Keywords: genetics and development, kidney development, obstructive uropathy, pediatric nephrology, genetic renal disease, DNA copy number variations, nucleotides

Abstract

Significance Statement

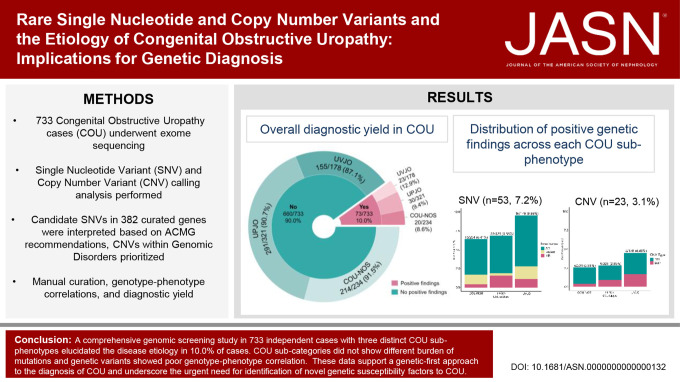

Congenital obstructive uropathy (COU) is a prevalent human developmental defect with highly heterogeneous clinical presentations and outcomes. Genetics may refine diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, but the genomic architecture of COU is largely unknown. Comprehensive genomic screening study of 733 cases with three distinct COU subphenotypes revealed disease etiology in 10.0% of them. We detected no significant differences in the overall diagnostic yield among COU subphenotypes, with characteristic variable expressivity of several mutant genes. Our findings therefore may legitimize a genetic first diagnostic approach for COU, especially when burdening clinical and imaging characterization is not complete or available.

Background

Congenital obstructive uropathy (COU) is a common cause of developmental defects of the urinary tract, with heterogeneous clinical presentation and outcome. Genetic analysis has the potential to elucidate the underlying diagnosis and help risk stratification.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive genomic screen of 733 independent COU cases, which consisted of individuals with ureteropelvic junction obstruction (n=321), ureterovesical junction obstruction/congenital megaureter (n=178), and COU not otherwise specified (COU-NOS; n=234).

Results

We identified pathogenic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in 53 (7.2%) cases and genomic disorders (GDs) in 23 (3.1%) cases. We detected no significant differences in the overall diagnostic yield between COU sub-phenotypes, and pathogenic SNVs in several genes were associated to any of the three categories. Hence, although COU may appear phenotypically heterogeneous, COU phenotypes are likely to share common molecular bases. On the other hand, mutations in TNXB were more often identified in COU-NOS cases, demonstrating the diagnostic challenge in discriminating COU from hydronephrosis secondary to vesicoureteral reflux, particularly when diagnostic imaging is incomplete. Pathogenic SNVs in only six genes were found in more than one individual, supporting high genetic heterogeneity. Finally, convergence between data on SNVs and GDs suggest MYH11 as a dosage-sensitive gene possibly correlating with severity of COU.

Conclusions

We established a genomic diagnosis in 10.0% of COU individuals. The findings underscore the urgent need to identify novel genetic susceptibility factors to COU to better define the natural history of the remaining 90% of cases without a molecular diagnosis.

Introduction

Obstructive uropathy is caused by structural or functional defects of the urinary tract that constrain urinary flow from the kidneys to the bladder.1,2 Congenital hydronephrosis is the main presenting indicator for urinary tract obstruction, which is diagnosed in 2–29 cases per 10,000 live births.3 Because hydronephrosis if clinically silent in most cases and neonates and children do not undergo screening by imaging studies, this incidence is vastly underestimated. In humans, kidney and urinary tract development starts at the fifth gestational week, when protrusion of the ureteric bud into the metanephric mesenchyme enables the formation of a patent ureter and fetal urinary flow from the metanephros to the embryonic bladder.4,5 At the same time, the bladder and the urethra are formed from the urogenital sinus.6,7 Unilateral or bilateral perturbations in these tightly regulated processes may therefore affect every level of the kidney and urinary tract, resulting in obstructive uropathy categorized into four main phenotypic groups based on their anatomical localization: (1) ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO), (2) ureterovesical junction obstruction (UVJO) leading to a (nonrefluxing) megaureter, (3) dysfunction of the bladder, e.g., caused by either neurogenic (e.g., spina bifida) or non-neurogenic causes, and (4) lower urinary outflow tract obstruction caused by posterior urethral valves (PUVs), urethral atresia, or prolapsing ureterocele.8,9 Based on a clinical perspective, UPJO and UVJO are often considered as congenital obstructive uropathy (COU) phenotypes, whereas bladder dysfunction and PUV are conditions stratified under lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO). Depending on their severity and/or co-occurrence of other perturbations in development, all the above mentioned diagnoses can lead to significant morbidity and mortality after birth10–12 and the potential requirement for early surgical interventions to prevent progression of kidney failure.13

Genetics has the potential to aid in the ascertainment of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of patients with COU.2,14 However, despite the fact that COU is a common human developmental defect, its molecular etiology remains largely elusive.15 Notwithstanding a clear familial occurrence for COU phenotypes, genetic discoveries of monogenic causes or copy number variants (CNVs, i.e., large deletions or duplications within the genome) lag behind when compared with other congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) such as kidney hypodysplasia (KHD).14,16,17 One major explanation is that relatively small and heterogeneous cohorts of individuals with COU have been subjected to genetic testing until now.2,14,18 Nevertheless, our current genetic knowledge for COU shows strong overlap with other CAKUT phenotypes because Mendelian forms caused by rare pathogenic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or genomic disorders (GDs) caused by pathogenic CNVs have both been identified in individuals with COU and congenital KHD.16,17,19,20 As such, this hallmark of variable expressivity within the complex etiology of CAKUT may hamper our ability to ascertain risk and prognosis, thus resulting in suboptimal clinical management and genetic counseling of patients.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the genetic etiology of upper urinary tract obstruction by performing a large clinical genomic screen of individuals with UPJO, UVJO, and COU not otherwise specified (COU-NOS), by using a combined approach of exome sequencing (ES) for SNVs and copy number variation (CNV) analysis. Given the common embryonic background of a disturbed outgrowth of the ureteric bud, we hypothesize that the genetic backgrounds of COU subcategories display strong molecular overlap.

Methods

Study Participants

The study involving human participants was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants and/or guardians provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the local ethics committees of participating recruitment sites.

The COU study participants consisted of 733 unrelated and affected individuals recruited from 24 participating sites in seven countries, Italy (n=296), Poland (n=204), Macedonia (n=118), the United States (n=61), Croatia (n=47), the Netherlands (n=4), and Turkey (n=3). Diagnosis was based on the ICD-10 code provided by the recruiting physician. The inclusion criteria included individuals who have been clinically ascertained for UPJO, UVJO, or COU-NOS. Individuals with a primary hierarchical diagnosis of other CAKUT phenotypes including kidney anomaly, duplicated collecting system, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), horseshoe kidney/ectopic kidney, and LUTO/PUV, in isolation or in addition to COU were excluded and individuals with neurogenic obstructive uropathy (e.g., spina bifida) or non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder. Twenty one thousand four hundred and ninety eight population controls with available DNA microarray data described in our prior publication were used for comparisons of CNV frequencies.16,17,19–22 An in-house 11,818 multiethnic population controls dataset from the Institute for Genomic Medicine (IGM) was used for allelic frequency estimation of our prioritized SNVs.23

ES and Variant and Base Calling

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood according to standard protocols. Proband-only ES was performed at three sequencing facilities using either the Illumina Hiseq2500 sequencing platform (Yale Mendelian Genomics Center, YMGC; Columbia IGM) or the Illumina HiseqX10 sequencing platform (New York Genome Center), on the following capture kits: Integrated DNA Technologies Exome Enrichment Panel, Agilent V4, and Roche NimbleGen SeqCap Exome EX v3.0. The DRAGEN v3 platform was used to map sequenced reads to the reference genome (hs37d5.fa, Ensembl-GRCh37.73). Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) 3.6 was subsequently used for base quality recalibration, indel realignment, and variant calling. ClinEff was used for variant annotation with Ensembl (version GRCh38), EVS-v.0.0.30, ExAC 0.3,24 gnomAD Exome and gnomAD Genome version 2.1,25 dbNSFP 4.1a, Human Gene Mutation Database 2021.4, Clinvar 2022-01-10,26 American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) v3, and Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner 2016-06-03. Resulting variant calls, sample-level site coverage data, and annotations were stored in the Analysis Tool for Annotated Variants (ATAV) centralized database and queried.23

Variant-Level Quality Control and Prioritization

We first used a manually curated list of 625 nephropathy-associated genes,27 from which we further prioritized 382 genes that, when mutated, are known to cause Mendelian forms of isolated or syndromic CAKUT (Supplemental Table 1).

