Abstract

Heterogeneity of the cingulate cortex is evident in multiple dimensions including anatomy, function, connectivity, and involvement in networks and diseases. Using the recently developed functional connectivity gradient approach and resting-state functional MRI data, we found three functional connectivity gradients that captured distinct dimensions of cingulate hierarchical organization. The principal gradient exhibited a radiating organization with transitions from the middle toward both anterior and posterior parts of the cingulate cortex and was related to canonical functional networks and corresponding behavioral domains. The second gradient showed an anterior–posterior axis across the cingulate cortex and had prominent geometric distance dependence. The third gradient displayed a marked differentiation of subgenual and caudal middle with other parts of the cingulate cortex and was associated with cortical morphology. Aside from providing an updated framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of cingulate heterogeneity, the observed hierarchical organization of the cingulate cortex may constitute a novel research agenda with potential applications in basic and clinical neuroscience.

Subject terms: Computational neuroscience, Cognitive neuroscience

Analysis of resting-state fMRI data reveals the presence of functional connectivity gradients of the human cingulate cortex, which updates our understanding of cingulate heterogeneity.

Introduction

The cingulate cortex, which hooks around the corpus callosum, is a key component of the limbic system1,2. This uniquely located structure has been segmented into anatomically heterogeneous subregions that show distinct cytoarchitectonic, functional, and connectivity features3–11. It is generally accepted that the cingulate cortex subserves a rich range of functions like emotion, action, and memory2,12–18, which arises from its widespread structural and functional connectivity with both cortical and subcortical areas3,7,11,18. Indeed, neuroimaging data in humans have revealed the crucial role of different cingulate subregions as major hubs anchoring multiple large-scale brain networks, such as default mode (dorsal posterior cingulate cortex), salience (dorsal anterior cingulate cortex), executive control (anterior middle cingulate cortex), and visceromotor (subgenual anterior cingulate cortex) networks15,16,19–25. Furthermore, extensive clinical neuroimaging research has exposed the cingulate cortex as a core brain region preferentially affected in various neuropsychiatric conditions26–40, but with the exact location and nature of cingulate abnormalities varying across disorders. Collectively, these previous findings in basic and clinical neuroscience have highlighted the substantial heterogeneity of the cingulate cortex in multiple dimensions including anatomy, function, connectivity, and involvement in networks and diseases. However, an updated framework for a unified understanding of such heterogeneity is yet to be established.

There is increasing and converging evidence pointing to the presence of a hierarchy in multiscale brain organization, which is reflected in structure, function, connectivity, and gene expression41–54. To characterize the hierarchical organization of the brain, researchers have recently applied dimensionality reduction techniques to high-dimensional resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) data from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) to derive a parsimonious set of principal components that are able to capture continuous transitions as well as overarching spatial relationships of rsFC patterns across brain locations, referred to as functional connectivity gradients55–57. Several prior attempts, working within this framework, have been made to recapitulate meaningful hierarchical principles (e.g., from primary to transmodal areas) of macroscale organization in multiple brain structures, such as the cerebral cortex51, primary somatosensory cortex58, angular gyrus59, insula60,61, thalamus54, hippocampus42, striatum41, and cerebellum52. Moreover, some functional connectivity gradients have shown correspondence with canonical functional networks, involvement in specific behavioral domains, association with intrinsic geometry, and underlying structural basis (i.e., spatial correlations with structural measures like gray matter volume [GMV] and cortical thickness)51,54,58. Despite intense interest in the recent literature, there is a dearth of investigations taking advantage of the functional connectivity gradient approach to examine the hierarchical organization of the cingulate cortex, clarification of which may yield an updated framework for understanding cingulate heterogeneity.

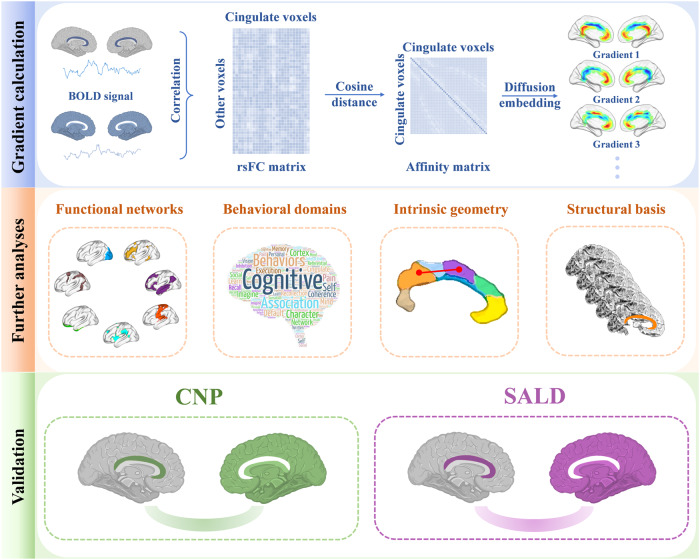

To address this challenge, we utilized rs-fMRI data of 793 healthy subjects from three independent datasets to discover and validate functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex, which were computed based on the voxel-wise cingulate cortex-to-cerebrum rsFC profiles. Next, we carried out a range of further analyses to investigate the associations of cingulate functional connectivity gradients with canonical functional networks, behavioral domains, intrinsic geometry, and cortical morphology. A schematic overview of the research design and analytical procedure is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Research design and analytical procedure.

