Abstract

Background

Providing cultural education to health professionals is essential in improving the quality of care and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. This study reports the evaluation of a novel training workshop used as an intervention to improve communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients of persistent pain services.

Methods

In this single-arm intervention study, health professionals undertook a one-day workshop, which included cultural capability and communication skills training based on a clinical yarning framework. The workshop was delivered across three adult persistent pain clinics in Queensland. At the end of the training, participants completed a retrospective pre/post evaluation questionnaire (5 points Likert scale, 1 = very low to 5 = very high), to rate their perceived importance of communication training, their knowledge, ability and confidence to communicate effectively. Participants also rated their satisfaction with the training and suggested improvements for future trainings.

Results

Fifty-seven health professionals were trained (N = 57/111; 51% participation rate), 51 completed an evaluation questionnaire (n = 51/57; 90% response rate). Significant improvements in the perceived importance of communication training, knowledge, ability and confidence to effectively communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients were identified (p < 0.001). The greatest increase was in the perceived confidence pre-training mean of 2.96 (SE = 0.11) to the post-training mean of 4.02 (SE = 0.09).

Conclusion

This patient-centred communication training, delivered through a novel model that combines cultural capability and the clinical yarning framework applied to the pain management setting, was highly acceptable and significantly improved participants’ perceived competence. This method is transferrable to other health system sectors seeking to train their clinical workforce with culturally sensitive communication skills.

Keywords: Communication, Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, health professionals, pain clinics, pain management

Introduction

The ability to communicate effectively with patients, their families, and other health professionals is an essential competency for clinical practice. 1 Ineffective communication between health professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with chronic diseases and other health conditions is a significant barrier to optimal care.2–5

Communication during a clinical consultation requires both a cognitive understanding of the content to be addressed and process skills to explain the required information. Consequently, the ability to integrate these two domains is critical. Interventions aiming to improve clinical communication skills must consider both domains and how these apply to diverse clinical settings. 6

Pain is one of the most common reasons people seek healthcare.7–9 Pain is a significant public health problem, as one in five Australians aged 45 and over are living with persistent pain that causes suffering, reduced quality of life and disability. 10 Aboriginal Australians experience a greater burden of persistent pain compared with non-Indigenous Australians11–13 little is known about the burden of persistent pain among Torres Strait Islander Australians (but is likely to be significant), and therefore persistent pain services need to consider how to address this need. Pain is a complex experience, involving physical, psychological, and social distress with characteristics that are particularly challenging to describe.14,15 As pain is subjective, and the expression of pain can be framed by culture, 16 successful pain management depends upon effective communication for clinicians to understand the multidimensional patient experience. 17 If communication between health professionals and patients is ineffective, uncertainty, doubt, and mutual mistrust can occur, negatively affecting the quality of care received. 18

Communication has been identified as the most significant barrier for Aboriginal people when they seek to manage their musculoskeletal pain. 12 Findings from a recent review 16 demonstrated that in pain management, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients may hold beliefs about the underlying cause of pain which can differ from health professionals. For example, a patient may decide not to share the origins of their pain because they attribute their pain to a consequence of breaking traditional laws and protocols. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients were also found to be reluctant to report their pain when they perceived they were not listened to or were not respected.13,16 Further, given the limited knowledge of health professionals about cultural safety and how they apply this concept during pain assessment within an intercultural context, has the potential to negatively impact pain management and aggravate the suffering among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. 19 Health professionals supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients managing pain therefore require communication skills that are suitable for intercultural interactions, with awareness of the different understandings of and responses to illness.19–21

Ineffective communication may be unrecognized by health professionals, and some health professionals believe that communication skills are inherent or acquired through exposure in the workplace. 22 Evidence demonstrates, however, that communication training of health professionals improves patient experiences and quality of healthcare. Communication training has a positive effect on the communication style of health professionals 23 and influences patient outcomes. 24 Effective communication has been associated with improved rates of patient recovery, more effective pain control, patient adherence to treatment, and improved psychological functioning.23,25

Reviews on the educational methods for improving the communication skills of health professionals have demonstrated that experiential learning methods are the most effective. Effective teaching strategies include role play, simulated learning or supervised practical work.26,27 Pain clinicians have reported that education to improve care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients should include communication skills, relevant clinical examples, and show how to blend biomedical knowledge with cultural approaches to improve clinical practice. Health professionals also suggested that an interactive and motivating format, combining activities such as role play, education, video examples, and individualized feedback and opportunities to apply the learnings would be the preferred format. 28

This study reports outcomes, from the perspective of health professionals working in persistent pain management clinics, of a novel education program combining cultural capability and communication skills based on a clinical yarning approach.

