Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the effects of CenteringPregnancy (CP) in the Netherlands on different health outcomes. A stepped wedged cluster randomized trial was used, including 2132 women of approximately 12 weeks of gestation, from thirteen primary care midwifery centres in and around Leiden, Netherlands. Data collection was done through self-administered questionnaires. Multilevel intention-to-treat analysis and propensity score matching for the entire group and separately for nulliparous- and multiparous women were employed. The main outcomes were: health behaviour, health literacy, psychological outcomes, health care use, and satisfaction with care. Women’s participation in CP is associated with lower alcohol consumption after birth (OR = 0.59, 95 %CI 0.42–0.84), greater consistency with norms for healthy eating and physical activity (β = 0.19, 95 %CI 0.02–0.37), and higher knowledge about pregnancy (β = 0.05, 95 %CI 0.01–0.08). Compared to the control group, nulliparous women who participating in CP reported better compliance to the norm for healthy eating and physical activity (β = 0.28, 95 %CI0.06–0.51)) and multiparous CP participants consumed less alcohol after giving birth (OR = 0.42, 95 %CI 0.23–0.78). Health care use and satisfaction rates were significantly higher among CP participants. A non-significant trend toward lower smoking rates was documented among CP participants. Overall, the results of this study reveal a positive (postpartum) impact on fostering healthy behaviours among participants.

Keywords: Group antenatal care, CenteringPregnancy, Perinatal health, Pregnancy, Propensity score

1. Introduction

A 2008 comparison of perinatal mortality rates in 26 European countries revealed that the Netherlands had the highest perinatal mortality rate of all included countries (Mohangoo et al., 2008). Health behaviours, low educational level, and insufficient use of antenatal care were, among others, identified as contributing factors (Mohangoo et al., 2008). To improve perinatal health, CenteringPregnancy (CP) -a group antenatal care (GANC) model developed in the USA- was implemented in 2012 in primary midwifery care organisations Rising, 1998, Rijnders et al., 2019). Antenatal care in the Netherlands traditionally consists of individual visits (Koster et al., 2015). With the implementation of CP, these visits have been replaced by group sessions (Rising, 1998, Rising et al., 2004), thereby providing healthcare workers more time with pregnant women and for them to engage in mutual learning and health education (Strickland et al., 2016). Internationally, CP is associated with positive maternal and neonatal outcomes (Ickovics et al., 2003, Ickovics et al., 2007, Jafari et al., 2010, Picklesimer et al., 2012, Sheeder et al., 2012, Tanner-Smith et al., 2013, Strickland et al., 2016, Cunningham et al., 2017, Ghani, 2018, Abshire et al., 2019, Adaji et al., 2019, Crockett et al., 2019). Moreover, CP has been related to greater satisfaction with antenatal care (Ickovics et al., 2007, Craswell et al., 2016), and a greater number of antenatal care visits (Eluwa et al., 2018, Abshire et al., 2019, Heberlein et al., 2020). A Dutch study revealed some positive effects of CP on neonatal and maternal outcomes, particularly on maternal hypertension (Wagijo et al., 2022); moreover there is also evidence of increased antenatal care visits and satisfaction (Rijnders et al., 2019).

Although CP includes peer-based strategies, which have been found to facilitate positive changes in health behaviour (Webel et al., 2010), only few studies have evaluated CP on improvement in health behaviours and the results have been inconclusive. A cross-sectional study found no differences in health behaviours (Shakespear et al., 2010), while other studies reported that women participating in CP scored significantly higher on the Pregnancy-relevant Health Behaviours scale (Marzouk et al., 2018) and self-reported behaviour (Hend Abdallah El Sayed, 2018). Zielinski et al., reported higher smoking cessation rates among CP participants compared to women receiving traditional care (Zielinski et al., 2014). However, Benediktsson et al., found no effect of CP on smoking cessation rates or even lower cessation rates when they compared CP participants to women in paid antenatal educational classes (Benediktsson et al., 2013). In addition, There is some evidence of the positive effects of GANC on knowledge about pregnancy issues, but there is less information on how group care influences lifestyle knowledge (Albrecht et al., 2000, Alm-Roijer et al., 2004, Cowell, 2006), (Baldwin, 2006, Ickovics et al., 2007, Byerley and Haas, 2017).

There is also some evidence that GANC can improve (postpartum) psychosocial outcomes in higher risk women (Ickovics et al., 2007, Benediktsson et al., 2013, Buultjens et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2021), but there is limited information for women visiting primary midwifery care who in general have a lower medical risk but can live in adverse psychosocial circumstances.

Considering this limited and inconclusive evidence, we conducted the current study to investigate the effect of CP on health behaviours, health literacy, psychosocial outcomes, and health care use and satisfaction of pregnant women in primary midwifery care.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and setting

The data for this study were extracted from the stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial described by Zwicht et al., and follows our previous research on CP (van Zwicht et al., 2016, Wagijo et al., 2022, Wagij et al., 2022). Participating healthcare facilities from the three regions included in this study offered only individual antenatal care before this study began. In November 2013 the control period started, followed by the intervention period in April 2014 with a stepwise implementation of CP in the included health care facilities. The timepoint for CP implementation was randomly assigned to each region using opaque envelopes; a between-step period of three months was used. All women attending antenatal care in the healthcare facilities were then offered CP but were also free to choose individual care (IC). Women provided written informed consent at their initial intake appointment.

The healthcare professionals, mostly midwives, working in the facilities received a two-day CP training and at least three follow-up supervision sessions, enabling them to discuss implementation barriers and practice facilitation skills. All healthcare facilities were visited by a CP consultant to discuss implementation issues and free consultations were available with the Dutch foundation for Centering-based Group Care to discuss any issue. All providers were invited to link to a platform where experiences could be shared with other care professionals who provided CP.

CP participants were offered a maximum of nine CP sessions during pregnancy and one session postpartum. Each session lasted approximately 120 min and took place in groups of 8–12 women. During the sessions, women received the same clinical assessments as in IC. All assessments took place in the group space and women were taught to perform several measurements themselves- for example: taking their own blood pressure. Healthcare professionals were present to assist and repeat measurements when there were deviant results. Each CP session focussed on a theme (lifestyle, birth, postpartum period, relationships, etc.), but emphasise varied depending on the needs of the group, and women were encouraged to bring up any topic.

2.2. Study population

Participants were recruited from 13 midwife practices and 2 hospitals in the area of Leiden/The Hague in the Netherlands. Women were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were able to understand the study and to communicate (with help) in Dutch or English. Current study only included the women that started their antenatal care in primary midwifery care. All women who completed the first questionnaire during the control period were assigned to the control group and to the intervention group if they completed it during the intervention period. The intervention group was further divided into the CP group (if they participated in CP) and IC group (if they chose individual care). The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee Leiden, The Hague and Delft (P13.105).

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected through three self-administered questionnaires during pregnancy and one questionnaire postpartum. Pseudonyms were used to protect the privacy of the participant and to link the data. The questionnaires consisted of 45 to 140 questions and it took 20–25 min to fill out. Women received the first questionnaire as a hard copy at their individual antenatal intake, usually at 8–12 weeks of gestation. This questionnaire was filled in at home and sent back to the researchers in pre-addressed, postage-paid envelopes. The follow-up questionnaires were sent by e-mail (with a link to the questionnaires) at 28 weeks, 36 weeks, and 6 weeks post-partum; if they did not respond after three reminders, researchers sent a hard copy by postal mail.

2.4. Sociodemographic characteristics

The age of the participants at the time of giving informed consent was calculated based on the date of birth. Level of education was categorized as low (no, primary or prevocational education), average (secondary education) and high (higher professional education or university). Ethnicity was defined as Dutch, non-Western (African, Surinamese, Hindustani, Moroccan, Turkish, and Asian) and other Western. Additionally having a partner and employment were included.

2.5. Health behaviour outcomes

Smoking behaviour and alcohol use were measured by self-reported frequencies, at 12, 28, and 36 weeks of pregnancy and 6 weeks post-partum. The questionnaire at 12 weeks included questions regarding smoking and alcohol use before pregnancy. Alcohol use during pregnancy was reported by 0.5% women. Therefore, only data of alcohol use before and after pregnancy were included in analysis.

Eating behaviour was measured by the number of days women consumed breakfast, fruits and vegetables during the past week at 12, 28 weeks of pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum. Women scored 1 when eating breakfast, fruits, and vegetables for seven days a week and otherwise scored 0; following the norm of the Health Council of the Netherlands (Kromhout et al., 2016). For physical activity, all women were asked how many days in the past week they exercised for at least 30 min, including going out for a walk or riding a bike. If women did not exercise at least five days, they were categorized as not complying to the healthy physical activity norm, with a score of 0. Beweegrichtlijnen (2017). The healthy eating and physical activity scores were summed in an overall healthy eating and physical activity score ranging from 0 to 4, with 0 referring to not complying with any of the eating or physical activity norms and 4 to complying to all norms. Gestational weight (in kilograms) was measured by self-reported weight at 12 weeks and 36 weeks of pregnancy.

2.6. Health literacy and psychosocial outcomes

Health behaviour knowledge and pregnancy knowledge were measured by a combination of questions from the nutrition test of the Dutch Nutrition Centre and the Prenatal and Postnatal Care Knowledge Test (Ickovics et al., 2007). Based on the number of right answers, women could score 0–5 points. Using the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (NuPDQ), a revised version of a 12-scale item developed by Yali and Lobel, stress among the women was measured (Yali and Lobel, 1999, Yali and Lobel, 2002, Alderdice et al., 2012). In addition, a concluding item to determine the perceived stress was added, in which women could grade their level of stress on a scale of 0.0 to 10.0.

Coping was evaluated with a 9-items instrument based on the revised Prenatal Coping Inventory (NuPCI) asking about the use of problem-focused, emotion-focused active, and emotion-focused passive coping in the last month (de Ridder and Schreurs, 1996, De Ridder et al., 1998, Savelkoul et al., 2000). The items were summed into one coping score ranging from 1 to 4: with 1 indicating not having used these strategies and 4 (very) often having used them (Hamilton and Lobel, 2008). Social support was measured with the social support list comprising 12 items (Bridges et al., 2002, van Sonderen and Sanderman, 2013) summed into a four-point scale outcome. Depression was measured with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Cox et al., 1987) and the outcome was dichotomized (cut-off point: 13.0).

2.7. Health care use and satisfaction

Health care use was measured by the number of antenatal visits during pregnancy with a midwife at the midwife practice and/or a gynaecologist at the hospital. Total obstetric care included both the visits to the gynaecologist and midwife, contacts by telephone, ultrasound appointments, and home visits. Other health care use refers to the number of appointments with other health professionals, e.g. the general practitioner, physiotherapist, etc.

Satisfaction of women with antenatal care was measured by the Patient Participation and Satisfaction questionnaire, on a five-point scale (Littlefield and Adams, 1987, Littlefield et al., 1990). In addition, satisfaction with care during pregnancy and satisfaction with care during birthing were both evaluated by the women with a self-reported grade between 0.0 and 10.0, with 10 being extremely satisfied.

Comprehensive and detailed information regarding the outcomes can be found in the protocol article of the study (van Zwicht et al., 2016).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics were compared between the women in the control group and intervention group and between control, intervention-IC and intervention-CP group, using Chi-square tests. Separate analyses were performed for nulli- and multiparous women, as previous research showed that pregnancy outcomes can be different between the two groups (Wheeler et al., 2018, Desplanches et al., 2019, Koullali et al., 2020) and higher CP participation rates among nulliparous women (Wagijo et al., 2022).

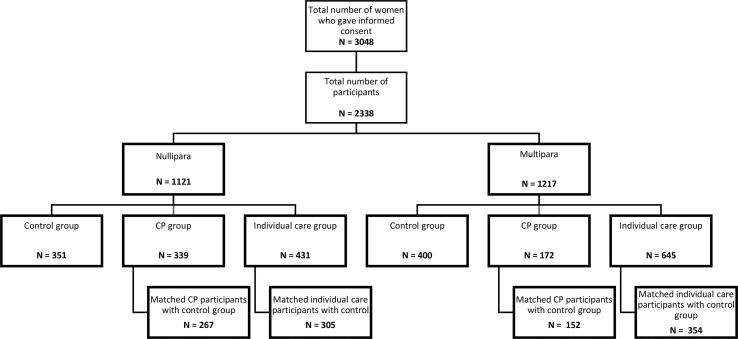

Multilevel logistic regression analyses were used to determine the difference between women in the control and intervention period for all variables, with a 95% CI. Clustering was by site and region. Next, propensity score matching was performed separately for the CP and IC intervention groups. Fig. 1 presents an overview of the number of women included in the study and in the propensity score groups. Propensity scores were calculated by matching women with similar scores to the following characteristics at baseline: level of education, ethnicity, age, alcohol use, smoking, dental hygiene, medication use, stress (due to pregnancy), eating behaviour, physical activity, lifestyle, and pregnancy knowledge, coping mechanisms, support, weight and healthcare use before pregnancy. Calipher matching was used.

Fig. 1.

Multilevel logistic and linear regression analyses were performed to compare women receiving CP in the intervention period (CP group) with a group of comparable women in the control period (CP-control group). Women receiving IC in the intervention period were compared with a group of comparable women in the control period (IC-control group). A correction for the timepoint of implementation of CP was used and analyses were first performed for both nulliparous and multiparous women and then separately.

To reduce bias due to missing data, multiple imputation was used to impute missing variables’ on the outcome variables (Jakobsen et al., 2017). We assumed missings were at random as we had insight in the properties of the missingness based on the questionnaire. The following variables were included in the imputation models: variables that we used as outcome, variables that were related to the missingness structure, and variables that were strong predictors for the variable we wanted to impute. We used 20 iterations as about 20 to 30% of the data was missing. Multiple imputed data sets were pooled using the bar procedure (Daniele, 2018).

The results of the analyses on the total group (nulliparous and multiparous women combined), before propensity score matching, are presented in the supplementary (S1 Table), as well as the results of the separate behaviours of the healthy eating and physical activity scale (after propensity score matching) (S2 Table).

For the propensity score matching, R Studio was used, and all other analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0.

3. Results

A total of 3048 women gave informed consent for the study, of which 710 women did not fill in the baseline questionnaire and were excluded from this study. Therefore, this study included 2338 women participated in this study: 751 women in the control and 1587 in the intervention period, with a CP participation rate of 32% of the women.

3.1. Descriptive statistics

In the IC group statistically a significant higher percentage of women of Dutch origin and both partners being employed participated (Table 1). Nulliparous women in the IC group were more likely to be of Dutch origin and to have a paid job compared to those in the control period.

Table 1.

Differences in sociodemographic characteristics reported in baseline questionnaire between the control and intervention period for nulli- and multiparous women (n = 2338).

| Total study population |

Nulliparous |

Multiparous |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n = 751, %n |

IC n = 1076, %n |

CP n = 511, %n |

Control n = 351, %n |

IC n = 431, %n |

CP n = 339 |

Control n = 400, %n |

IC n = 645, %n |

CP n = 172 |

||

| Level of education | Low | 8.4 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.9 |

| Average | 34.0 | 35.9 | 35.8 | 33.3 | 36.0 | 34.2 | 34.5 | 35.8 | 39.0 | |

| High | 57.7 | 56.0 | 56.2 | 58.4 | 56.8 | 58.7 | 57.0 | 55.5 | 51.2 | |

| Age | < 23 years | 2.0 | 1.2 | 2.5* | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 23–28 | 29.0 | 24.7 | 31.7 | 39.9 | 34.8 | 38.9 | 19.5 | 18.0 | 17.4 | |

| 29–35 | 57.0 | 59.5 | 53.8 | 49.9 | 54.1 | 49.0 | 63.3 | 63.1 | 63.4 | |

| >35 years | 12.0 | 14.6 | 11.9 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 16.3 | 18.8 | 19.2 | |

| Ethnicity | Dutch | 84.4 | 88.4** | 84.5 | 84.0 | 87.9* | 81.7 | 84.8 | 88.7 | 90.1 |

| Non-western | 9.7 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 4.7 | |

| Other western | 5.9 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.2 | |

| Partner | With partner | 97.9 | 99.0 | 98.0 | 95.7 | 98.4 | 97.3 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 99.4 |

| Employment among women with partner: | n = 735 | n = 1065 | n = 501 | n = 336 | n = 424 | n = 330 | n = 399 | n = 641 | n = 171 | |

| Employment | Both partners employed | 80.7 | 86.3* | 86.1 | 82.3 | 90.5** | 89.1 | 79.3 | 83.6 | 80.2 |

| One partner employed | 17.3 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 16.0 | 7.9 | 10.3 | 18.5 | 15.3 | 18.0 | |

| Not employed | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |

3.2. Intervention period group versus control period group

The results of the analysis performed on the total study population, without propensity score matching, are presented in Table S1.

Table 2 describes the results after the multilevel analysis and propensity score matching for the entire group, which includes nulliparous and multiparous women together.

Table 2.

Multi-level analyses after propensity score matching comparing women that did not participate in CP with a comparable control group and the group that participated in CP with a comparable control group (n = 2132).

|

Control-Individual care N = 658 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care group N = 658 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care versus control-Individual care β (95% CI) or OR (95% CI)• |

Control-CP N = 400 %N or mean ± SD |

CP group N = 416 %N or mean ± SD |

CP versus control-CP β (95% CI) or OR (95% CI)• |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking (Yes) | 12 weeks | 4.1 | 3.8 | reference | 2.9 | 3.1 | – |

| 28 weeks | 4.4 | 4.3 | 1.02 (0.54 – 1.91)• | 3.3 | 2.4 | 0.80 (0.36 – 1.76)• | |

| 36 weeks | 4.3 | 4.1 | 1.04 (0.56 – 1.93)• | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.81 (0.38 – 1.72)• | |

| 6 weeks pp | 5.5 | 4.6 | 0.93 (0.53 – 1.64)• | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.64 (0.32 – 1.28)• | |

| Alcohol use (Yes) | Before pregnancy | 62.2 | 65.0 | reference | 61.1 | 63.2 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 48.8 | 50.9 | 1.00 (0.75 – 1.34)• | 28.2 | 40.1 | 0.59 (0.42 – 0.84)• | |

| Healthy eating and physical activity score | 12 weeks | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | reference | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | – |

| 28 weeks | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | −0.19 (−0.32 to − 0.06) | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 0.10 (−0.06 to 0.26) | |

| 6 weeks pp | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | −0.08 (−0.22 to 0.05) | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 0.19 (0.02 – 0.37) | |

| Gestational weight (kg) | 12 weeks | 70.4 ± 12.6 | 70.4 ± 12.4 | reference | 71.2 ± 13.1 | 71.1 ± 13.0 | – |

| 36 weeks | 81.8 ± 12.3 | 81.6 ± 12.4 | 0.26 (−0.32 to 0.84) | 82.9 ± 12.7 | 82.2 ± 13.1 | −0.62(−1.37 to 0.12) | |

| Health behaviour knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | reference | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| 28 weeks | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.04) | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) | |

| Pregnancy knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | reference | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | – |

| 36 weeks | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | −0.05 (−0.15 to 0.06) | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 0.05 (0.01 – 0.08) | |

| Stress | 12 weeks | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | reference | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | – |

| 36 weeks | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.04 (0.004 – 0.07) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.01 (−0.007 – 0.04) | |

| Perceived stress | 12 weeks | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | reference | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 3.0 ± 2.4 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 0.09 (−0.12 to 0.31) | 3.3 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 2.2 | 0.09 (−0.18 to 0.36) | |

| Coping | 12 weeks | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | reference | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | – |

| 36 weeks | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.18) | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.12) | |

| Support | 12 weeks | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | reference | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0.04 (−0.07 to 0.15) | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | −0.001 (−0.06 to 0.06) | |

| Depression (Yes) | 28 weeks | 3.7 | 2.1 | reference | 3.8 | 3.8 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.0 | 2.7 | 1.01 (0.60 – 1.72)• | 4.8 | 4.1 | 1.05 (0.57 – 1.95)• | |

| Healthcare use (Midwife) | <36 weeks | 8.8 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 1.9 | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.28) | 8.9 ± 2.1 | 10.1 ± 2.1 | 1.25 (0.96 – 1.54) |

| >36 weeks | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.15) | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 7.2 ± 5.1 | 0.10 (−0.15 to 0.35) | |

| Healthcare use (Gynecologist) | <36 weeks | 1.2 ± 2.0 | 1.2 ± 2.2 | 0.06 (−0.17 to 0.29) | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 1.3 ± 2.6 | 0.10 (−0.22 to 0.42) |

| >36 weeks | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | −0.06 (−0.24 to 0.11) | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 3.0 | 0.24 (−0.11 to 0.59) | |

| Healthcare use (Total obstetric care) | <36 weeks | 15.3 ± 4.9 | 15.4 ± 5.6 | 0.37 (−0.20 to 0.95) | 15.8 ± 5.0 | 17.6 ± 5.5 | 1.81 (1.06 – 2.55) |

| >36 weeks | 6.6 ± 3.3 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | −0.001 (−0.43 to 0.43) | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 7.2 ± 5.1 | 0.39 (−0.22 to 1.00) | |

| Healthcare use (Other) | 12 weeks | 3.0 ± 4.5 | 3.0 ± 5.1 | reference | 3.3 ± 4.8 | 3.4 ± 4.4 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 3.8 ± 4.7 | 3.8 ± 4.6 | 0.12 (−0.37 to 0.60) | 3.8 ± 4.7 | 4.0 ± 4.4 | 0.04 (−0.59 to 0.66) | |

| Participation and satisfaction | 36 weeks | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | −0.002 (−0.07 to 0.07) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 0.19 (0.10 – 0.28) |

| Satisfaction during pregnancy | 36 weeks | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | −0.01 (−0.14 to 0.12) | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 8.4 ± 0.9 | 0.28 (0.13 – 0.42) |

• Odds Ratio’s.

CP group vs Control-CP group (Table 2 after propensity score matching): Compared to control-CP women, CP women had higher pregnancy knowledge scores at 36 weeks, consumed less alcohol, more frequently complied with the norm for healthy eating and physical activity at six weeks postpartum, and used more obstetric care (midwife and total obstetric care) before 36 weeks. Satisfaction scores were significantly higher among CP women.

IC group vs Control-Individual care group (Table 2): Women in the IC group less often complied to the norm for healthy eating and physical activity at 28 weeks and scored higher on the stress scale at 36 weeks pregnancy compared to the control-Individual care group women.

The results for nulliparous and multiparous women separately, after propensity scoring, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multi-level analyses after propensity score matching comparing the nulliparous and multiparous women that did not participate in CP with a comparable control group and the group that participated in CP with a comparable control group (n = 2151).

| Nulliparous |

Control-Individual care N = 305 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care group N = 305 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care versus control-Individual care β (95% CI) or OR (95% CI)• |

Control-CP N = 267 %N or mean ± SD |

CP N = 267 %N or mean ± SD |

CP versus control-CP β (95% CI) or OR (95% CI)• |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking (Yes) |

12 weeks | 4.9 ± | 3.9 | reference | 3.0 | 3.8 | – |

| 28 weeks | 5.3 | 4.9 | 1.09 (0.43 – 2.77)• | 3.7 | 2.7 | 0.72 (0.28 – 1.89)• | |

| 36 weeks | 4.9 | 4.9 | 1.21 (0.49 – 3.04)• | 3.4 | 1.9 | 0.71 (0.28 – 1.77)• | |

| 6 weeks pp | 6.9 | 4.6 | 0.85 (0.38 – 1.86)• | 6.0 | 2.3 | 0.51 (0.22 – 1.17)• | |

| Alcohol use (Yes) | Before pregnancy | 66.8 | 70.2 | reference | 64.4 | 66.7 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 48.7 | 54.1 | 1.20 (0.79 – 1.82)• | 46.4 | 42.0 | 0.71 (0.46–1.09)• | |

| Healthy eating and physical activity score | 12 weeks | 2.3 ± 1.07 | 2.2 ± 0.99 | reference | 2.3 ± 1.06 | 2.2 ± 1.01 | – |

| 28 weeks | 1.8 ± 1.22 | 1.5 ± 1.27 | −0.24 (−0.43 to − 0.05) | 1.8 ± 1.25 | 1.8 ± 1.29 | 0.08 (−0.12 to 0.28) | |

| 6 weeks pp | 1.5 ± 1.32 | 1.4 ± 1.37 | −0.05 (−0.26 to 0.16) | 1.5 ± 1.35 | 1.7 ± 1.38 | 0.28 (0.06 – 0.51) | |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 12 weeks | 70.0 ± 12.72 | 70.0 ± 12.22 | reference | 70.0 ± 12.62 | 69.8 ± 13.56 | – |

| 36 weeks | 81.6 ± 12.77 | 81.7 ± 11.83 | 0.21 (−0.71 to 1.12) | 81.8 ± 12.44 | 81.6 ± 13.51 | −0.80 (−1.73 to 0.13) | |

| Health behaviour knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.8 ± 0.43 | 4.8 ± 0.44 | reference | 4.6 ± 0.39 | 4.6 ± 0.42 | – |

| 28 weeks | 4.6 ± 0.35 | 4.7 ± 0.34 | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.05) | 4.7 ± 0.32 | 4.7 ± 0.29 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | |

| Pregnancy knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.1 ± 0.30 | 4.0 ± 0.51 | reference | 4.0 ± 0.39 | 4.0 ± 0.38 | – |

| 36 weeks | 4.4 ± 0.32 | 4.4 ± 0.33 | −0.11 (−0.29 to 0.06) | 4.4 ± 0.32 | 4.4 ± 0.31 | 0.04 (−0.004 to 0.09) | |

| Stress | 12 weeks | 1.1 ± 0.25 | 1.2 ± 0.38 | reference | 1.3 ± 0.21 | 1.3 ± 0.23 | – |

| 36 weeks | 1.3 ± 0.21 | 1.3 ± 0.17 | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.09) | 1.3 ± 0.21 | 1.3 ± 0.20 | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | |

| Perceived stress | 12 weeks | 2.7 ± 2.38 | 2.5 ± 2.23 | reference | 3.1 ± 2.46 | 3.3 ± 2.48 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.0 ± 2.02 | 3.1 ± 1.97 | 0.08 (−0.25 to 0.40) | 3.1 ± 1.99 | 3.2 ± 2.18 | −0.03 (−0.36 to 0.30) | |

| Coping | 12 weeks | 2.4 ± 0.70 | 2.6 ± 0.61 | reference | 2.5 ± 0.55 | 2.5 ± 0.52 | – |

| 36 weeks | 2.6 ± 0.58 | 2.6 ± 0.51 | 0.13 (−0.15 to 0.41) | 2.6 ± 0.57 | 2.6 ± 0.53 | 0.03 (−0.05 to 0.11) | |

| Support | 12 weeks | 3.0 ± 0.47 | 3.1 ± 0.43 | reference | 2.9 ± 0.47 | 2.9 ± 0.49 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.1 ± 0.41 | 3.0 ± 0.41 | 0.04 (−0.13 to 0.21) | 3.1 ± 0.42 | 3.0 ± 0.41 | −0.03 (−0.11 to 0.04) | |

| Depression (Yes) | 28 weeks | 3.0 | 2.6 | reference | 2.6 | 4.2 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.3 | 4.3 | 1.19 (0.57 – 2.50)• | 4.5 | 5.3 | 1.20 (0.56 – 2.56)• | |

| Healthcare use (Midwife) | <36 weeks | 9.0 ± 2.09 | 8.7 ± 1.92 | 0.04 (−0.27 – 0.36) | 8.9 ± 2.11 | 10.2 ± 1.90 | 1.29 (0.95 – 1.64) |

| >36 weeks | 3.4 ± 1.69 | 3.3 ± 1.50 | −0.06 (−0.33 to 0.20) | 3.4 ± 1.55 | 3.4 ± 1.93 | 0.07 (−0.24 to 0.38) | |

| Healthcare use (Gynecologist) | <36 weeks | 1.2 ± 2.08 | 1.2 ± 2.01 | −0.006 (−0.34 to 0.33) | 1.2 ± 2.01 | 1.2 ± 2.28 | −0.07 (−0.45 to 0.31) |

| >36 weeks | 1.3 ± 1.78 | 1.1 ± 1.67 | −0.19 (−0.48 to 0.09) | 1.3 ± 1.74 | 1.3 ± 2.93 | 0.09 (−0.34 to 0.52) | |

| Healthcare use (Total obstetric care) | <36 weeks | 16.2 ± 5.31 | 15.7 ± 5.19 | −0.006 (−0.86 to 0.85) | 16.3 ± 5.31 | 17.6 ± 4.79 | 1.32 (0.43 – 2.21) |

| >36 weeks | 7.2 ± 3.36 | 6.8 ± 3.93 | −0.46 (−1.06 to 0.15) | 7.2 ± 3.40 | 7.3 ± 4.71 | 0.05 (−0.67 to 0.78) | |

| Healthcare use (Other) | 12 weeks | 3.5 ± 4.71 | 3.5 ± 5.99 | reference | 3.6 ± 4.81 | 3.7 ± 4.74 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 3.5 ± 4.47 | 3.5 ± 4.51 | 0.21 (−0.49 to 0.90) | 3.6 ± 4.32 | 3.7 ± 4.11 | −0.01 (−0.73 to 0.70) | |

| Participation and satisfaction | 36 weeks | 3.9 ± 0.49 | 3.9 ± 0.55 | 0.04 (−0.07 to 0.14) | 4.0 ± 0.49 | 4.1 ± 0.56 | 0.21 (0.10 – 0.32) |

| Satisfaction during pregnancy | 36 weeks | 8.0 ± 0.90 | 8.0 ± 1.06 | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.27) | 8.0 ± 0.87 | 8.3 ± 0.90 | 0.28 (0.10 – 0.47) |

| Multiparous |

Control-Individual care N = 354 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care group N = 354 %N or mean ± SD |

Individual care versus control-Individual care (ref)# β (95% CI) ors OR (95% CI) |

Control-CP N = 152 %N or mean ± SD |

CP N = 152 %N or mean ± SD |

CP versus control-CP (ref)# β (95% CI) or OR (95% CI) • |

|

| Smoking (Yes) |

12 weeks | 3.4 | 3.7 | reference | 2.6 | 2.0 | – |

| 28 weeks | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.96 (0.41 – 2.27)• | 2.6 | 2.0 | n.a $. | |

| 36 weeks | 3.7 | 3.4 | 0.92 (0.39 – 2.16)• | 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.13 (0.28 – 4.52)• | |

| 6 weeks pp | 4.2 | 4.5 | 1.02 (0.45 – 2.31)• | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.13 (0.28 – 4.52)• | |

| Alcohol use (Yes) | Before pregnancy | 58.2 | 60.6 | reference | 55.3 | 57.2 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 48.9 | 48.2 | 0.83 (0.55 – 1.24)• | 51.3 | 36.8 | 0.42 (0.23 – 0.78)• | |

| Healthy eating and physical activity score | 12 weeks | 2.3 ± 1.05 | 2.2 ± 1.00 | reference | 2.4 ± 1.01 | 2.3 ± 1.03 | – |

| 28 weeks | 1.8 ± 1.21 | 1.6 ± 1.25 | −0.13 (−0.30 to 0.04) | 1.9 ± 1.15 | 1.8 ± 1.26 | 0.11 (−0.17 to 0.38) | |

| 6 weeks pp | 1.6 ± 1.25 | 1.4 ± 1.26 | −0.10 (−0.27 to 0.07) | 1.7 ± 1.22 | 1.7 ± 1.23 | −0.01 (−0.28 to 0.26) | |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 12 weeks | 70.7 ± 12.42 | 70.8 ± 12.51 | reference | 73.4 ± 13.64 | 73.3 ± 11.76 | – |

| 36 weeks | 81.9 ± 12.0 | 81.5 ± 12.84 | 0.33 (−0.39 to 1.05) | 85.0 ± 12.92 | 83.2 ± 12.29 | −0.38 (−1.61 to 0.86) | |

| Health behaviour knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.8 ± 0.39 | 4.9 ± 0.31 | reference | 4.7 ± 0.37 | 4.7 ± 0.29 | – |

| 28 weeks | 4.6 ± 0.33 | 4.6 ± 0.32 | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.07) | 4.7 ± 0.34 | 4.7 ± 0.32 | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) | |

| Pregnancy knowledge | 12 weeks | 4.6 ± 0.50 | 4.5 ± 0.57 | reference | 4.5 ± 0.29 | 4.5 ± 0.30 | – |

| 36 weeks | 4.5 ± 0.31 | 4.5 ± 0.32 | 0.009 (−0.12 to 0.13) | 4.5 ± 0.30 | 4.5 ± 0.30 | 0.05 (−0.008 to 0.10) | |

| Stress | 12 weeks | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 1.0 ± 0.00 | reference | 1.2 ± 0.19 | 1.2 ± 0.16 | – |

| 36 weeks | 1.3 ± 0.17 | 1.26 ± 0.15 | 0.04 (−0.001 to 0.07) | 1.3 ± 0.18 | 1.3 ± 0.16 | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | |

| Perceived stress | 12 weeks | 2.5 ± 2.30 | 2.4 ± 2.17 | reference | 2.7 ± 2.59 | 2.6 ± 2.21 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.4 ± 2.15 | 3.4 ± 2.01 | 0.11 (−0.18 to 0.40) | 3.5 ± 2.26 | 3.7 ± 2.22 | 0.36 (−0.11 to 0.83) | |

| Coping | 12 weeks | 2.2 ± 0.77 | 2.4 ± 0.67 | reference | 2.4 ± 0.64 | 2.4 ± 0.63 | – |

| 36 weeks | 2.5 ± 0.58 | 2.6 ± 0.51 | −0.03 (−0.23 to 0.16) | 2.5 ± 0.61 | 2.6 ± 0.51 | 0.09 (−0.03 to 0.20) | |

| Support | 12 weeks | 3.1 ± 0.41 | 3.0 ± 0.39 | reference | 2.9 ± 0.44 | 2.9 ± 0.47 | – |

| 36 weeks | 3.0 ± 0.43 | 3.0 ± 0.39 | 0.02 (−0.11 to 0.16) | 2.9 ± 0.41 | 2.9 ± 0.40 | 0.04 (−0.06 to 0.13) | |

| Depression (Yes) | 28 weeks | 4.2 | 1.7 | reference | 5.9 | 3.3 | – |

| 36 weeks | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.90 (0.42 – 1.93)• | 5.3 | 2.0 | 0.80 (0.26 – 2.44)• | |

| Healthcare use (Midwife) | <36 weeks | 8.6 ± 1.93 | 8.6 ± 1.87 | 0.12 (−0.15 to 0.38) | 8.8 ± 2.03 | 9.9 ± 2.37 | 1.22 (0.72 – 1.73) |

| >36 weeks | 3.2 ± 1.47 | 3.2 ± 1.53 | 0.01 (−0.21 to 0.24) | 3.2 ± 1.42 | 3.4 ± 2.11 | 0.14 (−0.29 to 0.57) | |

| Healthcare use (Gynecologist) | <36 weeks | 1.11 ± 1.92 | 1.2 ± 2.34 | 0.12 (−0.21 to 0.44) | 1.1 ± 1.78 | 1.6 ± 2.99 | 0.41 (−0.18–1.00) |

| >36 weeks | 1.0 ± 1.49 | 1.1 ± 1.37 | 0.05 (−0.17 to 0.26) | 1.1 ± 1.32 | 1.5 ± 3.24 | 0.55 (−0.05 to 1.15) | |

| Healthcare use (Total obstetric care) | <36 weeks | 14.6 ± 4.43 | 15.1 ± 5.96 | 0.76 (−0.01 to 1.54) | 14.9 ± 4.24 | 17.6 ± 6.59 | 2.83 (1.50 – 4.15) |

| >36 weeks | 6.1 ± 3.24 | 6.5 ± 4.66 | 0.38 (−0.22 to 0.98) | 6.2 ± 2.79 | 7.2 ± 5.69 | 1.01 (−0.08 to 2.10) | |

| Healthcare use (Other) | 12 weeks | 2.6 ± 4.38 | 2.6 ± 4.21 | reference | 2.7 ± 4.68 | 2.8 ± 3.60 | – |

| 6 weeks pp | 4.0 ± 4.94 | 4.1 ± 4.60 | 0.08 (−0.57 to 0.74) | 4.4 ± 5.38 | 4.5 ± 4.81 | 0.22 (−0.93 – 1.36) | |

| Participation and satisfaction | 36 weeks | 4.1 ± 0.52 | 4.0 ± 0.52 | −0.03 (−0.13 to 0.07) | 4.0 ± 0.54 | 4.2 ± 0.48 | 0.17 (0.02 – 0.32) |

| Satisfaction pregnancy | 36 weeks | 8.3 ± 0.84 | 8.2 ± 0.92 | −0.06 (−0.23 to 0.10) | 8.2 ± 0.81 | 8.5 ± 0.76 | 0.27 (0.05 – 0.50) |

• Odds Ratio’s $ There was no change between baseline and 28 weeks of gestation.

3.3. Nulliparous and multiparous – CP group vs Control-CP group

Nulliparous women: Compared to nulliparous Control-CP women, nulliparous CP women more often complied to the norm for healthy eating and physical activity at six weeks postpartum and their prenatal use (midwife and total obstetric care) before 36 weeks was higher. Among these women physical activity at six weeks postpartum was statistically significantly higher. Moreover, their breakfast, fruit, and vegetable intake were higher, although not significantly (Table Ss). Smoking behaviour decreased from 3.8% at intake to 1.9% at 36 weeks and 2.3% after pregnancy in the nulliparous CP group, while it increased from 3.0% to 3.4% and 6.0%, respectively in the nulliparous control-CP group (although the differences were not statistically significant between groups).

Multiparous women: Alcohol use at six weeks postpartum was significantly lower among multiparous CP women.

Both nulliparous and multiparous CP women were more satisfied with care during pregnancy and scored higher for the variable participation and satisfaction.

3.4. Nulliparous and multiparous – IC group vs Control-IC group

Nulliparous women: Women in the IC-group less often complied with the norm for healthy eating and physical activity at 28 weeks. Their daily breakfast consumption, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake at 28 weeks, were lower, although not statistically significant, except for breakfast consumption (Table S2).

Multiparous women: For multiparous women in the IC group no significant differences were found compared to women in the control-IC group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings and interpretations

The aim of the current study was to assess the effect of CP in the Netherlands on health behaviours, health and pregnancy knowledge, psychosocial outcomes, health care use and satisfaction. Women participating in CP more often complied to the norm for healthy eating and physical activity and used less alcohol at six weeks postpartum. They acquired more knowledge regarding pregnancy issues, attended more midwifery and total obstetric care visits, and were more satisfied with antenatal care. Specifically, nulliparous CP women were eating healthier and were more physically active after pregnancy and they attended more obstetric care. Multiparous CP women drank alcohol less often postpartum.

What stands out in this study is that most of the positive effects of CP on health behaviours occur postpartum, indicating that women participating in CP are more likely to continue healthy behaviour or less likely to relapse after pregnancy. Other studies also found positive effects of CP on postpartum outcomes, such as higher rates of contraception use and postpartum visits (Heberlein et al., 2020). These findings indicate that CP might be an effective method to also target postpartum health risks.

The finding that women participating in CP are less likely to consume alcohol at six weeks postpartum and complied more to the Dutch norms for healthy eating and physical activity in that period could be related to the higher uptake rate of breastfeeding (Wagijo et al., 2022). Other studies have shown that women that breastfeed are aware of the importance of the intake of healthy nutrients (MacMillan Uribe and Olson, 2019). In contrast they have more concerns regarding breastfeeding and exercise: that it could adversely affect their breast milk and impact their infants’ growth (Bane, 2015). We checked whether breastfeeding initiation rate was related to these behaviours and we found that alcohol use and complying to healthy eating recommendations at six weeks postpartum was related to breastfeeding uptake while physical activity was not. However, the increased physical activity rates in women in the CP-group were in line with the recommendation that postpartum exercise routine should gradually return to normal as soon as it is safe in order to promote healing and losing weight (Campos et al., 2021). In our previous study, we found significant lower hypertension rates among CP women (Wagijo et al., 2022), which might also be related to improved health behaviours found in the current study. However, more research is required to investigate underlying associations.

There was not a significant difference for smoking, unlike the study by Zielinski et al. (Zielinski et al., 2014). The total number of smokers was small in our study and, thus significant differences were difficult to find. However, we did observe lower smoking rates among CP women. A similar non-significant trend was seen in the study by Klerman et al. (2001) in which educational peer groups were integrated in antenatal care and compared with usual care. These findings suggest that CP has the potential to effectively encourage smoking cessation.

The difference found for total prenatal health care use is explained by the higher number of attended midwife appointments. Rijnders et al., evaluated the implementation of CP in the Dutch healthcare system and also found a higher attendance rate for antenatal visits among women who participated in CP (Rijnders et al., 2019). It is also in line with results of several international studies (Klima et al., 2009, Trudnak et al., 2013, Carter et al., 2016).

Our findings regarding satisfaction with antenatal care are similar to those of previous studies (Kennedy et al., 2009, Klima et al., 2009). Scores for satisfaction with antenatal and postnatal care are high in the Netherlands,(Wiegers, 2009) but the implementation of CP still resulted in increased rates.

Most of the women participating in this study were average to high educated women. Educational level is related to practicing healthy behaviours (Cowell, 2006), which is why it would be insightful to investigate whether the effect of CP on health behaviours will be stronger when women with low education participate in CP.

5. Strengths and limitations

This study is one of the few that focuses on health behaviour outcomes among CP women. Additional strengths of this study are the large study population and that with the study design, a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial, temporal differences that may affect outcomes are eliminated.

We chose a clustered stepped wedge design because randomisation at individual level was not possible. Since the case load in midwifery practices is too small, and individual randomisation would lead to small group sizes. In addition, midwives wanted women to have a choice in the type of antenatal care they experienced. With the propensity score matching and intention-to-treat analysis the effect of differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the different groups were minimalized and bias due to missing data was reduced by using multiple imputation.

Response bias could have occurred because of the likelihood of desirable answers. However, this is also applicable for women who received IC. The questionnaires were anonymous and to reduce recall bias, questions referred to a rather recent and limited period in women’s past (i.e. one week ago). All these mentioned risks of bias are inherent to the use of questionnaires.

Measurement began shortly after the healthcare providers received their training and implementation of CP in the practices. The effect of CP might be stronger when care providers have more experience with this model of care. Furthermore, the healthcare providers who received training also provided IC in their practice. Based on comments from CP trained care providers, we assumed that the CP training also influenced the way they provide care, thereby potentially limiting the effect of CP.

The questions regarding healthy eating and physical activity were limited and physical activity, eating fruit and vegetables could be interpreted in different ways by the women. Future studies could gain more precise insight into the nutritious behaviour and physical activity of the women, and the relation with the information received during the CP sessions.

6. Conclusion

This study revealed that women participating in CP have an increased healthy eating and physical activity score, consume less alcohol after pregnancy compared to women who choose individual care, and a trend was seen in lower smoking rates among CP women. CP participants also were more satisfied with antenatal care, made more use of antenatal care, and had increased knowledge of pregnancy.

7. Contribution to authorship

MW carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

BvZ, MC and MR conceptualised and designed the study, supervised the analyses, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

DB and JvL conceptualised the study, participated in interpreting the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding

The study was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mary-ann Wagijo: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mathilde Crone: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Birgit Bruinsma-van Zwicht: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision. Jan van Lith: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Deborah L. Billings: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Marlies Rijnders: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the women and antenatal care professionals who participated in the study.

References

- Abshire C., McDowell M., Crockett A.H., Fleischer N.L. The impact of centeringpregnancy group prenatal care on birth outcomes in medicaid eligible women. J. Womens Health (Larchmt.) 2019;28(7):919–928. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adaji S.E., Jimoh A., Bawa U., Ibrahim H.I., Olorukooba A.A., Adelaiye H., Garba C., Lukong A., Idris S., Shittu O.S. Women's experience with group prenatal care in a rural community in northern Nigeria. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019;145(2):164–169. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht S.A., Higgins L.W., Lebow H. Knowledge about the deleterious effects of smoking and its relationship to smoking cessation among pregnant adolescents. Adolescence. 2000;35(140):709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderdice F., Lynn F., Lobel M. A review and psychometric evaluation of pregnancy-specific stress measures. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;33(2):62–77. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.673040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm-Roijer C., Stagmo M., Udén G., Erhardt L. Better knowledge improves adherence to lifestyle changes and medication in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2004;3(4):321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin K.A. Comparison of selected outcomes of CenteringPregnancy versus traditional prenatal care. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51(4):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bane S.M. Postpartum exercise and lactation. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;58(4):885–892. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson I., McDonald S.W., Vekved M., McNeil D.A., Dolan S.M., Tough S.C. Comparing CenteringPregnancy(R) to standard prenatal care plus prenatal education. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- “Beweegrichtlijnen 2017.” from https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2017/08/22/beweegrichtlijnen-2017.

- Bridges K.R., Sanderman R., van Sonderen E. An English language version of the social support list: preliminary reliability. Psychol. Rep. 2002;90(3 Pt 1):1055–1058. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buultjens M., Farouque A., Karimi L., Whitby L., Milgrom J., Erbas B. The contribution of group prenatal care to maternal psychological health outcomes: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2021;34(6):e631–e642. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byerley B.M., Haas D.M. A systematic overview of the literature regarding group prenatal care for high-risk pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):329. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1522-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos M.d.S.B., Buglia S., Colombo C.S.S.d.S., Buchler R.D.D., Brito A.S.X.d., Mizzaci C.C., Feitosa R.H.F., Leite D.B., Hossri C.A.C., Albuquerque L.C.A.d. Position statement on exercise during pregnancy and the post-partum period–2021. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2021;117:160–180. doi: 10.36660/abc.20210408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter E.B., Temming L.A., Akin J., Fowler S., Macones G.A., Colditz G.A., Tuuli M.G. Group prenatal care compared with traditional prenatal care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;128(3):551–561. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell A.J. The relationship between education and health behavior: some empirical evidence. Health Econ. 2006;15(2):125–146. doi: 10.1002/hec.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J.L., Holden J.M., Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craswell A., Kearney L., Reed R. ‘Expecting and connecting’ group pregnancy care: evaluation of a collaborative clinic. Women Birth. 2016;29(5):416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett A.H., Heberlein E.C., Smith J.C., Ozluk P., Covington-Kolb S., Willis C. Effects of a multi-site expansion of group prenatal care on birth outcomes. Matern. Child Health J. 2019;23(10):1424–1433. doi: 10.1007/s10995-019-02795-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S.D., Grilo S., Lewis J.B., Novick G., Rising S.S., Tobin J.N., Ickovics J.R. Group prenatal care attendance: determinants and relationship with care satisfaction. Matern. Child Health J. 2017;21(4):770–776. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele, B., 2018. The “Bar procedure”: Spss single dataframe aggregating spss multiply imputed split files.

- de Ridder D., Schreurs K. Coping, social support and chronic disease: a research agenda. Psychol. Health Med. 1996;1(1):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D.T., Schreurs K.M., Bensing J.M. Adaptive tasks, coping and quality of life of chronically ill patients: the cases of Parkinson's disease and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Health Psychol. 1998;3(1):87–101. doi: 10.1177/135910539800300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplanches T., Bouit C., Cottenet J., Szczepanski E., Quantin C., Fauque P., Sagot P. Combined effects of increasing maternal age and nulliparity on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and small for gestational age. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;18:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eluwa G.I., Adebajo S.B., Torpey K., Shittu O., Abdu-Aguye S., Pearlman D., Bawa U., Olorukooba A., Khamofu H., Chiegli R. The effects of centering pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes in northern Nigeria; a prospective cohort analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1805-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani R.M.A. Effect of group centering pregnancy on empowering women with gestational hypertension. Hypothesis. 2018;55 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J.G., Lobel M. Types, patterns, and predictors of coping with stress during pregnancy: examination of the Revised Prenatal Coping Inventory in a diverse sample. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008;29(2):97–104. doi: 10.1080/01674820701690624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein E., Smith J., Willis C., Hall W., Covington-Kolb S., Crockett A. The effects of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on postpartum visit attendance and contraception use. Contraception. 2020;102(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J.R., Kershaw T.S., Westdahl C., Rising S.S., Klima C., Reynolds H., Magriples U. Group prenatal care and preterm birth weight: results from a matched cohort study at public clinics. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J.R., Kershaw T.S., Westdahl C., Magriples U., Massey Z., Reynolds H., Rising S.S. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):330–339. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari F., Eftekhar H., Fotouhi A., Mohammad K., Hantoushzadeh S. Comparison of maternal and neonatal outcomes of group versus individual prenatal care: a new experience in Iran. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(7):571–584. doi: 10.1080/07399331003646323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen J.C., Gluud C., Wetterslev J., Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials–a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H.P., Farrell T., Paden R., Hill S., Jolivet R., Willetts J., Rising S.S. “I wasn't alone”–a study of group prenatal care in the military. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(3):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman L.V., Ramey S.L., Goldenberg R.L., Marbury S., Hou J., Cliver S.P. A randomized trial of augmented prenatal care for multiple-risk, Medicaid-eligible African American women. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91(1):105. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klima C., Norr K., Vonderheid S., Handler A. Introduction of CenteringPregnancy in a public health clinic. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster, L., B.M., Stoof R, Schipper M (2015). Takenpakket verloskunde, Onderzoek naar taken, tijdsbesteding en productie van verloskundigen. Barneveld.

- Koullali B., van Zijl M.D., Kazemier B.M., Oudijk M.A., Mol B.W.J., Pajkrt E., Ravelli A.C.J. The association between parity and spontaneous preterm birth: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02940-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromhout D., Spaaij C.J.K., de Goede J., Weggemans R.M. The 2015 Dutch food-based dietary guidelines. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016;70(8):869–878. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield V.M., Adams B.N. Patient participation in alternative perinatal care: impact on satisfaction and health locus of control. Res. Nurs. Health. 1987;10(3):139–148. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield V.M., Chang A., Adams B.N. Participation in alternative care: relationship to anxiety, depression, and hostility. Res. Nurs. Health. 1990;13(1):17–25. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang Y., Wu Y., Chen X., Bai J. Effectiveness of the CenteringPregnancy program on maternal and birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan Uribe A.L., Olson B.H. Exploring healthy eating and exercise behaviors among low-income breastfeeding mothers. J. Hum. Lact. 2019;35(1):59–70. doi: 10.1177/0890334418768792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk T., Abd-Allah I.M., Shalaby H. Effect of applying centering pregnancy model versus individual prenatal care on certain prenatal care outcomes. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2018;6(2):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mohangoo A.D., Buitendijk S.E., Hukkelhoven C.W., Ravelli A.C., Rijninks-van Driel G.C., Tamminga P., Nijhuis J.G. Higher perinatal mortality in The Netherlands than in other European countries: the Peristat-II study. Ned Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2008;152(50):2718–2727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picklesimer, A. H., D. Billings, N. Hale, D. Blackhurst and S. Covington-Kolb (2012). The effect of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on preterm birth in a low-income population. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 206(5): 415 e411-417. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rijnders M., Jans S., Aalhuizen I., Detmar S., Crone M. Women-centered care: Implementation of CenteringPregnancy(R) in The Netherlands. Birth. 2019;46(3):450–460. doi: 10.1111/birt.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rising S.S. Centering pregnancy. An interdisciplinary model of empowerment. J. Nurse Midwifery. 1998;43(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(97)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rising S.S., Kennedy H.P., Klima C.S. Redesigning prenatal care through CenteringPregnancy. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(5):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelkoul M., Post M.W., de Witte L.P., van den Borne H.B. Social support, coping and subjective well-being in patients with rheumatic diseases. Patient Educ. Couns. 2000;39(2–3):205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed H.A.E. Effect of centering pregnancy model implementation on prenatal health behaviors and pregnancy related empowerment. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018;7(6):314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespear K., Waite P.J., Gast J. A comparison of health behaviors of women in centering pregnancy and traditional prenatal care. Matern. Child Health J. 2010;14(2):202–208. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeder J., Weber Yorga K., Kabir-Greher K. A review of prenatal group care literature: the need for a structured theoretical framework and systematic evaluation. Matern. Child Health J. 2012;16(1):177–187. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland C., Merrell S., Kirk J.K. CenteringPregnancy: meeting the quadruple aim in prenatal care. N C Med. J. 2016;77(6):394–397. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.6.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith E.E., Steinka-Fry K.T., Lipsey M.W. Effects of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on breastfeeding outcomes. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(4):389–395. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudnak T.E., Arboleda E., Kirby R.S., Perrin K. Outcomes of Latina women in CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care compared with individual prenatal care. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(4):396–403. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Sonderen, E., Sanderman, R., 2013. Social support: Conceptual issues and assessment strategies. Assessment in behavioral medicine, Routledge: 181-198.

- van Zwicht B.S., Crone M.R., van Lith J.M., Rijnders M.E. Group based prenatal care in a low-and high risk population in the Netherlands: a study protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):354. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagijo M.R., Crone M.R., van Zwicht B.S., van Lith J.M.M., Schindler Rising S., Rijnders M.E.B. CenteringPregnancy in the Netherlands: Who engages, who doesn't, and why. Birth. 2022;49(2):329–340. doi: 10.1111/birt.12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagijo MR, C. M., Bruinsma-van Zwicht BS, van Lith JMM, Billings DL, Rijnders MEB (2022). “The effect of CenteringPregnancy on maternal, birth, and neonatal outcomes amongst low-risk women in the Netherlands: A stepped cluster randomised trial.” Unpublished results. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Webel A.R., Okonsky J., Trompeta J., Holzemer W.L. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100(2):247–253. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S., Maxson P., Truong T., Swamy G. Psychosocial stress and preterm birth: the impact of parity and race. Matern. Child Health J. 2018;22(10):1430–1435. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegers T.A. The quality of maternity care services as experienced by women in the Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yali A.M., Lobel M. Coping and distress in pregnancy: an investigation of medically high risk women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1999;20(1):39–52. doi: 10.3109/01674829909075575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yali A.M., Lobel M. Stress-resistance resources and coping in pregnancy. Anx., Stress Cop.: Int. J. 2002;15(3):289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski R., Stork L., Deibel M., Kothari C.L., Searing K. Improving infant and maternal health through CenteringPregnancy: A comparison of maternal health indicators and infant outcomes between women receiving group versus traditional prenatal Care. OJOG. 2014;04(09):497–505. [Google Scholar]