Abstract

The treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus, which is characterized by defective insulin secretion and/or the inability of tissues to respond to insulin, has been studied for decades. Many studies have focused on the use of incretin-based hypoglycemic agents in treating type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). These drugs are classified as GLP-1 receptor agonists, which mimic the function of GLP-1, and DPP-4 inhibitors, which avoid GLP-1 degradation. Many incretin-based hypoglycemic agents have been approved and are widely used, and their physiological disposition and structural characteristics are crucial in the discovery of more effective drugs and provide guidance for clinical treatment of T2DM. Here, we summarize the functional mechanisms and other information of the drugs that are currently approved or under research for T2DM treatment. In addition, their physiological disposition, including metabolism, excretion, and potential drug–drug interactions, is thoroughly reviewed. We also discuss similarities and differences in metabolism and excretion between GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors. This review may facilitate clinical decision making based on patients' physical conditions and the avoidance of drug–drug interactions. Moreover, the identification and development of novel drugs with appropriate physiological dispositions might be inspired.

Key words: T2DM, Incretins-based hypoglycemic agents, GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors, Physiological disposition, Metabolism, Excretion, Drug–drug interactions

Graphical abstract

GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors are focused on GLP-1, an incretin peptide stimulate secretion of insulin. The physiological disposition of them is of great significance.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease that is caused by defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both, resulting in hyperglycemia. It is believed that chronic hyperglycemia caused by diabetes does long-term harm to many organs such as the eyes and kidneys1. Diabetes can cause some serious complications such as heart failure2, diabetic nephropathy3, and diabetic foot4, which not only harm patients but also cause large burdens to society5.

A series of methods have been developed to treat diabetes, including herb treatment6, acupuncture7, physical exercise8, food supplements9, surgery10, and drug treatment. Drug treatment is the most widely used and efficient method. Insulin-stimulating agents promote insulin release through interaction with specific receptors11; metformin-type agents can suppress hepatic glucose production12; thiazolidinedione-type agents reduce insulin resistance by increasing insulin-dependent glucose secretion and reducing the production of hepatic glucose13; α-glucosidase inhibitors can competitively inhibit α-glucosidase and cause delayed glucose absorption in the small intestine14; insulin, which has been used in diabetes treatment for decades, can regulate blood glucose levels15; insulin analogs modulate the ability of insulin to control blood glucose levels16; and incretin-based hypoglycemic agents stimulate insulin secretion from β-cells17,18.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is characterized by destruction of insulin-producing cells19, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is characterized by defective insulin secretion and the inability of tissues to properly respond to insulin20. T1DM is influenced by the immune system, while T2DM is influenced by metabolism21. The number of people with T2DM is larger than the number of people with T1DM22, and treatment methods for T2DM are still in development.

In treating T2DM, incretin-based hypoglycemic agents are among the most recently developed agents. Incretins are gut peptides, which could stimulate the secretion of insulin combined with glucagon (GCG). GCG-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are two important incretins23. Many polypeptide compounds mimicking their functions have been produced. However, these peptides are rapidly degraded at their N-termini by dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP-4). Thus, DPP-4 could also serve as a potential target for diabetes treatment. By inhibiting DDP-4, the half-lives of GLP-1 and its analogs could be extended24. GLP-1 receptor agonists (RAs) and DPP-4 inhibitors have already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and commercialized25,26.

Although incretin-based hypoglycemic agents have been widely studied, their metabolic processes and drug–drug interactions have not been comprehensively reviewed. In this review, we summarize the characteristics and metabolic processes of incretin-based hypoglycemic drugs. To our knowledge, the metabolism and excretion of GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors have not been reviewed before. This review provides information for their clinical use, as well as instructions for more comprehensive research in the field of incretin-based hypoglycemic drugs. Some modifications could be made to incretin-based drugs to improve T2DM treatment.

2. Current incretin-based hypoglycemic agents

2.1. GLP-1 receptor agonists

GLP-1, an endogenous incretin hormone consisting of 30 amino acids, is produced by enteroendocrine L-cells27. It could decrease glycemia in many ways, such as by influencing insulin secretion, delaying gastric emptying, improving lipid metabolism, and promoting the efficiency of pancreatic β-cells28,29. GLP-1 has become a therapeutic target in treating T2DM, which could be activated by GLP-1 RAs to improve the tolerance to glucose and reduce the hazards of hypoglycemia. GLP-1 RAs might also have the potential to slow disease progression30,31. Currently approved GLP-1 RAs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Names and chemical structures of some GLP-1 receptor agonists currently on market.

| Number | Name | Manufacturer | Trade name | Sequence detail | Date of approval by FDA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exenatide | Amylin/Eli Lilly | Byetta™ | HGEGTFTSDL SKQMEEEAVR LFIEWLKNGG PSSGAPPPS | 28th Apr, 2005 | 32, 33 |

| (Terminal mod. at Ser-39, C-terminal amide) | ||||||

| 2 | Liraglutide | Novo Nordisk | Victoza® | Seq | 25th Jan, 2010 | |

| HAEGTFTSDV SSYLEGQAAK EFIAWLVRGR G | 34, 35, 36, 37 | |||||

| Seq' | ||||||

| E | ||||||

| (Amide bridge between Lys-20-Glu-1′) | ||||||

| 3 | Albiglutide | GlaxoSmithKline | Tanzeum | HGEGTFTSDV SSYLEGQAAK EFIAWLVKGR HGEGTFTSDV SSYLEGQAAK EFIAWLVKGR DAHKSEVAHR FKDLGEENFK ALVLIAFAQY LQQCPFEDHV KLVNEVTEFA KTCVADESAE NCDKSLHTLF GDKLCTVATL RETYGEMADC CAKQEPERNE CFLQHKDDNP NLPRLVRPEV DVMCTAFHDN EETFLKKYLY EIARRHPYFY APELLFFAKR YKAAFTECCQ AADKAACLLP KLDELRDEGK ASSAKQRLKC ASLQKFGERA FKAWAVARLS QRFPKAEFAE VSKLVTDLTK VHTECCHGDL LECADDRADL AKYICENQDS ISSKLKECCE KPLLEKSHCI AEVENDEMPA DLPSLAADFV ESKDVCKNYA EAKDVFLGMF LYEYARRHPD YSVVLLLRLA KTYETTLEKC CAAADPHECY AKVFDEFKPL VEEPQNLIKQ NCELFEQLGE YKFQNALLVR YTKKVPQVST PTLVEVSRNL GKVGSKCCKH PEAKRMPCAE DYLSVVLNQL CVLHEKTPVS DRVTKCCTES LVNRRPCFSA LEVDETYVPK EFNAETFTFH ADICTLSEKE RQIKKQTALV ELVKHKPKAT KEQLKAVMDD FAAFVEKCCK ADDKETCFAE EGKKLVAASQ AALGL | 15th Apr, 2014 | 38, 39 |

| (Amide bridges between Cys-113–Cys-122; Cys-135–Cys-151; Cys-150–Cys-161; Cys-184–Cys-229; Cys-228–Cys-237; Cys-260–Cys-306; Cys-305–Cys-313; Cys-325–Cys-339; Cys-338–Cys-349; Cys-376–Cys-421; Cys-420–Cys-429; Cys-452–Cys-498; Cys-497–Cys-508; Cys-521–Cys-537; Cys-536–Cys-547; Cys-574–Cys-619; Cys-618–Cys-627) | ||||||

| 4 | Dulaglutide | Eli Lilly | Trulicity™ | Seq | 9th Sep, 2014 | |

| HGEGTFTSDV SSYLEEQAAK EFIAWLVKGG GGGGGSGGGG SGGGGSAESK YGPPCPPCPA PEAAGGPSVF LFPPKPKDTL MISRTPEVTC VVVDVSQEDP EVQFNWYVDG VEVHNAKTKP REEQFNSTYR VVSVLTVLHQ DWLNGKEYKC KVSNKGLPSS IEKTISKAKG QPREPQVYTL PPSQEEMTKN QVSLTCLVKG FYPSDIAVEW ESNGQPENNY KTTPPVLDSD GSFFLYSRLT VDKSRWQEGN VFSCSVMHEA LHNHYTQKSL SLSLG | 40, 41, 42 | |||||

| Seq' | ||||||

| HGEGTFTSDV SSYLEEQAAK EFIAWLVKGG GGGGGSGGGG SGGGGSAESK YGPPCPPCPA PEAAGGPSVF LFPPKPKDTL MISRTPEVTC VVVDVSQEDP EVQFNWYVDG VEVHNAKTKP REEQFNSTYR VVSVLTVLHQ DWLNGKEYKC KVSNKGLPSS IEKTISKAKG QPREPQVYTL PPSQEEMTKN QVSLTCLVKG FYPSDIAVEW ESNGQPENNY KTTPPVLDSD GSFFLYSRLT VDKSRWQEGN VFSCSVMHEA LHNHYTQKSL SLSLG | ||||||

