Abstract

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are increasingly considered for biomedical applications as drug-delivery carriers, imaging probes and antibacterial agents. Silver nanoclusters (AgNCs) represent another subclass of nanoscale silver. AgNCs are a promising tool for nanomedicine due to their small size, structural homogeneity, antibacterial activity and fluorescence, which arises from their molecule-like electron configurations. The template-assisted synthesis of AgNCs relies on organic molecules that act as polydentate ligands. In particular, single-stranded nucleic acids reproducibly scaffold AgNCs to provide fluorescent, biocompatible materials that are incorporable in other formulations. This mini review outlines the design and characterization of AgNPs and DNA-templated AgNCs, discusses factors that affect their physicochemical and biological properties, and highlights applications of these materials as antibacterial agents and biosensors.

Keywords: antibacterial, biosensors, DNA, nanoscale silver, silver nanoclusters, silver nanoparticles

Nanoscale silver is investigated for its distinct physiochemical and biological characteristics compared with larger scale bulk silver. Atomic silver nanostructures, only several nanometers in size, have a mixture of unique optical, catalytic and antibacterial properties [1–14]. Applying nanotechnology to silver allows for the precise assembly of silver nanostructures in a predictable and controllable fashion. The properties of nanoparticles depend heavily on their size and shape, which can be designed to achieve specific and unique qualities. Depending on the intended function, certain physical parameters of the nanoscale silver can be fine-tuned during synthesis to produce desirable characteristics. Furthermore, the chemical properties of silver nanostructures (e.g., composition, coating and in-solution reactivity) can be adjusted to avoid toxicity or agglomeration while maximizing system's effectiveness as biosensors and antibacterial agents [6,10,11,13–23].

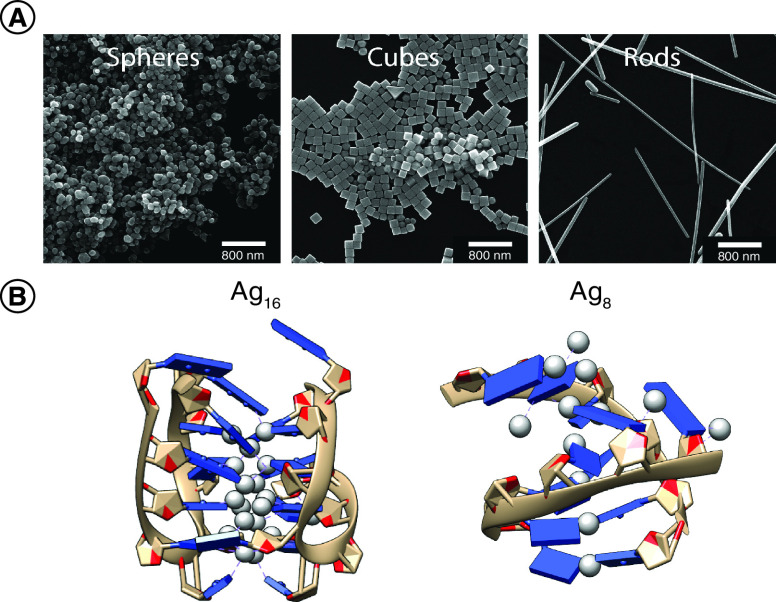

The worldwide concern of bacterial drug resistance, accelerated by misuse and overprescription of antibiotics [24], has become one of the main challenges facing our society. This issue is exacerbated by the declining interest of big pharmaceutical companies in developing new antibacterial treatments [25]. As antibiotics used in the clinic combat bacteria by affecting a specific mechanism or location of the cell, bacterial strains adapt to eventually become resistant to these treatments (Figure 1). One of the solutions would be the development of bacteria-specific therapies that employ a single active compound yet can efficiently target multiple essential biochemical pathways, thus delaying the bacterial evolution for drug resistance. Silver is well poised to fill this unique biomedical niche [26].

Figure 1. . Bacterial antibiotic resistance and list of some antibiotics affected.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), although well-affiliated with bactericidal activity, are still increasingly investigated for unique physicochemical and biological characteristics that are distinct from the bulk analogs [27]. Silver's efficacy as an antibacterial material, particularly when solubilized in its monovalent cation state, has been known since ancient times and is still under investigation [16,28,29]. Recently, AgNPs, consisting of a combination of cationic (Ag+) and elemental silver (Ag0), have been actively researched for their ability to serve as antibacterial agents in a variety of biomedical applications, such as burn/wound dressings or topical creams [26,29]. Due to the bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties of AgNPs that impact structural and biochemical features of pathogens, it becomes difficult for bacteria to evolve defense mechanisms [30–32]. Therefore, antibacterial properties of nanosilver become particularly appealing to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria and other emerging pathogenic threats.

