Abstract

Objective:

Given the inequitable impact of COVID-19 on sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth and current sociopolitical racial justice concerns in the U.S., this study examines the impact of SGM-related family rejection and racism since the start of COVID-19 on SGM-related internalized homophobia and identity concealment among SGM college students of color (SOC).

Method:

Participants were a subset of SOC (n=200) from a larger nonprobability cross-sectional study about minority stress and COVID-19 pandemic experiences among SGM college students. Participants completed survey items specifically related to changes in minority stress and racism experiences since the start of COVID-19. Logistic regression models were used to examine the independent and interactive effects of racism and family rejection on identity concealment and internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19 (adjusting for covariates).

Results:

Main effects models revealed that increased racism and family rejection were significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing identity concealment since the start of COVID-19. The interaction of increased racism and family rejection was also significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing identity concealment since the start of COVID-19.

Conclusions:

Study findings suggest that the intersection of racism and family rejection since the start of COVID-19 consequently translates to increased experiences of identity concealment. Such experiences are known to negatively impact mental health across the life course among SGM young people. Public health, medical, mental health, and higher education stakeholders must implement SGM-affirmative and anti-racist practices and interventions to support SGM SOC during COVID-19 and beyond its containment.

Keywords: COVID-19, racism, sexual and gender minority, young adults, minority stress, critical race theory, intersectionality

People of color (POC), socially disadvantaged persons, and young adults are facing severe psychological consequences since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, including elevated rates of anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and suicidal ideation (Czeisler et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). For example, over 40% of young adults in Liu et al.’s (2020) national study of mental health early in the pandemic reported high levels of depression and anxiety. Additionally, sexual and gender minority (SGM) young people are experiencing mental health inequities and disparities compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fish et al., 2021; Kamal et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2021). For instance, Kamal et al. (2021) found that SGM young people reported higher levels of depression, PTSD symptoms, and COVID-19-related worries relative to non-SGM participants. Given that 41% of all young persons in the U.S. are currently enrolled in college, nearly half (45%) of which are POC (Espinosa et al., 2019), and the increased vulnerabilities faced by SGM young persons and POC in the context of the pandemic, it is highly important to understand the identity-related stressors that are affecting the mental health of SGM students of color (SOC) amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

SGM SOC are facing stressful experiences during the time of COVID-19, which are affecting their mental health and wellbeing (Gonzales et al., 2020; Hunt et al., 2021; Salerno, Pease, et al., 2020; Salerno, Shrader, et al., 2021; Scroggs et al., 2020). For instance, SGM SOC may be confined to living circumstances where they face risks for psychological distress (Salerno, Doan, et al., 2021), including family/parental rejection as a result of their SGM identities (Fish, McInroy, et al., 2020; Gonzales et al., 2020; Salerno, Pease, et al., 2020). Family rejection of SGM identities could lead toward increased feelings of internalized homophobia and identity concealment (Brennan et al., 2021; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis et al., 2020; Puckett et al., 2018) and result in mental distress, depression, and suicidal ideation and behavior (Clark et al., 2021; Klein & Golub, 2016; Pachankis et al., 2018). At particular risk are those who were forced to return to their parents homes as a result of changes to university operations and their employment and financial stability during COVID-19 (Conron et al., 2021; The Trevor Project, 2021).

Beyond the context of COVID-19, research has further documented that the dual experiences of racism and SGM-related stressors [(e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) discrimination, gay rejection sensitivity, internalized heterosexism, heterosexist discrimination)] have negative impacts on the mental health of SGM POC, including increases in psychological distress, depression, and anxiety symptoms (English et al., 2018; Sutter & Perrin, 2016; Velez et al., 2019). However, minimal studies have examined the relations between SGM-related family rejection and racism and their impacts on mental wellbeing. Given existing literature linking other forms of SGM-related stress and racism and their impact on mental health, this is an important area of inquiry. Unfortunately, SGM-related family rejection may be compounded by various forms of racism in recent years and during the time COVID-19 (Elias, Ben, Mansouri, and Paradies, 2021), including anti-Black (Bor et al., 2018) and anti-Asian (Tessler et al., 2020) violence and racial discrimination, as well as anti-immigrant discrimination and xenophobia (Garcini, Domenech Rodriguez, Mercado, and Paris, 2020). Therefore, the risk for the dual experience of SGM identity-based family rejection and racism in the context of COVID-19 may place the mental wellbeing (e.g., internalized SGM stress) of SGM SOC in a precarious position.

Current Study

The current study is guided by Minority Stress Theory (Meyer, 2003), which emphasizes the role of externalized (e.g., discriminatory events perpetrated against SGM persons) and internalized (e.g., homophobic feelings related to SGM identities) minority stressors and their impact on mental health among SGM persons. This study also employs ideology borrowed from Critical Race Theory (CRT), a methodological framework that seeks to reveal racist systems of oppression that result in racial health inequities that negatively impact communities of color (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010). Specifically, our study implements CRT by 1) emphasizing focus on populations pushed to the margins and disadvantaged by their lower positions in social hierarchies and striving to elevate their voices and needs (i.e., SGM SOC), 2) considering that racism contributes in a meaningful way to the health problem at hand (i.e., racism interacts with family rejection and impacts internalized homophobia and identity concealment), 3) acknowledging that racism is a central determinant of health inequities for people of color, and 4) acknowledging that racism is not only characterized by blatant and infrequent occurrences (e.g., racial microaggressions are impactful forms of racism; see our study racism scale). Our study is also guided by the intersectionality principle of CRT, which emphasizes that marginalized social identities and processes of oppression are interlocking and produce health and social inequities (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010; Solorzano and Yosso, 2002); in our study, we use intersectionality to understand multiple processes of oppression (i.e., family rejection and racism) among SGM SOC and how they relate to internalized homophobia and identity concealment.

