Abstract

Salt marshes are highly dynamic, biologically diverse ecosystems with a broad range of ecological functions. We investigated the endophytic bacterial community of surface sterilized seeds of the holoparasitic Cistanche phelypaea growing in coastal salt marshes of the Iberian Peninsula in Portugal. C. phelypaea is the only representative of the genus Cistanche that was reported in such habitat. Using high-throughput sequencing methods, 23 bacterial phyla and 263 different OTUs on genus level were found. Bacterial strains belonging to phyla Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota were dominating. Also some newly classified or undiscovered bacterial phyla, unclassified and unexplored taxonomic groups, symbiotic Archaea groups inhabited the C. phelypaea seeds. γ-Proteobacteria was the most diverse phylogenetic group. Sixty-three bacterial strains belonging to Bacilli, Actinomycetes, α-, γ- and β-Proteobacteria and unclassified bacteria were isolated. We also investigated the in vitro PGP traits and salt tolerance of the isolates. Among the Actinobacteria, Micromonospora spp. showed the most promising endophytes in the seeds. Taken together, the results indicated that the seeds were inhabited by halotolerant bacterial strains that may play a role in mitigating the adverse effects of salt stress on the host plant. In future research, these bacteria should be assessed as potential sources of novel and unique bioactive compounds or as novel bacterial species.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Plant symbiosis

Introduction

Due to their high biological productivity, contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions and involvement in nutrient cycling, wetlands are considered as highly valuable ecosystems. Salt marshes are unique wetland systems characterized by harsh environmental conditions including periodic flooding and high salinity levels, nutrient levels, herbivore densities and also sea level rise. They harbor a halophilic vegetation1,2. These ecosystems are characterized by low numbers of dominating macrophytes, with predictable acidification and high salinity in the environment3. The plants growing in coastal salt marshes are an underexplored source of plant associated bacteria having a great potential to antimicrobial, enzymatic, plant growth promoting (PGP) and biodegrading traits3. In such salt marshes, the holoparasitic Cistanche phelypaea (Orobanchaceae) has our particular interest. The genus Cistanche includes about 25 species, and is found mainly in arid, semi-arid and halophytic habitats across Eurasia and North Africa4. Most species belonging to this genus require special environmental conditions for growth, i.e. extreme arid climate, poor and impoverished soils, large temperature fluctuations, intensive sunshine and low annual precipitation5. The obligate root parasite C. phelypaea has a limited area of distribution and is endemic to salt marshes at the Atlantic coast of Portugal and Spain6–8.

During evolution obligate root holoparasitic Orobanchaceae were subject to multiple modifications, e.g. loss of the roots and plastids9,10, and the production of large numbers of extremely small seeds which remain viable in the soil for many years11,12. The main storage material in the seeds of holoparasitic Orobanchaceae are lipids13. The crucial stages of the lifecycle of holoparasitic plants are seed germination, reaching the desirable host, gaining access to nutrients, and development of the new generation14. When host signals are received, seeds start germinating. Subsequently, the germinating seeds develop specialized organs called haustoria, that penetrate the host vascular system. Through such haustoria holoparasitic seeds can reach the water and nutrients of the host15,16.

In host-parasite interactions, the extreme conditions of salt marshes are challenging for both partners. C. phelypaea is parasitizing on roots of halophytic plants6. Thus, the holoparasite should possess defense mechanisms against the abiotic conditions in the saline soil, the high osmotic pressure of the soil solution, and must be able to cope with the salt tolerant nature of the host plant as well17. The parasitic plants are affected by salinity stress both directly and undirectedly. Although, the root parasites have very limited soil contact, they are indirectly affected by salt stress through the metabolism of their host. In natural habitats, most of the Cistanche species prefer their hosts growing under stress conditions, due to the high contents of nutrients that hosts accumulate in such habitats18. Salt stress inhibits the germination of C. phelypaea seeds directly and through changes in host signaling that strongly depends on the concentration of germination stimulants. The parasite response mechanisms to salinity are still unclear19. It was found that some Orobanchaceae accumulate high amounts of polyols20. The half-parasite Viscum album (mistletoe), parasitizing in trees, was reported to actively absorb polyols from the host and develop a host-specific polyol profile21. At higher salt concentrations, Cuscuta campestris, parasitizing on Arabidopsis, accumulated l-proline and decreased in this way the salt concentrations in the host compared to non-infected plants22.