Variant-level data from the 733 COU individuals within the 382 prioritized genes were queried using the variant annotation function implemented in the ATAV,23 the analysis variant engine that powers our exome–genome sequencing warehouse (Supplemental Figure 1). Variant filtering was performed to require a quality score >50, quality by depth score ≥2, genotyping quality score ≥20, mapping quality score ≥40, and coverage ≥10; alternate read percentages was within the range of 0.3 and 0.7 for heterozygous genotypes. To further ensure the removal of sequencing artifacts, variants that occurred ≥20 within the COU cohort and variants that seemed ≥500 within the internal ATAV controls cohort were removed. For variant prioritization, we used the Diagnosticator (https://diagnosticator.com) and Varsome (https://varsome.com/) web-based platforms that implement the ACMG guidelines28 as a first-pass screen to predict an ACMG verdict for each uploaded variant for further clinical variant interpretation and genotype–phenotype correlation for all 382 genes. We used the following criteria to define a positive genetic finding for our clinical research variant adjudication. First-tier positive findings were considered if the genotype was already reported as pathogenic or likely pathogenic in ClinVar26 or classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic by strict ACMG criteria using individual variant curation in Varsome. Because missense variants and variants never observed in public databases such as gnomAD rarely meet ACMG P/LP criteria and are often classified as US (unknown significance), to define our second-tier positive genetic finding, we used the following criteria: absent of exceedingly rare in public databases as well as in our in-house 11,818 multiethnic population controls from the IGM,23 a Revel score ≥0.5,29 and plausibility of the genetic mutation to be associated to the observed COU phenotype. In addition, variants with the very strong strength level of pathogenicity classifier (i.e., null variant in a gene where loss of function is a known mechanism of disease) were classified as positive findings even if other criteria were not fulfilled. We next confirmed prioritized variants through Sanger sequencing in the patient DNA and, when available, in family members for segregation analysis to add support to our pathogenicity adjudication.

Exome CNV Calling and Prioritization

For robust analysis of CNV using ES data, we first divided our COU ES cohort into four batches grouped by exome-capture kits. GATK DepthOfCoverage (v3.6) and exome Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) (v1.0) were used for exome CNV discovery.30 CNVs were called based on hg19 coordinates. For each batch, we computed coverage statistics from the base-recalibrated and indel-realigned, analysis-ready bam files restricting coverage computations to the exome-captured intervals in each kit. Raw coverages were merged, outlier targets and samples were removed, and mean centered data were normalized with principal component analysis to construct a normalized read depth for CNV calling. A subset of 434 COU cases have also been analyzed using chromosomal microarray data. The identification of pathogenic GDs in 162 of these 434 individuals has been previously published (Supplemental Figure 1).16 The DNA array CNV calls were detected using PennCNV as described16,17,19–21 and the results used for comparison, calibration, and validation of the exome CNV calls. After DNA array and exome-based CNV analysis, we used the bedtools intersect function to compare the putative start and end breakpoints of the XHMM-derived CNV against the putative start and end breakpoints of the PennCNV-derived CNV as an orthogonal method to test for congruency. CNVs were annotated with overlapping RefGenes, known CNVs with reported association with a GD, and curated gene sets. Using the same criteria for CNV prioritization as previously described, CNVs were classified as pathogenic (GD-CNV) or likely pathogenic.16,17,19–22 Burden of rare CNVs and pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Fisher exact test or the chi-squared test, as appropriate.

Results

Study Cohort

The total cohort included 733 independent COU cases, of whom 321 (43.8%) individuals had UPJO, 178 (24.2%) had UVJO, and 234 (31.9%) individuals were diagnosed with COU-NOS (Table 1). Most of the cases were of European ancestry (599, 81.7%; Supplemental Figure 2). There was a strong male predominance in COU cases (male 502 [68.5%] versus female 231 [31.5%]). Additional kidney and urinary tract defects were present in 123 (16.7%) cases, of which reflux nephropathy was most prevalent (6.4% of cases). Extrarenal phenotypes were identified in 127 (17.3%) cases with COU, with abnormalities in musculoskeletal system (n=18, 2.5%), central nervous system (n=14, 1.9%), and cardiac defects (n=19, 2.6%) as predominant conditions. One in five patients had a family history of kidney disease, which was higher in cases with COU-NOS than in individuals with UPJO or UVJO (Table 1; odds ratio [OR], 2.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.91 to 3.92; Fisher exact P-value = 3.1 × 10−8 versus combined group of UPJO/UVJO).

Table 1.

Study cohort characteristics

| Characteristics | UPJO (n=321) | UVJO (n=178) | COU-NOS (n=234) | Overall COU Cohort (n=733) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 117 (36.4) | 51 (28.7) | 63 (26.9) | 231 (31.5) |

| Male | 204 (63.6) | 127 (71.3) | 171 (73.1) | 502 (68.5) |

| Laterality | ||||

| Bilateral | 31 (9.7) | 35 (19.7) | 64 (27.4) | 130 (17.7) |

| Left | 164 (51.1) | 95 (53.4) | 95 (40.6) | 354 (48.3) |

| Right | 94 (29.3) | 33 (18.5) | 62 (26.5) | 189 (25.8) |

| Unknown | 32 (10) | 15 (8.4) | 13 (5.6) | 60 (8.2) |

| Genetically determined ancestry | ||||

| European participants | 264 (82.2) | 148 (83.1) | 187 (79.9) | 599 (81.7) |

| Admixed participants | 40 (12.5) | 22 (12.4) | 27 (11.5) | 89 (12.1) |

| Hispanic participants | 6 (1.9) | 5 (2.8) | 12 (5.1) | 23 (3.1) |

| South Asian participants | 5 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (1.2) |

| African participants | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.7) | 8 (1.1) |

| East Asian participants | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) |

| Additional renal phenotype | ||||

| Bladder defect | 2 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.1) | 10 (1.4) |

| DCS | 8 (2.5) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (0.9) | 15 (2) |

| Ectopia | 5 (1.6) | 4 (2.2) | 4 (1.7) | 13 (1.8) |

| Glomerular | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) |

| KHD | 19 (5.9) | 5 (2.8) | 7 (3) | 31 (4.2) |

| Nephronopthisis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Reflux nephropathy | 14 (4.4) | 23 (12.9) | 10 (4.3) | 47 (6.4) |

| Tubular defect | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Nonurinary defect | ||||

| Neural | 8 (2.5) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.4) | 14 (1.9) |

| Craniofacial | 8 (2.5) | 7 (3.9) | 4 (1.7) | 19 (2.6) |

| Cardiac | 5 (1.6) | 5 (2.8) | 9 (3.8) | 19 (2.6) |

| Musculoskeletal | 6 (1.9) | 8 (4.5) | 4 (1.7) | 18 (2.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 (1.9) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.4) | 12 (1.6) |

| Genital | 12 (3.7) | 5 (2.8) | 10 (4.3) | 27 (3.7) |

| General developmental delay | 6 (1.9) | 8 (4.5) | 4 (1.7) | 18 (2.5) |

| Other syndromesa | 0,00 | 0,00 | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) |

| Family history of kidney disease | 47 (14.6) | 35 (19.7) | 82 (35) | 164 (22.4) |

Presented as n (%). UPJO, ureteropelvic junction obstruction; UVJO, ureterovesical junction obstruction; COU-NOS, congenital obstructive uropathy—not otherwise specified; COU, congenital obstructive uropathy; DCS, duplex collecting system; KHD, kidney hypodysplasia.

Other syndromes include Currarino syndrome and Beckwith–Wiedemann.