Antibacterial properties of AgNPs

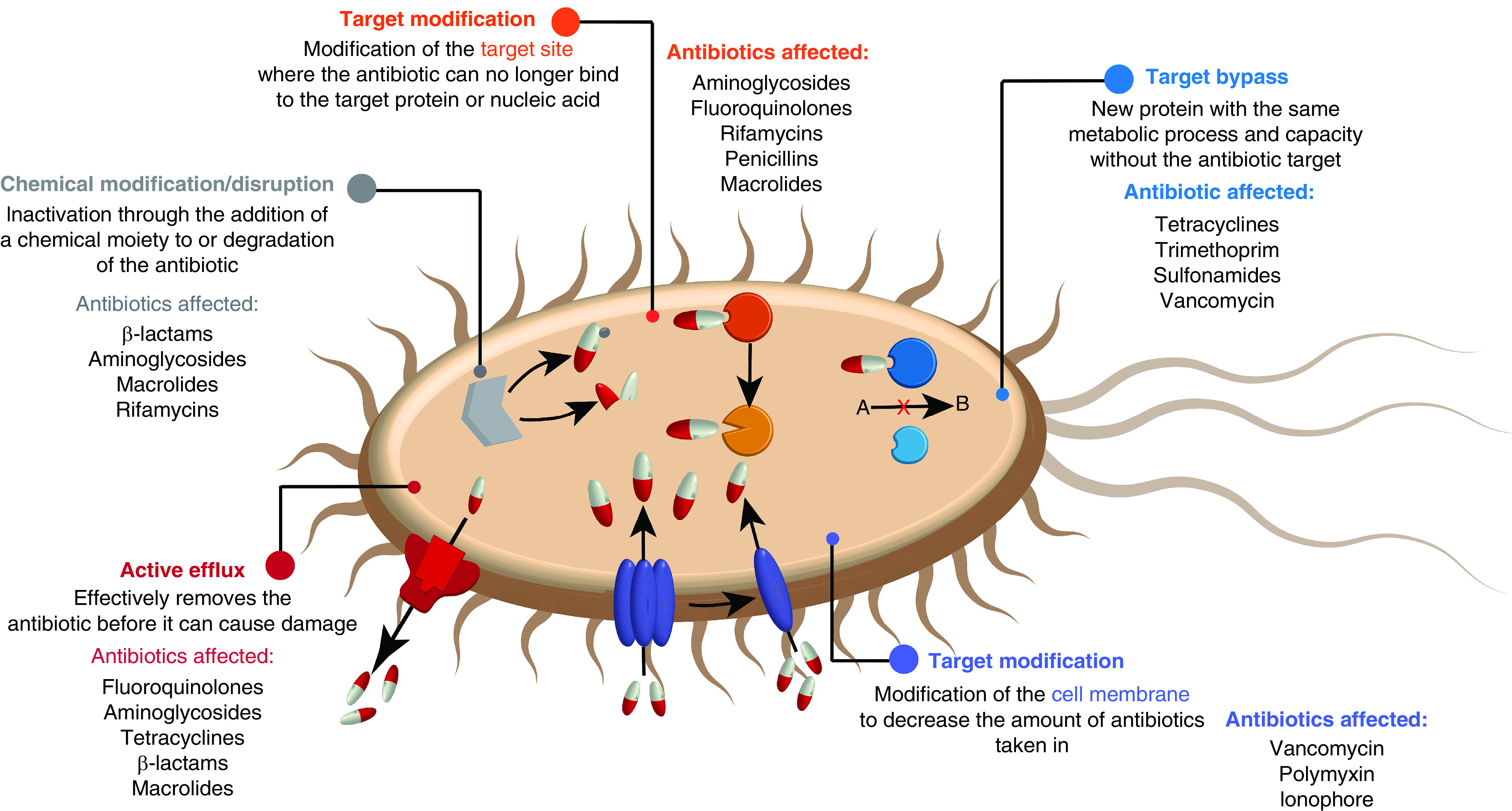

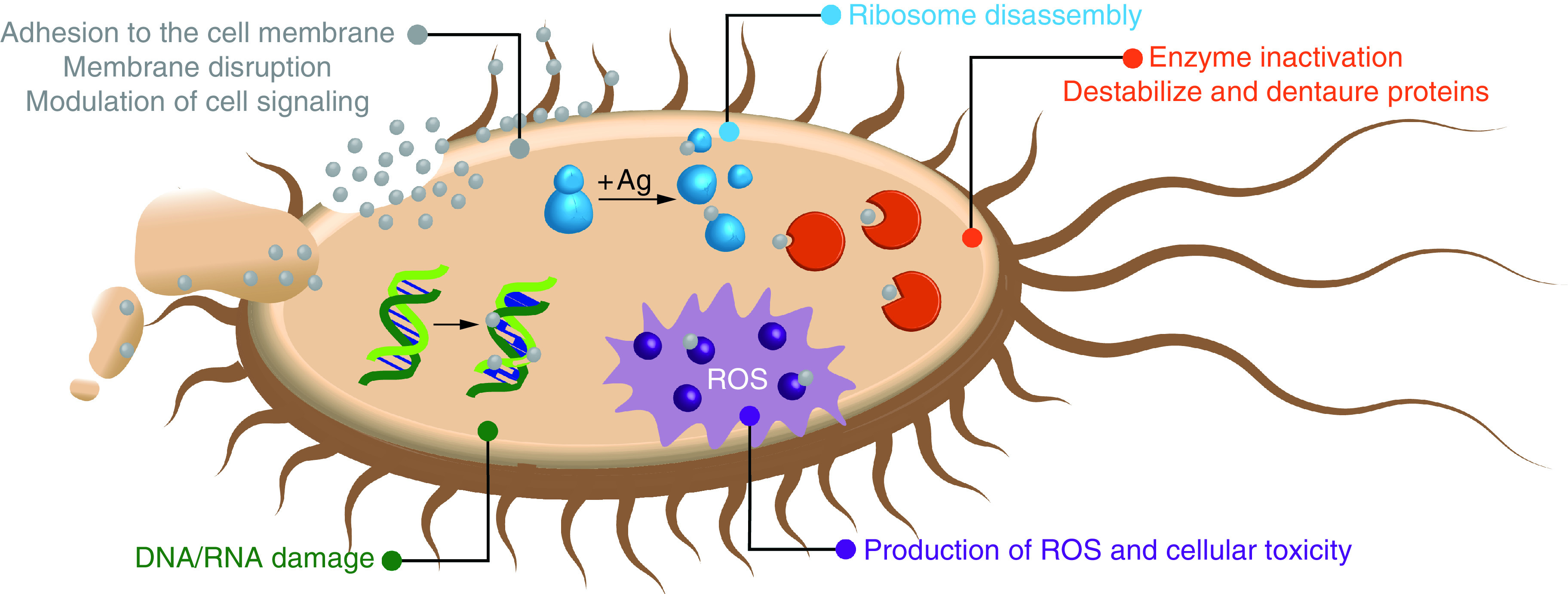

At very low concentrations, AgNPs inhibit bacterial growth while remaining nontoxic to mammalian cells [20]. The antibacterial and antiviral potential of AgNPs has sparked studies that elucidated the mechanisms of AgNPs' antimicrobial activity [33]. Colloidal silver and Ag+ interact with bacterial cell walls in a way that disrupts the membrane and increases its permeability [3,34,35]. AgNPs tend to cluster together on the surface of the bacterial cell, creating holes or pits in the cell wall and ultimately causing bacterial cell death [7]. Furthermore, the resultant increased permeability of the cell membrane allows AgNPs to penetrate the bacteria cells and leads to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause oxidative stress that reduces bacterial viability by damaging DNA, proteins and other intracellular biomolecules (Figure 2) [4,8,14]. It is commonly understood that the biological properties of nanoscale materials greatly vary depending on the size, shape and structure of the particle [36]. These factors should therefore be taken into consideration during the AgNP synthesis. The size of AgNPs has a significant effect on ROS production with smaller nanoparticles leading to higher ROS levels [14]. The size and shape of AgNPs also determine the way they interact with light. Generally, these interactions are dominated by surface plasmon resonance by AgNPs as small as 2 nm in diameter [11,37–39]. High proportions of surface area compared with particle volume likely contribute to the potent antibacterial properties of AgNPs assemblies. This is supported by the increased antibacterial efficacy of AgNPs as their size decreases [40,41], and across similar bacterial strains, smaller AgNPs demonstrate a stronger antibacterial efficacy than larger ones [42]. The shape of AgNPs also have a significant effect on their potency as antibacterial agents, with thinner plate-like structures typically performing the best (examples of different nanosilver shapes are shown in Figure 3A) [40,43,44]. The intended in-solution reactivity of AgNPs can be additionally enhanced via surface chemistry and functionalization which help to avoid aggregation and lower toxicity [45,46].

Figure 2. . Silver nanoparticles on bacterial cell.

ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

Figure 3. . Representative structures of sliver nanoparticles and DNA-templated silver nanoclusters.

(A) Examples silver nanoparticles are shown in a variety of shapes including spheres, cubes and rods (adapted with permission from [44] © The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2016). (B) Crystal structures of two DNA-AgNCs with 16 or 8 silver atoms in the cluster structures [47,48].

Regardless of the multimodal antibacterial properties, which harbor advantages compared with traditional antibiotics, AgNPs are not without limitations, most notably heterogeneity and possible in vitro and in vivo toxicity [49,50]. Several reports describe a wide range of different AgNPs that vary greatly in synthesis methods and, importantly, in the methods of antibacterial studies. It remains challenging to compare reported efficacies using different methodologies and materials [49]. AgNPs' toxicity toward human cells is highly dose, size and time dependent; additionally, long-term exposure is recognized to lead to chronic disorders of the skin and eyes [51,52]. Furthermore, the synthesis of highly monodisperse AgNPs remains a challenge due to aggregation, which significantly impacts the bioactivities and toxicity of AgNPs [53].

Similar to AgNPs, other nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), are also studied for antibacterial applications [54,55]. The size and dimensionality of AuNPs can be varied by synthesis method, similar to the production of AgNPs. Unlike AgNPs, AuNPs have photothermal properties. When a specific wavelength of light is absorbed by AuNPs, the energy is transformed to heat; this phenomenon is applied in cancer therapy to facilitate localized tumor cell death [56,57]. Similarly, the plasmonic photothermal effect of AuNPs can be used to promote bacterial cell death. This has been successfully demonstrated using Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a suspension of AuNPs [58]. Following continuous exposure to a laser beam, bacterial viability is reduced. In contrast to AuNPs, AgNPs offer a convenient option for antibacterial applications because they do not require external energy input to destroy bacteria [59].

Physicochemical & antibacterial properties of DNA-templated silver nanoclusters

In contrast to AgNPs, DNA-templated silver nanoclusters (DNA-AgNCs) are discreetly structured collections of only 5–30 silver atoms (Table 1). Although previous work has demonstrated the efficacy of DNA-AgNCs as antibiotics, further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of antibacterial activity or correlate the inherent fluorescence properties of AgNCs to their biological activity. Although it is commonly accepted that a significant contributor to the antibacterial efficacy of AgNPs is the production of ROS and the slow release of Ag+ ions into solution, only ROS production has been implicated in DNA-AgNCs activity [3,15,17,34]. This initial correlation indicates the need for further detailed studies of antibacterial mechanisms and identifying factors that can effectively modulate antibacterial activity – for example, the relative age of the DNA-AgNCs, the arrangement of DNA-AgNCs in 3D space, and the changes in the local concentration of DNA-AgNCs. It is important to note that Ag+ ions might be released from the DNA-AgNCs, but it is unlikely that the release of ions from the DNA-stabilized cluster is pH dependent within a physiologically relevant range because DNA-AgNCs retain their fluorescence over a wide range of pH conditions [60]. In addition, DNA-AgNCs, which undergo significant changes to their fluorescence after aging for several weeks, can fully restore their fluorescence upon re-reduction with NaBH4 [13]. Both of these observations imply a stable DNA-AgNC core that, although it may undergo changes in the oxidation state, likely does not change in cluster size or number of silver atoms [20]. The optical properties of DNA-AgNCs are generally dominated by fluorescence, which arises due to the molecule-like electronic structure of AgNCs [61].

