Abstract

Background

Disadvantaged populations (such as women from minority ethnic groups and those with social complexity) are at an increased risk of poor outcomes and experiences. Inequalities in health outcomes include preterm birth, maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, and poor-quality care. The impact of interventions is unclear for this population, in high-income countries (HIC). The review aimed to identify and evaluate the current evidence related to targeted health and social care service interventions in HICs which can improve health inequalities experienced by childbearing women and infants at disproportionate risk of poor outcomes and experiences.

Methods

Twelve databases searched for studies across all HICs, from any methodological design. The search concluded on 8/11/22. The inclusion criteria included interventions that targeted disadvantaged populations which provided a component of clinical care that differed from standard maternity care.

Results

Forty six index studies were included. Countries included Australia, Canada, Chile, Hong Kong, UK and USA. A narrative synthesis was undertaken, and results showed three intervention types: midwifery models of care, interdisciplinary care, and community-centred services. These intervention types have been delivered singularly but also in combination of each other demonstrating overlapping features. Overall, results show interventions had positive associations with primary (maternal, perinatal, and infant mortality) and secondary outcomes (experiences and satisfaction, antenatal care coverage, access to care, quality of care, mode of delivery, analgesia use in labour, preterm birth, low birth weight, breastfeeding, family planning, immunisations) however significance and impact vary. Midwifery models of care took an interpersonal and holistic approach as they focused on continuity of carer, home visiting, culturally and linguistically appropriate care and accessibility. Interdisciplinary care took a structural approach, to coordinate care for women requiring multi-agency health and social services. Community-centred services took a place-based approach with interventions that suited the need of its community and their norms.

Conclusion

Targeted interventions exist in HICs, but these vary according to the context and infrastructure of standard maternity care. Multi-interventional approaches could enhance a targeted approach for at risk populations, in particular combining midwifery models of care with community-centred approaches, to enhance accessibility, earlier engagement, and increased attendance.

Trial registration

PROSPERO Registration number: CRD42020218357.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12939-023-01948-w.

Keywords: Health inequality, Targeted intervention, High-income country, Midwife models, Interdisciplinary care, Community care, Disadvantage, Social complexity, Ethnic minority

Background

High-income countries (HICs) [1] have comparatively lower rates of maternal and perinatal mortality than low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); however, outcomes vary between and within countries [2]. Within the United Kingdom (UK), for example, there are differences in mortality, morbidity and experiences of maternity care [3–5]. Those living in the most deprived areas of the UK are more likely to experience a stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm birth and maternal mortality [6]. Also, the rate of stillbirth, neonatal mortality, and maternal mortality, are disproportionately higher for minority ethnic groups [6, 7]. These measurable differences in experience and outcomes are known as health inequalities, [8]. Health inequalities are avoidable and are the result of unequal distribution of resources, power, and income in society [9].

Some population groups at higher risk of health inequalities are often described in the literature as vulnerable or having social risk factors [10]. This is known to include women who experience multiple and severe social disadvantages, including but not limited to: homelessness, poverty, domestic violence, substance misuse, or those from minority ethnic groups [11]. Unlike LMICs, HICs have infrastructure, resources, and finances available, but are still failing populations that are disproportionately at risk of inequalities, and in some cases, the inequality gap has been widening [12]. Equally, it is also important to know which interventions work and to build on their strengths [13].

Health and social care interventions aim to improve the health and wellbeing of their targeted populations. Interventions range from: surgical and pharmacological, health promotion and education, immunisation campaigns, financial subsidies, and upskilling professionals and models of care [14]. Models of care are complex interventions, with various interacting components and mechanisms [15], and are commonly used in health and social care. However, universal interventions, targeting whole populations, are not ideal for addressing specific health inequalities and have also been shown to widen inequalities [14]. The Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England introduced the concept of ‘proportionate universalism’ [16] to this debate, suggesting that health actions must be universal, not targeted (to avoid stigmatisation), but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage.

There is evidence available for the benefits of healthy women receiving different models of maternity care interventions, for example, community-based [17] and midwife-led or doctor-led care [18, 19]. Some evidence of targeted interventions for vulnerable women has included different stages of maternity care, for example, antenatal programmes for women with social complexities or women living in deprived areas [20, 21] but few have included all areas of maternity care [21]. There is also a review of interventions which reduce health inequalities in LMICs [14], however there is no similar evidence for HICs. To date, there has not been a comprehensive review of targeted models of care interventions including all areas of maternity care (antenatal; intrapartum; postnatal) in HICs. This review aims to systematically identify and evaluate the current evidence available related to targeted health and social care interventions in HICs to reduce health inequalities experienced by disproportionately at-risk women and infants.

Methods

The protocol of this review was registered and published with PROSPERO (CRD42020218357) [22]. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Equity (PRISMA-E) reporting guidelines [23] (see additional file 1). A mixed-methods approach was taken to consider a breadth of research designs that included complex health and social interventions. This would allow for a comprehensive understanding of what works, what doesn’t work, how and in what contexts.

Search strategy and study selection

An electronic search strategy was undertaken using 12 health-related databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, MIDIRS, Global Health, BNI, Web of Science, CINAHL, CENTRAL, LILACS, AJOL, Global Index Medicus). Further to this JBI and other systematic reviews, national and international reports, dissertation and theses, grey literature, ISRCTN registry, PROPERO, Cochrane, and the Australian and the New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry were also searched. Lastly, a backward hand-search of bibliographies and reference lists of the included studies was also undertaken. The setting, perspective, intervention, comparison, and evaluation (SPICE) question framework was used to develop the research question and identify a complete list of keywords (see additional file 2) for the search.

Eligibility criteria were developed (see additional file 3). No study design, date of publication, or language restrictions were applied. The search included all HICs as defined by the 2019 World Bank Gross National Income (GNI) [1]. The population included childbearing women, newborns, and infants up to one year of age who are deemed by predetermined criteria [6, 11, 24, 25] as disproportionately impacted by health inequalities (see Table 1). The search for publications ended on 08/11/2022.

Table 1.

| Women who find services hard to access | Women needing multiagency services |

|---|---|

|

• Ethnic minority or Indigenous people • Socially isolated women • Those living in poverty/deprivation/who are homeless • Refugees/asylum seekers • Non-native language speakers • Victims of abuse • Sex workers • Young mothers • Unsupported mothers • Women within travelling communities (Gypsy, Traveller and Roma) |

• Women who are subject of safeguarding concerns • Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues • Women with physical/emotional and/or learning disabilities • Women who have been victims of female genital mutilation • Women who are HIV positive |

The intervention criteria were defined as any health or social care intervention which included clinical care as part of the programme or package of care, which was different from the setting's standard care. Standalone interventions (e.g., vouchers, supplements), interventions which did not include clinical care (peer support), adjuncts to existing care or any interventions that were not part of an overall programme or package of care (e.g., educational class), and well-established targeted interventions with existing Cochrane reviews (e.g., family nurse partnership, social support) [26–28]were excluded from this review.

