Summary

Transcription factors (TFs) can define distinct cellular identities despite nearly identical DNA-binding specificities. One mechanism for achieving regulatory specificity is DNA-guided TF cooperativity. Although in vitro studies suggest it may be common, examples of such cooperativity remain scarce in cellular contexts. Here, we demonstrate how ‘Coordinator’, a long DNA motif comprised of common motifs bound by many basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) and homeodomain (HD) TFs, uniquely defines regulatory regions of embryonic face and limb mesenchyme. Coordinator guides cooperative and selective binding between the bHLH family mesenchymal regulator TWIST1 and a collective of HD factors associated with regional identities in the face and limb. TWIST1 is required for HD binding and open chromatin at Coordinator sites, while HD factors stabilize TWIST1 occupancy at Coordinator and titrate it away from HD-independent sites. This cooperativity results in shared regulation of genes involved in cell-type and positional identities, and ultimately shapes facial morphology and evolution.

Keywords: transcription factor, bHLH, homeodomain, TWIST1, ALX factors, mesenchyme, cooperativity, face, limb, neural crest, Coordinator

Introduction

Sequence-specific transcription factors (TFs) play a key role in controlling gene expression programs during embryonic development and in response to environmental cues. Forcibly expressing certain TFs often referred to as master regulators is sufficient to change a cell’s identity1. For example, overexpression of MyoD1 can convert fibroblasts into myoblasts2,3, while overexpression of NeuroD1 can induce terminal neuron differentiation4. TFs bind specific, typically short DNA sequences called motifs, and recruit coactivators or corepressors to modulate transcription5,6. However, many TFs fall into large families, and share highly conserved DNA-binding domains (DBDs) that often bind very similar DNA motifs across family members3,6. Even TFs that drive divergent gene expression programs can bind the same motifs3, raising the question of how they achieve regulatory specificity. Among the largest TF families in humans are homeodomain (HD) (with >200 TFs) and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH, >100 TFs) proteins, which are well known for prominent roles in driving positional identities (e.g. the HOX genes that specify anterior-posterior segmental identity7) and cell type identities8 (e.g. MyoD1 and NeuroD1), respectively. And yet, within each TF family there is extensive similarity of the DNA binding motifs among members. Most bHLH factors recognize a subset of CANNTG sequences collectively called the ‘E-box’9 (each bHLH subfamily prefers a certain variant such as CAgaTG but can often also bind other variants), while the motif TAATT[A/G] is bound by roughly a third of all HD TFs in humans10,11.

Cooperative TF binding is a potential mechanism for achieving DNA-binding specificity among the various TFs of large DBD families and for integration of multiple biological inputs at cis-regulatory elements. Diverse mechanisms underlying TF cooperativity have been described in the literature12. In the simplest and most well-understood mechanism, direct protein-protein contacts mediate stable TF hetero- or homodimer formation in solution, which in turn allows for stronger DNA binding (and regulatory activity) by the resulting TF complex. Another, less specific, mechanism is nucleosome-mediated cooperativity, in which essentially any TFs with binding sites within ~150 bp can indirectly cooperate by competing with the same nucleosome; this type of cooperativity does not require stereotypical spacing or organization of the motifs, sometimes referred to as ‘motif grammar’13. Finally, certain TFs can cooperatively bind juxtaposed DNA sites arranged in specific orientation and distance without forming stable, direct protein-protein interactions; we will refer to this form of co-binding as ‘DNA-guided cooperativity’. In vitro analysis of TF pairs using consecutive affinity-purification systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (CAP-SELEX) revealed that DNA-guided cooperativity may be a common feature of gene regulation14. However, beyond in vitro work, most cellular studies of this mechanism and its biological function have been limited to few well-documented examples, such as the pluripotency factors OCT4 and SOX2, which bind at a composite motif that combines the two TFs’ individual motifs14 to facilitate chromatin opening15,16. In other cases, composite motifs have been observed in DNA sequence analyses of enhancers17–19, but the mechanisms of cooperativity and selectivity among related TFs binding at these sites remain unexplored.

We previously serendipitously discovered a novel, 17-bp long DNA sequence motif with strong evidence of endogenous cellular function, which we termed ‘Coordinator’20. By comparing enhancer landscapes in human and chimpanzee facial progenitor cells called cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) and analyzing the underlying DNA sequence changes, we uncovered motifs whose gains and losses correlated with changes in enhancer activity, as measured by chromatin marks such as histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and DNA accessibility (Figure 1A). The Coordinator motif, discovered through de novo sequence analysis, was far more predictive of active chromatin states and species bias in enhancer activity than any known TF motif20. DNA sequence substitutions between the human and chimp genomes that resulted in gains of fit to the Coordinator consensus motif in either species were associated with gains in enhancer activity in that same species. We therefore hypothesized that the trans-regulatory complex that recognizes the motif plays an outsized role in coordinating enhancer activity in CNCCs, and hence named the motif Coordinator. Although the motif was not previously annotated to a known regulatory complex, it did not escape our attention that parts of Coordinator contain the TAATT[A/G] motif bound by many HD factors and a version of the CANNTG ‘E-box’ motif bound by most bHLH factors, separated by a fixed spacing (Figure 1A). Given the large number of bHLH and HD factors encoded by the human genome6, the Coordinator motif represents a valuable opportunity to gain insight into the mechanisms of specificity and functional implications of TF co-binding in a biologically relevant context.

Figure 1. The ‘Coordinator’ motif is active specifically in embryonic face and limb mesenchyme.

A. Schematic of the ‘Coordinator’ motif and its discovery from studying human and chimpanzee cranial neural crest cell enhancer divergence. B. Rankings of Coordinator and its constituent Ebox/CAGATGG motif in enrichment in the top 10,000 distal accessible regions, for all DNase-seq and ATAC-seq datasets on ENCODE. e1, e2, and n indicate examples of Coordinator-enriched and Coordinator-negative samples, detailed in (C). Points are jittered to avoid overplotting. Zoom-in highlights the prevalence of facial, limb, and fibroblast samples among those with Coordinator motif enrichment (Coordinator rank < 10 and Coordinator rank < E-box rank). C. Examples of Coordinator-enriched and Coordinator-negative samples, with their top 9 motif clusters. Coordinator is highlighted in purple, the best E-box motif match to Coordinator (Ebox/CAGATGG) in blue, and the best homeodomain motif match to Coordinator (HD/2) in red. D. Schematic of cell types and tissues analyzed in (E). E. Coordinator motif enrichment p-value by AME99 (analysis of motif enrichment), with cranial neural crest samples in orange, limb buds in pink, fibroblasts in blue, and neuroblastomas in tan (others in gray).

Here, we sought to systematically identify TFs that bind the Coordinator motif, determine their molecular functions in an endogenous cellular context, and dissect the mechanisms underlying their cooperativity and selectivity. We show that despite the abundance of cell types with high enrichment of the HD and E-box motifs in their active regulatory regions, the Coordinator motif is specific to the developing face and limb mesenchyme. We find that Coordinator is co-bound by a bHLH factor TWIST1, a driver of mesenchymal identity, and by HD TFs associated with defined regional identities in the face and limb, including ALX1, ALX4, MSX1, and PRRX1, all linked to craniofacial, and in some cases also limb, congenital anomalies in humans21–24. Using endogenous degron- and epitope-tagging and nonsense mutations, we studied these TFs’ genomic binding and function in human CNCCs (hCNCCs). We found that TWIST1 is required for accessibility, HD TF binding, and enhancer activity at Coordinator sites. In turn, the HD TFs primarily (and at least in part redundantly) function to stabilize TWIST1 binding at Coordinator sites and to titrate it away from its canonical and HD-independent E-box and double E-box sites towards Coordinator. This co-binding at Coordinator sites drives shared transcriptional functions, with genes associated with lineage and regional identities in the facial mesenchyme showing dependency on both TWIST1 and the ALX factors. TWIST1 and HD TFs do not interact in solution, but instead their cooperativity is guided by the Coordinator motif DNA sequence. We solve a crystal structure of TWIST1, its heterodimerization partner TCF4, and ALX4, bound to the Coordinator DNA, revealing the structural basis of this DNA-guided cooperativity. Finally, we show that genetic variants at loci encoding Coordinator-binding TFs are associated with overlapping aspects of the normal-range facial variation in humans, and that cis-regulatory regions dependent on these TFs are enriched for facial shape heritability. Together, our work illustrates how DNA-guided TF cooperativity can facilitate regulatory specificity and integrate cell lineage and positional information to shape the development and evolution of the face and limb mesenchyme.

