Abstract

Introduction

To investigate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) of tirzepatide in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

In this phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple dose study, patients were randomized into one of two cohorts to receive once-weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide or placebo. The initial tirzepatide dose in both cohorts was 2.5 mg, which was increased by 2.5 mg every 4 weeks to a maximum final dose of 10.0 mg at week 16 (Cohort 1) or 15.0 mg at week 24 (Cohort 2). The primary outcome was the safety and tolerability of tirzepatide.

Results

Twenty-four patients were randomized (tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg: n = 10, tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg: n = 10, placebo: n = 4); 22 completed the study. The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) among patients receiving tirzepatide were diarrhea and decreased appetite; most TEAEs were mild and resolved spontaneously with no serious adverse events reported in the tirzepatide groups and one in the placebo group. The plasma concentration half-life of tirzepatide was approximately 5–6 days. Mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) decreased over time from baseline in the 2.5–10.0 mg (− 2.4%) and 2.5–15.0 mg (− 1.6%) tirzepatide groups, at week 16 and week 24, respectively, but remained steady in patients receiving placebo. Body weight decreased from baseline by − 4.2 kg at week 16 in the tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg group and by − 6.7 kg at week 24 in the 2.5–15.0 mg group. Mean fasting plasma glucose levels fell from baseline by − 4.6 mmol/L in the tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg group at week 16 and by − 3.7 mmol/L at week 24 in the tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg group.

Conclusions

Tirzepatide was well tolerated in this population of Chinese patients with T2D. The safety, tolerability, PK, and PD profile of tirzepatide support once-weekly dosing in this population.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04235959.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02536-8.

Keywords: GIP, GLP-1, Phase 1, Pharmacodynamics, Pharmacokinetics, Tirzepatide, Type 2 diabetes

Key Summary Points

| An estimated 140.9 million people in China were living with diabetes in 2021, with only around 50% able to achieve glycemic control, indicating a need for the further development of safe and effective therapies. |

| This study aimed to investigate the safety and tolerability of tirzepatide, a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). |

| Most treatment-emergent adverse events were mild, the most frequently reported were diarrhea and decreased appetite, and the tirzepatide plasma half-life was 5-6 days. |

| The safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of tirzepatide observed in this study support once-weekly dosing in Chinese patients with T2D. |

Introduction

China accounts for approximately one-quarter of global adult cases of diabetes. Indeed, an estimated 140.9 million people in China were living with diabetes in 2021, and this number is expected to rise to 174.4 million by 2045 [1]. Despite the favorable effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs)[2] and other medications in the treatment of diabetes, only around 50% of Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are able to achieve their therapeutic goals of glycemic control, defined as glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of less than 7.0% [3], which demonstrates an urgent need for new approaches to manage hyperglycemia in Chinese people with T2D.

Tirzepatide is a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonist developed for the treatment of adults with T2D as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, which has profound efficacy for reducing HbA1c [4–10]. In addition to the effect of GLP-1 on controlling glycemia and regulating appetite, GIP plays a central role in glycemic control by increasing postprandial glucose-dependent insulin secretion and mediating the majority of the incretin effect in healthy people [11, 12]. A study exploring the physiological mechanisms underlying tirzepatide in the treatment of T2D showed that, compared to the GLP-1RA semaglutide, tirzepatide significantly improves both insulin secretion rates and insulin sensitivity, which indicates synergistic anti-hyperglycemic efficacy as an agonist of both the GLP-1 and GIP receptors [13].

In both healthy individuals and patients with T2D included in global and Japanese pharmacokinetic (PK) studies, tirzepatide has shown a dose-proportional PK profile with peak concentrations 1–2 days after dosing and a plasma half-life (T½) of around 5 days, across a range of single and multiple dose levels on a once-weekly dosing schedule [14, 15]. However, the PK and pharmacodynamic (PD) characteristics of tirzepatide have not been established in Chinese patients with T2D.

