Abstract

Researchers and policymakers have proposed systems to detect novel pathogens earlier than existing surveillance systems by monitoring samples from hospital patients, wastewater, and air travel, in order to mitigate future pandemics. How much benefit would such systems offer? We developed, empirically validated, and mathematically characterized a quantitative model that simulates disease spread and detection time for any given disease and detection system. We find that hospital monitoring could have detected COVID-19 in Wuhan 0.4 weeks earlier than it was actually discovered, at 2,300 cases (standard error: 76 cases) compared to 3,400 (standard error: 161 cases). Wastewater monitoring would not have accelerated COVID-19 detection in Wuhan, but provides benefit in smaller catchments and for asymptomatic or long-incubation diseases like polio or HIV/AIDS. Monitoring of air travel provides little benefit in most scenarios we evaluated. In sum, early detection systems can substantially mitigate some future pandemics, but would not have changed the course of COVID-19.

Introduction

It has been widely debated which policies, if any, could have mitigated the health impacts of the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 and early 2020 as community transmission became established and widespread. Early studies compared non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as mobility restrictions1,2, school closures3,4, voluntary home quarantine5 and testing policies6, and optimized NPI parameters like testing frequency7, quarantine length8, testing modality9, test pooling10 and intervention timing and ordering11. While such NPIs undoubtedly slowed the early spread of COVID-1912 and previous outbreaks13,14, there has been little investigation of whether a separate strategy focused on earlier detection of COVID-19 would have enabled more successful mitigation. In theory, earlier detection enables a response when the outbreak is smaller: thus, resource-intensive mitigation strategies like test-trace-isolate become less costly, and the earlier interventions are applied, the larger the number of infections and deaths that can be delayed until healthcare capacity is increased15. However, the relevant question is not whether early detection helps, but quantitatively how much of a difference it would make. This question is especially urgent given current international and national policy proposals to invest billions of dollars in such systems16,17.

Researchers and policymakers have proposed immediate investments in systems to continuously monitor for novel pathogens in (i) patients with infectious symptoms in hospitals and clinics18,19, (ii) community wastewater treatment plants20,21, and (iii) airplane sewage or bridge air on international flights22–24, as well as other sites25–29. These three sites have attracted interest because they have been frequent testing sites in COVID-19: hospitals since the pandemic’s beginning30, and wastewater (including wastewater at treatment plants20, within the sewershed31, and locally near individual buildings32) and air travel more recently33,34 because hospital cases can lag community cases35. COVID-19 also spurred methodological innovation and characterization of sampling from these sites36, particularly wastewater37–39. Detecting novel pandemics at these sites has occasionally been piloted21,40 but has not been implemented at scale, in part because it is unclear if these proposed systems sufficiently expedite detection of outbreaks. The systems under consideration would use multiplex testing for conserved nucleic acid sequences of known pathogen families, exploiting the fact that many past emerging diseases belonged to such families, including SARS-CoV-2 (2019), Ebola (2013), MERS-CoV (2012), and pandemic flu (2009). Proposed technologies include multiplex PCR41–44, CRISPR-based multiplex diagnostics45, and metagenomic sequencing46, possibly implemented with pooling10.

To determine whether early detection of novel pathogens at these sites could be effective in changing the course of a pandemic, we first examined whether COVID-19 could have been detected earlier in Wuhan if systems had been in place in advance to monitor hospitals, wastewater or air travel. To do this, we developed, empirically validated, and mathematically characterized a simulation-based model that predicts the number of cases at the time of detection given a detection system and a set of outbreak epidemiological parameters. We then used this model and COVID-19 epidemiological parameters47 to estimate how early COVID-19 would initially have been detected in Wuhan by the three early detection systems, and compare this to the actual date of COVID-19 detection. Finally, we use our model to estimate detection times of infectious agents with different epidemiological properties, such as mpox and polio in recent outbreaks48,49, to inform pathogen-agnostic surveillance for future pandemics.

Results

Model to estimate earliness of detection

Previous research15 and our analysis (Supplementary text, figs. S1–5 and table S1) suggest that earlier COVID-19 lockdowns could have delayed cases and deaths. Thus, it is critical to understand which early detection systems, if any, could have effectively enabled earlier response. To do this, we built a model that simulates outbreak spread and earliness of detection for a given outbreak and detection system (Materials and methods, Supplementary materials). This builds upon branching process models that have previously been used to model the spread of COVID-1950,51 and other infectious diseases52. A traditional branching process model starts from an index case and iteratively simulates each new generation of infections. Our model follows this pattern, but with each new infection we also simulate whether the infected person is detected by the detection system with some probability (Fig. 1A), and the simulation stops when the number of detected individuals equals the detection threshold and the detection delay has passed. Thus, each detection system is characterized by these three parameters of detection probability, threshold, and delay (table S2). For example, in hospital monitoring, an infected individual’s detection probability is the probability they are sick enough to enter the hospital, which is the hospitalization rate (assuming testing has a negligible false negative rate). In systems that test individuals (hospital and air travel individual monitoring), the threshold is measured in an absolute number of cases. In systems that test wastewater (wastewater monitoring), the threshold is measured in terms of outbreak prevalence because wastewater monitoring can only sample a small percentage of sewage flows, depending on the sampling capacity53; thus, a higher number of cases is required to trigger detection in a bigger community (Materials and methods). We gathered literature estimates of detection system and outbreak parameters (tables S2 and S3) and validated wastewater monitoring sensitivity in independent data (fig. S6 and Materials and methods, Supplementary materials). We then empirically validated the model by testing its ability to predict the detection times for the first COVID-19 outbreaks in 50 US states in 2020. We gathered the dates of the first COVID-19 case reported by the public health department of each US state (table S4) as well as literature estimates of true (tested and untested) statewide COVID-19 case counts in early 202054. Using our model, we were able to predict the number of weeks until travel-based detection in each US state to within a mean absolute error of 0.97 weeks (fig. S7 and S8). To check the robustness of our results, we implemented a second, more complex model with varying reproduction number using a Monte Carlo simulation-based package (EpiNow255). A list of model assumptions can be found in table S5.