Results

The ‘Coordinator’ motif is active specifically in embryonic face and limb mesenchyme

The Coordinator motif20 is a composite of the TAATT[A/G] motif bound by many HD factors and a version of the CANNTG E-box bound by most bHLH factors6, separated by a fixed spacing (Figure 1A). Therefore, we wondered whether any cell types other than CNCCs also exhibit enrichment for the Coordinator motif in their active cis-regulatory regions. We first defined a robust signature of Coordinator activity, based on the observation that in hCNCCs the Coordinator motif is enriched most highly in the top ~10,000 promoter-distal open chromatin peaks as defined by the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) (Figure S1A). We searched for enrichment of known TF motifs in the top 10,000 distal open chromatin regions for each of the 549 ATAC-seq and 1,781 DNase-seq datasets from human and mouse in ENCODE25, and then collapsed similar motifs into 287 motif clusters to remove redundant motifs (Materials and Methods). Finally, we checked the ranking of the Coordinator motif cluster and the motif clusters best matching its constituent motifs, the Ebox/CAGATGG and HD/2 clusters, and considered a sample to exhibit Coordinator activity when: 1) Coordinator is among the top 10 motif clusters, and 2) Coordinator is ranked higher than either constituent motif cluster (Figure 1B,C). This approach can also be applied to other known composite motifs such as the OCT:SOX motif, which meets similar criteria in pluripotent stem cells (Figure S1B). By using only the strongest peaks and motif rankings, this approach should be more robust to variation in sample quality and cellular heterogeneity than approaches using all open chromatin regions or quantitative metrics of motif enrichment.

As expected, the embryonic facial prominence samples, which are largely comprised of CNCCs, exhibit strong Coordinator motif activity, with Coordinator ranked as the second most-enriched motif, after CTCF (Figure 1B,C). However, many developing limb samples and a smaller subset of fibroblast and neuroblastoma samples also meet our definition of Coordinator activity. Notably, neuroblastoma is a cancer originating from neural crest-derived lineages26, whereas fibroblasts are mesenchymal cells of either mesodermal or neural crest origin27. Importantly, across analyzed cell types and tissues, most samples showing strong enrichment of E-box and HD motifs are not enriched for Coordinator (Figure 1B, Figure S1C). For example, many developing brain samples are highly enriched in both E-box and HD halves of the motif but not for the combined motif (Figure 1B,C; Figure S1C). To corroborate this finding, we gathered additional published human and mouse ATAC-seq datasets from cell types related to those in which we initially detected Coordinator enrichment and from relevant negative controls (Figure 1D)28–39. We plotted the p-values of Coordinator motif enrichment and found that in vitro-derived mesenchymal hCNCCs and mouse embryonic facial prominences of CNCC origin have the strongest enrichment, followed closely by limb bud samples, with much lower enrichment in neuroblastomas and fibroblasts (Figure 1E). Altogether, these results indicate that the Coordinator motif is selectively enriched in the accessible cis-regulatory regions of the developing face and limb mesenchyme.

TWIST1 binds Coordinator across tissues with diverse homeodomain TF expression

Due to the discovery of Coordinator from de novo motif analysis and the similarity of binding motifs for TFs among the bHLH and HD families, the identity and number of TFs that bind Coordinator remains unclear. To systematically assess candidate Coordinator-binding TFs, we searched for TFs that have: 1) binding motifs consistent with the constituent E-box or HD halves of Coordinator, and 2) high expression levels specifically in cell types with Coordinator enrichment in open chromatin.

First, we aligned known TF motifs [derived from either chromatin immunoprecipitation DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) data or in vitro specificity measurements using SELEX or protein binding microarrays (PBM), as indicated] against each half of the Coordinator motif, beginning with the E-box typically bound by bHLH factors (Figure 2A; Figure S2A). A total of 54 TFs have motifs that aligned to the E-box, of them 40 in the bHLH family. TWIST1 is the only TF with a known motif that spans both the E-box and the HD motif, though this motif is derived from ChIP-seq in neuroblastoma cells39 and as a bHLH factor, it only directly binds the E-box. In fact, previously published ChIP-seq for TWIST1 overexpressed in human mammary epithelial cells revealed binding to the single or double E-box motifs40. Next, we examined the RNA levels of each candidate TF and their correlation with Coordinator motif enrichment p-values in active regulatory regions across cell types. TWIST1 was the TF with the highest correlation (Figure S2B). Remarkably, its expression levels were nearly perfectly correlated with Coordinator motif enrichment (r = 0.934; Figure S2C). Indeed, our previous work detected Coordinator motif enrichment at TWIST1 ChIP-seq peaks from hCNCCs28. To confirm that TWIST1 binds Coordinator in vivo in cell types with enrichment for Coordinator in active regulatory regions, we performed ChIP-seq for Twist1 in dissected E10.5 mouse embryos (Figure 2B), separately testing the frontonasal prominences (FNP), maxillary prominences (Mx), mandibular prominences (Md), forelimbs (FL), and hindlimbs (HL). We compared these to ChIPs from hCNCCs and previously published data from the neuroblastoma cell lines BE(2)-C and SHEP2139. Across all of these cellular contexts, most of the strongest TWIST1 peaks contained the Coordinator motif, but weaker peaks were progressively less likely to contain the Coordinator motif (using a threshold of p < 10−4). However, compared to the hCNCCs, facial prominences, and limb buds, which sustained high Coordinator motif frequencies (>50%) for the top 20,000 peaks or more, neuroblastomas only had such motif frequencies in the top few thousand peaks (despite a greater total number of peaks). This rapid falloff is consistent with the weaker Coordinator enrichment in neuroblastoma open chromatin (Figure 1E).

Figure 2. TWIST1 binds Coordinator across tissues with diverse homeodomain TF expression.

A. Motif clusters with motifs aligned to the E-box portion of Coordinator (marked by box) with logos and TF names of examples, and the total number of motifs in each cluster (black outline) and the number that successfully aligned to the Coordinator portion (filled in gray, TOMTOM q-value < 0.4). TF name superscript indicates origin of motif: C, ChIP; P, PBM; S, SELEX. B. TWIST1 ChIP-seq analysis in the indicated human cell types and mouse tissues. Schematic of E10.5 mouse embryo illustrates the dissected regions. The strongest TWIST1 peaks and those in cell types with high HD TF activity tend to contain a Coordinator motif (p < 1e-4, within 100 bp of the summit). TWIST1 ChIP-seq peaks are ranked from strongest to weakest (left to right) and grouped into bins of 1000 peaks. C. As in (A), but for the homeodomain (HD) portion of the Coordinator motif. D. HD TF expression varies across cell/tissue types with Coordinator enrichment. RNA expression is shown for all HDs with motifs aligning to Coordinator and appreciable expression in at least one cell type. Colored circles above cell type names correspond to the schematic and lines in (C). E. TWIST1 and multiple HDs are specifically highly expressed in human cranial neural crest cells (hCNCC) but not H9 embryonic stem cells (H9ESC). bHLH and HD family TFs are highlighted in blue and red, respectively (others in gray). TFs with high expression specifically in hCNCC are in darker colors and labeled with their names.

Next, we focused on candidate factors binding the HD portion of Coordinator. Of the 129 TFs with motifs aligned to the HD half of Coordinator, 108 contain an HD DNA-binding domain (Figure 2C; Figure S2D). Of these, 32 are expressed moderately or highly in at least one cell type with Coordinator enrichment (including cranial neural crest, limb buds, and neuroblastomas) (Figure 2D). However, no single clear candidate emerged that was expressed in all Coordinator-positive cell types and could explain the quantitative variation in Coordinator activity. Instead, every cell type expresses multiple HD TFs robustly, with groups of HDs showing overlapping expression in distinct regions of the developing face and limbs, consistent with their previously described association with specific positional identities41–43 (such as along the anterior-posterior axis). For example and as expected, the ALX factors are enriched in the frontonasal prominence, which gives rise to the upper part of the face, whereas DLX factors are enriched in the mandibular prominence, which gives rise to the lower jaw, while the posterior HOX genes are expressed in the limb buds but not the face (Figure 2D). In contrast, neuroblastoma cells express known neuronal/glial regulators PHOX2A/B and ISL1 highly but lack most mesenchymally expressed HD factors.

To test whether these HDs collectively enable TWIST1 binding to Coordinator, we searched the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia44 (CCLE) for any cell lines that have high RNA levels of TWIST1 but minimal levels of these candidate Coordinator-binding HDs (Figure S2E). One of the best matches to our criteria was RS4;11, an acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line with a t(4;11) translocation. We then performed TWIST1 ChIP-seq in RS4;11 cells and found that although TWIST1 binds DNA robustly in RS4;11 cells, those sites are enriched for the single and double E-box motifs (Figure S2F), similar to the motifs bound by TWIST1 upon overexpression in human mammary epithelial cells40. In contrast, the Coordinator motif frequency (< 20%) is around that of the weakest TWIST1 peaks in any context (Figure 2B). These results suggest that TWIST1 binds Coordinator only in cell types in which certain HD proteins are also present.

Multiple homeodomains co-bind Coordinator motif with TWIST1

To study the mechanisms and functional role of TWIST1 cooperation with HD TFs at Coordinator in a biologically relevant context, we turned to our previously characterized in vitro model of human embryonic stem cell (hESC) differentiation to hCNCCs20,28,45,46. TWIST1 is the only bHLH TF selectively expressed in hCNCCs compared to hESCs, whereas the E-proteins TCF3, 4 and 12, which are known to heterodimerize with TWIST1 (and many other bHLH TFs) to bind E-box motifs40,47, are expressed in both cell types, consistent with their broad expression across tissues (Figure 2E). Among the HD TFs, ALX1, ALX4, MSX1, and PRRX1 are most highly and selectively expressed in our hCNCCs, consistent with their closest resemblance to mesenchymal CNCCs of the anterior facial region29 (Figure 2E).

