Abstract

Introduction:

Patients often fear axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) because of its associated complications; however, its effect on quality of life (QOL) is not well-described. We aimed to evaluate the effect of ALND on QOL over time and to identify predictors of worse QOL.

Methods:

Breast cancer patients undergoing ALND were enrolled in a prospective lymphedema screening study. Arm volumes were measured and QOL questionnaires completed at baseline, postoperatively, and 6-month intervals. The Upper Limb Lymphedema (ULL)-27 questionnaire was used to assess the effect of upper extremity symptoms on QOL in 3 domains (physical, psychological, and social). Predictors of QOL were identified by univariate and multivariable regression analyses.

Results:

From November 2016 through March 2020, 304 ALND patients were enrolled; 242 patients with at least 2 measurements and 6 months of follow-up were included. Median age was 48 years and median follow-up was 1.2 years. The 18-month lymphedema rate was 18%. Overall, QOL scores in all 3 domains decreased postoperatively and improved over time. On multivariable analysis, after adjusting for baseline scores, symptoms necessitating lymphedema therapy referral (p = 0.006) was associated with worse physical QOL. Younger age (p = 0.005) and lymphedema therapy referral (p = 0.006) were associated with worse psychological QOL. Arm volume was not correlated with QOL.

Conclusions:

QOL scores initially decreased after ALND improved by 6 months post-surgery. Decreases in QOL were independent of arm volume. Patients with worse QOL more often sought lymphedema therapy, although the effect of therapy on QOL remains unknown.

INTRODUCTION

Patients often fear the consequences and potential complications of axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).1 One well-known complication is lymphedema, but pain, paresthesias, and impaired shoulder mobility may also occur after ALND.2,3 These symptoms, although more prevalent and severe in the early postoperative period, can persist up to 5 years after surgery.4 Both lymphedema and arm-related symptoms may affect quality of life (QOL) after ALND.

Few studies have investigated the effect of ALND on QOL over time. The ALMANAC multi-center randomized trial compared QOL outcomes after ALND vs. sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and found higher rates of lymphedema and sensory loss, and worse QOL in the ALND group.5 A study of patients in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32 trial, a randomized trial of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) vs. ALND in pathologically node-negative patients, used the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) questionnaire to evaluate patients after ALND. Worse HRQOL was predicted by impaired range of motion and presence of neuropathy.6 However, these studies employed assessments of overall QOL (the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast + 4 [FACT-B+4]) and a non-specific scale evaluating global QOL (HRQOL), respectively, which could be affected by other types of treatment including chemotherapy or the breast cancer diagnosis itself. More studies are needed to better understand the effects of ALND on upper limb lymphedema-related QOL as well as the trajectory of symptoms and QOL over time. The purpose of this study was to evaluate QOL after ALND using a validated upper extremity QOL survey (Upper Limb Lymphedema 55-27) and to identify factors associated with worse QOL.

METHODS

Beginning in November 2016, female breast cancer patients 18 years of age and older who underwent breast surgery and ALND either in the primary setting or after SLNB were enrolled into a prospective lymphedema screening trial, which included baseline and longitudinal volumetric measurements and quality of life (QOL) questionnaires. Patients were excluded if they were having bilateral axillary surgery or had a prior history of axillary surgery, as these factors could interfere with the accuracy of volumetric arm measurements. Arm volume measurements were obtained using a Perometer (Perometer 350 NT®, Pero- System, Germany). ULL-27 survey and volumetric arm measurements were performed at baseline (prior to surgery), postoperatively (within 12 weeks of surgery), and at 6-month intervals for a period of 2 years. Baseline ULL-27 survey was administered prior to surgery, irrespective of whether the patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, with a median time from survey administration to surgery of 8 days.

Lymphedema was defined as a relative volume change (RVC) of ≥ 10%, calculated using the formula developed and validated by Taghian and colleagues7, RVC = [(A2U1)/(U2A1)]-1, where A1 and A2, and U1 and U2 are the arm volumes of the affected and unaffected arms at preoperative baseline and follow-up, respectively.

Patient-reported QOL was measured using the upper limb lymphedema (ULL)-27 survey, a lymphedema-specific validated QOL questionnaire assessing subjective arm swelling and QOL across 3 domains: physical, psychological, and social (eTable 1).8 This survey consists of 27 Likert items evaluating symptom presence over the past 4 weeks related to the affected extremity rated on a 5-point scale. A score of 100 on the ULL-27 signifies no impairment while a lower score reflects worse QOL. Patients were referred for lymphedema therapy if they had an RVC ≥ 10% or if they had symptoms of subjective arm swelling and requested referral. This study was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board; all patients gave written informed consent to participate. Prospective and retrospective data were entered into a HIPAA-compliant database.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical and demographic characteristics were described using median and range for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. A univariate linear regression analysis to evaluate the association between demographic and clinicopathologic covariates and QOL scores in each domain measured longitudinally over a period of 6 to 24 months was conducted using generalized estimating equations (GEE) via the gee functionality in R 3.6.3 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria). For the GEE model, normal distribution was assumed for the QOL scores and the identity link function was used. For multivariable linear regression analysis, variables that had a p-value of < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the GEE model as the explanatory variables, with QOL score as the outcome variable. Multiple comparisons corrections were implemented using the Bonferroni method (α*=0.0167). Patterns of change in QOL scores over the postoperative period were visualized using spaghetti plots and box plots constructed with the ggplot functionality in R 3.6.3. A Pearson correlation coefficient was estimated to assess the correlation between the 3 QOL domains in the ULL-27 questionnaire at each time point.