Plant associated bacteria have a key role in plant fitness. They may survive in harsh abiotic conditions and stimulate the host metabolism in response to abiotic stresses23. Like their host plants, these microorganisms are strongly influenced by the salinity of the environment24. It was suggested that, in harsh habitats, the endophytes colonizing plant seeds have survival strategies that are different from endophytes of plants growing on less demanding soils and that they might be able to survive in seeds for a long period of time25,26. Endophytic bacteria often possess PGP traits like e.g. auxin production27. It has been proven that vegetation type, plant species, carbon and nutrient availability, soil type and structure, abiotic parameters of soil, particularly pH, as well as soil moisture have a direct impact on the diversity of microorganisms colonizing the roots28,29. These bacteria are transferred from the roots to other parts of the plant and reach the seeds that function as a vector from one generation to the next30,31. As many authors mentioned, the seeds of plants, including the holoparasitic C. armena, can harbor diverse endophytic bacterial communities adapted to survive in harsh abiotic conditions23,26,32. The most unique properties of the seed-associated bacterial endophytes are their vertical transmission and preservation in seeds for a long period of time30,33,34. Those are important capacities for the assemblage and establishment of the endomicrobiome of consecutive seed generations that consistently show similar endophytic communities with prominent dominating groups34.

Although, environmental and anthropogenic factors, such as oil spills, storms or high levels of eutrophication are challenging for organisms in natural salt marshes, the bacterial communities are generally quite resistant to extensive compositional changes35. On the other hand, differences between the composition of the microbial communities in the different zones of salt marshes have been reported2. Dominating plant populations, soil organic matter, phosphorous and nitrogen concentrations were observed to influence the succession of the bacterial communities36. Considering that the root parasite is fully dependent on its host plant, the microbial diversity of the holoparasite also depends on its host species and individual plant characteristics37.

The plant associated endophytic microbial diversity has been particularly well-studied in terrestrial ecosystems. However, the diversity and biological activity of wetland microbial communities is still highly underexplored and is often focusing on wastewater treatment1,38. From the endosphere of mangrove propagules23 and plant species growing in saline wetland ecosystems, various bacterial phyla have been isolated39,40. The four main bacterial phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes were identified as dominant phyla in both, terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems23,28,38,41. These bacterial phyla and several genera like Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Micrococcus, Rhizobium, Staphylococcus are often associated with seeds across a wide range of plant taxa33,42–44. These endophytes possess a considerable tolerance to a wide range of abiotic stresses typical for coastal environments, indicating their adaptive ability to this particular habitat23.

Special and extreme environments are rich in rare Actinobacteria and novel species. Rare Actinobacteria are usually difficult to isolate mainly due to their particular growth requirements and/or unknown culture conditions45. Actinobacteria from wetland ecosystems have a special interest. They produce structurally diverse bioactive components, like enzymes, antibiotics, antitumor and immune regulatory agents45–47. They can also play an important role as symbionts in plant-associated microbial communities48. A large diversity of endophytic Actinobacteria was identified in several plants growing in mangrove and salt marshes in various locations in India (Bhitarkanika region) and China (Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Zhanjiang Mangrove Forest National Nature Reserve, Beilum Estuary National Nature Reserve). The most abundant endophytes in wetland ecosystems belong to the Streptomyces, Nocardiopsis, Pseudonocardia, Saccharopolyspora, Agrococcus, and Micromonospora49–52. However, isolation, diversity and biological activity of endophytic Actinobacteria from coastal salt marsh ecosystems still is not intensively explored, even though such environments seem to harbor unique and phylogenetically diverse endophytes53.

To date, there exist only a few studies concerning seed endophytic bacterial communities of holoparasitic plant seeds32,54,55. The endophytic bacterial community (culturable and unculturable) in ripe seeds of C. phelypaea growing in coastal salt marshes has not yet been investigated. There exist a limited number of studies on the biology and ecology of C. phelypaea. Most works concern the distribution, biomass, host range, the allelopathic potential, and the ecophysiological interactions between C. phelypaea and its host6,7,17,56–58.

The aim of our study was to investigate the diversity of the endophytic bacterial community of surface sterilized seeds of C. phelypaea growing in Iberian coastal salt marshes. We also studied the in vitro PGP traits of the bacterial isolates, such as production of indole, organic acids and siderophores and the ACC deaminase activity.