Here, we present the results of a phase 1 study that evaluated the safety, tolerability, PK, and PD of tirzepatide in Chinese patients with T2D.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple dose phase 1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04235959). Eligible patients were native Chinese adults (20–70 years, inclusive) with T2D either controlled through diet and exercise alone or stable for ≥ 3 months on treatment with a single oral antihyperglycemic medication (OAM; metformin, acarbose, or sulphonylurea only) prior to screening. Other enrolment criteria included HbA1c ≥ 7.0% and ≤ 10.5% (patients treated with diet and exercise alone) or ≥ 6.5% and ≤ 10.0% (patients receiving an OAM), and BMI ≥ 23.0 kg/m2. Key exclusion criteria were aspartate aminotransferase or alanine transaminase levels > 2× the upper limit of normal (ULN), total bilirubin level > 1.5× ULN, or estimated glomerular filtration rate < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 at screening and female subjects of childbearing potential were required to test negative for pregnancy before inclusion.

The study protocol was approved by Peking University First Hospital Ethics Committee and the Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials, West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The study was conducted in accordance with principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council of International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines. All participants gave written informed consent before participation in the study.

Procedures

The details of the study design are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. All prior OAM treatments were discontinued and washed out during the 2-week lead-in period before dosing. Enrolled patients were randomized in a 5:1 ratio to receive either tirzepatide or matched placebo by once-weekly (QW) subcutaneous (SC) injection in one of two cohorts: in Cohort 1 (2.5–10.0 mg), patients assigned to tirzepatide received 2.5 mg for the first 4 weeks, with the dose increasing by a further 2.5 mg every 4 weeks, to the maximum dose of 10.0 mg; in Cohort 2 (2.5–15.0 mg), patients receiving tirzepatide followed the same dose increments as Cohort 1, but with two further dose increases to the maximum dose of 15.0 mg. After the treatment period, all patients were followed up for 4 weeks.

Randomization was implemented using a computer-generated randomization sequence via an interactive web response system. All study treatments were provided in a single-dose pen injector and were dispensed by the investigator. Tirzepatide and placebo were provided in identical pen injectors with identical packaging to facilitate masking. The patients and investigators, as well as site staff and clinical monitors, were blinded to treatment allocation.

The study procedures, including safety assessments and blood sampling, were performed as scheduled in the protocol. Details of the measurement of tirzepatide plasma concentration are provided in the Supplementary Information. PD samples including HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) were tested in a designated central laboratory (Labcorp, Shanghai, China).

Assessments

The primary study outcome was to investigate the safety and tolerability of tirzepatide in Chinese patients with T2D after multiple SC doses. Information on each adverse event (AE) and serious AE (SAE) was recorded via an electronic case report form, which also required the investigator to assess any possible relationship between the AE and the study treatment. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were defined as AEs that occurred or increased in severity following initiation of treatment. Other safety data gathered included laboratory investigations, vital signs, electrocardiogram, information on injection-site reactions, and hypoglycemic events. Hypoglycemia was defined as plasma or serum glucose ≤ 70.0 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), and was categorized and reported as mild, moderate, or severe on the basis of recommendations of the International Hypoglycaemia Study Group [16]. The secondary outcome was the PK profile of tirzepatide. The primary PK parameters evaluated included maximum drug concentration (Cmax), area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) and time to Cmax (Tmax).

The following PD measurements were included in this study as exploratory endpoints: changes from baseline in lipid profiles, meal intake, patient-reported appetite sensation, body weight, FPG, HbA1c, 7-point self-monitored blood glucose (7-point SMBG), and immunogenicity assessments. For the immunogenicity assessments, the frequency and percentage of patients with pre-existing and treatment-emergent anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) were recorded. A treatment-induced ADA was defined as a titer twofold/1-dilution greater than the minimum required dilution when no ADAs were detected at baseline. A treatment-boosted ADA was defined as a fourfold/2-dilution increase in titer versus baseline if ADAs were detected at baseline.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was selected to enable evaluation of the primary study objective without consideration of a priori statistical requirements. The protocol specified a sample size of approximately 24 patients, with the expectation that 16 would complete the study in compliance with the specified dosing regimen. Safety analyses included data from all enrolled patients, and PK and PD analyses included data from all patients who received at least one dose of study treatment and for whom evaluable data were available.

