Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Significant controversy exists regarding whether physicians factor personal financial considerations into their clinical decision making. Within oncology, several reimbursement policies may incentivize physicians to increase health care use.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate whether the financial incentives presented by oncology reimbursement policies affect physician practice patterns.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

Studies evaluating an association between reimbursement incentives and changes in reimbursement policy on oncology care delivery were reviewed. Articles were identified systematically by searching PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Proquest Health Management, Econlit, and Business Source Premier. English-language articles focused on the US health care system that made empirical estimates of the association between a measurement of physician reimbursement/compensation and a measurement of delivery of cancer treatment services were included. The Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions tool was used to assess risk of bias. There were no date restrictions on the publications, and literature searches were finalized on February 14, 2018.

FINDINGS

Eighteen studies were included. All were observational cohort studies, and most had a moderate risk of bias. Heterogeneity of reimbursement policies and outcomes precluded meta-analysis; therefore, a qualitative synthesis was performed. Most studies (15 of 18 [83%]) reported an association between reimbursement and care delivery consistent with physician responsiveness to financial incentives, although such an association was not identified in all studies. Findings consistently suggested that self-referral arrangements may increase use of radiotherapy and that profitability of systemic anticancer agents may affect physicians’ choice of drug. Findings were less conclusive as to whether profitability of systemic anticancer therapy affects the decision of whether to use any systemic therapy.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

To date, this study is the first systematic review of reimbursement policy and clinical care delivery in oncology. The findings suggest that some oncologists may, in certain circumstances, alter treatment recommendations based on personal revenue considerations. An implication of this finding is that value-based reimbursement policies may be a useful tool to better align physician incentives with patient need and increase the value of oncology care.

In the United States, physician compensation is commonly based on the fee-for-service model, in which physicians receive payment for each treatment rendered. Fee-for-service reimbursement may provide financial incentives for physicians to increase health care use, potentially leading to low-value and/or unnecessary care.1-7

Various alternative payment models have been proposed to replace the fee-for-service model, aiming to more closely align physician incentives with patient benefit. However, such changes have been unpopular with clinicians. Seventy-three percent of surveyed physicians preferred fee-for-service over other models,8 and specific reforms, such as bundled payments, were similarly unpopular (69% of surveyed physicians opposed).9 Some opposition may be rooted inperceived financialrisk9: fee-for-service is perceived as representing guaranteed income, whereas payment tied to performance metrics is often perceived as uncertain. Physicians may also favour current reimbursement arrangements because they are skeptical of the rationale that compensation influences physician treatment recommendations or care delivery; a survey of primary care physicians found that only 3% believed that financial incentives might influence their practice patterns.10

The question of physician response to reimbursement incentives is particularly relevant to oncology because existing reimbursement policies may incentivize over use of services. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services formula for physician administered Part B drugs makes reimbursement proportional to drugprice.Thispaymentmodelincentivizesoncologistsbothtoincreaseuseofsystemictherapyandtousemoreexpensivedrugsover lower-costalternatives.11 The per-treatment reimbursement model forradiotherapyalsoincentivizestheuseofagreaternumberofradiation fractions and discourages implementation of shorter, hypofractionated treatment plans.12–14 In addition, co-ownership of medical imaging and radio therapy facilities results in profitable self-referral arrangements within some practices, creating the financial incentive to increase use of these services.15

Prior literature reviews of financial incentives in healthcare have not focused on oncology.16–19 Therefore, although the aforementioned incentives are present in oncology care in the United States, whether they are associated with physician practice patterns has, to our knowledge, not been evaluated systematically. Alternative payment models intended to shift oncologists toward higher-value practices will be ineffective if oncologists do not, in actuality, respond to reimbursement incentives. We conducted a systematic review of the literature focused on empirically evaluating the question: do financial incentives present in US oncology care influence physician practice patterns and care delivery? The results of this systematic review are needed to inform future efforts at payment reform in oncology.

Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of 5 databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Proquest Health Management, Econlit, and Business Source Premier. There were no date restrictions. The search strategy contained 3 core components, linked using the AND operator: financial incentives (eg, reimbursement, incentives, fee for service, physician self-referral), physician behaviour (eg, practice patterns, physicians; physician’s role), and oncology (eg, oncology, chemotherapy, antineoplastic). The search was developed for PubMed/MEDLINE and then adapted for each of the other 4 databases by mapping these search terms to additional controlled vocabulary and subject heading terminology. All searches were finalized on February 14, 2018. Full details of all search terms can be found in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Study Selection

Results from all 5 database searches were downloaded into a reference management tool (Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation Ltd). After deduplication, titles and abstracts were screened independently by 2 reviewers (A.P.M., J.S.R., E.P., or D.R.). Disagreements were adjudicated by group consensus. All studies deemed eligible during title and abstract screening underwent full-text review by 2 independent reviewers (A.P.M., J.S.R., E.P., or D.R.); disagreements regarding inclusion were resolved by group consensus. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were published in English, (2) focused on the US health care system, (3) had full text available, (4) were empirical, peer-reviewed experimental or observational studies (eg, were not reviews, letters, case series, or practice guidelines), (5) studied physician reimbursement/compensation as the primary exposure of interest in 1 or more analyses, (6) studied an outcome that was a direct measurement of delivery of specific cancer treatment services (eg, not a measure of opinion or of health care spending), (7) contained a specific measure of contrast of the association of reimbursement/compensation with that outcome, and (8) focused on patients with cancer.

Data Abstraction

A standardized template was used to extract data on study characteristics (analytic period, study design, geographic location, funding source), experimental question (cohort eligibility and size, control group definition, type of reimbursement incentive analyzed, outcome), and results (outcome, type of effect measure, point estimates and 95% CIs or P values [where available]), and author’s stated conclusions. Data from each study were extracted by paired team members, with any disagreements subsequently resolved through discussion.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool20 was used to assess risk of bias (ROB). Each study was assessed on several domains individually and then provided an overall ROB. In accordance with ROBINS-I guidelines, the overall ROB score was as least as high as the highest-risk individual domain for each study. Possible scores were unclear, low, moderate, high, and critical. Owing to the characteristics of the studies in our sample, the ROB in the domains classification of interventions and deviations from intended interventions was assessed to below for all studies and therefore omitted from our results for brevity. The ROB for each study was assessed by paired team members, with any disagreements subsequently resolved through discussion. Studies assessed as having critical ROB were determined to be unable to contribute meaningfully to the understanding of reimbursement incentives in oncology practice and therefore were not included in the primary evidence synthesis. Studies assessed as critical ROB are listed in the eAppendix in the Supplement, along with justification for exclusion.

Results

eFigure 1 in the Supplement provides details on the study selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A total of 5693 studies were identified in our database searches. Of these, 45 were accepted for full-text review for eligibility, and 20 studies were found to be ineligible; reasons for ineligibility are detailed in the eAppendix and the specific ineligible studies are detailed in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The remaining 25 studies underwent data extraction and ROB assessment; 7 were determined to have critical ROB, leaving 18 studies for inclusion in the evidence synthesis.21–38 Because of heterogeneity in analytic questions, study designs, and effect measures, we did not perform a quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) of any outcome but instead performed a qualitative synthesis.

Study characteristics and findings are summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement. We found that each of the included studies addressed the question of reimbursement incentives in oncology through 1 of 3 broadly defined approaches: (1) by analyzing situations in which physicians received different compensation for the same treatment or in which 2 or more similar treatments resulted in different compensation at a given point in time, (2) by analyzing practice structure and/or self-referral arrangements for oncology services, or (3) by analyzing physician behavior in response to changing reimbursement for oncology services over time. Owing to the similarities among the studies within each experimental approach, the studies were grouped accordingly in both eTable 2 in the Supplement and in the evidence synthesis herein.

