Summary

Background

Melatonin has become a widely used sleeping aid for young individuals currently not included in existing guidelines. The aim was to develop a recommendation on the use of melatonin in children and adolescents aged 2–20 years, with chronic insomnia due to disorders beyond indication.

Methods

We performed a systematic search for guidelines, systematic reviews, and randomised trials (RCTs) in Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, Cinahl, Guidelines International Network, Trip Database, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, European Sleep Research Society and Scandinavian Health Authorities databases. A separate search for adverse events was also performed. The latest search for guidelines, systematic reviews, and adverse events was performed on March 17, 2023. The latest search for RCTs was performed on to February 6, 2023. The language was restricted to English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish. Eligible participants were children and adolescents (2–20 years of age) with chronic insomnia due to underlying disorders, in whom sleep hygiene practices have been inadequate and melatonin was tested. Studies exclusively on autism spectrum disorders or attention deficit hyperactive disorder were excluded. There were no restrictions on dosage, duration of treatment, time of consumption or release formula. Primary outcomes were quality of sleep, daytime functioning and serious adverse events, assessed at 2–4 weeks post-treatment. Secondary outcomes included total sleep time, sleep latency, awakenings, drowsiness, quality of life, non-serious adverse events, and all-cause dropouts (assessed at 2–4 weeks post-treatment), plus quality of sleep and daytime functioning (assessed at 3–6 months post-treatment). Pooled estimates were calculated using inverse variance random effects model. Statistical heterogeneity was calculated using I2 statistics. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. A multidisciplinary guideline panel constructed the recommendation using Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). The certainty of evidence was considered either high, moderate, low or very low depending on the extent of risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, or publication bias. The evidence-to-decision framework was used to discuss the feasibility and acceptance of the constructed recommendation and its impact on resources and equity. The protocol is registered with the Danish Health Authority.

Findings

We identified 13 RCTs, including 403 patients with a wide range of conditions. Melatonin reduced sleep latency by 14.88 min (95% CI 23.42–6.34, 9 studies, I2 = 60%) and increased total sleep time by 18.97 min (95% CI 0.37–37.57, 10 studies, I2 = 57%). The funnel plot for total sleep time showed no apparent indication of publication bias. No other clinical benefits were found. The number of patients experiencing adverse events was not statistically increased however, safety data was scarce. Certainty of evidence was low.

Interpretation

Low certainty evidence supports a moderate effect of melatonin in treating sleep continuity parameters in children and adolescents with chronic insomnia due to primarily medical disorders beyond indication. The off-label use of melatonin for these patients should never be the first choice of treatment, but may be considered by medical specialists with knowledge of the underlying disorder and if non-pharmacological interventions are inadequate. If treatment with melatonin is initiated, adequate follow-up to evaluate treatment effect and adverse events is essential.

Funding

The Danish Health Authority. The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, supported by the Oak Foundation.

Keywords: Children and adolescents, Chronic insomnia, Melatonin, Underlying disorders

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Melatonin has gained popularity as a sleep aid within the past decade, yet there are currently no recommendations available to guide clinicians on use of melatonin in children and adolescents with disorders beyond autism spectrum disorders and attention deficits hyperactive disorder (ADHD). We aimed to develop the first clinical, evidence-based recommendation for use of melatonin in disorders that are beyond indication, and thus currently not included in existing guidelines.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence-based clinical recommendation on this topic in children and adolescents with disorders other than autism spectrum disorders and ADHD. We searched multiple databases, with the latest search performed in March 2023. We found 13 studies reporting on the use of melatonin in children and adolescents (aged 1–26 years) with various disorders beyond indication. Evidence of low certainty collectively supports a moderate reduction of sleep latency by 15 min and a moderate increase in total sleep time by 19 min. These improvements in sleep continuity parameters did not have an impact on daily functioning or the quality of sleep. Evidence on adverse events was scarce. Our recommendations, outlined below, were constructed by a multidisciplinary guideline panel based on the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Implications of all the available evidence

Based on our findings, we recommend careful use of melatonin to treat insomnia attributable to disorders ranging beyond indications in children and adolescents. Such off-label treatment with melatonin should only be considered by a medical specialist with knowledge of the underlying disorder and in those cases where non-pharmacological interventions have proven to be inadequate. It remains to be investigated whether melatonin may provide a differential magnitude of effect and adverse event profile across different disorders.

Introduction

The use of synthetic melatonin prescribed as a sleep aid for children and adolescents has increased substantially within the last decade.1,2 In Denmark, the use of melatonin is approved as a sleep aid for a narrow set of paediatric patients including autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).3 For all other conditions, the use of melatonin is considered off-label, meaning that the decision to initiate treatment and the consequences this may have, is the responsibility of the prescribing clinician. Registry data from the Danish Health Data Authority from 2011 to 2021 show that the number of individuals using prescribed melatonin more than tripled for those aged 0–17 years, whereas a sevenfold increase was seen for those between 18 and 24 years of age.4 The increase in users of prescribed melatonin was seen in individuals presenting both with and without a diagnosis that based on indication could justify its use.4 In Denmark, there are currently no evidence-based recommendations that may guide clinical decision-making on the use of melatonin to treat insomnia attributed to underlying disorders beyond autism spectrum disorders and ADHD.5,6

Due to the substantial increase in users of prescribed melatonin, the Danish Health Authority initiated the work with constructing a recommendation, which based on a critical assessment of the current evidence evaluated the use of melatonin for patient groups, who are currently not included in existing guidelines. Here, we report these findings, including the certainty of evidence, pooled estimates of effects and the final clinical recommendation constructed following the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

Methods

Organisation of the work and the methodology applied

This study follows the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) framework,7 GRADE methodology,8 guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration9 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA).10, 11, 12 It is part of a group of national clinical recommendations published by the Danish Health Authority (November 2022).13 A prespecified protocol was approved by the management from the Department of Evidence Based medicine at the Danish Health Authority (December 19, 2021) and is publicly available on the Danish Health Authority website at https://www.sst.dk/da/Udgivelser/2022/NKA_-Behandling-med-melatonin-ved-soevnforstyrrelser-hos-boern-og-unge. The PRISMA report and organisation of the work are presented in the Supplementary.

