Abstract

The past decade has been characterized by significant changes in the distribution and sale of hearing aids. Alternatives to the clinical technology, clinical channel, clinical service (i.e., traditional) hearing healthcare delivery model have been driven by growth in hearing aid dispensaries housed in large retail establishments and direct-to-consumer hearing aid sales by internet-based companies unaffiliated with major hearing aid manufacturers (e.g., Eargo). These developments have been accompanied by acceleration in the growth of teleaudiology services as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The resulting development of nontraditional hearing aid distribution and sales models can be categorized into distinct archetypes as reviewed earlier in this publication. This article will review the Clinical Technology–Consumer Channel–Clinical Service model as exemplified by Jabra Enhance. We will describe a completely digital model of hearing aid distribution and sales that maintains the professional service component throughout the client journey to include an online tone test, the use of a risk mitigation questionnaire, virtual consultations, remote hearing aid adjustments, and the establishment and monitoring of client-centered treatment goals. Furthermore, this article will review the Jabra Enhance model within the context of consumer healthcare decision-making theory with a focus on the Consumer Decision-Making Model.

Keywords: hearing aids, teleaudiology, online hearing test, Consumer Decision-Making Model

Although hearing aid adoption rates have increased over the past decade, hearing aid uptake continues to remain low relative to those who might benefit from their use. The last MarkeTrak survey estimated that only 34% of adults who self-report hearing difficulties are current hearing aid owners. 1 Several government and scientific agency reviews examined the issue of underutilization of adult hearing healthcare and concluded that issues associated with cost and access represented the two greatest barriers to obtaining adult hearing healthcare in the United States. 2 3 A consistent recommendation among these agencies was to create a classification of hearing aids that could be purchased through conventional retail outlets or online without the need for professional evaluation or prescription—a category of hearing device that is labeled as over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids and codified into U.S. law. The availability of OTCs, coupled with other recent changes in the distribution and sale of hearing aids including online direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales, and the growth of large retail hearing aid dispensaries, have created competitive and innovative options to the traditional Clinical Technology, Clinical Channel, Clinical Service (CiT-CiC-CiS) model of hearing healthcare.

Although several options to the traditional model of hearing healthcare eliminate the need and/or legal requirement for professional involvement, clinical experience and recent research have demonstrated that for many individuals seeking hearing help, the professional component is critical to optimizing success. 4 5 6 For example, in a study that incorporated concept mapping techniques to determine how hearing aid users acquire hearing aid management skills, Bennett and colleagues 4 identified developing a relationship with the clinician , and viewing the clinician as a source of knowledge and support as two major concepts that emerged from their analysis. Several innovative approaches designed to improve hearing healthcare accessibility, while preserving a clinical support component, have been developed in recent years. Examples include Blamey Saunders in Australia ( https://blameysaunders.com.au/ ), Online Hearing Care in the United Kingdom ( https://onlinehearingcare.co.uk/ ), and hearX in Africa ( https://www.hearxgroup.com/ ). In the United States, Jabra Enhance's remote and digital model of hearing healthcare, which represents a Clinical Technology–Consumer Channel–Clinical Service (CiT-CoC-CiS) delivery archetype, is designed to meet the affordability and accessibility challenges identified by the PCAST 2 and NASEM 3 while maintaining a strong and continuous commitment to the professional service component throughout the entire client journey. Given the value hearing aid owners place on professional support and expertise, the Jabra Enhance model was designed to emulate, as closely as possible, the experience a potential client would encounter in a conventional in-person practice. What follows is a description of a CiT-CoC-CiS model of hearing healthcare as exemplified by Jabra Enhance, and a discussion of this model within the larger context of consumer decision-making.

THE JABRA ENHANCE CLIENT JOURNEY

Stage 1—The Online Tone Test

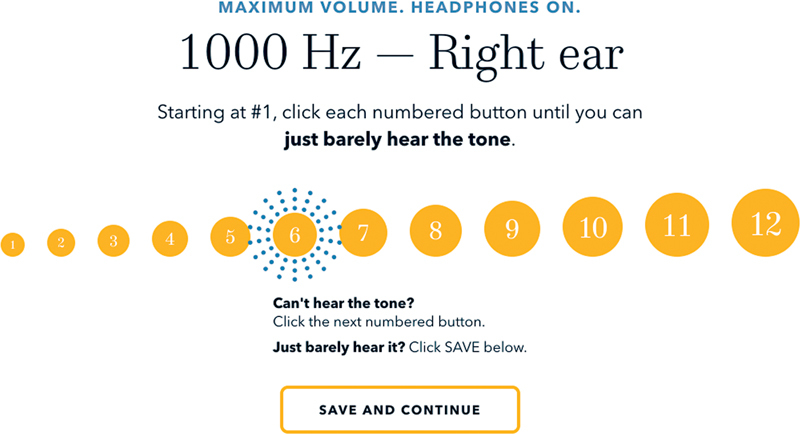

The Jabra Enhance online “tone test” is an adaptation of a previously developed web-based hearing test designed by Stephane Pigeon, a Belgium audio engineer, and can be completed on any device with internet access ( https://hearingtest.online/ ). The Jabra Enhance tone test signals consist of warble tone stimuli centered at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz. Starting at 500 Hz, the individual clicks on a series of numbered icons in ascending order until they hear the tone. Once a selection is “saved,” the test automatically progresses to the next frequency and the threshold search is repeated. A screen shot of a segment of the tone test is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Figure 1.

Screen shot of instructions for responding to the 1,000-Hz stimulus as part of the tone test.

Thresholds are obtained for each ear separately. It is important to note that the Jabra Enhance online test is designed for the purposes of initially programming the hearing aids and not as a diagnostic evaluation for the purposes of identifying hearing or otologic disorders. As part of the test development, Jabra Enhance evaluated the extent to which thresholds obtained via the online test would vary as a function of transducer type, device type (smartphones, laptops, tablets), device volume setting, and type of operating system. After evaluating various combinations of hardware and operating systems, it was found that a 100% volume control level setting resulted in the least variability across devices and transducers.