Risk of Bias

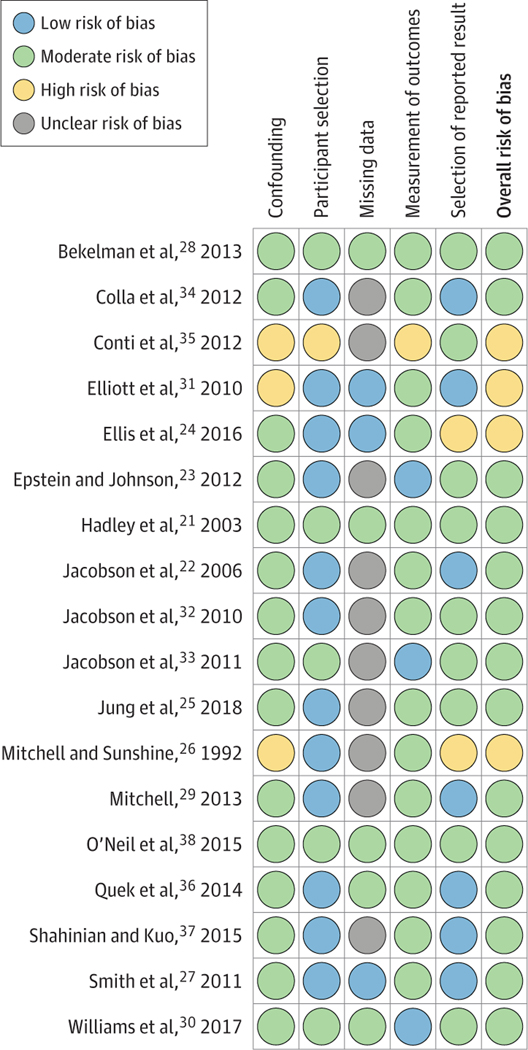

The Figure summarizes the ROB assessment of the 18 included studies. No study had lower than a moderate overall ROB because of the moderate or greater ROB owing to confounding in nonrandomized studies. Fourteen of the 18 studies (78%) were assessed as having moderate ROB.21–23,25,27–30,32–34,36–38 Four of the 18 studies (22%) were assessed as having high overall ROB, most commonly because of confounding or selection of the reported result.24,26,31,35 Low ROB because of participant selection was common, as many included studies used broad and uniformly applied claims-based criteria within large data sets. Unclear ROB owing to missing data was also common, as the frequency of missing data elements was not explicitly mentioned in several studies. The assessment of 2 domains (classification of interventions and deviations from intended interventions) showed a low risk of bias for all studies; those results are not shown. ROB assessment for studies with critical overall ROB can be found in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Figure.

Risk of Bias Assessment of Included Studies, Performed Using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions Tool

The assessment of risk of bias domains classification of interventions and deviations from intended interventions indicated a low risk of bias for all studies and are not shown.

Study Characteristics

Fifteen of the 18 studies were published in 2010 or later, and only 1 study was published before 2000. Prostate cancer was the most common cancer type, being the focus of 7 studies 24,28–31,36,37; 4 studies included multiple cancer types,22,25,26,383 focused on breast cancer, 21,23,27 2 on lung cancer,32,33 1 on bladder cancer,38 and 1 on colorectal35 cancer.Patient sample sizes ranged from 1787 to 878 923.

Five studies approached the question of reimbursement incentives by analysing differential compensation between physicians or treatments at a given time.21–25 Three of these studies used differences in Medicare reimbursement based on local carrier payment rates to estimate the association between treatment profitability and use,21,22,24 1 study analyzed physician use of different anticancer agents with respect to reimbursement for each agent,23 and 1 compared cancer treatment between health care systems that did vs did not qualify for the 340B drug discount.25 Five studies focused on the incentives created by self-referral for radiotherapy or delivery of radiotherapy in freestanding facilities.26–30 Eight studies analysed use of services as physician compensation for services changed overtime31–38; all but 2 of these studies35,38 analyzed changes in compensation for drug administration resulting from the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA).