Results

Patients

A total of 24 patients were enrolled in the study: placebo, n = 4 (two placebo patients in each cohort); tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg, n = 10; tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg, n = 10. Of the 24 enrolled patients, 22 completed the study. One patient in the tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg group was discontinued after the first 4 weeks’ treatment with tirzepatide 2.5 mg due to inadvertent enrollment with an excluded pre-existing medical condition (cholecystolithiasis). Another patient, who received placebo in cohort 2, was discontinued at week 19 (Day 131) due to an SAE of acute myocardial infarction. This was the only SAE reported in this study.

Approximately half of the patients were male (54%); the mean [standard deviation (SD)] age was 56.3 (5.4) years; body weight was 67.1 (7.6) kg; BMI was 25.7 (2.3) kg/m2; HbA1c was 7.9 (1.1) %; and duration of diabetes was 6.4 (3.7) years (Table 1). Baseline characteristics were broadly similar across the treatment groups, although body weight and BMI were slightly higher in the placebo-treated patients and HbA1c was higher in those receiving tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg than in the other groups.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

| Placebo (n = 4) | Tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg (n = 10) | Tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg (n = 10) | Total (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 56.5 (7.5) | 55.8 (5.2) | 56.8 (5.4) | 56.3 (5.4) |

| Range | 50.0–63.0 | 50.0–65.0 | 50.0–66.0 | 50.0–66.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 3 (75) | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 13 (54) |

| Female | 1 (25) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 11 (46) |

| Weight, kg | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 71.3 (7.1) | 65.0 (8.5) | 67.6 (6.8) | 67.1 (7.6) |

| Range | 64.8–81.0 | 51.5–77.1 | 57.6–77.0 | 51.5–81.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.4 (1.8) | 26.0 (2.9) | 25.1 (1.6) | 25.7 (2.3) |

| Range | 24.2–28.4 | 23.2–31.2 | 23.1–27.9 | 23.1–31.2 |

| HbA1c concentration, %a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (0.7) | 8.2 (1.2) | 7.7 (1.1) | 7.9 (1.1) |

| Range | 7.4–8.9 | 6.6–10.7 | 6.8–10.3 | 6.6–10.7 |

| Duration of T2D, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.1) | 6.6 (4.1) | 6.6 (4.0) | 6.4 (3.7) |

| Range | 3.0–8.0 | 2.0–12.0 | 2.0–12.0 | 2.0–12.0 |

| Prior OAM, n (%) | ||||

| None | 1 (25) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 3 (13) |

| Acarbose | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Metformin | 3 (75) | 7 (70) | 9 (90) | 19 (79) |

BMI body mass index, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, OAM oral antidiabetic medication, SD standard deviation, T2D type 2 diabetes

aHbA1c values were collected at study day 1, pre-dose

Safety and Tolerability

No deaths or SAEs occurred in patients receiving tirzepatide during the study. At least one treatment-related AE was reported in almost all patients receiving tirzepatide (Table 2), although treatment was well tolerated, with no AEs leading to discontinuation. Overall, at least one TEAE was reported in each patient, of which 93% were rated as mild and 95% had resolved by the end of the study without requiring treatment. Although most TEAEs were related to the gastrointestinal system, with diarrhea and decreased appetite being the most common, the majority were rated as mild, and all had resolved by the end of the study without requiring treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| Placebo (n = 4) | Tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg (n = 10) | Tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Mild | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Moderate | 1 (25) | 3 (30) | 0 |

| Treatment-related AEs | 0 | 9 (90) | 10 (100) |

| Any SAE | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinuation due to AEs | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs by preferred terma | |||

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 5 (50) | 8 (80) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 6 (60) | 4 (40) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (75) | 5 (50) | 2 (20) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 2 (20) | 5 (50) |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 (10) | 4 (40) |

| Lipase increased | 0 | 1 (10) | 3 (30) |

| Hiccups | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Flatulence | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Hypoglycemia | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (25) | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Injection-site reaction | 0 | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 0 | 0 | 2 (20) |

| URTI | 2 (50) | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

Data are presented as number of patients (%)

aListings include any TEAE reported in ≥ 2 patients

AE adverse event, SAE serious adverse event, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, URTI upper respiratory tract infection

The incidence of hypoglycemia was low, occurring in one patient in each tirzepatide group, both at a dose of 10 mg. These two events were mild (58 mg/dL and 64 mg/dL) and resolved within 3 h. Injection-site reactions were reported in two patients, all of which were mild and resolved spontaneously. One hypersensitivity-related event (mild rash) was reported by a patient in the tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg group; the event occurred 48 h after the first dose of 7.5 mg, was considered to be related to study drug, and resolved spontaneously within 5 days. No clinically meaningful changes in vital signs measurements were reported during the study.