| (Disulfide bridges between Cys-55–Cys-55′ and Cys-58–Cys-58′) | ||||||

| 5 | Lixisenatide | Sanofi-Aventis | Lyxumia® | HGEGTFTSDL SKQMEEEAVR LFIEWLKNGG PSSGAPPSKK KKKK | 27th Jul, 2016 | 43, 44 |

| (Terminal mod. at Ser-39, C-terminal amide) | ||||||

| 6 | Semaglutide | Novo Nordisk | Ozempic® | Seq | 5th Dec, 2017 | 45, 46, 47, 48 |

| HXEGTFTSDV SSYLEGQAAK EFIAWLVRGR G | ||||||

| Seq' | ||||||

| XXX | ||||||

| (Amide bridge between Lys-20–Oaa-3′; Aib-2, Ggu-1′, Oaa-2′, Oaa-3′ uncommon amino acids) | ||||||

| 7 | Tirzepatide | Eli Lilly | YXEGTFTSDY SIXLDKIAQK AFVQWLIAGG PSSGAPPPS | 13th May, 2022 | 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 | |

| (Terminal mod. at Ser 39, C-terminal amide; Ain-2, Aib-13 uncommon amino acids) |

The first FDA-approved GLP-1 RA is exenatide32, which is an incretin-mimicking peptide. It is a synthetic form of the naturally occurring exendin-433, which has the ability to regulate glucose levels. Five years later, liraglutide34 was approved by the FDA, which functionally and structurally mimics human endogenous GLP-1. Both consist of a single chain and have some amino acid alterations or are modified with some functional groups to avoid degradation by DPP-4. Exenatide shares 53% amino acid sequence identity with human GLP-1; a major difference is that at position 2, exenatide has an alanine substitution in GLP-1, extending its plasma half-life. Liraglutide shares 97% amino acid sequence homology with human endogenous GLP-1; liraglutide is modified by a fatty acid bound to an albumin molecule, extending its half-life35, 36, 37. The drugs approved in the early stage have been proved to be useful; however, their clinical profiles could be further improved, for example, by adding some functional groups or changing dosage forms.

GLP-1 RAs, which were approved later, have different chemical structures. They structurally mimic GLP-1, and they harbor amino acid substitutions or modifications with some functional groups. Additionally, major changes in their peptide chains have been made. Albiglutide38 is a GLP-1 RA that consists of two copies of modified human GLP-1, both containing fragments from amino acid residues 7 to 36 with a minor modification from alanine to glycine. One copy's C-terminus is fused with another copy's N-terminus, whose C-terminus is connected with human albumin39. Dulaglutide40 is a fusion protein consisting of two identical chains linked by disulfide bonds. Each chain contains a sequence that is similar to human GLP-1, which could be covalently linked by a small peptide linker to modified human IgG4 heavy chain fragment41. In the part that is analogous to GLP-1, some of the amino acids are substituted to increase solubility, protecting it from degradation by DPP-4 and optimizing its clinical profile42. The structure of lixisenatide43 is modified from exendin-4, with six lysine residues at its C-terminus. This drug has great affinity to the native human GLP-1 receptor, and its modified structure avoids degradation by DPP-4, enhancing its half-life30,44.

Some new ideas came up in designing GLP-1 RAs, in which synthetic amino acids are used in improving pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. For example, semaglutide45 contains two amino acid substitutions compared with human GLP-1, with alanine changed to alpha-amino isobutyric acid at position 8 and lysine to arginine at position 34. The lysine at position 26 was acylated and linked to a glutamic acid moiety combined with a C-18 fatty diacid side chain46,47. Owing to these structural modifications, it has a long half-life, making it possible to have only one subcutaneous administration per week. It has also been reported that this drug has better efficiency in controlling weight and treating obesity47,48. Currently approved GLP-1 RAs generally are based on the scaffold of either naturally occurring exendin-4 or human endogenous GLP-1. Further investigations on whether other peptide chains can be used need to be conducted in the future.

Besides modifying structures, some companies set their eyes on new targets in designing drugs, considering that not only GLP-1 but also other targets might be used to treat T2DM. Tirzepatide49 is a dual GIP and GLP-1 RA. A pharmacology study indicated that this drug has higher affinity to the GIP receptor, meaning that its effects are mediated to a higher extent by the GIP receptor than the GLP-1 receptor50,51. Tirzepatide is a linear peptide whose structure is modified from GIP, with a C-20 fatty diacid moiety linked to the lysine at position 2052,53. The dual target could improve T2DM treatment, and this strategy could stimulate the design of new compounds.

In addition to the above approved drugs, many other compounds are still being researched. Their chemical structures are shown in Table 2. LY3502970 is a small-molecule GLP-1 RA with a binding pocket in the upper helical bundle, which might enable its binding to the extracellular domain54. It is a partial agonist, which is biased toward cAMP accumulation55. NNC0090-2746 is a fatty-acylated dual GIP/GLP-1 RA, reported to be a promising compound for treating T2DM with generally good tolerance56. Its structure contains an α-aminoisobutyric acid residue at position 2 to avoid degradation by DPP-457. It shows a balanced agonist activity to GIP and GLP-1, but not to other related receptors. DA4-JC and DA5-CH, dual GIP/GLP-1 RAs, could be used to treat not only T2DM, but also Alzheimer's disease58,59. Recently, it was reported that some nonpeptide GLP-1 RAs could be administered orally. Cotadutide, produced by AstraZeneca, is a dual GLP-1/GCG RA used for treating T2DM. SAR44125, launched by Integrated Drug Discovery Germany, has a structure based on exendin-4 with some amino acid modifications to increase stability. It is a potent unimolecular peptide, which could function as a triple GLP-1/GIP/GCG RA60. We believe that some drug candidates with proper modified structures could be commercialized soon and we hope some novel GLP-1 RAs will be designed.

Table 2.

Names and chemical structures of some DPP-4 inhibitors currently on market.

| Number | Name | Manufacturer | Trade name | Chemical structure | Date of approval by FDA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sitagliptin | Merck | Januvia™; Glactiv®; Tesavel® |  |

16th Oct, 2006 | 62, 63, 64, 65 |

| 2 | Saxagliptin | AstraZeneca | Onglyza™ |  |

31st Jul, 2009 | 66, 67 |

| 3 | Linagliptin | Eli Lilly and Company | Trajenta® |  |

2nd May, 2011 | 68, 69, 70, 71 |

| 4 | Alogliptin | GlaxoSmithKline | Tanzeum |  |

25th Jan, 2013 | 72, 73, 74, 75 |

| 5 | Vildagliptin | Novartis | Galvus®; Jalra®; Xiliarx® |  |

Not by FDA (30th Nov, 2008 by European Medicines Agency) | 76, 77, 78, 79 |

| 6 | Gemigliptin | LG Life Sciences | Zemiglo® |  |

Not by FDA (Jun, 2012 by Korea Food and Drug Administration) | 80, 81, 82, 83, 84 |

| 7 | Teneligliptin | Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma | Tenelia® |  |

Not by FDA (Sep, 2012 by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency) | 85, 86, 87, 88 |

| 8 | Omarigliptin | Merck | Marizev® |  |

Not by FDA (Nov, 2015 by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency) | 89, 90 |

2.2. DPP-4 inhibitors

DPP-4 is a 110-kDa glycoprotein expressed on the surface of many cells, which could cleave N-terminal dipeptides from incretin hormones. Thus, DPP-4 is believed to be an important target for diabetes treatment because it could degrade GLP-1, an incretin functioning in post-prandial insulin secretion61. DPP-4 inhibition has potential for T2DM treatment. Currently approved DPP-4 inhibitors are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Names and chemical structures of known GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors currently in research.

Sitagliptin62,63 is the first oral DPP-4 inhibitor that was approved by the FDA. The chemical structure of the drug contains a β-aminoacyl amide scaffold. According to a study of the structure–activity relationship (SAR), this drug could be highly potent and highly selective to DPP-464. A long-term study showed that sitagliptin administration does not bring about additional safety concerns65. Two years later, another DPP-4 inhibitor, saxagliptin, was approved by the FDA. Saxagliptin can be combined with other agents such as metformin or insulin to treat T2DM patients with mild or severe renal impairment66. According to a SAR study, the tyrosine residues at positions 662 and 470 may be the key residues for DPP-4 inhibition. Saxagliptin was also reported to inhibit human thyroid carcinoma cell migration via the NRF2/HO1 pathway67. Contrary to previously approved drugs, which are mainly excreted through urine, linagliptin68 is predominantly eliminated nonrenally. The dosage form containing linagliptin/metformin is known as Jentadueto®69. According to SAR studies, it has two binding interactions with the target70. There are no safety and practical concerns about this drug if administered at a routine dosage71.

New drugs with favorable physical properties could be designed using structure-based design technology. It is hypothesized that alogliptin should contain a quinazolinone scaffold and some other chemical structures are put in the other pocket72,73. SAR studies comparing alogliptin with other structures emphasized the importance of the above chemical structure74. The synthesis process was also improved to get a better enantioselective synthesis pathway75. From the perspective of long-term treatment, alogliptin does not cause severe safety issues and it is a promising agent controlling glucose levels72. Besides improving efficacy by designing drugs with different chemical structures, coupling some drugs might be another choice. Vildagliptin alone76 could act as a DPP-4 inhibitor in T2DM treatment, and it could also be combined with metformin. Some formulations combine metformin with vildagliptin, such as Eucreas®, Icandra®, and Zomarist®77. Other formulations, such as combinations of vildagliptin with gold or silver nanoparticles, could reduce IC50, improving the inhibitory effects on DPP-478. Vildagliptin is safe during long-term therapy79. Since some scaffolds of DPP-4 have already been proved useful, some new modifications based on them could be made to improve drugs' clinical profiles.

To improve selectivity and efficacy, gemigliptin80 has a totally different structure from other DPP-4 inhibitors, for it is a pyrimidine piperidine derivative81. Combination of this drug with insulin or other anti-diabetes drugs results in good efficiency and tolerance82. Gemigliptin alone is also believed to be well tolerated with no extra influence on body weight83. In addition, this drug was believed to prevent the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via Nrf284. Teneligliptin also has a unique chemical structure, with five consecutive rings forming a “J-shaped” structure85,86. Long-term use of this drug is not associated with efficiency and safety issues87. There have been some reports that teneligliptin has potential to treat radiation-induced cardiotoxicity by reducing the expression of IL-1β and MCP-1, inhibiting activation of NF-κB and improving the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio88. In improving the pharmacokinetic profile, it must be considered whether DPP-4 inhibitors are administered daily, weekly, or monthly. Omarigliptin was approved as an orally administered DPP-4 inhibitor for weekly use89. This drug is generally well tolerated and could help control blood glucose levels clinically90. Different chemical structures could lead to significant changes in physiological disposition, especially the drugs' half-lives. As a result, their clinical profiles might be improved by designing structures that avoid degradation.

In addition to the currently available drugs, some compounds acting as DPP-4 inhibitors are still being studied. Their chemical structures are shown in Table 2. HSK-765391 has entered a Phase I clinical trial. HSK-7653 is a synthetic analog of omarigliptin92 and employs fluorine to enhance its pharmacological efficacy, metabolic stability, and membrane permeability93. DBPR108 is an orally active synthetic selective small-molecule DPP-4 inhibitor. It could bind to DPP-4 reversibly and covalently and dissociate slowly. DBPR108 could be considered as a well-tolerated drug candidate, but it is associated with adverse effects including hypoglycemia and mild or moderate abnormal liver function. DBPR108 could inhibit DPP-4 in a dose-dependent manner in the range of 25–600 mg, which could inhibit the target for >24 h. It is currently being tested for T2DM treatment in a phase II clinical trial94. TQ-F3083 is a promising highly selective DPP-4 inhibitor that is generally safe without serious adverse effects for treating T2DM. At 1 h after administration, it achieves its maximal inhibitory effects. At 24 h after administration of 5 mg, >80% DPP-4 inhibition could still be observed95. Hopefully, more DPP-4 inhibitors will be developed soon.

3. Metabolism and elimination of incretin-based hypoglycemic agents

3.1. GLP-1 receptor agonists

3.1.1. Exenatide

In humans, exenatide is mainly degraded in the kidney, but significant species differences have been observed. In human, the cleavage sites lie between amino acids 21/22 and 22/23. Exenatide is further degraded by kidney membranes into peptides of less than three amino acids. Liver impairment seems not to influence the elimination and degradation of exenatide. Exenatides 1–22 and 23–39 cannot act as agonists or antagonists96. The plasma concentration increases in a dose-dependent manner. The mean half-life of exenatide ranges from 3.3 to 4 h and the median time to peak (Tmax) is approximately 2.2 h97. For patients with renal impairment, exenatide clearance is remarkably slower98. Exenatide interactions with other drugs generally affect gastric emptying, which depends on the administration time of exenatide. It has been reported that oral drugs should be administered no less than 1 h before using exenatide to avoid drug interactions36. When combining acetaminophen use with exenatide, there is no significant effect on exenatide pharmacokinetics99. PEGylated exenatide has been produced, which could significantly improve its pharmacokinetic performance100. Considering that the drug is not friendly to patients with renal impairment, there is a need to optimize its chemical structure to make it suitable for specific patients.

3.1.2. Liraglutide

Liraglutide is cleaved by DPP-4 between Ala-8 and Glu-9, and the products could be further degraded by neutral endopeptidase into several metabolites. Chromatographic performance of metabolized liraglutide is similar to that of metabolized GLP-1. No liraglutide can be detected in urine and feces, and a low amount of liraglutide can be detected in plasma, indicating that liraglutide is completely degraded in the body101. The mean half-life of the drug is 13.5 h. The pharmacokinetics are not significantly affected by gender and age. However, body weight might influence the area under the curve (AUC), which decreases with increasing body weight102,103. Within the range of 0.6–3 mg, the amount of exposure increases in a dose-dependent manner. The rate of clearance is about 0.9–1.4 L/h104. As regards drug interactions, liraglutide has potential to interact with cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes and to bind to plasma proteins. Moreover, interactions of liraglutide with other orally administered drugs such as acetaminophen may influence processes such as gastric emptying105. Insulin administration does not alter the pharmacokinetic profile of liraglutide106. The fact that liraglutide functionally and structurally mimics an endogenous polypeptide might be related to the almost complete lack of pharmacokinetic interactions. This could inspire drug design, improving the physiological disposition of related drugs.

3.1.3. Albiglutide

Albiglutide is metabolized by urine ubiquitous proteolytic enzymes in vascular endothelium107. Albiglutide has a molecular size of 73 kDa and is degraded into small peptides and some single amino acids. It cannot be cleared in the glomeruli in a normal state108. It is predominantly absorbed via the lymphatic circulation. Age and body weight affect clearance of albiglutide109. It has a half-life of approximately 5 days and it can maintain a steady-state level after 4–5 days. Albiglutide could be excreted through the kidneys, and body clearance is 67 mL/h107. In patients with renal impairment, albiglutide exposure increases by 30%–40%110. Co-administration of albiglutide with digoxin or warfarin is safe at an appropriate dose without the need for dosage adjustment111. Thus, these combinations might be safe for T2DM treatment in patients who also receive treatment for cardiovascular diseases. However, this drug greatly influences the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin, decreasing AUC by 40%; however, its maximum concentration (Cmax) increased by 18%112. Unlike previously approved drugs having one chain, which functionally and structurally mimic endogenous peptides, albiglutide's structure extends its half-life, providing new ideas for future development of GLP-1 RAs.

3.1.4. Dulaglutide

Dulaglutide is metabolized through general protein catabolism pathways; it is degraded into small polypeptides, and it cannot be eliminated through glomerular filtration or CYP450 enzymes113. There is no significant difference in dulaglutide pharmacokinetics between healthy volunteers and T2DM patients. Dulaglutide has a low absorption rate, and its Cmax is reached within 24–72 h, with a median of 48 h. A steady plasma concentration could be maintained for 2–4 weeks. The elimination half-life at a dose of 0.75 or 1.5 mg is around 5 days. Patients with either mild or severe renal or liver failure show no clinical change in some pharmacokinetics data such as AUC and Cmax41. Dulaglutide could cause delayed gastric emptying. Patients with T2DM often experience gastrointestinal disorders. Thus, interactions with orally administered drugs should be investigated. It has been reported that dulaglutide does not strongly affect the pharmacokinetic profile data of digoxin, warfarin, and atorvastatin if they are administered together114. However, co-administration with rapid gastrointestinal absorption drugs still requires attention115. Although delayed gastric emptying might help treating T2DM by delaying postprandial glycemia, pharmacokinetic properties would also be influenced116. Whether drug structures could be modified to have both advantages, delayed postprandial glycemia and improved pharmacokinetic properties, need to be studied.

3.1.5. Lixisenatide

Lixisenatide is a polypeptide that is generally excreted as a full-length endogenous peptide, which can be filtered by the kidneys, reabsorbed by the tubular structures, and subsequently metabolized. The CYP450 enzymes do not participate in its metabolism. All metabolites that could be detected are polypeptides resulting from lixisenatide degradation117. The half-life of lixisenatide is in the range of 2.7–4.3 h. AUC and Cmax increase with increasing doses and dosing frequencies, where the concentration of 20 μg has the largest AUC44,118. In patients with renal impairment, lixisenatide is generally well tolerated and has good efficiency119. Lixisenatide could cause delayed gastric emptying, which could reduce the orally administered drug absorption rate. In normal treatment with ethinylestradiol, levonorgestrel, and atorvastatin, there is no need to adjust the dose120. The good tolerance of lixisenatide in patients with renal impairment might provide valuable structural features to avoid renal influence.

3.1.6. Semaglutide

The bioavailability of semaglutide is 94%121, and in humans, most semaglutide (83%) circulates as a primary component in the plasma. It can be injected or given orally, where the oral form is co-administered with an absorption enhancer122. The drug is metabolized prior to excretion, which takes place slowly and primarily in the urine. Besides semaglutide, a total of six metabolites were identified in human plasma, which account for 7.7%. This metabolite contains a His-7–Tyr-19 sequence. The metabolites are commonly formed following proteolytic cleavage in the peptide backbone area and β-oxidation of the fatty acid side chain. Of the drug, 53% could be recovered in urine, 18.6% in feces, and 3.2% in expired air. The parent drug and 21 metabolites could be detected in urine, and no parent drug could be found in feces121,123. For orally given doses, whose median Tmax was 1.5 h for a single dose124, the steady state was achieved after 4–5 weeks. The half-life is approximately 1 week and it could be maintained in the circulation for about 5 weeks125. After giving multiple doses, the AUC ranges from 19.7% to 34.9%, while the total variability ranges between 63.6% and 84.4%122. For the injection dose, semaglutide could reach its Cmax within 24–56 h. The metabolite levels decline over time in plasma and only the parent drug could be detected at 28 days after administration121. Thus, the pharmacokinetics of semaglutide could be influenced in patients with liver impairment126. However, the pharmacokinetics of semaglutide are not influenced by renal impairment127. Drug interactions in semaglutide can cause a delay in gastric emptying. Semaglutide was reported to potentially increase the AUC of metformin, but it does not increase the half-lives of lisinopril and warfarin. It was also shown that semaglutide does not affect the bioavailability of the contraceptive drugs ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel128. The two different dosage forms of semaglutide provided patients with more choices. However, since semaglutide is mainly metabolized in the liver, we hope that it could be modified for suitable use in patients with liver injury.

3.1.7. Tirzepatide

Tirzepatide is primarily metabolized via catabolism of the peptide backbone and β-oxidation of the diacid chain. The parent drug is the primary metabolite in circulation, accounting for more than 80% in both monkeys and rats. The drug is mainly excreted through urine and feces129. This drug can cause delayed gastric emptying, as also reported for other GLP-1 RAs130. In healthy volunteers, Cmax increases in a dose-dependent manner within the range of 26–874 ng/mL at a dosage between 0.25 and 8.0 mg, while Tmax occurs in the range of 1–2 days after administration. The half-life is 116.7 h, which is almost 5 days131. For patients with renal impairment, the pharmacokinetic profile is not influenced by renal function132. Compared with other drugs, tirzepatide is superior to titrated insulin degludec49 and metformin133. Since tirzepatide is a dual GLP-1/GIP RA, whether the structure designed for dual targets could influence pharmacokinetic profiles needs further investigation.

3.1.8. Other candidates in clinical trials

LY3502970 is a small-molecule agonist with good oral delivery properties54. It has a bioavailability of 21%–28% in cynomolgus monkeys. Compared with exenatide, LY3502970 could achieve insulin secretion after giving a dose of 5.4 mg/kg, while reaching an anorexigenic effect after administration at 0.05 mg/kg134. Small-molecule GLP-1 RAs could reduce current drawbacks such as delayed gastric emptying and improve bioavailability. NNC0090-2746 achieved its Cmax at 2–3 h after injection, while Cmax could be delayed to up to 4 h after receiving a dose of 0.6 mg. The elimination process is recognized as biphasic, having a half-life of 19–25 h, and AUC and Cmax slightly increased in a dose-dependent manner. A cotadutide dose of >100 μg in healthy volunteers in East Asia could suppress postprandial glucose and insulin levels. Its trough plasma concentrations could be achieved within 5 days at a concentration of 50 μg and increased in a dose-dependent manner135. Cotadutide has a Tmax of 4–6 h and a half-life of 8–9 h136. Cotadutide is generally safe, and the most significant adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, and malaise135. This drug is still in development and has not been approved by any drug administration authorities. We hope that more drugs with better physiological disposition will be developed to overcome major drawbacks such as delayed gastric emptying.

3.2. DPP-4 inhibitors

3.2.1. Sitagliptin

14C-Labeled sitagliptin was used to study its absorption, metabolism, and elimination in humans. Its bioavailability was reported to be 87%137. The majority of sitagliptin is excreted through the kidney; 87% of the drug could be recovered in urine, while the other 13% is excreted through the feces. With respect to its metabolic process, 16% is excreted as metabolites, where urines take up 13% and feces take up 3%. The metabolites are N-sulfate derivates, N-carbamoyl glucuronic acid derivates, a mixture of hydroxylated derivatives, an ether glucuronide of a hydroxylated metabolite, and two metabolites formed by oxidative desaturation of the piperazine ring followed by cyclization. The main enzyme in the metabolic process is CYP3A4, while CYP2C8 also makes a minor contribution138. At a dose of 1.5–600 mg, plasma sitagliptin levels increase almost proportionally, and its half-life is approximately 8–14 h, while Tmax values varied from 1 to 6 h based on the dosage. The renal clearance of sitagliptin is about 388 mL/min139. Researchers recognized that in patients with liver injury, although pharmacokinetic analysis showed a slight increase in Cmax, this would not affect drug use140. Sitagliptin, when combined with grapefruit, may interact with the metabolism of many drugs; serum sitagliptin levels increase, but there is no significant change in the process of total elimination and residence time141. Drug interaction with lobeglitazone, a drug used for treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in T2DM142, showed no significant change in pharmacokinetics, meaning that no dose adjustment is needed when combining these two drugs143. A combination of Tinospora cordifolia aqueous extract, which is beneficial to diabetes patients as a complementary treatment with sitagliptin, showed no significant change in pharmacokinetics144. Daily food intake might show interactions with sitagliptin, which is caused by interactions with CYP450 enzymes. Further research on how to avoid these interactions, reducing effects on patients' daily routine, should be carried out.

3.2.2. Saxagliptin

The main metabolic component of saxagliptin is the parent drug, and 5-hydroxy-saxagliptin also is an active metabolite. Other metabolites may be produced by hydroxylation at other positions, and the parent drug may be conjugated with glucuronide or sulfate. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 play important roles in forming metabolites, where the activity of CYP3A4 is much higher than that of CYP3A5145. Within 7 days, 97% of the drug could be eliminated in the excreta, i.e., 74.9% in urine and 22.1% in feces. The major components in excreta are the parent drug (24.0%) and 5-hydroxy-saxagliptin (44.1%). Saxagliptin is mainly eliminated through renal and hepatic routes. The half-lives of saxagliptin and 5-hydroxy-saxagliptin are 6.7 and 8.1 h, respectively146. Its bioavailability is reported to be around 50%–75%147. In addition, patients with renal failure should pay attention when taking this drug since the AUC values of saxagliptin and 5-hydroxy-saxagliptin are 108% and 347% higher than in patients with normal renal function, respectively148. As regards drug interactions, combination with rifampicin would not significantly influence saxagliptin. Thus, it is not necessary to adjust the dosage of saxagliptin when combining its use with rifampicin149. However, processed rhubarbs used as anti-diabetic could have some effects on CYP450 enzymes, modifying saxagliptin metabolism. As a result, the dose of saxagliptin should be adjusted when combined with rhubarbs150. One of saxagliptin's metabolites is active, and it is worthwhile researching how this active metabolite could be used.

3.2.3. Linagliptin

Whether Linagliptin is administered orally or intravenously, the dominant excretion pathway is through feces (84.7% and 58.2%, respectively), and renal excretion accounts for 5.4% and 30.8%, respectively. Most of the drug remains unchanged, while its metabolite S-3-hydroxypiperidinyl, which is formed through a two-step mechanism, accounts for more than 10% of the total drug. The formation of this metabolite is mediated by CYP3A4, aldo-keto reductases, and some carbonyl reductases151. After about 90 min of administration, the drug reaches its Cmax and after 4 days the concentration is steady. Linagliptin is unique, for it does not have a linear dose-proportional AUC and Cmax, which could be explained by its two-compartmental model, which could have a higher affinity to the target152. When combining linagliptin with fimasartan, which is used for treating hypertension and heart failure, there is no significant change in the pharmacokinetic profile, so these two drugs could be used together153. It has also been suggested that linagliptin could be used together with digoxin, which indicates that linagliptin has no interactions with P-glycoprotein154. Although linagliptin has potential to inhibit OCT1 and OCT2, its low therapeutic concentration in plasma would hardly result in transporter-mediated drug–drug interactions155. Hepatic first pass metabolism results in its low bioavailability156; combination with some nanoparticles such as solid lipid nanoparticles might increase its bioavailability157.

3.2.4. Alogliptin

Alogliptin has high bioavailability (almost 100%) and is primarily eliminated in urine (more than 60%) as the parent drug. CYP2D6 participates in alogliptin metabolism. The primary metabolite is an N-demethylation metabolite, which is active; the product then gets acetylated to produce an inactive metabolite. In plasma and urine, the two metabolites make up less than 2% and 6%, respectively. The renal clearance rate is within the range of 8.6–13.6 L/h158, and Tmax reaches its peak at 1–2 h after administration. The small intestine is the place where absorption primarily occurs. Food intake was reported not to have much influence on AUC; only Cmax was slightly influenced, but this effect was not clinically significant. In patients with T2DM, the half-life of alogliptin is 12.5–21.1 h; at an administration dose of 25 mg, the maximum recommended dose, its half-life is about 21 h159. In addition, animal experiments also support a once-daily dosing regimen160. To avoid drug–drug interactions, some studies on the combined use with other drugs have been conducted. Combination of alogliptin with metformin or cimetidine does not affect its pharmacokinetics161. Alogliptin absorption is affected by some transporters sensitive to fruit juice in the intestine, which results in inhibition of intestinal adsorption of the drug162. The high bioavailability of alogliptin could inspire drug design to elevate the bioavailability of drugs, for example by avoiding or reducing hepatic first pass metabolism.

3.2.5. Vildagliptin

14C labeling of vildagliptin was used to determine its absorption, metabolism, and elimination in humans. The bioavailability of vildagliptin is 85%163. The primary components in plasma are the parent drug and a carboxylic acid derivate, which account for 25.7% and 55%, respectively. Of excreted vildagliptin, 85.4% could be obtained in urine, where the parent drug accounted for 22.6%, while the remainder was obtained in feces, where the parent drug accounted for 4.54%. There are four pathways in vildagliptin metabolism, the most important of which results from cyano group hydrolysis, which is not associated with CYP450 enzymes164. In patients with T2DM, vildagliptin could be absorbed rapidly, and the elimination half-life is 1.32–2.43 h165. Within the range of 25–200 mg, the half-life showed an increase in a dose-dependent manner from 1.6 to 2.5 h166. To improve its low half-life, a controlled-release dosage form was prepared, containing Guar gum, to maintain drug release for up to 24 h167. Contrary to the DPP-4 inhibitors metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, CYP enzymes show limited roles in vildagliptin metabolism, for it is usually metabolized through oxidative processed168. Thus, this drug usually does not interact with other drugs commonly metabolized by CYP enzyme systems. This inspires the design of other drugs that could be metabolized through other enzymes rather than CYP450 enzymes.

3.2.6. Gemigliptin

For gemigliptin, 90.5% could be recovered over 192 h (63.4% from urine and 27.1% from feces). A total of 23 metabolites were observed in plasma, where the parent drug is the most abundant component, accounting for 44.8%–67.2% in urine and 27.7%–51.8% in feces. The major metabolic pathway is hydroxylation, and the major metabolites are dehydrated and hydroxylated metabolites169. After receiving 50 mg gemigliptin, the drug is absorbed quickly and its bioavailability could reach about 95.2%170, reaching its Cmax at approximately 1.8 h. The AUC increased proportionally with increasing dosage and the terminal half-life was 17.1 h. It was also reported that it did not accumulate, and it could be combined with food171. In patients with renal impairment, Cmax and AUC were increased by 20%–50%, depending on their degree of renal disease. However, it is suggested that the dosage of gemigliptin does not need to be adjusted in renal impairment patients172. When combining the drug with ketoconazole or rifampicin, the pharmacokinetics changed significantly, suggesting that the dosage should change when combining it with drugs that interact with CYP3A4173. When combining the drug with glimepiride, its pharmacokinetic properties were not altered and there was no need to change the dosage174. Considering gemigliptin is metabolized via CYP450 enzymes, future studies are needed to modify the drug in order to prevent drug interactions when it is combined with other drugs that are metabolized by CYP450 enzymes.

3.2.7. Teneligliptin

More than 90% of teneligliptin is excreted within 216 h after administration, where 45.4% is excreted in urine and 46.5% in feces. The primary components are the parent drug and its thiazolidine-1-oxide derivative, which account for 14.85% and 17.7%, respectively. In human, the most important enzymes that participate in teneligliptin metabolism are CYP3A4 and FMO3175. After oral administration of different doses of teneligliptin ranging from 2.5 to 160 mg, Cmax and AUC increase in a dose-dependent manner. The half-life of teneligliptin is 24.2 h. Teneligliptin might be a suitable drug for patients with hepatic and renal impairment, as it has many elimination pathways; around 65.6% is metabolized and 34.4% is excreted176. Furthermore, renal impairment does not influence Cmax, and dialysis does not affect the safety of teneligliptin177. When teneligliptin and canagliflozin are combined, there is no strong pharmacokinetic interaction, so these drugs could be administered together for T2DM treatment178. Other research focused on its interactions with SLGT2 inhibitors; a pharmacokinetic study revealed that current SLGT2 inhibitors have minor interactions with teneligliptin179. Teneligliptin has a quite long half-life, which results from its unique “J-shaped” structure and strong hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds with specific domains of targets176. Some new drugs could mimic the effects of teneligliptin to prolong their half-lives.

3.2.8. Omarigliptin

The bioavailability of omarigliptin is almost 100%180, and it is absorbed very quickly. As regards excretion, around 74.4% of the drug was observed in urine while 3.4% was observed in feces. In urine, the major form is the parent drug, indicating that renal excretion is the main excretion method. No significant metabolites could be detected in plasma181. At different dosages, Tmax ranged from 0.75 to 4.0 h. Within the range of 0.5–400 mg, Cmax and AUC change in a dose-dependent manner within two days, and the urinary excretion rate is 1.6–2.7 L/h. The Tmax value under fasted conditions is 1.5 h, while under fed conditions it is 4 h182. For patients with renal impairment, due to pharmacokinetic reasons, the dose should be halved183. The risk of drug interactions for omarigliptin is relatively low, because it does not inhibit CYP450 enzymes and some essential drug transporters. In addition, it does not have an induction reaction to some critical CYP450 enzymes184. Food intake could influence omarigliptin metabolism; how this could be avoided requires more research.

3.2.9. Other drug candidates in clinical trials

Ex vivo studies show strong inhibitory effects of HSK-7653 on DPP-4 compared with omarigliptin. After HSK-7653 treatment at 10 mg/kg, >80% inhibition of plasma DPP-4 could be maintained for at least 12 days. This compound also showed limited stimulatory and inhibitory effects on human CYPs, resulting in less potential for drug–drug interactions. A clinical study in humans proved that after treatment with 25 mg HSK-7653, >80% inhibition of DDP-4 could be maintained for more than 14 days, indicating that this drug candidate is a very long-acting drug for T2DM treatment93. DBPR108 is absorbed rapidly and reaches its Cmax at 108 ng/mL in Sprague–Dawley rats. After oral administration, its Tmax is 1.8 h while its half-life is 3.8 h. The AUC of DBPR108 was about 410 ng/(mL·h) at a dose of 5 mg/kg185. TQ-F3083 is a drug candidate with an excretion recovery of 7.84% in urine and 5.76% in feces. In human, it is mostly metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, where CYP3A is the principal metabolic enzyme. However, the parent drug remains the main substance in plasma, urine, feces, and bile samples. TQ-F3083 cannot induce CYP450 enzymes; however, it shows weak inhibitory effects on CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. The drug is widely distributed in tissues and the concentration in most tissues is higher than in plasma95. DPP-4 inhibitors generally have good bioavailability and are metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, providing both opportunities and challenges for clinical use. We hope based on the structures and pharmaceutical profiles of approved drugs that compounds with better efficacy and physiological disposition be developed.

4. Comparing GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors

Many GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors have already been approved for T2DM treatment; they are widely used, and they have been shown to be effective in patients. In addition, many drug candidates have entered clinical trials186. Thus, metabolism and excretion studies of these drugs are of high significance.

