Abstract

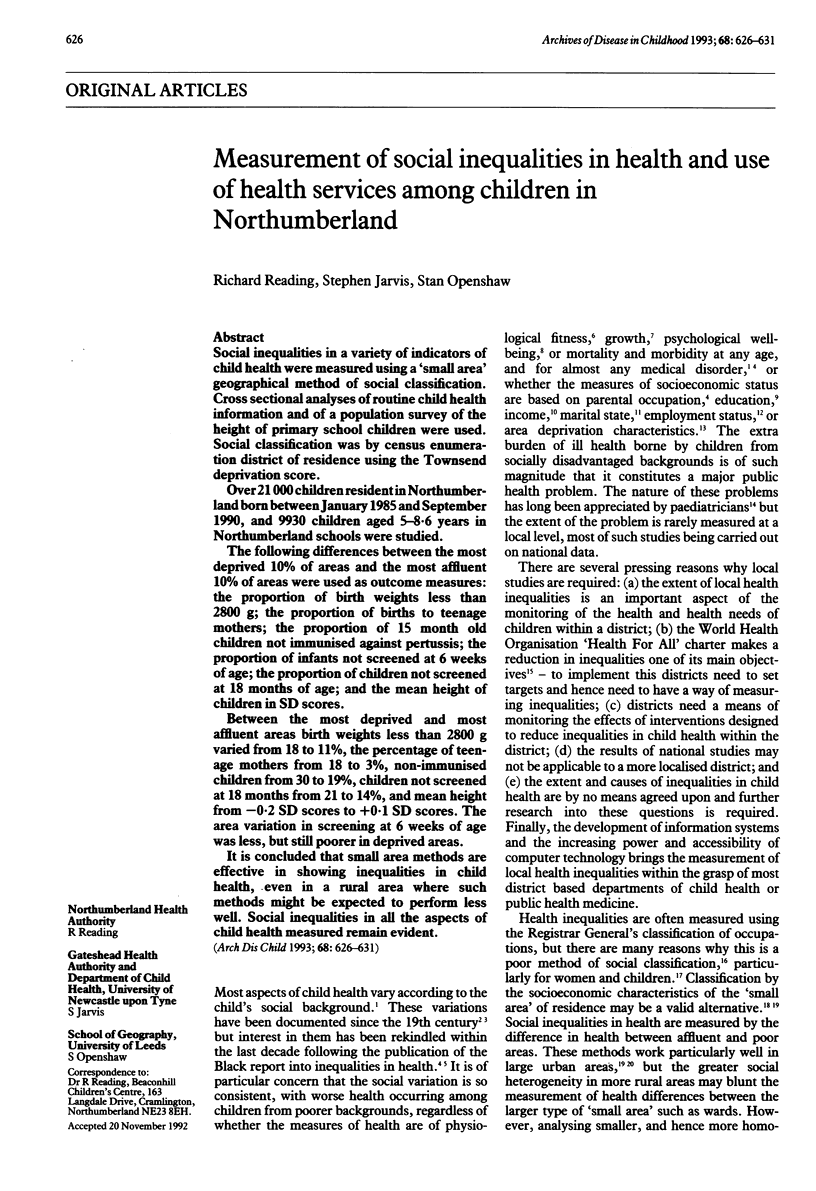

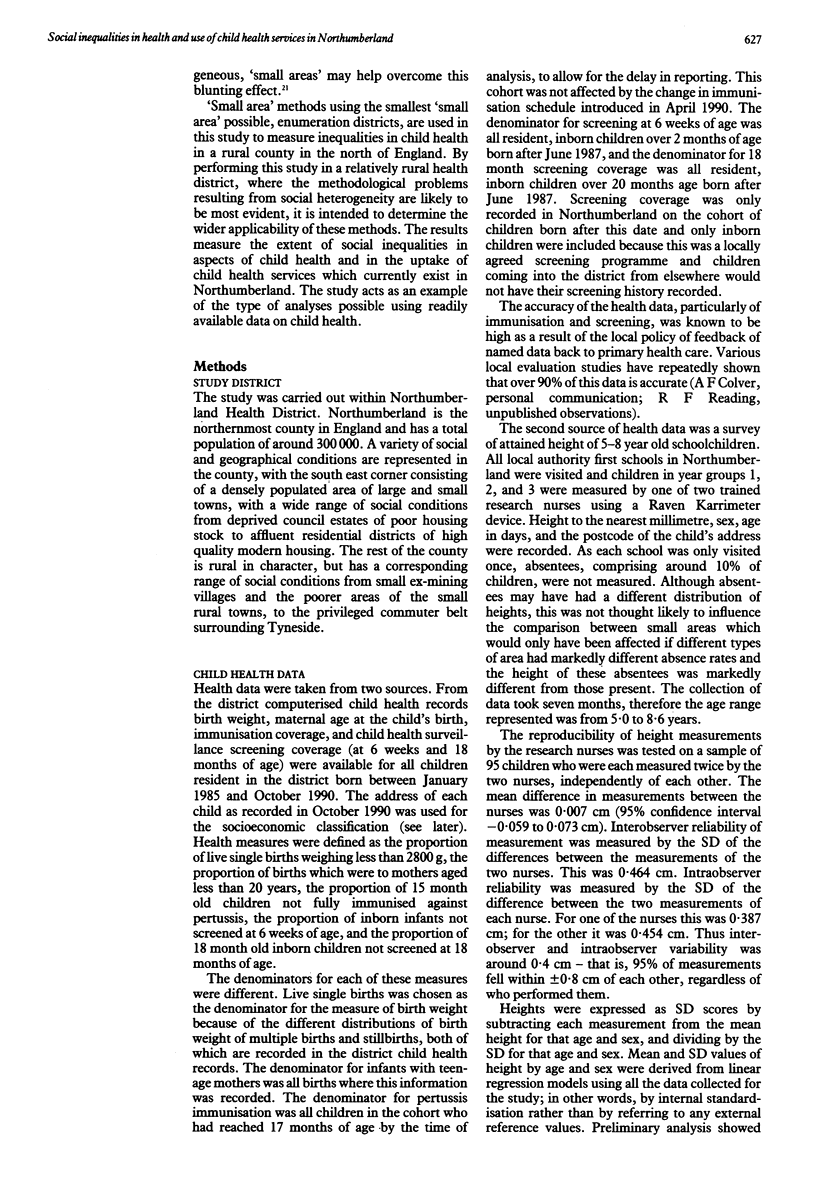

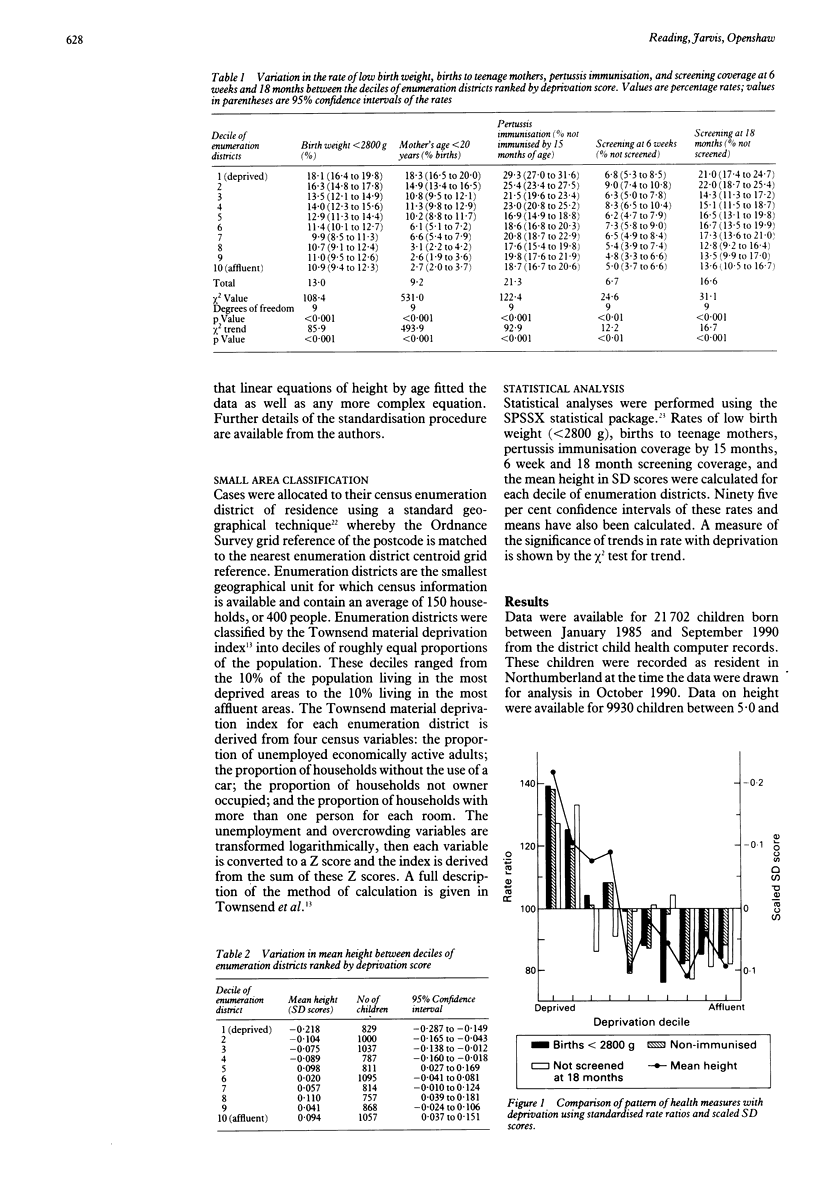

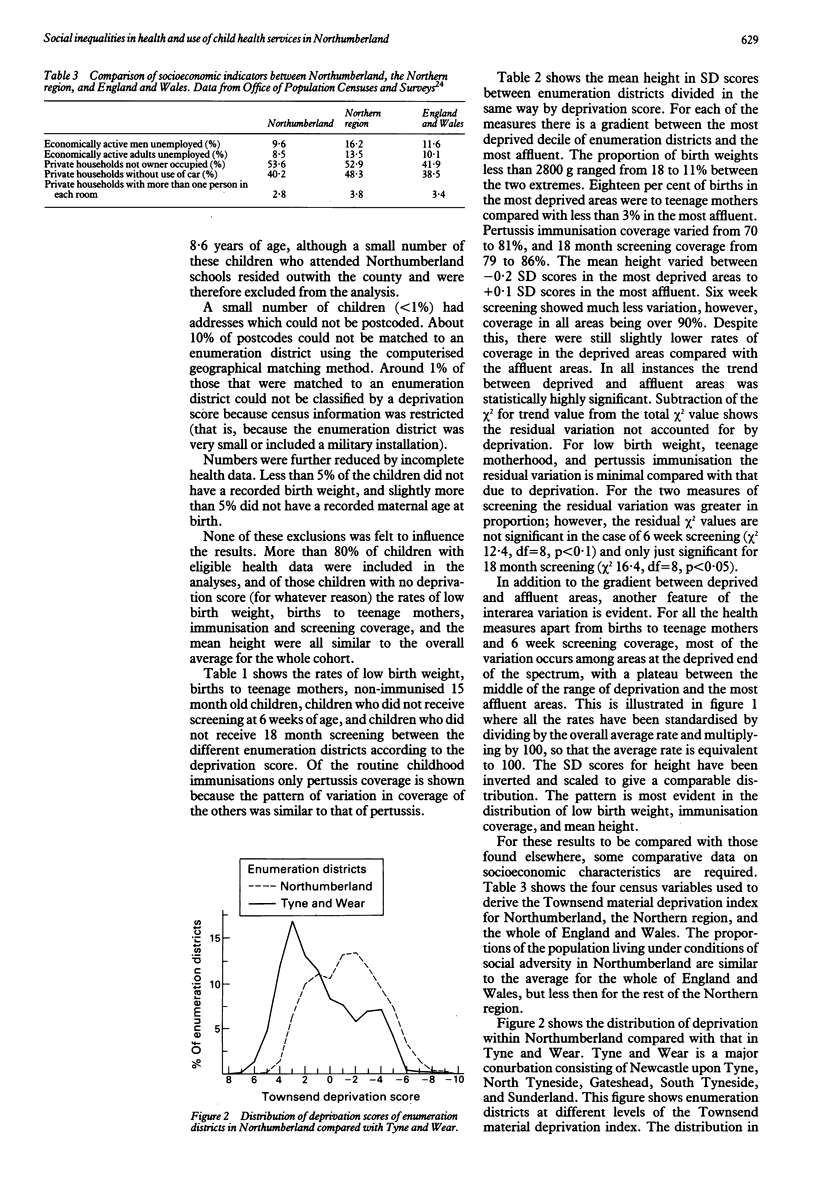

Social inequalities in a variety of indicators of child health were measured using a 'small area' geographical method of social classification. Cross sectional analyses of routine child health information and of a population survey of the height of primary school children were used. Social classification was by census enumeration district of residence using the Townsend deprivation score. Over 21,000 children resident in Northumberland born between January 1985 and September 1990, and 9930 children aged 5-8.6 years in Northumberland schools were studied. The following differences between the most deprived 10% of areas and the most affluent 10% of areas were used as outcome measures: the proportion of birth weights less than 2800 g; the proportion of births to teenage mothers; the proportion of 15 month old children not immunised against pertussis; the proportion of infants not screened at 6 weeks of age; the proportion of children not screened at 18 months of age; and the mean height of children in SD scores. Between the most deprived and most affluent areas birth weights less than 2800 g varied