Abstract

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) are valuable genetic markers due to their co-dominant inheritance, multi-allelic and reproducible nature. They have been largely used for exploiting genetic architecture of plant germplasms, phylogenetic analysis, and mapping studies. Among the SSRs, di-nucleotide repeats are the most frequent of the simple repeats distributed throughout the plant genomes. In present study, we aimed to discover and develop di-nucleotide SSR markers by using the whole genome re-sequencing (WGRS) data from Cicer arietinum L. and C. reticulatum Ladiz. A total of 35,329 InDels were obtained in C. arietinum, whereas 44,331 InDels in C. reticulatum. 3387 InDels with 2 bp length were detected in C. arietinum, there were 4704 in C. reticulatum. Among 8091 InDels, 58 di-nucleotide regions that were polymorphic between two species were selected and used for validation. We tested primers for evaluation of genetic diversity in 30 chickpea genotypes including C. arietinum, C. reticulatum, C. echinospermum P.H. Davis, C. anatolicum Alef., C. canariense A. Santos & G.P. Lewis, C. microphyllum Benth., C. multijugum Maesen, C. oxyodon Boiss. & Hohen. and C. songaricum Steph ex DC. A total of 244 alleles were obtained for 58 SSR markers giving an average of 2.36 alleles per locus. The observed heterozygosity was 0.08 while the expected heterozygosity was 0.345. Polymorphism information content was found to be 0.73 across all loci. Phylogenetic tree and principal coordinate analysis clearly divided the accessions into four groups. The SSR markers were also evaluated in 30 genotypes of a RIL population obtained from an interspecific cross between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum. Chi-square (χ2) test revealed an expected 1:1 segregation ratio in the population. These results demonstrated the success of SSR identification and marker development for chickpea with the use of WGRS data. The newly developed 58 SSR markers are expected to be useful for chickpea breeders.

Subject terms: Plant molecular biology, Plant sciences, Genomic analysis, Sequencing, Software

Introduction

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is one of the valuable cool-season grain legume crops in the world. It is a self-pollinated and diploid plant (2n = 2x = 16) with a genome size of ~ 740 Mb1 which is considerably less than other important legume crops like pea, lentil, alfalfa, soybean and peanut2. The genus Cicer L. belongs to the family Fabaceae, subfamily Faboideae and contains a total of 49 taxa with 9 annuals and 40 perennials3–6. Toker et al.7 has been recently introduced a new annual wild Cicer species, thereby increasing the count to 10 annual species. C. arietinum is solely cultivated species of the genus. C. reticulatum is considered to be the wild progenitor of the cultivated chickpea8. It is crossable with the cultivated chickpea and possesses 2n = 2x = 16 chromosommes with a smaller genome size of 416 Mb than that of the cultivated chickpea9.

Chickpea plays valuable roles in human diet as a rich source of dietary proteins, complex carbohydrates and micronutrients such as iron, potassium and zinc as well as vitamins A and B in addition to folate and thiamine10. Because of its capacity of biological fixation of atmospheric nitrogen through nodulation with Rhizobium species, it is an advantageous crop in crop rotation11. Also, chickpea is the most important cool season food legume in the arid and semi-arid areas under rainfed conditions12. Globally, harvested area was approximately 14.8 million ha and total production was almost 15.1 million tons of chickpeas in 202013. It is widely grown and consumed in India, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey13.

Various biotic and abiotic factors have been affecting the chickpea production in the worldwide14,15. Due to limited genetic diversity in cultivated chickpea, it has been restricted achievement in respect to efforts for increasing the productivity16. Conventional methods have been used in crop breeding and tolerance to the environmental stresses while molecular breeding approaches have potential to accelerate the process of developing new cultivars. Also, the effective usage of plant genetic resources in breeding might be possible with the awareness and information of genetic variation present within individuals or populations.

Molecular markers explore the genetic diversity at the DNA level and have the capability to reflect the precise genetic diversity between genotypes17. In chickpea, random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)18–20, amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)21,22, simple sequence repeat (SSR)23, inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR)24–26 and internal transcribed spacer (ITS)27 have been used for genetic diversity analysis in different germplasm. Recently, an extensive development has been made regarding the improvement of several genomic or transcript-based SSR markers and SNP markers and their deployment in the large-scale genomics and breeding programs in chickpea28–35. In contrast to SNP markers, SSRs are very convenient and easy to use. SSRs can be found in both coding and noncoding regions of all higher organisms. The genome wide occurrence, co-dominant inheritance, highly polymorphic and multi-allelic nature promote wide utilization of SSRs36–38. Earlier, the usual protocol for isolation microsatellite sequences was utilization of microsatellite-enriched libraries by cloning and Sanger sequencing method, which was costly, difficult, and time consuming39.

Recently, development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has prompted the fast and cost-effective SSR discovery in many crops. There are now numerous methods that apply NGS for genotyping, reduced representation libraries (RRLs), restriction-site-associated DNA sequencing (RADseq), genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), whole-genome resequencing (WGRS)40–42. WGRS is more appropriate for pre-breeding activities where less number of elite parents, landraces and wild species require to be examined delicately for genome variation (SNPs, CNV, structural variation) and association studies43. Efficiency of WGRS have been shown in many such crops such as rice44,45, sorghum46, cotton47, soybean48, tomato49, and chickpea50–53. In view of above prospects, genome-wide SSR markers were developed in chickpea in the present study. The utility of these developed markers in F6 population derived from an interspecific cross between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum was accessed. The cross-transferability of these markers was also examined across 30 chickpea genotypes including cultivated and wild types.

Results

Genotyping

A total of 2.01 GB and 2.16 GB raw sequence reads of C. arietinum and C. reticulatum were generated from 150 bp paired-end sequencing. C. arietinum had 34.77 M reads and 33% guanine-cytosine (GC) content while C. reticulatum had 33.60 M reads and 34% GC content. The means of reads mapped to the C. arietinum reference genome were 97.56% and 96.62% in C. arietinum and C. reticulatum, respectively.

Variant detection

Using variant calling pipeline, 3.9 M and 4.7 M variants were initially detected in C. arietinum and C. reticulatum genome, respectively. Out of all variants, a total of 3.26 M SNPs were identified in C. arietinum, by contrast 3.93 M in C. reticulatum compared to the reference genome. In total, 35,329 and 44,331 InDels were identified in the species of C. arietinum and C. reticulatum, respectively. A total of 3387 InDels with 2 bp length was detected in C. arietinum, there was 4704 in C. reticulatum. Among 8091 InDels, 58 di-nucleotide regions that were polymorphic between two species were selected and used for primer design (Table 1).

Table 1.