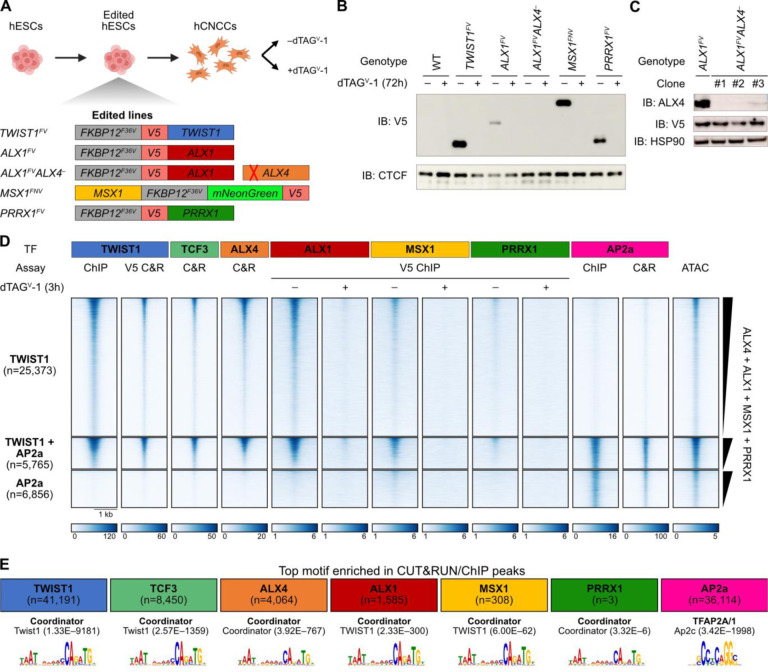

Accordingly, we created a panel of isogenic hESC lines with each TF endogenously and homozygously tagged with the dTAG-inducible FKBP12F36V degron48,49, a V5 epitope tag, and in one case also the fluorophore mNeonGreen50, which we could then differentiate to hCNCCs in vitro51 (Figure 3A). This approach allows for acute or long-term depletion of each TF (Figure 3B) and—through the addition of a common V5 tag—for comparative studies of TF levels and DNA binding. Using CRISPR/Cas9 with adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated delivery of homology-directed repair template52, we successfully tagged TWIST1, ALX1, MSX1, and PRRX1 and confirmed that we could induce near-complete depletion by adding dTAGV-1 molecule to the media (Figure 3B; Figure S3A). The aforementioned tagging strategy did not significantly disrupt baseline TF levels; for TWIST1 and MSX1, protein levels actually increased upon tagging (Figure S3B). Based on previous studies42,53, we suspected ALX1 and ALX4 might have overlapping functions, so we generated multiple independent clonal lines with nonsense mutations in ALX4 on top of the ALX1FV tagged background, as we were unable to degron-tag ALX4 (Figure 3C; Figure S3C).

Figure 3. Multiple homeodomains co-bind Coordinator motif with TWIST1.

A. Schematic of endogenous tagging TFs with the FKBP12F36V degron and V5 epitope tag in human embryonic stem cells (hESC) followed by differentiation into cranial neural crest cells (hCNCC) and treatment with or without dTAGV-1. The ALX4 gene was instead knocked out by a frameshift mutation. B. Confirmation of TF tagging and depletion upon dTAGV-1 addition by Western blot for V5 epitope, with CTCF as a loading control. IB, immunoblot. C. Confirmation of ALX4 knockout in three independent clones by Western blot, with HSP90 as a loading control. D. Homeodomain TFs bind DNA at TWIST1-bound sites at variable occupancies. Heatmap shows promoter-distal binding sites for TWIST1 and/or AP2a. Assay indicates whether data shown is from ChIP, CUT&RUN (C&R), or ATAC, and whether an endogenous or V5 antibody was used. Rows are ranked by the sum of the homeodomain signals from undepleted cells. In the scale bar, units are reads per genome coverage, except for ATAC data, which is in signal per million reads. E. Homeodomain TFs bind the Coordinator motif. The top enriched motif (by AME) is shown for each TF, with p-values in parentheses.

Having developed these resources, we performed ChIP-seq and CUT&RUN to assess DNA binding profiles of these tagged TFs, plus ALX4, TCF3 (a heterodimerization partner of TWIST1), and the positive control AP2a (encoded by TFAP2A, a key neural crest TF45) using endogenous antibodies. We first used binding sites for TWIST1 and AP2a as reference points, grouping the distal regulatory regions into those bound by TWIST1 or AP2a only (Figure 3D, top and bottom heatmaps, respectively) or those co-bound by both (Figure 3D, middle heatmaps). As expected, binding of the TWIST1 heterodimerization partner TCF3 is correlated with that of TWIST1. For all four tested HD TFs, DNA binding at TWIST1 sites clearly exceeds that at AP2a-only sites despite comparable accessibility with TWIST1-only sites. The ChIP signal is minimal upon dTAGV-1 addition, underscoring the specificity of the V5 ChIPs. However, the strength of ChIP signal is reproducibly distinct between the tagged HD TFs, with strongest signal for ALX1, intermediate signal for MSX1, and only weak signal for PRRX1. We note that this ranking is not concordant with that of the TF protein levels by Western blot for the shared V5 epitope, as ALX1 has the lowest relative abundance but strongest binding (Figure 3B). ALX4 shows similar binding patterns as well, though we could not directly compare its chromatin occupancy level with that of other HDs, as in the absence of tags, we had to use an endogenous ALX4 antibody for the analysis.

As an orthogonal approach, we called peaks for each TF (using the depleted samples as negative controls when available) and searched for enrichment of known motifs (as before, clustering similar motifs) compared to shuffled controls (Figure 3E). The top motif cluster for TWIST1, TCF3, and all tested HD TFs is Coordinator, confirming that these HD TFs predominantly bind DNA with TWIST1. Together these data indicate that TWIST1 can bind Coordinator sites with multiple HD TFs including ALX4, ALX1, MSX1, and PRRX1, albeit at varying occupancies.

TWIST1 facilitates homeodomain TF binding, chromatin opening, and enhancer activity

To investigate the mechanism and function of TF cooperation at Coordinator, we studied how depletion of each Coordinator-binding TF impacts chromatin states and the binding of other TFs. We first focused on TWIST1, given its central role as the key bHLH factor binding Coordinator across cellular contexts. We began with acute depletions ranging from 1 hour to 24 hours in hCNCCs, and performed ChIP-seq to measure TWIST1 binding, CUT&RUN for ALX4 binding (with an endogenous antibody), ATAC-seq to measure chromatin accessibility, and ChIP-seq for H3K27ac as a mark correlated with enhancer/promoter activity (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. TWIST1 opens chromatin for homeodomain TFs and enhancer acetylation.

A. Schematic of acute depletion experiments and follow-up assays. B. Heatmap of Coordinator motif enrichment, TF binding, chromatin accessibility (ATAC), and H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac) at distal enhancers grouped by their change in accessibility upon TWIST1 depletion. In the scale bar, units are reads per genome coverage, except for the Coordinator motif, which is in log10 p-value, and ATAC data, which is in signal per million reads. One representative replicate of two independent differentiations is shown. C. Browser tracks of example enhancers with loss, no change, or gain of accessibility upon TWIST1 depletion. Coordinates in hg38: Loss, chr17:70,668,899–70,678,127; No change, chr11:44,958,683–44,968,011; Gain, chr2:172,058,768–172,068,096. D. Top three motif clusters enriched in enhancers with loss or gain of accessibility upon TWIST1 depletion compared to those with no change (by AME, analysis of motif enrichment) with their p-values.

TWIST1 depletion rapidly reshapes the chromatin landscape, with 36,290 regions losing accessibility and 17,054 regions gaining accessibility within 3 h (Figure S4A). The change in accessibility is mostly complete within 3 h (Figure S4B), so we combined the 3 h and 24 h differentially accessible peaks to define a set of sites with loss vs. gain of accessibility. Among candidate enhancers (promoter-distal peaks with robust H3K27ac signal), 11,186 sites lose accessibility, 4,042 sites gain accessibility, and 4,732 do not significantly change (Figure 4B, example browser tracks shown in Figure 4C). Regions losing accessibility are highly enriched for the Coordinator motif and TWIST1 binding, whereas those gaining accessibility lack TWIST1 binding and are most enriched for AP2a and NR2F1 motifs, suggesting these effects are indirect (Figure 4B–D). Changes in accessibility are correlated with changes in H3K27ac (Figure 4B, Figure S4C, r = 0.834 for 3 h, 0.896 for 24 h). In particular, loss of TWIST1 leads to a substantial depletion of H3K27ac within hours, consistent with an activating role of TWIST1 at cis-regulatory elements (Figure S4D). Furthermore, TWIST1 depletion eliminates enhancer reporter activity of a well-characterized SOX9 enhancer dependent on the Coordinator motif28, confirming that TWIST1 is required for bona fide enhancer activity (Figure S4E). Importantly, TWIST1 depletion largely abrogates DNA binding of ALX4 at Coordinator sites in just 1 h (Figure 4B,C; Figure S4D). Therefore, both HD factor binding and open/active chromatin states of cis-regulatory elements are dependent on TWIST1, consistent with our original hypothesis based on evolutionary comparisons that the trans-regulatory protein or complex recognizing Coordinator may play a large role in ‘coordinating’ enhancer activity in CNCCs20.

Homeodomain TFs cooperate with TWIST1 to open chromatin at Coordinator sites

We next asked how the depletion of HD TFs affects open chromatin landscapes and TWIST1 binding at Coordinator. Given that for ALX4 we were only able to generate a constitutive knockout, to obtain comparable data across all TF perturbations, we performed differentiations of ALX4− hESCs along with the ALX1, MSX1, PRRX1, and TWIST1 degron-tagged hESCs, in which we treated cells with dTAGV-1 from the beginning of differentiations to mimic a knockout. We harvested these cells for ATAC-seq and RNA-seq at an early hCNCC stage, to minimize indirect effects. Even in these long-term depletions, many of the observed effects are likely directly caused by HD dysfunction in mesenchymal CNCCs, as most of the aforementioned HD TFs are only expressed in CNCCs following their specification and delamination42,54 (with an exception of MSX1, which is expressed in the neural plate border precursor to CNCCs55). Supporting this idea, accessibility effects of the long-term TWIST1 depletion are well-correlated with the acute 24 h depletion (r = 0.664; Figure S5A).

Consistent with the range in strength of DNA binding among HDs (Figure 3D), ALX1 depletion results in significant changes in accessibility at 6,195 peaks (FDR < 0.05), while ALX4 knockout causes changes at 4,284 peaks, MSX1 at 1,410 peaks, and the weakest binder, PRRX1, at none (Figure S5B). In general, all HD TF depletions have much weaker effects on accessibility than TWIST1 depletion, likely due to functional redundancy among them. Indeed, changes upon ALX1 and ALX4 losses are well-correlated (r = 0.651) (Figure 5A). These are also correlated, albeit less well, with effects of MSX1 loss (r = 0.462) (Figure S5C). Next, by comparing the undepleted ALX1FV samples (in which both ALX1 and ALX4 are present) to the depleted ALX1FV ALX4− samples (in which both are lost), we inferred the effect of combined ALX1 and ALX4 loss on the ATAC-seq changes at the corresponding set of genomic targets. This comparison allowed detection of differential accessibility at a greater number of peaks (8,577), but with similar or slightly larger effect sizes than individual ALX1 or ALX4 loss (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Homeodomain TFs stabilize TWIST1 binding at Coordinator sites.

A. Correlation in Log2 fold change (FC) in accessibility upon loss of ALX1 (by long-term dTAGV-1 treatment) versus ALX4 (by knockout). All distal accessible regions with a significant change upon loss of any tested TF (ALX1, ALX4, MSX1, or TWIST1) are shown. Red line indicates y = x. B. Observed change in accessibility upon loss of both ALX1 and ALX4 is similar to the expectation based on the log sum of their individual effects. C. Most chromatin accessibility effects of ALX loss (ALX1 and/or ALX4) are concordant with (but are a subset of) those of TWIST1 loss. NS, not significant. D. Peaks with down-regulation of accessibility upon TWIST1 and ALX loss are enriched in the Coordinator motif (left), while those that decrease upon TWIST1 loss but increase upon ALX loss are enriched in the double E-box motif (right). E and F. TWIST1 binding by ChIP-seq quantitatively shifts from Coordinator to double E-box motif sites upon loss of ALX4 (without ALX1 depletion) in hCNCCs (E) or overexpression of TWIST1 alone rather than with ALX4 in HEK293 cells (F). G through I. Volcano plots of differential gene expression upon loss of TWIST1 (G), ALX1 (H), or ALX1 and ALX4 (I). ALX4 is excluded in (I). Upregulated genes are red and downregulated genes are in blue, with selected genes highlighted in darker colors.

We next asked how similar the effects of ALX loss on chromatin accessibility are to those of TWIST1 loss. Given the correlated effects of ALX1 and ALX4 loss (Figure 5A,B), we considered their combined effects, taking any ATAC-seq peak significantly affected by loss of ALX1, ALX4, or combined loss of both. As there are many more TWIST1-dependent peaks, most of these are not dependent on ALXs. However, of distal peaks downregulated upon ALX loss, the vast majority (5,543/7,931 = 70%) are concordant, or also downregulated upon TWIST1 loss, while few (449/7,931 = 5.7%) are discordant, or upregulated upon TWIST1 loss but downregulated upon ALX loss (Figure 5C). Distal peaks upregulated upon ALX loss lack this enrichment for concordance with TWIST1 effects, but these represent a minority (32%) of changes. The effects of MSX1 loss are also concordant with TWIST1 loss (Figure S5E). To find the DNA sequence features driving these concordant and discordant changes, we performed motif enrichment analyses on these different classes of accessible peaks. We found that the Coordinator motif is highly enriched in the TWIST1- and ALX-dependent peaks, underscoring that the main function of ALX1 and ALX4 in chromatin opening is indeed at Coordinator sites (Figure 5D). Of note, for the TFs that were degron-tagged, we also repeated the chromatin accessibility analysis upon acute loss of each TF, and observed minimal changes except for TWIST1 (Figure S5D) suggesting that, in contrast to TWIST1, the HD TFs are more important for establishing the chromatin landscape at Coordinator sites rather than for maintaining it after it has been established.

Loss of homeodomain TFs titrates TWIST1 away from Coordinator towards the canonical double E-box sites

In addition to Coordinator, other motifs provide insight into the mechanisms underlying TWIST1-HD cooperation (Figure 5D; Figure S5F). In particular, the dominant feature of peaks that gain accessibility upon ALX loss but lose accessibility upon TWIST1 loss is the double E-box motif, which contains two Ebox motifs at a 5 bp spacing. The double E-box motif has previously been proposed to bind two copies of TWIST1:TCF3 heterodimers40 and we found it highly enriched in the top TWIST1 binding sites in the HD-negative RS4;11 cells (Figure 5D; Figure S2E). Thus, ALX loss appears to quantitatively redirect TWIST1 or its chromatin opening capacity away from Coordinator sites and towards double E-box sites.

To substantiate this observation and determine whether the distribution of TWIST1 binding at Coordinator vs double E-box sites is affected by the ALX loss, we performed TWIST1 ChIP-seq in ALX1FV ALX4- hCNCCs (without ALX1 depletion) and compared the binding to that of WT cells (Figure 5E). TWIST1 binding signal is reduced at sites with the Coordinator motif but increases at sites with the double E-box motif. These changes are quantitative rather than qualitative, potentially due to the overlapping and partially redundant functions of HD TFs, which may retain some TWIST1 at Coordinator even in the absence of ALX4. To confirm this finding in a cellular context without redundancy, we overexpressed TWIST1 with or without ALX4 in HEK293 cells (which lack appreciable expression of TWIST1 or most HD TFs) and then performed TWIST1 ChIP-seq. As we saw in hCNCCs but to a greater extent in this overexpression context, TWIST1 binding to the Coordinator motif decreased in the absence of ALX4, whereas binding to the double E-box motif increased (Figure 5F).

Shared transcriptional functions of TWIST1 and ALX factors

To assess the transcriptional functions of TWIST1 and HD factors in our in vitro hCNCC differentiation model, we used RNA-seq to identify genes significantly affected by the pertubation of TWIST1, ALX1, or both ALX1/4 (Figure 5G–I). Consistent with previous mouse studies56,57, the most significant effect of TWIST1 loss in our hCNCCs is an increase in SOX10 expression (Figure 5G). SOX10 is an early CNCC regulator that becomes selectively downregulated as CNCC become biased toward mesenchymal rather than neuroglial lineages57,58. FOXD3, another early neural crest specifier gene59,60 whose expression decreases in post-migratory CNCCs42,54, is also highly upregulated upon loss of TWIST1, as are neural progenitor markers SOX2/3 and the neuronal marker TUBB3, suggesting a defect in mesenchymal specification. Meanwhile, the loss of ALXs (which are expressed primarily in the anterior-most CNCC forming the frontonasal prominences) leads to upregulation of TF genes normally expressed only in more posterior parts of the face, such as DLX1, DLX2, LHX6, LHX8, and BARX1, and to downregulation of TF genes normally most abundant in the anterior-most regions of the face, such as PAX3, TFAP2B, and ALX4 (the latter upon ALX1 depletion) (Figure 5H,I). This suggests that HD TFs associated with anterior facial identity (namely ALXs) promote expression of genes associated with this identity, while repressing expression of those associated with alternative, more posterior facial identities, as seen in a recent Alx1-null mouse42.

Notably, there is a substantial overlap between TWIST1- and ALX-responsive genes, with a subset of position-specific genes (DLX1/2, PAX3, TFAP2B) being regulated by TWIST1 as well as ALXs (Figure 5G–I). Furthermore, MSX1, a gene encoding HD TF broadly expressed throughout the face and limb buds and associated with mesenchymal cell identity61, is downregulated upon loss of ALXs as well as TWIST1. This overlap is representative of overall concordance between TWIST1 and ALX transcriptional changes: genes downregulated upon ALX loss are enriched for downregulation upon TWIST1 loss as well, in both long-term and acute depletions (Figure S5G). Note that MSX1 loss affects mesenchymal specification, with upregulation of neural progenitor markers SOX2 and SOX3 as seen with TWIST1 loss (Figure S5H), but generally has fewer effects than loss of ALXs, so shared activation of MSX1 cannot explain most of the overlap in ALX and TWIST1 functions. These results suggest that TWIST1 and HD TFs co-binding at Coordinator sites drives shared transcriptional functions and may serve to integrate regulatory programs for lineage and regional identities during facial development.

The Coordinator motif guides contact and cooperativity between TWIST1 and HD TFs

We next investigated biochemical and structural mechanisms underlying cooperative co-binding of TWIST1 and HD factors at Coordinator sites. We first considered cooperativity mediated by protein-protein interaction between TWIST1 and HD proteins. We used immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (IP-MS) to systematically identify proteins that interact with TWIST1 in hCNCCs, using a chromatin extraction protocol that minimizes the extraction of DNA (Figure 6A and Table S3). Consistent with previously published results, we find that TWIST1 forms stable heterodimers with its E-protein partners TCF3, TCF4, and TCF1240,47,62. However, TWIST1 lacks interactions with ALXs or other HD TFs, and this was confirmed by the reciprocal IP-MS experiments pulling down the HD TFs (Figure S6A and Table S3).

Figure 6. The Coordinator motif guides TWIST1-homeodomain contact and cooperativity.

A. Immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (IP-MS) for TWIST1 using the V5 tag, in undepleted (-dTAG, y-axis) versus depleted (+dTAG, x-axis) hCNCC protein extracts. Plotted data are the sum of two biological replicates. B. 3D structure of TWIST1 (aa101–170), TCF4 (aa565–624), and ALX4 (aa210–277) bound to the Coordinator DNA sequence. DNA bases recognized by the TFs are highlighted in their respective colors: cyan for TWIST1, green for TCF4, and magenta for ALX4. C. Zoomed-in view of the contact between ALX4 residue His237 and TWIST1 residue Pro139. D. Sequence alignment of selected homeodomain TF loop sequences (left) with the TWIST1 contact residue highlighted in cyan, and structural alignment of ALX4 (magenta with red loop) with MSX1 (PDB: 1IG7) in gold, and DLX3 (PDB: 4XRS) in beige (right). E. Homeodomains shift TWIST1 toward Coordinator to varying degrees. Indicated Flag-tagged HD proteins were co-expressed with TWIST1 in HEK293 cells and TWIST1 binding was measured by ChIP-seq (see Figure S6B for protein levels). TWIST1 ChIP-seq peaks are ranked from strongest to weakest (left to right) and grouped into bins of 1000 peaks. F. Sequence alignment of TWIST1 and NEUROD1 loops (left), and structural alignment of TWIST1 (cyan with purple loop) with NEUROD1 (PDB: 2QL2) in green (right). G. TWIST1 loop is required for Coordinator binding. V5-tagged TWIST1, NEUROD1 or TWIST1 with NEUROD1 loop were expressed in HEK293 with or without ALX4 (see Figure S6C for protein levels). ChIP-seq peaks are ranked from strongest to weakest (left to right) and grouped into bins of 1000 peaks.

This observation suggested that cooperativity between TWIST1 and ALX proteins may be guided by the Coordinator motif DNA sequence. To explore this possibility, we solved an X-ray crystal structure of TWIST1, TCF4, and ALX4 DNA-binding domains co-bound to the consensus Coordinator motif, at 2.9Å resolution (Figure 6B). As expected, each TF is bound to its canonical motif, with a TWIST1-TCF4 heterodimer bound to the E-box and ALX4 bound to the HD monomer motif within Coordinator. Within the bHLH dimer, TWIST1 binds the side of the E-box motif further from the HD motif, allowing its loop to contact ALX4 (Figure 6C). The direct contact interface between the TWIST1 and ALX4 loops is one amino acid on each protein, with TWIST1 proline 139 interacting with ALX4 histidine 237. This lack of an extensive protein-protein binding interface is consistent with the absence of strong interactions in solution detectable by IP-MS, and further supports DNA-guided cooperativity between TWIST1 and ALX4.

The amino acid residues, and more broadly the loops, involved in the TWIST1-HD contact are not invariant in amino-acid sequence, even among TFs with highly similar DNA binding motifs (Figure 6D,F). To assess whether these variable loops form distinct structures, we aligned our TWIST1-TCF4-ALX4-Coordinator structure to previously solved (individual) HD and bHLH structures. Despite amino acid differences at the contact residue position (i.e. His to Gln substitution), MSX1 (PDB: 1IG7) and DLX3 (PDB: 4XRS) both form highly similar structures as ALX4 (Figure 6D). While the amino acid identity could impact the affinity of the contact, this result is consistent with our ChIP data suggesting that MSX1 and PRRX1 can also bind DNA at many of the same sites as ALX1/4 in hCNCCs, albeit at much reduced occupancies compared to the ALX factors (Figure 3D). To further test if these additional HD TFs can indeed direct TWIST1 binding towards Coordinator, we transfected plasmids encoding TWIST1 with one of ALX4, MSX1, PRRX1 (both major splice isoforms), or PHOX2A into HEK293 cells and performed TWIST1 ChIP-seq. All tested HD TFs are capable of increasing TWIST1 binding to the Coordinator motif, but none are as potent as ALX4 (Figure 6E), despite being expressed at comparable or higher protein levels (Figure S6B).

Among bHLH factors, neurogenic factors such as NEUROD1 stand out as having some of the most similar E-box DNA binding motifs to TWIST1 (Figure S2A). Yet, the NEUROD1 loop sequence and structure differ substantially from that of TWIST1 (Figure 6F). We reasoned that if, as our structure suggests, the loop contact plays a key role in Coordinator-guided cooperativity between bHLH and HD, then NEUROD1 itself or TWIST1 in which the ALX4-contacting loop has been replaced with the corresponding NEUROD1 loop may not be able to bind Coordinator in the presence of HD TFs. To test this, we transfected HEK293 cells with cDNAs encoding V5-tagged TWIST1, NEUROD1, or TWIST1 with a NEUROD1 loop, each with or without ALX4, ensuring that bHLH protein levels were comparable across samples (Figure S6C). We then performed ChIP-seq for the V5 tag. All three bHLH proteins are capable of binding chromatin at their known E-box motif (Figure S6D,E). Furthermore, as we have seen with an endogenous TWIST1 antibody, TWIST1 binds the Coordinator motif robustly only in the presence of ALX4. However, neither full length NEUROD1 nor TWIST1 with the NEUROD1 loop bind Coordinator appreciably even in the presence of ALX4 (Figure 6G). Collectively, these results illustrate how the Coordinator motif guides cooperative binding of TWIST1 and HD TFs, in a manner dependent on the features of the TWIST1 loop.

The roles of Coordinator-binding TFs in facial shape variation

We initially identified Coordinator motif through the analysis of enhancer divergence between human and chimpanzee cranial neural crest (Figure 1A)20. As we have now uncovered the trans-regulatory complex that binds Coordinator, we aimed to assess the potential impacts of the identified TFs and their genomic targets on human phenotypic variation. Our previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) uncovered over 200 loci associated with normal-range variation in facial shape among individuals of European ancestry and revealed enrichment of face shape-associated genetic variants in CNCC enhancers63. To assess the contribution of Coordinator-binding TFs to human facial variation, we used two orthogonal approaches. In the first approach, we focused on enrichment of facial shape heritability at genomic targets regulated by Coordinator-binding TFs. In the second approach, we investigated the phenotypic impact of genetic variants at the loci encoding Coordinator-binding TFs themselves.

To assess contributions of specific sets of genomic regions responsive to TF losses, we used linkage disequilibrium score regression (S-LDSC) to determine the heritability enrichment of each set of regions compared to: (i) an accessibility-matched control set of hCNCC distal ATAC peaks (control) or (ii) the entire set of hCNCC distal ATAC peaks (all peaks) (Figure 7A). We first tested the set of distal regions differentially accessible within 3 h of acute TWIST1 depletion, separately assessing the up- and downregulated peaks. The downregulated peaks are 25.6-fold enriched over the genome, in contrast to 2.44-fold enrichment in the control peaks (p = 2.47E-6, downregulated vs matched control peaks, t-test) and 9.35-fold enrichment across all peaks (p = 6.63E-5, downregulated vs all peaks, t-test). In contrast, the upregulated peaks have a lower enrichment than either the matched or full control sets (1.78-fold vs 7.72-fold and 9.35-fold). We observed similar results for the peaks differentially accessible upon longterm TWIST1 loss. Despite lower statistical power due to the smaller number of regions, we nevertheless detected significant enrichment in peaks downregulated upon ALX1+ALX4 loss compared to all hCNCC ATAC peaks (p = 0.0395, t-test). As a negative control, we analyzed the same genomic regions for enrichment of an unrelated trait, height. Height does not show the same pattern of enrichment in downregulated peaks even though height GWAS signal is enriched in hCNCC distal ATAC peaks overall, likely due to shared programs for skeletal development being involved in both traits (Figure S7A). These results indicate that genetic variation in the Coordinator-containing regions whose accessibility are regulated by TWIST1, ALX1, and ALX4 ultimately modulates human facial shape.

Figure 7. The roles of Coordinator-binding TFs in facial shape variation.