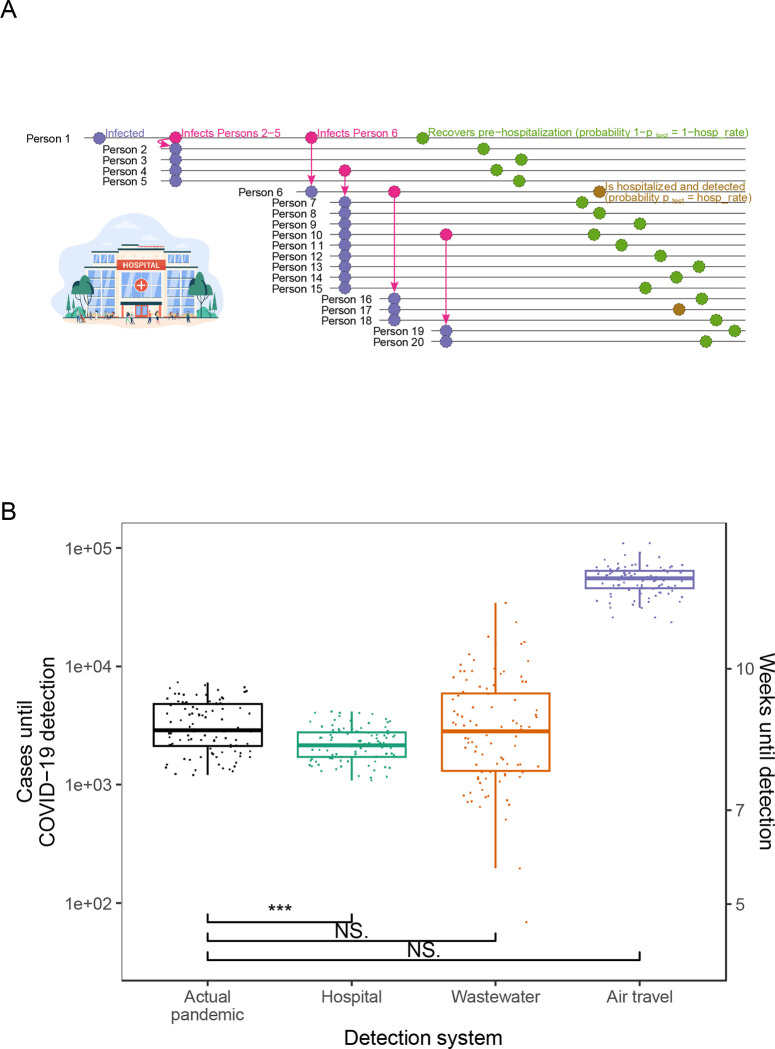

Fig. 1. Comparison of COVID-19 detection times in the actual pandemic versus with proposed early detection systems.

(A) Schematic of first 20 infections in a simulated run of the detection model. In this run, Person 1 seeds an outbreak in a community covered by a hospital detection system. Each person infects a number of individuals determined by a draw from a negative binomial distribution. Each person is then detected by the detection system with probability (gold) or goes undetected (olive); in the hospital system, equals the hospitalization rate. (B) Estimated cases until COVID-19 detection in the actual pandemic versus model-simulated cases until detection for proposed detection systems (center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, point closest to 1.5x interquartile range). Estimates for the actual pandemic are drawn from56. Points for proposed detection systems are simulated case counts from the model (actual pandemic (black), hospital (teal), wastewater (orange) and air travel (purple)) assuming a Wuhan-sized catchment (650,000 people). Three, two, and one asterisk(s) signify that the cases upon detection for the detection system are statistically significantly lower than those in the actual pandemic at the 0.001, 0.01, and 0.05 levels, respectively, in one-sided t-tests. NS. signifies not statistically significantly lower at p=0.05. Equivalent weeks until detection are shown on the right y-axis.

Early detection’s impact on COVID-19 detection in Wuhan

Next we use our model to examine the detection systems’ ability to detect the first major COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan (Fig. 1B and table S2). To estimate cases at detection in the actual pandemic, we used literature estimates of total (tested and untested) COVID-19 case counts in Wuhan in late 2019 and early 202056. Our model shows that, on average, hospital monitoring could have detected COVID-19 after 2,292 cases (standard error: 76 cases). In reality, the pandemic was identified after 3,413 cases on average (standard error: 161 cases). Thus, hospital monitoring would have caught the outbreak 1,121 cases earlier (approximately 0.43 weeks earlier), a statistically significant difference with p = 1.9e-09 and t = −6.3 (df = 141) in a one-sided Welch two-sample t-test. Wastewater monitoring would have lagged detection in the actual pandemic; it caught the outbreak after 4,575 cases (standard error: 523 cases), or 1,162 cases later, on average (p = 0.018; t = 2.1; df = 118). We tested this wastewater prediction empirically by calculating the cases until COVID-19 wastewater detection in Massachusetts in early 2020, using literature-estimated Massachusetts COVID-19 cases54 and Massachusetts wastewater SARS-CoV-2 PCR data57; our model prediction was consistent with this analysis (fig. S9). Because we model wastewater monitoring to detect later in larger communities (Materials and methods, Supplementary materials), the Wuhan result is in part due to Wuhan’s 650,000-person catchments. Wastewater monitoring would lead status quo detection of COVID-19 in catchments smaller than 480,000 people, well above the global mean catchment size of 25,000 people58. Air travel monitoring did not provide any acceleration of detection because of the low probability of simultaneously traveling and being sick.

Early detection’s impact for other diseases: mathematical analysis and simulation

To make our model easily usable for pathogenic outbreaks beyond COVID-19, we derived a compact formula that approximates the model’s simulations. We observed that, without accounting for the delay of generations between the threshold case’s infection and detection, the number of cases until detection, , is a random variable that follows a negative binomial distribution by definition: each infected case is a Bernoulli trial, “success” in that trial occurs when that case enters the detection system (with a probability we name ), and we count the number of cases until the number of successes equals the detection threshold . After accounting for and the basic reproduction number , we derived a formula approximating the mean of when the outbreak starts in a community covered by the detection system (see Supplementary Text for full derivation):

| (1) |

We confirmed our formula approximates the simulation model closely by comparing the detection times predicted by both for all the detection systems for multiple diseases (fig. S10). Thus, the formula allows us to interpret the model and the quantitative relationships between detection times and various variables: the formula shows that the number of cases until detection increases linearly with the detection threshold, increases polynomially with and exponentially with the delay as , and decreases as the fraction of cases being tested increases. This formula also makes the model easily usable for detection systems beyond the ones studied here.