The primer sequences of the 58 SSR markers developed and used in this study.

| Markers | Physical position | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (3′–5′) | Motif | Product length (bp) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. arietinum | C. reticulatum | Reference genome (C. arietinum) | |||||

| SSR1 | 19,011,134–19,011,210 | CTTCCACGCGAGAGAAAAAC | TGGCCAATTTGAAAAGAAAA | CT | 176 | 180 | 182 |

| SSR2 | 55,753,401–55,753,477 | TTGCCCTGATTTGAGATGTG | TTGGAAATTCAACCTACACAAAAA | TA | 158 | 160 | 160 |

| SSR3 | 19,011,133–19,011,211 | CTTCCACGCGAGAGAAAAAC | TGGCCAATTTGAAAAGAAAA | CT | 176 | 180 | 182 |

| SSR4 | 889,577–889,653 | TGCCAGTTTTTAACAGCATGA | CAGCATTATCTGCAAAAACAAA | AT | 164 | 154 | 164 |

| SSR5 | 994,011–994,087 | TCCTTGTTTTAATTCCTCCATTG | TGAGACTCGACGCATTTAAGAA | TA | 164 | 162 | 164 |

| SSR6 | 1,322,967–1,323,044 | TTCATGATGAGTGAATGGATGAG | AAATGGTGCACGTGTTTGTT | AT | 167 | 157 | 167 |

| SSR7 | 7,315,917–7,315,993 | TGTTGCTGAGAAATTAAAAGAATGA | GCAACCAGACAAAACACGAG | TG | 231 | 229 | 231 |

| SSR8 | 13,721,274–13,721,350 | CCAAATCCACTCCACCAGAT | ATGGGTCGAACAGGTGAAAC | AT | 154 | 152 | 154 |

| SSR9 | 21,156,335–21,156,411 | CCATTGTTTTGACGGTGTTG | ATGGAGGAGTGGGTTTGACA | TA | 185 | 183 | 185 |

| SSR10 | 25,727,833–25,727,909 | CGTTTGTTTGTTTTCATACACG | CACACAAATCTAGTCCCTTGAGA | AG | 154 | 152 | 154 |

| SSR11 | 32,040,766–32,040,842 | TCTCACAGCAGTGGTCCTCTT | AATGTCAAATTGAAGCCACCT | CT | 153 | 151 | 153 |

| SSR12 | 47,883,120–47,883,196 | CGCAGTGTGCAGAACAGAGA | TGAGAAAAGTGAAAAATGGAAGA | TC | 164 | 162 | 164 |

| SSR13 | 709,972–710,050 | GAAGTTGAACACAGCCTCGTT | CAGAAAGAAGGACCAAAATTGTAA | TA | 239 | 237 | 239 |

| SSR14 | 3,754,394–3,754,472 | GATCCTATGACGGCCAAGAT | CAATGTGGCACTAGAATAGCTG | TC | 179 | 171 | 181 |

| SSR15 | 4,508,947–4,509,025 | GATGAATTGCAATGCCCACT | TGAGACCATACTTTTGCATCG | GA | 152 | 148 | 154 |

| SSR16 | 5,702,105–5,702,183 | TTAGGCACACTTCCCATCAA | ACCCCACTTGTGATTTTTGC | AT | 150 | 148 | 150 |

| SSR17 | 5,706,723–5,706,801 | CTCGCAAAAGAATGAATCACA | CACCAAATATATCAGAGTTCTCATGG | AT | 150 | 148 | 150 |

| SSR18 | 7,220,178–7,220,256 | CCTGCATGCATCTCTCTCAT | TTGAACAGCATTGCCATCAT | AT | 205 | 199 | 205 |

| SSR19 | 11,523,580–11,523,658 | AGCTCCGGACCTTTGAAATA | CCAGAATAGGTGGGGTTTCA | GA | 163 | 161 | 163 |

| SSR20 | 12,063,993–12,064,071 | TCATCCTATTTTTGTGTATAAAATCGT | TGTTATTTTAGGATTTGTCAAGGTT | AG | 229 | 227 | 229 |

| SSR21 | 25,623,108–25,623,186 | TGTTGGTGGCTCAACTATCAT | TGCGTTTTAGTTCAAACAACCTT | AG | 184 | 182 | 184 |

| SSR22 | 26,072,281–26,072,359 | AGTGTGAATCAATCTGCTCTGA | TTAAACAAATCAAAGCATTGAAAA | GT | 158 | 156 | 160 |

| SSR23 | 30,200,833–30,200,911 | TACAATTCAAAGCGGCACAA | CCCTTTGTGATATTTCTCGTGTT | TC | 156 | 154 | 156 |

| SSR24 | 34,024,156–34,024,235 | TGATCACATTGCATCCATCTT | TGGAAATTGTGAGATTAAAACATAGAA | AT | 179 | 177 | 179 |

| SSR25 | 40,487,098–40,487,176 | AAGCGAAGCGTACCTTTGAA | TCCTCTCCGCACTCTCTCTC | AG | 139 | 137 | 139 |

| SSR26 | 514,664–514,710 | TTGAATCACCATCTGAAAAATCA | GGGCAAGCTCCAAGTACAGT | GA | 311 | 309 | 311 |

| SSR27 | 12,151,893–12,151,939 | AACCTTTTTGAGATTGATTGAAGG | CCTTCAAATACACCAAAGGACA | TA | 187 | 185 | 187 |

| SSR28 | 13,690,483–13,690,529 | TCCACAATGGAGATAAGAAAGC | TTGACTTGATTGGTTTGAGAGAA | CT | 156 | 154 | 156 |

| SSR29 | 20,110,687–20,110,733 | TTTTGTATTGTCAATTTCGCATT | TTTCTCTCCCCCGTTACTCA | AG | 172 | 170 | 172 |

| SSR30 | 22,768,737–22,768,783 | AAGTGATGGACACATGCAATCT | GGGATACGGATTTGGAGGGTA | AC | 327 | 325 | 327 |

| SSR31 | 30,049,660–30,049,706 | CCACATGTTTCGTAGTGTTATCTCC | CTTGATTGAATTAAAGTTTGAAAAAG | AT | 164 | 162 | 164 |

| SSR32 | 3,762,999–3,763,051 | AAACACAACAAAAGATCACATGG | TTTCAAAGAACCCCAACAGAA | AT | 314 | 312 | 314 |

| SSR33 | 4,183,287–4,183,339 | TCCTTTTCCAAATTCCAATGA | GGAGCAGAGTGTGTGTGTGG | TC | 153 | 151 | 153 |

| SSR34 | 5,072,765–5,072,817 | CAATTACATGTTAGATGACGTGCT | TGTTGCACACAAAAAGTTAGACG | TA | 372 | 370 | 372 |

| SSR35 | 7,847,913–7,847,965 | TGGCCATTGGATTGGTTTAT | TGAAAACAAAAATGAACATGGAA | TA | 130 | 128 | 130 |

| SSR36 | 10,455,187–10,455,239 | TCTTGTAAGTACGGTGGCAGTG | TATTGTTGCAAGAAATTGTCTCTTT | AC | 150 | 146 | 150 |

| SSR37 | 822,924–823,003 | TGTCCAAGAACGACAATGTG | CGACTTAACATTAGCAATAGTCTTCAA | CA, AG | 154 | 152 | 154 |

| SSR38 | 7,250,162–7,250,240 | AAATAGTCCATAAGCTTCACCATAC | TTGATTAATTACCACAACTTTATATGC | AT | 152 | 150 | 152 |

| SSR39 | 16,688,457–16,688,535 | TGAGTGTTGTTGTTACCTTTTGC | CATCGACACAATTCCAAGGTT | GA | 157 | 155 | 157 |

| SSR40 | 20,328,085–20,328,163 | AAAATTTAGAAAATGGGAGAAAACA | TGTGACATATGCATTTGCTCTTAC | GA | 186 | 184 | 186 |

| SSR41 | 24,316,422–24,316,500 | AAAAACATCGAAACCAGCAAA | ACGTGTTCCCATTGGTTAGC | AG | 341 | 339 | 341 |

| SSR42 | 24,874,026–24,874,104 | AGAAAAAGAGGACGAACAGAAA | TCTTTTGCTCCGTTGGATTT | AT | 153 | 149 | 153 |

| SSR43 | 27,746,809–27,746,887 | GAATCGGAACTAAAACCGAAA | TCTCTCCCTCCCTCCCTCTA | GA | 245 | 243 | 245 |

| SSR44 | 29,532,448–29,532,526 | TCAGAAATAGGAAAAGCAGTTTCA | CCTGAATGCCAAAATAAGGTTC | TA | 205 | 203 | 205 |

| SSR45 | 30,278,651–30,278,729 | CCCGGTTTGTCGTGTCTATC | GAAAGGTGTTGGTTGGTGAT | TC | 173 | 171 | 173 |

| SSR46 | 30,896,220–30,896,298 | TGGTTTTGTTACATTGCATCTG | TGCACATCACACACAAGGAA | TG | 221 | 219 | 221 |

| SSR47 | 36,420,939–36,421,017 | TGCCATTGTTGAAAGCACAT | TCAAATGCTTCATTGCCATT | AT | 317 | 313 | 317 |

| SSR48 | 1,077,194–1,077,272 | AACGTCCACAATGAGAAAAGC | GCCATTTCTTGCAAAGTTCA | TG | 198 | 196 | 198 |

| SSR49 | 207,413–207,491 | TAACTTGGGCTTCGAGGAGA | AACTCTGCCGTATGCTTTCC | AG | 155 | 151 | 155 |

| SSR50 | 5,819,504–5,819,583 | TGGTTGTTGCTATTTCAACCT | TGATTTGGGTCTCTTTTTGCTT | AT | 200 | 198 | 200 |

