Abstract

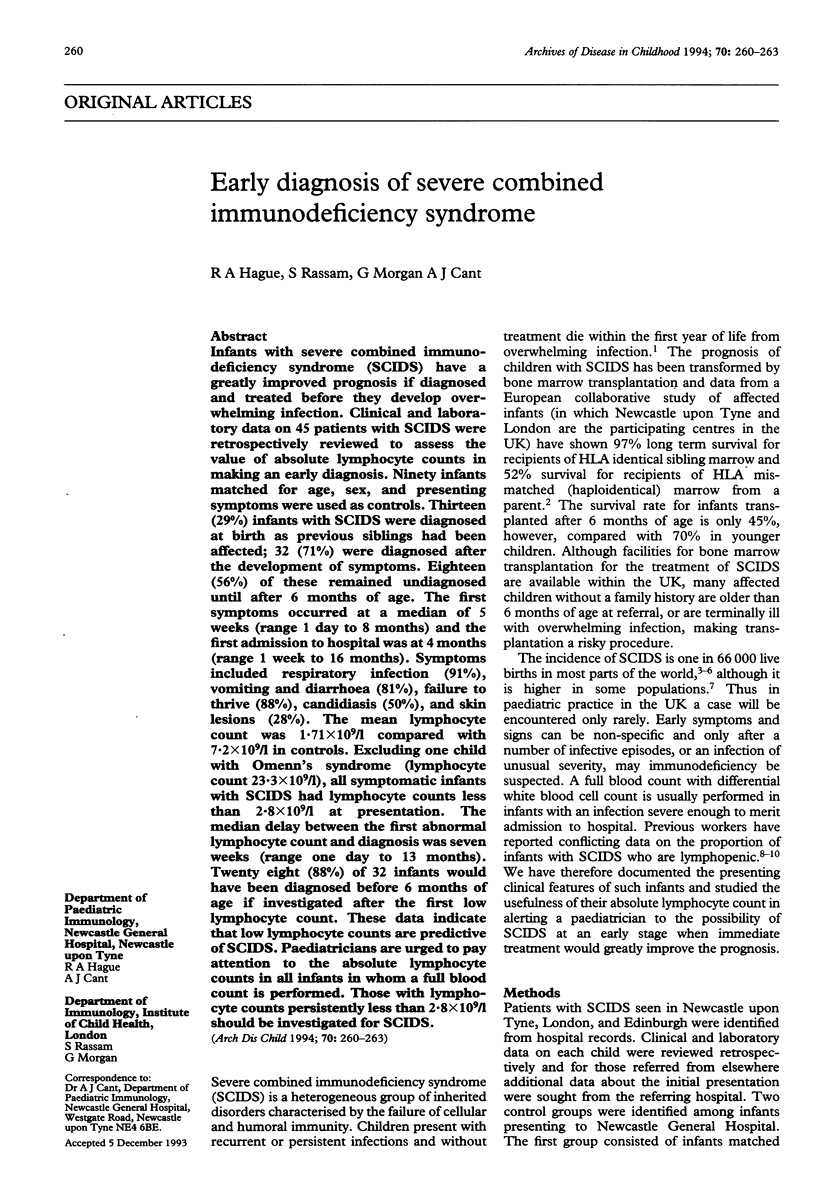

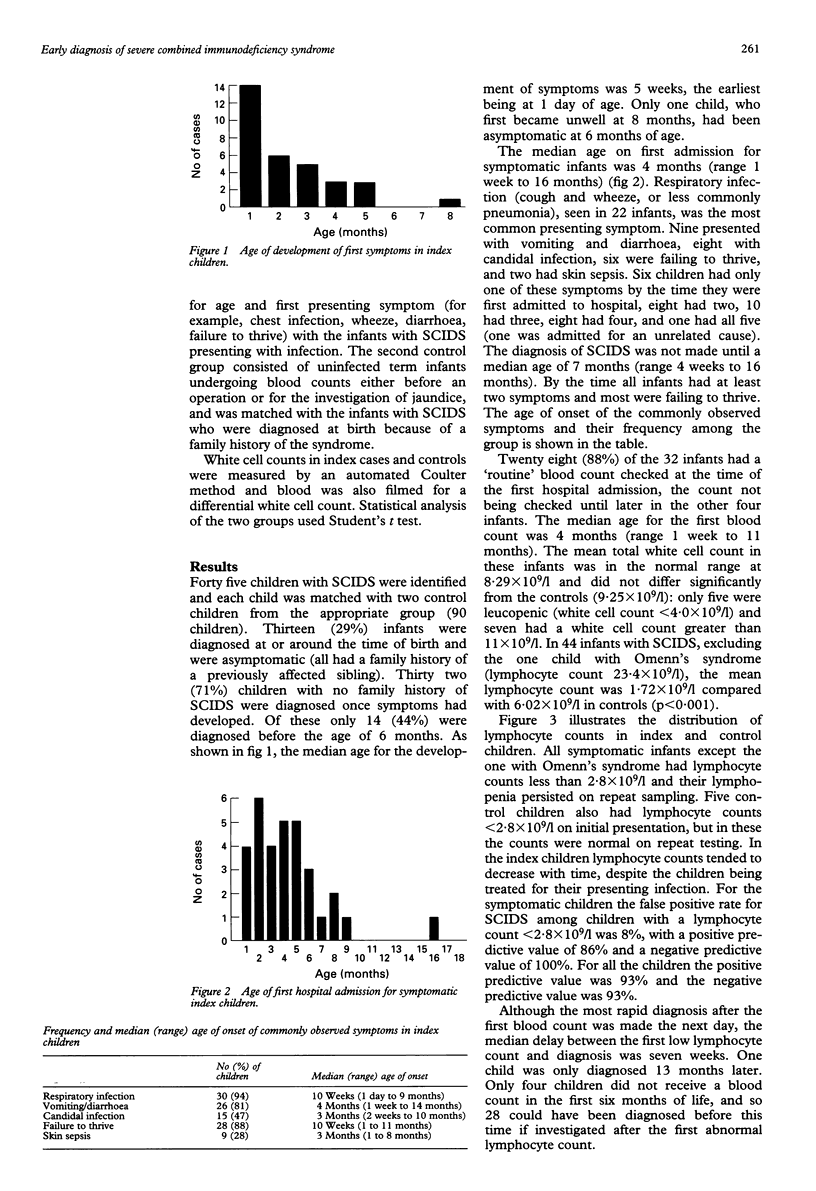

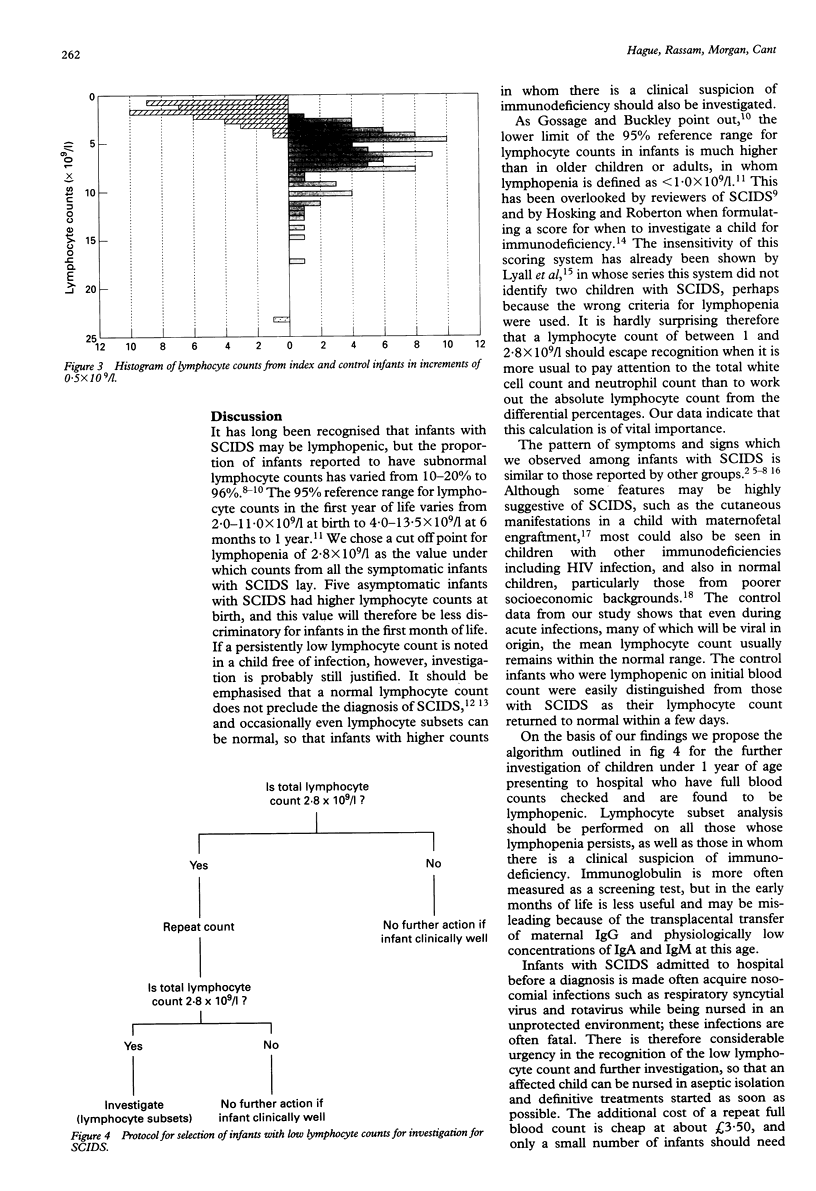

Infants with severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCIDS) have a greatly improved prognosis if diagnosed and treated before they develop overwhelming infection. Clinical and laboratory data on 45 patients with SCIDS were retrospectively reviewed to assess the value of absolute lymphocyte counts in making an early diagnosis. Ninety infants matched for age, sex, and presenting symptoms were used as controls. Thirteen (29%) infants with SCIDS were diagnosed at birth as previous siblings had been affected; 32 (71%) were diagnosed after the development of symptoms. Eighteen (56%) of these remained undiagnosed until after 6 months of age. The first symptoms occurred at a median of 5 weeks (range 1 day to 8 months) and the first admission to hospital was at 4 months (range 1 week to 16 months). Symptoms included respiratory infection (91%), vomiting and diarrhoea (81%), failure to thrive (88%), candidiasis (50%), and skin lesions (28%). The mean lymphocyte count was 1.71 x 10(9)/l compared with 7.2 x 10(9)/l in controls. Excluding one child with Omenn's syndrome (lymphocyte count 23.3 x 10(9)/l, all symptomatic infants with SCIDS had lymphocyte counts less than 2.8 x 10(9)/l at presentation. The median delay between the first abnormal lymphocyte count and diagnosis was seven weeks (range one day to 13 months). Twenty eight (88%) of 32 infants would have been diagnosed before 6 months of age if investigated after the first low lymphocyte count. These data indicate that low lymphocyte counts are predictive of SCIDS. Paediatricians are urged to pay attention to the absolute lymphocyte counts in all infants in whom a full blood count is performed. Those with lymphocyte counts persistently less than 2.8 x 10(9)l should be investigated for SCIDS.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bortin M. M., Rimm A. A. Severe combined immunodeficiency disease. Characterization of the disease and results of transplantation. JAMA. 1977 Aug 15;238(7):591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Raeve L., Song M., Levy J., Mascart-Lemone F. Cutaneous lesions as a clue to severe combined immunodeficiency. Pediatr Dermatol. 1992 Mar;9(1):49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1992.tb00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasth A. Primary immunodeficiency disorders in Sweden: cases among children, 1974-1979. J Clin Immunol. 1982 Apr;2(2):86–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00916891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Landais P., Friedrich W., Morgan G., Gerritsen B., Fasth A., Porta F., Griscelli C., Goldman S. F., Levinsky R. European experience of bone-marrow transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency. Lancet. 1990 Oct 6;336(8719):850–854. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92348-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontán G., García Rodriguez M. C., Carrasco S., Zabay J. M., de la Concha E. G. Severe combined immunodeficiency with T lymphocytes retaining functional activity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1988 Mar;46(3):432–441. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(88)90062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand E. W. SCID continues to point the way. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jun 14;322(24):1741–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006143222410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossage D. L., Buckley R. H. Prevalence of lymphocytopenia in severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 1990 Nov 15;323(20):1422–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011153232014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa H., Iwata T., Yata J., Kobayashi N. Primary immunodeficiency syndrome in Japan. I. Overview of a nationwide survey on primary immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 1981 Jan;1(1):31–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00915474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking C. S., Roberton D. M. Epidemiology and treatment of hypogammaglobulinemia. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1983;19(3):223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. F., Ritenbaugh C. K., Spence M. A., Hayward A. Severe combined immunodeficiency among the Navajo. I. Characterization of phenotypes, epidemiology, and population genetics. Hum Biol. 1991 Oct;63(5):669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall E. G., Eden O. B., Dixon R., Sutherland R., Thomson A. Assessment of a clinical scoring system for detection of immunodeficiency in children with recurrent infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991 Sep;10(9):673–676. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199109000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok J. Y., Hague R. A., Yap P. L., Hargreaves F. D., Inglis J. M., Whitelaw J. M., Steel C. M., Eden O. B., Rebus S., Peutherer J. F. Vertical transmission of HIV: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 1989 Aug;64(8):1140–1145. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.8.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. S., Hosking C. S. Severe combined immunodeficiency--the experience of the Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, 1969-1979. Aust Paediatr J. 1982 Sep;18(3):169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1982.tb02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter H. H., Friedrich W., Dopfer R., Müller W., Kortmann C., Pichler W. J., Heinz F., Rieger C. H. NK cell function in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID): evidence of a common T and NK cell defect in some but not all SCID patients. J Immunol. 1983 Nov;131(5):2332–2339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]