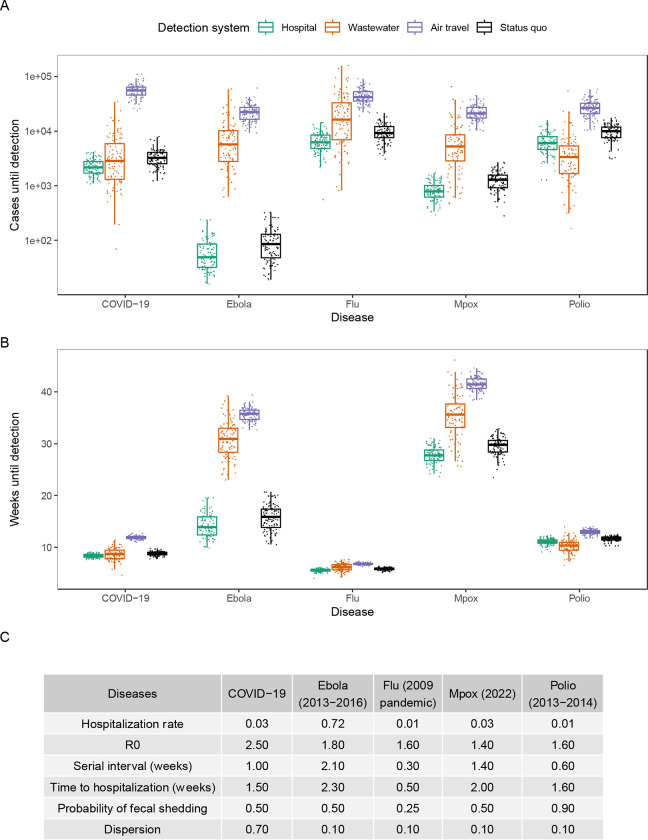

We applied our model to several outbreaks of recent interest–including COVID-19, mpox (2022), polio (2013–2014), Ebola (2013–2016) and flu (2009 pandemic)–and found that the detection systems vary in their success depending on the epidemiological parameters of the agent (Figs. 2, S11 and S12, and table S3). For example, in our model hospital monitoring tends to outperform wastewater monitoring when the hospitalization rate is high, as in the case of Ebola, but tends to underperform for diseases like polio, in which the hospitalization rate is low and when there is high asymptomatic spread in the delay from detection to hospitalization. This is consistent with Equation (1), as well as previous observations that Ebola was first detected in hospitals59 and that wastewater monitoring has been more effective than hospital monitoring for detecting polio60. We also modeled the status quo detection times for these outbreaks: the number of cases until these outbreaks were detected in the status quo, without the proposed detection systems in place. We found that early detection systems can catch outbreaks when they are up to 52% smaller (wastewater for polio) or 110 weeks earlier (hospital for HIV/AIDS) (figs. S13, S14, S15 and S16). Similar results hold for the more complex model: the relative median detection times of the three systems remain the same 97% of the time across the five main diseases (29/30 pairwise comparisons) (fig. S17).

Fig. 2. Comparison of detection systems for different infectious diseases.

(A) Earliness of detection for detection systems in cases across infectious diseases (hospital (teal), wastewater (orange), air travel (purple) and status quo (black)) in a 650,000-person catchment (center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, point closest to 1.5x interquartile range). (B) Earliness of detection for detection systems in weeks across infectious diseases in a 650,000-person catchment. (C) Epidemiological parameters of the studied diseases.

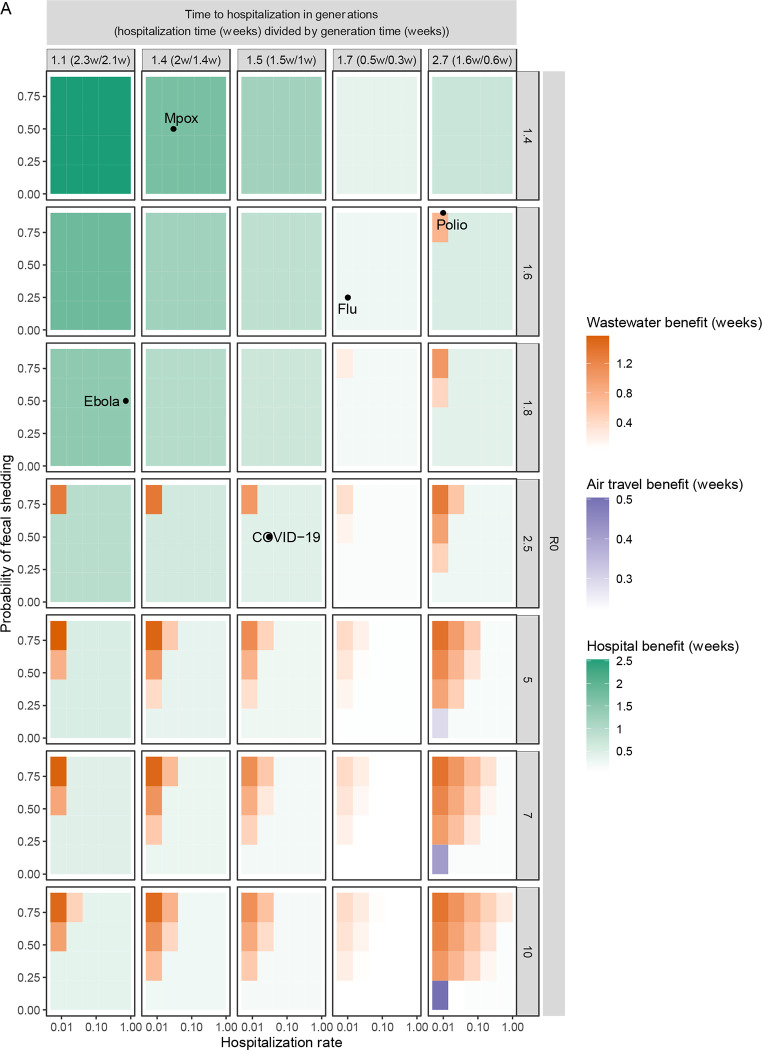

Because future infectious diseases are likely to have different epidemiological parameters, we generalized the previous analysis and calculated detection times for many possible diseases spanning the epidemiological parameter space (Figs. 3 and S18). As expected, hospital monitoring is the best system for diseases with higher hospitalization rates and lower times to hospitalization. For diseases with higher s and times to hospitalization, wastewater monitoring emerges as the best system more often, because hospital monitoring has a longer detection delay (mainly the time from infection to hospitalization) than wastewater (mainly the time from infection to fecal shedding), during which cases grow exponentially with . However, this holds mainly for diseases with high probability of fecal shedding and low hospitalization rate. Air travel monitoring, which did not perform well in the previous modeled diseases (Figs. 1 and 2), actually performed best for a few diseases for which fecal shedding is low (disadvantaging wastewater monitoring) and the time to hospitalization and are too large (disadvantaging hospital monitoring).

Fig. 3. Comparison of detection systems across the space of possible diseases of varying epidemiological parameters.

(A) Average weeks gained over status quo detection by the proposed detection systems across the epidemiological space of possible diseases. Within each panel, each uniformly colored cell corresponds to a specific disease with the hospitalization rate and probability of fecal shedding indicated on the x- and y-axes, as well as the and time to hospitalization (generations) indicated by the panel row and column. The cell has a hue corresponding to the detection system that detects the disease the earliest (hospital (teal), wastewater (orange) and air travel (purple)) and an intensity corresponding to the number of weeks gained by the earliest system over status quo detection. Times are calculated by the derived mathematical approximation in a 650,000-person catchment.

Discussion

Our results show that the benefits of early detection systems vary from marginal (0.4 weeks earlier for COVID-19) to significant (110 weeks earlier for HIV/AIDS) (Figs. 1B, 2, and S16). Our detection time model (Fig. 1A) can be used for many diseases and detection systems, including other systems beyond this study25,26, by varying the fraction of the infected population being tested in each system. Some further points are worth emphasizing. First, early detection only aids mitigation if it leads to a coordinated early response. Many factors beyond detection affect the pace of response, including the economic and political feasibility of lockdowns, the availability of medicines and personal protective equipment, and whether there are pre-determined policies to be implemented upon detection. Second, when deciding to invest in these systems, one must consider factors such as cost-effectiveness and whether the system provides evidence of disease severity. Although wastewater monitoring gives earlier detection than hospital monitoring in multiple diseases (Fig. 3A), it does not discriminate between mild and severe disease (although sequencing could detect lineages known to cause severe illness). In contrast, hospital monitoring provides evidence that the detected pathogen produces symptoms that require hospital treatment. Third, our model is meant to be used now, in advance of future pandemics, and not in the early months of a novel pandemic, because early detection systems must be set up in advance of the next pandemic to be effective. Because we do not know the epidemiological parameters of the next pandemic, our study assesses how these systems would perform for a wide, representative variety of diseases with different epidemiological parameters, in order to quantify these systems’ benefits in general.

These results can inform ongoing international and national policy debates about which policies are needed to mitigate future pandemics. In the wake of COVID-19, the World Health Organization Intergovernmental Negotiating Body is actively negotiating a new treaty on international pandemic preparedness which updates the International Health Regulations (2005). Drafts of this treaty highlight “early warning and alert systems” as key measures16. Similarly, the presidential administration of the United States has proposed investing $5.3 billion over 7 to 10 years in early warning and real-time monitoring systems, including in hospitals and wastewater17. In this study, we have assessed detection systems’ detection times and have developed a model to assess current and future detection system proposals. Along with additional cost-effectiveness analysis and technical pilots21, these results can help inform which detection systems are most effective and thus worth funding in pandemic preparedness efforts.

Methods

Description of model predicting cases at detection.

Our branching process-based model predicts the cumulative number of cases at the time of detection for a given detection system and outbreak. It follows the approach of branching process simulation models used previously to model the spread of COVID-1950,51 and other infectious diseases52, but with the main added step of simulating each infected person’s chance of being detected by the detection system. The values for parameters for detection systems can be found in table S2. The values for epidemiological parameters for outbreaks (, serial interval, dispersion, hospitalization rate, and time to hospitalization) can be found in Fig. 2 and table S3. As in previous models52, we assume the offspring distribution (the number of secondary cases infected by each primary case) is negative binomial with mean .

We generally follow past detection system proposals19,21 to determine the implementation details of each system in our model. Our model assumes the following. In hospital monitoring, hospitals would test for high-priority pathogen families (e.g. coronaviruses) in patients presenting with severe infectious symptoms in hospital emergency departments19. Similarly, in wastewater monitoring, governments would test for pathogens in city wastewater treatment plants daily, and monitor for high and increasing levels of high-priority pathogen families21. In air travel monitoring, we model testing of individual symptomatic passengers (differs from proposals to monitor airplane sewage22 or bridge air) on incoming international flights for the same pathogens. The parameters of these systems are shown in table S2.

Our model also accounts for different delays involved in different detection systems. For example, if the 500th case of a COVID-19-like outbreak triggers the detection threshold in both the hospital and wastewater monitoring systems, because of the significant delay from infection to hospitalization compared to the delay from infection to fecal shedding, the wastewater system would catch the outbreak earlier.

In systems that test individuals (hospital and air travel individual monitoring), the threshold is measured in an absolute number of cases. In systems that test wastewater (community and air travel wastewater monitoring), the threshold or sensitivity is measured in prevalence (cases as a percentage of the population)53,61,62. To predict the number of cases and time to detection, we need to convert this percentage back to a number of cases, so the wastewater detection time depends on the catchment population size.

To estimate wastewater sensitivity measured in prevalence, we used data from53.53 conducted PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 1687 longitudinal wastewater samples from 353 sampling locations in 40 US states in early 2020, and synced these with publicly reported local daily new COVID-19 case counts. This enables us to estimate a distribution of the wastewater sensitivity: the lowest case count required to trigger positive detection in wastewater. Of the 353 sampling locations, 47 had both SARS-CoV-2-positive and negative samples such that local case counts on days of positive samples were all higher than those on days of negative samples. We thus knew each sampling location’s sensitivity is between the maximum of case counts on negative sample days and the minimum of case counts on positive sample days. We took the midpoint of this maximum and minimum as the location’s sensitivity; this gave us 47 local sensitivities. We fitted this to a log-normal distribution with a median of 2.5 daily new cases per 100,000 people. As expected, this distribution is similarly shaped but slightly left-shifted of the distribution in Figure 2b of53 (median 3.7 per 100,000), because the latter distribution is an upper bound of the former.

To use this distribution in our model, in each simulation run, we first randomly drew a wastewater sensitivity from this distribution, and then we needed to convert this reported incidence i to the true (reported and unreported) number of cases shedding fecally into public wastewater systems up to the time of wastewater detection. We converted as follows. Let day T be the day on which the incidence i is reported. First we assumed the wastewater SARS-CoV-2 level on day T is proportional to the number of COVID-19 cases who are fecally shedding on day T, which we estimate as the number of fecal shedders infected 2 days before, given the dominant peak in fecal shedding on day 2 of infection61. We infer the number of fecal shedders infected on day T-2 from the incidence as follows. To account for underreporting, we first estimate a true daily incidence of 5.7 x i with symptom onset on day T, based on estimates of the ratio of true (dated by symptom onset) to reported (dated by reporting date) COVID-19 cases in the United States in early 202054. (This study’s abstract reports true cases are 5–50x reported ones, but this refers to the early March 1-April 4, 2020, period. We calculated the factor of 5.7 from the study’s data when we use the fuller March 1-May 16 period, which overlaps better with the February-June 2020 period in53 and reflects less underreporting as the pandemic developed and testing capacity increased. We calculated this underreporting factor as an average of state-level underreporting factors, weighted by frequency of each state among the wastewater samples in53.) Finally, we multiply by (a) the fraction of cases who shed fecally (0.563) and (b) the fraction of people connected to central sewage (0.8 in the US64, which is the area from which the53 threshold is derived). This gives us the one-time prevalence of cases who contribute to the wastewater SARS-CoV-2 level on day . For a given catchment with population , this one-time number of cases is , and we estimate the cumulative number of fecal shedders up to this time as , where is the number of days for the daily exponential outbreak incidence curve to grow from 1 to cases.

To check this estimate, we identified studies that compared wastewater and hospital COVID-19 trends20,53.20 found that trends in wastewater SARS-CoV-2 values led trends in hospital admissions by 1–4 days in New Haven (catchment size 2e+05). We estimate that wastewater detection would lead hospital detection of COVID-19 in New Haven by −0.8 to 3 weeks (90% CI). This is consistent with the 1–4d lead estimate from20. Similarly,53 found that trends in wastewater led those in clinical data by 4 days in Massachusetts (catchment size 2,300,000). Their clinical data are dated by date of reporting rather than sample gathering; assuming that hospital admissions are 5 days ahead of tests by date of reporting20, then wastewater is 5d-4d=1 day behind hospital admissions. We estimate that wastewater detection would lead hospital detection of COVID-19 in Massachusetts by −4 to −0.09 weeks (90% CI). This is consistent with the 1-day lag estimate from53.

Validation of model in US states.

We gathered two sources of data for each state: dates of COVID-19 detection and COVID-19 case counts in early 2020. For the former, we searched media reports and US state public health press releases to determine the dates of the first COVID-19 case reported in each US state. Sources for each state’s detection date are listed in table S4. We were able to identify such dates for all 50 states.

For the latter, we used literature estimates of true (tested and untested) COVID-19 case counts, which incorporate COVID-19 mortality data to deal with variation in testing capacity among states54. We received a time series of weekly symptomatic COVID-19 case estimates for March 1-May 10, 2020 and divided by a symptomatic rate of 0.55 to get an estimate of total (symptomatic and asymptomatic) cases47. We specifically used estimates from the adjusted mMAP (mortality maximum a posteriori) method because54 had mMAP estimates for all 50 states, whereas other methods from the same study were missing estimates for various states. We fit an exponential curve of case counts in each state to extrapolate cases back to January 2020. In the data we received, all states had case data for all weeks in March 1-May 10, 2020.

We used our model to predict the weeks until detection in each US state (y-axis in Fig. S7). Because most US states detected their first case by travel (table S4), we modeled a travel-based detection system similarly to how we modeled the aforementioned detection systems. We simulated a growing stream of imported travel cases ( cases for the i-th generation and global ), and as for the other detection systems, we simulated infection and detection steps for each generation, except that we only allowed travel-associated cases to be detected. We assumed that the state COVID-19 outbreaks had the same values for all epidemiological parameters except for , which we allowed to vary by state to account for state-specific conditions. We obtained state-specific values from65. The values for shared parameters were obtained from literature (table S3). We used a detection delay of 12 days (5-day incubation period47 plus 7-day test and reporting turnaround in early 2020 in the US66) because many first cases were detected following symptoms. The only parameter we were unable to precisely estimate from literature was the probability of a travel case being detected. We noted that this rate was at most the COVID-19 symptomatic rate (0.5547) and at least the hospitalization rate (0.0347): in the highest-detecting scenario, every symptomatic case would volunteer to be tested; in the lowest-detecting scenario, only hospitalized travel cases would get flagged for testing. So we chose a rate of 0.1, near the two rates’ geometric mean. The predicted detection time for each state (the y-value reported in Fig. S7) was the mean of 100 simulations.

We compared these predictions to ground truth estimates in each state (x-axis in Fig. S7). These ground truth estimates were calculated by summing the aforementioned weekly case counts from the first week of January 2020 until the date of detection in that state (Fig. S8).

Comparison of COVID-19 detection times in the actual pandemic versus with proposed early detection systems.

We used our model to examine whether the early detection systems could have detected COVID-19 earlier than in the actual pandemic. To do this, we used two data sources: (1) literature estimates of total (tested and untested) COVID-19 case counts in late 2019 and early 202056 and (2) simulation output from our model. We then used (1) to calculate the cumulative number of cases when COVID-19 was actually detected, and compared this to results from (2).

For (1), we chose to use estimates from56, which quantifies both the time of SARS-CoV-2 introduction into humans and the time series of cases following said introduction. These estimates are based on phylodynamic rooting methods applied to SARS-CoV-2 sequence data, combined with epidemic simulations and accounting for epidemiological data on the first known cases of COVID-19. These estimates improve upon previous attempts to time SARS-CoV-2’s introduction into humans, which are solely based on phylodynamic rooting methods to quantify the time to the most recent common ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 sequences67.

As instructed by56, we utilized

‘BEAST.primary.IH.Dec10_16.linB.Dec15_25.linA.cumulativeInfections.timedGEMF_combine d.stats.pickle’ from GitHub68 to obtain the distribution of daily case counts. Conditioning on the fact that there were at least six COVID-19-related hospitalizations by 2019–12-2969, we narrowed the distribution to those epidemic simulations with the top 25 percent of hospitalizations and case counts. We simulated 100 draws from this distribution, and then took the number of cases on 2019–12-29 in each simulation to get 100 values for the distribution of cumulative cases at detection in the actual pandemic (‘Actual pandemic’ boxplot in Fig. 1B). We chose 2019–12-29 as the date that COVID-19 was detected in the actual pandemic, because this was the date of the first report of an outbreak of pneumonia cases to health authorities in Wuhan70.

For (2), we ran our model for COVID-19 (see table S3 for the epidemiological parameters used) and all three detection systems (100 simulations for each system). For each detection system, this gave us the estimated number of cases until detection of COVID-19 if that system had been in place at the start of the pandemic. We assumed the system was present in the community in which COVID-19 originated. We compared each system to the actual pandemic, and determined that detection could have occurred earlier with the system if there was a statistically significant difference in cases until detection between the actual pandemic and the simulated world with the system (Fig. 1B). Statistical significance was assessed by a 1-sided t-test in which the alternative hypothesis was that the detection system performed better.

We could empirically test our model predictions for the cases until wastewater detection by using literature-estimated total COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts54 and Massachusetts wastewater SARS-CoV-2 data57 in early 2020. We aimed to use these to estimate the cases until COVID-19 wastewater detection in Massachusetts in early 2020, but because Massachusetts wastewater sampling for COVID-19 started only after the Massachusetts outbreak was underway, wastewater samples were positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the first day of testing, so this first day of testing was later than when wastewater detection could have caught SARS-CoV-2 if wastewater detection had been in place in advance. Thus, we could only calculate an upper bound on the true cases until detection. We utilized the wastewater time series from the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) website and synced it with the COVID-19 case count time series (Fig. S9). We multiplied the Massachusetts statewide cases by 0.33 (equal to 2,300,000/6,900,000) because the MWRA data covers 2,300,000 people, out of 6,900,000 people in Massachusetts in 2020. We then summed these case counts up to the date of apparent wastewater detection to get an upper bound for cases at detection, and checked whether our model prediction was consistent with this bound.

Model-simulated cases required to trigger COVID-19 detection versus mathematical approximations.

We compared the model simulations of cases until detection with our derived mathematical formula, Equation (1) (Fig. S10). The points in Fig. S10 are the same as in Fig. 2A. The dashed lines are generated by plugging values into Equation (1) for each detection system: we plugged in the detection threshold, detection probability, outbreak , and detection delay (measured in number of generations, i.e. serial intervals) for , and , respectively.

Comparison of detection systems for different infectious diseases.

We applied our model to several outbreaks of recent interest: COVID-19, mpox (2022), polio (2013–2014), Ebola (2013–2016) and flu (2009 pandemic) (Fig. 2A). Because of the lack of data on the number of cases at the time of detection in previous outbreaks (except for the COVID-19 data used in Fig. 1B), we used our model to estimate status quo detection times for the outbreaks. Because many recent outbreaks have been detected in healthcare settings59,69,71,72, we assumed status quo detection was similar to hospital monitoring, except with a lower detection probability per case () to reflect that symptomatic cases are less likely to be tested for a panel of diseases without the proposed systematic, proactive testing scheme. The per-case detection probability for status quo was set to 0.67 times that of hospital monitoring to match our modeled status quo detection times for COVID-19 with those estimated independently by56 (Fig. 1B).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We gratefully acknowledge Mauricio Santillana, Nicholas B. Link, Fred S. Lu, and Andre T. Nguyen for sharing their estimates on COVID-19 incidence in the US states. We also acknowledge Jonathan Pekar, Joel Wertheim, and Michael Worobey for sharing their estimates on COVID-19 incidence in late 2019 and early 2020. We finally acknowledge Michael McLaren, Becky Ward, and Quincey Justman for feedback on the manuscript.

Funding:

Lynch Foundation Fellows Program in Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School (ABL)

National Library of Medicine grant T15LM007092 (DL)

National Institutes of Health grant R01GM120122 (APJ)

CDC contract 200-2016-91779 (WPH)

National Institutes of Health grant R01GM120122 (MS)

This project has been funded (in part) by contract 200-2016-91779 with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclaimer: The findings, conclusions, and views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Footnotes

Competing interests: WPH is a member of the scientific advisory board and has stock options in BioBot Analytics. MS is a cofounder of Rhinostics and consults for the diagnostic consulting company Vectis Solutions LLC. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Code availability: Code is available at https://github.com/abliu/early-detection/releases.

Data availability:

Data are available in the supplement and at https://github.com/abliu/early-detection/releases.