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Between November 2016 and March 2020, 304 patients with invasive breast cancer treated with unilateral ALND were enrolled; 242 patients with at least 2 longitudinal measurements and 6 months of follow-up were included in this study. Clinicopathologic characteristics of the patient cohort are shown in Table 1. Median patient age was 48 years and baseline BMI was 25.9 kg/m2. Twelve percent (n = 29) of patients self-identified as Asian, 19% (n = 47) as Black, 6% (n = 14) as Hispanic, and 60% (n=144) as White. The majority of patients had clinical T2/3 tumors (62%) and were clinically node-positive (74%) at presentation, with 64% presenting with cN1 disease. Most patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (71%, n = 172), while 70 patients had upfront surgery, with 84% (n = 59) receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The majority of patients (n = 184, 76%) had a mastectomy, of whom 59% had implant-based reconstruction, 12% had autologous reconstruction, and 29% had no reconstruction. At ALND, the median number of nodes removed was 18 (range 5–66) and the median number of positive nodes was 2 (range 0–61). Radiotherapy was administered to 94% of patients (n = 228), with 93% (n = 226) receiving nodal radiation. Patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy were more likely to receive nodal radiation compared to patients treated with upfront surgery (98% vs. 81%, p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of the Study Cohort (n = 242)

| Characteristic | Median (range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 48 (26–80) |

| Baseline BMI | 25.9 (18.1–46.5) |

| Dominant arm affected | 115 (48%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 29 (12%) |

| Black | 47 (19%) |

| Hispanic | 14 (6%) |

| White | 144 (60%) |

| Other/unknown | 8 (3%) |

| Clinical T stage | |

| 1 | 49 (20%) |

| 2 | 108 (45%) |

| 3 | 40 (17%) |

| 4 | 41 (17%) |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) |

| Clinical N stage | |

| 0 | 64 (26%) |

| 1 | 155 (64%) |

| 2 | 6 (3%) |

| 3 | 17 (7%) |

| Histology | |

| Ductal | 205 (85%) |

| Lobular or mixed | 32 (13%) |

| Other | 5 (2%) |

| Differentiation | |

| Well differentiated | 8 (3%) |

| Moderately differentiated | 100 (41%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 122 (50%) |

| Unknown | 12 (5%) |

| Subtype | |

| HR+/HER2– | 161 (67%) |

| HER2+ | 49 (20%) |

| HR–/HER2– | 32 (13%) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 115 (49%) |

| Unknown | 5 (2%) |

| Extracapsular extension | 89 (39%) |

| Unknown | 12 (5%) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Neoadjuvant | 172 (71%) |

| Adjuvant | 59 (24%) |

| None | 11 (5%) |

| Chemotherapy regimen* | |

| ACT** | 204 (88%) |

| TC | 14 (6%) |

| Other | 13 (6%) |

| Type of surgery | |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 58 (24%) |

| Mastectomy | 184 (76%) |

| Type of reconstruction in mastectomy patients*** | |

| No reconstruction | 54 (29%) |

| Flap | 21 (12%) |

| Tissue expander | 109 (59%) |

| Total number of lymph nodes removed | 18 (5–66) |

| Total number of positive lymph nodes | 2 (0–61) |

| Radiotherapy | 228 (94%) |

| Nodal radiotherapy | 226 (93%) |

| Referral to lymphedema therapy | 131 (54%) |

Includes only the 231 patients who received chemotherapy

Includes 16 patients who received carboplatin in addition to ACT

Includes only the 184 patients who had mastectomy

BMI body mass index, HR hormone receptor, ACT Adriamycin and cyclophosphamide, followed by taxol, TC taxol and cyclophosphamide

Lymphedema Incidence

At a median follow-up of 1.2 years, 42 patients developed lymphedema (RVC ≥ 10%). Twelve- and 18- month lymphedema rates were 10% (95% CI, 6–15%) and 18% (95% CI, 12–25%), respectively.

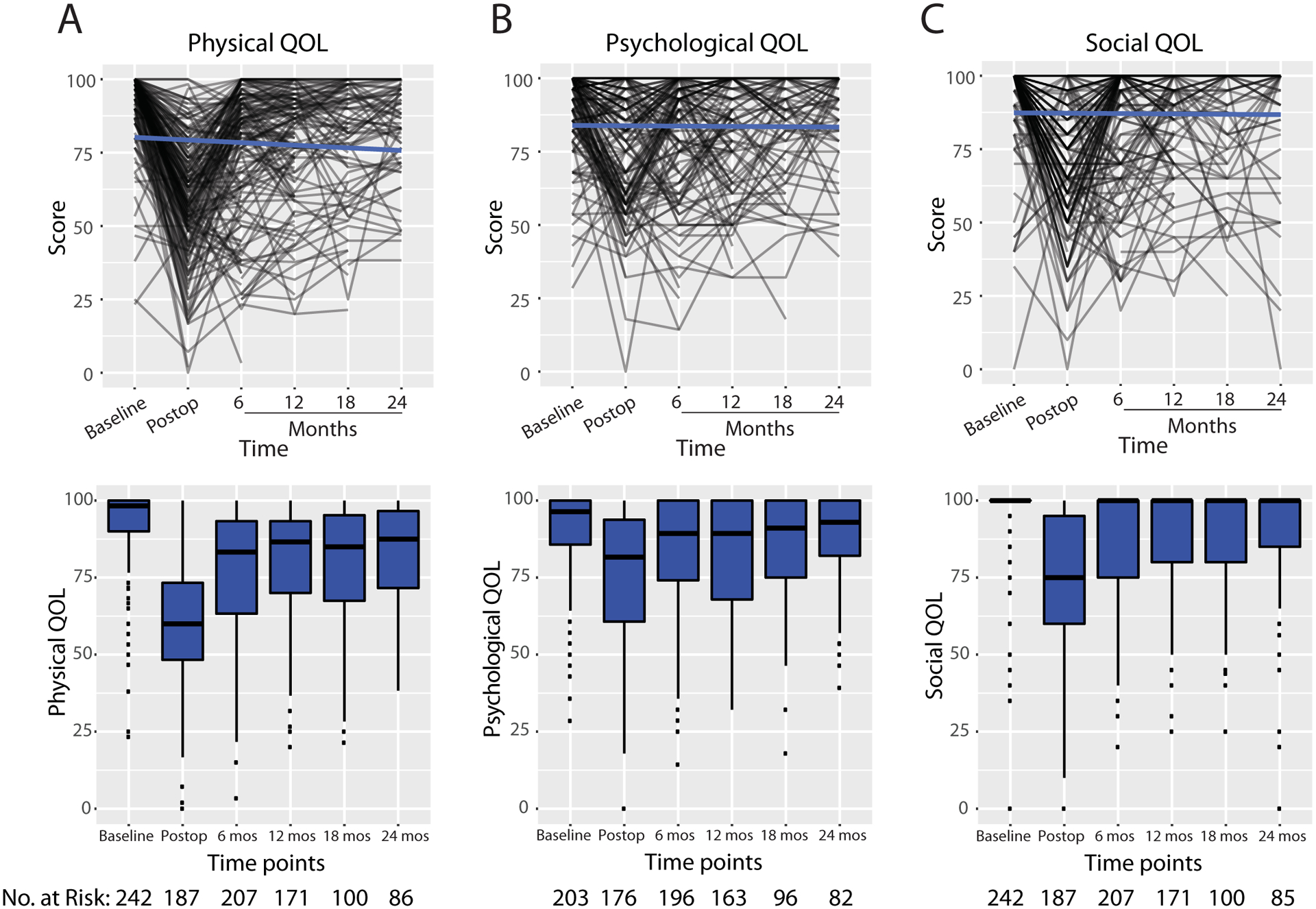

Trajectory of QOL Scores

QOL scores for the physical, psychological, and social domains decreased in the immediate postoperative period, followed by recovery to near baseline levels at approximately 6 months post-surgery. Individual scores and corresponding median scores for each timepoint are plotted in Fig. 1. While QOL scores for each domain varied among individual patients, the trend towards recovery after the immediate postoperative period was consistent. Correlations between the 3 ULL-27 domains were assessed at each time point. Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from 0.44 to 0.68, suggesting moderate correlation between the physical, psychological, and social domains (eTable 2).

Fig. 1. Quality of life as reported using the ULL-27 over time.

Spaghetti plots (top) and box plots (bottom) of for the A) physical domain B) psychological domain and C) social domain. Blue line indicates behavior of the linear model. Numbers in box plot are median scores. N represents sample size at each time point; note smaller sample sizes for psychological quality-of-life scores due to exclusion of surveys in which patients misinterpreted the survey.

QOL quality of life, mos months

Factors Associated with QOL After ALND

Physical Domain

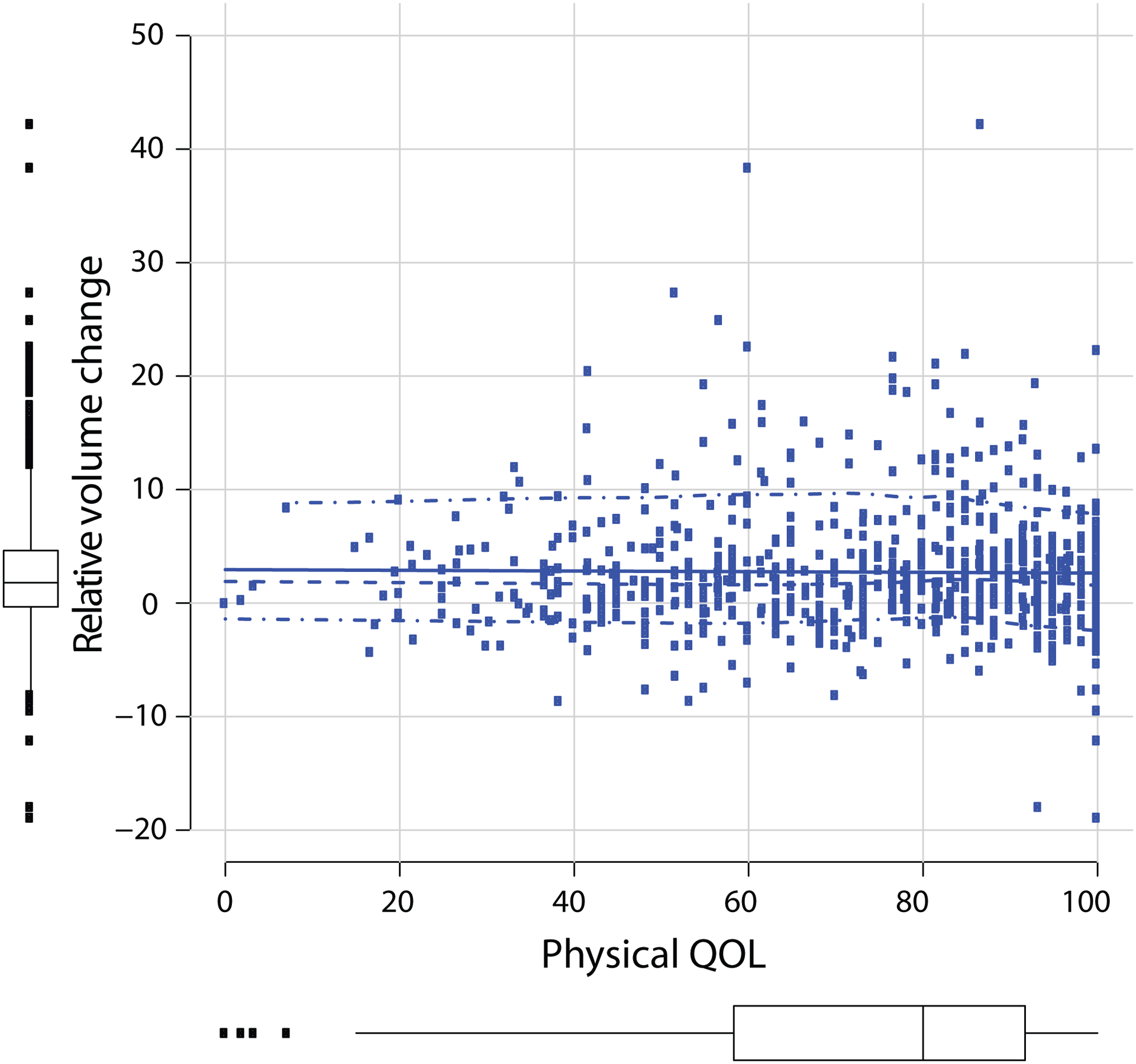

Univariate associations with physical QOL are listed in Table 2. On multivariable analysis, after adjusting for baseline scores, referral to lymphedema therapy (β = −5.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] −10.0 to −1.6, p = 0.006) was predictive of lower QOL scores (Table 2). RVC was not independently associated with worse QOL on MVA (,β = −0.2, 95% CI −0.5 to 0.2, p = 0.427). When analyzed as a binary value with RVC ≥ 10% vs. RVC < 10%, RVC was not associated with physical QOL scores (p = 0.603) (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Physical QOL

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Beta (95% CI) | p | Beta (95% CI) | p |

| Age | 0.11 (−0.04–0.27) | 0.2 | ||

| Baseline BMI | −0.56 (−0.85– −0.28) | < 0.001 | −0.2 (−0.55–0.25) | 0.471 |

| Dominant arm affected | −3.5 (−6.8– −0.09) | 0.044 | −4.5 (−8.7– −0.24) | 0.038 |

| Race | < 0.001 | 0.419 | ||

| White | — | — | ||

| Asian | −4.3 (−9.6–0.95) | −4.9 (−11.7–1.9) | ||

| Black | −9.4 (−14– −5.0) | −1.8 (−7.7–4.0) | ||

| Hispanic | −15 (−23– −7.5) | −9.2 (−21.2–2.8) | ||

| Other/unknown | −8.7 (−19–1.6) | −4.4 (−15.6–6.7) | ||

| Clinical T stage | 0.5 | |||

| 1 | — | |||

| 2 | 0.76 (−3.7–5.2) | |||

| 3 | −1.1 (−6.7–4.4) | |||

| 4 | −3.6 (−9.3–2.1) | |||

| Unknown | −4.8 (−19–9.9) | |||

| Clinical N stage | < 0.001 | 0.210 | ||

| 0 | — | — | ||

| 1 | −9.3 (−13– −5.6) | −4.3 (−11.0–2.5) | ||

| 2 | −11 (−22–0.30) | −3.2 (−22.0–15.7) | ||

| 3 | −18 (−24– −12) | −12.9 (−24.9– −1.0) | ||

| Histology | 0.041 | 0.467 | ||

| Ductal | — | — | ||

| Lobular or mixed | 6.0 (1.1–11) | 1.5 (−3.84–6.8) | ||

| Other | 5.9 (−7.5–19) | 2.6 (−7.8–13.0) | ||

| Subtype | 0.001 | 0.175 | ||

| HR+/HER2– | — | — | ||

| HER2+ | −7.9 (−12– −3.7) | −4.5 (−10.2–1.2) | ||

| HR–/HER2– | −2.5 (−7.7–2.8) | 2.8 (−4.3–9.9) | ||

| Type of surgery | 0.007 | 0.934 | ||

| Breast−conserving surgery | — | — | ||

| Mastectomy | 5.4 (1.5–9.3) | −0.2 (−5.7–5.2) | ||

| Reconstruction | 0.049 | |||

| No reconstruction | — | |||

| Flap | 6.0 (0.06–12) | |||

| Tissue expander | 4.9 (0.64–9.2) | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | −7.7 (−11– −4.2) | < 0.001 | −0.1 (−6.5–6.3) | 0.979 |

| No. lymph nodes removed | −0.09 (−0.31–0.13) | 0.4 | ||

| No. positive lymph nodes | −0.08 (−0.35–0.20) | 0.6 | ||

| Relative volume change | −0.37 (−0.65– −0.09) | 0.011 | −0.2 (−0.5–0.2) | 0.427 |

| Baseline physical QOL | 0.75 (0.62–0.87) | < 0.001 | 0.7 (0.4–0.8) | < 0.001* |

| Change in BMI | −0.06 (−0.64–0.52) | 0.8 | ||

| Radiotherapy | −8.3 (−15– −1.5) | 0.017 | 4.8 (−4.2–13.7) | 0.297 |

| Nodal radiotherapy | −7.8 (−14– −1.2) | 0.02 | −8.2 (−16.3− −0.1) | 0.047 |

| Referral to lymphedema therapy | −10.0 (−13– −6.6) | < 0.001 | −5.8 (−10.0− −1.6) | 0.006* |

| Time | 0.100 | |||

| 6 months | — | |||

| 12 months | 3.3 (−0.8–7.5) | |||

| 18 months | 2.7 (−2.2–7.6) | |||

| 24 months | 6.3 (1.1–11.0) | |||

Statistically significant p−value < 0.0167 as calculated using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons

QOL quality of life, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, HR hormone receptor

Fig. 2.

Physical quality of life vs. relative arm volume change as a continuous variable. QOL quality of life

Psychological and Social Domains

Univariate associations with psychological and social domains are listed in Tables 3 and 4. On multivariable analysis, after adjusting for baseline score, increasing age was associated with higher psychological QOL scores (β = 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5, p = 0.005), while referral to lymphedema therapy was associated with lower psychological QOL scores (β = −5.8, 95% CI 10.0 to −1.7, p = 0.006) (Table 3). After adjusting for baseline social QOL, no factors were associated with social QOL on multivariable analysis (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Psychological QOL

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Beta (95% CI) | p | Beta (95% CI) | p |

| Age | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.005* |

| Baseline BMI | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 0.008 | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) | 0.022 |

| Dominant arm affected | −2.8 (−5.9–0.4) | 0.088 | ||

| Race | 0.6 | |||

| White | — | |||

| Asian | 0.19 (−4.8–5.2) | |||

| Black | 1.7 (−2.5–6.0) | |||

| Hispanic | −4.6 (−12–3.0) | |||

| Other/unknown | −3.8 (−13–5.9) | |||

| Clinical T stage | 0.2 | |||

| 1 | — | |||

| 2 | −0.01 (−4.3–4.2) | |||

| 3 | −2.3 (−7.5–2.9) | |||

| 4 | 4.2 (−1.2–9.5) | |||

| Unknown | 4.1 (−9.4–18) | |||

| Clinical N stage | 0.045 | |||

| 0 | — | — | 0.444 | |

| 1 | −2.8 (−6.3–0.78) | −5.4 (−12.3–1.5) | ||

| 2 | −5.2 (−16–5.4) | −7.0 (−21.5–7.5) | ||

| 3 | −8.4 (−14– −2.4) | −7.3 (−18.0–3.3) | ||

| Histology | 0.4 | |||

| Ductal | — | |||

| Lobular or mixed | −0.16 (−4.8–4.4) | |||

| Other | 8.5 (−3.9–21) | |||

| Subtype | 0.2 | |||

| HR+/HER2– | — | |||

| HER2+ | −3.4 (−7.4–0.54) | |||

| HR–/HER2– | 0.05 (−5.0–5.1) | |||

| Type of surgery | 0.6 | |||

| Breast-conserving surgery | — | |||

| Mastectomy | −1.0 (−4.7–2.7) | |||

| Reconstruction | 0.039 | |||

| No reconstruction | — | |||

| Flap | −1.2 (−7.1–4.7) | |||

| Tissue expander | −5.2 (−9.5– −0.93) | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | −3.4 (−6.8–0.0) | 0.05 | 0.5 (−6.3–7.3) | 0.883 |

| No. lymph nodes removed | −0.05 (−0.27–0.17) | 0.6 | ||

| No. positive lymph nodes | −0.10 (−0.38–0.19) | 0.5 | ||

| Relative volume change | −0.13 (−0.40–0.14) | 0.3 | ||

| Baseline psychological QOL | 0.30 (0.20–0.41) | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.001 * |

| Change in BMI | 0.13 (−0.42–0.68) | 0.6 | ||

| Radiotherapy | −0.37 (−7.0–6.2) | > 0.9 | ||

| Nodal radiotherapy | −0.41 (−6.8–5.9) | > 0.9 | ||

| Referral to lymphedema therapy | −7.0 (−10– −3.8) | < 0.001 | −5.8 (−10.0– −1.7) | 0.006 * |

| Time | 0.2 | |||

| 6 months | — | |||

| 12 months | 0.4 (−3.5–4.3) | |||

| 18 months | 1.8 (−2.7–6.4) | |||

| 24 months | 4.8 (−0.01–9.6) | |||

Statistically significant p−value < 0.0167 as calculated using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison adjustment

QOL quality of life, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, HR hormone receptor

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Social QOL

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Beta (95% CI) | p | Beta (95% CI) | p |

| Age | 0.12 (−0.03–0.26) | 0.11 | ||

| Baseline BMI | 0.01 (−0.25–0.28) | > 0.9 | ||

| Dominant arm affected | −2.1 (−5.2–0.96) | 0.2 | ||

| Race | 0.13 | |||

| White | — | |||

| Asian | −1.0 (−6.0–3.9) | |||

| Black | −1.6 (−5.6–2.5) | |||

| Hispanic | −4.3 (−12–3.0) | |||

| Other/unknown | −12 (−22– −2.3) | |||

| Clinical T stage | 0.10 | |||

| 1 | — | |||

| 2 | 0.63 (−3.5–4.7) | |||

| 3 | −3.3 (−8.3–1.8) | |||

| 4 | −4.8 (−10.0–0.46) | |||

| Unknown | 4.2 (−9.1–18) | |||

| Clinical N stage | 0.003 | 0.309 | ||

| 0 | — | — | ||

| 1 | −5.3 (−8.7– −1.9) | −4.3 (−9.8–1.3) | ||

| 2 | −8.6 (−19–1.8) | −8.9 (−27.3–9.6) | ||

| 3 | −9.0 (−15– −3.2) | −8.5 (−18.9–1.8) | ||

| Histology | 0.3 | |||

| Ductal | — | |||

| Lobular or mixed | 3.4 (−1.1, –7.9) | |||

| Other | 3.6 (−8.7–16) | |||

| Subtype | 0.057 | |||

| HR+/HER2– | — | |||

| HER2+ | −3.9 (−7.7–0.00) | |||

| HR–/HER2– | −4.3 (−9.1–0.59) | |||

| Type of surgery | 0.5 | |||

| Breast−conserving surgery | — | |||

| Mastectomy | 1.1 (−2.5–4.7) | |||

| Reconstruction | 0.6 | |||

| No reconstruction | — | |||

| Flap | 2.8 (−3.0–8.5) | |||

| Tissue expander | 0.95 (−3.2–5.1) | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | −4.3 (−7.6– −1.0) | 0.01 | 0.3 (−5.2–5.8) | 0.916 |

| No. lymph nodes removed | 0.04 (−0.16–0.25) | 0.7 | ||

| No. positive lymph nodes | 0.12 (−0.13–0.38) | 0.3 | ||

| Relative volume change | −0.06 (−0.32–0.20) | 0.6 | ||

| Baseline social QOL | 0.42 (0.31–0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.001 * |

| Change in BMI | 0.19 (−0.37–0.75) | 0.5 | ||

| Radiotherapy | 0.37 (−5.9–6.7) | > 0.9 | ||

| Nodal radiotherapy | −0.18 (−6.3–.9) | > 0.9 | ||

| Referral to lymphedema therapy | −3.5 (−6.7– −0.42) | 0.026 | −2.2 (−6.2–1.8) | 0.284 |

| Time | 0.6 | |||

| 6 months | — | |||

| 12 months | 1.9 (−1.9–5.7) | |||

| 18 months | 2.0 (−2.4–6.5) | |||

| 24 months | 2.4 (−2.3–7.2) | |||

Statistically significant p−value < 0.0167 as calculated using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison adjustment

QOL quality of life, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, HR hormone receptor

DISCUSSION

Our prospective study of 242 patients treated with unilateral ALND demonstrated that QOL initially decreased in the postoperative period in the physical, psychological, and social domains, improved by 6 months post-surgery, and remained stable through 2 years of follow-up. While we used the ULL-27 survey due to its focus on upper extremity symptoms after axillary surgery and their effect on QOL, symptoms in the extremity can be affected by a variety of factors including weight gain, type and timing of reconstruction, and adjuvant therapies including radiation.9 Improvement in QOL scores likely occurs over time as symptoms and side effects from surgery and additional treatments resolve.

Our study demonstrated similar continued improvements in QOL to those reported in a prior study from MSK evaluating 187 patients, 71% of whom were treated with SLNB and 29% with SLNB followed by ALND. That study reported on the presence of 18 sensations, including tenderness, soreness, aching, and stiffness amongst others.4 The two most reported postoperative sensations, tenderness, and soreness, had the highest prevalence in the immediate postoperative period but decreased in frequency starting at 3 months after surgery, similar to our study.

Referral for lymphedema treatment occurred more frequently in patients with worse physical and psychological QOL, with patients experiencing perceived arm swelling more likely to request treatment. As we were unable to demonstrate an association between subjective arm swelling and objective lymphedema, many of these referrals for lymphedema therapy occurred without evidence of measured lymphedema. Previous studies have demonstrated poor concordance between subjective and objective lymphedema, often with a greater proportion of patients reporting subjective lymphedema without objective lymphedema.2,10,11 Although patient-reported symptoms are important in the evaluation of lymphedema, defining lymphedema based on symptoms alone may not be reliable using non-validated surveys. The study by McLaughlin et al. reported that sensory changes, particularly numbness, can occur in up to 55% of ALND patients, which may be misinterpreted by patients as arm swelling.11 These changes may be especially prevalent in practices where the intercostobrachial nerve is routinely sacrificed during ALND. Postoperative instruction to educate patients about signs and symptoms of lymphedema is routine for patients who undergo ALND at our institution, and thus heightened awareness of lymphedema may lead to increased reporting of symptoms. Nonetheless, our study suggests that a key driver of change in QOL may be related to symptoms that may be present even in the absence of objective lymphedema.

Another potential reason that we did not identify a correlation between subjective arm swelling and objective lymphedema may be our relatively short follow-up time. While the number of lymphedema cases in our study is substantial at 18 months, with more lymphedema cases, we may observe an association between increasing arm volume and worse physical QOL. In addition, it is unknown whether subjective arm symptoms are a risk factor for subsequent lymphedema development. With further follow-up, we plan to examine the relationship between physical QOL scores and lymphedema development to determine if the lower physical dimension scores can be used to identify patients at risk for future lymphedema. In addition, we will determine whether lymphedema therapy improves individual QOL over time, and assess whether other patient or clinical factors may contribute to worse QOL.

One of the difficulties in interpreting QOL questionnaires is the potential contribution of symptoms related to other aspects of treatment such as radiation, chemotherapy, and/or reconstruction to survey responses. In addition, the psychological impact of the patient’s breast cancer diagnosis can also affect responses to the questionnaire. This is particularly true for the psychological and social domains of the ULL-27, which include questions about mood, distress, and social activities as they relate to impairments in the upper extremity; answers in these domains may be more reflective of a person’s overall well-being. For example, we observed that older patients had better psychological QOL after ALND compared with younger patients. Improved emotional well-being, including lower anxiety, better coping, less stress related to change in appearance, less depressive feelings, and less fear of recurrence has been demonstrated in older patients with breast cancer12 and other cancers.13 Thus, the effect of age on psychological QOL in our study may not be specific to upper extremity symptoms, but rather reflective of psychological well-being as a whole, for which scores have been shown to be lower in younger patients with cancer.13

Our study addressed the knowledge gap regarding upper limb-specific QOL after ALND. In addition to the short follow-up time, other limitations include those inherent to evaluating QOL using a questionnaire, including recall bias and inability to account for dynamic changes in multiple domains of well-being. However, as patients were asked to recall arm symptoms over a short time frame (4 weeks), recall bias is likely minimal. In addition, side effects of treatments including neuropathy from chemotherapy may cause impairment in ULL scores that are not attributable to lymphedema. Strengths of our study include the large cohort of patients treated with ALND followed by prospective longitudinal arm volume measurements performed in a standardized fashion, which allowed accurate correlation between objective measurements and subjective symptoms. Use of the validated ULL-27 survey, which is specific to upper extremity symptoms, provided a robust assessment of symptoms attributable to ALND over time.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that QOL after ALND decreases in the initial postoperative period and then recovers to near baseline levels by about 6 months, where it remains stable. Younger age and referral for lymphedema therapy were associated with worse QOL related specifically to upper limb lymphedema. While the effect of younger age is likely related to heightened overall cancer distress compared with older patients, the association of referral for lymphedema therapy was a reflection of increased upper extremity symptomatology, reflected in the lower physical and psychological QOL scores. Notably, we did not find an association between subjective and objective arm swelling, confirming the discordance between perceived and objective lymphedema observed in other studies. Longer follow-up is needed to understand the relationship between subjective arm symptoms and lower physical QOL scores in the early postoperative period and subsequent lymphedema development, as identification of a high-risk cohort assessed via early symptomatology could provide an opportunity for early intervention and therapy.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

This prospective study found that quality of life (QOL) after axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer patients worsens after surgery but improves by 6 months. Younger age, and symptoms necessitating lymphedema therapy were associated with worse QOL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The preparation of this study was supported in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA008748 to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and this study was supported in part by a Chanel Survivorship Endowment Award and the Manhasset Women’s Coalition Against Breast Cancer. Dr. Babak Mehrara is an advisor to PureTech Corp and the principal investigator of an investigator-initiated research Grant from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Monica Morrow has received honoraria from Exact Sciences and Roche. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was presented in poster format at the Society of Surgical Oncology 2021 International Conference on Surgical Cancer Care Virtual Meeting, March 18–20, 2021.

Disclosures:

The preparation of this study was supported in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA008748 to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and this study was supported in part by a Chanel Survivorship Endowment Award and the Manhasset Women’s Coalition Against Breast Cancer. Dr. Babak Mehrara is an advisor to PureTech Corp and the principal investigator of an investigator-initiated research Grant from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Monica Morrow has received honoraria from Exact Sciences and Roche. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was presented in poster format at the Society of Surgical Oncology 2021 International Conference on Surgical Cancer Care Virtual Meeting, March 18–20, 2021.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer S, Blettner M, Kreienberg R, et al. Breast Cancer Patients’ Fear of Treatment: Results from the Multicenter Longitudinal Study BRENDA II. Breast Care (Basel). Apr 2015;10(2):95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. Aug 20 2007;25(24):3657–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. Aug 7 2003;349(6):546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron RH, Fey JV, Borgen PI, Stempel MM, Hardick KR, Van Zee KJ. Eighteen sensations after breast cancer surgery: a 5-year comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. May 2007;14(5):1653–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. May 3 2006;98(9):599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopec JA, Colangelo LH, Land SR, et al. Relationship between arm morbidity and patient-reported outcomes following surgery in women with node-negative breast cancer: NSABP protocol B-32. J Support Oncol. Mar 2013;11(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ancukiewicz M, Russell TA, Otoole J, et al. Standardized method for quantification of developing lymphedema in patients treated for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. Apr 1 2011;79(5):1436–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Launois RMA, Pocquet K, Alliot F. A specific quality of life scale in upper limb lymphedema: the ULL-27 questionnaire. In: Campisi CWM, Witte CL, ed. Progress in lymphology XVIII International Congress of Lymphology. Vol Lymphology 35 (Suppl):1–760, 2002: 181–187. Genoa (Italy)2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennman-Larsen A, Petersson LM, Saboonchi F, Alexanderson K, Vaez M. Consistency of breast and arm symptoms during the first two years after breast cancer surgery. Oncol Nurs Forum.Mar 2015;42(2):145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981–22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. Nov 2014;15(12):1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, et al. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: patient perceptions and precautionary behaviors. J Clin Oncol. Nov 10 2008;26(32):5220–5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matutino ARBL, Jacqueline; Verma Sunil; Taylor Ardythe; Huber Sylvia. The impact of age in the quality of life of patients diagnosed with breast cancer after curative treatment [abstract]. Journal of Clinical Oncology. March 01, 2018. 2018;36.7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghanem I, Castelo B, Jimenez-Fonseca P, et al. Coping strategies and depressive symptoms in cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. Mar 2020;22(3):330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.