Our study aims to examine the impact of changes in family rejection and racism during COVID-19 on internalized homophobia and identity concealment among SGM SOC. We hypothesize that experiencing family rejection and racism will be associated with greater levels of internalized homophobia and identity concealment since the start of COVID-19. Additionally, we hypothesize that racism will moderate the associations between family rejection and internalized homophobia, and family rejection and identity concealment since the start of COVID-19, such that more experience of racism will lead to a stronger positive association between family rejection and internalized homophobia, and family rejection and identity concealment. The information provided by this study may help to improve policies, practices, and programs to address the identity-related mental health and wellbeing of SGM SOC, particularly in the context of COVID-19 and racism in the U.S.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The data analyzed in this study were derived from nonprobability cross-sectional data collected from a sample of SGM students (N = 565) to explore minority and pandemic stress and mental health among SGM college students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. A subset of racial and ethnic minority students (n = 200) was used for this analysis. Eligibility criteria for the parent study included being at least 18 years of age, identifying as a sexual or gender minority person, and being a full-time, currently enrolled college student. Data were collected between May 27th and August 14th, 2020 via online survey. Participants were incentivized with a raffle for a $50 Amazon gift card. Participants were recruited using an electronic recruitment flyer distributed via multiple social media platforms that included a link to an online Qualtrics survey. Recruitment also occurred through email campaigns within the study implementation team’s internal and external professional networks, and at historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic serving institutions, and LGBTQ student centers across the U.S. University of Maryland institutional Review Board approval and participant informed consent were obtained prior to commencing data collection. Survey duration was approximately 20–25 minutes. Upon completion of the survey, participants were provided with a listing of mental health and crisis management resources and contact information for the study principal investigator.

Measures

Family Rejection

To measure presence of increased frequency of family rejection since the start of COVID-19 among SGM SOC, 10 items from the Sexual Minority Adolescent Sexual Minority Stress Inventory (SMASI; Schrager et al., 2018) and seven items from the Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ; Balsam et al., 2013). To capture increased frequency of family rejection during the COVID-19 pandemic, students were asked to indicate whether they experienced each item more often since the start of the pandemic (0 = no, 1 = yes). The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (α = .893). A composite score was calculated by summing responses across the 17 items (range = 0–17, M = 2.975, SD = .265). Examination of the distribution of the composite score revealed that approximately 35% of the sample did not report an increase in family rejection since the start of the pandemic, and that the distribution was positively skewed; smaller increases in family rejection were more common than moderate or large increases in family rejection. Due to the positive skew of the distribution, scores were dichotomized to reflect no change in family rejection since the start of the pandemic (0) or any increase in family rejection since the start of the pandemic (1).

Racism (perpetrated by white LGBTQ People)

To measure presence of increased frequency of racism since the start of COVID-19 among SGM SOC, 5-items from the LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale (Balsam et al., 2011) were used. To capture increased frequency of racism since the start of COVID-19, students were asked to indicate whether they experienced each item more often since the start of the pandemic (0 = no, 1 = yes). The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (α = .891). A composite score was calculated by summing responses across the items (range = 0–5, M = 1.895, SD = .142). Examination of the distribution revealed that approximately 42% of the sample did not report increases in racism. Among those that did experience increases in racism, the distribution was somewhat platykurtic; while more students reported moderate increases in racism, small or large increases in racism were more commonly reported. As a result of this non-normal distribution, the variable was dichotomized to reflect no change in racism since the start of COVID-19 (0) or any increase in racism since the start of COVID-19 (1).

Identity Concealment

To measure the presence of increased frequency of identity concealment since the start of COVID-19 among SGM SOC, three items from the LGBT Minority Stress Measure (LMSM; Outland, 2016) and four items from the DHEQ (Balsam et al., 2013) were used. To capture increased frequency of identity concealment since the start of COVID-19, students were asked to indicate whether they experienced each item more often since the start of the pandemic (0 = no, 1 = yes). The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (α = .853). A composite score was calculated by summing responses across the seven items (range = 0–7, M = 2.02, SD = .157). Examination of the distribution of composite scores revealed that 42% did not report increases in identity concealment. However, for those that did report increasing concealment, a platykurtic distribution was observed indicating that respondents engaged in low, moderate, and high levels of concealment. As a result of this non-normal distribution, identity concealment scores were dichotomized to reflect no change in identity concealment since the start of the pandemic (0) or any increase in identity concealment since the start of the pandemic (1).

Internalized Homophobia

To measure the presence of increased frequency of internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19, seven items from the LMSM (Outland, 2016) were used. To capture increased frequency of internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19, students were asked to indicate whether they experienced each item more often since the start of the pandemic (0 = no, 1 = yes). The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (α = .879). A composite score was calculated by summing responses across the seven items (range = 0–7, M = 1.06, SD = .134). Examination of the distribution revealed that approximately 63% of the sample did not report increases in internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19. Moreover, when increases were observed, they were likely to be small (positive skew). Thus, scores were dichotomized to reflect no change in internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19 (0) or any increase in internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19 (1).

Covariates

The regression model was adjusted for continuous social isolation (Hughes et al., 2004), parental financial dependence, and age, and dichotomous racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism since the start of COVID-19 (1=yes, 0=no), sex assigned at birth (1=female, 0=male), gender identity (1=non-cisgender identity, 0=cisgender identity), sexual orientation (1=any non-bisexual sexual orientation, 0=bisexual orientation), educational program (1=undergraduate, 0=graduate), Latino ethnicity (1=Latino, 0=not Latino), race (1=any non-white race, 0=white race), living with parents during COVID-19 (1=living with parents, 0=not living with parents), and being out to parents (1=out to parents, 0=not out to parents). See Table 1 for a full list of covariate categories.

Table 1.

Sample Sociodemographic Characteristics (n=200)

| n (%) | Concealment p-value (χ2/t) | Homophobia p-value (χ2/t) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth | .425 | .927 | |

| Female | 143 (72) | ||

| Male | 55 (28) | .242 | .581 |

| Gender Identity | |||

| Cisgender | 141 (71) | ||

| Transgender | 13 (1) | ||

| Non-binary | 25 (13) | ||

| Genderqueer | 11 (6) | ||

| Two-spirit | 2 (1) | ||

| Gender fluid | 3 (2) | ||

| Agender | 5 (3) | ||

| Sexual Orientation | .227 | .703 | |

| Bisexual | 59 (30) | ||

| Gay | 37 (19) | ||

| Lesbian | 31 (16) | ||

| Queer | 33 (17) | ||

| Same-gender loving | 4 (2) | ||

| Pansexual | 15 (8) | ||

| Questioning | 3 (2) | ||

| Non-binary | 1 (1) | ||

| Heterosexual/straight | 1 (1) | ||

| Age [M, (SD)] | 21.70 (3.79) | .022 | 313 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 75 (38) | .658 | .050 |

| Race a | |||

| Asian | 72 (36) | .037 | .032 |

| White | 77 (39) | .557 | 1.00 |

| Black or African American | 52 (26) | .196 | .740 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 7 (4) | .242 | 1.00 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 8 (4) | 1.00 | .262 |

| Another race not listed | 22 (11) | .043 | .706 |

| Nativity: United States-born | 160 (81) | .148 | 1.00 |

| Parental Financial Dependence | .729 | .440 | |

| Not at all financially dependent | 30 (15) | ||

| A little financially dependent | 21 (11) | ||

| Somewhat financially dependent | 31 (16) | ||

| Very much financially dependent | 68 (34) | ||

| Entirely financially dependent | 49 (25) | ||

| Living with Parents | 127 (64) | .656 | .761 |

| Out to Parents | 128 (64) | <.001 | .021 |

| Educational Program: Undergraduate | 148 (74) | .034 | .867 |

| Social Isolation [M, (SD)] | 6.45 (1.74) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Family Rejection | 130 (65) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Racism | 115 (58) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism | 99 (50) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Internalized Homophobia | 73 (37) | <.001 | - |

| Identity Concealment | 115 (58) | - | <.001 |

Total percent in this category will not add up to 100, as participants were instructed to select all that apply

The most common foreign countries of birth were China, Canada, India, Mexico, Philippines, Vietnam, and Puerto Rico. Other countries were in South America, Central America, the Caribbean, and the Middle East

Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism (perpetrated by people of color). To measure the presence of increased racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism since the start of COVID-19 among SGM SOC, 5-items from the LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale (Balsam et al., 2011) were used. To capture increased frequency of racialized hetero/cisgenderism since the start of COVID-19, students were asked to indicate whether they experienced each item more often since the start of the pandemic (0 = no, 1 = yes). The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (α = .772). A composite score was calculated by summing responses across the items (range = 0–5, M = 1.21, SD = .108). Examination of the distribution revealed that approximately 50% of the sample did not report an increase in racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism since the start of COVID-19 and a positive skew; smaller and moderate sized increases in racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism were more common than large increases in racialized heterosexism/cisgenerism. As a result of the positive skew of the distribution, this variable was dichotomized to reflect no change in racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism since the start of the pandemic (0) or any increase in racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism since the start of the pandemic (1).

Data Analysis

First, descriptive analyses were conducted to identify the frequencies and means of racism, family rejection, identity concealment, internalized homophobia, and sociodemographic characteristics. Next a series of Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to examine the bivariate relationships between racism, family rejection, identity concealment, and internalized homophobia. Following, hierarchical logistic regression models were used to examine the effects of racism and family rejection on identity concealment and internalized homophobia since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (after adjusting for study covariates). In the first model, the main effects of racism and family rejection were evaluated. In the second model, we examined the interaction of racism and family rejection to establish whether racism moderated the relationship between family rejection and internalized homophobia, and family rejection and identity concealment since the start of COVID-19. Alpha was set to 0.05 and all analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28.

Demographics

Sample demographics are presented in Table 1. Among SGM SOC in the sample, more than half identified as female (72%) and cisgender (i.e. gender identity that corresponds with sex assigned at birth; 70.5%). Although sexual orientation varied, bisexuality (29.5%) was the most prevalent. The majority of the sample were undergraduate students (74%) born in the U.S. (81%), and average age was 21.71 years (SD = 3.79). A total of 38% identified as Hispanic or Latinx, and a plurality identified white (39%), Asian (36%), Black or African American (26%), or another non-white race (19%). The majority of the sample indicated that they were financially dependent on their parents at some level (85%). Approximately 64% were out to their parents and living with them. The sample average social isolation score was 6.45 (range = 3–9, SD = 1.74). Nearly 60% reported experiencing racism and identity concealment (independently), approximately 50% reported experiencing racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism, over 60% reported experiencing family rejection, and nearly 40% reported experiencing internalized homophobia.

Results

Bivariate relationships between family rejection, identity concealment, internalized homophobia, and racism since the start of COVID-19 are reported in Table 1 and supplemental Table 4. Racism, family rejection, internalized homophobia, and identity concealment were all significantly and positively related to each other.

Impact of Family Rejection and Racism on Identity Concealment and Internalized Homophobia

Identity Concealment

After adjusting for covariates, the main effects model revealed that increased racism [aOR = 3.386, SE = 0.471, CI: (1.344, 8.530), p = .010] and family rejection [aOR = 3.854, SE = 0.442, CI: (1.621, 9.161), p = .002] were significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing identity concealment since the start of COVID-19 (compared to no increase in family rejection and racism). Statistically significant covariates included being out to parents [aOR = 0.185, SE = 0.467, CI: (0.069, 0.493) p < .001], and racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism [aOR = 4.395, SE = 0.467, CI: (1.758, 10.985), p = .002].

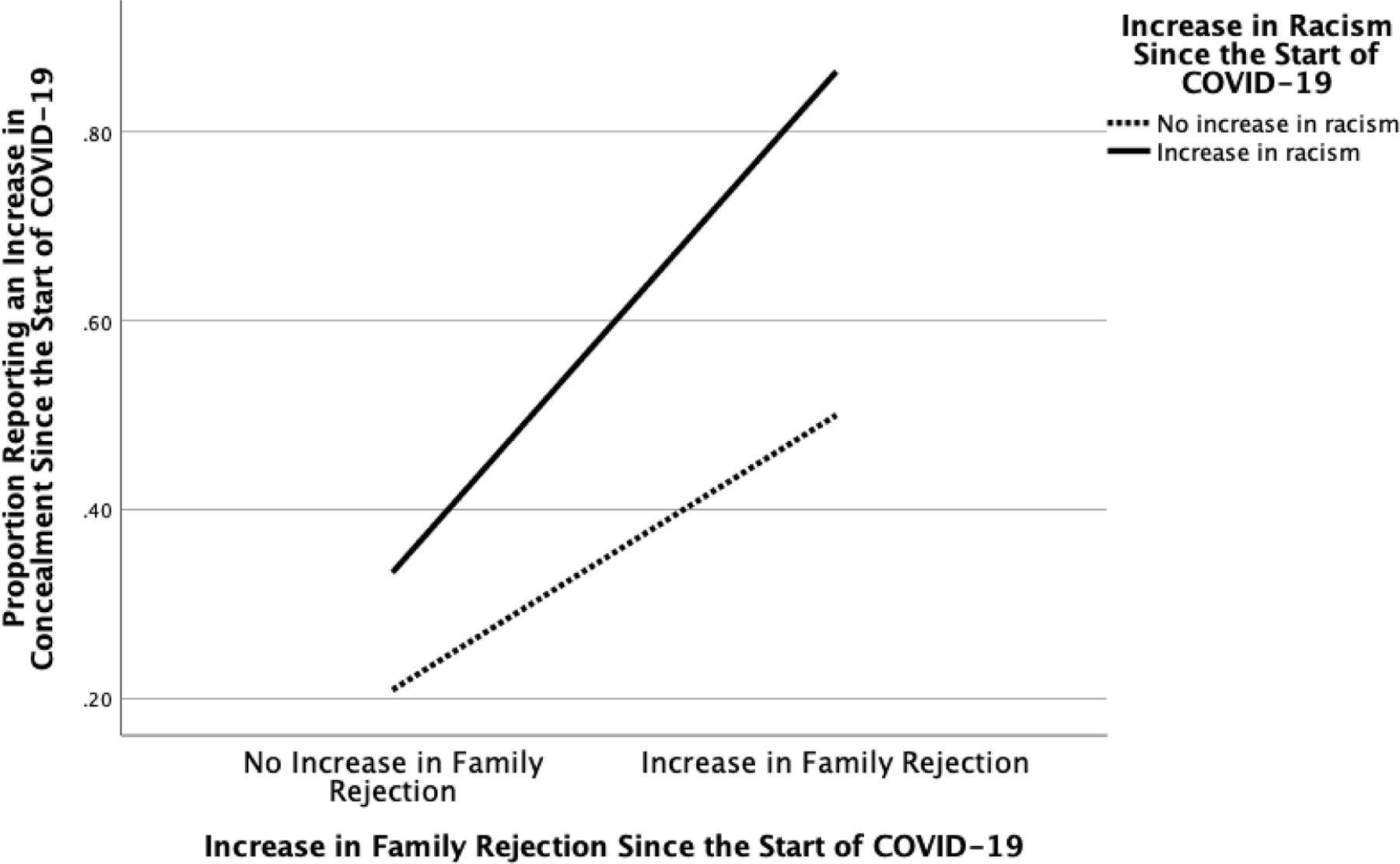

After adjusting for covariates, the interaction of increased racism and increased family rejection was significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing identity concealment since the start of COVID-19 [aOR = 6.888, SE = .948, CI: (1.074, 44.178), p = .042], such that the dual experience of increased family rejection and racism was significantly associated with greater likelihood of experiencing increased LGBTQ-related identity concealment since the start of COVID-19, compared to experiencing either racism or family rejection alone, or none at all. See Table 2 to examine the details of this model, and Figure 1 for a visual representation of the moderation relationship. Statistically significant covariates included being out to parents [aOR = 0.170, SE = 0.516, CI: (0.062, 0.466), p < .001], and racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism [aOR = 4.411, SE = 0.478, CI: (1.728, 11.258), p = .002].

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Model Testing Racism as a Moderator Between Family Rejection and Identity Concealment Since the Start of COVID-19 Among Sexual and Gender Minority College Students of Color (n = 200)

| Variable | B | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racism x Family Rejection | 1.930 | 6.888 | (1.074, 44.178) | .042 |

| Racism | .059 | 1.061 | (.252, 4.474) | .936 |

| No Racism | Ref | |||

| Family Rejection | .417 | 1.518 | (.450, 5.123) | .501 |

| No Family Rejection | Ref | |||

| Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism | 1.484 | 4.411 | (1.728, 11.258) | .002 |

| No Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism | Ref | |||

| Out to Parents | −1.774 | .170 | (.062, .466) | <.001 |

| Not Out to Parents | Ref | |||

| Age (continuous) | −.112 | .894 | (.755, 1.059) | .194 |

| Gay | .268 | 1.307 | (.282, 6.056) | .732 |

| Lesbian | −1.184 | .306 | (.070, 1.338) | .116 |

| Queer | .048 | 1.049 | (.261, 4.222) | .947 |

| Another Sexual Orientation | −.570 | .566 | (.178, 1.801) | .335 |

| Bisexual | Ref | |||

| Asian | −.613 | .542 | (.106, 2.766) | .461 |

| Black | .653 | 1.921 | (.364, 10.124) | .441 |

| Another Race | .781 | 2.183 | (.624, 7.631) | .222 |

| White | Ref | |||

| Latino | .344 | 1.411 | (.293, 6.791) | .667 |

| Non-Latino | Ref | |||

| Noncisgender | −.232 | .793 | (.300, 2.094) | .640 |

| Cisgender | Ref | |||

| Social Isolation (continuous) | .109 | 1.115 | (.868, 1.432) | .393 |

| Living with Parents | .191 | 1.211 | (.371, 3.952) | .751 |

| Not Living With Parents | Ref | |||

| Undergraduate | .295 | 1.344 | (.350, 5.154) | .667 |

| Graduate | Ref | |||

| Parental Financial Dependence (continuous) | −.303 | .739 | (.462, 1.180) | .205 |

| Female Assigned at Birth | .467 | 1.595 | (.439, 5.791) | .478 |

| Male Assigned at Birth | Ref |

Figure 1.

Profile Plot of the Relationships Between Racism and Family Rejection and their Associations with LGBTQ-Related Identity Concealment Since the Start of COVID-19 Among Sexual and Gender Minority College Students of Color (n = 200)

Internalized Homophobia

After adjusting for covariates, the main effects model revealed that increased racism [aOR = 2.460, SE = 0.439, CI: (1.041, 5.812), p = .040] and family rejection [aOR = 2.622, SE = 0.460, CI: (1.065, 6.459), p = .036] were significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19 (compared to no increase in family rejection and racism). Statistically significant covariates included being out to parents [aOR = .350, SE = 0.413, CI: (0.156, 0.788), p = .011], and social isolation [aOR = 1.454, SE = 0.118, CI: (1.154, 1.831), p = .001]. After adjusting for covariates, the interaction of increased racism and family rejection was not significantly associated with greater odds of experiencing internalized homophobia since the start of COVID-19. See Table 3 to examine the details of this model.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Testing Racism and Family Rejection as Predictors of Internalized Homophobia Since the Start of COVID-19 Among Sexual and Gender Minority College Students of Color (n = 200)

| Variable | B | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racism | .900 | 2.460 | (1.041, 5.812) | .040 |

| No Racism | Ref | |||

| Family Rejection | .964 | 2.622 | (1.065, 6.459) | .036 |

| No Family Rejection | Ref | |||

| Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism | .349 | 1.417 | (.608, 3.302) | .419 |

| No Racialized Heterosexism/Cisgenderism | Ref | |||

| Out to Parents | −1.049 | .350 | (.156, .788) | .011 |

| Not Out to Parents | Ref | |||

| Age (continuous) | −.079 | .924 | (.792, 1.078) | .316 |

| Gay | .694 | 2.001 | (.498, 8.037) | .328 |

| Lesbian | −.976 | .377 | (.110, 1.294) | .121 |

| Queer | −.591 | .554 | (.184, 1.669) | .294 |

| Another Sexual Orientation | .946 | 2.575 | (.917, 7.230) | .072 |

| Bisexual | Ref | |||

| Asian | −.744 | .475 | (.113, 2.005) | .311 |

| Black | .140 | 1.150 | (.293, 4.507) | .841 |

| Another Race | −.540 | .583 | (.221, 1.538) | .276 |

| White | Ref | |||

| Latino | .819 | 2.268 | (.606, 8.490) | .224 |

| Non-Latino | Ref | |||

| Noncisgender | .355 | 1.426 | (.637, 3.192) | .388 |

| Cisgender | Ref | |||

| Social Isolation (continuous) | .374 | 1.454 | (1.154, 1.831) | .001 |

| Living with Parents | −.370 | .691 | (.269, 1.775) | .442 |

| Not Living with Parents | Ref | |||

| Undergraduate | −.478 | .620 | (.194, 1.981) | .420 |

| Graduate | Ref | |||

| Parental Financial Dependence (continuous) | −.140 | .870 | (.596, 1.269) | .468 |

| Female Assigned at Birth | .573 | 1.774 | (.564, 5.585) | .327 |

| Male Assigned at Birth | Ref |

Discussion

Our main hypotheses were partially confirmed: SGM SOC that reported increased racism had over 3 times higher odds and those that reported increased family rejection had nearly four times higher odds of experiencing identity concealment compared to those who did not report an increase in these respective experiences since the start of COVID-19. Further, racism significantly moderated the association between family rejection and identity concealment, such that those who experienced an increase in racism evidenced a stronger positive association between family rejection and identity concealment since the start of COVID-19 compared to those who did not report an increase in racism. Lastly, SGM SOC that reported increased racism and family rejection (independently) had more than two times greater odds of experiencing internalized homophobia compared to those who did not experience an increase in these respective stressors since the start of COVID-19.

The main effect models demonstrated evidence for the relationship between increased racism and family rejection with identity concealment among SGM SOC since the start of COVID-19. The relationship between family rejection and identity concealment might be explained by research finding that, for some, identity concealment serves to protect individuals from the externalized stress of SGM identity-related discrimination (Pachankis & Bränström, 2018; Pachankis et al., 2015). In this sample, SGM students living with their parents, especially those who have been sent home from school during COVID may contend with risk for increased family rejection; for them, identity concealment may serve a protective function against family rejection. Recent research indicates that SGM young people consistently living with their parents (before and after the start of COVID-19) and those who moved back home with their parents during the pandemic suffered from greater levels of psychological distress and lower wellbeing compared to those who were living away from their parents (Salerno, Doan, et al., 2021). However, it is not clear whether increased psychological distress and lower wellbeing were related to family rejection and/or identity concealment. Our study findings add useful knowledge and demonstrate that SGM SOC facing increased family rejection since the start of COVID-19 concealed their identities more often (most likely as a coping mechanism to protect against family rejection). This is concerning given the established negative impacts of SGM-related identity concealment on the mental health of SGM young people (Brennan et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2020). In the next paragraph, we outline how racism is relevant in models of family rejection toward identity concealment.

Study results also indicated that racism moderated the association between family rejection and identity concealment. Conceptually, it makes logical sense that SGM SOC would be more likely to hide their SGM identities when they are facing rejection of their SGM identities from their families (i.e., family rejection). Relatedly, SGM SOC facing family rejection may be more likely to conceal their SGM identities when they also experience racism from white LGBTQ people, which is a form of SGM community rejection of their racial identities. Our findings add to previous research that has identified how racism interacts with internalized SGM stress experiences and results in mental health burden (Velez et al., 2019; English et al., 2018). This study is among the first to demonstrate how family rejection (externalized SGM stressor) interacts with racism and consequently leads to increased SGM-related identity concealment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically for SGM SOC. This finding is important given the previous established negative mental health effects of identity concealment (Brennan et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2020) and family rejection (Clark et al., 2021; Klein & Golub, 2016; Pachankis et al., 2018) on SGM young people in general. Study results suggest the important and unique role of racism in models of minority stress and call for more research that seeks to understand and eliminate racism and its negative psychological impacts on the mental health of young SGM POC specifically.

Study findings further provided evidence for the relationship between increased racism and family rejection and increased internalized homophobia among SGM SOC since the start of COVID-19. Conceptually, SGM SOC who are facing rejection of their SGM identities from their families are expected to suffer from greater levels of internalized homophobia. These findings align with existing minority stress literature, which has linked internalized homophobia with parental rejection (Puckett et al., 2014) and negative mental health outcomes (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Puckett et al., 2018) among SGM young people. Our findings add to this literature by highlighting how racism from white LGBTQ people has a unique impact toward internalized homophobia above and beyond family rejection alone, particularly in the context of COVID-19 and specifically among SGM SOC. Similarly, the results of this model call for more research to expand upon our findings and investigate the influential role of racism and its relationships with minority stress factors and mental health among young SGM POC.

Outness was the only statistically significant covariate across all study models, such that being out to parents was associated with a decrease in the odds of experiencing internalized homophobia and identity concealment after adjusting for the experiences of family rejection, racism, and other study covariates. Our findings align with existing research that demonstrates the protective effects of outness toward mental health burden among SGM young people (Kosciw et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2014; Salerno, Shrader, et al., 2020). Additionally, greater social isolation was associated with increased internalized homophobia after adjusting for family rejection, racism, and other study covariates, also aligning with existing research on the negative effects of social isolation on the mental health of SGM people amid COVID-19 (Fish et al., 2021). Lastly, racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism was a statistically significant covariate in main effects and interaction models examining racism and family rejection as independent and interactive predictors of identity concealment, such that racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism was associated with identity concealment since the start of COVID-19. These findings suggests that racialized heterosexism/cisgenderism has a significant impact on identity concealment beyond that of family rejection and racism alone, calling for future investigation of this construct in models of SGM-related minority stress and racism.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although our study has many strengths, there are limitations to consider. For instance, this study used a non-probability and cross-sectional sampling strategy, which limits our ability to generalize findings to broader SGM populations and to make causal assessments. The study also implemented a retrospective self-report data collection strategy, which increases risk for recall and social desirability biases. Sample size limitations further impacted statistical power and may have prevented us from being able to detect a significant interaction between family rejection and racism toward internalized homophobia. In the future, large scale longitudinal studies will be able to conduct similar analyses that address these limitations. Additionally, our study measure of racism perpetrated by white LGBTQ people excludes racism/racial discrimination perpetrated by broader groups, likely making our estimates of racism in this study conservative. Lastly, linear models and quantitative data have potential to misrepresent the realities of SGM POC due to limitations in being able to account for variation across socio-historical-demographic categories and within and between group diversity. Despite these limitations, this study provides important implications regarding the mental health and wellbeing of SGM SOC and young people, in the context of COVID-19 and thereafter.

While the findings of this study shed light on the importance of examining external stressors, such as family rejection and racism on homophobia and identity concealment among SGM SOC, further work is necessary to better understand these complex relationships and their impacts on mental health. Indeed, it is important to examine these constructs longitudinally in order to better understand the mechanistic pathways underlying these relationships, as well as impacts across the different life course stages of SGM POC. Lastly, although existent research reveals that compared to before the pandemic (Dunbar et al., 2017), SGM students are experiencing much greater levels of severe psychological distress during the pandemic (Gonzales et al., 2020; Salerno, Pease, et al., 2020), the specific experiences of SGM SOC remain highly underrepresented. There is a great need for researchers to conduct replication studies with larger samples of SGM SOC related to racism and SGM identity-related stressors.

Implications

Similar to previous studies demonstrating the mental health vulnerabilities of SGM (young) people (Fish et al., 2020, 2021; Kamal et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2021; Salerno, Doan, et al., 2021) and college students (Gonzales et al., 2020; Hunt et al., 2021; Salerno, Pease, et al., 2020; Salerno, Shrader, et al., 2021; Scroggs et al., 2020), the current study supports the salient call for mental health, medical, and higher education practitioners to employ new and appropriate practices and interventions to respond to SGM identity-related concerns amid COVID-19. Given the current study’s specific findings that family rejection and racism independently and interactively associate with internalized homophobia and identity concealment among SGM SOC in the context of COVID-19, there is further an urgent need for mental health, medical, and higher education stakeholders to implement anti-racist (Ford, 2020), intersectionality (Bowleg, 2020), and minority stress (Meyer, 2003) paradigms together in their care of SGM SOC, in the time of COVID-19 and thereafter.

Examples of inclusive and affirming interventions that may help to address SGM-stress experiences and racism (amid and beyond COVID-19) include extending access to racially and culturally sensitive mental health services by increasing visibility of racial allyship (e.g., brown and black stripes on pride rainbows), increasing representation of SGM providers of color, and increasing providers’ skills and self-efficacy toward addressing intersectional (i.e., racial/ethnic and SGM-related) mental health concerns (Huang et al., 2020). It is further imperative for stakeholders to adapt and disseminate resources that promote family acceptance and support, and SGM identity affirmation during the time of COVID-19 (Cohen, Mannarino, Wilson, & Zinny, 2018; Diamond & Shpigel, 2014; Ryan, 2009; SAMHSA, 2014).

Although there is an increasing trend toward addressing gaps in SGM affirmative practice (Phillips et al., 2020; Williams and Fish, 2020), clinical and community practitioners continue to struggle with the application intersectionality (Huang et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2019) and anti-racism (Hassen et al., 2021) paradigms. This is particularly concerning for SGM SOC and POC, who are precariously situated at the intersections of multiple marginalized identities (i.e., sexual, gender, racial, and ethnic minority identities) and processes of oppression (e.g., racism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, and cisgenderism), particularly during the time of COVID-19. Stakeholders are urged to adapt and disseminate existing resources regarding the application of intersectionality (Bowleg, 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2019) and anti-racism (Ford, 2020; Ford et al., 2019; Hassen et al., 2021) in mental health, medical, and higher education settings.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic will result in long-term negative effects to both the physical and mental health of SGM young people of color. For youth experiencing family rejection and racism, this study demonstrates the impact that these external stressors have on identity concealment and internalized homophobia. Practitioners in public health, medicine, mental health, and higher education should utilize these findings toward equitably and adequately supporting SGM youth of color during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond its containment, via the implementation of SGM-affirming and anti-racist practices and interventions.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Impact Statement:

The COVID-19 pandemic will result in long-term negative physical and mental health effects for LGBTQ young people. This study indicates that among LGBTQ young people of color specifically, experiencing LGBTQ-related family rejection and racism leads to more experiences of LGBTQ-related identity concealment, which is known to negatively impact mental health and wellbeing. These findings are important for public health, medical, mental health, and higher education practitioners to know so that they can support LGBTQ youth of color during COVID-19 and beyond its containment, via the use of anti-racist and LGBTQ-affirming practices that promote psychological and physical wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Award Number 1R36MH123043) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the University of Maryland Prevention Research Center Cooperative Agreement Number U48DP006382 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Williams gratefully acknowledges support from the Southern Regional Educational Board and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) Health Policy Research Scholars Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, CDC, or RWJF.

We are grateful to student members of LGBTQ+ Students and Allies in Public Health at the University of Maryland for their commitment to LGBTQ communities and their mental health in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis .

References

- Balsam KF, Beadnell B, & Molina Y (2013). The Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46(1), 3–25. 10.1177/0748175612449743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, & Walters K (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. 10.1037/a0023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2020). We’re Not All in This Together: On COVID-19, Intersectionality, and Structural Inequality. American Journal of Public Health, e1–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, & Tsai AC (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet, 392(10144), 302–310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan JM, Dunham KJ, Bowlen M, Davis K, Ji G, & Cochran BN (2021). Inconcealable: A cognitive–behavioral model of concealment of gender and sexual identity and associations with physical and mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(1), 80. 10.1037/sgd0000424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KA, Dougherty LR, & Pachankis JE (2021). A study of parents of sexual and gender minority children: Linking parental reactions with child mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 10.1037/sgd0000456 [DOI]

- Cohen J, Mannarino A, Wilson K, & Zinny A (2018). Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy LGBTQ Implementation Manual Pittsburg, PA: Allegheny Health. Retrieved from https://familyproject.sfsu.edu/sites/default/files/TF-CBTLGBTImplementationManual_v1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Conron KJ, O’Neill K, & Sears B (2021). COVID-19 and Students in Higher Education: A 2021 Study of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Educational Experiences of LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ U.S. Adults Aged 18–40 Williams Institute, Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBTQ-College-Student-COVID-May-2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, Weaver MD, Robbins R, Facer-Childs ER, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, & Rajaratnam SM (2020). Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69(32), 1049–1057. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, & Shpigel MS (2014). Attachment-based family therapy for lesbian and gay young adults and their persistently nonaccepting parents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 258. 10.1037/a0035394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Sontag-Padilla L, Ramchand R, Seelam R, & Stein BD (2017). Mental health service utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning or queer college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias A, Ben J, Mansouri F, & Paradies Y (2021). Racism and nationalism during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- English D, Rendina HJ, & Parsons JT (2018). The Effects of Intersecting Stigma: A Longitudinal Examination of Minority Stress, Mental Health, and Substance Use among Black, Latino, and Multiracial Gay and Bisexual Men. Psychology Of Violence, 8(6), 669–679. 10.1037/vio0000218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa LL, Turk JM, Taylor M, & Chessman HM (2019). Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Retrieved from https://1xfsu31b52d33idlp13twtos-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Race-and-Ethnicity-in-Higher-Education.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, McInroy LB, Paceley M, Williams N, Henderson S, Levine D, & Edsall R (2020). “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now”: LGBTQ Youths’ Experiences with COVID-19 and the Importance of Online Support. Journal of Adolescent Health 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fish JN, Salerno J, Williams ND, Rinderknecht RG, Drotning KJ, Sayer L, & Doan L (2021). Sexual Minority Disparities in Health and Well-Being as a Consequence of the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ by Sexual Identity. LGBT Health, 8(4), 263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL (2020). Commentary: Addressing Inequities in the Era of COVID-19: The Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Critical Race Theory. Family & Community Health, 43(3), 184–186. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, & Airhihenbuwa CO (2010). The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Social science & medicine, 71(8), 1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, & Gilbert KL (2019). Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional Washington, DC: American Public Health Association Press. American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Garcini LM, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Mercado A, & Paris M (2020). A tale of two crises: The compounded effect of COVID-19 and anti-immigration policy in the United States. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S230–S232. 10.1037/tra0000775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales G, Loret de Mola E, Gavulic KA, McKay T, & Purcell C (2020). Mental Health Needs Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hassen N, Lofters A, Michael S, Mall A, Pinto AD, & Rackal J (2021). Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10.3390/ijerph18062993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2004). A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C, Gibson GC, Vander Horst A, Cleveland KA, Wawrosch C, Granot M, Kuhn T, Woolverton CJ, & Hughes JW (2021). Gender diverse college students exhibit higher psychological distress than male and female peers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity

- Kamal K, Li JJ, Hahm HC, & Liu CH (2021). Psychiatric impacts of the COVID-19 global pandemic on U.S. sexual and gender minority young adults. Psychiatry Research, 299, 113855. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, & Golub SA (2016). Family Rejection as a Predictor of Suicide Attempts and Substance Misuse Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults. LGBT Health, 3(3), 193–199. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, & Kull RM (2015). Reflecting Resiliency: Openness About Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Well-Being and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1–2), 167–178. 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, & Hahm H “Chris.” (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113172. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SE, Wierenga KL, Prince DM, Gillani B, & Mintz LJ (2021). Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived social support, mental health and somatic symptoms in sexual and gender minority populations. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(4), 577–591. 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outland PL (2016). Developing the LGBT minority stress measure. Colorado State University Retrieved from https://mountainscholar.org/handle/10217/176760

- Pachankis JE, & Bränström R (2018). Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(5), 403–415. 10.1037/ccp0000299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, & Mays VM (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 890–901. 10.1037/ccp0000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Mahon CP, Jackson SD, Fetzner BK, & Bränström R (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. 10.1037/bul0000271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Sullivan TJ, & Moore NF (2018). A 7-year longitudinal study of sexual minority young men’s parental relationships and mental health. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(8), 1068–1077. 10.1037/fam0000427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G, Felt D, Ruprecht MM, Wang X, Xu J, Pérez-Bill E, … Beach LB (2020). Addressing the Disproportionate Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Gender Minority Populations in the United States: Actions Toward Equity. LGBT Health [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pitcher EN, Camacho TP, Renn KA, & Woodford MR (2018). Affirming Policies, Programs, and Supportive Services: Using an Organizational Perspective to Understand LGBTQ+ College Student Success. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(2), 117–132. 10.1037/dhe0000048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Mereish EH, Levitt HM, Horne SG, & Hayes-Skelton SA (2018). Internalized heterosexism and psychological distress: The moderating effects of decentering. Stigma and Health, 3(1), 9–15. 10.1037/sah0000065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Woodward EN, Mereish EH, & Pantalone DW (2014). Parental Rejection Following Sexual Orientation Disclosure: Impact on Internalized Homophobia, Social Support, and Mental Health. LGBT Health, 2(3), 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Ryan C, & Diaz RM (2014). Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 635–43. 10.1037/ort0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C (2009). Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children San Francisco: CA: Family Acceptance Project, Marian Wright Edelman Institute, San Francisco State University. [Google Scholar]

- Salerno JP, Devadas J, Pease M, Nketia B, & Fish JN (2020). Sexual and Gender Minority Stress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for LGBTQ Young Persons’ Mental Health and Wellbeing. Public Health Reports, 135(6), 721–727. 10.1177/0033354920954511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno JP, Doan L, Sayer LC, Drotning KJ, Rinderknecht RG, & Fish JN (2021). Changes in Mental Health and Wellbeing Are Associated With Living Arrangements With Parents During COVID-19 Among Sexual Minority Young Persons in the U.S. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 10.1037/sgd0000520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salerno JP, Pease M, Devadas J, Nketia B, & Fish JN (2020). COVID-19-Related Stress Among LGBTQ+ University Students: Results of a U.S. National Survey. University of Maryland Prevention Research Center 10.13016/zug9-xtmi [DOI]

- Salerno JP, Shrader C-H, Algarin AB, Lee J-Y, & Fish JN (2021). Changes in alcohol use since the onset of COVID-19 are associated with psychological distress among sexual and gender minority university students in the U.S. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108594. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2014). A Practitioner’s Resource Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. HHS Publication No. PEP14-LGBTKIDS Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep14-lgbtkids.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schrager SM, Goldbach JT, & Mamey MR (2018). Development of the Sexual Minority Adolescent Stress Inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs B, Love HA, & Torgerson C (2020). COVID-19 and LGBTQ Emerging Adults: Risk in the Face of Social Distancing (in-press). Emerging Adulthood

- Solórzano DG, & Yosso TJ (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter M, & Perrin PB (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessler H, Choi M, & Kao G (2020). The anxiety of being Asian American: Hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 636–646. 10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Trevor Project. (2021). 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health West Hollywood, California: The Trevor Project. Retrieved from: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2021/?section=Covid19 [Google Scholar]

- Velez BL, Polihronakis CJ, Watson LB, & Cox R (2019). Heterosexism, Racism, and the Mental Health of Sexual Minority People of Color. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(1), 129–159. 10.1177/0011000019828309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ND, & Fish JN (2020). The availability of LGBT-specific mental health and substance abuse treatment in the United States. Health Services Research, 55(6), 932–943. 10.1111/1475-6773.13559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford MR, Kulick A, Garvey JC, Sinco BR, & Hong JS (2018). LGBTQ policies and resources on campus and the experiences and psychological well-being of sexual minority college students: Advancing research on structural inclusion. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(4), 445. 10.1037/sgd0000289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.