T cells provide rapid and strong protection upon antigen reencounter, which is critical for effective and long-term immunity. During CD8+ T cell differentiation, heterogeneous effector and memory populations have been identified, including short-live effector CD8+ T cells (TE), exhausted CD8+ T cells (Tex), long-live memory CD8+ T cells (TM), memory precursor CD8+ T cells (TMP), central and effector memory CD8+ T cells (TCM and TEM), and tissue-resident memory (TRM) cells, which are named by their phenotype, differentiation potential and functionality.166,167 Of note, these subsets are produced at different time window and tissue location upon immune challenge, and their differentiation is under orchestrated regulation of TFs, epigenetic modification, and metabolic programs.

Key transcription factors

Several key TFs have been well-characterized to control effector versus memory CD8+ T cell differentiation in a reciprocal and antagonistic manner (Fig. 3). These TFs include T-bet versus Eomesodermin (Eomes),168,169 Blimp-1 versus Bcl-6,170–172 Id2 versus Id3,169,173,174 STAT4 versus STAT3,173,175,176 and Zeb2 versus Zeb1.177 While T-bet, Blimp-1, Id2, STAT4, and Zeb2 are predominantly expressed in TE populations and required for effector T cell lineage and/or acquisition of CTL functions, Eomes, Bcl-6, Id3, STAT3, and Zeb1 are enriched in TM populations and support memory T cell formation and maintenance. Those two sets of TFs can either enhance or antagonize each other. For example, Id2 positively regulates T-bet, which induces Zeb2 expression; STAT3 sustains Bcl-6 and Eomes expression; Blimp-1 represses Id3 expression; Bcl-6 can both repress and be repressed by Blimp-1.169,171 Currently, collective evidence has supported that the first set of TFs are activated by TCR/costimulatory signals and/or coupled with cytokine signaling (IL-2, IL-12, type I IFN, IFN-γ, IL-21, and IL-27).170,171,173 For instance, IL-2 and IL-12 drive effector CD8+ T cell differentiation by inducing expression of Blimp-1, T-bet, and Id2 expression.171 IFN-α/β stimulates the clonal expansion and production of IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells via a STAT4-dependent pathway.178 The autocrine IFN-γ further synergizes with IFN-α to promote T-bet expression.173,179 Additionally, IL-21 and IL-27 promote Blimp-1 expression in effector CD8+ T cells.180 The second set of TFs are predominantly driven by cytokine signaling (IL-7, IL-10, lL-15, and IL-21).169,173,181 TCF-1 (a downstream factor of the Wnt-signaling pathway) and FoxO1 (a factor related to metabolic pathway) are identified as indispensable TFs for memory CD8+ T cell differentiation and maintenance.182 It will be interesting to clarify how TCR and cytokine signaling sequentially activate these two sets of TFs and how the cross-regulation occurs among them.

Fig. 3.

Temporal dynamics of CD8+ T cell response in acute infection. The population size of the virus (red line) and CD8+ T cells (blue line), as well as CD8+ T cell response along with the infection course, are indicated. Upon infection, CD8+ T cells undergo robust proliferation and reach the expansion peak on day 8, where the pathogens are rapidly cleared. CD8+ T cells at this stage can be separated into TE and TMP populations with distinct surface marker and differentiation potential. The differentiation of effector and memory CD8+ T cells is regulated by different transcriptional factors and cytokines. The majority of CD8+ TE cells undergo apoptosis at the contraction phase (8–15 days) and leave a subpopulation differentiating into TEM, whereas TMP cells keep self-renewal and give rise to TCM, TEM and TRM cells over 30 days post-infection

Epigenetic mechanisms

DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate chromatin accessibility of the regulatory regions of lineage-specific TFs and orchestrate the transcription of key genes to control CD8+ T cell development.183 DNA methylation, predominantly on CpG islands (CG dinucleotide-sense regions), has repressive effects on gene transcription by hindering the binding of TFs to promoters. During CD8+ T cell differentiation, DNA methylation is highly involved in regulating the transcriptional program of effector and memory CD8+ T cells.184–187 DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A catalyzes DNA methylation at sites such as the promoter of Tcf7, thus suppresses memory differentiation and supports effector differentiation.188 Methylcytosine dioxygenase TET2 induces DNA demethylation to promote effector differentiation while restrict memory T cell differentiation.189,190 In addition, histone modifications has either activating or repressive effects on gene transcription via organizing DNA into structural units termed nucleosomes.191 H3K4me3 and H3K9ac are activation-associated modifications, whereas H3K27me3 modification is associated with repressive transcription.191 TE-associated genes (Tbx21, Prdm1, Klrg1, Ifng, Gzma, Gzmb, and Prf1) and TM-associated genes (Foxo1, Klf2, Lef1, Tcf7, Il2ra, Cd27, Ccr7, and Sell) display decreased repressively but increases activating histone modifications during effector or memory lineage differentiation, respectively.184,186,187,192,193 Polycomb complex protein BMI1 and histone-lysine N-methyltransferase EZH2, components of the H3K27me3 reader complex, are induced by TCR stimulation and functionally support the expansion, survival and cytokine production of TE population.193 Similarly, PR domain zinc finger protein 1 (PRDM1) facilitates effector cell differentiation and suppresses memory lineage through recruiting repressive histone modifiers histone-lysine N-methyltransferase EHMT2 and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) to the Il2ra and Cd27 loci.194 Moreover, BATF enhances effector CD8+ T cell differentiation by decreasing the expression of histone deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) which inhibits T-bet expression though downregulating histone acetylation of the Tbx21 locus.195

Metabolic regulation

Growing evidence indicates that profound metabolic reprogramming is highly involved in CD8+ T cell differentiation. Naïve CD8+ T cells primarily depend on basal glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to meet their basal cellular processes.196–199 TE cells ensure high metabolic flux for the proliferation and functions by upregulating glycolysis197,199,200 and glutaminolysis.201 Upon TCR and costimulatory stimulation, activation of AKT-mTOR signaling in TE cells upregulates MYC expression, which induces glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) expression to promote glucose uptake as well as amino acid transporter SLC32A1/2 expression to increase glutamine uptake.201–203 At the same time, NFAT is also induced to upregulate GLUT1/3204 and MYC/HIF1α.197,205 TM cells differentiate and maintain the population through fatty acid oxidation fueled by long-chain and short/branched-chain fatty acids.206–208

During the process of TE towards TM differentiation, the metabolic program turns from an activated status back to a relative quiescent status. TM cells express high level of mitochondrial lipid transporter CPT1A, supporting that lipid oxidation is indispensable for memory T cell differentiation.209 In response to IL-15, TE cells upregulate CPT1A expression which mediates the transport of long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria and thereby promotes fatty acid oxidation.209 Additionally, short/branched-chain amino acid metabolism, beta-oxidation of 2-methylbutyrate, isobutyrate and isovalerate to generate ATP molecules, play a compensatory role in supporting memory T cell differentiation when long-chain fatty acids become limited.208 Upon recall stimulation, TM cells rapidly switch to glycolysis dependent on an epigenetic reprogramming controlled by TCF-1.210

Of note, there exists cross-regulations among TFs, epigenetic modification and metabolism.194,211,212 TFs and epigenetic modification co-regulate with each other, while they collaboratively regulate metabolic status.213,214 These integrated signals are involved in the fate decision and maintenance of CD8+ TE and TM populations.