Primary outcomes were maternal, perinatal, and infant mortality, and secondary outcomes included experiences and satisfaction, antenatal care coverage, access to care, quality of care, mode of delivery, analgesia use in labour, preterm birth, low birth weight, breastfeeding, family planning, immunisations (see additional file 4 for outcome definitions). Studies were included irrespective of whether the intervention had been identified as a success, to help meet the objectives of this review and understand what does, or does not, work. Inequality indicators (e.g., differences between sample groups based on sociodemographic, ethnicity, race, deprivation index, or others described by the authors of papers) were reported and discussed in relation to the outcomes.

Study selection, quality assessment and data extraction

Covidence was used to manage the screening and study selection process. All papers were screened by title and abstract by a first and second reviewer and any conflicts were discussed and agreed upon with a third reviewer. The methodological quality of included papers was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [29], as it offers assessment of quantitative (randomised, non-randomised, descriptive), qualitative and mixed methods design. The tool offers three response options: ‘Yes’ the criterion is met, ‘No’ the criterion is not met, and ‘Can’t tell’ when there is not enough information to judge. The updated 2018 version of MMAT [29] advises against scoring criteria as it does not provide enough detail, however if required scores are determined based on how many of the criteria is met. For example, ***** for 100%, **** 80%, *** 60%, ** 40%, * ≤ 20% of the “yes” criteria have been met. See Table 2 for overall MMAT scores. A pre-designed data extraction form was piloted and used to extract study characteristics and outcome data, initially in Covidence and then tabulated in Excel. Quality assessment and data extraction were assessed independently by a first and a second reviewer and any conflicts were discussed and consensus reached with a third reviewer.

Table 2.

Summary of studies included

| Author, Date | Country | Design | Population | Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Secondary Outcomes | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen 2016 [30] | Australia | Mixed methods | Young mothers | Midwifery models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care; Quality of care | b | |

| Alliman 2019 [31] | USA | Qualitative research | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Unsupported mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwife models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Family planning; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Analgesia use; Mode of birth; Access to care | a | |

| Alvarado 1999 [32] | Chile | Mixed methods | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless | Interdisciplinary care | Maternal mortality | Experience/ Satisfaction; Family planning; Breastfeeding; Access to care | e |

| Balaam 2018 [10] | UK | Qualitative research | Socially isolated women; Unsupported mothers; Women who are subject of safeguarding concerns | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction | a | |

| Barkauskas 2002 [33] | USA | Non-randomised studies |

Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Unsupported mothers; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues |

Midwifery models | Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth | c | |

| Bertilone, 2015 [34] | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Young mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Access to care | b | |

| Blanchette 1995 [35] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues; Ethnic minorities; Other: Low income uninsured and underinsured women in the USA | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Analgesia use; Mode of birth; Access to care | d |

| Campbell 2004 [36] | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Access to care; Quality of care | b | |

| Cunningham 2017 [37] | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Young mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction; Antenatal care coverage | d | |

| Filby 2019 [42[ | UK | Qualitative research | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction; Antenatal care coverage; Quality of care | a | |

| Grady 2004 [38] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Young mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | d | |

| Homer 2012 [39] | Australia | Mixed methods | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Access to care | a |

| Ip 2015 [40] | Hong Kong | Non-randomised studies |

Socially isolated women Young mothers; Unsupported mothers; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues |

Interdisciplinary care | Experience/Satisfaction | a | |

| Jan 2004 [41] | Australia | Mixed methods | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Unsupported mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Perinatal mortality | Experience/ Satisfaction; Low birth weight; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | b |

| Jones 2021 [42] | UK | Quantitative descriptive | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Young mothers; Unsupported mothers; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues | Midwifery models; Interdisciplinary care | Breastfeeding; Antenatal coverage; Access to care | c | |

| Kildea 2012 [43] | Australia | Mixed methods | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Interdisciplinary care; Community-centred | Experience/Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Analgesia use; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care; Quality of care | a | |

| Kildea 2019 [44] | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Socially isolated women; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Preterm birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | a | |

| Kildea 2021 [45] | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Analgesia use; Mode of birth; Antenatal coverage; Access to care | a | |

| Klerman 2001 [46] | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Ethnic minorities; Other: Medicaid women (low income families) | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Quality of care | c | |

| Lack 2016 [47] | Australia | Quantitative descriptive studies | Women who have been victims of female genital mutilation; Ethnic minorities; Other: Most communities are socio-economic disadvantaged and housing and infrastructure managed by government | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | b |

| Lenaway 1995 | USA | Non-randomised studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Other: recipients of Medicaid or the Colorado Indigent Care Program | Midwifery models | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Access to care | b | |

| Liu 2017 [48] | USA | Mixed methods | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction | d | |

| Madeira 2019 [49] | USA | Mixed methods | Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction | b | |

| Malebranche 2020 [50] | Canada | Non-randomised studies | Refugees/asylum seekers | Interdisciplinary care | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Quality of care | a | |

| McAree 2010 [51] | UK | Qualitative research | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/Satisfaction | a | |

| Mersky 2021 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless | Community-centred | Breastfeeding | d | |

| Middleton 2017 [52] | Australia | Mixed methods | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Young mothers; Unsupported mothers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | a | |

| Morris 2012 [53] | Australia | Qualitative research | Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues | Interdisciplinary care | Experience/Satisfaction | a | |

| Nel 2003 [54] | Australia | Quantitative descriptive studies | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Maternal mortality | Antenatal care coverage | e |

| Owens 2016 [55] | Australia | Qualitative research | Refugees/asylum seekers; Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Experience/Satisfaction | a | |

| Panaretto 2005 | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Community-centred | Perinatal mortality | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care; Quality of care | c |

| Piechnik 1985 [56] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Young mothers; Ethnic minorities | Interdisciplinary care | Maternal mortality; Perinatal mortality | Family planning; Breastfeeding; Immunisation; Mode of birth | c |

| Quelly 2021 [57] | USA | Quantitative descriptive studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Other: recipients of Medicaid | Interdisciplinary care | Low birth weight; preterm birth; Antenatal coverage; Access to care | d | |

| Quinlivan 2003 [58] | Australia | Randomised controlled trial | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Young mothers; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality | Family planning; Breastfeeding; Immunisation; Mode of birth; Access to care | c |

| Reeve 2016 [59] | Australia | Non-randomised studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Interdisciplinary care; Community-centred | Perinatal mortality | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | c |

| Reguero 1994 [60] | USA | Quantitative descriptive studies | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues; Ethnic minorities | Interdisciplinary care; Community-centred | Infant mortality | d | |

| Robertson 2009 [61] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Preterm births; Mode of birth | e | |

| Ross 1981 [62] | USA | Quantitative descriptive studies | Ethnic minorities; Other: Indian American tribe | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality | Preterm birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | d |

| Rutman 2020 [63] | Canada | Mixed methods | Socially isolated women; Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Victims of abuse; Young mothers; Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues | Interdisciplinary care | Experience/ Satisfaction; Access to care | e | |

| Smoke 1988 [64] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Young mothers | Midwifery models; Interdisciplinary care | Family planning; Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Analgesia use; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | a | |

| Stapleton 2013 [65] | Australia | Mixed methods | Socially isolated women; Refugees/asylum seekers; Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models; Interdisciplinary care | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Preterm birth; Mode of birth | d | |

| Tandon 2013 [66] | USA | Non-randomised studies | Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Antenatal care coverage | b | |

| Trudnak 2017 | USA | Non-randomised studies | Non-native language speakers; Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Breastfeeding; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Access to care | b | |

| Turner 2000 [67] | USA | Quantitative descriptive studies | Women who are HIV positive | Interdisciplinary care | Experience/Satisfaction; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Access to care; Quality of care | c | |

| Wiggins 2005 [68] | UK | Randomised controlled trial | Those living in poverty/ deprivation/ who are homeless; Non-native language speakers | Midwifery models | Experience/ Satisfaction; Breastfeeding; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | c | |

| Wong 2011 [69] | Australia | Quantitative descriptive studies | Ethnic minorities | Midwifery models | Perinatal mortality; Infant mortality | Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Mode of birth; Antenatal care coverage; Access to care | a |

“yes” criteria have been met

a for 100%,

b for 80%,

c for 60%,

d for 40%,

e for ≤ 20% of MMAT

The quality of each study was evaluated against two screening questions and five further questions relating to their design, unless they were of mixed method designs in which case they had a further fifteen questions.

Data analysis

Due to the wide variations in research designs, intervention types and outcomes a meta-analysis could not be performed. Instead, results are presented narratively and organised based on the interpreted intervention types.

Results

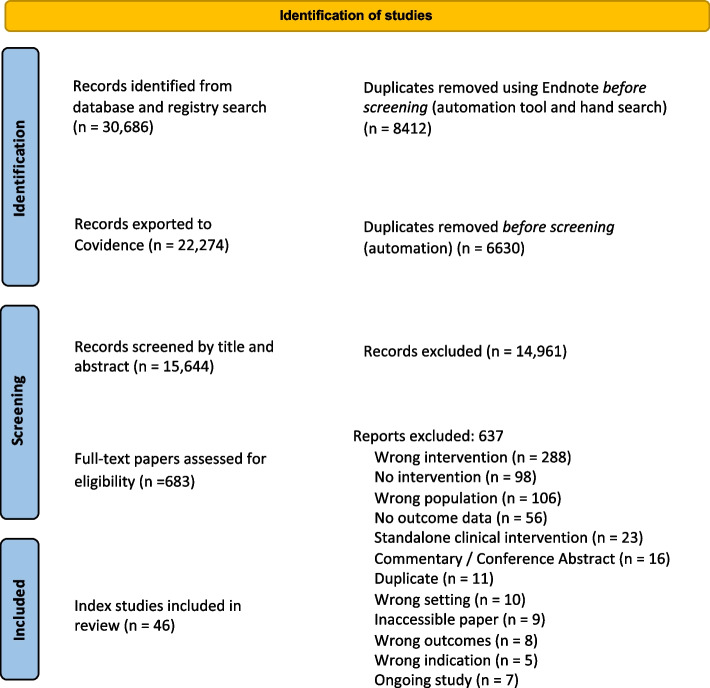

The initial database and hand search resulted 30,686 references. After duplicates were removed, 15,644 papers were screened by title and abstract, and 683 full text papers were screened for inclusion. Finally, 53 papers were included, some of which were merged with their index papers, resulting in 46 studies included in the review (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Methodological characteristics and quality of included studies

The 46 included index studies varied in assorted methodological design: mixed methods (n = 10), qualitative (n = 6), quantitative randomised control trial (n = 5), quantitative non-randomised (n = 17), quantitative descriptive (n = 8). The high-income countries included Australia (n = 18 + 3 sibling papers), Canada (n = 2), Chile (n = 1), Hong Kong (n = 1), UK (n = 5) and USA (n = 19 + 4 sibling papers). From the disadvantaged population groups (see Table 1) all were identified except 3 categories (sex workers; travelling communities; physical/emotional/learning disabilities) (see Table 3). Categories of population groups were not homogenous and often intersected demonstrating multiple disadvantages. The earliest study was published in 1981 and the most recent study was published in 2021. No study was excluded based on their score as recommended by MMAT tool.

Table 3.

Populations studied across interventions

| Population characteristics | Midwifery models | Interdisciplinary care | Community-centred |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socially isolated women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Living in poverty/deprivation or homeless | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Refugees/asylum seekers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Non-native language speakers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Victims of abuse | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sex workers | |||

| Young mothers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Unsupported mothers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Women within travelling communities | |||

| Safeguarding concerns | ✓ | ||

| Women with substance/alcohol abuse issues | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Physical/emotional/learning disabilities | |||

| Victims of female genital mutilation | ✓ | ||

| Women who are HIV positive | ✓ | ||

| Ethnic minorities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Interventions

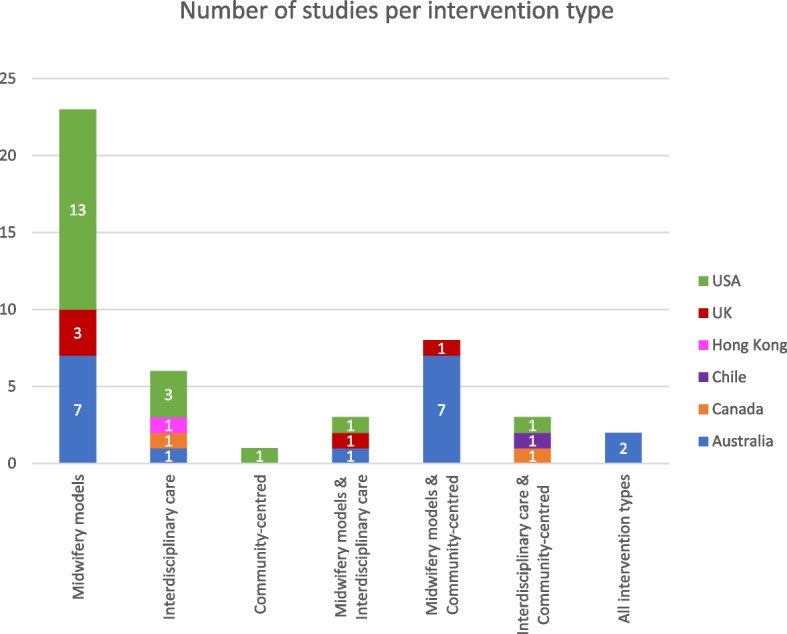

Upon narrative synthesis [70] three principal interventions were identified: midwifery models of care; interdisciplinary care; and community-centred services. The principal interventions were synthesised by grouping common features of the interventions such as, how they were delivered, the main clinician, and how they were managed and organised. The interventions were not mutually exclusive, and in some studies a multi-intervention approach was taken (see Fig. 2), combining with another intervention type. Two studies [43, 59] combined all three intervention categories.

Fig. 2.

Number of studies per intervention type

Midwifery models of care took an interpersonal and holistic approach as they focused on continuity of carer, home visiting, culturally and linguistically appropriate care and accessibility (financial and geographic). For example, studies in this intervention type considered interpersonal relationships between women, including families and communities, and the health care professional who was typically a midwife, or similarly qualified depending on the context. Some studies also considered wider relationships in group antenatal care settings. Qualitative results strongly suggested the importance of interpersonal relationships in women’s overall experiences. Interdisciplinary care took a structured approach, to coordinate care between different health and social care services for women. Studies which researched this intervention predominantly focused on complexities such as HIV, substance and/or alcohol misuse, and those living in deprivation, as they required multi-agency services. Community-centred services took a community-based approach with interventions that suited the need of its community and their specific norms, particularly ethnic minority populations or those with non-native language speaking ability. Studies based in Australia also included community members and/or health care practitioners from the same ethnic/cultural background as the population, which was overall positively evaluated. Most community-centred interventions were multi-interventional combining with predominantly midwifery models of care and in some instance interdisciplinary care.

Results are presented in three sections based on each intervention, rather than just primary and secondary outcomes. The purpose of this is to help readers understand the specificity of intervention types, followed by outcome indicators and patterns across contexts.

Midwifery models of care

Midwifery models of care were defined by the review team as interventions with midwives, or those similarly qualified based on the setting, as the central care providers or coordinators of care. There is often continuity from the care provider, and/or care is shared in a caseload. Midwifery models can also include shared care between a midwife and a primary physician or general practitioner, who is available for escalation and/or also provides regular care. The format of antenatal care is either individual or in a group a group setting. Overall, 36 studies incorporated midwifery models of care interventions. Countries included Australia (n = 17), UK (n = 5) and USA (n = 14). This intervention was the most frequently reported. Twenty-three studies were exclusively midwifery models of care studies [10, 30, 31, 33, 35, 37–39, 44, 46–49, 51, 54, 58, 61, 62, 66, 68, 69, 71–73]. Three studies combined midwifery models and interdisciplinary care interventions [42, 64, 65], whereas eight studies combined midwifery models with community-centred services [34, 36, 41, 42, 45, 52, 55, 74]. Two studies combined all three interventions [43, 59].

Primary outcomes

Maternal mortality was reported in one study’s intervention as lower [54]. Perinatal mortality (stillbirth or neonatal death) was reported in nine studies, either as not statistically significant [41, 62, 74], lower in the intervention group [58], or reported without a comparator making it difficult to draw conclusions [35, 39, 47, 58, 59, 69]. Infant mortality was reported in one study [69].

Secondary outcomes

Twenty studies included results of participants experiences which were overall positive. Frequently cited reasons for positive experiences included feeling informed and having information explained [31, 36, 41, 46, 49, 51, 55], having more time in their appointments [31, 36, 41, 46, 66] and better access to their midwife [41, 71], having trust and being treated with respect [10, 31, 36, 39, 41, 48, 49, 71] as well as family centred social support [10, 30, 31, 41, 55]. Women also valued knowing who their care provider was [30, 36, 51], and particularly appreciated continuity of care from their midwife [39, 41, 43, 51, 65, 71]. In addition to this, women emphasised the value of receiving care from a midwife similar to their ethnic background [52] or a bilingual practitioner [48, 66]. Care in a community and/or group setting was viewed positively [39, 48, 49, 51, 61, 66] especially by adolescent groups [30, 37, 38] as they enjoyed interacting with others in similar situations to them therefore feeling less isolated. However, some did not find care in a group culturally appropriate [68] and some non-health community settings, such as immigration accommodation centre, were not fit for purpose but outside the control of maternity services [71].

There was increased knowledge and use of contraception in the intervention groups [31, 58] and also a variety of contraception methods were utilised [64]. Breastfeeding rates were frequently higher in the intervention groups [31, 33, 36, 38, 39, 42, 45, 52, 64, 68], in some instances similar or no differences were reported [43, 58, 61, 65]. One study reported no differences in immunisation knowledge or uptake [58].

There were lower rates of preterm birth [31, 34, 38, 44–47, 62, 64, 69, 72, 74] and low birth weight [31, 34, 38, 47, 64, 69, 72], however, some studies found no difference or no statistical significance for preterm birth [33, 35, 39, 43, 52, 59, 65, 73] rates and low birth weight [33, 35, 39, 41, 43, 52, 59, 73, 74]. Some reasons for lack of significance included small sample sizes.

Overall, mode of birth was positively reported with higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth [43, 58, 61, 65, 73] and lower rates of caesarean Sect. [31, 33, 35, 43, 45, 46, 58, 69, 73] in the intervention groups. Again, in some instances study findings showed no significant differences [34, 38, 47, 59, 64, 72]. It was also noted that there was less use of epidural analgesia in the intervention groups [35, 43, 45]. Intervention groups were found to have earlier first-trimester appointments [30, 31, 34, 39, 41, 43, 44, 47, 52, 58, 59, 62, 69, 74] and higher rates of antenatal care coverage [30, 41–46, 52, 54, 62, 64, 69, 74]. They were also more likely to accept referrals [30] and have a documented care plan [74].

Patterns in countries

Midwifery models of care interventions were the most cited intervention type with three subgroups: continuity of care, shared care and group antenatal care. From the countries included in this review, Canada, Chile and Hong Kong did not incorporate midwifery models of care interventions. Australian studies often combined this intervention with community-centred service interventions and were predominantly targeting Aboriginal communities [34, 36, 41, 43, 45, 52, 55, 59, 74]. In this context, the specific model included continuity of care by a midwife and/or shared care with a doctor (general practitioner or obstetrician). Continuity of care was also implemented in the USA and UK interventions either by a midwife or certified nurse-midwife [10, 33, 46, 51, 62, 71]. Group antenatal care provided by midwives in the USA and Australia were targeting either adolescent pregnancies [30, 37, 38] or ethnic minority populations [48, 49, 61, 73].

Interdisciplinary care

Interdisciplinary care interventions were defined as care requiring multi-service involvement, whereby care is provided by a range of health and/or social care professionals, beyond the services of standard care. Overall, fourteen studies incorporated interdisciplinary care interventions and professionals included midwives, obstetricians, nurses, paediatricians, social workers, psychologists, dieticians, nutritionists and pharmacists. Countries included Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 2), Chile (n = 1), Hong Kong (n = 1), UK (n = 1) and USA (n = 5). Three studies combined interdisciplinary care with midwifery models of care [42, 64, 65], three studies with community-centred services [32, 60, 63], and two studies combined all three intervention groups [43, 59]. Six studies were exclusively interdisciplinary care interventions [40, 50, 53, 56, 57, 67].

Primary outcomes

Four studies reported primary outcomes [32, 56, 59, 60]. One study [32] reported one maternal mortality from the intervention group, however there was no further statistical analysis regarding significance. Two studies reported perinatal mortality, one of which reported lower rates in the intervention group [56], however the other study [59] was not statistically significant. One study [60] reported infant mortality decreased, however this could not be directly linked to the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Seven studies [32, 40, 43, 53, 63, 65, 67] included experiential outcomes. Overall, intervention groups reported higher levels of satisfaction [32, 40, 43, 65, 67], citing reasons as having time to ask questions, continuity, being treated with respect. However, women were disappointed with the lack of continuity in labour and the postnatal period [43, 65], and reported some staff imposing control over their care [53, 65]. Higher rates of antenatal care coverage and of first-trimester initial appointments were reported in the intervention groups [42, 43, 57, 59, 64], however one study found that the intervention group of asylum-seeking women took significantly longer to present and attended less visits [50].

