Highlights

-

•

Sentinel plot and commercial field monitoring reveals recent shifts in CLCuD complexes in Pakistan.

-

•

Evidence of altered prevalence of CLCuD-helper virus genomic variability.

-

•

Previously unreported CLCuD-associated plant host species discovered in cotton-vegetable and uncultivated species.

-

•

Early-detection predicted re-emergence of CLCuD-associated, cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Rajasthan.

Keywords: begomoviruses, cotton leaf curl disease, Geminiviridae, sentinel plot case study, whitefly vector

Abstract

A sentinel plot case study was carried out to identify and map the distribution of begomovirus-betasatellite complexes in sentinel plots and commercial cotton fields over a four-year period using molecular and high-throughput DNA ‘discovery’ sequencing approaches. Samples were collected from 15 study sites in the two major cotton-producing areas of Pakistan. Whitefly- and leafhopper-transmitted geminiviruses were detected in previously unreported host plant species and locations. The most prevalent begomovirus was cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu). Unexpectedly, a recently recognized recombinant, cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Rajasthan (CLCuMuV-Ra) was prevalent in five of 15 sites. cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV) and cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Kokhran, ‘core’ members of CLCuD-begomoviruses that co-occurred with CLCuMuV in the ‘Multan’ epidemic were detected in one of 15 sentinel plots. Also identified were chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus and ‘non-core’ CLCuD-begomoviruses, okra enation leaf curl virus, squash leaf curl virus, and tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus. Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) was the most prevalent CLCuD-betasatellite, and less commonly, two ‘non-core’ betasatellites. Recombination analysis revealed previously uncharacterized recombinants among helper virus-betasatellite complexes consisting of CLCuKoV, CLCuMuV, CLCuAlV and CLCuMuB. Population analyses provided early evidence for CLCuMuV-Ra expansion and displacement of CLCuKoV-Bu in India and Pakistan from 2012-2017. Identification of ‘core’ and non-core CLCuD-species/strains in cotton and other potential reservoirs, and presence of the now predominant CLCuMuV-Ra strain are indicative of ongoing diversification. Investigating the phylodynamics of geminivirus emergence in cotton-vegetable cropping systems offers an opportunity to understand the driving forces underlying disease outbreaks and reconcile viral evolution with epidemiological relationships that also capture pathogen population shifts.

1. Introduction

Cotton is the most important fiber and oil crop worldwide. In South Asia, commercial cotton production is at risk for infection by cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD), annually, since the initial outbreak in the early 1990s (Briddon & Markham, 2000). Cotton leaf curl disease is caused by one or more begomovirus species or strains, referred to as the ‘core’ CLCuD complex that consists of five begomoviruses and their strains, belonging to the genus, Begomovirus (family, Geminiviridae) (Brown, 2020). The genus Begomovirus contains the greatest number of species (>400) within the Geminiviridae (https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/). Worldwide, begomoviruses are transmitted by members of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) cryptic species group (de Moya et al., 2019) in a circulative, non-propagative manner (Brown & Czosnek, 2002). Begomoviruses have a circular DNA genome encapsidated in a twinned, icosahedral particle (Walker et al., 2021), and based on genome components, they are divided into two types, referred to as bipartite and monopartite. Most bipartite begomoviruses, or those that have two genomic components referred to as the DNA-A and DNA-B component, each of 2.5–2.7 kb in size, respectively, occur in the western hemisphere. The bipartite DNA-A component encodes the coat protein (CP) on the virion sense strand, with some species also encoding a pre-coat (AV2), while the replication-associated protein (Rep), transcriptional activator protein (TrAP), replication enhancer protein (REn), and AC4 protein (when present) are encoded on the complementary sense strand. The DNA-B component encodes the nuclear shuttle protein (NSP) and movement protein (MP) on the virion and complementary sense strands, respectively (Mansoor et al., 1999). In Asia, most begomoviruses have a monopartite genome, or DNA-A of ∼2.7-2.8 kb in size, and for the most part, the coding and non-coding regions of the monopartite genome are comparable to bipartite begomoviruses. In addition, most monopartite viruses are recognized as ‘helper viruses’ on which a type of non-viral molecule relies for replication, movement, encapsidation and whitefly transmission (Briddon & Stanley, 2006), referred to as betasatellites. Betasatellites have an adenine (A) rich region, a βC1 gene, and a highly conserved sequence of about 235 nucleotides known as the satellite conserved region (SCR). One or more helper begomoviruses can serve as the casual virus of cotton leaf curl disease, aided by at least one betasatellite (Mansoor et al., 2003a).

Symptoms of CLCuD are manifest as foliar- and vein-thickening, curling, shortening of internodes, development of enations (outgrowths) on the underside of the leaf, and overall stunting of the plant. The first major outbreak occurred in 1989-1990, when high incidences of leaf curl disease symptoms were observed throughout the Punjab Province, Pakistan. The initial CLCuD outbreak in Kokhran, a township near Multan from where it spread following widespread adoption of S-12, a cotton variety found to be highly susceptible to colonization by the whitefly vector, Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) cryptic species complex and CLCuD-begomoviruses (Zubair et al., 2017).

The causal agent of the 1990’s ‘Multan’ epidemic was identified as cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV), now referred to as the CLCuMuV–Faisalabad strain (CLCuMuV-Fai), and its associated cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) (Mansoor et al., 2003a). The CLCuMuV-Fai reached epidemic proportions and was spread by the whitefly vector to the major cotton-growing areas of Pakistan during the next several years. During the late 1990s, CLCuMuV-Fai-resistant commercial cotton varieties were released, and fiber production was restored to near pre-epidemic levels (Rahman et al., 2002). However, during 2001 the CLCuMuV-Fai-resistant varieties developed symptoms of leaf curl disease, initially in cotton fields in the tehsil of Burewala (Mansoor, Amin, et al., 2003). The causal agent was identified as a previously uncharacterized recombinant, named CLCuKoV-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu) and a previously unidentified-associated recombinant CLCuMuB (Amrao et al., 2010). The CLCuKoV-Bu and CLCuMuB complex spread throughout Punjab Province, displacing CLCuMuV, and becoming the predominant leaf curl strain associated with leaf curl disease in cotton throughout Pakistan, and in the nearby Rajasthan and Haryana states and in the Punjab region of India by 2012 (Rajagopalan et al., 2012). Previous studies have identified begomoviruses from cotton plants exhibiting leaf curl symptoms in Pakistan and India, including cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus- Kokhran (CLCuKoV-Ko), cotton leaf curl Multan virus- Rajasthan (CLCuMuV-Ra), papaya leaf curl virus (PaLCuV), and tomato leaf curl Bangalore virus (ToLCBaV) (Briddon & Markham, 2000; Mansoor et al., 2003a; Zhou et al., 1998) and a satellite-like molecule cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) (Briddon et al., 2003, 2014). Unexpectedly, geminiviruses previously considered to restricted to vegetable crop hosts, have been identified from cotton exhibiting leaf curl disease. Among them, tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV) and chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus were detected in mixed infection with CLCuKoV-Bu in cotton plants (Manzoor et al., 2014; Zaidi et al., 2016).

The genomic variability, geographical- and host-distribution, and the phylodynamics of geminivirus-betasatellite complexes was investigated in cotton-vegetable agroecosystems in the major cotton producing areas in Pakistan. Leaf samples of suspect and previously recognized plant hosts were collected from cotton, vegetable, ornamental, and uncultivated or ‘wild’ plants/weeds during sentinel plot and field surveys. Fifteen study sites in the Punjab and Sindh Provinces with a prior history of leaf curl epidemics were sampled annually, June to September. Also, symptomatic leaf samples were collected from commercial cotton fields in 2017 during a routine survey in Vehari (Punjab Province). Full-length geminivirus genome (n=236) and betasatellite (n=411) sequences were determined from symptomatic cotton and non-cotton samples. Their relative frequency and distribution were compared with results of previous CLCuD-surveys conducted from ∼1990-onward, the timeframe during which two historical outbreaks reached epidemic proportion in Pakistan, caused by ‘Multan’ (CLCuMuV-Fai) and ‘Burewala’ (CLCuKoV-Bu), respectively. Based on preliminary reports of a suspected, impending third outbreak species detected at low frequency in cotton fields in 2015 (Zubair et al., 2017), samples of symptomatic cotton leaves were collected in the vicinity of Vehari (Punjab Province) in 2017. Sequencing results revealed the prevalence of CLCuMuV-Ra, a strain now recognized as the causal begomovirus associated with the third cotton leaf curl disease in Pakistan and in some locations in India (Ahmed et al., 2021).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation and maintenance of sentinel plots

Sentinel plots (276 × 236 ft) were established and sampled from 2010 to 2014 at study sites located in Lahore, Multan, and Vehari. The main cotton-producing regions in Pakistan are near Multan and Vehari, whereas, in Lahore, cotton is cultivated on a smaller scale. Known or suspect begomovirus plant hosts were planted in sentinel plots to bell pepper, chili, cotton, cucumber, okra, sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica), squash, and tomato.

Selected cotton varieties, or ‘differentials’ that are known to be differentially susceptible to cotton leaf curl disease complex species and strains, respectively. These observations are on official reporting from official government records, the plant breeding community, and are acknowledged by farmers. The differentials selected for planting in sentinel plots were: MNH886, MNH814, MNH786 and CIM496. In addition, uncultivated, or ‘wild’ plant species (Table S1-S3) growing in the vicinity of sentinel plots were encouraged to flourish within or nearby the sentinel plots to attract natural whitefly infestation and recruit cotton leaf curl disease-associated as well as other prospective plant viruses in the environment. The sentinel plot locations were selected as the study sites to represent different geographical locations within the districts of the two most important provinces Punjab and Sindh, where cotton is produced in Pakistan.

2.2. Sample collection and nucleic acid isolation

Leaf samples exhibiting symptoms reminiscent of leaf curl disease (Figure S1) were collected from the sentinel plots established for the project and from commercial cotton fields. Samples were collected early and late during the regular cotton-growing season, beginning when the cotton ‘differentials’ planted in sentinel plots reached the 12-14 leaf stage. Sentinel plots and commercial cotton fields were surveyed for symptoms characteristic of begomoviral infection. Samples were collected from sentinel plots established in Vehari, Multan and Lahore planted to cotton, vegetable crops, and wild plant species (uncultivated/weeds), cotton-breeding plots located in Vehari, Multan and Sakrand, and commercial cotton fields in the Punjab and Sindh Provinces. Commercial cotton fields in the Punjab province were located in Bahawalnagar, Bahawalpur, Burewala, Dera Ghazi Khan, Faisalabad, Layyah, Lodhran, Multan, Muzaffargarh, Rahimyar Khan, Sahiwal, and Vehari, whereas the fields in the Sindh Province were located in Ghotki and Sakrand. During 2017, symptomatic cotton leaf samples were collected from several commercial cotton fields near Vehari, Punjab province.

Newly developing leaves of cotton plants exhibiting characteristic leaf curl disease symptoms were collected from cotton, vegetables, and alternate hosts growing near cotton fields. Leaf samples were transported in an ice-chest to the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences (University of the Punjab, Lahore) and stored at -20°C or -80°C. Total nucleic acids were isolated from 100 mg of leaf tissue per plant sample using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Doyle and Doyle, 1990). Purified DNA was shipped by international courier (under APHIS PPQ permit to J.K.B.) to the School of Plant Sciences (The University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). To identify the most prevalent geminiviruses and betasatellites, DNA were analyzed by rolling circle amplification (RCA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, cloning, and Sanger sequencing, and/or by high throughput ‘discovery’ DNA sequencing (HTS).

2.3. DNA sequencing, assembly and geminivirus-betasatellite identification

Total nucleic acids were subjected to rolling-circle amplification (RCA) of circular DNA using the Illustra TempliPhi Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The enriched DNA was digested with selected restriction enzymes, EcoRI, HindIII, KpnI, NcoI, PstI, SacI, SalI, XbaI, and XhoI (ThermoFisher Scientific) to obtain a ∼2.8 kilobase pair (kbp) for geminiviral genomes and ∼1.4 kbp for satellite molecules. A fragment of the expected size, corresponding to a full-length geminiviral genome (2.8 kbp) or betasatellite molecule (half unit length, 1.4 kbp), were cloned into the plasmid vector pGEM TM-3ZF(+) (ThermoFisher Scientific), pre-digested with the respective enzyme compatible for the cloned insert. Plasmids containing an insert of the expected size were subjected to capillary DNA (Sanger) sequencing at The University of Arizona Genetics Core (UAGC) facility (Tucson, USA). The RCA-enriched DNA samples that did not yield a digested betasatellite product were used as template for PCR amplification (Brown et al., 2017) with degenerate primers (Zia-Ur-Rehman et al., 2013). The amplicons were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy plasmid vector (Promega) and subjected to capillary DNA (Sanger) sequencing. Provisional identification was determined by BLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) analysis (similarity) of sequences available in the GenBank database. To establish begomovirus and betasatellite species identity, pairwise distance analysis was carried out using the SDT v1.2 algorithm (Muhire et al., 2014). Further, samples were subjected to ‘discovery’ DNA sequencing (n=∼285 samples) with the Illumina Hi-Seq platform. Library construction, quantification, and sequencing were carried out at the University of Arizona Genetic Core, Tucson, USA. The nucleotide reads were assembled de novo with SPAdes (Bankevich et al., 2012) and NCBI BLASTn, respectively. Assembly of geminivirus- and betasatellite reads was carried out using the de novo assembly software SOAPdenovo2 (Luo et al., 2012). Provisional identification was determined using BLASTn against the sequences available in the GenBank database, as described above. Representative full-length geminiviral-betasatellite sequences were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database. The Accession numbers are provided in Table S1. The nomenclature adheres to most recent guidelines published by the Geminiviridae Study Group, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (Zerbini et al., 2022)

2.4. Population expansion analysis of cotton leaf curl viruses

Population expansion analysis of full-length begomoviral genome sequences was carried out using the Tajima's D (Tajima, 1989), Fu, and Li's tests (Fu & Li, 1993). Full-length sequences were aligned with the MUSCLE algorithm (Edgar, 2004) and analyzed individually with DNASP Tajima's D, Fu and Li's F, and Fu and Li's D algorithms, respectively (Simonsen et al., 1995).

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses were carried out by comparing sequences determined in this study with representative core and non-core geminivirus and betasatellite references available in the NCBI GenBank database. Representative begomovirus and betasatellite reference sequences were selected from well-known isolates representing prevalent and rare species and strains (Brown lab curated database). Reference sequences for previously identified recombinants of CLCuMuB were selected based on historical descriptions (Akhtar et al., 2014; Amin et al., 2006; Zubair et al., 2017).

The species and strain identifications of helper virus and betasatellite sequences reported here were assigned based on the results of pairwise nucleotide identity analysis using SDT software (Muhire et al., 2014), and in consultation with the 2021 ICTV master species list, version 3 (https://ictv.global/msl).

Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) in Geneious Prime (v2021.2.2) software (https://www.geneious.com). Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the Maximum likelihood (ML) method in RAxML-HPC2 using the XSEDE command in the CIPRES portal https://www.phylo.org/) (Miller et al., 2010) and the trees was reconstructed using the GTRGAMMA phase model, with 1000 bootstrap iterations. When many sequences shared high nucleotide identity based on SDT analysis, the groups that clustered in the same clade or sub-clade were collapsed to enable visualization of the rarer relationships on the tree. The ML trees were drawn with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and manual editing was carried out in Inkscape (http://www.download3.co/ic2/inkscape/index.php?kw=inkscape%20software).

2.6. Recombination analysis

The full-length genome sequences of CLCuAlV (n=29), CLCuKoV (n=382), and CLCuMuV (n=163) were aligned (MUSCLE) with representative begomoviral taxa as reference sequences (GenBank) and subjected to recombination analysis using RDP software, version 5.05 that consists of the software suite: Geneconv, Bootscan, Maximum Chi Square, Chimaera, Sister Scan and 3Seq algorithms (Martin et al., 2021). Results were considered statistically significant, for P-values lower than the Bonferroni-corrected α=0.05 cut-off. Similarly, recombination analysis of betasatellite sequences was carried out using representative betasatellite as references (GenBank). Only predicted recombination events that were statistically supported by all seven algorithms are reported here.

3. Results

3.1. Cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala and cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite prevalence

Commercial cotton fields in 15 study sites in the Punjab and Sindh Provinces were surveyed for cotton leaf curl disease symptoms to guide sample collection. The results of a routine follow-up 2017 sampling of commercial cotton fields in Vehari are also reported here. Both full-length and partial sequences of begomovirus and betasatellite genomes resulted from PCR amplification and sanger sequencing of the cloned amplicons, and/or those determined from Illumina ‘discovery’ sequencing were considered in the BLASTn analysis conducted to establish provisional identification and are reported as prevalence data archived in the project database (available on request). Only full-length geminivirus and betasatellite sequences were considered in the pairwise distance, phylogenetic, and recombination analyses reported here (Fig. 1). The sequences for isolates occurring in symptomatic cotton plants were assembled into 236 full-length genomes. Virus isolates for which full-length genome sequences were determined were identified to species and strain by pairwise percentage nucleotide identity analysis using the SDT algorithm and representative reference sequences available in GenBank (Brown et al., 2015; Muhire et al., 2014).

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of cotton-infecting geminiviruses identified in cotton plants sampled from sentinel plots and commercial cotton fields at the study sites in Pakistan during 2010-2014 and from Sahiwal during 2017. The virus sequences were determined by cloning and sequencing, followed by Sanger sequencing and/or by Illumina DNA sequencing. Isolates are represented by full-length sequences (n=236) of different species and strains. Viral species were identified as chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus (CpCDV), chili leaf curl virus (ChLCV), cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus (CLCuKoV), squash leaf curl virus (SLCV), and tomato leaf curl new Delhi virus (ToLCNDV). The different viral species are color-coded by species and the number of sequences per species in each geographical location is indicated parenthetically.

The CLCuKoV-Bu was identified as the most predominant cotton-infecting species identified, occurring at all 15 study sites for the four-year study (Fig. 1). Somewhat unexpectedly, CLCuMuV, the primary causal agent of the Multan epidemic in Pakistan (1990’s) was identified in cotton plants and in several other host species at five of the fifteen study sites, in Multan and Vehari districts of the Punjab Province, and the Ghotki and Sakrand districts in the Sindh Province. Several other begomoviruses, CLCuKoV-Ko in Sahiwal (Punjab) and CLCuAlV in Multan (Punjab) that occurred at low prevalence during the Multan epidemic era were also detected in this study (Fig. 1). Finally, follow-on sampling in 2017 from commercial cotton fields in Sahiwal (Punjab) near Vehari district revealed the occurrence of CLCuMuV-Rajasthan strain(CLCuMuV-Ra), first reported infecting cotton plants at a low frequency in Pakistan and India in 2000s (Kirthi et al., 2004; Shahid et al., 2007).