Findings

Studies of Differential Compensation Between Physicians or Treatments

Five studies analyzed differential compensation between physicians or treatments at a given point in time.21–25 Of these, 4 studies with moderate ROB found that physicians respond to reimbursement incentives by preferentially using more-profitable treatments over less-profitable treatments21–23,25;1 study with high ROB found no evidence of such a response (eTable 2 in the Supplement).24

One study found evidence that physician reimbursement may be associated with the surgical approach to breast cancer.21 Physicians were more likely to use breast-conserving therapy plus adjuvant radiotherapy instead of mastectomy alone when either their reimbursement for breast-conserving therapy was higher or their reimbursement for mastectomy was lower. However, the same study did not find a statistically significant increase in breast-conserving therapy without adjuvant radio therapy in association with the same reimbursement differences.

Three studies found that reimbursement did not appear to be associated with the decision of whether to administer systemic therapy; the prevalence of systemic therapy was similar between patients treated by higher-reimbursed vs lower-reimbursed physicians 22,24 and between those treated by 340B vs non-340B health care systems.25 However, conditional on the receipt of systemic therapy, 2 studies identified a preference for more highly reimbursed treatment options,22,23 and 1 study identified a preference for administering treatment in the more profitable hospital out patient setting compared with the office setting.25

Studies of Practice Structure and Self-referral Practices

Five studies focused on the reimbursement incentives created by self-referral practices or practice structure—specifically, the delivery of radiotherapy in freestanding radiotherapy centers.26–30 Of these, 4studies with moderate ROB27–30 and 1study with high ROB26 found that physicians are more likely to use radio therapy when they or their practices profited through self-referral for radiotherapy or when practicing in freestanding facilities.

Two studies compared practice patterns in freestanding radiotherapyfacilitieswiththoseinnon-freestandingfacilities.26,27 Freestanding treatment facilities bill for both technical and professional fees and are more likely to be physician owned and involved in self-referral arrangements, resulting in a greater personal financial incentive to use treatments with substantial technical billing, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT).15,39,40 Freestanding facilities were associated with both a greater likelihood of receiving anyradiotherapy26 and with increased use of the more highly reimbursed treatment of IMRT over conventional radiotherapy.27

Three studies compared prostate cancer treatment between urology practices that were self-referring for radiotherapy and those that were not.28–30 Many urology practices are able to bill for radio therapy services by using the in-office referral exception to the Stark law.15,41 Two studies found that self-referral for radio therapy was associated with increased use of IMRT28,29; 1 study found that self-referral was associated with both receipt of any active therapy (radiotherapy, surgery, cryotherapy, or androgen deprivation therapy) and with receipt of radiotherapy specifically. 30One study found that the increase in radiotherapy associated with self-referral may replace other prostate cancer treatment modalities, observing a reduction in prostatectomy and a nonsignificant reduction in use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).28

Studies of Changes in Reimbursement for Oncology Services Over Time

Eight studies analyzed changes in physician compensation for services over time.31–38 Of these, 4 studies with moderate ROB32–34,38 and 2 studies with high ROB31,35 found evidence of physician response to reimbursement incentives; 2 studies with moderate ROB did not find evidence of response to incentives.36,37

Three of these studies examined the use of ADT for prostate cancer during a period in which treatment became less profitable because of implementation of the MMA. Of these, 2 studies found that the use of ADT in non–clinically indicated settings declined after MMA implementation 31,37; 1 of these studies also analysed the use of clinically indicated ADT over the same period and found that it did not decrease. 31However, 2 of these studies hypothesized that if this decline is due to physician response to reimbursement incentives, then a greater decline would be observed in private practice, where physician compensation is more closely tied to billing,42 compared with academic practice. Neither study found evidence that the observed decline in use of ADT in non–clinically indicated settings was greater in private practice than in academic practice.36,37

By examining the use of specific drugs that experienced different adjustments in reimbursement after MMA implementation, 1 study found that physicians decreased their use of drugs that showed the greatest declines in profitability.32 Another study found that after MMA implementation, patients dying of cancer were less likely to receive systemic therapy within the last 30 days of life.34

Several studies examined reimbursement changes other than the MMA. One study found that physicians used less irinotecan after the drug’s patent protection expired and a lower-cost, less profitable generic alternative became available.35 Another study found a significant increase in office-based cystoscopic procedures following an increase in reimbursement for procedures performed in the office setting and the absence of a coincident change in procedures performed in the hospital or ambulatory surgery settings, where reimbursement did not change.38

Studies With Critical ROB

Seven studies that met eligibility criteria were found to have critical ROB, and therefore were not included in our evidence synthesis.43–49 Three of these examined changes in use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents following a Medicare coverage restriction,46–48 2 examined the use of ADT for prostate cancer after implementation of the MMA,43,44 and 2 examined practice patterns within oncology clinician groups after the implementation of new payment models.45,49 Results of these studies and rationale for critical ROB assessment are reported in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review on physician response to financial incentives in oncology practice. This study extends previous knowledge by including research from biomedical, economic, and health care management disciplines and by conducting a broad systematic search to identify studies with different analytic questions, approaches, and outcomes. The findings of this review suggest that there is a somewhat limited body of research on physician reimbursement in oncology, but that most studies have found that reimbursement incentives are associated to some degree with the care received by patients with cancer in the United States.

Previous systematic reviews of physician responsiveness to financial incentives have focused on the primary care setting17,18 or thenon-USsetting.19 Moreover, much of the reviewed literature on financial incentives to physicians has focused on payment and incentive programs specifically intended to modify physician behavior (eg, pay for performance arrangements intended to increase use of particular primary care services or of high-value drug prescribing).17,19 In contrast, in this review we included both the intended and unintended consequences of payment structures already in place, rather than only programs designed to modify physician practice. We believe that this approach offers new insight into physician reimbursement. Not only can physician payment be considered a tool to drive practice improvement, but the consequences of payment policies not intended to alter clinical practice should also be carefully considered.

The idea that physicians may change their practice in response to financial incentives has ethical as well as practical implications. The American Medical Association Code of Ethics statement on conflicts of interest in medicine states that physicians may never“ place their own financial interests above the welfare of their patients,” and that this principle implies that they“ should not provide wasteful and unnecessary treatment that may cause needless expense solely for the physician’s financial benefit or for the benefit of a hospital or other healthcare organization with which the physician is affiliated.”50 Physicians may therefore be resistant to many of the findings included in this review, as the evidence of treatment in response to financial considerations may be perceived as a violation of ethical practice. Physicians have historically expressed skepticism that their individual practice could be influenced by financial considerations.10

Despite this skepticism, this review suggests that some physicians may be responsive to financial incentives in specific settings within the practice of oncology. Although existing ethical standards prohibit physicians from allowing personal financial gain to influence treatment decisions, it appears such ethical standards alone may be insufficient to constrain physician behavior. Given what we know from the psychological an deconomic sciences about the powerful role of incentives in shaping human behavior,51 expecting physicians to practice blind to incentives is unrealistic. The reimbursement incentives of cancer treatment may be particularly strong for physicians and practices facing financial hardship and attempting to remain solvent in the current landscape of health system consolidation and sequester-era reimbursement cuts.11 Certainly, a broader discussion of the ethical justification of physician response to financial incentives is warranted within the medical community.

This review highlights gaps in the literature. Most of the identified studies of systemic therapies analyzed past policy changes or payment models that are no longer in effect. The incentives present in the current, post-MMA “buy and bill” model are understudied and warrant further investigation, especially in light of the high prices of many targeted and immunotherapy drugs. We identified several studies of radiotherapy that analysed receipt of any radiation or IMRT as the primary treatment outcome. The number of treatment fractions administered is another decision where financial considerations may be important, and should also receive further investigation.

Limitations

This study has limitations related to its scope. To maintain our focus on reimbursement incentives, we excluded studies comparing oncology practice patterns between different health care systems. Such comparisons would be limited by the many differences between health care systems other than payment structure that may contribute to practice changes (our rationale for exclusion), such as differences in institutional formularies, peer effects,52 physician training,53 payer mix,54 and other variables known to affect cancer treatment; however, these studies may still provide additional insights into oncology reimbursement, which have been omitted from this review. Our findings should not be taken to imply that financial motivation is the only—or even a predominant—factor influencing physician practice in oncology. Many of the included studies found evidence that other factors appropriately drive treatment decisions, such as strength of clinical evidence for a treatment23 or patient disease characteristics.21 Our conclusions may be affected by publication bias if negative or null studies of reimbursement incentives in oncology were less likely to be published than positive ones. No included study had low ROB, owing to their observational, retrospective design; however, studies of reimbursement policies with low ROB (eg, randomized studies) may not be feasible.

We excluded 7 studies because of critical ROB. If included, these studies would have been unlikely to significantly affect the overall conclusions. Three of these studies analyzed the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents after a Medicare coverage change (each of which observed the hypothesized declines),46–48 2 studied ADT for prostate cancer after implementation of the MMA(both of which observed the hypothesized declines),43,44 and 2 others studied the implementation of alternative payment models within small oncology health care networks (neither of which observed statistically significant changes in practice patterns in their overall analyses).45,49

Conclusions

From a practical standpoint, this review suggests that oncology reimbursement policy may beauseful mechanism by which to improve care quality and disincentivize over use and identifies several specific areas where in such policy action may be warranted. The literature suggests that self-referral for radiation oncology services is associated with increased use.26–30 Changing these practices, as advocated by the American Society for Radiation Oncology, may therefore result in both lower health care spending and prevention of adverse effects from potentially inappropriate treatment.15 Changes in surgical fees may result in Changes in the volume of procedures performed 21,38 and should be considered carefully in light of medical necessity and the potential to result in both undertreatment and overtreatment. In addition, evidence that higher reimbursement may lead oncologists to favour higher-priced anticancer agents 23,32,35 and use systemic therapy in potentially harmful settings 34 provides a rationale to decouple reimbursement from drug price, such as under the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation pilot proposal on Part B drug payment.55

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

Do the financial incentives within oncology reimbursement affect physicians’ practice patterns?

Findings

In this systematic review of 18 studies that evaluated physicians’ response to reimbursement incentives across various clinical settings, most studies found evidence of an association between reimbursement incentives and delivery of cancer care. The ability to self-refer for radiation oncology services was associated with increased use of radiotherapy, and greater profitability of an anticancer drug was associated with increased use of that drug.

Meaning

How oncology care is reimbursed may affect clinical care delivery.

Funding/Support:

This research was partially supported by a National Research Service Award Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant 5T32 HS000032-28) (Dr Mitchell and Ms Patel) and by a Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (Dr Mitchell).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Additional Information: This review was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42018085892) on February 15, 2018.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wheeler has received research grant funding from Pfizer unrelated to this work. No other disclosures reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shah BR, Cowper PA, O’Brien SM, et al. Association between physician billing and cardiac stress testing patterns following coronary revascularization. JAMA. 2011;306(18):1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell JM. Urologists’ self-referral for pathology of biopsy specimens linked to increased use and lower prostate cancer detection. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):741–749. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber J, Owings M. Physician financial incentives and cesarean section delivery. Rand J Econ. 1996;27(1):99–123. doi: 10.2307/2555794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. Do physicians’ financial incentives affect medical treatment and patient health? Am Econ Rev. 2014;104(4):1320–1349. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.4.1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen LL, Smith AD, Scully RE, et al. Provider-induced demand in the treatment of carotid artery stenosis: variation in treatment decisions between private sector fee-for-service vs salary-based military physicians. JAMA Surg. 2017; 152(6):565–572. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingsworth JM, Ye Z, Strope SA, Krein SL, Hollenbeck AT, Hollenbeck BK. Physician ownership of ambulatory surgery centers linked to higher volume of surgeries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(4):683–689. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong AS, Ross-Degnan D, Zhang F, Wharam JF. Clinician-level predictors for ordering low-value imaging. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1577–1585. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Biesen T, Weisbrod J, Brookshire M, Coffman J, Paternak A. Front Line of Healthcare Report 2017. Bain & Co; 2017. http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/front-line-of-healthcarereport-2017.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federman AD, Woodward M, Keyhani S. Physicians’ opinions about reforming reimbursement: results of a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(19):1735–1742. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Too little? too much? primary care physicians’ views on US health care: a brief report. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1582–1585. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polite B, Conti RM, Ward JC. Reform of the buy-and-bill system for outpatient chemotherapy care is inevitable: perspectives from an economist, a realpolitik, and an oncologist. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e75–e80. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenup RA, Blitzblau RC, Houck KL, et al. Cost implications of an evidence-based approach to radiation treatment after lumpectomy for early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(4): e283–e290. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.016683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekelman JE, Sylwestrzak G, Barron J, et al.Uptake and costs of hypofractionated vs conventional whole breast irradiation after breast conserving surgery in the United States, 2008–2013. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2542–2550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konski A, Yu JB, Freedman G, Harrison LB, Johnstone PAS. Radiation oncology practice: adjusting to a new reimbursement model. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):e576–e583. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Self-referral Toolkit. American Society for Radiation Technology. https://www.astro.org/uploadedFiles/_MAIN_SITE/Advocacy/content_pieces/SelfReferralToolkit.pdf. Published February 2012. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- 16.Robertson C, Rose S, Kesselheim AS. Effect of financial relationships on the behaviors of health care professionals: a review of the evidence. J Law Med Ethics. 2012;40(3):452–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1748720X.2012.00678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD008451. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008451.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen IS, et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2000;(3):CD002215. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Rashidian A, Omidvari A-H, Vali Y, Sturm H, Oxman AD. Pharmaceutical policies: effects of financial incentives for prescribers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD006731. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006731.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355(October):i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadley J, Mandelblatt JS, Mitchell JM, Weeks JC, Guadagnoli E, Hwang YT; OPTIONS Research Team. Medicare breast surgery fees and treatment received by older women with localized breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):553–573. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson M, O’Malley AJ, Earle CC, Pakes J, Gaccione P, Newhouse JP. Does reimbursement influence chemotherapy treatment for cancer patients? Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(2):437–443. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein AJ, Johnson SJ. Physician response to financial incentives when choosing drugs to treat breast cancer. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2012; 12(4):285–302. doi: 10.1007/s10754-012-9117-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis SD, Chen RC, Dusetzina SB, et al. Are small reimbursement changes enough to change cancer care? reimbursement variation in prostate cancer treatment. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(4):e423–e436. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung J, Xu WY, Kalidindi Y. Impact of the 340Bdrug pricing program on cancer care site and spending in Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3528–3548. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell JM, Sunshine JH. Consequences of physicians’ ownership of healthcare facilities—joint ventures in radiation therapy. NEnglJMed. 1992;327 (21):1497–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211193272106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith BD, Pan I-W, Shih Y-CT, et al. Adoption of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for breast cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011; 103(10):798–809. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bekelman JE, Suneja G, Guzzo T, Pollack CE, Armstrong K, Epstein AJ Effect of practice integration between urologists and radiationon cologists on prostate cancer treatment patterns. JUrol. 2013;190 (1):97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell JM. Urologists’ use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1629–1637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1201141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams SB, Huo J, Chapin BF, Smith BD, Hoffman KE. Impact of urologists’ ownership of radiation equipment in the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20(3): 300–304. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2017.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott SP, Jarosek SL, Wilt TJ, Virnig BA. Reduction in physician reimbursement and use of hormone therapy in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(24):1826–1834. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson M, Earle CC, Price M, Newhouse JP. How Medicare’s payment cuts for cancer chemotherapy drugs changed patterns of treatment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7): 1391–1399. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson M, Earle CC, Newhouse JP. Geographic variation in physicians’ responses to a reimbursement change. N Engl J Med. 2011;365 (22):2049–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colla CH, Morden NE, Skinner JS, Hoverman JR, Meara E. Impact of payment reform on chemotherapy at the end of life. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3)(suppl):e6s–e13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conti RM, Rosenthal MB, Polite BN, Bach PB, Shih Y-CT. Infused chemotherapy use in the elderly after patent expiration. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3) (suppl):e18s–e23s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quek RGW, Master VA, Portier KM, et al. Association of reimbursement policy and urologists’ characteristics with the use of medical androgen deprivation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(6):748–760. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahinian VB, Kuo Y-F. Reimbursement cuts and changes in urologist use of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2015;15:25. doi: 10.1186/s12894-015-0020-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neil B, Graves AJ, Barocas DA, Chang SS, Penson DF, Resnick MJ. Doing more for more: unintended consequences of financial incentives for oncology specialty care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015; 108(2):djv331. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shumway DA, Griffith KA, Pierce LJ, et al. Wide variation in the diffusion of a new technology: practice-based trends in intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) use in the state of Michigan, with implications for IMRT use nationally. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):e373–e379. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts KB, Soulos PR, Herrin J, et al. The adoption of new adjuvant radiation therapy modalities among Medicare beneficiaries with breast cancer: clinical correlates and cost implications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85 (5):1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell JM. The prevalence of physician self-referral arrangements after Stark II: evidence from advanced diagnostic imaging. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):w415–w424. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desch CE, Blayney DW. Making the choice between academic oncology and community practice: the big picture and details about each career. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2(3):132–136. doi: 10.1200/jop.2006.2.3.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang SL, Liao JC, Shinghal R. Decreasing useof luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists in the United States is independent of reimbursement changes: a Medicare and Veterans Health Administration claims analysis. J Urol. 2009; 182(1):255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis SD, Nielsen ME, Carpenter WR, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist overuse: urologists’ response to reimbursement and characteristics associated with persistent overuse. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015;18(2):173–181. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feinberg B, Milligan S, Olson T, et al. Physician behavior impact when revenue shifted from drugs to services. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(4):303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gawade PL, Berlin JA, Henry DH, et al.Changes in the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and red blood cell transfusion in patients with cancer amidst regulatory and reimbursement changes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(11):1357–1366. doi: 10.1002/pds.4293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hershman DL, Neugut AI, Shim JJ, Glied S, Tsai W-Y, Wright JD. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent use after changes in Medicare reimbursement policies. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4): 264–269. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hess G, Nordyke RJ, Hill J, Hulnick S. Effect of reimbursement changes on erythropoiesis-stimulating agent utilization and transfusions. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(11):838–843. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loy BA, Shkedy CI, Powell AC, et al. Do case rates affect physicians’ clinical practice in radiation oncology?: an observational study. PLoS One. 2016; 11(2):e0149449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/conflicts-interest-patient-care. Accessed July 13, 2018.

- 51.Becker GS. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pollack CE, Soulos PR, Gross CP. Physician’s peer exposure and the adoption of a new cancer treatment modality. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2799–2807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ost DE, Niu J, Elting LS, Buchholz TA, Giordano SH Determinants of practice patterns and quality gaps in lung cancers tagging and diagnosis. Chest. 2014;145(5):1097–1113. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Churilla TM, Egleston B, Bleicher R, Dong Y, Meyer J, Anderson P. Disparities in the local management of breast cancer in the us according to health insurance status. Breast J. 2017;23(2):169–176. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.US Federal Register. Medicare Program: Part B Drug Payment Model. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/03/11/2016-05459/medicare-program-part-b-drug-payment-model.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.