T cells in acute infection and inflammation

Microbial pathogens including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa can cause acute and chronic infections in mammalian hosts, leading to various diseases even lethal damage. Owing to advances in public health management and development of vaccination, the number of deaths from pathogenic infection has reduced substantially in recent years. While infectious diseases seem faded out of the public consciousness over the past years, COVID-19 pandemic due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has caused 660 million confirmed cases and 6.6 million deaths by the end of 2022, alerting us to the danger of infectious pathogens. Though innate immune system offers the first-line defense, T cells are crucial in infectious immunity, including efficient clearance of pathogens, helping B cell response and antibody production, rapid control of reinfection, and providing long-term protection by memory formation.

Effector CD8+ T cells contribute to protective immunity during acute infections

CD8+ T cells are main responders to viral infection but also participate in defense against bacterial and protozoal pathogens. Effector CD8+ T cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) to inhibit viral replication,215 and express various chemokines to attract other inflammatory cells to sites of infection. Acute infections, defined as infections of only a short duration where the pathogens are eliminated rapidly after the peak of the immune response, are caused by infections of Armstrong strain of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), Listeria monocytogenes (LM), influenza virus, hepatitis A virus, and vaccinia virus. The dynamics of CD8+ T cell response to acute infections has been studied extensively.216–218 The response of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells can be roughly divided into distinct stages (Fig. 3): the expansion phase (0–7 days) where CD8+ T cells are actively proliferating; the peak of expansion (day 8) where the effector CD8+ T cells reach the maximum number and stop proliferating; the contraction phase (8–15 days) where majority of effector CD8+ T cells undergo apoptosis; and the memory phase (>30 days) with only a small population of cells are survived and differentiated into distinct types of memory cells: CD44+CD62L− TEM, CD44+CD62L+ TCM, and CD69+CD103+ TRM.219 The fate decision between effector and memory T cells occurs as early as the first division of activated CD8+ T cells, in which the daughter cells with high MYC and high canonical BRG1/BRM-associated factor (cBAF) preferentially differentiate into TE cells, whereas those with low MYC and low cBAF develop into TM cells.220 At the peak of acute infection, expression of KLRG1 and CD127, the IL-7 receptor subunit-α (IL-7Rα), is used to identify short-lived terminally differentiated effector cells (TE, KLRG1+CD127-) and long-lived memory precursor cells (TMP, KLRG1-CD127+). Besides KLRG1, TE cells express a range of effector molecules including cytotoxic granzymes, perforin, cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF), chemokines (CCL5 and CCL3), and chemokine receptors (CX3CR1, CXCR6 and CCR5). Recently, the expression of chemokine receptor CX3CR1 on CD8+ T cells has been used to classify effector and memory T cells.221 The level of CX3CR1 on CD8+ T cells correlates with the degree of effector differentiation as CX3CR1hi subset contains the terminally differentiated effector T cells.222 The differentiation and function of effector/memory CD8+ T cells are precisely and elaborately regulated at multiple levels, which have been described in the previous section.

Overall, CD8+ T cell responses to different microbial pathogens are similar regarding to the kinetics of T cell expansion and contraction, effector function and regulation, and memory formation. However, CD8+ T cell priming, costimulatory signaling, persistence of response and intensity of the inflammation can be different in various pathogenic infections.223–227 In the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, CD8+ T cells in severe and convalescent COVID-19 patients exhibit activated phenotypes characterized by elevated expression of CD38, HLA-DR, Ki67, PD-1, perforin, and granzyme B.228–232 Comprehensive single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis reveals that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells display increased “exhaustion” phenotype with high expression of inhibitory receptors (IRs) (Tim-3 and Lag-3) than influenza A virus- and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-reactive CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, such “exhausted” CD8+ T cells are not dysfunctional but enriched for cytotoxicity-related genes.233 Nevertheless, SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells have reduced cytokine production.233 Therefore, further studies are needed to fully elucidate the function of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells in COVID-19 patients.

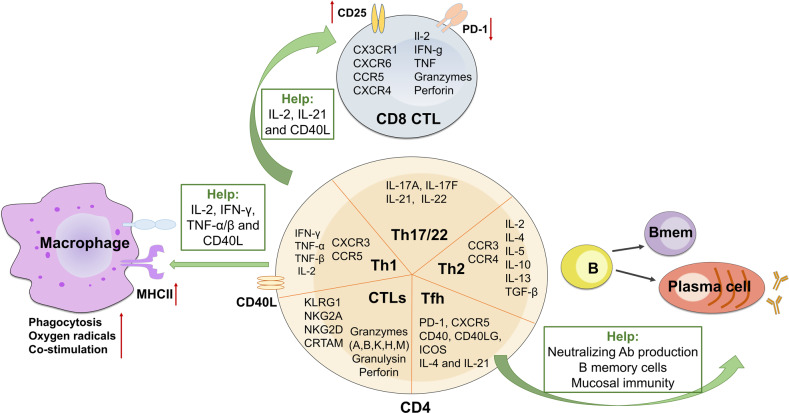

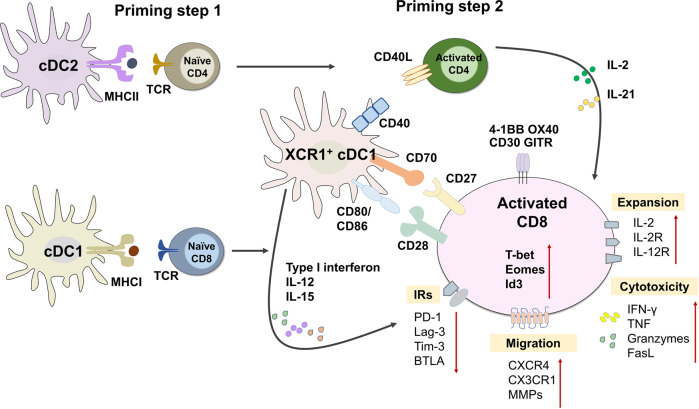

Effector CD4+ Th cells in infection

CD4+ T cells play multifaceted roles in modulating immune responses (Fig. 4), contributing to protection from a broad range of pathogenic microbes. Th1 and Th2 subsets have been long identified as crucial players in protective immunity against pathogens.234 Although effector Th cells found in vivo after infections are often heterogeneous populations, CD4+ T cells in response to viruses mainly display Th1-associated phenotypes.235 Particularly, enriched Th1 lineage is a typical feature of pulmonary infections and plays crucial roles in fighting against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), influenza virus, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), SARS and SARS-CoV-2.236–239 Th1 cells, characterized by expressing cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α/β and IL-2, chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5, and TFs T-bet and STAT4, mainly fight intracellular pathogens of viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa.76 By contrast, Th2 cells, expressing cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR4, and TFs GATA-3 and STAT6, are strong drivers of humoral immune reactions against extracellular helminthic parasites and allergic inflammation.240,241

Fig. 4.

Effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells contribute to infectious immunity. In response to infection, naïve CD8+ T cells develop into CD8+ CTLs expressing a range of chemokine receptors and effector molecules, whereas naïve CD4+ T cells develop into distinct Th1, Th2, Th17, Th22, Tfh, and CTL subsets with indicated phenotypes to exert protective functions. In addition, CD4+ T cells indirectly contribute to pathogen clearance by providing help to macrophages, CD8+ CTLs and B cell and antibody responses

Th17 response, featured by massive pro-inflammatory cytokine production, is often elicited together with Th1 cells in infections by bacterial and viral microorganisms, such as Mtb,242 S. aureus,243 MERS-CoV,244 Dengue virus,245 RSV,246 hepatitis B virus (HBV)247 and SARS-CoV-2.248 Additionally, fungal microbes, such as Pneumocystis carinii and Candida albicans can trigger strong Th17 response by inducing large amounts of IL-23 which is the key cytokine for full Th17 differentiation and function.102,249,250 Furthermore, Th22 cells are a newly identified Th subset producing IL-22 but not IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-17.251 Th17/Th22-related cytokines can target on diverse cell types, including non-immune cell populations, such as epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelium cells. Hence, Th17 and Th22 cells tend to protect against infections locally on the mucosal tissue and skin, respectively.252,253 IL-17 and IL-22 corporately augment the host immunity against infections at mucosal sites via promoting antimicrobial peptides production by mucosal epithelium and recruitment of neutrophils to eliminate bacteria and fungi.254

Moreover, CD4+ CTLs contribute to pathogen clearance through direct cytolytic activity.77,255,256 This subset of CD4+ T cells attracts much attention recently owing to their important functions in protecting against infectious disease, promoting human longevity, and mitigating tumor progression.257–259 CD4+ CTLs have been largely observed in both human and mice infected with viruses,235 such as cytomegalovirus (CMV),260 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1,261 hepatitis viruses (HBV, HCV and HDV),262 Epstein–Barr virus (EBV),263 Dengue virus,264 influenza virus,265,266 and SARS-CoV-2.267 CD4+ CTLs are characterized by expression of KLRG1, natural killer group 2 (NKG2A), NKG2D, the class I-restricted T cell-associated molecule (CRTAM) and downregulated CD27/CD28.77,256 The cytotoxic activities of CD4+ CTLs attribute to the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, perforin, granzymes (A, B, K, H, and M), granulysin, and death receptor-dependent signaling (Fas and TRAIL).268–270 The transcriptional regulation of CD4+ CTLs is highly comparable to that of CD8+ CTLs, in which TFs T-bet, Eomes and Runx3 play critical roles in driving CD4+ CTL programming while ThPOK expression limits cytotoxic functions in CD4+ T cells.271–273 Additionally, IL-2 could drive the cytolytic phenotype of CD4+ CTLs,274 while pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12, IL-6, and IFN-α increase granzyme B and perforin production and target killing activity.275 It remains unclear about the precursors of CD4+ CTLs or whether this population is merely the terminal differentiated Th1 cells. However, more evidence claims that CD4+ CTLs are a separate Th subset in regards to its differentiation trajectory, effector function and regulatory networks.255,276,277 Furthermore, heterogeneous populations within CD4+ CTLs have been identified in viral infection.277,278 In general, CD4+ CTLs are highly associated with antiviral immunity, however, aberrant CD4+ CTL activity has also been linked with immunopathology in some settings.279–281 For example, CD4+ CTLs contribute to the disease severity during SARS-CoV-2 infection267,282 and lung fibrosis.267,283

Accumulating evidence has suggested that more than one type of Th subsets can be triggered during the infection, and both synergy and balance among Th cells contribute to infection control. For instance, costimulation of Th1, Th2 and Th17 responses is commonly observed in various microbial infections, such as Mtb,284,285 Echinococcus multilocularis,286 Aspergillus fumigatus,287 HIV,288 SARS-CoV-2.248 Meanwhile, Treg cells can be induced during infection to prevent overstimulation of immune response and “self-attacking”.289–292 During Mtb infection, activation of macrophages induced by Th1-derived IFN-γ is crucial to control the tuberculosis. However, persistent Th1 response and pro-inflammatory cytokines can cause lung fibrosis and necrosis. Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β are prominent to prevent pathology induced by aberrant Th1 response.293 Enhanced Th2 response during SARS-CoV-2 and influenza infection is associated with severe disease symptoms by inhibiting antiviral responses.241

Effective control of infection relies on CD4+ T cell help

CD4+ Th cells are indirectly involved in pathogen control by regulating functions of other immune cells, such as activating innate immune populations, assisting CD8+ CTL response and B cell maturation and antibody production (Fig. 4). CD4+ T cells, mainly Th1 population, are central for activation of pro-inflammatory macrophages by releasing cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α/β and expressing CD40L.76 Activated macrophages augment their antimicrobial effectiveness by increasing microbial phagocytosis, production of nitric oxide (NO) and oxygen radicals, expression of MHC class II molecules and a number of costimulatory molecules for effective antigen presentation to T cells.294 Activated macrophages are also important for efficiently eliminating intracellular pathogens such as mycobacteria which grow primarily inside of macrophages and are shieled from CTLs and neutralizing antibodies.295

Furthermore, CD4+ T cell help is essential for optimal and effective CD8+ T cell response,51 although the requirement for primary CD8+ T cell response remains controversial. Some studies have shown that in the absence of CD4+ T cells, the primary CD8+ T cell expansion and cytotoxic functions during LCMV and LM infection are unaffected.296,297 However, other studies have reported that CD4+ T cells, particularly their memory subset, are required for primary effector CD8+ T cell response to herpes simplex virus (HSV) and influenza virus.298–301 The controversial effects of CD4+ T cell help for primary CD8+ T cell response are likely derived from different help-evaluation models.301 On the other hand, profound and consistent evidence indicates that CD4+ T cell help is indispensable for memory CD8+ T cell generation and their recall response to antigen restimulation.302–304 Mechanistically, CD4+ T cells support CD8+ T cell responses via cytokines IL-2 and IL-21, and CD40L signaling.301,305–307 Additionally, CD4+ T cells have been shown to help CD8+ T cells by enhancing their CD25 expression and downregulating PD-1 expression.308,309

CD4+ Tfh cells are essential for B cell responses and generating protective antibodies against viral, bacterial, parasite, and fungal pathogens in mice, non-human primates, and humans.131,310 The protective effects of Tfh cells on humoral immunity attribute to multiple mechanisms.132 First, Tfh cells help the production of protective antibodies that directly neutralize pathogens and inhibit their replication, and indirectly promote pathogen clearance through antibody opsonization. Tfh cells have long been known to highly correlate with broadly neutralizing antibodies in HIV infection.311 During SARS-CoV-2 infection, increased circulating Tfh (CCR7loPD-1+ICOS+CD38+) cells and production of neutralizing antibodies were observed in COVID-19 convalescent individuals and associated with mild symptoms.312,313 In contrast, defective Tfh cell response and delayed development of neutralizing antibodies were found in deceased patients.314 Second, Tfh cells support memory B cell formation and response, which is important for rapid humoral response upon reinfection. Thirdly, Tfh cells in mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) can also promote IgA production and function to modulate respiratory and gastrointestinal-tract infections.315 Collectively, CD4+ T cells are crucial mediators for supporting, promoting, and regulating both humoral and cellular immunity to resolve the infections effectively.

