Summary

Sleep loss typically imposes negative effects on animal health. However, humans with a rare genetic mutation in the dec2 gene (dec2P384R) present an exception; these individuals sleep less without the usual effects associated with sleep deprivation. Thus, it has been suggested that the dec2P384R mutation activates compensatory mechanisms that allows these individuals to thrive with less sleep. To test this directly, we used a Drosophila model to study the effects of the dec2P384R mutation on animal health. Expression of human dec2P384R in fly sleep neurons was sufficient to mimic the short sleep phenotype and, remarkably, dec2P384R mutants lived significantly longer with improved health despite sleeping less. The improved physiological effects were enabled, in part, by enhanced mitochondrial fitness and upregulation of multiple stress response pathways. Moreover, we provide evidence that upregulation of pro-health pathways also contributes to the short sleep phenotype, and this phenomenon may extend to other pro-longevity models.

Introduction:

Sleep is an ancient behavior that is universally conserved among the animal kingdom 1. However, a high degree of variability exists in the amount of time different species spend sleeping 2. Some species, such as C. elegans, only sleep during critical developmental transitions or injury 3, while others, including many bat species, spend most of their life sleeping 2. Although work in the past few decades has led to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing sleep homeostasis 4–6, why organisms require a certain amount of sleep is still a fundamental mystery.

In most species, it is evident that sleep is important for maintaining physiological health as inadequate sleep correlates with numerous health issues, such as hypertension, heart disease, metabolic disorders, cognitive impairment, neurodegenerative diseases, and even premature mortality 7–16. Moreover, a bidirectional relationship between aging and sleep exists; aging correlates with increased sleep disturbances, while reduced sleep accelerates aging phenotypes 17,18. But, despite the strong link between sleep and maintaining cellular functions, there are rare examples of species that have adapted to cope with much less sleep compared to physiologically similar counterparts 2,19. A striking example are populations of cavefish that have evolved to sleep up to 80% less but maintain a similar lifespan as their surface fish ancestors 19. In recent years, natural short sleepers have even been identified in the human population that, despite sleeping less, do not exhibit adverse health issues that are typically associated with sleep deprivation. These examples hint that some organisms may have adapted reduced sleep requirements and that perhaps ectopically inducing pro-health mechanisms can influence the amount of daily sleep an organism needs. Understanding how these exceptional individuals compensate for less sleep may reveal unique strategies that can sustain health in sleep-deprived states as well as promote more general health.

One of the most well-studied examples of natural short sleepers in the human population are individuals with rare genetic mutations in the dec2 gene 20. Dec2 is a transcriptional repressor that, in mammals, is recruited to the prepro-orexin promoter and represses the expression of orexin, a neuropeptide that promotes wakefulness 20–22. A single point mutation in dec2 (dec2P384R) inhibits the ability of Dec2 to bind the prepro-orexin promoter, resulting in increased orexin expression 22. Consequently, wakefulness increases, and individuals sleep on average 6hrs/day instead of 8hrs/day 20,22. Intriguingly, these natural short sleepers do not appear to exhibit any phenotypes typically associated with chronic sleep deprivation, and expression of the dec2P384R mutation in mice suppresses neurodegeneration 23–25. Thus, it has been suggested that individuals harboring the dec2P384R mutation may employ compensatory mechanisms that allow them to thrive with chronic sleep loss. However, whether the dec2P384R mutation directly confers global health benefits has not yet been tested experimentally in any system.

In this study, we used a Drosophila model to understand the role of the dec2P384R mutation on animal health and elucidate the mechanisms driving these physiological changes. We found that the expression of the mammalian dec2P384R transgene in fly sleep neurons was sufficient to mimic the short sleep phenotype observed in mammals. Remarkably, dec2P384R mutants lived significantly longer with improved health despite sleeping less. In particular, dec2P384R mutants were more stress resistant and displayed improved mitochondrial fitness in flight muscles. Differential gene expression analyses further revealed several altered transcriptional pathways related to stress response, including detoxification and xenobiotic stress pathways, that we demonstrate collectively contribute to the increased lifespan and improved health of dec2P384R mutants. Finally, we provide evidence that the short sleep phenotype observed in dec2P384R mutants may be a result of their improved health rather than altered core sleep programs. Taken together, our results highlight the dec2P384R mutation as a novel pro-longevity factor and suggest a link between pro-health pathways and reduced sleep pressure.

Methods:

Fly strains and rearing conditions

Fly stocks were raised at 25°C with 12:12h L:D cycle and fed on a standard cornmeal molasses medium. The following fly strains were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC): GR23E10-gal4 (49032), UAS-dec2WT (64227), UAS-dec2P384R (64228), AMPKα (32108), UASp-foxo (42221), col4a1-gal4 (7011), and elav-gal4 (8760). The following RNAi lines were obtained from Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC): mtnBi (106118), mtnCi (35816), mtnDi (330619), CG11699i (101491), nmdmci (110198).

Generating LexAop-dec2 transgenic strains

The human dec2 genes were PCR-amplified from dec2WT and dec2P384R transgenic strains using the following primers:5’-GGGGACAACTTTGTATACAAAAGTTGTAATGGACGAAGGAATTCCTCATTTGC-3’ and 5’-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTATCAGGGAGCTTCCTTTCCTGGCTGC-3’. dec2WT and dec2P384R transgenes were subsequently cloned into the pDONR P5-P2 Gateway vector (Invitrogen) using BP clonase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 11789020), to generate pENTR L5-dec2WT-L2 and pENTR L5-dec2P384R-L2, and the inserts were validated via DNA sequencing. pENTR L5-dec2WT-L2 and pENTR L5-dec2P384R-L2 plasmids were then individually combined with pENTR L1–13XLexAop2-R5 (Addgene #41433; 26) and destination vector pDESTsvaw (Addgene #32318; 26) using LR clonase (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat#12538120). The pDESTsvaw vectors contains a mini-white rescue gene to enable transgenic selection and an attB site to enable PhiC31-mediated site-specific integration. Injection services of Genetivision (Houston, TX) were used to insert transgenes at the vk27: (3r) 89e11 site using phiC31-mediated insertion. Transgenic lines were maintained over the 3rd chromosome balancer TM6B using standard genetic crossing procedures.

Sleep Analyses

Sleep analyses were performed using a Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (DAMS) from Trikinetics (Waltham, MA). In flies, sleep is defined as a quiescent period of five mins or longer 27. Male flies (7–10 days old) were loaded in 5 × 65 mm glass tubes with food on one side and were allowed to acclimate for approximately 24 hrs. Baseline sleep was measured as bouts of 5 min of rest and was recorded for 5 days. During the analysis, flies were subjected to a 12:12h L:D cycle in an incubator at 25° C. Sleep data was analyzed using ShinyR-DAM software 28. For sleep rebound, baseline sleep was recorded for 24h before flies were subjected to 24h of sleep deprivation using a sleep nullifying apparatus 29, which tilts asymmetrically from −60° to +60° angle to mechanically displace flies 10 times per min. Rebound sleep was then recorded for 24h post-deprivation.

Lifespan Assays

Adult Drosophila flies were collected within 24h of eclosion, transferred to fresh vials, and allowed to mate for 2–3 days to reach sexual maturity. Male flies were then isolated and transferred into fresh vials (20 flies per vial for a total of 6 vials). Lifespan experiments were conducted in an incubator with a controlled temperature of 25°C and a 12:12h L:D cycle. Flies were transferred into fresh vials every two days and dead flies were scored at the time of transfer. For lifespans under various stress conditions, 20 mM Paraquat, 12 μM Tunicamycin or 500 μM Rotenone was added directly to the food to induce oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, or mitochondrial stress, respectively. Lifespans under sleep deprivation stress was performed by using a Sleep Nullifying Apparatus (SNAP) 29. Statistical analyses were performed using OASIS software 30.

Memory assay

To test memory function, we used an Aversive Phototaxis Suppression Assay. This assay is based on the principle that flies are naturally attracted to light, except when an aversive odor (Quinine hydrochloride dihydrate, MP Biomedicals) is simultaneously present. For each experiment, ~20 adult male flies were transferred to an empty vial and starved for 6h before conducting the experiment to promote active foraging during the experiment. Before each experimental trial, flies were tested to determine whether they were positively phototaxic under normal conditions; flies were acclimated to the dark chamber for 30s, and flies that failed to migrate towards the light chamber after 25s were considered non-phototaxic and were censored from the experiment. For the remaining flies that were phototaxic, a filter paper soaked with quinine solution was inserted into the light chamber and 12 training trials were conducted. For each trial, flies were allowed 60s to migrate towards the light chamber. Flies that migrated towards the light chamber within 60s were scored as “Fail” and flies that stayed in the dark chamber scored as “Pass”. Immediately after 12 training trials, five test trials were performed to test short-term memory. In the test trials, the light chamber contained filter paper soaked with water. Flies that migrated towards the light chamber within 10s were scored as “Fail” and flies that remained in the dark chamber were scored as “Pass”. For long-term memory, the same flies were kept in vials with food for 4–5h before conducting five more test trials. For each test trial, the average pass rate for the five test trials was calculated for each individual fly.

RNA sequencing

For each replicate, ~70 whole flies of one week old were collected at ZT3, the time where there was most significant difference in their daytime sleep were used for RNA extraction. RNA extraction was done using standard a TRIzol TM reagent protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat# 15596018). Subsequently, genomic DNA was removed using a GeneJet RNA-purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat# K0702). The concentration of purified RNA was measured using a nanodrop and quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer. For each genotype, three independent biological replicates were sequenced.

For Illumina sequencing, at least 50 ng/μl of purified RNA for each replicate was sent to Novogene (Sacramento, CA) for cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing (Illumina NovaSeq 6000). For Nanopore sequencing, 10 μg of total RNA were diluted in 100 μl of nuclease-free water to prepare mRNA. Poly(A) RNA was separated using NEXTflex Poly(A) Beads (BIOO Scientific cat # NOVA-512980). Resulting poly(A) RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water and stored at −80°C. The quality of mRNA was assessed using a Bioanalyzer. 200 ng of input polyA + RNA was used to prepare cDNA libraries using a Direct cDNA sequencing kit (SQK-DCS109) and these were prepared according to the Oxford Nanopore recommended protocol. cDNA libraries were sequenced on a MinION using R9.4 flow cells.

Differential expression analyses

For the Nanopore reads, we mapped the reads to the reference genome using Minimap2 31 with arguments (p=80 and N=100) as described in 32. We then used Salmon 33 to quantify gene expression in alignment-based mode. For both the Illumina and Nanopore data, differential expression analysis among the 3 conditions (three biological replicates per condition) were performed using the DESeq2 34 R package (1.20.0). DESeq2 provides statistical routines for determining differential expression in digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and fold-change ≥ 1.5 found by DESeq2 were assigned as differentially expressed. We further analyzed the differentially expressed genes with enrichR 35 to look for enriched gene sets (adjusted p-value <= 0.05) with respect to KEGG 36 and Gene Ontology 37. The results from both the Illumina and Nanopore data were combined using the Flybase gene identifiers and the final summary files are provided as supplemental.

For the Illumina datasets, reads were mapped to a reference genome (r6.39) of Drosophila melanogaster 38 using HISAT2 39. We then used featureCounts v1.5.0-p3 40 to count the reads mapped to each gene and calculate FPKM.

qPCR methods

RNA was extracted from whole Drosophila animals and converted to cDNA using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, cat#1708891). Primers for qPCR were designed using IDT PrimerQuest (Table S1). Three experimental replicates per strain were analyzed and Actin was used as a housekeeping gene. qPCR was conducted using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific). qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 6 Real-Time PCR system. Data were analyzed using standard ΔCT method. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to estimate the relative changes in gene expression. Data were normalized to the WT control.

Mitochondrial respiratory capacity

OXPHOS and ET capacity of flight muscle homogenates was determined by high-resolution respirometry (Oroboros O2k; Innsbruck, Austria) as described previously 41. Briefly, flies (~5/biological replicates) aged 7–8 days were sedated by cold exposure at 4°C for 7–10 min. While sedated, thorax muscle was isolated from surrounding tissue and placed into ice-cold biopsy preservation solution 42. Thoraxes were then blotted dry, weighed, and placed into an ice-cold Dounce homogenizer containing mitochondrial respiration medium (MiR05) 42. Samples were homogenized for 20–30 seconds (7–9 strokes) and brought up to total volume with MiR05 (0.4 mg/mL final). Tissue homogenates were then transferred into an oxygraph chamber, containing 2 ml of MiR05, oxygenated to 600 μM, the chamber closed, and respiration was allowed to stabilize. Oxidative phosphorylated (OXPHOS) and electron transfer capacity was determined using the following concentrations of substrates, uncouplers and inhibitors: malate (2 mM), pyruvate (2.5 mM), ADP (2.5 mM), proline (5 mM), succinate (10 mM), glycerol-3-phosphate (15 mM), tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD, 0.5 μM), ascorbate (2 mM), carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 0.5 μM increment), rotenone (3.75 μM), atpenin A5 (1 μM), antimycin A (2.5 μM) and sodium azide (200 mM). Outer membrane integrity was confirmed by exogenous cytochrome c (7.5 μM).

Supercomplex formation

Mitochondrial respiratory chain super complexes were resolved by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) as described previously 43. Briefly, flight muscles (~50/biological replicates) were dissected, minced, and homogenized in ice cold isolation buffer. Following centrifugation, the mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer and stored at −80°C until time of assay. Pellets were resuspended in ddH2O containing sample buffer, digitonin (5%), and coomassie G-250. Samples were loaded into a 3–12% NativePAGE gel and resolved by electrophoresis. Gels were stained with colloidal blue, and bands were visualized using iBright™.

FAD Activity

FAD activity was determined colorimetrically by commercially available enzymatic assay (Abcam, ab204710). Isolated thorax muscles (~5/biological replicate) were deproteinated (Abcam, ab204708), homogenized in ice cold FAS assay buffer, and centrifuged at 4°C at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes to remove insoluble material. Data are expressed as nmols of activity per minute per mg protein.

Statistical analyses

Data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism. For two sample comparisons, an unpaired t-test was used to determine significance (α=0.05). For three or more samples, a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s, Tukey’s, or Šídák’s multiple comparisons was used to determine significance (α=0.05). For grouped comparisons, a two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons was used to determine significance (α=0.05). Statistical significance of lifespan data was determined using a log-rank test.

Results:

Expression of human dec2P384R in Drosophila sleep neurons reduces sleep and sleep rebound

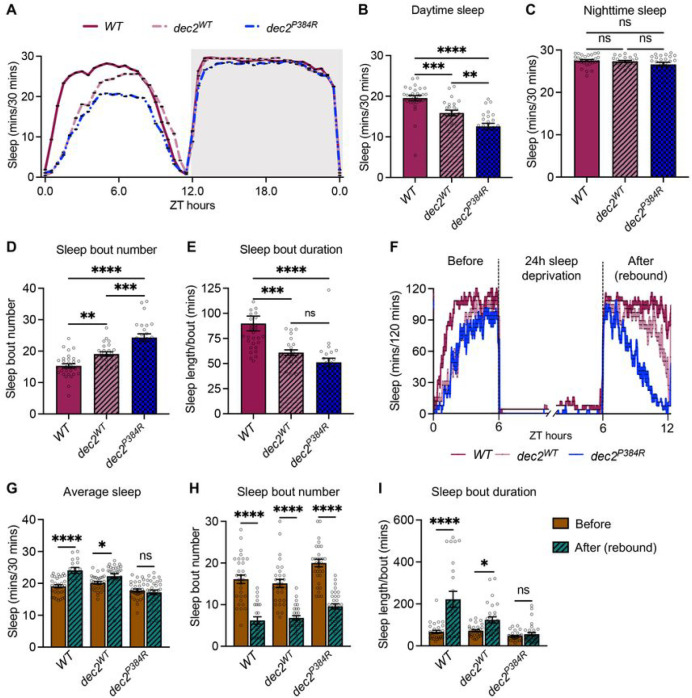

Many regulatory mechanisms of mammalian sleep, including diurnal sleep-wake cycles, sleep rebound, and circadian rhythms are conserved in Drosophila 27,44–46. These aspects, coupled with their relatively short lifespans and robust genetic toolkits, make Drosophila an excellent model system to study the relationship between sleep and age-related animal physiology. Previously, it has been demonstrated that over-expressing the human dec2P384R mutant transgene in the Drosophila mushroom body (MB) mimics the short sleep phenotype observed in humans with the mutation 20. Although the MB encompasses sleep-promoting neurons, it also includes additional neurons not related to sleep regulation 47. Since this study, gal4 drivers that express more specifically in sleep neurons have been developed and characterized, including GR23E10-gal4 48, which expresses in a subset of neurons projecting into the dorsal fan-shaped body (dFB), the sleep control center in Drosophila 49,50. Using the GR23E10-gal4 driver, we expressed human dec2P384R and dec2WT (as a control for dec2 over-expression) in Drosophila dFB sleep neurons and assessed the effect on sleep. Hereafter, WT refers to GR23E10-gal4/+ control, while dec2WT and dec2P384R refer to the respective dec2 transgenes over-expressed in GR23E10-gal4 specific neurons. Although no significant differences were observed during nighttime sleep between the three groups, dec2P384R mutant flies displayed significantly shorter daytime sleep compared to WT and dec2WT (Fig.1A–1C). Expression of dec2P384R also reduced the average sleep bout duration while concomitantly increasing the sleep bout number, (Fig. 1D and 1E), suggesting that sleep is less consolidated in dec2P384R mutants.

Figure 1: Expression of human dec2P3,iR in Drosophila sleep neurons reduces sleep and sleep rebound.

A. Sleep analysis in 12:12h L:D condition for WT (n=30), dec2WT (n=24), and dec2P384R (n=24) genotypes. B-C. Average sleep during daytime (B) and nighttime (C) of the genotypes indicated. D-E. Average sleep bout number (D) and sleep length/bout (E) in the genotypes indicated. ns=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. F. Sleep profiles for WT, dec2m and dec2P3S4R genotypes before and after 24 hrs of SD. WT before (n=32) and after SD (n=16); dec2WT before (n=31) and after SD (n=30); dec2P3a4R before (n= 32) and after SD (n=32). G. Average total sleep before and after SD for the genotypes indicated. H. Average sleep bout number before and after SD for the genotypes indicated. I. Average sleep length/bout before and after SD for the genotypes indicated. ns=not significant, *p<0.01, ****p<0.0001; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

Typically, aging is associated with deregulation of circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis leading to fragmented sleep patterns, short nocturnal sleep duration, and reduced slow-wave sleep 51. Because we observed fragmented sleep patterns in young dec2P384R mutants, we examined whether aging further impacted their sleep architecture. Consistent with previous studies, 60-day-old control flies showed more fragmented sleep compared to young flies (Fig. S1A-G). Specifically, sleep bout number increased by 148.5 % in old vs. young control flies (Fig. S1F). In dec2P384R mutants, sleep fragmentation also increased with age, albeit to a lesser degree (69.66 % increase in sleep bout number in old vs. young dec2P384R mutant flies). Nevertheless, these data indicate that dec2P384R mutants still exhibit age-dependent changes in sleep.

We also examined the effect of dec2P384R expression on sleep homeostasis, a regulatory mechanism that governs the timing and amount of sleep in a 24hr circadian period 52. Normally, sleep pressure, or the drive to sleep, increases when animals are awake and decreases as animals sleep. Moreover, sleep deprivation further elevates sleep pressure and promotes longer periods of sleep in the next cycle to compensate for prior sleep loss (i.e., sleep rebound) 44,53. To determine the effect of dec2P384R expression on sleep homeostasis, we examined the total amount of sleep recovery after 24 hours of sleep deprivation. Control flies displayed a typical increase in sleep in the immediate cycle following the deprivation; however, dec2P384R mutants resumed a sleep pattern that was not significantly different from the pre-deprivation state (Fig. 1F and 1G). Additionally, control flies also displayed longer sleep bout duration with fewer sleep bout number indicating more consolidated sleep after sleep deprivation, whereas dec2P384R mutants did not display a significant change in sleep consolidation (Fig. 1H and 1I). Thus, the dec2P384R mutation interferes with natural sleep homeostasis. Collectively, we have established a Drosophila dec2P384R model that mirrors the mammalian short sleep phenotype.

dec2P384R short sleep mutants live longer with improved health

In multiple animal models, complete loss of sleep decreases lifespan. For example, Drosophila sleepless mutants display 80% sleep loss and show a >50% reduction in lifespan 14. In humans, patients with a rare genetic disease called Fatal Familial Insomnia lose the ability to sleep around mid-life and only survive on average 18 months after diagnosis 15. In less severe instances, chronic sleep deprivation is associated with developmental disorders, cognitive impairments, metabolic dysfunctions, physiological deficits, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases 7,9–13,16,24,53,54. This prompted us to explore whether chronic reduced sleep in the dec2P384R mutants had any negative health impacts. Remarkably, we found that mutant dec2P384R flies lived significantly longer compared to control flies (Fig. 2A and Table S2). Thus, despite sleeping less, the dec2P384R mutation might in fact confer longevity to the organism.

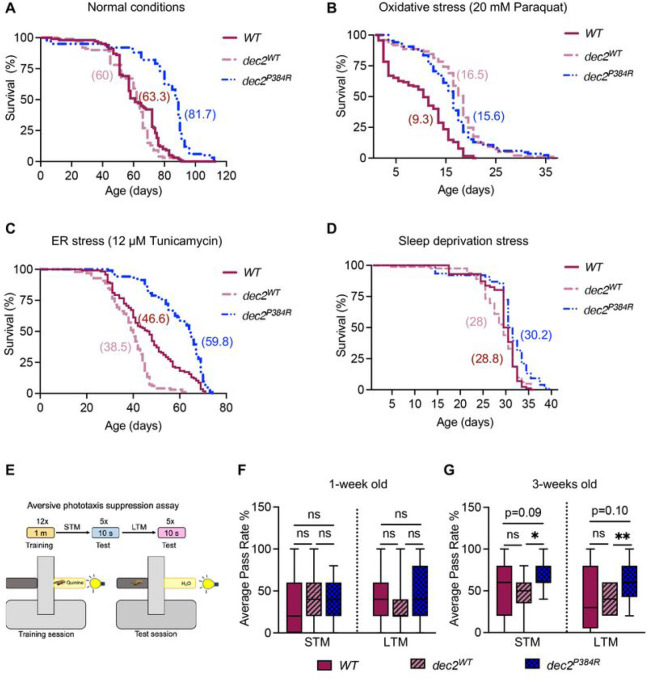

Figure 2: dec2P3B4R short sleep mutants live longer with improved health. A-D.

Lifespan analysis of WT, dec2WT and dec2P384R genotypes under normal conditions (A), fed 20 mM Paraquat to induce oxidative stress (B), 12 μM Tunicamycin to induce ER stress (C) or under sleep deprivation stress (D). See Table S2 for descriptive statistics and log-rank test results. E. Schematic of aversive phototaxis suppression assay. F-G. Aversive phototaxis suppression (APS) assay of WT, dec2WT and dec2P3B4R genotypes for short term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM) at one week (F) and three weeks (G) of age (n=21). Data for APS assay represented In box-and-whisker plots, with horizontal lines inside boxes indicating medians, box edges representing 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extending to minima and maxima. ns=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

To investigate whether dec2P384R mutants have improved physiology, we assessed health parameters that are often jeopardized with chronic sleep loss to determine if the dec2P384R mutation improves health. Sleep loss elevates the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to oxidative stress in mice and flies, and if prolonged, reduces lifespan 55. Similarly, sleep loss correlates with increased ER stress response pathways in mice 56–58 and Drosophila 44, suggesting that sleep loss leads to ER stress. Therefore, we examined survival under these two stressors. First, flies were fed Paraquat, an organic cation that models oxidative stress via NADPH-dependent production of superoxide, ROS 59. The lifespan of dec2P384R mutants was significantly longer than WT under oxidative stress conditions, indicating that dec2P384R mutants are resistant to oxidative stress (Fig. 2B and Table S2). Overexpression of dec2WT also improved survival under oxidative stress, suggesting that expression of the WT dec2 gene confers some resistance to oxidative stress as well. dec2P384R mutants also displayed increased resistance against the ER stressor, Tunicamycin, which inhibits protein glycosylation in the ER, leading to accumulated unfolded proteins 60,61 (Fig. 2C and Table S2). Additionally, we examined the sensitivity of dec2P384R mutant flies to sleep deprivation. Using the Sleep Nullifying Apparatus (SNAP) 29, flies were subjected to constant mechanical sleep deprivation and their lifespan was recorded. Consistent with increased stress resistance, dec2P384R mutants lived significantly longer than WT and dec2WT under sleep deprivation conditions (Fig. 2D and Table S2).

Sleep deprivation has also been linked to poor memory consolidation; in flies, 6–12 hours of sleep deprivation is sufficient to cause learning impairment 62. This suggests that altered sleep architecture can negatively impact memory encoding. Therefore, we examined whether dec2P384R mutants displayed significant memory impairment in either early- and/or mid-age by performing an aversive phototaxis suppression (APS) assay (Fig. 2E), which is commonly used to assess short and long-term memory in Drosophila 63,64. At one-week of age, there was no significant difference among mutants and controls (Fig. 2F). However, at three weeks of age (mid-life), dec2P384R mutants displayed significantly improved short and long-term memory compared to both control groups (Fig. 2G). Thus, mid-life memory function of dec2P384R mutants is in fact improved. Collectively, these data indicate that dec2P384R mutants live longer with improved health, despite sleeping less.

dec2P384R mutants exhibit improved mitochondrial capacity in flight muscles

Mitochondria are critical regulators of cellular energy and metabolism 65, and improving mitochondrial function, either via increasing respiratory capacity or increasing biogenesis, can extend lifespan 66–70. Moreover, clock rhythmicity determines energetic potential by signaling a need for reducing equivalents to drive oxidative phosphorylation (OXHPOS) 71,72. To determine if dec2P384R mutants display altered energy production, we first measured mitochondrial respiratory fluxes across the primary substrate-coupling pathways in homogenized flight muscles (Fig. 3A and 3B). dec2P384R mutants exhibited normal OXPHOS capacity supported by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) linked substrates, Proline and complex IV (Fig. 3C,3D and 3H). Strikingly, there was a significant increase in OXPHOS capacity supported by flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) linked substrates, namely succinate (61% vs. dec2WT, 81% vs. WT) and glycerol-3-phosphate (25% vs. dec2WT, 47% vs. WT) in dec2P384R relative to both WT and dec2WT flies (Fig. 3E–3G). Consistently, the FAD pool was also depleted in dec2P384R flies relative to both controls (Fig. 3I), indicative of decreased FAD/FADH2 ratio, favoring oxygen consumption and ATP synthesis. The increased respiratory flux observed in dec2P384R mutants was not attributed to a change in mitochondrial supercomplex structure and formation in dec2P384R and dec2WT flies (Fig. S2A); however, we found a significant decrease in citrate synthase activity, a marker of mitochondrial abundance, in dec2P384R flight muscles compared to controls (Fig. S2B). Thus, it is even more remarkable that dec2P384R mutants have improved mitochondrial capacity despite having less mitochondrial content. These data suggest that dec2P384R mutants exhibit improved mitochondrial respiratory function and ATP production capacity of substrates linked to reduction of FAD.

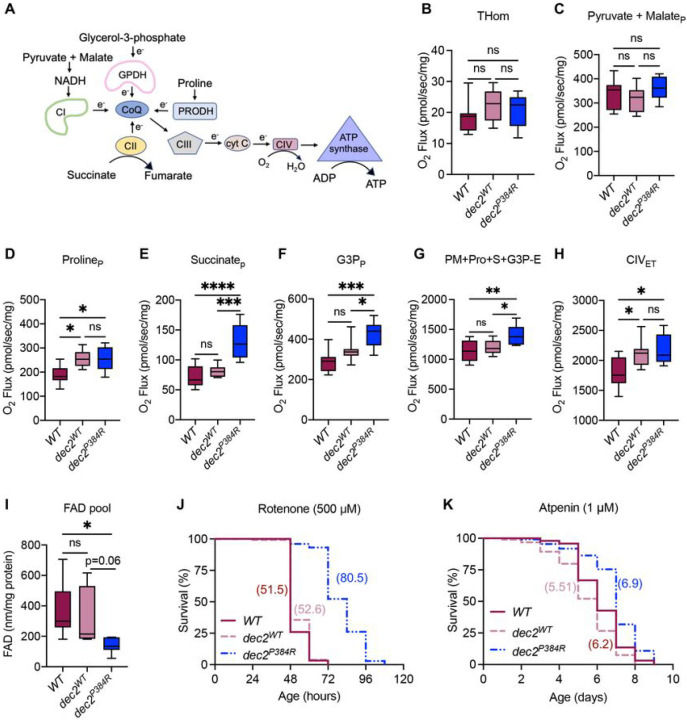

Figure 3: dec2P384R mutants exhibit improved mitochondrial capacity in flight muscles.

A. Schematic illustration of substrate coupling to mitochondrial respiratory pathways evaluated by high-resolution respirometry. B-G. Respiration supported by the indicated substrates in the presence of ADP for WT, dec2WT and dec2P3S4R genotypes (THom, tissue homogenate). H. Respiration supported by complex IV in the presence of FCCP (ET, electron transfer). I. FAD pool. Mitochondrial respiratory data represented in box-and-whisker plots, with horizontal lines inside boxes indicating medians, box edges representing 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extending to minima and maxima. ns=not significant, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. J-K. Lifespan of the genotypes indicated fed high doses of Rotenone (500 μM) (J) or Atpenin (1 μM) (K). See Table S2 for descriptive statistics and log-rank test results.

Based upon our observations that dec2P384R mutants display enhanced mitochondrial functional capacity, we tested resistance to stress induced by complex-specific OXPHOS inhibitors. We found that dec2P384R mutants survived significantly longer when fed high doses (500μM) of Rotenone (Fig. 3J and Table S2), a potent inhibitor of NADH oxidation and complex I activity. However, dec2P384R mutants fed high doses of the complex II inhibitor, Atpenin A5 (1μM) demonstrated a less pronounced improved survival (Fig. 3K and Table S2), consistent with dec2P384R mutants acting on FAD-linked substrate coupling. Taken together, these results indicate that dec2P384R mutants have increased FAD-linked mitochondrial respiratory capacity, which confers stress resistance and contributes to improved survival.

Multiple stress response genes are upregulated in dec2P384R mutants

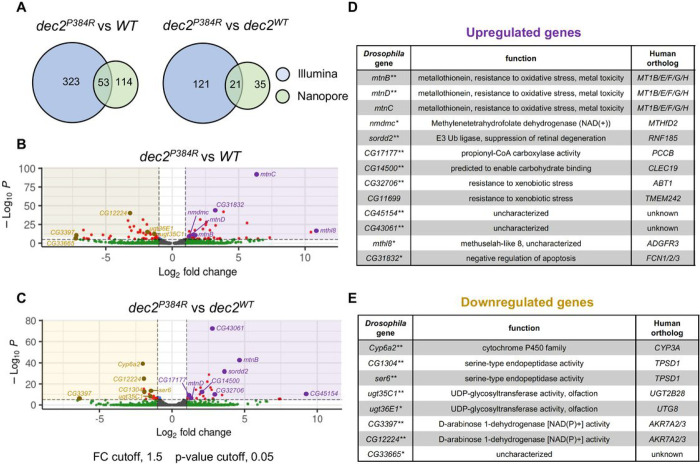

Given that Dec2 is a transcription factor, we hypothesized that the increased lifespan and improved health of dec2P384R mutants might be due to global changes in gene expression. To examine this possibility, we performed Illumina-based RNA-sequencing to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in dec2P384R vs. WT and dec2WT flies. One week old flies were collected at ZT3, the time in which we observed the most significant difference in their daytime sleep (Fig. 1A), and RNA was extracted from whole animals for sequencing. In parallel, we also performed long-read sequencing using Nanopore technology, which enables whole transcript sequencing and can identify isoform variants and limits amplification biases 73. Significantly, the two analyses shared ~50% overlap in the DEGs identified (Fig. 4A), underscoring the confidence and reproducibility of our datasets. Principal component analyses were plotted to visualize the difference in gene expression among the three groups: WT, dec2WT and dec2P384R (Fig. S3A). The Illumina analyses obtained RNA-seq profiles for 17,972 genes with 323 DEGs in dec2P384R vs WT and 121 DEGs in dec2P384R vs dec2WT (Fig. 4B, 4C, and Table S3), while the long-read Nanopore sequencing obtained RNA-seq profiles for 15,488 genes with 136 DEGs in dec2P384R vs WT and 43 DEGs in dec2P384R vs dec2WT (Fig. S3B, S3C, and Table S4). To begin deciphering the molecular pathways that may be contributing to the improved health and extended lifespan of dec2P384R mutants, we performed gene ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses (Fig. S4A and S4B). Notably, multiple gene clusters related to stress resistance were upregulated in dec2P384R mutants (Fig. 4B–4D), which could account for the improved physiological health observed in dec2P384R mutants. Moreover, we identified several uncharacterized and orphan genes that were differentially expressed in dec2P384R mutants (Fig. 4B–4E), which could represent novel pro-longevity factors.

Figure 4: Multiple stress response genes are upregulated in dec2P384R mutants.

A. Venn diagrams comparing DEGs identified in lllumina and Nanopore analyses. B-C. Volcano plots of DEGs in dec2P384R vs. WT (B) and dec2P384R vs. dec2WT (C) identified in the lllumina analyses. Significantly down-regulated genes are on negative side (left), significantly up-regulated genes are on positive side (right). Cutoff ranges: log fold changes of −1.5 and +1.5; padj-value of 0.05. D-E. Table of upregulated (D) and downregulated (E) genes of interest, *identified in both lllumina and Nanopore analyses as a DEG in dec2P384R vs. WT, **identified in both lllumina and Nanopore analyses as a DEG in dec2P384R vs. dec2WT. See Tables S3 and S4 for full gene expression profiles obtain from the lllumina (Table S3) and Nanopore (Table S4) analyses.