GLP-1 RAs are generally polypeptides with modifications of some amino acids (Fig. 1187, 188, 189, 190, 191). Since most GLP-1 RAs mimic endogenous polypeptides, they are mainly metabolized through degradation into small polypeptides and amino acids by some enzymes, in contrast to chemical drugs. Some drugs are modified with chemical structures; these parts are usually metabolized by oxidation, while the polypeptide parts are metabolized by degradation. CYP450 enzymes play limited roles in metabolism of these drugs, which are generally not their substrates192. Drug design and modification studies generally aim at reducing the interactions between GLP-1 RAs and drugs metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, facilitating the simultaneous treatment of T2DM and other symptoms. In addition, since they mimic endogenous polypeptides with limited alterations or modifications, their degradation is inevitable by natural enzymes, such as DPP-4, which can severely influence the pharmacokinetic characteristics. Currently, some GLP-1 RAs with low molecular weight are being developed, avoiding their enzymatic degradation54,193. However, how these drugs are metabolized and their interactions remain to be elucidated. In addition, some new formulations could be developed to combine treatments. These drugs generally have the potential to cause delayed gastric emptying194,195, possibly altering the absorption rates of orally administered drugs. In addition, the stomachs of some patients are affected by old age and/or disease. Thus, additional studies are needed. Most metabolites could be found in urine and some other components in feces, air, and plasma, meaning that the kidney is one of the key organs that participate in the excretion of these drugs. Patients with renal failure potentially have difficulties in metabolizing these drugs, altering the pharmacokinetic profile110. Since most drugs can result in delayed gastric emptying, whether these drugs could be combined with drugs accelerating gastric emptying to avoid this adverse effect remains to be determined196, and currently no studies or clinical trials have been reported to solve this adverse effect. If this could be solved, some major drug interactions could be handled, providing new possibilities for T2DM treatment. Since T2DM might be related to a lack of renal function, the development of new treatment methods to improve renal excretion is of great significance. In drug design, much attention must be paid (i) to appropriate backbones of peptide-mimicking drugs, (ii) to potential functions, and (iii) by which enzymes new drugs are degraded. To optimize the pharmacokinetic profile, some modifications could be made to the peptide chain, such as adding functional groups or introducing disulfide bonds. In addition, some of the sequences could be altered to optimize the pharmacokinetics, for example by introducing synthetic amino acids. In addition, the pharmacokinetic profile, including the drug's half-life, should also be carefully considered. Another critical consideration is how these drugs could be applied in patients in different conditions. The metabolism and excretion processes should be considered to avoid organ damage, especially to the stomach and kidneys.

Figure 1.

Important characteristics affecting the physiological disposition of GLP-1 RAs. Important factors affecting the physiological disposition of drugs include their metabolism, drug interactions, and excretion187, 188, 189, 190, 191.

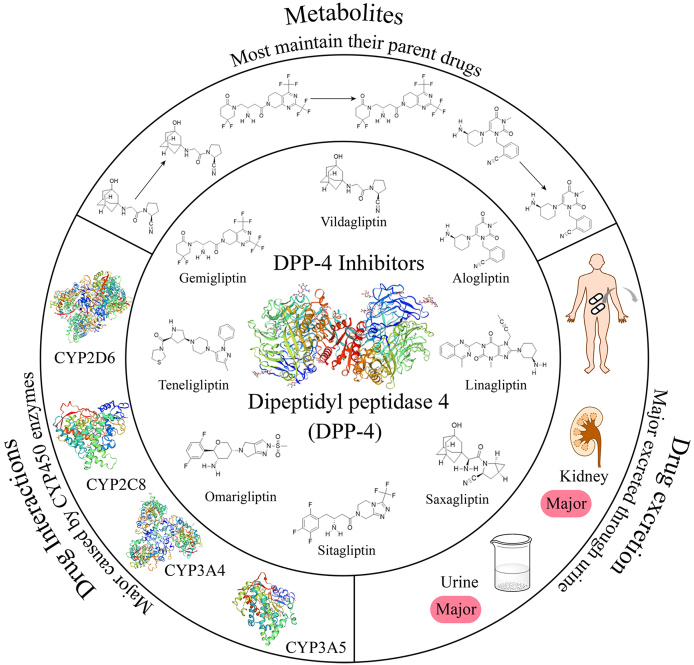

DPP-4 inhibitors are mostly small molecules with good bioavailability, providing a promising opportunity for clinical use. As regards metabolism and excretion of DDP-4 inhibitors (Fig. 2), most drugs are metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, where CYP3A4 plays a major role, and the metabolites could be detected in excreta197. The half-lives of the drugs are generally <24 h, while a minority have half-lives of >3 days. Some drugs are mainly metabolized by cyano group hydrolysis enzymes and FMO3 rather than CYP450 enzymes175. Since most drugs are substrates of CYP450 enzymes, combined use of some drugs metabolized by CYP450 enzymes or even some grapefruit enzymes might significantly change pharmacokinetics141,179. In general, combinations of drugs that do not induce or inhibit CYP450 enzymes are safer. In addition, some drug interaction studies focusing on efficiency and safety should be conducted before combined use should be approved. Some reports emphasized that daily intake of food, fruit, or traditional medicine could also influence metabolism and pharmacokinetics of some DPP-4 inhibitors. Patients need to seek advice from doctors on whether certain foods are appropriate141. As regards excretion of the metabolites, most compounds are found in the form of the parent drug in urine. The other main excretion pathways are elimination through feces, but fecal metabolite levels are generally not as higher as the levels in urine. Thus, whether patients with renal impairment need dose adjustment should be studied148. Some studies are expected to show the detailed mechanisms of renal excretion of these metabolites. Based on patients' clinical requirements, physicians may prescribe drugs with different chemical structures and dosage forms, which have different half-lives (i.e., short-term and long-term) for treating different conditions. Some methods in drug delivery employing macromolecules such as polymeric liposomes, polymeric micelles, and highly branched polymers have already been developed198. Using these macromolecules, drugs could be released in a sustained manner, extending their half-lives to increase efficacy199. Thus, in designing new drugs, some derivates of approved compounds could be used, where some functional groups could be altered or coupled with some macromolecules to optimize their pharmacokinetics.

Figure 2.

Important characteristics affecting the physiological disposition of DPP-4 inhibitors. The chemical structure of DPP-4 inhibitors and factors including their metabolism, drug interactions, and excretion affect their physiological disposition.

Comparing GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors (Table 4, Table 5), both have been approved by drug administration authorities and proved effective in T2DM treatment. GLP-1 RAs are generally peptide drugs administered through injection, while DPP-4 inhibitors are generally chemical compounds administered orally or through injection. With respect to their metabolism, CYP450 enzymes participate in metabolizing the majority of DPP-4 inhibitors, while GLP-1 RAs are often metabolized through peptide degradation. Comparing these two drug classes, the half-lives of DPP-4 inhibitors are generally shorter, which might result from their exogenous nature and their metabolism through different pathways compared with GLP-1 RAs. As regards drug interactions, these drugs are totally different. GLP-1 RAs in general cause delayed gastric emptying, which might be related to the late absorption of some orally administered drugs. GLP-1 RAs had limited reactions with CYP450 enzymes. Some DPP-4 inhibitors are substrates of CYP450 enzymes, so the metabolism of the drugs, which combine with DPP-4 inhibitors to treat T2DM, by CYP450 enzymes may also result in drug interactions. Based on the health status of the liver, stomach, or kidney of patients, the two kinds of drugs could be applied differently. For patients with gastric diseases, attention should be paid when using GLP-1 RAs, while for patients with liver diseases, attention should be paid when using DPP-4 inhibitors. CYP enzymes and delayed gastric emptying could also cause drug interactions. Co-administration of drugs to treat T2DM symptoms should be researched before approval for clinical use in patients. Despite quite different chemical structures, the majority of these drugs are excreted through urine. Thus, it is critical to investigate whether drugs of these kinds can be used in patients with renal impairment. In drug development, some functional groups could be added or altered to improve pharmacokinetics. In the field of peptides, the sequence could additionally be altered to avoid fast enzymatic degradation.

Table 4.

Metabolism, elimination and drug interactions of GLP-1 receptor agonists currently on market.

| Number | Name | Metabolism | Elimination | Drug interaction | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exenatide | Concentration in plasma: increased in a dose dependent manner; Mean half-life: 3.3–4 h; Tmax: 2.2 h |

Mainly degraded at kidney; Completed degraded into peptides |

Delayed gastric emptying; No significant effect with acetaminophen |

96, 97, 98, 99, 100 |

| 2 | Liraglutide | Mean half-life: 13.5 h; Exposure increased in a dose dependent manner |

Cleaved by DPP-4 in the Ala 8–Glu 9 position of the N-terminus; Product could be further degraded by NEP into several metabolites; Rate of clearance is about 0.9–1.4 L/h; Liraglutide degraded completely in body |

Liraglutide has small potential in reacting with CYP450; Influence gastric emptying; No pharmacokinetic interaction with insulin detemir |

101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106 |

| 3 | Albiglutide | Metabolic process: urine ubiquitous proteolytic enzymes in vascular endothelium; Half-life: five days; Body clearance: 67 mL/h; Maintain in a steady state after 4–5 days |

Degrade into small peptides and some single amino acids; Could not be cleared in the glomeruli in normal state |

Safe in coadministration with digoxin or warfarin; Have great influence on pharmacokinetics on simvastatin |

107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112 |

| 4 | Dulaglutide |

Cmax: 24–72 h; Steady plasma concentration could maintain 2–4 weeks; Elimination half-life: around 5 days |

Dulaglutide's excretion like general protein catabolism pathways; Degrade into small polypeptides; Not be eliminated through glomerular filtration or CYP450 enzymes |

Delayed gastric emptying; No important pharmacokinetic interaction with digoxin, warfarin and atorvastatin |

113, 114, 115, 116 |

| 5 | Lixisenatide | Half-life: 2.7–4.3 h; AUC and Cmax increased in a dose dependent manner |

Excreted like endogenous peptides; CYP450 enzymes do not participate in metabolizing; All the metabolites could be detected are polypeptides degraded from lixisenatide; Main metabolites do not show any biological activities |

Delayed gastric emptying; No need of adjusting dose with ethinylestradiol, levonorgestrel and atorvastatin |

44, 117, 118, 119, 120 |

| 6 | Semaglutide | A total of six metabolites were identified in human plasma; Proteolytic cleavage in the peptide backbone area and beta-oxidation of the fatty acid side chain; For oral given doses, median Tmax is 1.5 h, half-life is 1 week for the injection dose, Cmax within the range of 24–56 h. |

Metabolized prior to excretion slowly primarily in urine; 53% of the drug could be recovered in urine |

Delayed gastric emptying; Potential increasing AUC of metformin; Not increasing the half-life of lisinopril and warfarin. |

121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128 |

| 7 | Tirzepatide | Catabolism of the peptide backbone and β-oxidation of the di-acid chain; Main metabolites in circulation: parent drug, accounting to higher than 80%; Cmax: is considered to be dose-proportional within the range of 26–874 ng/mL; Tmax: 1–2 days after administration; Half-life: 116.7 h. |

Mainly excreted through urine and feces. | Delayed gastric emptying. | 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136 |

Table 5.

Metabolism, elimination and drug interactions of current DPP-4 inhibitors currently on market.

| Number | Name | Metabolism | Elimination | Drug interaction | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sitagliptin | Half-life: 8–14 h; Tmax: 1–6 h; Enzymes: major CYP3A4, CYP2C8 made minor contribution |

Majority of drug excreted through kidney; Clearance: 388 mL/min; 87% of drugs recovered in urine |

Grapefruit interact with sitagliptin; No significant change in pharmacokinetic with lobeglitazone; No significant change in pharmacokinetic with tinospora cordifolia aqueous extract |

137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144 |

| 2 | Saxagliptin | Half-life: 6.7 Active metabolite: 5-hydroxy saxagliptin; AUC: correlated with renal impairmen CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 played an important role in forming metabolites |

74.9% in urine and 22.1% in feces; 24.0% saxagliptin and 44.1% 5-hydroxy saxagliptin; Mainly through renal and hepatic routes |

Rifampicin would not significantly influence saxagliptin; Processed rhubarbs affect CYP450 enzymes, influencing saxagliptin |

145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150 |

| 3 | Linagliptin |

Cmax: 4 day Main metabolites: S-3-hydroxypiperidinly derivate; Enzymes: CYP3A4, aldo-keto reductases and some carbonyl reductases; Not have a linear dose-proportional AUC and Cmax |

Excretion mainly through fecal; Most of the drugs maintained in its unchanged form |

No significant pharmacokinetic change with fimasartan; Could be used together with digoxin; Inhibit OCT1 and OCT2 transporters |

151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157 |

| 4 | Alogliptin | Active metabolite: N-demethylation metabolite; Tmax: 1–2 h; Half-life: 12.5–21.1 h |

Primarily eliminated in urine in the form of parent drug; Renal clearance: 8.6–13.6 L/h |

Grapefruit interact with alogliptin; No significant change in pharmacokinetic with metformin or cimetidine |

158, 159, 160, 161, 162 |

| 5 | Vildagliptin | Major component in plasma: parent drug and a carboxylic acid derivate; Metabolic process: major through cyano group hydrolysis; Half-life: 1.32–2.43 h |

Major excrete through urine; 22.6% maintained in the form of parent drug |

limited interactions with CYP enzymes | 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168 |

| 6 | Gemigliptin | A total of 23 metabolites were observed in plasma; Major metabolite: hydroxylated metabolite; Cmax: 1.8 h; AUC increased proportionally with increasing of dosage; Terminal half-life: 17.1 h; dominantly metabolized by CYP3A4 |

90.5% recovered over 192 h major in urine; The parent drug is the most abundant component |

Ketoconazole or rifampicin significantly change pharmacokinetics; Interactions with CYP3A4; No significant change in pharmacokinetics with glimepiride |

169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174 |

| 7 | Teneligliptin | Major component: parent drug and thiazolidine-1-oxide derivative; Important enzymes: CYP3A4 and FMO3; Cmax and AUC increased in a dose dependent manner; elimination half-life: 24.2 h |

Larger than 90% of teneligliptin could be excreted in 216 h; Excrete major in urine and feces; 65.6% goes through metabolism and 34.4% goes through excretion |

No strong pharmacokinetics interactions with teneligliptin and canagliflozin; SLGT2 inhibitors have small interactions with teneligliptin |

175, 176, 177, 178, 179 |

| 8 | Omarigliptin |

Tmax value could range from 0.75 to 4.0 h; Cmax and AUC almost in a dose dependent manner |

74.4% of the drug in urine and 3.4% was observed in feces; Parent drug is the major component in urine; Renal excretion of the unchanged drug is the most important excretion method; Urinary excretion data is 1.6–2.7 L/h |

Limited interactions with CYP450 enzymes and some key drug transporters. | 180, 181, 182, 183, 184 |

5. Future perspectives

GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors are relatively new treatment methods for T2DM, from which many patients could benefit. To date, these drugs and drug candidates have not been comprehensively reviewed. In addition, some side effects of both GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors have been reported200, indicating that it is important to study their physiological disposition, especially when used in combination with other drugs. Here, we thoroughly reviewed the physiological disposition of drug candidates and approved drugs. Clinicians could use this review to prescribe different drugs to treat T2DM based on possible complications and the condition of the patient.

Although the physiological disposition of these drugs is satisfactory in most conditions, there is a strong need to improve it. GLP-1 RAs are unsuitable for people suffering from gastric diseases because GLP-1 has strong effects on the gastrointestinal tract and gastric distension, which can modulate GLP-1 through c-FOS201,202. DPP-4 inhibitors are not suitable for people suffering from liver diseases. DPP-4 inhibitors are mainly metabolized by CYP450 enzymes. Much research will be needed to discover appropriate chemical structures to solve the above problems.

There is a need to structurally modify GLP-1 RAs to mimic the function of GLP-1 while avoiding gastric discomfort. In the design process of DPP-4 inhibitors, drug interactions with CYP450 enzymes are a key consideration203, and these need to be optimized to improve their pharmacokinetic properties. In some patients with liver injury, CYP enzymes also showed changes204, which might influence drug metabolism. As a result, new structures suitable for the binding pocket of DPP-4 that are not metabolized by CYP450 enzymes could be specially designed for patients with liver injury. This structure could be further modified to design drugs with better compliance.

The mechanisms of incretin-based agents for T2DM treatment are associated with glucose metabolism; they generally do not cause hypoglycemia, and they do not affect body weight205. Since they are a newly developed drug type, many modifications could still be made to them. Although they could be chemically adapted to certain populations, such as patients with gastric and hepatic diseases, some unique characteristics could be achieved to avoid side effects. Additionally, some new targets should be identified for treating T2DM. In addition, some new candidates which affect other targets in this pathway could also be designed, such as some dual agonists that affect the pathway more comprehensively and achieve better treatment outcomes.

In the coming decades, incretin-based therapies for treating T2DM will be further developed. We hope new GLP-1 RAs will be designed with prolonged half-lives and improved efficacy. Some small-molecule GLP-1 RAs could be designed, improving their bioavailability and reducing patient discomfort such as delayed gastric emptying caused by peptide drugs. For DPP-4 inhibitors, based on the scaffolds that have already been published, some modifications could be made, eliminating drug–drug interactions. There are still many new drug candidates under development and in clinical trials, with the potential to improve treatment, physiological disposition, and patient compliance.

6. Conclusions

Herein, we review the physiological disposition of two kinds of incretin-based hypoglycemic agents, GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors, for treating T2DM, which can hopefully be further improved. The choice between GLP-1 RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors depends on the patient's conditions. In treating complications in T2DM, drugs must be selected that avoid interactions. For patients with different clinical requirements (such as a need for drugs with different half-lives), drugs with different chemical structures and dosage forms could be used. We also hope that based on the information and ideas provided, some drugs with novel structures with improved drug interactions that are suitable for renal failure patients will be developed soon. To our knowledge, this is the first review discussing the physiological disposition of incretin-based hypoglycemic agents. Future research will focus on drug interactions, the safe use of drugs in patients with renal impairment, and new formulations with improved pharmacokinetics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82003873 and 81903708), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (No. 2020M681899), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2021QNA7019).

Author contributions

Yaochen Xie: writing-original draft, writing-review & editing; Qian Zhou: writing-review & editing, resources; Qiaojun He: writing-review & editing; Xiaoyi Wang: conceptualization, supervision; Jincheng Wang: writing-review & editing, conceptualization, supervision, resources.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Xiaoyi Wang, Email: hzdysnk@163.com.

Jincheng Wang, Email: wangjincheng@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:S67–S74. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer M. Differential pathophysiological mechanisms in heart failure with a reduced or preserved ejection fraction in diabetes. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donate-Correa J., Luis-Rodríguez D., Martín-Núñez E., Tagua V.G., Hernández-Carballo C., Ferri C., et al. Inflammatory targets in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Med. 2020;9:458. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Netten J.J., Bus S.A., Apelqvist J., Lipsky B.A., Hinchliffe R.J., Game F., et al. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36:e3268. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill-Briggs F., Adler N.E., Berkowitz S.A., Chin M.H., Gary-Webb T.L., Navas-Acien A., et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:258–279. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lian F., Ni Q., Shen Y., Yang S., Piao C., Wang J., et al. International traditional Chinese medicine guideline for diagnostic and treatment principles of diabetes. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:2237–2250. doi: 10.21037/apm-19-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S.Q., Chen J.R., Liu M.L., Wang Y.P., Zhou X., Sun X. Effect and safety of acupuncture for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 randomised controlled trials. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;28:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s11655-021-3450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckstein M.L., Williams D., O'Neil L., Hayes J., Stephens J., Bracken R. Physical exercise and non-insulin glucose-lowering therapies in the management of Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical review. Diabet Med. 2019;36:349–358. doi: 10.1111/dme.13865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catic T., Jusufovic R. Use of food supplements in diabetes mellitus treatment in Bosnia and Herzegovina from the pharmacists perspective. Mater Sociomed. 2019;31:141. doi: 10.5455/msm.2019.31.141-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings D.E., Rubino F. Metabolic surgery for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in obese individuals. Diabetologia. 2018;61:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4513-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruni G., Ghione I., Berbenni V., Cardini A., Capsoni D., Girella A., et al. The physico-chemical properties of glipizide: new findings. Molecules. 2021;26:3142. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foretz M., Guigas B., Viollet B. Understanding the glucoregulatory mechanisms of metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:569–589. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltiel A.R., Olefsky J.M. Thiazolidinediones in the treatment of insulin resistance and type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1996;45:1661–1669. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.12.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain U., Das A.K., Ghosh S., Sil P.C. An overview on the role of bioactive α-glucosidase inhibitors in ameliorating diabetic complications. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;145 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann J.L., Maikawa C.L., Smith A.A., Grosskopf A.K., Baker S.W., Roth G.A., et al. An ultrafast insulin formulation enabled by high-throughput screening of engineered polymeric excipients. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen G., Meiffren G., Famulla S., Heise T., Ranson A., Seroussi C., et al. ADO09, a co-formulation of the amylin analogue pramlintide and the insulin analogue A21G, lowers postprandial blood glucose versus insulin lispro in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:961–970. doi: 10.1111/dom.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chia C.W., Egan J.M. Incretins in obesity and diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1461:104–126. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendicho-Lavilla C., Seoane-Viaño I., Otero-Espinar F.J., Luzardo-Álvarez A. Fighting type 2 diabetes: formulation strategies for peptide-based therapeutics. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;12:621–636. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norris J.M., Johnson R.K., Stene L.C. Type 1 diabetes—early life origins and changing epidemiology. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:226–238. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30412-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galicia-Garcia U., Benito-Vicente A., Jebari S., Larrea-Sebal A., Siddiqi H., Uribe K.B., et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6275. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eizirik D.L., Pasquali L., Cnop M. Pancreatic β-cells in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: different pathways to failure. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:349–362. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu G., Liu B., Sun Y., Du Y., Snetselaar L.G., Hu F.B., et al. Prevalence of diagnosed type 1 and type 2 diabetes among US adults in 2016 and 2017: population based study. BMJ. 2018;362:k1497. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nauck M.A., Meier J.J. Incretin hormones: their role in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:5–21. doi: 10.1111/dom.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nangaku M., Wanner C. Not only incretins for diabetic kidney disease—beneficial effects by DPP-4 inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2021;99:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elumalai S., Karunakaran U., Moon J.S., Won K.C. High glucose-induced PRDX3 acetylation contributes to glucotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells: prevention by teneligliptin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;160:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowley M.J., McGuire D.K., Alexopoulos A.S., Jensen T.J., Rasmussen S., Saevereid H.A., et al. Effects of liraglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients with and without baseline metformin use: post hoc analyses of the LEADER trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e108–e110. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae C.S., Song J. The role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) in type 3 diabetes: GLP-1 controls insulin resistance, neuroinflammation and neurogenesis in the brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2493. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaribeygi H., Rashidy-Pour A., Atkin S.L., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. GLP-1 mimetics and cognition. Life Sci. 2020;264 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., Zhang J., Cao X., Guan Y., Shen S., Zhong G., et al. Mitochondrial protein IF1 is a potential regulator of glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) secretion function of the mouse intestine. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:1568–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner U., Haschke G., Herling A.W., Kramer W. Pharmacological profile of lixisenatide: a new GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2010;164:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang J., Feng J.N., Ling W., Jin T. The anti-inflammatory feature of glucagon-like peptide-1 and its based diabetes drugs—therapeutic potential exploration in lung injury. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:4040–4055. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giannoukakis N. Exenatide. Amylin/Eli Lilly. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen L.L., Young A.A., Parkes D.G. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4): a potential therapeutic for improved glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2004;117:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iepsen E.W., Torekov S.S., Holst J.J. Liraglutide for type 2 diabetes and obesity: a 2015 update. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:753–767. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1054810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnett A. Exenatide. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2593–2608. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.15.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cvetković R.S., Plosker G.L. Exenatide. Drugs. 2007;67:935–954. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson S.H., Martin T.S., Jones J.D., Seal D., Emanuel F. Liraglutide (victoza): the first once-daily incretin mimetic injection for type-2 diabetes. P T. 2010;35:498–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Home P.D., Ahrén B., Reusch J.E., Rendell M., Weissman P.N., Cirkel D.T., et al. Three-year data from 5 HARMONY phase 3 clinical trials of albiglutide in type 2 diabetes mellitus: long-term efficacy with or without rescue therapy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rendell M.S. Albiglutide: a unique GLP-1 receptor agonist. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:1557–1569. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2016.1240780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmins P. Industry update. Ther Deliv. 2015;6:9–15. doi: 10.4155/TDE.15.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanford M. Dulaglutide: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:2097–2103. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheen A.J. Dulaglutide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:485–496. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1296131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratner R., Rosenstock J., Boka G., Investigators D.S. Dose-dependent effects of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1024–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen M., Knop F.K., Holst J.J., Vilsboll T. Lixisenatide, a novel GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. IDrugs. 2009;12:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhillon S. Semaglutide: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:275–284. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau J., Bloch P., Schäffer L., Pettersson I., Spetzler J., Kofoed J., et al. Discovery of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue semaglutide. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7370–7380. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christou G.A., Katsiki N., Blundell J., Fruhbeck G., Kiortsis D.N. Semaglutide as a promising antiobesity drug. Obes Rev. 2019;20:805–815. doi: 10.1111/obr.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smits M.M., Van Raalte D. Safety of semaglutide. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:496. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.645563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]