Chronic infection and cancer: persistent antigenic stimulation

In contrast to acute infections, antigen stimulation is persistent in chronic infection and cancer. It is now well-accepted that most T cells in such circumstances adopt a unique differentiation trajectory—exhaustion.316,317 Exhausted T (Tex) cells have been identified in many high grade chronic viral infections, such as HIV, HBV, HCV, and LCMV-Clone 13 strain,318–321 and in almost every mouse and human cancer.322,323 A wealth of recent studies at single-cell level have revealed that Tex cells constitute heterogenous populations with distinct transcriptional, epigenetic and functional signatures, playing critical roles in protecting against infections and tumors. The discovery of stem-like progenitor CD8+ Tex (Tpex) cells, the main responder to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), attracts a large attention in both preclinical and clinical research field for developing next-generation cancer immunotherapies.322,324 In this section, we will summarize current understandings of the cellular and functional features of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in chronic infection and tumor, their developmental pathways, regulatory mechanisms, CD4+ T cell help for CD8+ CTL responses, as well as contributions to anti-tumor immunity and checkpoint blockade.

Exhausted CD8+ T cells

Exhausted CD8+ T cells represent an entirely distinct differentiation trajectory with unique cellular phenotype, heterogeneity, and functional capacity.219,325,326 Along with the exhaustion, CD8+ T cells gradually lose production of IL-2 and TNF-α, and cytotoxic function.327 Compromised IFN-γ production occurs at more later stage of exhaustion and is associated with terminally differentiated Tex.328 But terminal CD8+ Tex may retain the ability to degranulate and produce chemokines and cytokines, such as MIP1α, MIP1β, RANTES, and IL-10 329. Different from TM cells in acute infection that undergo steady homeostatic self-renewal responding to cytokines IL-7 and IL-15,330 Tex cells display defects in responsiveness to homeostatic cytokines due to impaired IL-7Rα and IL-2/15Rβ signaling pathways.331,332 Instead, persisting antigen stimulation drives a proliferative progenitor pool of Tex cells,333,334 that Tex cells adopt a self-renewing mechanism dependent on continuous TCR stimulation.333 In addition, a key hallmark of CD8+ Tex cells is the upregulated and sustained expression of multiple IRs, such as PD-1, CTLA-4, Lag-3, TIGIT, Tim-3, CD39, 2B4, CD160, etc.329,335 The extent and coexpression of IRs directly correlate with the severity of exhaustion.335,336 On the other hand, Tex cells also express costimulatory molecules which, however, favor T cell exhaustion during chronic infection and tumor. For example, costimulation of CD27 and CD28 results in an enhanced T cell exhaustion.337,338 CD28 signaling is compromised due to loss of competition to CTLA-4 for B7 family ligands.338 PD-1 signaling further suppresses T cell function by specifically inducing CD28 dephosphorylation.339

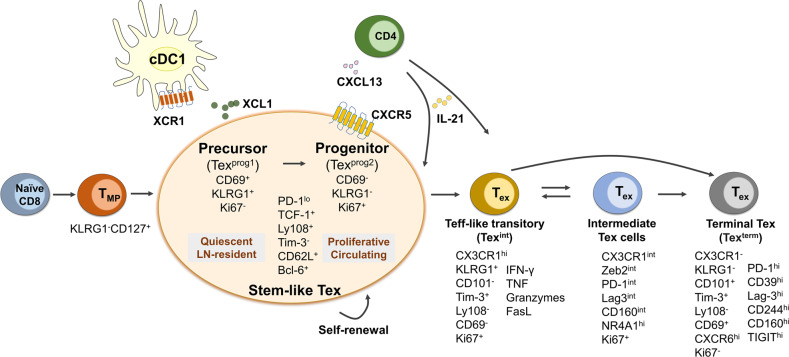

Heterogeneity and differential trajectory of CD8+ Tex cells

The exhaustion/dysfunction of CD8+ T cells in chronic infection is established progressively with sequential phases.340,341 Analysis of CD8+ cell chromatin states define two discrete dysfunctional states: early reprogrammable and late non-reprogrammable T cells that the former ones are plastic and retain the potential to form memory after adoptive transfer, whereas the latter are fixed dysfunction with massive IR expression.341,342 Regarding to Tex cell origin, it was pointed out that CD8+ Tex cells arise from the same pool of KLRG1-CD127+ TMP cells in acute infection.343 The differentiation divergence of virus-specific CD8+ T cells responding to acute and chronic viral infections occurs as early as 4.5 days post-infection.344 However, under persistent antigen stimulation, these precursors progressively lose memory potential and develop into Tex cell state.342,343 With the rapid development of single-cell technologies, extensive analysis of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) reveal a diverse spectrum of exhausted CD8+ T cells in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma, breast cancer, liver cancer, and colorectal cancer.324,345–351

The CD8+ Tex cells being a distinct differentiation trajectory largely attributes to the identification of the stem-like, self-renewing Tpex population which is marked by expression of TCF-1 and surface profile of PD-1loTim-3-Ly108+CXCR5+.340,352 TCF-1-expressing Tpex cells are responsible for the maintenance of Tex cell populations in chronic viral infection and tumor.353,354 Tpex cells adopt a branched differentiation paradigm (Fig. 5), where they both self-renew and give rise to terminally differentiated exhausted T cells.334,344 Despite sharing similar phenotypes, the stem-like Tpex cells can be further separated into early precursor and late progenitor stages: the CD69+KLRG1+Ki67- CD8+ Tex precursors are more quiescent, lymph node (LN)-resident and having a baseline level of proliferation, whereas CD69-KLRG1-Ki67+ progenitors have robust proliferation and access to circulation.352,355 Recently, more markers are identified to define Tpex subsets. Tsui et al. reported that a small subset of TCF-1+CD62L+ Tpex cells are the stem-like population essential for long-term self-renewal, maintenance of Tex lineage and responsiveness to immunotherapy.356 In human individuals experienced latent infection such as CMV or EBV, TCF-1+ progenitors are comprised of two subsets based on PD-1 and TIGIT expression. The PD-1-TIGIT- progenitors are committed to a functional Tex differentiation, whereas PD-1+TIGIT+ progenitors are differentiated into a dysfunctional and exhausted state.357 Additionally, XCL1 is found expressed in CD8+ Tpex cells and associated with XCR1+ conventional type I dendritic cells (cDC1s).358

Fig. 5.

