Abstract

Background

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are ubiquitous, environmentally persistent chemicals, and prenatal exposures have been associated with adverse child health outcomes. Prenatal PFAS exposure may lead to epigenetic age acceleration (EAA), defined as the discrepancy between an individual’s chronologic and epigenetic or biological age.

Objectives

We estimated associations of maternal serum PFAS concentrations with EAA in umbilical cord blood DNA methylation using linear regression, and a multivariable exposure-response function of the PFAS mixture using Bayesian kernel machine regression.

Methods

Five PFAS were quantified in maternal serum (median: 27 weeks of gestation) among 577 mother-infant dyads from a prospective cohort. Cord blood DNA methylation data were assessed with the Illumina HumanMethylation450 array. EAA was calculated as the residuals from regressing gestational age on epigenetic age, calculated using a cord-blood specific epigenetic clock. Linear regression tested for associations between each maternal PFAS concentration with EAA. Bayesian kernel machine regression with hierarchical selection estimated an exposure-response function for the PFAS mixture.

Results

In single pollutant models we observed an inverse relationship between perfluorodecanoate (PFDA) and EAA (−0.148 weeks per log-unit increase, 95% CI: −0.283, −0.013). Mixture analysis with hierarchical selection between perfluoroalkyl carboxylates and sulfonates indicated the carboxylates had the highest group posterior inclusion probability (PIP), or relative importance. Within this group, PFDA had the highest conditional PIP. Univariate predictor-response functions indicated PFDA and perfluorononanoate were inversely associated with EAA, while perfluorohexane sulfonate had a positive association with EAA.

Conclusions

Maternal mid-pregnancy serum concentrations of PFDA were negatively associated with EAA in cord blood, suggesting a pathway by which prenatal PFAS exposures may affect infant development. No significant associations were observed with other PFAS. Mixture models suggested opposite directions of association between perfluoroalkyl sulfonates and carboxylates. Future studies are needed to determine the importance of neonatal EAA for later child health outcomes.

Keywords: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), Epigenetic Aging, Prenatal Exposures, Mixtures Analysis, Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylates, Perfluoroalkyl Sulfonates

1. Introduction1

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a diverse class of chemicals defined by the presence of highly stable perfluorinated carbon chains.(Evich et al., 2022) Their stability leads to persistence and ubiquity within the environment; most PFAS degrade slowly under environmental conditions and some bioaccumulate through multiple pathways.(Evich et al., 2022) PFAS can now be detected around the globe (ATSDR, 2022) and in humans, including in over 99% of participants in the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as well as the more recent survey in 2017-2018.(CDC, 2022) Exposure can commonly occur through drinking water, air, diet, and dust, but infants can also be exposed in-utero through fetal transfer, and the exposure can continue through breastfeeding.(Blake and Fenton, 2020; EPA, 2016) Due to fetal transfer through the placenta, there are detectable levels of PFAS in infants’ cord blood, with strong correlations with maternal PFAS levels during pregnancy.(Gützkow et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020) In-utero exposures to PFAS have been shown to affect birth outcomes and pre- and postnatal growth.(Johnson et al., 2014; Liew et al., 2018; Rappazzo et al., 2017; Starling et al., 2019, 2017) Observed childhood health effects associated with prenatal PFAS exposures include dyslipidemia, altered renal and cardiometabolic function, and immunosuppressive effects.(Johnson et al., 2014; Liew et al., 2018; Rappazzo et al., 2017) In-utero exposure has also been associated with changes in offspring DNA methylation, at both individual CpG sites and regions, including some located in genes with roles in growth, cardiometabolic, and immune health.(Liu et al., 2022; Starling et al., 2020)

A possible mechanism that could link prenatal PFAS exposures to later child health outcomes is exposure-related changes in the rate of biological aging. Due to predictable age-related changes in methylation patterns and sensitivity to environmental factors, epigenetic clocks have been proposed as a promising measure to estimate biological aging.(Horvath and Raj, 2018; Jylhävä et al., 2017) Though there is a strong correspondence between epigenetic and chronologic ages overall, an individual’s epigenetic age can differ greatly from their chronological age.(Horvath and Raj, 2018) Epigenetic age acceleration (EAA), or the discrepancy between an individual’s epigenetic age relative to chronological age, has been associated with various disease or health states as well as lifestyle and environmental factors among adults. However, while an increased epigenetic age is associated with adverse health outcomes among adult populations, the relationship between gestational epigenetic aging and health is less clear.(Dieckmann et al., 2021; Girchenko et al., 2017) Since decelerated epigenetic aging, or a biologic age lower than expected, has typically been associated with adverse pregnancy exposures and health outcomes and accelerated EAA with some positive outcomes, decelerated aging is hypothesized to indicate lower developmental maturity.(Girchenko et al., 2017; Knight et al., 2018) This discrepancy between biological and chronological age may predict risk for later health outcomes.(Girchenko et al., 2017) To our knowledge, no previous studies have reported on the relationship between prenatal PFAS and gestational epigenetic age acceleration in cord blood, and the relationship could provide insight on how PFAS exposures impact infant development.

In this study we aimed to assess relationships between maternal PFAS serum concentrations during pregnancy and epigenetic age acceleration among infants from the Healthy Start longitudinal cohort study using DNA methylation in cord blood collected at birth. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate associations between PFAS and the estimated proportions of various immune cell types in cord blood to explore the potential role of immune cell composition in the relationship between PFAS exposure and epigenetic aging. Given our previous observation that maternal PFAS concentrations were associated with lower birth weight in this population,(Starling et al., 2017) we hypothesized that greater serum concentrations of individual PFAS and the overall PFAS mixture would be associated with greater epigenetic age deceleration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

The Healthy Start study is a prospective cohort study that recruited 1,410 pregnant women from outpatient obstetrics clinics at the University of Colorado Hospital between 2009-2014. Enrollment requirements included being 16 years or older, pregnant with single fetus, less than 24 weeks of gestation, have no history of extremely preterm birth or stillbirth, and no self-reported diabetes, asthma, cancer, or psychiatric illness requiring medication. Participants completed questionnaires, provided blood samples during pregnancy, and allowed review of medical records. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved study procedures and all participants provided written informed consent. PFAS analysis in de-identified serum samples was performed at the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) laboratory; the participation of the CDC laboratory was determined to not constitute human subjects research.

2.2. Exposure Assessment

Venous blood samples were collected from pregnant women at a median of 27 weeks of gestation (range: 20-34 weeks); serum was promptly separated and stored at −80 °C. Quantification of 11 PFAS was performed at CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Laboratory Sciences, using the method described by Kato et al. (2011).(Kato et al., 2011) The 11 PFAS included perfluorooctane sulfonamide (FOSA), 2-(N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (EtFOSAA), 2-(N-methyl perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (MeFOSAA), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorodecanoate (PFDA), perfluorononanoate (PFNA), as well as both linear PFOA (n-PFOA) and the sum of branched isomers of PFOA (Sb-PFOA), and linear PFOS (n-PFOS) and the sum of perfluoromethylheptane sulfonate isomers (Sm-PFOS) and the sum of perfluorodimethylhexane sulfonate isomers (Sm2-PFOS). Total PFOA concentration was calculated as the sum of n-PFOA and Sb-PFOA, and total PFOS was calculated as the sum of n-PFOS, Sm-PFOS, and Sm2-PFOS concentrations. For this analysis, only PFAS with detectable concentrations in >90% of subjects were included; these were PFHxS, PFNA, PFDA, and the summed totals of PFOS and PFOA. The limit of detection (LOD) for all PFAS was 0.1 ng/mL; for concentrations below this value, we used instrument values when available and replaced values reported as zero with LOD/2. PFAS concentrations were natural log-transformed to reduce the influence of outliers.

2.3. Analysis of DNA Methylation in Cord Blood

As described in Yang et al. 2017,(Yang et al., 2017) DNA was extracted with QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). Purity was assessed with Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher), quality examined with Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent), and quantity analyzed with Qubit fluorometer (ThermoFisher). Methylation analysis included only samples with ratio of absorbance 260/280 > 1:8, a DNA Integrity Score > 7, and >= 500 ng of DNA. Bisulfite conversion was performed with Zymo EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research), using commercially available positive and negative control samples. Genome-wide methylation was assessed with Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array using previously published methods.(Yang et al., 2017)

2.4. Quality Control for Methylation Data

Quality control of the methylation data included the removal of 1 sample with low median intensity, defined as a median methylated intensity less than three times the interquartile range below the 25th percentile; no upper outlying samples were identified with a median methylated intensity greater than three times the interquartile range above the 75th percentile. We also removed 6 samples with mismatched sex between the clinical data and predicted sex through the getSex function from the R package minfi (v 1.34.0).(Andrews et al., 2016; Aryee et al., 2014; Fortin et al., 2017, 2014; Fortin and Hansen, 2015; Maksimovic et al., 2012; Triche et al., 2013) No samples showed a detection p-value greater than 0.01 in more than 1% of probes. We removed 699 probes with a detection p-value greater than 0.01 in more than 10% of samples, 660 probes with a bead count <3 in at least 5% of samples, and 17,272 probes with SNPs at the CpG interrogation and/or at the single nucleotide extension for any minor allele frequency, identified using the annotation information from the addSnpInfo function from minfi.(Andrews et al., 2016; Aryee et al., 2014; Fortin et al., 2017, 2014; Fortin and Hansen, 2015; Maksimovic et al., 2012; Triche et al., 2013) Additionally, we removed 27,349 cross-reactive probes.(Chen et al., 2013) We performed stratified quantile normalization using the preprocessQuantile function from minfi,(Andrews et al., 2016; Aryee et al., 2014; Fortin et al., 2017, 2014; Fortin and Hansen, 2015; Maksimovic et al., 2012; Triche et al., 2013) and removed batch effects by sample plate using ComBat from the R package sva (v 3.36.0).(Leek et al., 2022) Quality control steps were performed with R version 4.0.2.

2.5. Assessment of Maternal and Neonatal Characteristics

Participants self-reported their age, education, household income, parity, smoking status during pregnancy and race/ethnicity. Parity (number of live births prior to the current pregnancy) was categorized into 3 categories, indicating those with no previous (parity of 0), 1-2 previous, or 3 or more previous live births. Infant sex was either reported by the mother shortly after delivery or abstracted from the medical record. Infants’ gestational age at time of PFAS measurement and at birth was calculated based primarily on the timing of the last menstrual period; gestational dating was sometimes updated by clinicians based on ultrasound. Umbilical cord blood was collected at time of delivery when clinical conditions allowed.

2.6. Outcome Assessment

2.6.1. Epigenetic Age and EAA

We calculated epigenetic age for each subject using the cord blood-specific clock developed by Knight(Knight et al., 2016) with the DNAmGA function from the R package methylclock (v. 1.0.1).(Pelegri-Siso and Gonzalez, 2022) Although Bohlin et al. also developed a cord blood-specific clock for gestational age,(Bohlin et al., 2016) Knight’s clock was selected here for three main reasons. First, Bohlin’s clock was trained on an all European-based cohort, while Knight’s clock was developed with infants from multiple races/ethnicities, including 17% of participants in their training data identifying as black and 18% coming from a Mexican nationality. This is better suited for our multi-ethnic cohort. Additionally, when developing the model, Bohlin’s clock adjusted for estimated cell composition, while Knight’s clock did not adjust for any additional covariates. Given we hypothesized that changes in cell composition could be a possible causal intermediate in the association between PFAS and EAA, we deemed it important that the clock did not adjust for these variables when it was developed.

Following the quantile normalization discussed previously, we additionally performed BMIQ normalization,(Teschendorff et al., 2013) further adapted by Horvath,(Horvath, 2013) using the DNAmGA function(Pelegri-Siso and Gonzalez, 2022), which adjusted for the type-2 bias in Illumina Infinium 450k data. This function also imputed any missing clock CpGs using nearest neighbor averaging, which included only 1 CpG in the post-QC data, and estimated cell composition using the method proposed by Houseman(Houseman et al., 2012) and the R package meffil.(Suderman, 2022) We used a combined reference for cord blood generated using data from four reference datasets.(Bakulski et al., 2016; de Goede et al., 2016; “FlowSorted.CordBloodCombined.450k,” 2021; Gervin et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2018)

EAA measures the discrepancy between chronologic and epigenetic age, and we calculated this as the residuals after regressing epigenetic age on chronologic gestational age. Unlike the raw difference between the two measures, the residuals are uncorrelated with chronologic age.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were checked for normality and outliers. Only subjects with complete data for PFAS concentrations and covariates were included (n=577). All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.1.3.

2.7.1. Linear regression models of the association between PFAS and EAA

We fit linear regression models to estimate associations between natural log-transformed PFAS concentrations and EAA, adjusting for potential confounders. We identified potential confounders based on previous studies of PFAS and cord blood DNA methylation, and these included: gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, infant sex, maternal parity, education (as a proxy for socioeconomic status), race/ethnicity, gestational smoking, maternal age, and pre-pregnancy BMI.(Kingsley et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022; Miura et al., 2018; Starling et al., 2020). We prioritized covariates that were significantly associated (p-value < 0.05) with any PFAS or EAA in univariate analyses. Examination of variance inflation factors confirmed that the inclusion of both maternal education and race/ethnicity in the models did not result in multicollinearity. We tested for potential effect modification by infant sex by the inclusion of a PFAS-by-sex interaction term, but this term was not found to be significant in any models. Therefore the final models included gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, infant sex, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity.

Others have noted a distinction between “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” EAA, where the former captures EAA independent of age-related immune cell composition changes while the latter includes such effects(Daredia et al., 2022). The effects of immune cell changes with EAA were originally explored with Horvath’s pan-tissue clock and Hannum’s blood-based clock for adult populations (Horvath and Ritz, 2015) and the idea has since been expanded to other clocks by evaluating EAA calculated with the inclusion or exclusion of adjustments for estimated cell type proportions in the regression of estimated epigenetic age on chronological age.(Daredia et al., 2022) While these expanded EAA methods are not explicitly designed to correlate with age-related changes in blood cell counts, by omitting adjustment for cell type proportions they do include aging effects mediated through changes in immune cell populations. Since we primarily wished to characterize the overall impact of PFAS exposures on EAA, we did not adjust for estimated proportions of cord blood cell types in the primary models. However, we did additionally explore the relationships between PFAS levels and epigenetic aging that adjusts for immune cell composition differences (commonly referred to as “intrinsic” aging) by calculating a separate metric of epigenetic age acceleration: the residual of epigenetic gestational age regressed on chronologic gestational age while adjusting for cell composition, including the estimated proportions of 7 cell types: B, CD4 T lymphocytes (CD4T), cytotoxic T cells (CD8T), monocytes, natural killer (NK), granulocytes, and nucleated red blood cells (nRBC), using the DNAmGA function in methylclock.(Pelegri-Siso and Gonzalez, 2022) We then performed linear regression to test for associations between the 5 natural log-transformed PFAS and this alternative outcome of cell-type-adjusted EAA, using the same covariates as the previous models.

Previous research suggested PFAS exposures are associated with changes in immune cells.(Abraham et al., 2020; DeWitt et al., 2016; Goodrich et al., 2021; National Toxicology Program, 2021; Liu et al., 2022) To provide some additional biological context in the potential role of immune cell changes and aid in the interpretation of the observed relationship between PFAS exposures and epigenetic aging, we tested for associations of the PFAS levels with estimated immune cell type proportions of B, CD4T, and CD8T cells, granulocytes, monocytes, NK cells and nRBC in cord blood. We employed linear regression, with the log-transformed PFAS as the exposure and the cell type proportion as the outcome, and adjustment for the previously identified covariates (infant sex, gestational age at PFAS measurement, and maternal education, parity, and race/ethnicity). We also modeled the relationship of EAA and estimated cell proportions with EAA as the outcome and 6 estimated cell types B, CD4T, CD8T, monocytes, NK, and nRBC as exposures. To reduce collinearity among predictors in the model, we did not include the estimated proportion of the granulocytes in the multivariate model of cell types with EAA as this cell type showed the greatest correlation values with the other cell types.