| SSR51 | 31,121,065–31,121,143 | TTGTCTGAAGAATGCCACCTT | TTTGTGAAGCGTCACTCAGG | AT | 144 | 140 | 144 |

| SSR52 | 31,568,270–31,568,348 | TCAACCCACGTGCTTTTGTa | CCGGTCAATATTTTGCGAGT | AT | 196 | 194 | 196 |

| SSR53 | 33,184,427–33,184,505 | AAAACATTCTGCAATTTTGTTTTA | TCTCGTTGTTCAAACCCAAAC | AT | 162 | 158 | 162 |

| SSR54 | 33,645,811–33,645,889 | TGCCTTTGTACTCTTCTATATTTGG | CAAATTGTTTGCCTTTTGTTTG | AT | 230 | 228 | 230 |

| SSR55 | 36,678,457–36,678,535 | GTTCGTCATACGATAAGAAGAGAAA | TATAGCGTCGGTTGTCAATTTTT | AT | 150 | 146 | 150 |

| SSR56 | 37,082,804–37,082,882 | GCACCCACACCTGCTAAGAG | TCCCAAGAACGTCTTTCACC | TC | 162 | 152 | 162 |

| SSR57 | 4,181,347–4,181,425 | AAGTCCTAATATTGGGCTGTTTAGA | TATGCATGCAGAAACACACG | AT | 152 | 150 | 152 |

| SSR58 | 2,837,886–2,837,964 | GGTGTGATGTGTGGCAGAGA | GCCCGGAAATACAGGGATAC | AG | 186 | 182 | 186 |

SSR validation in RIL population

Designed primer pairs were used for validation in 30 chickpea genotypes of F6 population obtained from an interspecific cross between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum. Out of SSR31 and SSR32, all primers were successfully amplified. The obtained PCR products were loaded on a polyacrylamide gel, and allele sizes were determined by comparing with C. arietinum and C. reticulatum. The difference of allele sizes was also confirmed in the gel. It was seen that all 30 genotypes carried one of the alleles which the parents had. While SSR5 and SSR10 produced suitable alleles in 30 RIL genotypes for 2-nucleotide polymorphism between female and male parents, SSR14 primer produced suitable alleles for 8-nucleotide polymorphism and SSR18 primer for 6-nucleotide polymorphism between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum (Table 1).

Chi-square (χ2) values were calculated for each marker to test the fit of the markers in 30 genotypes representing the RIL population to the expected 1:1 expression ratio. Markers deviating from expected Mendelian ratios were determined by chi-square analysis (Table 2). According to the results, it was determined that the markers were suitable for 1:1 expansion ratio, since the calculated p values for all markers except SSR20 were greater than 0.05.

Table 2.

Chi-square (χ2) values for each marker to test the fit of the markers in the RIL population to the expected 1:1 expression ratio.

| Markers | Allele size (bp) | Chi-square values | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. arietinum | C. reticulatum | |||

| SSR1 | 176 | 180 | 0.154 | 0.695 |

| SSR2 | 158 | 160 | 1.000 | 0.317 |

| SSR3 | 176 | 180 | 3.846 | 0.050 |

| SSR4 | 164 | 154 | 0.034 | 0.853 |

| SSR5 | 164 | 162 | 0.133 | 0.715 |

| SSR6 | 167 | 157 | 0.037 | 0.847 |

| SSR10 | 154 | 152 | 1.815 | 0.178 |

| SSR11 | 153 | 151 | 2.133 | 0.144 |

| SSR14 | 179 | 171 | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| SSR15 | 152 | 148 | 0.040 | 0.841 |

| SSR16 | 150 | 148 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SSR17 | 150 | 148 | 0.040 | 0.841 |

| SSR18 | 205 | 199 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SSR19 | 163 | 161 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SSR20 | 229 | 227 | 26.133 | 0.000 |

| SSR21 | 184 | 182 | 2.793 | 0.095 |

| SSR22 | 158 | 156 | 0.926 | 0.336 |

| SSR23 | 156 | 154 | 2.286 | 0.131 |

| SSR24 | 179 | 177 | 0.048 | 0.827 |

| SSR26 | 311 | 309 | 0.310 | 0.577 |

| SSR27 | 187 | 185 | 0.167 | 0.683 |

| SSR29 | 172 | 170 | 0.615 | 0.433 |

| SSR30 | 327 | 325 | 0.333 | 0.564 |

| SSR37 | 154 | 152 | 0.310 | 0.577 |

| SSR38 | 152 | 150 | 0.310 | 0.577 |

| SSR39 | 157 | 155 | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| SSR40 | 186 | 184 | 0.034 | 0.853 |

| SSR41 | 341 | 339 | 0.142 | 0.705 |

| SSR42 | 153 | 149 | 0.310 | 0.577 |

| SSR43 | 245 | 243 | 0.533 | 0.465 |

| SSR45 | 173 | 171 | 0.333 | 0.564 |

| SSR46 | 221 | 219 | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| SSR47 | 317 | 313 | 0.926 | 0.336 |

| SSR51 | 144 | 140 | 0.533 | 0.465 |

SSR diversity in cultivated and wild populations

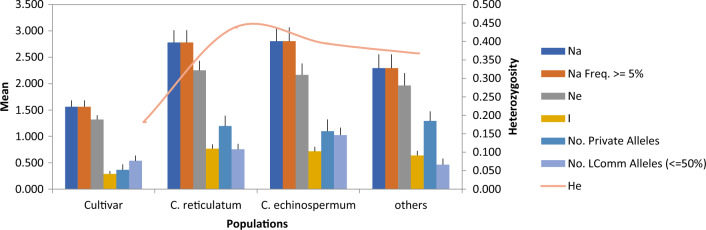

For genetic diversity analysis, 30 genotypes obtained from cultivated and wild species were tested in polyacrylamide gel, bands were scored according to allele sizes. As a result of the analysis, a total of 244 alleles belonging to 41 different SSR loci were determined in 30 chickpea genotypes (Table 3). At the population level, allelic diversity in cultivated and wild populations was shown in Fig. 1. Total allele distribution was 63 in cultivars and 311 in wild genotypes. While a total of 110 alleles were determined in the genotypes of the C. reticulatum, 112 alleles were observed in the genotypes of the C. echinospermum. 89 alleles were determined in the population from distantly related wild species. The mean number of alleles (Na) for 30 genotypes was 2.36 (Table 3). The highest number of alleles was obtained from the primers SSR3, SSR58 and SSR39 (Table 3). The number of effective alleles (Ne) varied between 0.75 and 3.74. Nei's54 observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity values were calculated as 0.08 and 0.34, respectively. The mean of polymorphism information content (PIC) was measured as 0.73 (Table 3). The highest PIC value was observed at the SSR21 (0.90) loci, followed by the SSR56 (0.88), SSR54 (0.86), SSR4 (0.85), SSR7 (0.83) and SSR34 (0.83) loci. The lowest PIC value was found in the SSR9 (0.51) locus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of genetic diversity statistics for 30 chickpea genotypes.