Pharmacokinetics

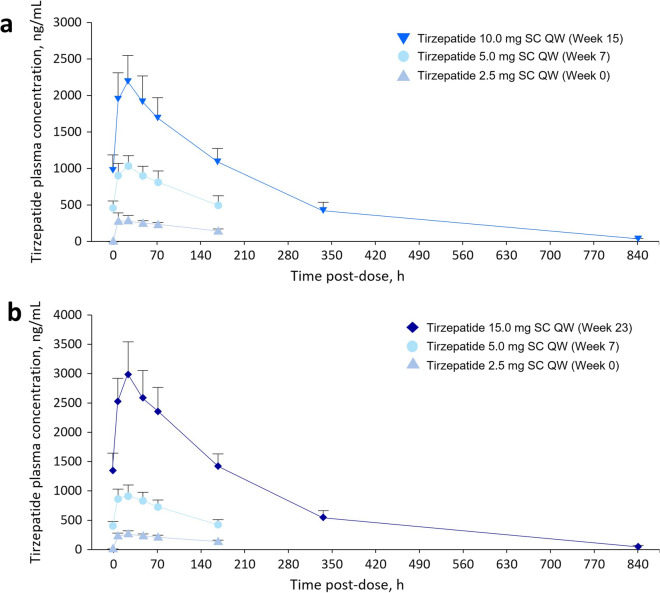

Complete PK data were available for all patients who received tirzepatide, apart from the patient from Cohort 1 who was discontinued after the first 4 weeks’ tirzepatide treatment because of a pre-existing medical condition. For this patient, only the Week 0 data were included in the PK analysis. Figure 1a and b shows the mean plasma tirzepatide concentration–time profiles up to week 15 for the 2.5–10.0 mg group and up to week 23 for the 2.5–15.0 mg group, respectively. The Cmax values were dose-dependent and the mean Tmax values were similar over time and between cohorts, with Tmax consistently being approximately 24 h (Supplementary Table S1). Values of T½ were also relatively consistent, ranging from 124 to 145 h (approximately 5–6 days), regardless of whether they were calculated over a period of less than or greater than the resultant T½.

Fig. 1.

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles for tirzepatide in Cohort 1 (a) and Cohort 2 (b). Error bars represent standard deviation. SC subcutaneous, QW once weekly