Top panel: gradient calculation. We obtained rs-fMRI data from a large discovery sample of 361 healthy subjects. Functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex were computed based on the voxel-wise cingulate cortex-to-cerebrum rsFC profiles using diffusion embedding. We focused our analyses on the first several gradients that accounted for the greater variance in connectivity. Middle panel: further analyses. We investigated the associations of cingulate functional connectivity gradients with canonical functional networks, behavioral domains, intrinsic geometry, and cortical morphology. Bottom panel: validation. The robustness of our findings was verified in two independent cross-race, cross-scanner validation datasets (cross-race CNP and cross-scanner SALD). BOLD blood-oxygen-level-dependent, rsFC resting-state functional connectivity, CNP Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics, SALD Southwest University Adult Lifespan Dataset, rs-fMRI resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Results

Functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex

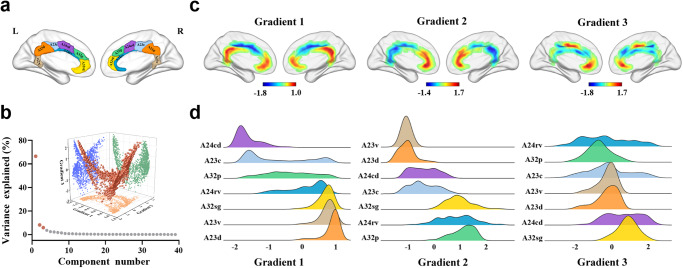

The variability in cingulate rsFC patterns explained by the functional connectivity gradients is shown in descending order (Fig. 2b). The principal gradient (gradient 1) accounted for the greatest 66.42% of the variance in connectivity, the second gradient (gradient 2) 8.13%, and the third gradient (gradient 3) 5.81%. Scatter plots demonstrated the distributions of gradients 1–3 of all cingulate voxels (Fig. 2b). The topographies of cingulate functional connectivity gradients are presented in Fig. 2c, d. Gradient 1 exhibited a radiating organization, characterized by transitions from the middle (A24cd and A23c) toward both anterior (A32sg) and posterior (A23v and A23d) parts of the cingulate cortex. Gradient 2 showed an anterior–posterior axis across the cingulate cortex, manifested as a gradual change from the anterior (A32sg, A24rv, and A32p) to the posterior (A23v and A23d) portion. Gradient 3 displayed a marked differentiation of subgenual (A32sg) and caudal middle (A24cd) with other parts of the cingulate cortex.

Fig. 2. Functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex.

a Illustration of cingulate subregions. b Connectivity variance explained by the functional connectivity gradients and inserted scatter plots of the first three gradients. The three-dimensional scatter plot shows the distributions of gradients 1–3 of all cingulate voxels and is projected into three two-dimensional scatter plots showing the distributions of any pair of the three gradients. c Topographies of the first three cingulate functional connectivity gradients. d Distributions of cingulate subregions along the first three gradients. L left, R right, A23v ventral area 23, A23d dorsal area 23, A23c caudal area 23, A24cd caudodorsal area 24, A24rv rostroventral area 24, A32p pregenual area 32, A32sg subgenual area 32.

Relevance to functional networks

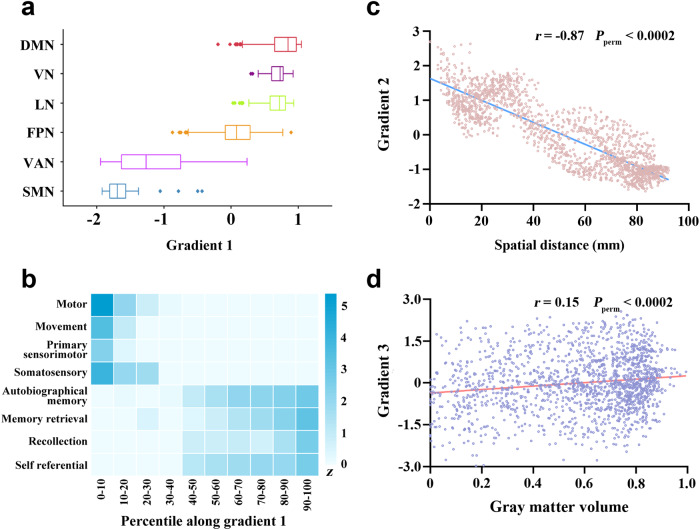

The cingulate functional atlas created using a combination of the winner-take-all method and the seven-network parcellation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The cingulate functional subdivisions corresponding to the canonical functional networks were not randomly distributed along gradient 1, but rather tended to cluster at similar positions (Fig. 3a). Importantly, the functional subdivision corresponding to the sensorimotor network occupied one extreme position along gradient 1 and was maximally separated from that corresponding to the default mode network at the other extreme. By contrast, the distributions of the functional networks along gradients 2 and 3 were random and overlapping (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 3. Relationships of cingulate functional connectivity gradients with functional networks, behavioral domains, intrinsic geometry, and gray matter volume.

a Box plots showing distributions of the cingulate functional subdivisions corresponding to the canonical functional networks along gradient 1. The functional subdivision corresponding to the dorsal attention network was not found. b Associations of cingulate gradient 1 with behavioral terms from the NeuroSynth. To establish a link between gradient and behavior, the gradient map was binned into ten-percentile increments and then binarized, yielding 10 binary masks ranging from 0–10% to 90–100%. For each behavioral term, the average z-statistics within the 10 masks were extracted. c A scatter plot of the association of gradient 2 with spatial distance from the maximal gradient location in the cingulate cortex. d A scatter plot of the spatial correlation between cingulate gradient 3 and gray matter volume. DMN default mode network, VN visual network, LN limbic network, FPN frontoparietal network, VAN ventral attention network, SMN sensorimotor network.