We did not perform multiple testing correction for our models because we are examining 5 PFAS with different levels of existing evidence for associations with DNA methylation in cord blood, and exposures are correlated so we do not expect results to be independent. We instead focus on the magnitude and precision of the beta-coefficient rather than the p-value, and present mixture models to reduce the number of statistical tests run and to account for the correlation among PFAS concentrations due to common sources of exposure. Sensitivity analyses with the exclusion of any PFAS concentrations < LOD were performed to confirm that results were not driven by non-detectable concentrations.

2.6.3. BKMR

Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) is a method to estimate the health effects of mixtures of exposures in a flexible framework that allows for identification of nonlinear and nonadditive effects, adjustment for confounders, and grouped variable selection to address high correlation between the exposures.(Bobb et al., 2018) It identifies important exposures in the mixture by calculating posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) that describe the relative importance of that component of the mixture. BKMR also models the non-parametric exposure-response function, while adjusting for covariates with an assumed linear relationship with the outcome.(Bobb et al., 2018) This function describes the effect of the PFAS mixture on EAA and, when using the hierarchical selection procedure, depicts the contributions of both joint and single PFAS to the outcome. The exposure-response function was estimated with a Gaussian kernel and the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm.(Bobb et al., 2018) Analysis was completed using the R package bkmr (v. 0.2.2).(Bobb et al., 2018) We used non-informative, default settings for prior specifications and 10,000 iterations for MCMC. We checked model convergence with trace plots for the parameter values. All continuous variables, including the EAA outcomes, PFAS concentrations, and gestational age at time of measurement, were scaled and centered prior to model fitting.

Due to a priori knowledge and strong observed within-group correlations among the perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFOA, PFNA, PFDA) and perfluoroalkyl sulfonates (PFOS, PFHxS), the hierarchical variable selection procedure in BKMR was used to create two non-overlapping groups. We confirmed our group selection using complete linkage hierarchical clustering. This procedure enforced that at most one of the components from each group could enter the model at a time. From this, both group PIPs and conditional PIPs were calculated, indicating the proportion of the models that included the exposure (or group of exposures) and signifying its relative importance in predicting the outcome. Covariates again included infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity. Exposure-response functions were visualized, and overall, single-variable, and interactive effects were summarized.

3. Results

Of the 1,410 participants enrolled in the Healthy Start study, 600 had cord blood DNA methylation analyzed. Of these, 5 later revoked consent, 7 were excluded due to quality control, and 11 were excluded due to missing data on maternal PFAS concentrations (Figure S1). Therefore, the total sample size of our analysis was 577 subjects; characteristics of the included mother-infant pairs (Table 1) were similar to those of the full potentially eligible cohort (Table S1). This was a multi-ethnic cohort, with 54% of mothers identifying as non-Hispanic white, 24% as Hispanic, 15% as non-Hispanic black, and 6% as non-Hispanic other. PFAS measures were collected for 193 subjects (33.4%) during the second trimester, and 384 subjects (66.6%) during the third trimester. The median mid-pregnancy maternal serum PFAS concentrations (Table 2) were slightly lower than the median values observed among females in the general US population during the same time period (Table S2).(CDC, 2022) The five PFAS with >90% of detectable concentrations exhibited moderate to high Spearman correlations, with the correlations roughly grouping by carboxylates (PFDA, PFNA, and PFOA) and sulfonates (PFHxS, PFOS) (Table S3). The mean gestational age of infants at birth was 39.5 weeks (sd 1.2) and the mean epigenetic age was 34.6 weeks (sd 1.2). A moderately high correlation between gestational epigenetic age and chronological gestational age was observed (Pearson’s r = 0.599; p-value < 0.001; Figure S2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 577 mother–infant pairs in the Healthy Start study who were eligible for this analysis.

| Maternal and infant characteristics | Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gestational Age at Birth (weeks) a | 39.5 ± 1.2 |

| Gestational Age at PFAS Measurement (weeks) a | 27.3 ± 2.4 |

| Maternal Age at Birth (years) a | 27.6 ±6.2 |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) a | 25.9 ± 6.6 |

| Infant Sex | |

| Female | 277 (48) |

| Male | 300 (52) |

| Preterm | |

| Term | 561 (97) |

| Preterm | 16 (3) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 292 (51) |

| 1-2 | 244 (42) |

| >=3 | 41 (7) |

| Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy | |

| No | 525 (91) |

| Yes | 52 (9) |

| Maternal Education | |

| Less than 12th grade | 92 (16) |

| High school degree or GED | 99 (17) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 125 (22) |

| Four years of college (BA, BS) | 127 (22) |

| Graduate degree (Master’s, PhD) | 134 (23) |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 311 (54) |

| Hispanic | 140 (24) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 89 (15) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 37 (6) |

Continuous variables presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GED, general educational development

Table 2.

Distribution of serum concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances (ng/mL) among 577 pregnant women (2009-2014)

| PFAS | Summary Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFASa | 25th Percentile | 50th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 95th Percentile | Range | % of Detectable Values a |

| PFDA | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | [<LOD, 3.5] | 92.4 |

| PFNA | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.1 | [<LOD, 4.3] | 99.5 |

| PFOA | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.7 | [0.1, 15.4] | 100.0 |

| PFHxS | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.8 | [<LOD, 10.9] | 99.1 |

| PFOS | 1.4 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 6.4 | [<LOD, 15.6] | 99.5 |

The limit of detection (LOD) for all PFAS was 0.1 ng/mL.

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate.

3.1. Linear regression models

The linear regression models between each of the 5 PFAS and EAA, adjusting for infant sex, gestational age at measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity (Figure S3), indicated a significant negative association between PFDA and EAA (Table 3). A 1 log-unit increase in PFDA was associated with an average decrease in EAA of 0.148 weeks (95% CI: −0.283, −0.013; p-value = 0.032), following adjustment with covariates. None of the other PFAS, including PFHxS, PFNA, PFOA, and PFOS, showed significant associations with EAA. PFAS-by-sex interaction terms were insignificant, and sex-stratified models reflected the same trends as observed in the full data (Table S4). Sensitivity analyses that excluded any PFAS concentrations < LOD showed similar results, suggesting the observed associations were not driven by such values (Table S5). After additional adjustment for cell composition in calculating age acceleration to capture aging independent of changes in immune cell proportions, no significant findings were observed (Table S6). There was also a significant inverse association between PFDA levels and CD8T cell proportions (−0.005, 95% CI: −0.009, −0.000), as well as direct association between PFNA levels and NK cells (0.007, 95% CI: 0.000, 0.013), following adjustment for the previously defined covariates (Table 4). None of the other PFAS (PFOA, PFHxS, or PFOS) showed significant associations with the cell types. Significant associations were observed across multiple estimated cell type proportions and EAA (Table S7). Decreased proportions of B-cells, CD4T cells, and nRBCs were all significantly associated with increased EAA in a linear model of the cell types with EAA as the outcome.

Table 3.

Associations between maternal PFAS concentrations and EAA.

| PFAS | Difference in EAA (weeks) for 1 ln-unit increase of PFAS concentration (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| ln(PFDA) | −0.148 (−0.283, −0.013) | 0.032 |

| ln(PFNA) | −0.119 (−0.252, 0.014) | 0.080 |

| ln(PFOA) | −0.083 (−0.218, 0.053) | 0.230 |

| ln(PFHxS) | 0.044 (−0.059, 0.148) | 0.398 |

| ln(PFOS) | −0.005 (−0.117, 0.108) | 0.935 |

Models adjusted for infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity.

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate.

Table 4.