| Markers/loci | N | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | uHe | F | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSR2 | 7.000 | 3.750 | 2.766 | 1.003 | 0.083 | 0.525 | 0.566 | 0.675 | 0.826 |

| SSR3 | 7.250 | 5.250 | 3.743 | 1.382 | 0.163 | 0.665 | 0.718 | 0.788 | 0.781 |

| SSR4 | 7.250 | 3.750 | 2.986 | 1.122 | 0.071 | 0.617 | 0.663 | 0.908 | 0.854 |

| SSR5 | 7.250 | 2.500 | 2.157 | 0.726 | 0.167 | 0.432 | 0.466 | 0.680 | 0.645 |

| SSR6 | 6.750 | 1.250 | 1.038 | 0.064 | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.036 | -0.077 | 0.637 |

| SSR7 | 6.250 | 3.750 | 3.340 | 1.101 | 0.077 | 0.586 | 0.643 | 0.894 | 0.833 |

| SSR8 | 6.750 | 2.750 | 1.783 | 0.716 | 0.100 | 0.418 | 0.454 | 0.828 | 0.749 |

| SSR9 | 5.750 | 1.500 | 1.320 | 0.267 | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.201 | 1.000 | 0.51 |

| SSR10 | 5.500 | 1.000 | 0.938 | 0.155 | 0.031 | 0.107 | 0.115 | 0.709 | 0.664 |

| SSR11 | 6.250 | 3.500 | 3.056 | 1.128 | 0.154 | 0.645 | 0.702 | 0.740 | 0.816 |

| SSR12 | 6.000 | 2.250 | 1.900 | 0.624 | 0.000 | 0.385 | 0.425 | 1.000 | 0.689 |

| SSR13 | 5.000 | 1.750 | 1.454 | 0.372 | 0.071 | 0.237 | 0.257 | 0.682 | 0.826 |

| SSR16 | 7.000 | 2.500 | 1.819 | 0.595 | 0.217 | 0.335 | 0.366 | 0.243 | 0.608 |

| SSR17 | 4.750 | 2.000 | 1.497 | 0.540 | 0.550 | 0.330 | 0.358 | -0.559 | 0.817 |

| SSR18 | 5.250 | 3.250 | 2.983 | 0.974 | 0.000 | 0.523 | 0.573 | 1.000 | 0.690 |

| SSR19 | 6.750 | 1.500 | 1.322 | 0.290 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.210 | 1.000 | 0.731 |

| SSR21 | 5.250 | 3.250 | 2.644 | 0.937 | 0.000 | 0.508 | 0.554 | 1.000 | 0.898 |

| SSR25 | 5.750 | 2.000 | 1.753 | 0.552 | 0.167 | 0.369 | 0.432 | 0.610 | 0.736 |

| SSR28 | 5.250 | 1.500 | 1.431 | 0.326 | 0.050 | 0.230 | 0.283 | 0.762 | 0.717 |

| SSR33 | 6.750 | 2.000 | 1.766 | 0.537 | 0.000 | 0.344 | 0.376 | 1.000 | 0.615 |

| SSR34 | 7.000 | 2.250 | 2.083 | 0.594 | 0.000 | 0.340 | 0.369 | 1.000 | 0.827 |

| SSR35 | 5.250 | 1.500 | 1.204 | 0.199 | 0.000 | 0.112 | 0.121 | 1.000 | 0.796 |

| SSR36 | 7.000 | 1.750 | 1.462 | 0.406 | 0.094 | 0.271 | 0.297 | 0.534 | 0.545 |

| SSR37 | 5.750 | 2.000 | 1.637 | 0.495 | 0.063 | 0.305 | 0.344 | 0.619 | 0.599 |

| SSR38 | 3.000 | 0.750 | 0.750 | 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.143 | 1.000 | 0.814 |

| SSR39 | 7.000 | 4.000 | 3.480 | 1.141 | 0.155 | 0.596 | 0.644 | 0.807 | 0.773 |

| SSR42 | 6.000 | 1.500 | 1.331 | 0.276 | 0.000 | 0.186 | 0.233 | 1.000 | 0.645 |

| SSR43 | 7.500 | 2.000 | 1.683 | 0.512 | 0.063 | 0.325 | 0.350 | 0.619 | 0.717 |

| SSR44 | 6.750 | 2.250 | 1.920 | 0.588 | 0.031 | 0.349 | 0.386 | 0.644 | 0.615 |

| SSR45 | 6.750 | 2.750 | 2.140 | 0.700 | 0.077 | 0.381 | 0.413 | 0.569 | 0.65 |

| SSR46 | 6.750 | 2.000 | 1.561 | 0.495 | 0.125 | 0.318 | 0.347 | 0.590 | 0.78 |

| SSR49 | 6.000 | 2.750 | 2.541 | 0.807 | 0.000 | 0.445 | 0.475 | 1.000 | 0.753 |

| SSR50 | 6.750 | 2.000 | 1.591 | 0.440 | 0.250 | 0.266 | 0.283 | 0.137 | 0.788 |

| SSR51 | 6.500 | 2.750 | 1.929 | 0.583 | 0.083 | 0.292 | 0.314 | 0.600 | 0.77 |

| SSR52 | 5.500 | 1.250 | 0.992 | 0.244 | 0.063 | 0.157 | 0.168 | 0.429 | 0.692 |

| SSR53 | 6.000 | 1.750 | 1.233 | 0.394 | 0.031 | 0.229 | 0.244 | 0.805 | 0.736 |

| SSR54 | 6.250 | 2.250 | 1.705 | 0.591 | 0.125 | 0.364 | 0.397 | 0.429 | 0.864 |

| SSR55 | 6.250 | 1.750 | 1.487 | 0.354 | 0.000 | 0.211 | 0.225 | 1.000 | 0.754 |

| SSR56 | 5.750 | 3.250 | 2.345 | 0.952 | 0.063 | 0.546 | 0.599 | 0.846 | 0.876 |

| SSR57 | 5.750 | 1.000 | 0.831 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.066 | 1.000 | 0.656 |

| SSR58 | 7.500 | 4.250 | 3.359 | 1.205 | 0.125 | 0.618 | 0.664 | 0.832 | 0.825 |

| Mean | 6.213 | 2.360 | 1.926 | 0.602 | 0.080 | 0.345 | 0.378 | 0.715 | 0.735 |

Number of alleles (Na), number of effective alleles (Ne), Shannon diversity index (I), Expected heterozygosity (He), Unexpected heterozygosity (uHe), Observed heterozygosity (Ho), Wright’s fixation index (F), Polymorphic information content (PIC).

Figure 1.

Allelic patterns and gene diversity across cultivated and wild populations. The figure shows comparison for number of alleles (Na), Number of alleles with frequency more than or equal to 5%, Number of effective alleles (Ne) and Number of private alleles, etc.