Relevance to behavioral domains

The behavioral relevance of cingulate gradient 1 was analyzed with the use of the NeuroSynth, which brought forward an important observation echoing the aforementioned result of functional network analysis. The end implicating the sensorimotor network was linked to behavioral terms depicting somatic movement and sensation such as “motor”, “movement”, “primary sensorimotor” and “somatosensory”, whereas the other end involving the default mode network was related to terms describing abstract cognition such as “self referential”, “recollection”, “memory retrieval” and “autobiographical memory” (Fig. 3b). In addition, behavioral relevance analysis demonstrated a systematic shift in behavioral terms from emotion (e.g., “reward” and “affective”) to memory (e.g., “autobiographical memory” and “episodic memory”) along gradient 2 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Relevance to intrinsic geometry

Cross-voxel Pearson’s correlation analysis demonstrated a significant negative association between gradient 2 and spatial distance from the maximal gradient location in the cingulate cortex (r = −0.87, Pperm < 0.0002) (Fig. 3c). However, this negative association was not present for either gradient 1 (r = 0.14, Pperm < 0.0002) or gradient 3 (r = 0.21, Pperm < 0.0002). This result indicated that gradient 2, but not gradients 1 and 3, showed geometric distance dependence.

Relevance to gray matter volume

Spatial correlation analysis revealed a significant positive association between gradient 3 and GMV in the cingulate cortex (r = 0.15, Pperm < 0.0002) (Fig. 3d). However, the spatial correlations became relatively weak for gradient 1 (r = 0.06, Pperm = 0.007) and nonsignificant for gradient 2 (r = −0.0006, Pperm = 0.49). This observation suggested a structural basis of gradient 3 rather than gradients 1 and 2.

Validation analyses

The results of validation analyses supported the robustness of our findings to different samples and methodological variations. First, cingulate functional connectivity gradients derived from two independent validation datasets (cross-race CNP and cross-scanner SALD) were similar to those from the discovery dataset (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Additionally, relationships of the cingulate functional connectivity gradients with functional networks, behavioral domains, intrinsic geometry, and gray matter volume were largely preserved (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Second, when thresholding the rsFC matrix with two other thresholds (top 20% and 30%), we found that the resultant functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex were nearly identical to those using the threshold of top 10% (Supplementary Fig. 8). Third, analyzing BOLD data with GSR yielded cingulate functional connectivity gradients consistent with those in our main analysis of BOLD data without GSR (Supplementary Fig. 9). Fourth, functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex calculated based on the group-level rsFC matrix by averaging individual-level rsFC matrices across subjects were similar to those in our main analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10). Fifth, cingulate functional connectivity gradients derived from BOLD data preprocessed by CompCor were identical to our original results (Supplementary Fig. 11). Finally, analyses based on the voxel-wise cingulate cortex-to-cerebrum (including the cingulate cortex) rsFC matrix generated consistent cingulate functional connectivity gradients (Supplementary Fig. 12). Furthermore, we showed the spatial correlation coefficients between cingulate functional connectivity gradients in the main analysis and those in the above-described validation analyses (Supplementary Fig. 13), which also corroborated the robustness of our results in a quantitative manner.

Discussion

The current study utilized the discovery and validation of rs-fMRI datasets, coupled with the application of the novel functional connectivity gradient approach, to comprehensively investigate the hierarchical organization of the cingulate cortex. Our data revealed three functional connectivity gradients that captured distinct dimensions of cingulate macroscale organization. The principal gradient exhibited a radiating organization with transitions from the middle toward both anterior and posterior parts of the cingulate cortex; moreover, cingulate functional subdivisions corresponding to canonical functional networks (behavioral domains) were distributed along the principal gradient in a hierarchical manner, i.e., from the sensorimotor network (somatic movement and sensation) at one end to the default mode network (abstract cognition) at the other end. The second gradient showed an anterior–posterior axis across the cingulate cortex and had prominent geometric distance dependence. The third gradient displayed a marked differentiation of subgenual and caudal middle with other parts of the cingulate cortex and was associated with cortical morphology.

The high-dimensional nature of brain data lies in the fact that each brain location typically has more than one feature, such as functional coactivation, anatomical and functional connectivity, regional macro- and micro-structure, gene or receptor expression, and particularly multimodal integrative features62,63. In this context, dimensionality reduction approaches are warranted to extract intelligible information from such high-dimensional brain data. One frequently used segmentation method makes use of clustering algorithms to group brain locations into larger parcels based on the similarity of their features, such that brain locations sharing similar features were clustered and each cluster is assumed to represent a homogeneous region. Nonetheless, in light of the discordance in the number of cingulate subregions reported across previous parcellation studies3,64,65, no consensus has been reached yet on how many subdivisions comprise the cingulate cortex. As such, it is argued that treating subregions as independent and discrete entities may fall short of capturing more continuous changes and overarching spatial arrangement of cingulate features. Instead, the newly proposed gradient approach identifies the main axes of variance in the brain data via decomposition or embedding techniques and replaces the original high dimensions of brain features with a more parsimonious set of new dimensions (i.e., gradients) that account for most of the feature variance. Each gradient is a continuous representation of one facet of brain topographical organization and each brain location can be depicted by a value reflective of where it falls along this continuum51,52. There is rapidly growing awareness that the spatial relationships of brain locations along these gradients are not arbitrary, but rather a consequence of developmental mechanisms shaped by evolutionary selection46. Together, a gradient-based rather than cluster-based conceptualization may advance our understanding of the hierarchical organization of cingulate connectivity.