Associations between maternal PFAS concentrations and estimated proportions of each cell type in umbilical cord blood.

| PFAS | Cell Type | Difference in proportion of this cell type for a 1 ln-unit increase in each PFAS (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| ln(PFDA) | B-cells | 0.003 (−0.001, 0.007) |

| CD4T | 0.002 (−0.007, 0.010) | |

| CD8T | −0.005 (−0.009, −0.000) | |

| Monocytes | 0.002 (−0.003, 0.007) | |

| NK | 0.004 (−0.003, 0.010) | |

| nRBC | 0.002 (−0.009, 0.013) | |

| Granulocytes | −0.008 (−0.025, 0.010) | |

| ln(PFNA) | B-cells | 0.003 (−0.001, 0.007) |

| CD4T | 0.005 (−0.004, 0.013) | |

| CD8T | 0.000 (−0.004, 0.005) | |

| Monocytes | −0.001 (−0.006, 0.004) | |

| NK | 0.007 (0.000, 0.013) | |

| nRBC | −0.006 (−0.017, 0.005) | |

| Granulocytes | −0.009 (−0.026, 0.008) | |

| ln(PFOA) | B-cells | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.003) |

| CD4T | 0.003 (−0.005, 0.012) | |

| CD8T | −0.001 (−0.006, 0.003) | |

| Monocytes | −0.003 (−0.008, 0.002) | |

| NK | 0.004 (−0.003, 0.011) | |

| nRBC | −0.001 (−0.012, 0.010) | |

| Granulocytes | −0.001 (−0.019, 0.017) | |

| ln(PFHxS) | B-cells | −0.002 (−0.005, 0.001) |

| CD4T | −0.003 (−0.009, 0.004) | |

| CD8T | −0.000 (−0.004, 0.003) | |

| Monocytes | −0.002 (−0.005, 0.002) | |

| NK | 0.001 (−0.004, 0.007) | |

| nRBC | 0.004 (−0.004, 0.013) | |

| Granulocytes | 0.002 (−0.011, 0.016) | |

| ln(PFOS) | B-cells | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.001) |

| CD4T | 0.002 (−0.005, 0.009) | |

| CD8T | −0.000 (−0.004, 0.003) | |

| Monocytes | 0.000 (−0.004, 0.004) | |

| NK | 0.002 (−0.003, 0.008) | |

| nRBC | 0.003 (−0.006, 0.012) | |

| Granulocytes | −0.004 (−0.019, 0.010) |

Models adjusted for infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity.

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate; CD4T, CD4 T lymphocytes; CD8T, cytotoxic T cells; NK, natural killer cells; nRBC, nucleated red blood cells.

3.2. BKMR

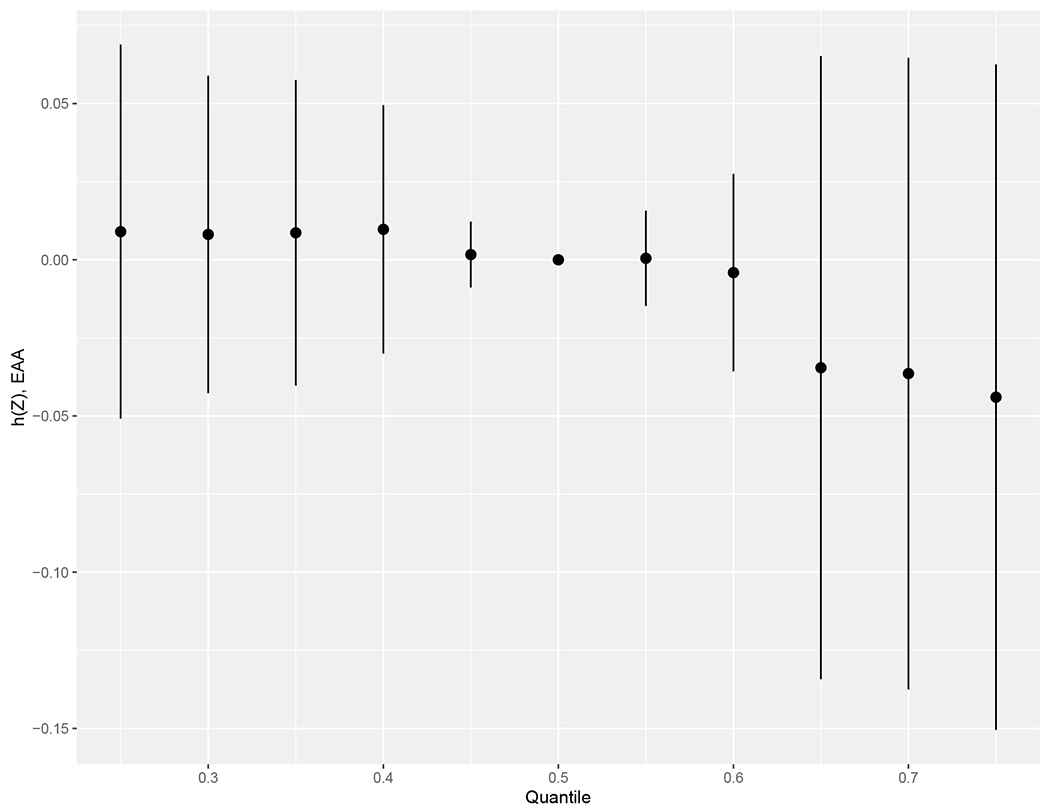

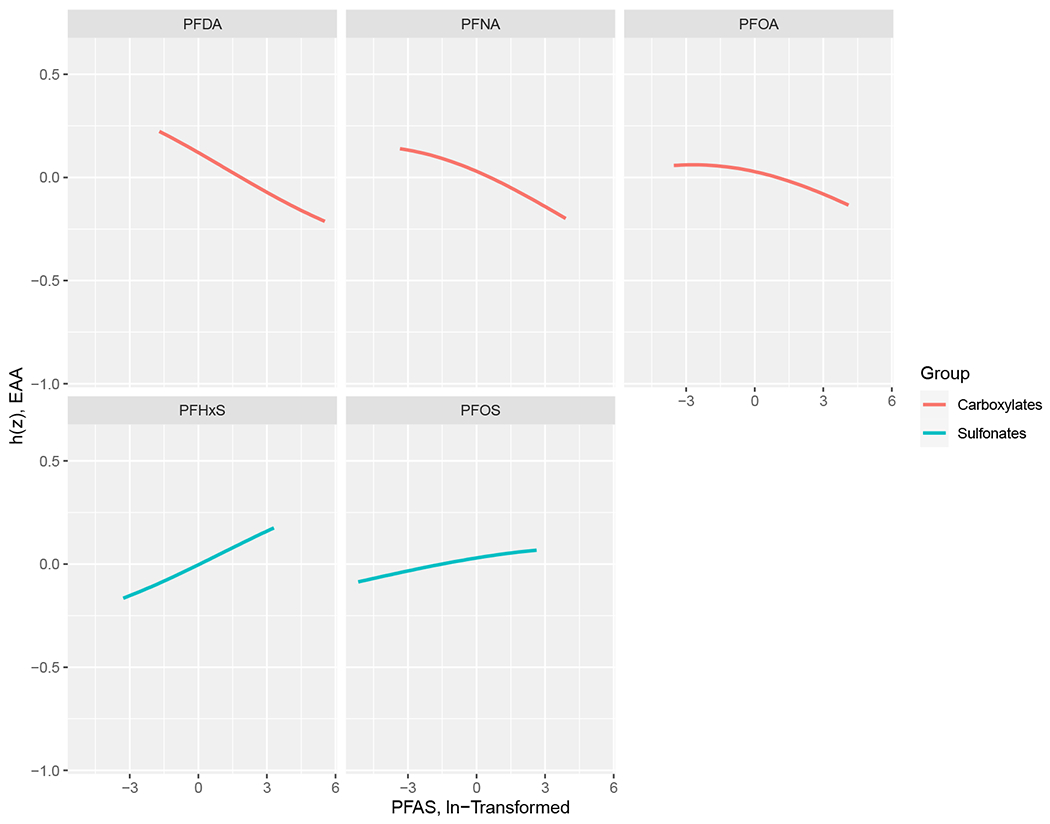

The relationship between the PFAS mixture and EAA was examined with BKMR, adjusting for the same confounders as the linear regression models (infant sex, gestational age at PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity). Based on the correlation structure, complete linkage hierarchical cluster analysis, and a priori knowledge of the PFAS compositions, hierarchical selection was used to group the carboxylates (PFOA, PFNA, PFDA) and sulfonates (PFHxS and PFOS). Group PIPs indicated that carboxylates had the highest importance (Table 5). Conditionally, PFDA showed the highest PIP among the carboxylates, followed by PFNA and PFOA. PFHxS showed the highest PIP among the sulfonates, followed by PFOS. The overall PFAS mixture was not significantly associated with EAA, which may be due to the opposing trends among the PFAS (Figure 1).