Results

Seed endophytic bacterial community composition

We used high-throughput sequencing methods to investigate the diversity and composition of the bacterial endophytic community from seeds of C. phelypaea. Alpha diversity indices (Shannon–Wiener biodiversity index, Chao1 and Simpson indexes) were 3.12, 165, 0.868 respectively with P value 0.05. A total of 263 different Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU)s at genus level were found from 23 phyla (> 0.1%). Unclassified and unexplored taxonomic groups were found as well.

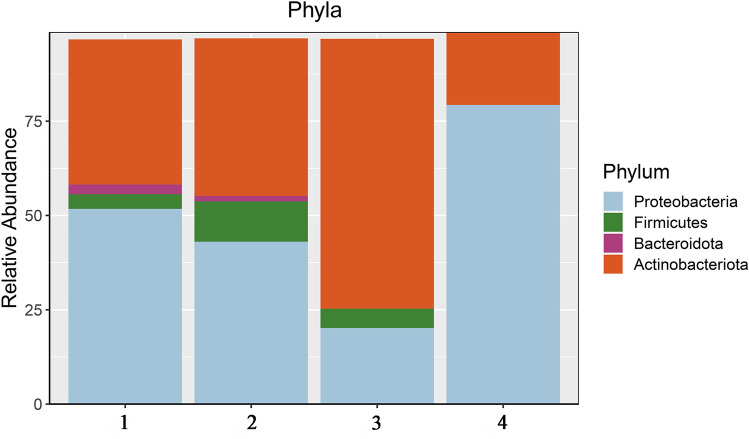

Proteobacteria (48.8%) and Actinobacteriota (43.0%) were the predominating phyla in four replicates. Bacteroidetes (1.2%) and Firmicutes (5.2%) were observed only in two and three out of the four replicates respectively (Fig. 1). Other phyla represented less than 1%. Besides well-known bacterial groups, the seeds were also colonized by newly classified or unknown ones. Among those was the recently proposed bacterial candidate phylum Entotheonellaeota. The other special phyla detected in the C. phelypaea seeds were the newly defined superphylum Patescibacteria59, and the phyla Armatimonadetes60 and Desulfobacteriota proposed by phyl. nov.61. The C. phelypaea seeds were also inhabited by symbiotic Archaea belonging to the Nanoarchaeota, Halobacterota and Crenarchaeota.

Figure 1.

Relative abundance (> 1%) of dominating phyla of endophytic bacteria in four DNA replicates (1, 2, 3, 4) of Cistanche phelypaea seeds.

From the three classes of Proteobacteria, the γ-Proteobacteria were the most diverse compared to α- and β-Proteobacteria. Unclassified Proteobacteria at different taxonomic levels were found as well. Within the α-Proteobacteria, the orders Sphingomonadales and Rhizobiales were found in much higher abundances. At the order level γ-Proteobacteria was dominated by Enterobacterales and Pseudomonadales, and β-Proteobacteria were represented by Burkholderiales and Neisseriales (Table 1). The phylum Actinobacteriota was mainly represented by the orders Propionibacteriales with Cutibacterium at genus level, and Micromonosporales with the genera Micromonospora and Microbacterium. Besides well-known Actinobacteria, about 8.7% rare Actinobacteria62 were found: Cryptosporangium, Actinokineospora, Pseudonocardia, Actinoplanes, Kineosporia, and Nocardia. Finally, the third dominating phylum identified in the examined seeds were the Firmicutes with as most important orders the Lactobacillales and the Staphylococcales, with the genera Streptococcus and Staphylococcus respectively. From the order Bacillales, the families Bacillaceae and Planococcaceae were represented. More detailed information about dominating endophytic bacteria at different taxonomic levels is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cumulative list of dominating endophytic bacteria in the seeds of Cistanche phelypaea and their taxonomic information.

| Phyla | Classes | Orders | Families | Genera* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteriota | Actinobacteria | Micromonosporale | Microbacteriaceae | Micromonospora |

| Microbacterium | ||||

| Propionibacteriales | Propionibacteriaceae | Cutibacterium | ||

| Proteobacteria | α-Proteobacteria | Sphingomonadales | Sphingomonadaceae | Sphingomonas |

| Rhizobiales | Rhizobiaceae | Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium; NA | ||

| β-Proteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Burkholderiaceae | Ralstonia | |

| Neisseriales | Neisseriaceae | NA | ||

| γ-Proteobacteria | Enterobacterales | Morganellaceae | Proteus | |

| Aeromonadaceae | Aeromonas | |||

| Shewanellaceae | Shewanella | |||

| Pseudomonadales | Pseudomonadaceae | Pseudomonas | ||

| NA | ||||

| Moraxellaceae | Acinetobacter | |||

| Enhydrobacter | ||||

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus |

| Aerococcaceae | Abiotrophia | |||

| Staphylococcales | Staphylococcaceae | Staphylococcus | ||

| Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | ||

| Planococcaceae | NA | |||

| Unclassified groups at high taxonomic levels | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Only taxonomic groups with an abundance > 10% are listed.

*Other genera were represented at abundances lower than 10% of the total seed endophytic community.

Diversity and in vitro characterization of PGP bacteria isolated from the surface-sterile seeds

In order to obtain as complete as possible overview of the culturable members of the endophytic community of C. phelypaea seeds, different culture media were chosen. In total 63 bacterial strains belonging to Firmicutes (66.7%), Actinobacteriota (15.9%), α-, γ- and β-Proteobacteria (14.3%) and unclassified bacteria (3.2%) were picked up from the 1/869 rich, Flour1, PDA, R2A, 284, and YEDC media and subsequently identified (Table 2). The morphological characteristics of bacterial colonies and more detailed taxonomic information about isolated bacterial strains were presented in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Table 2.

Cumulative list of isolated culturable endophytic bacteria in the seeds of Cistanche phelypaea and their taxonomic information.

| Count of isolated bacteria % | Phyla | Classes | Orders | Genera |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66.7 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Bacillus |

| Paenibacillus | ||||

| Peribacillus | ||||

| 15.9 | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetia | Micromonosporales | Micromonospora |

| Micrococcales | Brevibacterium | |||

| Plantibacter | ||||

| Janibacter | ||||

| 3.2 | Proteobacteria | α-Proteobacteria | Sphingomonadales | Sphingomonas |

| Hyphomicrobiales | Microvirga | |||

| β-Proteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Ralstonia | ||

| 9.5 | ||||

| 1.6 | γ-Proteobacteria | Xanthomonadales | Stenotrophomonas | |

| 3.2 | Unclassified | Unclassified | Unclassified | Unclassified |

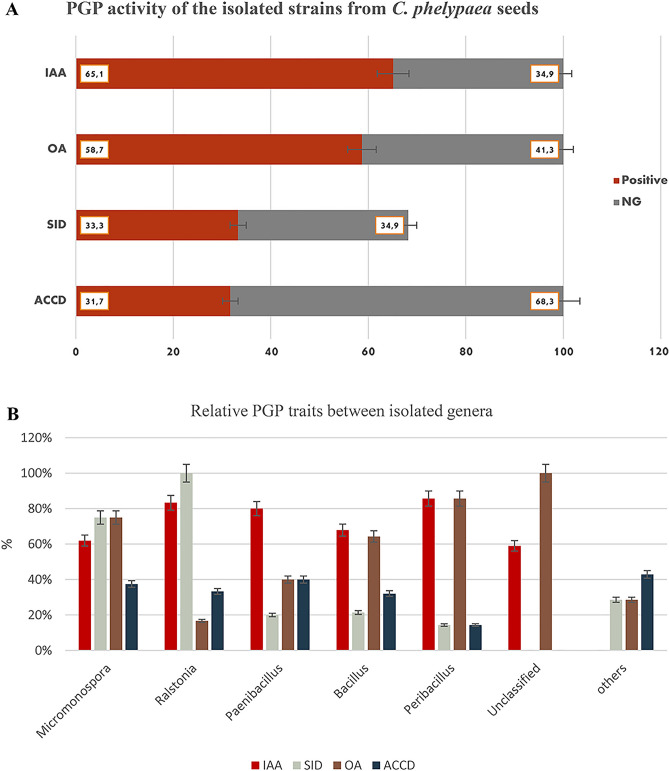

The isolated strains were also tested in vitro for various Plant Growth Promoting (PGP) properties which are presented in Fig. 2. Respectively, 41 (65.1%) and 37 (58.7%) of all isolated strains tested positive for the production of indole (IAA) and organic acids (OA) (Fig. 2a); among those the strains belonging to the genera Ralstonia, Paenibacillus, Peribacillus demonstrated the highest IAA production (Fig. 2b). Meanwhile, the strains belonging to Micromonospora, Peribacillus and unclassified strains demonstrated more positive responses for the production of organic acids (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

PGP activity of the strains isolated from the Cistanche phelypaea seeds. The figure (A) shows the IAA, ACCD, siderophores and organic acids’ production ability. positive-red, negative-gray. (B) