Abstract

Extracellular vesicle (EV)-based low-density lipoprotein receptor (Ldlr) mRNA delivery showed excellent therapeutic effects in treating familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Nevertheless, the loading inefficiency of EV-based mRNA delivery presents a significant challenge. Recently, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have been fused to EV membrane proteins for selectively encapsulating targeted RNAs to promote loading efficiency. However, the strong interaction between therapeutic RNAs and RBPs prevents RNA release from endosomes to the cytosol in the recipient cells. In this study, an improved strategy was developed for efficient encapsulation of Ldlr mRNA into EVs in donor cells and controllable release in recipient cells.

Methods: The MS2 bacteriophage coat protein (CD9-MCP) fusion protein, Ldlr mRNA, and a customized MS2 containing RNA aptamer base-pair matched with Ldlr mRNA were expressed in donor cells. Cells receiving the above therapeutic EVs were simultaneously treated with EVs containing “Ldlr releaser” with a sequence similar to the recognition sites in Ldlr mRNA. Therapeutic effects were analyzed in Ldlr-/- mice receiving EV treatments via the tail vein.

Results: In vitro experiments demonstrated improved loading efficiency of Ldlr mRNA in EVs via MS2-MCP interaction. Treatment of “Ldlr releaser” competitively interacted with MS2 aptamer with higher affinity and released Ldlr mRNA from CD9-MCP for efficient translation. When the combinatory EVs were delivered into recipient hepatocytes, the robust LDLR expression afforded therapeutic benefits in Ldlr-/- mice.

Conclusion: We proposed an EV-based mRNA delivery strategy for enhanced encapsulation of therapeutic mRNAs in EVs and RNA release into the cytosol for translation in recipient cells with great potential for gene therapy.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicles, therapeutic mRNA, RNA aptamer, loading efficiency, endosome escape, low-density lipoprotein receptor

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), characterized by a severe increase in plasma low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and premature coronary heart disease, is mainly caused by Low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) dysfunction1-3. LDLR is a crucial lipoprotein receptor on the hepatocyte surface, essential for LDL-C clearance 4, 5. Increasing evidence confirmed that restoring LDLR expression in the liver could efficiently decrease total cholesterol 6-8. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are lipid-bound vesicles secreted by cells into the extracellular space and have recently emerged as a promising vehicle for nucleic acid-based therapeutics in gene therapy 9. EVs possess multiple advantages for the delivery of therapeutics, such as easy manipulation, high biological penetration, and low immunogenicity 10-13. Our recent study verified the excellent therapeutic effects of EV-based Ldlr mRNA delivery for FH treatment. Ldlr mRNA was stably encapsulated in EVs and delivered into recipient cells, restoring Ldlr expression in the Ldlr-/- mouse model 14. However, the loading inefficiency, especially for large-size mRNAs, limits the application of EV-based mRNA delivery 15-18.

Several studies have shown that EVs have great potential for macromolecule loading. Arrestin domain-containing protein1-mediated microvesicles, similar to EVs, could selectively recruit targeted proteins, therapeutic RNAs, and the genome-editing CRISPR-Cas9/guide RNA complex 19. Moreover, a cellular nanoporation (CNP) biochip technique was applied to achieve large-scale production and targeted nucleotide sequence encapsulation in exosomes 20. Besides, recent studies revealed that RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are crucial in sorting RNAs into EVs during biosynthesis 21-23. Therefore, EV membrane proteins, such as CD9 or CD63, were engineered to fuse with RBPs for selective enrichment of target RNAs. A loading approach was proposed, in which MS2 bacteriophage coat protein (MCP) was fused to the EV membrane protein Lamp2b. An increased loading efficiency of targeted RNAs was observed when the cognate MS2 stem-loop was engineered into cargo RNAs 24. In our previous studies, CD9-HuR was used to sort AU-rich element-containing RNAs and Lamp2b-MCP for sorting the MS2 stem-loop-containing RNAs into exosomes 25, 26. However, the mRNAs delivered by this strategy tend to confine within the endosomes due to the high affinity between target mRNAs and the membrane-anchored fused RBPs 26. To solve this problem, we recently engineered EVs by fusing zinc finger (ZF) motifs with CD9 and designed a DNA aptamer to recognize and facilitate targeted mRNA encapsulation into CD9-ZF-engineered EVs. The DNA aptamer binding to targeted mRNA could be degraded by electroporating DNase before delivery to recipient cells, resulting in controlled, targeted mRNA release 27.

We developed the controllable release of therapeutic mRNA to simplify the EV delivery strategy by avoiding electroporation and exogenous DNase application. In this study, we proposed an improved EV-based strategy for enhanced Ldlr mRNA loading efficiency in EVs and for facilitated mRNA cargo release into the cytosol of recipient cells. The donor cells were forced to express the CD9-MCP fusion protein and Ldlr mRNA simultaneously. With a customized MS2 stem-loop-containing RNA aptamers base-pair matched with Ldlr mRNA, target mRNA encapsulation into EVs was enriched via MS2-MCP interaction. In the recipient cells receiving these therapeutic EVs, additional treatment of another type of EVs containing “Ldlr releaser”, with a sequence similar to the recognition sites in target mRNA, could release the therapeutic mRNA from CD9-MCP for efficient translation. The proposed strategy was demonstrated to be efficient in loading and delivering functional low-density lipoprotein receptor (Ldlr) mRNA with therapeutic potential in the Ldlr knockout mouse model.

Results

Specific enrichment of Ldlr mRNA in CD9-MCP-engineered EVs

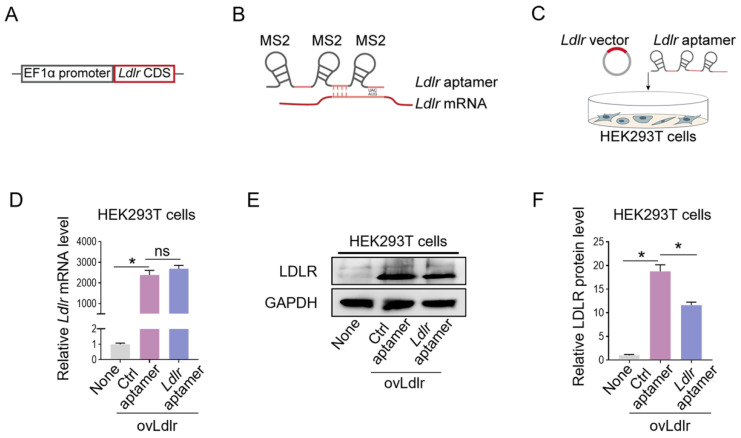

We first generated an Ldlr-expressing vector by cloning the Ldlr coding sequence (CDS) downstream of the EF1α promoter (Figure 1A). Theoretically, the transcribed Ldlr mRNA could interact with a customized aptamer (denoted as Ldlr aptamer), which included a sequence base-pair matching with Ldlr mRNA near the translation initiation codon and 3 MS2 stem-loop sites. The 19-base RNA stem-loop structured MS2 stem-loop site could be recognized by MCP (Figure 1B, Figure S1A). As the recruitment of ribosomal subunits upstream of the initiation codon is crucial for protein synthesis initiation 28, Ldlr mRNA recognition by the Ldlr aptamer near the initiation codon might disturb ribosome assembly and prevent translation initiation. We verified this hypothesis by co-transfecting the Ldlr-expressing vector and the synthesized Ldlr aptamer into HEK293T cells (Figure 1C). Co-transfection with Ldlr aptamer did not change the Ldlr mRNA expression (Figure 1D), but significantly lowered LDLR protein expression (Figure 1E-F). In contrast, Co-transfection with the control aptamer (denoted as Ctrl aptamer), which did not base-pair with Ldlr mRNA, had no such effects. The data suggested that Ldlr aptamer could inhibit Ldlr mRNA translation.

Figure 1.

Construction of the Ldlr expression vector and aptamer: (A) Schematic illustration of Ldlr-expressing vector construction. The CDS of Ldlr was cloned downstream of the EF1α promoter. (B) Schematic illustration of the interaction between Ldlr mRNA and Ldlr aptamer. The Ldlr aptamer contains 3 MS2 stem-loop sites and a sequence region base-pair matched with Ldlr mRNA near the translation initiation site. (C) Schematic illustration of co-transfection of Ldlr-expressing vector (ovLdlr) and Ldlr aptamer into HEK293T cells (D) Expression of Ldlr mRNA in HEK293T cells treated as indicated. Gapdh served as the internal control. (E) Western blot analysis of LDLR protein in HEK293T cells with indicated treatments. GAPDH expression served as the loading control. The data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Quantification of Western blot band intensity by densitometry. Data are presented as mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P<0,05 by one-way ANOVA. ns, no significance.

In subsequent experiments, we explored whether the Ldlr aptamer could promote Ldlr mRNA encapsulation into EVs engineered with CD9-MCP, in which MCP was fused to the C-terminus of CD9 (Figure 2A). HEK293T cells without any treatment (None), transfected with empty vector, or CD9-MCP recombinant plasmid were used, and the EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation were denoted as EVNone, EVEmpty vector, and EVCD9-MCP respectively. The CD9-MCP fusion protein was highly expressed in HEK293T cells transfected with the CD9-MCP recombinant plasmid compared with the None or Empty vector groups (Figure 2B-C). Also, compared with EVNone or EVEmpty vector, EVs derived from HEK293T cells transfected with EVCD9-MCP had abundant CD9-MCP fusion protein (Figure 2C). No noticeable change in EVCD9-MCP size distribution and morphology was observed, as characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis and transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2D-E). The average diameters of isolated vesicles were 132.0±2.3 (EVNone), 133.6±3.7 (EVEmpty vector), 134.1±2.6 (EVCD9-MCP), and no significant differences were detected among the 3 groups. Western blot analysis of the exosomal inclusive markers CD63, TSG101, and the exclusive marker GM130 further verified that most engineered EVs were exosomes (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

EVs engineered with CD9-MCP fusion protein: (A) Schematic illustration of engineering strategy and membrane localization of the CD9-MCP fusion protein. MCP was designed to fuse to the C-terminus of CD9. (B) Schematic illustrating the preparation and isolation of CD9-MCP-engineered EVs. (C) Representative Western blot analysis of CD9-MCP fusion protein expression in HEK293T cells and derived EVs with indicated treatments. Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded, and GAPDH served as the loading control. (D) Representative TEM images of indicated EVs. (E) Size distribution of indicated EVs. (F) Western blot analysis of the inclusive EVs markers TSG101, CD63, and the exclusive marker GM130.

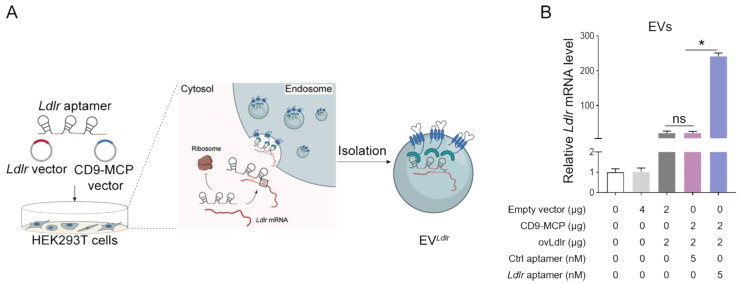

Ldlr-expressing vector, CD9-MCP recombinant vector, and Ldlr aptamer were simultaneously transfected into HEK293T cells, MS2 stem-loop sites in Ldlr aptamer were expected to facilitate Ldlr mRNA sorting into CD9-MCP-engineered EVs via MS2-MCP interaction (Figure 3A). The efficiency of Ldlr aptamer for sorting Ldlr mRNA into EVs was confirmed by qPCR analysis of Ldlr mRNA abundance in EVs. Compared with the controls, transcribed Ldlr mRNA was selectively encapsulated into the CD9-MCP-engineered EVs, while the Ldlr aptamer further promoted Ldlr mRNA encapsulation (Figure 3B). Moreover, with the enrichment of the Ldlr mRNA in EVLdlr, there was no space for other mRNAs in the EVs. In other words, EVs had much fewer nonspecific mRNAs, which could be seen from the higher Ct value of Gapdh per EV (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Ldlr aptamer promotes Ldlr mRNA sorting into CD9-MCP-engineered EVs: (A) Schematic illustration of Ldlr mRNA enriched in CD9-MCP-engineered EVs. Ldlr-expressing vector, Ldlr aptamer, and CD9-MCP vector were simultaneously transfected into HEK293T cells. Ldlr mRNA was expressed by the Ldlr-expressing vector and recognized by the Ldlr aptamer, preventing translation. The Ldlr aptamer promoted Ldlr mRNA enrichment in CD9-MCP-engineered EVs through MS2/MCP binding. (B) qPCR analysis of Ldlr mRNA in EVs derived from cells treated as indicated. Data are presented as mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 one-way ANOVA.

The advantage of the proposed strategy for loading efficiency was further confirmed by including an Ldlr-MS2-expressing vector as another control in which the transcribed Ldlr mRNA was flanked with 3 MS2 stem-loop sites in the 3' UTR region (Figure S3A) and could be encapsulated into CD9-MCP-engineered EVs via MS2-MCP interaction (Figure S3B). When the Ldlr mRNA levels were comparable between Ldlr-MS2-transfected and Ldlr+Ldlr aptamer-transfected HEK293 cells (Figure S3C), LDLR protein expression in the Ldlr-MS2 group was much higher than in the Ldlr+Ldlr aptamer group (Figure S3D-E), further confirming that Ldlr aptamer could repress Ldlr mRNA translation. Thus, due to the mRNA translation inhibition, Ldlr mRNA abundance was higher in the EVs in the Ldlr+Ldlr aptamer group than in the Ldlr-MS2 group (Figure S3F). It is plausible that due to its small size, translationally repressed Ldlr mRNA was easily recruited into CD9-MCP-engineered EVs.

EV-mediated functional Ldlr mRNA delivery in vitro

Ldlr mRNA release to the cytosol is a prerequisite for its translation. To this end, an Ldlr releaser with a similar sequence as the Ldlr AUG region and based-paired with the Ldlr aptamer was synthesized. The higher affinity of the aptamer to Ldlr releaser than to Ldlr mRNA was achieved by base-paring (Figure S1), allowing the Ldlr releaser to replace Ldlr mRNA with high efficiency. Ldlr releaser or Ctrl releaser was transfected into HEK293T cells, and the EVs (denoted as EVLdlr releaser or EVCtrl releaser) were collected (Figure S4A). Nanoparticle tracking analysis and transmission electron microscopy showed that Ldlr releaser or Ctrl releaser encapsulation did not change the size and morphology of engineered EVs compared with non-loading EVs (Figure S4B-C). Western blot analysis revealed a similar expression pattern of the exosomal inclusive markers CD9 and TSG101 and exclusive marker GM130, validating the exosomal characteristics of the EVs (Figure S4D). qPCR analysis confirmed that Ldlr releaser or Ctrl releaser was successfully transfected into the recipient cells and loaded into EVs compared with U6 snRNA (Figure S4E-F). Theoretically, a 10-fold excess of Ldlr releaser is needed to release Ldlr mRNA competitively. Notably, the copy number of Ldlr releaser per EV was more than 60-fold higher than Ldlr mRNA per EV, indicating EV Ldlr releaser/EVLdlr at the ratio of 1:10 translated into the Ldlr releaser/Ldlr mRNA copy number ratio of 6:1.

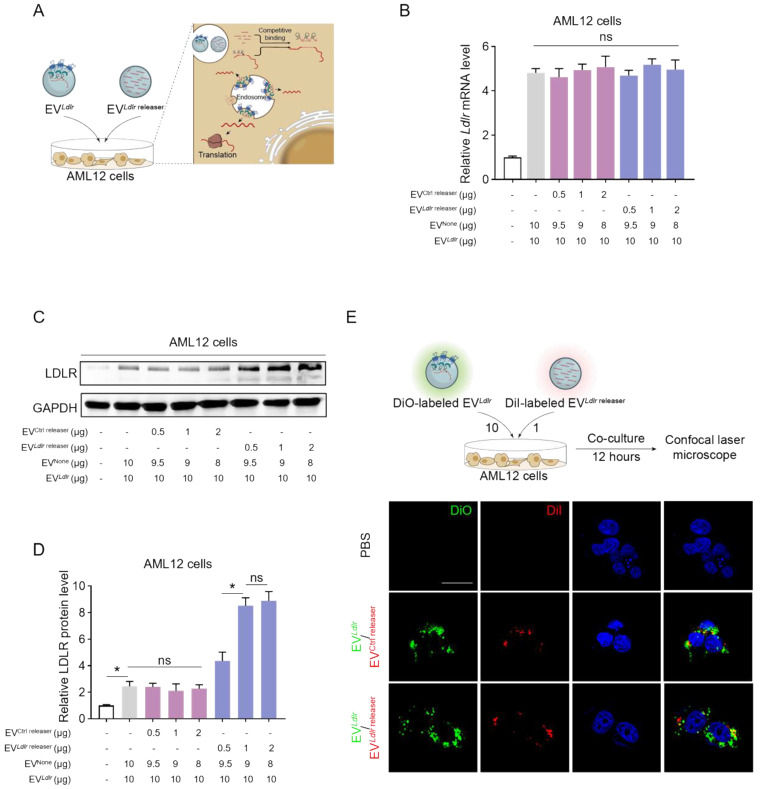

We incubated AML12 cells with EVCtrl releaser and EVLdlr at the ratio of 1:20, 1:10, and 1:5. EVNone, the EV derived from HEK293T cells without any treatment, was included to ensure equal amounts of EVs in each group. The Ldlr mRNA level increased in AML12 cells after receiving EVLdlr releaser/EVLdlr treatment (Figure 4B). Western blot analysis showed significantly increased LDLR protein expression in the EVLdlr releaser/EVLdlr treatment group compared with EVCtrl releaser/EVLdlr treatment. Moreover, EVLdlr releaser/EVLdlr at the 1:10 ratio increased LDLR expression to nearly 6-fold, while higher EVLdlr releaser had no additional effects (Figure 4C, D). Especially, the fold-change could not be achieved by increasing the EV amount, as the cell endocytosis ability was limited (Figure S5A-B). EV tracking analysis confirmed that DiO-labeled EVLdlr and DiI-labeled EVLdlr releaser (or EVCtrl releaser) could be endocytosed by AML12 cells efficiently, ensuring the competitive binding (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser efficiently delivers Ldlr mRNA for translation in vitro: (A) Schematic illustration of the EV-mediated Ldlr mRNA and Ldlr releaser delivery and mRNA release for efficient translation (B) qPCR analysis of Ldlr mRNA in AML12 cells. EVLdlr releaser or EVCtrl release, together with EVLdlr at the indicated amounts, were incubated with AML12 cells. EVNone was applied to ensure an equal amount of EVs in each group. Data are presented as mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. ns, no significance. (C) Western blot analysis of LDLR protein expression in AML12 cells treated as indicated. The data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Quantification of Western blot bands by densitometry. The data are presented as mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA. ns, no significance. (E) Representative fluorescence microscopy images showing endocytosis of EVs by AML12 cells. DiO-labeled EVLdlr and DiI-labeled EVLdlr releaser (or EVCtrl releaser) were incubated with the cells and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were counterstained by Hoechst. Treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) served as the negative control. Scale bar=20 μm.

We verified whether EV Ldlr releaser/EVLdlr treatment at the ratio of 1:10 completely released the mRNA by transfecting AML12 cells with different doses of Ldlr releaser, followed by incubation with 10 µg EVLdlr (Figure S6A). The LDLR protein expression was enhanced by increasing the dose of the Ldlr releaser, However, transfection at 0.5 nM or 2.5 nM Ldlr releaser or 1 µg EVreleaser had similar releasing effects, suggesting that transfection at 0.5 nM or 1 µg EV Ldlr releaser was enough to release all the Ldlr mRNA delivered by 10 µg EVLdlr (Figure S6B). Notably, liposome-based delivery needed more Ldlr releaser to completely release Ldlr mRNA than EVLdlr releaser, which might be attributed to high endocytosis efficiency and easy endosome escape for EV-based delivery. It is also important to note that EVLdlr releaser/EVLdlr-mediated Ldlr mRNA delivery and subsequent translation were much higher than the same amount of EV-based Ldlr-MS2 delivery (Figure S6C). Collectively, these results showed that EVLdlr, together with EVLdlr releaser at the ratio of 10:1, should be an efficient platform for delivering functional Ldlr mRNA into recipient cells.

Efficient in vivo delivery of Ldlr mRNA to the liver by EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser

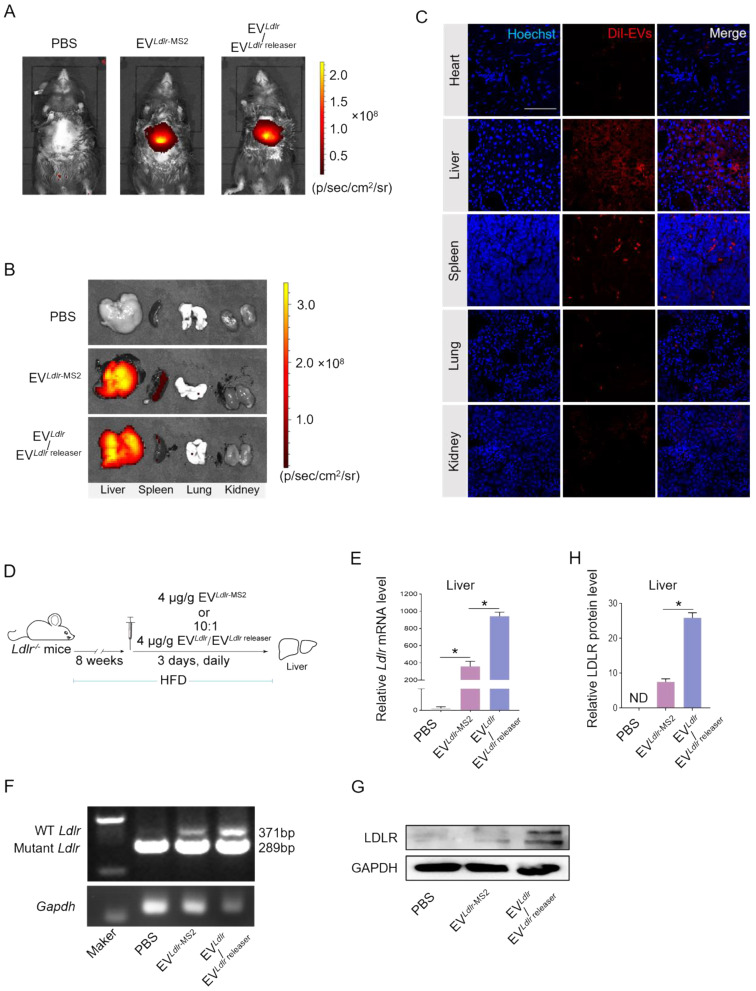

In vivo distribution in target organs is a prerequisite for the therapeutic effects of any proposed strategy. After tail vein injection, we profiled the in vivo distribution of EVLdlr-MS2 or EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser. DiR-labeled EVs were tracked and visualized by the in vivo imaging system (IVIS) and found that EVLdlr-MS2 or EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser had a similar distribution profile, mainly in the liver and spleen (Figure 5A-B). In addition, DiI-labeled EVs were tracked and visualized by fluorescence microscopy in tissue sections, confirming the same in vivo distribution profile between EVLdlr-MS2 and EVLdlr /EVLdlr releaser treatment (Figure 5C). The strong liver tropism might be ascribed to two aspects. On the one hand, Kuppfer cells in the liver are one of the key recipient cell types of the EVs due to their high phagocytosis capacity, and on the other hand, hepatocytes are also the recipient cells due to the sinusoidal structure in the liver and their high uptake ability 29-31. The strong tropism in the spleen can be attributed to the presence of abundant macrophages. Collectively, the data suggested that EV could efficiently deliver mRNA into hepatocytes.

Figure 5.

EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser effectively delivers translationally accessible Ldlr mRNA in vivo: (A) Representative IVIS images showing the distribution of EVs. Mice were injected with PBS, 100 μg DiR-labeled EVLdlr-MS2 or EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser (10:1) in 100 μl via the tail vein, and IVIS imaging was performed 4 h after injection. (B) The distribution of DiR-labeled EVs in different organs as visualized by IVIS (C) Representative fluorescence microscopic images of the localization of DiI-labeled EVs in indicated organs. Scale bar = 100 μm (D) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure. Ldlr-/- mice 6-8 weeks of age were fed with HFD for 8 weeks, followed by the tail vein injection of EVs daily for 3 days. (E) qPCR analysis of exogenous Ldlr mRNA in livers of mice treated as indicated. (F) Representative semi-quantitative PCR analysis of Ldlr mRNA expression in livers from mice after indicated treatments. The 371 bp band represents the wild-type Ldlr from EVs, while the 289 bp band represents endogenous mutated Ldlr in Ldlr-/- mice. (G) Western blot analysis of LDLR expression in livers from mice treated as indicated. Representative data from 3 independent experiments. (H) Quantification of Western blot bands by densitometry. Data are presented as mean±SEM. *P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

The therapeutic effects of EVLdlr-MS2 or EVLdlr /EVLdlr releaser following 8 weeks of a high-fat diet were explored in Ldlr-/- mice receiving PBS, EVLdlr-MS2, or EVLdlr /EVLdlr releaser (at the ratio of 10:1) (Figure 5D). Consistent with the higher abundance of Ldlr mRNA in EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser than in EVLdlr-MS2, EVLdlr /EVLdlr releaser treatment increased the wild-type Ldlr mRNA in the liver to a greater extent than EVLdlr-MS2 treatment, as detected by nested PCR and semi-quantitative PCR (Figure 5E-F, and Figure S7A-B). Accordingly, LDLR protein expression in the liver was also significantly higher, with a nearly 3-fold increase after EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment than EVLdlr-MS2 treatment (Figure 5G-H). These results revealed that the proposed EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser strategy could deliver Ldlr mRNA into the liver in vivo and release Ldlr mRNA into the cytosol for efficient translation.

Amelioration of liver steatosis and atherosclerosis by EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment

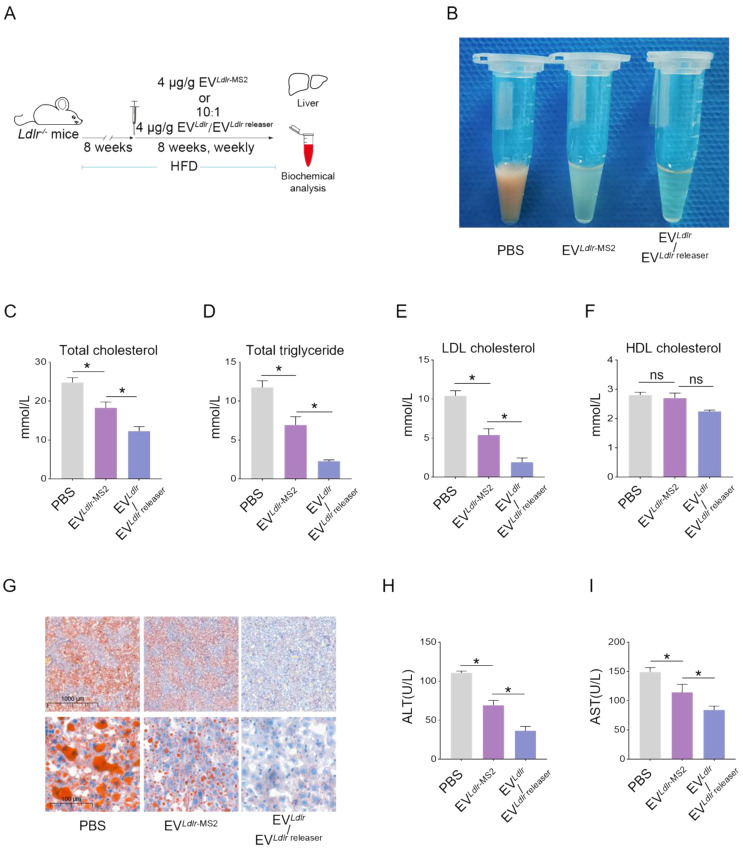

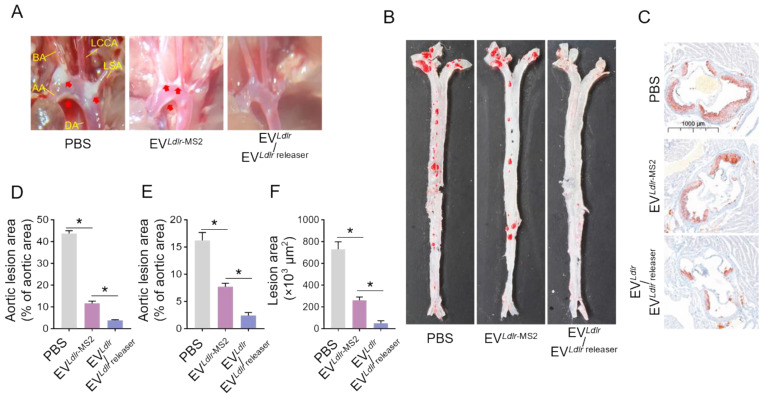

Subsequently, we evaluated the therapeutic effects of the EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser in Ldlr-/- mice on a high-fat diet treated with indicated EVs weekly for 8 weeks (Figure 6A). Treatments with PBS or EVLdlr-MS2 were included as controls. The serum was extremely milky in the PBS group, semi-transparent in the EVLdlr-MS2 group, and nearly transparent in EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser group (Figure 6B). Besides, both EVLdlr-MS2 and EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatments decreased the total cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL-C levels, while the fold-change induced by EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser was much larger (Figure 6C-E). However, no significant difference in the HDL-C level was observed among the 3 groups (Figure 6F). Oil Red O staining of liver sections consistently showed reduced lipid accumulation in hepatocytes following EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment (Figure 6G). Accordingly, plasma AST and ALT decreased after EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment (Figure 6H-I). EVLdlr-MS2 treatment also reduced lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and decreased plasma AST and ALT, though the effects were not as prominent as with the EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment (Figure 6G-I). Consistent with the rescued lipid metabolism, EV treatment, especially EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment, decreased the number and size of atherosclerosis plaques, as detected by the gross view of the blood vessels, Oil O Red staining, and the quantification data (Figure 7A-F). Especially, all groups had no significant differences in body weights after treatment (Figure S8). In summary, the proposed EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser delivery strategy efficiently restored the gene expression at the protein level in the liver and ameliorated the disease phenotype, including steatosis, high LDL-C, and atherosclerosis.

Figure 6.

EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment ameliorates abnormal lipid metabolism in Ldlr-/- mice: (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure. Ldlr-/- mice aged 6-8 weeks were first fed with HFD for 8 weeks, followed by the tail vein injection of PBS or indicated EVs weekly for 8 weeks as indicated. At the end of the experiments, mice were sacrificed for systemic analysis. (B) Representative images of serum appearance from mice treated as indicated. Analysis of (C) total cholesterol, (D) total triglyceride, (E) LDL-C, and (F) HDL-C in Ldlr-/- mice treated as indicated. (G) Representative images of Oil Red O staining of the liver in Ldlr-/- mice treated as indicated. Analysis of (H) plasma ALT and (I) AST. Data are presented as mean±SEM. n=6. *P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA. ns, no significant difference.

Figure 7.

EVLdlr/EVLdlr releaser treatment alleviates atherosclerotic lesions in Ldlr-/- mice: (A) Representative images of the atherosclerosis lesions at the aortic arch in mice with indicated treatments. Ldlr-/- mice aged 6-8 weeks were fed with HFD for 8 weeks, followed by the tail vein injection of PBS or indicated EV combinations weekly for 8 weeks as indicated. AA, ascending aorta; BA, brachiocephalic artery; LCCA, left common carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery; DA, descending aorta (B) Representative images of Oil Red O staining of the atherogenic lesion areas in mice treated as above (C) Representative images of the cross-sectional view of aortic roots stained with Oil Red O in mice treated as above (D) Percentage of the atherosclerotic area in the aortic arch in mice treated as above (E) Percentage of the atherosclerotic region in B. (F) Statistical analysis of the Oil O red positive plaque area in C. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=6. *P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

In the present study, we have developed an EV-based mRNA delivery strategy in which the therapeutic mRNA was selectively enriched in EVs by a customized RNA aptamer in donor cells and efficiently released by a releaser RNA sequence for translation in recipient cells. We efficiently delivered Ldlr mRNA using the proposed strategy to the liver cells, restoring LDLR expression and ameliorating the phenotype of high LDL cholesterol, atherosclerosis, and steatosis in the Ldlr-/- mouse model.

EV-mediated delivery of therapeutic mRNAs has shown great potential for clinical translation. However, the low loading efficiency, especially for target mRNAs of large size, precludes its wide application 32, 33. Recent studies revealed that RNA cargos with specific sequences could be recognized by corresponding RNA-binding proteins, allowing selective encapsulation of RNA into EVs with high efficiency. Exosomal proteins fused with specific RBPs have been developed to enrich RNAs of interest 24, 34, 35. In this study, a customized RNA aptamer could be recognized by the RNA-binding protein MCP via the MS2 stem-loop and interacted with Ldlr mRNA by complementary base pairing with the sequence around the translation initiation region. The RNA aptamer selectively recruited the mRNA to the EVs and also repressed Ldlr mRNA translation, possibly by disturbing translation initiation and ribosome movement, allowing much easier mRNA encapsulation into EVs. This “indirect” strategy has the advantage of designing the RNA aptamer for any mRNA of interest without manipulating the therapeutic mRNA itself. Although a tailored RNA aptamer with MS2 was created in this study, its optimization to increase Ldlr mRNA enrichment is worth further exploration, especially for the recognition region corresponding to the AUG region, the length of the sequence, and the specificity to the target mRNA.

mRNA cargos must be released to the cytosol to serve as translation templates. EV cargos are released when the EVs fuse with the plasma membrane or endosome membrane. Thus, target mRNAs delivered by the proposed EV strategy are restricted due to the MCP-aptamer-RNA interaction, making the target mRNA inaccessible for translation 36-38. We designed the Ldlr releaser for the efficient release of the Ldlr mRNA with two specific features: 1) Ldlr releaser was endowed with a superior binding ability to the aptamer as the matched nucleotides to Ldlr aptamer were longer than that of Ldlr mRNA, and 2) Ldlr releaser was encapsulated in EVs and simultaneously delivered to recipient cells with EVLdlr. As a small RNA, a large amount of releaser could be encapsulated per EV, and therefore, much less EVLdlr releaser was needed to release the mRNA. We found that EVLdlr releaser/EVLdlr at the ratio of 1:10 was sufficient to release the Ldlr mRNA, producing a more than 3-fold increase in protein expression. Notably, in the titration experiment, liposome-based delivery required more Ldlr releaser to release Ldlr mRNA than EVLdlr releaser completely. This could be explained by the possibility that EV might have high endocytosis efficiency and easier endosome escape.

The flexible strategy in designing the RNA aptamer and releaser might endow the aptamers with additional functions. For example, it has been shown that inhibition of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) by small interfering RNA (siRNA) could lower LDL cholesterol in FH 16, 39. Theoretically, endowing the aptamers or releasers with the PCSK9 knockdown feature would be beneficial for improving the lipid profile.

Conclusion

We have developed an improved strategy for efficient encapsulation of Ldlr mRNA into EVs in donor cells with a controllable release of the therapeutics in recipient cells. In the donor cells, CD9-MCP fusion protein, Ldlr mRNA, and a customized MS2 stem-loop-containing RNA aptamer sorted the Ldlr mRNA into EVs. In the recipient cells, EV-mediated delivery of Ldlr releaser competitively interacted with the aptamer and released the Ldlr mRNA for efficient translation. The proposed strategy demonstrated improved therapeutic effects in FH treatment and holds great potential for delivering other therapeutic mRNAs for a broad range of diseases.

Materials and Methods

Design and synthesis of plasmid construction and aptamers

Plasmids expressing CD9-MCP, Ldlr, and Ldlr-MS2 were synthesized by Genscript Biotech Corporation. Ldlr aptamer, Ctrl Ldlr aptamer, Ldlr releaser, and Ctrl releaser were also synthesized by Genscript Biotech Corporation. The detailed sequences are listed in Table S1-2.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells and mouse liver 12 (AML12) cells were cultured in complete media containing high glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Logan, Utah, USA) with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Logan, Utah, USA). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Fresh medium was replaced every two days. For in vitro treatment of EVs in cell culture, 10 μg EVs per well were cocultured with HEK293T cells in 6-well plates. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to transfect plasmids or designed aptamers as instructed by the manufacturer's protocol. Before transfection, cells were pretreated with serum-free DMEM for 6 h.