References

- 1.Kraemer M. U. G. et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 368, 493–497 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyerowitz-Katz G. et al. Is the cure really worse than the disease? The health impacts of lockdowns during COVID-19. BMJ Global Health 6, e006653 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamey G. & Walensky R. P. Covid-19: Re-opening universities is high risk. BMJ 370, m3365 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauner J. M. et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science 371, eabd9338 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson N. M. et al. Report 9 - Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/departments/school-public-health/infectious-disease-epidemiology/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19/ (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Levine-Tiefenbrun M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR Test Detection Rates Are Associated with Patient Age, Sex, and Time since Diagnosis. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 24, 112–119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larremore D. B. et al. Test sensitivity is secondary to frequency and turnaround time for COVID-19 screening. Science Advances eabd5393 (2020) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu A. B. et al. Association of COVID-19 Quarantine Duration and Postquarantine Transmission Risk in 4 University Cohorts. JAMA Network Open 5, e220088 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyllie A. L. et al. Saliva or Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 1283–1286 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yelin I. et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 RT-qPCR Test in Multi sample Pools. Clinical Infectious Diseases 71, 2073–2078 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karin O. et al. Cyclic exit strategies to suppress COVID-19 and allow economic activity. (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20053579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaxman S. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 584, 257–261 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatchett R. J., Mecher C. E. & Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 7582–7587 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peak C. M., Childs L. M., Grad Y. H. & Buckee C. O. Comparing nonpharmaceutical interventions for containing emerging epidemics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 4023–4028 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei S., Kandula S. & Shaman J. Differential effects of intervention timing on COVID-19 spread in the United States. Science Advances 6, eabd6370 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body, World Health Organization. Conceptual zero draft for the consideration of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body at its third meeting. 32 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lander E. & Sullivan J. American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming Our Capabilities. 27 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botti-Lodovico Y. et al. The Origins and Future of Sentinel: An Early-Warning System for Pandemic Preemption and Response. Viruses 13, 1605 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ecker D. J. How to Snuff Out the Next Pandemic. Scientific American Blog Network (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peccia J. et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nature Biotechnology 38, 1164–1167 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Nucleic Acid Observatory Consortium. A Global Nucleic Acid Observatory for Biodefense and Planetary Health. arXiv:2108.02678 [q-bio] (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjelmsø M. H. et al. Metagenomic analysis of viruses in toilet waste from long distance flights—A new procedure for global infectious disease surveillance. PLOS ONE 14, e0210368 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muntean J., Howard K. & Atwood P. CDC has tested wastewater from aircraft amid concerns over Covid-19 surge in China. CNN (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordahl Petersen T. et al. Meta-genomic analysis of toilet waste from long distance flights; a step towards global surveillance of infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. Scientific Reports 5, 11444 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mina M. J. et al. A Global Immunological Observatory to meet a time of pandemics. eLife 9, e58989 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu H. Y. et al. Early Detection of Covid-19 through a Citywide Pandemic Surveillance Platform. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 185–187 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brownstein J. S., Freifeld C. C. & Madoff L. C. Digital Disease Detection — Harnessing the Web for Public Health Surveillance. The New England journal of medicine 360, 2153–2157 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dugas A. F. et al. Influenza Forecasting with Google Flu Trends. PLOS ONE 8, e56176 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajema N., Beaver W. & Parthemore C. Toward a Global Pathogen Early Warning System: Building on the Landscape of Biosurveillance Today. https://councilonstrategicrisks.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Toward-A-Global-Pathogen-Early-Warning-System_2021_07_20-1.pdf (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee V. J., Chiew C. J. & Khong W. X. Interrupting transmission of COVID-19: Lessons from containment efforts in Singapore. Journal of Travel Medicine 27, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keshaviah A. et al. Wastewater monitoring can anchor global disease surveillance systems. The Lancet Global Health 11, e976–e981 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petros B. A. et al. Multimodal surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 at a university enables development of a robust outbreak response framework. Med 0, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boehm A. B. et al. Regional Replacement of SARS-CoV-2 Variant Omicron BA.1 with BA.2 as Observed through Wastewater Surveillance. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 9, 575–580 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J. E., Lee J. H., Lee H., Moon S. J. & Nam E. W. COVID-19 screening center models in South Korea. Journal of Public Health Policy 42, 15–26 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meakin S. et al. Comparative assessment of methods for short-term forecasts of COVID-19 hospital admissions in England at the local level. BMC Medicine 20, 86 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arizti-Sanz J. et al. Streamlined inactivation, amplification, and Cas13-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Communications 11, 5921 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregory D. A., Wieberg C. G., Wenzel J., Lin C.-H. & Johnson M. C. Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 Populations in Wastewater by Amplicon Sequencing and Using the Novel Program SAM Refiner. Viruses 13, 1647 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C. et al. Population Normalization in SARS-CoV-2 Wastewater-Based Epidemiology: Implications from Statewide Wastewater Monitoring in Missouri. (2022) doi: 10.1101/2022.09.08.22279459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson C. A. et al. Defining biological and biophysical properties of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in wastewater. Science of The Total Environment 807, 150786 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bibby K. & Peccia J. Identification of Viral Pathogen Diversity in Sewage Sludge by Metagenome Analysis. Environmental Science & Technology 47, 1945–1951 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creager H. M. et al. Clinical evaluation of the BioFire® Respiratory Panel 2.1 and detection of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Clinical Virology 129, 104538 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edin A., Eilers H. & Allard A. Evaluation of the Biofire Filmarray Pneumonia panel plus for lower respiratory tract infections. Infectious Diseases 52, 479–488 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy C. N. et al. Multicenter Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia/Pneumonia Plus Panel for Detection and Quantification of Agents of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 58, e00128–20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quick J. et al. Multiplex PCR method for MinION and Illumina sequencing of Zika and other virus genomes directly from clinical samples. Nature Protocols 12, 1261–1276 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ackerman C. M. et al. Massively multiplexed nucleic acid detection with Cas13. Nature 582, 277–282 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu C. Y. & Miller S. A. Clinical metagenomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 20, 341–355 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bar-On Y. M., Sender R., Flamholz A. I., Phillips R. & Milo R. A quantitative compendium of COVID-19 epidemiology. arXiv:2006.01283 [q-bio] (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du Z. et al. Reproduction number of monkeypox in the early stage of the 2022 multi-country outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine taac099 (2022) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taac099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). United States confirmed as country with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus. CDC (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradshaw W. J., Alley E. C., Huggins J. H., Lloyd A. L. & Esvelt K. M. Bidirectional contact tracing could dramatically improve COVID-19 control. Nature Communications 12, 232 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hellewell J. et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health 8, e488–e496 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lloyd-Smith J. O., Schreiber S. J., Kopp P. E. & Getz W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu F. et al. Wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 across 40 U.S. States from February to June 2020. Water Research 202, 117400 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu F. S. et al. Estimating the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 in the United States using influenza surveillance, virologic testing, and mortality data: Four complementary approaches. PLOS Computational Biology 17, e1008994 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abbott S. et al. Epiforecasts/EpiNow2: 1.3.4 release. (2023) doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7611804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pekar J. E. et al. The molecular epidemiology of multiple zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2. Science 377, 960–966 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. MWRA - Wastewater COVID-19 Tracking. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adhikari S. & Halden R. U. Opportunities and limits of wastewater-based epidemiology for tracking global health and attainment of UN sustainable development goals. Environment International 163, 107217 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sack K., Fink S., Belluck P. & Nossiter A. How Ebola Roared Back. The New York Times (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brouwer A. F. et al. Epidemiology of the silent polio outbreak in Rahat, Israel, based on modeling of environmental surveillance data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, E10625–E10633 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu F. et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentrations in wastewater foreshadow dynamics and clinical presentation of new COVID-19 cases. Science of The Total Environment 805, 150121 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soller J. et al. Modeling infection from SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentrations: Promise, limitations, and future directions. Journal of Water and Health 20, 1197–1211 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones D. L. et al. Shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in feces and urine and its potential role in person-to-person transmission and the environment-based spread of COVID-19. The Science of the Total Environment 749, 141364 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biobot Analytics. The Effect of Septic Systems on Wastewater-Based Epidemiology. http://biobot.io/wpcontent/uploads/2022/09/BIOBOT_WHITEPAPER_EFFECT_OF_SEPTIC_V01-1.pdf (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mallela A. et al. Bayesian Inference of State-Level COVID-19 Basic Reproduction Numbers across the United States. Viruses 14, 157 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldberg C. Mass. Public Health Lab Can Now Test For New Coronavirus, Speeding Results. (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pekar J., Worobey M., Moshiri N., Scheffler K. & Wertheim J. O. Timing the SARS-CoV-2 index case in Hubei province. Science 372, 412–417 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pekar J. E. et al. Sars-cov-2-origins / multi-introduction. GitHub (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yuan Yao, Yujie Ma, Jialu Zhou & Wenkun Hou. Xinhua Headlines: Chinese doctor recalls first encounter with mysterious virus - Xinhua English.news.cn. Xinhua (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 70.The 2019-nCoV Outbreak Joint Field Epidemiology Investigation Team & Li, Q. An Outbreak of NCIP (2019-nCoV) Infection in China — Wuhan, Hubei Province, 2019–2020. China CDC Weekly 2, 79–80 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenthal E. THE SARS EPIDEMIC: THE PATH; From China’s Provinces, a Crafty Germ Breaks Out. The New York Times (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garrett L. The Coming Plague. (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathieu E. et al. Total COVID-19 tests per 1,000 people. Our World in Data (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harris T. E. The theory of branching processes. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2009/R381.pdf (1964).