Methods

Study design and framework

This study is part of a multicentre, single-arm interventional feasibility study evaluated using mixed methods, described elsewhere. 29 Briefly, the intervention aims to improve cultural capability and communication between health professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients accessing persistent pain management services in Queensland, Australia. The communication training component was informed by qualitative interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders, and involved adapting a patient-centred communication framework known as clinical yarning, 30 to make this suitable for the Queensland context. For the cultural capability component, this study used the cultural capability definition from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Capability framework in which ‘cultural capability refers to skills, knowledge, and behaviours that are required to plan, support, improve and deliver services in a culturally respectful and appropriate manner’. 31 This project also used experiential and reflective learning approaches to develop the training content and resources aiming to empower participants to identify and challenge the validity of their embedded assumptions and provide the opportunity for interaction in realistic scenarios. 32

The Clinical Yarning training program was delivered across the study sites sequentially, commencing at site 1, followed by site 2 (a month after site 1), and concluding at site 3 (a month after site 2). The evaluation of the effectiveness of the training involved the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data collected from patients and health professionals. This study presents the analysis of the training evaluation data from health professionals.

Study sites and participants recruitment

This study involved three of the five adult persistent pain clinics in Queensland. These clinics are publicly funded, hospital-based and provide a combination of inpatient and outpatient pain management services. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients represent between 4 and 8% of the total number of patients supported by the three clinics.

Participants were health professionals (medical doctors, nursing staff, allied health, and administrative personnel) working in the three persistent pain management services (two metropolitan and one regional service). Local investigators promoted the training among health professionals during team meetings and via email.

The communication training program and resources

The training format involved two components: cultural capability and clinical yarning and was delivered in a single day, over 7 hours, combining education and interactive activities with simulation patients. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders patients were involved in the development of the resources, reviewing and providing feedback through a Consumers Advisory Group and helping to write scripts that were used to develop video vignettes for the training.

For this training four resources were developed: a standard PowerPoint presentation, a facilitator’s manual, a learners’ workbook, and video vignettes demonstrating optimal and suboptimal communication between clinicians and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with pain (please refer to Supplementary Tables S1-S4).

A Torres Strait Islander (JI) senior cultural capability facilitator and research team member led the development of the cultural capability content and the training outline was presented and discussed with the Cultural Capability Network of Queensland Health, which is comprised of cultural capability coordinators and facilitators. The cultural capability component was facilitated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural facilitators. The training session started with the cultural component, in which the cultural facilitator would describe the historical, social, and emotional impact of colonisation. In this part of the training session, the importance of culture, protocols and ways to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were highlighted.

The clinical yarning component was co-facilitated by an experienced pain specialist (MB) and research team member (JI), bringing together clinical and cultural expertise. (MB) was trained in the clinical yarning framework by one of the authors of the clinical yarning framework (IL).

Clinical Yarning is a patient-centred communication framework that re-conceptualizes clinical communication as social, diagnostic and management yarns. 30 Clinical Yarning is a culturally appropriate and patient-friendly approach that promotes trust and better relationships between clinicians and Aboriginal patients. In this component, participants were introduced to the three elements of the clinical yarning framework along with how these can be applied in persistent pain clinics. Participants were encouraged to recall communication experiences with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and identify the communication skills they felt needed to be improved. Next, a video vignettes involving clinicians and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients were presented to participants to identify the elements of the clinical yarning framework and effective communication. The final part of the training involved practising the clinical yarning framework with actors simulating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

The resources developed were relevant to persistent pain management and for the Queensland contexts (Supplementary Tables S1-S4).

Data collection

At the end of the training session, participants were asked to complete a custom-designed questionnaire to evaluate the training. The evaluation questionnaire combined items in three sections to: (1) describe the participants demographic characteristics and previous training; (2) assess the extent to which clinicians perceived communication training to be important, their knowledge of, ability and confidence to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (assessment of communication skills and cultural awareness) and (3) assess satisfaction with training. The items used to assess satisfaction with training were derived from the ‘training satisfaction rating scale’ (Cronbach α coefficient of 0.888) 33 (Supplementary Table 7). 34 The first section included demographic characteristics and location (i.e., study site, profession, age, sex, and Indigenous status), participation in previous cultural training (Yes/No) and types of training received.

In the second section, communication skills and cultural awareness, at one point in time, participants rated pre and post-training their perception of the importance of communication training, their knowledge of, ability and confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very low to 5 = very high).

Satisfaction with training was assessed through twelve questions rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), which evaluated the training objectives and content (Q1–Q3); methods and training context (Q4–Q9); and usefulness and overall rating (Q10–Q12): (1) if the planned objectives were met; (2) if the issues were dealt with in-depth as the length of the course allowed; (3) the length of the course was adequate for the objectives and content; (4) if the method was well suited to the objectives and content; (5) if the method enabled participants to take an active part in the training; (6) if the training enabled the participant to share professional experiences with colleagues; (7) if the training was realistic and practical; (8) if the training context was well suited to the training process; (9) if the training received was useful for their job; (10) if the training received was useful for personal development; (11) if the training merits a good overall rating and (12) if participants would recommend the program to others. In addition, two open-ended questions provided the opportunity for participants to indicate ‘what did you find most useful?’ and ‘how could the program be improved?’