Table 5.

Posterior Inclusion Probabilities (PIP) for PFAS in exposure-response function with EAA, using hierarchical selection in a Bayesian kernel machine regression model.

| PFASa | Group | Group PIPb | Conditional PIP |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ln(PFDA) | Carboxylates | 0.764 | 0.410 |

| ln(PFNA) | Carboxylates | 0.764 | 0.335 |

| ln(PFOA) | Carboxylates | 0.764 | 0.255 |

| ln(PFHxS) | Sulfonates | 0.399 | 0.568 |

| ln(PFOS) | Sulfonates | 0.399 | 0.432 |

Models adjusted for infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, education, and race/ethnicity.

Hierarchical selection performed by grouping PFAS into carboxylates (PFDA, PFNA, PFOA) and sulfonates (PFHxS, PFOS)

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate;

PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate

Figure 1.

Overall effect (95% credible interval) of the PFAS mixture on EAA, estimated by Bayesian kernel machine regression. Estimates present the difference in the response (EAA) when all the PFAS are fixed at a specific quantile, as compared to when all the exposures are fixed at their median value. h(Z) can be interpreted as the relationship between the PFAS mixture and EAA. The model implemented hierarchical selection between carboxylates (PFDA, PFNA, PFOA) and sulfonates (PFHxS, PFOS) and was adjusted for infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, educational levels, and race/ethnicity.

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate

Univariate predictor-response plots for each PFAS indicated that the carboxylates showed decreasing trends in the exposure-response function when fixing all other chemicals at their median values, with greater maternal PFAS serum concentration associated with greater epigenetic age deceleration (Figure 2). On the other hand, the sulfonates showed a positive trend with EAA. Bivariate predictor-response plots (Figure S4) suggested no interactions between PFAS with this hierarchical model.

Figure 2.

Univariate exposure–response function (95% credible interval) between PFAS serum concentrations and EAA while fixing the concentrations of other PFAS at median values, estimated by Bayesian kernel machine regression. h(Z) can be interpreted as the relationship between chemicals and EAA. Model adjusted for infant sex, gestational age at time of PFAS measurement, and maternal parity, educational levels, and race/ethnicity.

Abbreviations: PFDA, perfluorodecanoate; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonate; PFNA, perfluorononanoate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate

4. Discussion

In this study using data from a racially and ethnically diverse population of mother and child pairs, linear regression analyses showed a significant negative association between mid-pregnancy maternal serum PFDA concentrations and EAA in infants’ cord blood at birth. No statistically significant associations were observed among the other PFAS examined (PFHxS, PFNA, PFOA, or PFOS). There were significant inverse relationships between estimated proportions of B-cells, CD4T cells, and nRBC and EAA. There was also a significant positive association between maternal PFNA and NK cells and a significant negative association between PFDA and CD8T cells in cord blood. A mixtures analysis using BKMR indicated opposing trends of epigenetic aging between the carboxylates and sulfonates. There was a negative trend between EAA and the carboxylates PFDA and PFNA while there was a positive trend with the sulfonates. BKMR also indicated the carboxylates had greater importance in predicting the outcome compared to the sulfonates, with PFDA having the highest importance among the carboxylates. There was no overall significant effect of the PFAS mixture on EAA, but the opposing trends between the carboxylates and sulfonates may be obscuring any trends in the overall mixture.

Maternal serum concentrations of PFAS during pregnancy represent a source of exposure for the developing infant. Detectable concentrations of PFAS are observed in cord blood due to placental transfer, and strong correlations are observed between maternal PFAS concentrations during pregnancy and PFAS concentrations among infants’ cord blood at birth.(Gützkow et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020) Though transfer efficiency of the PFAS varies by carbon chain length and functional group,(Gützkow et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020) maternal serum PFAS concentrations are good proxies for fetal body burden.(Manzano-Salgado et al., 2015)

EAA among adults, calculated using other epigenetic clocks, has been associated with numerous chronic conditions, lifestyle, and environmental factors,(Horvath, 2013; Horvath and Raj, 2018) as well as with all-cause mortality.(Marioni et al., 2015) Few studies have examined the relationships between PFAS and EAA, and none of the published studies have examined the association between prenatal PFAS exposures and EAA in cord blood. Previous research found EAA was associated with serum PFOA, PFOS, and Sm-PFOS concentrations among 197 firefighters, who may experience greater PFAS exposures than the general population.(Goodrich et al., 2021) The authors quantified 9 PFAS, including those we explored here, and examined associations with 7 epigenetic clocks for adults. There were positive associations of PFAS concentrations with nearly all measurements across the PFAS and clocks. However, one notable exception was a significant inverse association observed between PFDA and PFUnDA and epigenetic age acceleration using the adult-based GrimAge clock.(McCrory et al., 2021) Similar to our findings regarding PFAS and immune cells, they also found a significant inverse association between n-PFOS and PFDA and estimated proportions of monocytes, and between PFNA and NK cells following adjustment for covariates. Another study found high versus background concentrations of PFAS were not associated with EAA among 63 children aged 7-11 years in the Swedish Ronneby Biomarker Cohort.(Xu et al., 2022) These authors calculated epigenetic age using the skin-and-blood clock, which was developed using methylation from skin and blood tissues but over a wide range of ages and not specific to children.(Horvath et al., 2018)

While accelerated aging has been associated with adverse outcomes among adults, the relationship between gestational epigenetic aging and health outcomes among infants is not as clear. Certain adverse outcomes and exposures, including maternal history of insulin-treated gestational diabetes mellitus in a previous pregnancy, depression, Sjogren’s syndrome, or early childhood psychiatric problems have been linked to lower than expected epigenetic age.(Girchenko et al., 2017; Palma-Gudiel et al., 2019; Suarez et al., 2018) Higher than expected epigenetic age for gestational age in extremely preterm infants (born < 28 weeks gestation) was associated with positive health outcomes, such as a lower need for respiratory interventions, perhaps due to greater developmental maturity.(Knight et al., 2018) Given these findings, it was suggested that epigenetic ages lower than expected for gestational age among infants may reflect lower developmental maturity.(Girchenko et al., 2017; Knight et al., 2018) However, greater EAA than expected in infants was also associated with negative health conditions in another study, including lower birth length, a lower 1-min Apgar score, and adverse exposures including maternal preeclampsia, maternal age over 40 years at delivery, and treatment with antenatal betamethasone, perhaps contradicting this hypothesis.(Girchenko et al., 2017) Therefore, it is still unclear how higher versus lower than expected epigenetic gestational age is related with health status in infants. Some have also suggested that this period of development follows a specific tempo and changes from this trajectory in either direction may be related to adverse health outcomes.(Daredia et al., 2022) EAA in cord blood might be best understood as a summary indicator of prenatal epigenetic programming, and may describe increased risk for later adverse health outcomes.(Girchenko et al., 2017; Knight et al., 2018)

Cord blood is a heterogeneous tissue consisting of several cell types and there are known age-related changes in immune cell composition.(Daredia et al., 2022) It has been noted that there are significant relationships between some cell-type proportions and EAA calculated with Knight’s clock, reflecting that models unadjusted for cell types capture extrinsic epigenetic age acceleration which may be more responsive to environmental conditions.(Daredia et al., 2022) On the other hand, calculating EAA with adjustment for cell types can capture a more “intrinsic” aging process. Our interest in this study was to assess the overall impact of prenatal PFAS exposure on EAA; this includes effects that are mediated by changes in cell composition. Therefore, we did not adjust our primary models for estimated proportions of cell types. When we calculated EAA with adjustment for cell composition to assess a more intrinsic aging process that is independent of immune cell composition, no significant associations were observed between any of the 5 PFAS. This perhaps reflects the effect of PFAS exposures on the immune system and cell composition as a mechanism underlying the relationship. Further reflecting the role of immune system changes, we observed significant decreases in CD8T cells with increasing PFDA concentrations, and significant increases in NK cells with increasing PFNA concentrations.

Similar to our observations here, the previously mentioned study of 197 firefighters found significant inverse associations between n-PFOS and PFDA concentrations in blood and estimated monocytes and n-PFOS and PFDA and a significant inverse association between PFNA and NK cell proportions in adult blood.(Goodrich et al., 2021) A study on gestational PFAS concentrations and methylation showed increasing tertiles of PFOS concentrations in cord blood were associated with lower B-cell proportions and increasing tertiles of PFNA concentrations were associated with lower nRBC proportions in cord blood.(Liu et al., 2022)

This study assessed all of the PFAS examined here except for PFDA. In addition to the relationships of PFAS and immune cells, other studies have also highlighted how PFAS exposure can weaken the immune system, noted by suppressed T-cell-dependent antibody response in adult mice,(DeWitt et al., 2016) and associations in epidemiologic studies with lower concentrations of vaccine antibodies against tetanus and diphtheria in children,(Abraham et al., 2020) and increased severity of COVID-19 in adults.(Grandjean et al., 2020) Two of the most commonly measured PFAS, PFOS and PFOA, are known immune hazards according to the National Toxicology Program.(ATSDR, 2021).

The mechanisms by which PFAS exposure affects immunological outcomes have not been fully elucidated, though for some outcomes PFAS interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) may have a role.(Bell et al., 2021) These nuclear receptors regulate gene expression and are important in lipid and glucose metabolism and immunity.(Bell et al., 2021; Berger and Moller, 2002) Furthermore, they regulate the immune system and are expressed in immune cells such as monocytes, macrophages, T and B cells.(Bell et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2000) Carboxylates have been found to be full human PPAR-alpha agonists while sulfonates are partial agonists.(Nielsen et al., 2021) Furthermore, longer carbon chain carboxylates were more potent PPAR agonists than PFAS with shorter carbon chains.(Nielsen et al., 2021) It is suspected that the effect of PFAS on PPARs may underlie their immunotoxic effects.(Bell et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2000)

Mirroring these findings, in this study the longer carbon chain carboxylate PFDA was associated with decelerated epigenetic aging, and mixture analyses suggest the carboxylates may have a stronger effect on epigenetic aging than the sulfonates. Overall, the carboxylates had a stronger relationship with epigenetic aging and the magnitude of the association increased with increasing carbon-chain length – trends that were also previously observed with increasing PPAR agonism.(Nielsen et al., 2021) This suggests that PPAR agonism may underlie the negative association with EAA observed among the carboxylates. We also observed significant associations between the carboxylates PFDA and PFNA and the estimated proportions of CD8T and NK cell types in cord blood and PPARs are expressed in such cells. (Bell et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2000) The association between PFDA and EAA was attenuated following adjustment for cell types. On the other hand, a relationship between perfluoroalkyl sulfonates and EAA may be driven by another mechanism. An in-vitro study of human cell cultures found the carboxylate PFOA led to inhibition of cytokine production as a result of PPAR, while no such trend was observed for the sulfonate PFOS, suggesting a different mechanism of action between the two.(Bell et al., 2021; Corsini et al., 2011; Reddy et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2000) Additionally, no estimated cell type proportions were significantly associated with PFOS or PFHxS in our study.

Strengths of this study included a relatively large sample size, and the inclusion of multiple PFAS in a BKMR model to flexibly estimate the exposure-response function of the mixture. The PFAS concentrations among the cohort mirrored those in the general US population,(CDC, 2022) while two previous studies of PFAS and epigenetic aging focused on adults and children, respectively, from highly exposed populations.(Goodrich et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022)

Limitations of this study include the use of maternal serum concentrations as a proxy for infant exposures. While previously shown to be a generally good proxy for fetal body burden,(Manzano-Salgado et al., 2015) it is unclear how much the different placental transfer efficiencies of the PFAS may affect our analysis. Some of the PFAS concentrations were below the method LOD. We substituted the LOD/2 for these concentrations, which is a common practice when a small percentage of concentrations are nondetectable, as observed here (<10%). However, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis treating concentrations <LOD as missing, which is unbiased if missingness depends only on the PFAS concentration.(Nie et al., 2010) As expected, both methods produced similar results. Our primary findings were for PFDA, which is present at relatively low concentrations in this population. As most concentrations of PFDA are near the LOD and the range of concentrations is relatively narrow, our findings may be influenced by measurement uncertainty. However, we did perform sensitivity analyses to ensure points with high leverage were not driving the findings. Additionally, while we found a relationship between PFAS concentrations and immune cell type proportions in cord blood, we are unable to perform a formal causal mediation analysis with our available data. Furthermore, EAA is calculated using only a few select CpGs, and it may not be the direct causal mechanism impacting health changes. Rather, EAA may be best viewed as a biomarker that correlates strongly with chronological gestational age and larger biological changes. Finally, mixtures of exposures vary both geographically and temporally so results may not be generalizable to other regions or exposure scenarios.(Blake and Fenton, 2020; Evich et al., 2022)

5. Conclusion

Maternal PFDA serum concentrations in pregnancy were negatively associated with EAA in cord blood. Mixture analysis suggested opposing directions of association with EAA for perfluoroalkyl carboxylates versus sulfonates. Significant associations between the carboxylates PFDA and PFNA and estimated T and NK cell types may suggest that PFAS exposure can affect the immune system and such changes are also related with altered biological aging processes. Future studies might explore the mechanisms underlying these relationships for different PFAS, particularly related to PPAR activation and immunotoxicity. Associations between prenatal PFAS exposure and decelerated epigenetic aging in newborns may suggest a mechanism by which such exposures could impact later health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Maternal perfluorodecanoate levels linked to decelerated epigenetic aging of child

Perfluoroalkyl carboxylates, sulfonates had opposing effects on epigenetic aging

Decelerated epigenetic aging associated with carboxylate exposures

Mixtures analysis reflects effects of complex PFAS exposure profiles

Epigenetic aging may suggest mechanism for PFAS exposure on later health outcomes

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of K. Kato, J. Ma, A. Kalathil, T. Jia, and the late Xiaoyun Ye (CDC, Atlanta, GA) in measuring the serum concentrations of PFAS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01DK076648), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R01ES022934), and the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (UH3OD023248).

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved study procedures and all participants provided written informed consent. PFAS analysis in de-identified serum samples was performed at the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) laboratory; the participation of the CDC laboratory was determined to not constitute human subjects research.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit Author Statement

Sierra S. Niemiec: Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization, Katerina Kechris: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Jack Pattee: Writing – Review & Editing, Ivana V. Yang: Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition, John L. Adgate: Writing – Review & Editing, Resources, Antonia M. Calafat: Writing – Review & Editing, Resources, Dana Dabelea: Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition, Anne P. Starling: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing

Declaration of conflicts of interest:

The authors declare they have nothing to disclose.

Colored Artwork:

Please include color in artwork for online publication only.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS); epigenetic age acceleration (EAA); perfluorodecanoate (PFDA); perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorodecanoate (PFDA), perfluorononanoate (PFNA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS); perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA); Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR); posterior inclusion probability (PIP)

References

- Abraham K, Mielke H, Fromme H, Völkel W, Menzel J, Peiser M, Zepp F, Willich SN, Weikert C, 2020. Internal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and biological markers in 101 healthy 1-year-old children: associations between levels of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and vaccine response. Arch. Toxicol 94, 2131–2147. 10.1007/s00204-020-02715-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SV, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Fallin MD, 2016. “Gap hunting” to characterize clustered probe signals in Illumina methylation array data. Epigenetics Chromatin 9, 56. 10.1186/sl3072-016-0107-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA, 2014. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 30, 1363–1369. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakulski KM, Feinberg JI, Andrews SV, Yang J, Brown S, L. McKenney S, Witter F, Walston J, Feinberg AP, Fallin MD, 2016. DNA methylation of cord blood cell types: Applications for mixed cell birth studies. Epigenetics 11, 354–362. 10.1080/15592294.2016.1161875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell EM, De Guise S, McCutcheon JR, Lei Y, Levin M, Li B, Rusling JF, Lawrence DA, Cavallari JM, O’Connell C, Javidi B, Wang X, Ryu H, 2021. Exposure, health effects, sensing, and remediation of the emerging PFAS contaminants – Scientific challenges and potential research directions. Sci. Total Environ 780, 146399. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Moller DE, 2002. The Mechanisms of Action of PPARs. Annu. Rev. Med 53, 409–435. 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biomonitoring Data Tables for Environmental Chemicals | CDC; [WWW Document], 2022. URL https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/data_tables.html (accessed 7.27.22). [Google Scholar]

