Abstract

The focus on the role of parenting in child development has a long-standing history. When measures of parenting precede changes in child development, researchers typically infer a causal role of parenting practices and attitudes on child development. However, this research is usually conducted with parents raising their own biological offspring. Such research designs cannot account for the effects of genes that are common to parents and children, nor for genetically influenced traits in children that influence how they are parented and how parenting affects them. The aim of this monograph is to provide a clearer view of parenting by synthesizing findings from Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS).

EGDS is a longitudinal study of adopted children, their birth parents, and their rearing parents studied across infancy and childhood. Families (N = 561) were recruited in the United States through adoption agencies between 2000–2010. Data collection began when adoptees were 9 months old (males = 57.2%; White 54.5%, Black 13.2%, Hispanic/Latinx 13.4%, Multiracial 17.8%, other 1.1%). The median child age at adoption placement was 2 days (M = 5.58, SD = 11.32). Adoptive parents were in their 30s and predominantly White, coming from upper-middle- or upper-class backgrounds with high educational attainment (a mode at 4-year college or graduate degree). Adoptive parents were mostly heterosexual couples, married at the beginning of the project. The birth parent sample was more racially and ethnically diverse, but the majority (70%) were White. At the beginning of the study, most birth mothers and fathers were in their 20s, with a mode of educational attainment at high school degree, and few of them were married. We have been following these family members over time, assessing their genetic influences, prenatal environment, rearing environment, and child development.

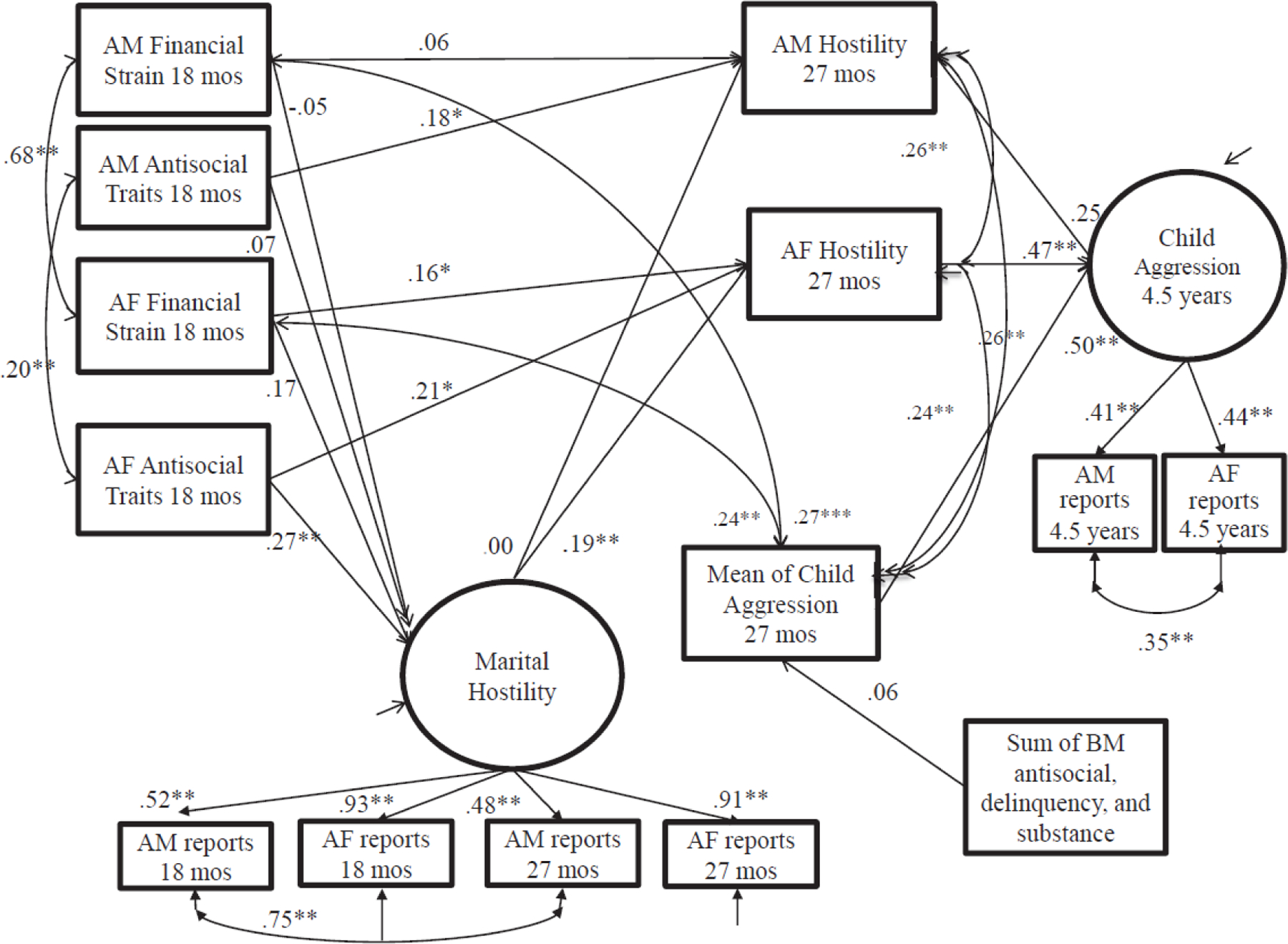

Controlling for effects of genes common to parents and children, we confirmed some previously reported associations between parenting, parent psychopathology, and marital adjustment in relation to child problematic and prosocial behavior. We also observed effects of children’s heritable characteristics, characteristics thought to be transmitted from parent to child by genetic means, on their parents and how those effects contributed to subsequent child development. For example, we found that genetically influenced child impulsivity and social withdrawal both elicited harsh parenting, whereas a genetically influenced sunny disposition elicited parental warmth. We found numerous instances of children’s genetically influenced characteristics that enhanced positive parental influences on child development or that protected them from harsh parenting. Integrating our findings, we propose a new, genetically informed process model of parenting. We posit that parents implicitly or explicitly detect genetically influenced liabilities and assets in their children. We also suggest future research into factors such as marital adjustment, that favor parents responding with appropriate protection or enhancement. Our findings illustrate a productive use of genetic information in prevention research: helping parents respond effectively to a profile of child strengths and challenges rather than using genetic information simply to identify some children unresponsive to current preventive interventions.

Chapter I: The Prospective Parent-Offspring Adoption Design: An Introduction to the Monograph

“Foolishness is bound in the heart of the child, but the rod of discipline will drive it far from him.” (Proverbs 22:15). For millennia, clergy and laity alike believed in the strong influence of parenting and parents’ mental health on the development of their children. Careful observation, supplementing ancient beliefs, noted a variety of other influences on children’s development, from neighborhood to peer group to day care and schools. However, the most serious challenges to ancient beliefs have come from the field of genetics. First were challenges to how mental health of parents may affect children’s development. For example, children of parents with alcoholism are likely to have alcohol problems only if they are biological offspring, but not if they are adopted, suggesting that the transmission of alcoholism from parent to child is genetic (Marmorstein, Iacono, & McGue, 2012). Second, and more surprising, parents’ genetic makeup appears to influence their child rearing practices, such as the harshness of their discipline (Klahr & Burt, 2014). Following from this were data suggesting that observed relationships between parenting and child development might be due to genetic factors that influenced parenting and, when passed down to offspring, influenced their behavioral development. Currently, it is urgent that we clarify in what ways parenting matters for children by using research designs that allow a fuller understanding of the role of both genetic and environmental mechanisms in the relationships between parents and their children. One major approach to this challenge is the study of relationships among adopted children and their birth and rearing parents. This monograph presents results and applications from a prospective parent-offspring adoption study called the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS; Leve et al., 2019). We have studied birth parents, the children they placed for adoption, and the adopted children’s rearing parents. We began our study during the adopted children’s infancy and have continued our observations through adolescence. Our plans are to continue studying these children well into their adult years. Within this illuminating design, we have been able to observe the interplay of genetic and environmental mechanisms that account for the transmission of behavioral patterns from parent to child and from child to parent. The overall aims of this monograph are to summarize the unique features of this type of adoption design, to summarize what it can reveal about parent and child effects on children’s behavioral development, and to integrate our findings into a genetically informed model of family process. We do so by describing and synthesizing exemplar findings from the study’s published papers. We include a final set of chapters that present a new, genetically informed framework and that link our findings to implications for prevention and intervention, with the ultimate objective of sufficiently applying knowledge to inform the development of new initiatives that can modify the developmental trajectories of maladaptive behaviors.

This monograph is divided into nine chapters. In this first chapter, we briefly describe the history of adoption research, current perspectives on family transmission mechanisms, and the opportunities afforded by the design of the EGDS. Chapter II describes the EGDS design, measures, and analytic approaches. Chapter III discusses associations between parenting and parental characteristics and child development, illustrating how our study removes the confounding effects of shared genes between parent and child. This feature of the adoption study is a design element not possible when children are raised by their biological parents. Chapter IV describes a second feature of the adoption design: the ability to examine child effects on their rearing parents and on their rearing environment. We delineate how these child effects can sometimes be traced back to specific genetically influenced characteristics that children have inherited from their birth parents, and how child effects can initiate a dynamic and transactional process that serves to reinforce the child’s trajectory towards problematic or adaptive behavior. Chapter V presents the third methodological advantage provided by the adoption design: the ability to examine whether inherited qualities in children can modify the impact on them of positive and negative qualities of the rearing environment. We also have evidence that specific characteristics of the rearing environment can modify child behavior (Hyde et al., 2016; Waller et al., 2016). The longitudinal effects of rearing environments and reciprocal parent-child interactions are the focus of Chapter VI. Chapter VII leverages the findings from Chapters III – VI to outline a new, genetically informed model of parent-child relationships. The monograph concludes (Chapter VIII) by linking findings from EGDS to preventive interventions, with implications for prevention science. Chapter VIII rests on our findings from Chapters III – VI, suggesting that: (1) children bring characteristics to their families that are influenced by genetic factors and by the prenatal environment; (2) rearing parents show evidence of responding to these characteristics in their direct behavior towards their children, in their relationships with their spouse or partner, and in their self-descriptions as parents; and (3) some parents provide their children with an environment that reinforces these characteristics to either optimize or hinder development; our data provide clues as to why some parents do optimize and some do not. In addition to discussing implications for prevention, Chapter VIII also presents future directions that we are pursuing by adding a sample of biological and non-biological children – siblings to the adopted children – in the adoptive and birth family homes in EGDS, and how the inclusion of these siblings enhances our ability to link study findings to the field of prevention science. Chapter IX summarizes our findings and our inductively derived model. Throughout each chapter, we note the sample limitations of EGDS and where comparable research with more socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse samples exists, we discuss the extent to which our results are like or different from other studies.

We are fortunate to be conducting this work at a time when there have been great strides in the field of prevention science, specifically studies that have deployed developmental models and used experimental designs to study the effects of early preventive interventions. As we allude to in each chapter and expand upon in Chapter VIII, we focus on a set of preventive and clinical trials where the intervention methods and their timing were derived from developmental studies and where sustained intervention effects on a broad arc of child and adolescent development have been obtained (e.g., F. Campbell et al., 2014; C. P. Cowan, Cowan, & Barry, 2011; Enoch et al., 2016; Heckman, Holland, Makino, Pinto, & Rosales-Rueda, 2017; Heckman & Karapakula, 2019a, 2019b; Kellam et al., 2012; Kerr, DeGarmo, Leve, & Chamberlain, 2014; Olds et al., 2014; Rhoades, Leve, Harold, Kim, & Chamberlain, 2014; Sanders, 2012; Shaw et al., 2019; Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, & Kim, 2016). As noted, these prevention studies are planned experiments designed to test theories of child and adolescent development. In evaluating our own findings derived from the natural experiment of adoption (Rutter, 2005, 2007; Thapar & Rutter, 2019), we ask how our work and the outcome of these studies converge, focusing on how each form of experiment, planned and natural, informs the other. We think that a reciprocal exchange and comparison of findings between planned and natural experiments in child and adolescent development is an important route to transform the present state of developmental studies from one that is heavily freighted by uninterpretable associations to genuine causal science.

A Brief History of Adoption Study Research

A rich history of adoption research paved the way for our study to be successful. Nearly a century has passed since the first scientific adoption study was conducted (Burks, 1927). This study, a doctoral dissertation by Barbara Stoddard Burks under the supervision of Lewis Terman (1927), used data from adopted children to understand genetic and social influences on children’s IQ. Burks collected a sample of White, middle-class California families (Goldberger, 1976); 100 of them were rearing their own children and 200 had adopted a child, most within a few months of birth. Burks measured parental and child IQ, and a “culture index” (parental education, speech habits and interests, and quality of the home library and furnishings). Her results highlight three core findings relevant to the complex transmission of intellectual advantages across generations (Burks, 1927) that remain core components of adoption research today. First, she found that correlations between the Stanford-Binet “mental age” (an approximation of total IQ) of parents and the adopted child’s Stanford-Binet IQ were much lower for the adopting parent-child dyads than the biological parent-child dyads, suggesting that genetic factors account for most of parent-child similarities. Second, she identified modest but significant correlations between the “culture index” of the adopting parents and the adopted child’s IQ, reflecting environmental processes, as there was no genetic relationship between the adoptive parent and child. Third, these same correlations were almost twice as high for biological families as for adoptive families. Differences of this kind suggest that observed association between the home environment and the child’s IQ are partially explained by genes common to parents and their biological offspring. That is, genetic factors in the parents that influence how they shape the home environment, when transmitted to their biological offspring, are expressed in the children’s IQ scores. The Burks study was foundational to the field of adoption research, and many of the design advantages and findings of this first study resonate within the field today.