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics, location and previous training. Categorical variables, such as ratings of the perceived importance of communication training for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients; perceived knowledge, ability, confidence and satisfaction with training were summarized using frequencies and percentages for each categorical variable. As the goal of the training was to improve the communication skills of participants, and a change to the highest scores would demonstrate improvements in the perceived importance of communication training, the knowledge of, the ability and confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Participant responses were therefore grouped as ‘highly’ when participants rated statements with scores of 4–5 (high and very high, respectively). The training program was described using mean, standard error (SE) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Change in mean scores of the perceived importance of communication training for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients; perceived knowledge, ability, and confidence between pre and post-training were evaluated with paired samples t-tests. The difference of pre and post-training means between study sites was tested using one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post hoc test was used to identify the study site driving the difference. Statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05. The Cohen’s effect size 35 for the difference between mean scores was calculated as follows

The responses to the open-ended questions were quantified and analysed thematically. 36 Two authors (CMB and KH), an Aboriginal researcher and a non-Indigenous researcher independently read the responses and generated initial codes identifying themes. Next, the identified themes were reviewed and discussed, when disagreements were present, the authors articulated data from relevant literature and discussed the implications of the directions of the findings. A summary was provided to the research team for critical review and questioning until consensus was reached. Findings were presented as frequencies and further illustrated with quotes.

Results

Participants’ demographic characteristics and previous cultural training

Of the 111 health professionals working across the three clinics at the time of the training, 57 participated in the training (51% participation rate) and 51 of them completed a training evaluation questionnaire (90% response rate). In total 77% of participants were female, with an average age of 39 years (SD = 9.69) and 98% were of non-Indigenous background. Almost a third of participants were medical doctors (29%) and three-quarters of all participants reported having attended previous cultural training (75%). The most frequent training types reported were the mandatory cultural awareness training provided by Queensland Health (55%), and training during university studies (29%) Table 1.

Table 1.

Health professionals’ demographic characteristics and previous training.

| Demographic characteristics and previous training | N = 51 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Study site | ||

| Metropolitan (A) | 13 | 26 |

| Regional | 24 | 47 |

| Metropolitan (B) | 14 | 28 |

| Age a | ||

| 21–40 years | 33 | 65 |

| 41–60 years | 11 | 22 |

| 61–80 years | 3 | 6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 | 24 |

| Female | 39 | 77 |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 1 | 2 |

| Non-indigenous | 50 | 98 |

| Profession | ||

| Medical doctors (pain medicine specialist, registrar and psychiatrist) | 15 | 29 |

| Nursing staff (registered nurse, clinical nurse, nurse navigator, enrolled nurse) | 13 | 26 |

| Physiotherapist | 6 | 12 |

| Psychologist | 6 | 12 |

| Pharmacist | 2 | 4 |

| Occupational therapist | 6 | 12 |

| Administrative staff | 3 | 6 |

| Previous cultural training | ||

| Yes | 38 | 75 |

| No | 13 | 26 |

| If previous cultural training—type of training b | ||

| Hospital based mandatory cultural awareness training/education packages | 23 | 55 |

| Cultural capability and safety lectures during university studies | 12 | 29 |

| Primary school cultural awareness training | 1 | 2 |

| Training for foster care | 1 | 2 |

| Not specified/unknown | 5 | 12 |

aFour missing values.

bParticipants could indicate more than one option of training.

Training evaluation ratings

As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, there was an increase in the proportion of clinicians rating higher scores after the training, and with significant increases in the mean scores for the four items measured. The perceived importance of communication training increased from pre-training (Mean = 4.18; 95% CI = 3.91–4.44) to post-training (Mean = 4.69; 95% CI = 4.52–4.85) (p < 0.001). There were also significant improvements of reported by health professionals in their knowledge (pre-training Mean = 2.94; 95% CI = 2.74–3.14), ability (pre-training Mean = 2.96; 95% CI = 2.79–3.13) and confidence (pre-training Mean = 2.96; 95% CI = 2.75–3.17) compared to post-training (Mean = 3.98; 95% CI = 3.81–4.15; Mean = 3.96; 95% CI = 3.80–4.12; Mean = 4.02; 95% CI = 3.85–4.19, respectively) (p < 0.001). The most marked increase was health professionals’ perceived confidence (Table 3).

Table 2.

Proportion of clinicians according to pre- and post-training ratings.

| Pre-Training | Post-Training | |||||||||||||||||||

| Scores | Very low (1) | Low (2) | Moderate (3) | High (4) | Very high (5) | Very low (1) | Low (2) | Moderate (3) | High (4) | Very high (5) | ||||||||||

| Items | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Importance | — | — | 2 | (4) | 12 | (24) | 12 | (24) | 25 | (49) | — | — | — | — | 3 | (6) | 10 | (20) | 38 | (75) |

| Knowledge | 1 | (2) | 11 | (22) | 29 | (57) | 10 | (20) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 10 | (20) | 32 | (63) | 9 | (18) |

| Ability | — | — | 10 | (20) | 33 | (65) | 8 | (16) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 9 | (18) | 35 | (69) | 7 | (14) |

| Confidence | 2 | (4) | 9 | (18) | 29 | (57) | 11 | (22) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 9 | (18) | 32 | (63) | 10 | (20) |

Table 3.