Table 1. . A comparison of physicochemical properties of silver nanoparticles and DNA-templated silver nanoclusters.

| Size | Silver nanoparticles Multiatomic structure |

DNA-templated silver nanoclusters Discreet number of silver atoms |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis requirements | Capping agent, silver precursor and reducing agent | Templating oligonucleotide, silver precursor and reducing agent |

| Synthesis procedure | Physical, chemical and green synthesis methods are available | Silver ion reduction in the presence of single-stranded DNA |

| Colloidal stability | Changes with various capping agents | Stable in solution |

| Chemical stability | Addition of surfactants can modulate surface Ag+ release from | Ag0 oxidizes to Ag+ over time |

| Optical properties | Efficient surface plasmon resonance photo effect | Strong and adjustable fluorescence defined by ssDNA sequence |

| Homogeneity | High polydispersity due to nonuniform particle synthesis | Batch-to-batch consistency |

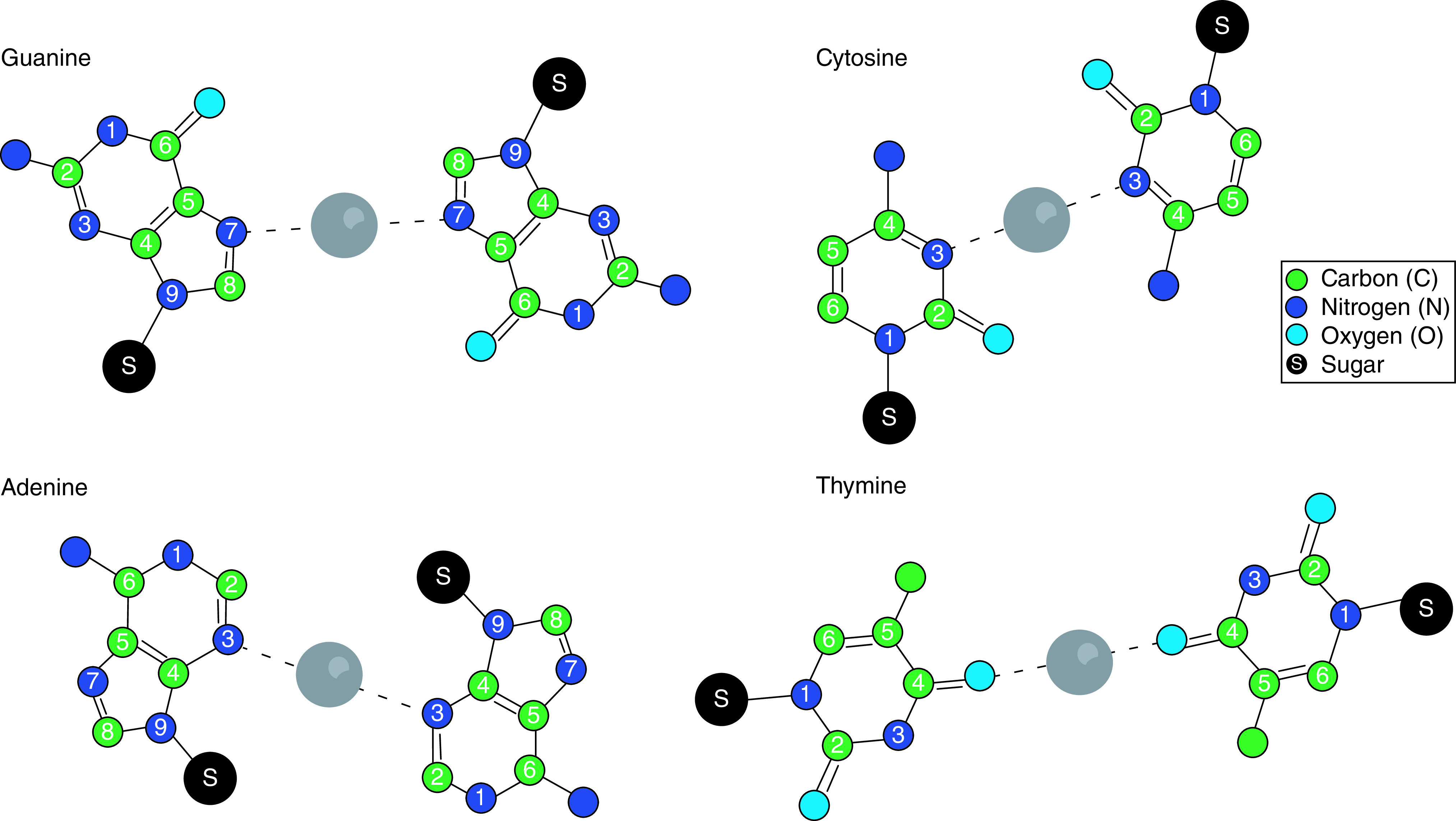

Generally, AgNC formation can be templated by a variety of ligands, such as small molecules, polymers and biomolecules [6,61,62]. If single-stranded (ss) nucleic acids, ssDNA or ssRNA, are used as templates, the size and fluorescence of resulting DNA-AgNCs can be regulated by the sequence of the templating oligonucleotide [2,6,20,60–66]. Generally, DNA-AgNCs include cytosine-rich sections, as cytosine has the highest affinity for Ag+ of the four DNA nucleobases (Figure 4) [62]. While ssDNA templates the formation of DNA-AgNCs, silver can also stabilize nucleic acid secondary structures, such as i-motifs and G-quadruplexes [62,67–69].

Figure 4. . Silver binding to nucleic acid bases.

Recently obtained crystal structures (Figure 3B) seem to support this by demonstrating the multidentate chelation of AgNCs by ssDNA in a manner that is consistent with the formation of dative bonds between endocyclic nitrogens or exocyclic oxygens of the nucleobases and silver atoms, as well as the formation of Ag–Ag bonds within the cluster [69,70]. Two recent crystal structures shed light on the chemistry involved in the formation of DNA-AgNCs, revealing the formation of dative bonds between endocyclic nitrogen atoms that have accessible lone pairs of electrons in the plane of the nucleobase [69,70]. On cytosine bases, this bond is formed with the N3 nitrogen. Other interactions, also likely to be dative bonds, are formed between the exocyclic O2 and N4 atoms, allowing the nucleobases and the entire oligonucleotide to act as a polydentate ligand in the chelation of silver atoms. In the case of the N4 atoms, it is possible that this involves the deprotonation of the N4 amine because it is expected for the pKa to be reduced in the presence of metal ions [69–71]. Similar interactions occur with the endocyclic N1 and exocyclic N6 nitrogen atoms of adenine [69,70].

The antibacterial properties of DNA-AgNCs can be compared with those of AgNPs; however, DNA-AgNCs may harbor enhanced antibacterial characteristics when compared to their larger AgNP counterparts due to increased stability and tunability provided by the DNA template [15]. Just as with AgNPs, the production of ROS is primarily associated with the antibacterial mechanisms of DNA-AgNCs [72]. The overproduced ROS likely damages bacterial DNA, leading to apoptosis [73]. It is expected that there are other mechanisms at play, yet inclusive mechanistic studies of DNA-AgNC to bacterial cell interactions are still lacking, with the primarily indicated DNA-AgNC bactericidal mechanism being interference and damage of bacterial DNA, preventing replication [74]. Of particular interest is the positive correlation in the optical properties and antibacterial efficacies of DNA-AgNCs, both of which highly modifiable by tuning the oligonucleotide template sequence and length [20]. By taking advantage of this relationship, new approaches are taken for designing nanostructures capable of bacterial sensing and visualization as well as growth inhibition [75]. Although the inefficiency of DNA-AgNC fluorescence and limited shelf-life have presented as a challenge, precise modification of the templating oligonucleotide structure can result in increased stability and enhanced fluorescence [22]. DNA-AgNCs can be applied to demonstrate detection, reduction and prevention of P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, a finding that shows promise for the use of DNA-AgNCs in combating harmful bacterial biofilms without the risk of encouraging development of antibiotic resistance [76]. P. aeruginosa are also used as a model for aptamer-functionalized DNA-AgNCs, which displayed increased antibacterial efficacies compared with DNA-AgNCs not containing the P. aeruginosa-specific aptamer [19]. DNA-AgNCs may be used in conjunction with the few antibiotics which remain effective against multidrug resistant bacteria to slow down or potentially prevent the bacterial species to develop resistance. This is demonstrated with daptomycin in combination with DNA-AgNCs to include multiple bactericidal mechanisms upon already multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [77]. Importantly, DNA-AgNCs are known to display significant antibacterial efficacy in low concentrations and can therefore combat bacterial infection in vivo and in vitro without harming or displaying toxicity towards mammalian cells [20,78]. Therefore, DNA-AgNCs for applications combating multidrug resistance are not only comparable but potentially preferable to AgNPs.