Pharmacodynamics

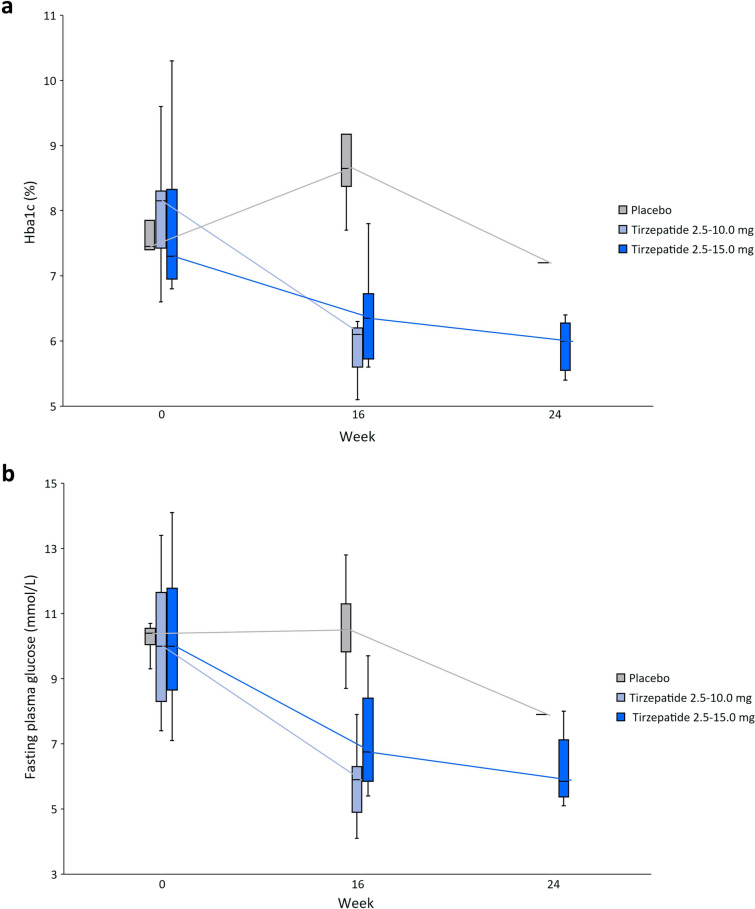

Median HbA1c decreased over time with tirzepatide treatment but remained approximately stable in patients receiving placebo (Fig. 2a). The mean changes from baseline in HbA1c were − 2.4% at week 16 in the tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg group and − 1.6% at week 24 in the tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg group (Supplementary Table S2). Over the course of the study, FPG decreased from baseline with tirzepatide treatment, but not with placebo: the mean changes from baseline were − 4.6 mmol/L [− 82.8 mg/dL] at week 16 in the tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg group and − 3.7 mmol/L [− 66.2 mg/dL] at week 24 in the tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg group (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Median HbA1c at weeks 0, 16 and 24; b Median FPG at weeks 0, 16 and 24. Data are shown as median (horizontal line), Q1 and Q3 (box upper and lower edges) and minimum and maximum values (ends of whiskers). FPG fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin

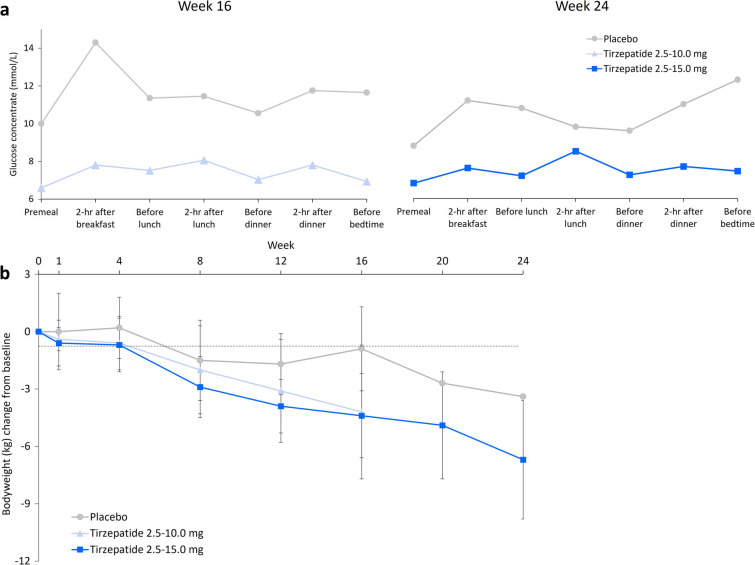

In the tirzepatide groups, mean 7-point SMBG decreased at all timepoints from baseline to study end [tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg: − 7.0 mmol/L (− 126.0 mg/dL) at week 16; tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg: − 4.5 mmol/L (− 80.6 mg/dL) at week 24]. No such consistent decrease from baseline was seen in the placebo group (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

a Mean 7-point SMBG at week 16 and 24; b Mean change from baseline in body weight (error bars represent standard deviation, not calculated for the placebo group at week 20 or 24). SMBG 7-point self-monitored blood glucose

There was a trend towards a decrease in meal intake between baseline and end of study in both the tirzepatide groups. This trend was not apparent in the placebo group (Supplementary Figure S2). Furthermore, mean body weight decrease from baseline was numerically greater in patients treated with tirzepatide than in those receiving placebo: tirzepatide 2.5–10.0 mg: − 4.2 kg at week 16; tirzepatide 2.5–15.0 mg: − 6.7 kg at week 24, compared with − 0.9 kg and − 3.4 kg for patients receiving placebo at the same time points (Fig. 3b).

