Abstract

Diatoms are a major phytoplankton group responsible for approximately 20% of carbon fixation on Earth. They perform photosynthesis using light-harvesting chlorophylls located in plastids, an organelle obtained through eukaryote-eukaryote endosymbiosis. Microbial rhodopsin, a photoreceptor distinct from chlorophyll-based photosystems, was recently identified in some diatoms. However, the physiological function of diatom rhodopsin remains unclear. Heterologous expression techniques were herein used to investigate the protein function and subcellular localization of diatom rhodopsin. We demonstrated that diatom rhodopsin acts as a light-driven proton pump and localizes primarily to the outermost membrane of four membrane-bound complex plastids. Using model simulations, we also examined the effects of pH changes inside the plastid due to rhodopsin-mediated proton transport on photosynthesis. The results obtained suggested the involvement of rhodopsin-mediated local pH changes in a photosynthetic CO2-concentrating mechanism in rhodopsin-possessing diatoms.

Keywords: microbial rhodopsins, diatom, marine microbiology, CO2-concentrating mechanism

Diatoms are unicellular, photosynthetic algae found throughout aquatic environments and are responsible for up to 20% of annual net global carbon fixation (Nelson et al., 1995; Field et al., 1998). Since their contribution to primary production in the ocean is significant, their light utilization mechanisms are essential to correctly understand marine ecosystems. Diatoms contain chlorophylls a and c and carotenoids, such as fucoxanthin, as photosynthetic pigments in the plastids acquired by eukaryote-eukaryote endosymbiosis (Keeling, 2004). Some diatoms have recently been shown to contain microbial rhodopsin (henceforth rhodopsins), a light-harvesting antenna distinct from the chlorophyll-containing antenna for photosynthesis (Marchetti et al., 2015). Although rhodopsin-mediated light-harvesting may support the survival of these diatoms in marine environments, the physiological role of rhodopsin in diatom cells remains unclear.

Microbial rhodopsins are a large family of seven transmembrane photoreceptor proteins (Spudich et al., 2000). Rhodopsin has an all-trans retinal as the light-absorbing chromophore, and its protein function is triggered by the light-induced isomerization of the retinal. The first microbial rhodopsin, the light-driven proton pump bacteriorhodopsin (BR), was discovered in halophilic archaea (Oesterhelt and Stoeckenius, 1971). Although rhodopsin was initially considered to only occur in halophilic archaea inhabiting hypersaline environments, subsequent studies showed that the rhodopsin gene is widely distributed in all three domains of life (Beja et al., 2000; Sineshchekov et al., 2002). Rhodopsins are classified based on their functions into light-driven ion pumps, light-activated signal transducers, and light-gated ion channels. The two former functional types of rhodopsin have so far been identified in prokaryotes (Ernst et al., 2014). Rhodopsins in prokaryotes, regardless of function, localize to the cell membrane in which they operate. For example, proton-pumping rhodopsins export protons from the cytosol across the cell membrane to convert light energy into a proton motive force (PMF) (Yoshizawa et al., 2012). The PMF induced by rhodopsin ion transport is utilized by various physiological functions, such as ATP synthesis, substrate uptake, and flagellar movement.

Rhodopsins functioning as light-driven ion pumps and light-gated ion channels have been reported in eukaryotic microorganisms (Ernst et al., 2014; Kikuchi et al., 2021). A light-gated ion channel called channelrhodopsin, which localizes to the plasma membrane over the eyespot within the chloroplast of green algae, has been extensively examined for its role in phototaxis (Nagel et al., 2002). The other type of rhodopsin in eukaryotes, light-driven ion-pumping rhodopsins has been detected in a number of organisms belonging to both photoautotrophic and heterotrophic protists (Slamovits et al., 2011; Marchetti et al., 2015). Since the intracellular membrane structure of eukaryotic cells is more complex than that of prokaryotes, containing various organelles, even light-driven ion-pumping rhodopsins may have distinct physiological roles depending on their subcellular localization (Slamovits et al., 2011). However, due to the difficulties associated with identifying the exact localization of rhodopsins in eukaryotic cells, their subcellular localization remains unknown.

In the present study, to clarify the physiological function of rhodopsin in a marine pennate diatom, we investigated the phylogeny, protein function, spectroscopic characteristics, and subcellular localization of rhodopsin from a member of the genus Pseudo-nitzschia. Heterologous expression techniques were used to analyze protein functions and spectroscopic features. The expression of rhodopsin fused with a green fluorescent protein, eGFP revealed its subcellular localization in a model diatom (Phaeodactylum tricornutum). Furthermore, a model-based analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of the potential roles of rhodopsin in cellular biology.

Materials and Methods

Rhodopsin sequences and phylogenetic analysis

The rhodopsin sequence of the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia granii was previously reported (Marchetti et al., 2015). All other rhodopsin sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis were collected from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Detailed information on the strains used in this analysis is given in Extended Data Fig. 1. Sequences were aligned using MAFFT version 7.453 with the options ‘—genafpair’ and ‘—maxiterate 1000’ (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The phylogenetic tree was inferred using RAxML (v.8.2.12) with the ‘PROTGAMMALGF’ model using 1,000 rapid bootstrap searches (Stamatakis, 2014). Model selection was performed with the ProteinModelSelection.pl script in the RAxML package.

The search for eukaryotic rhodopsins belonging to the Xanthorhodopsin (XR)-like rhodopsin (XLR) clade was performed among the protein sequences of the Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP) (Keeling et al., 2014). The phylogenetic placement of rhodopsin proteins from MMETSP using pplacer (v1.1.alpha19) (Matsen et al., 2010) was conducted on a prebuilt large-scale phylogenetic tree of rhodopsins and extracted placements on the XLR clade using gappa (v0.6.0) (Czech et al., 2020).

Gene preparation, protein expression, and ion transport measurements of Escherichia coli cells

In the present study, a functional analysis of the rhodopsin possessed by the diatom P. granii (named PngR, accession no. AJA37445.1) was performed using a heterologous expression system. The full-length cDNA for PngR, the codons of which were optimized for E. coli, were chemically synthesized by Eurofins Genomics and inserted into the NdeI-XhoI site of the pET21a(+) vector as previously described (Hasegawa et al., 2020). A hexa-histidine-tag was fused at the C terminus of PngR, which was utilized for the purification of the expressed protein. The heterologous protein expression method is the same as that previously reported (Inoue et al., 2018). E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring the cognate plasmid were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (final concentration of 50 μg mL–1). Protein expression was induced at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7–1.2 with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 10 μM all-trans retinal, after which cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The proton transport activity of PngR was measured as light-induced pH changes in suspensions of E. coli cells as previously described (Inoue et al., 2018). Briefly, cells expressing PngR were washed more than three times in 150 mM NaCl and then resuspended in the same solution for measurements. Each cell suspension was placed in the dark for several min and then illuminated using a 300 W Xenon lamp (ca. 30 mW cm–2, MAX-303; Asahi Spectra) through a >460 nm long-pass filter (Y48; HOYA) for 3 min. Measurements were repeated under the same conditions after the addition of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (final concentration=10 μM). Light-induced pH changes were monitored using a Horiba F-72 pH meter. All measurements were conducted at 25°C using a thermostat (Eyela NCB-1200; Tokyo Rikakikai).

Purification of PngR from E. coli cells and spectroscopic measurements of the purified protein

E. coli cells expressing PngR were disrupted by sonication for 30 min in ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0) and 300 mM NaCl. The crude membrane fraction was collected by ultracentrifugation (130,000×g at 4°C for 60 min) and solubilized with 1.0% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM; DOJINDO Laboratories). The solubilized fraction was purified by Ni2+ affinity column chromatography with a linear gradient of imidazole as previously described (Kojima et al., 2020b). The purified protein was concentrated by centrifugation using an Amicon Ultra filter (30,000 Mw cut-off; Millipore). The sample medium was then replaced with Buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, and 0.05% [w/v] DDM) by ultrafiltration 3 times.

The absorption spectra of purified proteins were recorded using a UV-2450 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) at room temperature in Buffer A. The retinal composition in PngR was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (Kojima et al., 2020a). Regarding dark adaptation, samples were kept under dark conditions at 4°C for more than 72 h, whereas those for light adaptation were illuminated for 3 min at 520±10 nm, with light power being adjusted to approximately 10 mW cm–2. The molar compositions of the retinal isomers were calculated from the areas of the peaks in HPLC patterns monitored at 360 nm using the extinction coefficients of retinal oxime isomers as previously described (Kojima et al., 2020a). In pH titration experiments, samples were suspended in Buffer A. The pH values of the samples were adjusted to the desired acidic values by the addition of HCl, after which absorption spectra were measured at each pH value. All measurements were conducted at room temperature (approximately 25°C) under room light. After these measurements, the reversibility of spectral changes was examined to confirm that the sample was not denatured during measurements. Absorption changes at specific wavelengths were plotted against pH values and plots were fit to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation assuming a single pKa value as previously described (Inoue et al., 2018).

The transient time-resolved absorption spectra of the purified proteins from 380 to 700 nm at 5-nm intervals were obtained using a homemade computer-controlled flash photolysis system equipped with an Nd: YAG laser as an actinic light source. Using an optical parametric oscillator, the wavelength of the actinic pulse was tuned at 510 nm for PngR. Pulse intensity was adjusted to 2 mJ per pulse. All data were averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (n=30). All measurements were conducted at 25°C. In these experiments, samples were suspended in Buffer A. After measurements, the reproducibility of data was checked to confirm that the sample was not denatured during measurements. To investigate proton uptake and release during the photocycle, we used the pH indicator pyranine (final concentration=100 μM; Tokyo Chemical Industry), which has been extensively used to monitor light-induced pH changes in various rhodopsins. pH changes in the bulk environment were measured as the absorption changes of pyranine at 450 nm. The absorption changes of pyranine were obtained by subtracting the absorption changes of samples without pyranine from those of samples with pyranine. Experiments using pyranine were performed in an unbuffered solution containing 1 M NaCl and 0.05% (w/v) DDM (pH 7.0) to enhance signals. The results of 1,000 traces were averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Subcellular localization of PngR in the model diatom

The PngR:eGFP recombinant gene, coding the full length of PngR C-terminally tagged with eGFP, was cloned into the expression vector for the model diatom P. tricornutum, pPha-NR (Stork et al., 2012), by CloneEZ (GenScript) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid was electroporated into cells of P. tricornutum UTEX642 with the NEPA21 Super Electroporator (NEPAGENE), and transformed cells were selected with a Zeocin-based antibiotic treatment as previously described (Miyahara et al., 2013; Dorrell et al., 2019). Selected clones were observed under an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope (Olympus) equipped with an Olympus DP72 CCD color camera (Olympus). The nucleus stained with DAPI and chlorophyll autofluorescence from the plastid were observed with a 420-nm filter at 330 to 385 nm excitation. GFP fluorescence was detected with a 510- to 550-nm filter at 470 to 495 nm excitation.

Quantitative model of C concentrations in a diatom: Cell Flux Model of C Concentration (CFM-CC)

Membrane transport model. We combined the membrane transport of CO2 and C fixation. Parameter definitions, units, and values are provided in Supporting Information Table S1 and S2, respectively. The key model equation is the balance of the concentration of CO2 in the cytosol, [CO2]p:

where t is time, D is the diffusion coefficient, and [CO2]m is the concentration of CO2 in the inner side of the outermost membrane of the plastid (hereafter “the middle space”). The first term represents the diffusion of CO2 from the middle space to the cytosol, while the second term VCfix represents the C fixation rate following Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Berg et al., 2010; Hopkinson, 2014):

where Vmax is the maximum CO2 fixation rate and K is the half saturation constant. [CO2]m is obtained based on the carbonate chemistry in the middle space (see below). Under the steady state, [eq. 1] with [eq. 2] becomes the following quadratic relationship for [CO2]p:

Solving this equation for leads to:

Note that the other solution for the negative route is unrealistic because it may lead to the overall negative value of [CO2]p. Once we obtain [CO2]p, we may then calculate the rate of C fixation VCfix with [eq. 2].

Furthermore, from [eq. 4], we obtain two extreme solutions. In the case of Vmax≪D (i.e., when the CO2 uptake capacity is small relative to the speed of CO2 diffusion), [eq. 4] leads to

With this relationship and [eq. 2], VCfix is computed as follows:

In contrast, when Vmax≫D (i.e., when the CO2 uptake capacity is high relative to the CO2 diffusion across the membrane), [eq. 4] becomes

Under the steady state, [eq. 1] becomes

and plugging [eq. 7] into [eq. 8] leads to

and VCfix is calculated. We note that [CO2]p>[CO2]m may occur when there are membrane-bound transporters for HCO3– located on each membrane between the middle space and plastid (Hopkinson, 2014). However, such a set of transporters has not yet been discovered (Matsuda et al., 2017). Therefore, our model conforms with the current state of knowledge. Even if [CO2]p>[CO2]m, moderately decreased pHm and, thus, increased [CO2]m may be useful since they may reduce the gradient of CO2 across membranes (i.e., [CO2]p vs [CO2]m), thereby mitigating the diffusive loss of CO2 from the plastid.

Carbonate chemistry in the middle space. The above equations may be solved once we obtain [CO2]m. The model uses a given DIC (dissolved inorganic C) concentration in the middle space [DIC]m to calculate [CO2]m following the established equations for carbon chemistry (Emerson and Hedges, 2008).

where [H+]m is the concentration of H+ (10–pH mol L–1) in the middle space and K1 and K2 are temperature- and salinity-dependent parameters (Lueker et al., 2000; Emerson and Hedges, 2008):

where

Code availability

The code for CFM-CC is freely available from GitHub/Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/record/5182712 (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5182712).

Results and Discussion

Rhodopsin sequences and phylogenetic analysis

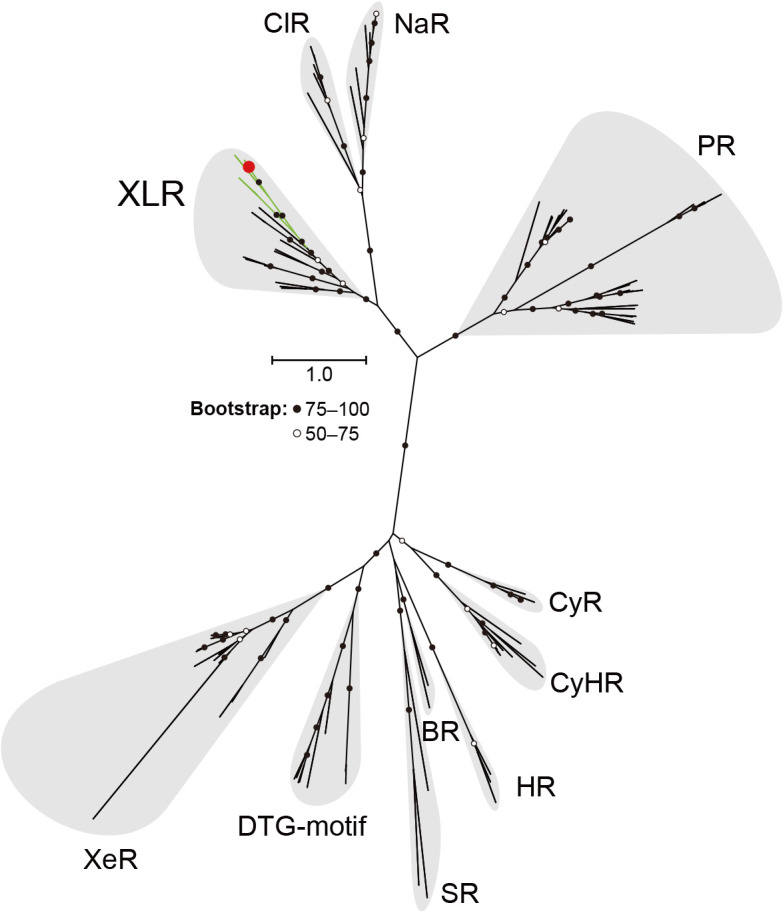

We performed a phylogenetic analysis using the rhodopsin (named PngR, accession no. AJA37445.1) of the diatom P. granii and microbial rhodopsin sequences reported to date (Marchetti et al., 2015). This phylogenetic tree revealed that PngR is not included in the proteorhodopsin (PR) clade commonly found in oceanic organisms, but belongs to the Xanthorhodopsin (XR)-like rhodopsin (XLR) clade, which is presumed to have an outward proton transporting function (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1). A comparison of the motif sequences necessary for ion transport showed that the amino acids in the putative proton donor and acceptor sites of XR and PR were conserved in PngR, suggesting that PngR functions as an outward proton pump (Extended Data Fig. 2). Furthermore, the homology search for rhodopsin sequences in the XLR clade from Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP) revealed that not only diatoms (Ochrophyta, Stramenopiles), but also dinoflagellates (Dinophyceae, Alveolata) and haptophytes have rhodopsin genes in the same XLR clade (Supporting Information Table S3). These results indicate that rhodopsins of the XLR clade are widely distributed among the major phytoplankton groups, which are important primary producers in the ocean.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic position of diatom rhodopsin. A maximum likelihood tree of the amino acid sequences of microbial rhodopsins. Diatom rhodopsin (PngR) is indicated by a red circle and bootstrap probabilities (≥50%) by black and white circles. Green branches indicate eukaryotic rhodopsins used in this analysis, while black branches indicate others. Rhodopsin clades are as follows: Xanthorhodopsin-like rhodopsin (XLR), Cl–-pumping rhodopsin (ClR), Na+-pumping rhodopsin (NaR), proteorhodopsin (PR), xenorhodopsin (XeR), DTG-motif rhodopsin, sensory rhodopsin-I and sensory rhodopsin-II (SR), bacteriorhodopsin (BR), halorhodopsin (HR), cyanobacterial halorhodopsin (CyHR), and cyanorhodopsin (CyR).

Function and spectroscopic features of diatom rhodopsin

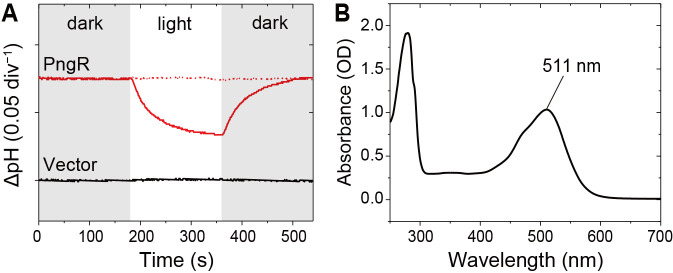

To characterize the function of PngR, we heterologously expressed the synthesized rhodopsin gene in E. coli cells. A light-induced decrease in pH was observed in the suspension of E. coli cells expressing PngR, and this reduction was almost completely abolished in the presence of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Fig. 2A). The pH changes observed clearly showed that PngR exported protons from the cytoplasmic side across the cell membrane.

Fig. 2.

Light-induced pH changes and absorption spectrum of PngR. (A) Outward proton pump activity of PngR in E. coli cells. Light-induced pH changes in solutions containing E. coli cells with the expression plasmid for PngR (upper panel) and the empty vector pET21a (lower panel) in the presence (red dashed line) or absence (red solid line) of CCCP. The white-filled region indicates the period of illumination. (B) Absorption spectrum of purified PngR in Buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, and 0.05% [w/v] DDM).

We then examined the spectroscopic characteristics of PngR using the recombinant protein purified from E. coli. The absorption maximum of PngR was located at 511 nm (Fig. 2B), which was markedly shorter than those of XR (565 nm) and GR (Gloeobacter rhodopsin 541 nm) in the XLR clade (Balashov et al., 2005). It is important to note that while P. granii is a marine species, XR and GR are both distributed in terrestrial organisms. Therefore, the present results are consistent with the shorter wavelength of the absorption maximum of rhodopsin in marine environments than in the terrestrial environment (Man et al., 2003), indicating that PngR is well adapted to light conditions in the ocean, particularly the open ocean.

We then examined the retinal configuration in PngR by HPLC. In light- and dark-adapted samples, the isomeric state of retinal was predominantly all-trans (Extended Data Fig. 3), which was similar to the isomeric state of retinal in prokaryotic GR in the XLR clade, but different from that in BR (Miranda et al., 2009). Since the pKa value of the proton acceptor residue (Asp85 in BR) is an indicator of the efficiency of proton transport by rhodopsin, we estimated the pKa values of the putative proton acceptor in PngR (Asp91) by a pH titration experiment (Extended Data Fig. 4). This experiment estimated that the pKa of this residue acceptor was approximately 5.0, indicating that the proton acceptor of PngR works well in marine and intracellular environments. Furthermore, the photochemical reactions that proceed behind the ion-transportation mechanism of PngR were examined by a flash photolysis analysis (Extended Data Fig. 5). All photocycles required for ion transportation in PngR were completed in approximately 300 ms, suggesting that the cycle was sufficiently fast to pump protons in a physiologically significant time scale. The results and a discussion of the flash photolysis analysis are described in the supplementary information.

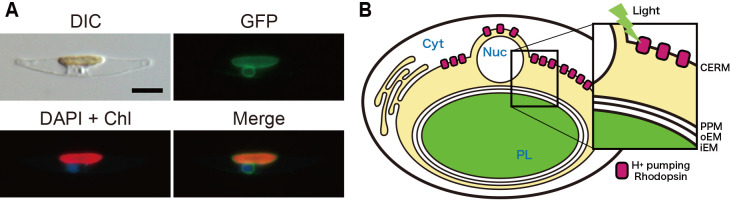

Subcellular localization of PngR in a model diatom

The PngR sequence bears neither an apparent N-terminal extension nor a detectable N-terminal signal peptide, and, thus, in silico analyses are unable to predict the subcellular localization of PngR. To identify the subcellular localization of PngR, a C-terminal eGFP-fusion PngR was expressed in the model diatom P. tricornutum, which may be transformed by electroporation and is often used in a heterologous expression analysis (Nakajima et al., 2013; Dorrell et al., 2019). The transformed P. tricornutum cell was examined under differential interface contrast and epifluorescent microscopes (Fig. 3A). We observed the fluorescence of GFP, DAPI, and chlorophylls to establish the localization of recombinant PngR:eGFP, the nucleus, and chloroplast, respectively, in multiple cells (Extended Data Fig. 6 and 7). The fluorescence signal of the PngR:eGFP transformant appeared to localize at the periphery of chlorophyll fluorescence and DAPI signals, corresponding to the outermost plastid membrane, called the chloroplast endoplasmic reticulum membrane (CERM), which is physically connected to the nuclear membrane (Fig. 3A). A few cells also exhibited GFP signals within vacuolar membranes in addition to CERM (Extended Data Fig. 7). The insertion of the complete sequence of the PngR:eGFP gene in transformant DNA was confirmed by PCR followed by Sanger sequencing.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of rhodopsins in diatom cells. (A) A transformed diatom cell was observed with differential interface contrast (DIC) (Upper left). Green fluorescence from recombinant PngR (GFP) (Upper right). Nuclear DNA stained with DAPI and chlorophyll autofluorescence (DAPI + Chl) and a merged image (Merge) are shown in the bottom left and bottom right, respectively. The scale bar indicates 5 μm. (B) A mode for the subcellular localization of PngR. The proton transport of PngR acidifies or alkalizes the region (the middle space) surrounded by the membrane of CERM and PPM. Abbreviations are as follows: cytosol (Cyt), nucleus (Nuc), plastid (PL), chloroplast endoplasmic reticulum membrane (CERM), periplastidial membrane (PPM), outer plastid envelope membrane (oEM), and internal plastid envelope membrane (iEM).

Based on the results of the heterologous expression experiment and microscopic observations, we concluded that PngRs primarily localized to the outermost membrane of the plastid. However, fluorescence signals were also observed to a lesser extent in the vacuolar membrane, suggesting the involvement of other factors, such as cell growth conditions, in their localization. These results imply that light-driven proton transport by PngR acidifies or alkalizes the inner region of CERM (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the physiological role of pH changes in this region in diatoms warrants further study. The electrochemical gradient formed by rhodopsin may be a driving force for various secondary transport processes. Alternatively, based on the primary purpose of plastids, local pH changes may be related to photosynthesis. The pH in this region is considered to be important for the transport of inorganic carbon (Ci) to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) (Gee and Niyogi, 2017). This is because in the carbonate system, pH affects the proportion of carbonate species (CO2, HCO3–, and CO32–) in water.

Under weakly alkaline conditions in the ocean, the majority of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) is generally present in the form of HCO3–, with only approximately 1% being present in the form of CO2. However, RuBisCO localized in the stroma only reacts with Ci in the form of CO2, not HCO3–. The RuBisCO enzyme in diatoms exhibits low affinity even for CO2 (Km of 25~68 μM, while CO2aq in the ocean is approximately 10 μM at 25°C) and, thus, requires concentrated CO2 for efficient fixation at the site of RuBisCO. In other words, the ocean is always a CO2-limited environment for most phytoplankton (Riebesell et al., 1993). Consequently, due to the membrane impermeability of HCO3–, phytoplankton have developed a number of CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCM) to efficiently transport Ci to the site of RuBisCO by placing HCO3– transporters in appropriate membranes and carbonic anhydrase (CA) in these compartments, the latter of which catalyzes the rapid interconversion between HCO3– and CO2. However, since difficulties are associated with directly examining pH changes and the forms of Ci of the small compartment in eukaryotic microbial organelles, a model simulation is a powerful alternative approach (Hopkinson et al., 2011). In the present study, we used a model simulation to investigate whether rhodopsin-mediated pH changes in this region were involved in CCM.

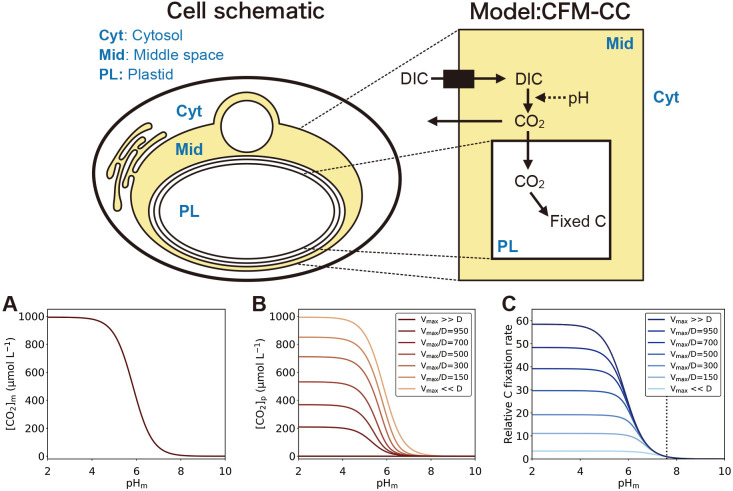

A quantitative model of carbon concentrations in diatoms: CFM-CC

Our subcellular localization analysis suggested that proton transport by rhodopsin acidified or alkalized the inner side of the outermost membrane of the plastid (the middle space). To quantitatively examine the effects of pH in the middle space on C fixation, we developed a simple quantitative model of carbonate chemistry combined with membrane transport and C fixation (CFM-CC: Cell Flux Model of C Concentration) (Fig. 4 upper panel). A comprehensive model of the concentration of CO2 within diatoms was developed (Hopkinson et al., 2011; Hopkinson, 2014). CFM-CC uses a conceptually similar structure to this model, focusing on more specific membrane layers, designed to test the effects of pH changes in the middle space.

Fig. 4.

A quantitative model of the concentration of carbon in diatoms. (Upper panel) Schematic of a Cell Flux Model of C Concentration (CFM-CC). The left panel represents the actual cell, while the right panel represents the model. Solid arrows show the net flux of C and the dashed arrow indicates the effects of pH. (Bottom panel) The effects of pH in the middle space on CO2 concentrations and the photosynthesis rate. (A) CO2 concentrations in the middle space [CO2]m. (B) CO2 concentrations in the plastid [CO2]p. (C) The C fixation rate relative to that with pH in the middle space of 7.59, the only mean value we found for intracellular pH in a diatom (Burns and Beardall, 1987). (B) and (C) are plotted for various Vmax/D. The solution for [CO2]m in (A) is independent of Vmax/D.

Our model results showed that the concentrations of CO2 in the middle space ([CO2]m) were strongly dependent on pH (pHm), suggesting that proton pumping by rhodopsin affected C fixation (Fig. 4 bottom panel). The calculation of C chemistry in the middle space revealed that a decrease in pHm favored higher [CO2]m at a given DIC concentration (Fig. 4A) (we used 993 μmol L–1 [Burns and Beardall, 1987]). We noted that the potential leaking of CO2 into the cytosol may change DIC in the middle space, but used a constant DIC value because this effect has not been experimentally demonstrated and is difficult to quantify due to unknown factors (e.g., the balance of DIC uptake and CO2 leaking). At the reference point (we used pHm=7.59 [Burns and Beardall, 1987]), [CO2]m was 17 μmol L–1, but increased to 64, 410, and 870 μmol L–1 for pHm values of 7, 6, and 5, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Due to increased [CO2]m, the concentration of CO2 in the plastid ([CO2]p) also increased with lower pHm; however, the level of this increase was dependent on Vmax/D (the ratio of the maximum C fixation rate to the diffusion constant) (Fig. 4B). When Vmax/D was small, the diffusion of CO2 from the middle space to the plastid dominated the change, resulting in [CO2]p similar to [CO2]m. In contrast, when Vmax/D was large, CO2 uptake dominated, and the effect of [CO2]m on [CO2]p was small.

The rate of C fixation increased with lower pHm because increased [CO2]m accelerated the transport of CO2 into the plastid (Fig. 4C). However, the magnitude of this increase depended on Vmax/D. The model showed that the effects of pHm on C fixation were greater when Vmax/D was large because the rate of C fixation was changed more by [CO2]m [eq. 6], which is directly affected by pHm. However, when Vmax/D was small, the C fixation rate was changed more by C uptake kinetics [eq. 4], which were saturated at a relatively low [CO2]p (K value of 44 μmol L–1 [Jensen et al., 2020]). Based on the possible range of Vmax/D, C fixation showed 2.1- to 3.8-, 3.2- to 24.2-, and 3.4- to 51.2-fold increases when pHm decreased from 7.59 to 7, 6, 5 respectively. These results suggested that pHm markedly affected C uptake at any Vmax/D as well as also the benefit for cells to have high Vmax relative to the diffusivity of CO2 across the membrane. This was most likely the case because the D value was shown to be reduced when there were multiple membranes (Eichner et al., 2019; Inomura et al., 2019). Therefore, this simple yet elegant system with rhodopsin to manipulate pHm provides a powerful mechanism in C concentrations and, thus, adjusts the C fixation rate to given physiological conditions in some rhodopsin-containing diatoms, enabling them to be more successful primary producers in the ocean.

In our model simulation, we examined the effects of rhodopsin-mediated pH changes in the middle space on CCM efficiency. The results obtained suggested that C fixation was enhanced when the pH of the middle space was acidified by a light-driven proton pump. CCM based on CO2 diffusion (termed the pump-leak type) has been proposed as a possible mechanism by placing CAs in appropriate locations. For example, Nannochloropsis oceanica (Ochrophyta), possessing the same four membrane-bound complex plastids as those found in diatoms, is considered to generate CO2 by placing CA in the middle space (Gee and Niyogi, 2017). Furthermore, the centric diatom Chaetoceros gracilis is considered to generate CO2 by placing CAs outside the cell and allowing CO2 to flow into the cell (Tsuji et al., 2021). In contrast to the CA-based model, the acidification-based model was formerly proposed to facilitate the CO2 fixation of RuBisCO in the thylakoid lumen of plastids; HCO3– is converted into CO2 through acidification by photosynthetic proton pumping into the thylakoid lumen (Raven, 1997). Our rhodopsin-mediated Ci transform model, CFM-CC proposes that pH changes in the middle space by proton-pumping rhodopsin also plays the role of a CO2 regulator. This proposed mechanism may be useful in most parts of the ocean where CO2 chronically limits photosynthesis, but may be even more valuable in specific environments. For example, since CA, which plays a central role in CCM, requires cobalt or zinc ions as the reaction center, and photosynthetic proton-pumping systems need iron, rhodopsin-derived acidic pools may be useful for Ci uptake in oceans where these metal ions are depleted (such as the HNLC region of the North Pacific Ocean) (Moore et al., 2013). In the HNLC region of the North Pacific, where P. granii rhodopsin-containing cells were initially identified (Marchetti et al., 2012), primary production may be limited by iron and affected by other trace metals (Saito et al., 2008). In other words, our proposed mechanism appears to be particularly effective in the ocean where trace metals involved in CCM are depleted.