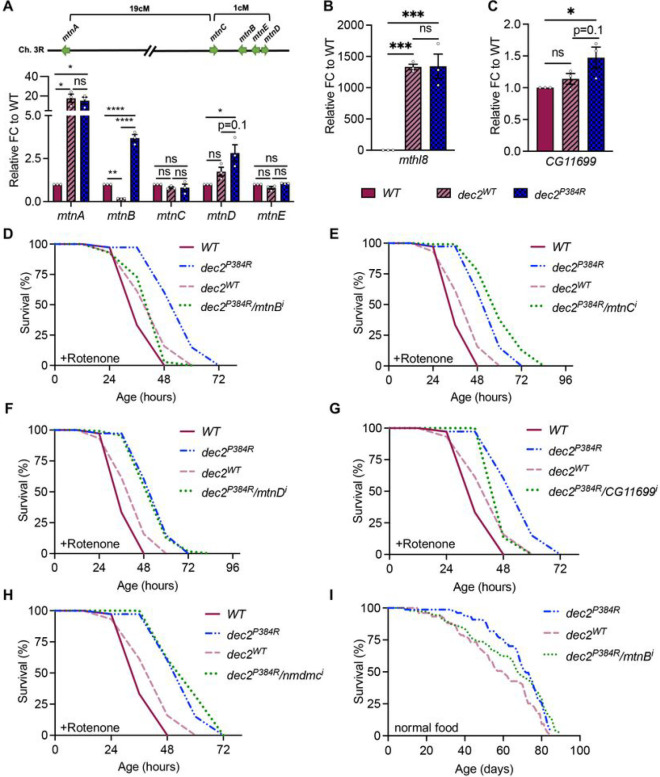

To validate the RNA-seq data, we selected the top ten upregulated genes as well as a subset of related gene family members to quantify expression by qPCR (Fig. 5A–5C and S5A-S5F). We first examined the metallothionein (MT) gene family, which consists of five paralogs (mtnA-E) that reside in a gene cluster on Ch. 3R (Fig. 5A). MT proteins have known cytoprotective functions and promote cell survival with increased expression 74–77. Consistent with the RNA-seq data, mtnB and mtnD transcripts were increased in dec2P384R compared to both controls (Fig. 5A). Methuselah-like 8 (mthl8) is an uncharacterized gene that is predicted to encode a G protein-coupled receptor 78 and was the most upregulated gene in dec2P384R vs WT in both Illumina and Nanopore datasets (Fig. 4B and S3B). Notably, a related homolog methuselah has been linked to lifespan regulation in flies 79. Strikingly, mthl8 transcripts measured by qPCR were increased >1000-fold in both dec2P384R and dec2WT compared to WT (Fig. 5B). Finally, we examined expression of CG11699, which was upregulated in dec2P384R compared to both controls; CG11699 transcripts were increased in dec2WT compared to WT and further upregulated in dec2P384R (Fig. 5C). Although CG11699 is not well-characterized, it has been linked to lifespan regulation; a transposable element insertion in the 3’UTR increases CG11699 expression and extends lifespan 80. CG11699 is also related to human TMEM242, a component of the mitochondrial proton-transporting ATP synthase complex 81. Overall, these results are consistent with the RNA-seq data and hint that multiple stress response pathways are upregulated in dec2P384R mutants.

Figure 5: Lifespan extension in dec2P384R mutants is dependent on increased mtnB expression.

A. Schematic of mtn gene cluster on Ch. 3R (top) and expression of mtn genes measured by qPCR (bottom). B-C. Expression of mthl8 (B) and CG11699 (C) measured by qPCR. FC=fold change, (n=3), ns=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s comparisons. D-H. Lifespan of flies fed 500 μM Rotenone. I. Lifespan of flies under normal conditions. See Table S2 for full descriptive statistics and results of log-rank tests.

Lifespan extension in dec2P384R mutants is dependent on increased mtnB expression

To identify which gene(s) are critical for regulating the lifespan extension of dec2P384R mutants, we examined whether inhibition of any of the top upregulated genes identified in the differential gene expression (DGE) analyses could negate the lifespan extension of dec2P384R mutants. To do this, we utilized two complementary binary expression systems, LexAop/LexA and UAS/GAL4, to simultaneously express dec2P384R in sleep neurons and inhibit candidate gene expression via RNAi in various tissues, respectively. We first tested whether the GR23E10-lexA/lexAop-dec2P384R transgenic expression system induced a short-sleep phenotype like the GAL4/UAS system and, indeed, we observed a similar short sleep phenotype when dec2P384R was expressed using the LexA/LexAop system (Fig. S6A-S6E).

GR23E10-lexA/lexAop-dec2P384R transgenic flies were also resistant to Rotenone (Fig. 5D and Table S2) but still do not survive for more than three days. Therefore, we performed lifespans in the presence of Rotenone as a faster means of screening through candidate genes initially. We first examined the MT gene family mtnA-E. Upregulation of MT genes in neurons promotes longevity 82; thus, we used the pan-neuronal driver elav-gal4 to inhibit MT gene expression in the brain of dec2P384R flies. Strikingly, inhibition of mtnB alone was sufficient to diminish the lifespan extension effect of dec2P384R mutants back to control lifespans (Fig. 5D and Table S2), while there was no significant difference in lifespan with suppression of mtnC or mtnD (Fig. 5E, 5F and Table S2). This is consistent with the DGE analyses, as mtnB was the most differentially expressed MT gene compared to both WT and dec2WT controls (Fig. 4B and 4C). We next tested CG11699 and nmdmc by inhibiting their expression ubiquitously using tubulin-gal4 (tub-gal4). However, we did not obtain any viable progeny, suggesting that global inhibition of these genes is lethal. We then inhibited CG11699 or nmdmc in neurons using elav-gal4. Inhibiting CG11699 in dec2P384R mutants reduced the lifespan back to WT (Fig. 5G and Table S2), while there was no reduction in lifespan with nmdmc gene suppression (Fig. 5H and Table S2). Finally, we examined whether mtnB is required for dec2P384R mutant lifespan extension under normal conditions and found that inhibition of mtnB also partially reduced the lifespan of dec2P384R mutants under normal conditions (Fig. 5I and Table S2); thus, mtnB expression in neurons significantly contributes to the lifespan extending effects of dec2P384R expression. Collectively, we have identified at least two critical factors that are required for the lifespan extending effects of dec2P384R mutants and these data reinforce that the lifespan extension observed in dec2P384R is a result of increased expression of stress-response signaling pathways.

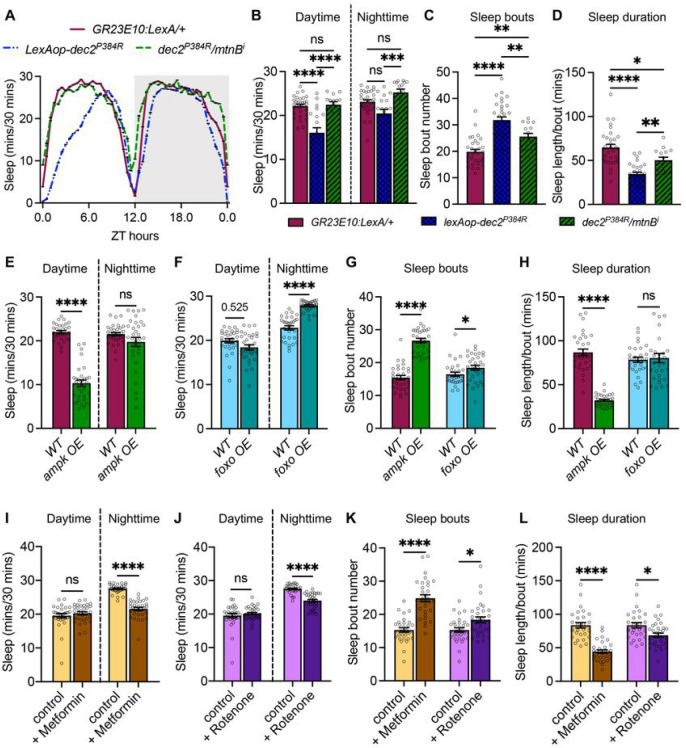

Improved health correlates with reduced sleep

Although the dec2P384R mutation is known to promote prolonged wakefulness by increasing orexin expression in mammals 22, it is puzzling that over-expression of mammalian dec2P384R in Drosophila can still induce a short-sleep phenotype given that the orexin system does not exist in invertebrates 83. This suggests that dec2P384R is capable of reducing sleep by an orexin-independent mechanism. This led us to postulate that perhaps the dec2P384R-dependent short sleep phenotype is not directly related to altered core sleep mechanisms, but rather a byproduct of their increased longevity. Based on this idea, we hypothesized that inhibiting the pro-health pathways triggered by Dec2P384R would reverse the short sleep phenotype. Thus, we inhibited mtnB pan-neuronally in dec2P384R mutants, which reduces the lifespan of dec2P384R mutants back to WT (Fig. 5I), and assessed their sleep length. In accord with our hypothesis, we found that mtnB inhibition increased sleep of dec2P384R mutants back to WT levels (Fig. 6A–6B). Moreover, inhibition of mtnB also suppressed the sleep fragmentation phenotype of dec2P384R mutants (Fig. 6C–6D). Thus, these data suggest that the improved health of dec2P384R mutants may also contribute to the short sleep phenotype.