- Blake BE, Fenton SE, 2020. Early life exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and latent health outcomes: A review including the placenta as a target tissue and possible driver of peri- and postnatal effects. Toxicology 443, 152565. 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, Valeri L, Coull BA, 2018. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ. Health 17, 67. 10.1186/s12940-018-0413-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin J, Håberg SE, Magnus P, Reese SE, Gjessing HK, Magnus MC, Parr CL, Page CM, London SJ, Nystad W, 2016. Prediction of gestational age based on genome-wide differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol. 17, 207. 10.1186/s13059-016-1063-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lemire M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Grafodatskaya D, Zanke BW, Gallinger S, Hudson TJ, Weksberg R, 2013. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209. 10.4161/epi.23470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini E, Avogadro A, Galbiati V, dell’Agli M, Marinovich M, Galli CL, Germolec DR, 2011. In vitro evaluation of the immunotoxic potential of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 250, 108–116. 10.1016/j.taap.2010.ll.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daredia S, Huen K, Van Der Laan L, Collender PA, Nwanaji-Enwerem JC, Harley K, Deardorff J, Eskenazi B, Holland N, Cardenas A, 2022. Prenatal and birth associations of epigenetic gestational age acceleration in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) cohort. Epigenetics 17, 2006–2021. 10.1080/15592294.2022.2102846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Goede OM, Lavoie PM, Robinson WP, 2016. Characterizing the hypomethylated DNA methylation profile of nucleated red blood cells from cord blood. Epigenomics 8, 1481–1494. 10.2217/epi-2016-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt JC, Williams WC, Creech NJ, Luebke RW, 2016. Suppression of antigen-specific antibody responses in mice exposed to perfluorooctanoic acid: Role of PPAR α and T- and B-cell targeting. J. Immunotoxicol 13, 38–45. 10.3109/1547691X.2014.996682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann L, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Kvist T, Lahti J, DeWitt PE, Cruceanu C, Laivuori H, Sammallahti S, Villa PM, Suomalainen-König S, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Raikkönen K, Binder EB, Czamara D, 2021. Characteristics of epigenetic aging across gestational and perinatal tissues. Clin. Epigenetics 13, 97. 10.1186/s13148-021-01080-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evich MG, Davis MJB, McCord JP, Acrey B, Awkerman JA, Knappe DRU, Lindstrom AB, Speth TF, Tebes-Stevens C, Strynar MJ, Wang Z, Weber EJ, Henderson WM, Washington JW, 2022. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science 375, eabg9065. 10.1126/science.abg9065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FlowSorted.CordBloodCombined.450k, 2021.

- Fortin J-P, Hansen KD, 2015. Reconstructing A/B compartments as revealed by Hi-C using long-range correlations in epigenetic data. Genome Biol. 16, 180. 10.1186/s13059-015-0741-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin J-P, Labbe A, Lemire M, Zanke BW, Hudson TJ, Fertig EJ, Greenwood CM, Hansen KD, 2014. Functional normalization of 450k methylation array data improves replication in large cancer studies. Genome Biol. 15, 503. 10.1186/s13059-014-0503-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin J-P, Triche TJ Jr, Hansen KD, 2017. Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC array with minfi. Bioinformatics 33, 558–560. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervin K, Salas LA, Bakulski KM, van Zelm MC, Koestler DC, Wiencke JK, Duijts L, Moll HA, Kelsey KT, Kobor MS, Lyle R, Christensen BC, Felix JF, Jones MJ, 2019. Systematic evaluation and validation of reference and library selection methods for deconvolution of cord blood DNA methylation data. Clin. Epigenetics 11, 125. 10.1186/s13148-019-0717-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girchenko P, Lahti J, Czamara D, Knight AK, Jones MJ, Suarez A, Hämäläinen E, Kajantie E, Laivuori H, Villa PM, Reynolds RM, Kobor MS, Smith AK, Binder EB, Räikkönen K, 2017. Associations between maternal risk factors of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes and the offspring epigenetic clock of gestational age at birth. Clin. Epigenetics 9, 49. 10.1186/s13148-017-0349-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich JM, Calkins MM, Caban-Martinez AJ, Stueckle T, Grant C, Calafat AM, Nematollahi A, Jung AM, Graber JM, Jenkins T, Slitt AL, Dewald A, Cook Botelho J, Beitel S, Littau S, Gulotta J, Wallentine D, Hughes J, Popp C, Burgess JL, 2021. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, epigenetic age and DNA methylation: a cross-sectional study of firefighters. Epigenomics 13, 1619–1636. 10.2217/epi-2021-0225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Timmermann CAG, Kruse M, Nielsen F, Vinholt PJ, Boding L, Heilmann C, Mølbak K, 2020. Severity of COVID-19 at elevated exposure to perfluorinated alkylates. PLoS ONE 15, e0244815. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gützkow KB, Haug LS, Thomsen C, Sabaredzovic A, Becher G, Brunborg G, 2012. Placental transfer of perfluorinated compounds is selective--a Norwegian Mother and Child sub-cohort study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 215, 216–219. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, 2013. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, R115. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-rll5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Oshima J, Martin GM, Lu AT, Quach A, Cohen H, Felton S, Matsuyama M, Lowe D, Kabacik S, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, Maierhofer A, Flunkert J, Aviv A, Hou L, Baccarelli AA, Li Y, Stewart JD, Whitsel EA, Ferrucci L, Matsuyama S, Raj K, 2018. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging 10, 1758–1775. 10.18632/aging.101508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Raj K, 2018. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 371–384. 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT, 2012. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 86. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) [WWW Document], 2021. URL https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/noncancer/completed/pfoa/index.html (accessed 7.27.22).

- Johnson PI, Sutton P, Atchley DS, Koustas E, Lam J, Sen S, Robinson KA, Axelrad DA, Woodruff TJ, 2014. The Navigation Guide—Evidence-Based Medicine Meets Environmental Health: Systematic Review of Human Evidence for PFOA Effects on Fetal Growth. Environ. Health Perspect 122, 1028–1039. 10.1289/ehp.1307893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, Hägg S, 2017. Biological Age Predictors. EBioMedicine 21, 29–36. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Wong L-Y, Jia LT, Kuklenyik Z, Calafat AM, 2011. Trends in exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. Population: 1999-2008. Environ. Sci. Technol 45, 8037–8045. 10.1021/esl043613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley SL, Kelsey KT, Butler R, Chen A, Eliot MN, Romano ME, Houseman A, Koestler DC, Lanphear BP, Yolton K, Braun JM, 2017. Maternal serum PFOA concentration and DNA methylation in cord blood: A pilot study. Environ. Res 158, 174–178. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight AK, Craig JM, Theda C, Bækvad-Hansen M, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Hansen CS, Hollegaard MV, Hougaard DM, Mortensen PB, Weinsheimer SM, Werge TM, Brennan PA, Cubells JF, Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Cheong JLY, Dalach P, Doyle LW, Loke YJ, Baccarelli AA, Just AC, Wright RO, Téllez-Rojo MM, Svensson K, Trevisi L, Kennedy EM, Binder EB, Iurato S, Czamara D, Räikkönen K, Lahti, Pesonen A-K, Kajantie E, Villa PM, Laivuori H, Hämäläinen E, Park HJ, Bailey LB, Parets SE, Kilaru V, Menon R, Horvath S, Bush NR, LeWinn KZ, Tylavsky FA, Conneely KN, Smith AK, 2016. An epigenetic clock for gestational age at birth based on blood methylation data. Genome Biol. 17, 206. 10.1186/s13059-016-1068-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight AK, Smith AK, Conneely KN, Dalach P, Loke YJ, Cheong JL, Davis PG, Craig JM, Doyle LW, Theda C, 2018. Relationship between Epigenetic Maturity and Respiratory Morbidity in Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr 198, 168–173.e2. 10.1016/jjpeds.2018.02.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learn about PFAS | ATSDR; [WWW Document], 2022. URL https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/index.html (accessed 7.27.22). [Google Scholar]