In the present study, we clarified the function and subcellular localization of PngR in a photosynthetic diatom. The results obtained suggest that proton transport by rhodopsin changes pH inside the outermost membrane of the plastid (CERM). A quantitative simulation indicated that the creation of an acidic pool by light provides positive feedback on C fixation efficiency, while alkalization of the middle space may restrict C fixation. If PngR acidifies the middle space, diatom rhodopsin may contribute to CCM (Extended Data Fig. 8). Future analyses of cultured rhodopsin-bearing microbial eukaryotes will corroborate the present results and promote further research on the mechanisms by which rhodopsin-mediated proton transport promotes their growth in the ocean.

Citation

Yoshizawa, S., Azuma, T., Kojima, K., Inomura, K., Hasegawa, M., Nishimura, Y., et al. (2023) Light-driven Proton Pumps as a Potential Regulator for Carbon Fixation in Marine Diatoms. Microbes Environ 38: ME23015.

https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME23015

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Yusuke Matsuda for his useful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 18K19224, 18H04136, and 22H00557 to S.Y., 19H04727, 21H00404, and 21H02446 to Y.S., and 19H03274 to R.K., and NSF grant OPP1745036 to A.M. This research was partially supported by the Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research Program of the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, the University of Tokyo.

References

- Balashov, S.P., Imasheva, E.S., Boichenko, V.A., Anton, J., Wang, J.M., and Lanyi, J.K. (2005) Xanthorhodopsin: a proton pump with a light-harvesting carotenoid antenna. Science 309: 2061–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beja, O., Aravind, L., Koonin, E.V., Suzuki, M.T., Hadd, A., Nguyen, L.P., et al. (2000) Bacterial rhodopsin: evidence for a new type of phototrophy in the sea. Science 289: 1902–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J., Tymoczko, J., and Stryer, L. (2010) Biochemistry, 7th edn. New York, NY: WH Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, B.D., and Beardall, J. (1987) Utilization of inorganic carbon by marine microalgae. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 107: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Czech, L., Barbera, P., and Stamatakis, A. (2020) Genesis and Gappa: processing, analyzing and visualizing phylogenetic (placement) data. Bioinformatics 36: 3263–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell, R.G., Azuma, T., Nomura, M., de Kerdrel, G.A., Paoli, L., Yang, S.S., et al. (2019) Principles of plastid reductive evolution illuminated by nonphotosynthetic chrysophytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 6914–6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichner, M., Thoms, S., Rost, B., Mohr, W., Ahmerkamp, S., Ploug, H., et al. (2019) N2 fixation in free‐floating filaments of Trichodesmium is higher than in transiently suboxic colony microenvironments. New Phytol 222: 852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, S., and Hedges, J. (2008) Chemical Oceanography and the Marine Carbon Cycle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, O.P., Lodowski, D.T., Elstner, M., Hegemann, P., Brown, L.S., and Kandori, H. (2014) Microbial and animal rhodopsins: structures, functions, and molecular mechanisms. Chem Rev 114: 126–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.B., Behrenfeld, M.J., Randerson, J.T., and Falkowski, P. (1998) Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281: 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, C.W., and Niyogi, K.K. (2017) The carbonic anhydrase CAH1 is an essential component of the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Nannochloropsis oceanica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: 4537–4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, M., Hosaka, T., Kojima, K., Nishimura, Y., Nakajima, Y., Kimura-Someya, T., et al. (2020) A unique clade of light-driven proton-pumping rhodopsins evolved in the cyanobacterial lineage. Sci Rep 10: 16752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, B.M., Dupont, C.L., Allen, A.E., and Morel, F.M.M. (2011) Efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of diatoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 3830–3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, B.M. (2014) A chloroplast pump model for the CO2 concentrating mechanism in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Photosynth Res 121: 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomura, K., Wilson, S.T., and Deutsch, C. (2019) Mechanistic model for the coexistence of nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis in marine Trichodesmium. mSystems 4: e00210-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, S., Yoshizawa, S., Nakajima, Y., Kojima, K., Tsukamoto, T., Kikukawa, T., and Sudo, Y. (2018) Spectroscopic characteristics of Rubricoccus marinus xenorhodopsin (RmXeR) and a putative model for its inward H+ transport mechanism. Phys Chem Chem Phys 20: 3172–3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E.L., Maberly, S.C., and Gontero, B. (2020) Insights on the functions and ecophysiological relevance of the diverse carbonic anhydrases in microalgae. Int J Mol Sci 21: 2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K., and Standley, D.M. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, P.J. (2004) Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts. Am J Bot 91: 1481–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, P.J., Burki, F., Wilcox, H.M., Allam, B., Allen, E.E., Amaral-Zettler, L.A., et al. (2014) The Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP): Illuminating the functional diversity of eukaryotic life in the oceans through transcriptome sequencing. PLoS Biol 12: e1001889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, M., Kojima, K., Nakao, S., Yoshizawa, S., Kawanishi, S., Shibukawa, A., et al. (2021) Functional expression of the eukaryotic proton pump rhodopsin OmR2 in Escherichia coli and its photochemical characterization. Sci Rep 11: 14765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, K., Miyoshi, N., Shibukawa, A., Chowdhury, S., Tsujimura, M., Noji, T., et al. (2020a) Green-sensitive, long-lived, step-functional anion channelrhodopsin-2 variant as a high-potential neural silencing tool. J Phys Chem 11: 6214–6218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, K., Ueta, T., Noji, T., Saito, K., Kanehara, K., Yoshizawa, S., et al. (2020b) Vectorial proton transport mechanism of RxR, a phylogenetically distinct and thermally stable microbial rhodopsin. Sci Rep 10: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueker, T.J., Dickson, A.G., and Keeling, C.D. (2000) Ocean pCO2 calculated from dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity, and equations for K1 and K2: validation based on laboratory measurements of CO2 in gas and seawater at equilibrium. Mar Chem 70: 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Man, D.L., Wang, W.W., Sabehi, G., Aravind, L., Post, A.F., Massana, R., et al. (2003) Diversification and spectral tuning in marine proteorhodopsins. EMBO J 22: 1725–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, A., Schruth, D.M., Durkin, C.A., Parker, M.S., Kodner, R.B., Berthiaume, C.T., et al. (2012) Comparative metatranscriptomics identifies molecular bases for the physiological responses of phytoplankton to varying iron availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E317–E325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, A., Catlett, D., Hopkinson, B.M., Ellis, K., and Cassar, N. (2015) Marine diatom proteorhodopsins and their potential role in coping with low iron availability. ISME J 9: 2745–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen, F.A., Kodner, R.B., and Armbrust, E.V. (2010) pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinf 11: 538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Y., Hopkinson, B.M., Nakajima, K., Dupont, C.L., and Tsuji, Y. (2017) Mechanisms of carbon dioxide acquisition and CO2 sensing in marine diatoms: a gateway to carbon metabolism. Philos Trans R Soc B 372: 20160403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, M.R.M., Choi, A.R., Shi, L.C., Bezerra, A.G., Jung, K.H., and Brown, L.S. (2009) The photocycle and proton translocation pathway in a cyanobacterial ion-pumping rhodopsin. Biophys J 96: 1471–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara, M., Aoi, M., Inoue-Kashino, N., Kashino, Y., and Ifuku, K. (2013) Highly efficient transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by multi-pulse electroporation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77: 874–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C.M., Mills, M.M., Arrigo, K.R., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P.W., et al. (2013) Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat Geosci 6: 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, G., Ollig, D., Fuhrmann, M., Kateriya, S., Mustl, A.M., Bamberg, E., and Hegemann, P. (2002) Channelrhodopsin-1: A light-gated proton channel in green algae. Science 296: 2395–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, K., Tanaka, A., and Matsuda, Y. (2013) SLC4 family transporters in a marine diatom directly pump bicarbonate from seawater. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 1767–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.M., Treguer, P., Brzezinski, M.A., Leynaert, A., and Queguiner, B. (1995) Production and dissolution of biogenic silica in the ocean—Revised global estimates, comparison with regional data and relationship to biogenic sedimentation. Global Biogeochem Cycles 9: 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhelt, D., and Stoeckenius, W. (1971) Rhodopsin-like protein from the purple membrane of Halobacterium halobium. Nature (London), New Biol 233: 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J.A. (1997) CO2-concentrating mechanisms: A direct role for thylakoid lumen acidification? Plant, Cell Environ 20: 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Riebesell, U., Wolfgladrow, D.A., and Smetacek, V. (1993) Carbon-dioxide limitation of marine-phytoplankton growth-rates. Nature 361: 249–251. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, M.A., Goepfert, T.J., and Ritt, J.T. (2008) Some thoughts on the concept of colimitation: Three definitions and the importance of bioavailability. Limnol Oceanogr 53: 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sineshchekov, O.A., Jung, K.H., and Spudich, J.L. (2002) Two rhodopsins mediate phototaxis to low- and high-intensity light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 8689–8694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamovits, C.H., Okamoto, N., Burri, L., James, E.R., and Keeling, P.J. (2011) A bacterial proteorhodopsin proton pump in marine eukaryotes. Nat Commun 2: 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich, J.L., Yang, C.S., Jung, K.H., and Spudich, E.N. (2000) Retinylidene proteins: Structures and functions from archaea to humans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 365–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. (2014) RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork, S., Moog, D., Przyborski, J.M., Wilhelmi, I., Zauner, S., and Maier, U.G. (2012) Distribution of the SELMA translocon in secondary plastids of red algal origin and predicted uncoupling of ubiquitin-dependent translocation from degradation. Eukaryot Cell 11: 1472–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, Y., Kusi-Appiah, G., Kozai, N., Fukuda, Y., Yamano, T., and Fukuzawa, H. (2021) Characterization of a CO2-concentrating mechanism with low sodium dependency in the centric diatom Chaetoceros gracilis. Mar Biotechnol 23: 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa, S., Kawanabe, A., Ito, H., Kandori, H., and Kogure, K. (2012) Diversity and functional analysis of proteorhodopsin in marine Flavobacteria. Environ Microbiol 14: 1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.