EV isolation and characterization

EVs were collected by ultracentrifugation as described previously with minor modifications 40. Cells were cultured in an FBS-free medium. The culture medium was centrifuged under 500 g for 10 min and then at 10000 g for 20 min to remove cells and debris. The supernatant was then ultracentrifuged at 100000 g for 120 min. The EV pellets were washed once with PBS and were resuspended in PBS or stored at -80 ℃ for subsequent experiments. The EVs were imaged by transmission electron microscopy (JEM-200EX TEM, Tokyo, Japan) and diluted for size distribution analysis by Nanosight. The exosomal marker expression in EVs was analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against CD9 (ab236630, Abcam), GM130 (sc71166, Santa Cruz), TSG101 (ab83, Abcam), and CD63 (ab217345, Abcam).

EV labeling and tracing

EVs were labeled by DiO, DiI, or DiR (Beyotime, China) via direct incubation for 30 min, and the free dye was removed by another round of EV isolation. Cells were incubated with DiI- or DiO-labeled EVs (20 μg/mL) in 35 mm confocal dishes for 12 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst for 5 min, and the images were obtained using a confocal microscope. For in vivo tracing of EVs, purified DiR-labeled EVs were injected via the tail vein, and the distribution of EVs was analyzed by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) 4 h later.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Small RNAs (including the aptamer and releaser) and mRNA were reversely transcribed using the miRcute Plus miRNA Synthesis Kit and Transcriptor First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche), respectively, following the manufacturers' instructions. qPCR was performed by FastStart Essential DNA Green Master. U6 was used as an internal control, and RNA aptamers and GAPDH (Gapdh) were used for the normalization of mRNA abundance. Relative expression was calculated by the 2-ddCt method unless otherwise indicated. The sequences of PCR primers are provided in Table S3.

Western blots

EVs were collected from the cell culture medium by ultracentrifugation. The protein concentration in each sample was measured by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225, Thermo Scientific™). About 40 μg EV protein samples or cell/tissue lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to the nitrocellulose filter membrane, blocked with 3% nonfat milk in TBST for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies: anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibody (D110016-0100, BBI Life Sciences), anti-GM130 (11308-1-AP), anti-CD9 (ab92726, Abcam), anti-TSG101 (ab83, Abcam), anti-MCP (ABE76, Merck Millipore), and anti-LDLR (ab52818, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing in TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, and the chemiluminescence reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was applied to visualize the blots. The densities of the immunoreactive bands were analyzed by Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Air Force Medical University. Ldlr-/- mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University and were raised on a high-fat diet for 8 weeks. To analyze the EV-based delivery efficiency, 4 μg/g EVs were injected via the tail vein once a day for 3 days. Mice were sacrificed at the end of the experiment, and livers were harvested for qPCR and Western blotting. For the therapeutic efficacy evaluation, Ldlr-/- mice were fed a high-fat diet for 8 weeks before the treatment. PBS or indicated EVs at the dosage of 4 μg/g were injected via the tail vein weekly for 8 weeks. The blood, liver, and aorta were obtained for analysis.

Histology

The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.). After perfusion with PBS, the main organs, including the heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney, were dissected. The aorta and heart were exposed, and surrounding tissues were excised. The aorta-to-iliac bifurcation was dissected for Oil-red-O staining. The aortic arch bifurcation view was photographed by a digital camera under the stereomicroscope. The harvested main organs/tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and then embedded in OCT compound. Embedded tissues were then cut into 5 μm slices for Oil-red-O or H&E staining. Image J was used to analyze the percentage of lesion area. The lesion size and lipid core area were compared.

Serum biochemistry

Blood samples of mice were obtained after fasting for 8 h. The whole blood samples were kept at room temperature for 2 h or overnight at 4 °C, then centrifuged at 4°C, 4000 g for 15 min. The supernatants were stored at -20°C. The concentration of plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, ALT, and AST were measured by Chemray 800 at Wuhan Service Biotechnology CO., LTD.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SEM. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to verify distribution normality. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's posthoc test was used for multiple comparisons among 3 or more groups. Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used for two-group comparisons for normally or abnormally distributed data. These analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Sequence of aptamers and releasers. Table S2: Sequences of primers. Table. S3: Sequences of plasmids. Figure S1: Design of Ldlr aptamer and Ldlr releaser. Figure S2: qPCR analysis of Ct value of GAPDH in EVs. Figure S3: Construction of EVLdlr-MS2 and EV loading efficiency of Ldlr mRNA. Figure S4. Construction and characterization of EVLdlr releaser. Figure S5: LDLR expression in AML12 cells co-cultured with increasing amounts of EVLdlr-MS2. Figure S6: Competitive binding of Ldlr releaser with Ldlr aptamer. Figure S7: Illustration of Ldlr gene deletion strategy and primer design. Figure S8: Body weights of mice with different treatments.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the technical help of Zhenzhen Hao from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Fourth Military Medical University.

Funding sources

This study was supported by the National Nature Science Fund of China (Grant No.31771507 and 81970737), and Clinical Fund of Tangdu Hospital (2021LCYJ006).