Higher rates of vaginal birth and lower caesarean section rates were found in the intervention [43, 64, 65] but in some cases findings were not significant in certain studies [50, 56, 59]. Use of epidural analgesia was lower in one [43] instance but higher in another [56]. Preterm birth rates varied, as they were lower in some intervention groups [64, 65, 67], not statistically significant in others [43, 59] and in one retrospective study noted as higher than the national average [50]. Lower rates of low birth weight were reported in the intervention groups in four studies [43, 56, 64, 67] and in one study were not statistically significant [59].

Three studies noted higher rates of breastfeeding in the intervention groups [32, 42, 64], however another two studies reported similar rates [43, 65]. Intervention groups were noted to use a wider range of postnatal contraceptives compared to comparison groups [32, 64]. Contraception initiation in one study [32] was similar in the intervention and comparison group. Reasons for higher rates of no contraception use in the intervention group were because of not having a current partner and therefore not required. There was no immunisation data for interdisciplinary care models.

Patterns in countries

Interdisciplinary care interventions were the second most common intervention type found in this review and the only intervention type found for Hong Kong (n = 1). Outcomes varied between interventions therefore it is difficult to conclude any patterns. Types of health and social care professionals varied between studies and were specific to the population needs. For example, three studies [53, 60, 63] targeted women with substance misuse however they all had different professionals address these needs from obstetricians to counsellors. Having said that, both midwives and doctors (obstetrician, general physician and/or paediatrician) were the primary professionals cited as part of the interdisciplinary care interventions.

Community-centred services

Community-centred service interventions were defined as services that were addressing the specific needs of their population and/or implementing a public health model in a community setting. Overall, fourteen studies incorporated community-centred interventions and countries included Australia (n = 9), Canada (n = 1), Chile (n = 1), UK (n = 1) and USA (n = 2). This intervention was not implemented independently in any of the 14 studies. Almost all community-centred interventions were in combination with another intervention type (midwifery model or interdisciplinary care), except for one study in the USA [75]. Combined midwifery models of care and community-centred services were reported in eight studies [34, 36, 41, 45, 52, 55, 71, 74]. Combined interdisciplinary care and community-centred services were reported in three studies [32, 60, 63]. Two studies combined all three interventions [43, 59].

Primary outcomes

Five studies [32, 41, 59, 60, 74] reported primary outcomes. One study reported one maternal mortality [32] but again did not state statistical significance. Perinatal mortality was reported by three studies [41, 59, 74] none of which were statistically significant. Neonatal mortality reported by one study [60] found a reduction in mortality over a two-year period however it was unclear if it was a direct result of the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Eight studies [32, 36, 41, 43, 52, 55, 63, 71] included qualitative data about experiences. Participants reported positive experiences and high levels of satisfaction with the respective interventions. Six of these interventions, (Australia n = 5, UK n = 1), combined a midwifery model of care with a community-centred service and their recurring themes included trust, continuity of midwifery care, family-centred approaches, clarity of information shared and culturally appropriate care. The UK study [71] which was centred around an initial accommodation centre, reported negatively on the accommodation centre and its facilities rather than care provided.

Lower rates of low birth weight were reported in the intervention groups [43, 52, 59], however not all were statistically significant findings [34, 41, 74]. Preterm birth rates were also notably lower [34, 43, 45, 52, 59, 74]. Intervention group were more likely to have non-instrumental vaginal birth and have lower rates of caesarean section, along with lower rates of epidural analgesia use [43, 45]. In the intervention groups there were higher rates of first-trimester initial appointments and higher rates of antenatal care coverage [34, 41, 45, 52, 59, 74]. However, one study [43] had lower rates of timely first-trimester attendance due to delays in processes, furthermore, inadequate referral pathways meant some women were not allocated to eligible services. Breastfeeding rates were higher in intervention groups [32, 45, 52, 75].No data were reported regarding immunisations in the community-centred services interventions.

Patterns in countries

All community-centred service interventions were delivered either in the community setting solely or in combination with the hospital setting. The Australian interventions were predominantly in partnership with the community and frequently included a person of the same Aboriginality to deliver the service, such as a midwife, health worker, peer supporter or obstetrician. Two Australian studies combined all three interventions [43, 59] and targeted Aboriginal communities. Both studies provided midwifery-led continuity of care to women in their community setting and were delivered in partnership with the community health services. One Canadian [63], one Chilean study [32] and one USA study [60] combined interdisciplinary care with community-centred services and primarily targeted those living in deprivation and those with substance misuse issues. They both incorporated a range of practitioners, including physicians, paediatricians, counsellors, and substance misuse services, and were accessible in the local community to target hard-to-reach communities.

Discussion

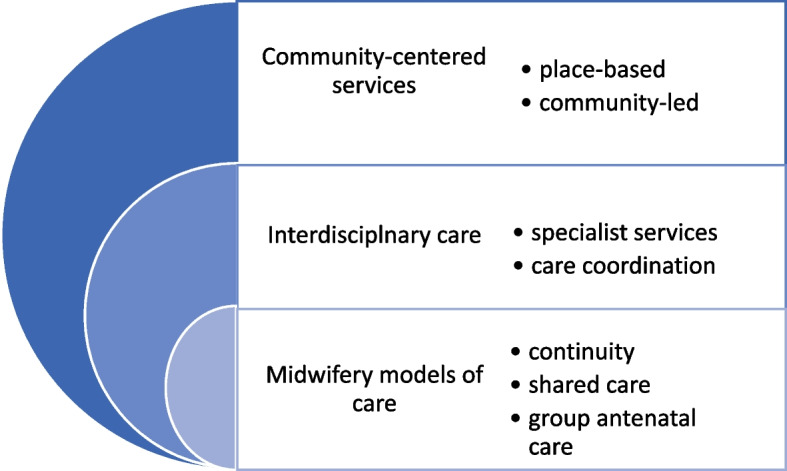

This review systematically gathered and analysed the available evidence related to targeted health and social care interventions that have potential to reduce maternal and infant health inequalities in high-income countries. This review found 46 studies, that met the inclusion criteria, from a range of six high-income countries (Australia, Canada, Chile, Hong Kong, UK and USA) spanning from 1981 to 2021, using a variety of study designs. Interventions were implemented at different stages of maternity care including the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal period. Some study interventions included a comparator in the form of a control group, retrospective clinical data, or national data whereas other studies had no comparator. Intervention types varied within countries/settings and between countries however, three principal intervention types were identified: midwifery models of care, interdisciplinary care and community-centred services. The intervention groups formed an order (see Fig. 3) based on the level of intervention but also, spontaneously, based on how frequently they were reported in this review.

Fig. 3.

Stacked Venn diagram illustrating intervention types

The primary outcomes demonstrate that maternal, perinatal and/or neonatal mortality were positively impacted in some instances however they were often not statistically significant due to methodological limitations. Secondary outcomes were positively associated with interventions such as earlier access to care, more than four antenatal visits coverage, mode of birth (decreased caesarean-section, and increased vaginal birth), use of postnatal contraception, increased breastfeeding rates. However, statistical significance of results was sporadic or not consistently reported so difficult to establish causality.

