Summary

Asthma is a heterogeneous chronic respiratory disease that impacts nearly 10% of the population worldwide. While cellular senescence is a normal physiological process, the accumulation of senescent cells is considered a trigger that transforms physiology into the pathophysiology of a tissue/organ. Recent advances have suggested the significance of cellular senescence in asthma. With this review, we focus on the literature regarding the physiology and pathophysiology of cellular senescence and cellular stress responses that link the triggers of asthma to cellular senescence, including telomere shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activation, oxidative-related senescence, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The association of cellular senescence to asthma phenotypes, airway inflammation and remodeling, was also reviewed. Importantly, several approaches targeting cellular senescence, such as senolytics and senomorphics, have emerged as promising strategies for asthma treatment. Therefore, cellular senescence might represent a mechanism in asthma, and the senescence-related molecules and pathways could be targeted for therapeutic benefit.

Keywords: Cellular senescence, Asthma, SASP, Senolytics, Senomorphics

Introduction

Asthma is the most common chronic respiratory disease characterized by a narrow and edematous airway blocked with excessive mucus. It is estimated that more than 300 million people are affected with asthma worldwide, and the prevalence of asthma has continued to increase worldwide.1 Asthma is prevalent not only in childhood but also among older adults, ranging from 4.5% to 12.7%. “Elderly” was defined as the chronological age of 65 years or more. Elderly patients with asthma had an increased prevalence and the highest mortality rate.2 For those elderly patients, significant changes were observed in the innate and adaptive immune responses to environmental exposures associated with an increased chronic systemic inflammation, termed inflammaging, with increased IL-6 and TNF-α.3 A very recent study suggests that elderly patients had worse airway obstruction, more comorbidities, lower levels of IgE and FeNO, elevated Th1 and Th17 inflammation, decreased odds of Th2-profile asthma, and a higher risk for future exacerbations.4 While most patients with asthma have alleviated symptoms after treatment, some patients are still struggling with recurrent symptoms and poor pulmonary function.5 Therefore, a deep understanding of the underlying mechanisms of how age affects immune responses and pathophysiologic changes and exploration of potential therapeutic targets are critical for patients with asthma.

Cellular senescence is a cell status involved in various biological processes, normal aging, and different diseases.6 It is characterized by cellular stress, DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).7 SASP is known to be a product of senescent cells. Recent advances have suggested that cellular senescence may also play a critical role in asthma.8 Increased senescence-related changes have been observed in airway smooth muscle cells of elderly patients with asthma.9 Several significant cellular senescence-related changes have been associated with asthma, including oxidative stress, telomere shortening, autophagy/mitophagy, and inflammation.10 These stimuli and their downstream signaling create an intricate network that causes cell cycle arrest and the release of SASP from asthma-associated target cells. Of interest, several interventions targeting cellular senescence have been suggested as potential therapeutic options for chronic lung diseases.11 Thus, it is likely that exploring the functional role of senescence in the pathogenesis of asthma may lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies, especially for those with severe treatment-resistant asthma. Thus, with this review, we aim to summarize the most advanced information about the physiology and pathophysiology of cellular senescence, and discuss the major hallmarks of cellular stress responses that link to cellular senescence. Moreover, we focus on the literature regarding the recent progress on how cellular senescence affects the major clinical phenotypes of asthma, airway inflammation and remodeling. Importantly, we discuss the translational relevance that targeting cellular senescence by either selectively deleting senescent cells (senolytics) or suppressing SASP (senomorphics) could be a potential therapeutic approach for asthma.

Physiology and pathophysiology of cellular senescence

Cellular senescence is characterized by typical cellular features, including permanent cell cycle arrest, the shift in cellular secretome content SASP, morphological alterations, and resistance to apoptosis, causing the activation of various signaling pathways, including p53, p16/Rb, and p21, as well as cell cycle arrest.7 Several major categories of cellular senescence include replicative senescence, developmentally programmed cellular senescence, and stress-induced premature senescence.12 Of these, replicative senescence is a phenomenon in which cells lose their ability to divide and proliferate after a certain number of cell divisions. Stress-induced premature senescence is a cellular response to various stressors, such as oxidative stress, oncogene expression, DNA damage. In contrast, developmental senescence refers to the normal process of aging that occurs throughout an individual's life. Emerging evidence revealed that cellular senescence could be existing in many different human and animal cell types and participates in numerous biological processes, from normal development or homeostasis to abnormal pathogenic processes.6 For example, stem cell regeneration and differentiation are gradually reduced with increasing chronological age in multiple tissues, which reduces the ability of tissue/organ repairing and leads to increased vulnerability to diseases.13 With aging, immune system function also tends to be clearly decreased, called “immunosenescence”. The immune system gradually loses the capacity to eliminate senescent cells from tissues, thereby contributing to the development of age-related chronic diseases.14 However, there is a clear difference between aging and senescence.7 Aging is a phenomenon that develops progressively with time, but senescence can occur at any stage of life. The difference is further evidenced by the fact that senescence can regulate cell homeostasis or tissue growth at any stage of mammalian life. Cellular senescence has also been shown to be a modulating mechanism that contributes to tumor suppression, wound healing, and embryogenesis.15

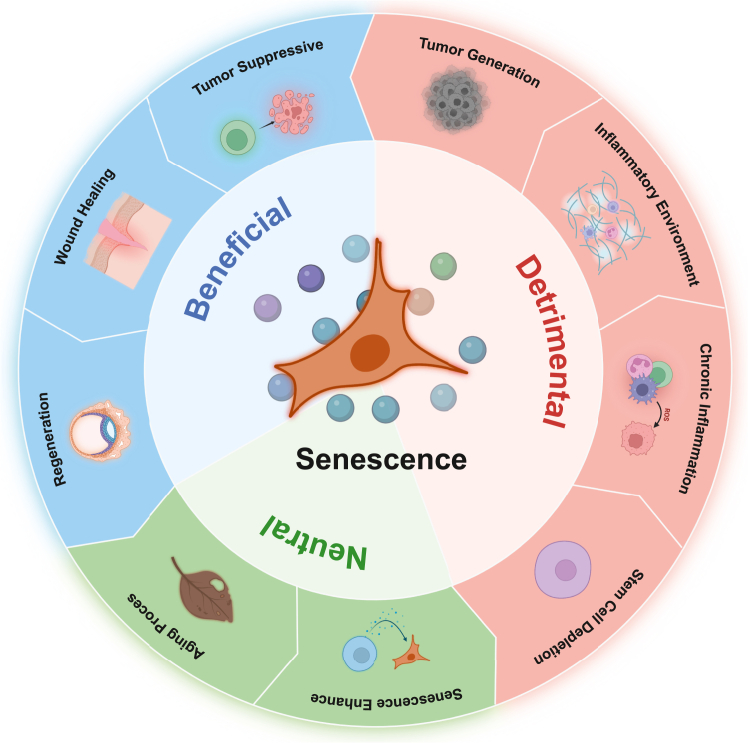

In contrast to its functional significance in physiological processes, recent advances have suggested a pathophysiological role for cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of diseases and organ dysfunction. Persistent accumulation of senescent cells during aging can induce low-grade inflammation through SASP, impair the immune system, and increase susceptibility to different pathological challenges. Also, senescent cells often undergo stress and produce SASP, enhancing chronic inflammation and generating a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment by releasing cytokines and chemokines.12 Moreover, stem cells halted with senescence in a pathophysiological manner will lead to the termination of cell regeneration and malfunction of cell repair mechanisms, which can be seen in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.16 Cellular senescence is a comprehensive status of cells. It plays both physiological and pathophysiological roles in cell development and pathogenesis of diseases and organ dysfunction and involves the activation of various signaling pathways that can have both protective and harmful effects on tissue function (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Physiology and pathophysiology of cellular senescence. Senescence is a normal process during aging and embryo development as a physiological state (Spring green). It plays a critical role in disease prevention or recovery by recruiting immune cells to maintain tissue homeostasis, initiate tissue repair and remodeling, and limit tumor progression (Deep sky blue). Senescence can also contributes to generate pro-inflammatory microenvironment, supporting tumor development, and promote chronic inflammation during aging and multiple age-related disease (Light salmon).

Mechanisms of cellular senescence

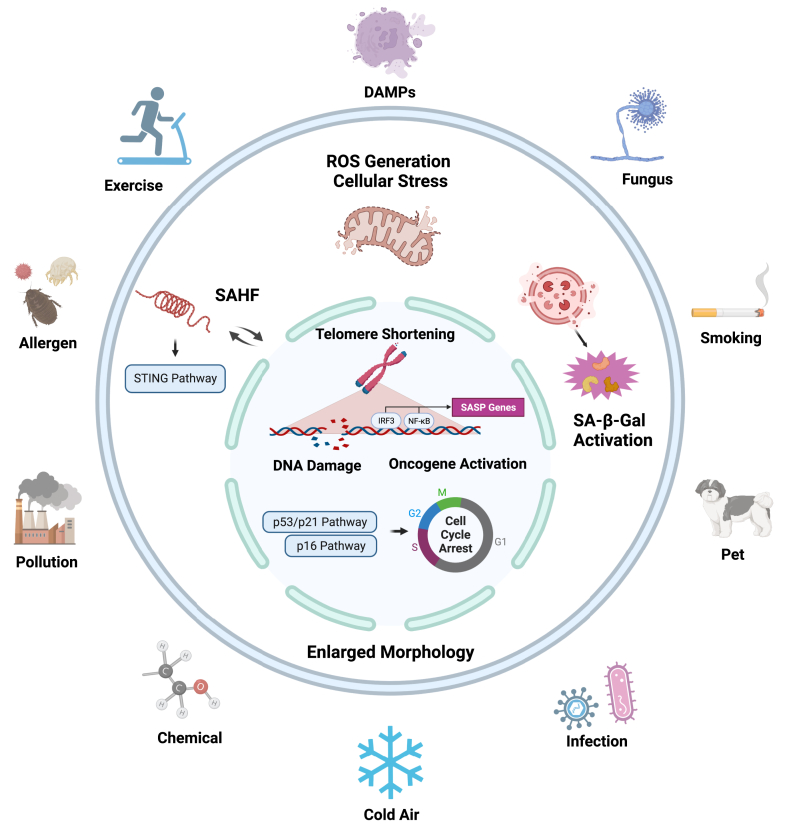

Cellular stress plays a central role in senescence as an initiator and is one of the essential features of senescence. In contrast, senescence is one of the dynamic responses to the cellular stress that sets into a non-proliferative but alive state (cell cycle arrest). Cellular stressors can break senescence-maintained homeostasis and trigger the processes of cellular senescence.17 The cellular stressors range from the external environment, such as pollutants, radiations, allergens, viral or bacterial infection, and microbes, and to internal environment, such as inflammatory products, oxidative damage, nutrient imbalance, mechanical stress, telomere attrition, genetic, and epigenetic alternations.18,19 Here, we briefly discuss how these cellular stressors induce cellular senescence, with a major focus on telomere shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activation, oxidative-related senescence, and the SASP process (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Diverse exogenous and endogenous stresses trigger cellular senescence Hallmarks of cellular stress responses that link the triggers of asthma exogenous to the cellular senescence. These hallmarks include telomere shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activation, and oxidative related senescence that lead to enlarged cell morphology with a group of changes including senescence associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activation, cell cycle arrest (e.g., p16, p21), and release of SASP components.

Telomere shortening

The telomere is a DNA-protein structure on the end of the chromosome that protects the structural stability of genome DNA and has been implicated in the aging process.19 Telomeres at the ends of chromosomes comprise repeat sequences (TTAGGG) that shorten with each cell division because of the nature of the DNA replication machinery.20 They protect against chromosomal damage by preventing chromosome–chromosome fusions and degradation and subsequently maintaining genome integrity.21 Telomere shortening occurs in normal somatic cells following each cell division. Once they reach a certain minimum length, they lose the capacity to maintain the telomere-loop structure that caps chromosome ends and leads to cellular apoptosis because of chromosome end fusion. Telomere uncapping also initiates a DNA damage response that activates the p53–p21 tumor suppressor pathway and subsequently cellular senescence.22 Telomere lengthening or shortening is now one of the intriguing biomarkers that could predict the preceding or prevent the development of diseases. Telomere shortening is now considered an indicator of the aging process or senescence and has been associated with aging and increased risks of chronic diseases.23 Therefore, it is critical to maintain telomere length to protect against the exogenous or endogenous stimuli-triggered aging process and cellular senescence.

DNA damage

DNA damage is characterized by the DNA modifications that change DNA coding properties or function in its transcription or replication.24 DNA damage occurs in different forms, such as single-strand breaks (SSBs), double-strand breaks (DSBs), DNA-protein cross-links, and insertion/deletion mismatches. DNA damage, especially DSBs, can induce a DNA damage response (DDR) that leads to repair, apoptosis, or senescence. DDR serves as the coping mechanism to any harmful genome changes that helps stabilize DNA structure and keeps cells healthy.25 DDR has a central role in cellular senescence. Not only does it contribute to the irreversible loss of replicative capacity but also to the production and secretion of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and SASP.26 DDR is characterized by activation of sensor kinases [ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/ataxia-telangiectasia Rad3-related (ATR)], formation of DNA damage foci containing phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX) and induction of checkpoint proteins, such as p53 (TP53) and the CDK inhibitor p21 (CDKN1A), ultimately leading to cell cycle arrest (senescence).27 Persistent and irreparable DNA damage occurs with p53 activation and ROS generation as assessed by positive staining of DNA damage maker γH2AX and negative DNA repair protein 53BP1.26 Mechanistically, there is a feedback loop between DNA damage and senescence. Senescence can cause the failure of the clearance of cytoplasmic DNA, which can further activate the senescent sensing mechanism via cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and trigger the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) to promote senescence and SASP release.28 Furthermore, telomere shortening is one kind of DNA damage because the DSBs or other types of DNA injuries may frequently occur in cells with shortened telomeres.29

Oncogene-induced senescence

Oncogene activation is recognized as a critical mechanism for the initiation and development of cancer. Especially, the activation of oncogenes can promote cell proliferation as a necessary step in tumorigenesis in many cancer types, and it may act as a genetic stress and cause irreversible growth arrest (senescence).30 An activating mutation of an oncogene, such as Myc, Ras, Akt, and Raf, drives ROS production and activates DDR or mTOR signaling, inducing cellular senescence, termed oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). OIS is a complex molecular program characterized by a robust and sustained antiproliferative response to the aberrant activation of oncogenic signaling or the inactivation of a tumor-suppressor gene.30 Of these, Ras, a GTPase frequently mutated in cancer, has been suggested to play a significant role in OIS and affect tumorigenesis. RAS protein has been shown to accelerate p53-dependent cellular senescence through the p38MAPK pathway and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways.31 Additionally, oncogene-activating related senescence can be induced independent of telomere erosion through both TP53/p21 and p16 pathways.32

Oxidative-induced senescence

Oxidative stress plays a central role in triggering cellular senescence. Stressors from exogenous, such as UV, PM2.5, cigarette, or allergen, or endogenous such as cytokines, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from dead cells, or other internal triggers (Fig. 1), can cause ROS production via mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial sources.33 ROS can act as signaling molecules in both the induction and stabilization of senescence through directly oxidizing subcellular structures, including nucleic acids and enzymes, causing oncogene activation, DNA damage, and reduced telomerase activity.34 Moreover, ROS can also act as the secondary messenger activating redox signaling pathways consisting of MEK/ERK, JNK, and NF-κB signaling.35 Studies have shown that cellular senescence can be engaged in activated redox signaling cells in pulmonary fibrosis.36 When stress exists consistently and exceeds the antioxidant capacity, the senescence process will continue. Otherwise, the senescence process will shift to autophagy, restoring to a proliferative state with reduced expression of senescence markers.37 The activation of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways contributes to the generation of ROS and SASP, which have been shown to induce and stabilize the senescent phenotype.12 Thus, oxidative stress is one of the necessary and critical mechanisms underlying stressor-induced cellular senescence.

Senescence associated secretory phenotype

Telomere shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activation, and oxidative stress can induce SASP to different extents. These secreted SASP exert their effects on the local tissue microenvironment of senescent cells that can alter the phenotypic features of nearly non-senescent cells.38 The main components of SASP include cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, other inflammatory factors, receptors/ligands, oxidative factors, exosomes, and extracellular matrix contents (Table 1). These SASP-associated molecules and pathways play a crucial role in mediating the pathophysiological effects of senescent cells in chronic inflammation, tissue damage, and the tumorigenesis through cell-to-cell communication and creation of microenvironments.39 Notably, these molecules and pathways vary substantially, depending on the stimuli, duration of senescence, environment and cell type.12 Furthermore, SASP has been linked to its beneficial and detrimental effects across cell development, repair, tumor genesis, and inflammatory contexts.7 As beneficial functions, SASP can recruit immune cells to maintain tissue homeostasis, initiate tissue repair and remodeling through the removal of damaged cells, and limit tumor progression by ensuring that damaged or potentially dysfunctional cells fail to immortalize their genomes to the next generation.12 As deleterious functions, SASP can induce a pro-inflammatory microenvironment, promote chronic inflammation, and support tumor development. SASP factors, including IL-6, IL-1RA, and IFN-γ, promote chronic inflammation during aging and multiple age-related diseases. Mechanistically, SASP acts as a double-edged sword with both beneficial and detrimental effects on human diseases, depending on the composition and length of exposure to the SASP.12 Short-term exposure to the SASP may facilitate its beneficial effects, whereas long-term exposure may contribute to its deleterious effects.

Table 1.

Major components of senescent associated secretory phenotypes.

| Categories | SASP |

|---|---|

| Cytokine | IL-1/6/7/8/11/13/15/33 |

| Chemokine | IL-8(CXLC8), GRO-a/b/g (CXCL1/2/3), CXCL5/6/13, MCP-1/2/4, MIP-1a/3a, I-TAC, CCL1/2/11/16/20/25/26, LIF |

| Growth factor | Amphiregulin, Angiogenin, Epiregulin, Heregulin, EGF, bFGF, HGF, KGF (FGF7), VEGF, Angiogenin, SCF, SDF-1, PIGF, NGF, IGFBP-1/2/3/4/6/7, VEGF, TGF-β, |

| Other inflammatory factors | GM-CSF, G-CSF, IFN-1/γ, MIF |

| Receptors and Ligands | Leptin, CXCR2, ICAM-1/3, OPG, sTNFRI/II, TRAIL-R3, Fas, uPAR, IL6ST, EGF-R, SAA1, TNFRSF18, SERPINE1, PIGF, sTNFRI/II |

| Oxidative factors | Nitric Oxide, ROS, COX2 |

| Extracellular matrix contents | MMP1/2/3/10/12/13/14, SERPINs, TIMP1/2, Collagen, Laminin, Fibronectin, tPA, uPA |

| Exosome contents | GDF15, STC1, MMP1 |

Senescence and asthma phenotypes

Asthma in the elderly is considered a “different entity” than typical asthma because of several unique features, including clinical presentation, comorbidities, physiology, and treatment strategies.40 They may have a more insidious onset of symptoms, with less wheezing and more dyspnea, cough, and chest tightness. Furthermore, these patients may have decreased lung function, reduced airway responsiveness, and impaired immune function. Senescence is a complex process that the cellular response to senescence-inducing stimuli can vary depending on the cell type, age, and underlying health status.41 For example, airway epithelial progenitor cells become increasingly senescent with age, making the epithelium more susceptible to challenges such as environmental allergens/pollutants. Additionally, different cell types, including structural and immune cells, could play a role in contributing to senescence and its downstream response to various stressors.8 Here we review the literature regarding the link of cellular senescence to asthma phenotypes, airway inflammation and remodeling, with a special focus on different senescent cells, including structural and immune cells, and their influences on the development of asthma phenotypes.