In this study, several geminiviruses previously unassociated with leaf curl disease in cotton were identified for the first time, and included the leaf hopper transmitted mastrevirus, chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus (CpCDV) and the bipartite begomovirus, ToLCNDV, both which have been previously, widely reported from different vegetable crop species (Table S3) (Manzoor et al., 2014; Zubair et al., 2017). Further, several geminiviruses were identified infecting cotton and in previously unreported locations for the first time. The ToLCNDV was detected in cotton plants in Burewala, Layyah, Multan, and Vehari, while CpCDV was identified in Multan and Rahim Yar Khan (Fig. 1), and the New World squash leaf curl virus (SLCV), a bipartite begomovirus endemic to the southwestern U.S and Mexico, was detected in cotton plants in Multan and Layyah. A number of vegetable and weed species have been reported as CLCuKoV and CLCuMuV hosts in Pakistan. In this study, CLCuAlV was detected from okra plants for the first time from a commercial field (Bahawalpur) and the sentinel plot in Burewala (Table S3). And in Sahiwal, the CLCuKoV-Ko, was detected in symptomatic cotton plants, which has not been reported since the ‘Multan’ epidemic, underscoring the persistence of this historical isolate in a major cotton-growing district in the Punjab Province. Finally, diverse betasatellite species and variants were detected in symptomatic cotton plants in this study (Fig. 2) and included cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) (15 of 15 locations), bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite (BYVMB) (Multan, Lahore, Vehari, Sakrand) and chili leaf curl betasatellite (ChLCuB) (Vehari) co-occurred in cotton with previously recognized ‘core’ CLCuD begomoviruses (Table S1). The full-length geminivirus helper genome and representative betasatellite sequences were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database. Sample information, isolate identification, and the GenBank Accession number for each sequence are provided (Table S1-S2).

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of betasatellites (n=411; full-length sequences) identified in cotton samples from sentinel plots and commercial cotton fields at study sites in Pakistan during 2010-2014, and from Sahiwal during 2017. Betasatellite identification was based on alignment of PCR-amplified, cloned virus/betasatellite sequences (Sanger or Illumina sequencing) with selected GenBank reference sequences. The betasatellites were identified as bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite (BYVB), chilli leaf curl betasatellite (ChLCuB), and cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB), and are color-coded by species, with the number of sequences per species by geographical location indicated parenthetically.

3.2. Viruses associated with previously or recently unreported symptomatic host plant species

Identification of geminivirus species associated with symptomatic sentinel plot plant species revealed the frequent detection of CLCuKoV-Bu in cotton differentials established in sentinel plots to recruit begomovirus species from the ‘environment’ (Tables 1, 3). During the four-year sampling period, among the 105 isolates detected, 94 (89%) were identified as CLCuKoV-Bu, whereas the minor species identified were CLCuAlV, OELCuV and ToLCNDV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Begomoviruses detected in leaf curl cotton differentials in sentinel plots located in Lahore, Multan, and Vehari, were identified as cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu), okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV), and tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV). The number of isolates identified, per host species, is indicated parenthetically.

| Plant host | Location | Virus |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton | Lahore | CLCuKoV-Bu (4) |

| Cotton | Lahore | CLCuKoV-Bu (9), OELCuV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuKoV-Bu (10), ToLCNDV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuKoV-Bu (4), CLCuAlV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuKoV-Bu (5), ToLCNDV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuKoV-Bu (8) |

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (11), ToLCNDV (1), OELCuV (1) |

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (2) |

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (37) |

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (4) |

Table 3.

Viruses identified in commercial symptomatic cotton fields in Multan, Sakrand, and Vehari, were identified as chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus (CpCDV), cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Shahdadpur (CLCuKoV-Sha), cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Rajasthan (CLCuMuV-Ra), squash leaf curl virus (SLCV), and tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV).

| Host | Location | Virus |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (1) |

| Cotton | Vehari | CLCuKoV-Bu (6), CLCuMuV-Ra (3), CpCDV (1) |

| Cotton | Sakrand | CLCuKoV-Bu (1), CLCuMuV-Ra (2) |

| Cotton | Sakrand | CLCuKoV-Bu(1),CLCuKoV-Sh(1),CLCuMuV-Ra(2), ToLCNDV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuAlV (3), SLCV (1) |

| Cotton | Multan | CLCuKoV-Bu (1) |

Several begomoviruses and/or a mastrevirus were detected in sentinel plot plants at a relatively low frequency, respectively (Tables 2, 4), and were identified as: CLCuKoV-Bu in L. cylindrica (Zia-Ur-Rehman et al., 2013), squash, and cucumber, CpCDV from tomato (Zia-Ur-Rehman et al., 2015), okra (Zia-Ur-Rehman et al., 2017) and cucumber (Hameed et al., 2017), okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV) from cotton (Hameed et al., 2014), CLCuAlV from cotton and okra, and ToLCNDV from cotton and vegetable crops.

Table 2.

The begomoviruses detected in vegetable and weed species, in or nearby sentinel plots in Lahore, Multan, and Vehari, were identified as cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu). The number of isolates representing the different viruses is indicated parenthetically.

| Virus | Location | Host |

|---|---|---|

| CLCuKoV-Bu | Lahore | Okra (1) |

| CLCuKoV-Bu | Vehari | Okra (1), Luffa (1) |

| CLCuKoV-Bu | Vehari | Squash (1), Cucumber (1) |

| CLCuAlV | Multan | Okra (1) |

| CLCuAlV | Multan | Okra (1) |

| CLCuAlV | Multan | Okra (1) |

| CLCuAlV | Vehari (Burewala) | Okra (1) |

Table 4.

The geminiviruses identified in mixed infections in cotton, vegetable, and weed species in or near the established sentinel plots and commercial cotton field sampled were bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus (BYVMV), cherry tomato leaf curl virus (CToLCV), chickpea chlorotic dwarf virus (CpCDV), chili leaf curl virus (ChLCuV), cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Shahdadpur (CLCuKoV-Sha), cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Rajasthan (CLCuMuV-Ra), okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV), pedilanthus leaf curl virus (PeLCV), squash leaf curl virus (SLCV), squash leaf curl China virus (SLCCNV), tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV), and okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV).

| Host | Location | Sample Type | Virus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okra | Multan | Sentinel | CLCuAlV, OELCuV |

| Okra | Lahore | Sentinel | BYVMV, OELCuV |

| Cucumber | Burewala | Sentinel | SLCCNV, ToLCNDV |

| Cucumber | Vehari | Sentinel | CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV |

| Okra | Burewala | Sentinel | BYVMV, CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuAlV |

| Okra | Lahore | Sentinel | CLCuKoV-Bu, BYVMV |

| Chili | Multan | Sentinel | ChLCuV, ToLCNDV |

| Bitter gourd | Multan | Sentinel | CLCuAlV, ToLCNDV |

| Cotton | Multan | Sentinel | CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV, CToLCV |

| Cotton | Layyah | Field | CLCuKoV-Bu, SLCV |

| Cotton | Multan | Field | CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV |

| Cotton | Multan | Field | CpCDV, ToLCNDV |

| Cotton | Vehari | Field | CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV |

| Cotton | Multan | Field | CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV |

| Okra | Arifwala | Field | CLCuAlV, BYVMV |

| Okra | Bahawalpur | Field | CLCuAlV, OELCuV, ToLCNDV |

|

Duranta repens |

Lahore | Field | PeLCV, ToLCNDV, CLCuAlV |

| Cotton | Vehari | Germplasm | CLCuAlV, CpCDV |

| Cotton | Sakrand | Germplasm | CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuMuV-Ra |

Twenty-four complete genome sequences were determined for isolates from symptomatic commercial cotton fields sampled in Multan, Vehari and Sakrand, and identified as CLCuAlV, CLCuKoV-Bu, SLCV, ToLCNDV, whereas one isolate was identified as the mastrevirus, CpCDV (Table 3).

3.3. Mixed geminivirus infections

Geminiviruses commonly occur in mixed infections in the same host plant, an observation that suggests they do not cross-protect against one another. Exploiting this unusual feature among plant viruses has facilitated inter-specific, and intra-specific recombination as well as recombination between different genera, which in turn, promotes geminivirus diversification and adaptation to new environmental challenges (Rybicki, 1994).

In this study, mixed geminivirus infections were detected routinely in sentinel plot and commercial cotton fields (Table 4) in bitter gourd, chili, cotton, cucumber, and okra plants. In the sentinel plots CLCuAlV and ToLCNDV were co-occurring in bitter gourd plants, while chili leaf curl virus (ChLCuV) and ToLCNDV were detected in chili plants. The CLCuKoV-Bu, ToLCNDV, and cherry tomato leaf curl virus (CToLCV) were identified in cotton and a new strain of PaLCV was discovered for the first time (Table S3). Also, in cucumber plants CLCuKoV-Bu, squash leaf curl China virus (SLCCNV), and ToLCNDV were co-existing, while bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus (BYVMV), CLCuAlV, and OELCuV occurred in mixed infection in okra plants. Similarly, in commercial cotton fields, mixed infections were common, and involved CLCuKoV-Bu and ToLCNDV, or CLCuKoV-Bu, SLCV, or CLCuAlV, or CLCuMuV with either BYVMV, CpCDV, OELCuV, pedilanthus leaf curl virus (PeLCV) (proposed new strain of PaLCV) Table S3), and ToLCNDV, (partial sequences, not shown). Finally, mixed infection was detected in commercial okra fields consisting of BYVMV and/or OELCuV with ToLCNDV.

