Abstract

This cohort study of health data from 2 regions in Sweden examines incidence rates of post–COVID-19 among children and compares incidence rates by demographic and clinical characteristics.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic it has become increasingly clear that children have not been as severely affected as adults in the acute phase of the infection, with the exception of those affected by multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).1,2 In accordance with adults, some children seem to be affected by persistent long-term symptoms of COVID-19, commonly referred to as post–COVID-19 condition (PCC).3 The frequency of PCC in the pediatric population is to a large extent unknown, and the occurrence in subgroups is not completely understood. The aim of this descriptive study was to describe the incidence of PCC in children and different subgroups of children using a unique population-based cohort with near-complete follow-up in high-quality Swedish registers.

Methods

We included all children ages 6 to 17 years residing in the 2 largest Swedish regions and retrieved information on both inpatient and outpatient care from specialists and primary health care clinicians using high-quality national or regional registers with near-complete coverage (eMethods in Supplement 1). The inclusion criterion was COVID-19 infection between January 31, 2020, and February 9, 2022. PCC was defined by International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code U09.9 (used in Sweden since October 20204,5) as the main or secondary diagnosis occurring 28 days or more after the COVID-19 infection. Follow-up ended at the earliest of: PCC diagnosis, emigration, death, or end of study (November 30, 2022). Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) and cumulative incidence are presented for the total cohort and according to subgroups. Data were analyzed with R Statistical Software version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

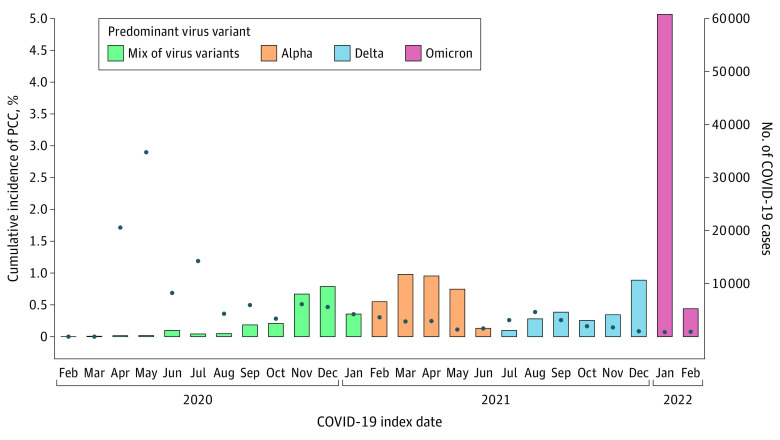

A total of 162 383 children (81 789 boys [50.4%], 80 594 girls [49.6%]), with a mean (SD) age of 12.0 (3.5) years at study start, had experienced a COVID-19 infection. Only a small proportion (529 [0.3%]) had been hospitalized due to COVID-19 and none of the children with PCC had been treated in intensive care. We found a PCC diagnosis in 326 children (0.2%) with COVID-19 (Figure). We observed numerically higher incidence rates of PCC cases among girls than boys (incidence rate per 100 person-years: 0.19; 95% CI, 0.16-0.22 vs 0.12; 95% CI, 0.10-0.14), older than younger children (age 12 to 17 years, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.17-0.22 vs 0.11; 95% CI, 0.09-0.14), with vs without comorbidities (any, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.14-0.18 vs none, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.07-0.15), and among hospitalized compared with nonhospitalized for acute COVID-19 (1.25; 95% CI, 0.62-2.23 vs 0.15; 95% CI, 0.13-0.17) (Table). Similar PCC occurrence was seen across categories of parental education. Children who had a diagnosis of MIS-C (63 children) showed an increased occurrence of PCC diagnosis compared with children without MIS-C. In addition, we observed a 6-fold higher occurrence of PCC if any of the parents had a PCC diagnosis (Table).

Figure. Total COVID-19 Cases and Incidence of of Post–COVID-19 Condition (PCC) by Date.