Airway inflammation

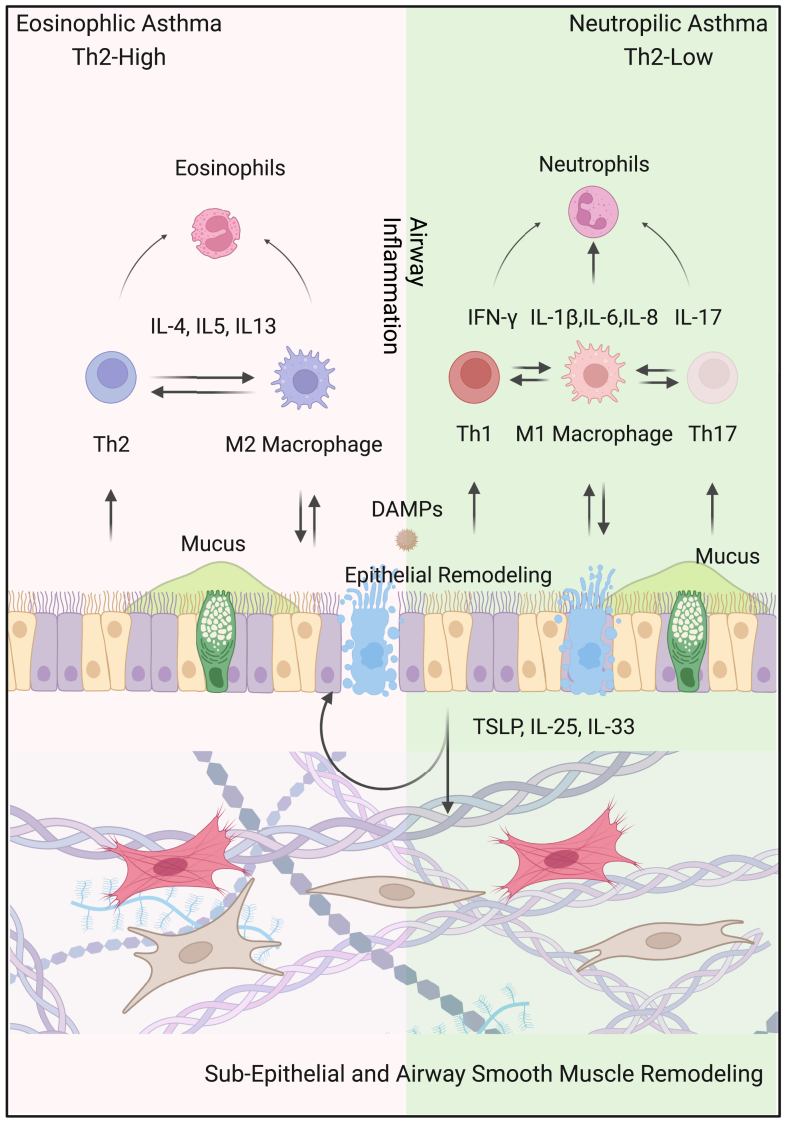

Typical features of airway inflammation are increased eosinophils, mast cells, Th2 cells that produce mediators such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.42 Airway epithelial cells physiologically function as the first line of defense in innate immunity, preventing environmental allergens/pollutants and secrete IL-33, IL-25 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) that can induce Th2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) activation to potentiate allergen-induced Th2-associated airway inflammation.43,44 As shown in Fig. 3, depending on the priming of lung immune cells, subjects with asthma might generate eosinophilic (Th2-high) and neutrophilic (Th2-low) asthma. Th2-high asthma is mainly related to Th2 lymphocytes and M2-polarized macrophages that can enhance eosinophilic inflammation via releasing inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4. IL-5, IL-13, and TGF-β). In contrast to Th2 high, Th2-low asthma is related to Th1, Th17 lymphocytes, and M1 macrophages that can release Th1, Th17, and M1 macrophage-related cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α), further promoting the neutrophilic inflammation. Recent advances suggest cellular senescence as a mechanism in airway inflammation. While the mechanisms remain unclear, developmental and replicative senescence have been suggested to play a vital role in airway inflammation.12 Stress-induced senescence in response to stressors such as pollution, smoking, or allergens causes the secretion of SASP, thereby leading to an increased airway inflammation.40 Furthermore, different cell types, including structural and immune cells, may contribute to senescence and airway inflammation in response to various stressors. The epithelium forms the primary barrier against pathogen infection, and the senescence of epithelial can lead to decreased protection through the loss of tight junctions and altered properties.45 Integrin b4 (ITGB4), a cell surface protein maintaining the integrity of airway, is decreased in the airway epithelial cells of patients with asthma.46 Airway epithelial cells in mice lacking ITGB4 were more senescent and less proliferative through p53 signaling pathway. Importantly, mice lacking ITGB4 showed severe inflammation in asthma. Additionally, TSLP can induce cellular senescence with elevated p21 and p16 in a dose-dependent manner in airway epithelial cells in asthma.45 Furthermore, increased cellular senescence was also found in bronchial fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the lung tissues of asthmatics, which could lead to a low-level inflammation through release of SASP-linked cytokines, chemokines, and matrix remodeling protease.47 Immune cells, such as eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, and B cells, can also undergo senescence in response to chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to the secretion of cytokines/chemokine that contribute to the chronic inflammation.8 Of these, senescent eosinophils can release inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which can amplify the inflammatory response in the airways. Similarly, senescent macrophages have been identified in the airways of patients with asthma, and senescent macrophages can produce higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS, leading to increased airway inflammation and oxidative stress. Senescent T cells would change the T-cell mediated adaptive immunity with reduced function, leading to impaired immune responses and increased susceptibility to infections.48 Furthermore, Th17 cells are increased with aging and IL17 from Th17 cells can enhance the secretion of SASP, contributing to a pro-inflammatory status in airways.8 Collectively, these studies indicate that both senescent structural and immune cells have a greater contribution to airway inflammation in asthma, and there might be a reciprocal relationship between inflammation and senescence49

Fig. 3.

Overview of the major features of asthma. Asthma is divided into two endotype: eosinophilic (Th2-high) and neutrophilic (Th2-low). Th2-high asthma is mainly related to Th2 lymphocytes and M2-polarized macrophages that can enhance eosinophilic inflammation via releasing inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and TGF-β). Th2-low asthma is related to Th1, Th17 lymphocytes, and M1 macrophages that can release Th1, Th17, and M1 macrophage-related cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-1β/IL-6/IL-8), further promoting the neutrophilic inflammation. Asthma is also characterized by structural changes (remodeling), including epithelial damage, subepithelial fibrosis, and increased smooth muscle mass. Stressors (DAMPs, pollutants, allergens) can induce airway epithelial cells to release cytokines like TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33, promoting airway remodeling and inflammation.

Airway remodeling

Persistent chronic inflammation and increased growth factors could lead to increased airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass, leading to airway remodeling and irreversible airway obstruction. Increased senescence has been found in airway fibroblasts and ASM cells from asthmatic patients.9 Stress-induced senescence may contribute to the development of airway remodeling, which involves structural changes in the airways, including increased smooth muscle mass, fibrosis, and angiogenesis, which can lead to a loss of lung function over time. Studies have shown that senescent cells can contribute to airway remodeling by producing extracellular matrix proteins and other factors that promote fibrosis and angiogenesis. ASM cells are the major cell types because of their role in airway contractility and remodeling through cell proliferation and fibrosis in asthma.50 Isolated ASM cells from elderly patients with asthma showed up-regulation of multiple senescent markers such as p21WAF1/Cip1, p16INK4A, telomere-associated foci (TAF), and SA-β-gal, along with changes in SASP components such as IL-6 and IL-8. These increased SASP modulators from senescent ASM cells are major drivers inducing airway fibrosis and remodeling in elderly patients with asthma. Furthermore, IgE, a key player in the development of airway inflammation and remodeling in allergic asthma, induced senescence of ASM cells via upregulating lincRNA-p21-p21 pathway in OVA-asthma model.51 In addition to ASM cells, other cell types also involve in fibrosis and airway remodeling, such as epithelium and fibroblasts. Senescent epithelial cells express remodeling factors such as TGF-β1, EGF, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that can enhance airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling.52,53 Of interest, lung fibroblast in the basement membrane can enhance epithelial cell proliferation or regeneration for airway repair/remodeling via releasing SASP and exosomes.54,55 In addition, senescent immune cells can produce MMPs, causing airway wall thickening and fibrosis and subsequently exacerbation of airway obstruction and asthma symptoms. Senescent B cells can produce autoantibodies, which contribute to airway wall thickening and fibrosis by binding to airway cells and activating their downstream signaling pathways.56 Thus, it remains possible that multiple senescent cell types regulate multiple cell types via SASP and exosomes, leading to the observed airway remodeling.

Senescence as a therapeutic target for asthma

Strategies to suppress the pathological effect of senescent cells during aging by preventing senescence onset or promoting senescent cell clearance have demonstrated a great promise for the treatment of a variety of diseases and improvement of standard therapies.57 However, cellular senescence is a highly phenotypically heterogeneous process throughout the tissues, which has been an obstacle in the discovery of totally specific and accurate therapeutic strategies.8 Given that cellular senescence has been associated with airway inflammation and remodeling, targeting cellular senescence should be employed or developed as therapeutic strategies for asthma. Several approaches targeting senescence, including senolytics, senomorphics, immunotherapy, and function restoration, have emerged as promising strategies for the prevention or treatment of diseases.58 Here we summarize the status of the development of senotherapeutics with the focus on senolytics and senomorphics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Potential senescence targeted strategies for asthma treatment.

| Senolytics | Senomorphics (Targeting SASPs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removing senescent sells | Targeting pathways | Neutralizing activities and functions | |||

| Pathway | Molecule | Pathway | Molecule | Target | Antibody |

| PI3K/AKT | Dasatinib | Nrf2/PINK | MitoQ | Anti-IL-4R | Dupilumab |

| Fisetin | Melatonin | ||||

| Navitoclax | Ganoderma | ||||

| Quercetin | Sesamin | ||||

| JN-PK1 | |||||

| Azithromycin | |||||

| BCL | ABT-737 | NF-κB | Metformin | Anti-IL-5/R | Mepolizumab |

| ABT-199 | Evodiamine | Benralizumab | |||

| ABT-263 | Curcumin | Reslizumab | |||

| HIF-1 | Chryseriol | SIRT1/SIRT3 | Bergenin | Anti-IL-13/R | Dupilumab |

| Vitamin D | SRT1720 | Cendakimab | |||

| EGCG | Myricetin | Anti-IL-25 | ABM125 | ||

| Azithromycin | |||||

| JAK | Ruxolitinib | Anti-IL-33 | Etokimab | ||

| GDC-0214 | GSK3772847 | ||||

| GDC-4379 | Itepekimab | ||||

| Wnt/β-Catenin | Klotho | Anti-IL-6 | Tocilizumab | ||

| ICG001 | Anti-TSLP | Tezepelumab | |||

| Ecleralimab | |||||

| Anti-IgE | Omalizumab | ||||

Senolytics

Drugs that can specifically delete senescent cells are called senolytics, which can improve organ function and prevent disease. Senolytics were developed based on their functional characteristics, which target mainly the upregulated anti-apoptosis system and are designed to induce lysis of senescent cells, such as p21, p53, FOXO4, PI3K/AKT, Bcl-2 family members, and HIF-1α.59 Through bioinformatical analysis, several potential senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAPs) were identified, which mainly includedPI3Kδ/Akt/metabolic, Bcl-2/B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (Bcl-xl)/Bcl-w, HIF-1α.59 Of these, dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor as an FDA-approved anti-cancer drug, has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and migration, and to induce apoptosis. Quercetin, as a naturally occurring flavonoid, showed interactions with a PI3K isoform and Bcl-2 family members and induced diverse biological activities. Intriguingly, treatment with both dasatinib and quercetin can induce apoptosis and improve age-linked diseases more efficiently than either drug alone in senescent cells. More importantly, these newly identified PI3K/AKT, BCL, and HIF-1 pathways have been associated with nearly all aspects of asthma pathophysiology, and several senolytics (Dasatinib, Fisetin, and ABT-263/737/199) targeting these pathways have been found to inhibit airway inflammation, airway remodeling, mucous cell hyperplasia, and steroid-insensitive airway inflammation in different mouse models of asthma.60, 61, 62 Several other senolytics have also been associated with different phenotypes of asthma. For example, quercetin was found to inhibit ferroptosis along with reducing M1 macrophage polarization during neutrophilic airway inflammation.13 Chryseriol, a flavonoid compound, attenuated the progression of OVA-induced asthma in mice through HIF-1α pathway.63 Similarly, vitamin D ameliorates asthma-induced lung injury by regulating HIF-1α/Notch1 signaling during autophagy.64 Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a phytochemical and a major substance of green tea with many beneficial effects against features of senescence (e.g., immunosenescence and inflammation), has been reported to relieve asthmatic symptoms by suppressing HIF-1α/VEGFA-mediated M2 skewing of macrophages in mice.65 Azithromycin not only regulates inflammatory responses, but also cleans senescent cells as a novel senolytic drug in asthmatic lungs. Particularly, azithromycin has been demonstrated to influence airway remodeling in asthma via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway.66

Senomorphics

The primary strategic plan of potential therapies based on senomorphics is targeting pathways related to SASP expression, such as Nrf2/PINK, NF-κB, SIRT1/SIRT3, JAK, and Wnt/β-Catenin. Compounds that inhibit these pathways, have demonstrated the ability to reduce SASP production and thus exhibit potential therapeutic benefits in asthma. Of these, mitoquinone (MitoQ), a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, has been shown to attenuate pathological features of lean and obese allergic asthma in mice.67 Similarly, melatonin, as a potential modulator of NF-κB signaling pathway, has been demonstrated to inhibit airway inflammation in epicutaneously sensitized mice.68 Metformin, a compound used clinically for type II diabetes, has been used for the treatment of age-related diseases. Recent studies have demonstrated that metformin suppresses airway inflammation and remodeling of mouse allergic asthma69 and showed a protective role in patients with asthma.70 One of the possible mechanisms for the therapeutic benefit of metformin is its pleiotropic senomorphic abilities by targeting different pathways (e.g., NF-κB, AMPKα). Many other products, targeting SASP-linked signaling pathways SIRT1/SIRT3, JAK, Wnt/β-Catenin, and antioxidants, have been shown to inhibit airway hyperresponsiveness, M2 skewing of macrophages, and lung inflammation, such as Sirtuin activators Bergenin, SRT1720, and Myricetin, JAK inhibitors Ruxolitinib, GDC-0214, and GDC-4379, and Wnt/β-Catenin inhibitor Klotho and ICG001.

A second approach is to suppress senescent cell characteristics through the neutralization of the activity and function of specific SASP factors, such as IL-1α, IL-6, and IL-8, with specific antibodies. These molecules or antibodies slow down the progression of senescence phenomenon without cell death.71,72 One of the hypotheses is that the intrinsic inflammation may induce cellular senescence through increased inflammatory mediators in asthma (Th2-high: IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13; Th-low: IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-1β) or SASP components (e.g., IL-6, IL8, IL-33, MMPs, see Table 1). For example, TSLP is not only critical in inducing Th2 inflammation and airway remodeling in asthma but also important in triggering senescence in airway epithelial cells.45 Tezepelumab, a human monoclonal antibody that blocks TSLP, is effective in patients with severe and uncontrolled asthma.73,74 Inhalation of anti-TSLP antibody fragment, Ecleralimab, blocks response to allergens in mild asthma.75 Similarly, several well-known monoclonal antibodies, including anti-IL-4R (Dupilumab), anti-IL-5/R (Mepolizumab, Reslizumab, Benralizumab), anti-IL-6R (Tocilizumab), anti-IL-25 (ABM125), IL-13 (Cendakimab), IL-33 (Etokimab, GSK3772847, Itepekimab), and anti-IgE (Omalizumab), are effective and safe in asthma. While these compounds and antibodies have been shown to improve inflammation in asthma, it is important to note that their precise mode of action in the context of cellular senescence and SASPs is not fully understood. Thus, further research is warranted to investigate the specific mechanisms of these potential therapeutic agents in the context of cellular senescence and SASPs in asthma.

Senotherapeutics with senolytics compared to senomorphics

Senolytics are pharmacological agents that selectively kill “senescent cells”, which can minimize off-target effects on healthy cells and have a faster therapeutic effect compared to senomorphics. The biggest challenge is that eliminating senescent cells could interfere with the beneficial effects of these cells. Indeed, senescence is not universally detrimental, but rather has beneficial biological functions in certain contexts. In contrast, senomorphics prevent the detrimental cell-extrinsic effects of senescent cells, which provide an alternative pharmacological approach to modulate functions and morphology of senescent cells by suppressing the secretion of deleterious SASP components without cell elimination. However, senomorphics do not directly eliminate senescent cells, so the therapeutic effect may be slower and less pronounced than with senolytics. Furthermore, senomorphics may not be effective in all types of senescent cells, since different cells can have distinct senescence-associated phenotypes.

Outstanding questions

Asthma has a high prevalence particularly in the elderly populations. Cellular senescence in asthmatic lung and the possible use of senotherapies are critical for asthma patients, but little is known about the cellular senescence pathways and their contributions to clinical asthma phenotypes as well as the senescence-targeted senotherapeutics in asthma.

Conclusions

Cellular senescence is a comprehensive status of cells and plays both physiological and pathophysiological roles in cell development, pathogenesis of diseases, and organ dysfunction. Several cellular stress responses have been suggested to link the triggers of asthma to cellular senescence, including telomere shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activation, oxidative related senescence, and SASP. However, senescence is a complex process. Cellular response to senescence-inducing stimuli may vary depending on the cell type, age, and underlying health status. Asthma in the elderly is often considered a “different entity” and may have decreased reduced airway responsiveness and impaired immune function. Persistent accumulation of senescent cells in elderly patients with asthma can promote airway inflammation and impaired cellular function through SASP. Different senescent structural and immune cells have been associated with different immune responses and major clinical endotypes of asthma patients. However, cellular senescence shows either detrimental or beneficial effects in different studies, depending on cell types, exogenous and endogenous stressors, and degree of immune responses to stressors. Thus, future studies are warranted in linking specific senescence pathways to specific aspects of asthma, which could provide a rationale for designing senescence-targeting drugs for asthma. While both senolytics and senomorphics have shown a great promise as therapeutic approaches for asthma, they have their advantages and limitations. Furthermore, given that the relationship between airway inflammation and airway remodeling in asthma is complex and bidirectional, targeting both processes is critical to improve outcomes for patients with asthma. Taken together, targeting senescence therapies hold great potential to substantially treat asthma, but extensive studies are still needed to develop specific and accurate therapeutic strategies to treat asthma.

Contributors

Rongjun Wan: Writing—original draft, generating Figures and Tables.

Prakhyath Srikaram: Review & editing.

Vineeta Guntupalli: Review & editing.

Chengping Hu: Conceptualisation & supervision.

Qiong Chen: Conceptualisation & supervision.

Peisong Gao: Conceptualisation, supervision, and writing–review & editing.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

Data for this Review were identified by searches of MEDLINE, Current Contents, PubMed, and references from relevant articles using the search terms “senescence”, “asthma”, “SASP”, “senolytics”, and “senomorphics”. Only articles published in English between 2015 and 2023 were included.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1R01AI153331 and R01AI141642), and the NIH had no role in the paper design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Collaborators GBDCRD Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanda A., Baptist A.P., Divekar R., et al. Asthma in the older adult. J Asthma. 2020;57(3):241–252. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1565828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn R.M., Busse P.J., Wechsler M.E. Asthma in the elderly and late-onset adult asthma. Allergy. 2018;73(2):284–294. doi: 10.1111/all.13258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., Zhang X., Zhang L., et al. Age-related clinical, inflammatory characteristics, phenotypes and treatment response in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;11:210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busse W.W., Kraft M. Current unmet needs and potential solutions to uncontrolled asthma. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(163) doi: 10.1183/16000617.0176-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorgoulis V., Adams P.D., Alimonti A., et al. Cellular senescence: defining a path forward. Cell. 2019;179(4):813–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Micco R., Krizhanovsky V., Baker D., d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(2):75–95. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00314-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z.N., Su R.N., Yang B.Y., et al. Potential role of cellular senescence in asthma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:59. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aghali A., Khalfaoui L., Lagnado A.B., et al. Cellular senescence is increased in airway smooth muscle cells of elderly persons with asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2022;323(5):L558–L568. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Zamudio R.I., Robinson L., Roux P.F., Bischof O. SnapShot: cellular senescence in pathophysiology. Cell. 2017;170(5):1044.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes P.J., Baker J., Donnelly L.E. Cellular senescence as a mechanism and target in chronic lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(5):556–564. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1975TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumari R., Jat P. Mechanisms of cellular senescence: cell cycle arrest and senescence associated secretory phenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.645593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shvedova M., Samdavid Thanapaul R.J.R., Thompson E.L., Niedernhofer L.J., Roh D.S. Cellular senescence in aging, tissue repair, and regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:4s–11s. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karin O., Agrawal A., Porat Z., Krizhanovsky V., Alon U. Senescent cell turnover slows with age providing an explanation for the Gompertz law. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5495. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X., Qu M., Li J., Danielson P., Yang L., Zhou Q. Induction of fibroblast senescence during mouse corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(10):3669–3679. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-26983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L., Chen R., Li G., et al. FBW7 mediates senescence and pulmonary fibrosis through telomere uncapping. Cell Metab. 2020;32(5):860–877.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galluzzi L., Yamazaki T., Kroemer G. Linking cellular stress responses to systemic homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(11):731–745. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gangwar R.S., Bevan G.H., Palanivel R., Das L., Rajagopalan S. Oxidative stress pathways of air pollution mediated toxicity: recent insights. Redox Biol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J., Epel E. Stress and telomere shortening: insights from cellular mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;73 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wai K.M., Swe T., Myar M.T., Aisyah C.R., Hninn T.S.S. Telomeres susceptibility to environmental arsenic exposure: shortening or lengthening? Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1059248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackburn E.H. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature. 1991;350(6319):569–573. doi: 10.1038/350569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y., Liu X., Ding X., Wang F., Geng X. Telomere and its role in the aging pathways: telomere shortening, cell senescence and mitochondria dysfunction. Biogerontology. 2019;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10522-018-9769-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett J.H., Iles M.M., Dunning A.M., Pooley K.A. Telomere length and common disease: study design and analytical challenges. Hum Genet. 2015;134(7):679–689. doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1563-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao K.S. Genomic damage and its repair in young and aging brain. Mol Neurobiol. 1993;7(1):23–48. doi: 10.1007/BF02780607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soto-Palma C., Niedernhofer L.J., Faulk C.D., Dong X. Epigenetics, DNA damage, and aging. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(16) doi: 10.1172/JCI158446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correia-Melo C., Hewitt G., Passos J.F. Telomeres, oxidative stress and inflammatory factors: partners in cellular senescence? Longev Healthspan. 2014;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shmulevich R., Krizhanovsky V. Cell senescence, DNA damage, and metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021;34(4):324–334. doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H., Wang H., Ren J., Chen Q., Chen Z.J. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(23):E4612–E4620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705499114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae N.S., Baumann P. A RAP1/TRF2 complex inhibits nonhomologous end-joining at human telomeric DNA ends. Mol Cell. 2007;26(3):323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X.L., Ding J., Meng L.H. Oncogene-induced senescence: a double edged sword in cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(10):1553–1558. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y., Li N., Xiang R., Sun P. Emerging roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(6):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rattanavirotkul N., Kirschner K., Chandra T. Induction and transmission of oncogene-induced senescence. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(3):843–852. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03638-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forman H.J., Zhang H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20(9):689–709. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renaudin X. Reactive oxygen species and DNA damage response in cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2021;364:139–161. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang X., He B., Ning Q., et al. Alantolactone suppresses inflammation, apoptosis and oxidative stress in cigarette smoke-induced human bronchial epithelial cells through activation of Nrf2/HO-1 and inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathways. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01358-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H., Chen H., Liang J., et al. TGF-beta1/IL-11/MEK/ERK signaling mediates senescence-associated pulmonary fibrosis in a stress-induced premature senescence model of Bmi-1 deficiency. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(1):130–151. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0371-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma D., Stokes K., Mahngar K., Domazet-Damjanov D., Sikorska M., Pandey S. Inhibition of stress induced premature senescence in presenilin-1 mutated cells with water soluble Coenzyme Q10. Mitochondrion. 2014;17:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohtani N. The roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): can it be controlled by senolysis? Inflamm Regen. 2022;42(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s41232-022-00197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao H., Wu L., Yan G., et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):263. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00658-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parikh P., Wicher S., Khandalavala K., Pabelick C.M., Britt R.D., Jr., Prakash Y.S. Cellular senescence in the lung across the age spectrum. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019;316(5):L826–L842. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00424.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuliga M., Read J., Knight D.A. Ageing mechanisms that contribute to tissue remodeling in lung disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambrecht B.N., Hammad H. The immunology of asthma. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(1):45–56. doi: 10.1038/ni.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boonpiyathad T., Sozener Z.C., Satitsuksanoa P., Akdis C.A. Immunologic mechanisms in asthma. Semin Immunol. 2019;46 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agache I., Cojanu C., Laculiceanu A., Rogozea L. Critical points on the use of biologicals in allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12(1):24–41. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J., Dong F., Wang R.A., et al. Central role of cellular senescence in TSLP-induced airway remodeling in asthma. PLoS One. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C., Liu H.J., Xiang Y., Tan Y.R., Zhu X.L., Qin X.Q. Wound repair and anti-oxidative capacity is regulated by ITGB4 in airway epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;341(1-2):259–269. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0457-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schafer M.J., White T.A., Iijima K., et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynch M.D., McFadden J.P., White J.M., Banerjee P., White I.R. Age-specific profiling of cutaneous allergy at high temporal resolution suggests age-related alterations in regulatory immune function. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;140(5):1451–1453.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen N.C., Reyes N.S., Lee J.Y., Peng T. Intersection of inflammation and senescence in the aging lung stem cell niche. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.932723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergeron C., Tulic M.K., Hamid Q. Airway remodelling in asthma: from benchside to clinical practice. Can Respir J. 2010;17(4):e85–e93. doi: 10.1155/2010/318029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo W., Gao R., Zhang W., et al. IgE aggravates the senescence of smooth muscle cells in abdominal aortic aneurysm by upregulating LincRNA-p21. Aging Dis. 2019;10(4):699–710. doi: 10.14336/AD.2018.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boulet L.P. Airway remodeling in asthma: update on mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(1):56–62. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng X., Yang Y., Zheng Y., Song J., Hu Y., Xu F. Effects of catalpol on asthma by airway remodeling via inhibiting TGF-beta1 and EGF in ovalbumin-induced asthmatic mice. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(7):4084–4093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reyes N.S., Krasilnikov M., Allen N.C., et al. Sentinel p16(INK4a+) cells in the basement membrane form a reparative niche in the lung. Science. 2022;378(6616):192–201. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haj-Salem I., Plante S., Gounni A.S., Rouabhia M., Chakir J. Fibroblast-derived exosomes promote epithelial cell proliferation through TGF-β2 signalling pathway in severe asthma. Allergy. 2018;73(1):178–186. doi: 10.1111/all.13234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frasca D. Senescent B cells in aging and age-related diseases: their role in the regulation of antibody responses. Exp Gerontol. 2018;107:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lucas V., Cavadas C., Aveleira C.A. Cellular senescence: from mechanisms to current biomarkers and senotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2023;75:675. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.122.000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L., Pitcher L.E., Prahalad V., Niedernhofer L.J., Robbins P.D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 2023;290(5):1362–1383. doi: 10.1111/febs.16350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wissler Gerdes E.O., Zhu Y., Tchkonia T., Kirkland J.L. Discovery, development, and future application of senolytics: theories and predictions. FEBS J. 2020;287(12):2418–2427. doi: 10.1111/febs.15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo E.J., Ojiaku C.A., Sunder K., Panettieri R.A., Jr. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase in asthma: novel roles and therapeutic approaches. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56(6):700–707. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0308TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian B.P., Xia L.X., Bao Z.Q., et al. Bcl-2 inhibitors reduce steroid-insensitive airway inflammation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017;140(2):418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dewitz C., McEachern E., Shin S., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha inhibition modulates airway hyperresponsiveness and nitric oxide levels in a BALB/c mouse model of asthma. Clin Immunol. 2017;176:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mo S., Deng H., Xie Y., Yang L., Wen L. Chryseriol attenuates the progression of OVA-induced asthma in mice through NF-κB/HIF-1α and MAPK/STAT1 pathways. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2023;51(1):146–153. doi: 10.15586/aei.v51i1.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang C., Peng M., Tong J., et al. Vitamin D ameliorates asthma-induced lung injury by regulating HIF-1α/Notch1 signaling during autophagy. Food Sci Nutr. 2022;10(8):2773–2785. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang N., Li X. Epigallocatechin gallate relieves asthmatic symptoms in mice by suppressing HIF-1α/VEGFA-mediated M2 skewing of macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;202 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao X., Yu F.Q., Huang X.J., et al. Azithromycin influences airway remodeling in asthma via the PI3K/Akt/MTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2018;32(5):1079–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chandrasekaran R., Bruno S.R., Mark Z.F., et al. Mitoquinone mesylate attenuates pathological features of lean and obese allergic asthma in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2023;324(2):L141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00249.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu X., Zhang Y., Ren Y., Li J. Melatonin prevents allergic airway inflammation in epicutaneously sensitized mice. Biosci Rep. 2021;41(9) doi: 10.1042/BSR20210398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma W., Jin Q., Guo H., et al. Metformin ameliorates inflammation and airway remodeling of experimental allergic asthma in mice by restoring AMPKalpha activity. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.780148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu T.D., Fawzy A., Akenroye A., Keet C., Hansel N.N., McCormack M.C. Metformin use and risk of asthma exacerbation among asthma patients with glycemic dysfunction. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(11):4014–40120.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Childs B.G., Gluscevic M., Baker D.J., et al. Senescent cells: an emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(10):718–735. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lagoumtzi S.M., Chondrogianni N. Senolytics and senomorphics: natural and synthetic therapeutics in the treatment of aging and chronic diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;171:169–190. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zoumot Z., Al Busaidi N., Tashkandi W., et al. Tezepelumab for patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:1665–1679. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S378062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Menzies-Gow A., Corren J., Bourdin A., et al. Tezepelumab in adults and adolescents with severe, uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(19):1800–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gauvreau G.M., Hohlfeld J.M., FitzGerald J.M., et al. Inhaled anti-TSLP antibody fragment, ecleralimab, blocks responses to allergen in mild asthma. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01193-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]