Computational studies of DNA-AgNCs

Various computational approaches can be applied to investigate stability of AgNCs, absorption and emission spectra, geometry of AgNCs, binding strength and electron transfer between DNA and AgNCs. The type of AgNCs for these studies vary by size, net charges, nanocluster geometry and binding sites. Most theoretical research agrees with several discoveries, such that the shape of AgNCs bound to DNA is rod-like or thread-like and that electron population transfers between AgNCs and DNA. However, there are some discrepancies among research groups in binding strength, binding sites and stability of complex between parallel and antiparallel strands DNAs.

The absorption and circular dichroism (CD) spectra of neutral naked silver nanochains without any DNA components have been investigated [79]. The size of the naked silver nanochains vary from 4 to 12 atoms. Although the optical absorption spectra of both planar and helical structures are similar, the planar structures show no CD signals while the helical structures produce strong CD spectra. In addition, the intensity and shape of the CD spectra are strongly influenced by helical geometry. The authors, agreeing with other reports, show that the spectrum redshifts and the peak intensity is enhanced as the number of silver atoms increases [80].

The interactions between AgNCs and bare DNA bases are studied by several research groups. Among these studies includes the binding strength between a pair of silver atoms (Ag2) and bare DNA bases [81]. The binding strength of cytosine is highest, those of both adenine and guanine are next, and thymine is the weakest binder. The geometries and stabilities of Ag+ mediated base pairing in homo-base deoxyoligonucleotides are also investigated [82]. It is reported that the G-Ag+-G ground state has the highest binding energy with coplanar conformation, while that of C–Ag+–C shows the next highest binding energy with slightly bent coplanar geometry. Additionally, Ag+ bridges to the N7 atom of guanine and the N3 atom in cytosine. In contrast, both A–Ag+–A and T–Ag+–T show twisted non-coplanar geometry with small binding energy which explains why Ag+ mediated adenine and thymine homo-base pairs are not observed experimentally. Investigations of the binding of the neutral AgnNCs (n = 8, 10, 12) to adenine, guanine and Watson–Crick (WC) A:T and G:C base pairs are reported [83]. It is demonstrated that the binding strength of AgNCs in the WC base pair is stronger than those of isolated DNA complexes. In addition, the electron charge is transferred from the DNA/WC bases to the AgNCs. The specific interactions between AgNCs and guanine are studied by two research groups. One of these found that the neutral AgNCs prefer to bind to the π system or N3 atom while all cationic and dicationic AgNCs are favored to bind N7, oxygen and carbonyl groups [84]. Interestingly, the Ag5+−guanine complex forms a trapezoid-like AgNC which was also captured by crystal structure [69]. Another group, which researches Ag+ mediated cytosine and guanine homo-bases, found that both cytosine and guanine form stable parallel Ag+ mediated double helix due to interplanar hydrogen bond interactions [85–87].

The AgNCs bound to DNA strands and their emissions are analyzed by several research groups. Studies of the geometry and excitation spectra of neutral and charged silver atoms bound to single DNA bases and dC3 oligomers show that the absorption spectra of planar AgNCs bound to N atoms of DNA bases are weak and do not match the excitation spectra of the emitting AgNCs [88]. Excitation spectra of the threadlike AgNCs are similar to those of observed fluorescent polymer-stabilized AgNCs. Furthermore, the excitation spectrum of threadlike analogs in the minor groove in the dC3 oligomer is well matched to the fluorescence excitation spectrum of green emitting clusters. However, the computational studies show that the Ag3+1 cluster binds to oxygen atoms on phosphates, whereas most other computational studies propose that AgNCs bind nitrogen atoms in cytosine or guanine [81–84,87]. The fluorescence excitation spectra of a planar (Ag3+) and a zigzag (Ag4+) clusters bound to a 12-mer DNA are demonstrated [89]. QM/MM-MD simulations show that the planar Ag3+ emits violet and green lights when it is bound to the DNA hairpin loop and cytosine rich site, respectively. The zigzag Ag4+ bound to DNA T-T mismatch site emits red spectra. As the source of the excited state of the complex, they show that charges transfer from AgNCs to DNA. The emission spectrum of planar Ag3+ clusters bound to CT2 and C4 units as well as a DNA hairpin in which CT2 and C4 form a dimer [90]. The authors reported that two peaks at 3.47 and 3.69 eV in the emission spectrum of the dimer at the excitation energy of 3.69 eV are from Ag3 + C4 and Ag3 + CT2, respectively. They show that the 3.69-eV laser pulse induces the electron population transfer to the S1 state of Ag3 + CT2 and the S2 state of Ag3 + C4. However, when the 3.47-eV laser pulse is tested, no coupled excited state, as well as no energy transfer, between the AgNCs is observed.

Three DNA-AgNCs with six to eight silver atoms bound to C6–C6 duplex have also been reported recently [91]. All central silver cores bind to N3 atoms in cytosine, whereas no oxygen binds to silver. In addition, the conformations of all core silver atoms show two-row planar shape which bridges DNA strands. Interestingly, their computational work shows a trapezoidal conformation of the Ag5 core which was also found in the x-ray structure [69]. In the crystal structure, the Ag8 cluster is bound to a cytosine-rich (A2C4) oligonucleotide where the Ag5 core forms a trapezoidal structure. In addition, the authors identified the source of first peaks in the optical absorption spectra and CD are due to the transitions between HOMO state in silver atoms and the unoccupied states in the DNA moiety. Therefore, their computational studies support the results that the low-energy peaks in the optical spectra and CD are due to the electronic transitions from Ag atoms to the DNA.

As described earlier, most theoretical research groups agree that the AgNCs bound to DNA form a rod-like or thread-like shape [79,80,84,88,89,91–96]. Additionally, the charge transition between AgNCs and DNA is generally agreed upon. The charges transfer from DNA to neutral AgNCs [83,88,96], whereas charge transitions occur from charged AgNCs to DNA [88–91]. In contrast, the major discrepancy among the theoretical research groups is the stability of DNA-AgNCs clusters complex in parallel and antiparallel DNA duplex. It has been shown that the parallel duplex is more stable than the antiparallel duplex in terms of helical geometry and hydrogen bond interactions [86]. The stability of DNA-AgNCs complexes by parallel strands has also been found by other research groups [97–100]. However, the antiparallel silver-mediated double-helix structure matches well with the crystal structure [101]. Additional work has shown fluorescence activation due to the neutral AgNC (Ag4) mediated two short antiparallel cytosine rich DNA duplex formation [80]. The optical spectrum shift has been shown to be red due to an increase of energy of the S1 as the size of the AgNC increases, which is also apparent in isolated silver nanochains [79]. There is also experimental evidence of AgNC mediated antiparallel strands [102,103]. The question of how parallel and antiparallel strands affect the stability of DNA-AgNC complexes remains to be answered.

Optical properties

The major light interaction that takes place between light in the UV-visible range and AgNPs is absorption via surface plasmon resonance [11,38,39,104]. The most efficiently absorbed wavelength is dependent on size and shape of the AgNP. Rod-like AgNPs with high aspect ratios can have multiple absorption peaks corresponding to the longitudinal and transverse modes along the nanorod. Spherical AgNPs tend to only show a single absorbance peak [11]. It is also impoprtant to note that the ligand used to stabilize the surface of the AgNPs can significantly impact the strength of the absorbance peaks [11,104]. AgNPs also have a significantly higher absorptivity than gold or platinum nanoparticles, which make AgNPs particularly easy to track spectroscopically [105].

The major peak in the UV-Vis absorbance spectra of DNA-AgNCs occurs at 260 nm [20]. Absorbance of 260 nm light is anticipated with nucleic acids and is largely dominated by π–π* transitions [106,107]. DNA-AgNCs are excited with both UV light, generally near 260 nm, and visible light, generally with a wavelength 50–150 nm less than the peak emission wavelength [108]. The absorbance of 260 nm light by DNA-AgNCs is likely to be slightly enhanced by the presence of the AgNCs [108,109]. The excitation of DNA-AgNCs with either of these wavelengths can lead to nearly identical emission spectra. The implication of these results is that both excited states relax to the same lowest energy excited state prior to emission. Computational results simulating AgNCs with 13 silver atoms ligated by 12 cytosines predict that the complex has a band gap, close to 2 eV, with charges of +5 or greater, corresponding to one of the experimentally observed ‘magic color’ emission near 630 nm (2 eV converts to ∼620 nm) [110,111]. Interestingly, this DNA-AgNC with a +5 charge on the AgNC moiety does correspond to one of the magic numbers predicted for metal superatoms with a closed shell of eight electrons. It is important to note in this determination that cytosines (and presumably other nucleobases) are not considered electron withdrawing ligands [110].

Metal clusters in general have a ‘magic number’ of neutral atoms that are stable due to the formation of closed electron shells following the cluster shell model [23,111–113]. This is not always the case with small AgNCs, however. Recent reports demonstrate stable AgNCs formed with open shell electronic structures [69,114]. From an analysis of DNA-AgNCs with well characterized clusters, the magic numbers of Ag0 are often found to be 4 and 6. Ag0 = 4 typically corresponds to ‘green’ fluorescent clusters, and Ag0 = 6 corresponds to ‘red’ fluorescent clusters, and while the total cluster size, Ag0 and Ag+, varies [111]. These magic numbers correspond to ‘magic colors’ of ‘red’ ∼630 nm and ‘green’ ∼540 nm [111]. These clusters may not be subject to the same constraints as spherical metal clusters (stable valence electron magic numbers of 2, 8, 18, 20 etc.), as expected, and recently confirmed via two crystal structures that DNA-AgNCs generally assume rod-like cluster shapes, which are better described by an ellipsoidal shell model [69,70,111,115,116].

Applications as biosensors

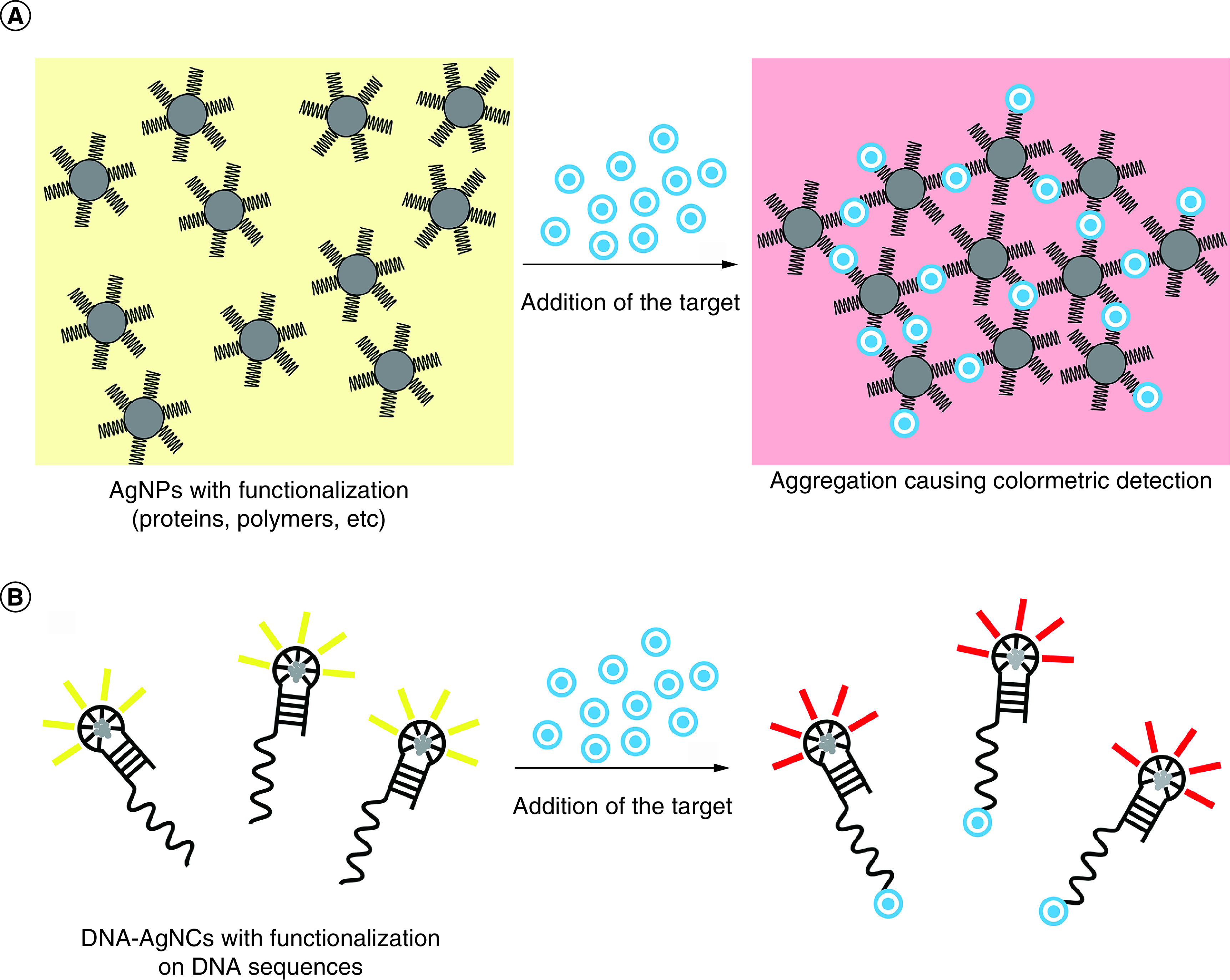

The use of AgNPs as biosensors for diagnostic testing and biomolecular detection has slowly begun to expand, with AgNPs in the center of the development to sense the presence of various biomarkers. For example, AgNPs are used to detect small molecules, such as dipicolinate, a sign of the presence of Bacillus anthracis [117]. This system employs the AgNPs as a surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate and intensifies the Raman scattering signal of the passively-adsorbed dipicolinate. Other groups take advantage of the peroxidase-like catalysis that AgNP nanozymes offer to develop colorimetric assays to detect glucose [118]. Moreover, the high available surface area on smaller AgNPs allows for attachment of surface functional groups (Figure 5A), which can be incorporated to achieve binding and biosensing dependent on the presence of a certain target. Other examples include the use of plasmonic AgNPs to sense melamine [119,120], tryptophan [121] and many other targets [122–128].

Figure 5. . Biosensing techniques.

(A) AgNPs: (left) interaction between the functionalization and the target causes a change in fluorescence; (right) the target links multiple AgNPs together to increase the fluorescence signal. (B) DNA-AgNCs: DNA is functionalized at the 3′ or 5′ end to interact with specific targets to cause a change in fluorescence.

AgNP: Silver nanoparticle; DNA-AgNC: DNA-templated silver nanocluster.

A significant advantage of using DNA-AgNCs is the ability to modify the nucleic acid template to detect endogenous nucleic acids in a sequence specific manner. This approach has yielded powerful probes for detecting disease-associated oligonucleotides. A system is demonstrated wherein the association of two strands with miR-371, a biomarker commonly found in prostate cancers, induces a shift in the fluorescence pattern of AgNCs templated on a substrate oligo. The system exhibited reliable detection of miR-371 at picomolar concentrations [129]. Other DNA-AgNC-based biosensors are designed to detect a wide array of substrates such as virus-associated nucleic acids and microRNAs [130–132]. DNA-AgNCs have a broad applicability beyond oligonucleotide detection as they can effectively detect pathogenic bacteria, disease antigens and numerous other substrates [133–136]. As exemplified in Figure 5B, DNA-AgNCs may be decorated with specific sequences, enabling target-dependent fluorescence.

Conclusion

The incorporation of silver in nanomedicine has thus far been primarily focused in the direction of sterilization of tools and preventing infection of open wounds. Frequent use of antibiotic drugs comes with the risk of encouraging development of antibiotic resistance in harmful bacterial species. The multivalent antibacterial activities of AgNPs and DNA-AgNCs are advantageous for use in sterile settings because bacteria are more likely to evolve effectively against mechanisms that inhibit bacterial viability via a certain and specific method. Recently, wound dressings that incorporate AgNPs are increasingly being developed to avoid reliance on antibiotics [137]. However, the unique composition of biocompatible DNA-AgNCs and programmability of DNA can allow for AgNCs to become readily incorporated in larger, multifunctional nucleic acid nanoparticles [13] that can be further programmed for specific targeting of certain bacteria strains in vivo. This combinatorial technology can open unforeseen possibilities for silver nanomaterials and significantly accelerate their translation into the clinical settings.