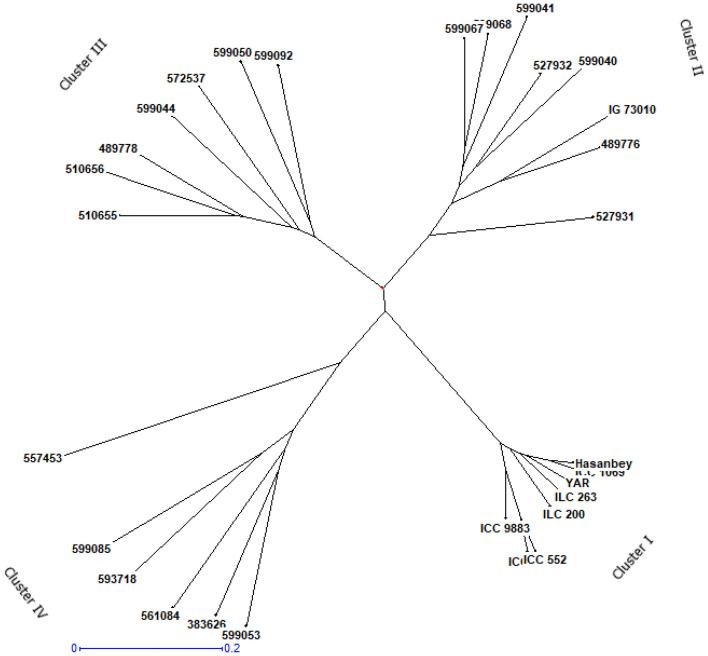

Phylogenetic tree consisting of 30 chickpea genotypes was constructed based on the UPGMA clustering method with newly developed SSRs (Fig. 2). The chickpea genotypes were divided into four clusters, indicating clear separation between wild and cultivated species. Cluster I contained cultivated chickpeas including four kabuli and four desi chickpeas. Cluster II, III and IV consist of wild chickpea species, each representing C. echinospermum, C. reticulatum and other wild chickpea species, respectively.

Figure 2.

UPGMA based dendrogram generated using SSR markers and 30 wild and cultivated chickpea genotypes.

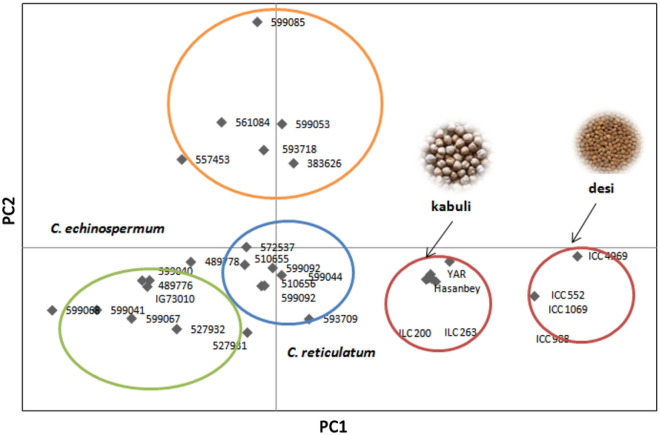

The PCoA analysis confirmed the clusters of the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3). Cultivated and wild genotypes did not cluster together. The two informative components explained 92.36% of the cumulative variance, PC1 and PC2 shared 53.72% and 38.64% variation, respectively.

Figure 3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the 30 chickpea genotypes genotypes with SSR markers.

Discussion

Using NGS technology is an effective tool for the identification of SSR markers

SSRs are valuable genetic markers due to their co-dominant inheritance, multi-allelic and reproducible nature55. In chickpea, large numbers of SSR markers have been identified and widely used for genetic diversity analysis, gene/QTL mapping, construction of linkage map, marker assisted selection (MAS)33,56–59. However, validation and selection of informative markers from such huge numbers of markers that show polymorphism in chickpea, is an excessive effort. In addition, the narrow genetic base in chickpea may can restrict use of the identified markers in genotyping studies because of their low intra-specific polymorphism among chickpea genotypes23,30. The NGS technologies have caused impressive advances in sequencing which creates high-throughput sequences to transform genotyping and plant breeding. It provides opportunities to perform high-throughput SSR identification. In present study, we developed genome-wide SSR markers from cultivated and wild chickpea genotypes. SSR marker development from genomic data has been reported for various crops such as sesame60, red clover61, peanut62, sweet potato63, faba bean64, lentil65.

Distribution of variants in C. arietinum and C. reticulatum genome

As a result of alignment to the reference genome of chickpea, a total of 3.26 M SNPs were identified in C. arietinum, by contrast 3.93 M in C. reticulatum. Previously, 51,632 SNPs were reported by 454 transcriptome sequencing of C. arietinum and C. reticulatum genotypes35. In addition, couple hundreds of SNPs were also studied using Solexa ⁄ Illumina sequencing, targeted amplicon sequencing, mining of expressed sequence tag libraries and sequencing of candidate genes30,66,67.

Validation and polymorphic potential of SSRs

The utilization of genetic diversity in chickpea genetic resources is very important in order to utilize collections and improve breeding studies. Genetic diversity analysis in chickpea was previously performed using RAPD18, AFLP68, STMS69, SSRs70,71. In this study, the effectiveness of the developed markers was evaluated in 30 chickpea genotypes obtained from cultivated and wild species as well as 30 chickpea genotypes of F6 population obtained from an interspecific cross between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum. The markers were effective for detection of a total of 244 alleles (Na). The mean of number of alleles (2.36) observed in this study are within the ranges revealed by various previous studies. For instance, the use of 33 SSR markers identifed a total of 111 alleles with an average of 3.7 alleles per locus in 155 chickpea genotypes72. Similarly, 27 SSRs were used to study genetic diversity in 50 chickpea accessions which reported a total of 81 alleles with an average of 3.0 alleles/locus73. In the present study, heterozygosity was detected in genotypes that ranged from 0.03 to 0.66 with mean of 0.34, which is similar to previous studies reported previously by Upadhyaya et al.74 and Hajibarat et al.75. Genetic diversity analysis showed that the average PIC value of SSR markers was 0.73, higher than PIC value of the SNPs76, STMS77,78, AFLP20 and SilicoDArT79 markers used to identify genetic variation in chickpea. Botstein et al.80 reported the PIC values of markers as highly informative (≥ 0.5), reasonably informative (0.50–0.25), or least informative (≤ 0.25). Our average PIC value (0.73) thus shows that the developed markers identified here are highly informative and greatly sufficient for showing relationships among genotypes, according to Meszaros et al.81. The principal coordinate analysis clearly separated the whole population into four clusters, and wild and cultivated types in seperate clusters. Results from the present study are consistant with the previous studies71,82 the grouping followed a clear pattern between cultivated chickpea and the wild species. It is also clear as the wild progenitor, Cicer reticulatum showed close proximity with the cultivated chickpea. The other close connection was seen between C. reticultum and C. echinospermum. It can be supposed from this study that cluster analysis shows the effectiveness of the designed markers.

The results of the present study revealed the success of SSR identification and marker development in chickpea using NGS genome data. The developed SSR markers were applied successfully for illuminating genetic diversity among cultivated and wild chickpea populations as well as validation in F6 population obtained from an interspecific cross between C. arietinum and C. reticulatum. Therefore, newly developed 58 SSR markers are potentially useful for genetic studies of chickpea.

In conclusion, NGS strategy led to the discovery of a large number of microsatellites markers, providing thousands of SSRs for validation in chickpea. These new SSRs will become significant molecular tools for chickpea genetic breeding programs. Later, these markers could be integrated in genetic maps to be utilized in MAS.

Materials and methods

Plant material

C. arietinum L., CA 2969 and C. reticulatum Ladiz., AWC 602 were used as a genetic material for WGRS analysis. CA 2969 and AWC 602 chickpea genotypes were registered by USDA-ARS and Akdeniz University, Department of Field Crops, respectively. The important traits for these genotypes were given in Table 4. Developed SSRs were validated in 30 chickpea lines from a RIL population earlier developed by Sari et al.83 and derived from an interspecific cross between CA 2969 and AWC 602. The markers were also used to assess the genetic diversity of cultivated and wild chickpea accessions including eight accessions of C. arietinum (four kabuli and four desi chickpeas), eight accessions of C. reticulatum, eight accessions of C. echinospermum P.H. Davis and six accessions of C. anatolicum Alef., C. canariense A. Santos & G.P. Lewis, C. microphyllum Benth., C. multijugum Maesen, C. oxyodon Boiss. & Hohen. and C. songaricum Steph ex DC. (Table 5). Seed samples of ICARDA and USDA are available directly from ICARDA (https://www.icarda.org/) and USDA (https://www.usda.gov/). The procurement of seeds of all cultivated and wild genotypes used in the present study complies with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Table 4.

Important morphological and the specific-known traits of the parents used for WGRS analysis (*Chrigui et al.15).

| Traits | Species | |

|---|---|---|

|

C. arietinum (CA 2969) |

C. reticulatum (AWC 602) |

|

| Kabuli/desi or wild | Kabuli | Wild |

| Flower color | White | Purple |

| Pod per axis | 2 | 1 |

| Seed color | Cream | Brown |

| 100-seed weight (g) | 34 | 21 |

| Cold tolerance | Susceptible | Tolerant |

| Resistance to pulse beetle | Susceptible | Resistant |

| Resistance to leafminer* | Susceptible | Resistant |

Table 5.

Cultivated and wild Cicer species.

| No. | Species | Genebank no | Kabuli/desi/wild | Annual/perennial | Genebank/institute | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C. arietinum | Hasanbey | Kabuli | Annual | EMARI | Turkey |

| 2 | C. arietinum | YAR | Kabuli | Annual | Akdeniz University | Turkey |

| 3 | C. arietinum | ILC 200 | Kabuli | Annual | ICARDA | Turkey |

| 4 | C. arietinum | ILC 263 | Kabuli | Annual | ICARDA | Turkey |

| 5 | C. arietinum | ICC 4969 | Desi | Annual | ICRISAT | Turkey |

| 6 | C. arietinum | ICC 552 | Desi | Annual | ICRISAT | Turkey |

| 7 | C. arietinum | ICC 988 | Desi | Annual | ICRISAT | Turkey |

| 8 | C. arietinum | ICC 1069 | Desi | Annual | ICRISAT | Turkey |

| 9 | C. reticulatum | 593709 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 10 | C. reticulatum | 510656 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 11 | C. reticulatum | 599092 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 12 | C. reticulatum | 599050 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 13 | C. reticulatum | 599044 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 14 | C. reticulatum | 510655 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 15 | C. reticulatum | 572537 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 16 | C. reticulatum | 489778 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 17 | C. echinospermum | 599040 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 18 | C. echinospermum | 599041 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 19 | C. echinospermum | 599068 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 20 | C. echinospermum | 527932 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 21 | C. echinospermum | 489776 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 22 | C. echinospermum | 599067 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 23 | C. echinospermum | 527931 | Wild | Annual | USDA | Turkey |

| 24 | C. echinospermum | IG 73010 | Wild | Annual | ICARDA | Turkey |

| 25 | C. canariense | 557453 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | Spain |

| 26 | C. anatolicum | 383626 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | Turkey |

| 27 | C. multijugum | 599085 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | Uzbekistan |

| 28 | C. microphyllum | 593718 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | India |

| 29 | C. oxyodon | 561084 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | Turkey |

| 30 | C. songaricum | 599053 | Wild | Perennial | USDA | Uzbekistan |

Eastern Mediterranean Agricultural Research Institute (EMARI), The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Experimental area

Plants belonging the parents (CA 2969 and AWC 602) and 30 cultivated and wild chickpea accessions were grown in separate pods in a greenhouse at the Faculty of Agriculture, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey (30°38′E, 36°53′N, 33 m above sea level) for genomic DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

DNA extraction process was carried out at Plant Molecular Biology Laboratuary, the Faculty of Agriculture, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey. Genomic DNA was extracted from 3 week-old young leaves of plants individually using the CTAB method as described by Doyle and Doyle84 with minor adjustments such as extra chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and 70% ethanol cleaning steps. DNA quality and quantity of each sample were estimated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels, and the amount was fixed to 100 ng/μL using lambda DNA as a reference.

Library preparation and sequencing

The genomic data from C. arietinum and C. reticulatum was used for construction of a HiSeq sequencing library using TruSeq DNA sample Prep kit LT, (set A) FC-121-2001 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. A reduced representative genomic library with a target insert size of about 350 bp were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq X to generate 150-bp paired-end reads at Macrogen Inc., (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). WGRS data of two available genotypes were deposited into the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence-Read Archive (SRA) database.

The raw data were demultiplexed using Je V1.285, a quality control was performed for FASTQ Sanger files using fastp86, and reads with a Phred quality score below 15 were trimmed87. The cleaned data were aligned with kabuli reference genome 1.01 using Bowtie 2 with default parameters88 in the Galaxy software (www.usegalaxy.org). The created BAM files (*.bam) were analyzed using Freebayes (Galaxy Version 1.1.0.46-0)89, with simple diploid calling and filtering, and a minimum of 20 × coverage for variant detection. The obtained variant files were filtered using VCFfilter (Galaxy Version 1.0.0) and SNPs were chosen. Insertions and deletions from individual (*.vcf) files were later merged into a single VCF file using VCF genotypes (Galaxy Version 1.0.0).

The combined variant file was processed using Microsoft Excel to eliminate duplicated regions and organize the SSRs according to their sizes. SSR regions which have 2 bp long and polymorphic between parents were checked using the Integrated Genome Browser V9.1.4.

Primer design

For designing the primer pairs from the flanking sequences of identified SSRs, Primer3 software90,91 was used with the parameters as follows: primer length of 18–27 nucleotides, melting temperatures of 55–65 °C, GC content of 30–70%, and predicted PCR products of 100–300 bp in length. The primer pairs were later controlled for possible duplication of sequences in the genome using IGB software.

The PCR reactions were performed using the M13 tailing PCR procedure92. The forward primers were tailed by adding an M13 sequence labeled with IRDye to the 5′ end. The following PCR protocol was applied: 95 °C initial denaturation for 5 min, 30 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing temperature 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, followed by 9 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and then a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were loaded onto 8% denatured polyacrylamide gel and separated by 4300 DNA analyzer (LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). 1 kb size marker was used to score markers as 1 or 0 for the presence and absence of alleles.

Statistical analyses

RIL data was analyzed using MINITAB 19 software. A Chi square (χ2) test was used to assess goodness of fit to the observed segregation ratios followed 3:1 ratio in the RIL population.

Genetic diversity and phylogeny analysis

Genetic diversity parameters such as number of alleles (Na), number of effective alleles (Ne), Shannon diversity index (I), expected heterozygosity (He), unexpected heterozygosity (uHe), observed heterozygosity (Ho) and Wright’s fixation index (F) were shown using GenAlEx 6.593. The phylogenetic tree was constructed in DARwin ver 5.0 software94 using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA)95 clustering method and modified in FigTree v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed with GenAlEx 6.5 to evaluate the genetic relationships between populations. The Excel microsatellite toolkit96 was used to measure polymorphism.

Acknowledgements

This study was produced PhD thesis of the first author, DS. Authors are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful input on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author contributions

C.T. and D.S. designed the research and methodology. D.S. and H.S. conducted laboratory studies and C.I. analyzed the sequence data. C.T. and D.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors are thankful to the funding provided by Akdeniz University Scientific Research Project Coordination Unit with the project no: FDK-2019-4122.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence-Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number of PRJNA926661.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Varshney RK, et al. Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:240–246. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, et al. Investigating drought tolerance in chickpea using genome-wide association mapping and genomic selection based on whole-genome resequencing data. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:190. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Maesen, L. J. G., Maxted, N., Javadi, F., Coles, S. & Davies, A. M. R. Taxonomy of the genus Cicer revisited. Chickpea Breed. Manag. CAB Int. Wallingford 14–46 (2007).

- 4.Dönmez AA. Cicer uludereensis Dönmez: A new species of Cicer (Chickpea) (Fabaceae) from around the Fertile Crescent. SE Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2011 doi: 10.3906/bot-1001-283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozturk, M. Revision of the genus Cicer L. Turk. Morphol. Palynol. Cytotaxonomical Mol. Phylogenetic Methods Anal. Seed Protein Elem. Contents Ph Thesis Grad. Sch. Nat. Appl. Sci. Selçuk Univ. Konya Turk. (2011).

- 6.Toker C, Uzun B, Ceylan FO, Ikten C. Chickpea. Alien Gene Transf. Crop Plants. 2014;2:121–151. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-9572-7_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toker C, et al. Cicer turcicum: A new Cicer species and its potential to improve chickpea. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:662891. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.662891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Maesen, L. J. G. Origin, history and taxonomy of chickpea, in The Chickpea 11–34 (1987).

- 9.Gupta S, et al. Draft genome sequence of Cicer reticulatum L., the wild progenitor of chickpea provides a resource for agronomic trait improvement. Dna Res. 2017;24:1–10. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaur PM, et al. Inheritance of protein content and its relationships with seed size, grain yield and other traits in chickpea. Euphytica. 2016;209:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s10681-016-1678-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herridge DF, Rupela OP, Serraj R, Beck DP. Screening techniques and improved biological nitrogen fixation in cool season food legumes. Euphytica. 1993;73:95–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00027186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammed A, Tana T, Singh P, Korecha D, Molla A. Management options for rainfed chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) in northeast Ethiopia under climate change condition. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017;16:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2016.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FAOSTAT. FAOSTAT, FAO Statistical Databases (2022).

- 14.Bakir, M., Sari, D., Sari, H., Waqas, M. & Atif, R. M. Chickpea wild relatives: Potential hidden source for the development of climate resilient chickpea varieties, in Wild Germplasm for Genetic Improvement in Crop Plants 269–297 (2021). 10.1016/B978-0-12-822137-2.00006-0.