- 76.Yoo S. J. et al. Frequent Detection of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus in Stools of Hospitalized Patients. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 48, 2314–2315 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vetter P. et al. Ebola Virus Shedding and Transmission: Review of Current Evidence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 214, S177–S184 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Independent Evaluation Department, Asia Development Bank. People’s Republic of China: Wuhan Wastewater and Stormwater Management Project. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/evaluation-document/188852/files/pvr-447.pdf (2016).

- 79.Faes C. et al. Time between Symptom Onset, Hospitalisation and Recovery or Death: Statistical Analysis of Belgian COVID-19 Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 7560 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.He D. et al. Low dispersion in the infectiousness of COVID-19 cases implies difficulty in control. BMC Public Health 20, 1558 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang S. et al. Serial intervals and incubation periods of the monkeypox virus clades. Journal of Travel Medicine taac105 (2022) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taac105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.DeWitt M. E. et al. Global monkeypox case hospitalisation rates: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 54, 101710 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reda A., Hemmeda L., Brakat A. M., Sah R. & El-Qushayri A. E. The clinical manifestations and severity of the 2022 monkeypox outbreak among 4080 patients. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 50, 102456 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ryan E. T., Hill D. R., Solomon T., Aronson N. & Endy T. P. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases E-Book. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mailhe M. et al. Clinical characteristics of ambulatory and hospitalized patients with monkeypox virus infection: An observational cohort study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection (2022) doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tiwari A. et al. Monkeypox outbreak: Wastewater and environmental surveillance perspective. Science of The Total Environment 856, 159166 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolfe M. K. et al. Detection of monkeypox viral DNA in a routine wastewater monitoring program. (2022) doi: 10.1101/2022.07.25.22278043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics. Immunization. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization. Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 3 – Israel. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Estivariz Concepcion F., Link-Gelles Ruth & Shimabukuro Tom. Pinkbook: Poliomyelitis CDC. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nelson K. E. & Williams C. M. Determinants of Epidemic Growth. In Chapter 6: Infectious Disease Dynamics. in Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice 135 (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chung P. W., Huang Y. C., Chang L. Y., Lin T. Y. & Ning H. C. Duration of enterovirus shedding in stool. Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection 34, 167–170 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Onorato I. M. et al. Mucosal Immunity Induced by Enhanced-Potency Inactivated and Oral Polio Vaccines. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 163, 1–6 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wong Z. S. Y., Bui C. M., Chughtai A. A. & Macintyre C. R. A systematic review of early modelling studies of Ebola virus disease in West Africa. Epidemiology & Infection 145, 1069–1094 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Drake J. M. et al. Ebola Cases and Health System Demand in Liberia. PLOS Biology 13, e1002056 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Van Kerkhove M. D., Bento A. I., Mills H. L., Ferguson N. M. & Donnelly C. A. A review of epidemiological parameters from Ebola outbreaks to inform early public health decision-making. Scientific Data 2, 150019 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qureshi A. I. et al. High Survival Rates and Associated Factors Among Ebola Virus Disease Patients Hospitalized at Donka National Hospital, Conakry, Guinea. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Neurology 8, S4–S11 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fraser C. et al. Pandemic Potential of a Strain of Influenza A (H1N1): Early Findings. Science (New York, N.Y.) 324, 1557–1561 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heijnen L. & Medema G. Surveillance of Influenza A and the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in sewage and surface water in the Netherlands. Journal of Water and Health 9, 434–442 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Presanis A. M. et al. The Severity of Pandemic H1N1 Influenza in the United States, from April to July 2009: A Bayesian Analysis. PLOS Medicine 6, e1000207 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Furuya-Kanamori L. et al. Heterogeneous and Dynamic Prevalence of Asymptomatic Influenza Virus Infections. Emerging Infectious Diseases 22, 1052–1056 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lessler J., Reich N. G. & Cummings D. A. T. Outbreak of 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) at a New York City School. New England Journal of Medicine 361, 2628–2636 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Louie J. K. et al. Factors Associated With Death or Hospitalization Due to Pandemic 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Infection in California. JAMA 302, 1896–1902 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vynnycky E. & White R. An Introduction to Infectious Disease Modelling. (Oxford University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Morgan D. et al. HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: Is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries? AIDS (London, England) 16, 597–603 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Todd J. et al. Time from HIV seroconversion to death: A collaborative analysis of eight studies in six low and middle-income countries before highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 21, S55 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.CASCADE. Time from HIV-1 seroconversion to AIDS and death before widespread use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy: A collaborative re-analysis. Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival including the CASCADE EU Concerted Action. Concerted Action on SeroConversion to AIDS and Death in Europe. Lancet (London, England) 355, 1131–1137 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Crum-Cianflone N. F. HIV and the Gastrointestinal Tract. Infectious diseases in clinical practice (Baltimore, Md.) 18, 283–285 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yolken R. H., Li S., Perman J. & Viscidi R. Persistent Diarrhea and Fecal Shedding of Retroviral Nucleic Acids in Children Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 164, 61–66 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis (TB). (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 111.Behr M. A., Edelstein P. H. & Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis. The BMJ 362, k2738 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ma Y., Horsburgh C. R., White L. F. & Jenkins H. E. Quantifying TB transmission: A systematic review of reproduction number and serial interval estimates for tuberculosis. Epidemiology and Infection 146, 1478–1494 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the supplement and at https://github.com/abliu/early-detection/releases.