Comparison between pre and post-training rating mean (SE) of perceived importance, knowledge, ability and confidence to communicate (N = 51).

| Items | Pre-Training | Post-Training | Difference between means | (SE.) | Cohen’s D effect size | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SE.) | (95% CI) | Mean | (SE.) | (95% CI) | |||||

| Importance | 4.18 | (0.13) | (3.91–4.44) | 4.69 | (0.08) | (4.52–4.85) | 0.51 | 0.09 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Knowledge | 2.94 | (0.10) | (2.74–3.14) | 3.98 | (0.09) | (3.81–4.15) | 1.03 | 0.09 | 1.57 | <0.001 |

| Ability | 2.96 | (0.08) | (2.79–3.13) | 3.96 | (0.08) | (3.80–4.12) | 1.00 | 0.07 | 1.72 | <0.001 |

| Confidence | 2.96 | (0.11) | (2.75–3.17) | 4.02 | (0.09) | (3.85–4.19) | 1.05 | 0.08 | 1.55 | <0.001 |

*Paired-samples t-test, df = 50.

Training evaluation and demographic characteristics

Following training, fewer younger health professionals (≤40 years) highly rated their perceived importance of communication training (91% vs. 100%), and their perceived knowledge (76% vs. 86%), and ability (79% vs. 86%) to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared to health professionals aged ≥41 years. In turn, younger health professionals more frequently highly rated their confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (85% vs. 71%) (Table 4). A higher proportion of male health professionals highly rated their perceived importance of communication training (100% vs. 92%), their perceived knowledge (92% vs. 77%), and confidence (92% vs. 80%) to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared to female health professionals.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics and previous training of health professionals who rated high or very high (scores 4–5) the perceived importance for training, knowledge, ability and confidence to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

| Demographic characteristics and previous training | n | Importance of training | Knowledge of how effectively to communicate | Ability to communicate | Confidence to communicate | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Training | Post-Training | Pre-Training | Post-Training | Pre-Training | Post-Training | Pre-Training | Post-Training | ||||||||||

| Study site | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Metropolitan A | 13 | 8 | (62) | 10 | (77) | 4 | (31) | 10 | (77) | 2 | (15) | 10 | (77) | 3 | (23) | 9 | (69) |

| Regional B | 24 | 19 | (79) | 24 | (100) | 3 | (13) | 21 | (88) | 3 | (13) | 22 | (92) | 4 | (17) | 22 | (92) |

| Metropolitan C | 14 | 10 | (71) | 14 | (100) | 3 | (21) | 10 | (71) | 3 | (21) | 10 | (71) | 4 | (29) | 11 | (82) |

| Age a | |||||||||||||||||

| 21–40 years | 33 | 22 | (67) | 30 | (91) | 7 | (21) | 25 | (76) | 7 | (21) | 26 | (79) | 8 | (24) | 28 | (85) |

| 41–60 years | 11 | 8 | (73) | 11 | (100) | 1 | (9) | 9 | (82) | 0 | (0) | 9 | (82) | 2 | (18) | 7 | (64) |

| 61–80 years | 3 | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 1 | (33) | 3 | (100) | 1 | (33) | 3 | (100) | 1 | (33) | 3 | (100) |

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 12 | 10 | (83) | 12 | (100) | 3 | (25) | 11 | (92) | 3 | (25) | 10 | (83) | 5 | (42) | 11 | (92) |

| Female | 39 | 27 | (69) | 36 | (92) | 7 | (18) | 30 | (77) | 5 | (13) | 32 | (82) | 6 | (15) | 31 | (80) |

| Indigenous status | |||||||||||||||||

| Indigenous | 1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) |

| Non-Indigenous | 50 | 37 | (74) | 48 | (96) | 9 | (18) | 40 | (80) | 7 | (14) | 41 | (82) | 10 | (20) | 41 | (82) |

| Profession | |||||||||||||||||

| Medical doctors | 15 | 10 | (67) | 14 | (93) | 4 | (27) | 12 | (80) | 3 | (20) | 14 | (93) | 5 | (33) | 14 | (93) |

| Nursing staff | 13 | 10 | (77) | 13 | (100) | 3 | (23) | 11 | (85) | 2 | (15) | 11 | (85) | 3 | (23) | 11 | (85) |

| Physiotherapist | 6 | 3 | (50) | 5 | (83) | 1 | (17) | 4 | (67) | 1 | (17) | 4 | (67) | 1 | (17) | 5 | (83) |

| Psychologist | 6 | 5 | (83) | 5 | (83) | 1 | (17) | 4 | (67) | 2 | (33) | 3 | (50) | 2 | (33) | 5 | (83) |

| Pharmacist | 2 | 1 | (50) | 2 | (100) | 1 | (50) | 2 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (50) |

| Occupational T | 6 | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 5 | (83) | 0 | (0) | 5 | (83) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (50) |

| Administrative | 3 | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (100) |

| Previous cultural training | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 38 | 29 | (76) | 35 | (100) | 8 | (21) | 31 | (82) | 7 | (18) | 33 | (87) | 10 | (26) | 32 | (84) |

| No | 13 | 8 | (61) | 13 | (92) | 2 | (15) | 10 | (77) | 1 | (8) | 9 | (69) | 1 | (8) | 10 | (77) |

aFour missing value.

Medical doctors highly rated their ability and confidence to communicate (93% vs. 85%) more frequently than nursing staff. However, nursing staff highly rated the perceived importance of communication training (100% vs. 93%) and their perceived knowledge (85% vs. 80%) more often than medical doctors. In comparison to other health professionals, a lower proportion of psychologists and physiotherapists highly rated their perceived importance of communication training (83% for both groups), perceived knowledge (67% for both groups) and ability (50% and 67%, respectively) to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Health professionals who had received previous cultural training gave higher ratings across all four items: the perceived importance of training (100% vs. 92%), their perceived knowledge (82% vs. 77%), ability (87% vs. 69%) and confidence (84% vs. 77%).