Heterogenous populations and differential trajectory of CD8+ Tex cells in chronic infection and tumor. Under persistent antigen stimulation, CD8+ T cells adopt an exhaustion differentiation trajectory of naïve → TMP → stem-like Tpex → effector-like transitory → intermediate → terminal Tex cells. Expression of signature markers and effector molecules at each Tex population is indicated. The stem-like Tpex cells are further divided into early precursor and late progenitor stages with discrete phenotype, proliferative status and preferential location. Tex subsets identified from different studies may use different names which are marked in the parentheses. CXCL13 and IL-21 derived from CD4+ T cells are critical for differentiation of CXCR5+ Tpex cells and CX3CR1+ Teff-like transitory Tex cells, respectively. CD8+ Tpex cells interplay with cDC1s through XCL1/XCR1 axis

Persistent antigen exposure induces downregulation of TCF-1, and drives Tpex differentiation into a “transitory” effector state and terminal exhausted T cells (Fig. 5). The transitory effector T (Teff)-like cells are critical for viral and tumor control and characterized by expression of chemokine receptor CX3CR1, producing IFN-γ, TNF and granzyme B, and enhanced cytotoxicity and cell proliferation.359,360 Generation of CX3CR1+ subset strongly depends on CD4+ T cell help and IL-21.360,361 Hudson et al. propose that Tpex differentiation follows a linear developmental trajectory where Tpex cells generate CX3CR1+Tim-3+CD101- transitory Teff-like T cells that further give rise to CX3CR1-Tim-3+CD101+ terminal Tex cells.359 Similarly, the expression of Ly108 and CD69 defines four subsets of Tex cells with a hierarchical developmental progression from Ly108+CD69+ (referred to Texprog1) to Ly108+CD69− (Texprog2) to intermediate differentiated Ly108−CD69− (Texint) cells and the most terminally differentiated Ly108−CD69+(Texterm) subset.355 Of note, Texint cells share similar transcriptional program to the CX3CR1+ Teff-like Tex cells identified in previous studies.359,360 Recently, a novel Tex subset expressing NK-associated genes (NKG2A and CD94) was uncovered within the Texint cell population.362 More evidence supporting the Tex cell differentiation trajectory comes from comprehensive analysis of antigen-specific T cells in patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive head and neck cancer. Paired scRNA-seq analysis and TCR sequencing of HPV-specific CD8+ T cells sorted by MHC class I tetramers revealed that antigen-specific PD-1+TCF-1+ stem-like CD8+ T cells could proliferate and differentiate into Teff-like transitory and terminally differentiated cells.363 In addition, epigenetic landscape analysis demonstrates that the phenotypic changes of Tex cell development coincide with the chromatin accessibility of key genes.355,359 Long-term antigen stimulation leads to epigenetic reprogram which enforces the terminal exhaustion of T cells marked by high expression of IRs, diminished effector-related molecules (IFN-γ, TNF, granzymes, and T-bet) and loss of stemness and proliferation potential (TCF-1, MYB, MYC, and Ki67).219,355,359 Furthermore, in infection with chronic LCMV-Clone 13, a “bridging population” between Teff-like transitory and terminal exhausted Tex cells is characterized by intermediate expression of CX3CR1, Zeb2 and IRs, but high expression of NR4A1 (encoding NUR77), suggesting a recent activation by TCR stimulation.364 Chemokine receptors CXCR6 and CX3CR1 can be used to discriminate these three populations: Teff-like transitory cells (CX3CR1hi), intermediate Tex cells (CX3CR1int) and terminal exhausted Tex cells (CX3CR1loCXCR6hi).364 Recent high-dimensional single-cell multi-omics have revealed more heterogenous Tex clusters with distinct phenotypic, transcriptomic, epigenetic and functional patterns, which also display disease- and tissue-specificity.364–366 It is noteworthy that exhausted T cells can be also induced in acute infection with strong T cell stimulation. For instance, severe acute respiratory syndrome elicited during SARS-CoV-2 infection induces T cell exhaustion phenotypes with high level of IRs expression.229,233

Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of CD8+ Tex cells

The differentiation of CD8+ Tex cells is tightly controlled by transcriptional and epigenetic networks. In chronic infection and tumors, TCF-1 identifies the stem-like CD8+ Tpex cells.354,367,368 Accordingly, mice with Tcf7 deficiency could not develop stem-like Tpex cells and Tex populations,353 whereas overexpression of Tcf7 led to enhanced Tpex program as well as antiviral and anti-tumor immunity.369 TCF-1 plays central roles in Tpex cells by organizing transcriptional regulatory networks.354,370 TCF-1 coordinates with FoxO1 which also acts as an upstream regulator of TCF-1 expression to promote and maintain the stemness in CD8+ T cells by augmenting pro-memory TFs Eomes, Id3, c-Myc, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6 expression while inhibiting effector-related TFs T-bet, Id2, Runx3, and Blimp-1.367,368,370–372 MYB (also known as c-Myb) is a pivotal TF for CD8+ central memory and Tpex cell generation and maintenance by acting as a transcriptional activator of Tcf7.356,373 Moreover, BACH2 promotes stem-like CD8+ T cell commitment in chronic infection and cancer by enforcing the transcriptional and epigenetic programs.374

TOX, a high-mobility group box DNA-binding protein, has recently emerged as a critical regulator for Tex cell programs.375–377 Enforced expression of TOX is sufficient to induce an exhausted T cell-associated transcriptional program with increased expression of IRs.376,378 While TOX deficiency has no impact on CD8+ T cells differentiation and effector function in acute infections, deletion of TOX in tumor-specific T cells inhibits the upregulation of IRs and augments the cytokine production, effector functions, and TCF-1 expression.375,378 Although TOX deficient T cells display a “non-exhausted” immunophenotype, those T cells remain hyporesponsive and ultimately diminish.375,378 In fact, TOX deficient CD8+ T cells fail to persist and differentiate into Tex cells, indicating that TOX-regulated exhaustion indeed protects T cells from overstimulation and activation-induced cell death.375,376,378 Additionally, TOX and nuclear receptor NR4A form positive feedback loops to impose CD8+ T cell dysfunction and exhaustion.379–381 BATF is another important TF regulating T cell exhaustion, however, its role remains controversial. Some studies report that BATF facilitates viral clearance by driving the transition from TCF-1+ Tex progenitors to CX3CR1+ effector cells during chronic viral infection.382 Moreover, BATF cooperates with IRF4 to resist exhaustion; overexpression of BATF promotes the survival and anti-tumor immunity in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells.383 However, others claim that BATF drives T cell exhaustion by directly upregulating exhaustion-associated genes, thus BATF depletion could significantly enhance T-cell resistance to exhaustion and exhibit superior efficacy against solid tumors in CAR-T cells.384–386