References

- 1.Ajufo E, Rader DJ. New Therapeutic Approaches for Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:113–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051215-030943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao H, Li Y, He L, Pu W, Yu W, Li Y. et al. In Vivo AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing Ameliorates Atherosclerosis in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2020;141:67–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath KE, Gahan M, Whittall RA, Humphries SE. Low-density lipoprotein receptor gene (LDLR) world-wide website in familial hypercholesterolaemia: update, new features and mutation analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:243–6. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00647-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng X, Sureda A, Jafari S, Memariani Z, Tewari D, Annunziata G. et al. Berberine in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: From Mechanisms to Therapeutics. Theranostics. 2019;9:1923–51. doi: 10.7150/thno.30787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mineo C. Lipoprotein receptor signalling in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1254–74. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman M, Rader DJ, Muller DW, Kolansky DM, Kozarsky K, Clark BJ 3rd. et al. A pilot study of ex vivo gene therapy for homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat Med. 1995;1:1148–54. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Fang B, Eisensmith RC, Li XH, Nasonkin I, Lin-Lee YC. et al. In vivo gene therapy for hyperlipidemia: phenotypic correction in Watanabe rabbits by hepatic delivery of the rabbit LDL receptor gene. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:768–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI117725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCaffrey AP, Fawcett P, Nakai H, McCaffrey RL, Ehrhardt A, Pham TT. et al. The host response to adenovirus, helper-dependent adenovirus, and adeno-associated virus in mouse liver. Mol Ther. 2008;16:931–41. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohner E, Yang R, Foo KS, Goedel A, Chien KR. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:1586–600. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, Dong Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2021. pp. 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Weng Y, Li C, Yang T, Hu B, Zhang M, Guo S. et al. The challenge and prospect of mRNA therapeutics landscape. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;40:107534. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhary N, Weissman D, Whitehead KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:817–38. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramanathan S, Shenoda BB, Lin Z, Alexander GM, Huppert A, Sacan A. et al. Inflammation potentiates miR-939 expression and packaging into small extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8:1650595. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1650595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Zhao P, Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang C, Liu Y. et al. Exosome-based Ldlr gene therapy for familial hypercholesterolemia in a mouse model. Theranostics. 2021;11:2953–65. doi: 10.7150/thno.49874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei Z, Batagov AO, Schinelli S, Wang J, Wang Y, El Fatimy R. et al. Coding and noncoding landscape of extracellular RNA released by human glioma stem cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1145. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01196-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald K, White S, Borodovsky A, Bettencourt BR, Strahs A, Clausen V. et al. A Highly Durable RNAi Therapeutic Inhibitor of PCSK9. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:41–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J. et al. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Q, Yu J, Kadungure T, Beyene J, Zhang H, Lu Q. ARMMs as a versatile platform for intracellular delivery of macromolecules. Nat Commun. 2018;9:960. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z, Shi J, Xie J, Wang Y, Sun J, Liu T. et al. Large-scale generation of functional mRNA-encapsulating exosomes via cellular nanoporation. Nat Biomed Eng. 2020;4:69–83. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0485-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wozniak AL, Adams A, King KE, Dunn W, Christenson LK, Hung WT, The RNA binding protein FMR1 controls selective exosomal miRNA cargo loading during inflammation. J Cell Biol. 2020. 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zietzer A, Hosen MR, Wang H, Goody PR, Sylvester M, Latz E. et al. The RNA-binding protein hnRNPU regulates the sorting of microRNA-30c-5p into large extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9:1786967. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1786967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nabet BY, Qiu Y, Shabason JE, Wu TJ, Yoon T, Kim BC. et al. Exosome RNA Unshielding Couples Stromal Activation to Pattern Recognition Receptor Signaling in Cancer. Cell. 2017;170:352–66.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung ME, Leonard JN. A platform for actively loading cargo RNA to elucidate limiting steps in EV-mediated delivery. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5:31027. doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.31027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Zhou X, Wei M, Gao X, Zhao L, Shi R. et al. In Vitro and in Vivo RNA Inhibition by CD9-HuR Functionalized Exosomes Encapsulated with miRNA or CRISPR/dCas9. Nano Lett. 2019;19:19–28. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Yang X, Sun W, Wu Q, Song Y, Yuan L. et al. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exosome Enrichment: A Proof-of-Concept Study for Exosome-Based Targeting Peptide Screening. Adv Biosyst. 2019;3:e1800275. doi: 10.1002/adbi.201800275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S, Dong Y, Wang Y, Sun W, Wei M, Yuan L. et al. Selective Encapsulation of Therapeutic mRNA in Engineered Extracellular Vesicles by DNA Aptamer. Nano Lett. 2021;21:8563–70. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrick WC, Pavitt GD. Protein Synthesis Initiation in Eukaryotic Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Borrelli DA, Yankson K, Shukla N, Vilanilam G, Ticer T, Wolfram J. Extracellular vesicle therapeutics for liver disease. J Control Release. 2018;273:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thietart S, Rautou PE. Extracellular vesicles as biomarkers in liver diseases: A clinician's point of view. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1507–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiklander OP, Nordin JZ, O'Loughlin A, Gustafsson Y, Corso G, Mäger I. et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26316. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauffman KJ, Dorkin JR, Yang JH, Heartlein MW, DeRosa F, Mir FF. et al. Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for mRNA Delivery in Vivo with Fractional Factorial and Definitive Screening Designs. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7300–6. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenton OS, Kauffman KJ, McClellan RL, Appel EA, Dorkin JR, Tibbitt MW. et al. Bioinspired Alkenyl Amino Alcohol Ionizable Lipid Materials for Highly Potent In Vivo mRNA Delivery. Adv Mater. 2016;28:2939–43. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tutucci E, Vera M, Biswas J, Garcia J, Parker R, Singer RH. An improved MS2 system for accurate reporting of the mRNA life cycle. Nat Methods. 2018;15:81–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojima R, Bojar D, Rizzi G, Hamri GC, El-Baba MD, Saxena P. et al. Designer exosomes produced by implanted cells intracerebrally deliver therapeutic cargo for Parkinson's disease treatment. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1305. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03733-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corley M, Burns MC, Yeo GW. How RNA-Binding Proteins Interact with RNA: Molecules and Mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2020;78:9–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng H, Wan C, Zhang Z, Chen H, Li Z, Jiang H. et al. Specific interaction of an RNA-binding protein with the 3'-UTR of its target mRNA is critical to oomycete sexual reproduction. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1010001. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thangaraj MP, Furber KL, Gan JK, Ji S, Sobchishin L, Doucette JR. et al. RNA-binding Protein Quaking Stabilizes Sirt2 mRNA during Oligodendroglial Differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:5166–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.775544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoekenbroek RM, Lambert G, Cariou B, Hovingh GK. Inhibiting PCSK9 - biology beyond LDL control. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;15:52–62. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutcheson JD, Goettsch C, Pham T, Iwashita M, Aikawa M, Singh SA. et al. Enrichment of calcifying extracellular vesicles using density-based ultracentrifugation protocol. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:25129. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.25129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Sequence of aptamers and releasers. Table S2: Sequences of primers. Table. S3: Sequences of plasmids. Figure S1: Design of Ldlr aptamer and Ldlr releaser. Figure S2: qPCR analysis of Ct value of GAPDH in EVs. Figure S3: Construction of EVLdlr-MS2 and EV loading efficiency of Ldlr mRNA. Figure S4. Construction and characterization of EVLdlr releaser. Figure S5: LDLR expression in AML12 cells co-cultured with increasing amounts of EVLdlr-MS2. Figure S6: Competitive binding of Ldlr releaser with Ldlr aptamer. Figure S7: Illustration of Ldlr gene deletion strategy and primer design. Figure S8: Body weights of mice with different treatments.