from 18 to 11%, the percentage of teenage mothers from 18 to 3%, non-immunised children from 30 to 19%, children not screened at 18 months from 21 to 14%, and mean height from -0.2 SD scores to +0.1 SD scores. The area variation in screening at 6 weeks of age was less, but still poorer in deprived areas. It is concluded that small area methods are effective in showing inequalities in child health, even in a rural area where such methods might be expected to perform less well. Social inequalities in all the aspects of child health measured remain evident.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Carstairs V., Morris R. Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ. 1989 Oct 7;299(6704):886–889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs V. Small area analysis and health service research. Community Med. 1981 May;3(2):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S., Price C. E., Rona R. J. Need for new reference curves for height. Arch Dis Child. 1989 Nov;64(11):1545–1553. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. M., Chinn S., Rona R. J. The relation of the height of primary school children to population density. Int J Epidemiol. 1983 Jun;12(2):199–204. doi: 10.1093/ije/12.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R. R. Postneonatal mortality among illegitimate children registered by one or both parents. BMJ. 1990 Jan 27;300(6719):236–237. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6719.236-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham P. J. Childhood epidemiology. Behavioural and intellectual development. Br Med Bull. 1986 Apr;42(2):155–162. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman B., Bosanquet N., Rice P., Dollimore N., Leese B. Uptake of immunisation in district health authorities in England. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Jun 25;296(6639):1775–1778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6639.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I. G., Cameron D. Social class analysis--an embarrassment to epidemiology. Community Med. 1984 Feb;6(1):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S. A review of the social patterning and significance of measures of height, weight, blood pressure and respiratory function. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(4):327–337. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Chinn S. ACORN group, social class, and child health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1983 Sep;37(3):196–203. doi: 10.1136/jech.37.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser K. A., Pugh H. S., Goldblatt P. O. Inequalities in women's health: looking at mortality differentials using an alternative approach. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Apr 30;296(6631):1221–1224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6631.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore P., Reading R. A rural advantage? Urban-rural health differences in northern England. J Public Health Med. 1992 Sep;14(3):290–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading R. F., Openshaw S., Jarvis S. N. Measuring child health inequalities using aggregations of Enumeration Districts. J Public Health Med. 1990;12(3-4):160–167. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rona R. J., Chinn S. The National Study of Health and Growth: nutritional surveillance of primary school children from 1972 to 1981 with special reference to unemployment and social class. Ann Hum Biol. 1984 Jan-Feb;11(1):17–27. doi: 10.1080/03014468400006851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- While A. Child health clinic attendance during the first two years of life. Public Health. 1990 Mar;104(2):141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(05)80365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]