Eligibility criteria (PICO question)

The population included children and adolescents aged 2–20 years with chronic insomnia due to underlying disorders, and where sleep hygiene practices were inadequate. The diagnosis of chronic insomnia refers to the diagnosis of chronic insomnia disorder found in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, version 3 (ICSD-3), which includes repeated difficulties with maintaining—or initiating sleep, or issues with the duration or quality of sleep despite adequate circumstances to obtain sleep. These issues should be present for at least 3 months, at least 3 times a week and result in issues with daytime functioning. In accordance with ICSD-3, insomnia symptoms may be seen both in the presence or absence of an underlying medical–or mental condition.14 From a clinical point of view, treating insomnia in patients with underlying conditions can be especially challenging due to a complex symptom profile and use of concomitant medications and thus treatment is often warranted in specialised medical facilities. To provide a clinical recommendation for these patients, we here chose to include studies investigating the use of melatonin in children and adolescents who displayed chronic insomnia as a secondary symptom to an underlying condition in accordance with the definition provided by ICSD-3. Patients presenting with idiopathic insomnia or with a sleep disorder, such as sleep-related breathing disorders and sleep-related movement disorders, were not considered for inclusion. Participants with insomnia attributed entirely to autism spectrum disorders or ADHD were also excluded, as melatonin is an approved treatment for these conditions and thus recommendations on the use of melatonin in these patients already exist. Studies on neurodevelopmental disorders were included if the number of participants with autism or ADHD was <30%. This cut-off was based on expert opinions by the guideline panel, and chosen as it was considered a sufficiently low level by which the population could not be considered to primarily represent either ADHD or autism. The intervention was melatonin, with no restrictions on dosage, treatment length, release formula or time of administration. The comparison was no treatment or treatment with any non-pharmacological intervention. Primary outcomes were quality of sleep, daytime functioning and serious adverse events, assessed at 2–4 weeks following treatment. Secondary outcomes included total sleep time, sleep latency, awakenings, drowsiness/sleepiness, quality of life, non-serious adverse events and all-cause dropouts, all assessed at 2–4 weeks following treatment as well as quality of sleep and daytime functioning, assessed after 3–6 months of treatment. Assessment of long-term consequences will be published separately.15 We did not a priori make any requirements on how outcomes were to be assessed.

Literature search and selection of studies

We performed a systematic search in Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, Cinahl, Guidelines International Network, Trip Database, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, European Sleep Research Society and the Scandinavian Health Authorities databases. Keywords included medical subject headings and free-text search words, with no restrictions on publication status. The search was performed in four steps to identify: 1) clinical guidelines and health technology assessments, published within the last 12 years, 2) systematic reviews and meta-analysis, published within the last 7 years, 3) randomised controlled trials (RCT), with no date restriction and 4) a restricted search for adverse events in RCTs, with no date restriction. Guidelines, systematic reviews and restricted search for adverse events were searched up to March 17, 2023. RCTs were searched up to February 6, 2023.

Language was restricted to English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish. The search strategies are found in the Supplementary. Included studies were assessed for additional relevant studies. Members of the guideline panel (content experts) were used as a source to verify that all known trials were identified.

All identified studies were imported to RefWorks and duplicates were removed. The Covidence software was used for final screening and selection.16 The title and abstracts were assessed by one reviewer (HEC). Full texts were evaluated in duplicate by two independent reviewers (HEC and HKA) based on the PICO criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The reviewers were not blinded to journal titles, year of publication or authors/institutions.

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias

Data extraction was performed in the Covidence software16 and included; study design, funding, diagnosis, age, length of treatment, dosage, release formula, information on the control condition, any use of concomitant medications, and outcomes of interest. Actigraphy was prioritised if a study reported different types of measurements on sleep continuity parameters. If only case clock times were provided, these were transformed into minutes. In the case of cross-over designs, extraction of data from the first period was prioritised to prevent potential carry-over effects.9 Evaluation of risk of bias was performed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, version 1.17 Studies with two or more unclear domains, and/or one or more high risk domains were considered studies with overall high risk of bias. Funnel plots were constructed if outcomes were reported by a sufficient number of studies (min. 10 studies).18 Further, we planned to perform Eggers test if publication bias was detected through visual inspection of funnel plots. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were performed in duplicate and independently by two reviewers (HEC and HKA). Discrepancy was resolved through discussion. The authors of the included studies were not contacted in case of missing data.

Summary measures and statistical analysis

A table was constructed, displaying the outcomes reported in each of the included studies (outcome matrix available upon request). Meta-analysis was performed in RevMan 5, version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration), using inverse variance random-effects models.19 Dichotomous outcomes were calculated as relative risk (RR). Continuous outcomes were calculated as mean difference (MD), or standardised mean difference (SMD) if different rating scales were used for a given outcome. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was included for all estimates. Statistical heterogeneity was calculated using I2 statistics.20 In case any statistically significant results were identified, an assessment of baseline values was performed to evaluate the extent of the clinical relevance in effect. Baseline values were extracted from the included studies when available and the range of values was presented. If possible, post hoc subgroup analysis was performed to assess the effect of dosage (below and above 5 mg), age (below and above 12 years of age) and type of release formula (immediate release and prolonged release formulation). If possible, sensitivity analysis was to be performed to assess the impact of risk of bias on estimates. Both post hoc tests and sensitivity analysis were performed in RevMan 5, version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration).

Certainty of evidence and recommendation

The certainty of evidence depended on the extent of risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness or publication bias. The overall certainty of evidence reflected the lowest level of certainty for the primary outcomes.8 The final recommendation was based on a weighted evaluation of benefits and harms, patient preferences and overall certainty of evidence–eventually leading to a strong or conditional recommendation, in favour or against the intervention. The evidence to decision framework (EtD) was used to discuss acceptance and feasibility of the recommendation, alongside the impact on resources and equity.21 Patient preferences and the evaluation of factors relevant to healthcare providers (acceptability, resources, equity and feasibility) were based on expert opinion of the multidisciplinary guideline panel. These expert opinions were subsequently tested in a public hearing, in which relevant patient organisations and healthcare decision-makers were invited to review the final recommendation.

Role of funding source

The work was funded by the Danish Health Authority. The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital supported by the Oak Foundation. The Danish Health Authority was involved in all steps of this study, including the study design, data extraction and–analysis, results interpretation and development of the final recommendation.

Results

Search for literature

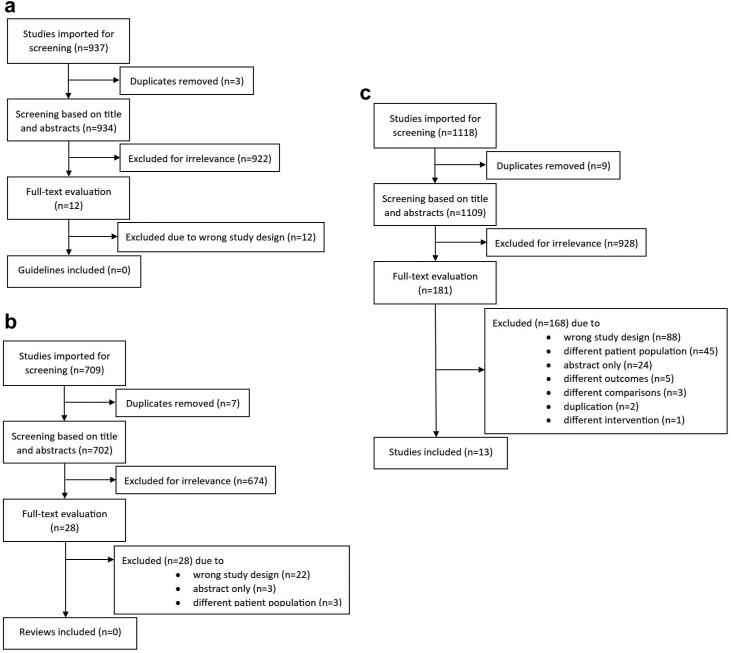

We found no relevant existing guidelines (Fig. 1a). The search for systematic reviews resulted in 28 reviews, all of which were excluded following a thorough assessment (Fig. 1b). In the search for RCTs, we identified 1109 references, of which 181 full texts were selected, leading to a total of 12 included studies, reported in 13 publications22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34; (Fig. 1c). The separate search for adverse events did not contribute to any further RCTs. The PRISMA flowcharts and list of excluded primary studies at full-text level are found in the Supplementary.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowcharts for the screening of (a) guidelines, (b) systematic reviews and (c) randomised controlled studies. Initial and updated search combined.