A. Facial shape heritability enrichment at TWIST1- and ALX-dependent regulatory regions. Fold enrichment of facial shape-associated SNPs in distal ATAC peaks differentially accessible upon TF depletion or loss, with accessibility-matched control sets. Vertical line indicates the enrichment in all hCNCC distal ATAC peaks, with flanking dashed lines indicating error bars. Error bars represent s.e.m. B. Facial shape effects associated with genetic variants at loci encoding Coordinator-binding TFs. Facial shape effects of each lead SNP near Coordinator-binding TF genes, shown as normal displacement (displacement in the direction normal to the facial surface) for the facial region with highest significance for each SNP. Red colored areas shift outward and blue colored areas shift inward. C. Model of how DNA-guided cooperativity confers specificity among cellular contexts. The developing brain lacks TWIST1 and instead expresses neurogenic bHLH TFs like NEUROD1 which bind E-box motifs but cannot cooperate with co-expressed HDs. Different face and limb regions express TWIST1 with different HD partners capable of cooperativity at Coordinator motif. Lymphoblastic leukemia cells express TWIST1 but lack HD partners, so TWIST1 binds double E-box motif instead.

The analysis of facial shape GWAS signals revealed that loci encoding each of the Coordinator-binding TFs analyzed in this study (i.e. TWIST1, ALX1, ALX4, MSX1, and PRRX1) have at least one facial shape-associated SNP in the non-coding region nearby, enabling us to examine the effect of modulating TF expression on human facial shape (Figure 7B; Figure S7B). The multivariate analytic approach of the facial shape GWAS allows for assessment of both global and local effects of genetic variants on facial shape by quantifying these effects and their significance over segments corresponding to distinct facial regions (Figure S7B)63,64. Facial effects can also be visualized by showing shape displacement associated with the minor vs major allele of a given genetic variant. When such analysis was performed for facial GWAS SNPs at Coordinator-binding TF loci, we observed that variants at the TWIST1, ALX1, and ALX4 loci have broad and overlapping effects on facial shape, with the most significant effects spanning the entire face (Figure 7B; Figure S7B). In contrast, the SNPs at the MSX1 and PRRX1 loci have more localized effects near the mouth, which may be indicative of association with the maxilla shape. Our observations indicate that all loci encoding TF components of the Coordinator trans-regulatory complex are implicated in human facial variation. Furthermore, SNPs at the loci encoding TFs with the strongest regulatory input into Coordinator function (i.e. TWIST1 and ALX factors) show the most broad-ranging facial effects. Together, these observations link Coordinator-binding TFs and their genomic targets to human phenotypic variation (Figure 7C).

Discussion

Our work demonstrates how a composite TF motif called Coordinator guides selective co-binding by bHLH and HD factors (Figure 7C), thereby integrating established functions of these TFs in defining cell type56,57,65 (TWIST1) and positional7,42,66 (HDs) identities in the developing face and limb mesenchyme. Our study has important implications for evolution and variation of these mesenchymal structures and illustrates how DNA-guided cooperativity can facilitate increased regulatory specificity and selective functional interactions between TFs in the absence of stable protein complex formation in solution. Thus, the Coordinator motif and its trans-regulatory complex provide a novel paradigm for dissecting the mechanisms and implications of DNA-guided TF cooperativity in cellular contexts, which remains poorly understood beyond the extensively studied OCT4-SOX2 example.

Coordinator motif and its binding factors in development, evolution, and disease

Although we first discovered the Coordinator motif through comparisons of human and chimpanzee CNCCs20, we now show that Coordinator is not restricted to primates nor the developing face. Instead, across cell types, Coordinator is selectively enriched at the cis-regulatory regions of the undifferentiated mesenchymal cells from both face and limb buds, which have distinct embryonic origins (neural crest vs mesoderm, respectively) but share expression of many key TFs. Across species, we detected Coordinator enrichment in mouse and chick limb bud mesenchyme (Figure S1D)67, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role in vertebrates. Furthermore, the TFs that bind Coordinator (as well as their face and limb expression patterns) are also conserved among vertebrates68–70. Thus, the Coordinator motif appears to be one of the key unique cis-regulatory features of the vertebrate embryonic mesenchyme.

The TFs binding Coordinator have well-documented roles in the development of the face and limbs, as shown both in mouse models and revealed by human genetics. For example, mouse knockouts of Twist156,71, Alx142, and Alx4 (in combination with mutations of Alx1 or Alx3)42,72 all have strong craniofacial phenotypes that most profoundly manifest in the anterior facial regions, which interestingly, also coincides with the strongest enrichment of the Coordinator in the frontonasal prominence (FNP), as compared to other facial prominences. Similarly, Twist173, Alx74, Msx61,75, and Prrx76,77 factors are involved in limb development in the mouse, where analogous to craniofacial regions, Alx4 marks the anterior-most region of the limb bud78, while Msx and Prrx factors are more widely expressed. In humans, mutations in TWIST1 are associated with the Saethre-Chotzen and Sweeney-Cox syndromes, characterized by facial dysmorphisms, craniosynostosis, and limb malformations79,80, mutations in genes encoding ALX TFs cause frontonasal dysplasias22,23,81,82, and mutations in PRRX1 are associated with agnathia-otocephaly complex (absence of mandible)24. Furthermore, our combined observations that: (i) genetic variants at the loci encoding Coordinator-binding TFs are associated with normal-range facial variation in humans, (ii) genomic targets regulated by these TFs are enriched for facial shape heritability, and (iii) Coordinator sequence mutations drive divergence in CNCC enhancer activity between human and chimp, altogether suggest that cis-regulatory mutations that affect Coordinator motif or expression level of its associated TFs play an important role in mediating inter- and intra-species phenotypic divergence in face shape. This role in phenotypic variation is likely not restricted to humans or primates. For example, genetic variants in the ALX1 locus seem to have contributed to beak shape evolution in Darwin’s finches83, while a bat PRRX1 enhancer contributed to its elongated forelimbs84.

Coordinating cell type and positional identities

Embryonic development requires placement of the right cell types in the right places. Coordinator-guided cooperativity between TWIST1, a well-known regulator of mesenchymal lineage, and HDs, many of which have been implicated in establishing or maintaining positional identity (such as along anterior-posterior or proximal-distal axes), may serve to coordinate cell type and positional information in the embryonic mesenchyme. TWIST1 is broadly expressed across the undifferentiated mesenchyme of the face and limb buds, where it has been shown to promote mesenchymal identity56,57,71, and prevent premature chondrogenic or osteogenic differentiation85,86. The central role of TWIST1 in mesenchymal potential of the cranial neural crest is underscored by the recent observations that overexpression of TWIST1 is sufficient to endow trunk neural crest with the ability to form mesenchymal derivatives58, and to reprogram Ciona pigment cells into cells resembling the ectomesenchyme in vertebrates87. Beyond the face and limbs, TWIST1 functions in other processes associated with the acquisition of mesenchymal identity, such as during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in metastasizing cancer cells65, and gastrulation and mesoderm development in Drosophila88,89. However, across these diverse biological contexts, TWIST1 has been shown to bind canonical solo and double E-box motifs40,90. Thus, TWIST1 performs distinct cellular and organismal functions, perhaps through a range of molecular mechanisms, with Coordinator-guided cooperativity with HD TFs enabling functions specific to face and limb development.

In contrast to the broad expression of TWIST1 across the developing mesenchyme, expression of HD TFs is more regionally restricted (Figure 2D; Figure 7C). Notably, most of the face is devoid of canonical HOX gene expression. Instead, ALX and DLX family HD TFs are expressed in position-restricted patterns and involved in development and patterning of the anterior and posterior facial structures, respectively43,91. ALX or DLX TF expression often coincides with that of MSX and PRRX TFs, which are more broadly transcribed throughout the developing face91. Our results indicate that multiple co-expressed HD TFs are capable of co-binding with TWIST1 at the Coordinator sites, albeit at varying occupancies, with the ALX TFs showing the strongest binding (Figure 3D, Figure 6E). Furthermore, the observation that Coordinator enrichment and TWIST1 binding at Coordinator sites are detectable in regulatory regions of mandibular prominence, which preferentially expresses DLX factors but lacks ALXs (Figure 1D, 2D), combined with the structural similarity of the DLX3 homeodomain helix 1-helix 2 loop with that of ALX4 (Figure 6D), suggest that in the developing jaw mesenchyme, TWIST1 likely also cooperates with the DLX proteins. However, our data hint that the strength of Coordinator binding may contribute to the incipient divergence of facial regions, as the anterior-most FNP exhibits the highest Coordinator motif enrichment among TWIST1 binding sites, while the mandibular prominence exhibits reduced enrichment (Figure 2B). Together with our observation that ALXs have the strongest cooperation with TWIST1 (Figure 6E), this may explain the prior observation that a conditional knockout of TWIST1 in the neural crest leads to the most dramatic phenotype (a near-complete loss) in the upper face derived from the FNP and maxillary prominences, while the mandible is less affected56. Interestingly, loss of either TWIST1 or ALX TFs in our CNCC model results in the upregulation of DLX1 and DLX2 mRNAs (Figure 5G–I). This suggests that once positional identity of the facial region is established, it is reinforced by the cooperative function of TWIST1 and ALXs at the expense of the alternative, more posterior identity, mediated by the DLX factors.