Executive summary.

Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles

The antibacterial mechanisms of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are well characterized.

Despite some limitations, AgNPs may be advantageous over other nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles in antibacterial treatments.

Physicochemical & antibacterial properties of DNA-templated silver nanoclusters

The size and resulting fluorescence of AgNCs are determined by the templating DNA sequence.

Crystal structures of DNA-templated silver nanoclusters (DNA-AgNCs) indicate that silver atoms contribute to a more stable DNA secondary structure.

By repeating reduction of DNA-AgNCs, their fluorescence that has changed due to oxidation can be restored.

DNA-AgNCs harbor antibacterial mechanisms that are yet to be comprehensively investigated.

DNA-AgNCs display enhanced antibacterial efficacies compared with AgNPs.

Computational studies of DNA-AgNCs

Silver atoms have the highest binding affinity for cytosine and the lowest binding strength for thymine.

Absorption and circular dichroism spectra demonstrate that peak intensities of AgNCs increase with the number of silver atoms.

Most DNA-AgNCs are rodlike or threadlike structures.

The stability of DNA-AgNCs may be impacted by the incorporation of parallel or antiparallel DNA duplexes.

Optical properties

AgNPs absorb light efficiently at varying wavelengths contingent on the size and shape of the nanoparticles.

The emission wavelength of AgNCs is dependent on the number of silver atoms on the DNA template.

Applications as biosensors

AgNPs are applied as detection systems for targeted biomolecules.

The tunable fluorescence of DNA-AgNCs is useful for the detecting of pathogenic or damaged oligonucleotide sequences.

Future perspective

Due to their multimodal antibacterial activities, AgNPs and DNA-AgNCs are strong assets to face the challenge of drug-resistant bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/nnm-2023-0082

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R35GM139587 (to KA Afonin). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Ranoszek-Soliwoda K, Tomaszewska E, Socha E et al. The role of tannic acid and sodium citrate in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. J. Nanoparticle Res. 19(8), 1–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gwinn EG, O'Neill P, Guerrero AJ et al. Sequence-dependent fluorescence of DNA-hosted silver nanoclusters. Adv. Mater. 20(2), 279–283 (2008). [Google Scholar]; •• Provides a significant investigation of the effects of the sequence of the templating oligo on the fluorescence of the resultant silver nanoclusters (AgNC).

- 3.Möhler JS, Sim W, Blaskovich MAT et al. Silver bullets: a new lustre on an old antimicrobial agent. Biotech. Adv. 36(5), 1391–1411 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morones-Ramirez JR, Winkler JA, Spina CS, Collins JJ. Silver enhances antibiotic activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Sci. Transl. Med. 5(190), 190ra181–190ra181 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afonin KA, Schultz D, Jaeger L et al. Silver nanoclusters for RNA nanotechnology: steps towards visualization and tracking of RNA nanoparticle assemblies. Springer, NY, USA, 59–66 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Y-P, Shen Y-L, Duan G-X et al. Silver nanoclusters: synthesis, structures and photoluminescence. Mater. Chem. Front. 4(8), 2205–2222 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 275(1), 177–182 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores-López LZ, Espinoza-Gómez H, Somanathan R. Silver nanoparticles: electron transfer, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, beneficial and toxicological effects. Mini review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 39(1), 16–26 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Chen Q, Gao C et al. A SiO2 NP–DNA/silver nanocluster sandwich structure-enhanced fluorescence polarization biosensor for amplified detection of hepatitis B virus DNA. J. Mater. Chem. B 3(6), 964–967 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai R, Mankad V, Gupta SK, Jha PK. Size distribution of silver nanoparticles: UV-visible spectroscopic assessment. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 4(1), 30–34 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F-K, Ko F-H, Huang P-W et al. Studying the size/shape separation and optical properties of silver nanoparticles by capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A 1062(1), 139–145 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Provides a thorough investigation of the effect of size and shape on the surface plasmon resonance of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs).

- 12.Yang L, Yao C, Li F et al. Synthesis of branched DNA scaffolded super-nanoclusters with enhanced antibacterial performance. Small 14(16), 1800185 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yourston L, Rolband L, West C et al. Tuning properties of silver nanoclusters with RNA nanoring assemblies. Nanoscale 12(30), 16189–16200 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson C, Hussain SM, Schrand AM et al. Unique cellular interaction of silver nanoparticles: size-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. J. Phys. Chem. B 112(43), 13608–13619 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javani S, Lorca R, Latorre A et al. Antibacterial activity of DNA-stabilized silver nanoclusters tuned by oligonucleotide sequence. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8(16), 10147–10154 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Provides one of the first investigations of the antibacterial efficacy of DNA-AgNCs.

