Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease starts in neural stem cells (NSCs) in the niches of adult neurogenesis. All primary factors responsible for pathological tau hyperphosphorylation are inherent to adult neurogenesis and migration. However, when amyloid pathology is present, it strongly amplifies tau pathogenesis. Indeed, the progressive accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β deposits in the brain triggers a state of chronic inflammation by microglia. Microglial activation has a significant pro-neurogenic effect that fosters the process of adult neurogenesis and supports neuronal migration. Unfortunately, this “reactive” pro-neurogenic activity ultimately perturbs homeostatic equilibrium in the niches of adult neurogenesis by amplifying tau pathogenesis in AD. This scenario involves NSCs in the subgranular zone of the hippocampal dentate gyrus in late-onset AD (LOAD) and NSCs in the ventricular-subventricular zone along the lateral ventricles in early-onset AD (EOAD), including familial AD (FAD). Neuroblasts carrying the initial seed of tau pathology travel throughout the brain via neuronal migration driven by complex signals and convey the disease from the niches of adult neurogenesis to near (LOAD) or distant (EOAD) brain regions. In these locations, or in close proximity, a focus of degeneration begins to develop. Then, tau pathology spreads from the initial foci to large neuronal networks along neural connections through neuron-to-neuron transmission.

Keywords: Amyloid, microglia, neurofibrillary tangles, neurogenesis, tauopathies

INTRODUCTION

The amyloid hypothesis

The prevailing view in the field is that amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) exhibits a “toxic gain-of-function” when it forms oligomers and aggregates into plaques, directly contributing to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 2]. In particular, the amyloid hypothesis, the prevalent theory of AD pathogenesis, suggests that the accumulation of pathological forms of Aβ is the primary pathological process driven by an imbalance between Aβ production and Aβ clearance [3, 4]. In this pathway, microtubule-associated protein tau pathology with the formation of phospho-tau-immunoreactive neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and subsequent neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration, perhaps mediated via inflammation, are thought to be the downstream result [4]. The direct influence of Aβ on tau pathogenesis is well documented. For example, injection of Aβ fibrils [5] or Aβ-containing brain extract [6] into mutant tau transgenic mice, crossed between mutant tau and amyloid precursor protein (APP) or 5x familial AD (FAD) transgenic mice, results in exacerbated tau pathology [5–16]. Moreover, “in vitro” [17] and “in vivo” [16] studies have demonstrated that Aβ exerts its detrimental actions by activating a key kinase, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) [17, 18], implicating this kinase as an important player in the amyloid cascade. Notably, GSK-3β is the primary kinase that phosphorylates tau [18, 19]. In agreement, increased GSK-3β activity has been observed in the brains of AD patients [20]. These data confirm GSK-3β as a cornerstone of AD pathogenesis and support the notion that this kinase represents a crucial molecular link between Aβ and tau [18, 19, 21–24]. Accordingly, human Aβ oligomers induce hyperphosphorylation of tau at AD-relevant epitopes and cause neuritic dystrophy in cultured neurons [25].

The current view

In the current theory, I propose a shift in the paradigm wherein aggregates of the two key players in AD pathogenesis, i.e., Aβ and tau peptide, develop by two different and relatively independent processes. In particular, the central hypothesis is that tau pathogenesis is linked to adult neurogenesis and migration. All elements predisposing to pathological tau hyperphosphorylation are present in the niches of adult neurogenesis. In contrast, as already documented in the literature, metabolism plays a primary role in driving Aβ deposition [26–28]. Despite the fact that the two processes driving Aβ and tau pathogenesis are relatively independent, when Aβ pathology is present, it acts as a strong driving force for tau pathogenesis. Therefore, Aβ pathology also plays a crucial role in AD pathogenesis in the current theory. However, its detrimental effect is explained in quite a different way from the classical amyloid hypothesis. In particular, Aβ not only has a downstream effect on tau pathogenesis, especially when Aβ and tau colocalize, but also has an early indirect effect by influencing the process of adult neurogenesis and migration. In brief, the current theory depicts the following scenario. Progressive accumulation of extracellular Aβ deposits in the brain triggers a state of chronic inflammation by microglia. Microglial activation has a significant pro-neurogenic effect that fosters adult neurogenesis and supports neuronal migration. Unfortunately, this “reactive” pro-neurogenic pathway ultimately perturbs the delicate homeostatic equilibrium in the neurogenic niches by amplifying tau pathogenesis in AD. An imbalance between increased tau phosphorylation, already occurring at a high rate in neural stem cells (NSCs), coupled with less efficient clearance of the byproducts of tau hyperphosphorylation, as well as further increases in hyperphosphorylation during long migrations, could be the primary reasons behind these detrimental effects. This scenario involves NSCs in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) in late-onset AD (LOAD) and NSCs in the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ) along the lateral ventricles in early-onset AD (EOAD), including familial AD (FAD). Neuroblasts carrying the initial seed of tau pathology travel throughout the brain by neuronal migration driven by complex signals, bringing the disease from the niches of adult neurogenesis to near (LOAD) or distant (EOAD) brain regions. At these locations, or in close proximity, a focus of degeneration begins to develop. Then, tau pathology spreads from the initial foci to large neuronal networks along neural connections by neuron-to-neuron transmission.

Therefore, the new core statement of the current theory is that AD starts in NSCs in the niches of adult neurogenesis. Interestingly, recent findings suggest that the current paradigm and the classic amyloid hypothesis might not be incompatible. In particular, some authors found clear evidence of intracellular oligomers of Aβ generated in NSCs within the SGZ niche at a very early stage in a transgenic AD mouse model [29]. In the current theory, this finding could be interpreted as proof that Aβ pathology not only indirectly influences tau pathogenesis by fostering neurogenesis and migration but also directly contributes to pathological tau hyperphosphorylation within these niches, most likely by activating GSK-3β. This view also reinforces the role of amyloid pathology as a leading factor in the current model, bridging the gap between the two theories.

In the first section of this manuscript, I propose the core hypothesis of tau pathogenesis in AD as linked to adult neurogenesis and migration. In the second section, I present the indirect microglia-mediated Aβ-tau interaction. In the third section, I consider the scaling of molecular pathology to the macroscopic brain. In the Discussion section, I put the new theory into context and consider the potential merits and limitations of the current proposal.

TAU PATHOGENESIS IS LINKED TO ADULT NEUROGENESIS AND MIGRATION

Tau isoform and phosphorylation during postnatal and adult neurogenesis

The tau isoform featured by the presence of three-repeat microtubule-binding domains (3R-tau) predominates at early developmental stages [30, 31]. The 3R-tau isoform exhibits a lower affinity for microtubules than the mature brain tau isoform [32], so it confers lower stability to the cytoskeleton and allows the morphological differentiation and migration of developing neurons. In contrast, 4R-tau is the predominant isoform at mature developmental stages [30, 31]. It binds microtubules with a greater affinity and displaces the previously bound 3R-tau from microtubules [30], guaranteeing the stability of the cytoskeleton required to maintain neuronal integrity. In addition to the presence or absence of exon 10 shaping the 4R- or 3R-tau isoform, tau phosphorylation is developmentally regulated: it is higher in fetal neurons and decreases with age during development [33–35]. As phosphorylation decreases the affinity of tau protein for microtubules [36], hyperphosphorylation of fetal tau [33, 37] contributes to maintaining a dynamic microtubule network as required by the outgrowth of axons during embryogenic neurogenesis [38].

In the adult human brain, both 3R- and 4R-tau are present, although in newborn neurons in the niches of adult neurogenesis, 3R-tau is the primary isoform [32, 39]. In particular, it has been demonstrated that 3R-tau is transiently expressed during the maturation of NSCs in the hippocampal SGZ [32, 38, 40, 41]. For instance, in rodents, individual new subgranular neurons exhibit the highest expression of 3R-tau when cells are 2 weeks old [40], and expression of this molecule is maintained until 4 weeks, a time point at which 3R-tau is replaced by 4R-tau [32]. Moreover, high tau phosphorylation in fetal epitopes is related to adult neurogenesis in both the V-SVZ and SGZ [39, 42], although fetal tau phosphorylation can be found in the adult brain in additional areas [35]. Transient expression of the 3R-tau isoform and fetal tau hyperphosphorylation in adult neurogenesis are not unexpected, considering that new neurons require a high degree of plasticity to migrate, differentiate, project axons, and integrate into the cell layer, and both the 3R-tau isoform and high phosphorylation guarantee a dynamic microtubule network [38, 39]. Furthermore, abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau in AD constitutes paired helical filaments (PHFs) of NFTs [43–47]. Interestingly, the 3R-tau isoform is said to facilitate PHFs, such as those seen in classical AD NFTs [48]. Additionally, several sites of hyperphosphorylation of the fetal 3R-tau during development were the same as those in the AD brain [33, 37, 49, 50]. Additionally, as already reported, GSK-3β is the first identified tau kinase [51, 52] that plays a key role in AD-like tau hyperphosphorylation [18, 19, 21, 53–55]. Interestingly, during development, expression of GSK-3β reaches its highest level in the late embryonic/early postnatal period, markedly decreasing with maturation into adulthood [56, 57]. More importantly, activated GSK-3β is believed to be the primary tau kinase in newborn neurons during adult neurogenesis [39, 58].