Specificity of DNA-guided cooperativity among bHLH and HD TFs

Cooperation at Coordinator is remarkably selective among cell types and TFs, akin to the OCT4-SOX2 motif defining pluripotent stem cells. Even TFs with highly similar individual TF motifs that are coexpressed with some of the same candidate partner TFs are unable to cooperate: NEUROD1 cannot cooperate with ALX4 (Figure 6G), and in the developing forebrain, the abundant DLX factors do not bind Coordinator despite nearby enrichment of neurogenic bHLH TF motifs (Table S1)92. Nevertheless, in vitro, other bHLH-HD TF pairs can co-bind composite motifs by CAP-SELEX14, so while Coordinator itself has not been seen in other cellular contexts, other TF pairs may be capable of co-binding distinct composite motifs with heretofore unexplored biological functions.

Cooperative potential is quantitative rather than binary—while many HDs can direct TWIST1 to Coordinator, they do so at lower efficiency than ALX4 (Figure 6E). This may explain why even though neuroblastomas exhibit high expression of PHOX2A/B, which can direct TWIST1 to Coordinator (Figure 6E), TWIST1 does not bind Coordinator very robustly in neuroblastomas (Figure 2B). ALXs appear particularly dependent on TWIST1 for their chromatin occupancy, with binding sites overwhelmingly enriched for Coordinator motifs rather than independent HD monomer or dimer motifs (Figure 3E), but other TFs may bind mostly at independent sites. Whether a given pair of TFs will preferentially bind at composite, cooperative sites versus their canonical monomeric or dimeric sites may depend not only on the strength of co-binding between the two partners, but also on the milieu of other TFs capable of functional (direct or indirect) interactions with one (or both) of the cooperating TFs. For example, for bHLH and HD these functional interactions may include their heterodimerization partners, such as E-proteins and TALE-type HD TFs93, respectively.

We find through structure and mutagenesis studies that a fairly weak contact between flexible loops can stabilize cooperative binding by TWIST1 and ALX4 at Coordinator sites (Figure 6, Figure 7C). The weak interaction between the loops is guided by the DNA, as we do not detect association between TWIST1 and ALX TFs in solution, even though robust binding between TWIST1 and its E-protein partners is seen under the same conditions (Figure 6A). The weakness and flexibility of the inter-loop contact may make it more easily modulated during evolution, and indeed the loop residues are variable among closely related bHLH and HD TFs. Replacing the loop in TWIST1 bHLH domain with that of NEUROD1 renders it incapable of cooperating with ALX4 (Figure 6G), without affecting ability of the bHLH domain to bind at canonical E-box sites (Figure S6E), underscoring the importance of the loop in mediating specificity of the cooperative binding. Interestingly, a recent study showed that the bHLH loop of the yeast pioneer factor Cbf1 is involved in nucleosome contacts critical for nucleosome binding94, suggesting that the bHLH loop may have pleiotropic biochemical functions. More work is needed to map the network of potential and observed cooperativity among TFs, but we propose that loops offer a mechanism that balances specificity with flexibility.

Materials and Methods

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Joanna Wysocka (wysocka@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids generated in this study will be deposited in Addgene upon peer-reviewed publication. All other reagents are available upon request.

Data and code availability

All sequencing datasets have been deposited in NCBI GEO at accession GSE230319. Accession numbers of analyzed publicly available datasets are listed in Table S2. ENCODE datasets were downloaded from https://www.encodeproject.org/. CCLE data were downloaded from https://depmap.org/portal/download/all/, Release 22Q1 “CCLE_expression.csv” and “sample_info.csv”. Mass spectrometry peptide spectrum match counts are provided in Table S3. The TWIST1-TCF4-ALX4 crystal structure atomic coordinates and diffraction data have been deposited to Protein Data Bank under accession 8OSB. All original code have been deposited to Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7847853.

Cell culture

H9 cells (WiCell, WA09, RRID:CVCL_9773) were cultured in feeder-free conditions, in mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies, 85850) on Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning, 356231) and passaged using ReLeSR (Stem Cell Technologies, 05872) every 4–6 days. Cells were switched to mTeSR Plus medium (Stem Cell Technologies, 100–0276) prior to and during genome editing and clonal expansion, but switched back to mTeSR1 before differentiation to CNCC. hESCs were differentiated to CNCC as previously described20,28. Briefly, hESC colonies were partially detached from the plate with collagenase IV (Gibco, 17104019) in Knockout DMEM medium (Gibco, 10829018) for 30–60 min and scraped to break up large colonies, and then cultured in Neural Crest Differentiation Medium (50%−50% v/v mixture of DMEM/F12 1:1 medium with L-glutamine, without HEPES (Cytiva, SH30271.FS) and Neurobasal medium (Gibco, 21103049) with 0.5x N2 NeuroPlex (Gemini Bio, 400–163) and Gem21 NeuroPlex (Gemini Bio, 400–160) supplements and GlutaMAX (Gibco, 35050061), and 1x antibiotic/antimycotic, and 20 ng/ml EGF (Peprotech, AF-100–15), 20 ng/ml bFGF (Peprotech, 100–18B), and 5 ug/ml bovine insulin (Gemini Bio, 700–112P)) for 11 days in bacterial-grade petri dishes, changing the plate to prevent attachment for 4 days and then leaving the cells unfed for two days to allow attachment, and then fed as needed at least every other day. At day 11, cells (now called ‘early hCNCC’) were harvested by treatment with Accutase (Sigma-Aldrich, A6964–100ML), strained to remove residual neuroectodermal spheres, and plated onto plates coated with 7.5 ug/ml human fibronectin (Millipore, FC010–10MG) and cultured in Neural Crest Maintenance Medium (Neural Crest Differentiation Medium with bovine insulin replaced by 1 mg/ml BSA (Gemini Bio, 700–104P)). These hCNCC were then passaged every 2–3 days upon reaching confluency, with cells in the third or subsequent passages defined as ‘late hCNCC’ and cultured with added 50 pg/ml BMP2 (Peprotech, 120–02) and 3 uM CHIR-99021 (Selleck, S2924).

dTAGV-1 (Tocris, 6914/5) was dissolved in DMSO at 5 mM and then diluted to 250 uM in 60% DMSO/40% water (v/v) before dilution to 500 nM for acute depletions (up to 1 day) or diluted directly from the 5 mM stock for long-term depletions. For acute depletion time courses, an equivalent amount of DMSO (0.12% v/v final) was added to all samples starting 24 h before harvest, and cells for all time points were harvested simultaneously.

RS4;11 cells (ATCC, CRL-1873, RRID:CVCL_0093) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, 11875093) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS and 1x antibiotic/antimycotic.

HEK293 cells (ATCC, CRL-1573, RRID:CVCL_0045) and 293FT cells (Invitrogen, R70007, RRID:CVCL_6911) were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium with sodium pyruvate and L-glutamine, supplemented with 10% v/v FBS and 1x GlutaMAX, non-essential amino acids, and antibiotic/antimycotic.

O9–1 cells (Millipore, SCC049, RRID:CVCL_GS42) used for spike-in controls for ChIPs of TWIST1 depletions were cultured in Complete ES Cell Medium with 15% FBS (Millipore, ES-101-B), 25 ng/ml bFGF, and mLIF (Millipore, ESG1107).

Oligonucleotides

Primers used in this study are listed in Table S4.

Plasmids and cloning

AAV donor templates were cloned into the pAAV-GFP (Addgene plasmid # 32395) backbone by digesting pAAV-GFP with SpeI-HF (New England Biolabs, R3133S) and XbaI (New England Biolabs, R0145S) and performing Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs, E2611S) with PCR products of the ~1 kb homology arms and tags. Flexible linkers (glycine-serine or glycine-alanine) of 5–11 aa were added in between the degron and epitope tags and the TF of interest.

Plasmids in the pCAG backbone used to overexpress TWIST1 and ALX4 in HEK293 cells were cloned by digesting the pCAG-NLS-HA-Bxb1 plasmid (Addgene plasmid # 51271) prepared from dam-/dcm- E. coli (New England Biolabs, C2925H) with SalI-HF (New England Biolabs, R3138S) and BclI (New England Biolabs, R0160S) followed by Gibson assembly with PCR products of desired inserts.

Plasmids in the pcDNA3.1 backbone used to overexpress V5-tagged TWIST1/NEUROD1 and ALX4 in HEK293 cells were cloned by PCR of the pcDNA3.1 backbone and desired inserts followed by Gibson assembly.

Coding sequences of MSX1 (NM_002448.3, OHu18516D), PRRX1a (NM_006902.5, OHu23742D), PRRX1b (NM_022716.4, OHu15551D), PHOX2A (NM_005169.4, OHu18020D) were ordered from Genscript. TWIST1 was amplified from H9 gDNA, with tags added following the second ATG at the beginning of the coding sequence. NEUROD1 was amplified from PB-iNEUROD1_P2A_GFP_Puro (Addgene plasmid # 168803). FKBP12F36V-V5 (for N-terminal tagging) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. FKBP12F36V-mNeonGreen-V5 (for C-terminal tagging) was amplified from pAAVhSOX9-dTAG-mNeonGreen-V5 (Addgene plasmid #194971).

The pGL3-noSV40-humanEC1.45_min1–2_4xEboxMutant plasmid was generated by mutating all four E-box motifs within Coordinator motifs in silico at the positions with greatest information content in the PWM. The sequence containing mutant EC1.45 E-box motifs was ordered from Twist Bioscience and cloned into the pGL3 luciferase reporter vector.