Intriguingly, Tex cells express certain TFs shared by T cells in acute infection, but with distinct gene transcription,387 suggesting context-dependent functions of these TFs. For instance, Eomes and T-bet are dually required for Tex cell generation.334 Eomes expression is elevated in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and high level of Eomes promotes exhaustion.388,389 But high expression of T-bet was found associated with Tpex and effector-like Tex subset.334,390,391 In addition, TF NFAT family which has a well-established role in mediating T cell activation when partners with AP-1,392 has been shown to regulate Tex cell differentiation. NFATc1 drives exhaustion program by promoting IR expression,393 whereas NFATc2 prevents the dysfunction of CD8+ Tex cells.394 The major differences of CD8+ T cells in acute and chronic infections are compared (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of CD8+ T cells in acute and chronic infections

| Infection type | Infectious gents/condition | Characteristics | Stages | Fate | Subsets | Surface marker | Key TF | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | LCMV-Armstrong, LM, influenza virus, HAV, RSV, vaccinia virus | IFN-γ, TNF, IL-2, KLRG1, Granzymes, Perforin | expansion, contraction, memory | TE, TMP, TEM, TCM, TRM | TE | KLRG1, CX3CR1, CXCR6, CCR5 | T-bet, Blimp-1, Id2, STAT4, Zeb2 | 169,173,182,193,219,223 |

| TMP | CD127, CD62L | Eomes, TCF-1, FoxO1, Bcl-6, Id3, STAT3, Zeb1 | ||||||

| Chronic | LCMV-Clone 13, HIV, HBV, HCV, CMV, EBV, SARS-CoV-2, Cancer | Loss of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α; Expression of IRs (PD-1, CTLA-4, Lag-3, TIGIT, Tim-3, CD39, 2B4, CD160) | Tex precursor, Tex progenitor, Teff-like transitory, Intermediate Tex, Terminal Tex | Tex | Teff-like | KLRG1, CX3CR1, Tim-3 | T-bet, Id2, Runx3, Blimp-1 | 219,323,325,326,340,355,359,367,370,377,387 |

| Tpex | Ly108, CD62L, CXCR5, XCL1 | TCF-1, FoxO1, Eomes, Id3, c-Myc, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, MYB, BACH2 | ||||||

| Tex | PD-1, CD101, Tim-3, CXCR6 | TOX, BATF, Eomes, T-bet, NFAT |

The underlying mechanisms that govern the distinct transcriptional features of Tex cells remain poorly understood, but at least partially, are controlled by epigenetic programming. CD8+ Tex cells exhibit a unique chromatin landscape different from effector and memory T cells.342,355,362,395 The chromatin accessibility of key exhausted-associated genes such as TCR signaling, cytokines, costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors has experienced dynamically epigenetic reprogram.365,396 For instance, the gene regions around Tcf7 and Id3 are more accessible in stem-like Tpex cells while that in Prdm1, Id2, and Pdcd1 are more accessible in exhausted CD8+ T cells.397,398 Particularly, TOX acts as a crucial regulator of epigenetic programming of CD8+ Tex cells by repressing the chromatin accessibility of genes involved in effector cell differentiation. Additionally, TCF-1 regulates gene transcription by altering the three-dimensional (3D) genome organization.399,400 A prominent feature of Tpex cells is that the exhaustion commitment can be transmitted to their progeny even when adoptive transferred into new hosts received acute infection.401 The underlying mechanisms of such exhaustion inheritage are derived from epigenetic imprints which once are established, they can not be reversed by change of exogenous environment or by PD-(L)1 blockade.402–404

Tex subsets contributing to anti-tumor immunity and ICB

Tumors with high infiltration of T cells are generally considered as immune-inflamed or “hot” tumors. However, intratumoral T cells may not be tumor-reactive. TCR repertoire analysis reveals that the tumor recognizing T cells were limited to merely 10% of intratumoral CD8+ T cells.405 ICB can robustly reinvigorate Tex cell function, making it one of the most promising cancer therapies in the clinic.406–408 Antibodies targeting IRs on tumor-infiltrating T cells, such as PD-1/PD-L1 (among others), have been demonstrated impressive clinical activities across a variety of cancer types. Despite large success, ICB faces clinical challenges of low responsive rate, drug resistance, and immune-related adverse events (irAEs).409,410 Thus, it is of great significance to understand which subset of CD8+ T cells respond to ICB and how. Among heterogenous CD8+ Tex cells, it is now well-appreciated that the PD-1+TCF-1+ stem-like Tpex cell population mainly mediates tumor responses to checkpoint blockade.353,410,411 Comparison between the responder and non-responder of melanoma patients receiving ICB treatment demonstrates that the frequency of TCF-1hi tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells predicts positive clinical outcome.412 This CD8+ Tpex cell population has also been observed in human NSCLC, colorectal cancer, HPV-positive head and neck cancer and bladder cancer, and their number was augmented following ICB treatment.363,411,413,414 Interestingly, ICB could control tumor growth in mice depleted TCF-1-expressing T cells, indicating that later differentiated Tex cells may also be targeted by ICB.411 Indeed, comprehensive transcriptomic and TCR clonal analysis reveal that tumor/ICB-responsive CD8+ T cells including neoantigen-specific ones exhibit enhanced exhaustion compared to non-tumor-reactive bystander CD8+ T cells.415,416 Accordingly, differentiation from TCF-1+ Tpex cells into late stage of Tex cells expressing PD-1 and Tim-3 favors the tumor control.417,418 Thus, high expression of PD-1 and/or CTLA-4 on tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells provides a predictive biomarker for responsiveness to ICB therapy.419,420

Beyond, it is also critical to address the effects of ICB on CD8+ T cell state. It has been shown that effective immunotherapies can induce remarkable remodeling of tumor environment (TME) and systemic immune activation in multiple tissues.421 Paired scRNA-seq and TCR-seq on tumor biopsies from NSCLC patients revealed that the Tpex population was accumulated in responsive tumors but not in non-responsive ones after anti-PD-1 therapy.422 The data also depicts that the increased Tpex cells are mainly derived from local expansion or replenishment from peripheral T cells with pre-existing clonotypes, a phenomenon called “clonal revival”.422 While the effect of ICB primarily relies on pre-existing state of intratumoral T cells, ICB can alter the TCR repertoire to generate novel T cell clonotypes, which is referred to as “clonal replacement”.422,423 Moreover, intratumoral exhausted T cell populations and their immunological responses to ICB exhibit features of spatial distribution.424 Studies in both mouse and human tumors have demonstrated that tumor-draining LNs (TdLNs) are the preferential reservoirs for TCF-1+ Tpex cells that remain stable regardless of the changes in TME and sustain continuous development of anti-tumor T cells.425,426 Blockade of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1)-mediated T cell egress from TdLNs remarkably decreased the frequency of intratumoral CD8+ Tpex cells and the tumor eradication efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy.421,426 The clonal overlapping between tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and proliferating CD8+ T cells in the circulation in cancer patients following anti-PD-1 treatment highly suggests a recruitment from secondary lymphoid organs.427 A group of bona fide tumor-specific memory CD8+ T cells within TdLNs are important responders to PD-1-based ICB, highlighting their potentials in anti-tumor immunotherapy.428 Inherent in this theory, local (intratumoral, intradermal or intrapleural) administration of ICB antibodies, compared to systemic (intravenous or intraperitoneal) injection, results in enhanced tumor regression due to antibody accumulation and Tpex cell expansion within TdLNs.429,430

Complex CD4+ T helper cells

Robust and functional CD4+ T cell responses are essential for effective pathogen clearance and tumor eradication. Compared to well-defined CD8+ Tex cell differentiation, the cellular and functional signatures of CD4+ T cells in chronic disease settings are little characterized, especially with the complexity of multiple Th subsets. CD4+ T cells play multifaceted roles in chronic infection and tumor: constituting both favorable and deleterious subsets, enhancing CD8+ T cell function, and responding to ICB,427,431 which highlights potential next-generation therapeutics of harnessing CD4+ T cell function.