By applying the functional connectivity gradient approach to rsFC data from rs-fMRI, we found that the cingulate principal gradient, explaining the greatest connectivity variance, exhibited a radiating organization with transitions from the middle toward both anterior and posterior parts of the cingulate cortex. Further analysis of functional networks demonstrated that cingulate functional subdivisions corresponding to canonical functional networks were distributed along the principal gradient in a hierarchical fashion, i.e., from the sensorimotor network at one extreme to the default mode network at the other extreme. Nevertheless, the distributions of the functional networks along the second and third gradients were random and overlapping. These inconclusive patterns may be attributable to the limited functional roles of the cingulate cortex, which cannot be reflected in functional connectivity gradients as diverse as the cerebral cortex51. The parallel analysis of behavioral domains confirmed the results of functional network analysis by showing a network-behavior correspondence. Indeed, the principal gradient of the cingulate cortex reflects a well-established functional hierarchy from primary to transmodal processing that is also observable in the cerebral cortex51 and cerebellum52, suggesting that this central principle exists not only in the whole brain but also in individual brain structures. In addition, our observations are largely coherent with prior findings that the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex are connected more to the prefrontal and parietal cortical areas and thus are associated with high-order cognition, whereas the middle cingulate cortex is more connected to the sensorimotor areas and thus is linked with low-order sensorimotor processes10,13,16,18,65–67.

The second gradient showed an anterior–posterior axis across the cingulate cortex. There is evidence that the anterior cingulate cortex receives information from the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala and is primarily involved in emotion, whereas the posterior cingulate cortex has outputs to the hippocampal system and is predominantly implicated in memory2. Our behavioral relevance analysis also demonstrated a systematic shift in behavioral terms from emotion to memory along the second gradient. These findings jointly work to indicate that the second gradient may contribute to the differentiation between emotion and memory in the cingulate cortex. Remarkably, this gradient had significant geometric distance dependence with the lower gradient location being further away from the maximal gradient location. This observation, taken with earlier reports of similar gradient-geometric distance associations in the thalamus and primary somatosensory cortex54,58, suggests a common feature of the topographic layouts mapped by functional connectivity gradients. The third gradient displayed a marked distinction between the subgenual and caudal middle with other parts of the cingulate cortex. Previous studies have proved that the subgenual and middle cingulate cortex participates in the visceromotor system that modulates the regulation of the autonomic nervous system as well as of the hormonal and immune systems68–70. Visceromotor control signals are thought to descend from the deep layers of the subgenual and middle cingulate cortex to subcortical and brain stem nuclei, which proceed to the spinal cord to coordinate and regulate the body’s internal systems68. In conjunction with the previous evidence, our data imply the prominent role of the third gradient in visceromotor function. Moreover, the weak but statistically significant positive association between this gradient and GMV endorses the well-defined notion that brain function is shaped, but not limited, by the underlying anatomy71–75. In combination, our findings corroborate the heterogeneous nature of the cingulate cortex. Of more importance, the present work accommodates overlapped spatial distribution and gradual transitions of the cingulate hierarchical organization, complementing and extending prior parcellation investigations in an elegant manner.

Our results should be interpreted in view of a few limitations. First, despite recent evidence of hemispheric differences in gradient organization76–78, we found nearly identical cingulate functional connectivity gradients in the two hemispheres, suggesting that the cingulate gradients may be symmetric in nature. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that our rs-fMRI data had a low spatial resolution, limiting our ability to differentiate BOLD signals of the left and right cingulate cortex located in the midline of the brain. Therefore, high-resolution fMRI techniques will be utilized to examine hemispheric differences in cingulate gradient organization in future studies. Second, it is well known that the cingulate cortex has extensive connectivity with not only the cerebrum but also the cerebellum79,80. Since the rs-fMRI field-of-view did not include the entire cerebellum in all subjects, we calculated functional connectivity gradients of the cingulate cortex based on its rsFC to the cerebrum, leaving the effects of cingulate cortex-to-cerebellum rsFC on the functional connectivity gradients elusive. Third, we focused our analyses on the first three gradients that accounted for the greater connectivity variance. This may overlook some neurobiologically relevant functional connectivity gradients with smaller explained variance, thereby limiting the ability to achieve a more thorough characterization of the cingulate hierarchical organization. However, the explained variance of the other cingulate functional connectivity gradients was similar to each other, making it challenging to distinguish them. Fourth, to obtain more stable and reliable results, we computed the cingulate functional connectivity gradients at the group level rather than at the individual level, which may obscure meaningful individual variation. Finally, our discovery dataset and the two validation datasets included only right-handed participants, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to the general population. Examining cingulate functional connectivity gradients in left-handed participants will be part of our future investigations.

In summary, employing large-scale discovery and validation rs-fMRI datasets, we established three functional connectivity gradients that captured distinct dimensions of cingulate hierarchical organization. Aside from providing an updated framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of cingulate heterogeneity, the observed hierarchical organization of the cingulate cortex may constitute a novel research agenda with potential applications in basic and clinical neuroscience. In one view, the presented framework might offer useful approaches and testable questions to the investigation of cingulate function and anatomy in research settings. More generally, the prominent involvement of cingulate abnormalities in many neuropsychiatric disorders suggests that these functional connectivity gradients could open new opportunities to refine our understanding of the role of the cingulate cortex in disease mechanisms.

Methods

Participants

Our study included a discovery dataset as well as two independent cross-race and cross-scanner validation datasets. Note that race was taken into account because there is evidence of race differences in brain functional connectivity81–83. The discovery participants were healthy adults of Chinese Han and right-handedness, enrolled from the local universities and community through poster advertisements. Exclusion criteria included neuropsychiatric or severe somatic disorder, a history of head injury with consciousness loss, pregnancy, MRI contraindications, and a family history of psychiatric illness among first-degree relatives. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they had been given a complete description of the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The validation samples were from two publically available datasets: Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics (CNP, https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds000030/versions/1.0.0)84 and Southwest University Adult Lifespan Dataset (SALD, 10.15387/fcp_indi.sald)85. It is noteworthy that we only selected healthy adults from the cross-disorder CNP dataset. Full details about the two validation samples (e.g., ethics, informed consent, inclusion and exclusion criteria, among others) have been provided in the data descriptor literature84,85. To exclude the potential impact of neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration, all the participants were restricted to an age range of 18–60 years. In addition, we excluded participants with poor image quality (e.g., visible artifacts [e.g., ghosting artifacts arising from subject movement and pulsating large arteries, metal artifacts, susceptibility artifacts, and blooming artifacts], organic lesions [e.g., tumor, stroke, and lacuna], and incomplete brain coverage) or excessive head motion during scanning (i.e., maximum translation or rotation > 2 mm or 2°). This brought the final samples to 361 in the discovery dataset, 103 in the cross-race CNP dataset, and 329 in the cross-scanner SALD dataset. Details of the demographic data of the three datasets are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Image acquisition

MRI data of the discovery sample were acquired using the 3.0-Tesla General Electric Discovery MR750w scanner, and those of the validation samples were obtained using the 3.0-Tesla Siemens Trio scanners. Details of the resting-state fMRI protocols for the three datasets are described in Supplementary Table 2.

fMRI data preprocessing

Resting-state blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) data were preprocessed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and Data Processing & Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI, http://rfmri.org/dpabi)86. The first several time points (discovery: 10, CNP: 5, SALD: 10) for each participant were discarded to allow the signal to reach equilibrium and the participants to adapt to the scanning noise. The remaining volumes were corrected for the acquisition time delay between slices. Then, realignment was performed to correct the motion between time points. Head motion parameters were assessed by calculating the translation in each direction and the angular rotation on each axis for each volume. All BOLD data of the final sample were within the defined motion thresholds (i.e., maximum translation or rotation < 2 mm or 2°). We also computed frame-wise displacement (FD), which measures the volume-to-volume changes in head position. Several nuisance covariates (the linear drift, the estimated motion parameters based on the Friston-24 model, the spike volumes with FD > 0.5 mm, the white matter signal, and the cerebrospinal fluid signal) were regressed out from the data. The datasets were then band-pass filtered using a frequency range of 0.01 to 0.1 Hz. In the normalization step, individual structural images were firstly co-registered with the average functional images; then the transformed structural images were segmented and normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using a high-level nonlinear warping algorithm, that is, the diffeomorphic anatomical registration through the exponentiated Lie algebra (DARTEL) technique87. Finally, each filtered functional volume was spatially normalized to the MNI space using the deformation parameters estimated during the above step and resampled into a 3-mm cubic voxel.

Calculation of cingulate functional connectivity gradients

Calculation of cingulate functional connectivity gradients was predicated on its rsFC to the entire cerebrum (Fig. 1). First, the Human Brainnetome Atlas was utilized to define the cingulate cortex (1665 voxels) including dorsal area 23 (A23d), rostroventral area 24 (A24rv), pregenual area 32 (A32p), ventral area 23 (A23v), caudodorsal area 24 (A24cd), caudal area 23 (A23c) and subgenual area 32 (A32sg) (Fig. 2a). It is noteworthy that this brain atlas was constructed using a connectivity-based parcellation framework88. That said, brain regions were initially parcellated based on the connectional architecture mapped with probabilistic tractography using diffusion MRI, and were further validated using resting-state functional connectivity, tractography-based anatomical connectivity, and meta-analysis-based functional behavioral decoding. Second, the preprocessed BOLD images were concatenated across all subjects after standardization using z-scores, resulting in group-level BOLD time courses. Third, based on the group-level BOLD time courses, a voxel-wise cingulate cortex-to-cerebrum rsFC matrix (1665 × 39780) was generated by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients between time courses of each voxel within the cingulate cortex and each voxel within the cerebrum (excluding the cingulate cortex), followed by Fisher’s Z-transformation to improve normality. Then, we thresholded the rsFC matrix with the top 10% of connections per row retained, whereas all others were zeroed42,51,52,89,90. Fourth, we used cosine distance to generate a positive and symmetric affinity matrix reflecting the similarity of connectivity profiles between each pair of cingulate voxels.

Cingulate functional connectivity gradients were calculated using diffusion embedding51,91 implemented in BrainSpace, a Python/Matlab toolbox (https://github.com/MICA-MNI/BrainSpace)57. Diffusion embedding is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction technique that can recover a low-dimensional embedding from high-dimensional connectivity data. In the embedding space, voxels that are strongly connected by either many connections or few very strong connections are close, whereas voxels with little or no connections are far apart51,90. In comparison with other dimensionality reduction algorithms, diffusion embedding is relatively robust to noise, computationally inexpensive, and provides a stable representation of connections92. By applying this algorithm to the affinity matrix, we identified multiple low-dimensional gradients explaining connectivity variance in descending order. For each gradient, a value was assigned to each voxel within the cingulate cortex, yielding a cingulate map reflective of the gradient topography to visualize macroscale continuous transitions in overall connectivity patterns. We focused our analyses on the first several gradients that accounted for the greater variance in connectivity. Notably, the diffusion embedding is controlled by a single parameter α, which controls the influence of the density of sampling points on the underlying manifold (α = 0, maximal influence; α = 1, no influence). Following prior work51,52,89,90, we set α = 0.5 which is considered well-suited for the analysis of brain connectivity data.

Relevance to functional networks

To characterize the functional implications of cingulate gradients, we evaluated their associations with canonical functional networks from the seven-network parcellation93. A cingulate functional atlas was initially created with the use of a custom winner-take-all parcellation method54. That is, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the BOLD time course of a given voxel within the cingulate cortex and the average BOLD time course of each functional network. This cingulate voxel was then assigned to the functional network with the highest Pearson’s correlation coefficient. This procedure was repeated for all voxels within the cingulate cortex, resulting in a cingulate functional atlas including seven functional subdivisions corresponding to seven canonical functional networks. Finally, we extracted the gradient values of voxels within these cingulate functional subdivisions and sorted them by the median.