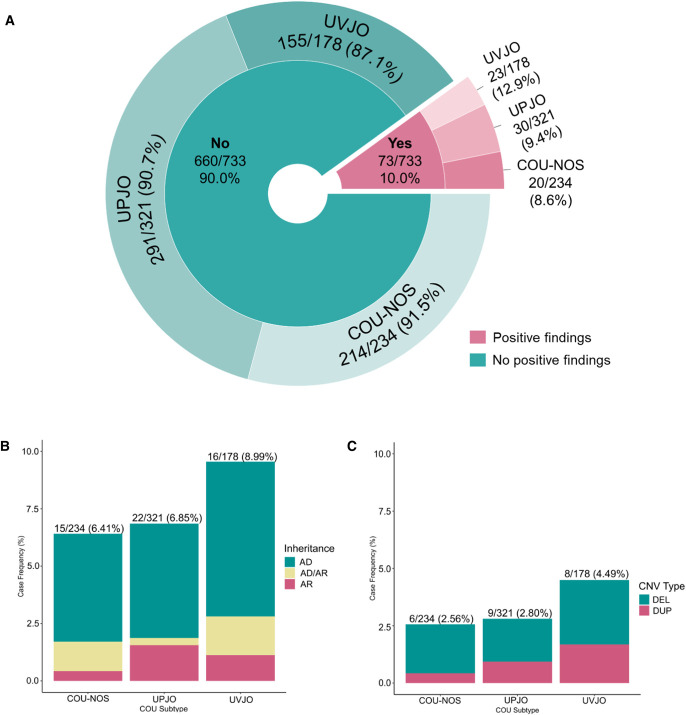

ES Identifies Rare Pathogenic SNVs in 7.2% of Cases with COU

We queried ES data for 382 manually curated genes in 733 cases with COU using ATAV (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1).23 Of these 382 genes known to be associated to CAKUT when mutated, 127 were associated with dominant inheritance (119 autosomal and eight X-linked), 240 with recessive inheritance (225 autosomal, one digenic, and 14 X-linked), and 15 genes associated with both dominant and recessive inheritance (ten autosomal, five X-linked). We retrieved 8525 raw variants from the ATAV database and annotated them using Diagnosticator. After standard quality control, 1677 variants were removed. Additional 1181 variants were further removed because of affecting noncoding regions (ex 5′ or 3′ UTR) or classified as Benign, Likely Benign, or Benign/Likely Benign in ClinVar at the time of analysis. We next analyzed the remaining 5667 variants based on the reported mode of inheritance for all CAKUT disorders associated with the genes. To further prioritize rare variants, we removed variants with more than 0.05% minor allele frequency (AF) and more than 1% AF for dominant and recessive genes, respectively, in all populations from the public repositories ExAC24 and gnomAD v2.1.1 genomes.25 Finally, we individually curated the remaining variants using Diagnosticator and VarSome as decision support tools and applied the first-tier and second-tier criteria to adjudicate positive findings as described above. Finally, we identified positive genetic findings in 53 (7.2%) cases with COU. Of these, 40 (75.4%) individuals had an autosomal dominant (AD) genetic cause of COU, 6 (11.3%) individuals harbored pathogenic SNVs in genes with an AD or recessive mode of inheritance, and 7 (13.2%) individuals had an autosomal recessive (AR) form of COU, demonstrating a significantly skewed distribution toward genes with an AD mode of inheritance in our study cohort. Comparison of COU subcategories did not reveal statistically significant differences in proportions of identified disease-associated SNVs between the three diagnosis groups (chi-squared 2×3, P = 0.57; Figure 1). An overview of all identified SNVs is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic yield of genomic screen in 733 individuals with COU. Differences between COU subgroups for diagnostics SNV and CNV yield were all P > 0.05 by using the 2×3 chi-squared test. (A) The overall in silico diagnostic yield of candidate pathogenic SNV and CNV in the COU cohort is 10.0% (73 of 733 patients). This proportion of genomic contribution to the etiology of COU is in accordance with other congenital kidney and urinary tract phenotypes. (B) Distribution of COU cases carrying candidate pathogenic/likely pathogenic SNVs based on mode of inheritance. SNVs in genes with an AD mode of inheritance were vastly predominant for all COU subtypes. (C) Distribution of GDs, likely pathogenic CNVs, and candidate microdeletions and microduplications covering known genes in COU exome cases. Because pathogenic deletions were much more frequently found than duplications in all COU subtypes, our data implicate that haploinsufficiency or dominant negative effects are the main molecular mechanisms leading to COU. DEL, deletion; DUP, duplication. Figure 1 can be viewed in color online at www.jasn.org.

Table 2.

Identified rare and potentially pathogenic single nucleotide variants

| ID | COU Category | Gene | Variant ID | Variant | Consequence | gnomAD Exome Global AF | Internal Controls AF (N=11,818) | ACMG Classification | ClinVar Significance | REVEL Score | Segregation | Gender | FHX Y/N/U) | Consanguinity (Y/N/U) | Laterality (B/L/R/U) | Additional Genitourinary Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant mode of inheritance | ||||||||||||||||

| P75 | UVJO | ACTG2 | 2-74141956-C-T | c.763C>T | p.Arg255Cys | 4.04E-06 | — | LP | NA | 0.937 | U | M | N | N | L | |

| P18 | UPJO | ALDH18A1 | 10-97376235-A-T (rs200452017) | c.1598T>A | p.Leu533Gln | 1.37E-04 | 2.57E-04 | US | US | 0.915 | U | M | N | U | B | |

| P77 | COU-NOS | ALDH18A1 | 10-97371187-C-G | c.1930G>C | p.Ala644Pro | — | — | US | US | 0.652 | U | M | U | N | B | |

| P58 | COU-NOS | ARID1B | 6-157099426-A-AG | c.189_190insG | p.Gln122AlafsTer110 | — | 5.68E-04 | LB | US | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| P83 | UVJO | BMP4 | 14-54418617-C-CT | c.323dupA | p.Arg109AlafsTer26 | — | — | LP | NA | NA | U | F | N | N | U | KHD |

| P09 | UVJO | BMP7 | 20-55777630-C-T | c.661G>A | p.Glu221Lys | — | — | US | NA | 0.771 | Segregating | M | U | U | R | |

| P78 | UVJO | BRAF | 7-140501356-C-T | c.716G>A | p.Arg239Gln | — | — | US | NA | 0.863 | Inherited maternal | M | N | U | U | |

| P36 | COU-NOS | COL5A1 | 9-137711989-G-T | c.4474G>T | p.Gly1492Cys | — | — | P | P | 0.994 | U | M | N | U | B | Cryptochidism |

| P43 | UPJO | DSTYK | 1-205180640-C-T | c.24G>A | p.Trp8Ter | — | — | P | P | NA | Segregating | M | N | U | L | N |

| P34 | COU-NOS | EYA1 | 8-72129030-A-C | c.1239T>G | p.Cys413Trp | — | — | US | NA | 0.823 | U | M | N | U | R | |

| P63 | UPJO | FOXC1 | 6-1611089-G-A | c.409G>A | p.Val137Ile | — | — | US | NA | 0.621 | Paternal | M | Y | N | R | Double urethra |

| P56 | COU-NOS | GREB1L | 18-19019599-G-A | c.949+1G>A | NA | — | — | LP | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| P05 | COU-NOS | HNF1B | 17-36091625-G-C (rs138986885) | c.1006C>G | p.His336Asp | 1.84E-04 | 3.83E-04 | US | Conflicting | 0.702 | Inherited maternal | M | Y | N | R | |

| P51 | UPJO | HNF1B | 17-36091625-G-C (rs138986885) | c.1006C>G | p.His336Asp | 1.84E-04 | 3.83E-04 | US | Conflicting | 0.702 | U | F | N | U | L | |

| P79 | UPJO | HNF1B | 17-36061038-A-T | c.1484T>A | p.Met495Lys | — | — | LP | Conflicting | 0.905 | U | F | N | U | R | |

| P66 | UVJO | HNF1B | 17-36104610-G-A | c.266C>T | p.Pro89Leu | 1.61E-05 | — | US | NA | 0.961 | U | M | N | N | L | |

| P25 | UVJO | HNF1B | 17-36091633-C-A | c.998G>T | p.Gly333Val | 3.99E-06 | — | US | NA | 0.572 | U | M | N | U | B | |

| P17 | UVJO | HOXD13 | 2-176959349-G-A | c.923G>A | p.Arg308His | 3.18E-05 | 4.23E-05 | US | US | 0.791 | U | M | N | U | L | |

| P68 | UPJO | KAT6B | 10-76788346-GTCTA-G (rs199470470) | c.3769_3772delTCTA | p.Lys1258GlyfsTer13 | — | — | P | P | NA | U | M | N | N | B | Micropenis, cryptorchidism, piriformis bladder |

| P72 | UPJO | KRAS | 12-25378651-T-C (rs202247812) | c.347A>G | p.Asn116Ser | — | — | LP | NA | 0.878 | U | M | N | N | L | |

| P31 | UVJO | MAP2K1 | 15-66782934-C-G | c.1163C>G | p.Thr388Ser | — | — | US | NA | 0.32 | U | F | U | U | B | |

| P41 | UVJO | NFIA | 1-61554070-C-T | c.277C>T | p.Leu93Phe | — | 4.24E-05 | US | NA | 0.651 | Inherited maternal | F | Y | U | R | |

| P85 | UPJO | NOTCH2 | 1-120464967-C-T | c.5105G>A | p.Arg1702Gln | 7.95E-06 | — | US | Conflicting | 0.677 | U | M | U | N | L | |

| P24 | UPJO | NOTCH2 | 1-120462920-G-A (rs372061331) | c.5411C>T | p.Ser1804Leu | 1.19E-05 | 4.24E-05 | US | NA | 0.611 | Inherited paternal | F | U | U | B | |

| P22 | COU-NOS | NRIP1 | 21-16337149-CTTAAA-C | c.3360_3364delTTTAA | p.Asn1120LysfsTer6 | — | — | NA | NA | NA | Inherited maternal | M | Y | U | U | Post infectious glomerulonephritis |

| P73 | COU-NOS | NSD1 | 5-176631267-CAGAA-C | c.409_412delGAAA | p.Glu406LysfsTer12 | — | — | NA | P | NA | U | F | N | N | B | VUR |

| P38 | UVJO | PAX2 | 10-102510558-C-T | c.320C>T | p.Pro107Leu | 7.95E-06 | — | LP | US | 0.922 | U | M | N | U | B | |

| P12 | UPJO | PAX2 | 10-102510600-AG-A | c.365delG | p.Gly122AlafsTer37 | — | — | LP | NA | NA | De novo | M | N | U | L | VUR |

| P80 | UPJO | PIK3R2 | 19-18273294-G-A | c.1087G>A | p.Gly363Ser | — | — | US | NA | 0.845 | U | M | N | U | L | VUR |

| P03 | UPJO | PKD2 a | 4-88928887-T-A | c.2T>A | p.Met1Lys | 3.62E-05 | — | LP | NA | 0.318 | NA | M | U | U | L | |

| P55 | UPJO | RPS24 | 10-79796953-A-C | c.281A>C | p.His94Pro | — | — | US | NA | 0.676 | U | F | N | U | L | |

| P06 | COU-NOS | SALL1 | 16-51175430-C-T | c.703G>A | p.Ala235Thr | 7.96E-06 | 1.27E-04 | US | Conflicting | 0.713 | Inherited maternal | M | Y | N | R | |

| P64 | UVJO | SHH | 7-155599442-AT-A | c.1delA | p.Met1CysfsTer19 | — | 4.82E-05 | LP | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| P61 | COU-NOS | SIX5 | 19-46272101-A-G | c.2T>C | p.Met1? | 7.97E-06 | — | LP | NA | 0.539 | U | M | N | U | L | |

| P21 | UVJO | SPECC1L | 22-24718863-C-T | c.1915C>T | p.Arg639Ter | — | — | LP | US | NA | De novo | M | N | U | L | VUR |

| P20 | UPJO | TBX18 | 6-85453979-C-T | c.1004G>A | p.Arg335Lys | — | — | LP | NA | 0.565 | Inherited paternal | M | N | U | R | |

| P30b | UPJO | TBX18 | 6-85446657-G-A | c.1570C>T | p.His524Tyr | 8.06E-06 | — | US | P | 0.757 | U | F | U | U | L | |

| P04b | COU-NOS | TBX18 | 6-85466546-G-C | c.641C>G | p.Ala214Gly | 7.96E-06 | — | US | NA | 0.53 | U | M | N | N | B | VUR, KHD |

| P42 | UPJO | TP63 | 3-189608591-T-A | c.1666T>A | p.Leu556Met | — | — | US | NA | 0.544 | U | F | Y | U | B | Solitary kidney |

| P40 | UPJO | TP63 | 3-189584503-G-A | c.799G>A | p.Val267Ile | 1.19E-05 | 4.24E-05 | US | US | 0.599 | U | M | N | U | L | |

| AD or recessive mode of inheritance | ||||||||||||||||

| P74b | UVJO | FGFR3 | 4-1808377-G-A (rs104886024) | c.2135G>A | p.Arg712His | — | — | US | NA | 0.896 | U | M | N | N | U | |

| P74b | UVJO | TBX6 | 16-30100037-C-A | c.745G>T | p.Val249Leu | — | — | US | NA | 0.943 | U | M | N | N | U | |

| P33 | UVJO | TNXB | 6-32010285-C-A | c.12157G>T | p.Glu4053Ter | 4.01E-06 | — | LP | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | R | |

| P65 | UPJO | TNXB | 6-32010308-G-A | c.12134C>T | p.Thr4045Ile | — | — | US | NA | 0.564 | U | M | Y | U | L | |

| P82 | COU-NOS | TNXB | 6-32018039-T-TG (rs34629684) | c.9174dupC | p.Ile3059HisfsTer30 | — | — | LP | NA | NA | U | M | Y | N | R | |

| P57 | COU-NOS | TNXB | 6-32021490-T-G | c.8468-2A>C | NA | 1.23E-05 | — | LP | NA | NA | U | F | Y | U | L | |

| P59 | COU-NOS | TNXB | 6-32035600-G-A | c.6382C>T | p.Gln2128Ter | — | — | NA | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | B | |

| P59 | COU-NOS | TNXB | 6-32057150-CCT-C | c.2363_2364delAG | p.Glu788GlyfsTer18 | — | — | NA | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | B | |

| AR mode of inheritance | ||||||||||||||||

| P32 | UPJO | C5orf42 | 5-37157912-A-T | c.4511T>A | p.Leu1504Ter | 2,39E-05 | 8,52E-05 | NA | P | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| 5-37226877-TA-T | c.1819delT | p.Tyr607ThrfsTer6 | 1.61E-04 | 1.27E-04 | NA | P/LP | NA | U | M | N | U | L | ||||

| P07 | COU-NOS | DYNC2H1 | 11-102980304-AT-A | c.2delT | p.Met1ArgfsTer23 | 4.03E-06 | — | NA | US | NA | Inherited maternal | M | Y | U | L | |

| 11-103175354-G-A | c.11287G>A | p.Ala3763Thr | 5.63E-05 | 1.27E-04 | NA | US | 0.521 | Inherited paternal | M | Y | U | L | ||||

| P28 | UPJO | FREM1 | 9-14842659-C-T | c.1394-1G>A | NA | — | — | NA | NA | NA | U | M | U | U | L | |

| 9-14859241-C-T | c.571G>A | p.Gly191Arg | 6.09E-04 | 1.70E-04 | NA | Conflicting | 0.048 | U | M | U | U | L | ||||

| P29 | UVJO | HPSE2 | 10-100904148-G-A (rs267606865) | c.457C>T; homozygous | p.Arg153Ter | 1.20E-05 | 4.24E-05 | P | P | NA | U | F | N | U | L | |

| P50 | UPJO | KIAA1109 | 4-123161006-ATAGTG-A | c.4170_4174delTAGTG | p.Asp1390GlufsTer8 | — | — | LP | NA | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| 4-123161012-A-C | c.4175A>C | p.Glu1392Ala | — | — | US | NA | 0.363 | U | M | N | U | L | ||||

| P08 | UVJO | MYH11 | 16-15814859-T-G | c.4628A>C | p.Glu1543Ala | 3.98E-06 | — | US | US | 0.918 | U | M | N | Y | B | VUR, bladder pseudodiverticuli, hypospadia |

| 16-15853489-G-A | c.1345C>T | p.Arg449Trp | 3.98E-06 | — | US | NA | 0.742 | U | M | N | Y | B | VUR, bladder pseudodiverticuli, hypospadia | |||

| P63 | UPJO | PKHD1 | 6-51613307-A-T | c.9107T>A | p.Val3036Glu | — | — | US | Confliciting | 0.618 | U | M | Y | N | R | |

| 6-51924836-G-A (rs376040501) | c.1123C>T | p.Arg375Trp | 2.39E-05 | 4.25E-05 | P | P/LP | 0.659 | U | M | Y | N | R | ||||

| P27 | UPJO | SDCCAG8 | 1-243471334-G-T | c.349G>T | p.Glu117Ter | 1.19E-05 | — | P | P | NA | U | M | N | U | L | |

| 1-243581270-A-G | c.1310A>G | p.Glu437Gly | — | — | LB | NA | 0.114 | U | M | N | U | L | ||||

COU, congenital obstructive uropathy; AF, allele frequency; AD, autosomal dominant; ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics; FHX, family history; UVJO, ureterovesical junction obstruction; UPJO, ureteropelvic junction obstruction; US, uncertain significance, B. bilateral, COU-NOS, congenital obstructive uropathy—not otherwise specified; (L)P, (likely) pathogenic; NA, not available; U, unknown; M, male; N, no; F, female; KHD, kidney hypodysplasia; Y, yes; AR, autosomal recessive; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux.

This individual with a polycystic kidney disease variant was screened and presented one simple cortical cyst at age 32 years detected by abdominal computed tomography scan.

Individual also carries a genomic disorder.

When zooming in at the contribution of each single gene to the etiology of COU, we identified a striking genetic heterogeneity (33 distinct genes affected in 53 cases) with only a handful of genes harboring pathogenic variants in more than one individual (Table 2). The latter included TNXB (n=6), HNF1B (n=4), TBX18 (n=3), PAX2 (n=2), ALDH18A1 (n=2), and TP63 (n=2). Genes with an AD mode of inheritance predominantly encoded for transcription factors or proteins with a pivotal role in transcription (13/30, 43%; e.g., HNF1B, PAX2, TBX18, SALL1, EYA1, FOXC1, BMP4, BMP7, and others). Interestingly, variants in these genes were identified across all three COU subphenotypes, indicating the highly variable expressivity within the genetic etiology of urinary tract malformations, and suggesting that, at least for a fraction of genes involved in COU etiology, the underlying subphenotype has no predictive value for the underlying molecular cause. Other important subgroups of AD genes known to be associated with COU encode signaling molecules that play a role in multiple developmental processes and cell fate decisions, such as BRAF, NOTCH2, and SHH.31–33 This is in contrast with the variants found in genes with an AD/recessive or AR mode of inheritance, where the molecular action of genes was much more heterogeneous, including genes that encode for extracellular matrix proteins (TNXB, FREM1),34,35 muscle proteins (MYH11),36 nuclear factors (SDCCAG8),37 and transmembrane proteins (DYNC2H1).38 In addition to the aforementioned genetic pleiotropy of genes underlying the different COU phenotypes, we observed mutations in TNXB mostly in cases with COU-NOS (four of five individuals). As variants in TNXB have been previously predominantly associated to VUR,35,39 this specific finding most likely reflects the challenging diagnostic interpretation of hydronephrosis and its distinction from VUR when a voiding cystourethrogram has not been performed or available. Segregation analysis using in a subset of affected cases for whom parental DNA was available for analysis (Table 2) identified de novo pathogenic SNVs in two cases. In another two individuals with COU, we could establish familial segregation of the variant in affected individuals. Finally, ten variants were either maternally or paternally inherited from parents with an unknown urinary tract phenotype. Owing to the retrospective nature of the study and the different infrastructure at individual recruitment sites, parental DNA was not available for most cases, thus preventing complete assessment of the variants' inheritance patterns in our cohort.

Further annotation of variants identified additional eight cases with COU (UPJO n=3, UVJO n=2, COU-NOS n=3) that carried a heterozygous SNV in eight distinct genes with an AD mode of inheritance which were completely absent in public repositories and were also predicted to be deleterious according to different publicly accessible prediction tools but did not fulfill our first-tier or second-tier criteria (Supplemental Table 2). These eight SNVs were classified as variants of uncertain significance pending additional genetic or segregation support.