Are CD4+ T cells exhausted?

The effects of persistent antigenic stimulation on CD4+ T cell phenotype, differentiation and function remain less understood. Whether CD4+ T cells become “exhausted” during chronic infection remains a question for a long time. Controversial results were obtained as viral-specific CD4+ T cells lose effector function and produce reduced IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 during chronic infection,432,433 but the production of IL-10 and IL-21, the important cytokines in chronic infection for sustaining CD8+ T cell and B cell responses,434–436 are increased.434,437,438 Transcriptional analysis of CD4+ T cells during chronic (LCMV-Clone 13) infection has demonstrated a unique exhaustion-associated molecular and transcriptional profile, which is distinct from CD8+ Tex cells and effector or memory CD4+ T cells in acute (LCMV-Armstrong) infection.439 In addition to reduced cytokine production, CD4+ Tex cells express markedly upregulated IRs including PD-1, CTLA-4, CD200 and BTLA, and costimulatory receptors OX40, CD27 and ICOS.439 Core TFs involved in CD4+ Tex cells include Eomes, Blimp-1, Helios, Klf4, and T-bet.439 During LCMV-Clone 13 infection, viral-specific CD4+ T cells formed multiple clusters which could be broadly grouped into Th1, Tfh and Th1/Tfh hybrid clusters at different stages, suggesting an altered Th lineage differentiation in chronic infection.431 Notably, persistent viral infection drives a progressive loss of Th1 response likely due to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory signaling pathway,431,440 but skews CD4+ T cells toward Th2, Th17, Treg, Tfh, and allergic CD4+ T cell lineages.439 Different from TCF-1+ CD8+ Tpex cells, TCF-1 expression in chronic virus-specific CD4+ T cells does not adequately define stem-like progenitor CD4+ T cells, rather marks and promotes Tfh cell development.431 Recently, Xia et al. identified a population of memory-like TCF-1+Bcl-6lo/− virus-specific CD4+ T cells emerged as the progenitor cells that gives rise to Teff and Tfh cells, sustaining CD4+ T cell response in chronic infection.441 Importantly, such CD4+ progenitor cells play pivotal roles in anti-tumor response preferentially at site of TdLNs.441 Hence, CD4+ T cells display exhausted yet functional phenotype in chronic infection.

CD4+ Th cell subsets

Th1 and Th2

Th1 cells predominantly exert the anti-tumor activity. The frequency of Th1 subset and IFN-γ production in TME correlate positively with better clinical outcomes in multiple tumor types including melanoma,442 breast,443,444 ovarian,445 lung,446 colorectal,447 and laryngeal cancers448 (Table 2). Th1 cells promote tumor rejection by shaping an anti-tumor immune environment and indirectly supporting effector functions of other immune cells.449,450 Th1 cells are an important CD4+ T cell subset providing help for CD8+ T cell response and function,451 which will be elaborated at the later section. The migration of effector CD8+ T cells and NK cells in TME depends on chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL9 and CXCL10 which are predominantly expressed by Th1-related IFN-γ-activated macrophages, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor cells.452–454 In addition, IFN-γ and IL-2 produced by Th1 cells enhance the survival, proliferation and cytolytic function of CD8+ CTLs and NK cells.449,455 IFN-γ can significantly enhance MHC I and MHC II expression and tumor-derived antigen presentation on tumor cells.456,457

Table 2.

CD4+ T helper cell subsets in tumor immunity

| Th subset | Phenotype | Tumor immunity | Tumor types | Functions | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th1 | CXCR3, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, T-bet | anti-tumor | Melanoma, breast, ovarian, lung, colorectal and laryngeal cancers | activate macrophages, CAFs and tumor cells | 452–454 |

| enhance MHC I and MHC II expression | 456,457 | ||||

| attract NK and CD8+ T cells | 452–454 | ||||

| support effector functions of NK and CD8+ T cells | 449,455 | ||||

| Th2 | IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, GM-CSF | anti-tumor | Plasmacytoma, melanoma, myeloma, breast cancer | activate eosinophils and M2-type macrophages | 461–463 |

| enhance NK cell cytotoxic activities | 464 | ||||

| induce cancer cell terminal differentiation | 465 | ||||

| IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β | pro-tumor | Pancreatic and breast cancer | promote breast cancer metastasis | 466 | |

| suppress Th1 response | 467,468 | ||||

| Th17 | IL-17A, IL-17B, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23 | anti-tumor | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, gastric adenocarcinoma, cervical adenocarcinoma ovarian, colorectal, lung and breast cancers | induce cancer cell apoptosis | 512 |

| enhance recruitment of anti-tumor NK cells, DCs, neutrophils and macrophages | 513–516 | ||||

| attract effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration | 474,514,517,518 | ||||

| IL-17A, IL-17D, IL-25/IL-17E | pro-tumor | Breast cancer, melanoma, bladder carcinoma, B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, colorectal, lung, prostate, liver, pancreatic and gastric cancers | stimulate tumor cell growth and inhibit apoptosis | 482–485 | |

| promote CSCs maintenance and activation | 486,487 | ||||

| enhance tumor invasion and metastasis | 488–490 | ||||

| promote angiogenesis | 491–493 | ||||

| promote MDSCs, TAMs and neutrophils | 494–500 | ||||

| constrain effector NK and CD8+ T cells | 501,502 | ||||

| induce terminal CD8+ Tex cell differentiation | 503 | ||||

| affect vascular endothelial cells and keratinocytes | 504–506 | ||||

| Th9 | IL-9, IL-21 | anti-tumor | Melanoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, lung, breast and colorectal cancers | direct tumor cell killing by granzymes | 521,522 |

| promote recruitment of DCs | 524,525 | ||||

| induce CD8+ CTL and NK cell responses | 98,522,523 | ||||

| elicit IFN-α/β production by monocytes | 526 | ||||

| induce mast cell activation | 521,527 | ||||

| pro-tumor | Hodgkin lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, B and T cell lymphomas, CRC, HCC, lung, mammary, breast cancers | enhance tumor cell survival and migration | 532–536 | ||

| induce EMT and metastatic spreading | 488 | ||||

| mediate immunosuppression of mast and Treg cells | 537 | ||||

| Treg | IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α | anti-tumor | CRC, HNSCC, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer, esophageal cancer, oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas | suppress pro-tumor Th17 responses | 548 |