In summary, tau isoform and phosphorylation in NSCs during postnatal, as well as adult, neurogenesis seem equivalent to those predisposing to the typical tau alterations observed in AD. In this regard, it is worth noting that the primary cause of the tau functional change and NFT formation in AD is believed to be abnormal hyperphosphorylation [59–67]. In addition, abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation seems to reflect exaggerated physiological phosphorylation rather than disorganized phosphorylation at random sites [68, 69]. Therefore, tau pathogenesis in AD seems to depend exclusively on the extent of phosphorylation and the combination of multiple specific phosphorylation sites [38, 70, 71].

Differences between adult and postnatal neurogenesis associated with tau pathogenesis

Interestingly, although 3R-tau is said to facilitate PHFs, such as those seen in classical AD NFTs [48], and several sites of high phosphorylation of the fetal 3R-tau are the same as those in the AD brain [33, 37, 49, 50], during development, fetal tau remains functional and does not polymerize into NFTs. At this point, I speculate that a further crucial factor responsible for tau pathogenesis in AD could be found among those aspects that distinguish adult and postnatal neurogenesis. In this regard, it is worth noting that although postnatal and adult neurogenesis share some niches and signals, there are some important differences between the two.

The primary difference is that the neurogenic niches are surrounded by different environments. In particular, in the large, evolutionarily developed brain of adult mammals, neuroblasts originating in the neurogenic niches must migrate long distances through a complex and generally inhibitory environment [72] made up of neuronal, glial, and vascular networks to reach their destination [73]. Considering that tau hyperphosphorylation in neuroblasts contributes to maintaining a dynamic microtubule network that is amenable to migration, demanding and long migration through the inhibitory environment of the adult brain could have the detrimental effect of further increasing tau hyperphosphorylation. I believe this factor could be crucial to tau pathogenesis, especially in EOAD. Indeed, in the current theory, EOAD pathogenesis is linked to adult neurogenesis, especially in the V-SVZ. Here, migrating neuroblasts carrying the seeds of tau pathology deviate from the conventional rostral migration stream (RMS) to the olfactory bulb (OB) and take different and long migration paths toward various regions of the cortex, driven by complex signals released, in particular, by activated microglia.

I believe a further difference between adult and postnatal neurogenesis relevant to the current theory is related to clearance activity in the niches. In this respect, rapidly accumulating data suggest that autophagy fulfils some roles in NSC function [74, 75]. Specifically, autophagy may serve both a surveillance role by ensuring the quality of NSCs by degrading and eliminating intracellular components and aggregates and an elimination role by ensuring the removal of defective or damaged NSCs through its cell death promotion abilities [74, 75]. Consequently, reduced autophagy during aging compared to the postnatal period may contribute to the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates in NSCs. This event would be a crucial factor in AD pathogenesis, especially in LOAD. Indeed, in the current theory, LOAD is primarily linked to neurogenesis in the hippocampal SGZ, where neural precursors migrate very briefly to the granular layer of the DG. Accordingly, an increase in tau hyperphosphorylation through migration would be a less relevant factor in LOAD pathogenesis than in EOAD pathogenesis.

In summary, in the niches of adult neurogenesis, all conditions predispose patients to pathological tau hyperphosphorylation and accumulation of tau aggregates. When microglia activated by Aβ deposition foster neurogenesis in the niches and support long migrations, the situation is taken to extremes.

THE MICROGLIA-MEDIATED Aβ-TAU INTERACTION

According to the current theory, the slow progressive accumulation of Aβ deposits in the brain provokes microglial activation. Activated microglia foster the process of neurogenesis in niches and support neuronal migration. This “reactive” increase in neurogenesis and migration amplifies tau pathogenesis in AD, and available data in the literature seem to support this scenario.

Microglial activation in AD

Microglial activation in AD is well documented [76]. In the early AD brain, microglia are found in high densities surrounding Aβ plaques [77]. Both postmortem [78, 79] and “in vivo” clinical studies using PET ligands that bind to activated microglia [80, 81] have consistently confirmed the finding that microglia colocalize with amyloid plaques in AD. In particular, senile plaques are infiltrated by astrocytes and microglia in and around their central amyloid core [82, 83]. From this evidence, it has been proposed that Aβ plaques stimulate a chronic inflammatory reaction [84]. In other words, the activation and increased proliferation of microglia in AD [85] are thought to result from glial reactions to events related to the ongoing deposition of Aβ [86, 87]. In this regard, the high density of microglia found around Aβ plaques is consistent with their role in Aβ clearance pathways and their activation by Aβ itself [88]. Moreover, the finding that microglia possess a range of pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors, receptors for advanced glycation end products, and scavenger receptors, many of which can recognize different Aβ species through various interactions of differing affinities, support their role in Aβ clearance [89–91]. Once activated, microglia and astrocytes produce several proinflammatory signaling molecules, including cytokines, growth factors, complement molecules, cell adhesion molecules, and chemokines [84, 92, 93]. In agreement with these findings, increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [78] as well as upregulated chemokine receptors [94], have been found in the AD brain.

Microglia and adult neurogenesis

At this point, it is relevant to the current theory to disclose that microglia have been found to have a role in adult neurogenesis.

Microglia modulates the production of new neurons

In particular, microglia can modulate the production of new neurons in the adult brain [88]. NSCs have been found to depend on signals from their niche to regulate their self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation [88]. In the absence of microglia, NSCs progressively lose the capacity to undergo the differentiation process required for neurogenesis [95]. The role of microglia in neurogenesis can be seen as instructive, with microglial-secreted factors, such as IGF-1 and trypsinogen, having the capacity to regulate adult NSC proliferation and differentiation, promoting neurogenesis [96, 97]. Interestingly, both acute and chronic microglial activation can modulate neurogenesis [88]. In particular, “in vitro”, microglia acutely activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) strongly expressing IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α have been found to reduce neural progenitor cell survival [98]. The study of some neurological disorders confirmed that overactive microglia might inhibit adult hippocampal neurogenesis [99–101]. For instance, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation can disrupt neurogenic niches and undermine the integrity of neuronal population replenishment programs [102]. Conversely, “in vitro”, microglia chronically activated by LPS with a secretory profile dominated by IL-10 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) are highly permissive to the neurogenic cascade [98]. The finding that microglia chronically activated with a definite secretory profile can support adult neurogenesis is consistent with the current theory in which Aβ plaques stimulate a chronic inflammatory reaction by microglia. In addition, LPS, IL-10 and PGE2 are implicated in AD [103–111].

Microglia has phagocytic activity

Of note, microglia serve a further function in adult neurogenesis. In young adult rats, approximately 9,000 new cells are generated in the SGZ each day, but nearly half do not survive [112, 113], similar to what occurs in the V-SVZ [113]. In particular, the majority of newborn neural progenitors undergo apoptosis 1–4 days after they are generated in the SGZ, and microglia phagocytose apoptotic debris from these cells to help maintain the equilibrium of the neurogenic niche [114]. Interestingly, this microglial phagocytic activity is apparently unchanged by aging or acute neuroinflammation, suggesting that it is a mechanism that promotes a homeostatic neurogenic niche in both healthy and disease states [114].

Microglia directs the migration of neuroblasts

Finally, microglia seem to have the capacity to direct the migration of neuroblasts [115]. Interestingly, some authors found in a transgenic mouse strain that depletion of microglia in the V-SVZ was linked to a marked reduction in neuroblasts reaching the OB with a concomitant accumulation of immature cells in the V-SVZ and RMS [116]. These findings suggest that microglia residing in the V-SVZ/RMS regions are critical for neuroblast survival and migration to the OB, possibly as a consequence of their release of the cytokines IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 [116]. It is also important to note that microglia-mediated phagocytosis of neuroblasts is a rare phenomenon along the V-SVZ/RMS migratory pathway, and accordingly, markers of activated microglia, such as TREM2 and CD68, were undetectable in these regions [116]. In contrast, within the OB layers, where interneurons are continuously replaced by V-SVZ-generated precursors, microglia exhibit overt and robust phagocytosis. Therefore, microglia in the neurogenic areas of the V-SVZ/RMS are unique and specialized to support neural precursor proliferation and migration across significant distances to their final destination [117–119]. Further data supporting the role of microglia in sustaining and driving the migration of neuroblasts come from research on brain injury. In this regard, an invariant feature of damage to the CNS is the migration of microglial cells to the site of injury and their subsequent activation [120, 121]. Interestingly, several studies have shown that precursor cells preferentially migrate to sites of inflammation in animal models of multiple sclerosis and that these new cells preferentially differentiate into oligodendrocytes [122–124]. In contrast, in experimental models of more acute damage with neuronal loss, precursor cells, both extrinsically provided and endogenous precursor cells, migrated to the damaged area and differentiated into neurons [125–130]. More recently, some authors reported that precursor cells migrate from the V-SVZ and RMS to the injured cortex after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in mice and that prokineticin 2 (PROK2), a chemokine important for OB neurogenesis, is expressed exclusively by cortical microglia in the cortex as early as 24 h after injury [131]. In addition, the same authors demonstrated “in vitro” that cells expressing PROK2 directionally attract V-SVZ cells [131].