- 16.Sim W, Barnard R, Blaskovich MAT, Ziora Z. Antimicrobial silver in medicinal and consumer applications: a patent review of the past decade (2007–2017). Antibiotics 7(4), 93 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian X, Jiang X, Welch C et al. Bactericidal effects of silver nanoparticles on lactobacilli and the underlying mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(10), 8443–8450 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyu D, Li J, Wang X et al. Cationic-polyelectrolyte-modified fluorescent DNA–silver nanoclusters with enhanced emission and higher stability for rapid bioimaging. Anal. Chem. 91(3), 2050–2057 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soundy J, Day D. Delivery of antibacterial silver nanoclusters to Pseudomonas aeruginosa using species-specific DNA aptamers. J. Med. Microbiol. 69(4), 640–652 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolband L, Yourston L, Chandler M et al. DNA-templated fluorescent silver nanoclusters inhibit bacterial growth while being non-toxic to mammalian cells. Molecules 26(13), 4045 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Liu W, Wu X, Gao X. Mechanism of pH-switchable peroxidase and catalase-like activities of gold, silver, platinum and palladium. Biomaterials 48, 37–44 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eun H, Kwon WY, Kalimuthu K et al. Melamine-promoted formation of bright and stable DNA–silver nanoclusters and their antimicrobial properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 7(15), 2512–2517 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desireddy A, Conn BE, Guo J et al. Ultrastable silver nanoparticles. Nature 501(7467), 399–402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T 40(4), 277–283 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson N, Czaplewski L, Piddock LJV. Discovery and development of new antibacterial drugs: learning from experience? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73(6), 1452–1459 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silver S, Phung LT, Silver G. Silver as biocides in burn and wound dressings and bacterial resistance to silver compounds. J. Indust. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33(7), 627–634 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chernousova S, Epple M. Silver as antibacterial agent: ion, nanoparticle, and metal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52(6), 1636–1653 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman RK, Surkiewicz BF, Chambers LA, Phillips CR. Bactericidal action of movidyn. Indust. Eng. Chem. 45(11), 2571–2573 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fong J, Wood F. Nanocrystalline silver dressings in wound management: a review. Int. J. Nanomed. 1(4), 441–449 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Mumtaz S, Li C-H et al. Combatting antibiotic-resistant bacteria using nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48(2), 415–427 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajipour MJ, Fromm KM, Ashkarran AA et al. Antibacterial properties of nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 30(10), 499–511 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X-F, Liu Z-G, Shen W, Gurunathan S. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, applications, and therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17(9), 1534 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruna T, Maldonado-Bravo F, Jara P, Caro N. Silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(13), 1–21 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathur P, Jha S, Ramteke S, Jain N. Pharmaceutical aspects of silver nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 46(sup1), 115–126 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorinolu AJ, Godakhindi V, Siano P et al. Influence of silver ion release on the inactivation of antibiotic resistant bacteria using light-activated silver nanoparticles. Mater. Adv. 3(24), 9090–9102 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morones JR, Elechiguerra JL, Camacho A et al. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 16(10), 2346 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alfagih IM, Aldosari B, Alquadeib B et al. Nanoparticles as adjuvants and nanodelivery systems for mRNA-based vaccines. Pharmaceutics 13(1), 1–27 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vodnik VV, Božanić DK, Bibić N et al. Optical properties of shaped silver nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 8(7), 3511–3515 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González AL, Noguez C. Optical properties of silver nanoparticles. Physica Status Solidi. 4(11), 4118–4126 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang S, Zheng J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: structural effects. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 7(13), 1701503 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agnihotri S, Mukherji S, Mukherji S. Size-controlled silver nanoparticles synthesized over the range 5–100 nm using the same protocol and their antibacterial efficacy. RSC Adv. 4(8), 3974–3983 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker C, Pradhan A, Pakstis L, Pochan DJ, Shah SI. Synthesis and antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 5(2), 244–249 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pal S, Tak Yu K, Song Joon M. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73(6), 1712–1720 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helmlinger J, Sengstock C, Groß-Heitfeld C et al. Silver nanoparticles with different size and shape: equal cytotoxicity, but different antibacterial effects. RSC Adv. 6(22), 18490–18501 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samberg ME, Oldenburg SJ, Monteiro-Riviere NA. Evaluation of silver nanoparticle toxicity in skin in vivo and keratinocytes in vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 118(3), 407–413 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Badawy AM, Silva RG, Morris B et al. Surface charge-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45(1), 283–287 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huard DJE, Demissie A, Kim D et al. Atomic structure of a fluorescent Ag8 cluster templated by a multistranded DNA scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141(29), 11465–11470 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerretani C, Kanazawa H, Vosch T, Kondo J. Crystal structure of a NIR-emitting DNA-stabilized Ag16 nanocluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58(48), 17153–17157 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duval RE, Gouyau J, Lamouroux E. Limitations of recent studies dealing with the antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles: fact and opinion. Nanomaterials 9(12), 1775 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao C, Li Y, Tjong SC. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(2), 449 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang X, Lu C, Tang M et al. Nanotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on HEK293T cells: a combined study using biomechanical and biological techniques. ACS Omega 3(6), 6770–6778 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carrola J, Bastos V, Jarak I et al. Metabolomics of silver nanoparticles toxicity in HaCaT cells: structure–activity relationships and role of ionic silver and oxidative stress. Nanotoxicology 10(8), 1105–1117 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bélteky P, Rónavári A, Igaz N et al. Silver nanoparticles: aggregation behavior in biorelevant conditions and its impact on biological activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 14, 667–687 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shamaila S, Zafar N, Riaz S et al. Gold nanoparticles: an efficient antimicrobial agent against enteric bacterial human pathogen. Nanomaterials (Basel) 6(4), 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okkeh M, Bloise N, Restivo E et al. Gold nanoparticles: can they be the next magic bullet for multidrug-resistant bacteria? Nanomaterials (Basel) 11(2), 1–28 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ali MRK, Wu Y, El-Sayed MA. Gold-nanoparticle-assisted plasmonic photothermal therapy advances toward clinical application. J. Phys. Chem. C 123(25), 15375–15393 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gharatape A, Davaran S, Salehi R, Hamishehkar H. Engineered gold nanoparticles for photothermal cancer therapy and bacteria killing. RSC Adv. 6(112), 111482–111516 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Bakri AG, Mahmoud NN. Photothermal-induced antibacterial activity of gold nanorods loaded into polymeric hydrogel against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Molecules 24(14), 1–19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Y, Kong Y, Kundu S et al. Antibacterial activities of gold and silver nanoparticles against Escherichia coli and bacillus Calmette–Guérin. J. Nanobiotechnol. 10, 19 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gambucci M, Cerretani C, Latterini L, Vosch T. The effect of pH and ionic strength on the fluorescence properties of a red emissive DNA-stabilized silver nanocluster. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 8(1), 014005 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Díez I, Ras RHA. Fluorescent silver nanoclusters. Nanoscale 3(5), 1963 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.New SY, Lee ST, Su XD. DNA-templated silver nanoclusters: structural correlation and fluorescence modulation. Nanoscale 8(41), 17729–17746 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yin N, Yuan S, Zhang M et al. An aptamer-based fluorometric zearalenone assay using a lighting-up silver nanocluster probe and catalyzed by a hairpin assembly. Microchim. Acta 186(12), 1–8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chandler M, Shevchenko O, Vivero-Escoto JL et al. DNA-templated synthesis of fluorescent silver nanoclusters. J. Chem. Educ. 97(7), 1992–1996 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo W, Yuan J, Dong Q, Wang E. Highly sequence-dependent formation of fluorescent silver nanoclusters in hybridized DNA duplexes for single nucleotide mutation identification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132(3), 932–934 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O'Neill PR, Velazquez LR, Dunn DG et al. Hairpins with poly-C loops stabilize four types of fluorescent agn:DNA. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(11), 4229–4233 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ai J, Guo W, Li B et al. DNA G-quadruplex-templated formation of the fluorescent silver nanocluster and its application to bioimaging. Talanta 88, 450–455 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sengupta B, Springer K, Buckman JG et al. DNA templates for fluorescent silver clusters and I-motif folding. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(45), 19518–19524 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huard DJE, Demissie A, Kim D et al. Atomic structure of a fluorescent Ag8 cluster templated by a multistranded DNA scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141(29), 11465–11470 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cerretani C, Kanazawa H, Vosch T, Kondo J. Crystal structure of a NIR-emitting DNA-stabilized Ag16 nanocluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 131(48), 17313–17317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lippert B. Alterations of nucleobase pK (a) values upon metal coordination: origins and consequences. Prog. Inorg. Chem 54, 385–447 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joshi N, Ngwenya BT, Butler IB, French CE. Use of bioreporters and deletion mutants reveals ionic silver and ROS to be equally important in silver nanotoxicity. J. Hazard. Mater. 287, 51–58 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prateeksha, Singh BR, Gupta VK et al. Non-toxic and ultra-small biosilver nanoclusters trigger apoptotic cell death in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans via RAS signaling. Biomolecules 9(2), 47 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tao Y, Aparicio T, Li M et al. Inhibition of DNA replication initiation by silver nanoclusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(9), 5074–5083 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang M, Chen X, Zhu L et al. Aptamer-functionalized DNA–silver nanocluster nanofilm for visual detection and elimination of bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13(32), 38647–38655 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sengupta B, Adhikari P, Mallet E et al. Spectroscopic study on Pseudomonas Aeruginosa biofilm in the presence of the aptamer-DNA scaffolded silver nanoclusters. Molecules 25(16), 3631 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng K, Setyawati MI, Lim T-P et al. Antimicrobial cluster bombs: silver nanoclusters packed with daptomycin. ACS Nano 10(8), 7934–7942 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu S, Yan Q, Cao S et al. Inhibition of bacteria in vitro and in vivo by self-assembled DNA-silver nanocluster structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14(37), 41809–41818 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karimova NV, Aikens CM. Time-dependent density functional theory investigation of the electronic structure and chiroptical properties of curved and helical silver nanowires. J. Phys. Chem. A 119(29), 8163–8173 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reveguk ZV, Pomogaev VA, Kapitonova MA et al. Structure and formation of luminescent centers in light-up Ag cluster-based DNA probes. J. Phys. Chem. C 125(6), 3542–3552 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee SP, Johnson SN, Ellington TL et al. Energetics and vibrational signatures of nucleobase argyrophilic interactions. ACS Omega 3(10), 12936–12943 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Swasey SM, Leal LE, Lopez-Acevedo O et al. Silver (I) as DNA glue: Ag+-mediated guanine pairing revealed by removing Watson–Crick constraints. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 10163 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Srivastava R. Complexes of DNA bases and Watson–Crick base pairs interaction with neutral silver Ag(n) (n = 8, 10, 12) clusters: a DFT and TDDFT study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 36(4), 1050–1062 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dale BB, Senanayake RD, Aikens CM. Research update: density functional theory investigation of the interactions of silver nanoclusters with guanine. APL Mater. 5, 053102 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Espinosa Leal LA, Karpenko A, Swasey S et al. The role of hydrogen bonds in the stabilization of silver-mediated cytosine tetramers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6(20), 4061–4066 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen X, Karpenko A, Lopez-Acevedo O. Silver-mediated double helix: structural parameters for a robust DNA building block. ACS Omega 2(10), 7343–7348 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen X, Makkonen E, Golze D, Lopez-Acevedo O. Silver-stabilized guanine duplex: structural and optical properties. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9(16), 4789–4794 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ramazanov RR, Kononov AI. Excitation spectra argue for threadlike shape of DNA-stabilized silver fluorescent clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C 117(36), 18681–18687 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ramazanov RR, Sych TS, Reveguk ZV et al. Ag–DNA emitter: metal nanorod or supramolecular complex? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7(18), 3560–3566 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lisinetskaya PG, Mitric R. Collective response in DNA-stabilized silver cluster assemblies from first-principles simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10(24), 7884–7889 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X, Boero M, Lopez-Acevedo O. Atomic structure and origin of chirality of DNA-stabilized silver clusters. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4(6), 065601 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yourston LE, Krasnoslobodtsev AV. Micro RNA sensing with green emitting silver nanoclusters. Molecules 25(13), 1–15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tao G, Chen Y, Lin R et al. How G-quadruplex topology and loop sequences affect optical properties of DNA-templated silver nanoclusters. Nano Res. 11(4), 2237–2247 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hsu H-C, Lin Y-X, Chang C-W. The optical properties of the silver clusters and their applications in the conformational studies of human telomeric DNA. Dyes Pigments 146, 420–424 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schultz D, Gardner K, Oemrawsingh SS et al. Evidence for rod-shaped DNA-stabilized silver nanocluster emitters. Adv. Mater. 25(20), 2797–2803 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berdakin M, Taccone M, Julian KJ et al. Disentangling the photophysics of DNA-stabilized silver nanocluster emitters. J. Phys. Chem. C 120(42), 24409–24416 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo W, Yuan J, Wang E. Oligonucleotide-stabilized Ag nanoclusters as novel fluorescence probes for the highly selective and sensitive detection of the Hg2+ ion. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) , 3395–3397 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yeh HC, Sharma J, Han JJ et al. A DNA–silver nanocluster probe that fluoresces upon hybridization. Nano Lett. 10(8), 3106–3110 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Petty JT, Sengupta B, Story SP, Degtyareva NN. DNA sensing by amplifying the number of near-infrared emitting, oligonucleotide-encapsulated silver clusters. Anal. Chem. 83(15), 5957–5964 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu H, Shen F, Haruehanroengra P et al. A DNA structure containing Ag(I) -mediated G:G and C:C Base Pairs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56(32), 9430–9434 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kondo J, Tada Y, Dairaku T et al. A metallo-DNA nanowire with uninterrupted one-dimensional silver array. Nat. Chem. 9(10), 956–960 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu Z, Xu L, Liz-Marzán LM et al. Sensitive detection of silver ions based on chiroplasmonic assemblies of nanoparticles. Adv. Optical Mater. 1(9), 626–630 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Toomey E, Xu J, Vecchioni S et al. Comparison of canonical versus silver(I)-mediated base-pairing on single molecule conductance in polycytosine dsDNA. J. Phys. Chem. C 120(14), 7804–7809 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peng S, McMahon JM, Schatz GC et al. Reversing the size-dependence of surface plasmon resonances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107(33), 14530–14534 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thompson DG, Stokes RJ, Martin RW et al. Synthesis of unique nanostructures with novel optical properties using oligonucleotide mixed-metal nanoparticle conjugates. Small 4(8), 1054–1057 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rodger A. UV absorbance spectroscopy of biological macromolecules. In: Encyclopedia of Biophysics. Roberts GCK (Ed.). Springer Berlin Heidelberg Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2714–2718 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rich A, Kasha M. The n → π* transition in nucleic acids and polynucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 82(23), 6197–6199 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- 108.O'Neill PR, Gwinn EG, Fygenson DK. UV excitation of DNA stabilized ag cluster fluorescence via the DNA bases. J. Phys. Chem. C 115(49), 24061–24066 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 109.Soto-Verdugo V, Metiu H, Gwinn E. The properties of small Ag clusters bound to DNA bases. J. Chem. Phys. 132(19), 195102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brown SL, Hobbie EK, Tretiak S, Kilin DS. First-principles study of fluorescence in silver nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. C 121(43), 23875–23885 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 111.Copp SM, Schultz D, Swasey S et al. Magic numbers in DNA-stabilized fluorescent silver clusters lead to magic colors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5(6), 959–963 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Teo BK, Yang S-Y. Jelliumatic shell model. J. Cluster Sci. 26(6), 1923–1941 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yoon B, Koskinen P, Huber B et al. Size-dependent structural evolution and chemical reactivity of gold clusters. ChemPhysChem 8(1), 157–161 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu C, Li T, Abroshan H et al. Chiral Ag23 nanocluster with open shell electronic structure and helical face-centered cubic framework. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schultz D, Gardner K, Oemrawsingh SSR et al. Evidence for rod-shaped DNA-stabilized silver nanocluster emitters. Adv. Mater. 25(20), 2797–2803 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.De Heer WA. The physics of simple metal clusters: experimental aspects and simple models. Rev. Modern Phys. 65(3), 611–676 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chrimes AF, Khoshmanesh K, Stoddart PR et al. Active control of silver nanoparticles spacing using dielectrophoresis for surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Anal. Chem. 84(9), 4029–4035 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jiang H, Chen Z, Cao H, Huang Y. Peroxidase-like activity of chitosan stabilized silver nanoparticles for visual and colorimetric detection of glucose. Analyst 137(23), 5560–5564 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Han C, Li H. Visual detection of melamine in infant formula at 0.1 p.p.m. level based on silver nanoparticles. Analyst 135(3), 583–588 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ma Y, Niu H, Zhang X, Cai Y. One-step synthesis of silver/dopamine nanoparticles and visual detection of melamine in raw milk. The Analyst 136(20), 4192 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li H, Li F, Han C et al. Highly sensitive and selective tryptophan colorimetric sensor based on 4,4-bipyridine-functionalized silver nanoparticles. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 145(1), 194–199 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Loiseau A, Asila V, Boitel-Aullen G et al. Silver-based plasmonic nanoparticles for and their use in biosensing. Biosensors 9(2), 78 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Provides a significant review of the capabilities of AgNPs as biosensors.