Training evaluation by study site

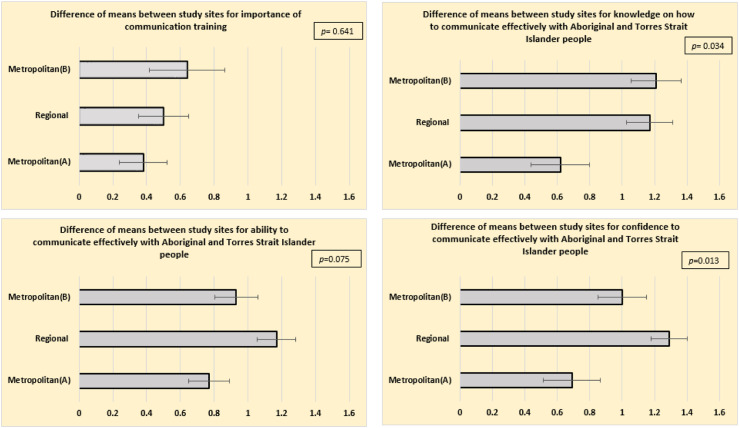

Comparing study sites, the mean scores were similar for perceived importance of communication (F(2,48) = 0.448; p = 0.641) and perceived ability (F(2,48) = 3.645; p = 0.075) (Figure 1). However, study sites differed in relation to pre-post training improvements of perceived knowledge (F(2,48) = 2.731; p = 0.034) and confidence (F(2,48) = 4.724; p = 0.013). A Tukey post hoc test showed that the metropolitan site (B) and the regional site had similar increases in knowledge (1.21 and 1.17 respectively; p = 0.975). However, when comparing the perceived knowledge of Metropolitan site (A) to the Regional site there was a smaller increase (0.62; p = 0.048). The regional site reported a significant increase in mean score for confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (1.29) compared to metropolitan site A (0.69; p = 0.010) but not for Metropolitan site B (1.0; p = 0.293).

Figure 1.

Difference between scores pre and post-training by study sites using univariate analysis of variance.

Satisfaction with training and suggested program improvements

Assessment of satisfaction with training through quantitative data

Overall, of the 12 items about training satisfaction, a high proportion of health professionals (range 94%–100%) (Table 5 and Supplementary Table 5) either agreed or strongly agreed that the training met the objectives, that issues were dealt with in depth; the course length was adequate; the training methods suited the objectives, the methods enabled participants to take an active part in the training, the training enabled sharing of professional experiences, the training was a realist and practical, the training context was well suited to the training process the training received was useful for participants’ jobs, the training was useful for the professional development, the training merited a good overall rating, and that participants would recommend the program to others. The item with the highest proportion of undecided participants was the ‘length of the course was adequate’ (n = 3; 6%) and the only item for which a participant disagreed with the statement was ‘I would recommend this program to others’ (n = 1; 2%).

Table 5.

Demographic characteristics and previous training of health professionals who agreed or strongly agreed (scores 4–5) with the statements about their satisfaction with CY training.

| Demographic characteristics and previous training | Objectives were met | Issues were dealt with depth | Course length was adequate | The method was well suited | Method-enabled active participation in the training | Training-enabled sharing professional experiences a | Training was realist and practical | Training context was well suited to the training process | Training received is useful for my job a | Training received is useful for personal development | Training merits overall good rating | I would recommend this program to others | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study site | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Metropolitan (A) | 12 | (92) | 13 | (100) | 12 | (92) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 12 | (92) | 13 | (100) | 11 | (85) | 12 | (92) | 13 | (100) | 12 | (92) |

| Regional (B) | 24 | (100) | 24 | (100) | 22 | (92) | 24 | (100) | 24 | (100) | 22 | (96) | 23 | (96) | 24 | (100) | 23 | (100) | 23 | (96) | 24 | (100) | 24 | (100) |

| Metropolitan (C) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 13 | (93) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) | 14 | (100) |

| Age b | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21–40 years | 32 | (97) | 33 | (100) | 31 | (94) | 33 | (100) | 33 | (100) | 32 | (100) | 33 | (97) | 33 | (100) | 30 | (94) | 32 | (97) | 33 | (100) | 32 | (97) |

| 41–60 years | 11 | (100) | 11 | (100) | 10 | (91) | 11 | (100) | 11 | (100) | 9 | (82) | 11 | (100) | 11 | (100) | 11 | (100) | 10 | (91) | 11 | (100) | 11 | (100) |

| 61–80 years | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 12 | (100) |

| Female | 38 | (97) | 39 | (100) | 36 | (92) | 39 | (100) | 39 | (100) | 36 | (95) | 37 | (95) | 39 | (100) | 36 | (95) | 37 | (95) | 39 | (100) | 38 | (97) |

| Indigenous status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indigenous | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 1 | (100) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (100) | 0 | (0) |