The role of astrocytes

The role of astrocytes, in addition to that of microglia, is in line with current theory, considering that astrocytes are early involved in AD [132–134] and have strong pro-neurogenic activity [135, 136].

Astrocytes in AD

Ramon y Cajal noticed reactive hypertrophic astrocytes surrounding senile plaques and blood vessels with amyloid deposits in post-mortem AD patients already in 1913 [137]. This observation has been replicated several times in AD patients’ brains [138–141] and in AD mouse models [142–144]. Within the CNS, astrocytes play a key role in the protection and repair of neuronal damage [145, 146]. Astrocytes respond to inflammatory substances and undergo a process known as reactive astrogliosis [147, 148] in various pathological conditions, including acute injury and progressive disorders such as tumors and AD [147]. Reactive astrocytes release molecules such as cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and gliotransmitters [149]. Notably, astrocytes release factors that promote axon growth, which are essential for synaptic formation and maturation in response to an injury [148, 150]. Moreover, astrocytes increase neuronal viability and mitochondrial biogenesis, protecting neural cells from oxidative stress and inflammation induced by amyloid peptides [151]. At the same time, astrocytes may exert neuroprotection at different stages of AD. Indeed, both astrogliosis and microgliosis, in response to amyloid, increase glial secretion of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which protects neurons from amyloid toxicity and increases amyloid clearance by microglia [152, 153]. Furthermore, astrocytes surrounding amyloid plaques show phagocytic activity and are able to phagocytize neuritic dystrophies both in mouse models and in AD patients’ brains [154]. Indeed, astrocytes are part of the brain’s glymphatic system, a clearance system for proteins and soluble solutes [133]. The astrocyte water channel aquaporin-4, expressed at the ends of astrocytes, facilitates this process and is important for Aβ clearance [155, 156] and probably also for tau clearance [133].

Astrocytes and adult neurogenesis

Astrocyte is the main cell type in the hippocampal niche of neurogenesis by number [135]. In the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and in the SVZ [157], astrocytes are in close contact with NSCs and contribute to the regulation of almost all stages of adult neurogenesis, from the proliferation of NSCs to the functional integration of new neurons [135]. In particular, molecules secreted by astrocytes increase the proliferation of adult NSCs. For example, in vitro studies found that the adenosine 50-triphosphate (ATP) through P2Y1-PLC-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling [158], the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor co-agonist (NMDAR) D-serine [159–161] and the fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2) act as factors in the proliferative induction of adult NSCs [162, 163]. In addition, several miRNAs expressed in astrocyte exosomes are known to regulate adult neurogenesis [164]. In addition to affecting proliferation, molecules secreted by astrocytes can also modulate other stages of adult neurogenesis, such as the migration and differentiation of progenitors into neurons, or the maturation, synaptic integration, and survival of newborn neurons [135]. For example, the first in vitro study examining the role of astrocytes in adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus showed that astrocyte-conditioned cell culture medium increases the differentiation of NSCs into neurons [165]. Neuronal differentiation of adult NSCs is also promoted in vitro through juxtacrine signaling by astrocyte secretion of ephrin-B2 and activation of EphB4 receptors on the stem cell [166]. In addition, astrocyte-derived soluble factor thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is known for its antiangiogenic activity and promotion of synaptogenesis during brain development [167]; it also increases adult NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation in vitro [167]. Consistently, adult TSP1-deficient mice exhibit reduced proliferation of adult NSCs [168]. Another secretory factor, neurogenesin-1, increases the neuronal fate of newly formed hippocampal cells [169], while IL-1b and IL-6 promote neuronal differentiation of adult NSCs/progenitors in vitro [170]. Finally, D-serine released from astrocytes has been shown to control dendritic maturation and functional integration of newborn hippocampal neurons [171].

Detrimental effects of glial cells in AD

The current theory focuses mainly on the neuroprotective functions of microglia and astrocytes in AD and their proneurogenic actions. However, it is worth noting that both types of glial cells have been found to contribute to the damaging effects in AD, mainly through the promotion of innate immunity and pro-inflammation and influencing the permeability of the blood-brain barrier [172, 173]. Specifically, both microglia and astrocytes interact with Aβ, and Aβ in turn activates microglia and astrocytes through TLRs to release neuroinflammatory mediators that promote neurodegeneration [174, 175]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines decrease the phagocytic activity of microglia and probably transform microglia into pro-inflammatory phenotypes [173]. In addition, pro-inflammatory microglia increase tau phosphorylation and aggravate tau pathology [176]. At the same time, reactive astrocytes have been found to release excessive amounts of GABA and glutamate, resulting in memory impairment and synaptic loss in an animal model of AD [177, 178]. Moreover, these cells contribute to the microcirculation dysregulation and blood-brain barrier disruption, which facilitates Aβ accumulation and disease progression [179, 180]. Finally, reactive astrocytes might even pave the way for the formation of early amyloid plaques [181]. Considering that AD has a long preclinical phase, this dual role of glial cells [182] is not incompatible with the current theory that easily explains the very early stages of the disease. Moreover, some aspects of neuroinflammation, even under chronic conditions, continue to promote microglial phagocytosis and Aβ containment, resulting in a neuroprotective function [183].

THE SCALING OF MOLECULAR PATHOLOGY TO THE MACROSCOPIC BRAIN

Braak staging model

According to Braak’s neuropathological staging [184–187], pathological tau aggregates in AD develop first in nerve cells of brainstem nuclei (subcortical stages a–c) that have projections ending in the cerebral cortex [188–190]. It appears that from the locus coeruleus (LC) of the pontine tegmentum [191–196], the lesions progress to a distinct portion of the cerebral cortex, the transentorhinal cortex (TEC) [197]. In cortical projection neurons, the resultant and originally nonargyrophilic pretangle protein, during cortical stages 1a and 1b, becomes transformed into argyrophilic neurofibrillary lesions that characterize subsequent NFT stages I–VI [189]. The neurofibrillary pathology advances from the TEC (NFT stage I) into the OB [198], the entorhinal cortex (EC), and the hippocampal formation (NFT stage II). During NFT stage III, tau pathology progresses from the TEC to the laterally adjoining basal temporal neocortex, and during NFT stage IV, it extends more widely to the temporal, insular, and frontal neocortices. In NFT stage V, cases display severe involvement of most neocortical association areas, leaving only the primary fields mildly involved or intact. In the end stage, NFT stage VI, even these areas become involved. The production of abnormal tau continues from the outset until the final stage of the pathological process [188, 189, 199]. In summary, in AD, the pathology progresses anterogradely from distinct predilection sites in the lower brainstem to distant but connected regions of the cerebral cortex, and it does so sequentially with little interindividual variation, albeit at different rates [189]. Considering the mechanism implicated in tau spreading, a great deal of data suggest that transcellular propagation of tau aggregates, or seeds, could underlie disease progression [200–207].

The prion-like seeding and spreading hypothesis of tau

According to the prion-like hypothesis, pathological tau can distribute from one cell to another, thus propagating pathology from affected brain areas to interconnected healthy areas, involving mechanisms similar to those of prion diseases [208]. This hypothesis could explain the hierarchical pathway of neurodegeneration described in Braak’s scheme [184]. The prion-like hypothesis involves two main stages, namely the seeding, that is the ability of abnormal tau to convert normal tau into a pathological form, and the propagation, that is the spread of pathological tau to connected neurons [209].

