Abstract

Background:

Household air pollution due to the burning of solid fuels is one of the leading risk factors for disease and mortality worldwide, resulting in an estimated three million deaths annually. Peru’s national LPG access program, FISE, aims to reduce the use of biomass fuels and increase access to cleaner fuels for cooking in low-income Peruvian households through public-private partnerships. Perspectives from front-end program implementers are needed to better understand barriers and facilitators to program implementation and to identify strategies to strengthen program reach, uptake, and health impact.

Methods:

We conducted fourteen 30–60-minute, semi-structured interviews with FISE-authorized LPG vendors (also known as agents) in Puno, Peru from November to December of 2019. Questions focused on barriers and facilitators to program enrollment and participation as an LPG agent, and agents’ motivations for participating in the program.

Results:

Overall, agents expressed satisfaction with the FISE program and a willingness to continue participating in the program. Distance from main cities and the homes of program participants, knowledge of FISE and LPG stoves among community members, cell service, and lack of communication with FISE authorities were cited as barriers to implementation and LPG distribution. Agents’ previous experience selling LPG, as well as their social networks and understanding of the health impacts of household air pollution, aided agents in more effectively navigating the system of FISE rules and regulations and in better serving their clients. Many agents were motivated to participate in FISE because they saw it as a service to their community and were willing to find ways to prioritize the needs of beneficiaries.

Conclusion:

The FISE program provides an example of how a large-scale national program can successfully partner with local private enterprises for program implementation. Building upon the strengths of community-based LPG agents, educating community members on the use and benefits of LPG, incentivizing, and supporting delivery services, and improving communication will be key for increasing program utilization and exclusive use of LPG, and improving health outcomes among Peru’s most vulnerable populations.

Keywords: LPG, Biomass fuels, Household air pollution, Clean cooking, Qualitative research, Program implementation, Peru

INTRODUCTION

Household air pollution (HAP) due to the burning of solid fuels (such as wood, coal, crop waste, and dung) is one of the leading risk factors for disease and mortality worldwide, leading to millions of deaths annually (WHO, 2021a). Not only is HAP associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes, but its effects also have substantial impacts on health and gender equity, development, the environment, and climate change (WHO, 2021a). To combat the urgent issue of household energy access and use, efforts have been made globally to expand access to sustainable and scalable sources of clean energy, including solar, electric, biogas, natural gas, alcohol fuels, and liquified petroleum gas (LPG) (WHO, 2022a).

Prior research has documented the barriers and enablers to adoption and sustained use of clean fuel technologies, including LPG, across diverse settings around the globe. These factors act at multiple levels and range from those related to fuel and household characteristics to program and policy mechanisms (Puzzolo, 2016). The relative importance of these factors also depends on the specific context, program mechanism, and clean fuel technology(ies) being implemented. While previous research has examined barriers from the perspectives of households (Puzzolo, 2016; Hollada, 2017; Williams, 2020a), few studies have examined barriers to implementation from the perspectives of front-end implementers, who provide a unique and critical perspective given their proximity to day-to-day operations and position at the interface of end users and higher-level program structures.

The Fondo de Inclusión Social Energético (FISE), or the Fund for Social Inclusion for Energy, is a national targeted LPG subsidy program in Peru that aims to reduce the use of biomass fuels and increase access to clean fuel for cooking in low-income Peruvian households (Pollard, 2018). Through a public-private partnership with LPG distributors and vendors (known as agents), FISE’s LPG access promotion program provides vouchers that low-income households can exchange for discounted LPG fuel. Between 2012 and 2018, FISE reached 1.5 million households and helped create a market for LPG that extends to nearly every district in Peru (Calzada, 2018; Pollard, 2018). While previous studies of the FISE program examined the program’s reach, effectiveness, and health impacts among community beneficiaries (Calzada, 2018; Pollard, 2018), there have been no studies at the time of writing focusing on the perspectives of private LPG agents, who are the front-end implementers of the FISE program.

In this qualitative study, we examined the FISE program through the perspectives of FISE-authorized LPG agents who exchange LPG cylinder vouchers from beneficiaries. The success of the FISE program relies heavily on LPG agents, whose responsibilities include not only providing LPG fuel to beneficiaries, but also exchanging vouchers properly, and training and educating beneficiaries on FISE and LPG usage. LPG agent perspectives can help us understand private agents’ motivations for enrolling and participating in the program and the unique strengths they bring to program implementation (Rosenthal, 2017). These perspectives can provide insight into how an enabling environment created through government policies like subsidies are delivered and reach households. They can also inform strategies for better integrating and building on the strengths of the LPG agents to improve FISE program implementation, and to ultimately promote the program goal of increased LPG access and utilization. The insights generated from this analysis can also be applied to inform the development or adaptation of strategies for voucher programs and LPG subsidies in other settings.

METHODS

Background of Fondo de Inclusión Social Energético (FISE)

The FISE program provides a monthly subsidy voucher to eligible households worth 16 soles (approximately half of a full LPG canister) at the time this study was conducted. Vouchers are attached to beneficiaries’ electricity bills, provided as stand-alone paper vouchers for beneficiaries without electricity, or sent as a digital voucher via SMS for beneficiaries with mobile phones (Pollard, 2018; Calzada, 2018). Local LPG agents supply LPG canisters to beneficiaries and exchange vouchers for reimbursement, which are deposited directly into agents’ bank accounts electronically, from the FISE program. These LPG agents are usually small, local vendors or shop owners. The FISE program is based on a mutually beneficial partnership, where LPG agents can earn extra income by increasing their clientele with FISE beneficiaries, and the FISE program gains a wide network of agents for beneficiaries to access (Pollard, 2018).

Study Setting

In Peru, 5.5 million people were reported to primarily rely on polluting fuels and technologies for cooking in 2019 – leading to 9,716 deaths attributable to HAP in 2016 alone (DHS, 2012; WHO, 2022b). In the short- and medium term, LPG is the clean fuel that can be most feasibly implemented widely in Peru, where LPG is already commonly used, and most of the supply is produced nationally (EIA, 2015; Pollard, 2018).

The Puno Region is in southern Peru on the shores of Lake Titicaca. In 2017, over 47% of the population was living in rural areas, the majority of which are living in poverty (INEI, 2017). In Peru, only 4% of people living in rural areas cook primarily with clean fuels (IEA et al., 2022). A study in 2017 found that approximately 97% of people surveyed in rural Puno cooked with biomass fuel (Pollard, 2018). In 2017, 15% of FISE beneficiaries lived in the Puno region, which is the largest percentage of Peru’s 25 regions (Pollard, 2018). The Puno Region also had the most LPG agents (1,184), followed by Cusco (371) and Cajamarca (347) (Pollard, 2018).

Study Design and Objectives

This case study is a qualitative data analysis of in-depth interviews conducted with FISE-authorized LPG agents in the region of Puno, Peru. The research was conducted in partnership with PRISMA, a Peruvian non-governmental organization with over a decade of experience conducting research in the Puno Region.

The objective of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to LPG agent enrollment in the FISE program and implementation of the voucher exchange process. Lessons learned can be used to enhance the design and implementation of the FISE program, to potentially improve program utilization and associated health impacts in targeted households.

Data Collection and Analysis

Selection of Participants

Our study population consisted of authorized FISE LPG agents actively working in the FISE program in the department of Puno (see location in Figure 1). Our goal was first to identify all FISE agents in the district of Puno. Research staff started with a publicly available list of 244 authorized FISE LPG agents registered on the FISE website (FISE, 2022b). Additional LPG agents that were not included on the registration list were identified through word-of-mouth and snowball sampling from local community members and other LPG agents. After attempting to locate all agents on FISE’s list and using word-of-mouth to find any additional agents who may not have been listed, our research team was able to locate and contact 188 agents to complete an initial survey about agent characteristics. Interview participants were selected from these 188 agents with the goal of gaining as many perspectives as possible and maximizing variation of different characteristics, including geographic location, the size and type of business (small family-run stores vs. larger gas delivery agents), distance from a larger town or city, length of time as a FISE agent, and volume of FISE vouchers exchanged per week. We continued to recruit interview participants until we reached thematic saturation; we stopped recruitment once similar themes emerged from interviews, and little or no new information was being gained from additional interviews (Sandelowski, 1995). Through this process, we arrived at our final sample of 14 interview participants.

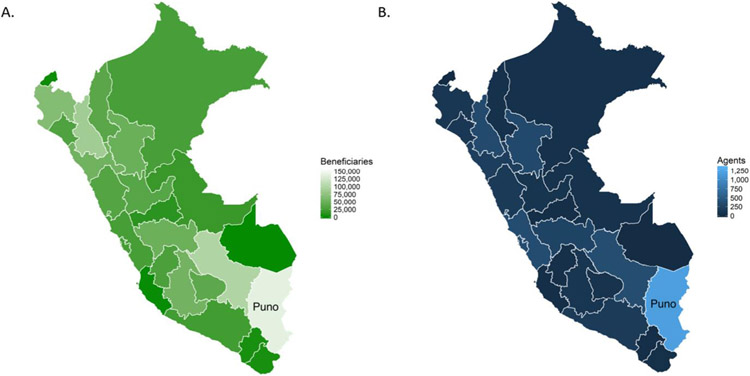

Figure 1. Number of FISE beneficiary households and LPG agents by region.

(a) Number of households participating in the FISE LPG promotion program by region

(b) Number of active, registered LPG agents in October 2017 by region in Peru Pollard, 2018

Interviews

We conducted fourteen in-depth, semi-structured interviews with LPG agents between November and December of 2019. Interviews were conducted in LPG stores or distribution areas to provide a comfortable and familiar environment. Interviews were conducted in Spanish and audio recorded. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed in Spanish. Semi-structured interview questions focused on LPG agent experiences participating in the FISE program and positive aspects and challenges to their participation. Questions also covered the role of FISE in agent businesses; perceptions of the monitoring, supervision and regulations of the program; level of satisfaction and overall perceptions of the program; and areas for improvement (see interview guide, Appendix 1). Through these questions, we attempted to better understand the challenges and facilitators to FISE program implementation for FISE agents, which could in turn impact LPG access and uptake for FISE beneficiaries. All participants provided oral informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Given the fact that no sensitive data or identifying information was collected, this study was acknowledged as exempt from review by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB #00144244) and approved by the Asociación Benéfica PRISMA Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

We primarily used a grounded-theory approach and the constant comparative method for data analysis. We chose this approach to allow for exploration of themes that emerged from the data collected, rather than relying on existing theories or preconceived notions before analysis. This method is ideal for exploratory research, such as ours, where there is limited previous research; in our case, this is one of few studies to directly examine the perspectives of implementers of clean fuel programs.

Three transcripts were selected based on richness for initial coding. These three initial transcripts were coded using inductive techniques that allowed findings to emerge from the data, creating preliminary coding categories. We then categorized concepts into main coding groups. A codebook was then developed based on patterns in the data and recurrent themes, as well as some deductive codes based on research questions and study aims. During second-cycle coding, we used the constant comparative method to move iteratively between codes and transcripts, and to identify additional emerging themes (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Once coded, quotes were synthesized and summarized into key points for each theme.

RESULTS

Out of 244 total agents listed on FISE’s website in the Department of Puno, we were able to contact 188 agents to complete an initial survey on LPG agent characteristics and 14 were selected for in-depth interviews. We selected participants purposively to achieve maximum variation across geographic location, size and type of business, distance from a larger town or city, volume of FISE vouchers processed per week, and length of time as a FISE agent. The 14 interview participants were all active FISE agents from 6 of the 12 districts in Puno (Table 1). Of the 14 agents, 3 were full-time FISE LPG distributors; the rest supplemented LPG distribution with other goods and/or business. While most participating agents estimated that they exchanged 25 vouchers or less per week, three agents reported processing substantially more (45, 90, and 200 vouchers per week). Agents reported being enrolled as FISE agents for less than a year to up to six years. Two agents were not sure or could not remember when they enrolled as FISE agents. Half of the agents interviewed were located on a paved roadway (used as a proxy measure of accessibility), while half were located on dirt roads.

Table 1: LPG Agent Business Characteristics.