| Non-Indigenous | 49 | (98) | 50 | (100) | 47 | (94) | 50 | (100) | 50 | (100) | 47 | (96) | 48 | (96) | 50 | (100) | 48 | (98) | 49 | (98) | 50 | (100) | 50 | (100) |

| Profession | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medical doctors | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) | 15 | (100) |

| Nursing staff | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 12 | (92) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 12 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) |

| Physiotherapist | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) |

| Psychologist | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) |

| Pharmacist | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (100) |

| Occupational T | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 5 | (83) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) | 6 | (100) |

| Administrative | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 2 | (67) | 2 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 1 | (50) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) | 2 | (100) | 2 | (67) | 3 | (100) | 3 | (100) |

| Previous cultural training | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 37 | (97) | 38 | (100) | 35 | (92) | 38 | (100) | 38 | (100) | 35 | (95) | 36 | (95) | 38 | (100) | 35 | (95) | 36 | (95) | 38 | (100) | 37 | (97) |

| No | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) |

Training enabled sharing professional experiences’ and ‘Training received was useful to my job’ had.

aMissing value for the following characteristics: study site, sex, Indigenous status, profession and previous training.

bWithin age group all the items had 4 missing values; except, ‘Training enabled sharing professional experiences’ and study site and ‘Training received was useful to my job’ had 5 missing values.

Among the professions, a lower proportion of administrative staff either agreed or strongly agreed that the length of the training was adequate and that the training received was useful for their job (67%) compared to the other professions (83–100%). Only half of the administrative staff either agreed or strongly agreed that the training enabled sharing professional experiences compared to 83–100% among the other professions.

Assessment of satisfaction with training through qualitative data

Forty-two health professionals (n = 42/51; 82%) responded to the open-ended questions indicating the most useful aspects of the training. Four themes were identified from the responses (Supplementary Table 6 – Quotes to illustrate the themes identified):

(i) Sharing of historical and cultural knowledge

Half of all participants reported that the historical and cultural knowledge shared by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural facilitators (n = 21; 50%) was the most useful aspect of the training. These facilitators provided insightful information about the impact of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and well-being. Health professionals reported being able to reflect on the feelings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, especially in approaching government institutions, including healthcare and communicating with non-Indigenous staff.

(ii) Interactive simulation of case scenarios with feedback provided by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander simulation patients

The interactive module with role-playing patients and with feedback provided by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander simulation patients was rated the most useful aspect by 16 participants (38%). Participants reported particularly valuing feedback and interpretation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, verbal and non-verbal cues, and helping to contextualise the information provided. These elements were described as unique opportunities afforded by this training.

(iii) The framework and communication content

The Clinical Yarning framework and the communication content was rated as the most useful aspects by 9 participants (21%). These participants reported that it was important to learn how the different components of the framework could be applied. For example, participants highlighted the usefulness of the explanation about social yarning which was viewed as crucial to building rapport with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

(iv) Pain specific scenarios and having experienced facilitators

Three participants (7%) rated pain-specific cases and the experienced facilitators as the most useful aspect. These participants highlighted how they felt engaged throughout the training day. They reported that they could relate to the simulated patients in the pain setting and the questions arisen were answered and discussed having the input of an experienced pain specialist and supported by the cultural facilitator.

Eleven participants (22%) suggested improvements to the training program by extending the training time (n = 3; 27%); including follow-up and feedback (clinicians and patients) to enable problem-solving and consolidate lessons learned (n = 3; 27%); adopting a stronger focus on the management yarning, more content about the local history including people from inland as well as coastal areas (n = 3; 27%) and more opportunities for yarning and group discussions (n = 2; 18%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a communication skills training program that combines cultural capability and a clinical yarning framework and contextualises these to the persistent pain setting. Ensuring cultural sensitive staff and suitable communication skills are essential to provide optimal care. 37

The findings of this study indicate that the training improved participants’ perceptions about the importance of communication training, and their perceived knowledge, ability, and confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Particularly relevant to the communication between health professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients was the significant increase in participants’ perceived confidence. While the findings of improvements in perceived knowledge, ability, and confidence after communication skills training are not unique to this study, these findings are relevant because evidence suggests that achieving improvements across all three of these domains is required for change in practice. 38 According to Bandura, 39 it is not enough for individuals to possess knowledge and skills to perform a task, they must also believe they can successfully perform that task, even in challenging circumstances. 40 The current study finds the training meets these criteria.

Another important contribution of this study is the strong endorsement of the experiential and reflective learning approaches adopted in the training. This is consistent with the principles of Adult Learning Theory that underpin continuing professional development training. 32 The experiential component was contextualized to the clinical setting of pain management and promoted the interaction of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander simulation patients and clinicians, creating the opportunity for self-reflection through the feedback from simulation patients.