It is important to note that major controversies arose in the study of genetics and intelligence. Under the cloud of the eugenics movement and its horrifying use by the Nazis, researchers and lay people abhorred research that might be used to classify people as inferior because of innate, inborn deficits (Schulze, Fangerau, & Propping, 2004). Matters were made worse by linking genetics to racial differences in intelligence scores. However, research on the genetics of intelligence — and more broadly on the genetics of psychiatry disorders — has become increasingly acceptable for three major reasons. First, the role of genetic differences among individuals in their intellectual and psychological development can only be ascertained among individuals who share specific risk factors and cultural assets. Later in this monograph, we will summarize, for example, data that the role of genetics in individual differences in intelligence can vary dramatically between groups under severe economic distress compared to those who are economically secure. Second, and because of the first, it is now widely recognized that genetics can only account for individual differences within groups, not differences between groups. Finally, methods of genetic research have improved greatly so it is possible to recognize many environmental factors, specific to individuals, that either enhance or diminish genetic influences. This, as we will show in abundance later in this monograph, includes how children are parented. In some cases, the quality of parenting may dramatically alter the effects of genetic factors: a genetic factor ordinarily thought of as risk may be “converted” into an asset. Yet, environmental effects such as these have not been demonstrated for the inheritance of intelligence.

In the decades following Burks’ seminal contribution, scores of studies have used adoption samples, to explore the dynamics of the adoption process or unique features of the development of adopted children (e.g., Brodzinsky, 2006; Grotevant, 1997). Far fewer have compared adoptive families with families where birth parents rear their own children (see the Colorado Adoption Project for an important exception; Plomin & DeFries, 1983; Rhea, Bricker, Wadsworth, & Corley, 2013). Many of these studies have compared the adoptive family environment or the developmental outcomes of the children in adoptive compared to birth families (for a recent review, see O’Brien & Zamostny, 2016). Even fewer adoption studies have been designed to address the interplay of genetic and environmental processes in the transmission of adaptive and maladaptive social characteristics from parents to their children. These few have played a decisive role in understanding parent-child relationships, especially in the domain of developmental psychopathology. For example, they provided the first widely accepted evidence of the role of genetic factors in the transmission of schizophrenia (Heston, 1966; Kety, Rosenthal, Wender, & Schulsinger, 1968; Rosenthal et al., 1968), the first delineation of the central role of genetic processes in the transmission of alcoholism from parents to children (King et al., 2009; Malone, Iacono, & McGue, 2002; Marmorstein, Iacono, & McGue, 2009), and environmental processes in the transmission of depression (Tully, Iacono, & McGue, 2008). These studies have provided further corroboration and refinement of Burks’ findings on the role of genetic processes in the transmission of cognitive abilities (Plomin, Fulker, Corley, & DeFries, 1997), and the first decisive evidence of gene by environment interaction in the development of psychopathology (Cadoret, Cain, & Crowe, 1983). For a more complete review of the central role of adoption studies in child development studies, see Reiss et al. (2016).

A major extension of Burks’ design by subsequent investigators was adding data about birth parents to adoption study samples, a difficult recruitment feat that often takes years to accomplish in collaboration with community partners. In many of the studies that followed Burks and incorporated birth parent data, these data came from existing records of birth parent hospitalizations, incarceration, or adoption agency records, and reflected parental characteristics manifesting well after the child’s birth (Cadoret & Cain, 1981b; Cadoret et al., 1983; Cloninger, Bohman, & Sigvardsson, 1981; Horn, Loehlin, & Willerman, 1979; Wahlberg et al., 2004). One study assessed birth mothers during their third trimester of pregnancy, with a small number enrolled and assessed postpartum (Plomin et al., 1997). Although these assessments of birth parents were limited, they supported three crucial advances. First, they provided striking evidence of how environmental factors moderated genetic influences on child development, a theme we examine in Chapter V. For example, Cadoret and colleagues (1983) showed that genetic influences on antisocial behavior in children and adults were manifest mainly when the rearing environments were adverse (e.g., the parents had severe psychopathology, were incarcerated, or were separated or divorced). Second, they provided surprising data on specific characteristics that a child at risk for severe psychopathology brings to the family. For example, Wahlberg and colleagues (1997) showed that children of mothers hospitalized for schizophrenia bring a sensitivity to the environment to the family, rather than a nascent thought disturbance. Indeed, adopted children with schizophrenic birth mothers who were raised in well-functioning families showed less evidence of thought disorder than a control group of adopted children whose birth parents had no severe psychiatric disorder, whereas those raised in adverse adoptive environment showed more evidence of thought disturbance (Wahlberg et al., 1997). Finally, access to birth parent data provided the most robust evidence for children’s impact on their parents, a theme we explore in Chapter IV. For example, using the Cadoret sample, Ge and colleagues showed that genetically influenced hostile behavior in adolescents had as much or more influence on parental behavior than did parenting influences on the adolescent (Ge et al., 1996; Plomin, Corley, Caspi, Fulker, & DeFries, 1998).

The launch of the Colorado Adoption Project in 1975 made a major advance in the adoption study design by assessing birth parents directly, rather than relying solely on records or administrative data. The EGDS builds on the design elements of the Colorado Adoption Project and extends the methodological approach one step further, by assessing birth parents longitudinally over time – a design innovation that is presented in Chapter II and incorporated into the analyses and results in Chapters III – VI. To our knowledge, EGDS is the only prospective adoption study with long-term, longitudinal observation of both birth and adoptive parents (both mothers and fathers) and children.

As reviewed above, the science and methods underlying adoption study research have advanced in the century since the very first adoption study. Each generation of new adoption research has built upon the foundation laid by the adoption research that preceded it, while strengthening prior designs. This monograph reports on longitudinal observations of birth parents, rearing parents, and adopted children, with data collected up to age 15 years. We have analyzed data across childhood and report some of those results in this monograph (data collection from age 13 years onwards is still underway as of the writing of this monograph). Our adoption design magnifies the ordinary advantages of a typical longitudinal design in developmental science. We can distinguish between genetic and postnatal environmental effects, and then define whether these genetic or postnatal environmental effects are sustained across development or occur only in restricted time periods. We can also ask whether children’s genetically influenced impacts on their rearing parents are transient, time-specific, or sustained. Finally, we can be more assured that genetically influenced characteristics of our birth parents, who are also followed over time and who are themselves developing young adults, are fully expressed and measured. The next section provides an overview of five specific design advances leveraged in EGDS to strengthen our conclusions about child and family processes.

Distinct Advances Made Possible by the Adoption Design

The adoption design, along with research designs using twins, is a major scientific tool in the field of quantitative genetics. In this field, the influence of genetic factors and environmental factors is estimated by comparing associations between individuals of known genetic relationships. As noted, the very first adoption study by Barbara Burks compared the associations between the intellectual abilities of parents and their biological offspring with the same correlations between adoptive parents and their adopted children. Since the former were higher than the latter, Burks inferred notable genetic influences on intellectual abilities. This is because parents share exactly half their genes with each biological offspring, but adoptive parents share no genes with the children they are raising. Most important among these genes are those that account for individual differences among humans. These are called “segregating genes” because the random allocation of many of them to sperm and eggs account for the contribution of genes to differences among children. The other major tool of quantitative genetics is the twin design. Here, inferences are drawn from comparing the associations of identical twins, who share all segregating genes, with fraternal twins who share approximately half of their segregating genes.

In contrast to quantitative genetics, molecular genetics requires a direct identification of specific genes. Genetic influences on a specific characteristic are assumed if there is notable correlation between a measured gene, or of a set of genes, and that characteristic. As we will discuss, the two approaches often do not align. Quantitative genetics, because its computations reflect the influence of the whole genome, often suggests more genetic influence in a human trait than do molecular techniques. There is a consensus that these discrepancies are due to undiscovered genes or non-genetic portions of the chromosome that influence a characteristic or to the unmeasured effects of interactions among genes. That is, at this stage of the science, molecular genetics often underestimates the effect of genes on human behavioral development. With each new generation of adoption research, new insights into the parent-child relationship were made possible based on advances in the study design, research methods, and analytic approaches. At least five distinctive advances are now possible, which we further highlight in Chapters III – VI. Table 1 illustrates these advances and the associated traditional terminology used in the field of behavioral genetics to describe each feature (where relevant). Throughout this monograph, we refer to these specific processes and effects using terms that will allow us to think about the interplay of biological and social processes in the family, rather than using more traditional behavior genetics terminology. As developmental and prevention scientists, we anticipate that this language will lead more easily to translating our findings for preventive interventions. Nonetheless, some readers will find Table 1 a useful reference tool to assist translation across diverse disciplines.

The first design advance is the removal of the influences of shared genes on associations between adoptive parents and adopted children. When children are placed from birth with adoptive families with whom they are not genetically related, associations between rearing parent characteristics and adopted child characteristics must be attributable to postnatal environmental mechanisms, as parents and children share no segregating or individual difference genes. This feature of the adoption design is different than when children are reared by their biological parents (or are placed with biological family members after birth, including kinship foster care placements), as is traditional in the vast majority of child development research. We explore this novel design feature further and discuss the inferences this feature allows us to make in Chapter III.

The second design feature allows researchers to examine how genetic characteristics in the child can elicit or evoke behaviors from others in the rearing environment in predictable ways. When data from birth parents are collected, researchers can examine the correlation between birth parent and adoptive parent characteristics. Notable correlations between birth parent characteristics and the parenting behavior or family environment of rearing parents provide the strongest evidence currently available for assessing the impact on the rearing parents of their children’s genetically influenced or prenatally acquired characteristics. Richard Q. Bell termed these associations “child effects” (1968). In other words, our adoption design allows us to detect effects that must originate from the child via genetic or prenatal transmission, rather than from the rearing parent. We describe this design feature and associated evidence from EGDS in Chapter IV. More traditional parent-child research has also delineated the effects of children on their parents. However, these designs cannot distinguish between those child characteristics that are intrinsic to the child from those that—earlier in development—reflected parental influence.

Third, the adoption design allows researchers to separate prenatal from postnatal environmental influences. As noted earlier, associations between birth parent characteristics and the development of the child they placed for adoption are ordinarily considered a good indication of the role of genetic factors in these associations. However, known effects of prenatal environments must be considered (or ruled out), and unknown effects are always a possible confound to genetic interpretations. In EGDS, we have been able to collect detailed prenatal medical records and birth parent self-report data on the prenatal period to better understand associations that are genetic in origin and are mediated through prenatal environment, as compared to genetic influences that do not appear to be passed on through prenatal mechanisms. Without careful measurement of the prenatal environment, earlier adoption studies were unable to understand or account for these pathways, which could lead to the misspecification of genetic effects. Studies in Chapters III-VI rigorously control for prenatal environmental influences.

Fourth, although earlier adoption studies used public, clinic, or adoption records for birth parent data (e.g. Cadoret & Cain, 1981a; Cloninger et al., 1981) or birth parent data prior to placement (Plomin et al., 1997), when birth parents are followed longitudinally postpartum we can use statistical methods to generate constructs for birth parent characteristics that incorporate multiple time points and measures, strengthening the reliability of measurement and inferences about the behaviors and characteristics that children acquire from their birth parents. In the entire span of time since the first adoption study—nearly 100 years—the EGDS is the first adoption study to extend the observation of children placed for adoption from infancy onwards while obtaining extensive postpartum assessments across time directly from birth parents. Chapter II describes our longitudinal measurement approach, and Chapters III-VI present examples of measurement that incorporate birth parent characteristics over time.

Fifth, adoption studies that start in infancy can provide glimpses of the earliest expression of genetic influences on child behavior. By examining the associations between favorable or unfavorable characteristics in birth parents, and identifying associations with adopted child characteristics, we can also examine whether these early manifestations of genetic influence (correlations between birth parents and adoptees) are expressed uniformly across families or, depending on the parents’ parenting and other family factors (e.g., the quality of the adoptive couple’s relationship, parent’s social support, or parental well-being), are expressed only in some families. Prospective longitudinal adoption studies that begin early in development can trace these interactive processes beginning in infancy. We discuss these processes and findings in Chapters V and VI. Each of these five design features allows an opportunity to provide novel insights into family processes, and the ways in which children and parents influence each other across development. In the next section, we situate our study within the context of current perspectives of family influences in the field of child development.

The Adoptive Family: Is it a Model for Family Process in Biological Families?

There are two reasons to inquire whether findings from adoptive families are generalizable to the much more numerous studies of biological families of comparable ethnicity, socioeconomic circumstance, and parental age. First, there is a growing body of literature on hormones secreted in the peripartum period, from both maternal and fetal sources, that aid in restructuring the maternal brain — especially during the gestation and birth of the first child. The brain changes are presumed crucial to mothers’ early adaptation to her maternal role (see Champagne & Curley, 2016 for a review of animal studies and recent prospective studies of pregnancy brain changes in first time pregnant women; Hoekzema et al., 2017; Hoekzema et al., 2020). Adoptive mothers get no such boost from hormones associated with childbirth and lactation. Second, the path to adoption can be difficult: the stress of trying to conceive a child, the long, difficult waits for a suitable adoption, and the stigma that may be associated with infertility and adoption may impair adoptive parents’ child rearing.

However, although data remain sparse, the prevailing evidence is that neither of these two circumstances lead to qualitative differences between adoptive and biological families. First, even before they secure an adopted child, couples seeking an adoption show notable strengths in comparison to biological parents expecting their first child. They have more secure attachment to their remembered caregivers and to each other, and they report greater marital satisfaction (Pace, Santona, Zavattini, & Di Folco, 2015). Thus, despite the challenges of the adoption process, it not surprising that infants adopted soon after birth show the same level of secure attachment as children biologically related to their parents in both an earlier single study (Singer, Brodzinsky, Ramsay, Steir, & Waters, 1985) and in a more recent meta-analysis of 17 studies (van den Dries, Juffer, van Ijzendoorn, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009). Exceptions in both studies were transracial and some transnational adoptions, where more adopted children showed insecure attachment in childhood than children raised by their biological parents. Although EGDS does include transracial families, it does not include families who participated in transnational adoptions.

In addition, detailed observational comparisons of adoptive and non-adoptive mothers show both to be responsive, attentive, and respond effectively and contingently to their child’s social and emotional clues (Suwalsky et al., 2012; Suwalsky, Hendricks, & Bornstein, 2008). These behavioral observations have been confirmed by EEG studies of biological and adoptive mothers responding to recordings of crying babies as well as pictures of babies; both groups of mothers were clearly different than non-mothers, suggesting brain functioning had been adapted to motherhood in adoptive mothers without the hormonal changes occasioned by birth and lactation (Perez-Hernandez, Hernandez-Gonzalez, Hidalgo-Aguirre, Amezcua-Gutierrez, & Guevara, 2017). However, one study did find very subtle differences in EEG frequencies that might reflect the absence of these hormonal changes, though the functional significance of these findings seems slight (Hernandez-Gonzalez, Hidalgo-Aguirre, Guevara, Perez-Hernandez, & Amezcua-Gutierrez, 2016).

There are a few reports in the literature that compare adoptive and nonadoptive families when the adopted children are adolescents. These reports are drawn from a study where most of the adoptions were transnational. As noted, young children in transnational adoptions show less favorable attachment security to their rearing parents. Therefore, it is not surprising that parent-child relationships in adoptive families in these reports from a transnational study, when the children become adolescents, show greater conflict and less warmth in parent-child relationships (Rueter, Keyes, Iacono, & McGue, 2009; Samek & Rueter, 2011; Walkner & Rueter, 2014). Thus, these studies have uncertain relevance for our sample, where adoptions were entirely domestic.

Current Developmental Perspectives on Estimating Family Influences

Across many disciplines, the concept of transmission refers to the passing on of some vital characteristic from one person to another. The field of child development has incorporated different theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of familial transmission; four approaches that significantly influenced the EGDS design are presented in this section: family systems, child effects, gene by environment interaction, and prenatal influences.

Family systems.

The development of a family systems perspective has transdisciplinary historical roots. As Kaslow notes (1981) its origins are in the child guidance movement in the early 20th century, but also informed by psychoanalytic theories (Bowlby, 1969; Freud, 1955; Sullivan, 1953), early family therapy (Ackerman, 1958; Bateson, Jackson, Haley, & Weakland, 1956; Minuchin & Fishman, 1979), and eventually, social learning (Patterson, 1982) perspectives. Rather than focusing on individual family members or even individual dyadic relationships, a family systems perspective views the development of both prosocial and problem behavior as a function of an embedded web of relationships among all family members (e.g., siblings, parents, parent-child, and parent-parent interactions). While early research in this area often operationalized a family systems perspective by focusing on only two family members, more recent research has been able to account for interactional processes of more than two family members.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal observations of families and their children, without attempts at intervention, have provided the bulk of quantitative evidence relevant to the family system approach and constitute a major foundation of current developmental psychology. Among the fundamental early efforts to apply a family systems approach were Rutter’s early studies distinguishing the effects on child development of marital conflict from more traditional findings on the effects of parenting and parental absence (Rutter, 1971). In the half century since Rutter’s prescient study, a range of studies have documented these associations of marital quality and many facets of infant, child, and adolescent development (e.g., see a recent review (Harold & Sellers, 2018). Equally central was the New York Longitudinal Study, designed and executed by the child psychiatrists Thomas and Chess. Their study focused on the interplay of child temperament and parental influences (Chess & Thomas, 1990; Chess, Thomas, Rutter, & Birch, 1963). Based on their observations, Chess and Thomas developed brief interventions for parents to help them adjust the unique features of their child’s temperament; this perspective enhanced the “goodness of fit” between the child’s temperament and parental expectations and behavior (Thomas & Chess, 1984). A third important turn in family systems work was a delineation of different roles and effects of mothers and fathers in the development of their children. Much research on fathers was stimulated by family experiences during World War II when the absence of fathers at war raised interest in what the child might be missing when only mothers were in the home (e.g., Sears, Pintler, & Sears, 1946). More nuanced explorations involved direct observations of the interactions of mothers and fathers with their children and an effort to characterize the unique contributions of each (e.g., Power & Parke, 1983). While most socialization studies had previously focused on the effects of maternal parenting on multiple facets of child development (e.g., Maccoby, 1994; 2007), especially in the past decade research also has attempted to identify the unique contributions of paternal caregiving on child development (Cabrera, Fagan, Wight, & Schadler, 2011; Feldman & Shaw, 2021; Paquette & Bigras, 2010; Volling, Stevenson, Safyer, Gonzalez, & Lee, 2019).

Child effects, including those that have genetic origins.

A particular and under-appreciated component of family systems research came from Richard Q. Bell in a foundational paper underscoring the impact of children on their parents, an obvious phenomenon obscured by the very long history of assuming the centrality of parental influence on children’s development (1968). Bell presciently used genetic data in his analysis. He reasoned—as had Chess and Thomas—that heritable child characteristics such as different dimensions of infant temperament influenced parenting behavior.

Following Bell’s initial paper and follow-up volume (1977), the child effects perspective gained additional momentum with a paper written in 1981 by Rowe that cautiously reported evidence from a tiny sample of adolescent twins, that adolescents’ perceptions of the quality of parenting they had received was genetically influenced (Rowe, 1981). Two years later, Rowe published stronger evidence that adolescents’ perception of their parenting was genetically influenced (1983). Although this work was quite controversial at the time, history would prove Rowe’s early findings to have significant merit. In the decades that followed, research underscored genetic influences on a very broad range of measures of the social environment, from social class to marital quality to parenting (Kendler & Baker, 2007; Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2016). This field-changing revelation raised the possibility that any observed association between a measure of environmental influence and a measure of child development could be confounded by genetic influences common to both. There are two ways this can happen. First, an association could be due to the same set of genetic factors that influence a parental variable, for example, harsh parenting, being passed on to a child where those same genetic factors also influence the child’s development of impulsivity and aggression. In the behavioral genetics literature, this phenomenon is known as passive gene-environment correlation, as noted in Table 1. Second, a heritable feature in a child might evoke certain types of parenting and influence the child’s own development as well, and therefore, could account for an apparent environmental effect that was, in fact, mostly or entirely attributable to genetic influences. For example, a child who was genetically at risk to be more aggressive might evoke harsh parenting from their parents. In some cases, this evoked harsh parenting, in turn, might enhance the child’s liability for later impulsive and aggressive behavior. In this instance, the evocative effect of the child’s heritable features must be considered part of the mechanism of genetic expression, though it is “outside the skin” (Kendler, 2001). In the genetically informed literature, this type of child effect is commonly termed evocative gene-environment correlation in the behavioral genetics field, as noted in Table 1. These findings, on both common gene effects and genetically influenced child effects, challenge an extensive line of research that inferred parental inferences simply from their predictive association with child outcomes (see a recent review of these genetically informed studies, (Plomin et al., 2016). Despite frequent reports on this confounding effect across two decades of research (see Jami, Hammerschlag, Bartels, & Middeldorp, 2021; Reiss, 2016 for recent reviews), most parenting studies in the developmental literature do not attend to this potential confound.

The interaction of genetic and environmental influences.

A third perspective on familial transmission evolved from research on the interaction between genetic and environmental influences. Among the earliest examples came during the 1950s, via the discovery of phenylketonuria (PKU) by Folling (1934). This metabolic defect, arising from a single gene regulating the metabolism of a common dietary component (phenylalanine), was expressed as an intellectual disability only when children were fed food containing phenylalanine. Strong proof of this interaction of diet and genetic influence was first demonstrated in a single case clinical trial by Bickel (1953). The concepts underlying the PKU research were first translated to the world of behavioral development using adoption study designs by Cadoret’s groundbreaking studies of gene by environment interaction in the development of aggression and antisocial behavior. Cadoret et al. found that adopted children at genetic risk for antisocial behavior—because their birth parents had severe antisocial and/or alcohol problems—became antisocial themselves only if reared in an adverse family environment of marital strife and/or rearing parent psychopathology (1983). This is an instance of just one of several types of genotype by environment interaction: in the presence of a genetic diathesis, an adverse environment leads to an unfavorable outcome. Closer to Chess and Thomas’ concept of “goodness of fit,” is the work of Wynne and colleagues in a study of children of mothers hospitalized for schizophrenia who were placed for adoption early in development. Those children reared by adopting parents whose verbal communications were confusing and contradictory developed severe thought disorder, whereas those who were raised by adopting parents with clear verbal communication had lower scores on thought disorder than the control group of adopted children without a family history of severe psychiatric disorder (Wahlberg et al., 1997). Recently, many researchers have been interested in a third type of interaction. Some data suggest that children may inherit a sensitivity not only to stress but also to favorable environments (J. Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2007). Children with that genetic makeup might develop psychopathology if they grow up in stressful or abusive families but may have a favorable outcome if their families are warm and supportive. This type of gene by environment interaction has been termed “differential susceptibility.” In subsequent chapters, we examine our own data for corroboration of this idea.

Prenatal environment influences.

A fourth conceptual approach that has informed the development of the EGDS research is a focus on the prenatal environment, and how the experiences that parents have during pregnancy might influence the developing fetus, and ultimately, affect their child’s behavioral and cognitive functioning. Prenatal influences include maternal drug use during pregnancy as well as her emotional state (Hannigan et al., 2018; Yip et al., 2014). As we will show in Chapter IV, the adoption design can be used to estimate some prenatal effects on children’s subsequent development. However, the rapidly growing literature on prenatal influences motivated our extensive measurement of these influences to assure that they were not confounding our estimates of genetic and postnatal environmental influences. Taken together, these major lines of inquiry—family systems, child effects, genetic analysis in the interpretation of apparent environmental influences, and prenatal environmental exposures—are now widely supported by compelling evidence from child developmental studies. This monograph focuses specifically on the prospective parent-offspring adoption design to integrate and advance these prior lines of inquiry. It is worth noting that the adoption design is one of several complementary designs that each advance the understanding of genetic and family transmission in novel ways. Before detailing the EGDS adoption design, we provide a brief review of other study designs that can complement the parent-offspring adoption design in advancing understanding of mechanisms of family transmission.

Current Approaches to Integrating Genetic Information into the Study of Family Relationships

The last three decades of child development research have seen a surge in the number of novel study designs that integrate genetic information into the study of family relationships and child developmental outcomes. Comprehensive systematic reviews that summarize the design types and findings exist (see Jami et al., 2021), so here we provide only a brief overview of some of the recent designs and showcase their novel strengths. In doing so, our intent is to convey that the adoption design, while unique, is part of a family of designs that, when findings are considered together, can greatly advance the understanding of the contributions of children and parents in influencing children’s maladaptive and adaptive outcomes. Here, we briefly discuss the in vitro fertilization design, the children of twins design, and molecular genetics approaches.

In vitro fertilization (IVF).

IVF studies are a close relative of the parent-offspring adoption design and provide a related strategy for comparing parent-child pairs who are genetically related versus those who are not. Specifically, genetically unrelated parent-child pairs result from IVF where both sperm and egg are donated by individuals unrelated to the rearing couple (embryo donation; Harold, Elam, Lewis, Rice, & Thapar, 2012; Rice, Lewis, Harold, & Thapar, 2013). In this sense, this group of IVF families share some of the design features highlighted in Table 1. In addition, IVF designs can contain a pregnancy surrogacy group, where an embryo is implanted into the uterus of a genetically unrelated woman. Selection issues for potential surrogates notwithstanding, the surrogacy group allows for a separation of prenatal and genetic influences in unique ways not afforded by parent-offspring adoption designs like EGDS.

The children of twins (CoT) design.

CoT is a second approach that shares some attributes with the adoption design while offering other novel features related to the detection of common genes and rearing environment effects. In the CoT design, when the rearing parents are monozygotic twins, the child of one twin also shares 50% of their segregating genes with the co-twin (the child’s aunt/uncle). This strategy permits estimation of the effects shared by genes independent of the shared rearing environments (passive gene-environment correlation), and, in the extended CoT approach, allows an estimate of child effects on parents that are genetic in origin (evocative gene-environment correlations). These associations are achieved by simultaneously estimating the impact of children’s genes on their behavior and parents’ genes on their own behaviors (Lynch et al., 2006; Marceau et al., 2013; McAdams et al., 2017; McAdams et al., 2015; Narusyte, Andershed, Neiderhiser, & Lichtenstein, 2007; Narusyte et al., 2011; Narusyte et al., 2008; O’Reilly et al., 2020).

Molecular genetic approaches.

As already noted, a third approach is to use molecular genetic methods to measure genetic influences in the child. This approach has yielded a rich harvest beyond twin and adoption designs—where family processes have been carefully measured—where genetic information comes from the direct assay of particular genes whose variation in structure contributes to individual differences among individuals. These genes are set to be polymorphic (see Reiss, 2016). To date, the most successful approach to these measurements has been genome wide association studies (GWAS). By using exceptionally large samples, these GWAS studies have found that scores and sometimes hundreds of polymorphic genes are reliably associated with behavioral traits—each accounting for a tiny amount of variation in the associated trait. Data from GWAS allow computation of indices of genetic influence that are often referred to as either polygenic scores (PGS) or polygenic risk scores (PRS). These scores can be computed for all individuals in a sample by noting their number of favorable or risk polymorphisms weighted by the degree of association of each of those polymorphisms with the trait or characteristic of interest. These methods are now being integrated into studies of social processes in the family and in broader social processes such as stratification (e.g., D. W. Belsky et al., 2018; Wertz et al., 2019). Although quite distinct in the approach conceptually, the adoption design— through its comprehensive measurement of birth parents—is like the genome-wide approach in a GWAS. Both procedures examine significant portions of genomic effects, with the former being unable to disaggregate the effects of any single gene but typically including more comprehensive measurement of the rearing environment. The next section describes how we have leveraged the design strengths of the adoption design to create a schema for examining the role of parenting in child adjustment and maladjustment across development.

The Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS)

The EGDS is a contribution to the genre of integrated research designs that incorporate genetic information into the study of family relationships. In the rearing family, building on family systems models, we can study the separate impact of mothers and fathers, their combined influences, and the separable impact of qualities of the couple or marital relationship. Using our extensive information about birth parents, we can identify genetically influenced characteristics that the child brings to the family. Through careful measurement of birth mothers’ prenatal environment and incorporation of birth father data, we can consider birth parent influences on adopted children’s development that may be mediated by prenatal exposures and those that do not appear to be mediated by the prenatal exposures measured in EGDS. As noted in Table 1, throughout the monograph we will use the term child effects. This term emphasizes that these are effects of the child on the family system arising from characteristics that children bring to the family rather than reflecting, in whole or in part, earlier influences of the rearing family. As ordinarily used, the term “child effects” includes effects that are direct and originate from genetically influenced or prenatally acquired characteristics, and those that are an influence of the rearing family and then have a subsequent impact of their own on the family. The later form of child effects is best thought of as part of the reciprocal process between parents and children (discussed further in Chapter VII). As we discuss in Chapter III, conventional longitudinal studies of child development cannot distinguish between these two forms of child effects. For emphasis, we use the term “child effects” to refer only to characteristics that children bring to their rearing family.

Adoption design assumptions.

Before presenting a full description and visual schema of the analytic possibilities in EGDS, it is important to provide a comment on potential design assumptions that can interfere with the ability to draw causal inferences about the various aspects of family transmission if these design assumptions are not met. First, the adoption process might selectively place children into rearing families that are like their biological parents or that reflect an effort to counter the possible environment provided by biological parents with adoptive families unlike them (“selective placement”). Second, almost all adoptions in the 21st century are somewhat fluid in terms of contact and knowledge shared between the biological parents, the rearing parents, and the offspring (“adoption openness”). Third, rearing parents—even in closed adoptions—may learn key facts about the biological parents that might alter their expectation for their adopted child and influence their rearing patterns. These expectations can be engendered even in fully closed adoptions if the birth parents learn anything about the characteristics of the birth parents. Fourth, research staff assessing birth parents might influence the assessment of the rearing family. Table 2 presents each of these design assumptions, followed by information about the measurement and analytic approach used in EGDS to address all four of these challenges. Some additional detail is also provided in Chapter II when we present the EGDS measurement approach.

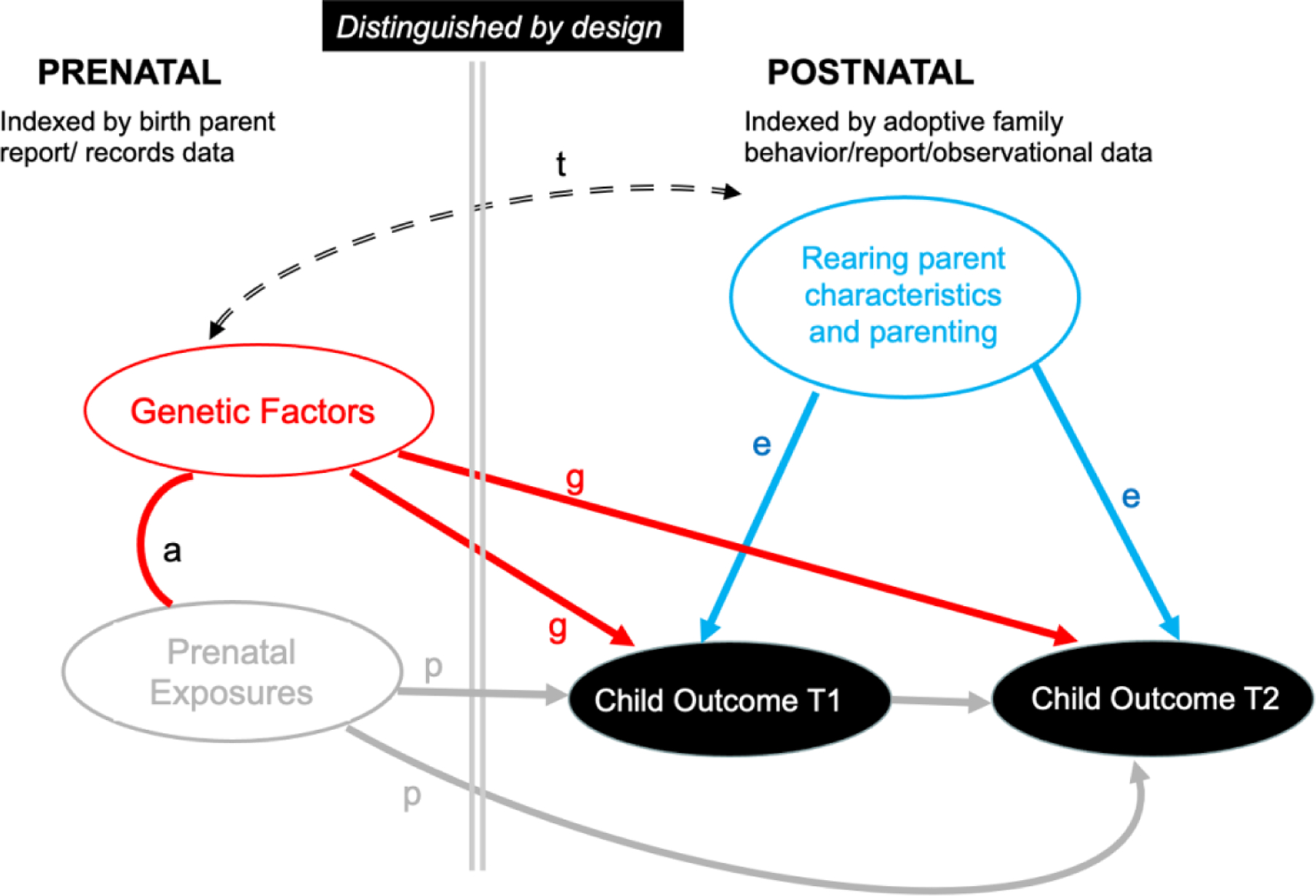

Analytic opportunities in EGDS: A visual schema.

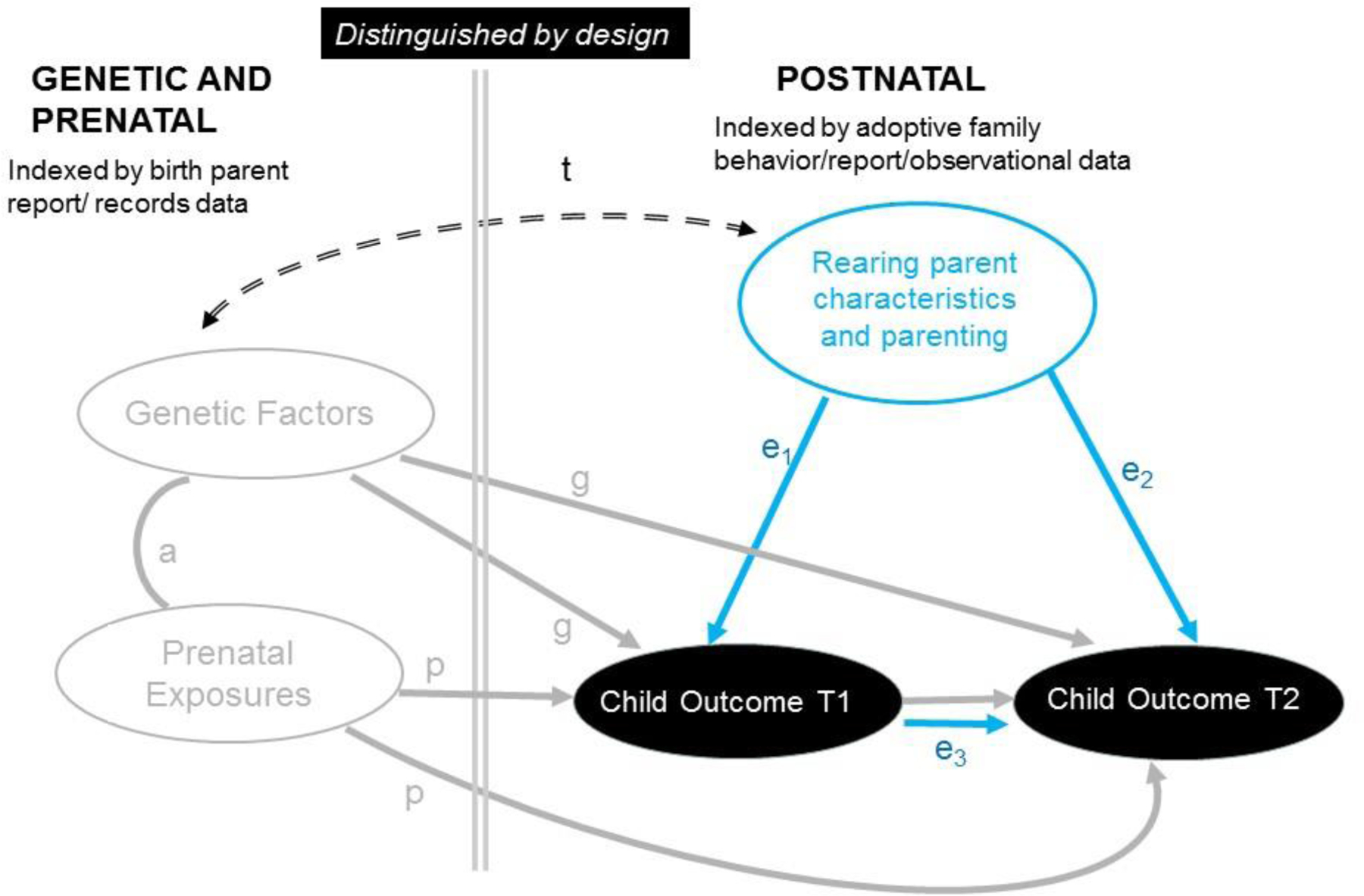

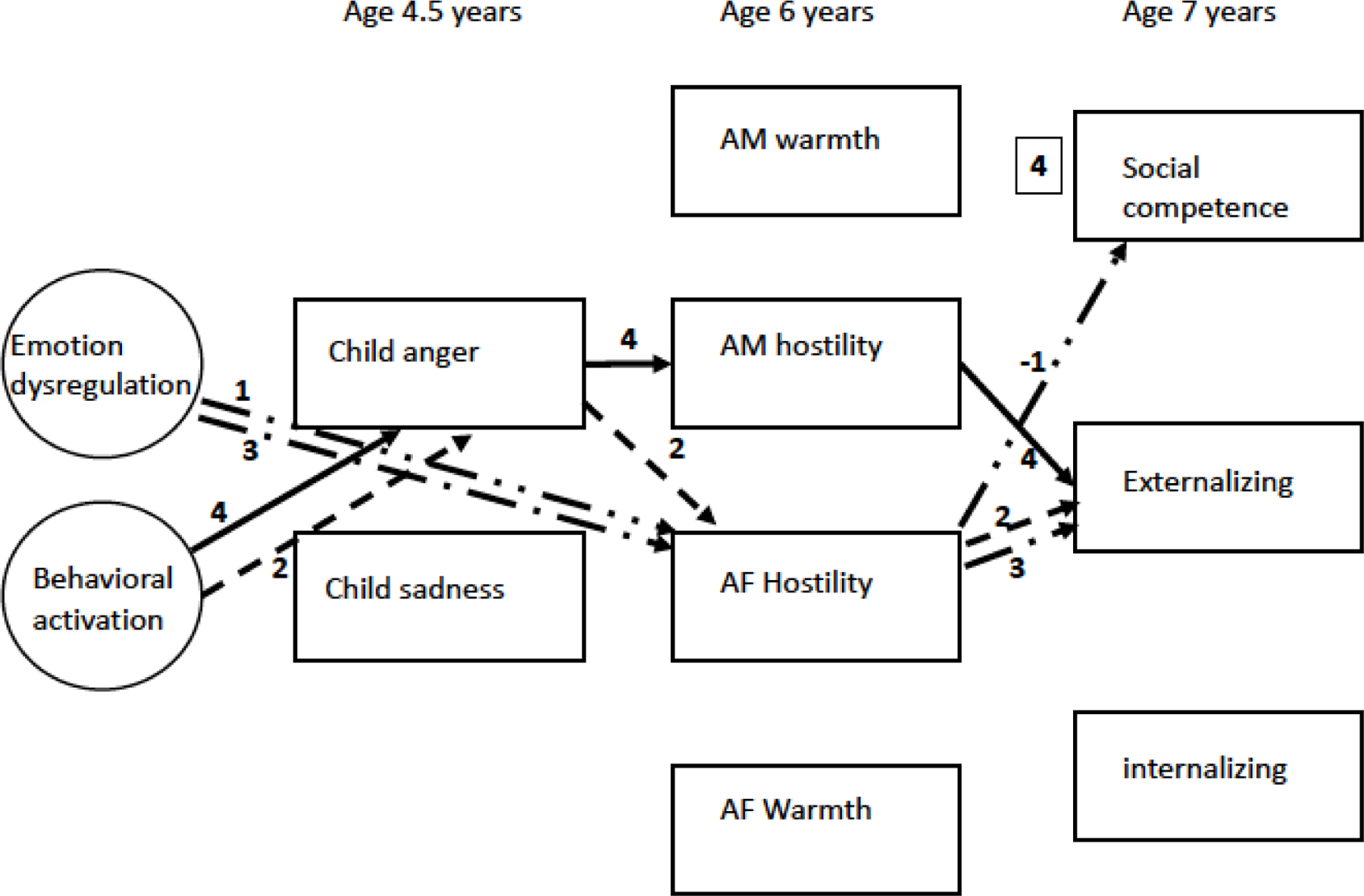

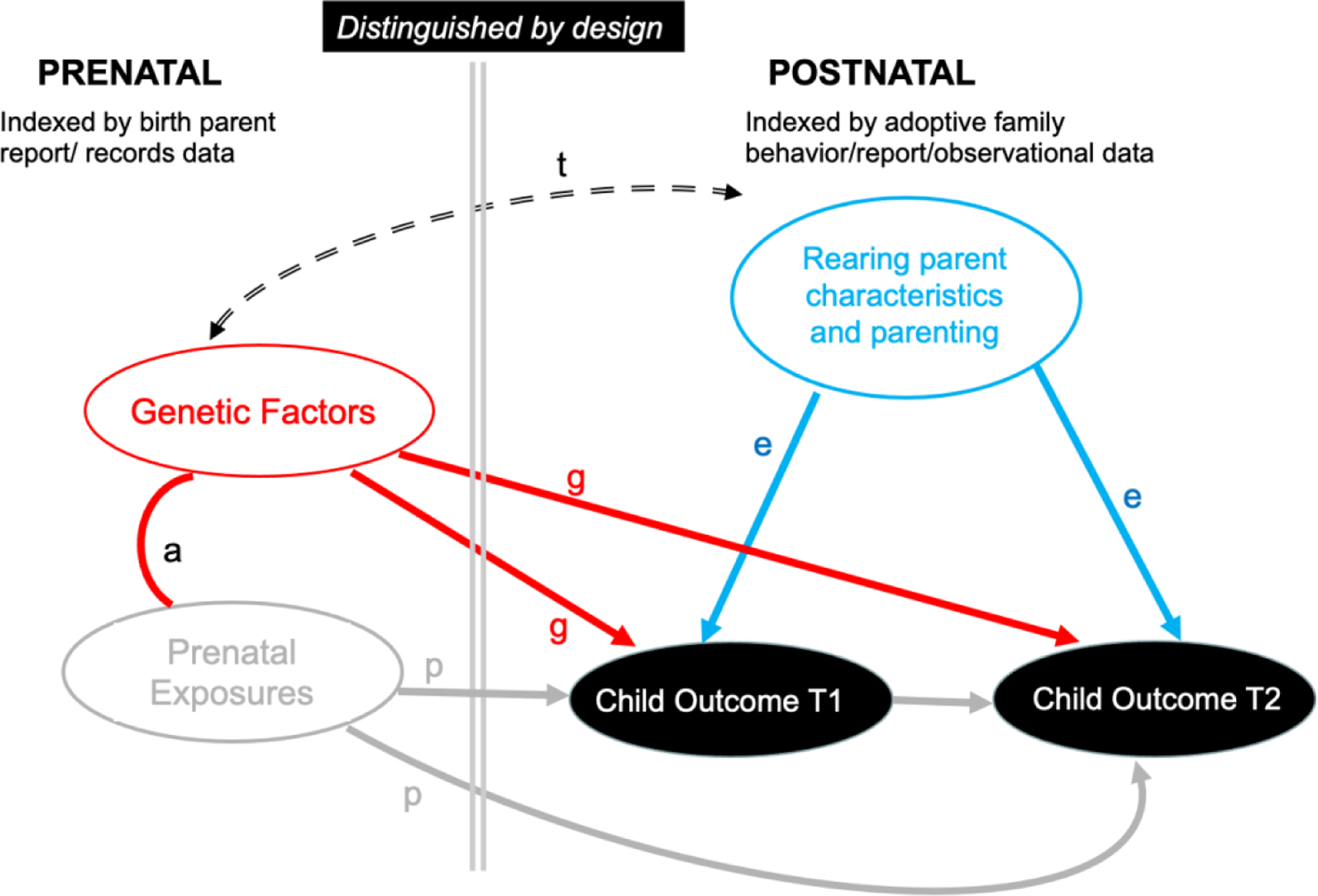

The unique opportunities for analysis in EGDS are illustrated in the schemas presented in Figure 1A through 1D. Figure 1A illustrates the basic logic of the EGDS design. It is built around the separation of influences on child development that occur before birth (prenatal environments and genes passed to the child from birth parents) and those that occur after birth (via the adoptive family environment). As described in Chapter II and re-introduced in subsequent chapters, prenatal and genetic influences are measured by coding obstetrical records (prenatal influences) and by rigorous postnatal interviews of birth mothers and birth fathers using a life-history calendar approach (about the prenatal period and about current characteristics). The separation of prenatal and genetic influences from postnatal influences is reinforced by the design and assessment procedures we describe throughout the monograph. Most studies of parent-child relationships cannot account for the confound between prenatal and postnatal influences; this confound is represented by path t (for “traditional studies”) in all four figures. Of note, associations between facets of the prenatal environment and later child development can be confounded by common gene effects, i.e. genes that influence how parents influence the prenatal environment (such as drug use) that when passed on to their offspring also influence child development. This confounding is emphasized by a recent review (Jami et al., 2021) and by a methodologic critique (Rice, Langley, Woodford, Davey Smith, & Thapar, 2018). One of our solutions to this confounding is to include in our analyses a comprehensive index of the prenatal environment that includes many factors known to affect fetal development. It is then examined as a potential mediator or moderator of genetic influences on child development, or included as a control variable. As Figure 1A shows, our estimates of genetic influences are derived from partialing out known prenatal influences. This partialing is represented by the curved line without arrows, labeled a. Assuming the effectiveness of this partialing, it is possible to independently estimate the influence of genetic factors and postnatal environmental influences provided by parents on child development. A second approach, that we describe in Chapter IV, is to compare the associations with child development of birth mother and birth father scores; where the former exceeds the latter we can infer intrauterine effects. It is also important to note that we do not estimate all genetic influences; only those indexed by specific measures of birth parents that have been included in EGDS. In some studies, we use data just from birth mothers because we recruited birth mothers for all but five children in EGDS, in which case only the birth father was recruited. In other studies, we also included data from birth fathers, often imputing missing data for the 63% that were not recruited into the study. In Figure 1A we have shown “child outcome” at two separate time periods to emphasize schematically the longitudinal nature of our design. We could have extended this schematic to include many additional time periods (see Chapter II for measurement time points), but to ease readability, we only illustrate two. In addition, we could have represented the longitudinal measurements of birth parent and rearing parent in the same manner, but, for simplicity’s sake, have not done so.

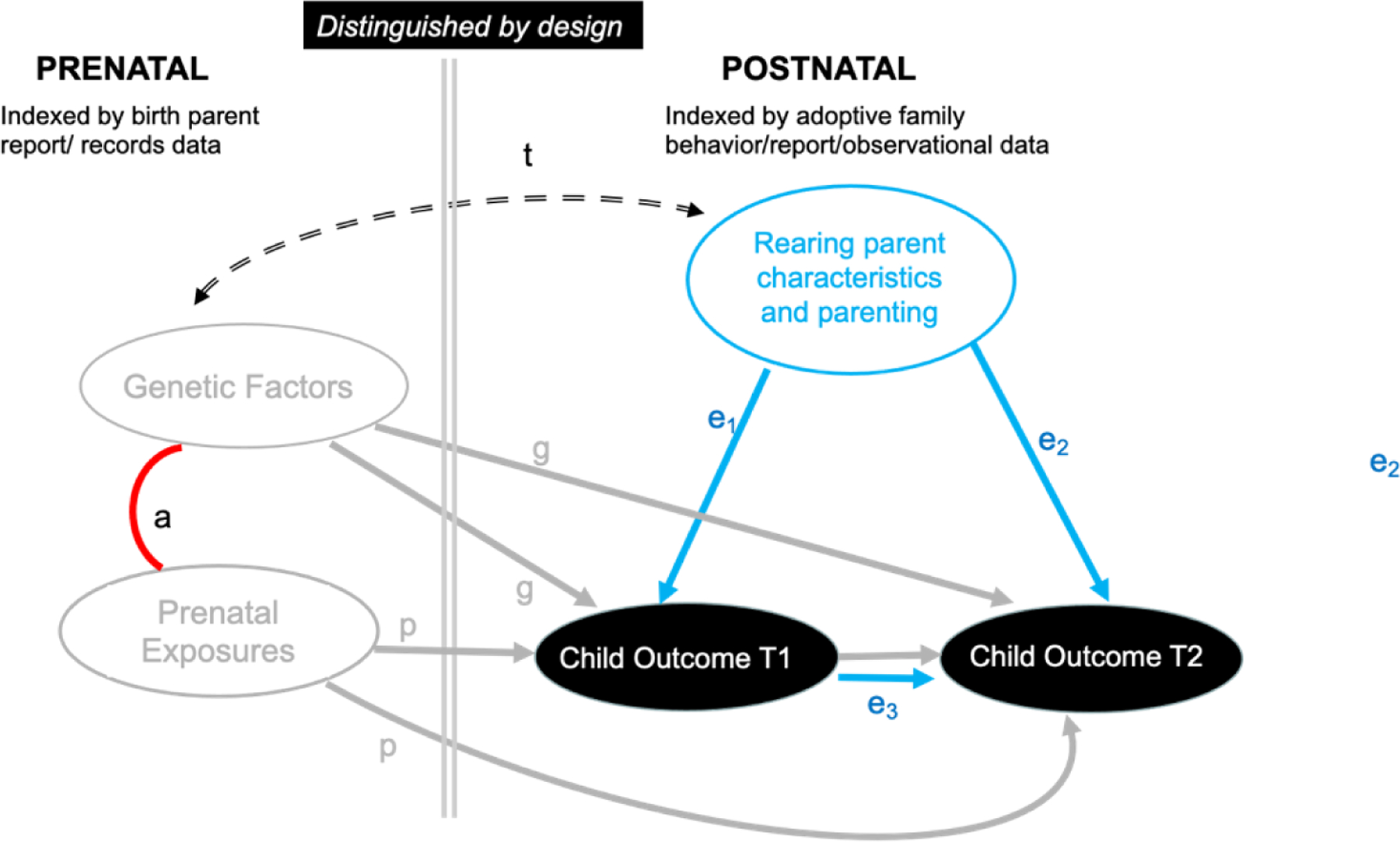

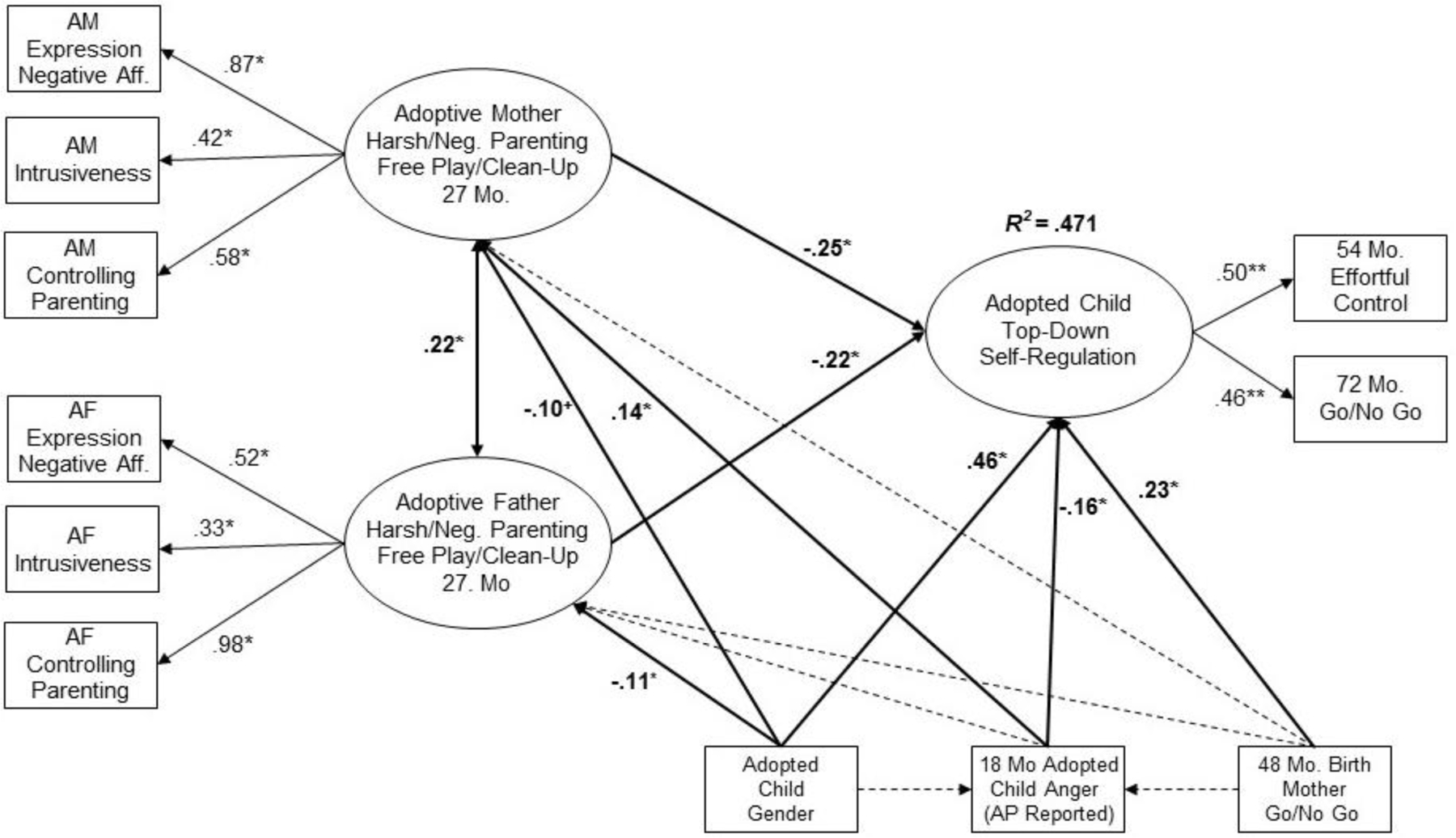

Figure 1B emphasizes the focus of Chapter III in this monograph: the effects of parenting and rearing parent characteristics on child development. In these analyses, we still measure prenatal and genetic influences, but we do so to separately estimate adoptive parenting effects free of the confound of genes shared between biological parent and child and from prenatal environmental influences. Because postnatal environmental influences are the focus of Chapter III, we have greyed out the genetic influences and prenatal pathways in the figure. The path e1 · e3 reflects our analyses aimed at eliminating the effects of reverse causality (e.g., from child to parent, in this instance).

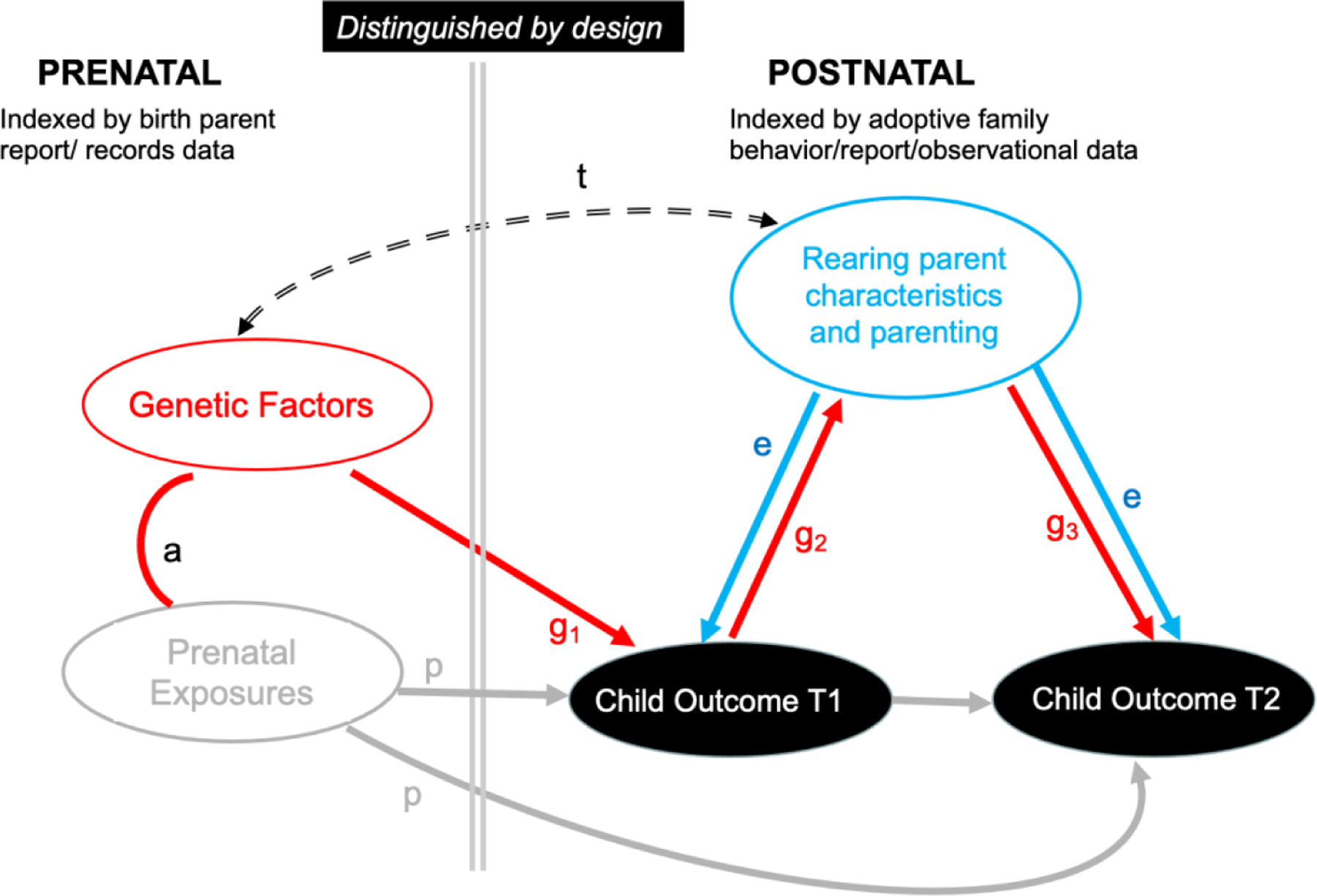

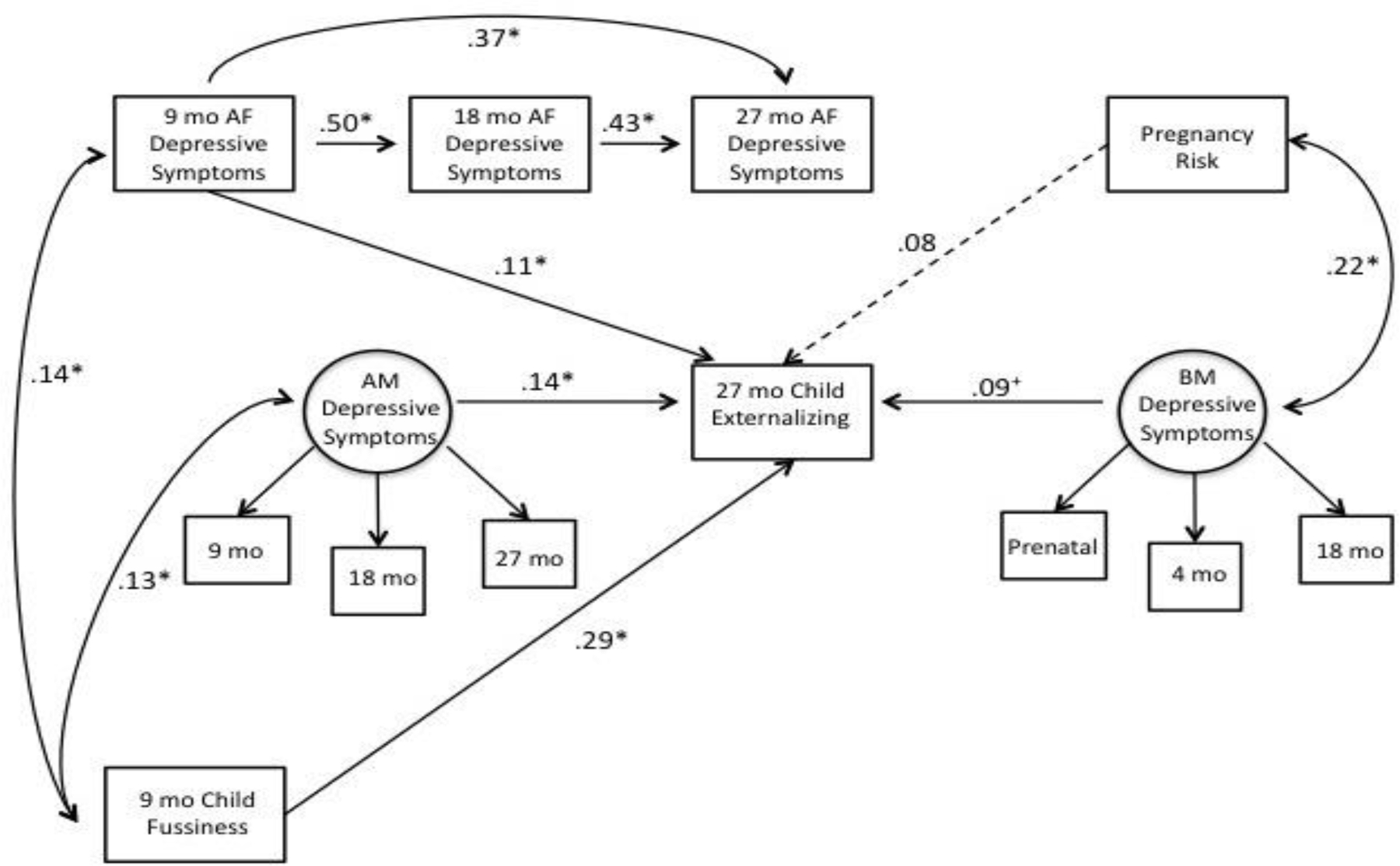

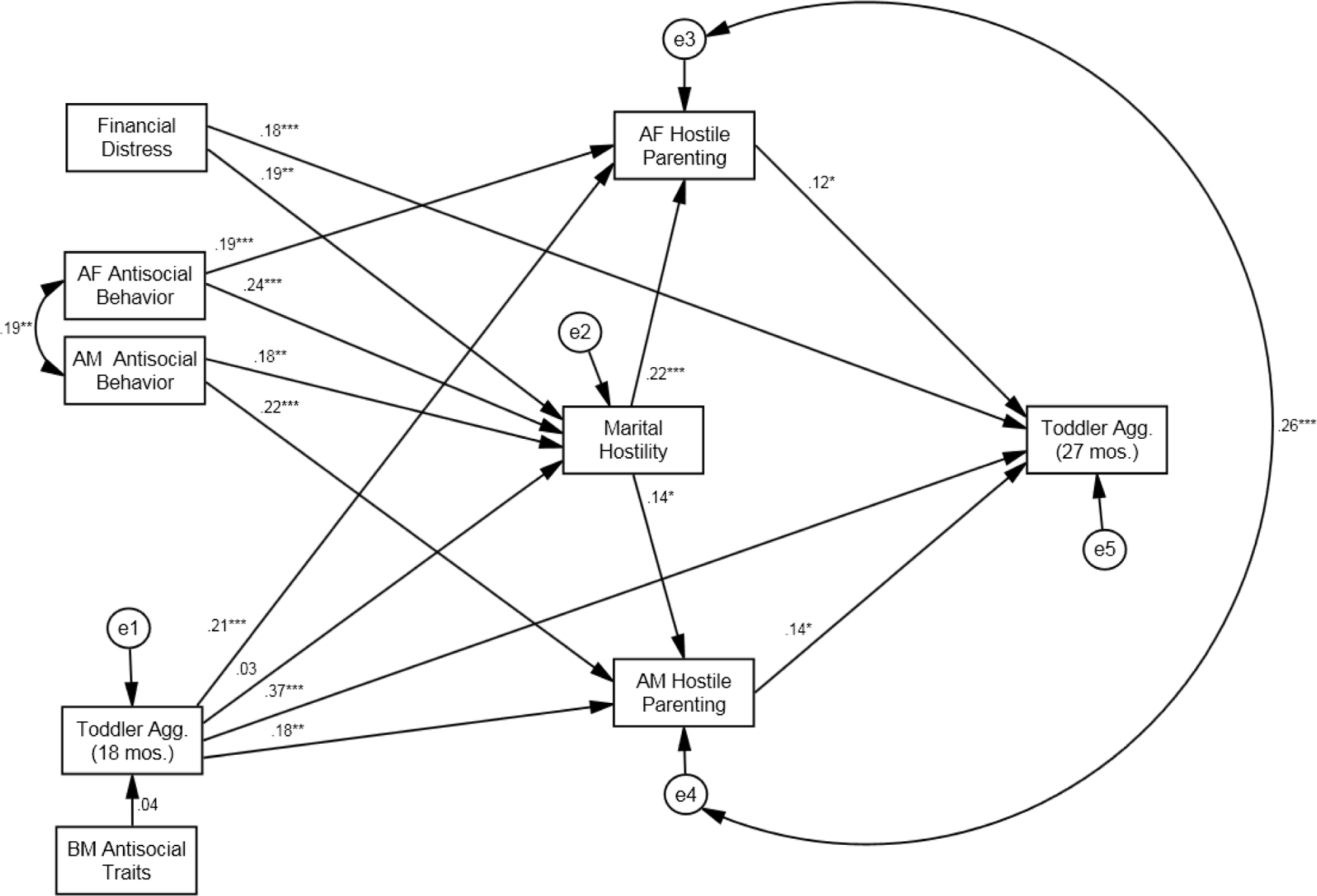

Figure 1C summarizes the aims of Chapter IV: to report findings on genetically influenced child effects on parenting and the family environment. Some of our analyses reported here infer these child effects from associations between birth parent measures and parenting or parent characteristics in the rearing families. As noted earlier in this chapter, our design permits rigorous causal reasoning from these associations because once the adoption design assumptions are met, the only explanation for the association between birth and adoptive parents is via the adopted child. In other words, the only way such associations can be observed is because a genetically influenced characteristic of the child caused a behavior of the rearing parent. Other analyses identify a putative child characteristic that mediates this effect as represented by the path g1 · g2. Of special interest is path g1· g2· g3. This pathway represents those circumstances where a genetically influenced child characteristic evokes parenting behavior that, in turn, augments the child’s characteristic and related behaviors. In this case, the evoked parenting becomes part of the mechanism by which the original genetic influence is expressed (Reiss & Leve, 2007).

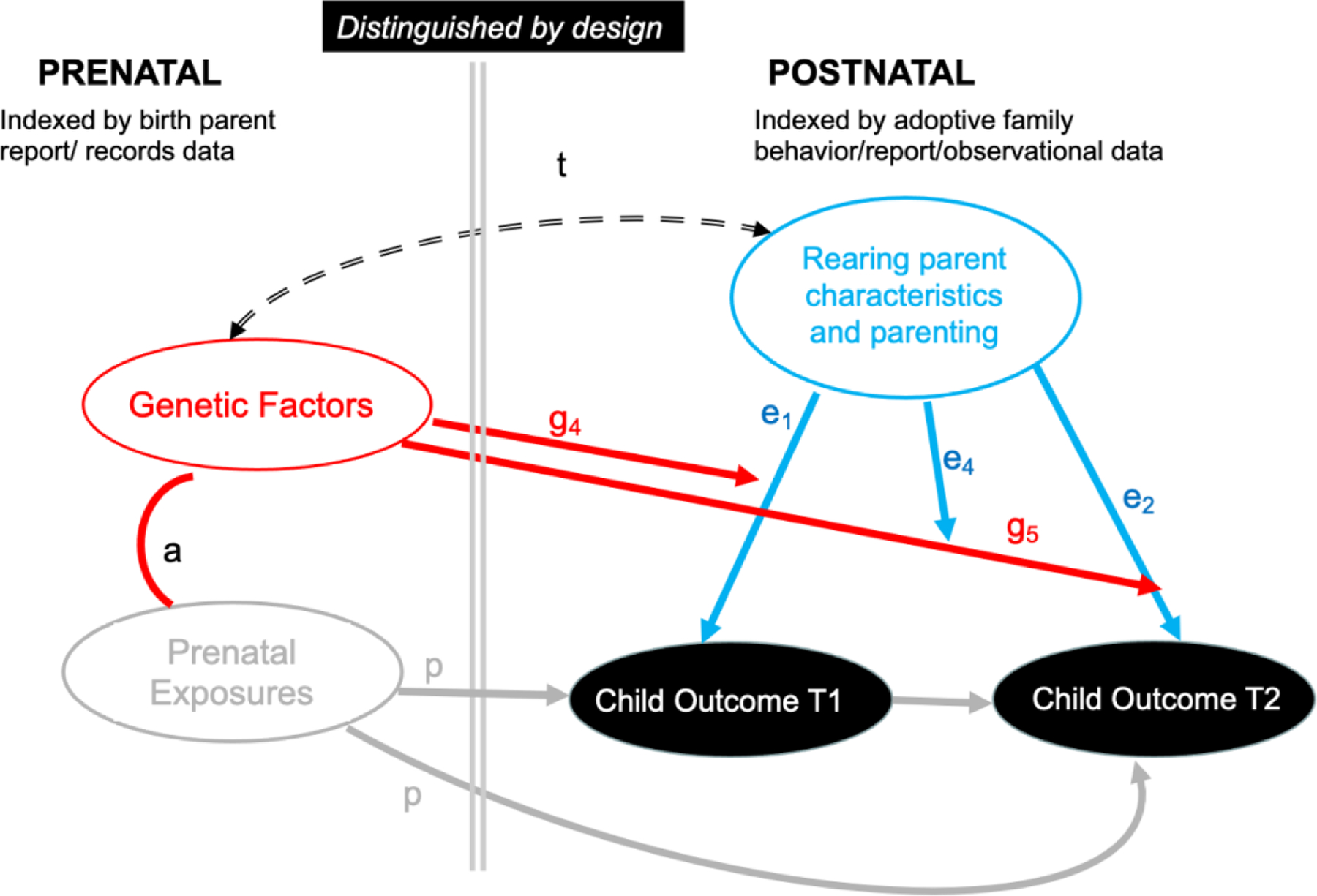

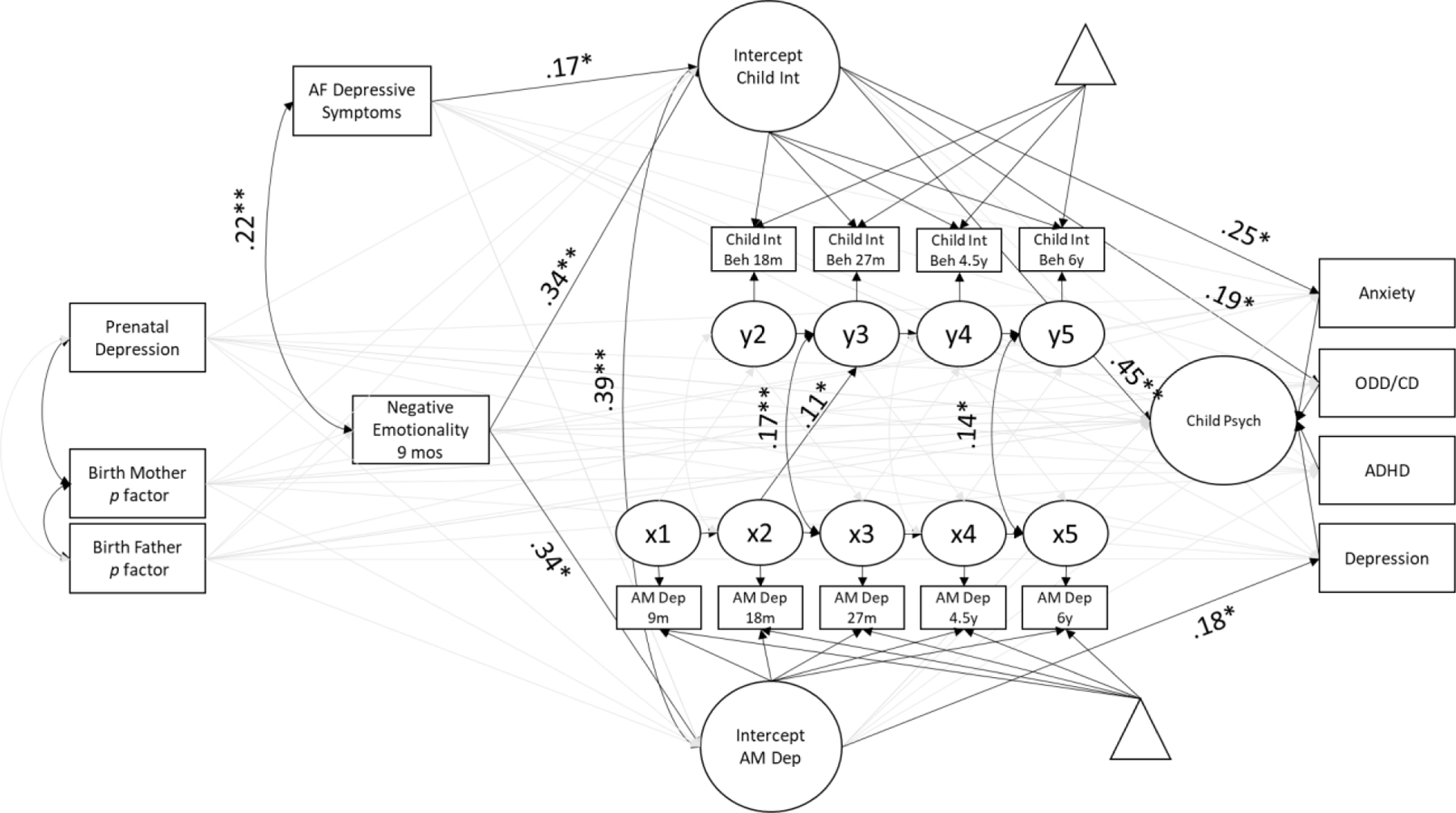

Figure 1D summarizes the findings presented in Chapters V and VI: the moderation of the effects of parenting by a genetically influenced child effect. The moderation is represented by paths g4 and g5. The data used to estimate these paths is the interaction between a birth parent measure and a measure of parenting on a measure of child development. These interactions can be interpreted as either a child effect moderating the impact of parenting on the child (Chapter V) or as a parenting effect moderating the expression of a genetic influence on the child (Chapter VI). This second possibility is represented by the path e4. As the monograph focuses heavily on child effects that influence the dynamics of the family, we give primary emphasis to interpreting these interactions as genetic moderations of parenting. However, Chapter VI includes examples from reports that are best understood as moderating parenting effects on genetic influences on the child.

In Chapters III-VI, we delve more deeply into the schemas presented in Figures 1A – 1D and use them to propose an integrated conceptual schema in Chapter VII. Before doing so, we provide a detailed description of our research design in Chapter II to provide readers an understanding of the measures, assessments, and analytic approaches in EGDS, including a synopsis of the limitations of EGDS adoptive families in terms of their socioeconomic and racial/ethnic diversity.

Chapter II: Design and General Methodology of the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS)

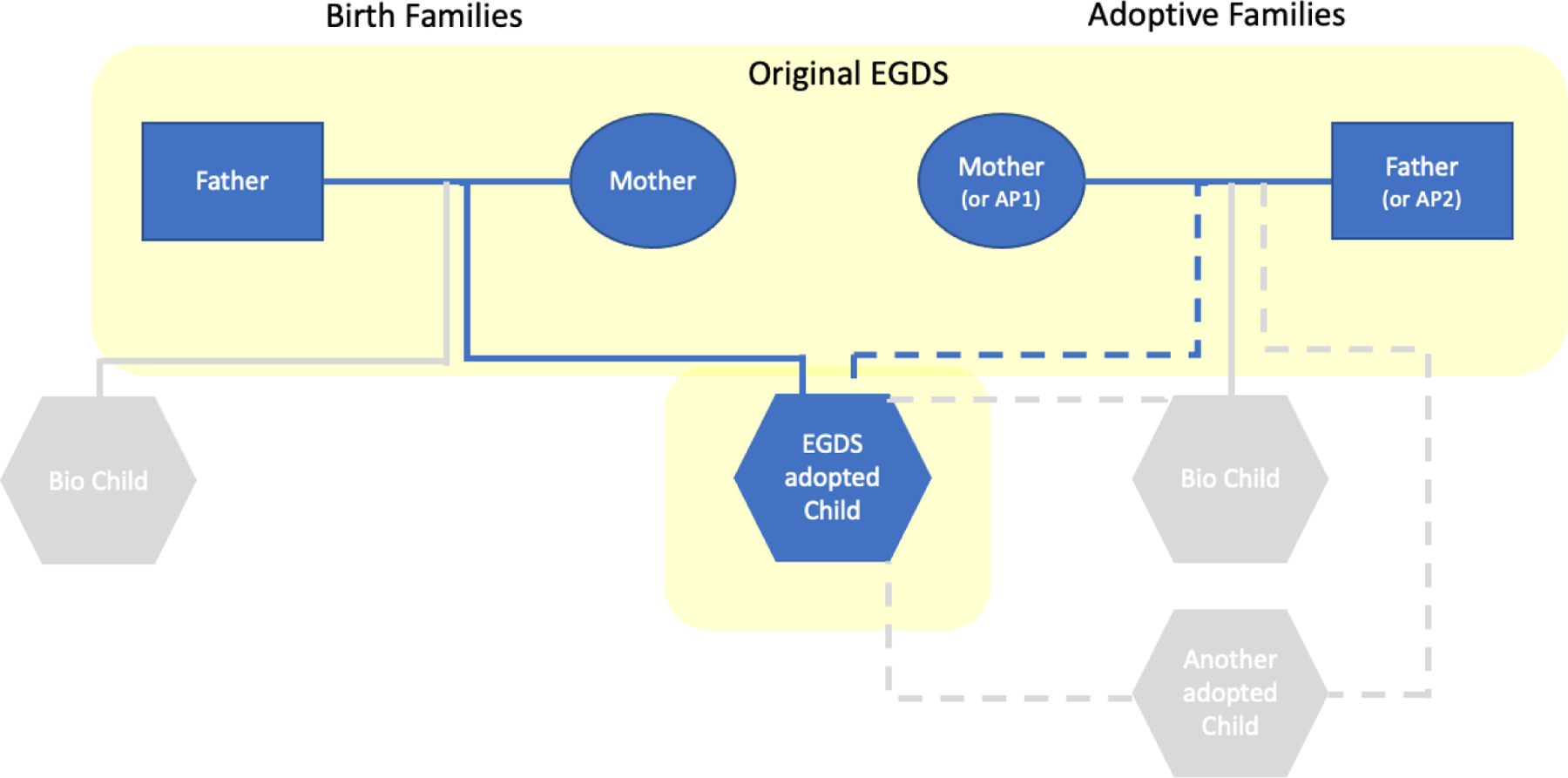

The EGDS is a prospective parent-offspring adoption study of families linked through adoption. In 2002, the EGDS was originally launched to investigate the interplay among genetic, prenatal, and postnatal environmental influences on child development and family functioning in early childhood (see early reports on EGDS; Leve, Neiderhiser, Scaramella, & Reiss, 2010; Leve et al., 2013). An adoption-linked family (or adoption triad) consists of birth parents (birth mothers in all but 5 families, and birth fathers in 37% of adoption-linked families), adoptive parents, and an adopted child (see Figure 2, highlighted in yellow). EGDS has since expanded to include follow-up assessments in middle childhood and adolescence. In addition, two separate but interrelated samples of siblings were added (see Figure 2; Leve et al., 2019): a sample of biological siblings of EGDS adoptees raised in their birth homes (known as the Early Parenting of Children [EPoCh] sample) and any other children living in either the birth or adoptive home (Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes; Gillman & Blaisdell, 2018). In this monograph, the primary focus is on the EGDS adopted children and their adoptive and birth parents (highlighted in yellow in Figure 2). This chapter provides an overview of recruitment, sample, and assessments of the original EGDS adoptive and birth families. These families are the focus of the empirical studies reported in Chapters III through VI. More detailed information about methods for the EGDS extension studies is available in Leve et al. (2019).

Recruitment

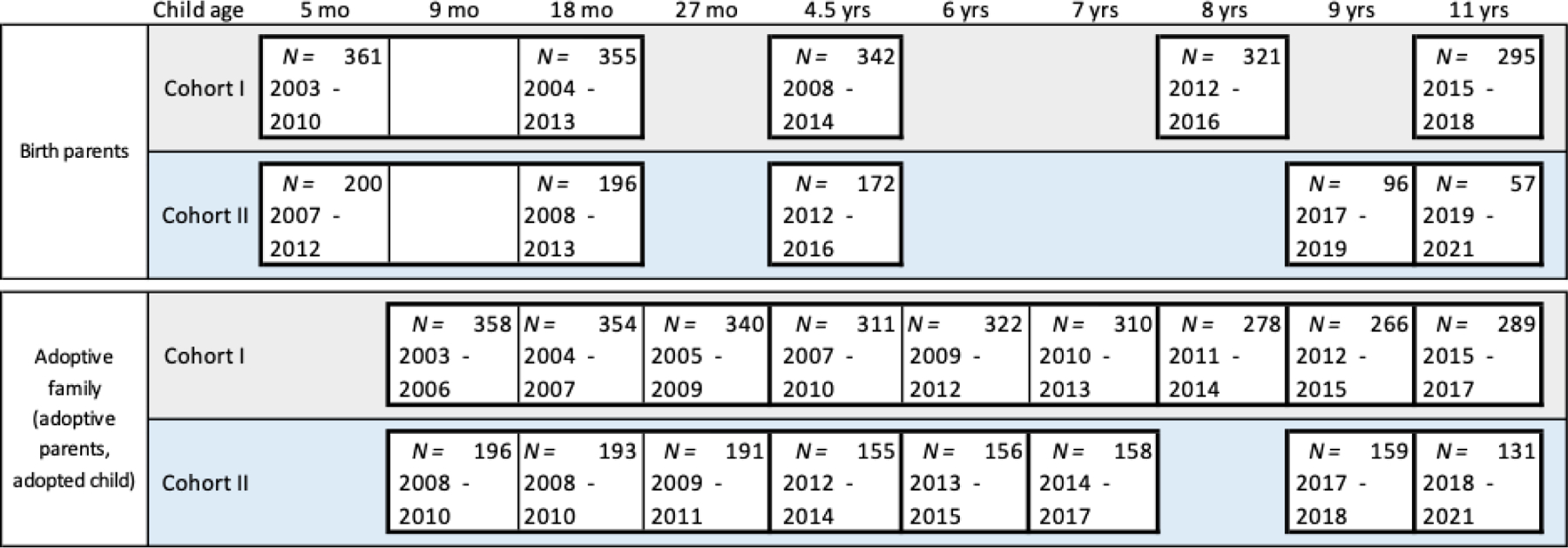

Recruitment of the first EGDS cohort (Cohort I) of adoptees occurred between 2003 and 2006, followed by the recruitment of the second cohort (Cohort II) of adoptees in 2007–2010 (for details see Leve et al., 2019). Similar recruitment and assessment procedures were implemented for both cohorts, with the main differences being that Cohort II recruitment began just after Cohort I recruitment ended (approximately four years after Cohort I recruitment began). To recruit the sample, the EGDS team established multiple research teams in the United States to recruit families in the Mid-Atlantic (George Washington University and The Pennsylvania State University), the West/Southwest (University of California, Davis, and University of California, Riverside), the Midwest (University of Minnesota), and the Pacific Northwest (Oregon Social Learning Center, University of Oregon) regions. The EGDS recruitment began with the recruitment of adoption agencies into the study (N = 45 agencies in 15 states). Once adoption agencies were identified, the adoption agency staff began with outreach to potential participants. Each agency appointed a staff member who served as a liaison between the research team and participants. Liaisons identified potential families who had completed an adoption plan through their agency and met the study eligibility criteria. These criteria included (1) the adoption placement was domestic within the U.S.; (2) the infant adoption occurred within 3 months postpartum; (3) adoptive families were not biologically related relatives of the child; (4) there were no known major medical conditions (e.g., severe prematurity, need for medical surgeries); and (5) both birth and adoptive parents had English proficiency at the eight-grade level. At this first stage of recruitment, a total of 3,293 triads (adopted child, adoptive parents, and birth mother) met the study criteria.

Approximately four weeks after the child was placed in their adoptive home, the agency liaison mailed each eligible adoptive family a letter asking them permission for the EGDS to contact them (N = 2,635). Adoptive families recruited in the EGDS were often composed of two-parent households, although some single-parent families were also recruited (n = 10). Two weeks later, agency liaisons attempted to locate birth mothers whose adoptive families consented to be contacted by the EGDS (N = 1,237 birth mothers located) and called them to obtain their permission for the EGDS staff to contact them. When the birth mother agreed to be contacted by the study (N = 1,098), the liaison provided the contact information of the birth mothers to the EGDS birth parent recruiter.

The birth parent recruiters successfully recruited 864 birth mothers. After a birth mother was recruited, a separate team member was identified to recruit adoptive families linked with birth mothers who agreed to participate. Separate staff members were used to ensure a firewall, such that no information would inadvertently be shared by research staff with one’s counterpart in the adoptive family (also see Chapter I, Table 2, research team bias assumption). The adoptive family recruiter used the contact information provided by the adoption agency to reach the adoptive family. Both adoptive mothers and fathers were recruited. A total of 561 adoptive families (Cohorts I and II combined) agreed to participate, which led to a final sample size of 561 EGDS adoption triads (i.e., each triad consists of an adopted child, adoptive parents, and birth mother and/or birth father). Once the birth mother and adoptive parents were recruited, the EGDS attempted to locate and recruit the birth father. There were five cases across two cohorts where birth fathers were recruited without birth mothers. The recruitment procedures for birth fathers were similar to those used for birth mother recruitment. Although the EGDS staff were only able to recruit and assess birth fathers in 37% of our adoption triad sample (n = 208), this subsample represents the most sizable sample of birth fathers in existing full adoption studies of which we are aware. The most common reasons that birth fathers were not contacted were the inability to locate them and no contact information was available from the birth mother or other sources (Leve et al., 2007). To evaluate possible systematic sampling biases, we gathered demographic information from adoption agencies on eligible participants who did not participate, and then we compared EGDS participants (N = 561 families) and eligible non-participants (N = 2,391 families whose data were available for analysis). Results, reported in Leve et al. (2013), showed no significant differences between EGDS participants and the eligible non-participants, with a few minor exceptions with small effect sizes (d =.13 - .22). Compared to the eligible non-participating counterparts, participating adoptive mothers had higher educational attainment and were slightly younger. Participating adoptive fathers also had higher educational attainment, and participating birth mothers and birth fathers were younger. The primary reason for non-participation of all adult participants was the inability of the project or agency to locate them. These findings suggest that sampling bias was minimal.

Sample Description

The EGDS sample described in this monograph includes 561 adoption-linked families (with n = 361 in Cohort I and n = 200 in Cohort II): 561 adopted children, their birth mothers (n = 554), their birth fathers (n = 210), their adoptive fathers (n = 563), and their adoptive mothers (n = 570). The samples of adoptive mothers and fathers do not add up to 561 each because there are 41 same-sex parent families and additional adoptive fathers and mothers who entered the family after the initial recruitment (n = 14 and 4, respectively), primarily due to marital transitions within the adoptive family. Currently, the EGDS participants reside in 45 states and the District of Columbia in the U.S., as well as 8 other countries.

The demographic information of the family members by role is presented in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the samples of adoptive mothers and fathers were predominantly White with high educational attainment (mode: a 4-year college degree or graduate degree). Both adoptive mother and father samples were older than the birth parent sample (described later), typically in their late 30s. Most adoptive mothers and fathers were married at the outset of the project, and over 85% of them continued to be married 11 years later. As a group, adoptive families were affluent, with the median annual household income at over $100,000 at the start of the project (2002–2010) and $125–150,000 at the latest report provided by the participants (2010–2021).

The birth parent sample is more diverse than the adoptive parent sample: approximately 70% were White (see Table 3 for complete birth parent demographic information). At the start of the project, most birth mothers and fathers were in their 20s with a mode of educational attainment at a high school degree. Few of them were married at the time of placement and their median annual household income was below $25,000. The income differences between adoptive and birth homes we observed in EGDS are typical for adoption studies. As noted in our prior publications (Leve et al., 2013; Natsuaki et al., 2019) and others’ work (McGue et al., 2007; Stoolmiller, 1999), adoptive families have, on average, more financial resources, and higher educational attainment than birth parents. However, the most recent assessment (currently ongoing) shows some changes in birth parents’ life circumstances. Approximately half of the birth parents reported being married, and their median annual household income has grown to $25,000–40,000. The rate of college or university degree holders (2- or 4-year college or graduate degree) has increased from 7.4% at the inception of the study to 25.3% at the latest report for birth mothers and from 6.1% to 15.6% for birth fathers. Through this monograph we discuss limits to the generalizability of our findings that arise from a relatively privileged sample, especially the subsample of rearing parents.

The EGDS adoptee sample of children consists of 57.2% males and approximately 20% of children were identified as multiracial by adoptive parents (see Table 3). The median child age at adoption placement was 2 days (M = 5.58, SD = 11.32).

Timeline of EGDS Assessments and Retention Rates Through Age 11

Figure 3 illustrates the timeline of EGDS assessments and associated sample size by cohorts. The timeline is guided by child age. EGDS conducts adoptive family assessments frequently so that we can follow the child’s development closely. Earlier data collection (at child ages 9, 18, and 27 months) was designed to have shorter intervals between assessments to capture the rapid development in infancy and toddlerhood. After the adopted children entered elementary school, annual assessments were conducted at age 8 or 9, with an additional focus on emerging skills and capacity to fulfill age-relevant developmental tasks, such as academic achievement and school readiness (more information in a later section). Assessments then became biannual (e.g., ages 11, 13, 15). At the time of writing, we have completed the age 11 assessments and fare nearing completion of the age 13 assessment.

Birth parents participated in an intensive data collection at 3 – 6 months postpartum (M age = 5 months postpartum), which was the earliest time point we could contact them after the placement of the child was secure and not subject to recission by the birth parents. In this initial assessment, birth parents provided detailed information about their experiences of adoption. We conducted in-person interviews with them again at 18 months to collect more information about themselves, including their behaviors, emotions, and characteristics. It is also noteworthy that the EGDS assesses birth parents in later waves because phenotypic expression of genes in birth parents may change over time.

One daunting task of prospective, longitudinal studies – especially long-term ones— is to minimize sample attrition. We have been successful at retaining families over time, maintaining a low attrition rate. We estimate the overall retention rate for both cohorts at age 11 to be at 75%. So far, recent work using later waves of data (ages 7 to 11) has shown no evidence of a systematic pattern in missingness (Ganiban et al., 2021; Natsuaki et al., 2021) with a few minor exceptions (e.g., openness was higher for families with missing data Cioffi, Griffin, et al., 2021); the Missing Completely at Random [MCAR] assumption did not hold, but data were consistent with the Missing at Random [MAR] assumption (Austerberry et al., 2021).

Our success at minimizing attrition can be attributed to several strategies we apply to the study protocol. In addition to participation financial incentives, we administer brief (15 minutes) phone interviews or mailed/emailed surveys between extensive in-person interviews. This short interview serves two purposes: to collect updated contact information and maintain rapport with the participants. Families are also asked to provide an additional contact person’s information (e.g., grandparents’), which we use in case direct contact with the participant is lost. In addition, newsletters and birthday cards are sent to families annually. We also use several strategies to locate families who are lost. For instance, we use a “drive-by” option in which our interviewer travels close by to the participant’s last known address by showing up at their home. We send private messages on social media, which has also been an effective way to reconnect with lost families. We offer remote participation options (e.g., online, mail, phone) for families who have moved out of the country or with a busy schedule. We have also adjusted the in-person data collection protocol to a remote-only assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 - current), making study participation more accessible for families. These changes have included data collection by phone, web-based questionnaires, biospecimen collection via mail, and Zoom-based video assessments. Finally, we strive to offer flexible scheduling for interviews whenever we can (e.g., interview location, weekends, evenings). These strategies have been implemented in other long-term longitudinal studies that also found them useful in keeping the retention rate high over the decades of the study course (Ou et al., 2020).

How and What We Measure: The Core Constructs in EGDS

How we measure the core constructs.

The EGDS assessment strategy uses different sources of primary data (i.e., children, mothers, fathers, teachers, and interviewers) and methods (e.g., in-person interviews, diagnostic interviews, questionnaires, diary, observation of family interactions, collection of official records [e.g., GPA, arrest records, neighborhood-level data], medical records, and biological specimens [i.e., DNA from saliva and buccal cells, cortisol via saliva and hair, microbiome via stool samples, and hormone from hair samples]). Consistent with the tradition of multitrait-multimethod measurement (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; Bauer et al., 2013; D. T. Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Kraemer et al., 2003), we have found that each reporter can potentially bring unique insights that are not readily available in other informants’ reports. Additionally, having diverse sources of information allows us to mix and match the reporters in any given analysis to reduce concerns about shared source variance. For instance, we have used adoptive fathers’ reports of parenting as a predictor of child behavior as reported by adoptive mothers. This difference-of-reporter design has been used in many of our publications (e.g., Leve et al., 2009; Natsuaki et al., 2010).

What we measure as our core constructs.

Table 4 provides an overview of the core constructs that EGDS assesses. Influenced by the overarching theories of development by Gottlieb (1991), Sameroff (2010), and Cicchetti & Dawson (2002), we continue to emphasize assessment at multiple levels of analysis for each family member, from genes, neuroendocrine systems, phenotypic characteristics to the environment (within and outside the family). Broadly speaking, the constructs assessed in EGDS fall into four categories: genetic influences, prenatal environment, rearing environment, and potential confounds.

Genetic influences (highlighted in gray in Table 4).