Abnormal tau has seeding capacity

Several studies support a seeding capacity of tau similar to that of prions [209]. In this regard, some authors showed that injection of tau aggregates extracted from mice overexpressing mutated tau (P301S) into mice overexpressing wild-type human tau is sufficient to induce tau pathology [201]. In particular, when a tau immunodepleted extract was injected, no pathology was detected, demonstrating that tau is the responsible factor of aggregation, as later confirmed by other research groups [210–212]. Most in vitro studies showed that incubated aggregates/seeds are internalized by endocytosis and promote aggregation of overexpressed tau in cell lines [203, 204, 210, 213–221]. Evidence that tau aggregates have prion-like seeding behavior come mostly from experimental models [222]. However, there is also evidence for seeding activity in tau aggregates derived from patients with tauopathy. Indeed, sarkosyl-insoluble PHFs extracted from AD brain tissue induce seeding in cultured cells and wild-type mice [223, 224]. In addition, in brain homogenates and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from AD cases, tau seeds have been found to induce non-aggregated tau aggregation in FRET-based biosensor assays, particularly in regions known to be devoid of phospho-tau deposits [220, 225]. Moreover, recent work showed that human CSF from AD patients can induce tau seeding in experimental models [226].

Seeded tau aggregation is templated

Other studies demonstrated that the seeded tau aggregation is templated [222]. Some authors, for example, observed that native P301S tau seeds derived from transgenic mice brains confer their highest seeding competence to less competent recombinant P301S tau seeds when co-incubated with them in vitro [227]. Under the light microscope, tau aggregates induced in cells or in vivo have the same morphological appearance as the parent tau seed, suggesting a templated conversion mechanism [222]. This has been demonstrated in many studies from Diamond’s laboratory, in which the formation of morphologically distinct tau seeds resembles the parent tau seed both in cell culture [228] and, more recently, in vivo [225]. That a templated conversion mechanism may be relevant to tauopathies in humans has been demonstrated by studies from the laboratories of Goedert and Tolnay, in which injection of brain homogenates of different tauopathies into the brains of mice expressing unaggregated human tau resulted in the formation of only the inclusions of the corresponding tauopathy [229].

Neuroanatomical spread of tau aggregates

Trans-synaptic propagation of pathological tau has been demonstrated using a number of different approaches in transgenic mice [222]. Some authors showed not only the induction of tau aggregation in rodent brains following intracerebral injection of brain homogenates containing tau seeds, but also the time-dependent appearance of tau pathology in anatomically connected brain regions [201]. Others reported the appearance of pathological tau in areas connected to sites injected with tau seeds or tau-expressing viral vectors [230–233]. Some authors used a model in which human tau expression was restricted to the entorhinal cortex alone, showing that the tau pathology was evident in anatomically connected regions that did not express the human tau transgene [202, 205]. Further studies in tau transgenic mice indicated that tau seeds predict disease spread by appearing in brain regions before the occurrence of any other pathological changes [215]. Interestingly, this finding explains the histopathological observation made by some authors more than 20 years ago [234]. These authors reported the absence of pathological tau in a frontal cortical region that was anatomically disconnected from the limbic region following neurosurgery, decades before the patient developed AD. Conversely, the authors found an extensive tau pathology in the immediately adjacent brain regions and limbic and isocortical areas [234].

Propagation involves several steps

The propagation of pathological tau to connected neurons consists of at least four steps [235]. First, tau must be secreted or released from donor neurons; second, it must undergo aggregation before or after being released; third, tau must be taken up by recipient neurons; and fourth, tau aggregation must be induced in recipient cells [236].

Currently, there is evidence that misfolded tau is indeed secreted [209, 212, 237]. However, the nature of secreted tau is debated in the literature [222, 238]. Tau is secreted mainly in free form [239–242], but it is also found within nanotubes [243, 244] or associated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) [245], such as exosomes [242, 246, 247] and ectosomes [239]. While nanotubes may be difficult to visualize in the human brain, phospho-tau-containing EVs have been found not only in the brains of transgenic mice [248, 249], but also in peripheral fluids (CSFs) [242, 250] and blood [251–253] of AD patients [209].

Considering the uptake step of tau by an adjacent recipient cell, in vitro studies showed that extracellular aggregates of tau can be internalized by naïve cells by promoting fibrillation of intracellular tau [203, 204, 254]. Tau pathology can be transferred between co-cultured cells [203, 204, 254] and also through synaptic contacts between neurons that facilitate the propagation of pathology [255]. Intracranial or peripheral administration of pathological tau [222, 256] and in vitro experiments have shown that tau is mainly internalized by active endocytic processes [203, 257]. In particular, three types of endocytosis have been described: bulk-endocytosis, actin-dependent macropinocytosis mediated by HSPGs on the cell surface, and clathrin-mediated endocytosis [208].

Once internalized, tau can escape endosomal vesicles by inducing their rupture [258, 259] and accumulate in the cytoplasm where it becomes a potential template for tau misfolding [208]. Indeed, pathogenic misfolded tau proteins act as “seeds” that recruit soluble endogenous tau into larger aberrant conformations [260] that slowly propagate into interconnected brain regions, as demonstrated in various animal models [235]. Although the biochemical mechanisms that drive the conversion of normal tau to the pathological form remain unclear, several models of tau seeding have been proposed [261, 262]. Finally, transcellular transfer of tau aggregates between serially cultured cells in microfluidic chambers was demonstrated [263]. In addition, diffusion of tau from neuron to neuron through trans-synaptic connections via exosomes has been reported to seed aggregates [242, 249]. However, other mechanisms that do not require secretion but a direct connection between cytoplasm might be involved [222]. Indeed, a recent work showed that nanotubes promote the interneuronal transfer of tau fibrils into neurons [243, 244].

Limitations of the seeding and spreading hypothesis

Although several pieces of evidence seem to support the seeding and spreading hypothesis of tau, many points still remain to be clarified [68, 264, 265]. Firstly, some authors pointed out that the methods used and data collected in some studies supporting the hypothesis are not all without some limitations [68, 265]. Secondly, the biochemical mechanism that drives the conversion of normal tau to the pathological form is still not clear [208]. Thirdly, the exact nature of the tau seeds responsible for the propagation of tau pathology remains controversial [222]. Furthermore, the specific pathways and mechanisms underlying the spread of pathological tau, including the mechanism of releasing from donor neurons and subsequent uptake by recipient neurons in AD, remain unclear [209, 235, 266]. In addition, the molecular forms of extracellular tau are not fully understood, and the physiological or pathological functions of this extracellular tau remain unknown [266]. Further investigations are then needed to clarify the relationship between the propagation of tau aggregates and tau-induced toxicity and degeneration [222]. Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that genetic variants identified as risk factors for tauopathies play a role in the propagation of tau pathology, but many more studies are needed to document this [222]. Finally, the contribution of selective vulnerability of neuronal populations as an alternative explanation of the spread of tau pathology needs to be clarified [222].

Microglia and astrocytes could be involved in the spread of pathological tau

It is worth noting that some studies highlighted the involvement of microglia in the spread of pathological tau [208]. Indeed, it has been reported that increased microglial activation accelerates the propagation of tau in the brain [267]. Furthermore, microglia were found to promote tau propagation [246, 268], as supported by the marked reduction in tau propagation through microglia depletion in two independent models of tauopathy [246]. The mechanism involved in the promotion of tau propagation by microglia has not been fully elucidated. However, tau was found in the EVs in the CSF of individuals with AD [239], and microglia were found to internalize tau seeds and degrade them [182]. When microglia fail to degrade these tau seeds, deleterious consequences occur, including the secretion of tau-containing exosomes that can spread to neurons [182].

Interestingly, tau was also found in astrocytes of individuals with AD [269]. Although tau was found in glial cells [270], astrocytes do not express this protein under physiological conditions [271], and the origin of tau in astrocytes in AD is still unclear [272]. One unproven possibility is that AD progression induces the translation of tau from the mRNA present in astrocytes [273]. Alternatively, astrocytes could also capture extracellular tau [228, 274, 275]. In this regard, astrocytes have specific heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and receptors, such as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LDR1), that can mediate the uptake of tau aggregates [133]. Aggregates can be internalized and processed by various mechanisms, including lysosomal degradation. Disruption of aquaporin-4 in perivascular astrocyte ends may contribute to the disruption of tau clearance and accumulation of tau aggregates in the CNS [133]. However, the microglial and especially astrocytic mechanisms that may contribute to pathological tau seeding are not yet fully understood [133]. As for microglia, it is sufficient to mention that they can also reduce the seeding activity of tau [268, 276–278], supporting the idea that microglia are indeed able to limit or promote the spread of tau [182]. Considering astrocytes, one hypothesis is that tau pathology spreads from one astrocyte to another, possibly through astrocyte gap junction networks and tunneling nanotubes across brain regions [266, 279]. Astrocyte engulfment of tau-containing synapses may be another pathway by which astrocytes contribute to the spread of tau in AD [133].

The possible involvement of glial cells in tau spreading is consistent with the current theory. In this case, microglia and astrocytes activated by Aβ deposition would not only promote tau pathogenesis through their proneurogenic effect, but also contribute to the spread of tau aggregates in the brain.

Open questions left in the Braak model

Despite the indubitable value of the Braak staging model, some open questions remain.

First, the view that nonthalamic nuclei would be the first site of tau pathology has been questioned [280]. Indeed, these nuclei are equipped with a type of termination (i.e., nonjunctional varicosities) [191, 196, 281, 282], supporting a diffusive mode of transmission [191, 196, 281, 283–285] that is not suitable for neuron-to-neuron transmission of abnormal tau as provided by the model. Indeed, recent findings have suggested that TEC/EC are actually the first site that develops early tau pathology [286]. In particular, tau seeding activity that precedes detectable NFTs was found in the LC only after it was already prominent in the TEC/EC, i.e., at later NFT stages (IV–VI), suggesting the idea that tau seeds spread from the TEC/EC to the LC and then to more distant cortical regions [286].

Second, to date, a clear explanation of why tau pathology begins in TEC/EC seems lacking. Indeed, it is not easy to contextualize this finding in the frame of classical amyloid theory, considering that amyloid plaques first appear in the association cortices of the temporal lobe, at some distance from the TEC/EC where damaged neurons containing NFTs are first found [187, 287]. Additionally, further studies examining the early degeneration of the lateral EC have reported that levels of amyloid peptides in this region are not higher than those in other, less affected regions [288, 289].

Third, despite the evidence that early tau pathology emerges in entorhinal layer II cells at Braak stage II [186] and that these cells project to the DG by the perforant path [290–294], the DG is not affected by tau pathology at early stages. Indeed, granule cells of the DG remain uninvolved in Braak stage III, and some tau pathology emerges only at stage IV [186]. At the same time, hippocampal CA1 cells receiving projections from entorhinal layer III cells [292, 293] are impacted far earlier, starting at Braak stage II [186].

Finally, a clear and accepted explanation of the peculiar regional distribution of tau lesions and subsequent neurodegeneration in EOAD, especially in the syndromic variants of AD, is lacking in the Braak model.

A new model of tau spreading in the medial temporal lobe

The current theory provides a new model of tau spreading in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (Fig. 1). According to the new model, tau pathology begins in NSCs within the niches of adult neurogenesis. In particular, in LOAD, the initial tau pathology, likely in the form of soluble aggregates of misfolded and hyperphosphorylated but nonfibrillar tau protein [280], originates in the SGZ in the hippocampal DG. From this site, seeds of tau pathology spread retrogradely to the EC through the perforant path. From here on out, anterograde transmission flanks retrograde transmission. Therefore, by virtue of reciprocal connections between the EC and TEC [294–297], the TEC receives tau seeds both anterogradely and retrogradely. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the EC projections to the TEC are input to layer II [296, 297], where NFTs are first found [185, 298]. Then, from EC/TEC, the pattern of distribution of tau pathology follows the Braak model. However, a further difference may occur. Indeed, according to the current model, it cannot be excluded that some further foci of degeneration could start locally in some regions of the cortex, provoked by neuroblasts carrying the seeds of tau pathology arising from the V-SVZ niche. In this case, in LOAD, the primary regional distribution pattern of tau pathology in the MTL would be complicated by concurrent foci of pathology that emerge locally in neocortical regions. In the same context, it is noteworthy that the OB is the arrival point of migrating neuroblasts from the V-SVZ along the RMS, and at the same time, many findings support early involvement of this region in AD [198, 299–301]. However, olfactory structures, including the OB, anterior olfactory nucleus, and piriform cortex, send projections to the superficial layers of EC [302, 303]. Therefore, retrograde transmission of tau pathology from the EC to the OB could be a more parsimonious explanation. The current model seems plausible and coherent with some findings in the literature. In this regard, it is worth noting that retrograde transmission has been found to be possible. Indeed, projection neurons generate long axons to transmit information from one site to another, and for this purpose, their axons have mechanisms for both anterograde and retrograde transport of various cargos [222, 280]. Moreover, the idea of retrograde transmission of tau pathology in the MTL in AD has already been suggested [304]. In addition, the pattern of connections among the DG, EC and TEC is compatible with the new model of both retrograde and anterograde transmission. In particular, the DG receives projections from entorhinal layer II cells, where tau pathology is found early in EC [186, 305]. Moreover, projections from the EC to the perirhinal cortex that includes the TEC terminate most heavily in and around layer II, where tau pathology is first found in the TEC [184, 298].

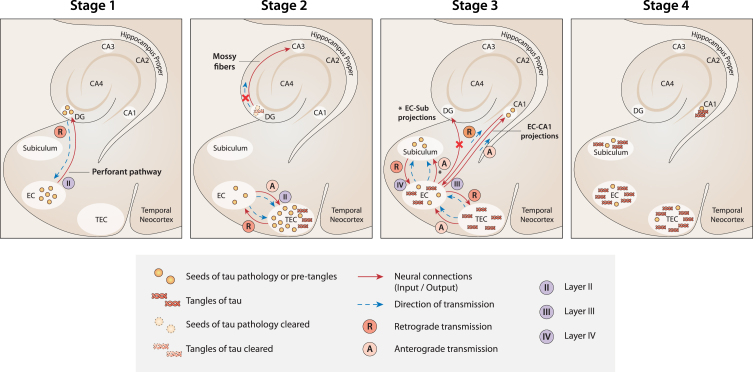

Fig. 1.

A new model of the spread of tau pathology in the MTL according to current theory. Stage 1: The first seeds of tau pathology develop in NSCs in the SGZ niche of the DG. Then, they spread from the DG to the EC by retrograde transmission along the connections of the perforant pathway. Stage 2: Seeds of tau pathology spread from the EC to the TEC by both anterograde and retrograde transmission along the multiple connections between the two regions. Because of the massive load of tau pathology accumulated in the TEC, tangles develop here first. At the same time, tangle formation is suppressed (or delayed) in the DG because of the strong clearance activity that usually occurs in the neurogenesis niches. As a result, the transmission of tau pathology from the DG to CA3 is nullified (red cross). Stage 3: Seeds of tau pathology spread from the EC to the CA1 and subiculum along the EC-CA1 and EC-subiculum projections, respectively. In contrast, the seeds of tau pathology would not spread anterogradely to the DG (red cross), because the neuronal connections between the EC and DG are already deteriorated at this stage due to the transmission of tau pathology in the reverse (retrograde) direction in the previous stage (Stage 1). Stage 4. When tau tangles emerge in the CA1 and subiculum (starting from Braak stage II), the DG and CA3 are not yet affected. Figure 1 was produced by Antonio Garcia, scientific illustrator from Bio-Graphics.

Possible solution to the questions left in Braak staging

Interestingly, the current model seems to offer possible explanations for the open questions left in Braak staging.

First, it is coherent with the recent view considering the LC and other nonthalamic nuclei as not the primary sites for tau spreading in the MTL. At the same time, the core hypothesis of tau pathogenesis as linked to adult neurogenesis and migration offers a speculative explanation for the emergence of tau pathology in these sites. In fact, the LC is highly connected to the hypothalamus, and constitutive neurogenesis in the adult hypothalamus of mammals, including rodents, rats, mice, voles [306–314], and sheep [315], has been documented [316].

Second, according to the current model, tau pathology emerges first in the TEC because this region receives the massive seeds of tau pathology from the EC, both anterogradely and retrogradely, through the multiple reciprocal connections between the two regions. Conversely, the EC receives the seeds of tau pathology from the DG only by retrograde transmission (Fig. 1, Stage 1). Therefore, in the current model, NFTs emerge first in TEC because the initial load of tau pathology would be greater than in the EC (Fig. 1, Stage 2).

Third, the absence of tau pathology in the DG at early Braak stages is due to the strong activity of clearance usually occurring in the neurogenic niches [74, 75]. According to this view, although seeds of tau pathology originate in NSCs in the SGZ niche and spread retrogradely toward the EC by a perforant path, the formation and accumulation of NFTs is suppressed or at least delayed in NSCs in the DG (Fig. 1, Stage 2). For the same reason, CA3 [118], which receives excitatory outputs from the DG, is not impacted by tau pathology at early stages. Instead, tau pathology emerges first in CA3 at Braak stages III-IV [186]. In the same context, it is relevant to note that adult-generated neurons in the SGZ receive local connections from multiple types of GABAergic interneurons [317], whose inputs to the niche are fundamental for maintaining a healthy level of neurogenesis under normal conditions [318, 319]. Interestingly, these same GABAergic interneurons have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to AD pathologies, such as NFTs of phosphorylated tau protein [317, 320–323]. Therefore, GABAergic interneurons could be plausible candidates to convey transmission of the first tau seeds originating in SGZ NSCs. Strictly related to the previous point, the current model seems to offer a plausible explanation for why tau pathology spreads early from the EC overall to the hippocampal CA1 region, while it seems not to target the DG, despite that the EC and the DG are highly connected by the perforant path. Damage to the perforant path between the lateral EC and DG occurs unusually early in AD [324]. The long axons of projection neurons are in fact not well equipped to degrade or eliminate pathological proteinaceous aggregates [189, 325]. Based on the current model, the seeds of tau pathology, after which the EC, and more so the TEC, have been impacted, would spread anterogradely from the EC to multiple regions, as in the classical Braak model. However, at this point, the current view predicts that the DG would be primarily disconnected from the EC because the entorhinal perforant projections toward the DG would already be deteriorated due to the precedent retrograde transmission of tau pathology along the same projections in the opposite direction, from the DG to the EC, during the first stage of disease. Consequently, the connections between the EC and CA1 (and subiculum) are unique undamaged fibers in the perforant path available for tau seed transmission at this stage (Fig. 1, Stage 3).

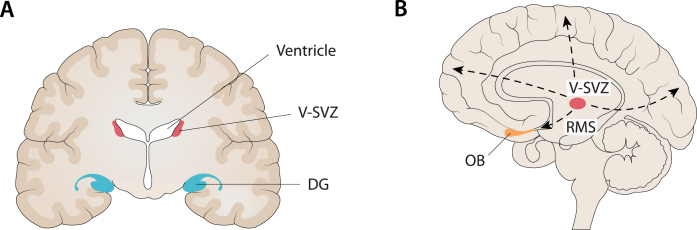

Finally, the current model seems to offer a plausible explanation for the peculiar distribution of tau pathology in EOAD. Individuals with EOAD may present with striking neurobehavioral phenotypes, reflecting damage to the language systems [326], visual systems [327], or frontal-executive systems [328]. In general, EOAD is more likely to present with atypical clinical phenotypes than LOAD patients [329]. In one study, approximately 25% of EOAD patients presented with a nonamnestic phenotype in whom visual or apraxic and language phenotypes predominated [330]. In another study, almost 60–70% of EOAD patients exhibited atypical patterns of brain atrophy [329]. Interestingly, the focus and system-specific neurobehavioral features in EOAD variants do not reflect regional accentuation of Aβ, but they do show strong correlations with the pattern of glucose hypometabolism and atrophy [331–334]. More generally, despite their differences, in autosomal dominant AD (ADAD), EOAD and LOAD, the distribution of Aβ deposition throughout the brain is similar (with the exception of Aβ deposition in the striatum in ADAD), affecting large confluent areas of the association cortex and overlapping with a set of brain regions active at rest [335–339]. Therefore, phenotypic heterogeneity in AD is not easy to explain considering both the frame of the classical amyloid theory and the primary pattern of regional distribution of tau pathology starting from the MTL according to Braak staging. In the current model, EOAD and LOAD exhibit different regional distributions of tau pathology and subsequent degeneration because the V-SVZ niche is primarily active in EOAD, while the SGZ niche is primarily active in LOAD. Accordingly, EOAD especially impacts regions on the dorsal cortex, whereas LOAD impacts the MTL [340] (Fig. 2). Moreover, activated microglia surrounding Aβ plaques release chemokines that attract and drive migrating neuroblasts toward the regions of Aβ deposition, similar to what happens in brain injury [125–131]. Consequently, especially in EOAD, migrating neuroblasts deviate from the RMS to the OB and take different paths toward various regions of the cortex, carrying the seeds of tau pathology to those locations. In summary, the redirection of migrating neuroblasts to multiple possible destinations in the cortex is the basis of heterogeneity in the regional distribution of tau pathology and subsequent degeneration in atypical EOAD syndromes (Fig. 2). In addition, as already reported, long-distance migration throughout the inhibitory environment of the adult brain could contribute to augmenting tau phosphorylation.

Fig. 2.

Compatibility between the localization of the main niches of adult neurogenesis and the core regions targeted in AD. A) One of the main niches of adult neurogenesis is the sub-granular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus (DG) in the hippocampus. At the same time, the hippocampus is the first major region targeted in AD, especially when late-onset AD (LOAD) is considered. B) Another main niche in adult neurogenesis is the ventricular subventricular zone (V-SVZ) along the lateral ventricles. From this niche, through several long migrations to the cortex (dashed lines), it is possible to reach every cortical region (e.g., frontal, fronto-parietal, occipital) that is targeted by AD, especially when considering early-onset AD (EOAD) and syndromic variants of AD. In addition, it is noteworthy that the olfactory bulb (OB) is the end point of neuroblasts migrating from the V-SVZ along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) and, at the same time, many findings support an early involvement of this region in AD. Figure 2 was produced by Antonio Garcia, scientific illustrator from Bio-Graphics.

Interestingly, recent in vivo tau-PET imaging studies in AD have revealed substantial heterogeneity in tau deposition patterns with significant deviations from Braak’s scheme [334, 341, 342]. These findings are in line with the four subtypes previously identified from neuropathology and neuroimaging studies based on the distribution of NFTs and patterns of brain atrophy, respectively: hippocampal-sparing AD, limbic-predominant AD, typical AD, and minimal atrophy AD [343–354]. In addition, some studies confirmed atypical patterns of tau deposition with elevated tau-PET signal in the occipital and parietal cortex [355], left temporo-parietal areas (logopenic) [356] and, similarly, perirolandic areas (corticobasal syndrome due to AD) [357, 358] reflecting the clinical variants most frequently associated with EOAD [359, 360]. Interestingly, some of these tau-PET imaging studies in AD found that pathological tau accumulates in the associative cortex, completely sparing the hippocampus [342, 350, 359, 361, 362]. This finding strongly supports the idea of distinct foci of early tau deposition and multiple pathways of tau diffusion in AD, including cases without any involvement of the hippocampus and/or entorhinal cortex [342, 348].

This scenario does not fit well with Braak’s staging system and seems more consistent with the current theory that predicts different niches of adult neurogenesis and multiple pathways of migration to the cortex.

Cortical arealization in development and AD

Considering that migration paths throughout the cortex, including the RMS, are mostly quiescent in the human adult cortex, the current model would be plausible only provided that a strong pro-neurogenic action would foster neurogenesis and support highly demanding migrations. In this respect, the accumulation of Aβ deposits and consequent microglial activation are key factors. However, the distribution of Aβ throughout the brain is diffuse and similar in LOAD, EOAD, and FAD, as well as in AD variants. Therefore, it is not plausible that microglia surrounding Aβ plaques signal a precise direction to migrating neuroblasts, similar to focal brain insults, such as stroke. Furthermore, the current model cannot explain why only some directions of migration are undertaken—those corresponding to the paths toward the regions impacted in well-known AD variants, e.g., posterior, frontal, and left perisylvian—and not others. At this point, I speculate that not only should a further source of signals drive migration throughout the cortex in EOAD but also that this source should contain information about brain topography, likely at the macroscopic level of hemispheres, lobes, and gyres, to efficiently work. Surprisingly, I found that the program under cortical arealization in development perfectly fits this idea. In particular, there is a complex mechanism regulating the progressive patterning and correct localization of brain areas during development [363], which necessarily uses some spatial information related to brain topography to work. This mechanism would be mostly, even if not exclusively, under the genetic control of factors with discrete expression in the cortical field (protomap models). Moreover, some findings have suggested that the main spatial information used is related to simple brain axes. In particular, animal studies have demonstrated that there is an anterior-posterior (A-P) gradient of gene expression of morphogens or transcription factors, such that specific genetic factors enlarge rostral (motor) areas at the expense of caudal (sensory) areas, and vice versa [363]. In addition to this A-P gradient, there is evidence for graded expression patterns along with other distributions, including the medial-lateral (M-L) and dorsal-ventral (D-V) axes.

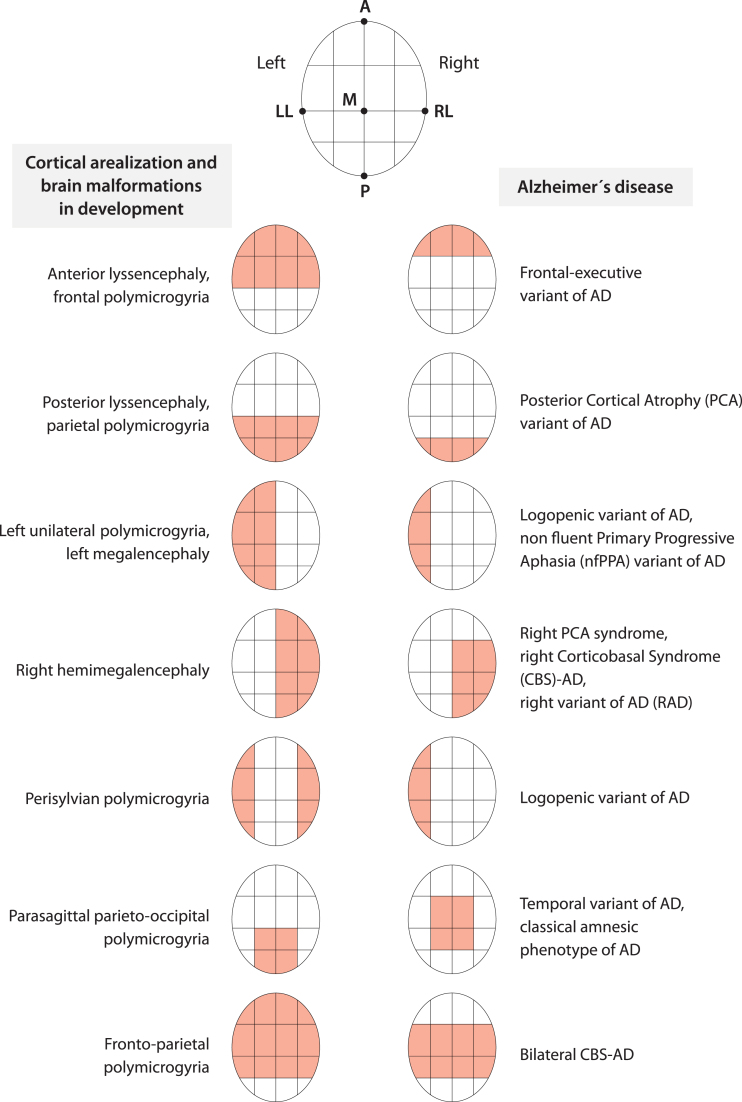

The failure of certain processes (e.g., cell proliferation, migration, and abnormal organization) during cortex development has been associated with several cortical malformations [364]. What is interesting is that most malformations do not involve the entire cortex uniformly but have regions of maximum severity. For example, some malformations (schizencephaly, megalencephaly) may alternately involve one or both hemispheres. Another type of malformation (e.g., lissencephaly) may have two forms, one with maximum severity in the frontal lobes and the other with maximum severity in the occipital lobes [364]. Another more diverse malformation (i.e., polymicrogyria) shows a highly heterogeneous topographic distribution (e.g., frontal, frontoparietal, perisylvian, parasagittal parieto-occipital, parietal, generalized), with a predilection for the perisylvian cortex [365]. As might be expected considering that the malformations are due to the failure of certain processes during cortical development, by observing the distribution over the cortex of some of these developmental malformations, we can easily recognize the structure of the A-P, D-V, and M-L axes underlying the cortical arealization process (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the regions targeted by degeneration during early stages in AD, considering LOAD, EOAD, FAD and all the syndromic variants together, seem to be arranged at opposite locations along the same A-P, D-V, and M-L brain axes [366] (Fig. 3). In other words, AD (and more specifically EOAD) and the program of cortical arealization in development seem to use the same alphabet of spatial information on brain topography (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cortical arealization in development and AD appear to share the same alphabet of spatial information about brain topography. The coarse distribution over the cortex of brain malformations due to the failure of the arealization program during development and the key regions targeted by AD, considering all phenotypes, seem to follow the same few topographical instructions related to anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, dorsal-ventral brain axes and a simple left-right hemisphere specification. Figure 3 was produced by Antonio Garcia, scientific illustrator from Bio-Graphics. This is a modified version of Fig. 1 in Abbate (2018) [366].

In summary, I speculate that in EOAD, when neuroblasts leave the V-SVZ niche and start migrating, the signals from microglia activated by Aβ deposition provoke path redirection from the RMS and, at the same time, sustain long-distance migration. However, reactivation of the genetic program of arealization during development would contribute to signaling the direction for migrating neuroblasts to follow.

DISCUSSION

Adult neurogenesis in brain injury and AD

The study of adult neurogenesis and migration in brain injury, keeping in mind the peculiarity of Aβ deposition compared to other types of injury, seems to support the notions of increased neurogenesis, promotion, and redirection of neuroblast migration, as well as reactivation of quiescent paths, recognized in the current theory. Indeed, in rodents, various pathological changes and injuries, e.g., ischemia or TBI, stimulate neurogenesis in the V-SVZ [367–369] and in the DG [370–374]. In addition, in the injured adult brain, neuroblasts generated in the V-SVZ migrate toward the site of injury [125, 126, 375–377], driven by various guidance cues, such as chemoattractants secreted by injury-activated astrocytes, microglia, and vascular endothelial cells in the injured area [73, 378]. Accordingly, multiple studies have shown significant intensification of neuroblast migration [125, 126, 367, 379] under these conditions. Therefore, the migratory paths from the V-SVZ, which are largely quiescent in the adult brain [380], could be reactivated in response to injury [367].

Over the years epileptic seizures, as well as stroke and TBI, were demonstrated to provoke functional alterations in the hippocampal neurogenic cascade that were characterized under the umbrella term “aberrant neurogenesis” [381, 382]. In particular, aberrant neurogenesis encompasses multiple (dys)functional outcomes, including excessive activation of NSCs [383, 384], alterations in NSC fate [383, 385] with a shift from neurogenesis to astrogenesis, downregulation of the proliferative capacity of NSCs, neural progenitor cells or neuroblasts [385–387], abnormal development and length of the dendritic tree of newborn neurons [388, 389], and ectopic migration of newborn neurons [390]. Interestingly, some authors, both in postmortem AD patients and in a transgenic (3xTg) AD mouse model, found that hyperphosphorylated tau, especially when expressed in GABAergic interneurons in the DG, was related to multiple alterations in SGZ NSCs strictly resembling the cardinal features of aberrant neurogenesis [317]. This finding suggests that tau-mediated aberrant neurogenesis also occurs in AD.

The link between AD and adult neurogenesis

A link between AD and adult neurogenesis has been recognized for some time. Indeed, AD and adult neurogenesis are not only linked by common sites where early pathology occurs and newly born neurons integrate in the preexisting circuitry (e.g., MTL, OB) but also share a number of common molecules in both processes [391–395]. In particular, molecular players in AD, including apolipoprotein E (ApoE), APP, and presenilin 1 (PS1), as well as their metabolites, play a role in adult neurogenesis [392, 394]. Further critical signals in AD have been found to regulate neurogenesis, such tau [38, 317, 396], Notch1 [384, 397], cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) [398–406], and Wnt/β-catenin [407–410]. Furthermore, some authors have shown that blocking adult hippocampal neurogenesis in an AD mouse model exacerbated neuronal loss and cognitive impairment, while inducing adult hippocampal neurogenesis together with brain-derived neurotrophic factor improved cognition in AD mice [411]. Another study observed markers of increased neurogenesis in the DG of rare “resilient” individuals who remained cognitively intact, despite the presence of neuropathological features associated with AD, compared to AD and mild cognitive impairment patients [412]. Therefore, the prevailing view in the field is that impaired neurogenesis is a key contributing factor to AD pathology-driven neuronal dysfunction [394, 413–415]. Actually, the study of adult neurogenesis in postmortem AD patients and AD animal models has yielded conflicting results, frequently reporting a decrease [392, 416–420], but sometimes also an increase [392, 420, 421], in adult neurogenesis. The current theory predicts a complex relationship between the rate of neurogenesis and AD, depending on disease stage. In the first stage, there is a long-lasting tonic phase of reactive neurogenesis promoted by activated microglia triggered by Aβ deposition. Accordingly, the rate of neurogenesis is augmented, and tau pathogenesis is amplified. Then, the accumulation of tau aggregates in the niches start to have detrimental effects, likely ultimately reducing the rate of neurogenesis. This represents a phase of aberrant neurogenesis in AD that is most likely tau-mediated. A further phase could start when degeneration first occurs in the brain. Indeed, similar to what happens in stroke or TBI, cell death in the injured area stimulates the release of signals that could provoke a second cycle of aberrant neurogenesis in AD. The contrasting results found in the study of neurogenesis in AD seem to reflect this suspected complex relationship.

Adult neurogenesis, AD, and primary age-related tauopathy

The relative independence between the two processes driving amyloid and tau pathology in the new paradigm allows us to consider tau pathogenesis without Aβ deposition. Consequently, the finding of tau pathology uncoupled from amyloid pathology, as found, for example, in primary age-related tauopathy (PART) [422], seems compatible with the current paradigm. Moreover, the current model seems to fit well in explaining tau pathogenesis in PART. Indeed, the topography of tau lesions in PART is consistent with a possible origin in the NSCs within the SGZ niche. In particular, NFT changes in PART are usually restricted to the MTL and adjacent regions [132, 422, 423]. Later age of onset [422, 424–427], as well as limited spreading of tau pathology outside the MTL in PART compared to AD, would be due to the lack of a promoting effect on both neurogenesis and tau spreading by microglia in the absence of Aβ deposition. Therefore, the core hypothesis of tau pathogenesis as linked to adult neurogenesis and migration seems capable of combining AD and PART in a unique scenario. Some significant similarities identified between the two diseases support this idea. For example, NFTs in both disorders are identical, sharing both 3 repeat and 4 repeat tau isoforms and a 22–25 nm paired helical filamentous ultrastructure [422, 424, 428]. Moreover, phosphorylated tau lesions have the same topographic distribution in both PART and early AD [184, 424, 429]. In more detail, it has been reported that neurons in layer II of the TEC, a crucial region of early involvement in AD [184, 298], are also affected by neurofibrillary degeneration in PART [184, 298].

Adult neurogenesis, AD, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy

Unexpectedly, some findings from the study of a different disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) [430], seem to support the core hypothesis of tau pathogenesis as linked to adult neurogenesis and migration. CTE is a progressive tauopathy with distinctive clinical and pathological features that occurs after repetitive mild TBIs [430]. Microscopically, CTE is characterized primarily by NFTs and astrocytic tangles, with a relative absence of Aβ peptide deposits [431–447]. The evidence suggests that CTE begins focally, usually perivascularly, especially around small cerebral vessels, and at the depths of the sulci in the cerebral cortex [430, 446, 448–450]. Interestingly, some data have shown that the perivascular regions and the depths of the cerebral sulci are the most stressed regions, when the brain is subjected to rapid acceleration, deceleration, or rotational forces, such as occurs in mild TBI [451]. Thus, the highest concentration of phosphorylated tau correlates to the highest areas of stress in CTE [451]. Subsequently, pathological NFTs spread from these areas to adjacent superficial cortical layers. Considering the findings of an increase in the generation of new neurons in the niches [368, 452] and redirection of neuroblast migration to the injury site after TBI [73], V-SVZ neuroblast migration is ultimately redirected to the perivascular regions and the depths of the cerebral sulci in CTE because these regions are the primary sites of injury. Therefore, the current model of tau pathogenesis based on adult neurogenesis and migration in a special case of brain injury fits well for explaining the peculiar sites of pathological tau deposition in CTE. Indeed, the distinct feature of prominent periventricular NFTs in CTE is in agreement with the location of the V-SVZ niche. Therefore, this model also seems to combine neurodegeneration (AD) with traumatic degenerative dementia (CTE) in a unique scenario. The fact that the isoform profile and phosphorylation state of CTE are very similar to those in AD [285, 308, 309] agrees with this idea. In particular, neuronal tau pathology in CTE shows immunoreactivity to both 3R and 4R tau, as in AD [430, 453, 454]. In addition, tau in both AD and CTE is phosphorylated at the same amino acids, including tau phosphorylated at threonine 231, and all six isoforms are present, leading to the observation that NFTs associated with AD are indistinguishable from those that occur in TBI [453].

Adult neurogenesis, AD, and the antimicrobial protection hypothesis

The current theory does not focus on the process that drives the initial deposition of Aβ. Consequently, it is compatible with a recent etiologic model of AD, namely the Antimicrobial Protection hypothesis, which views Aβ deposition in a new light compared to the classic amyloid hypothesis [455]. In this model, Aβ deposition is an innate immune response that normally protects against genuine, or misperceived, microbial infection in the brain. Aβ first traps and neutralizes invading pathogens in Aβ. Fibrillation of Aβ stimulates neuroinflammatory pathways that help fight infection and clear Aβ/pathogen deposits. In AD, chronic activation of this pathway leads to sustained inflammation and neurodegeneration. This new model is supported by several lines of evidence.

Indeed, many studies documented the presence of abnormal levels of pathogens in the AD brain, including viral, bacterial, and fungal infections [456], particularly herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) [457], Chlamydia pneumoniae, and several types of spirochetes [458–461].

Most importantly, Aβ showed consistent antimicrobial activity. Soscia et al. (2010) [462] were the first to demonstrate antibacterial and antifungal activity of Aβ peptide against numerous pathogens. These authors found that Aβ can act as an antimicrobial peptide and that Aβ deposition can be rapidly induced in mice, in Caenorhabditis elegans models, and in AD-based neural cell models as an innate immune defense mechanism against microbial pathogens [462, 463]. Interestingly, synthetic Aβ can reduce the growth of common pathogens up to 200-fold in vitro [462]. Some authors reported that Aβ peptide strongly inhibits the infectivity of influenza A virus in cell culture [464], while others [465, 466] reported similar results for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Further studies showed that Aβ peptides can protect the host against brain infections with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, HSV-1, and HHV-6 [463, 467].

Moreover, several evidence have mainly linked HSV-1 infections to the pathogenesis of AD [468–470]. In fact, HSV-1 DNA has been detected more frequently in the brains of AD patients than in healthy controls and has been found to be co-localized with Aβ [471]. In addition, some studies verified the presence of IgM anti-HSV-1 antibodies in most people with AD [472]. Moreover, high titers of anti-HSV-1 antibodies have been found to be positively correlated with the development of AD-like cognitive dysfunction [473], with symptoms of mild cognitive impairment [474], and with bilateral temporal and orbitofrontal cortical gray matter volume [475]. In addition, some studies suggested that in people carrying the APOE ɛ4 allele and, therefore, predisposed to develop AD, HSV-1 infection significantly increases the risk of AD [476, 477]. Furthermore, HSV-1 was shown to produce calcium-dependent GSK-3β activation, which results in hyperphosphorylation of tau and AβPP proteins as well as Aβ accumulation [478, 479]. Also, HSV-1 reactivation was associated with neuroinflammation and the appearance of several markers of neurodegeneration [478–480]. In addition, the brain regions mainly affected during acute encephalitis produced by active replication of HSV-1 in neuronal cells of the brain (herpes simplex encephalitis) [481], both in humans and in experimental rodent models, are the same regions impaired in AD (limbic system, frontal and temporal cortex) [482–488]. Consistently, a high percentage of brains of elderly people contain latent HSV-1 DNA especially in CNS regions critically involved in AD [476, 489]. More recently, some authors found that a mouse model of HSV-1 infection and recurrent reactivation showed a picture resembling the phenotype of sporadic AD [490]. Indeed, after infection and multiple rounds of reactivation of the virus promoting its spread within the brain, infected mice showed accumulation of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins in several brain areas, including the hippocampus, and these molecular changes were accompanied by memory deficits [490].

Interestingly, the current adult neurogenesis theory of AD is not only compatible with the antimicrobial protection hypothesis, but also shows some relevant points of convergence with it. It is noteworthy that HSV-1 latency has been observed mainly within the lateral ventricles in the SVZ, hippocampus, and brainstem before being detected in the neurons of the trigeminal ganglion [491, 492], and also in the olfactory bulbs, frontal cortex, and cerebellum in some studies [492]. More generally, the olfactory nerve, which leads to the lateral entorhinal cortex, is a portal of entry of HSV-1 [493] and other viruses [494], as well as Chlamydia pneumoniae, into the brain [495]. In addition, brainstem areas that harbor latent HSV directly irrigate these brain regions [190], and from the brainstem, neurons project to the thalamus and eventually reach the sensory cortex. Thus, it is interesting to note that the sites of HSV-1 latency (hippocampus and SVZ) overlap with the major niches of adult neurogenesis, and the pathways of HSV-1 infection seem consistent with the network of connected regions considered relevant in current theory in both LOAD (hippocampus - EC - OB - brainstem) and EOAD (SVZ - OB). Based on the finding that the preferred sites of HSV-1 latency are in the niches of adult neurogenesis (hippocampus and SVZ), ependymal cells and neural progenitor cells turn out to be highly susceptible to HSV-1 infection [491, 496–498]. Indeed, HSV-1 readily replicates in these cells during acute encephalitis [496, 498], and viral lytic-associated proteins were detected in these cells during latency [498]. The presence of HSV-1 in lateral ventricle ependymal cells and neural progenitor cells during latent infection alters the proliferation of NPCs as a consequence of fibroblast growth factor 2 deficiency [499], whereas HSV-1 replication during acute encephalitis results in their loss and altered differentiation [496, 498]. Interestingly, a recent study showed that HSV-1 affects adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo by reducing the proliferation of NSCs and their neuronal differentiation in the SGZ of the hippocampal DG, through intracellular accumulation of Aβ, without inducing cell death [500, 501]. Indeed, anti-Aβ antibodies or experimental mouse models lacking APP (and thus unable to form Aβ) reverse the impairment of neurogenesis induced by HSV-1 infection [500]. Furthermore, impairment of adult hippocampal neurogenesis occurs when cognitive dysfunction induced by HSV-1 infection is not yet present, suggesting a role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the pathogenesis of AD [501].

Main unresolved questions in the field and possible solutions

The scenario proposed in the current theory seems to offer possible explanations for some unresolved questions in dementia and AD research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unresolved questions in the field and possible explanations according to current theory

| Open question in the field | Possible solution according to current theory | |