Health professionals have an important role in influencing patient experiences.41,42 In this study, medical doctors perceived their ability and confidence to communicate effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people more highly than the other health professionals. In contrast, nursing staff perceived the importance of training and knowledge as high but indicate lower ability and confidence. These results may demonstrate the efforts of medical schools to introduce interviewing techniques and communication skills training in school curricula.43,44 Alternatively, it could reflect an overestimation by doctors of their ability to communicate effectively with these patient groups. Gude et al. 45 demonstrated that medical students and young physicians did not realistically and reliably assess their self-efficacy regarding communication skills. It was found that there was a significant discrepancy between self-rated communication ability and the communication experts’ ratings. 45 Furthermore, the differences across professional groups may suggest that it is important to consider disciplinary norms and needs when planning communication training. Academic disciplines are communities with their language, norms, and values. Each discipline develops a disciplinary communication competence so that its members share a common understanding of appropriate ways of communicating and behaving and enabling the interaction between members of the disciplinary culture effectively. 46

From the qualitative evaluation, participants identified the need for more cultural local knowledge and understanding of the different language protocols used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Health professionals appreciated the opportunity to interrogate cultural questions, in a safe setting and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people providing feedback to them. The training session was considered very informative and health professionals suggested further training with a greater focus on the language and terminology used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to describe and express pain.

Refresher sessions integrated in the professional development program of services and the collection of metrics about the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients’ experience of communication as part of quality improvements could be potential opportunities to consolidate the learnings of this training.

Further work is needed to understand how this training is embedded in practice and what impact this has on patient care and outcomes.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size of clinicians involved in the training, a custom-designed questionnaire that used self-reported measures of knowledge, ability, and confidence. The Metropolitan site A was the first site to receive the training and this perhaps has affected the delivery of training and the reported improvements. While three of the five persistent pain services in Queensland were included in the study, not all professional categories were represented (e.g. addiction medicine specialists and General Practitioners). Although this study indicates that training participants developed the perceived knowledge, ability and confidence to effectively communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, the longitudinal impact of this one-day workshop in terms of applying in clinical practice remains unclear and further research is needed to understand how this training is translated into practice. A future publication will outline changes in clinical consultations recorded pre- and post this training program.

Conclusion

This patient-centred communication training, delivered through a novel model that combines cultural capability and the clinical yarning framework applied to the pain management setting, was highly acceptable and significantly improved participants’ perceived competence. The training provided an opportunity for health professionals to reflect on their intercultural communication practice stimulated by theoretical elements of the clinical yarning framework and interaction with simulated patients and cultural feedback. The impact of the training in clinical practice is still to be demonstrated and reinforcement of the learnings was suggested by participants. This method is transferrable to other health system sectors seeking to train their clinical workforce with culturally sensitive communication skills.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Yarning about pain: Evaluating communication training for health professionals at persistent pain services in Queensland, Australia by Christina M Bernardes, Stuart Ekberg, Stephen Birch, Andrew Claus, Matthew Bryant, Renata Meuter, Jermaine Isua, Paul Gray, Joseph P Kluver, Eva Malacova, Corey Jones, Kushla Houkamau, Marayah Taylor, Ivan Lin and Gregory Pratt in British Journal of Pain

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the clinicians and the Indigenous Liaison Hospital Officers from the three study sites who were essential for the conduct of this study.

Author contributions: GP, CMB, SE, SB, RM, MB, JI, PG, JPK, IL: conceptualization. CMB, KH, CJ, AC, PG, JPK, MB, MT: data collection. CMB, SE, SB, RM, GP, AC, EM, IL: formal analysis. CMB, GP, SE, SB, RM, MB, JI, PG, JPK, IL, KH: methodology. CMB, SE, SB, RM, IL, AC, GP: writing original draft. CMB, SE, SB, RM, MB, JI, PG, JPK, IL, GP, EM: writing review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by a Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee - the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee—reference number 63949, and by respective ethics committees of the study sites (Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee and Metro South Health Service District Human Research Ethics Committee). This work was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Medical Research Future Funding under the grant number MRF 9100000.

Informed consent: Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Data availability: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Christina M Bernardes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8061-7013