Immunogenicity

No ADAs were detected at baseline. Post-baseline, evaluable data were available for all 20 patients treated with tirzepatide. Eight (40%) were ADA-positive; five patients in the 2.5–10.0 mg group and three in the 2.5–15.0 mg group. All positive cases were classified as treatment-induced, with maximum titers ranging from 1:20 to 1:320 (median 1:40). There was no apparent impact of ADA-positive status on the safety, PK and PD of tirzepatide.

Discussion

This phase 1 multiple-ascending dose study provides the primary safety and PK data for tirzepatide in the Chinese population. The results demonstrated that once-weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide is well tolerated at the studied doses in Chinese patients with T2D. Furthermore, the safety, and PK and PD profiles, of tirzepatide in Chinese patients were consistent with those previously reported in global and other Asian populations [4–10, 15], which provided evidence that tirzepatide can potentially provide improvements in glycemic control and reduce body weight in patients with T2D.

In this study, the most frequently reported TEAEs were gastrointestinal-related events (diarrhea and decreased appetite), almost all of which were mild in severity. This is consistent with the findings of the SURPASS clinical trial program and the known safety profile of GLP-1 RAs, for which gastrointestinal events are also the most common side effect [14–19]. The incidence of hypoglycemia in the present study was low (one event in each tirzepatide group), and both events were mild and resolved rapidly (within 3 h). This finding is consistent with the results of the SURPASS clinical trial program and a meta-analysis of the SURPASS trials which found a similar incidence of hypoglycemia with tirzepatide versus placebo and a low incidence of severe hypoglycemia [14–20]. Injection-site reactions and hypersensitivity-related events were also rare and mild, all resolving spontaneously. Overall, no new safety concerns were identified in Chinese patients with T2D compared with previous reports in global and Asian populations [14–19].

The PK profile of tirzepatide in Chinese patients with T2D observed in the present study was comparable to that reported in global and Japanese patient populations, with dose-proportional PK reported in all studies [14, 15]. Across a range of single and multiple tirzepatide doses, broadly comparable values of median Tmax (global and Japan, Tmax range of 24–48 h; China: 24 h) and mean T½ (global and Japan: ~ 5 days; China: 5–6 days) were observed. In summary, these data support a once-weekly dosing schedule for tirzepatide in Chinese patients with T2D.

The present study found that, compared with placebo, tirzepatide led to numerically greater changes from baseline in body weight and improvements in glycemic control. These results are consistent with the findings of early-stage studies in global and Japanese populations, and have since been confirmed in larger phase 3 studies.[15, 18–20] Interestingly, a dose-dependent glucose lowering effect was not observed in the present study. At the end of treatment, the mean changes from baseline HbA1c were − 2.4% and − 1.6% in the 2.5–10.0 mg and 2.5–15.0 mg treatment groups, respectively. However, this is likely due to the moderate disparity of HbA1c at baseline (8.2% in the 2.5–10 mg group and 7.7% in the 2.5–15 mg group; Table 1).

The primary limitations of this study were the small sample size and limited treatment duration, inherent to most phase 1 trials. The safety, tolerability, and PK and PD profiles of tirzepatide support once-weekly dosing in this population. The efficacy and safety of long-term tirzepatide treatment in Chinese patients with T2D will be evaluated further in the on-going clinical development program.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study revealed that the treatment of Chinese patients with T2D with tirzepatide yields a PK/PD profile consistent with that reported in previous studies, with efficacy for glycemic control and body weight reduction, as well as a favorable safety profile. These results provide a foundation for the further clinical development of tirzepatide in the Chinese population. Two phase 3 studies are currently being conducted to investigate tirzepatide for the treatment of T2D (SUPASS-AP; NCT04093752) and for chronic weight management (SURMOUNT-CN; NCT05024032), respectively, in Chinese patient populations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study and the study personnel.