Descriptive characteristics for the fourteen LPG agents that participated in semi-structured interviews.

| Characteristic | Number of Agents (% of total) n = 14 |

|---|---|

| District | |

| Acora | 6 (42%) |

| Chucuito | 3 (21%) |

| Coata | 1 (7%) |

| Have | 1 (7%) |

| Pilcuyo | 2 (14%) |

| Puno | 1 (7%) |

| Type of Business | |

| LPG only | 3 (21%) |

| LPG and other goods | 11 (79%) |

| Road Conditions | |

| Asphalt (paved) | 7 (50%) |

| Dirt | 7 (50%) |

| Estimated Vouchers Processed Per Week | |

| 0-10 | 6 (43%) |

| 11-25 | 5 (36%) |

| 26-50 | 1 (7%) |

| 51-99 | 1 (7%) |

| 100+ | 1 (7%) |

| Length of Time as a FISE Agent | |

| 0 - <2 years | 2 (14%) |

| 0 - <4 years | 5 (36%) |

| 4 - <7 years | 5 (36%) |

| Not sure | 2 (14%) |

Several themes emerged from the data, including barriers and facilitators to effective implementation of the FISE program, as well as agent motivations to participate in the program and attitudes toward FISE. Agents also discussed workarounds to circumvent rules and regulations, innovations to support the community and beneficiaries, and ideas to improve the FISE program in the future.

Barriers to Program Implementation

Agents referenced barriers to enrolling as a FISE authorized agent and implementing the FISE program, including challenges to adhering to FISE rules and regulations, processing vouchers, and maintaining enough beneficiaries to support their businesses. While some barriers mentioned by agents coincide with barriers from the perspectives of households in previous literature, agents also provided a unique perspective on barriers to program implementation.

Challenges with Agent Enrollment

Several agents cited barriers to enrolling as a FISE-authorized agent. This included time and travel costs to establish FISE accounts with government offices, opening bank accounts, and setting up cell phone service with mobile providers, all of which are often located far from rural communities. Other barriers agents mentioned were fees and facility requirements. LPG agents are required to pay an annual fee for the authorization to sell LPG, which depends on the amount of LPG cylinders the agent is authorized to sell. FISE also has certain facility requirements, such as appropriate space based on the authorized number of LPG cylinders being stored, proper storage of containers, and sufficient ventilation. Agents also reported needing to have specific safety equipment, such as access to water, fire extinguishers, and a first aid kit. While agents mentioned that it was a challenge to meet the facility and safety requirements due to cost, setup time, and that any misunderstanding of requirements could lead to a suspension of their authorization to exchange FISE vouchers, many also saw the regulations and requirements to enroll in FISE as appropriate and necessary to ensure safety:

“You cannot work without these authorizations, you can't, that is how you get fined, for example by OSINERGMIN, because it is illegal to sell gas tanks [without authorization], which are flammable, dangerous, anything could happen, but if you have protection, someone that is held accountable, then you can work without fear.”

Distance

FISE agents expressed that the distance to main cities and from their store to the homes of program beneficiaries was a barrier to enrollment and program implementation. Many agents in rural areas said that beneficiaries had to travel from far away to exchange their LPG cylinders, which meant that FISE agents spent time, money, and effort to be authorized with FISE, only to serve a small number of FISE beneficiaries who often exchanged vouchers inconsistently. Distance also created difficulties if beneficiaries did not bring proper documentation, such as their ID card, when they came to exchange their vouchers. Beneficiaries living in rural areas often only came to town once a week or less, thus if they could not obtain LPG on that trip, they would need to wait another week to exchange their voucher and receive fuel needed for cooking. Agents also cited distance from main cities as a barrier to attending mandatory FISE trainings or going to FISE offices and businesses to get the proper documentation to enroll as a FISE agent.

Technology and Cell Service

Nearly all FISE agents interviewed said the FISE system of electronic reimbursement for vouchers worked well, and that they appreciated receiving their reimbursements immediately. However, agents that had limited knowledge of technology had a more difficult time navigating the program. Some agents in more rural areas referenced poor cell service as a barrier to gaining access to this technology:

“Since there is no phone service here, since there is no way to communicate, I have to travel a half an hour more or less, grab my motorcycle, and go down and then process it, this is the problem that I have had…”

Poor cell service also made it difficult for agents to receive messages from FISE, such as those about upcoming required trainings.

Beneficiary Enrollment and Retention

A beneficiary’s ability to access the FISE program also influenced agent LPG sales, as beneficiaries typically did not purchase LPG from the agents when they did not receive their vouchers. Agents referenced losing business when beneficiaries were cut from the program, when potential beneficiaries faced difficulties in the enrollment process, or when vouchers were distributed inconsistently. Some agents also referenced beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries not knowing about LPG fuel and its benefits or being afraid to use LPG. From their perspective, the lack of awareness limited the number of households utilizing the FISE program.

Informal Agents

Nearly all agents mentioned other informal agents that found loopholes in the FISE system to exchange vouchers without being officially authorized by FISE. Several agents saw informal agents as hurtful not only for their businesses, but also for the community, since informal agents do not have the required safety training and regulations required by the FISE program.

Agents also reported that beneficiaries often do not understand the rules and regulations of the FISE program and therefore go to unauthorized or informal agents, who are able to sell LPG for less since they do not pay fees or pay the indirect costs of conforming to FISE regulations:

“Other stores also work informally, they collect vouchers, I don’t know where they take them, but the people give them the vouchers. They do not give them a receipt of sale, but the people here ignore that. [Beneficiaries] go where it’s more economical, pay less, one sol, two soles, so… it hurts us…”

Training, Supervision, and Regulations

Agents explained requirements to attend trainings, be present at their store when FISE officials arrived for drop-in supervisory visits, and adhere to various FISE regulations. Despite the indirect costs of time and transportation to attend trainings, many interviewees saw FISE trainings as useful and necessary:

“I would like for them to have [trainings] constantly, constantly because there are new agents that start and they don’t know [what they’re doing] and make mistakes, meanwhile we veteran agents know already how everything is run, so I would like there to be more trainings…”

Another agent shared the need to process vouchers immediately to prevent fraud:

“… we have to process the voucher immediately because there are people with bad intentions, some [beneficiaries] come, their voucher has been processed in another store and they come to us and it surprises us… the RUC [business identification] number is denied when we process [the voucher], that’s how we find out, I tell him, ‘sir your voucher has been processed in another store’, and then he says, ‘no I did not buy gas in that store’, there are people, let’s say, there are vouchers that get lost, [scammers] find the personal identification numbers of the beneficiary and there you go, it is the responsibility of every agent [to watch out for fraud]”

However, several agents expressed frustration with heavy monitoring and penalties from FISE officials, since informal agents appeared to act freely without regulation. In one particularly rural community, with only one agent, the agent reported that he was suspended from FISE for failure to attend a FISE training; however, since he was the only agent in the area, his community was left without anyone to exchange their FISE vouchers for several months.

Some agents expressed feeling a lack of support from FISE. One agent found it difficult to keep up with the demands of the regulations imposed by FISE, while beneficiaries did not understand or follow the rules:

“Authorized agents… right now we see ourselves as isolated… [FISE authorities] demand everything, but the beneficiary does not work with you, the beneficiary does not comply… sometimes they do not know how to exchange vouchers, sometimes they sell [them] …”

Facilitators of Program Implementation

Utilizing Previous Experience and Social Networks

Many agents spoke about their understanding and knowledge of the FISE program — from previous experience as an LPG agent or from connections with LPG distributors or other agents — aiding in their ability to implement the program effectively. Agents expressed how knowledge of the LPG business and previous experience as LPG vendors helped them navigate FISE. Others did not understand the rules and regulations of the program when they first enrolled as FISE agents and were forced to learn how to navigate the program through punishments and suspensions.

For several agents, LPG distributors not only introduced them to the FISE program, but also assisted them in the enrollment process. Agents described that some distributors told them where to go to enroll in FISE or even submitted paperwork on their behalf:

“I did not know about FISE, then [the customers] brought the vouchers, … they brought them to me and I took the vouchers and gave them to this truck, they exchanged them for me, then that truck cheated me… and then an [LPG distributor] helped me, so I told him, 'they cheated me', [the man then said,] 'why don't you become a [FISE] agent?, I will register you', [he said], he registered me and I am currently working with him.”

Understanding Health Impact

Some agents spoke about beneficiaries’ understanding of the health benefits of LPG and FISE’s role in educating beneficiaries so that vouchers would be used as intended. When beneficiaries did not understand these benefits, they were more likely to sell their vouchers or give them to other community members or to their own children living in urban areas, which violated the FISE program rules. As one agent explained:

“…They [beneficiaries] are giving [LPG vouchers] to other people to exchange…How can you improve yourself, and have a healthy life? …Instead you will continue cooking with firewood, and you do your neighbor a favor [by giving them your vouchers]”

Motivations for participating in the FISE program

Many agents viewed their work as an important way to provide for their community and help those in need:

“I am delighted to support in everything… My objective is to serve the community, those in the rural countryside, everyone, because when you see there are elderly people who cannot carry their gas tanks… we make it easy for them.”

Other agents referenced enrolling as a FISE agent primarily for economic and business reasons, but viewed the FISE program overall as a benefit for the community and poor populations.

Agents also expressed a sense of trust between themselves and the people they served, and a sense of pride in doing their work well:

“And now, I am happy with these people… Of course, they call me in the morning… [I tell them], ‘Within half an hour, 40 minutes I will be there’, they wait for me… we support people in this way, people love us.”

Several agents viewed the FISE program as “heaven sent” or a necessary service for the poor. Some not only felt pride in serving their community, but also were uncomfortable with or looked down on other agents who appeared to not care about the community and were only interested in making a profit.

Workarounds and Adaptions to Better Serve Local Communities

Many agents explained implementing several strategies to circumvent rules and regulations to better support their community and FISE beneficiaries. Several agents said that if they knew the beneficiary, they were more lenient on procedures such as checking beneficiaries’ ID cards. One agent said that if beneficiaries had traveled a long distance and did not bring proper documentation, they would exchange the client’s LPG tank with the FISE discount and wait for the client to come back later to process their voucher and be reimbursed by FISE. Another agent explained that sometimes beneficiaries’ vouchers are due to expire, but they had not yet depleted the gas in their current tank. In this case, the agent said they would process the voucher through FISE and give the beneficiary a “credit” to exchange their LPG cylinder later. While some agents offered delivery services, others said they did not officially offer delivery, but they would help beneficiaries transport their LPG cylinder if needed, especially for older beneficiaries unable to carry cylinders.

Many agents also described taking initiative to teach beneficiaries about the benefits of using LPG and how to use LPG safely. While many agents told us that these skills were taught during FISE trainings and FISE encouraged agents to pass this knowledge on to beneficiaries, there was little done to monitor or encourage this transfer of knowledge. Agents described teaching their community voluntarily in order to serve and help others:

“To the consumer, we always give, we guide… when we arrive there, at their house, their home, we have to check to see if it is ok, their hoses [for the LPG stove], their connectors, what dangers they may run into too, what they should do if there is a fire, we have to transmit this knowledge, yes this is for safety…”

DISCUSSION

This study highlighting the experiences and perspectives of front-end implementers of the FISE program identified several barriers and facilitators to successful program implementation. Challenges included agent and beneficiary enrollment and retention, distance of FISE agents from beneficiaries’ homes and larger towns, and the complexity of FISE regulations. The study also describes the facilitators to program implementation, such as FISE agents’ social connections, and motivations for LPG agent participation in the FISE program, such as financial benefits or a desire to serve their community. Implementers’ motivations also revealed potential paths to improving the FISE program through centering community needs and using agents’ social connections to emphasize the health impact and importance of exclusive LPG use. Lastly, this research describes the ways in which front-end implementers adapt to overcome the real-world challenges to the delivery of the program to beneficiaries.

Our results highlight the common barriers that FISE agents and beneficiaries experience. Indeed, agents reported barriers in the enrollment process and challenges conforming to FISE regulations not only for themselves, but also for beneficiaries. Agents stated that the enrollment process for beneficiaries was often long and confusing, and that LPG vouchers for beneficiaries did not arrive regularly. These barriers echo findings from interviews with beneficiaries themselves in previous research, perhaps pointing to the close connection between agents and their communities (Pollard, 2018). Barriers to beneficiary enrollment and retention affect FISE agents, who depend on beneficiary clients to support their business – especially in small, rural communities where agents serve a small population, and many households cannot afford LPG without FISE vouchers.

Our results also showed that distance is a substantial barrier for beneficiaries and LPG agents. Prior research conducted in Puno (Hollada 2017, Pollard 2018) and other settings (Puzzolo, 2016), cite distance as an important barrier for households to achieve adoption and sustained use of clean fuels. Distance is especially a barrier in the rural areas of Puno, where small towns and communities are connected by dirt roads with limited or no public transportation. Most people rely on motorcycles for transportation, or rides from other community members. We found that while distance proves to be a barrier for beneficiaries getting to agents to exchange their LPG cylinders, it is also an important barrier for agents traveling to larger towns to open FISE accounts or attend FISE trainings. While several agents were motivated to provide delivery services to support beneficiaries, others were not able to provide LPG deliveries due to a lack of personnel or transportation. FISE may consider further incentivizing or supporting agents to provide LPG delivery, and decentralizing registration and training facilities. If incentivized by FISE, expanding LPG delivery could be beneficial for both FISE agents and beneficiaries, since delivery services could improve access for beneficiaries and help FISE agents expand their business and clientele. By expanding FISE agent networks, the program could also ensure that even the most remote beneficiaries have program access and less travel over long distances would be required.

Knowledge and experience with the FISE program, and the regulation and supervision of agents also arose as key themes during our interviews with FISE agents. While some agents had a clear understanding of FISE rules and regulations and how to navigate the program, others needed to learn through experience, making mistakes and dealing with suspensions and penalties. The FISE program would benefit from continuing to ensure that rules and regulations align with how implementation occurs on the ground for LPG agents. The few studies that have examined the role of enforcement of standards and regulations in implementation have shown that they play an important role in large-scale promotion of clean fuels (Puzzolo, 2016); however, these standards and regulations should also be written and communicated in an accessible way. Ensuring that agent enrollment and participation be as easy to navigate as possible could incentivize more agents’ participation and fill the gaps currently occupied by ‘informal’ agents that are not officially certified by FISE.

Prior research and case studies highlight the importance of coordination and regular interaction between stakeholders as critical facilitators of uptake (Puzzolo, 2016). Feedback and communication between the FISE program and agents, rather than suspensions, may be more effective in enforcing FISE rules and regulations, which many agents viewed as necessary and important. Suspension of FISE agents not only makes it difficult for small FISE agents to maintain their business, but also leaves beneficiaries without an authorized agent to exchange vouchers. This can lead to beneficiaries’ reliance on informal agents to exchange their FISE vouchers, or for beneficiaries to revert to using biomass fuels. From the perspective of FISE agents, many suspensions and punishments could be avoided through more effective communication between FISE, and agents and beneficiaries. Agents referenced receiving suspensions after not receiving text messages about required trainings, that eligible beneficiaries were often confused about how to enroll in the program, or that beneficiaries have lost their benefits without notice or explanation from FISE. Improved communication within the program is essential to promote trust in the FISE program from both agents and beneficiaries and ensure that the FISE program is adequately addressing community needs.

Study findings also show facilitators to program implementation, including agents’ social connections and networks aiding in their ability to enroll in the program and adhere to FISE rules and regulations. Many agents learned about the FISE program from their social networks — whether it was from their LPG distributor, a previous job, or the people in their community. Leveraging these networks to further spread the word about FISE to other potential agents and beneficiaries, could help further expand the reach of the FISE program.

Agents also referenced having close connections to their local communities. LPG agents, due to their position as both program implementers and members of local communities, can serve as a bridge with the program by building trust and facilitating communication, as has been shown in other cookstove technology programs (Simon, 2010). These agents were motivated to serve their communities, expressed a sense of trust with their clients, and were willing to bend or break FISE rules if they appeared to be detrimental to the people they served. LPG agents’ interviews also highlighted the importance of educating beneficiaries on the benefits of LPG and how to safely use LPG stoves. Community involvement has the potential to create a better sense of ownership and, by extension, more effective programs (O’Mara-Eves, 2015). For the FISE program, educating beneficiaries as well agents and monitoring beneficiaries’ LPG use could dispel fears of the perceived dangers of LPG, ensure that beneficiaries are using LPG properly, and verify that benefits are being utilized by beneficiary households. FISE could utilize these existing social networks between agents and their communities and leverage the knowledge of implementers to better distribute messages about the benefits and safe use of LPG. FISE could consider emphasizing these messages in trainings for FISE agents and encourage or incentivize agents to spread their knowledge about LPG and FISE in their communities.

There were several strengths and limitations to our methods. By using semi-structured interviews, we were able to gain insights into LPG agents’ perspectives based on our initial research questions and were also able to delve into new themes and topics as they arose during each interview. We were also able to adjust our interview guide as we progressed through the interview process to further examine topics of interest. Another strength of our study is that it provides insight into the unique perspectives from FISE LPG agents – highlighting some of the challenges and facilitators to subsidy program implementation. Given their intimate knowledge of the day-to-day operations, front-end implementers are especially well positioned to understand which aspects of a program are successful, as well as potential actionable solutions to ongoing challenges to implementation. An important limitation to this study is that interviews took place in one region of rural Peru (Puno). FISE LPG agents’ experiences may vary in different regions of Peru, especially in urban areas. In addition, the agents who were willing to participate in an interview with researchers from outside their community may be more trusting of outsiders, may be more willing to voice their opinion and critique the FISE program, or may have more positive views of the FISE program. The agents who were willing to participate in our study may have also been more community oriented than other FISE agents, which would influence our results. There are also some limitations to the constant comparative method. Since the interviews were semi-structured, interviews with different agents could lead us in different thematic directions. There is also a large amount of data with limited structure, which can lead to challenges in synthesizing themes.

This study provides insights into the perspectives of authorized agents, but further research on the perspectives of various stakeholders, such as FISE beneficiaries, informal agents, LPG agents who have not enrolled in FISE, and government actors and implementers, as well as comparisons to quantitative geographical data, and work to implement necessary changes in the FISE program, is still needed.

CONCLUSION

Through the FISE program, Peru has created a unique public-private partnership to address the pressing problem of household air pollution. By learning from the perspectives of key, front-end implementers, this study provides insights into how the FISE program can improve the working experience for LPG agents, as well as remove barriers to participation and LPG adoption for FISE beneficiaries. Our results show that the success of the FISE program relies heavily on LPG agents’ role providing LPG fuel to beneficiaries, exchanging vouchers properly, and training and educating beneficiaries on FISE and LPG usage. Previous research has shown that the FISE program has achieved high geographical reach; however, stove stacking continues to be a barrier, in part due to the subsidy’s inability to cover the needs for a household’s exclusive LPG use (Pollard, 2018; Williams, 2020b). By improving the implementation of the FISE program, including leveraging FISE agents’ social connections and their motivations to support their communities, FISE can expand their impact by helping promote exclusive clean fuel use, lowering household air pollution exposure and improving health impacts. Applying these insights and recommendations related to the implementation of voucher programs and LPG subsidies can help further increase access to and exclusive use of LPG not only in Puno, but could also be applied throughout Peru, as well as in other settings.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Distance was a key implementation barrier both for implementers and beneficiaries

The complexity of program enrollment processes and regulations was a barrier

Implementers were motivated by helping their communities

Implementers leveraged social networks for information sharing and building rapport

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Margaret Laws for the essential contributions to the implementation of this project. We also thank Wemilton Vaca and the entire Puno research staff for their contributions to this study. Last but not least, we acknowledge our study participants and Puno community members for their time, consideration, and trust throughout this project.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a K01HL140048 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, US National Institutes of Health (PI: Pollard); the Implementation Science Network of the Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health; the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health; and through the Global Environmental and Occupational Health Hub in Peru funded by the Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health (U01TW010107 and U2RTW010114; MPI: Checkley).

Abbreviations

- DNI

Documento Nacional de Identidad (National Identity Document)

- FISE

Fondo de Inclusión Social Energético

- HAP

Household Air Pollution

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LPG

Liquified Petroleum Gas

- OSINERGMIN

Supervisory Organism of the Investment in Energy and Mining

Appendix 1: LPG Agent Interview Guide

Introduction

- Interviewer introduction

- Good morning / Good afternoon. My name is ________ I am a public health student working with PRISMA, an NGO in Puno. We are conducting a project about the FISE program and the perspectives of LPG agents and program beneficiaries. Would you have time for a conversation with us about your experience as an LPG agent in the FISE program?

- Introduction to project

- Thank you for taking the time to talk with me today. We are interviewing LPG gas distributors participating in the FISE program in Puno to better understand how the FISE program works, your experience with FISE, and how the program can be improved.

- Explanation of interview

- None of these questions have correct or incorrect answers. We want to learn more about your experience as an LPG agent with FISE. If there are any questions that you feel uncomfortable with, you do not have to answer.

- This interview will be completely confidential and voluntary. We will not be collecting your name or other identifiable information. If you feel uncomfortable, we can stop the interview at any time.

- The interview will take about 1 hour. We will be using these audio recorders to record our conversation.

Ice-breaker Questions

- Can you tell us about your business?

- How long have you had this business?

- Do you have other sources of income?

- What is your role in the business?

- What key responsibilities do you have?

- Tell me about who works here at your business.

- How many employees do you have?

- Where are your employees from? The nearby community?

- How far are the homes of your employees from your business?

- How much time does it take your employees to arrive at work?

- What is the role of your employees in your business? What key responsibilities do they have?

Main Questions

Role of FISE in business

- Tell us about your experience participating in the FISE program as an LPG agent.

- What did you do to enroll as a distributor in the FISE program?

- What were the eligibility criteria?

- Why did you decide to participate in the FISE program?

- What motivates you to continue participating as a distributor in the program?

- What has been your experience with the exchange process to receive vouchers from clients?

- What type of vouchers do your clients exchange? (Paper vouchers or through text message?)

- What do you like about the exchange process?

- What do you not like?

- How do you think the process can be improved or changed?

- What has been your experience with the text message-based exchange system to receive vouchers from customers?

- What do you like about the system?

- What do you not like?

- How do you think the process of voucher exchange can be improved or changed?

- What has been your experience with the text message-based exchange system to receive reimbursements of vouchers from FISE?

- What do you like about the system?

- What do you not like about the system?

- How do you think the process of voucher exchange can be improved or changed?

- Tell us how FISE is integrated into your business.

- How dependent is your business on the FISE program?

- What percentage of your customers are FISE beneficiaries?

- Tell us about your customer base.

- Where do most of your customers live?

- How far do your customers have to travel to reach your business?

- How often do your customers come to exchange their gas tanks?

- How are the current LPG distributors covering the LPG needs in this area?

- Is the number of distributors sufficient or not sufficient to cover the needs for LPG in your area? Why / why not?

- Tell us about the services you offer related to LPG.

- Do you offer home delivery as part of your business? Why / why not?

- Do you offer home delivery of gas tanks to FISE beneficiaries? Why / why not?

- How much do you charge to deliver gas to customers' homes?

- Tell us about how you recruit and maintain customers.

- How do your customers know about your business?

- Do you have strategies to recruit new customers or FISE beneficiaries? If so, how? Why / why not?

- Do you have advertisements to promote LPG or FISE? (pamphlets, cards, calendars, etc.)

- Do you have strategies you use to maintain current customers and encourage them to return? If so, how? Why / why not?

Role of government / Electro Puno

What do you think the government's motivation is for having the FISE program?

- How does the government / Electro Puno monitor you as a distributor?

- Tell us about this process.

- How often do you communicate / have contact with Electro Puno?

- What do you and Electro Puno communicate about?

- What support does Electro Puno give you as a distributor?

- What are the main rules or restrictions that the government / Electro Puno requires you to follow?

- How do they enforce these rules?

- What effects do you think this monitoring / rules have on the FISE program?

- How do you think the rules should be changed?

Community Benefits of FISE Program

How important do you think the FISE program is for this community?

- What do you think about the eligibility criteria for households to enroll in the FISE program?

- How do clients enroll in the FISE program?

Program Satisfaction and Improvement

- How satisfied are you with the FISE program?

- What works well?

- What doesn’t work well?

What do you think about the FISE program overall?

What factors have aided in the implementation of the program?

What are the main challenges to being a distributor for the FISE program?

You mentioned previously that [suggestions given about how FISE voucher process and rules/regulations can be changed], are there any other ways you think the FISE program could be improved?

Role of Agents in Monitoring and Reporting

- Have you seen any problems with beneficiaries not following FISE rules? (selling vouchers, giving vouchers to other people, etc.)

- Tell us about this situation.

- What do you do in this situation?

- Do you report problems such as these? To whom? How?

- Have you seen any problems with distributors not following FISE rules and regulations? (accepting two vouchers at once, cashing vouchers without giving a gas tank, etc.)

- Tell us about this situation

- What do you do in this situation?

- Do you report problems such as these? To whom? How?

Closing Questions

Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience as a FISE distributor?

Are there any other questions you have for me?

Closing Remarks

Thank you for your time and sharing your opinions and thoughts about FISE.

Appendix 2: Table of quotes from LPG Agents by theme in English and Spanish

| Theme | Example Quote (Spanish) | Example Quote (English) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers – Challenges to Agent Enrollment | “No se puede trabajar sin esas autorizaciones, no puedes trabajar, ahí vienen las multas, por ejemplo del osinergmin, porque es delito vender balones de gas, que son inflamables, peligros, cualquier cosa que pase, pero si tienes un amparo, alguien que se va a responsabilizar, sin miedo trabajas.” | “You cannot work without these authorizations, you can’t, that is how you get fined, for example by OSINERGMIN, because it is illegal to sell gas tanks [without authorization], which are flammable, dangerous, anything could happen, but if you have protection, someone that is held accountable, then you can work without fear.” | |

| Barriers – Mobile phone service | “Como no hay línea telefónica acá, como no entra ningún medio para comunicarse tengo que recorrer a media hora más o menos, agarrar mi moto, y bajar y luego procesar no, ese problema he tenido yo…” | “Since there is no phone service here, since there is no way to communicate, I have to travel a half an hour more or less, grab my motorcycle, and go down and then process it, this is the problem that I have had…” | |

| Barriers – Informal Agents | “Otras tiendas que vienen también informalmente no, recopilan vales, no sé dónde lo llevarán, pero les dan pe, no les entregan boleta de venta, pero la gente acá ignoran eso, ese es el problema que yo me he ido a quejar también ahí al electro, deben autorizar su boleta de venta pe, entonces no dan, entonces la gente que es lo que ve la gente acá, donde es lo más económico que hay, algo menos, un sol, dos soles, entonces, ahí va pe la gente a comprar, a nosotros nos perjudica, nosotros vamos a sunat todo eso, y la otra gente se beneficia de la nada, incomoda…” | “Other stores also work informally, they collect vouchers, I don’t know where they take them, but the people give them the vouchers. They do not give them a receipt of sale, but the people here ignore that. I have also complained to Electro about this problem, they should authorize their receipts of sale, but they do not give those, so the people what do the people here see? They [beneficiaries] go where it’s more economical, pay less, one sol, two soles, so, that’s where the people go to buy, it hurts us, we are going to SUNAT and all that, and other people benefit from nothing, it’s bothersome…” | |

| Training, Supervision, and Regulations | “Quisiera que hayga constante, constante, porque hay nuevos que aparecen y ellos no saben y cometen errores, en cambio nosotros los antiguos ya sabemos cómo se maneja, entonces yo quisiera que hayga más capacitación…” | “I would like for them to have [trainings] constantly, constantly because there are new agents that start and they don’t know [what they’re doing] and make mistakes, meanwhile we veteran agents know already how everything is run, so I would like there to be more trainings…” | |

| Voucher fraud | “…inmediatamente tenemos que digitar su valecito, porque hay personas con otra intención algunos vienen, su valecito ha sido digitado en otra tienda y nos viene y nos sorprende a nosotros, entonces nosotros lo digitamos y encontramos en que tienda está digitado ese vale. Nosotros en Acora, en dónde sea lo encontramos, decuál tiendas, el número de RUC sale al momento de digitar, en eso lo encontramos, yo le digo, señor tu valecito está digitado en tal tienda, entonces él dice, no he comprado en esa tienda, hay personas digamos, hay vales que se pierden, lo captan y por internet sacan su DNI y van, es la responsabilidad de cada agente…” | “…we have to process the voucher immediately because there are people with bad intentions, some [beneficiaries] come, their voucher has been processed in another store and they come to us and it surprises us… the RUC [business identification] number is denied when we process [the voucher], that’s how we find out, I tell him, ‘sir your voucher has been processed in another store’, and then he says, ‘no I did not buy gas in that store’, there are people, let’s say, there are vouchers that get lost, [scammers] find the personal identification numbers of the beneficiary and there you go, it is the responsibility of every agent [to watch out for fraud]” | |

| Lack of support from FISE | “Hay tantas maneras que tanto beneficiarios, agentes autorizados de electro puno ya trabajan pe en cadena, ahorita nosotros nos vemos como aislados, ya nos vemos aislados no, electro puno nos da, nos exige de todo, pero el beneficiario no te cumple, no te cumple el beneficiario, como decía hace rato, a veces no saben cómo lo canjean, a veces lo venden…” | “Authorized agents of Electro Puno already work in a chain, right now we see ourselves as isolated, we already see ourselves isolated right, Electro Puno [FISE authorities] give us up, demand everything, but the beneficiary does not work with you, the beneficiary does not comply, as I said a while ago, sometimes they do not know how to exchange vouchers, sometimes they sell [them] …” | |

| LPG Distributors | “Yo no entendía de fise, después traían los vales, entonces yo les daba… de un camión que pasaba de otro gas, yo era agente pe, sino me traían acá y yo recibía el vale entregaba ese camión, me lo canjeaban, entonces en ese camión también me ha estafado pe… venía también otro, otro caballero… él también me trajo, señor me atendió, entonces yo le dije al señor yo le conté, me han estafado, mejor por qué no eres agente, te lo inscribo, él me lo ha inscrito, ahorita actualmente con él estoy trabajando…” | “I did not know about FISE, then [the customers] brought the vouchers, … they brought them to me and I took the vouchers and gave them to this truck, they exchanged them for me, then that truck cheated me… and then an [LPG distributor] helped me, so I told him, ‘they cheated me’, [the man then said,] ‘why don’t you become a [FISE] agent?, I will register you’, [he said], he registered me and I am currently working with him.” | |

| The importance of beneficiaries’ understanding health benefits of LPG | “…les estén dando a otras personas que se canjeen no… yo te voy a aceptar normal, porque tengo que negarte no, tú lo canjeas y a la puerta… ‘ahí ta llévate’… o sea en que mejoras tú, para tu vida de salud, tu vida de, tu más te estas enfermándote cocinando, no ha cambiado de nada pe, sigues cocinando con leña, pero a tu vecino le haces el favor…” | “… They [beneficiaries] are giving them [LPG vouchers] to other people to exchange… I am going to accept your business as usual, because I cannot turn you away, you exchange it [the voucher] and at the door…‘there it is take it’, [they say to their neighbor]… How can you improve yourself, and have a healthy life?…your life, you are getting sick from cooking, nothing has changed, …Instead you will continue cooking with firewood, and you do your neighbor a favor [by giving them your vouchers]…” | |

| Motivations – Serving the community | “Encantado yo para apoyar en todo, en todo, mi objetivo es sirvir a la población, a los del campo rural, a todos, porque viéndole hay personas de tercera edad que no se pueden cargar… de tercera edad no pueden cargar, nosotros le hacemos esa facilidad.” | “I am delighted to support in everything, in everything, my objective is to serve the community, those in the rural countryside, everyone, because when you see there are elderly people who cannot carry their gas tanks… the elderly cannot carry them, we make it easy for them.” | |

| Motivations – Support, trust, and pride in serving people | “Y ahora, yo con esa gente estoy feliz, porque no lo hago faltar, claro que me llaman en la mañana cuando estoy solo, sabes mi hermano estoy solo, dentro de media horita, 40 minutos estoy llegando, ellos me esperan… apoyar a la gente, de apoyar a la gente, de cumplir a la gente… nosotros apoyamos de ese lado, nos quiere la gente.” | “And now, I am happy with these people, because I am not wanting, of course they call me in the morning when I am alone, [I tell them], ‘you know my brother I am alone, within half an hour, 40 minutes I will be there’, they wait for me… to support the people, to support people, to fulfill the people… we support people in this way, people love us.” | |

| Improvements and Adaptations – Teaching beneficiaries how to use LPG stoves safely | “O sea consumidor, siempre damos, orientamos, lo que nos dicen allá, cuando llegamos acá, a la casa, a domicilio, tenemos que revisar si está bien, sus mangueras, sus conectores, que peligros corren ellos también, que cosa pueden hacer si en caso hay incendio, tenemos que transmitir eso, sí bastante de seguridad…” | “To the consumer, we always give, we guide, what they tell us there, when we arrive there, at their house, their home, we have to check to see if it is ok, their hoses [for the LPG stove], their connectors, what dangers they may run into too, what they should do if there is a fire, we have to transmit this knowledge, yes this is for safety…” | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Boudewijns E, Trucchi M, Van Der Kleij R, Vermond D, Hoffman C, Chavannes N, Schayck O, Kirenga B, & Brakema E (2022). Facilitators and barriers to the implementation of improved solid fuel cookstoves and clean fuels in low-income and middle-income countries: an umbrella review. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(7):e601–e612 doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00094-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada J, & Sanz A (2018). Universal access to clean cookstoves: Evaluation of a public program in peru. Energy Policy, 118, 559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.03.066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Coding in grounded theory practice. Constructing grounded theory (pp. 42–71). London, UK: Sage Publishing. Retrieved from https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/constructing-grounded-theory/book235960 [Google Scholar]

- Dalaba M, Alirigia R, Mesenbring E, Coffey E, Brown Z, Hannigan M, Wiedinmyer C, Oduro A, Dickinson KL (2018). Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) Supply and Demand for Cooking in Northern Ghana. EcoHealth, 15, 716–728. doi: 10.1007/s10393-018-1351-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demographic and Health Surveys Program (DHS). (2012). Households using solid fuel for cooking, by residence. Retrieved from https://www.statcompiler.com/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Fondo de Inclusión Social Energético (FISE). (2022a). Sobre el FISE. Retrieved from http://www.fise.gob.pe/que-es-fise.html [Google Scholar]

- Fondo de Inclusión Social Energético (FISE). (2022b). Agentes autorizados FISE. Retrieved from http://www.fise.gob.pe/glp4.html [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, & Strauss A (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hollada J, Williams KN, Miele CH, Danz D, Harvey SA, & Checkley W (2017). Perceptions of improved biomass and liquefied petroleum gas stoves in puno, peru: Implications for promoting sustained and exclusive adoption of clean cooking technologies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, WHO. (2022). Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report. World Bank, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2017). Global burden of disease Peru. Retrieved from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica de Peru, (INEI). (2017). Population puno, peru. Retrieved from https://www.citypopulation.de/php/peru-admin.php?adm1id=21 [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S et al. (2015). The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 15(129). 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard SL, Williams KN, O'Brien CJ, Winiker A, Puzzolo E, Kephart JL, … Checkley W (2018). An evaluation of the fondo de inclusión social energético program to promote access to liquefied petroleum gas in peru. Energy for Sustainable Development, 46, 82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzolo E, Pope D, Stanistreet D, Rehfuess EA, & Bruce NG. (2016). Clean fuels for resource-poor settings: A systematic review of barriers and enablers to adoption and sustained use. Environmental Research, 146, 218–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn AK, Bruce N, Puzzolo E, Dickinson K, Sturke R, Jack DW, … Rosenthal JP (2018). An analysis of efforts to scale up clean household energy for cooking around the world. Energy for Sustainable Development, 46, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal J, Balakrishnan K, Bruce N, Chambers D, Graham J, Jack D, … Yadama G (2017). Implementation science to accelerate clean cooking for public health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(1), A3–A7. doi: 10.1289/EHP1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health, 18(2):179–83. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G (2010). Mobilizing cookstoves for development: a dual adoption framework analysis of collaborative technology innovations in Western India. Environ Planning, 42(8):2011–2030. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2015). Peru country analysis. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/PER [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN, Kephart JL, Fandiño-Del-Rio M, Condori L, Koehler K, Moulton LH, Checkley W, Harvey SA, CHAP trial investigators. (August 2020). Beyond cost: Exploring fuel choices and the socio-cultural dynamics of liquiefied petroleum gas stove adoption in Peru. Energy Research & Social Science, 66. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN, Kephart JL, Fandiño-Del-Rio M, O'Brien CJ, Moulton LH, Koehler K, Harvey SA, Checkley W, CHAP trial Investigators. (2020). Use of liquefied petroleum gas in Puno, Peru: Fuel needs under conditions of free fuel and near-exclusive use. Energy for Sustainable Development, 58, 150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank Group & World Bank Open Data. (2018). Peru -- rural population (% of total population). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=PE [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021a). Household air pollution and health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021b). WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022a). Defining clean fuels and technologies. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/tools/clean-household-energy-solutions-toolkit/module-7-defining-clean [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022b). The Global Health Observatory. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/household-air-pollution-attributable-deaths [Google Scholar]