3.4. Comparison of the host range of cotton leaf curl complex identified in this study with previously published records

A literature search of all previously reported hosts of CLCuD revealed that in addition to cotton, geminivirus-betasatellite complexes have been associated with diverse vegetable crop and wild plant species, with the potential to serve as persistent or transient disease reservoirs (Table S3).

Among the plant species sampled in this study, cotton harbored the greatest number of geminiviruses, which consisted of BGYMV, CLCuAlV, CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuKoV-Ko, CLCuMuV-Dar, CLCuMuV-Ra, CLCuMuV-Sha, CpCDV, hollyhock leaf curl virus (HoLCV), OELCuV, pedilanthus yellow leaf curl virus (PeYLCV), and SLCV. In contrast, okra plants harbored the second largest number of geminiviruses, which consisted of BYVMV, CLCuAlV, CLCuKoV-Bu, and OELCuV. All of the latter viruses have been previously reported from cotton and okra (Table S3). The most prevalent begomovirus detected from cotton and vegetable crops was CLCuKoV, which was detected from symptomatic chili, cotton, cucumber, holly hock, luffa, okra, papaya, soybean, Ricinus sp., squash, Xanthium sp. bean and several ornamental plants (Table S3). Interestingly, the previously recognized CLCuMuV-Pakistan (CLCuMuV-Pk) and CLCuMuV-Fai strains were prevalent in cotton and Sida sp. plants, whereas, the CLCuAlV species was detected exclusively in cotton and okra plants, and the CLCuKoV-Ko species was found in one cotton sample. Among the geminiviruses reported in this survey, ToLCNDV exhibited the most extensive host range. The ToLCNDV host plants consisted primarily of bitter gourd, chili, cotton, squash, ornamentals, and uncultivated (wild) species (partial sequences were not included in the phylogenetic or SDT analyses) (Table S3). Also, several plant species identified as begomovirus hosts in this study, have previously been reported (Table S3). However, several previously unreported species were identified as begomovirus hosts, including HoLCV and PeLCV detected in cotton, PaLCV in Croton sp., CLCuKoV-Bu, SLCCNV, and ToLCNDV in cucumber, CLCuAlV and CLCuKoV-Bu in okra, CLCuMuV in Sida sp., and CLCuKoV-Bu in squash (Table S3).

3.5. Recombination analysis of geminiviruses and betasatellites

Recombination analysis for CLCuKoV (n=382), CLCuMuV (n=163), and CLCuAlV (n=29) using RDP5 (Martin et al., 2021), predicted events supported by all seven algorithms (Fig. 3) identifying one or more events among ‘core’ leaf curl species. Two major predicted recombination events were identified in the coat protein (cp) coding region, involving recombination between different isolates of CLCuKoV-Bu. The breakpoints for event 1 were located at nucleotide coordinates 180-1132, and involved 215 of 382 CLCuKoV-Bu isolates, whereas the event 2 breakpoints were located at nucleotide coordinates 219-731 involving 39 CLCuKoV-Bu isolates. Further, six additional recombination events were predicted among CLCuMuV isolates (Figure 3; events 3 to 8). These consisted of events 5 and 6, predicted in the cp with breakpoints located at nucleotide coordinates 327 – 887, and at 449 – 871, for 19 and 39 of 163 isolates, respectively. Four events were predicted in rep, of which 3 (event no. 3,4 and 7) involved CLCuMuV and CLCuKoV-Bu with breakpoints at nucleotide coordinates 1509 –2720, 1660–2221 and 1857–2397 respectively. Events 3 and 4 involved 52 isolates each, and Event 7 involved 12 of 163 CLCuMuV isolates. A fourth event, enumerated as 8, predicted recombination within the CLCuMuV rep coding region for 46 isolates, with breakpoints at nucleotide coordinates 1834-2218. Importantly, the minor parent involved in this predicted recombination event was CLCuKoV-Ko.

Fig. 3.

Predicted recombination events involving cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu) (Events 1 and 2), cotton leaf curl Multan Virus (CLCuMuV) (Events 3 to 8), cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus- Kokhran (CLCuKoV-Ko) (Event 9) and cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (CLCuAlV) (Event 10). For each event, the number of predicted recombinants is indicated parenthetically. For reference, the characteristic genome organization of a monopartite begomovirus is provided for reference, at the top of the figure.

Two additional predicted recombination events, 9 and 10, involved CLCuKoV-Ko and CLCuAlV. Here, the CLCuKoV-Ko isolates detected in cotton plants harbored predicted recombinants between CLCuKoV-Ko (major parent) and CLCuKoV-Bu (minor parent), with breakpoint positions at nucleotide coordinates 1861-2729. Also, among the seven CLCuAlV isolates identified in this study, two were predicted recombinants that harbored a fragment of CLCuMuV cp, with breakpoints at nucleotide coordinates 540-949. (Fig. 3).

Recombination analysis of the betasatellite sequences revealed several predicted recombination events. Among CLCuMuB isolates, a number of predicted recombination sites involved breakpoints located within the satellite-conserved region (SCR). Thirty-three of these were predicted recombinants of Tomato leaf curl Rajasthan betasatellite (ToLCuRaB, KP892648), and all SCR region (∼235nt) recombinants were contributed by a ToLCuRaB (minor parent). Isolates of the newly emergent ToLCuRaB, reported herein, were previously classified as two taxa, referred to as tomato leaf curl betasatellite (ToLCuB) and/or chili leaf curl betasatellite (ChLCuB) (2016) (Briddon et al., 2017). However, based on pairwise distance analysis (SDT v1.2 algorithm) (Muhire et al., 2014) (datasheet S3) they have been merged into one taxon, named ToLCuRaB, with the ICTV code 2020.009P (Fiallo-Olivé & Navas-Castillo, 2020). Two BYMB isolates from cotton were predicted recombinants of CLCuMuB (minor parent), with the breakpoints located at nucleotide coordinates 843-1158, a region containing part of the A-rich region and of the SCR.

3.6. Expansion analysis of cotton leaf curl viruses

The Tajima's D test, which provides an estimate of genetic diversity and population expansion or contraction, was used to analyze the three most prevalent begomoviral species genomes, CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuMuV-Fai, and CLCuMuV-Ra that includes CLCuKoV-Bu and CLCuMuV-Ra, which were responsible for the second epidemic and the third or current outbreak, respectively (Table 5). Two of the three viruses, CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuMuV-Ra showed signals of population expansion, while significantly negative values were assigned to CLCuMuV-Fai, the causal begomovirus of the Multan epidemic.

Table 5.

Genetic diversity among cotton leaf curl viral genomes estimated by Tajima's D, Fu, and Li's D, and Fu & Li's F tests. The number of plant samples associated with each begomoviral genome is shown parenthetically, for cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Burewala (CLCuKoV-Bu), cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Faisalabad (CLCuKoV-Fai), cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Rajasthan (CLCuKoV-Ra).

| Virus (No. of sequences) |

Tajima's D | Fu & Li's D | Fu & Li's F |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLCuKoV-Bu (292) | -2.65709 (p < 0.001) |

-9.56213 (p < 0.02) |

-6.91397 (p < 0.02) |

| CLCuMuV-Fai (56) | -1.99661 (P < 0.05) |

-3.14670 (P < 0.05) |

-3.23268 (P < 0.02) |

| CLCuMuV-Ra (22) | -2.48720 (P < 0.001) |

-3.63838 (P < 0.02) |

-3.84498 (P < 0.02) |

3.7. Phylogenetic analysis of full-length ‘core’ cotton leaf curl virus genomes

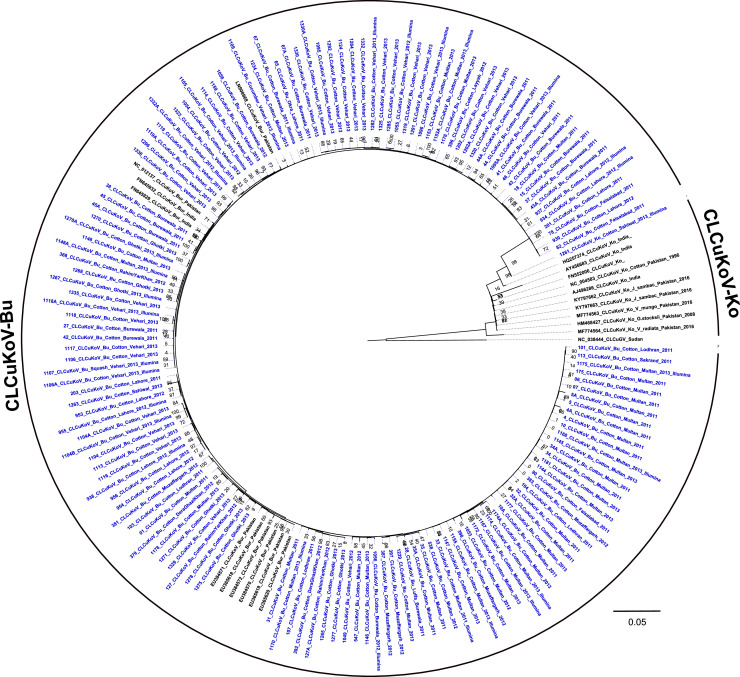

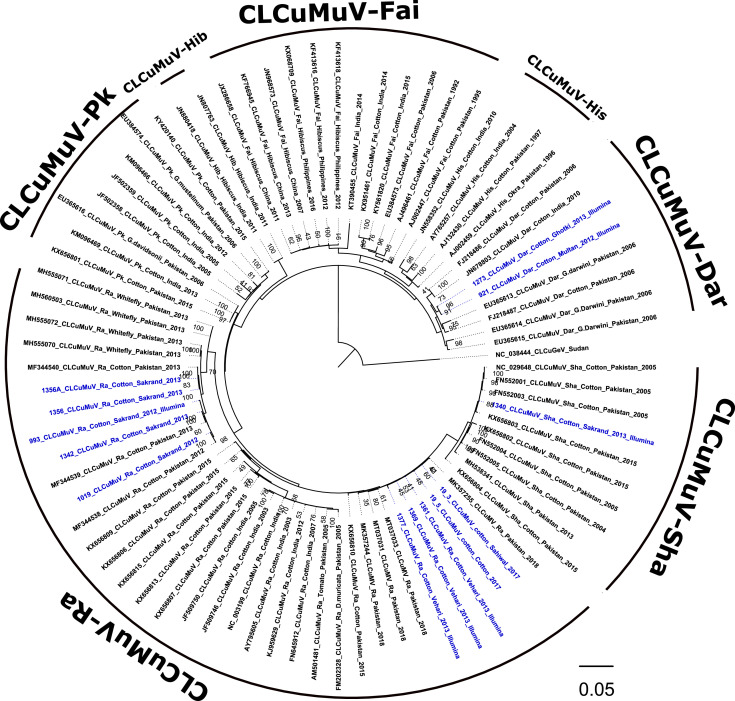

Phylogenetic analysis of the full-length genome sequences and representative GenBank sequences that included the CLCuD-associated ‘core’ species, CLCuKoV and CLCuMuV and strains thereof, CLCuKoV-Bu, CLCuKoV-Ko and CLCuMuV-Darwini (CLCuMuV-Dar), CLCuMuV-Fai, CLCuMuV-Hibiscus (CLCuMuV-Hib), CLCuMuV-Hisar (CLCuMuV-His), CLCuMuV-Pk, CLCuMuV-Ra, CLCuMuV-Sha respectively. In addition to representing the historically recognized CLCuD-associated virus strains, several were identified in this study. Phylogenetic analysis (ML) of the full-length CLCuKoV-Bu genome sequences indicated that all were closely related to previously-documented CLCuKoV-Bu isolates (Fig. 5). Only one isolate of CLCuKoV-Ko (1261_CLCuKoV-Ko_Sahiwal_2013) grouped in the sister clade that also contained an isolate of CLCuKoV-Ko (HQ257374) from India. Further, this relationship was supported by the pairwise distance analysis that showed the two isolates shared 97.6% nucleotide identity. The latter two CLCuKoV-Ko isolates grouped most closely with members of the CLCuKoV-Bu clade that harbored isolates identified as the same strain, despite low bootstrap support (16%), suggesting they could be recombinant sequences. Previously, Cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus-Shahdadpur (CLCuKoV-Sha) was considered a recognized strain of CLCuKoV (Brown et al., 2015). Based on a sequence comparison with other CLCuKoV-Sha-like GenBank references, the isolate (herein) was determined to be a strain of CLCuMuV, based on 95.6% and 91-93.4%shared nucleotide identity with CLCuMuV (MG373556) and CLCuKoV (KY797661, HQ257374), respectively. This CLCuMuV isolate was therefore included in the CLCuMuV species-specific phylogenetic analysis of isolates and strains of CLCuMuV identified here, with representative sequences available in the GenBank database (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

The cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus (CLCuKoV) tree was reconstructed by Maximum likelihood analysis using 1000 bootstrap iterations for 146 sequences of the isolates determined in this study (blue-colored font) and selected GenBank reference sequences (n=21). The CLCuKoV isolates were identified to the species and strain level, respectively, based on pairwise distance analysis with the SDT v1.2 algorithm. The tree was rooted with the cotton leaf curl Gezira virus (CLCuGeV) sequence, Accession no. NC038444, endemic to sub-Saharan Africa.

Fig. 6.

The cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV) tree was reconstructed by Maximum likelihood analysis using 1000 bootstrap iterations for 11 sequences of isolates determined in this study (blue-colored font) and selected GenBank reference sequences (n=63). The CLCuMuV isolates were identified to the species and strain level, respectively, based on pairwise distance analysis with the SDT v1.2 algorithm. The tree was rooted with the cotton leaf curl Gezira virus (CLCuGeV) sequence, Accession no. NC038444, endemic to sub-Saharan Africa.

Phylogenetic analysis (Maximum Likelihood) of the full-length genome CLCuMuV sequences (determined here) grouped with representative GenBank reference sequences for the three recognized CLCuMuV strains, CLCuMuV-Sha, CLCuMuV-Ra and CLCuMuV-Dar. Thus, all CLCuMuV isolates identified in this study were similar to those reported previously from cotton in Pakistan and/or India (Fig. 6). However, the CLCuMuV-Ra isolates exhibited some extents of divergence, with the isolates from Vehari and Sahiwal (Punjab Province) grouping separate from the Sakrand isolates (Sindh Province), while the Vehari isolates grouped with reference GenBank Accessions reported in 2021 (Ahmed et al., 2021). The CLCuMuV-Ra, Punjab isolates shared 99.5-99.7% pairwise nucleotide identity with GenBank Accessions (MK357244, MK357255, MT037031, MT037033), compared to Sakrand isolates of CLCuMuV-Ra field isolates that exhibited the greatest divergence, with 93.9- 94.4% pairwise nucleotide identity with available CLCuMuV-Ra Pakistan isolates (n=48).

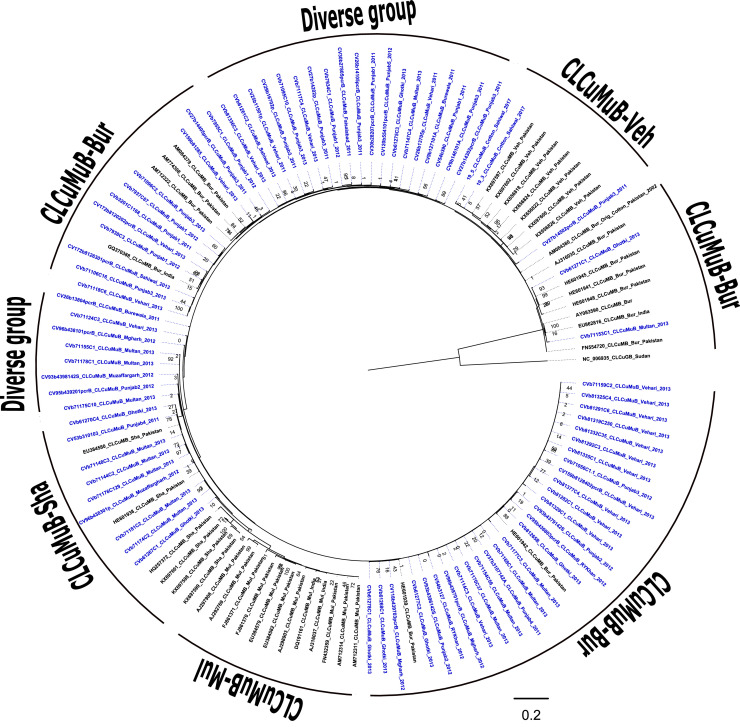

3.8. Phylogenetic analysis of full-length CLCuD-betasatellite sequences

Phylogenetic analysis (ML) of betasatellite sequences determined in this study, with representative GenBank reference sequences, indicated that 140 isolates grouped with BYVMB, ChLCuB, and CLCuMuB, with robust bootstrap support. In addition, six of the isolates identified here as a new species, clustered within the CLCuMuB sister clade with which they shared <91% pairwise nucleotide identity (Briddon et al., 2017) with previously reported betasatellites (Fig. 7a, spreadsheet S1). Finally, BYVMB sequences showed extensive intra-specific diversity, and grouped within one of 2 sister clades (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7a.

The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed for betasatellite sequences by Maximum likelihood analysis using 1000 bootstrap iterations, for 140 sequences determined in this study (blue color font) and selected reference sequences available in the GenBank database (n=73). CLCuMuB isolates were identified to the species level based on pairwise distance analysis with the SDT v1.2 algorithm. The tree was rooted with the cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGeB) sequence, Accession no. NC006935, endemic to sub-Saharan Africa.

Several CLCuMuB betasatellites (this study) were identified as the following predicted recombinants, CLCuMuB-Multan (CLCuMuB-Mul), CLCuMuB-Burewala (CLCuMuB-Bu), CLCuMuB-Shahdadpur (CLCuMuB-Sha) and CLCuMuB-Vehari (CLCuMuB-Veh), associated with the CLCuD landscape (Akhtar et al., 2014; Amin et al., 2006; Zubair et al., 2017). Because the working cut-off for betasatellite ‘strain’ demarcation has not been established by the previous or presently revised classification (Briddon et al., 2008, 2017; Fiallo-Olivé & Navas-Castillo, 2020), herein, the term “recombinant” has been applied, instead of ‘strain’.

Based on results of phylogenetic and recombination analyses of CLCuMuB sequences, recombinants grouped in one of several distinct clades. In this study, the CLCuMuB-Bur predicted recombinant found to be highly prevalent, was also associated with CLCuD-begomoviruses during the Burewala epidemic (Amin et al., 2006). The additional isolates contributed by this study has revealed more extensive divergence among the previously reported references CLCuMuB-Bur sequences, splitting the latter into several subclades (Akhtar et al., 2014; Amin et al., 2006; Zubair et al., 2017). A number of divergent betasatellite recombinant sequences determined in this study grouped in previously un-resolved sister clades, indicating they are newly discovered and potentially emergent CLCuMuB-Bu recombinants (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7b.

The cotton leaf Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) tree was reconstructed by Maximum likelihood analysis using 1000 bootstrap iterations for 80 sequences of isolates determined in this study (blue-colored font) and selected GenBank reference sequences (n=46). The CLCuMuB isolates were identified to the species level based on pairwise distance analysis with the SDT v1.2 algorithm. The tree was rooted with the cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGeB) sequence, Accession no. NC006935, endemic to sub-Saharan Africa.

3.9. Identification of helper begomovirus and betasatellite species/strains

Based on the shared pairwise nucleotide identity estimates, the working cut-off for betasatellite ‘species’ delineation has been revised from 78% (Briddon et al., 2008) to 91% (Briddon et al., 2017), resulting in 61 proposed species classified within the genus, Betasatellite, and additional modifications have been proposed (Fiallo-Olivé & Navas-Castillo, 2020). Consequently, the nomenclature used for most betasatellite GenBank Accessions is still based on the initially-established species cut-off. In this study, the resultant taxa and nomenclature for BYVMB, ChLCuB, and CLCuMuB sequences determined here and GenBank references, has been based on pairwise distance analysis (SDT algorithm) to guide species demarcation. These revised ‘type species’ accessions (Briddon et al., 2017) were then used as reference sequences (datasheets S1-S3). Based on this analysis 6 isolates determined in this study were found to share 86.6%-90% pairwise nucleotide identity with CLCuMuB previously described isolates from Pakistan (LT827054, KR013746). Collectively, the sequences represent three previously undescribed betasatellite species (Table 6). All 6 isolates encode a characteristic βC1 ORF, A-rich region, and SCR. These previously unrecognized betasatellite species were associated with symptomatic commercial cotton fields in Lodhran, and Luffa cylindrica plants from the sentinel plots in Lahore. The latter associated helper begomovirus sequences have been submitted to GenBank (Table S1, S2).

Table 6.

Proposed species and name for previously unreported betasatellite identified in this study.

| Sample No. |

Sample name, host, location, and year | Closest match and percent nucleotide identity (SDT) | Proposed species and name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CV25b12401p_LuYMB_Luffa _Lahore_2011 |

88.7% with CLCuMuB (LT827054) | Luffa yellow mosaic betasatellite |

| 2a | 104_CLCuLoB _Cotton_Lodhran_2012 | 89.9% with CLCuMuB (LT827054) | Cotton leaf curl Lodhran betasatellite |

| 2b | CVb3104_CLCuLoB _Cotton_Lodhran_2011 | 89.9% with CLCuMuB (LT827054) | Cotton leaf curl Lodhran betasatellite |

| 2c | 108_CLCuLoB _Hollyhock_Islamabad_2012 | 89.9% with CLCuMuB (LT827054) | Cotton leaf curl Lodhran betasatellite |

| 2d | CLCuV_108_CLCuLoB _Hollyhock_Islamabad_2012 | 90% with CLCuMuB (LT827054) | Cotton leaf curl Lodhran betasatellite |

| 3 | CV28b16205p_CuMB _Cucumber_Lahore_2011 | 86.6% with CLCuMuB KR013746 | Cucumber mosaic betasatellite |

The full-length begomovirus (n=1500) and betasatellite genomes (n=1200), with the respective plant hosts and year have been collated and archived into the J.K. Brown laboratory databases. The SDT analysis delineated eight additional betasatellite species, 2 additional begomovirus species and 10 additional begomovirus strains (datasheets S1-S4). The GenBank Accession number assigned to each begomoviral and betasatellite sequence determined here and/or of available GenBank sequences have been archived in the Brown laboratory database. Results of the analyses of the curated database sequences supports the revision of species or strain boundaries and revised nomenclature proposed in this report (Table S3 and Datasheets S1-S4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Geminivirus distribution in sentinel plots and commercial fields

Sentinel plants have proven useful for monitoring new and emergent plant pathogens, can inform the status of new or impending outbreak pathogens, and for calibrating forecasting systems (Hobbs et al., 2010; Sikora et al., 2014). The goal of this study was to conduct large-scale, long-term surveillance of cotton-infecting begomoviruses in two major cotton-growing provinces of Pakistan, to assess the distribution of known CLCuD complexes, and achieve early detection of potentially high-risk emergent or re-emergent species. This surveillance approach involved the combined sampling of commercial cotton fields and sentinel plots in 15 cotton-growing districts, including Multan and Vehari (Burewala), which were the epicenters of the cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD) epidemics in Pakistan and India during 1989-1999 and 2002-2015 (Sattar et al., 2017). Previously known and newly discovered begomoviruses and betasatellite strains and/or species were identified in commercial cotton fields and sentinel plots planted to four differentially susceptible cotton varieties and vegetable crop species. Wild, uncultivated weed species established and/or naturally-occurring in the sentinel plots also harbored previously known and newly discovered isolates. These results corroborate a multitude of studies carried out in Pakistan that have shown the importance of wild species as reservoirs of ‘non-core CLCuD’ begomoviral species, some that also infect cotton.

The CLCuKoV-Bu strain was the predominant begomovirus identified in cotton agroecosystems in both the Punjab and Sindh Provinces based on surveillance from 2010 to 2014 (Sattar et al., 2017). This may not be surprising, given its prior association with the second CLCuD epidemic that began near the township of Burewala (Amrao, Amin, et al., 2010), now recognized as the epicenter of the ‘Burewala epidemic’ that prevailed from 2001-2014 (Sattar et al., 2013). The CLCuKoV-Bu has been recognized as a resistance-breaking phenotype, most likely due to selection following release of resistant varieties developed to combat CLCuMuV, and which spread rapidly and prevailed throughout cotton-growing regions of Pakistan (Sattar et al., 2017) and India (Rajagopalan et al., 2012) until 2014-2015.

Population genetics analysis for the predominant begomovirus genome sequences determined here, has revealed that CLCuKoV-Bu has continued to expand. During this four-year same timeframe and apparently onward, the recombinant CLCuMuV-Ra (Table 5) recognized in 2008, as a minor component of the CLCuD complex (Kumar et al., 2010), has emerged to become a predominant strain. Notably, since the release of leaf curl-resistant cotton in the mid-1990s, CLCuMuV and the core CLCuD complex consisting of CLCuAlV, CLCKoV-Ko and CLCuMuV-Fai, which were discovered during the Multan epidemic, have rarely been detected in cotton fields in Pakistan since then (Zubair et al., 2017).

In this study, CLCuMuV and several ‘non-core’ CLCuD-associated begomoviruses were identified in the ‘differential’ sentinel plots established in Lahore, Multan, Vehari (Punjab) and Sakrand (Sindh). The MNH886 MNH814, MNH786 and CIM496 cotton differentials were selected with prior knowledge of their differential susceptibilities to CLCuMuV and CLCuKoV-Bu ‘core’ CLCuD complex. The use of differentially-susceptible cotton genotypes in this study has demonstrated that they were useful indicator hosts for the epidemic-associated ‘core’ begomoviruses, making them useful for annual surveillance to identify the predominant members of the CLCuD complex in the Punjab and Sindh Provinces.

4.2. Emergence of a new cotton leaf curl Multan virus-Ra strain

Tajima's D analysis revealed that the now-emergent CLCuMuV-Ra, identified as a minor component of the leaf curl complex in Pakistan and India as early as 2014, is undergoing genetic expansion, while geographic expansion is also observed in this study and previous studies (Zubair et al., 2017; Islam et al., 2018; Biswas et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2021). In a study (Zubair et al., 2017) CLCuMuV variants, including a previously identified Rajasthan strain of the ‘Multan virus’ and core begomoviruses known since the CLCuD ‘Multan epidemic, were identified in cultivated cotton fields. Thus, between the first and second epidemics, the causal CLCuD species and strains were thought to be displaced, unknowingly prevailed in the environment until now. Interestingly, in a more recent study (Ahmed et al., 2021) a new strain of Multan species, CLCuMuV-Ra, has been identified from cotton in the Punjab Province. Similarly, a survey of begomoviruses associated with whiteflies in cotton fields in the Punjab and Sindh Provinces (Islam et al., 2018) has revealed that the whitefly vector already harbored the ‘new’ CLCuMuV-Ra isolate. Equally striking, has been the emergence and spread of CLCuMuV-Ra in northwest India from 2012-2020 (Biswas et al., 2020; Datta et al., 2017), at about the same time this once rare strain was more frequently detected in Pakistan cotton during 2010-2017 (this report). Accordingly, the number of GenBank accessions corresponding to the new CLCuMuV-Ra strain, increased from 105 to 156 between January 2015 to September 2021. Overall, results indicate that CLCuMuV-Ra has become the predominant core CLCuD species/strain and has displaced CLCuKo-Bur as the predominant CLCuD-begomovirus in both India and Pakistan.

The periodic shift in CLCuD dynamics appears to be primarily attributable to unrealized differences in susceptibility among the cotton varieties released to combat resistance to extant viruses and strains circulating in the environment, resulting in great vulnerability to the selection of CLCuD variants through exposure to the newly-released varieties. The cultivated cotton varieties that predominated during the surveillance period (this report), were selected based on CLCuKoV-Bu tolerance/resistance. Despite the release continuous release of tolerant/resistant varieties by breeding programs, the genetic diversity is overall extremely narrow, and at the same time, the varieties planted in nearly all cotton production areas consist of the same few varieties. Thus, cultivation of narrow genetic diversity throughout the cotton belt in the Punjab Province has led to widespread crop failure in years when whitefly populations are high, due to selection of new virus resistance-breaking variants and their rapid spreading across vast acreages in months to several years. As cotton varieties begin to fail, the tendency has been to increase the frequency of insecticide application. Further, when insecticide use is not rotated effectively, resistance to compounds can develop rapidly among the different whitefly vector haplotypes. Shifts in the predominant whitefly haplotype vector(s) of begomoviruses in cotton-vegetable systems in Pakistan can lead to the accelerated spread of certain begomovirus variants over others (Paredes-Montero et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2020).

In this study, CLCuMuV-Ra isolates extant in Sakrand (Sindh) shared 96.8% to 97.9% pairwise nucleotide identity with certain begomoviral GenBank accessions that had been associated with whiteflies collected in 2013 from an unknown location in Pakistan (GenBank Accessions MH555070, MH555071, MH555072, MH560503). These isolates shared 94.0%-94.7% pairwise nucleotide identity with other CLCuMuV-Ra genome sequences identified in the Punjab Province, later reported by Zubair et al. in 2017 (Zubair et al., 2017), Islam et al. in 2018 (Islam et al., 2018) and Ahmed et al. in 2021 (Ahmed et al., 2021), all sharing 98%-100% nucleotide identity (datasheet S4). The CLCuMuV-Ra isolates from Punjab (this study), shared the highest nucleotide identify with CLCuMuV-Ra isolates reported in 2021 by Ahmed et al. from Punjab Province. These observations support the hypothesis that the ‘original Multan epidemic’ (first) ‘core’ begomoviral species persist in the environment, even at low frequencies, where they continue to diversify and recombine in response to cotton genotype/germplasm, characteristically, one step behind the next begomovirus resistance-breaking variant. Finally, a somewhat distinct variant of the CLCuMuV-Ra strain that has become the predominant variant in Sindh Province, appear to be evolving independently from the now widespread CLCuMuV-Ra. This observation is supported by the substantial number of CLCuMuV sequences determined here, and was not foreshadowed by CLCuMuV-Ra sequences, of which only a few have been deposited in the GenBank database.

In this study, the CLCuD-viruses that predominated during the Multan epidemic, namely, CLCuMuV-Fai, CLCuKoV-Ko, and CLCuAlV, were not identified in commercial cotton field samples largely, however, CLCuMuV and CLCuAlV were detected in symptomatic cotton differentials in sentinel plots. This indicates that viruses previously responsible for widespread outbreaks are persistent in susceptible plant species, most likely also including vegetables, tropical fruit trees, and uncultivated hosts. The genetic background of cotton genotypes sampled in commercial fields are largely unknown. Without this information, it is not possible to identify or predict which varieties or germplasm source(s) may be susceptible to newly diversifying CLCuD species and strains. Incorporating such knowledge into breeding programs could guide germplasm choices for commercial planting including new or existing varieties with resistance to known species or strains. Knowledge of the different genetic backgrounds of cotton varieties planted in the different cotton-growing locations, would complement surveillance activities that identify the predominant geminiviruses circulating in sentinel plot cotton differentials and commercial cotton fields. A coordinated effort to translate surveillance data to guide the selection of virus-specific tolerant/resistant cotton varieties in each subsequent year would be a step in the right direction toward curbing outbreaks caused by already known species and strains of CLCuD (Ahmed et al., 2021; Zubair et al., 2017).

4.3. The prevalence of recombinants and other leaf curl variants

Previous examples of recombination among CLCuD-associated begomovirus-betasatellite complexes have pointed to the propensity among geminiviruses to undergo recombination, potentially involving all coding and intergenic regions (Qadir et al., 2019). Frequent recombination among CLCuMuV and CLCuMuB variants at different breakpoints has been observed often (Farooq et al., 2021; Zubair et al., 2017). In this study, recombination was predicted to contribute importantly to the evolution of diverse viruses and strains by recombination. Most recombination events occurred in replication-associated protein (Rep) and coat protein (CP) encoding regions of CLCuAlV, CLCuMuV and CLCuKoV-Bu (Fig. 3). Recombination events were predicted in new CLCuMuV variants that possessed segments of cp and rep of CLCuKoV-Bu (different isolates). Results indicated that CLCuKoV-Bu was the predominant ‘core’ CLCuD-associated virus, previously recognized as the resistance-breaking, recombinant involving CLCuMuV and CLCuKo-Ko (Amrao et al., 2010; Sattar et al., 2017), which is consistent with a recent report (Ahmed et al., 2021). However, the recombination events predicted here are distinct from those associated with the recombinants that involved the cp or rep, respectively (Zubair et al., 2017). A single CLCuKoV-Ko-like (OL436149) recombinant was identified in this study, whereas two CLCuAlV recombinants were identified with the break points located in the viral cp, making them unique from CLCuAlV variants associated with the initial ‘core’ CLCuD complex species in the first or “Multan’ epidemic.

Finally, an insertion (mutation) was identified in the C2 ORF of a CLCuKoV-Ko isolate sequenced here that results in ‘early’ stop codon in the ORF. This mutation is reminiscent of that identified in the truncated C2 ORF of the resistance-breaking CLCuKoV-Bu strain (Amrao, Amin, et al., 2010). Evolution of the latter truncated CLCuKoV-Bu C2 ORF is posited to have facilitated resistance-breaking in cotton varieties released to combat the CLCuMuV pandemic, which led to the emergence of CLCuKoV-Bu, causal virus of the second CLCuD outbreak in Pakistan (Amrao, Amin, et al., 2010).

Among plant viruses, geminiviruses, in particular, are known have relatively high rates of mutation (Duffy & Holmes, 2009) and to diversify by recombination with co-infecting viruses and their strains (Martin et al., 2021; Syller, 2012). The extensive genomic variability evident among the begomovirus-betasatellite isolates studied here, is consistent with the anticipated ongoing diversification of this group of plants viruses within their South Asian center of diversification. Based on the observations presented here, the establishment of a country-wide surveillance program to regularly track the dynamic diversification of the CLCuD-geminivirus-betasatellite complexes in commercial cotton and wild reservoirs, and in strategically located sentinel plots, can provide valuable insights into the dynamics of CLCuD in Pakistan cotton-vegetable cropping systems, and inform the strategic selection of specific cotton varieties that are made available to farmers each year. The annual establishment of sentinel plots for CLCuD surveillance would facilitate early-recognition of new or re-emergent virus variants with a potential for resistance- breaking, increased virulence, and/or host range shifts. Similarly informative, parallel tracking of the predominant whitefly vector haplotypes, which occupy different environmental niches (Paredes-Montero et al., 2019; Paredes-Montero et al., 2020, Paredes-Montero et al., 2021; Paredes-Montero et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2020), can vary in begomovirus-transmission competencies (Pan et al., 2018, Pan et al., 2020, Shahid et al., 2023) and differ in the propensity for developing insecticide resistance, would go far to inform knowledge-driven CLCuD management practices that result in reduced damage to the cotton crop in Pakistan.

4.4. Geminivirus diversity and host range in cotton-vegetable cropping systems

Until the ‘Multan’ epidemic occurred, the etiological agent of CLCuD, now known to consist of a complex of geminiviruses, primarily begomovirus-betasatellite-alphasatellite complexes, was unidentified (Briddon et al., 2001). During the CLCuKoV-Bu epidemic, several non-core CLCuD-associated viruses previously reported solely from vegetable crops, were detected in cotton, and included CpCDV (Manzoor et al., 2014), ToLCNDV tomato leaf curl Gujarat virus (Zaidi et al., 2015), and OELCV (Hameed et al., 2014) (Table S3), providing evidence of host-shifting and of their persistence in the environment. In addition, cotton was identified as the host of exotic, New World bipartite SLCV in commercial cotton fields (Table 3,4). Although SLCV is endemic to the Americas (Brown & Nelson, 1986, 1989), it has been reported from vegetable crops in the Middle East during 2003-2012, owing to its presumed introduction on ornamental plants (Lapidot et al., 2014). Also, the bipartite abutilon mosaic virus (AbMV) that originated in the West Indies and was detected in cotton in Pakistan for the first time, which is distinct from the AbMV isolate identified in India from an Abutilon sp. (Jyothsna et al., 2013). The discovery of SLCV and AbMV in cotton was unexpected because neither has been reported to infect cotton in North America and the Caribbean Islands where they are endemic, respectively, even though cotton is widely cultivated in both locales (Jyothsna et al., 2013; Lapidot et al., 2014). Finally, also unexpectedly, four previously known begomoviruses, HoLCV, OELCuV, PaLCV, and PeLCV, were identified in cotton for the first time.

The CLCuMuV and CLCuKoV host range was discovered to be much broader than previously known, herein leading to the first detection report of CLCuKoV-Bur in cucumber, Luffa cylindrica, and okra. In addition, previous studies have reported CLCuKoV-Bu capable of infecting Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, L. cylindrica, papaya, Solanum melongena, Ricinus communis, and Xanthium strumarium (Fareed et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2010; Mubin et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 1998; Zia-Ur-Rehman et al., 2013). These collective observations reveal that the CLCuKoV-Bur host range spans at least several plant families. Also, here, CLCuMuV was detected in Sida micrantha, hibiscus, okra, papaya, and tomato plants, all viruses previously reported as hosts (Shahid et al., 2007; Sinha et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 1998). These results further support the potential for host range expansion among CLCuD viruses, especially those associated with host reservoirs that bridge the gap between cropping cycles from which new outbreaks could be initiated.

4.5. Shift in the predominant CLCuD begomovirus-betasatellite complex in Pakistan

Many begomoviruses and strains thereof, are known to cause CLCuD, however, until this report, all recognized helper begomoviruses have been accompanied by the same betasatellite, CLCuMuB. Since the Multan epidemic, a unique recombinant of CLCuMuB, named CLCuMuB-Bu, has prevailed. It is a predicted recombinant that harbors the satellite-conserved region (SCR), apparently derived from the tomato leaf curl betasatellite (ToLCB) (Amin et al., 2006). However, in this study, cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite-Shahdadpur (CLCuMuB-Sha), a distinct CLCuMuB variant that until now, was previously reported exclusively in the Sindh Province (Akhtar et al., 2014). A sequence comparison of the latter betasatellites, revealed that the newly-emergent CLCuMuB-Sha harbors a fragment of the ToLCB SCR that is 24 bases shorter in length than found in CLCuMuB-Bu (Amrao, Akhter, et al., 2010). Among the betasatellites analyzed in this study, CLCuMuB isolates exhibited the highest rate of evolution (Fig. 4, 7b). This is most likely attributable to its widespread prevalence in cotton and non-cotton host plants throughout Pakistan, and an inherent high frequency of recombination. Phylogenetic and recombination analysis of betasatellites also revealed several prevalent divergent betasatellites (Fig. 4, 7a). Among the 79 CLCuMuB isolates sequenced in this study, 37 were nearly identical to the prototype CLCuMuB betasatellite from the Multan epidemic, indicating its persistence in cotton. However, the phylogeny of the remaining predicted CLCuMuB recombinants, revealed that they formed several sister groups (Fig. 7b). Further, the unexpected prevalence of the previously undiscovered betasatellite, BYVMB, in cotton, points to a major evolutionary step in diversification of CLCuD-associated betasatellites, previously dominated by CLCuMuB. The extant prevalence of genetically-divergent and recombinant isolates of BYVMB and of previously undiscovered CLCuMuB and ChLCuB variants, portend yet another potentially major shift associated with recent selection events among the members of this disease complex. In addition, 33 recombinant isolates of CLCuMuB were identified in this study and found to contain a ToLCRaB-like SCR region (∼235 bases) (7 RDP methods; significant P-value of >0.05 for each) with a hairpin sequence and structure reminiscent of wild type ToLCRaB. Alignment of the latter sequences with another predicted recombinant, also containing a fragment of the SCR region (Amin et al., 2006; Amrao, Akhter, et al., 2010; Zubair et al., 2017) suggests that the ToLCRaB and recombinant CLCuMuB isolates (herein) share a common evolution history. The results reported here therefore provide robust evidence for a surprising shift in the predominant CLCuD-associated betasatellite species in Pakistan and India during 2010-2017, the newly emergent CLCuMuB recombinant that has apparently displaced CLCuMB, which has prevailed since 1990, until its recent apparent displacement.

Fig. 4.

Predicted recombination involving cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) (Event 1) and bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite (BYVMB) (Event 2). For each event, the number of isolates harboring predicted recombinants is indicated parenthetically. For reference, the characteristic genome organization of a betasatellite is shown at the top of the figure.

4.6. The benefits of ongoing surveillance for to inform leaf curl disease management

A surveillance strategy that exploits the benefits of sentinel plot-commercial field monitoring can clearly provide valuable information for facilitating the selection of cotton varieties with tolerance or resistance to prevailing CLCuD viruses. Breeding programs are consistently late releasing/providing resilient cotton planting material, a dilemma that could be remedied by regular surveillance to determine the predominant CLCuD helper and betasatellite species and strains. A recent breeding strategy has incorporated MAC7 from the USDA cotton germplasm collection into breeding programs in response to the CLCuKoV-Bu epidemic (Aslam et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2017; Zaidi et al., 2020). Knowledge of the susceptibility or breadth of resistance in the breeding lines that incorporate this valuable resistance, is imperative, to manage strategic deployment of the resulting varieties, and avoid sole reliance on them for long-term resistance.

Sentinel plot surveillance of susceptible and resistant cotton germplasm, of malvaceous and other vegetable crop species, and potential wild host reservoirs of CLCuD-core complex, has demonstrated the persistence of previously known geminivirus-betasatellite variants, while also underscoring the occurrence of minor helper virus-satellite combinations that contribute to genomic and biological variability and therefore, feasibly, to diversification. A comprehensive surveillance approach that incorporates routine sampling of sentinel plots and commercial cotton to track CLCuD-virus and whitefly vector prevalence and distribution would contribute valuably to effective CLCuD management. Integrating surveillance observations into regional and national cotton breeding program logistics, and into annual recommendations of commercial cotton varieties for farmers would go far to abate CLCuD-episodic outbreaks, while also combatting the emergence of new CLCuD-begomovirus-betasatellite variants that pose an ongoing challenge to cotton production in Pakistan and India.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Pakistan-U.S. Cotton Productivity Enhancement Program-ICARDA, funded by United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Agreement No. 58-6402-0-178F to MSH, and USDA-ARS Special Cooperative Agreement Nos. 58-6402-0-544 and 58-6402-2-763 to JKB for funding to support this research. The authors acknowledge the support of Cotton Incorporated Project #06-829 to JKB for providing continuous support for this research.

Author Contributions

This research was conceptualized by JKB, MZ and MSH. MZ, UH, MJI, MTM and MSH organized experimental fields in Pakistan and collect samples. NC carried out helper component annotation and molecular and bioinformatics analyses, and primer design. HWH oversaw and carried out high throughput sequencing data analysis of helper components and betasatellites. MJI and MI analyzed the data and MJI and JKB wrote original manuscript draft. All authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript. JKB and SH co-supervised and co-coordinated the project. All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript contents.

Data Statement

Sequences determined in the study are available in the GenBank NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the technical contributions of Ms. Sofia Avelar and Dr. Noma Chingandu for annotation and analyses of the begomoviral-betasatellite sequences used for aspects of the study, and for the design of some of the primers used in this study (also, see Reference Brown et al. 2017). The authors wish to acknowledge the provincial and federal administrated cotton research stations in Vehari, Multan, Sakrand, and members of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Punjab Lahore for technical assistance to establish and maintain the sentinel plots and facilitated sample collections in commercial cotton fields located at study sites.

Footnotes

Table S1: A list of plant samples, geographical locations, collection year, geminiviruses and betasatellites isolates identification and accession numbers; Table S2: List of betasatellites (in addition to Table S2) isolated from the samples during study with Partial or un-amplified helpers.; Table S3: Host range of begomoviruses/strains in Pakistan, collected from GenBank, literature and this study. Nomenclature for given begomovirus species is verified/corrected by pairwise nucleotide homology analysis and suggestion regarding update in existing demarcations and nomenclature Datasheet S1: Percentage pairwise nucleotide identity data of cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite determined by SDT v1.2 using available accessions in GenBank and isolates of this study, also suggestions regarding update in nomenclature and species demarcation. Datasheet S2: Percentage pairwise nucleotide identity data of bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite determined by SDT v1.2 using available accessions in GenBank and isolates of this study, also suggestions regarding update in nomenclature and species demarcation. Datasheet S3: Percentage pairwise nucleotide identity data of chili leaf curl betasatellite determined by SDT v1.2 using available accessions in GenBank and isolates herein and proposed updated nomenclature and species demarcation. Datasheet S4: Percentage pairwise nucleotide identity data of Begomovirus isolates of Pakistan determined by SDT v1.2 using available accessions in GenBank and representative isolates of this study, also suggestions regarding update in nomenclature and species demarcation. Figure S1: pictures of various symptomatic plants collected during this study.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2023.199144.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Sequences determined in the study are available in the GenBank NCBI database.

References

- Ahmed N., Amin I., Zaidi S.S.-A., Rahman S.U., Farooq M., Fauquet C.M., Mansoor S. Circular DNA enrichment sequencing reveals the viral/satellites genetic diversity associated with the third epidemic of cotton leaf curl disease. Biology Methods and Protocols. 2021;6(1):bpab005. doi: 10.1093/biomethods/bpab005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S., Tahir M.N., Baloch G.R., Javaid S., Khan A.Q., Amin I., Briddon R.W., Mansoor S. Regional Changes in the Sequence of Cotton Leaf Curl Multan Betasatellite. Viruses. 2014;6(5):5. doi: 10.3390/v6052186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin I., Mansoor S., Amrao L., Hussain M., Irum S., Zafar Y., Bull S.E., Briddon R.W. Mobilisation into cotton and spread of a recombinant cotton leaf curl disease satellite. Archives of Virology. 2006;151(10):2055–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrao L., Akhter S., Tahir M.N., Amin I., Briddon R.W., Mansoor S. Cotton leaf curl disease in Sindh province of Pakistan is associated with recombinant begomovirus components. Virus Research. 2010;153(1):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrao L., Amin I., Shahid M.S., Briddon R.W., Mansoor S. Cotton leaf curl disease in resistant cotton is associated with a single begomovirus that lacks an intact transcriptional activator protein. Virus Research. 2010;152(1):153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M.Q., Naqvi R.Z., Zaidi S.S.-A., Asif M., Akhter K.P., Scheffler B.E., Scheffler J.A., Liu S.-S., Amin I., Mansoor S. Analysis of a tetraploid cotton line Mac7 transcriptome reveals mechanisms underlying resistance against the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Gene. 2022;820 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., Pyshkin A.V., Sirotkin A.V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G., Alekseyev M.A., Pevzner P.A. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas K.K., Bhattacharyya U.K., Palchoudhury S., Balram N., Kumar A., Arora R., Sain S.K., Kumar P., Khetarpal R.K., Sanyal A., Mandal P.K. Dominance of recombinant cotton leaf curl Multan-Rajasthan virus associated with cotton leaf curl disease outbreak in northwest India. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]