Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a significant mental and emotional toll on critical care nurses. High patient acuity, staffing shortages, and increased care needs both in the hospital and in the community are contributing to increases in depression, anxiety, and overall burnout. Nurses who perceive, internalize, anticipate, and experience stigma may be hesitant to engage in mental health care and self-stewardship. Resultingly, stigma is a detriment to the mental health and overall well-being of critical care nurses. The American Nurses Association recognizes this stigma and is committed to dismantling stigma as a barrier to mental health care. Nurses may fear social and professional consequences associated with receiving mental health care. Nursing leaders and organizations can take steps to reduce stigma related to mental health care and support self-stewardship among critical care nurses.

Keywords: Nursing, stigma, mental health, self-care, self-stewardship

Critical care nurses have borne a significant burden during the pandemic. Studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously degraded critical care nurses’ physical, psychological, and emotional wellbeing1-3. The mental health consequences of the pandemic on nurses include increased rates of depression4,5 anxiety4,5, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)4-6, and burnout4,6. Suicide rates among nurses have long been higher than the general population7,8, and high stress clinical scenarios like disease outbreaks are well recognized risk factors for nurse suicide8. Unsurprisingly, 41.8% of nurses report that they have witnessed or experienced an “extremely stressful, disturbing, or traumatic event” related to the COVID-19 pandemic8. This is especially true of younger members of the profession, with 51% of nurses under the age of 25 reporting depression within the past 14 days8. If we are to maintain a healthy and robust workforce to support patients through this and future periods of increased care needs, we must protect the emotional and psychological of health of those called to care.

Stigma is a significant barrier to nurses seeking mental health and other support services9. The American Nurses Foundation found that more than 36% of nurses report stigma related to mental health care seeking10. Stigma is defined as an undesirable attribute that has negative identity consequences as well as impediments to social standing11. Within the nursing profession, stigma related to mental health care seeking may create barriers to peer acceptance and occupational success and may delay or prevent care seeking all together. Mental health stigma is well documented and stems in part from stereotypes that people with mental illness are irrational, incompetent and undependable12. These negative stereotypes are in direct conflict with professional and occupational norms. As the most trusted profession, nurses are sometimes seen as morally infallible; this assumption is incongruent with negative stereotypes about who succumbs to depression and anxiety. Stigma has rooted itself in the norms and practices of the nursing profession, stemming from a culture of healthcare where nurses are seen as caregivers rather than those in need of care themselves. This creates an identity discordance between the nurse the caregiver, and the nurse who requires care and support.

Case Illustration

Tasha is an experienced critical care nurse. During the long haul of the pandemic, she often worked more than her assigned hours because of staff shortages. Mid-way through the third surge she started to notice that she was chronically exhausted and had little energy for activities outside of work. She had developed poor sleep habits that resulted in her getting less than 6 hours of sleep/day. When she did sleep, it was often disrupted with nightmares involving patients she had cared for. She felt guilty and sad about the patients she might have been able to help in other circumstances. When she was at work, the intensity of her patient load left her on sympathetic overload for the duration to her shift. She began to worry that she was depressed and could be experiencing PTSD. Tasha always prided herself as having a “thick skin”—she was regarded by her colleagues as a person who could handle anything. But now, she felt like she was drowning. Her healthcare organization regularly communicated the array of services that were available to support nurses like her, but she heard that the Employee Assistance Program wasn’t very responsive, and her supervisor was likely to find out that she was seeking help. Plus, if she had to admit she was seeking mental health support she would need to disclose it on her license renewal. She was concerned about what others would think if she admitted she was struggling. She had overheard other nurses making fun of those who sought counseling as “weaklings”. One of her close friends approached her manager about concerns about her own mental health needs and was told, “we are so short staffed I can’t afford to give you any time off-can’t you manage it on your day off?”. Besides, she wasn’t convinced anything would help anyway. She ought to be able to manage this herself.

The Background and Scope of Mental Health Stigma in Nursing

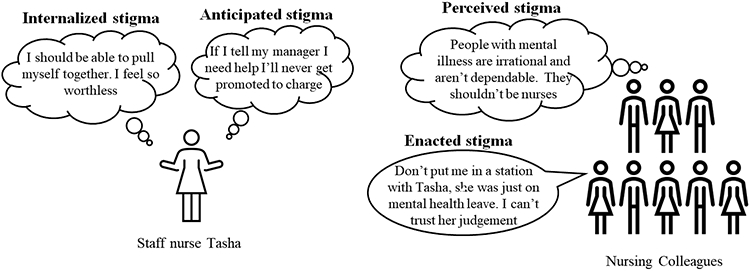

There are four classically defined domains that fall under the larger umbrella of stigma: internalized, perceived, anticipated, and experienced. All four have the potential to negatively impact the physical and emotional, but especially mental health of nurses. Perceived stigma involves general perceptions of mental illness and how the public at large feels about people who endorse mental health needs13. Prejudice is one example of perceived stigma13. Nurses who perceive stigma may begin to internalize these negative feelings and view themselves as somehow lacking or less than. Internalized stigma reduces self-esteem and self-concept and may reduce individual goals and aspirations13. Nurses may also anticipate negative reactions from others if their mental health status is known. Finally, enacted stigma is how people treat the stigmatized person. Enacted stigma includes gossip, insults, discrimination, and other behaviors13. Stigma in all its forms, makes it more difficult for people with mental health concerns to engage in professional mental-health care and self-care12. Please see figure 1 for a depiction of perceived, internalized, anticipated, and enacted stigma.

Figure.

Stigma Domains

Stress and diagnoses of depression and anxiety are extremely common in the general population. Over the course of a lifetime, 8.4% of US adults will experience a major depressive episode14 and 31.1% will endorse an anxiety disorder15. Pre-pandemic studies estimated that at any given time, approximately 10% of the workforce is actively battling depression16. Experts believe that this number has only increased due to the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic. These stressors are particularly acute for the nursing workforce as we respond to increased patient volumes, high acuity, staff shortages and increased caregiving responsibilities at home. Despite increasing literature about the negative impacts of mental health stigma on care seeking behaviors, media portrayals are rife with stereotypes about mental illness and violence, perceived danger to the community and associations with gun violence17. Community perceptions of mental illness also include unfounded stereotypes about incompetence, intellectual deficits, and amorality18. There is also a tendency to conflate normal mental health stressors with mental illness and thereby attach labels that contribute to stigma. Unfortunately, segments of the general community continue to believe that mental illness is controllable and therefore believe people suffering from mental illnesses are less entitled to compassion and support18. For example, there is a perception that depression and anxiety are “all in your head” and that people with mental illness should be able to “shake it off”. In contrast, we would never expect someone with pneumonia or heart failure to push through their illness because we recognize that the individual has no control over how the illness occurred or the time it takes to recover.

Anticipated stigma may be a major barrier to nurses reporting burnout, depression, and anxiety. Nurses who endorse higher mental health needs may fear negative repercussions from their coworkers and supervisors. They may fear gossip or anticipate a loss of their professional reputation as a capable and dependable team member, and they may expect to lose the camaraderie and support of colleagues as a result of disclosure. Others fear that their privacy will not be protected when they seek mental health services or share their struggles with others. From supervisors, nurses may fear loss of respect, loss of seniority and opportunities for professional growth like promotions. They may even fear loss of livelihood if nurses anticipate that their supervisor will pass them up for extra shifts or overtime related to depression or anxiety. These concerns are not without merit. Research shows that both coworkers and supervisors call into question the reliability of workers with mental illness16. The majority of state boards of nursing (30 of 50 states) ask questions about mental and psychiatric health during initial licensure and renewals19. These questions are variably compliant with regulations set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act19, and certainly give nurses pause about the professional costs of care seeking.

Provision 5 of the American Nurses Association Code of ethics states, “The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth20”. Nurses have the duty to care for themselves and each other as they do for their patients. The American Nurses Association (ANA) specifically addresses the damage done when nurses hold themselves and one another to a “hero” standard. The ANA affirms that we as nurses are not called to place the needs of the public above our needs as individuals. Beyond physical risk, the hero standard also undermines the mental health of the nurse. The hero standard perpetuates stereotypes about mental toughness among nurses and reinforces self-stigma when a nurse feels conflicted by the pull between self and patient. Provision 5 is the official statement that should rest the debate about the ethics of self-preservation in the face of undue stress and mental distress. Self-stewardship is not selfishness21. Asking for and receiving support is an act of integrity. It protects the nurse as an individual, protects today’s patients by ensuring that their caregiver has the emotional and mental capacity to deliver physical care with empathy, and protects tomorrow’s patients by promoting a healthy nursing workforce.

Nursing leaders, institutions and even individuals can take small steps towards reducing the stigma associated with mental health and occupational burnout. Even small actions like prioritizing uninterrupted staff breaks off of the nursing unit communicate to staff that their mental wellness is a priority and that patient care should not come at the expense of their mental and emotional health. Creating open and honest dialog about the prevalence of burnout and mental illness is a great way to combat occupational mental health stigma. Table 1 outlines specific steps nurses and their leaders can take to make visible their commitment to destigmatizing access and utilization of mental health services and creating healthy workplaces. If nurses know that they are not alone, and that they will not be penalized for self-stewardship related to mental health then they can be empowered to prioritize their mental wellness. In addition to institutional supports, the American Nurses Association is working to support the mental health and wellbeing of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing leaders can guide staff towards resources like mental health self-assessments, apps, toolkits, free meditation and relaxation exercises, and referrals to immediate help.

Table 1:

Strategies for creating an environment of mental wellness free from stigma

| Intervention/ practice change | Impact on stigma | Who can implement? |

|---|---|---|

| Use discretion with your language, refrain from using negative or non-clinical words like “crazy” when discussing mental health; make clear distinctions between mental health and mental illness | Reduces stereotypes and prejudices about mental illness | All levels: staff nurses, supervisors & senior leadership |

| Frame mental wellness as a part of wholistic wellness22 | Normalizes care seeking for mental illness | All levels but especially nursing leadership |

| Hold staff meetings and discuss occupational protections such as paid sick time for people utilizing mental health services | Reduce internalized stigma about self-stewardship | Nurse leaders |

| Schedule HR fairs to review institutional benefits related to mental health and wellness including confidentiality protections. | Increase knowledge about mental health supports | Nurse leaders |

| Work to foster a culture where break times off the unit are normal and encouraged for all staff. This may include advocating for additional staff to cover break times | Actively facilitate self-stewardship, position self-care as an imperative essential to the profession | Nurse leaders |

| Increase knowledge about self-stewardship and care seeking by sending monthly mental wellness emails or by creating a bulletin board in common areas | Educate staff about the high prevalence of stress and burnout – you are not alone | Nurse leaders |

| Advocate for access to comprehensive mental health services through insurance coverage and institutional resources | Reduce barriers to mental health care; demonstrate that mental health is an institutional priority | Organizations |

| Plan mental wellness days – offer hand or chair massages, have counselors available in private spaces throughout the hospital where nurses can “drop in” for a wellness assessment. | Position the institution as an organization that supports mental wellness through actions beyond words | Organizations |

| Encourage or consider requiring continuing education hours on burnout, stress, and mental illness in nursing. | Reduce stereotypes and prejudice, create awareness about the high prevalence of mental illness in health occupations. | Nurse Leaders/ Organizations |

Conclusions

The pandemic has exacerbated longstanding organizational and structural issues that have degraded the mental health and wellbeing of critical care nurses. Stigma is another barrier that stands in the way of optimal mental health among nurses. Fortunately, there are tangible steps that nursing leaders and organizations can take to promote mental health and reduce the stigma surrounding mental health and self-stewardship23. In challenging times, it is essential to communicate to nurses on the front lines that patient care does not come at the expense of our own mental health. Positioning self-stewardship as an essential nursing duty removes the stigma associated with mental health care. Committing to a path of self-stewardship encourages nurses to engage in healthy behaviors rather than hiding or pushing down feelings of stress, burnout, depression, or anxiety. Nurses must be empowered to care for their mental health for their own benefit and for that of our patients. When leaders and organizational structures support nurse’s individual commitment to their own wellbeing, healthy workplaces become reliable and effective resources for nurses. Together we can dismantle stigmatizing norms and instead develop practices and conditions for nurses to thrive and serve.

Financial Support:

Alanna Bergman is supported by the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing’s Discovery and Innovation Fund

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References.

- 1.American Nurses Foundation. Pulse of the nation’s nurses survey series: Mental health and wellness. Taking the pulse on emotional health, post-traumatic stress, resiliency. [Internet] Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aa484/globalassets/docs/ancc/magnet/mh3-written-report-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SC, Quiban C, Sloan C, Montejano A. 2020. Predictors of poor mental health among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Open. 2021;8(2):900–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, Badiale CS, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guixia L, Hui Z. A Study on burnout of nurses in the period of COVID-19. Psychol Behav Sci. 2020;9(3):31–6. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.789737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cenat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 295:1–16 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Scherer N, Felix L, Kuper H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16: e0246454 10.1371/journal.pone.0246454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choflet A, Barnes A, Zisook S, et al. The Nurse Leader’s Role in Nurse Substance Use, Mental Health, and Suicide in a Peripandemic World. Nurs Adm Q. 2022;46(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson BJE, Choflet A, Earley MM, et al. Nurse suicide prevention starts with crisis intervention make a plan to protect yourself and your colleagues. American Nurse Journal 16(2):14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston MJ, Nordberg A. Stigma: a barrier in supporting nurse well-being during the pandemic. Nurs Lead. 2022;20(2)174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Nurses Association More than 32k Nurses Share Experiences from the Front Lines. [(accessed on 22 July 2020)]; Available online: https://anamichigan.nursingnetwork.com/nursing-news/179188-more-than-32k-nurses-share-experience-from-the-front-lines [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):863–869. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Health Information: Major Depression. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.

- 15.National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Health Information: Any Anxiety Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/any-anxiety-disorder#:~:text=Prevalence%20of%20Any%20Anxiety%20Disorder%20Among%20Adults,-Based%20on%20diagnostic&text=An%20estimated%2031.1%25%20of%20U.S.,some%20time%20in%20their%20lives.

- 16.Dewa CS. Worker attitudes towards mental health problems and disclosure. IntJ Occup Environ Med. 2014; 5:175–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander L, Sheen J, Rinehart N, Hay M, Boyd L. The role of television in perceptions of dangerousness. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract 2018;13:187–196 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corrigan P. Mental health stigma as social attribution: Implications for research methods and attitude change. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract 2000; 7:48–67 10.1093/clipsy.7.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halter MJ, Rolin DG, Adamaszek M, Ladenheim MC, Hutchens BF. State nursing licensure questions about mental illness and compliance with the Americans with disabilities act. 2019; 57:17–22 DOI: 10.3928/02793695-20190405-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Nurses Association (2020). Provision 5: Self care & COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/~4a1fea/globalassets/covid19/provision-5_-self-care--covid19-final.pdf

- 21.Rushton CH. Conceptualizing moral resilience, In Moral Resilience: Transforming Moral Suffering in Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021. 10.17226/25982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rushton C & Boston-Leary K (In press) Nurses suffering in silence: Addressing the stigma of mental health in nursing and healthcare. Nursing management. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]