References

- 1.Du XY, Abu-Hijleh MF, Hamdy H, et al. Identifying essential competencies for medical students. J Appl Res High Educ 2019; 11(3): 352–366. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, et al. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for aboriginal and torres strait islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowell A, Maypilama E, Yikaniwuy S, et al. “Hiding the story”: indigenous consumer concerns about communication related to chronic disease in one remote region of Australia. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2012; 14(3): 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan-Isles D, Macniven R, Hunter K, et al. Enablers and barriers to accessing healthcare services for aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(6): 3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahid S, Durey A, Bessarab D, et al. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: the perspective of service providers. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKivett A, Paul D, Hudson N. Developing a practical framework for clinical communication between aboriginal communities and healthcare practitioners. J of Immigr and Minor Health 2018; 21: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emilson C, Asenlof P, Demmelmaier I, et al. Association between health care utilization and musculoskeletal pain. A 21-year follow-up of a population cohort. Scand J Pain 2020; 20(3): 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham LA, Wagner TH, Richman JS, et al. Exploring trajectories of health care utilization before and after surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2019; 228(1): 116–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieber K, Stamm TA, Hoffmann K, et al. Synergistic effect of pain and deficits in ADL towards general practitioner visits. Fam Pract 2015; 32(4): 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Chronic Pain in Australia. Cat no. PHE 267. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin I, Coffin J, Bullen J, et al. Opportunities and challenges for physical rehabilitation with indigenous populations. Pain Rep 2020; 5(5): e838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin IB, Bunzli S, Mak DB, et al. Unmet needs of aboriginal Australians with musculoskeletal pain: a mixed-method systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018; 70(9): 1335–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strong J, Nielsen M, Williams M, et al. Quiet about pain: experiences of aboriginal people in two rural communities. Aust J Rural Health 2015; 23(3): 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig KD. The social communication model of pain. Can Psychol 2009; 50(1): 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeser JD, Melzack R. Pain: an overview. Lancet 1999; 353(9164): 1607–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arthur L, Rolan P. A systematic review of western medicine’s understanding of pain experience, expression, assessment, and management for Australian aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples. Pain Rep 2019; 4(6): e764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry SG, Matthias MS. Patient-Clinician communication about pain: a conceptual model and narrative review. Pain Med 2018; 19: 2154–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esquibel AY, Borkan J. Doctors and patients in pain: conflict and collaboration in opioid prescription in primary care. Pain 2014; 155(12): 2575–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenwick C. Assessing pain across the cultural gap: central Australian indigenous peoples’ pain assessment. Contemp Nurse 2006; 22(2): 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durey A, Hill P, Arkles R, et al. Overseas-trained doctors in indigenous rural health services: negotiating professional relationships across cultural domains. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008; 32(6): 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durey A, Thompson SC, Wood M. Time to bring down the twin towers in poor aboriginal hospital care: addressing institutional racism and misunderstandings in communication. Intern Med J 2012; 42(1): 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Back AL, Fromme EK, Meier DE. Training clinicians with communication skills needed to match medical treatments to patient values. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67(S2): S435–S441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo-Soto GA, et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 7: CD003751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Street RL, Jr., Makoul G, Arora NK, et al. How does communication heal? pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74(3): 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-Patient communication: a review. Ochsner J 2010; 10(1): 38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bos-van den Hoek DW, Visser LNC, Brown RF, et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals in oncology over the past decade: a systematic review of reviews. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2019; 13(1): 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggenberger E, Heimerl K, Bennett MI. Communication skills training in dementia care: a systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25(3): 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardes CM, Ekberg S, Birch S, et al. Clinician perspectives of communication with aboriginal and torres strait islanders managing pain: needs and preferences. Int J Environ Res and Public Health 2022; 19: 1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernardes CM, Lin E, Birch S, et al. Study protocol: clinical yarning, a communication training program for clinicians supporting aboriginal and torres strait islander patients with persistent pain: a multicentre intervention feasibility study using mixed methods. Public Health in Pract 2022; 3(100221): 100221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin I, Green C, Bessarab D. Yarn with me’: applying clinical yarning to improve clinician-patient communication in aboriginal health care. Aust J Prim Health 2016; 22(5): 377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Queensland Health . Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Capability Framework 2010 – 2033, 2010, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/156200/cultural_capability.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukhalalati BA, Taylor A. Adult learning theories in context: a quick guide for healthcare professional educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2019; 6: 2382120519840332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tello FPH, Moscoso SC, García IB, et al. Training satisfaction rating scale: development of a measurement model using polychoric correlations. Eur J Psychol Assess 2006; 22(4): 268–279. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pratt CC, McGuigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Evaluation 2000; 21(3): 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunst CJ, Hamby DW. Guide for calculating and interpreting effect sizes and confidence intervals in intellectual and developmental disability research studies. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2012; 37(2): 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire M, Dalahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHEJ 2017; 9(3), http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerrigan V, Lewis N, Cass A, et al. “How can I do more?” cultural awareness training for hospital-based healthcare providers working with high aboriginal caseload. BMC Med Educ 2020; 20(1): 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer F, Helmer S, Rogge A, et al. Outcomes and outcome measures used in evaluation of communication training in oncology - a systematic literature review, an expert workshop, and recommendations for future research. BMC Cancer 2019; 19(1): 808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84(2): 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Artino AR, Jr. Academic self-efficacy: from educational theory to instructional practice. Perspect Med Educ 2012; 1(2): 76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy DM, Fasolino JP, Gullen DJ. Improving the patient experience through provider communication skills building. Patient Exp J 2014; 1(1): 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naughton CA. Patient-Centered communication. Pharmacy (Basel) 2018; 6(1): 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berman AC, Chutka DS. Assessing effective physician-patient communication skills: “Are you listening to me, doc?” Korean J Med Educ 2016; 28(2): 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ranjan P, Kumari A, Chakrawarty A. How can doctors improve their communication skills? J Clin Diagn Res 2015; 9(3): JE01–JE04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gude T, Finset A, Anvik T, et al. Do medical students and young physicians assess reliably their self-efficacy regarding communication skills? a prospective study from end of medical school until end of internship. BMC Med Educ 2017; 17(1): 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dimitrov N. Disciplinary communication competence among teaching assistants: a research Agenda. Centre for Teaching and Learning Publications, 2012; 4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Yarning about pain: Evaluating communication training for health professionals at persistent pain services in Queensland, Australia by Christina M Bernardes, Stuart Ekberg, Stephen Birch, Andrew Claus, Matthew Bryant, Renata Meuter, Jermaine Isua, Paul Gray, Joseph P Kluver, Eva Malacova, Corey Jones, Kushla Houkamau, Marayah Taylor, Ivan Lin and Gregory Pratt in British Journal of Pain