- 15.Chrigui N, Sari D, Sari H, Eker T, Cengiz M. F., Ikten C, Toker C, et al. Introgression of resistance to leafminer (Liriomyza cicerina Rondani) from Cicer reticulatum Ladiz. to C. arietinum L. and relationships between potential biochemical selection criteria. Agronomy. 2021;11:57. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11010057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roorkiwal M, et al. Allele diversity for abiotic stress responsive candidate genes in chickpea reference set using gene based SNP markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:248. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui C, Mei H, Liu Y, Zhang H, Zheng Y. Genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium of an association-mapping panel revealed by genome-wide SNP markers in sesame. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1189. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iruela M, Rubio J, Cubero JI, Gil J, Millan T. Phylogenetic analysis in the genus Cicer and cultivated chickpea using RAPD and ISSR markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002;104:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s001220100751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javadi F, Yamaguchi H. RAPD and seed coat morphology variation in annual and perennial species of the genus Cicer L. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2004;51:783–794. doi: 10.1023/B:GRES.0000034584.43689.f1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talebi R, Naji AM, Fayaz F. Geographical patterns of genetic diversity in cultivated chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) characterized by amplified fragment length polymorphism. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;54:447–452. doi: 10.17221/399-PSE. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen TT, Taylor PWJ, Redden RJ, Ford R. Genetic diversity estimates in Cicer using AFLP analysis. Plant Breed. 2004;123:173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2003.00942.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan F, Clarke HJ, Yan G, Plummer JA, Siddique KHM. Identification of duplicates and fingerprinting of primary and secondary wild annual Cicer gene pools using AFLP markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007;54:519–527. doi: 10.1007/s10722-006-0008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sethy NK, Shokeen B, Edwards KJ, Bhatia S. Development of microsatellite markers and analysis of intraspecific genetic variability in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;112:1416–1428. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudupak MA, Akkaya MS, Kence A. Genetic relationships among perennial and annual Cicer species growing in Turkey assessed by AFLP fingerprinting. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;108:937–944. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amirmoradi B, Talebi R, Karami E. Comparison of genetic variation and differentiation among annual Cicer species using start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism, DAMD-PCR, and ISSR markers. Plant Syst. Evol. 2012;298:1679–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00606-012-0669-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aggarwal H, et al. Assessment of genetic diversity among 125 cultivars of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) of Indian origin using ISSR markers. Turk. J. Bot. 2015;39:218–226. doi: 10.3906/bot-1401-80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A, Devarumath RM, Ramarao S, Singh VP, Raina SN. Assessment of genetic diversity, and phylogenetic relationships based on ribosomal DNA repeat unit length variation and Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequences in chickpea (Cicer arietinum) cultivars and its wild species. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008;55:65–79. doi: 10.1007/s10722-007-9215-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millan T, et al. A consensus genetic map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) based on 10 mapping populations. Euphytica. 2010;175:175–189. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0157-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nayak SN, et al. Integration of novel SSR and gene-based SNP marker loci in the chickpea genetic map and establishment of new anchor points with Medicago truncatula genome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010;120:1415–1441. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gujaria N, et al. Development and use of genic molecular markers (GMMs) for construction of a transcript map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011;122:1577–1589. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thudi M, et al. Novel SSR markers from BAC-end sequences, DArT arrays and a comprehensive genetic map with 1,291 marker loci for chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaur R, et al. High-throughput SNP discovery and genotyping for constructing a saturated linkage map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) DNA Res. 2012;19:357–373. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiremath PJ, et al. Large-scale development of cost-effective SNP marker assays for diversity assessment and genetic mapping in chickpea and comparative mapping in legumes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012;10:716–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roorkiwal M, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping for breeding and genetics applications in chickpea and pigeonpea using the BeadXpress platform. Plant Genome. 2013;6:plantgenome2013-05. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2013.05.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deokar AA, et al. Genome wide SNP identification in chickpea for use in development of a high density genetic map and improvement of chickpea reference genome assembly. BMC Genom. 2014;15:708. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varshney RK, Graner A, Sorrells ME. Genic microsatellite markers in plants: Features and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naghavi MR, Monfared SR, Humberto G. Genetic diversity in Iranian chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) landraces as revealed by microsatellite markers. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2012;48:131–138. doi: 10.17221/185/2011-CJGPB. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asadi AA, Rashidi Monfared S. Characterization of EST-SSR markers in durum wheat EST library and functional analysis of SSR-containing EST fragments. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014;289:625–640. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan C, Li D, Sun S, Wang X, Zhu Z. Rapid development of microsatellite markers for Callosobruchus chinensis using Illumina paired-end sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davey JW, et al. Genome-wide genetic marker discovery and genotyping using next-generation sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:499–510. doi: 10.1038/nrg3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elshire RJ, et al. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaganathan D, Bohra A, Thudi M, Varshney RK. Fine mapping and gene cloning in the post-NGS era: Advances and prospects. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020;133:1791–1810. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03560-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, et al. Association analysis of frost tolerance in rye using candidate genes and phenotypic data from controlled, semi-controlled, and field phenotyping platforms. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang X, et al. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature. 2012;490:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang M, et al. The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:982–988. doi: 10.1038/ng.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mace ES, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals untapped genetic potential in Africa’s indigenous cereal crop sorghum. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Page JT, et al. Insights into the evolution of cotton diploids and polyploids from whole-genome re-sequencing. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2013;3:1809–1818. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Z, et al. Resequencing 302 wild and cultivated accessions identifies genes related to domestication and improvement in soybean. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:408–414. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin T, et al. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1220–1226. doi: 10.1038/ng.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lake L, Li Y, Casal JJ, Sadras VO. Negative association between chickpea response to competition and crop yield: Phenotypic and genetic analysis. Field Crops Res. 2016;196:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2016.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadras VO, Lake L, Li Y, Farquharson EA, Sutton T. Phenotypic plasticity and its genetic regulation for yield, nitrogen fixation and δ13C in chickpea crops under varying water regimes. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:4339–4351. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thudi M, et al. Whole genome re-sequencing reveals genome-wide variations among parental lines of 16 mapping populations in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:53–64. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0690-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, et al. Genome analysis identified novel candidate genes for ascochyta blight resistance in chickpea using whole genome re-sequencing data. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:359. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nei M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khajuria YP, et al. Development and integration of genome-wide polymorphic microsatellite markers onto a reference linkage map for constructing a high-density genetic map of chickpea. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winter P, et al. A linkage map of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genome based on recombinant inbred lines from a C. arietinum × C. reticulatum cross: Localization of resistance genes for fusarium wilt races 4 and 5. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;101:1155–1163. doi: 10.1007/s001220051592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaur R, et al. Advancing the STMS genomic resources for defining new locations on the intraspecific genetic linkage map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) BMC Genom. 2011;12:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choudhary, P. et al. Genetic structure and diversity analysis of the primary gene poolof chickpea using SSR markers. Genet. Mol. Res. 891–905 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Vadez V, et al. Assessment of ICCV 2 x JG 62 chickpea progenies shows sensitivity of reproduction to salt stress and reveals QTL for seed yield and yield components. Mol. Breed. 2012;30:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9594-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei W, et al. Characterization of the sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) global transcriptome using Illumina paired-end sequencing and development of EST-SSR markers. BMC Genom. 2011;12:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yates SA, et al. De novo assembly of red clover transcriptome based on RNA-Seq data provides insight into drought response, gene discovery and marker identification. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang J, et al. De novo assembly and characterisation of the transcriptome during seed development, and generation of genic-SSR markers in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) BMC Genom. 2012;13:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Z, et al. De novo assembly and characterization of root transcriptome using Illumina paired-end sequencing and development of cSSR markers in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) BMC Genom. 2010;11:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suresh S, et al. Development and molecular characterization of 55 novel polymorphic cDNA-SSR markers in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) using 454 pyrosequencing. Molecules. 2013;18:1844–1856. doi: 10.3390/molecules18021844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verma P, Shah N, Bhatia S. Development of an expressed gene catalogue and molecular markers from the de novo assembly of short sequence reads of the lentil (Lens culinaris M edik.) transcriptome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013;11:894–905. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varshney RK, et al. A comprehensive resource of drought-and salinity-responsive ESTs for gene discovery and marker development in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) BMC Genom. 2009;10:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hiremath PJ, et al. Large-scale transcriptome analysis in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), an orphan legume crop of the semi-arid tropics of Asia and Africa. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011;9:922–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh R, Singhal V, Randhawa GJ. Molecular analysis of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) cultivars using AFLP and STMS markers. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008;17:167–171. doi: 10.1007/BF03263279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choudhary S, Sethy NK, Shokeen B, Bhatia S. Development of sequence-tagged microsatellite site markers for chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:93–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sefera T, Abebie B, Gaur PM, Assefa K, Varshney RK. Characterisation and genetic diversity analysis of selected chickpea cultivars of nine countries using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Crop Pasture Sci. 2011;62:177–187. doi: 10.1071/CP10165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fayaz H, et al. Assessment of molecular genetic diversity of 384 chickpea genotypes and development of core set of 192 genotypes for chickpea improvement programs. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022;69:1193–1205. doi: 10.1007/s10722-021-01296-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keneni G, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of Ethiopian chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) germplasm accessions from different geographical origins as revealed by microsatellite markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;30:654–665. doi: 10.1007/s11105-011-0374-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mohan S, Kalaimagal T. Genetic diversity studies in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes using SSR markers. J. Food Legum. 2020;33:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Upadhyaya HD, et al. Genetic structure, diversity, and allelic richness in composite collection and reference set in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hajibarat Z, Saidi A, Hajibarat Z, Talebi R. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of landrace and improved chickpea (Cicer arietinum) genotypes using morphological and microsatellite markers. Environ. Exp. Biol. 2014;12:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farahani S, et al. Whole genome diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium analysis of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes using genome-wide DArTseq-based SNP markers. Genes. 2019;10:676. doi: 10.3390/genes10090676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suthar KP, et al. Genetic diversity assessment in chickpea genotypes using STMS. Legume Res. Int. J. 2012;35:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumar A, et al. Identification of highly polymorphic molecular markers and potential genotypes for harnessing chickpea breeding strategies. Legume Res. Int. J. 2022;45:804–814. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Seyedimoradi H, Talebi R, Kanouni H, Naji AM, Karami E. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) advanced breeding lines using whole-genome DArTseq-generated SilicoDArT markers. Braz. J. Bot. 2020;43:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s40415-020-00634-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980;32:314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meszaros K, et al. Efficiency of different marker systems for genotype fingerprinting and for genetic diversity studies in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007;73:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2006.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mir AH, et al. SSR markers in revealing extent of genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among chickpea core collection accessions for Western Himalayas. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022;49:11469–11479. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07858-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sari D, Sari H, Eker T, Ikten C, Uzun B, Toker C. Intraspecific versus interspecific crosses for superior progeny inCicer species. Crop Sci. 2022;2:2122–2137. doi: 10.1002/csc2.20765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid total DNA preparation procedure for fresh plant tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Girardot C, Scholtalbers J, Sauer S, Su S-Y, Furlong EE. Je, a versatile suite to handle multiplexed NGS libraries with unique molecular identifiers. BMC Bioinform. 2016;17:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kizil S, et al. Genome-wide discovery of InDel markers in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) using ddRADSeq. Plants. 2020;9:1262. doi: 10.3390/plants9101262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907 (2012).

- 90.Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Untergasser A, et al. Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W71–W74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schuelke M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:233–234. doi: 10.1038/72708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peakall ROD, Smouse PE. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perrier, X. & Jacquemoud-Collet J. P. DARwin Software, accessed 23 May 2023. http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin.

- 95.Sokal RR, Michener CD. A statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull. 1958;28:1409–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Park, S. D. E. Trypanotolerance in West African cattle and the population genetic effects of selection. Ph.D. Thesis University Dublin (2001).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence-Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number of PRJNA926661.