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The study sponsor also funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Steve Smith on behalf of Rude Health Consulting and Jake Burrell PhD (Rude Health Consulting) and was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

Ping Feng, Xiaoyan Sheng, Yongjia Ji, Shweta Urva, Feng Wang, Sheila Miller, Chenxi Qian, Zhenmei An, and Yimin Cui provided substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; provided final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Prior Presentation

Partial results of this manuscript were presented as an e-Poster at the International Diabetes Federation Congress 2022 (5–8 December 2022).

Disclosures

Yongjia Ji, Shweta Urva, Feng Wang, Sheila Miller, and Chenxi Qian are employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study protocol was approved by Peking University First Hospital Ethics Committee (approval reference: 2020药物注册019 approval date: 2020/06/01) and the Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials, West China Hospital of Sichuan University (approval reference: 2020年临床试验(西药)审(183)号; approval date: 2020/10/21). The study was conducted in accordance with principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council of International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines. All participants gave written informed consent before participation in the study.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data access should comply with local laws and regulations. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Footnotes

Ping Feng and Xiaoyan Sheng are joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Zhenmei An, Email: 848948343@qq.com.

Yimin Cui, Email: cui.pharm@pkufh.com.

References

- 1.IInternational Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edn. Brussels Belgium, 2021. Available at: https://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed Feb 2023.

- 2.Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes-state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101102. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Peng W, Zhao Z, Zhang M, Shi Z, Song Z, et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 2013–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2498–2506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahl D, Onishi Y, Norwood P, Huh R, Bray R, Patel H, et al. Effect of subcutaneous tirzepatide vs placebo added to titrated insulin glargine on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: the SURPASS-5 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(6):534–545. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Prato S, Kahn SE, Pavo I, Weerakkody GJ, Yang Z, Doupis J, et al. Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10313):1811–1824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, Pérez Manghi FC, Fernández Landó L, Bergman BK, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503–515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludvik B, Giorgino F, Jódar E, Frias JP, Fernández Landó L, Brown K, et al. Once-weekly tirzepatide versus once-daily insulin degludec as add-on to metformin with or without SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10300):583–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenstock J, Wysham C, Frías JP, Kaneko S, Lee CJ, Fernández Landó L, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):143–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inagaki N, Takeuchi M, Oura T, Imaoka T, Seino Y. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide monotherapy compared with dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS J-mono): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(9):623–633. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadowaki T, Chin R, Ozeki A, Imaoka T, Ogawa Y. Safety and efficacy of tirzepatide as an add-on to single oral antihyperglycaemic medication in patients with type 2 diabetes in Japan (SURPASS J-combo): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(9):634–644. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasbjerg LS, Bergmann NC, Stensen S, Christensen MB, Rosenkilde MM, Holst JJ, et al. Evaluation of the incretin effect in humans using GIP and GLP-1 receptor antagonists. Peptides. 2020;125:170183. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2019.170183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor co-agonists for treating metabolic disease. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101090. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heise T, Mari A, DeVries JH, Urva S, Li J, Pratt EJ, et al. Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(6):418–429. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coskun T, Sloop KW, Loghin C, Alsina-Fernandez J, Urva S, Bokvist KB, et al. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol Metab. 2018;18:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furihata K, Mimura H, Urva S, Oura T, Ohwaki K, Imaoka T. A phase 1 multiple-ascending dose study of tirzepatide in Japanese participants with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(2):239–246. doi: 10.1111/dom.14572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Hypoglycaemia Study Group Glucose concentrations of less than 30 mmol/l (54 mg/dl) should be reported in clinical trials: a joint position statement of the American diabetes association and the European association for the study of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):155–157. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aroda VR. A review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: evolution and advancement, through the lens of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(Suppl 1):22–33. doi: 10.1111/dom.13162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, Benson C, Bray R, Cui X, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tirzepatide, a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate different dose-escalation regimens. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(6):938–946. doi: 10.1111/dom.13979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, Kutner ME, Cui X, Benson C, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2180–2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karagiannis T, Avgerinos I, Liakos A, Del Prato S, Matthews DR, Tsapas A, et al. Management of type 2 diabetes with the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2022;65(8):1251–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data access should comply with local laws and regulations. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.