This review focused on interventions with a clinical component of care to identify which models and programmes of care have been tested. However, the review did not include interventions with strong existing evidence for vulnerable populations, such as, family-nurse partnerships [26] and social support [27, 28] as it would not add to the body of evidence. Yet, it did include continuity of care and group antenatal care because there is not a good quality evidence available specifically for women at disproportionate risk of health inequalities.

The findings of this review suggest that existing interventions can help mitigate health inequalities in at risk populations and these are adaptable in different HIC contexts. For example, in settings where care from a midwife is not the standard it can help improve women’s experiences of maternity care and encourage early attendance and increase antenatal coverage. Furthermore, in settings where midwife-led care is the standard, continuous continuity from a midwife or team of midwives can also improve women’s experiences and feelings of satisfaction. When continuity is not provided throughout the maternity journey it leads to lower levels of satisfaction. This demonstrates that the professional group providing care is of importance to women, as it facilitates relationship building. Additionally, this review has also identified that care from those of similar background, as well as care in a group with those in similar situations (particularly adolescence) are important to women and helps relieve feelings of isolation. Overall, care from a midwife, or similarly qualified, is shown to positively impact primary or secondary outcomes in HICs and is therefore an important intervention to consider.

Women at higher risk of inequalities often require input from multiple agencies and clinical professionals [6]. This review found that input of specialist services, in coordination with maternity care, such as counselling for substance misuse, can be an effective intervention to improve engagement and utilisation of primary health services, and promote healthier choices. The findings also emphasise that for women requiring multiagency support, care coordinated by a midwife can facilitate improved experiences and overall quality of care.

This review recognised that community-based interventions, when combined with midwifery models or interdisciplinary care, can maximise the benefits of the intervention to promote health equality. Place-based care in the community is known to improve outcomes [21, 76] and this review supports this. Furthermore, this review adds to the evidence of social support but more specifically support within communities and community-controlled health services that are culturally specific.

The strength of this review is that it systematically searched a breadth of literature to identify the maximum number of studies across HICs with targeted interventions. This review also considered key primary and secondary outcomes to fully understand the potential impact of interventions. The limitations of this review is that the methodologically quality of studies included varied, yet no study was excluded based on their quality assessment in accordance with MMAT recommendations [29].

Conclusion

Health and social models and programmes of care are complex interventions. This review identified that existing targeted interventions are overall positively associated with improved outcomes. However, they are of varying statistical significance, and impact across countries and contexts. Importantly, this review identified that multi-interventional approaches could enhance a targeted approach for those disproportionately at risk of health inequalities and experiencing multiple health and social disadvantages. Including community-centred approaches that are place-based and/or combined with hospital-based care can enhance accessibility, earlier engagement, and increased attendance. Midwife-led care is highly reported across settings and this review highlights that the holistic nature of midwifery care is highly valued by at risk women and can better facilitate care coordination for women with complex multiagency needs. Further to this, Australian based studies demonstrate that it is valuable to indigenous and minority ethnic groups to include health workers (midwife, support workers or health officers) from similar backgrounds to the local community as this enhances culturally competent care.

The findings of this review are applicable in HICs and their distinctive contexts, including variations in health financing and populations at disproportionate risk of health inequalities. This review can help inform policy makers understand which outcomes are positively associated with certain intervention types and recognise how to enhance already existing interventions which will fit within their health systems. This review did not intend to evaluate the interventions and nor would the included studies allow that, because they did not all consistently report the same level of detail. Future research should include detail of the intervention and theories of change so we can better understand how these interventions were implemented, mechanisms underlying the outcomes and whether interventions were delivered as intended. Future research would also benefit from comparative statistical analysis of the intervention and control groups for better interpretation of results. It will also be beneficial to research effectiveness of interventions separately from studies reporting experiences alone.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 3. Inclusion-Exclusion criterion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge Fahimah Ali and Tommaso Squeri for initial contributions to screening of papers.

Authors’ contributions

Z.K. led the systematic review, was the first reviewer, developed and undertook the search strategy, and analysed and organised the data. C.FT. and Z.V. acted as the second reviewer and J.S. acted as third reviewer to resolve any conflicts during screening. Z.K., Z.V., C.F T., H.R J., A.M., H.S., E.M., L.B., N.VW., A.E. participated in the screening of papers. Z.K., Z.V., C.F T., H.R J., L.B., E.M. participated in data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies. Z.K. wrote the manuscript and prepared tables, figures, appendices and supplementary files. All authors named provided their expertise in reviewing the final manuscript and content. Z.B. provided contributions as a Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement member. The review will contribute to Z.K.’s PhD thesis and J.S., S.H., C.F T., H.RJ. supervised Z.K. for this purpose.

Funding

JS is an Emeritus NIHR Senior Investigator and with ZK, ZV, CFT, HRJ, AE and SAS (King’s College London) are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. JS is an NIHR Senior Investigator and Head of Midwifery and Maternity Research at NHS England. JS and CFT are supported by a NIHR Global Health Research Group (NIHR133232) and CFT is supported by a NIHR Development and Skills Award (NIHR301603).

Availability of data and materials

All related files have been attached to the submission as appendices or supplementary files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/a

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript and consent to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zahra Khan, Email: zahra.khan@kcl.ac.uk.

Zoe Vowles, Email: zoe.vowles@kcl.ac.uk.

Cristina Fernandez Turienzo, Email: cristina.fernandez_turienzo@kcl.ac.uk.

Zenab Barry, Email: zenabbarry@gmail.com.

Lia Brigante, Email: lia.brigante@rcm.org.uk.

Soo Downe, Email: sdowne@uclan.ac.uk.

Abigail Easter, Email: abigail.easter@kcl.ac.uk.

Seeromanie Harding, Email: seeromanie.harding@kcl.ac.uk.

Alison McFadden, Email: a.m.mcfadden@dundee.ac.uk.

Elsa Montgomery, Email: elsa.montgomery@kcl.ac.uk.

Lesley Page, Email: lesley.page@kcl.ac.uk.

Hannah Rayment-Jones, Email: hannah.rayment-jones@kcl.ac.uk.

Mary Renfrew, Email: m.renfrew@dundee.ac.uk.

Sergio A. Silverio, Email: sergio.silverio@kcl.ac.uk

Helen Spiby, Email: helen.spiby@nottingham.ac.uk.

Nazmy Villarroel-Williams, Email: n.villarroel-williams@shu.ac.uk.