- 123.Xia Y, Ye J, Tan K et al. Colorimetric visualization of glucose at the submicromole level in serum by a homogenous silver nanoprism–glucose oxidase system. Anal. Chem. 85(13), 6241–6247 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Malicka J, Gryczynski I, Lakowicz JR. DNA hybridization assays using metal-enhanced fluorescence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306(1), 213–218 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang J, Malicka J, Gryczynski I, Lakowicz JR. Oligonucleotide-displaced organic monolayer-protected silver nanoparticles and enhanced luminescence of their salted aggregates. Anal. Biochem. 330(1), 81–86 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Endo T, Ikeda R, Yanagida Y, Hatsuzawa T. Stimuli-responsive hydrogel–silver nanoparticles composite for development of localized surface plasmon resonance-based optical biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 611(2), 205–211 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Xiong D, Li H. Colorimetric detection of pesticides based on calixarene modified silver nanoparticles in water. Nanotechnology 19(46), 465502 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Aslan K, Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Geddes CD. Metal-enhanced fluorescence solution-based sensing platform. J. Fluoresc. 14(6), 677–679 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fredrick D, Yourston L, Krasnoslobodtsev AV. Detection of cancer-associated miRNA using fluorescence switch of AgNC@NA and guanine-rich overhang sequences. Luminescence (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.He J-Y, Deng H-L, Shang X et al. Modulating the fluorescence of silver nanoclusters wrapped in DNA hairpin loops via confined strand displacement and transient concatenate ligation for amplifiable biosensing. Anal. Chem. 94(22), 8041–8049 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chen J, Wang M, Zhou C et al. Label-free and dual-mode biosensor for HPV DNA based on DNA/silver nanoclusters and G-quadruplex/hemin DNAzyme. Talanta 247, 123554 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wong ZW, Muthoosamy K, Mohamed NAH, New SY. A ratiometric fluorescent biosensor based on magnetic-assisted hybridization chain reaction and DNA-templated silver nanoclusters for sensitive microRNA detection. Biosensors Bioelectronics X 12, 100244 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ma L, Wang J, Li Y et al. A ratiometric fluorescent biosensing platform for ultrasensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium via CRISPR/Cas12a and silver nanoclusters. J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130234 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shamsipur M, Molaei K, Molaabasi F et al. Aptamer-based fluorescent biosensing of adenosine triphosphate and cytochrome c via aggregation-induced emission enhancement on novel label-free DNA-capped silver nanoclusters/graphene oxide nanohybrids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(49), 46077–46089 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang J, Guo X, Liu R et al. Detection of carcinoembryonic antigen using a magnetoelastic nano-biosensor amplified with DNA-templated silver nanoclusters. Nanotechnology 31(1), 015501 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Xu J, Zhu X, Zhou X et al. Recent advances in the bioanalytical and biomedical applications of DNA-templated silver nanoclusters. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 124, 115786 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yuan Y, Ding L, Chen Y et al. Nano-silver functionalized polysaccharides as a platform for wound dressings: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 194, 644–653 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.