Figure 6: Improved health correlates with reduced sleep.

A. Sleep analysis in 12:12h L:D condition for GR23E10:LexA/+ (n=32), lexAop-dec2P3S4R (n=20) and dec2P384R /mtnBi genotypes (n=15). B-D. Average daytime sleep and nighttime sleep (B), sleep bout number (C) and sleep length/bout (D) for the genotypes indicated (ns=not significant. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). E-F. Average daytime sleep and nighttime sleep for long-lived mutants ampk OE (n=32) (E) and foxo OE (n=31) (F). G-H. Average sleep bout number (G) and sleep length/bout (H) for the long-lived mutants indicated. I-J. Average daytime and nighttime sleep for the long-lived models, 500 mM Metformin (n=31) (I) and 0.1 μM Rotenone (n=32) (J). K-L. Average sleep bout number (K) and sleep length/bout (L) for the long-lived models indicated (n=32), ns=not significant, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparisons.

Based on our result that reducing pro-health pathways in dec2P384R mutants reverses the short sleep phenotype, it is intriguing to speculate that improving organismal health may reduce sleep pressure. Although multiple studies have shown that aging correlates with increased sleep disturbances 17,18, how activation of pro-longevity pathways affects sleep has not been explored as extensively. However, in a study using a sleep inbred panel, in which flies were sorted based on their natural sleep time, short sleep flies displayed 16% longer lifespan compared to long sleep flies 84. Moreover, it has been demonstrated previously that reducing insulin signaling, which promotes longer lifespan 85, also reduces daytime sleep 86. Thus, there is compounding evidence to suggest that enhancing organismal health can reduce sleep pressure. We further explored this idea by assessing sleep in two other long-lived models: over-expression of AMPK pan-neuronally 87 and foxo in the fat body 85, both of which promote longer lifespan by inducing cell nonautonomous mechanisms. Consistent with our hypothesis, both long-lived models also exhibited reduced sleep (Fig. 6E and 6F). We also observed increased sleep fragmentation in both mutant models compared to controls (Fig. 6G and 6H). Interestingly, fat body overexpression of foxo displayed increased nighttime sleep, which is consistent with the previous observation that inhibiting insulin signaling reduces daytime sleep, but promotes a compensatory increase in nighttime sleep 86. However, we did not observe similar compensatory increases in nighttime sleep of AMPK or dec2P384R models, suggesting that sleep may be differentially influenced in these models. Nevertheless, these results lend further support to the notion that inducing pro-longevity pathways may reduce sleep pressure.

Finally, we tested whether non-genetic means of promoting health could also induce changes to sleep in WT animals. Administering low doses of mitochondria-targeted agents, such as Rotenone and Metformin, can improve health and extend lifespan by eliciting hormetic responses 88–94. Therefore, we examined sleep in WT flies that were fed 0.1 μM of Rotenone or 5 mM of Metformin, which are the optimal doses required for improved health span 88,93. Consistent with our model that improved health reduces sleep pressure, we observed reduced nighttime sleep and increased sleep fragmentation in WT flies fed either low doses of Metformin or Rotenone (Fig. 6I–6L). Taken together, these data lend support to the idea that improving health might reduce sleep need.

Discussion:

In this study we identified a familial natural short sleep mutation as a pro-longevity factor. While it has been suggested that human natural short sleepers are able to thrive with chronic short sleep, this has never been directly tested experimentally. Using a Drosophila model, we have demonstrated for the first time that expression of the short sleep mutation dec2P384R in fact extends lifespan and promotes healthy aging. Moreover, we identified metabolic adaptations and genetic pathways under the influence of neuronal Dec2 that contribute to the increased lifespan and stress resistance observed in dec2P384R mutants. Namely, multiple pathways related to metabolic and xenobiotic stress response pathways were upregulated. Recently, other familial natural short sleep (FNSS) mutations have been discovered in the human ADRB1, NPSR1, and GRM1 genes 95,96. Whether the paradigms we have established for the Dec2 mutation extend to these other FNSS mutations remains to be determined, but these studies provide a foundation for further investigation into potential links between natural short sleep mutations and health span.

Although there are likely multiple genes that collectively contribute to the lifespan extension of dec2P384R mutants, we found that increased expression of mtnB, a metallothionein protein, is one critical gene required for the full lifespan extension effects of dec2P384R mutants. Metallothionein proteins are small proteins that mediates cellular stress responses and are linked to longevity 97,98. Notably, increased expression of metallothionein results in resistance to mitochondrial induced stress and prevention of apoptotic signaling 82,97–99. This is consistent with our observations that dec2P384R mutants are resistant to mitochondrial inhibitors (Fig. 3J and 3K). We also observed upregulation of the CG11699 gene, which transcribes a protein that is not fully characterized. However, in flies, increased expression of CG11699 confers xenobiotic stress resistance through increased aldehyde dehydrogenase type III (ALDH-III) activity 80. ALDH oxidizes aldehydes to non-toxic carboxylic acids mitigating both intrinsic and pathological cellular stress, thus promoting overall survival 100. Additionally, a closely related human homolog of CG11699, TMEM242, is required for the assembly of the c-8 ring of human ATP synthase, which is essential for ATP production 81. Consistently, we found that dec2P384R mutants have increased mitochondrial respiratory capacity (Fig. 3A–3I). Specifically, we found improved FAD-linked capacity with a concomitant decrease in the FAD-pool, indicating an overall increase in FAD oxidation and ATP production. While increased FAD oxidation can also result in increased oxidative stress, we have found that the dec2P384R mutants are able to capitalize on the increased capacity while mitigating the potential deleterious effects of oxidative stress through upregulation of multiple stress-response mechanisms.

Our results also indicate that expressing the dec2P384R mutation in neurons alters cellular physiology in other non-neuronal tissues, such as muscles (Fig. 3). These data suggest that Dec2P384R triggers cellular responses in a cell non-autonomous manner to elicit systemic changes. How might this occur? Dec2 is a transcription factor that regulates multiple circadian genes 101, many of which are known to affect organismal health and survival. For example, inhibiting the C. elegans period ortholog lin-42 suppresses autophagy and accelerates aging 102. Likewise, null mutations in the Drosophila period ortholog reduce resistance to oxidative stress 103, while neuronal overexpression of period extends lifespan and confers stress resistance 104. Thus, upregulation of period improves health and extends lifespan. In mammals, per1 expression is activated by CLOCK/BMAL, which bind to an upstream E-box binding site to induce per1 transcription 105. WT DEC2 competes with CLOCK/BMAL at the E-box binding site, leading to repressed per1 expression 106; however, mutant DEC2P384R has reduced affinity to E-box promoter sequences 22. Thus, it is conceivable that Dec2P384R could lead to increased period expression in sleep neurons, which could subsequently trigger downstream cell non-autonomous physiological changes. Although we did not observe any significant changes to period transcripts in our RNA-seq data, the gene expression changes could be isolated to sleep neurons, which may have been precluded by our whole animal analysis. Examining transcriptional changes specifically in sleep neurons will be important future steps to identify direct targets of mutant Dec2P384R.

The Drosophila genome encodes a single gene, clockwork orange (cwo), that is orthologous to mammalian dec1 and dec2 107. Similar to DEC proteins, CWO also antagonizes CLOCK/BMAL transcription factors at an E-box site to attenuate period expression 108. Although CWO is structurally similar to Dec2, containing a basic helix-loop helix domain, there is less than 18% amino acid sequence similarity with Dec proteins, and the proline 384 residue is not conserved in the CWO protein. Thus, there are likely to be functional distinctions between the orthologs. Nevertheless, the fact that mammalian dec2P384R induces short sleep and impacts multiple aspects of physiology when expressed in flies, signifies that it is acting in a dominant negative fashion and could interfere with expression of endogenous CWO target genes. Alternatively, the proline mutation could produce a more dramatic structural alteration to Dec2, causing it to bind ectopic sites in the genome and alter transcription of non-native CWO target genes. Having a deeper understanding of endogenous Dec2 and CWO target genes, perhaps with a focus on non-circadian regulatory networks, will be important to decipher how dec2 orthologs and their variants influence non-sleep phenotypes.