| express pro-inflammatory cytokines | 549,550 | ||||

|

CD25, ICOS, OX40, 4-1BB, GITR, PD-1, CTLA-4, Lag-3, Tim-3, TIGIT, CCR4, CCR8 IL-10, TGF-β, IL-35, IL-33, IL-37 Foxp3, FoxO1, STAT5, NFAT, T-bet, Helios, Nr4a, Foxp1 |

pro-tumor | HCC, melanoma, breast, lung, cervical, gastric, bladder, renal, endometrial and ovarian cancers | kill effector T cells, APCs and NK cells | 554,555 | |

| produce inhibitory cytokines | 556–558 | ||||

| express coinhibitory molecules | 539,559–561 | ||||

| suppress APCs function | 541,567 | ||||

| suppress NKT cell cytotoxic activity | 568 | ||||

| facilitate suppressive activity of MDSCs | 569,570 | ||||

| produce adenosine by CD73 and CD39 | 571,572 | ||||

| compete IL-2 with effector T cells | 541,573 | ||||

| produce IDO | 574,575 | ||||

| Tfh |

CXCR5, PD-1, ICOS, Bcl-6 IL-4, CXCL13, IL-21 |

anti-tumor | Melanoma, breast, colorectal and lung cancers | promote the formation of TLSs | 479,597 |

| induce pro-inflammatory cytokines | 132,598 | ||||

| activate complement cascade | 132,598 | ||||

| promote effective cytotoxic lymphocytes | 132,598 | ||||

| enhance CD8+ T cell response | 436,592,602 | ||||

| promote GC response and antibody production | 312,603,1109 | ||||

| support B cells and memory B cells | 606,607 | ||||

| respond to PD-1-based ICB | 590,608 |

The role of Th2 cells in tumor progression remains controversial with both favorable and deleterious effects458–460 (Table 2). Previously, Th2 cells have been shown to suppress tumor growth by activating eosinophils as the cytotoxic effector cells in murine plasmacytoma and melanoma.461,462 Adoptive transfer of tumor-specific Th2 cells induced massive accumulation of M2-type macrophages at the tumor site, which triggered an inflammatory immune response to eliminate myeloma cells.463 Memory Th2 cells display potent anti-tumor activity by producing IL-4 to enhance NK cell cytotoxic activities.464 Moreover, Th2 cells can directly block breast carcinogenesis by secreting IL-3, IL-5, IL-13, and GM-CSF, which induce the terminal differentiation of the cancer cells.465 However, in pancreatic cancer, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) produced by CAFs attracts and induces Th2 cells, which correlates with reduced patient survival.459 Th2 associated IL-4 signaling in monocytes and macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis.466 Th2 cells can also attenuate Th1-associated anti-tumor responses through IL-4 signaling.467,468 In accordance with this notion, Th1-dominant immune response—upregulation of Th1-related response while downregulation of Th2-associated response—can be used as positive prognostic indicators for certain cancers.469–471 The discrepancy of Th2-mediated tumor immunity may attribute to different tumor types and distinct Th2 cell state. For example, studies have suggested that tumor-promoting Th2 cells have high levels of IL-10 and TGF-β, whereas Th2 cells with high expression of IL-3, IL-5, IL-13, and GM-CSF exhibit pro-inflammatory and anti-tumor immunity.465,472

Th17

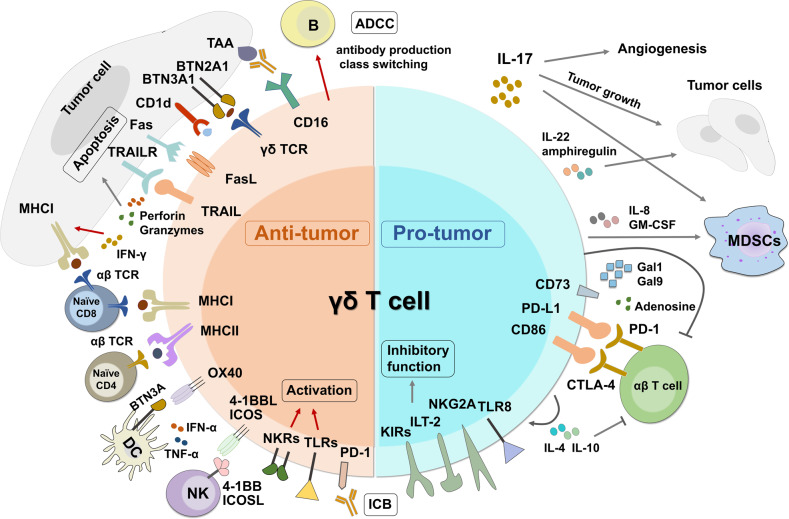

Th17 cells are specifically accumulated in many types of human tumors.473 Cytokine milieu formed by IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, and TGF-β produced by tumor cells, CAFs and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) supports Th17 cell differentiation and expansion.474,475 However, the effects of Th17 cells and cytokine IL-17 on tumor immunity are contradictory.473,476 Therefore, the presence of Th17 cells is associated with either good or poor prognosis depending on tumor types477–479 (Table 2). The pro-tumor function of Th17 cells is attributed to both direct effects on tumor cells and indirect effects of inducing a pro-inflammatory environment.480,481 Th17 cells and IL-17 strongly stimulate tumor cell proliferation by activating growth-related kinases and TFs, while inhibit their apoptosis by acting on anti-apoptotic proteins.482–485 Th17 cells and IL-17 promote cancer stem cells (CSCs) maintenance, pro-tumorigenesis and activation.486,487 Th17 cells also enhance tumor invasion and metastasis in lung, prostate, liver, and pancreatic cancers by inducing tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression, and chemokine expression.488–490 A key mechanism for the pro-tumor activity of Th17 cells is that IL-17 promotes angiogenesis.491 IL-17 in TME often correlates with high vascular density and tumor overgrowth, and induces the production of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), IL-6 and IL-8 by tumor cells or stromal cells.492,493 Furthermore, Th17 cells and IL-17 indirectly shape a pro-tumor TME by recruiting and influencing other immunosuppressive cells. For instance, IL-17 promotes the development, tumor infiltration and immunosuppressive activity of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs),494,495 TAMs,496–498 and pro-tumor neutrophils.499,500 IL-17 also constrains the cytolytic activity of NK cells and CD8+ T cells by inhibiting IL-15-mediated cell maturation501 and recruiting neutrophils,502 respectively. Interestingly, IL-17 also promotes tumor progression through inducing terminal exhausted CD8+ T cell differentiation.503 Apart from immune cells, IL-17 increases vascular endothelial cells number in gastric cancer,504 triggers CAFs to produce myeloid cell stimulatory factor G-CSF,505 and promotes skin tumor formation by stimulating keratinocyte proliferation.506 Furthermore, Th17 cells secrete high level of IL-22 which enhances the tumor growth and metastasis in human colon cancer.507,508