AAV preparation

AAV production was performed by transfecting 293FT cells with 22 ug of pDGM6 helper plasmid (Addgene plasmid # 110660), 6 ug of donor template plasmid, and 120 ug polyethylenimine (Sigma-Aldrich, 408719) diluted in Opti-MEM (Gibco, 31985070) in 1 ml total volume per 15-cm plate (4 plates were used per construct). Twenty-four hours after transfection, media was changed to media with 2% FBS. Three days after transfection, cells were harvested by scraping, triturated by pipetting up and down, centrifuged at 1000g for 20 min at 4°C, resuspended in 1.5 ml AAV lysis buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl) per 2×15 cm plates, and then flash frozen for storage. Samples were passaged through a 23-gauge needle and then freeze-thawed three additional cycles to lyse cells. Lysates were then treated with Benzonase (Millipore, 71205–3) for 1 h at 37°C with intermittent mixing, centrifuged at 2000g for 20 min at 4°C, and then the supernatant was flash frozen for storage at −80°C. OptiSeal tubes (Beckman Coulter, 362183) were filled from the bottom (with a blunt 18-gauge needle attached to a syringe), in order, with layers of 9.7 ml of 25% OptiPrep Density Gradient medium (Sigma-Aldrich, D1556–250ML) in 100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 1.5 M NaCl, 100 mM MgCl2; 6.4 ml of 41.7% OptiPrep in 100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 0.5 M NaCl, 100 mM MgCl2, and 12 ug/ml Phenol Red; 5.4 ml of 66.7% in 100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 0.5 M NaCl, 100 mM MgCl2,, and 5.4 ml of 96.7% OptiPrep Density Gradient medium (Sigma-Aldrich, D1556–250ML) in 33.3 mM Tris pH 7.6, 167 mM NaCl, 33 mM MgCl2 with 0.012 mg/ml Phenol Red. Lysate was gently added on top, the tubes were filled with AAV lysis buffer, and centrifuged at 48,000 rpm at 18°C in a Beckman VTi 50 rotor for 70 min with max acceleration and braking at a setting of 9. The viral fraction above the 66.7%−96.7% OptiPrep interface was collected using an 18-gauge needle and syringe and then washed with cold PBS using an Amicon Ultra-15 100K filter (Millipore, UFC910008). Purified AAV was then flash frozen in aliquots for storage at −80°C. To calculate AAV titers, an aliquot was digested with Turbo DNase (Invitrogen, AM2238) per manufacturer’s instructions, inactivated with 1 mM EDTA final concentration and incubation at 75°C for 10 min, and then digested with proteinase K in 1 M NaCl and 1% w/v N-lauroylsarcosine at 50°C for 2h. Samples were then boiled for 10 min, and diluted in H2O to 1:20,000 and 1:200,000. DNA standards comprising 1010 - 103 molecules were prepared using AAV6 backbone plasmids containing inverted terminal repeats. Quantitative PCR was carried out on standards and test samples using the LightCycler 480 Probes Master kit (Roche, 04707494001) with inverted terminal repeat probe and primer sequences indicated in Table S4.

Genome editing

H9 cells were treated with 10 uM Y-27632 (Stem Cell Technologies, 72304) for at least 2 h prior to nucleofection, and then harvested as single cells with Accutase. For each editing experiment, 800,000 cells were nucleofected with 1.7 ul (17 ug) SpCas9 HiFi (Integrated DNA Technologies) and 3.3 ul of 100 uM annealed crRNA XT and tracrRNA (pre-incubated for 15 min at room temperature to form RNPs) and for generating ALX4 knockout, 2 ul of 100 uM ssDNA homology-directed repair (HDR) template, using the P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit L (Lonza, V4XP-3034) and the CA-137 program. When AAV was used to deliver HDR template, the AAV was diluted to 25,000 viral genomes per cell in medium and added to the plate before adding the nucleofected cells. Media was changed 4 h after nucleofection, and then cells were cultured until nearing confluency, at which point cells were diluted to single cells and plated at low densities (~500 cells per well of a 6-well plate). Resulting colonies were picked and a portion of the cells lysed by QuickExtract (Lucigen, QE9050) and used to genotype by PCR with primers on either side of the insertion site (in most cases with one primer outside the homology arms; see Table S4 for primer sequences) and gel electrophoresis or Sanger sequencing. Putatively edited colonies were confirmed by genomic DNA extraction using the Quick-DNA mini prep kit (Zymo, D3024) and Sanger sequencing. All gRNA and primer sequences are listed in Table S4.

Transfection

HEK293 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668019) at a ratio of 2.8 ul lipofectamine per ug of DNA, diluted in Opti-MEM. Cells were transfected with 2.5 ug DNA per well of a 6-well plate or 15 ug DNA per 10-cm plate 1–2 days after seeding, when they reached 70–90% confluency. Media was replaced 4–6h after transfection, and then cells were harvested for Western blot or chromatin immunoprecipitation at 24 h after transfection.

hCNCCs were transfected with FuGENE 6 (Promega, E2691) immediately after passaging, using 1 ul of FuGENE 6 per 3 ug of DNA and 100 ng DNA diluted in 50 ul Opti-MEM per well of a 24-well plate.

Luciferase assay

hCNCCs were transfected with 0.5 ng pRL renilla control plasmid, 10 ng modified pGL3 reporter plasmid, and 89.5 ng carrier plasmid (pUC19) per well of a 24-well plate, in triplicate. Cells were lysed 24 h after transfection and assayed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay kit (Promega, E1960).

Western blot

Cells were washed with cold PBS, lysed by incubation for 10 min on ice in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) with 1x cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11873580001), and sonicated for 6 cycles of 30s ON/30s OFF on high power using the Bioruptor Plus (Diagenode). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at >16,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was quantified by BCA protein assay (Thermo, 23225) and then denatured by addition of 1x NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, NP0007) and 100 mM DTT and heating to 95°C for 7 min. Samples were normalized by BCA quantifications and then loaded in 4–12% or 4–20% Novex Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) and run at 165V for ~1 h in Tris-glycine buffer (25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine) with 0.1% SDS. Gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 400 mA in Tris-glycine buffer with 20% methanol, stained with 0.1% Ponceau S in 3% trichloroacetic acid, then blocked with 5% milk and 1% BSA in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) for 15 min at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody incubation for 1 h at room temperature, with 4 washes of PBST after each antibody incubation. Antibodies used include TWIST1 (Abcam, ab50887, RRID:AB_883294, 1:500), ALX4 (Novus Bio, NBP2–45490, 1:1000), ALX1 (Novus Bio, NBP1–88189, 1:1000), MSX1 (Origene, TA590129, 1:5000), PRRX1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-293386, 1:500), CTCF (Cell Signaling, 2899, 1:2000), HSP90 (Cell Signaling, 4877, 1:2000), V5 (Abcam, ab206566, 1:2000), Flag (Sigma, F1804, 1:2000), HA (Abcam, ab9110, 1:2000), Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP (Jackson Immunoresearch, 711–035-152, RRID:AB_10015282, 1:3000), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) HRP (Jackson Immunoresearch, 115–005-003, RRID:AB_2338447, 1:3000). Chemiluminescence was performed with Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Prime reagent (Cytiva, RPN2232) and imaged with an Amersham Imager 800 (Amersham).

ATAC-seq

Omni-ATAC was performed essentially as published100, with 30 min treatment with 200 U/ml DNase I (Worthington, LS006331) at 37°C prior to harvesting cells, using Ampure XP (Beckman Coulter, A63881) beads to clean up the DNA. Briefly, treated cells were harvested by Accutase, counted using the Countess II (Invitrogen), and 50,000 cells were collected by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (resuspension buffer (RSB), or 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, and 3 mM MgCl2, with 0.1% Igepal CA-630, 0.1% Tween-20, and 0.01% digitonin) for 3 min, then quenched by dilution with RSB with 0.1% Tween-20. Lysate was centrifuged for 10 min at 500g at 4°C and then resuspended in transposition buffer (25 ul TD buffer and 2.5 ul TD enzyme (Illumina, 20034197), 16.5 ul PBS, 0.01% digitonin, 0.1% Tween-20, and water up to 50 ul). Transposition reactions were performed for 30 min at 37°C, and then cleaned up with the DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kit (Zymo, D4013) and eluted in 21 ul 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8. DNA was then pre-amplified 5 cycles with NEBNext Ultra II Q5 master mix (New England Biolabs, M0544) with a cycling protocol of 72°C for 5 min, 98°C for 30s, and 5 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 63°C for 30s, 72°C for 1 min. Then 5 ul of the 50 ul reaction was used to run a qPCR reaction (with the same cycling protocol except the initial 72°C incubation) to determine the optimal number of PCR cycles for each sample. The remaining portion of the reaction was then amplified the appropriate number of cycles, and then subjected to two rounds of double-sided Ampure XP bead cleanup, with 0.5x/1.3x and 0.5x/1.0x bead ratios (numbers indicate bead ratios added in first and second steps). Libraries were quantified by Qubit dsDNA high sensitivity assay (Invitrogen, Q33231), run on a 5% polyacrylamide TBE gel to check the size distribution, and then pooled for sequencing.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation