Abstract

Background:

We aimed to investigate the relationship between air pollution and the Infant mortality rate (IMR) during nearly ten years in Tehran, Iran.

Methods:

This study is a retrospective cohort case using time series analysis. Air pollution monitoring data during the study period (2009–2018) were collected from the information of 23 Air Quality Control Centers in different areas of Tehran. For this purpose, the daily measures of PM10, PM2.5, O3, CO, SO2, NO2 were obtained. Data on infant mortality was obtained from the National Statistics Office of Iran and mortality registered in Tehran’s main cemetery during the study period. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models were used.

Results:

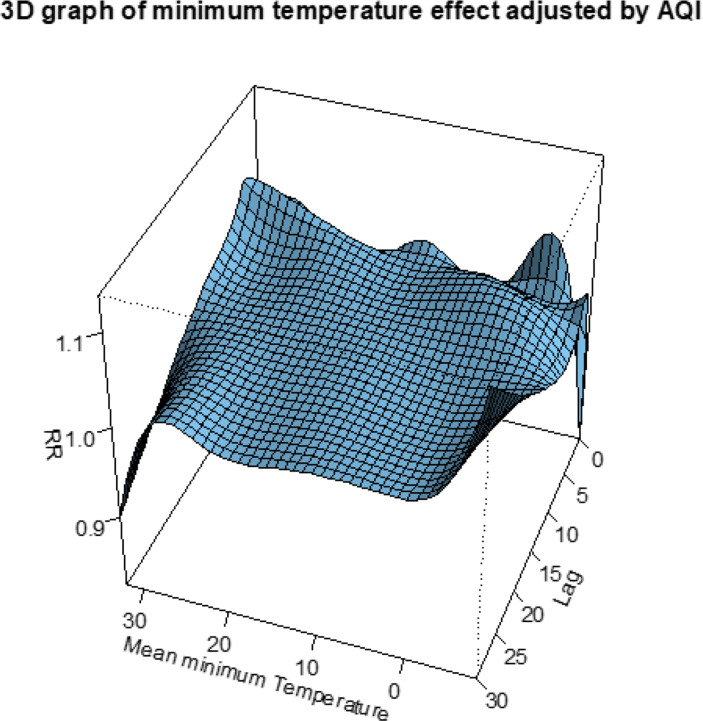

A total of 23,206 infant deaths were reported during the study period. Following an increase of 10 ug/m3 in PM10 in an early day of exposure, the risk of mortality increased significantly (RR=1.003, 95%CI:1.001–1.005). There is a pick on lag 5–10 that shows a very strong and immediate effect of cold temperature which means that cold temperatures increase the risk of mortality at an early time. At cold temperate, (var=0 and lag 0) risk of infant mortality was significantly higher than reference temperature (19°C) (RR=1.1295, %CI: 1.01–1.25).

Conclusion:

The results show the adverse effects of PM10 exposure on infant mortality in Tehran, Iran. Accordingly, a steady decline in PM10 levels in Tehran may have greater benefits in reducing the Infant mortality rate.

Keywords: Air pollution, Infant mortality rate, Time series

Introduction

Air pollution is one of the major problems in population growth, especially in urban and metropolitan areas. For many centuries, it has become a common global problem that can no longer be ignored (1). There is increasing evidence that exposure to air pollution has several health impacts and can affect morbidity and mortality during pregnancy (2), early life (3), adults, and the elderly (4). According to the WHO report that summarizes the latest scientific knowledge on the links between exposure to air pollution and adverse health effects in children, numerous studies showed a significant association between exposure to air pollution and adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm delivery, low birth weight, stillbirth, and small for gestational age (1).

The developing fetuses, infants, and children are among the most biologically and psychologically vulnerable groups to the many adverse effects of air pollution, and exposure to air pollution is an overlooked health concern for children worldwide (1, 5–7). This increased risk is due to exposure to air pollution in children due to a combination of behavioral, environmental, and physiological factors.

The first year of life is especially important for providing health infrastructure and improving the quality of life. Infant mortality rate (IMR), a most sensitive indicator of population health, defined as death before completion of the first year of life is frequently used as a global indicator of health and well-being (8). IMR is one of the most important health, cultural and economic indicators of any society, which is considered in assessing the health of society. It is an explanatory variable for achieving the socio-economic development of a country (9). High IMR indicates the presence of unfavorable social, economic, and environmental conditions during the first year of life (10). It is certainly a better understanding of risk factors of infant mortality are an important public health target (11).

Although there is compelling evidence of a link between air pollution and infant mortality, however, there are relatively few studies that have evaluated the effect of air pollution on Infant mortality and most studies have focused on acute exposure and ambient air pollution and have shown that as the level of air pollution increases, the risk of infant mortality also increases (1).

According to the WHO, air pollution is the biggest environmental cause of infant mortality (1). Also, preterm birth, which is linked to air pollution, is the third environmental cause of infant mortality (12).

Since randomized clinical trials are not possible in this area, the only solution to this problem is to assess the air pollution status in different areas at a suitable time to identify the effects of air pollution on infant mortality.

Although assessing the impact of air pollution and various components of air pollutants on the health of children and infant mortality is of great importance to be examined in each country, however, few studies have been done in this regard in Iran. Accordingly, we aimed to investigate the relationship between air pollution and IMR during nearly ten years in Tehran, Iran.

Methods

Study design

We obtained air pollution monitoring data over the study period (21 March 2009 through 22 October 2018) from the information of 23 air quality control centers in different areas of Tehran, Iran. For this purpose, the daily measure of the following six pollutants was obtained: particulate matter ≤10μm (PM10), particulate matter<2.5 μm (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O3), and carbon monoxide (CO). The pollutants levels were obtained based on the calculation of their mean them in 23 centers. For the same study period, daily maximum and minimum temperature (°C) and daily relative humidity (%) were obtained from the atmospheric Data Centre, using one weather station in Tehran City. The daily mean temperature was estimated as the mean of the daily maximum and minimum values.

Data on all-cause infant deaths recorded between 2009 and 2018 were obtained from the Office for National Statistics of Iran and mortality registered in the Behesht Zahra Organization (Tehran Main Cemetery). The data were collapsed by date of death to generate a time series of daily infant death counts between 2009 and 2018. Then, based on the causes of death, deaths due to premature birth were considered for the study.

Statistical analysis

Distributed lag linear and non-linear models were applied to investigate the effect of air pollutants, the Air Quality Index (AQI), and Temperature, on infant mortality for the city of Tehran, during the period 2009 to 2018. The analysis was based on the model represented in (13), fitted through a generalized linear model with quasi-Poisson family, with the following terms: natural cubic splines of time with 7 degrees of freedom (df) per year to describe long-time trends and seasonality; indicator variables for day of the week; natural cubic splines with 3 df at equally spaced quantiles for the average of dew point temperature at lag 0–1; linear terms for the average of AQI and other air pollutants at lag 0–1.

Moreover, the effect of mean temperature was investigated through the relationships in the spaces of temperature and lags; we applied a model with natural cubic splines to describe the relationship in each dimension. The maximum lag L was set to 30 days. All the analyses were performed with the software R, version 2.10.1, using the package dlnm.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues have been completely observed by the authors. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the School of Pharmacy and Nursing & Midwifery-Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (ID:IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1398.226).

Results

Study population

A total of 23,206 infant deaths were reported during the study period (2009–2018). Table 1 shows the infant mortality rate according to the cause of death according to the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) for the years 2009 to 2018.

Table 1:

Infant mortality rate according to the cause of death according to the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) for the years 2009 to 2018

| The cause of death | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2815 | 2727 | 2542 | 2326 | 2237 | 2340 | 2444 | 2367 | 2141 | 1267 | 23206 |

| Code 1: Certain infectious or parasitic diseases | 150 | 104 | 157 | 111 | 108 | 144 | 136 | 190 | 171 | 89 | 1360 |

| Code 11: Diseases of the circulatory system | 109 | 163 | 143 | 151 | 179 | 174 | 190 | 171 | 229 | 98 | 1607 |

| Code 12: Diseases of the respiratory system | 148 | 154 | 132 | 150 | 125 | 126 | 211 | 273 | 201 | 100 | 1620 |

| Code 19: Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 1154 | 1171 | 995 | 828 | 709 | 684 | 441 | 220 | 174 | 132 | 6508 |

| Code 20: Developmental anomalies | 148 | 124 | 146 | 154 | 189 | 295 | 463 | 408 | 583 | 347 | 2875 |

| Code21: Symptoms, signs or clinical findings, not elsewhere classified | 542 | 509 | 524 | 449 | 530 | 477 | 500 | 753 | 668 | 428 | 5380 |

| Code 22: Injury, poisoning or certain other consequences of external causes | 445 | 401 | 320 | 409 | 332 | 358 | 406 | 223 | 28 | 18 | 2940 |

Air pollutants

Results of the lag linear model are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1:

The relationship between air pollutants: PM10, PM2.5, O3, CO, SO2, NO2, and AQI and mortality adjusted by temperature in Tehran. The trendline in the center represents Relative Risk (RR) and the dashed line indicates the 95% confidence interval

It shows the relationships between PM10, PM2.5, CO, O3, NO2, SO2, and AQI on mortality adjusted by mean temperature during the 30-lag time. The trend line in the center represents Relative Risk (RR) and the dashed line indicates the 95% confidence interval. The 30-lag curve represents following an increase of 10 ug/m3 in PM10 in an early day of exposure, risk of mortality increased significantly (RR=1.003, 95%CI: 1.001–1.005). The association between other air pollutants and mortality was not statistically significant, overall.

Temperature

The lag non-linear model considers the association between temperatures. An overall picture of the effects of minimum, maximum and average temperatures on mortality adjusted by AQI is provided in Figs. 2–4. Figure 5 shows the trend of RRs by the maximum temperature at specific lags (0, 5, 15, 28) and by lag at specific temperatures, corresponding to −5 °C, 0 °C, 10 °C, and 36 °C of average temperature. Cold temperatures are associated with a longer Infant mortality risk than heat (top right var=−5), but not immediate (lag 30), representing a protective effect at lag 0 (though not statistically significant).

Fig. 2:

3-D plot of RR along mean temperature and lags, with reference at 19 C

Fig. 4:

3-D plot of RR along mean of minimum temperature and lags, with reference at 24 C

Fig. 5:

Trend of RR (outcome) by temperature (var) at specific lags (top left), RR by lag at minimum and maximum of average temperature Reference at 19 °C

Fig. 3:

3-D plot of RR along mean of maximum temperature and lags, with reference at 24 C

At cold temperate, (var=0 and lag 0) risk of infant mortality was significantly higher than reference temperature (19°C) (RR=1.1295, %CI: 1.01–1.25) (plot second top right).

Discussion

Air pollution is a global public health crisis (1). In this study, we evaluated the relationship between air pollution and IMR, the most sensitive indicator of population health, over nearly ten years. The results showed that with an increase of 10 ug/m3 in PM10 in an early day of exposure, the risk of mortality increased significantly.

Similar to the results of the present study, various studies conducted around the world have reported a statistically significant increased rate in the neonate (14), post-neonatal (15) or infant mortality (16) or SIDS mortality (17) for increases in PM10 exposure. Some of studies reported a significant statically increase in the risk of respiratory-related post-neonatal (18) and infant mortality (5) for a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10.

In contrast, one study based on time series analysis in the UK, found no significant association between short-term exposure of PM10 and all infant, neonatal, and post-neonatal mortality (3). PM10 is an international convention for measuring environmental particulate air pollution. Increases in PM10 are associated with exacerbation of airway disease and death from respiratory and cardiovascular causes (19). Another study by evaluating four air pollutants PM10, SO2, O3, NO2 in Tehran showed that considering short-term effects, PM10 had the highest rate of cumulative premature death and respiratory diseases and the highest health impact on the inhabitants of Tehran City (20). There was a direct and significant relationship between PM10 exposure to preterm birth (21) and low birth weight (21–24). One of the most important indicators for determining the health status of a society is birth weight, which is directly related to IMR (25). Moreover, preterm infants are susceptible to many complications (25) and these complications are the leading cause of mortality in children younger than 5 years (26).

In the present study, we found no association between other air pollutants and infant mortality rate, while some studies reported different results. Some studies demonstrated a statically significant increased risk of infant mortality with the increase in PM2.5 exposure (27, 28). Two studies found a statistically significant increased rate in neonatal and post-neonatal mortality for increases in SO2 exposure (14, 29, 30). Some researchers have also reported a significant association between long-term exposure to NO2 and increased risk of infant, neonatal, and post-neonatal mortality (14, 31) or increased rates of SIDS (17, 31, 32).

On the other hand, despite the results on the effects of different air pollutants on infant mortality obtained from different studies around the world, some studies found no statistically significant association between increased exposure of PM10 and other air pollutants with neonatal and Infant Mortality (3, 33–35).

The results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on 14 studies showed a significant increase in infant death with the increase of exposure to air pollutants PM10, PM2.5, and NO2 during either the pregnancy period or the first year of a newborn’s life (36).

Differences in the results of different studies may be related to the difference in the conversion of air pollution concentrations from different regions, differences in exposure rate, and climatic characteristics of the region.

Environmental pollutants affect all age groups. However, fetuses, infants, and children have unique vulnerabilities and sensitivities to the risks of air pollution, especially during fetal development and in their earliest year (1, 6). These increased risks are due to a combination of behavioral, environmental, and physiological factors (1). The underlying biological pathways that link air pollution and infant mortality are largely unknown. Increased exposure to air pollutants can cause the bronchial system to contract, which can impair lung function (37).

Children are one of the most important groups at risk of air pollution (38, 39). These studies focus in particular on the toxic effects of air pollutants on the respiratory system, although the adverse effects of air pollutants on other organs are also important (40).

This difference compared to adults is due to physiological immaturity, incomplete metabolic systems, immature host defenses, the continuing process of lung growth and development, differences in exposure, high rates of infection with respiratory pathogens, longer life expectancy after exposure, and activity patterns that increase exposure to air pollution and lung doses of pollutants (41). Children’s bodies, lungs, and brains are still rapidly developing and maturing, therefore more vulnerable to inflammation and other damage caused by pollutants(1). Children’s airways are narrower compared to adults, they breathe faster than adults and inhale more air per unit time, while the smaller surface area of their lung means that relatively more inspired air reaches the lung, and is, therefore, more polluting (42). This can exacerbate the adverse effects of pollutants in children. On the other hand, due to the immaturity of the respiratory system, the repair of damage to the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract is not done properly (43).

Children spend a lot of time near their mothers while the mothers cook with polluting devices and fuels. They live closer to the ground, where some pollutants reach peak concentrations (1). In addition, children are not able to metabolize, detoxify, and excrete toxins similar to adults, and as a result, the toxins remain in the circulatory system longer and cause more damage to the organs (44)

The results of the present study showed that colder temperatures are associated with a higher risk of infant mortality than warmer ones. Similar to our study results, Karlsson et al. (2020) in Sweden also showed that neonate mortality is higher in winter and the risk of neonate mortality decreases with increasing temperature on the day of birth (45). The response to cold in the mother can lead to increased blood viscosity and vasoconstriction (46), and these lead to reduced blood flow to the placenta (47). Besides, the cold leads to an increase in stress hormones (48), and these hormones can lead to preterm labor (49). Prematurity is an important risk factor for infant mortality.

However, this study also had some limitations. We did not evaluate the synergistic effects of pollutants. The second limitation is the possibility of incomplete recording of air pollutants by sensors and the inherent limitations of the environmental study, as well as the unregistered infant. Given that many factors can affect the health and mortality of infants, the lack of control of these factors in the present study is another limitation of this study.

Therefore, it is suggested that studies that are more comprehensive be conducted in different seasons of the year in different cities with different levels of air pollution. Future studies are also recommended to understand possible mechanical explanations for the role of air pollution in neonatal mortality and how neonatal pollution is reduced. Further studies are needed to assess any long-term effects of air pollution on children.

Conclusion

Our study results show the adverse effects of PM10 exposure on neonatal mortality in Tehran, Iran. Air pollution, especially in metropolises such as Tehran, by considering more sources of air pollution, can affect Infant mortality. The results from this study contribute to very limited data in the scientific literature on adverse effects of air pollution for high exposure settings typical in developing countries. Accordingly, a steady decline in PM10 levels in Tehran may have greater health benefits for infant’s health and reducing IMR.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Air Quality Control Centers and Behesht Zahra Organization for providing us with the data needed for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO (2018). Air pollution and child health: prescribing clean air: summary. World Health Organization, available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CED-PHE-18-01.

- 2.Dadvand P, Parker J, Bell ML, et al. (2013). Maternal exposure to particulate air pollution and term birth weight: a multi-country evaluation of effect and heterogeneity. Environ Health Perspect, 121:267–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajat S, Armstrong B, Wilkinson P, Busby A, Dolk H. (2007). Outdoor air pollution and infant mortality: analysis of daily time-series data in 10 English cities. J Epidemiol Community Health, 61:719–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kampa M, Castanas E. (2008). Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut, 151:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gouveia N, Junger WL, Romieu I, et al. (2018). Effects of air pollution on infant and children respiratory mortality in four large Latin-American cities. Environ Pollut, 232:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen EK-C, Zmirou-Navier D, Padilla C, Deguen S. (2014). Effects of air pollution on the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 11:7642–7668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perera FP. (2017). Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ Health Perspect, 125:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. (2007). Ambient air pollution and low birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environ Health Perspect, 115:1118–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Cao H, Sun D, et al. (2019). Associations between ambient air pollution and mortality from all causes, pneumonia, and congenital heart diseases among children aged under 5 years in Beijing, China: A population-based time series study. Environ Res, 108531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dube L, Taha M, Asefa H. (2013). Determinants of infant mortality in community of Gilgel Gibe Field Research Center, Southwest Ethiopia: a matched case control study. BMC Public Health, 13:401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel AP, Jagai JS, Messer LC, et al. (2018). Associations between environmental quality and infant mortality in the United States, 2000–2005. Arch Public Health, 76:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loury R. (2017). WHO: Environmental pollution causes one in four infant deaths. (ed)^(eds) Journal de l’environnement, available from: https://www.euractiv.com/section/development-policy/news/who-environmental-pollution-causes-one-in-four-infant-deaths/

- 13.Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Kenward MG. (2010). Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat Med, 29:2224–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotecha S, Watkins WJ, Lowe J, Grigg J, Kotecha S. (2019). Effects of air pollution on all cause neonatal and post-neonatal mortality: population-based study. Eur Respir J, 54 PA297. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbajal-Arroyo L, Miranda-Soberanis V, Medina-Ramón M, et al. (2011). Effect of PM10 and O3 on infant mortality among residents in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area: a case-crossover analysis, 1997–2005. J Epidemiol Community Health, 65:715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arceo E, Hanna R, Oliva P. (2016). Does the Effect of Pollution on Infant Mortality Differ Between Developing and Developed Countries? Evidence from Mexico City. Econ J, 126:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litchfield IJ, Ayres JG, Jaakkola JJ, Mohammed NI. (2018). Is ambient air pollution associated with onset of sudden infant death syndrome: a case-crossover study in the UK. BMJ Open, 8:e018341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodruff TJ, Darrow LA, Parker JD. (2008). Air pollution and postneonatal infant mortality in the United States, 1999–2002. Environ Health Perspect, 116:110–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donaldson K, MacNee W. (2001). Potential mechanisms of adverse pulmonary and cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution (PM10). Int J Hyg Environ Health, 203:411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naddafi K, Hassanvand MS, Yunesian M, et al. (2012). Health impact assessment of air pollution in megacity of Tehran, Iran. Iranian J Environ Health Sci Eng, 9:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Xu J, Chen D, Sun P, Ma X. (2019). The association between air pollution and preterm birth and low birth weight in Guangdong, China. BMC Public Health, 19:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarizadeh R, Dastoorpoor M, Goudarzi G, Simbar M. (2020). The association between air pollution and low birth weight and preterm labor in Ahvaz, Iran. Int J Womens Health, 12:313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannini N, Schwartz L, Cipriani S, et al. (2018). Particulate matter (PM10) exposure, birth and fetal-placental weight and umbilical arterial pH: results from a prospective study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 31:651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira G, Bell ML, Lee HJ, Koutrakis P, Belanger K. (2014). Sources of fine particulate matter and risk of preterm birth in Connecticut, 2000–2006: a longitudinal study. Environ Health Perspect, 122:1117–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med, 39:263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhe LM, McClure EM, Nigussie AK, et al. (2019). Major causes of death in preterm infants in selected hospitals in Ethiopia (SIP): a prospective, cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Glob health, 7:e1130–e1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung EM, Kim KN, Park H, et al. (2020). Association between prenatal exposure to PM2.5 and the increased risk of specified infant mortality in South Korea. Environ Int, 144:105997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Son J-Y, Lee HJ, Koutrakis P, Bell ML. (2017). Pregnancy and Lifetime Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and Infant Mortality in Massachusetts, 2001–2007. Am J Epidemiol, 186:1268–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Spix C, et al. (1997). Short term effects of ambient sulphur dioxide and particulate matter on mortality in 12 European cities: results from time series data from the APHEA project. BMJ, 314:1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CA, Pereira LA, Nishioka DC, Conceicao GM, Braga AL, Saldiva PH. (2004). Air pollution and neonatal deaths in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res, 37:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritz B, Wilhelm M, Zhao Y. (2006). Air pollution and infant death in southern California, 1989–2000. Pediatrics, 118:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klonoff-Cohen H, Lam P, Lewis A. (2005). Outdoor carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child, 90:750–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipfert FW, Zhang J, Wyzga RE. (2000). Infant mortality and air pollution: a comprehensive analysis of US data for 1990. J Air Waste Manag Assoc, 50:1350–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romieu I, Ramírez-Aguilar M, et al. (2004). Infant mortality and air pollution: modifying effect by social class. J Occup Environ Med, 46:1210–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Son JY, Cho YS, Lee JT. (2008). Effects of air pollution on postneonatal infant mortality among firstborn infants in Seoul, Korea: case-crossover and time-series analyses. Arch Environ Occup Health, 63:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kihal-Talantikite W, Marchetta GP. (2020). Infant Mortality Related to NO(2) and PM Exposure: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17:2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chay KY, Greenstone M. (2003). The impact of air pollution on infant mortality: evidence from geographic variation in pollution shocks induced by a recession. Q J Econ, 118:1121–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buka I, Koranteng S, Osornio-Vargas AR. (2006). The effects of air pollution on the health of children. Paediatr Child Health, 11:513–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Currie J, Neidell M, Schmieder JF. (2009). Air pollution and infant health: Lessons from New Jersey. J Health Econ, 28:688–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kulkarni N, Grigg J. (2008). Effect of air pollution on children. Paediatr Child Health, 18:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ballester F, Estarlich M, Iñiguez C, et al. (2010). Air pollution exposure during pregnancy and reduced birth size: a prospective birth cohort study in Valencia, Spain. Environ Health, 9:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makri A, Stilianakis NI. (2008). Vulnerability to air pollution health effects. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 211:326–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plopper C, Buckpitt A, Evans M, et al. (2001). Factors modulating the epithelial response to toxicants in tracheobronchial airways. Toxicology, 160:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rom WN. (2011). Environmental policy and public health: air pollution, global climate change, and wilderness. ed. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karlsson L, Lundevaller EH, Schumann B. (2020). Neonatal Mortality and Temperature in Two Northern Swedish Rural Parishes, 1860–1899—The Significance of Ethnicity and Gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17:1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keatinge W, Donaldson G. (2004). The impact of global warming on health and mortality. South Med J, 97:1093–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vorherr H. (1982). Factors influencing fetal growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 142:577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canals M, Figueroa D, Miranda J, Sabat P. (2009). Effect of gestational and postnatal environmental temperature on metabolic rate in the altricial rodent, Phyllotis darwini. J Therm Biol, 34:310–314. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandman CA, Glynn L, Schetter CD, et al. (2006). Elevated maternal cortisol early in pregnancy predicts third trimester levels of placental corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH): priming the placental clock. Peptides, 27:1457–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]