Description of the included randomised controlled trials

The 13 studies included 403 patients, aged 1–26 years of age, presenting with a range of disorders. These included atopic dermatitis,22,23 epilepsy,24, 25, 26 mental retardation with/without epilepsy,29 neurodevelopmental disorder with predominantly other disorders than ADHD and autism,27,28 post-concussion,30 Angelman syndrome,31 Dravets syndrome,32 Rett syndrome33 and cystic fibrosis.34 All studies compared the effect of melatonin to placebo. One study was divided into two separate publications, where melatonin was evaluated as an add-on to valproate.24,25 Six of the studies included parallel groups,22,24,25,30,31,34 and seven were crossover trials.23,26, 27, 28, 29,32,33 None of the crossover trials reported on effects during the first period, and thus data is based on the overall estimate of effects. Four studies explicitly mentioned sleep hygiene practices being tested before starting the trial.27, 28, 29,31 Ten of the studies used immediate-release melatonin22, 23, 24, 25,28,29,31, 32, 33, 34 while two studies applied prolonged-release melatonin.26,30 One study used both formulations.27 Dosage ranged from 3 mg to 15 mg. Time of ingestion took place between 20 min and 2 h before bedtime. The duration of treatment ranged from 10 days to 6 weeks. Five studies explicitly mentioned concomitant medications, which mainly consisted of antiepileptic drugs.24,25,31, 32, 33 In three studies, the use of concomitant medications potentially affecting sleep was reason for exclusion.23,26,34 The use of concomitant medicine was not explicitly stated in four studies.27, 28, 29, 30 All studies measured the effect at the end of treatment. The characteristics of the included studies are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 13 included randomised controlled trials.

| Author, year, country, trial registration | Demographics, Sex (male/female) Age (range or mean (SD)) | Design and funding | Intervention (s) | Comparison | Duration | Outcomes of interest, measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braam, 2008, the Netherlands31 No protocol identified |

n = 8, participants with Angelman syndrome and idiopathic chronic insomnia Sex: 3/5 Age, years: 4–21 Melatonin group (n = 4) Control (placebo) group (n = 4) |

Randomized, double blind, placebo -controlled trial. Funding: Heeren Loo Zorggroep Steunfonds |

Melatonin, 5 mg fast release capsules (5-methoxy-N-acetyltryptamine)—Duchefa Farma BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Participants under age 6 years received 2.5 mg tablets Concomitant medicine: Antiepileptic drug use: carbamazepine, clobazam, valproate, ethosuximide Sleep medication: midazolam, pipamperon |

Placebo capsules | 4 weeks |

Total sleep time: Sleep log Sleep onset: method not stated Sleep latency: method not stated Wake-up time: method not stated Mean number and length of wakes: number of Adverse events |

| Barlow, 2021, Canada30 Trial registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT01874847 |

n = 71, participants with persistent post-concussion symptoms Sex: 29/42 Age, years: 8–18 Melatonin group 3 mg (n = 25) Sex: 12/13 Age, years: 13.7 years Melatonin group 10 mg (n = 25) Sex: 9/16 Age, years: 14.2 years Control (placebo) group (n = 22) Sex: 12/13, Age, years: 14.2 years |

RCT, single center, parallel group, three arms. Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number 293375, Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, and the University of Calgary (10,006,634). Dr. Barlow acknowledges funding from the Motor Accident Insurance Commission, Queensland, Australia (61278). |

Melatonin 3 mg and 10 mg. Sustained-release sublingual melatonin preparations Concomitant medicine None mentioned |

Placebo | 4 weeks | Total sleep time: objective measurement (actigraph) Total sleep time: Actigraph Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Wake after sleep onset (WASO): Actigraph Dropouts: Number of participants |

| Chang, 2016, Taiwan23 Trial registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT01638234 |

n = 48, participants with Atopic Dermatitis and Sleep Disturbance Sex: 25/23 Age, years: 7.5 (3.7) Melatonin group (n = 24) Sex: 11/13 Age, years: 7.6 (4.0) Control (placebo) group (n = 24) Sex: 14/10 Age, years: 7.3 (3.5) |

RCT cross over study, single center parallel group, two arms. Funding: Supported by joint grants 99-TYN01 and 100-TYN01 from the National Taiwan University Hospital and the Yonghe Cardinal Tien Hospital. |

Melatonin, 3 mg fast release capsules (General Nutrition Corporation) at bedtime. Crossover study–2 weeks wash out Concomitant medicine Use of medication for insomnia or antidepressants within 4 weeks before baseline was reason for exclusion. |

Placebo (Standard Chem & Pharm Co, Ltd) capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 4 weeks pr cycle |

Quality of sleep: subjective and objective (Actigraph) measurements Total sleep time: Sleep log Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Dropouts: Number of participants |

| Coppola, 2004, Italy29 No protocol identified |

n = 25, participants with mental retardation with or without epilepsy. Mental delay was mild in 3 (12%) patients, moderate in 8 (32%), and severe in 14 (56%). Sex: 16/9 Age, years: 10.5 (3.6–26 years) |

RCT cross over study, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: None stated |

Melatonin 3 mg fast release capsules, at nocturnal bedtime. Dose could be titrated up to 9 mg the following 2 weeks at increments of 3 mg/week, unless the patient was unable to tolerate it. Cross over study—1 week washout Concomitant medicine Pre-existing medicine was unaltered throughout the trial. Type of medicine not explicitly mentioned. |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 4 weeks pr cycle |

Total sleep time: Sleep log Sleep onset latency: Sleep log Mean number and length of wakes: |

| De Castro-Silva, 2010, Brazil34 No protocol identified |

n = 19, participants with cystic fibrosis Melatonin group (n = 9). Sex: 6/3 Age, years: 16.6 (8.26) Placebo group (n = 10). Sex: 5/5 Age, years: 12.1 (6.0) |

RCT, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: None stated |

Melatonin 3 mg fast release capsules Concomitant medicine Use of hypnotic-sedative drugs was reason for exclusion |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 3 weeks |

Quality of sleep: subjective (Pittsburg sleep quality index) and objective (PSQI) measurements. Total sleep time: Actigraph Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Wake after sleep onset (WASO): Actigraph |

| Dodge, 2001, US28 No protocol identified |

n = 20, participants with Developmental Disabilities No sex data available Age, months: mean 89 (13 months–180 months) Melatonin group (n = 20) Placebo group (n = 20) |

RCT cross over study, single center parallel group, two arms. Funding: United Cerebral Palsy Association of Greater Indiana |

Melatonin 5 mg fast release capsules Cross over study—1 week washout Concomitant medicine Nothing mentioned |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 6 weeks |

Sleep onset latency: Sleep log Wake-up time: Actigraph Total sleep time: Sleep log Mean number awakenings/night: sleep log |

| Gupta, 2004, India25 No protocol identified |

n = 30, participants with Epilepsy Sex:18/12 Age, years: 3–12 years Melatonin group (n = 16) Sex: 8/8 Age, years: 7.4 (3.2) Control (placebo) group (n = 14) Sex: 10/4 Age, years: 6.6 (3.9) |

RCT, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: None stated |

Melatonin 6 mg fast release capsules for children <30 kg Melatonin 9 mg fast release capsules for children >30 kg Children were included if they had been receiving sodium valproate (10 mg/kg/d) for the last 6 months Concomitant medicine Nothing mentioned |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules Children were included if they had been receiving sodium valproate (10 mg/kg/day) for the last 6 months |

4 weeks |

Daytime functioning: QOLCE (attention/concentration) Daytime drowsiness score Quality of life in children with epilepsy (QOLCE) Dropouts: Number of participants |

| Gupta, 2005, India24 No protocol identified |

n = 30, participants with Epilepsy Sex:18/12 Age, years: 3–12 years Melatonin group (n = 16) Sex: 8/8 Age, years: 7.4 (3.2) Control (placebo) group (n = 14) Sex: 10/4 Age, years: 6.6 (3.9) The patient population, intervention and comparison are identical to the study of Gupta 2004. |

RCT, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: None stated |

Melatonin 6 mg fast release capsules for children <30 kg Melatonin 9 mg fast release capsules for children >30 kg Children were included if they had been receiving sodium valproate (10 mg/kg/day) for the last 6 months Concomitant medicine Nothing mentioned |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules Children were included if they had been receiving sodium valproate (10 mg/kg/day) for the last 6 months |

4 weeks |

Total sleep time: Lickert scale Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Wake after sleep onset (WASO): Actigraph |

| Jain 2015, US26 Trial registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT00965575 |

n = 11, participants with Epilepsy Sex 7/3 Age, years: 6–11 years Melatonin group (n = 10–analyzed) Placebo group (n = 10–analyzed) |

RCT cross over study, single center parallel group, two arms Funding: Clinical Research Feasibility Funds (CReFF) by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science, and Training, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center |

Melatonin 9 mg sustained release capsules Cross over study—1 week washout Concomitant medicine: Concurrent use of hypnotics, stimulants, systemtic corticosteroids or other immune-suppressants were excluded |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 4 weeks pr cycle |

Quality of sleep: subjective measurements (Sleep Behavior Questionnaire) Total sleep time: Lickert scale Sleep onset latency: Sleep log Wake after sleep onset (WASO): Actigraph |

| McArthur 1998, US33 No protocol identified |

n = 9, female participants with Rett syndrome Sex: 0/9 Age, years: mean 10.1 (1.5) Melatonin group (n = 9) Sex: 0/9, Age, years: mean 10.1 (1.5) Control (placebo) group (n = 9) Sex: 0/9, Age, years: mean 10.1 (1.5) |

RCT cross over study, single center parallel group, two arms. Funding: A research grant from the International Rett Syndrome Association |

Melatonin 2.5 to 7.5 mg fast release capsules, based upon individual body weight (Regis Chemical Company (Morton Grove, Il, USA) Cross over study—1 week washout Concomitant medicine Seizure medication including: Phenobarbital, carbamazepine, ethosuximide, valproate, gabapentin, felbamate. |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 4 weeks pr cycle |

Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Total sleep time Sleep efficiency Number of awakenings |

| Myers 2018, Australia32 Trial registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT00965575 |

n = 13, participants with Dravet Syndrome and sleep disturbance Sex: 4/9 Age, years: mean 12.2 (4.9–38) Melatonin group (n = 13–analyzed) Sex: 4/9 Age, years: mean 12.2 (4.9–38) Placebo group (n = 13–analyzed) Sex: 4/9 Age, years: mean 12.2 (4.9–38) |

RCT cross over study, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grants (628952, 1091593) |

Melatonin 6 mg fast release capsules Cross over study—1 week washout Concomitant medicine Topiramate, valproic acid, clobazam, stiripentol, levetiracetam, clonidine, atomoxetine, phenytoin, zonisamide, acetazolamide, lamotrigine, ethosuximide |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 2 weeks pr cycle |

Quality of sleep: subjective measurements (Sleep disturbances Scale in children) Total sleep time: Actigraph Wake after sleep onset (WASO): Actigraph Quality of life in children with epilepsy (QOLCE-55) |

| Taghavi Ardakani 2018, Iran22 Trial registration: http://www.irct.ir: IRCT2017082733941N12 |

n = 70, participants with Atopic Dermatitis and Sleep Disturbance Sex: 34/36 Age, years: 6–12 yr Melatonin group (n = 35) Sex: 16/19 Age, years: 8.9 (2.1) Control (placebo) group (n = 35) Sex: 18/17 Age, years: 8.4 (2.2) |

RCT, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: 96110 |

Melatonin 6 mg fast release capsules (2 × 3 mg) 1 h before bedtime Concomitant medicine Topical corticosteroid (mometasone) |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 6 weeks |

Quality of sleep: subjective measurements (Childrens sleep habits questionnaire) Total sleep time: Sleep log Sleep onset latency: Sleep log Daytime drowsiness score Dropouts: Number of participants |

| Wasdell 2008, Canada27 No protocol identified |

n = 50, participants with Neurodevelopmental disabilities Sex: 31/19 Age, years: mean 7.38 yr (range 2.05–17.81 yr) Melatonin group (n = 50) Sex and age (years): as above Control (placebo) group (n = 50) Sex and age (years): as above |

RCT cross over study, single center, parallel group, two arms. Funding: This study was sponsored as an investigator-initiated trial by Circa Dia BV |

Melatonin 5 mg (1 mg fast release; 4 mg sustained release) capsules (provided by Circa Dia BV, The Netherlands). Administered 20–30 min before bedtime Duration: 10 days Cross over study—3–5 days washout Concomitant medicine Nothing mentioned |

Placebo capsules, which looked identical to the melatonin capsules | 1.5 weeks pr cycle |

Quality of sleep: Objective measurements–Actigraph Daytime functioning: CGI (Parents global assessment scale) Total sleep time: Actigraph Sleep onset latency: Actigraph Number of waking episodes Dropouts: Number of participants |

Mg: milligram, WASO: wake after sleep onset, PSQI: Pittsburg sleep quality index, kg: kilogram, QOLCE: Quality of life in children with epilepsy.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Two studies had high risk of bias in the domain concerning random sequence generation,28,32 while it was unclear for four studies.29,31,33,34 Six studies were unclear in one or more of the domains concerning blinding, incomplete and selective outcome reporting.23, 24, 25,28,29,33 Three studies had high risk of bias concerning blinding.26,31,32 An overview of the risk of bias is found in the Supplementary.

Estimated effects

Primary outcomes

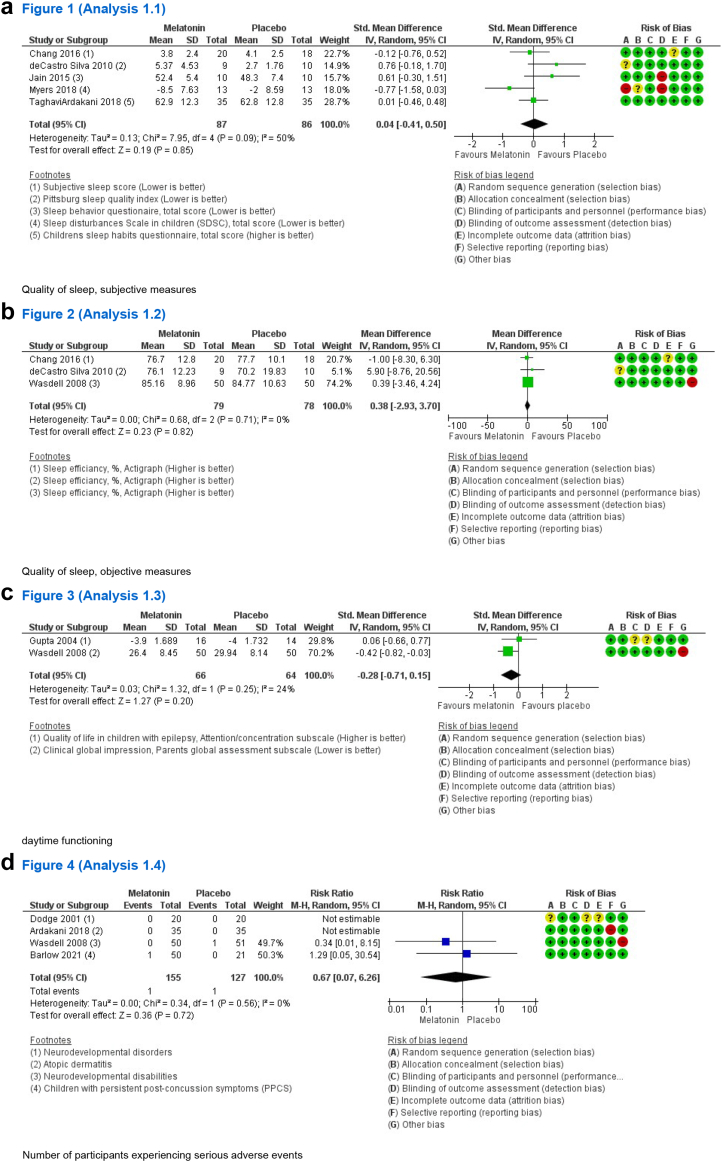

Melatonin had no impact on quality of sleep when assessed on a subjective scale (SMD 0.04, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.50, I2 = 50%, 5 studies, low certainty) (see Table 2 and Fig. 2a) nor when measured as sleep efficiency using actigraphy (%) (MD 0.38, 95% CI −2.93 to 3.70, I2 = 0%, 3 studies, moderate certainty) (see Fig. 2b). No effect was found on daytime functioning (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.71 to 0.15, I2 = 24%, 2 studies, low certainty) (see Fig. 2c) and use of melatonin did not increase the number of participants experiencing serious adverse events (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.07–6.26, I2 = 0%, 4 studies, moderate certainty) (see Table 2 and Fig. 2d). Subgroup analyses were not performed due to the few included studies. Sensitivity analysis showed no subgroup difference when studies of high–and low risk of bias were compared across outcomes. Sensitivity analysis is presented in the Supplementary.

Table 2.

Estimated effects and certainty of evidence for each outcome in accordance with GRADE.

| Outcome | Results | Effect estimates |

Certainty of evidence | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No melatonin | Melatonin | ||||

| Dropouts—all cause | Relative risk: 0.58 (CI 95% 0.27–1.23) Based on data from 322 patients in 5 studiesa |

102 per 1.000 | 59 per 1.000 |

Moderate Due to serious imprecisionb |

Melatonin probably has no or little effect on all-cause dropout |

| Difference: 43 fewer per 1.000 (CI 95% 74 fewer–23 more) | |||||

| Quality of sleep (subjective measure) | Measured by: Pittsburg sleep quality index (self-reported); Sleep behavior questionnaire (total score, self-reported); Sleep disturbances scale in children (total score, caregiver reported); Children sleep habits questionnaire (total score, self-reported) Scale: Lower is better Based on data from 173 patients in 5 studiesc |

Difference: SMD 0.04 higher (CI 95% 0.40 lower–0.50 higher) |

Low Due to very serious imprecisiond |

Melatonin may have no or little effect on the quality of sleep | |

| Daytime functioning | Measured by: Clinical global impression scale (parents global assessment subscale); Quality of life in children with epilepsy (attention/concentration subscale) Scale: Lower is better Based on data from 130 patients in 2 studiese |

Difference: SMD 0.28 lower (CI 95% 0.71 lower–0.15 higher) |

Low Due to very serious imprecisionf |

Melatonin may have no or little effect on daytime functioning | |

| Total sleep time | Measured by: Total time spent sleeping in minutes pr night. Assessed by either actigraph or sleep diary Scale: Higher is better Based on data from 401 patients in 10 studiesg |

Difference: MD 18.97 higher (CI 95% 0.37 higher–37.57 higher) |

Moderate Due to serious inconsistencyh |

Melatonin leads to a moderate increase in the total duration of sleep | |

| Sleep latency | Measured by: Time taken to fall asleep in minutes. Assessed by either actigraph or sleep diary Scale: Lower is better Based on data from 357 patients in 9 studiesi |

Difference: MD 14.88 lower (CI 95% 23.42 lower–6.34 lower) |

Moderate Due to serious inconsistencyj |

Melatonin leads to a moderate decrease in sleep latency | |

| Awakenings | Measured by: Wake after sleep onset (WASO) in minutes Assessed by either actigraph or sleep diary Scale: Lower is better Based on data from 103 patients in 4 studiesk |

Difference: MD 13.12 lower (CI 95% 38.05 lower–11.81 higher) |

Low Due to serious inconsistency, Due to serious imprecisionl |

Melatonin may have no or little effect on awakenings | |

| Drowsniess/sleepiness | Measured by: Daytime drowsiness score; Daytime sleepiness score Scale: Lower is better Based on data from 100 patients in 2 studiesm |

Difference: SMD 0.04 lower (CI 95% 0.43 lower–0.35 higher) |

Low Due to very serious imprecisionn |

Melatonin may have no or little effect on drowsiness/sleepiness | |

| Quality of life | Measured by: Quality of life in children with epilepsy (total score); Quality of life in children with epilepsy-55 (total score) Scale: Higher is better Based on data from 56 patients in 2 studieso |

Difference: MD 1.32 higher (CI 95% 0.41 higher–2.24 higher) |

Very low Due to very serious imprecision, Due to serious indirectnessp |

The effect on quality of life is uncertain. | |

| Number of patients experiencing serious adverse events | Relative risk: 0.67 (CI 95% 0.07–6.26) Based on data from 282 patients in 4 studiesq |

8 per 1.000 | 7 per 1.000 |

Moderate Due to serious imprecisionr |

Melatonin probably has no or little effect on the number of patients experiencing serious adverse events |

| Difference: 1 fewer per 1.000 (CI 95% 7 fewer–41 more) | |||||

| Number of patients experiencing non-serious adverse events | Relative risk: 1.68 (CI 95% 0.87–3.26) Based on data from 187 patients in 5 studiess |

103 per 1.000 | 247 per 1.000 |

Moderate Due to serious imprecisiont |

Melatonin probably has no or little effect on the number of patients experiencing non-serious adverse events |

| Difference: 145 more per 1.000 (CI 95% 13 fewer–232 more) | |||||

MD: Mean difference, SMD: Standardised mean difference, WASO: Wake after sleep onset.

Gupta 2004, TaghaviArdakani 2018, Barlow 2021, Chang 2016, Wasdell 2008.

Serious imprecision: Wide confidence interval.

Myers 2018, Jain 2015, deCastro Silva 2010, Chang 2016, TaghaviArdakani 2018.

Very serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, Wide confidence interval.

Gupta 2004, Wasdell 2008.

Very serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, Wide confidence interval.

TaghaviArdakani 2018, Braam 2008, Coppola 2004, Wasdell 2008, Chang 2016, Gupta 2005, Jain 2015, Dodge 2001, deCastro Silva 2010, Myers 2018.

Serious inconsistency: I2 = 57%.

McArthur 1998, TaghaviArdakani 2018, Wasdell 2008, Coppola 2004, deCastro Silva 2010, Dodge 2001, Jain 2015, Braam 2008, Chang 2016.

Serious inconsistency: I2 = 60%.

Dodge 2001, Wasdell 2008, Coppola 2004, Braam 2008.

Serious inconsistency: I2 = 65%; Serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, Wide confidence interval.

Gupta 2005, TaghaviArdakani 2018.

Very serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, Wide confidence interval.

Myers 2018, Gupta 2004.

Serious indirectness. Selective patient group; Serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, Wide confidence interval.

Dodge 2001, Wasdell 2008, Barlow 2021, Ardakani 2018.

Serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, wide confidence interval.

McArthur 1998, Dodge 2001, Jain 2015, Chang 2016, Barlow 2021.

Serious imprecision: Data based on few patients, wide confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

Findings of the primary outcomes of (a) quality of sleep, subjective measures, (b) quality of sleep, objective measures, (c) daytime functioning, and (d) number of participants experiencing serious adverse events. SD: Standard deviation, CI: Confidence interval, SDSC: Sleep Disturbances Scale in children, PPCS: Persistent post-concussion symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

Melatonin increased the total sleep time by 18.97 min (95% CI 0.37–37.57, I2 = 57%, 10 studies, moderate certainty) (see Table 2), which was considered a moderate improvement compared to the total sleep time reported at baseline (ranged from 4 to 9.5 h). Further subgroup analysis showed no subgroup difference for age (p = 0.93), dosage (p = 0.40) or release formulations (p = 0.90). Sensitivity analysis showed no subgroup difference between studies of high–and low risk of bias. Forest plots and sensitivity analysis are presented in the Supplementary.

Sleep latency was reduced by 14.88 min (95% CI −23.42 to −6.34, I2 = 60%, 9 studies, moderate certainty) (see Table 2), which was considered a moderate effect compared to estimates at baseline (range from 25 to 90 min). Further subgroup analysis showed no statistical difference for age (p = 0.74), dosage (p = 0.45) or release formulations (p = 0.74). Sensitivity analysis showed a significant subgroup difference (p = 0.0005). Sleep latency was not affected in studies of low risk of bias (MD −3.50, 95% CI −8.29 to 1.30, I2 = 0%, 3 studies, low certainty), whereas studies of high risk of bias reported that sleep latency was reduced by 20.65 min (95% CI −29.07 to 12.23, I2 = 14%, 6 studies, moderate certainty). Forest plots and sensitivity analysis are found in the Supplementary.

Melatonin did not affect the average wake after sleep onset (WASO) (MD −13.12, 95% CI −38.05 to 11.81, I2 = 65%, 4 studies, low certainty) (see Table 2) or the average number of awakenings (MD −0.24, 95% CI −0.87 to 0.39, I2 = 48%, 4 studies, low certainty). No effect was found on drowsiness/sleepiness during the day (SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.35, I2 = 0%, 2 studies, low certainty), or on all-cause dropouts (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.27–1.23, I2 = 0%, 5 studies, moderate certainty) (see Table 2). The impact on quality of life was uncertain (MD 1.32, 95% CI 0.41–2.24, I2 = 26%, 2 studies, very low certainty) (see Table 2). Use of melatonin did not significantly increase the number of patients experiencing non-serious adverse events (RR 1.68, 95% CI 0.87–3.26, I2 = 0%, 5 studies, moderate certainty) (see Table 2). Sensitivity analysis showed no subgroup difference for these outcomes when studies of high and low risk of bias were compared. Forest plots and sensitivity analysis are found in the Supplementary.

None of the included studies reported on quality of sleep or daytime functioning at 3–6 months of treatment.

Reporting bias

The risk of reporting bias (e.g., selective outcome reporting) was low for both the primary—and secondary outcomes. The funnel plot for total sleep time showed no apparent indication of publication bias and thus no further Eggers test was performed (see Supplementary).

Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence concerning quality of sleep and daytime functioning was low (see Table 2). For serious adverse events, the certainty of evidence was moderate. Thus, the overall certainty of evidence was low.

Evidence-based recommendation

The guideline panel put emphasis on the evidence showing a moderate clinical improvement in total sleep time and sleep latency, yet without melatonin having an impact on the remaining outcomes concerning benefits. This was weighed against uncertain long-term consequences15 and that melatonin does not seem to increase adverse events, however further assessment across the different disorders is needed. The overall certainty of evidence was low (see Tables 2 and 3). The guideline panel suggests that both patients and parents show an increased motivation for testing melatonin as a sleep aid (see Table 3). However, the guideline panel agrees that sleep hygiene practices and non-pharmacological interventions are always to be considered first choice of treatment, which must be sufficiently tested and proven inadequate before treatment with melatonin is considered.

Table 3.

Evidence to decision framework (EtD).

|

The table displays to parameters taken into account in the development of the recommendation. These include the benefits and harms, certainty of evidence, patient values and preferences, resources, equity, acceptability and feasibility.

As such, a conditional recommendation was given in favour of melatonin as a treatment in children and adolescents aged 2–20 years, who despite optimisation of sleep hygiene practices continue to display deficits in daytime functioning due to chronic insomnia attributed to an underlying disorder.

The guideline panel assumes that the implementation of this recommendation may be challenged by access to non-pharmacological interventions, including counselling in sleep hygiene practices. The guideline panel believes that treatment with melatonin for these patients should be initiated and monitored by a medical specialist with knowledge of the underlying condition. Access to a medical specialist may also hinder the implementation. Also, the families need to be made aware that melatonin is only approved for a narrow set of paediatric patients, and thus for the majority of patients it is considered off-label. Resources may be influenced by the price of the prescribed melatonin product. Equity may be affected by price differences and by variations in access across the country to counselling in sleep hygiene practices and other non-pharmacological interventions (see Table 3).

Discussion

We recommend that melatonin may be used in children and adolescents aged 2–20 years with chronic insomnia due to underlying disorders ranging beyond indication, granted that daytime functioning is affected and that sleep hygiene practices have been inadequate. We consider this to be one of the first evidence-based recommendations on the matter.

Our results are based on 13 RCTs including a total of 403 participants presenting with various disorders ranging beyond indication. In these patients, melatonin led to a moderate clinical reduction in sleep latency by approximately 15 min and a moderate increase in total sleep time by about 19 min. The certainty of evidence was in both cases downgraded to moderate due to serious inconsistency, as reflected by high statistical heterogeneity across data. The included studies mainly focus on medical condition which varies in aetiology. This high variation in the underlying disorders being investigated evidently introduces imprecision in the findings presented here. In accordance, our pooled estimates are also affected by some level of statistical heterogeneity as well as wide confidence intervals. The directions of effects across studies are however consistent, and the observed imprecision may revolve around the magnitude of effects. The positive effect on total sleep time was mainly driven by two studies.29,31 The largest effect was reported by Braam et al. 2008,31 which was also the smallest of all the included studies (n = 4 in each group) and the only study investigating patients with Angelmann syndrome. The positive impact on sleep latency was also mainly led by two studies,27,31 again with the largest effect observed by Braam et al. 2008.31 Further studies with larger patient samples are needed to assess whether melatonin indeed provides a differential magnitude of effect across different disorders. Our sensitivity analysis further showed, that the positive impact on sleep latency was seen in studies of high risk of bias, whereas no effect was found in studies with low risk of bias, which underlines the need for further studies of high methodological quality. We explicitly sought to investigate the use of melatonin in children and adolescents presenting with underlying disorders beyond indication, thus excluding studies on patients primarily presenting with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD. Autism and/or neurodevelopmental disorders are however important comorbidities in several of the included disorders, such as Angelman syndrome, Rett syndrome and Dravet syndrome.35,36 Further studies are needed to assess whether autism spectrum disorder and/or ADHD as a comorbidity may have an impact on the subsequent effect of melatonin in these patients. There was a variation in how explicitly the use of concomitant medication was mentioned in the included studies. In five of the 13 studies, a different range of anti-epileptic drugs were applied, of which some are known to affect sleep. It remains to be assessed what impact concomitant medicine may have on the effect of melatonin. We found no effect on the remaining outcomes investigating benefits, including our primary outcomes on quality of sleep and general functioning. The general impact on quality of life was uncertain. Chronic insomnia is associated with an influence on daytime functioning. In accordance, we chose daytime functioning as one of the primary outcomes. Despite its importance, it is noteworthy that only two studies reported on this outcome25,27 and that pooled estimates showed no effect of melatonin. As such, the observed moderate improvement in sleep latency and total sleep time, for now, does not seem to translate into a clinical impact on daily functioning. Despite this, we still believe that melatonin may be tried for children and adolescents in which daytime functioning is affected, as the improvement in sleep continuity parameters may nevertheless provide some level of relief. Further studies investigating the impact of melatonin on daily functioning within a larger group of patients are highly needed.

We found that use of melatonin did not increase the number of patients experiencing serious—or non-serious adverse events. Data on safety was however scarce, as less than half of the studies provided data on this outcome, despite its importance. Only four studies explicitly reported on serious adverse events, whereas five studies reported on non-serious adverse events. Thus, the assessment of adverse events is based on few studies conducted across a range of different disorders, and each with small sample size. The discrepancy across studies should also be noted, as some found a significant increase in the number of patients experiencing non-serious adverse events, whereas others report that no adverse events were detected at any time in either the intervention or placebo group. None of the studies provided with an extensive list of the frequency and/or type of non-serious adverse events which had occurred throughout the trial. Instead, a list of the “most frequent type” of adverse events was provided. We are unable to make any assumptions as to whether this missing data is at random. The current scarcity in safety data calls for further systematic assessment of both serious- and non-serious adverse events in patient populations who present with chronic insomnia as a consequence of an underlying disorder. For now, it is unknown whether the adverse event profile may differ across disorders and thus we recommend that use of melatonin should be initiated and monitored by a medical specialist with knowledge of the underlying disorder. As presented elsewhere,15 pubertal development may not be influenced, yet due to the lack of data, it was not possible to investigate these claims further.

Our findings are similar to other systematic reviews, which also show a positive effect of melatonin on sleep latency and total sleep time, yet without the reviews providing information on quality of sleep or daytime functioning.37,38 Following subgroup analysis, we found that effects were comparable between fast-release and sustained-release formulations and increasing dosages above 5 mg did not seem to further improve outcomes. These subgroup results are based on few studies with high heterogeneity across trials, and thus further research is needed. Nevertheless, our subgroup findings align with current published expert opinions stating that prolonged-release formulations may not be superior to immediate release, and with the recommended dosage for children being 3 mg/nocte and 5 mg/nocte for adolescents.39,40 The timing of dosing across studies varied between 20 min and 2 h before bedtime. Timing of administration is of importance and depends on whether melatonin is administered as a chronobiotic (2–3 h before dim-light melatonin onset) or rather as a sleep inductor (30 min before bedtime).40 As such, the most appropriate timing of administration may likely differ across different disorders, which should be kept in mind if treatment with melatonin is initiated.

In all cases, chronic insomnia should initially be tried resolved by means of sleep hygiene practices and other non-pharmacological measures. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis showed that encouraging earlier bedtimes, may increase the total sleep time by 47 min in healthy children.41 It is noteworthy, that only 4 out of the 13 included studies reported that sleep hygiene practices had been tested prior to initiating treatment with melatonin. Healthcare decision-makers seeking to adopt this recommendation should be aware that access to non-pharmacological interventions may hinder the feasibility of implementation. Treatment with melatonin is off-label for all patients included in this review, which is something families should be made aware of if treatment is initiated. The decision to initiate off label treatment and the consequences this may have, is the responsibility of the prescribing clinician. In accordance, we recommend that treatment with melatonin should only be initiated and monitored by a specialist with knowledge of the underlying disorder.

Overall, we found evidence of low certainty showing a moderate clinical effect of melatonin on sleep continuity parameters, without it translating into an impact on daily functioning and quality of sleep, in patients presenting with chronic insomnia primarily due to underlying medical conditions. It remains to be investigated whether melatonin may provide a differential magnitude of effect and adverse event profile across different disorders. The long-term consequences still need further assessment. Based on a combined assessment, we provide a conditional recommendation for use of melatonin in children and adolescents aged 2–20 years, who despite optimisation of sleep hygiene practices, continue to present with difficulties in daily functioning, due to chronic insomnia attributed to an underlying disorder. The off-label use of melatonin for these patients should never be first choice of treatment, but may be considered by a medical specialist with knowledge of the underlying disorder, if non-pharmacological interventions have proven to be inadequate.

The strengths of this review include transparent methods and a comprehensive search strategy, with study selection performed by two independent reviewers. The work is based on a pre-specified, publicly available protocol. Limitations include language restrictions to English and Scandinavian languages. This was done to avoid any misinterpretation of results published in another foreign language. It is not known whether there may be additional relevant studies published in other languages. The authors of the included studies were not contacted in case of missing data. This may have been relevant for cross-over trials, as none of the trials included data from the first period. Thus, it is not possible to rule out potential cross-over effects in the data stemming from the cross-over trials. Few changes were made to the pre-specified protocol, as the age range was lowered from 5 to 2 years of age. This change was based on the clinical observation that children with underlying disorders may present with chronic insomnia already at such young age. The identified literature was re-evaluated in accordance with this change, to make sure all relevant studies had been included. The age range in the included studies assessed children and adolescents aged 1–26 years. Despite this slight discrepancy in age range, we still believe that the current evidence is representative of our pre-specified age range. We initially planned to assess outcomes after 2–4 weeks of commencing treatment. However, due to the few number of identified studies, we decided to also include studies that deviated from this timeframe. We initially planned to assess the frequency of serious—and non-serious adverse events, yet due to a lack of data in the included studies, this was changed to the number of patients experiencing serious—and non-serious adverse events. One of the main limitations of this review is the heterogeneity of the sample being investigated, which should be kept in mind when consulting the results.

Contributors

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study design: all authors, data collection: HEC, HKA; analysis of results: HEC, HKA; interpretation of results: all authors; construction of final recommendation: all authors; draft of manuscript: HEC, with input from HKA, MNH. HEC, HKA and MNH accessed and verified the underlying data. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Data and all other relevant material are publicly available at the Danish Health Authority website (www.sst.dk) or upon request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

LB is a member of the Danish medication Reimbursement Committee. AV has previously received honoraria for lectures at AGB pharma, Takeda & Medice and holds stocks at Novo Nordisk. All other authors declare no competing interests. Statements of conflicts of interests can be found for all members of the guideline panel, the external reviewer of the national clinical guideline, the reference–and project group at the Danish Health Authority website (www.sst.dk).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reference group, guideline panel and the secretary of the “National clinical recommendation for the use of melatonin in children and adolescents with chronic insomnia” published by the Danish Health Authority. The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, is supported by a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-18-774-OFIL).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102049.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wesselhoeft R., Rasmussen L., Jensen P.B., et al. Use of hypnotic drugs among children, adolescents, and young adults in Scandinavia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144(2):100–112. doi: 10.1111/acps.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bliddal M., Kildegaard H., Rasmussen L., et al. Melatonin use among children, adolescents, and young adults: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danish Health Authority . 2019. Guidance on medical treatment of children and young people with mental disorders.https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/retsinfo/2019/9733 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Danish Health Data Authority. 2014. Medstat.dk

- 5.Danish Health Authority . 2021. National clinical guideline on the treatment of children and adolescence with ADHD.https://files.magicapp.org/guideline/763f1abd-39fb-4721-914c-fb6504219971/published_guideline_4512-4_1.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danish Health Authority . 2021. National clinical guideline on the treatment of children and adolescence with Autism.https://files.magicapp.org/guideline/b51b9757-8c71-4b9c-b1d0-f1ce06e6d2f0/published_guideline_3992-1_0.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Kunz R., et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cumpston M., Li T., Page M.J., et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):148–160. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Danish Health Authority . 2022. National Clinical Recommendation for the use of melatonin to treat sleep problems in children and adolescents.https://files.magicapp.org/guideline/29d92ec7-7da4-4d84-974d-d26f397bd02d/published_guideline_5982-1_0.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sateia M.J. International classification of sleep disorders. Chest. 2014;146(5):1387–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Händel M.N., Andersen H.K., Ussing A., et al. The short-term and long-term adverse consequences of melatonin treatment in children and adolescents: a systematic review and GRADE assessment. eClinicalMedicine. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102083. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covidence systematic review software: veritas health innovation: Melbourne–Better systematic review management. 2014. covidence.ord

- 17.Higgins J.P.T., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7829) doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne J.A.C., Sutton A.J., Ioannidis J.P.A., et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7818) doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moberg J., Oxman A.D., Rosenbaum S., et al. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res policy Syst. 2018;16(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taghavi Ardakani A., Farrehi M., Sharif M.R., et al. The effects of melatonin administration on disease severity and sleep quality in children with atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29(8):834–840. doi: 10.1111/pai.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang Y.S., Lin M.H., Lee J.H., et al. Melatonin supplementation for children with atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):35–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M., Aneja S., Kohli K. Add-on melatonin improves sleep behavior in children with epilepsy: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(2):112–115. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta M., Aneja S., Kohli K. Add-on melatonin improves quality of life in epileptic children on valproate monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(3):316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain S.V., Horn P.S., Simakajornboon N., et al. Melatonin improves sleep in children with epilepsy: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Sleep Med. 2015;16(5):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasdell M.B., Jan J.E., Bomben M.M., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatonin treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome and impaired sleep maintenance in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Pineal Res. 2008;44(1):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodge N.N., Wilson G.A. Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders in children with developmental disabilities. J Child Neurol. 2001;16(8):581–584. doi: 10.1177/088307380101600808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coppola G., Iervolino G., Mastrosimone M., La Torre G., Ruiu F., Pascotto A. Melatonin in wake-sleep disorders in children, adolescents and young adults with mental retardation with or without epilepsy: a double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial. Brain Dev. 2004;26(6):373–376. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlow K.M., Kirk V., Brooks B., et al. Efficacy of melatonin for sleep disturbance in children with persistent post-concussion symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(8):950–959. doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braam W., Didden R., Smits M.G., Curfs L.M.G. Melatonin for chronic insomnia in Angelman syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(6):649–654. doi: 10.1177/0883073808314153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers K.A., Davey M.J., Ching M., et al. Randomized controlled trial of melatonin for sleep disturbance in Dravet syndrome: the DREAMS study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(10):1697–1704. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McArthur A.J., Budden S.S. Sleep dysfunction in Rett syndrome: a trial of exogenous melatonin treatment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(3):186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Castro-Silva C., De Bruin V.M.S., Cunha G.M.A., Nunes D.M., Medeiros C.A.M., De Bruin P.F.C. Melatonin improves sleep and reduces nitrite in the exhaled breath condensate in cystic fibrosis--a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Pineal Res. 2010;48(1):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lubbers K., Stijl E.M., Dierckx B., et al. Autism symptoms in children and young adults with fragile X syndrome, angelman syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, and neurofibromatosis type 1: a cross-syndrome comparison. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.852208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown A., Arpone M., Schneider A.L., Micallef S., Anderson V.A., Scheffer I.E. Cognitive, behavioral, and social functioning in children and adults with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei S., Smits M.G., Tang X., et al. Efficacy and safety of melatonin for sleep onset insomnia in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2020;68:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salanitro M., Wrigley T., Ghabra H., et al. Efficacy on sleep parameters and tolerability of melatonin in individuals with sleep or mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;139 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruni O., Angriman M., Calisti F., et al. Practitioner Review: treatment of chronic insomnia in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(5):489–508. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruni O., Alonso-Alconada D., Besag F., et al. Current role of melatonin in pediatric neurology: clinical recommendations. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19(2):122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magee L., Goldsmith L.P., Chaudhry U.A.R., et al. Nonpharmacological interventions to lengthen sleep duration in healthy children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:1084. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.