Relevance to behavioral domains

To capture the behavioral relevance of cingulate functional connectivity gradients, we investigated their associations with behavioral domains from the NeuroSynth (http://www.neurosynth.org), a well-validated and publicly available platform for large-scale automated synthesis of human neuroimaging data94. The NeuroSynth database provides activation (z-statistics) maps for a wide range of behavioral terms that describe conceptually distinct aspects of human behavior. To establish a link between gradient and behavior, each gradient map was binned into ten-percentile increments and then binarized, yielding 10 binary masks ranging from 0–10% to 90–100%. For each behavioral term, the average z-statistics within the 10 masks were extracted.

Relevance to intrinsic geometry

To investigate whether cingulate functional connectivity gradients were related to the intrinsic geometry of the cingulate cortex, we calculated the Euclidean distance between the peak voxel of each gradient map and the remaining voxels within the cingulate cortex, resulting in a Euclidean distance map per gradient. Then, cross-voxel Pearson’s correlation coefficient between each cingulate gradient map and the corresponding Euclidean distance map was calculated to index the extent to which each gradient changed with spatial distance from the maximal gradient location. Nonparametric permutation tests were pursued to determine the statistical significance of the correlations. Briefly, we randomly shuffled the voxels within the cingulate cortex 5000 times (i.e., 5000 permutations) and repeated gradient-distance correlations using the shuffled data. The gradient-distance correlation coefficient in each permutation was recorded to build a null distribution. Based on the null distribution, the P-value was calculated as the number of permutations that generated correlation coefficients greater than the true correlation coefficient/5000.

Relevance to gray matter volume

To determine the structural basis of cingulate functional connectivity gradients, we examined their relationships with GMV. The voxel-based morphology (VBM) approach was used to calculate GMV. First, all structural images were visually inspected to screen for artifacts or gross anatomical abnormalities; second, the structural images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid using the standard segmentation model; third, after initial affine registration into the MNI space, the gray matter concentration map was non-linearly warped using the DARTEL technique; finally, the GMV map was obtained by multiplying the gray matter concentration map by the nonlinear determinants derived from the spatial normalization step. Then, cross-voxel Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed to examine the spatial associations between functional connectivity gradients and group-averaged GMV within the cingulate cortex. The statistical significance of the associations was assessed using the abovementioned permutation testing (5000 permutations).

Validation analyses

We performed a series of validation analyses to verify the robustness of our results. First, our main analyses were conducted in the discovery dataset. To exclude the influence of samples, we also carried out the above-described analyses in two independent validation datasets (cross-race CNP and cross-scanner SALD). Second, before calculating the affinity matrix, we thresholded the rsFC matrix with the top 10% of connections per row retained. To examine the impact of threshold selections, we re-calculated cingulate functional connectivity gradients using two other thresholds (top 20% and 30%). Third, global signal regression (GSR) is a controversial step during the preprocessing of rs-fMRI data95. To test its potential effect, we reconstructed the rsFC matrix based on BOLD data with GSR and then re-computed cingulate functional connectivity gradients. Fourth, we adopted an alternative approach to calculate the group-level rsFC matrix for functional connectivity gradient analysis, i.e., computing individual-level rsFC matrices and then averaging them across all subjects. We repeated subsequent functional connectivity gradient analysis using the resultant group-level rsFC matrix. Fifth, given that component-based noise correction (CompCor) has been commonly used for the reduction of noise in fMRI data96, we re-calculated cingulate functional connectivity gradients based on BOLD data preprocessed by CompCor with the top 5 components regressed out. Finally, we re-computed cingulate functional connectivity gradients based on the voxel-wise cingulate cortex-to-cerebrum (including the cingulate cortex) rsFC matrix.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical tests used, sample sizes, and the number of replicates are described in the corresponding methods.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82071905), the Outstanding Youth Support Project of Anhui Province Universities (grant number: gxyqZD2022026), the Scientific Research Key Project of Anhui Province Universities (grant number: 2022AH051135), the Scientific Research Foundation of Anhui Medical University (grant number: 2022xkj143), and the Anhui University Collaborative Innovation Project (grant number: GXXT-2021-065). We thank the subjects who contributed to this study.

Author contributions

Y.S. wrote the initial manuscript and performed the analyses; H.C. provided critical input on the methods and analyses; F.M. and S.Y. were involved in data collection; J.Z. conceived the project and contributed to the editing of the manuscript; J.Z. and Y.Y. supervised the project.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Yuta Katsumi and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Karli Montague-Cardoso.

Data availability

The discovery data that support the findings are publicly available in the study’s Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/aq9wk/). The Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics (CNP) dataset is available at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds000030/versions/1.0.0. The Southwest University Adult Lifespan Dataset (SALD) dataset is available at 10.15387/fcp_indi.sald.

Code availability

Main analysis codes are publicly available in the study’s Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/aq9wk/). Diffusion embedding code is publicly accessible in the BrainSpace toolbox (https://github.com/MICA-MNI/BrainSpace).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yuhao Shen, Huanhuan Cai.

Contributor Information

Yongqiang Yu, Email: cjr.yuyongqiang@vip.163.com.

Jiajia Zhu, Email: zhujiajiagraduate@163.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-023-05029-0.