Finally, our results also suggest that the improved health in dec2P384R mutants may also contribute to the short sleep phenotype. Typically sleep loss is associated with reduced health and lifespan 14,109,110; however, there is evidence to suggest that this may not always be the case. In a study using a sleep inbred panel in which flies were sorted based on their natural sleep time, short sleep flies lived significantly longer compared to flies that slept longer 84. This suggests that shorter sleep does not always strictly correlate with reduced lifespan. Moreover, this study and other previous studies 86 have demonstrated that multiple long-lived mutants also sleep less, which leads to an intriguing question: does promoting longevity reduce sleep need? The fact that some species evolved mechanisms to virtually eliminate the need for sleep, while maintaining a similar lifespan as related species that require sleep 19, lends support to this idea. Perhaps these species have naturally adapted sleep-independent pro-health mechanisms that allows them to survive with less sleep. This might also help explain why expression of the mammalian dec2P384R transgene can still induce a short sleep phenotype in flies, despite lacking an orexin ortholog. Thus, we hypothesize that the pro-health pathways that are ectopically induced in dec2P384R mutants may also contribute to the short sleep phenotype in flies. Whether similar mechanisms occur in mammals will be important future studies.

Sleep loss is becoming endemic in our modern society; it is estimated that 30% of adults in the U.S. sleep an average of 6hrs/night or less and are chronically sleep deprived 111,112. These sleep disturbances are becoming even more prevalent due to certain occupational, and lifestyle demands (i.e., shiftwork, cross time-zone travel). Thus, sleep loss has become a major public health concern and uncovering mechanisms that can sustain health in sleep-deprived states is of critical importance. Studying the genetic mechanisms regulated by these rare short sleep mutations could provide a unique opportunity to not only understand how these exceptional individuals offset the negative effects of sleep deprivation, but also uncover novel pro-longevity pathways that could be co-opted to sustain health in sleep-deprived states as well as promote health more generally.

Acknowledgements

We thank all lab members for critically reading the manuscript and providing helpful feedback.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM138116 to A.E.J.), the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center (U54GM104940 to J.P.K.), the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine (T32AT004094 to E.R.M.Z.) and an LSU Discover undergraduate research grant (to S.R.L.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Data Availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Additional information on data sources is available upon request from the corresponding author. All unique materials used in the study are available from the authors or from commercially available sources. For the gene expression analyses, the raw and processed data have been submitted to NCBI under the accession PRJNA957078. Data analysis code is available at github at https://github.com/pkerrwall/dec2_fly

References:

- 1.Keene A. C. & Duboue E. R. The origins and evolution of sleep. Journal of Experimental Biology 221, jeb159533 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S. S. & Tobler I. Animal sleep: a review of sleep duration across phylogeny. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 8, 269–300 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raizen D. M. et al. Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature 451, 569–572 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanini G. & Torterolo P. Sleep-wake neurobiology. Cannabinoids and Sleep, 65–82 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artiushin G. & Sehgal A. The Drosophila circuitry of sleep–wake regulation. Current opinion in neurobiology 44, 243–250 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borb A. A. & Achermann P. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. Journal of biological rhythms 14, 559–570 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cappuccio F. P., Cooper D., D’Elia L., Strazzullo P. & Miller M. A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European heart journal 32, 1484–1492 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwok C. S. et al. Self-reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association 7, e008552 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laaboub N. et al. Insomnia disorders are associated with increased cardiometabolic disturbances and death risks from cardiovascular diseases in psychiatric patients treated with weight-gain-inducing psychotropic drugs: results from a Swiss cohort. BMC psychiatry 22, 1–12 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sejbuk M., Mirończuk-Chodakowska I. & Witkowska A. M. Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors. Nutrients 14, 1912 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scullin M. K. & Bliwise D. L. Vol. 38 335–336 (Oxford University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhai L., Zhang H. & Zhang D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depression and anxiety 32, 664–670 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper D. G. et al. Differential circadian rhythm disturbances in men with Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal degeneration. Archives of general psychiatry 58, 353–360 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh K. et al. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science 321, 372–376 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medori R. et al. Fatal familial insomnia, a prion disease with a mutation at codon 178 of the prion protein gene. New England Journal of Medicine 326, 444–449 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzotti D. R. et al. Human longevity is associated with regular sleep patterns, maintenance of slow wave sleep, and favorable lipid profile. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 6, 134 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattis J. & Sehgal A. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and disorders of aging. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 27, 192–203 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Nobrega A. K. & Lyons L. C. Aging and the clock: Perspective from flies to humans. European Journal of Neuroscience 51, 454–481 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duboué E. R., Keene A. C. & Borowsky R. L. Evolutionary convergence on sleep loss in cavefish populations. Current biology 21, 671–676 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Y. et al. The transcriptional repressor DEC2 regulates sleep length in mammals. Science 325, 866–870 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganguly-Fitzgerald I., Donlea J. & Shaw P. J. Waking experience affects sleep need in Drosophila. Science 313, 1775–1781 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano A. et al. DEC2 modulates orexin expression and regulates sleep. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 3434–3439 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegrino R. et al. A novel BHLHE41 variant is associated with short sleep and resistance to sleep deprivation in humans. Sleep 37, 1327–1336 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gambetti P., Parchi P., Petersen R. B., Chen S. G. & Lugaresi E. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: clinical, pathological and molecular features. Brain pathology 5, 43–51 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong Q. et al. Familial natural short sleep mutations reduce Alzheimer pathology in mice. Iscience 25, 103964 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen L. K. & Stowers R. S. A Gateway MultiSite recombination cloning toolkit. PloS one 6, e24531 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendricks J. C. et al. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron 25, 129–138 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cichewicz K. & Hirsh J. ShinyR-DAM: a program analyzing Drosophila activity, sleep and circadian rhythms. Communications biology 1, 1–5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melnattur K., Morgan E., Duong V., Kalra A. & Shaw P. J. The Sleep Nullifying Apparatus: A Highly Efficient Method of Sleep Depriving Drosophila. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han S. K. et al. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget 7, 56147 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soneson C. et al. A comprehensive examination of Nanopore native RNA sequencing for characterization of complex transcriptomes. Nature communications 10, 1–14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patro R., Duggal G., Love M. I., Irizarry R. A. & Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nature methods 14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Love M. I., Anders S. & Huber W. Analyzing RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Bioconductor 2, 1–63 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen E. Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC bioinformatics 14, 1–14 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogata H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research 27, 29–34 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashburner M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature genetics 25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gramates L. S. et al. FlyBase: a guided tour of highlighted features. Genetics 220, iyac035 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pertea M., Kim D., Pertea G. M., Leek J. T. & Salzberg S. L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nature protocols 11, 1650–1667 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao Y., Smyth G. K. & Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wall J. M. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-engineered Drosophila knock-in models to study VCP diseases. Disease models & mechanisms 14, dmm048603 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doerrier C. et al. in Mitochondrial bioenergetics 31–70 (Springer, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jha P., Wang X. & Auwerx J. Analysis of mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). Current protocols in mouse biology 6, 1–14 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw P. J., Cirelli C., Greenspan R. J. & Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287, 1834–1837 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konopka R. J. & Benzer S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, 2112–2116 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dissel S. Drosophila as a model to study the relationship between sleep, plasticity, and memory. Frontiers in physiology 11, 533 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Modi M. N., Shuai Y. & Turner G. C. The Drosophila mushroom body: from architecture to algorithm in a learning circuit. Annual review of neuroscience 43, 465–484 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenett A. et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell reports 2, 991–1001 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donlea J. M., Thimgan M. S., Suzuki Y., Gottschalk L. & Shaw P. J. Inducing sleep by remote control facilitates memory consolidation in Drosophila. Science 332, 1571–1576 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pimentel D. et al. Operation of a homeostatic sleep switch. Nature 536, 333–337 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J., Vitiello M. V. & Gooneratne N. S. Sleep in normal aging. Sleep medicine clinics 13, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deboer T. Sleep homeostasis and the circadian clock: Do the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat influence each other’s functioning? Neurobiology of sleep and circadian rhythms 5, 68–77 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deboer T. Behavioral and electrophysiological correlates of sleep and sleep homeostasis. Sleep, Neuronal Plasticity and Brain Function, 1–24 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirmiran M. et al. Effects of experimental suppression of active (REM) sleep during early development upon adult brain and behavior in the rat. Developmental Brain Research 7, 277–286 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaccaro A. et al. Sleep loss can cause death through accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the gut. Cell 181, 1307–1328. e1315 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackiewicz M. et al. Macromolecule biosynthesis: a key function of sleep. Physiological genomics 31, 441–457 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naidoo N., Giang W., Galante R. J. & Pack A. I. Sleep deprivation induces the unfolded protein response in mouse cerebral cortex. Journal of neurochemistry 92, 1150–1157 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terao A. et al. Differential increase in the expression of heat shock protein family members during sleep deprivation and during sleep. Neuroscience 116, 187–200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cochemé H. M. & Murphy M. P. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. Journal of biological chemistry 283, 1786–1798 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bull V. H. & Thiede B. Proteome analysis of tunicamycin-induced ER stress. Electrophoresis 33, 1814–1823 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown M. K. et al. Aging induced endoplasmic reticulum stress alters sleep and sleep homeostasis. Neurobiology of aging 35, 1431–1441 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seugnet L., Suzuki Y., Vine L., Gottschalk L. & Shaw P. J. D1 receptor activation in the mushroom bodies rescues sleep-loss-induced learning impairments in Drosophila. Current Biology 18, 1110–1117 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seugnet L., Suzuki Y., Stidd R. & Shaw P. Aversive phototaxic suppression: evaluation of a short-term memory assay in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes, Brain and Behavior 8, 377–389 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ali Y. O., Escala W., Ruan K. & Zhai R. G. Assaying locomotor, learning, and memory deficits in Drosophila models of neurodegeneration. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments), e2504 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spinelli J. B. & Haigis M. C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nature cell biology 20, 745–754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferguson M., Mockett R. J., Shen Y., Orr W. C. & Sohal R. S. Age-associated decline in mitochondrial respiration and electron transport in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochemical Journal 390, 501–511 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ocampo A., Liu J., Schroeder E. A., Shadel G. S. & Barrientos A. Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast chronological life span and its extension by caloric restriction. Cell metabolism 16, 55–67 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nicholls D. Mitochondrial bioenergetics, aging, and aging-related disease. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2002, 12 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dillon L. M. et al. Increased mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle improves aging phenotypes in the mtDNA mutator mouse. Human molecular genetics 21, 2288–2297 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nisoli E. et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science 310, 314–317 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aguilar-López B. A., Moreno-Altamirano M. M. B., Dockrell H. M., Duchen M. R. & Sánchez-García F. J. Mitochondria: an integrative hub coordinating circadian rhythms, metabolism, the microbiome, and immunity. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 51 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masri S. et al. Circadian acetylome reveals regulation of mitochondrial metabolic pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 3339–3344 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y., Zhao Y., Bollas A., Wang Y. & Au K. F. Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications. Nature biotechnology 39, 1348–1365 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dutsch-Wicherek M., Sikora J. & Tomaszewska R. The possible biological role of metallothionein in apoptosis. Front Biosci 13, 4029–4038 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bakka A., Johnsen A., Endresen L. & Rugstad H. Radioresistance in cells with high content of metallothionein. Experientia 38, 381–383 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sato M. & Bremner I. Oxygen free radicals and metallothionein. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 14, 325–337 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iszard M. B., Liu J. & Klaassen C. D. Effect of several metallothionein inducers on oxidative stress defense mechanisms in rats. Toxicology 104, 25–33 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harmar A. J. Family-B G-protein-coupled receptors. Genome biology 2, 1–10 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin Y.-J., Seroude L. & Benzer S. Extended life-span and stress resistance in the Drosophila mutant methuselah. Science 282, 943–946 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mateo L., Ullastres A. & González J. A transposable element insertion confers xenobiotic resistance in Drosophila. PLoS genetics 10, e1004560 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carroll J., He J., Ding S., Fearnley I. M. & Walker J. E. TMEM70 and TMEM242 help to assemble the rotor ring of human ATP synthase and interact with assembly factors for complex I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bahadorani S., Mukai S., Egli D. & Hilliker A. J. Overexpression of metal-responsive transcription factor (MTF-1) in Drosophila melanogaster ameliorates life-span reductions associated with oxidative stress and metal toxicity. Neurobiology of aging 31, 1215–1226 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soya S. & Sakurai T. Evolution of orexin neuropeptide system: structure and function. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 691 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thompson J. B., Su O. O., Yang N. & Bauer J. H. Sleep-length differences are associated with altered longevity in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Biology open 9, bio054361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hwangbo D. S., Gersham B., Tu M.-P., Palmer M. & Tatar M. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature 429, 562–566 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Metaxakis A. et al. Lowered insulin signalling ameliorates age-related sleep fragmentation in Drosophila. PLoS biology 12, e1001824 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ulgherait M., Rana A., Rera M., Graniel J. & Walker D. W. AMPK modulates tissue and organismal aging in a non-cell-autonomous manner. Cell reports 8, 1767–1780 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmeisser S. et al. Neuronal ROS signaling rather than AMPK/sirtuin-mediated energy sensing links dietary restriction to lifespan extension. Molecular metabolism 2, 92–102 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Onken B. et al. Metformin treatment of diverse Caenorhabditis species reveals the importance of genetic background in longevity and healthspan extension outcomes. Aging cell 21, e13488 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Haes W. et al. Metformin promotes lifespan through mitohormesis via the peroxiredoxin PRDX-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, E2501–E2509 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martin-Montalvo A. et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nature communications 4, 2192 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Na H.-J. et al. Mechanism of metformin: inhibition of DNA damage and proliferative activity in Drosophila midgut stem cell. Mechanisms of ageing and development 134, 381–390 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Na H.-J. et al. Metformin inhibits age-related centrosome amplification in Drosophila midgut stem cells through AKT/TOR pathway. Mechanisms of ageing and development 149, 8–18 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuyun X. et al. Effects of low concentrations of rotenone upon mitohormesis in SH-SY5Y cells. Dose-response 11, dose-response. 12–005. Gao (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shi G. et al. Mutations in metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 contribute to natural short sleep trait. Current Biology 31, 13–24. e14 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xing L. et al. Mutant neuropeptide S receptor reduces sleep duration with preserved memory consolidation. Science translational medicine 11, eaax2014 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang X. et al. Metallothionein prolongs survival and antagonizes senescence-associated cardiomyocyte diastolic dysfunction: role of oxidative stress. The FASEB Journal 20, 1024–1026 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ebadi M. et al. Metallothionein-mediated neuroprotection in genetically engineered mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Molecular Brain Research 134, 67–75 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hands S. L., Mason R., Sajjad M. U., Giorgini F. & Wyttenbach A. (Portland Press Ltd., 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shortall K., Djeghader A., Magner E. & Soulimane T. Insights into aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes: a structural perspective. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 8, 659550 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sato F., Bhawal U. K., Yoshimura T. & Muragaki Y. DEC1 and DEC2 crosstalk between circadian rhythm and tumor progression. Journal of Cancer 7, 153 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kalfalah F. et al. Crosstalk of clock gene expression and autophagy in aging. Aging (Albany NY) 8, 1876 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Krishnan N., Kretzschmar D., Rakshit K., Chow E. & Giebultowicz J. M. The circadian clock gene period extends healthspan in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Aging (Albany NY) 1, 937 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Solovev I., Dobrovolskaya E., Shaposhnikov M., Sheptyakov M. & Moskalev A. Neuron-specific overexpression of core clock genes improves stress-resistance and extends lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Experimental gerontology 117, 61–71 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gekakis N. et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280, 1564–1569 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Honma S. et al. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature 419, 841–844 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kadener S., Stoleru D., McDonald M., Nawathean P. & Rosbash M. Clockwork Orange is a transcriptional repressor and a new Drosophila circadian pacemaker component. Genes & development 21, 1675–1686 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhou J., Yu W. & Hardin P. E. CLOCKWORK ORANGE enhances PERIOD mediated rhythms in transcriptional repression by antagonizing E-box binding by CLOCK-CYCLE. PLoS genetics 12, e1006430 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Spiegel K., Leproult R. & Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. The lancet 354, 1435–1439 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gonzalez-Ortiz M., Martinez-Abundis E., Balcazar-Munoz B. & Pascoe-Gonzalez S. Effect of sleep deprivation on insulin sensitivity and cortisol concentration in healthy subjects. Diabetes, nutrition & metabolism 13, 80–83 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schoenborn C. A. & Adams P. E. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. Vital Health Stat 10 245, 132 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sheehan C. M., Frochen S. E., Walsemann K. M. & Ailshire J. A. Are US adults reporting less sleep?: Findings from sleep duration trends in the National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. Sleep 42 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Additional information on data sources is available upon request from the corresponding author. All unique materials used in the study are available from the authors or from commercially available sources. For the gene expression analyses, the raw and processed data have been submitted to NCBI under the accession PRJNA957078. Data analysis code is available at github at https://github.com/pkerrwall/dec2_fly