Rare Pathogenic CNVs Make up the Genetic Architecture of an Additional 3.1% of Cases with COU

Under the hypothesis that a fraction of the 680 unsolved cases with COU might be attributable to CNVs associated to GDs, we conducted an exome-wide CNV analysis using GATK DepthOfCoverage and XHMM using ES data from the entire cohort (Supplemental Figure 1). Of 733 cases, 468 (63.8%) had also an available Illumina DNA microarray that was used to call CNVs as previously described16,17,19–22 and results used for cross-validation of the CNV calls from ES. Using this combinatorial approach, we identified 18 distinct GDs in 23 (3.1%) unique COU cases (Table 3). When compared with 134 (0.6%) GDs in 21,498 in controls, this represented a highly significant burden excess of GD in COU (OR, 5.16; 95% CI, 3.14 to 8.14; Fisher exact P = 2.09×10−9).

Table 3.

Identified genomic disorders and likely pathogenic copy number variants

| ID | COU Category | CNV | CNV Size (Mb) | Type | GD-CNV | Dosage-Sensitive Genes | CAKUT (Human) | Sex | FHX | Consanguinity | Additional Genitourinary Phenotype | Extrarenal Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P74a | UVJO | chr1: 145415279-145763815 | 0.349 | DEL | 1q21.1 susceptibility locus for TAR syndrome | RBM8A | M | N | N | |||

| P84 | UVJO | chr1: 145415279-145748587 | 0.333 | DUP | 1q21.1 TAR syndrome region duplication | RBM8A | M | N | N | VUR | ||

| P30a | UPJO | chr1: 146496480-147415562 | 0.919 | DEL | 1q21.1 recurrent microdeletion | F | N | U | ||||

| P15 | UPJO | chr7:144702944-148544434 | 3.841 | DEL | 7q36.1 deletion | CUL1, EZH2 | M | U | U | |||

| P26 | COU-NOS | chr15: 30918893-32404534 | 1.486 | DEL | 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome | F | N | U | ||||

| P60 | COU-NOS | chr15:23684690-28557995 | 4.873 | DUP | 15q11.2 Prader–Willi/Angelman (type 1) reciprocal duplication | M | N | U | ||||

| P11 | UPJO | chr16: 29675050-30199897 | 0.525 | DEL | 16p11.2 deletion | PRRT2 | TBX6 | M | Y | U | VUR, KHD | Bifid thumbs |

| P44 | UVJO | chr16: 15460510-17564653 | 2.104 | DEL | 16p13.11 recurrent microdeletion | MYH11 | M | N | U | |||

| P45 | UVJO | chr16:14960412-16357072 | 1.397 | DUP | 16p13.11 duplication | MYH11 | M | N | U | Preauricular appendix | ||

| P67 | UVJO | chr16: 14947324-16359036 | 1.412 | DEL | 16p13.11 recurrent microdeletion | MYH11 | M | N | U | LUTM (phimosis) | Growth retardation | |

| P76 | COU-NOS | chr16: 15460510-17353355 | 1.893 | DEL | 16p13.11 recurrent microdeletion | MYH11 | M | N | N | Perthes disease | ||

| P04a | COU-NOS | chr17: 34851067-36293050 | 1.442 | DEL | RCAD deletion | ACACA, HNF1B | HNF1B | M | N | N | VUR, KHD | |

| P10 | COU-NOS | chr17: 34797485-36340198 | 1.543 | DEL | RCAD deletion | ACACA, HNF1B | HNF1B | M | N | N | Facial dysmorphism, pervasive developmental disorder | |

| P19 | UPJO | chr17: 34842442-36104994 | 1.263 | DEL | RCAD deletion | ACACA, HNF1B | HNF1B | M | N | U | KHD | |

| P37 | UPJO | chr17: 29051270-30377236 | 1.326 | DEL | NF1 microdeletion syndrome | NF1, SUZ12 | F | N | U | Neurofibromatosis type I | ||

| P46 | UVJO | chr22: 20706073-21386101 | 0.680 | DEL | DiGeorge A-D, DiGeorge B-D, DiGeorge C-D, DiGeorge C-E | M | Y | U | Mild grandular hypospadia, high arched palate, slight antimongolioid slant | |||

| P70 | UPJO | chr22: 18893888-20307511 chr22: 20706073-21571022 |

2.279 | DEL | DiGeorge A-B, DiGeorge A-D, DiGeorge C-D, DiGeorge A-D, DiGeorge B-D, DiGeorge C-E | DGCR8 | M | N | N | Facial dysmorphism, syndactyly, growth retardation | ||

| P47 | UPJO | chrX: 71693492-72092398 | 0.399 | DUP | Triple X | HDAC8 | F | N | U | |||

| P69 | UVJO | chrX: 149638017-155004401 | 5.366 | DEL | Xq28 rett syndrome | SLC6A8, MECP2, NSDHL, F8, L1CAM, ABCD1, MTM1, RAB39B, FLNA, DKC1, IKBKG, AVPR2 | NAA10, NSDHL, CCNQ, DKC1 | F | N | N | Interatrial defect | |

| P54 | UPJO | chr2: 60679700-66798661 | 6.119 | DUP | WDPCP | F | N | U | ||||

| P16 | UVJO | chr2: 141072471-142888527 | 1.816 | DUP | LRP1B | F | N | U | ||||

| P23 | UPJO | chr9: 137320857-137630692 | 0.310 | DUP | COL5A1 | F | N | U | ||||

| P52 | COU-NOS | chr14: 31495110-33293979 | 1.799 | DEL | HECTD1, ARHGAP5, AKAP6 | F | Y | U |

COU, congenital obstructive uropathy; CNV, copy number variants, GD, genomic disorder; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract; FHX, family history; UVJO, ureterovesical junction obstruction; DEL, deletion; TAR, thrombocytopenia-absent radius; M, male; N, no; DUP, duplication; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux; F, female; U, unknown; UPJO, ureteropelvic junction obstruction; COU-NOS, congenital obstructive uropathy—not otherwise specified; Y, yes; RCAD, renal cysts and diabetes; LUTM, lower urinary tract malformation; KHD, kidney hypodysplasia.

Individual also carries a single nucleotide variant.

Similar to what is observed for the SNVs above, the landscape of CNVs showed high genetic heterogeneity with 18 pathogenic CNVs at 15 chromosomal loci in 23 independent COU cases. In fact, we observed only four loci that were copy number variable in more than one individual: the chr.1q21.1 thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome region (one deletion and one duplication; both UVJO); the chr.16p13.11 locus (four deletions, one duplication; four UVJO, one COU-NOS); the 17q12 renal cysts and diabetes (RCAD) syndrome region (three deletions; two COU-NOS, one UPJO); and the chr.22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome region (i.e., DiGeorge/Velocardiofacial Syndrome), for which one UVJO case carried a 22q11.2 microdeletion between low-copy-repeats (LCRs) B-D, while one individual with UPJO carried a 22q11.2 microdeletion between LCR A-D (Table 3). Taken together, these four GDs loci explained nearly half (11/23, 47.8%) of the GD carriers in our cases with COU. Although cases with UVJO had a higher burden of GD (8/178, 4.5%) as compared with cases with UPJO or cases with COU-NOS (9/321, 2.8%; 6/234, 2.6%, respectively), this difference was not statistically significant (chi-squared 2×3, P = 0.48; Figure 1). Larger sample size cohorts are required to verify if indeed the UVJO subcategory is more frequently caused by GD as compared with the other classes of COU. Interestingly, COU cases were enriched for deletions compared with duplications (16 deletions versus seven duplications), implicating reduced gene dosage using haploinsufficiency as the main molecular mechanism that underlies obstructive uropathies.

Additional annotation of CNVs identified four microdeletions and one microduplication in five COU individuals who all were <100 kb in size, intersected with known CAKUT genes in humans or mice, and were completely absent in 21,498 controls (Supplemental Table 3). Because these CNVs have not (yet) been linked to a known GD that includes CAKUT, we defined these additional CNVs as variants of unknown significance.

Importantly, pathogenic CNVs were identified in three individuals with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic SNV or genotype (and vice versa) (Table 3), supporting a correct causality attribution in the two independent analyses for most of the patients. Of these cases carrying a potentially pathogenic SNV and CNV, one patient with UVJO (P74) carried two ultrarare and potentially pathogenic SNVs in FGFR3 (with an AD or recessive mode of inheritance) or TBX6 (a driver of the CAKUT phenotypes in the chromosome 16p11.2 microdeletion syndrome16) as well as a 349 kb deletion at the incompletely penetrant chromosome 1q21.1 susceptibility locus for TAR syndrome. Another patient (P30) with UPJO carried a very rare ClinVar pathogenic SNV in TBX18, a known gene associated to ureter maldevelopment,40 and a 919 kb deletion at chromosome 1q21.1, a locus shown to display incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity.41 Finally, in the last patient, affected by COU-NOS (P04), we identified another very rare SNV in TBX18 and the typical 1.4 Mb RCAD deletion at chromosome 17q21. Interestingly, these three cases with COU did not present with a more severe urinary or extra-urinary phenotype as compared with the rest of the cohort. Hence, to dissect the exact pathomechanisms leading to COU in these individuals, additional genetic and functional studies need to be performed.