Jane Sandall, Email: jane.sandall@kcl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Cited 8 Mar 2023

- 2.Moller AB, Patten JH, Hanson C, Morgan A, Say L, Diaz T, et al. Monitoring maternal and newborn health outcomes globally: a brief history of key events and initiatives. Trop Med Int Health 2019;24(12):1342–68. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tmi.13313. Cited 21 Aug 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Khan Z. Ethnic health inequalities in the UK’s maternity services: a systematic literature review. Br J Midwifery. 2021;29(2):100–107. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2021.29.2.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, Patel R, Shakespeare J, Kotnis R, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care - lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2017–19. Oxford; 2021. Available from: www.hqip.org.uk/national-programmes. Cited 21 Aug 2022

- 5.Draper ES, Gallimore ID, Smith LK, Fenton AC, Kurinczuk JJ, Smith PW, et al. MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Mortality Surveillance Report, UK Perinatal Deaths for Births from January to December 2019. Leicester; 2021. Available from: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/perinatal-surveillance-report-2019/MBRRACE-UK_Perinatal_Surveillance_Report_2019_-_Final_v2.pdf. Cited 21 Aug 2022

- 6.Hadebe R, Seed PT, Essien D, Headen K, Mahmud S, Owasil S, et al. Can birth outcome inequality be reduced using targeted caseload midwifery in a deprived diverse inner city population? A retrospective cohort study, London, UK. BMJ Open 2021;11(11):e049991. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/11/e049991. Cited 4 Nov 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Banerjee A, Cox P, Cross-Sudworth F, et al. A national cohort study and confidential enquiry to investigate ethnic disparities in maternal mortality. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;43:101237. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2589537021005186/fulltext. Cited 2 Feb 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int. 1991;6(3):217–28. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapro/article/6/3/217/742216. Cited Aug 21 2022

- 9.CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva; 2008 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43943/9789241563703_eng.pdf;jsessionid=296851C300AC7C52CCAEC86EB5D550BC?sequence=1. Cited 21 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Balaam MC, Thomson G. Building capacity and wellbeing in vulnerable/marginalised mothers: a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2018;31(5):e341–e347. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NICE. Pregnancy and complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. 2010. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg110/chapter/Introduction. Cited 5 Aug 2022 [PubMed]

- 12.Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, Goldblatt P, Morrison J. Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. London; 2020. Available from: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/marmot-review-10-years-on. Cited 21 Aug 2022

- 13.Zimmerman MA, Behav HE. Resiliency theory: a strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health 1 HHS public access author manuscript. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):381–383. doi: 10.1177/1090198113493782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan B, Målqvist M, Trygg N, Qian X, Ng N, Thomsen S. What interventions are effective on reducing inequalities in maternal and child health in low- and middle-income settings? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–14. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-634. Cited 21 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2021;25(57):1–132. doi: 10.3310/hta25570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot M. Fair Society, healthy lives: the marmot review. Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. Institute of Health Equity; 2010.

- 17.Perry M, Becerra F, Kavanagh J, Serre A, Vargas E, Becerril V. Community-based interventions for improving maternal health and for reducing maternal health inequalities in high-income countries: A systematic map of research. Global Health. 2015;10(1):1–12. Available from: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-014-0063-y. Cited 21 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Sutcliffe K, Caird J, Kavanagh J, Rees R, Oliver K, Dickson K, et al. Comparing midwife-led and doctor-led maternity care: a systematic review of reviews. J Adv Nurs 2012;68(11):2376–86. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22489571/. Cited 21 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004667. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Origlia P, Jevitt C, Sayn-Wittgenstein F zu, Cignacco E. Experiences of antenatal care among women who are socioeconomically deprived in high-income industrialized countries: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017 62(5):589–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28763167/. Cited 21 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Rayment-Jones H, Dalrymple K, Harris J, Harden A, Parslow E, Id TG, et al. Project20: Does continuity of care and community-based antenatal care improve maternal and neonatal birth outcomes for women with social risk factors? A prospective, observational study. Plos One. 2021;16:0250947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250947.t001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan Z, Fernandez Turienzo C, Downe S, Easter A, McFadden A, Page L, et al. Health and social care interventions to reduce maternal, newborn and infant health inequalities in high-income countries: a systematic review. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020218357. PROSPERO. 2020. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=218357. Cited 22 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Welch V, Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Moher D, O’Neill J, Waters E, et al. PRISMA-equity 2012 extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012 9(10):e1001333. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333. Cited 6 Jul 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Rayment-Jones H, Harris J, Harden A, Khan Z, Sandall J. How do women with social risk factors experience United Kingdom maternity care? A realist synthesis. Birth. 2019 46(3):461–74. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/birt.12446. Cited 5 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hollowell J, Oakley L, Vigurs C, Barnett-Page E, Kavanagh J, Oliver S. Increasing the early initiation of antenatal care by black and minority ethnic women in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and mixed methods synthesis of women’s views and the literature on intervention effectiveness. Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2012.

- 26.Robling M, Bekkers MJ, Bell K, Butler CC, Cannings-John R, Channon S, et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-led intensive home-visitation programme for first-time teenage mothers (Building Blocks): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;387(10014):146–55. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S014067361500392X/fulltext. Cited 22 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hodnett E, Fredericks S, Weston J. Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000198. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10796178. Cited 22 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.East CE, Biro MA, Fredericks S, Lau R. Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk of low birthweight babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(4). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000198.pub3/full. Cited 22 Aug 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018: user guide. McGill: Montreal, QC, Canada,. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada; 2018. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/. Cited 27 Aug 2022

- 30.Allen J, Kildea S, Stapleton H. How optimal caseload midwifery can modify predictors for preterm birth in young women: Integrated findings from a mixed methods study. Midwifery. 2016;41:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alliman J, Stapleton SR, Wright J, Bauer K, Slider K, Jolles D. Strong Start in birth centers: Socio-demographic characteristics, care processes, and outcomes for mothers and newborns. Birth. 2019;46(2):234–243. doi: 10.1111/birt.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alvarado R, Zepeda A, Rivero S, Rico N, López S, Díaz S. Integrated maternal and infant health care in the postpartum period in a poor neighborhood in Santiago Chile. Stud Fam Plann. 1999;30(2):133–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barkauskas VH, Low LK, Pimlott S. Health outcomes of incarcerated pregnant women and their infants in a community-based program. Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47:371. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertilone C, McEvoy S. Success in closing the gap: favourable neonatal outcomes in a metropolitan aboriginal maternity group practice program; success in closing the gap: favourable neonatal outcomes in a metropolitan aboriginal maternity group practice program. Med J Austr. 2015;203(6):262. doi: 10.5694/mja14.01754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanchette H. Comparison of obstetric outcome of a primary-care access clinic staffed by certified nurse-midwives and a private practice group of obstetricians in the same community. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(6):1864–1871. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell S, Brown S. Maternity care with the women’s business service at the Mildura aboriginal health service. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2004.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham SD, Grilo S, Lewis JB, Novick G, Rising SS, Tobin JN, et al. Group prenatal care attendance: determinants and relationship with care satisfaction. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(4):770–776. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grady MA, Bloom KC. Pregnancy outcomes of adolescents enrolled in a centering pregnancy program. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(5):412–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2004.tb04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homer CSE, Foureur MJ, Allende T, Pekin F, Caplice S, Catling-Paull C. ‘It’s more than just having a baby’ women’s experiences of a maternity service for Australian aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Midwifery. 2012;28(4):e509–e515. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ip LS, Chau JPC, Thompson DR, Choi KC. An evaluation of a nurse-led comprehensive child development service in Hong Kong. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2015;33(1):88–98. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2014.970150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jan S, Conaty S, Hecker R, Bartlett M, Delaney S, Capon T. An holistic economic evaluation of an Aboriginal community-controlled midwifery programme in Western Sydney. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2004;9:14. doi: 10.1258/135581904322716067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones SW, Darra S, Davies M, Jones C, Sunderland-Evans W, Ward MRM. Collaborative working in health and social care: Lessons learned from post-hoc preliminary findings of a young families’ pregnancy to age 2 project in South Wales, United Kingdom. Health Soc Care Commun. 2021 29(4):1115–25. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hsc.13146. Cited 22 Feb 2023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Kildea S, Stapleton H, Murphy R, Low NB, Gibbons K. The Murri clinic: a comparative retrospective study of an antenatal clinic developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. 2012. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/12/159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, Kruske S, Nelson C, Blackman R, et al. Reducing preterm birth amongst aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies: a prospective cohort study, Brisbane Australia. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;12:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, Nelson C, Kruske S, Carson A, et al. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for first nations Australians: a prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(5):e651–e659. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klerman L v, Ramey SL, Goldenberg RL, Marbury S, Hou J, Cliver SP, et al. Versity of Alabama at Birmingham. Requests for reprints should be sent to Lorraine a randomized trial of augmented prenatal care for multiple-risk, medicaid-eligible African American Women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lack BM, Smith RM, Arundell MJ, Homer CSE. Narrowing the Gap? Describing women’s outcomes in midwifery group practice in remote Australia. Women Birth. 2016;29(5):465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu R, Chao MT, Jostad-Laswell A, Duncan LG. Does centering pregnancy group prenatal care affect the birth experience of underserved women? A mixed methods analysis. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017 19(2);415–22. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10903-016-0371-9. Cited 22 Feb 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Madeira AD, Rangen CM, Avery MD. Design and implementation of a group prenatal care model for Somali women at a low-resource health clinic. Nurs Womens Health. 2019;23(3):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malebranche M, Norrie E, Hao S, Brown G, Talavlikar R, Hull A, et al. Antenatal care utilization and obstetric and newborn outcomes among pregnant refugees attending a specialized refugee clinic. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(3):467–475. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00961-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McAree T, McCourt C, Beake S. Perceptions of group practice midwifery from women living in an ethnically diverse setting. Evid Based Midwifery. 2010;8(3):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Middleton P, Bubner T, Glover K, Rumbold A, Weetra D, Scheil W, et al. ‘Partnerships are crucial’_ an evaluation of the aboriginal family birthing program in South Australia. Austr N Zeal J Public Health. 2017;41(1):21–26. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morris M, Seibold C, Webber R. Drugs and having babies: An exploration of how a specialist clinic meets the needs of chemically dependent pregnant women. Midwifery. 2012;28(2):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nel P, Pashen D. Shared antenatal care for indigenous patients in a rural and remote community. Austr Fam Phys. 2003;32(3):127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owens C, Dandy J, Hancock P. Perceptions of pregnancy experiences when using a community-based antenatal service: a qualitative study of refugee and migrant women in Perth Western Australia. Women Birth. 2016;29(2):128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piechnik SL, Corbett MA. Reducing low birth weight among socioeconomically high-risk adolescent pregnancies: successful intervention with certified nurse-midwife-managed care and a multidisciplinary team. J Nurse Midwifery. 1985;30:88. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(85)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quelly SB, LaManna JB, Stahl M. Improving care access for low-income pregnant women with gestational diabetes. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17(8):1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinlivan JA, Box H, Evans SF. Postnatal home visits in teenage mothers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9361):893–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reeve C, Banfield S, Thomas A, Reeve D, Davis S. Community outreach midwifery-led model improves antenatal access in a disadvantaged population. Aust J Rural Health. 2016;24(3):200–206. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reguero W, Crane M. Project mother care: one hospital’s response to the high perinatal death rate in New Haven CT. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(5):647–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robertson B, Aycock DM, Darnell LA. Comparison of centering pregnancy to traditional care in hispanic mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2009 13(3):407–14. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-008-0353-1. Cited 22 Feb 2023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Ross MG. Health impact of a nurse midwife program. Nurs Res. 1981;30(6):363. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rutman D, Hubberstey C, Poole N, Schmidt RA, van Bibber M. Multi-service prevention programs for pregnant and parenting women with substance use and multiple vulnerabilities: program structure and clients’ perspectives on wraparound programming. BMC Pregn Childb. 2020;20(1):441. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smoke J, Grace MC. Effectiveness of prenatal care and education for pregnant adolescents: Nurse-midwifery intervention and team approach. J Nurse-Midwifery. 1988;33(4):178–184. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(88)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stapleton H, Murphy R, Correa-Velez I, Steel M, Kildea S. Women from refugee backgrounds and their experiences of attending a specialist antenatal clinic. Narratives from an Australian setting. Women Birth. 2013;26(4):260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Colon L, Vega P, Alonso A. Improved adequacy of prenatal care and healthcare utilization among low-income latinas receiving group prenatal care. J Womens Health. 2013;22(12):1056–1061. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner BJ, Newschaffer CJ, Cocroft J, Fanning TR, Marcus S, Hauck W. Improved birth outcomes among HIV-infected women with enhanced medicaid prenatal care. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):85–91. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiggins M, Oakley A, Roberts I, Turner H, Rajan L, Austerberry H, et al. Postnatal support for mothers living in disadvantaged inner city areas: a randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Commun Health (1978) 2005;59(4):288–95. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.021808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong R, Herceg A, Patterson C, Freebairn L, Baker A, Sharp P, et al. Positive impact of a long-running urban aboriginal medical service midwifery program. Austr N Z J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2011;51(6):518–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews a product from the ESRC methods programme Peninsula medical school, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth. 2006;

- 71.Filby A, Robertson W, Afonso E. A service evaluation of a specialist migrant maternity service from the user’s perspective. Br J Midwifery. 2019;28(9):652. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2020.28.9.652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lenaway D, Koepsell TD, Vaughan T, van Belle G, Shy K, Cruz-Uribe F. Evaluation of a public-private certified nurse-midwife maternity program for indigent women. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(4):675–679. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.4.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trudnak TE, Arboleda E, Kirby RS, Perrin K. Outcomes of Latina women in centering pregnancy group prenatal care compared with individual prenatal care. J Midwifery Womens Health 2013;58(4):396–403. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jmwh.12000. Cited 22 Feb 2023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Panaretto KS, Lee HM, Mitchell MR, Larkins SL, Manessis V, Buettner PG, et al. Impact of a collaborative shared antenatal care program for urban indigenous women: a prospective cohort study. Med J Austr. 2005;182(10):514–519. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mersky JP, Janczewski CE, Plummer Lee CT, Gilbert RM, McAtee C, Yasin T. Home Visiting Effects on Breastfeeding and Bedsharing in a Low-Income Sample. 10.1177/1090198120964197. 2020 48(4);488–95. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1090198120964197?journalCode=hebc. Cited 22 Feb 2023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Zephyrin L, Seervai S, Lewis C, Katon JG. Community-based models improve maternal outcomes and equity. Commonwealth Fund. 2021; Available from: 10.26099/6s6k-5330. Cited 22 Aug 2022

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 3. Inclusion-Exclusion criterion.

Data Availability Statement

All related files have been attached to the submission as appendices or supplementary files.