Prior to the tone test, the user is asked to respond to several questions concerning their perceived degree of hearing difficulties, and the situations in which they experience their greatest difficulties. In preparation for the tone test, the user is instructed to move to a quiet location which is particularly important with commonly used non-occluding transducers. The user is instructed to set the volume of their device to maximum and is given an opportunity to practice the procedure before taking the test. At the completion of the test, the user will see an illustration of the results which are displayed as a “hearing thermometer.” A traditional audiogram is not generated for the client as the results will not be as precise as one obtained using conventional audiometry; however, the hearing thermometer illustration is thought to be easier to understand than the traditional audiometric symbols and values. The hearing thermometer also incorporates descriptors such as “impaired” and “significantly impaired” rather than the more traditional clinical descriptors—“mild,” “moderate,” etc.—again, to differentiate the online tone test from one used for diagnostic purposes. The hearing thermometer is accompanied by a brief video that explains the results to the user based on the specific test results. For example, if the results reveal a mid- to high-frequency impairment, the video content will describe the functional consequences of such impairment in terms of the likelihood of confusing some words for others that contain similar-sounding consonants. It should be noted that the client has the option to upload the results of a recent clinical examination (including an audiogram), in lieu of or in addition to taking the online test.

While the thresholds obtained from online and smartphone-administered hearing tests will not be as accurate as those administered using a calibrated audiometer, research on smartphone-based hearing tests similar to Jabra Enhance's has suggested that their results provide a reasonable estimation of thresholds for those with mild to moderate hearing loss 7 8 9 10 and can effectively identify disabling hearing loss with sensitivity and specificity values of >90%. 10

Stage 2—Risk Identification and Mitigation

DTC and OTC hearing aids have expanded the opportunities for individuals to self-determine the need for hearing healthcare and obtain such care with varying amounts of involvement of a licensed healthcare professional. While improving the accessibility and affordability of hearing healthcare, a potential limitation of remote hearing testing is the inability to perform in-clinic diagnostic tests that could identify a medically modifiable otologic or otoneurologic condition. The Consumer Ear Disease Risk Assessment (CEDRA) can serve as a critical tool for identifying potential risk factors in the emerging DTC landscape. 11 12 13 The CEDRA questionnaire was developed in a collaboration between the Mayo Clinic and Northwestern University to improve accessibility of hearing aids while maintaining reasonable disease surveillance. 12 The motivation behind creating the CEDRA was to add a cost-effective safety layer in the hearing aid acquisition process that would provide confidence to a consumer inclined to sign a medical evaluation waiver. However, the initial conceptualization and development of CEDRA was completed prior to the current diversification of hearing aid dispensing models. A tool such as CEDRA assumes added functionality and importance in these new dispensing models that are envisioned to operate without a licensed professional.

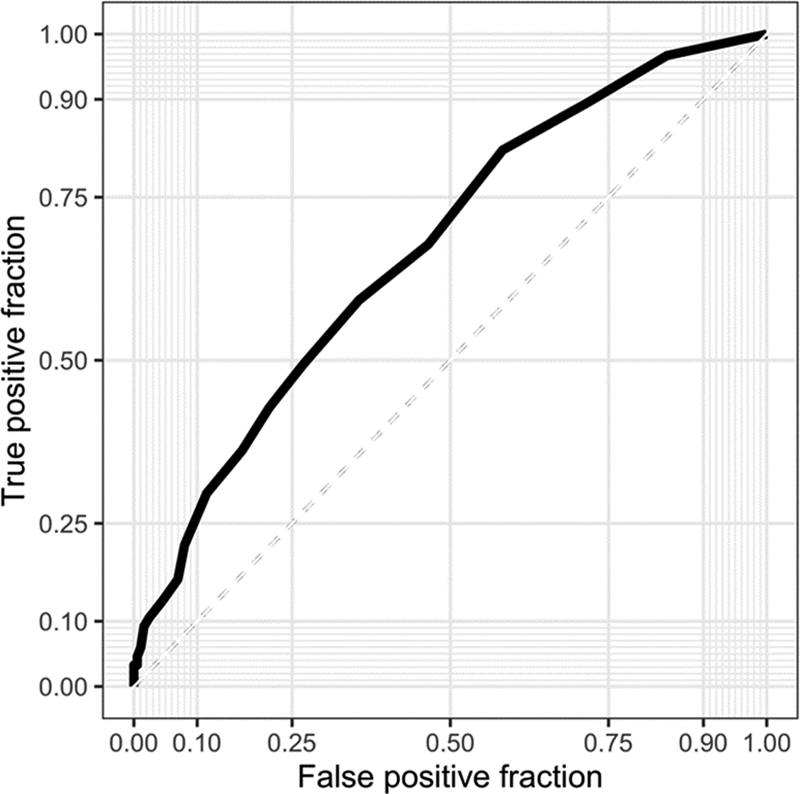

The 15-item CEDRA questionnaire (available in both paper and electronic formats at cedra.northwestern.edu) involves queries about general health status and the status of an individual's hearing and related functions. 13 Scores assigned to each question are then added to arrive at a final risk score. In the original implementation, the developers of CEDRA suggested that a score of 4 or higher may warrant an evaluation by a physician prior to procuring hearing aids. The development of CEDRA started with an accumulation and evaluation of the ear diseases of concern. 11 A preliminary questionnaire developed based on this prioritization was evaluated for usability at the Mayo Clinic, Florida. 12 Based on a training sample of 246 individuals and a test sample of 61 individuals, the initial evaluation demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 94 and 61%, respectively ( Fig. 2 ). 12 After minor modifications based on user feedback, a stable version of CEDRA was evaluated in a multicenter clinical trial at Northwestern University, Evanston; Mayo Clinic, Florida; Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; and the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX. 13 The national trial ( n = 635) demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 68 and 53%, respectively. These values suggest that the CEDRA, as a measure of potential otologic or otoneurologic risk, may benefit from audiologist review. A description of Jabra Enhance's incorporation of the CEDRA into its process follows.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the Consumer Ear Disease Risk Assessment based on an initial training sample of 246 individuals and a test sample of 61 individuals.

The Jabra Enhance CEDRA Classification System

Following completion of the CEDRA, the audiologist a reviews the tone test results along with the automatically calculated CEDRA scores. Depending on the score, the CEDRA is flagged into three possible color-coded categories:

Green: CEDRA point total is below the 4-point referral criterion. Programming and shipping is approved.

Red: CEDRA point total equals or exceeds the 4-point referral criterion triggering consultation with an audiologist and possible referral before hearing aids are programmed and shipped.

Orange: CEDRA point total is below the 4-point referral criterion, but specific responses trigger additional follow-up (e.g., sudden or single-sided hearing loss).

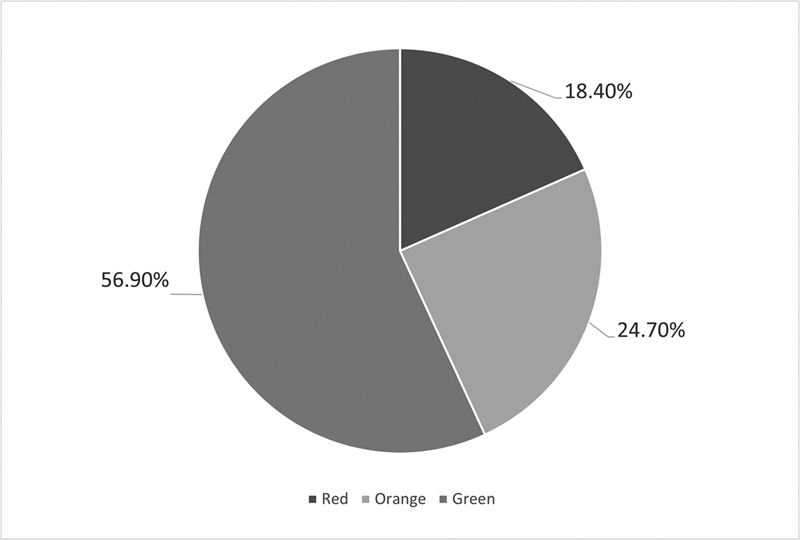

Not all red- or orange-flagged cases are referred for further evaluation. The consultation visit often reveals that the client has been treated or is currently being followed for the condition(s) reported; if not, the audiologist will recommend the client seek further care and will hold the order until the client is cleared for fitting. Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of the green (56.9%), orange (24.7%), and red (18.4%) flags based on the CEDRA score. Over 25% of those CEDRAs that would have defaulted to green (because the total score is below the 4-point referral criterion) are flagged for further review due to a specific CEDRA response (e.g., sudden hearing loss).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Consumer Ear Disease Risk Assessment risk categories based on the Jabra Enhance color classification algorithm. Black segment = red; gray segment = green; light gray segment = orange.

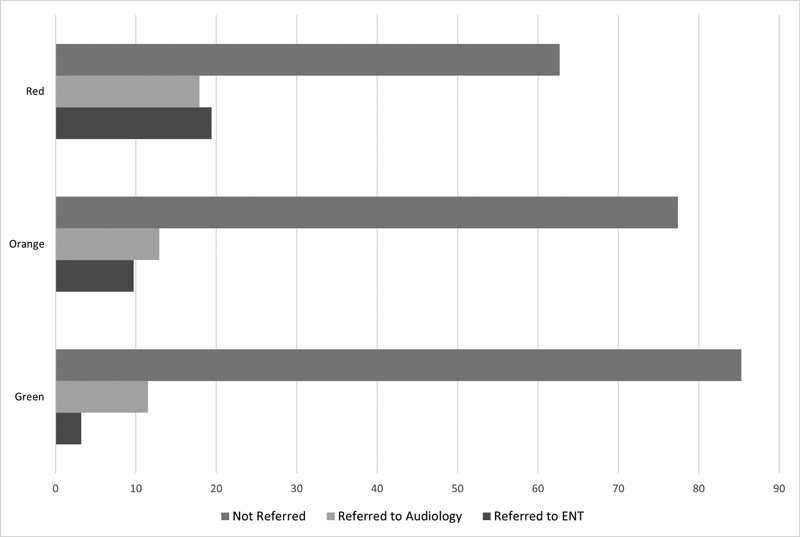

Referrals by Flag Designation

Fig. 4 illustrates the percentage of green-, orange-, and red-classified CEDRAs referred to ENT (black bars), audiology (light gray bars), and not referred to either (gray bars). Green-flagged CEDRAs resulted in the fewest referrals, most of which were referred for further audiologic assessment, whereas red-flagged CEDRAs resulted in the highest number of referrals, most of which were referred to ENT. The reason the data indicate that green-flagged CEDRAs were referred at all is because some of these data were collected prior to the creation of the orange-flagged category. The use of the CEDRA at Jabra Enhance has demonstrated that this risk-mitigation questionnaire, coupled with careful follow-up by an audiologist, has been shown to be an effective tool for identifying individuals at potential risk for otologic and otoneurologic disease and may have an important role to play in an emerging DTC hearing healthcare landscape.

Figure 4.

Percentage of clients with green, orange, and red classified Consumer Ear Disease Risk Assessment scores referred for further audiologic evaluation (light gray), ENT evaluation (black), or not referred to either (gray).

Stage 3—Receipt of Hearing Aids

When the client clears risk review, the devices are programmed to the manufacturer's initial fit parameters based on the results of the online tone test. The client is provided a link to Jabra Enhance's “Get Started Guide” ( https://www.jabraenhance.com/start/enhance-select-200 ) which provides information and step-by-step instructions concerning proper identification of the right and left hearing aid, battery insertion or recharging procedures, cleaning and care, inserting and removing the hearing aids, checking the fit, downloading the Jabra Enhance app, and pairing the hearing aids to the app. The objective of this virtual “on-boarding” process is to ensure that, to the extent possible, all of the technical requirements needed for the initial audiologic consultation have been satisfied to optimize the efficiency and quality of the subsequent initial clinician–client appointment. If, at any point during the virtual “get started” process, the client feels they need assistance, they can request support via email, chat, or a toll-free phone call. Fig. 5 illustrates the percentage of clients who successfully downloaded or completed the necessary applications at the time of the audiology consultation. Approximately 79% of clients completed the CEDRA and downloaded the smartphone app, and ∼75% of clients downloaded the Zoom virtual conference application. As not all clients downloaded all three applications at the time of the orientation, the overall preparedness rate is ∼59%. It is anticipated that periodic upgrades to the Jabra Enhance app will improve the future overall preparedness rate. Even at the current rate of preparedness, the information burden on the client and time burden on the clinician are likely much reduced when compared with a traditional service delivery model.

Figure 5.

Percentage of clients who have successfully completed each of the required downloads at the time of the initial virtual consultation with the audiologist. The preparedness rate represents the percentage of clients who successfully downloaded all required elements.

Stage 4—Audiologic Consultation and Fitting Visit

Virtual appointments are managed through Zoom Video Conferencing, a HIPAA compliant application, which serves as Jabra Enhance's client management platform. At the initial consultation, the assigned audiologist (who remains with the client throughout their care) establishes client-driven treatment goals using the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI). 14 The audiologist checks the physical fit of the hearing aids to include an assessment of the receiver length and dome size, makes any necessary remote modifications to the programming (all of the manufacturer's hearing aid fitting software features can be accessed and implemented remotely by the audiologist), further instructs the client on use and care, and counsels the client regarding adjusting to their hearing aid experience as would typically occur in a traditional service-delivery hearing aid fitting/orientation appointment.

A potential limitation of remote hearing aid fittings is the inability to perform probe-tube verification procedures which are designed to ensure that the prescribed gain and output levels are being satisfactorily achieved relative to a prescriptive target. As noted, Jabra Enhance programs the client's hearing aids using the manufacturer's initial fit algorithm. While there is research supporting the benefits of verified fittings versus initial fit algorithms on patient outcomes, 15 16 recent studies support the effectiveness and equivalency of self-fitting algorithms, compared with probe microphone verification, on speech intelligibility and patient preference. 17 18 19 Emerging innovations such as microphone and receiver in-the-ear technology 20 and automated real-ear measures 21 22 provide the potential for in situ real-ear measures and adjustments that can be performed remotely obviating the need for in-clinic, real-ear verified hearing aid fittings. Furthermore, the incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning into self-fitting algorithms may resolve the current limitation imposed by remote models of care to verify hearing aid performance in the real ear. Indeed, as these algorithms evolve, they may offer opportunities and capabilities that exceed those currently available with a one-time, in-clinic, verification measure.

Stage 5—Follow-up Care

Throughout the first month of hearing aid use, the client is followed as needed to make remote programming modifications to the hearing aids. At ∼14 days post-fitting, the client is scheduled with the audiologist to complete the post-fit COSI and determine the extent to which the goals of treatment have been successfully met as determined by the client. If programming adjustments are required, the audiologist has access to the full suite of programming features which can be implemented remotely. In addition to scheduled appointments, the client has access to no-cost, on-demand care for up to 3 years following purchase of the hearing aids. This on-demand care can be accessed by toll-free phone calls, online support, chat-based assistance, or app-requested services. Approximately 69% of clients contact Jabra Enhance within the first 12 months following purchase with the highest contact rate occurring in the first 3 months. Most clients have two scheduled appointments with a member of the audiology team. The current average number of scheduled follow-up appointments is 1.7, with 64% requiring only one follow-up appointment (which may reflect the number of previous hearing aid users who require little, if any, follow-up care).

SELF-SERVICE CARE

As Jabra Enhance's care is remotely delivered, it is critical to the success of its service-delivery model that as much control as possible is placed into the hands of the client while facilitating access to an audiologist when needed. Much of this control is achieved through the Jabra Enhance-developed app that consists of advanced self-adjustment features, access to the customer and audiology care team to request remote adjustments or to schedule appointments, and access to a growing library of video and interactive articles. Given the nature of the model, a new onboarding experience was designed to provide basic startup instructions prior to initial contact with customer service or a member of the audiology team. Instructions, provided via web and app-based self-guided content, include information as to what is in the box, how to distinguish the right from left hearing aids, how to insert and remove the hearing aids, and how to pair the hearing aids to the app. Once paired with the user's hearing aids, the Jabra Enhance app provides for self-adjustment capabilities across several parameters to include selecting among several environment-specific programs, adjusting overall gain, and selectively modifying gain within broad frequency bands.

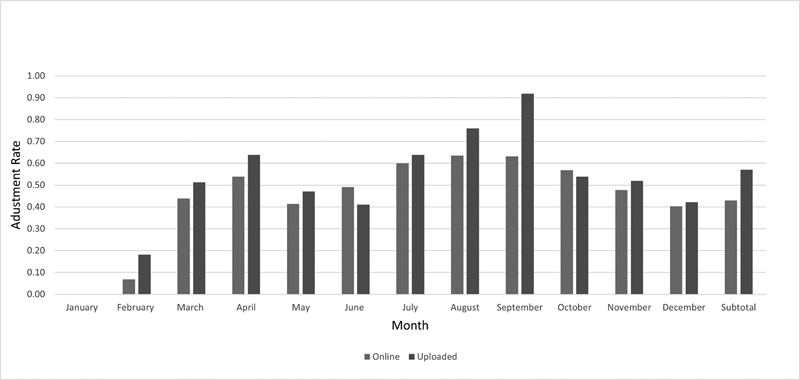

REMOTE CARE

As previously noted, many hearing aid owners value the knowledge and support provided by the audiologist. 4 5 6 The Jabra Enhance app provides an option for clients to request a remote adjustment, book a video consultation, or contact audiology team members via email. The remote adjustment request begins with the client describing their issue by selecting from several possibilities (too loud, muffled, tinny, etc.). After the request is reviewed by the audiologist, a remote modification is made via the fitting software, downloaded to the app, and installed to the hearing aids. The client is given an opportunity to assess the modification(s) and provide feedback regarding their satisfaction with the change. If desired, the client can simply return the hearing aid parameters to its previous settings. Fig. 6 illustrates the total number of remote adjustment requests, through the first 3 months post-fitting, in calendar year 2021. Note that the number of days for each post-fitting segment increases over time. The primary reasons given for the requested adjustments were related to volume, quality of sound, and background noise—not unlike the reasons clients request adjustments in traditional clinical settings. As noted earlier, clients can either take the online tone test or upload a recent audiogram. Fig. 7 illustrates the comparison of the frequency of adjustments between those clients whose hearing aids were programmed on the basis of their online tone test and those whose hearing aids were programmed on the basis of their uploaded audiogram. When collapsed across all reasons for adjustments from February through December 2021, the frequency of adjustments (number of adjustments averaged across all clients over the first 30 days) is generally similar between the two groups, month-to-month throughout the year, although the adjustment rate appears to be somewhat greater, though not likely meaningful, among those clients whose hearing aids were programmed using their uploaded audiogram as reflected in the subtotal. In general, the frequency of adjustment appears to be lower than one would expect (e.g., an average of 0.6 adjustments in the month of July), but this is because these data reflect only the remote adjustment made by Jabra Enhance audiology staff. Adjustments made by the client via their mobile app are not reflected here. The stated reasons for adjustments are similar to what would be expected in a conventional practice and relate to volume, clarity, quality, and background noise issues.

Figure 6.

Total number of remote adjustment requests received through the first 3 months post-fitting, in calendar year 2021. Note that the number of days for each post-fitting segment increases over time (Jabra Enhance).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the month-by-month (February through December 2021) and subtotal hearing aid adjustment rate (the number of requested adjustments averaged across all clients over the first 30 days following fitting) among those whose hearing aids were programmed based on their online test results (light gray) compared with those whose hearing aids were programmed based on an uploaded audiogram (dark gray).

THE JABRA ENHANCE CLIENT

Age distribution : Fig. 8 illustrates the age distribution of Jabra Enhance clients who range in age from 18 to 96 with a peak distribution between the ages of 66 and 72. The data seem to suggest that the Jabra Enhance model attracts individuals across a wide age range who appear to be interested in, and accepting of, a digital model of hearing care.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Jabra Enhance clients as a function of age.

Hearing aid experience : Most clients are first-time hearing aid users (56%) as illustrated in Fig. 9 . According to some experienced users, purchasing an affordable “back-up” pair was an attractive feature, although many reported that their newly purchased Jabra Enhance hearing aids became their primary pair. Jabra Enhance's first-time hearing aid purchase rate is somewhat higher than that reported in MarkeTrak 11, 23 which was 47% for remote-fitted hearing aid and 51% for any hearing aid. Interestingly, of those who purchased a PSAP, 87% reported that it was their first purchase of this type of device.

Figure 9.

Distribution of new and experienced hearing aid users among all Jabra Enhance clients.

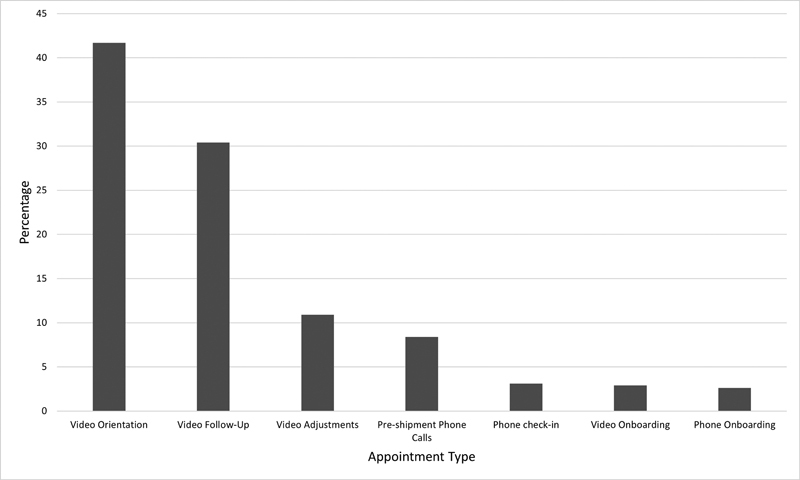

Appointment-type distribution : Fig. 10 illustrates the distribution of virtual appointment types. Approximately 42% of all appointments were for the initial video orientation, followed by a video check-in or follow-up appointment (30%) and video fine-tuning (11%).

Figure 10.

Distribution of all scheduled virtual appointments as a function of the appointment type.

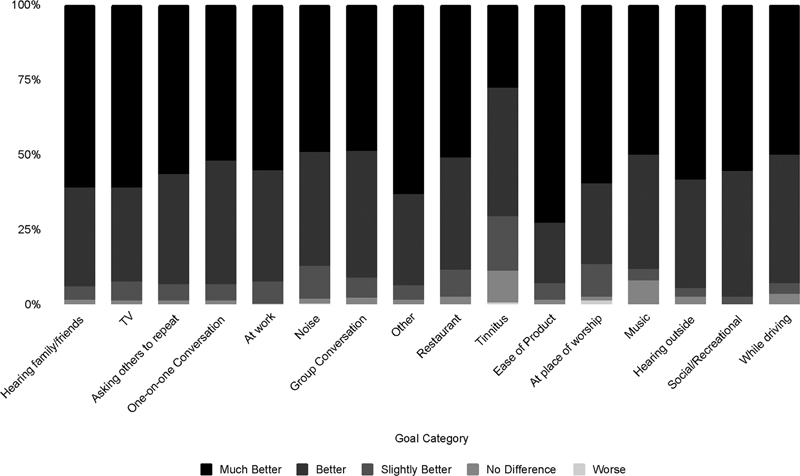

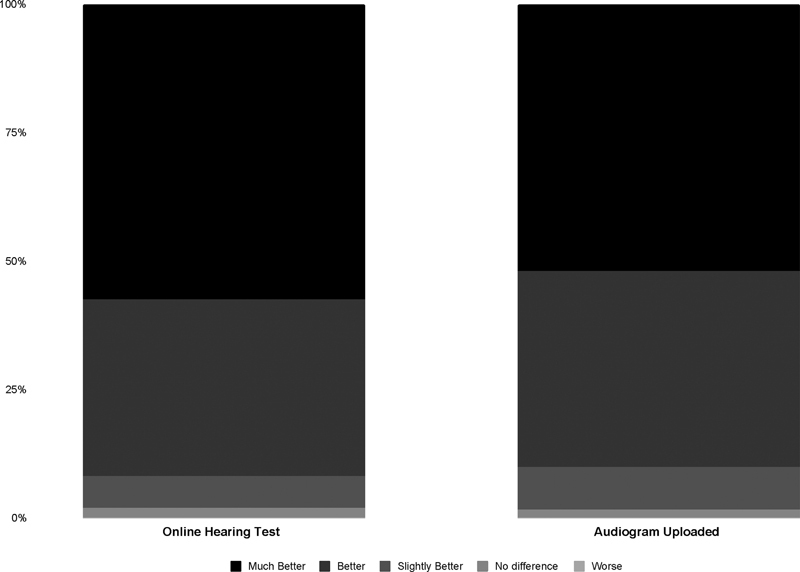

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

As noted, Jabra Enhance establishes pre-fitting, patient-specific treatment goals using the COSI. The extent to which our clients reported positive changes in their hearing and communication abilities 14-day post-fitting across all categories is illustrated in Fig. 11 . The shading of the column segments represents the extent to which the client reported changes in their communication difficulties as a function of their identified problem situation, ranging from worse (very light gray) to much better (black). Clients report significant benefit across all goals including in noisy situations and with tinnitus relief. Averaged across all clients, the degree of reported “better” or “much better” improvement exceeded 95% for most situations. Fig. 12 illustrates a comparison of COSI outcomes between clients who took the online tone test versus those who uploaded their audiograms. The COSI data, averaged across all categories and clients, are equivalent for those whose hearing aids were initially programmed using the online test (illustrated by the left column) versus those whose hearing aids were programmed using their uploaded audiogram (illustrated by the right column).

Figure 11.

Post-fitting Client Oriented Scale of Improvement results as a function of specific problem situations averaged across all clients. The degree of change is represented by the column segment shade ranging from light gray (worse) to much better (black).

Figure 12.

Comparison of post-fitting Client Oriented Scale of Improvement results averaged across all clients and situations as a function of audiogram type. Data for those clients for whom their online hearing test was used to program their hearing aids are shown in the left column; those for whom their uploaded audiogram was used to program their hearing aids are shown in the right column. The degree of change is represented by the column segment shade ranging from light gray (worse) to much better (black).

CLIENT SATISFACTION

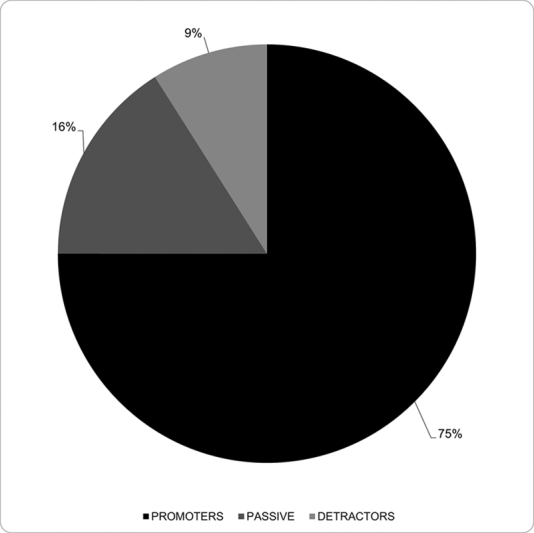

The Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a customer loyalty metric that is widely used across many business types (e.g., healthcare, transportation, technology, food service, and retail) with possible scores ranging from −100 to 100. The NPS measures customers' willingness to not only return for another purchase or service but also their likelihood to make a recommendation to family, friends, or colleagues. The NPS is used as a proxy for estimating the customer's overall satisfaction with a company's product or service as well as the customer's loyalty to the brand. It could be argued that the NPS is a particularly appropriate and valuable measure for alternative hearing care models that focus on consumer priorities such as value, service, and accessibility. Fig. 13 illustrates Jabra Enhance's recent NPS score of 66 (calculated as the percentage of promoters minus detractors) which suggests a very high level of satisfaction with the company's product and services. Jabra Enhance has maintained high NPS scores over the lifetime of the company. By comparison, other recent NPS scores include those of Facebook (−21), Verizon (7), IBM (27), Apple (43), Sony (60), Starbucks (78), and Costco (79). 24

Figure 13.

Distribution of “promoters,” “detractors,” and “passive” respondents that constitute the calculation of Jabra Enhance's NPS score of 66.

THE JABRA ENHANCE MODEL IN THE CONTEXT OF CONSUMER HEALTHCARE DECISION-MAKING

Jabra Enhance's model of hearing healthcare places the patient at the center of the care pathway. This not only empowers the patient to be engaged with their health care decisions but also encourages them to seek out healthcare delivery systems that will meet their specific needs. Consumers report that it is becoming exceedingly more important for their health care providers to offer telehealth digital solutions to improve the accessibility and affordability of healthcare. 25 The recent shift in consumer attitudes and beliefs toward the viability of digital telehealth solutions can be largely attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, McKinsey and Company reported in 2021 that 47% of Americans have had at least one telehealth appointment within the past 2 years, which is up from only 3% in 2019. 26 This finding is one such example of how real-time changes in the healthcare market can play a large role in how patients will choose to seek out healthcare.

How patients will decide which model of hearing healthcare is most appropriate for their needs is largely unexplored (i.e., in person vs. digital). There have been numerous studies investigating reasons why adults with hearing loss choose to (or do not) uptake hearing aids. 27 28 29 30 Many of these studies highlight the complex interplay between psychological and social behaviors, and hearing aid use. See Amlani for a detailed discussion on the influence of psychosocial factors on hearing aid utilization. 35 In fact, general scholarship related to understanding the association between patient psychosocial behaviors and practicing health promoting behaviors has been formalized in health behavior theory. There are several well-established behavior theories that have been applied to audiology, providing frameworks that allow for targeted intervention. However, many of these theories either do not account for or, at a very general level, address potential changes in the healthcare system due to market changes. For example, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), also known as the “Stages of Change Model,” aims to identify a patient's readiness to accept the adoption of a particular health intervention. 31 Four stages of the TTM model are commonly discussed with respect to aural rehabilitation: precontemplation (denial of problem), contemplation (problem awareness but no intention to make a change in behavior), action (active change in addressing problem), and maintenance (sustained healthy behavior). The TTM has been shown in several studies to identify where adults with hearing loss are on the continuum of change for the uptake of hearing aids. 32 33 34 However, the TTM is limited in its explanation of the psychosocial behavioral processes involved with hearing aid acquisition. 35 This is not a shortcoming of the TTM, rather it is a result of the original purpose of the framework which is to conceptualize an individual's motivation toward a desired health behavior.

An alternative model that begins to explore the psychosocial behavioral processes in aural rehabilitation is the Health Belief Model (HBM). 36 The HBM aims to describe and predict whether someone is willing to accept a treatment recommendation for a health condition. The constructs of the HBM include the following: perceived susceptibility (chance of getting the condition), perceived severity (seriousness of condition), perceived benefits (value of adopting health-promoting behavior), perceived barriers (obstacles preventing the adoption of health-promoting behavior), perceived self-efficacy (confidence in taking action), and cues to action (events that trigger the uptake of health-promoting behavior). The application of the HBM in audiology has shown some promise in its ability to predict hearing health behaviors. Specifically, hearing aid users were more likely to experience lower perceived barriers, higher perceived susceptibility, and lower cues to action. 37 38 However, the HBM does not account for an individual's attitudes, beliefs, or intentions that can influence the acceptance of health promoting behaviors. 35 39 It also does not specifically account for the influence of non–health-related factors (i.e., social, economic, environmental, and market) on decision-making.

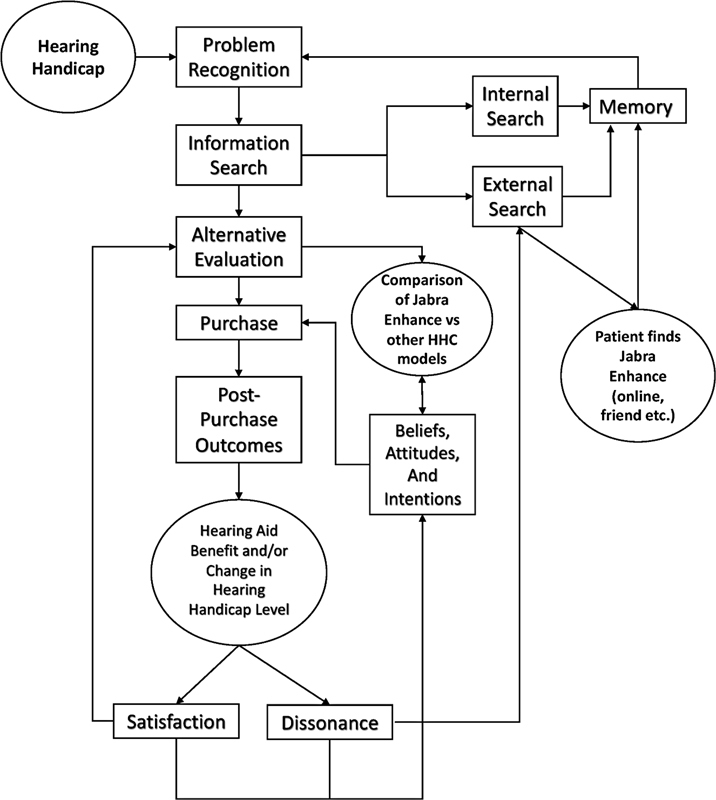

Although we have presented a brief discussion of the limitations of two common health behavior theories, it does still warrant the exploration of alternative models that could provide a more holistic perspective of a patient's individualized hearing healthcare journey. As discussed earlier, market changes in the field are already influencing patient choice for hearing aid acquisition. We would argue that those who choose to pursue hearing healthcare via DTC digital options likely have different internal (e.g., attitudes, motivation) and external (e.g., healthcare systems, societal influences) factors that are driving them to use these nontraditional pathways. One behavior model that could provide us with a framework of the entire hearing healthcare journey is the Consumer Decision-Making Model (CDMM; Fig. 14 ). 40 The CDMM uses a holistic approach to understand consumer decision-making and purchasing behavior. The core of the model consists of a series of five stages: problem recognition (identification of gap between the ideal and current state of things), information search (search for information about potential opportunities both internally and externally), alternative evaluation (assessment of alternative choices to make the best decision), purchase (decision to purchase a product based on their assessment of options), and post-purchase outcomes (satisfaction or dissonance between decision to purchase a product and outcomes). Amlani 35 has already conducted an in-depth analysis of the application of the CDMM to hearing aid adoption for first-time hearing aid users. He argues that given the model's incorporation of both cognitive and psychological processes for consumer buying behavior, the CDMM may provide more predictability of hearing aid adoption compared with other well-known health behavior theories. 35

Figure 14.

Schematic of the Consumer Decision-Making Model (CDMM) in relation to how consumers with hearing loss may choose to pursue hearing healthcare (HHC) via Jabra Enhance. Rectangular nodes indicate a behavioral process in the CDMM, while circular nodes indicate the application to HHC.

Amlani 35 did not directly address the evolving healthcare market (likely due to limited changes in hearing healthcare delivery prior to the passing of the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act in 2017). However, the framework provides an opportunity to better understand how companies like Jabra Enhance are helping adults with hearing loss overcome some of the internal and external challenges of hearing aid adoption. Furthermore, the CDMM can also provide us with a better understanding of patient expectations and outcomes (i.e., satisfaction or dissonance) from their chosen pathway of hearing healthcare. Fig. 14 is an overview of the CDMM with respect to a patient who is considering the Jabra Enhance, or other available online models for hearing healthcare. The decision to purchase hearing aids will begin with an increase in hearing handicap levels (problem recognition) that results in the consumer decision to explore potential options for treatment. This will result in the individual conducting an internal (i.e., previous experience on how to obtain hearing aids) or an external search of potential options for hearing healthcare (information search). The patient will then compare the Jabra Enhance model to other known pathways for hearing healthcare (i.e., accessibility and affordability), which can be influenced by or influence their attitudes, beliefs, and intentions (alternative evaluation). Once they decide to purchase the hearing aid from Jabra Enhance, or their chosen provider, they will go through a hearing aid trial and determine if they receive benefit from their hearing aids (post-purchase outcomes). An evaluation of post-purchase outcomes will be contingent upon their experience with their hearing aids in everyday settings with family, friends, and situations. These interactions and their experiences with the Jabra Enhance model will dictate how satisfied or dissatisfied they are with their hearing aids. Although not shown in our schematic, all of these processes can be influenced by individual, societal, situational, and cultural characteristics.

Our proposal for an alternative framework for hearing healthcare has been echoed outside of the field of audiology. In fact, there has been some preliminary work exploring health care consumer buying behaviors in relation to the CDMM. For example, Gordon et al 41 sought to better understand the health care purchasing process through a consumer lens by conducting semistructured interviews using the CDMM as a structural guide. Results showed that despite the perception that health care purchases are different from other consumer purchases, the behavioral process could still be mapped using the CDMM. 41 Furthermore, the authors argue that market forces do indeed play a role in consumer health care purchase buying behavior. 41

CONCLUSIONS

DTC hearing healthcare will likely experience continued and, perhaps, explosive growth following the release of FDA's final rule on OTC hearing aids. Much of this growth will be characterized by innovative alternatives to the traditional CiT-CiC-CiS hearing healthcare service-delivery process exemplified by such approaches as the Jabra Enhance model whose fully digital and remote model of care has effectively addressed some of the accessibility and affordability challenges of adult hearing healthcare in the United States while, at the same time, preserving the professional component critical to optimizing client success. There are limitations to the CiT-CoC-CiS model described in this article when compared with traditional service delivery, including the inability to perform otoscopy, diagnostic testing, and probe microphone verification measures. These limitations, however, should be weighed against the potential benefits of the CiT-CoC-CiS models in addressing hearing healthcare underutilization. Furthermore, future innovations may not only resolve these limitations, but allow for even better care than is currently provided in traditional practices. As we continue to innovate approaches to hearing healthcare, it is critical for our field to begin the exploration of holistic models, such as the CDMM, that encapsulates the entire hearing healthcare journey. Most importantly, a deeper understanding of a patient's journey even prior to the decision of purchasing a hearing aid will provide greater context for reported outcomes and treatment success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jabra Enhance is a division of GN Consumer Hearing Corporation, dba Jabra Enhance and formerly known, during the historical periods covered in this article, as Lively Hearing Corporation. Portions of this paper were presented at the 2022 American Auditory Society Scientific and Technical Conference, Scottsdale, AZ, February 24 and 25, 2022. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Christina Callahan who reviewed and provided valuable input on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

FUNDING STATEMENT J.S. receives funding from the American Hearing Research Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST H.B.A. is a paid consultant to and holds restricted shares in Jabra Enhance.

J.S. has received consulting fees from GN Resound.

Jabra Enhance also employs hearing aid dispensers, but since it predominantly uses audiologists, we will refer to audiologists throughout.

References

- 1.Powers T A, Rogin C M. MarkeTrak 10: hearing aids in an era of disruption and DTC/OTC devices. Hearing Review. 2019;26(08):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology . Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President; 2015. Aging America & Hearing Loss: Imperative of Improved Hearing Technologies (Letter Report to the President) [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Hearing Health Care for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and AffordabilityWashington, DC The National Academies Press2016 [PubMed]

- 4.Bennett R J, Meyer C J, Eikelboom R H. How do hearing aid owners acquire hearing aid management skills? J Am Acad Audiol. 2019;30(06):516–532. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.17129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett R J, Donaldson S, Kelsall-Foreman I. Addressing emotional and psychological problems associated with hearing loss: perspective of consumer and community representatives. Am J Audiol. 2021;30(04):1130–1138. doi: 10.1044/2021_AJA-21-00093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett R J, Barr C, Cortis A. Audiological approaches to address the psychosocial needs of adults with hearing loss: perceived benefit and likelihood of use. Int J Audiol. 2021;60 02:12–19. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1839680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu-Ghanem S, Handzel O, Ness L, Ben-Artzi-Blima M, Fait-Ghelbendorf K, Himmelfarb M. Smartphone-based audiometric test for screening hearing loss in the elderly. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(02):333–339. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barczik J, Serpanos Y C. Accuracy of smartphone self-hearing test applications across frequencies and earphone styles in adults. Am J Audiol. 2018;27(04):570–580. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-17-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandström J, Swanepoel W, Carel Myburgh H, Laurent C. Smartphone threshold audiometry in underserved primary health-care contexts. Int J Audiol. 2016;55(04):232–238. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1124294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona A P, Ferrite S, Bright T, Polack S. Validity of hearing screening using hearTest smartphone-based audiometry: performance evaluation of different response modes. Int J Audiol. 2020;59(09):666–673. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1731767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleindienst S J, Dhar S, Nielsen D W. Identifying and prioritizing diseases important for detection in adult hearing Health Care. Am J Audiol. 2016;25(03):224–231. doi: 10.1044/2016_AJA-15-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleindienst S J, Zapala D A, Nielsen D W.Development and initial validation of a consumer questionnaire to predict the presence of ear disease JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 201714310983–989.[ Erratum in: JAMA Otolaryngol] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klyn N AM, Kleindienst Robler S, Bogle J. CEDRA: a tool to help consumers assess risk for ear disease. Ear Hear. 2019;40(06):1261–1266. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(01):27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams H B, Chisolm T H, McManus M, McArdle R. Initial-fit approach versus verified prescription: comparing self-perceived hearing aid benefit. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23(10):768–778. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.10.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valente M, Oeding K, Brockmeyer A, Smith S, Kallogjeri D. Differences in word and phoneme recognition in quiet, sentence recognition in noise, and subjective outcomes between manufacturer first-fit and hearing aids programmed to NAL-NL2 using real-ear measures. J Am Acad Audiol. 2018;29(08):706–721. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.17005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boothroyd A, Mackersie C.A “Goldilocks” approach to hearing-aid self-fitting: user interactions Am J Audiol 201726(3S):430–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackersie C, Boothroyd A, Lithgow A. A “goldilocks” approach to hearing aid self-fitting: ear-canal output and speech intelligibility index. Ear Hear. 2019;40(01):107–115. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabin A T, Van Tasell D J, Rabinowitz B, Dhar S. Validation of a self-fitting method for over-the-counter hearing aids. Trends Hear. 2020;24:2.331216519900589E15. doi: 10.1177/2331216519900589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groth J.An innovative RIE with microphone in the ear lets users “hear with their own ears.”Can Audiol 2022;7(5). Accessed April 15, 2022 at:https://canadianaudiologist.ca/resound-feature-2/

- 21.Folkeard P, Pumford J, Abbasalipour P, Willis N, Scollie S. A comparison of automated real-ear and traditional hearing aid fitting methods. Hearing Review. 2018;25(11):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denys S, Latzel M, Francart T, Wouters J. A preliminary investigation into hearing aid fitting based on automated real-ear measurements integrated in the fitting software: test-retest reliability, matching accuracy and perceptual outcomes. Int J Audiol. 2019;58(03):132–140. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2018.1543958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powers T A, Carr K. MarkeTrak 2022: navigating the changing landscape of hearing healthcare. HearRev. 2022;29(05):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Customer Guru Top promotor score benchmarks for top brandsAccessed July 8, 2022 at:https://customer.guru/net-promoter-score/top-brands

- 25.Healthcare consumerism 2018: an update on the journeyMcKinsey & Company. Published July 9, 2018. Accessed April 14, 2022 at:https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/healthcare-consumerism-2018

- 26.How COVID-19 has changed the way US consumers think about healthcareMcKinsey & Company. Published June 4, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2022 at:https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-changed-the-way-us-consumers-think-about-healthcare

- 27.McCormack A, Fortnum H. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? Int J Audiol. 2013;52(05):360–368. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.769066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenstad L, Moon J. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to hearing aid uptake in older adults. Audiology Res. 2011;1(01):e25. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knudsen L V, Oberg M, Nielsen C, Naylor G, Kramer S E. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: a review of the literature. Trends Amplif. 2010;14(03):127–154. doi: 10.1177/1084713810385712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochkin S.MarkeTrak VIII: the efficacy of hearing aids in achieving compensation equity in the workplace Hear J 2010631019–24., 26, 28 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochaska J O, DiClemente C C, Norcross J C. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47(09):1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchaiah V K. Health behavior change in hearing healthcare: a discussion paper. Audiology Res. 2012;2(01):e4. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2012.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laplante-Lévesque A, Hickson L, Worrall L. Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear Hear. 2013;34(04):447–457. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182772c49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laplante-Lévesque A, Brännström K J, Ingo E, Andersson G, Lunner T. Stages of change in adults who have failed an online hearing screening. Ear Hear. 2015;36(01):92–101. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amlani A M. Application of the consumer decision-making model to hearing aid adoption in first-time users. Semin Hear. 2016;37(02):103–119. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1579706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenstock I M, Strecher V J, Becker M H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(02):175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saunders G H, Frederick M T, Silverman S C, Nielsen C, Laplante-Lévesque A.Health behavior theories as predictors of hearing-aid uptake and outcomes Int J Audiol 201655(3, Suppl 3):S59–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders G H, Frederick M T, Silverman S, Papesh M. Application of the health belief model: development of the hearing beliefs questionnaire (HBQ) and its associations with hearing health behaviors. Int J Audiol. 2013;52(08):558–567. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.791030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenstock I M, Kirscht J P. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:470–473. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blackwell R D, Miniard P W, Engel J F. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College; 2001. Consumer Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon D, Ford A, Triedman N, Hart K, Perlis R. Health care consumer shopping behaviors and sentiment: qualitative study. J Particip Med. 2020;12(02):e13924. doi: 10.2196/13924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]