Abstract

In situ hybridization (ISH), which visualizes nucleic acids in tissues and cells, is a powerful tool in histology and pathology. Over 50 years since its invention, multiple attempts have been made to increase the sensitivity and simplicity of these methods. Therefore, several highly sensitive in situ hybridization methods have been developed that offer researchers a wide range of options. When selecting these in situ hybridization variants, their signal-amplification principles and characteristics must be understood. In addition, from a practical point of view, a method with good monetary and time-cost performance must be chosen. This review introduces recent high-sensitivity in situ hybridization variants and presents their principles, characteristics, and costs.

Keywords: in situ hybridization, RNAscope, SABER FISH, hybridization chain reaction, ClampFish

I. Introduction

In situ hybridization, which detects and visualizes nucleic acids, is a fundamental histological and immunostaining method. Although the reliability of immunostaining depends largely on the antibodies used [8], in situ hybridization has the advantage that its sensitivity and reliability can be predicted from the target nucleic acid sequence on which the probes are designed [26, 32]. However, the experimental procedures for in situ hybridization are more complex than those for immunostaining, making its practical application difficult. In addition, conventional in situ hybridization may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect low-expression genes or short transcripts. Therefore, in situ hybridization has been continuously improved to simplify the procedure and increase sensitivity, and several variants have been developed [10, 12, 22, 37]. Using these variants, it is becoming easier for researchers to detect low-expression transcripts that are difficult to visualize with conventional sensitivity. This review provides an overview of the principles and characteristics of high-sensitivity in situ hybridization methods currently in use and describes the costs and advantages that should be considered in their application.

II. Comparison of In Situ Hybridization and Immunostaining

Immunostaining methods, which mainly target proteins, can determine the subcellular localization of target molecules. However, their limitation is that they depend on the titer and specificity of the antibodies used [8]. Because antibody-based detection is indispensable for pathological diagnosis, antibodies with guaranteed titers and specificity are readily available for human proteins, especially antibodies against pathological markers [33, 35]. However, good antibodies against proteins other than pathological markers and/or non-human proteins are not always available. In addition, because the antigen-antibody reaction depends on the conformation of the recognition site, similar conformations can cause false-positive reactions [8, 14].

For in situ hybridization, probes can be designed and synthesized based on nucleic acid sequence databases, allowing the targeting of any gene regardless of the animal species, provided that the nucleic acid sequence is known. In addition, the titer and specificity can be predicted from the length of the sequence that can be probed on the target mRNA and from its homology with other genes, respectively [7, 32]. These properties allow in situ hybridization to be used not only for transcript localization analysis, but also for verification of specificity of newly developed antibodies in combination with immunostaining [19, 30]. However, compared to immunostaining, in situ hybridization is a time-consuming procedure with many steps, which is one of the reasons why its clinical application is limited to a few purposes, such as diagnosing chromosomal aberrations [6, 15].

III. Characteristics of Conventional In Situ Hybridization and Signal Enhancement Methods

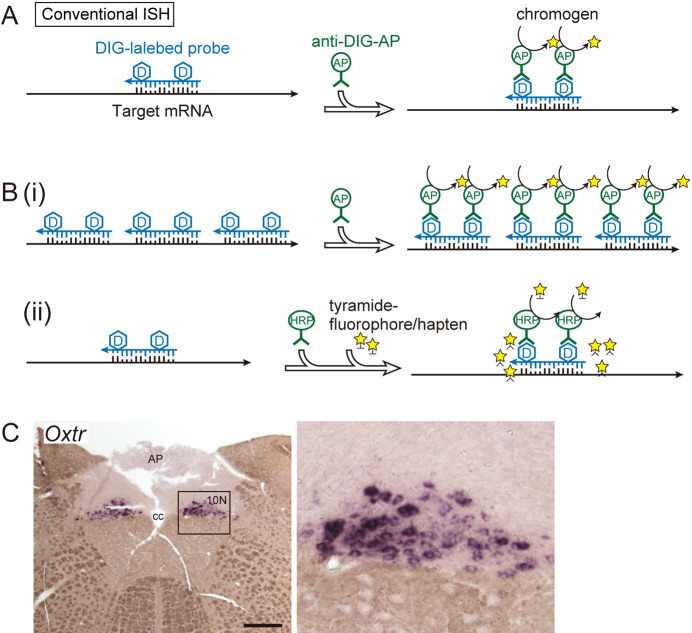

In situ hybridization employed radiolabeled probes in the early years [9, 16]; however, over the past two decades, digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes have been frequently used as “conventional” in situ hybridization methods with high detection sensitivity [7, 24, 25]. In conventional in situ hybridization, sensitivity can be increased to some extent by increasing the coverage of the target mRNA sequence (Fig. 1). Probes that are too long result in reduced cell penetration [4, 29]; therefore, they are often designed to be 200–1000 base pairs in length for RNA probes, and multiple probes are designed in different regions of the target transcript. Signal amplification using enzymatic reactions such as Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) can be combined [2]. Well-designed probes and optimized temperature conditions for hybridization and time for color development allowed for analyzing low-expression genes [17, 18] (Fig. 1C). However, conventional in situ hybridization has some disadvantages, one of which is the difficulty in combining it with immunostaining. This is due to decreased antigen reactivity for some proteins, which can be caused via proteinase treatment to increase probe permeability, or by hybridization at temperatures that cause protein denaturation [21]. Therefore, sufficient immunostaining signals may not be obtained unless they target abundant proteins or utilize antibodies at high titers. Double in situ hybridization for two gene transcripts is also difficult for some gene combinations. For highly homologous gene pairs, difficulties are faced when designing probes with appropriate lengths that ensure sensitivity while maintaining specificity. For gene pairs with widely different GC percentages of mRNA, difficulties are faced when designing probes with similar dissociation temperatures and appropriate probe lengths [20].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of conventional in situ hybridization. A: DIG-labeled in situ hybridization. RNA probes complementary to target sequences were used. A chromogenic reaction using an alkaline phosphatase-labeled antibody is shown as an example of a signal detection method. B: Examples of signal amplification methods for conventional in situ hybridization. (i) Using multiple probes to increase coverage of the target mRNA sequence. The signal strength is proportional to the total probe length. (ii) Combination with TSA amplification. Tyramide activated by peroxidase is anchored to tyrosine residues of the surrounding protein. C: Example of visualization of low-expression genes in the rat brain. Oxtr, which encodes the oxytocin receptor, is visualized in the vagus nerve nucleus (10N) of the medulla oblongata by conventional in situ hybridization without TSA amplification. The right panel is a magnified image of the framed area in the left micrograph. Bar = 500 μm. AP, area postrema; cc, central canal.

IV. Principles of High-sensitivity In Situ Hybridization Published Recently

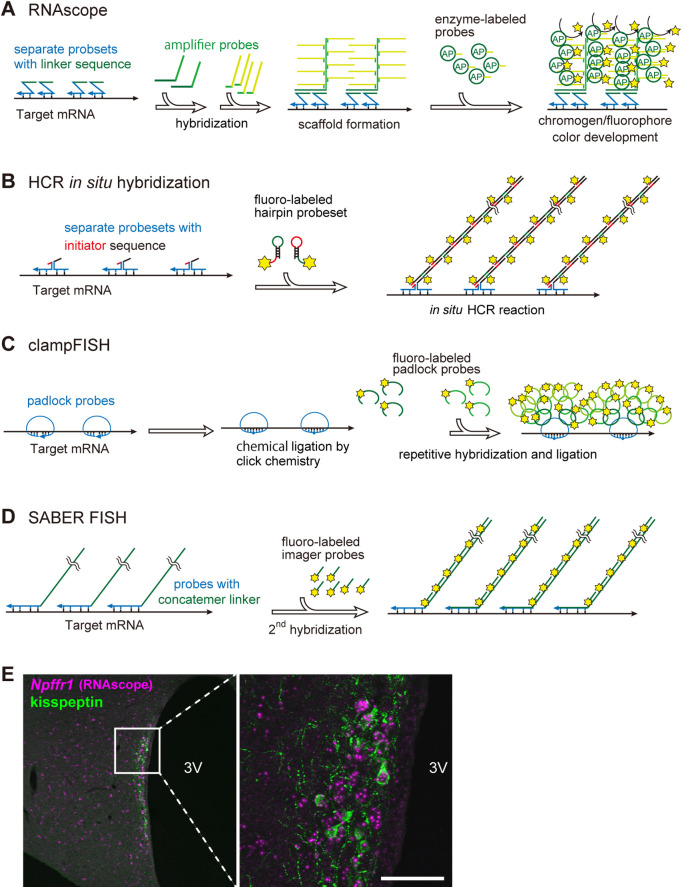

In recent years, many variants of in situ hybridization have been developed to achieve higher sensitivity, simplicity, and multiplexed fluorescence. Although these methods differ in the principle of detection, they generally share the following two procedures: the use of a synthetic oligonucleotide with a relatively short strand as a primary probe, and the hybridization of multiple secondary probes against a partial sequence of the primary probe as a linker, resulting in a substantial increase in the signals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the detection principle of high-sensitivity in situ hybridization. The common underlying mechanism of these highly sensitive in situ hybridization methods is to use multiple short oligonucleotides as primary probes and then hybridize the probes for amplification, using part of the primary probes as a linker. A: RNAscope, B: HCR in situ hybridization, C: clampFISH, D: SABER FISH. E: Example of high-sensitivity in situ hybridization image. Transcripts of the membrane receptor Npffr1 gene in the rat hypothalamus were visualized by RNAscope (magenta) in combination with immunostaining for kisspeptin (green). Bar = 50 μm. 3V, third ventricle.

Some of the newer high-sensitivity in situ hybridization methods have been commercialized as kits that include everything from probes to detection reagents. Among these commercialized in situ hybridization methods, RNAscope, which provides reagents and probes in drop bottles to simplify and shorten the experimental process, has been the most frequently used recently and has been accepted as a new standard method [37] (Fig. 2A). Because RNAscope is a commercial product, the details of the signal enhancement, including the linker and amplifier sequences, have not been disclosed.

One frequently reported variation in high-sensitivity in situ hybridization was hybridization chain reaction (HCR) in situ hybridization [10, 34] (Fig. 2B). This variant utilizes an HCR for signal amplification, in which two fluorescently labeled hairpin DNA strands are hybridized and elongated via a self-folding reaction using a partial sequence of the primary probe as a scaffold [13]. Amplification can be adjusted by the user based on the fact that the degree of amplification is proportional to the time of the chain reaction.

Of the recently developed fluorescent in situ hybridization variants, clampFISH and SABER FISH are important [12, 22, 31] (Fig. 2C, D). In clampFISH, primary probes that hybridizes to form a circular structure (padlock probes) are used, then the probes are fixed to the target sequence by ligation using click chemistry [5]. High sensitivity was achieved by repeated hybridization and chemical fixation of a fluorescently labeled probe to the loop portion of the primary probe. In SABER FISH, a primer exchange reaction was used to add a short repeating sequence to the end of the primary probe before hybridization (concatenation) [23], and the short fluorescent probe is hybridized to the repeating sequence. The degree of signal amplification can be adjusted by varying the length of the concatemers; however, longer concatemers are expected to reduce probe penetration into the tissue. In these highly sensitive in situ hybridization methods, gene transcripts are visualized as granular signals (Fig. 2E, right panel).

V. Characteristics of High-sensitivity In Situ Hybridization Variants

The aforementioned high-sensitivity in situ hybridization methods were used to visualize a single transcript molecule as a granular fluorescent signal under ideal conditions. This means that regardless of the method chosen, the signal enhancement is sufficient for practical use. Thus, researchers can select a method based on the cost of implementation. The characteristics of each method, including the monetary and time costs, are summarized in Table 1. For all variants, multicolor fluorescence staining was easier than conventional RNA probe in situ hybridization. In addition, the hybridization temperatures of these variants are relatively low, providing high antigen retention and facilitating the combination of these methods with immunostaining (Fig. 2E).

Table 1. .

Characteristics of each high-sensitivity in situ hybridization method

| Method | DIG-RNA ISH | RNAscope | HCR ISH | clampFISH | SABER FISH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty of experimental procedures | difficult | easy | moderate | moderate | moderate | |

| Coloration Method | fluorescent chromogenic | fluorescent chromogenic | fluorescent | fluorescent | fluorescent | |

| Multiplex staining | difficult under some conditions | easy | easy | easy | easy | |

| Probe design and synthesis | done by user (can be outsourced) | provided by manufacturer only | done by user (can be outsourced) | done by user | done by user | |

| Automated staining | applicable | applicable | — | — | — | |

| Monetary cost | total | low | high | moderate | moderate | moderate |

| per sample | low | high | decreases with increasing sample size | decreases with increasing sample size | decreases with increasing sample size | |

| Time cost | examination of experimental conditions | necessary | mostly unnecessary | necessary | necessary | necessary |

| staining time | 2–3 days | 1 day | 1–3 days | 1–3 days | 2–3 days | |

| Detection of microRNA | difficult | applicable | applicable | — | — | |

—: not reported.

RNAscope has several advantages among in situ hybridization variants: it can detect chemical chromogenesis as well as fluorescence and can be applied to automated pathology equipment [1, 37]. The major advantage of RNAscope is its efficiency and ease of operation; the experimental procedure is simple and easy to learn, and the staining itself can be completed in one day. This makes RNAscope the least time-costly method. The disadvantage of RNAscope is that it has the highest monetary cost per sample, with proportionate increase in costs with increasing number of samples. Therefore, it is more suited for a narrowly focused analysis than for analyzing a large number of samples or targets. For HCR in situ hybridization, clampFISH, and SABER FISH, primary probes for detection and fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes can be synthesized by outsourcing at moderate monetary costs [12, 22, 34]. The cost per sample decreased with the increasing number of samples, making it close to that of conventional in situ hybridization. However, as with conventional in situ hybridization, these three methods require time for the experimenter to design the probes and optimize the experimental conditions. RNAscope and HCR in situ hybridization have been reported to detect short targets, such as microRNAs [28, 38, 39], whereas clampFISH and SABER FISH have not yet been reported for short targets, although this could be possible. From the aforementioned characteristics of each method, the experimenter should choose a method based on whether multiple fluorescent staining is necessary, the number of samples to be analyzed, number of target transcripts, or length of the target transcripts.

VI. Conclusion

Although conventional in situ hybridization is a major histological technique, it is difficult to adopt due to the complexity of the procedure. However, via efforts to increase sensitivity and simplify the procedure described in this review, in situ hybridization can be used with relative ease for detecting low amounts of nucleic acids. In addition to the above, methodological improvements are still being actively pursued [3, 11]. Clinical applications in pathology and oncology are gradually increasing, including not only the detection of chromosomal aberrations, but also pathological diagnosis using automated in situ hybridization and analysis of intratumor heterogeneity using multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization [27, 36]. In situ hybridization has been refined methodologically, and researchers now have a wide range of sophisticated options for in situ hybridization variants. Therefore, in situ hybridization continues to be a practical and efficient method for research purposes.

VII. Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

VIII. References

- 1.Anderson, C. M., Zhang, B., Miller, M., Butko, E., Wu, X., Laver, T., et al. (2016) Fully Automated RNAscope In Situ Hybridization Assays for Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Cells and Tissues. J. Cell. Biochem. 117; 2201–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andras, S. C., Power, J. B., Cocking, E. C. and Davey, M. R. (2001) Strategies for signal amplification in nucleic acid detection. Mol. Biotechnol. 19; 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azevedo, A. S., Sousa, I. M., Fernandes, R. M., Azevedo, N. F. and Almeida, C. (2019) Optimizing locked nucleic acid/2’-O-methyl-RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (LNA/2’OMe-FISH) procedure for bacterial detection. PLoS One 14; e0217689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley Lawrence, J. and Singer, R. H. (1985) Quantitative analysis of in situ hybridization methods for the detection of actin gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 13; 1777–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besanceney-Webler, C., Jiang, H., Zheng, T., Feng, L., Soriano del Amo, D., Wang, W., et al. (2011) Increasing the efficacy of bioorthogonal click reactions for bioconjugation: a comparative study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50; 8051–8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop, R. (2010) Applications of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in detecting genetic aberrations of medical significance. Biosci. Horizons 3; 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitschopf, H., Suchanek, G., Gould, R. M., Colman, D. R. and Lassmann, H. (1992) In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes: sensitive and reliable detection method applied to myelinating rat brain. Acta Neuropathol. 84; 581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchwalow, I., Samoilova, V., Boecker, W. and Tiemann, M. (2011) Non-specific binding of antibodies in immunohistochemistry: fallacies and facts. Sci. Rep. 1; 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buongiorno-Nardelli, M. and Amaldi, F. (1970) Autoradiographic detection of molecular hybrids between RNA and DNA in tissue sections. Nature 225; 946–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi, H. M. T., Schwarzkopf, M., Fornace, M. E., Acharya, A., Artavanis, G., Stegmaier, J., et al. (2018) Third-generation in situ hybridization chain reaction: multiplexed, quantitative, sensitive, versatile, robust. Development 145; dev165753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choijookhuu, N., Shibata, Y., Ishizuka, T., Xu, Y., Koji, T. and Hishikawa, Y. (2022) An advanced detection system for in situ hybridization using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based molecular beacon probe. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 55; 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dardani, I., Emert, B. L., Goyal, Y., Jiang, C. L., Kaur, A., Lee, J., et al. (2022) ClampFISH 2.0 enables rapid, scalable amplified RNA detection in situ. Nat. Methods 19; 1403–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evanko, D. (2004) Hybridization chain reaction. Nat. Methods 1; 186. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritschy, J.-M. (2008) Is my antibody-staining specific? How to deal with pitfalls of immunohistochemistry. Eur. J. Neurosci. 28; 2365–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gozzetti, A. and Le Beau, M. M. (2000) Fluorescence in situ hybridization: uses and limitations. Semin. Hematol. 37; 320–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennig, W. (1973) Molecular Hybridization of DNA and RNA in Situ. In “International Review of Cytology”, ed. by G. H. Bourne, J. F. Danielli and K. W. Jeon, Academic Press, pp. 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higo, S., Honda, S., Iijima, N. and Ozawa, H. (2016) Mapping of Kisspeptin Receptor mRNA in the Whole Rat Brain and its Co-Localisation with Oxytocin in the Paraventricular Nucleus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 28. doi: 10.1111/jne.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higo, S., Kanaya, M. and Ozawa, H. (2021) Expression analysis of neuropeptide FF receptors on neuroendocrine-related neurons in the rat brain using highly sensitive in situ hybridization. Histochem. Cell Biol. 155; 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen, C. B., Pyke, C., Rasch, M. G., Dahl, A. B., Knudsen, L. B. and Secher, A. (2018) Characterization of the Glucagonlike Peptide-1 Receptor in Male Mouse Brain Using a Novel Antibody and In Situ Hybridization. Endocrinology 159; 665–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen, E. (2014) Technical Review: In Situ Hybridization. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 297; 1349–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin, L. and Lloyd, R. V. (1997) In situ hybridization: Methods and applications. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 11; 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishi, J. Y., Lapan, S. W., Beliveau, B. J., West, E. R., Zhu, A., Sasaki, H. M., et al. (2019) SABER amplifies FISH: enhanced multiplexed imaging of RNA and DNA in cells and tissues. Nat. Methods 16; 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishi, J. Y., Schaus, T. E., Gopalkrishnan, N., Xuan, F. and Yin, P. (2018) Programmable autonomous synthesis of single-stranded DNA. Nat. Chem. 10; 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komminoth, P. (1992) Digoxigenin as an alternative probe labeling for in situ hybridization. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 1; 142–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komminoth, P., Merk, F. B., Leav, I., Wolfe, H. J. and Roth, J. (1992) Comparison of 35S- and digoxigenin-labeled RNA and oligonucleotide probes for in situ hybridization. Expression of mRNA of the seminal vesicle secretion protein II and androgen receptor genes in the rat prostate. Histochemistry 98; 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langdale, J. A. (1994) In situ Hybridization. In “The Maize Handbook”, ed. by M. Freeling and V. Walbot, Springer, New York, NY, pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei, H., Gertz, E. M., Schäffer, A. A., Fu, X., Tao, Y., Heselmeyer-Haddad, K., et al. (2021) Tumor heterogeneity assessed by sequencing and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) data. Bioinformatics 37; 4704–4711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, L., Feng, J., Liu, H., Li, Q., Tong, L. and Tang, B. (2016) Two-color imaging of microRNA with enzyme-free signal amplification via hybridization chain reactions in living cells. Chem. Sci. 7; 1940–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moench, T. R., Gendelman, H. E., Clements, J. E., Narayan, O. and Griffin, D. E. (1985) Efficiency of in situ hybridization as a function of probe size and fixation technique. J. Virol. Methods 11; 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozawa, M., Hattori, Y., Higo, S., Otsuka, M., Matsumoto, K., Ozawa, H., et al. (2022) Optimized Mouse-on-mouse Immunohistochemical Detection of Mouse ESR2 Proteins with PPZ0506 Monoclonal Antibody. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 55; 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouhanifard, S. H., Mellis, I. A., Dunagin, M., Bayatpour, S., Jiang, C. L., Dardani, I., et al. (2018) ClampFISH detects individual nucleic acid molecules using click chemistry-based amplification. Nat. Biotechnol. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teixeira, H., Sousa, A. L. and Azevedo, A. S. (2021) Bioinformatic Tools and Guidelines for the Design of Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Probes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2246; 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thul, P. J. and Lindskog, C. (2018) The human protein atlas: A spatial map of the human proteome. Protein Sci. 27; 233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuneoka, Y. and Funato, H. (2020) Modified in situ Hybridization Chain Reaction Using Short Hairpin DNAs. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13; 75. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uhlen, M., Zhang, C., Lee, S., Sjöstedt, E., Fagerberg, L., Bidkhori, G., et al. (2017) A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science 357; eaan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voith von Voithenberg, L., Fomitcheva Khartchenko, A., Huber, D., Schraml, P. and Kaigala, G. V. (2020) Spatially multiplexed RNA in situ hybridization to reveal tumor heterogeneity. Nucleic Acids Res. 48; e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, F., Flanagan, J., Su, N., Wang, L. C., Bui, S., Nielson, A., et al. (2012) RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 14; 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin, V. P. (2018) In Situ Detection of MicroRNA Expression with RNAscope Probes. Methods Mol. Biol. 1649; 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuang, P., Zhang, H., Welchko, R. M., Thompson, R. C., Xu, S. and Turner, D. L. (2020) Combined microRNA and mRNA detection in mammalian retinas by in situ hybridization chain reaction. Sci. Rep. 10; 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]