Number of incident cases of COVID-19 (bars) and proportion of COVID-19 cases developing PCC (blue dots) among children ages 6 to 17 years with COVID-19 from the 2 largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, based on both primary health care data and inpatient and outpatient specialist health care data, until November 30, 2022. Specific time periods of predominant virus variants of concern indicated. Full-scale polymerase chain reaction testing was not implemented in Sweden until late August 2020, therefore, the percentage of PCC cases during the first 7 months should be interpreted with caution.

Table. Cohort Incidence Rate and Cumulative Incidence of PCC Diagnosis.

| Characteristics | During follow-up, No. | Occurrence of PCC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCC | No PCC | Incidence rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | Cumulative incidence, % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 326 | 162 057 | 0.15 (0.14-0.17) | 0.20 (0.18-0.22) |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | 128 (39.2) | 81 661 (50.4) | 0.12 (0.10-0.14) | 0.16 (0.13-0.19) |

| Girls | 198 (60.7) | 80 396 (49.6) | 0.19 (0.16-0.22) | 0.25 (0.21-0.28) |

| Age groupa | ||||

| 6-11 y | 113 (34.7) | 83 495 (51.5) | 0.11 (0.09-0.14) | 0.14 (0.11-0.16) |

| 12-17 y | 211 (64.7) | 78 564 (48.4) | 0.19 (0.17-0.22) | 0.27 (0.23-0.31) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Anyb | 300 (92.0) | 142 894 (88.2) | 0.16 (0.14-0.18) | 0.21 (0.19-0.24) |

| None | 26 (8.0) | 19 163 (11.8) | 0.11 (0.07-0.15) | 0.14 (0.09-0.20) |

| Asthma and allergyc | 50 (15.3) | 17 885 (11.0) | 0.21 (0.16-0.28) | 0.28 (0.21-0.37) |

| No asthma and allergy | 276 (84.7) | 144 172 (89.0) | 0.15 (0.13-0.17) | 0.19 (0.17-0.22) |

| Psychiatric conditionsd | 58 (17.8) | 20 667 (12.8) | 0.21 (0.16-0.27) | 0.28 (0.21-0.36) |

| No psychiatric conditions | 268 (82.2) | 141 390 (87.2) | 0.15 (0.13-0.16) | 0.19 (0.17-0.21) |

| Diabetese | 2 (0.6) | 762 (0.5) | 0.19 (0.02-0.68) | 0.26 (0.05-1.05) |

| No diabetes | 324 (99.4) | 161 295 (99.5) | 0.15 (0.14-0.17) | 0.20 (0.18-0.22) |

| Acute COVID-19 care level | ||||

| Hospitalizedf | 11 (3.4) | 518 (0.3) | 1.25 (0.62-2.23) | 2.08 (1.10-3.80) |

| Nonhospitalized | 315 (96.6) | 161 539 (99.7) | 0.15 (0.13-0.17) | 0.20 (0.17-0.22) |

| MIS-Cg | 6 (1.8) | 57 (<0.1) | 5.81 (2.13-12.64) | 9.52 (3.93-20.24) |

| No MIS-C | 320 (98.2) | 162 000 (>99.9) | 0.15 (0.14-0.17) | 0.20 (0.18-0.22) |

| Virus varianth | ||||

| Mix of virus variants | 143 (43.9) | 28 982 (17.9) | 0.24 (0.20-0.28) | 0.49 (0.42-0.58) |

| Alpha | 88 (27.0) | 40 192 (24.8) | 0.13 (0.11-0.16) | 0.22 (0.18-0.27) |

| Delta | 48 (14.7) | 26 894 (16.6) | 0.16 (0.12-0.22) | 0.18 (0.13-0.24) |

| Omicron | 47 (14.4) | 65 989 (40.7) | 0.08 (0.06-0.11) | 0.07 (0.05-0.10) |

| Parents’ maximum education | ||||

| Primary school | 8 (2.5) | 6077 (3.7) | 0.10 (0.04-0.19) | 0.13 (0.06-0.27) |

| Secondary school | 84 (25.8) | 38 260 (23.6) | 0.16 (0.13-0.20) | 0.22 (0.18-0.27) |

| Tertiary school | 165 (50.6) | 81 962 (50.6) | 0.15 (0.13-0.18) | 0.20 (0.17-0.24) |

| Unknown | 69 (21.2) | 35 758 (22.1) | 0.15 (0.12-0.20) | 0.19 (0.15-0.25) |

| Any parent diagnosed with PCC | ||||

| Yes | 35 (10.7) | 3401 (2.1) | 0.70 (0.49-0.97) | 1.02 (0.72-1.43) |

| No | 291 (89.3) | 158 656 (97.9) | 0.14 (0.13-0.16) | 0.18 (0.16-0.21) |

Abbreviations: MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; PCC, post–COVID-19 condition.

At study start (January 31, 2020).

Defined as any diagnosis International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code during 2018-2019.

Defined as ICD-10 code J30 or J45 during 2018-2019.

Defined as ICD-10 code F00-F99 during 2018-2019.

Defined as ICD-10 code E10-E14 during 2018-2019.

Including both hospitalization at intensive care units (0 and 40) and regular wards (11 and 478).

Defined as ICD-10 code U10.9. A total of 6 children received both a PCC diagnosis and MIS-C diagnosis, with 4 receiving a PCC diagnosis more than 28 days after MIS-C diagnosis.

Dominant virus variant during the time period when the acute COVID-19 infection occurred.

Discussion

In this population-based, well-powered cohort with uniquely comprehensive data regarding COVID-19 and PCC, only 0.2% children with COVID-19 had a subsequent diagnosis of PCC. Children with PCC were more often girls, older, had comorbidities, had been hospitalized for their COVID-19, or had a parent with a PCC diagnosis. The higher cumulative incidence of PCC among children with a parent with PCC may indicate that the etiology of PCC could involve genetic susceptibility, or that parental experience of long-term symptoms raises awareness of symptoms and facilitates navigation of the health care system. Moreover, the increased occurrence of PCC among hospitalized children is well in accordance with similar results regarding hospitalized adults.6 Because none of the children with PCC had been treated in intensive care, the diagnosis cannot be explained by misclassification of post–intensive care syndrome. The number of MIS-C cases in the study population was low and therefore the association of MIS-C with PCC needs to be evaluated further. A limitation with our study was that the PCC diagnosis code is not yet validated, and the strengths include the unique comprehensive data, the large population-based cohort, and the near-complete follow-up in high-quality registers.

In this descriptive study, PCC in children was rare. We observed a higher number of children with female sex, older age, hospitalization for COVID-19, and having a parent with PCC among cases with PCC.

eMethods.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C, et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adolescents compared with adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):143-156. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.4573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams JY, Oster ME, Godfred-Cato SE, et al. Factors linked to severe outcomes in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in the USA: a retrospective surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(5):323-331. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00050-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Emergency use ICD codes for COVID-19 disease outbreak. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases/emergency-use-icd-codes-for-covid-19-disease-outbreak

- 4.World Health Organization . Updates 3 & 4 in relation to COVID-19 coding in ICD-10. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icd/covid-19/covid-19-coding-updates-3-4-combined.pdf?sfvrsn=39197c91_3

- 5.National Board of Health and Welfare . Statistik om tillstånd efter COVID-19. 2021. Article in Swedish. April 15, 2021. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2021-4-7353.pdf

- 6.Bygdell M, Leach S, Lundberg L, et al. A comprehensive characterization of patients diagnosed with post–COVID-19 condition in Sweden 16 months after the introduction of the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision diagnosis code (U09.9): a population-based cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;126:104-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

Data Sharing Statement