The overall genomic architecture of COU indicates a diagnosis in approximately one in ten individuals, identifies both commonalities and differences among COU subphenotypes, and supports convergence between SNVs and CNVs on COU genetic drivers.

In our cohort of individuals with COU, the diagnostic yield of candidate pathogenic SNVs and CNVs in cases was 73 of 733 (10.0%) cases (Figure 1). As expected, the overall diagnostic yield of 127 individuals with COU and an extrarenal, syndromic phenotype (30/127 [23.6%]) was much higher than in 606 individuals with isolated, nonsyndromic COU (43/606 [7.1%]) (OR, 4.05; 95% CI, 2.42 to 6.77; Fisher exact P = 3.16 × 10−7). By contrast, the presence of a positive family history was not different between cases with a genomic diagnosis (16/73, 21.9%) and cases without a genomic diagnosis (148/660, 22.4%; OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.85; Fisher exact P = 1.00). The genomic landscape across COU subphenotypes shows remarkable overlap in molecular etiologies but also differences between categories were observed. First, the distribution of the overall diagnostic yield among phenotypes was n=30 (9.4%), n=23 (12.9%), and n=20 (8.6%) for UPJO, UVJO, and COU-NOS, respectively (Supplemental Figure 3). Comparison between COU phenotypes did not show differences in the distribution of diagnostic yield (2×3 chi-squared P = 0.3). Another example of the overlap between COU subcategories is the well-known pleiotropic phenotype that is related to haploinsufficiency of HNF1B. In fact, we identified pathogenic SNVs in HNF1B across all COU phenotypes. In addition, we detected chr.17q12 microdeletions (HNF1B locus) in two cases with COU-NOS and one case with UPJO. These findings are in accordance with the fact that the HNF1B-related diseases play a role throughout urinary tract development resulting in anomalies across the entire CAKUT spectrum.

Convergence of SNV and CNV data also provides remarkable lead points into the potential pathomechanistic pathways of candidate genes for CAKUT. We identified five COU cases (four deletions and one duplication) harboring microdeletions within the chr.16p13.11 locus, encompassing MYH11, as well as one case affected by severe bilateral obstructive megaureters, additional urinary tract anomalies, and extrarenal developmental defects, with biallelic mutations in this gene. MYH11 encodes a heavy chain of myosin expressed in the kidney and the musculature of the urinary tract and the bladder. Interestingly, recessive mutations in MYH11 cause megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome 2 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 619351), in which affected individuals manifest, among other phenotypes, megabladder, dilated ureters, and hydronephrosis.36,42 Conversely, heterozygous mutations in MYH11 have been associated to visceral myopathy-2 (OMIM 619350), a less severe form of smooth muscle myopathy with variable phenotypic expression, which also feature urinary tract obstruction.43,44 Taken together, our findings support the implication that MYH11 is a key dosage-sensitive gene in the urinary tract with its expression possibly correlating with the severity of COU.

Discussion

COU is a subcategory of CAKUT that includes highly heterogeneous phenotypes with a variable clinical presentation and a virtually unpredictable outcome. The major reason for this is related to the fact that the molecular architecture of COU is characterized by high genetic heterogeneity, incomplete penetrance, and variable expressivity, which both hamper personalized prognostication and treatment, as well as genetic discovery. Our study incorporates individuals with developmental ureteral defects who have been subjected to a comprehensive genetic screen that includes whole ES for SNV and CNV analyses. In our hands, this genomic evaluation demonstrated a diagnostic yield of 10.0% of cases. Despite restricting our analysis to only upper urinary tract obstruction phenotypes and conducting subgroup investigation, we found significant overlap between COU's genetic background and other CAKUT phenotypes such as KHD and VUR.16,17,19–22,45 Our findings alone are yet another confirmation that developmental defects of the kidney and urinary tract are part of a spectrum of congenital malformations that, at least in part, arise from similar molecular alteration. This in turn intimates that even with detailed clinical and imaging workup, our ability to predict the underlying genetic defect is marginal. In fact, the strong variable expressivity of these genetic defects underlies the clinical observation that multiple CAKUT phenotypes occur within individual families, and even within the same individual, notwithstanding the fact that all members carry the same genetic mutation.46–48 The finding that the molecular etiology of COU subcategories shows strong similarities is important because the exact clinical definition of COU phenotypes, and CAKUT at large, is often challenging. Therefore, if our capability to ascertain diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment at the individual level is currently limited, this observed genetic heterogeneity and variable expressivity of COU legitimize a genetic first diagnostic approach to these developmental defects, even when extensive (and potentially burdening) clinical and imaging characterization is not completely available or uniform. The same therefore might be true for genetic discovery studies: While there is an obvious value to obtain detailed clinical phenotyping for studies targeted at specific CAKUT subcategories, the aggregation of large cohort of kidney and urinary tract defects at large is likely to lead to the identification of novel susceptibility genes and variants that predispose to CAKUT in its more broad manifestations.

Our study also demonstrates that the genetic architecture of COU is likely less well-defined and more complex as compared with other CAKUT subgroups. In fact, congenital kidney anomalies usually show a higher yield of pathogenic SNVs and CNVs,49–53 indicating a more Mendelian nature of kidney parenchymal defects as compared with ureteric conditions. One explanation for this observation can be traced back to selective pressure: While kidney malformations significantly affect early life morbidity and mortality and hence are likely to be enriched in highly deleterious mutations that are classified as pathogenic in a clinical genetic diagnostic framework, COU, showing more variable and, on average, more benign course, is likely to be characterized by a more complex genetic determination. Another explanation for this difference with other CAKUT subgroups is the fact that not all COU phenotypes originated from aberrant urinary tract development by definition, as for example, UPJO may also be caused by ectopic vasculature compression or dynamic dysfunction of the ureteral smooth muscle cells.54 In our cohort, we could not make a clear distinction between these nondevelopmental causes of COU purely based on clinical and imaging grounds. Although the genomic diagnostic yield is strongly dependent on cohort characteristics and enrollment criteria, our findings are in line with the clinical observation that COU-related phenotypes show different incidence and severity as compared with KHD.55 In this study, we provide evidence that, by simultaneously assessing SNVs and CNVs with large effect size, we can deliver a genetic diagnosis in up to one in ten cases with COU. The diagnostic yield should be interpreted in the context of a predictive algorithm to implicate pathogenicity, which, to favor accuracy, maybe penalizing for the interpretation of missense variants of variants that escape the clear-cut definition of Mendelian mutations and may incorporate inconsistencies.56 Our findings particularly indicate that genetic testing has high yield when extrarenal manifestations are present in individuals with COU, which is in line with recent clinical practice recommendations for genetic testing in CAKUT.57 At the same time, our study points out that a molecular etiology cannot be identified in approximately 90% of patients. This large unsolved fraction of COU might be attributable to yet undiscovered Mendelian genes or structural variants, common variants with small effect size and a complex polygenic background, low-frequency variants with moderate effect size that are more difficult to assess, and/or a combination of all of the above. Epigenetic, environmental, and stochastic factors are also likely to play a significant role. As large sequencing and genotyping efforts are being undertaken, all these different modes of genetic determination will be tested.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and family members for participation in this study.

Footnotes

Dina F. Ahram, Tze Y. Lim, Juntao Ke, and Gina Jin contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures

D.F. Ahram reports employer: Quest Diagnostics. G.B. Appel reports consultancy: Achillion, Alexion, Apellis, Arrowhead, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chemocentryx, Chinook, E. Lilly, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Genzyme-Sanofi, Mallinkrodt, Merck, Novartis, Omeros, Pfizer, Reata, Travere therapeutics, and Vertex therapeutics; research funding: Achillion, Alexion, Apellis, Chemocentryx, Equillium, Genentech-Roche, Goldfinch, Mallinkrodt, Novartis, Reata, and Sanofi Genzyme; honoraria: Aurinia and GlaxoSmithKline; patents or royalties: UpToDate; advisory or leadership role: Achillion, Alexion, Apellis, Arrowhead, Aurinia, BM Squib, Chinook, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Reata, Roche, Sanofi, UpToDate—Editorial Board, Med Advisory board for Alexion; and speakers bureau: Aurinia—lectures on Lupus Nephritis and GSK—lectures on Lupus Nephritis. A.S. Bomback reports consultancy: Apellis, Catalyst, Chemocentryx, Novartis, Otsuka, Q32, Silence Therapeutics, and Visterra; and honoraria: Alexion, Aurinia, Calliditas, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Principio, Travere, and UpToDate. M. Bonomini reports consultancy: Astellas; research funding: Hexal and Iperboreal Pharma; advisory or leadership role: GSK and Travere Therapeutics; and speakers bureau: Astellas and Nipro. P.A. Canetta reports consultancy: Chinook, Novartis, Otsuka, and Travere and research funding: Calliditas, Novartis, and Travere. D. Chatterjee reports employer: Citibank and H.C. Wainwright & Co and patents or royalties: spouse has a patent with Columbia University Medical Center, not with any for-profit company. E. Cocchi reports research funding: American Society of Nephrology. D.J. Cohen reports consultancy: Alexion—International aHUS Registry—Scientific Advisory Board; research funding: CSL Behring and Natera; honoraria: ITB Pharmaceuticals, Novarrtis, and Veloxis; advisory or leadership role: Alexion—aHUS International Registry—Scientific Advisory Board; and other interests or relationships: American Society of Transplantation—member, NY Society of Nephrology—member, and The Transplantation Society—member. D. Drożdż reports research funding: Roche. E. Fiaccadori reports consultancy: Astellas, AstraZeneca, BBraun, and Nipro and other interests or relationships: Member European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition and Member Italian Society of Nephrology. L. Gesualdo reports consultancy: AstraZeneca, Baxter, Chinook, Estor, GSK, Medtronic, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pharmadoc, Retrophin, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, and Travere; research funding: Abionyx and Sanofi; honoraria: Astellas, Astrazeneca, Estor, Fresenius, Travere, and Werfen; patents or royalties: McGraw-Hill Education (Italy) Srl; and advisory or leadership role: Board of Directors (SIN, RPS, ERA-EDTA), Journal of Nephrology, and Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation Journal. A.G. Gharavi reports consultancy: Astra Zeneca Center for genomics research, Goldfinch Bio: Actio biosciences, and Novartis: Travere; ownership interest: Actio; research funding: Natera and Renal Research Institute; honoraria: Alnylam and Sanofi; and advisory or leadership role: Editorial board: JASN and Journal of Nephrology. Because A.G. Gharavi is an editor of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, he was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. A guest editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript. S. Guarino reports speakers bureau: Ferring. Z. Gucev reports consultancy: Novo Nordisk; advisory or leadership role: Novo Nordisk; and speakers bureau: Takeda. K. Kiryluk reports consultancy: Calvariate and HiBio and research funding: Aevi Genomics, AstraZeneca, Bioporto, Vanda, and Visterra. G. La Manna reports consultancy: Alexion, Astellas, Eli-Lilly, Hansa-Biopharma, Travere therapeutics, and Vifor. S. Lambert reports ownership interest: stock in Abbvie and Abbott. R.P. Lifton reports consultancy: Genentech; ownership interest: Merck and Roche; and advisory or leadership role: Genentech Board of Directors and Roche Board of Directors. F. Lin reports honoraria: lectures and seminars in academic institutions and advisory or leadership role: JASN editorial board. J. Mckiernan reports consultancy: miR Scientific and advisory or leadership role: miR Scientific. M. Miklaszewska reports Honoraria: Medycyna Praktyczna—Pediatria. M. Mizerska-Wasiak reports other interests or relationships: European Renal Association-European Dialysis Transplantation Association—member and European Society Pediatric Nephrology—member. G. Montini reports consultancy: Alnyalam, Bayern, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Kiowa Kyrin, and Sandoz and advisory or leadership role: Alylam and Bayern. J. Radhakrishnan reports consultancy: Angion Biomedica, Ani Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Chinook, Equillium Bio, Goldfinch Bio, Novartis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Reistone Biopharma, Sanofi Genzyme, and Travere Therapeutics; research funding: Bayer, Goldfinch Bio, Vertex pharmaceuticals, and Travere Therapeutics; honoraria: Angion Biomedica, Ani Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Chinook, Equillium Bio, Goldfinch Bio, Novartis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Reistone Biopharma, Sanofi Genzyme, and Travere Therapeutics; and advisory or leadership role: Kidney International and Kidney International Reports. A. Ranghino reports that spouse works in Diatech Pharmacogenetics s.r.l. S. Sanna-Cherchi reports research funding: DoD and NIH/NIDDK; honoraria: Travere Therapeutics; and advisory or Leadership Role: Editorial Boards with no royalties. D. Santoro reports honoraria: Alexion, Travere Therapeutics, Viphor Pharma, and Fresenius and advisory or leadership role: George Clinical. M. Szczepanska reports research funding: FMS in Zabrze and SUM in Katowice; honoraria: Baxter, Roche, and Swixx; and other interests or relationships: ERA-EDTA, ESPN, Polish Society for Pediatrics, and Polish Society for Pediatric Nephrology. R. Westland reports research funding: Dutch Kidney Foundation (20C002). M. Zaniew reports honoraria: Alnylam. L. Zibar reports honoraria: Medison Pharma and Servier. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by grants (P20 DK116191, RO1 DK103184, and R01 DK115574) from the National Institutes of Health/NIDDK (to S.S.-C.). Part of the exome sequencing effort was performed by the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics (YCMG) funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (U54 HG006504 to R.P.L.).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Rik Westland.

Data curation: Dina F Ahram, Dacia Di Renzo, Ali G. Gharavi, Gian Marco Ghiggeri, Anna Jamry-Dziurla, Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Tze Y. Lim, Pierluigi Marzuillo, Giuseppe Masnata, Andrea Ranghino, Miguel Verbitsky, Dina F Ahram, Shumyle Alam, Daniele Alberti, Gerald B. Appel, Adela Arapović, Olga Baraldi, Monica Bodria, Andrew S. Bomback, Mario Bonomini, Yasar Caliskan, Pietro A. Canetta, Valentina P. Capone, Gianluca Caridi, Debanjana Chatterjee, Enrico Cocchi, David J. Cohen, Giovanni Conti, Dorota Drożdż, Pasquale Esposito, Enrico Fiaccadori, Carolina Finale, Loreto Gesualdo, Gian Marco Ghiggeri, Mario Giordano, Barbara Gnutti, Stefano Guarino, Zoran Gucev, Thomas Hays, Claudia Izzi, Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Byum Hee Kil, Krzysztof Kiryluk, Grażyna Krzemień, Gaetano La Manna, Sarah Lambert, Claudio La Scola, Anna Latos-Bielenska, Tze Y. Lim, Fangming Lin, Vladimir J. Lozanovski, Valeria Manca, Shrikant Mane, Maddalena Marasa, Marida Martino, Anna Materna-Kiryluk, James McKiernan, Monika Miklaszewska, Adele Mitrotti, Malgorzata Mizerska-Wasiak, Giovanni Montini, William Morello, Jordan G. Nestor, Alessandro Pezzutto, Isabella Pisani, Stacy E. Piva, Jai Radhakrishnan, Maya K. Rao, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Domenico Santoro, Marijan Saraga, Gianfranco Savoldi, Francesco Scolari, Przemysław Sikora, Maria Szczepanska, Agnieszka Szmigielska, Velibor Tasic, Francesco Tondolo, Natalie S. Uy, Miguel Verbitsky, Rik Westland, Joanna A.E. van Wijk, Marcin Zaniew, Jun Y. Zhang, Lada Zibar.

Formal analysis: Dina F Ahram, Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Tze Y. Lim, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Rik Westland.

Funding acquisition: Simone Sanna-Cherchi.

Investigation: Dina F Ahram, Ali G. Gharavi, Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Tze Y. Lim, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Rik Westland.

Methodology: Dina F Ahram, Ali G. Gharavi:, Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Richard P. Lifton, Tze Y. Lim, Shrikant Mane, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Miguel Verbitsky, Rik Westland.

Project administration: Simone Sanna-Cherchi.

Supervision: Simone Sanna-Cherchi.

Writing – original draft: Gina Jin, Juntao Ke, Tze Y. Lim, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Rik Westland.

Writing – review & editing: Dina F Ahram, Shumyle Alam, Gerald B. Appel, Adela Arapović, Olga Baraldi, Monica Bodria, Andrew S. Bomback, Mario Bonomini, Yasar Caliskan, Pietro A. Canetta, Valentina P. Capone, Gianluca Caridi, Debanjana Chatterjee, Enrico Cocchi, David J. Cohen, Giovanni Conti, Dorota Drożdż, Pasquale Esposito, Enrico Fiaccadori, Carolina Finale, Loreto Gesualdo, Ali G. Gharavi, Gian Marco Ghiggeri, Mario Giordano, Stefano Guarino, Zoran Gucev, Thomas Hays, Byum Hee Kil, Krzysztof Kiryluk, Grażyna Krzemień, Gaetano La Manna, Sarah Lambert, Claudio La Scola, Anna Latos-Bielenska, Richard P. Lifton, Fangming Lin, Vladimir J. Lozanovski, Valeria Manca, Shrikant Mane, Maddalena Marasa, Marida Martino, Anna Materna-Kiryluk, James McKiernan, Monika Miklaszewska, Adele Mitrotti, Malgorzata Mizerska-Wasiak, Giovanni Montini, William Morello, Jordan G. Nestor, Alessandro Pezzutto, Isabella Pisani, Stacy E. Piva, Jai Radhakrishnan, Maya K. Rao, Simone Sanna-Cherchi, Domenico Santoro, Marijan Saraga, Gianfranco Savoldi, Francesco Scolari, Przemysław Sikora, Maria Szczepanska, Agnieszka Szmigielska, Velibor Tasic, Natalie S. Uy, Miguel Verbitsky, Rik Westland, Joanna A.E. van Wijk, Marcin Zaniew, Jun Y. Zhang, Lada Zibar.

Data Sharing Statement

All authors approve adherence to the FAIR data principles. There are some restrictions for these data as follows: Data sharing is possible on the basis of anonymity Exome sequencing data are available in dbgap submitted as part of the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics (YCMG).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/E403 and http://links.lww.com/JSN/E404.

Supplemental Figure 1. Analytical workflow for SNV and CNV analyses of the study cohort.

Supplemental Figure 2. Genetically determined ancestry proportions of the study cohort.

Supplemental Figure 3. Overall diagnostic yield in each COU subcategory.

Supplemental Table 1. List of 382 prioritized genes for developmental defects of the kidney and urinary tract (Excel file).

Supplemental Table 2. Ultrarare SNVs of uncertain significance identified in genes with an autosomal dominant inheritance (Excel file).

Supplemental Table 3. Rare structural variants of uncertain significance. (Excel file).

References

- 1.Jackson AR, Ching CB, McHugh KM, Becknell B. Roles for urothelium in normal and aberrant urinary tract development. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17(8):459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0348-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westland R, Renkema KY, Knoers NV. Clinical integration of genome diagnostics for congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;16(1):128–137. doi: 10.2215/CJN.14661119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garne E, Loane M, Wellesley D, Barisic I; Eurocat Working Group. Congenital hydronephrosis: prenatal diagnosis and epidemiology in Europe. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Short KM, Smyth IM. The contribution of branching morphogenesis to kidney development and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):754–767. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantini F. Genetic controls and cellular behaviors in branching morphogenesis of the renal collecting system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2012;1(5):693–713. doi: 10.1002/wdev.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgas KM, Armstrong J, Keast JR, et al. An illustrated anatomical ontology of the developing mouse lower urogenital tract. Development. 2015;142(10):1893–1908. doi: 10.1242/dev.117903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viana R, Batourina E, Huang H, et al. The development of the bladder trigone, the center of the anti-reflux mechanism. Development. 2007;134(20):3763–3769. doi: 10.1242/dev.011270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capone V, Persico N, Berrettini A, et al. Definition, diagnosis and management of fetal lower urinary tract obstruction: consensus of the ERKNet CAKUT-Obstructive Uropathy Work Group. Nat Rev Urol. 2022;19(5):295–303. doi: 10.1038/s41585-022-00563-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan K, Ahram DF, Liu YP, et al. Multidisciplinary approaches for elucidating genetics and molecular pathogenesis of urinary tract malformations. Kidney Int. 2022;101(3):473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesnaye NC, van Stralen KJ, Bonthuis M, Harambat J, Groothoff JW, Jager KJ. Survival in children requiring chronic renal replacement therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(4):585–594. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3681-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wuhl E, van Stralen KJ, Verrina E, et al. Timing and outcome of renal replacement therapy in patients with congenital malformations of the kidney and urinary tract. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(1):67–74. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03310412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanna-Cherchi S, Ravani P, Corbani V, et al. Renal outcome in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2009;76(5):528–533. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen HT, Herndon CA, Cooper C, et al. The Society for Fetal Urology consensus statement on the evaluation and management of antenatal hydronephrosis. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6(3):212–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.02.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanna-Cherchi S, Westland R, Ghiggeri GM, Gharavi AG. Genetic basis of human congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(1):4–15. doi: 10.1172/jci95300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avanoglu A, Tiryaki S. Embryology and Morphological (Mal)Development of UPJ. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:137. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verbitsky M, Westland R, Perez A, et al. The copy number variation landscape of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Nat Genet. 2019;51(1):117–127. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0281-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Rivera E, Liu YP, Verbitsky M, et al. Genetic drivers of kidney defects in the DiGeorge syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):742–754. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1609009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolaou N, Pulit SL, Nijman IJ, et al. Prioritization and burden analysis of rare variants in 208 candidate genes suggest they do not play a major role in CAKUT. Kidney Int. 2016;89(2):476–486. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westland R, Verbitsky M, Vukojevic K, et al. Copy number variation analysis identifies novel CAKUT candidate genes in children with a solitary functioning kidney. Kidney Int. 2015;88(6):1402–1410. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanna-Cherchi S, Kiryluk K, Burgess K, et al. Copy-number disorders are a common cause of congenital kidney malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(6):987–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verbitsky M, Krithivasan P, Batourina E, et al. Copy number variant analysis and genome-wide association study identify loci with large effect for vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(4):805–820. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verbitsky M, Sanna-Cherchi S, Fasel DA, et al. Genomic imbalances in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):2171–2178. doi: 10.1172/jci80877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren Z, Povysil G, Hostyk JA, Cui H, Bhardwaj N, Goldstein DB. ATAV: a comprehensive platform for population-scale genomic analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):D980–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, et al. Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):142–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(4):877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fromer M, Purcell SM. Using XHMM software to detect copy number variation in whole-exome sequencing data. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2014;81:7.23.1–7.23.21. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0723s81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill PS, Rosenblum ND. Control of murine kidney development by sonic hedgehog and its GLI effectors. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(13):1426–1430. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.13.2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway: new concepts of activation. Biol Cell. 2001;93(1-2):53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(01)01125-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC, Kyriakos M. Differential susceptibility of strain 2 and strain 13 Guinea pigs to induction of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 1975;114(1_Part_2):371–373. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.114.1_part_2.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, et al. Mild recessive mutations in six Fraser syndrome-related genes cause isolated congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):1917–1922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gbadegesin RA, Brophy PD, Adeyemo A, et al. TNXB mutations can cause vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(8):1313–1322. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gauthier J, Ouled Amar Bencheikh B, Hamdan FF, et al. A homozygous loss-of-function variant in MYH11 in a case with megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(9):1266–1268. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer E, Zaloszyc A, Lauer J, et al. Mutations in SDCCAG8/NPHP10 cause Bardet-Biedl syndrome and are associated with penetrant renal disease and absent polydactyly. Mol Syndromol. 2011;1(6):273–281. doi: 10.1159/000331268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badiner N, Taylor S, Forlenza K, et al. Mutations in DYNC2H1, the cytoplasmic dynein 2, heavy chain 1 motor protein gene, cause short-rib polydactyly type I, Saldino-Noonan type. Clin Genet. 2017;92(2):158–165. doi: 10.1111/cge.12947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elahi S, Homstad A, Vaidya H, et al. Rare variants in tenascin genes in a cohort of children with primary vesicoureteric reflux. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(2):247–253. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3203-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vivante A, Kleppa MJ, Schulz J, et al. Mutations in TBX18 cause dominant urinary tract malformations via transcriptional dysregulation of ureter development. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(2):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mefford HC, Sharp AJ, Baker C, et al. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(16):1685–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q, Zhang J, Wang H, Feng Q, Luo F, Xie J. Compound heterozygous variants in MYH11 underlie autosomal recessive megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome in a Chinese family. J Hum Genet. 2019;64(11):1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0651-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert MA, Schultz-Rogers L, Rajagopalan R, et al. Protein-elongating mutations in MYH11 are implicated in a dominantly inherited smooth muscle dysmotility syndrome with severe esophageal, gastric, and intestinal disease. Hum Mutat. 2020;41(5):973–982. doi: 10.1002/humu.23986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong W, Baldwin C, Choi J, et al. Identification of a dominant MYH11 causal variant in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: results of whole-exome sequencing. Clin Genet. 2019;96(5):473–477. doi: 10.1111/cge.13617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanna-Cherchi S, Khan K, Westland R, et al. Exome-wide association study identifies GREB1L mutations in congenital kidney malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(5):789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munch J, Engesser M, Schonauer R, et al. Biallelic pathogenic variants in roundabout guidance receptor 1 associate with syndromic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2022;101(5):1039–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Izzi C, Dordoni C, Econimo L, et al. Variable expressivity of HNF1B nephropathy, from renal cysts and diabetes to medullary sponge kidney through tubulo-interstitial kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(12):2341–2350. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanna-Cherchi S, Sampogna R, Papeta N, et al. Mutations in DSTYK and dominant urinary tract malformations. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):621–629. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1214479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn YH, Lee C, Kim NKD, et al. Targeted exome sequencing provided comprehensive genetic diagnosis of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):751. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rasmussen M, Sunde L, Nielsen M, et al. Targeted gene sequencing and whole-exome sequencing in autopsied fetuses with prenatally diagnosed kidney anomalies. Clin Genet. 2018;93(4):860–869. doi: 10.1111/cge.13185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heidet L, Moriniere V, Henry C, et al. Targeted exome sequencing identifies PBX1 as involved in monogenic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(10):2901–2914. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Kohl S, et al. Mutations in 12 known dominant disease-causing genes clarify many congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2014;85(6):1429–1433. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knuppel T, et al. Prevalence of mutations in renal developmental genes in children with renal hypodysplasia: results of the ESCAPE study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J, Zhang J, Chen W, Xiong L, Huang X, Ye X. Crossing vessels with suspension versus transposition in laparoscopic pyeloplasty of patients with ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a retrospective study. BMC Urol. 2021;21(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12894-021-00846-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishi K, Uemura O, Harada R, et al. ; Pediatric CKD Study Group in Japan in conjunction with the Committee of Measures for Pediatric CKD of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Early predictive factors for progression to kidney failure in infants with severe congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38(4):1057–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05703-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milo Rasouly H, Aggarwal V, Bier L, Goldstein DB, Gharavi AG. Cases in precision medicine: genetic testing to predict future risk for disease in a healthy patient. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):540–547. doi: 10.7326/m20-5713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knoers N, Antignac C, Bergmann C, et al. Genetic testing in the diagnosis of chronic kidney disease: recommendations for clinical practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(2):239–254. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All authors approve adherence to the FAIR data principles. There are some restrictions for these data as follows: Data sharing is possible on the basis of anonymity Exome sequencing data are available in dbgap submitted as part of the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics (YCMG).