References

- 1.van Heukelum S, et al. Where is cingulate cortex? A cross-species view. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolls ET. The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for emotion, action, and memory. Brain Struct. Funct. 2019;224:3001–3018. doi: 10.1007/s00429-019-01945-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu C, et al. Functional segregation of the human cingulate cortex is confirmed by functional connectivity based neuroanatomical parcellation. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2571–2581. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oane I, et al. Cingulate cortex function and multi-modal connectivity mapped using intracranial stimulation. Neuroimage. 2020;220:117059. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichenstein SD, Verstynen T, Forbes EE. Adolescent brain development and depression: a case for the importance of connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;70:271–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aben B, Buc Calderon C, Van den Bussche E, Verguts T. Cognitive effort modulates connectivity between dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and task-relevant cortical areas. J. Neurosci. 2020;40:3838–3848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2948-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du J, et al. Functional connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Cortex. 2020;123:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palomero-Gallagher N, et al. Human pregenual anterior cingulate cortex: structural, functional, and connectional heterogeneity. Cereb. Cortex. 2019;29:2552–2574. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasquoine PG. Localization of function in anterior cingulate cortex: from psychosurgery to functional neuroimaging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013;37:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leech R, Sharp DJ. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain. 2014;137:12–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalsa S, et al. The structural and functional connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex: comparison between deterministic and probabilistic tractography for the investigation of structure-function relationships. Neuroimage. 2014;102:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolomeo S, et al. A causal role for the anterior mid-cingulate cortex in negative affect and cognitive control. Brain. 2016;139:1844–1854. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caruana F, et al. Motor and emotional behaviours elicited by electrical stimulation of the human cingulate cortex. Brain. 2018;141:3035–3051. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima Portugal LC, et al. Interactions between emotion and action in the brain. Neuroimage. 2020;214:116728. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brockett AT, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex is necessary for adaptation of action plans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:6196–6204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919303117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen VT, Breakspear M, Cunnington R. Reciprocal interactions of the SMA and cingulate cortex sustain premovement activity for voluntary actions. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:16397–16407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2571-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di X, Zhang H, Biswal BB. Anterior cingulate cortex differently modulates frontoparietal functional connectivity between resting-state and working memory tasks. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020;41:1797–1805. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edde M, et al. Age-related change in episodic memory: role of functional and structural connectivity between the ventral posterior cingulate and the parietal cortex. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020;225:2203–2218. doi: 10.1007/s00429-020-02121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crone JS, et al. Impaired consciousness is linked to changes in effective connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex within the default mode network. Neuroimage. 2015;110:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leech R, Kamourieh S, Beckmann CF, Sharp DJ. Fractionating the default mode network: distinct contributions of the ventral and dorsal posterior cingulate cortex to cognitive control. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:3217–3224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5626-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fransson P, Marrelec G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin P, et al. Static and dynamic posterior cingulate cortex nodal topology of default mode network predicts attention task performance. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016;10:212–225. doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder W, Uddin LQ, Nomi JS. Dynamic functional connectivity profile of the salience network across the life span. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021;42:4740–4749. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vereb D, et al. Temporal instability of salience network activity in migraine with aura. Pain. 2020;161:856–864. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm VE, et al. Enhanced visceromotor emotional reactivity in dyslexia and its relation to salience network connectivity. Cortex. 2021;134:278–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raimo S, et al. Neural correlates of apathy in patients with neurodegenerative disorders: an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13:1815–1834. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antal B, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus accelerates brain aging and cognitive decline: complementary findings from UK Biobank and meta-analyses. eLife. 2022;11:e73138. doi: 10.7554/eLife.73138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santangelo G, et al. Neural bases of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and an ALE meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019;107:672–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diener C, et al. A meta-analysis of neurofunctional imaging studies of emotion and cognition in major depression. Neuroimage. 2012;61:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, et al. Meta-analysis of cortical thickness abnormalities in medication-free patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:703–712. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0563-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray JP, Muller VI, Eickhoff SB, Fox PT. Multimodal abnormalities of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2020;177:422–434. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19050560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolls ET, et al. Functional connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex in depression and in health. Cereb. Cortex. 2019;29:3617–3630. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojtalik JA, Smith MJ, Keshavan MS, Eack SM. A systematic and meta-analytic review of neural correlates of functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2017;43:1329–1347. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baiano M, et al. Anterior cingulate volumes in schizophrenia: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Schizophr. Res. 2007;93:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise T, et al. Common and distinct patterns of grey-matter volume alteration in major depression and bipolar disorder: evidence from voxel-based meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong J, et al. Common and distinct patterns of intrinsic brain activity alterations in major depression and bipolar disorder: voxel-based meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:353. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01036-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrison PJ, Colbourne L, Harrison CH. The neuropathology of bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2020;25:1787–1808. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau WKW, Leung MK, Zhang R. Hypofunctional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in autism: evidence from coordinate-based imaging meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2020;103:109986. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dai Z, et al. Gray matter correlates of migraine and gender effect: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Neuroscience. 2015;299:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su T, et al. Structural and functional brain alterations in anorexia nervosa: a multimodal meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021;42:5154–5169. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marquand AF, Haak KV, Beckmann CF. Functional corticostriatal connection topographies predict goal directed behaviour in humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017;1:0146. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vos de Wael R, et al. Anatomical and microstructural determinants of hippocampal subfield functional connectome embedding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:10154–10159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803667115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bajada CJ, et al. A graded tractographic parcellation of the temporal lobe. Neuroimage. 2017;155:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huntenburg JM, et al. A systematic relationship between functional connectivity and intracortical myelin in the human cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2017;27:981–997. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagstyl K, Ronan L, Goodyer IM, Fletcher PC. Cortical thickness gradients in structural hierarchies. Neuroimage. 2015;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huntenburg JM, Bazin PL, Margulies DS. Large-scale gradients in human cortical organization. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018;22:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paquola C, et al. Microstructural and functional gradients are increasingly dissociated in transmodal cortices. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shine JM, et al. Human cognition involves the dynamic integration of neural activity and neuromodulatory systems. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:289–296. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vogel JW, et al. A molecular gradient along the longitudinal axis of the human hippocampus informs large-scale behavioral systems. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:960. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomez J, Zhen Z, Weiner KS. Human visual cortex is organized along two genetically opposed hierarchical gradients with unique developmental and evolutionary origins. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Margulies DS, et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12574–12579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608282113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guell X, Schmahmann JD, Gabrieli J, Ghosh SS. Functional gradients of the cerebellum. eLife. 2018;7:e36652. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kharabian Masouleh S, et al. Characterizing the gradients of structural covariance in the human hippocampus. Neuroimage. 2020;218:116972. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang S, et al. The thalamic functional gradient and its relationship to structural basis and cognitive relevance. Neuroimage. 2020;218:116960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hong SJ, et al. Toward a connectivity gradient-based framework for reproducible biomarker discovery. Neuroimage. 2020;223:117322. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bajada CJ, et al. A tutorial and tool for exploring feature similarity gradients with MRI data. Neuroimage. 2020;221:117140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vos de Wael R, et al. BrainSpace: a toolbox for the analysis of macroscale gradients in neuroimaging and connectomics datasets. Commun. Biol. 2020;3:103. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0794-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ngo GN, Haak KV, Beckmann CF, Menon RS. Mesoscale hierarchical organization of primary somatosensory cortex captured by resting-state-fMRI in humans. Neuroimage. 2021;235:118031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song Y, et al. Functional hierarchy of the angular gyrus and its underlying genetic architecture. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023;44:2815–2828. doi: 10.1002/hbm.26247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tian Y, Zalesky A. Characterizing the functional connectivity diversity of the insula cortex: subregions, diversity curves and behavior. Neuroimage. 2018;183:716–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang R, et al. Functional connectivity gradients of the insula to different cerebral systems. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023;44:790–800. doi: 10.1002/hbm.26099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasser MF, et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature. 2016;536:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature18933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eickhoff SB, Constable RT, Yeo BTT. Topographic organization of the cerebral cortex and brain cartography. Neuroimage. 2018;170:332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rolls ET, et al. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage. 2020;206:116189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beckmann M, Johansen-Berg H, Rushworth MFS. Connectivity-based parcellation of human cingulate cortex and its relation to functional specialization. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1175–1190. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3328-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heilbronner SR, Hayden BY. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a bottom-up view. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2016;39:149–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paus T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:417–424. doi: 10.1038/35077500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katsumi Y, Theriault JE, Quigley KS, Barrett LF. Allostasis as a core feature of hierarchical gradients in the human brain. Netw. Neurosci. 2022;6:1010–1031. doi: 10.1162/netn_a_00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Drevets WC, Savitz J, Trimble M. The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:663–681. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900013754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Touroutoglou A, Andreano J, Dickerson BC, Barrett LF. The tenacious brain: how the anterior mid-cingulate contributes to achieving goals. Cortex. 2020;123:12–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park HJ, Friston K. Structural and functional brain networks: from connections to cognition. Science. 2013;342:1238411. doi: 10.1126/science.1238411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Honey CJ, et al. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811168106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gu Z, Jamison KW, Sabuncu MR, Kuceyeski A. Heritability and interindividual variability of regional structure-function coupling. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4894. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suarez LE, Markello RD, Betzel RF, Misic B. Linking structure and function in macroscale brain networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020;24:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Kwaasteniet B, et al. Relation between structural and functional connectivity in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang X, et al. Sex-related human brain asymmetry in hemispheric functional gradients. Neuroimage. 2021;229:117761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gonzalez Alam T, et al. A tale of two gradients: differences between the left and right hemispheres predict semantic cognition. Brain Struct. Funct. 2022;227:631–654. doi: 10.1007/s00429-021-02374-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wan B, et al. Heritability and cross-species comparisons of human cortical functional organization asymmetry. eLife. 2022;11:e77215. doi: 10.7554/eLife.77215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu H, et al. Changed hub and corresponding functional connectivity of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder. Front. Neuroanat. 2016;10:120. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kang DW, et al. Distinctive association of the functional connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex on memory performances in early and late amnestic mild cognitive impairment patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:696735. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.696735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ge J, et al. Increasing diversity in connectomics with the Chinese Human Connectome Project. Nat. Neurosci. 2023;26:163–172. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Han S, Ma Y. Cultural differences in human brain activity: a quantitative meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2014;99:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tang Y, et al. Brain structure differences between Chinese and Caucasian cohorts: a comprehensive morphometry study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39:2147–2155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Poldrack RA, et al. A phenome-wide examination of neural and cognitive function. Sci. Data. 2016;3:160110. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wei D, et al. Structural and functional brain scans from the cross-sectional Southwest University adult lifespan dataset. Sci. Data. 2018;5:180134. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: data processing & analysis for (resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s12021-016-9299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38:95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fan L, et al. The human Brainnetome Atlas: a new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cereb. Cortex. 2016;26:3508–3526. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dong D, et al. Compression of cerebellar functional gradients in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2020;46:1282–1295. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hong S-J, et al. Atypical functional connectome hierarchy in autism. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1022. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08944-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coifman RR, et al. Geometric diffusions as a tool for harmonic analysis and structure definition of data: multiscale methods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500896102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lafon S, Lee AB. Diffusion maps and coarse-graining: a unified framework for dimensionality reduction, graph partitioning, and data set parameterization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2006;28:1393–1403. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2006.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yeo BT, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yarkoni T, et al. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:665–670. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Murphy K, Fox MD. Towards a consensus regarding global signal regression for resting state functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage. 2017;154:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Behzadi Y, Restom K, Liau J, Liu TT. A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage. 2007;37:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The discovery data that support the findings are publicly available in the study’s Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/aq9wk/). The Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics (CNP) dataset is available at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds000030/versions/1.0.0. The Southwest University Adult Lifespan Dataset (SALD) dataset is available at 10.15387/fcp_indi.sald.

Main analysis codes are publicly available in the study’s Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/aq9wk/). Diffusion embedding code is publicly accessible in the BrainSpace toolbox (https://github.com/MICA-MNI/BrainSpace).