- Leek J, Johnson W, Parker H, Fertig E, Jaffee A, Zhang Y, Storey J, Torres L, 2022. sva: Surrogate Variable Analysis. 10.18129/B9.bioc.sva [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yu N, Du L, Shi W, Yu H, Song M, Wei S, 2020. Transplacental Transfer of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Identified in Paired Maternal and Cord Sera Using Suspect and Nontarget Screening. Environ. Sci. Technol 54, 3407–3416. 10.1021/acs.est.9b06505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew Z, Goudarzi H, Oulhote Y, 2018. Developmental Exposures to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): An Update of Associated Health Outcomes. Curr. Environ. Health Rep 5, 1–19. 10.1007/s40572-018-0173-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Tan JYL, Teh AL, Lim IY, Liew SJ, Maclsaac JL, Chong YS, Gluckman PD, Kobor MS, Cheong CY, Karnani N, 2018. Cell type-specific DNA methylation in neonatal cord tissue and cord blood: a 850K-reference panel and comparison of cell types. Epigenetics 13, 941–958. 10.1080/15592294.2018.1522929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Eliot MN, Papandonatos GD, Kelsey KT, Fore R, Langevin S, Buckley J, Chen A, Lanphear BP, Cecil KM, Yolton K, Hivert M-F, Sagiv SK, Baccarelli AA, Oken E, Braun JM, 2022. Gestational Perfluoroalkyl Substance Exposure and DNA Methylation at Birth and 12 Years of Age: A Longitudinal Epigenome-Wide Association Study. Environ. Health Perspect 130, 37005. 10.1289/EHP10118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimovic J, Gordon L, Oshlack A, 2012. SWAN: Subset-quantile Within Array Normalization for Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome Biol. 13, R44. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano-Salgado CB, Casas M, Lopez-Espinosa M-J, Ballester F, Basterrechea M, Grimalt JO, Jiménez A-M, Kraus T, Schettgen T, Sunyer J, Vrijheid M, 2015. Transfer of perfluoroalkyl substances from mother to fetus in a Spanish birth cohort. Environ. Res 142, 471–478. 10.1016/j.envres.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni RE, Shah S, McRae AF, Chen BH, Colicino E, Harris SE, Gibson J, Henders AK, Redmond P, Cox SR, Pattie A, Corley J, Murphy L, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Feinberg AP, Fallin MD, Multhaup ML, Jaffe AE, Joehanes R, Schwartz J, Just AC, Lunetta KL, Murabito JM, Starr JM, Horvath S, Baccarelli AA, Levy D, Visscher PM, Wray NR, Deary IJ, 2015. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 16, 25. 10.1186/s13059-015-0584-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrary C, Fiorito G, Hernandez B, Polidoro S, O’Halloran AM, Hever A, Ni Cheallaigh C, Lu AT, Horvath S, Vineis P, Kenny RA, 2021. GrimAge Outperforms Other Epigenetic Clocks in the Prediction of Age-Related Clinical Phenotypes and All-Cause Mortality. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 76, 741–749. 10.1093/gerona/glaa286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura R, Araki A, Miyashita C, Kobayashi Sumitaka, Kobayashi Sachiko, Wang S-L, Chen C-H, Miyake K, Ishizuka M, Iwasaki Y, Ito YM, Kubota T, Kishi R, 2018. An epigenome-wide study of cord blood DNA methylations in relation to prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure: The Hokkaido study. Environ. Int 115, 21–28. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHANES 2009-2010: Polyfluoroalkyl Chemicals Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies [WWW Document], 2013. URL https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/2009-2010/PFC_F.htm#LBXPFNA (accessed 7.27.22). [Google Scholar]

- Nie L, Chu H, Liu C, Cole SR, Vexler A, Schisterman EF, 2010. Linear Regression With an Independent Variable Subject to a Detection Limit. Epidemiology 21, S17–S24. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181ce97d8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen G, Heiger-Bernays WJ, Schlezinger JJ, Webster TF, 2021. Predicting the Effects of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Mixtures on Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha Activity in Vitro (preprint). Pharmacology and Toxicology. 10.1101/2021.09.30.462638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Gudiel H, Eixarch E, Crispi F, Morán S, Zannas AS, Fañanás L, 2019. Prenatal adverse environment is associated with epigenetic age deceleration at birth and hypomethylation at the hypoxia-responsive EP300 gene. Clin. Epigenetics 11, 73. 10.1186/s13148-019-0674-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri-Siso D, Gonzalez JR, 2022. methylclock: Methylclock - DNA methylation-based clocks. 10.18129/B9.bioc.methylclock [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PFAS Explained [WWW Document], 2016. URL https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained (accessed 7.27.22).

- Rappazzo KM, Coffman E, Hines EP, 2017. Exposure to Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances and Health Outcomes in Children: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiologic Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 14, 691. 10.3390/ijerphl4070691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RC, Narala VR, Keshamouni VG, Milam JE, Newstead MW, Standiford TJ, 2008. Sepsis-induced inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis is mediated by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Blood 112, 4250–4258. 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling AP, Adgate JL, Hamman RF, Kechris K, Calafat AM, Dabelea D, 2019. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and infant growth and adiposity: the Healthy Start Study. Environ. Int 131, 104983. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling AP, Adgate JL, Hamman RF, Kechris K, Calafat AM, Ye X, Dabelea D, 2017. Perfluoroalkyl Substances during Pregnancy and Offspring Weight and Adiposity at Birth: Examining Mediation by Maternal Fasting Glucose in the Healthy Start Study. Environ. Health Perspect 125, 067016. 10.1289/EHP641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling AP, Liu C, Shen G, Yang IV, Kechris K, Borengasser SJ, Boyle KE, Zhang W, Smith HA, Calafat AM, Hamman RF, Adgate JL, Dabelea D, 2020. Prenatal Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, Umbilical Cord Blood DNA Methylation, and Cardio-Metabolic Indicators in Newborns: The Healthy Start Study. Environ. Health Perspect 128, 127014. 10.1289/EHP6888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez A, Lahti J, Czamara D, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Knight AK, Girchenko P, Hämäläinen E, Kajantie E, Lipsanen J, Laivuori H, Villa PM, Reynolds RM, Smith AK, Binder EB, Räikkönen K, 2018. The Epigenetic Clock at Birth: Associations With Maternal Antenatal Depression and Child Psychiatric Problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 57, 321–328.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suderman M, 2022. meffil. [Google Scholar]

- Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, Beck S, 2013. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics 29, 189–196. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triche TJ Jr, Weisenberger DJ, Van Den Berg D, Laird PW, Siegmund KD, 2013. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e90. 10.1093/nar/gkt090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Lindh CH, Fletcher T, Jakobsson K, Engström K, 2022. Perfluoroalkyl substances influence DNA methylation in school-age children highly exposed through drinking water contaminated from firefighting foam: a cohort study in Ronneby, Sweden. Environ. Epigenetics 8, dvac004. 10.1093/eep/dvac004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Liu AH, O’Connor GT, Pillai D, Kattan M, Misiak RT, Gruchalla R, Szefler SJ, Khurana Hershey GK, Kercsmar C, Richards A, Stevens AD, Kolakowski CA, Makhija M, Sorkness CA, Krouse RZ, Visness C, Davidson EJ, Hennessy CE, Martin RJ, Togias A, Busse WW, Schwartz DA, 2017. The Nasal Methylome and Childhood Atopic Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 139, 1478–1488. 10.1016/jjaci.2016.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XY, Wang LH, Chen T, Hodge DR, Resau JH, DaSilva L, Farrar WL, 2000. Activation of Human T Lymphocytes Is Inhibited by Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ (PPARγ) Agonists. J. Biol. Chem 275, 4541–4544. 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.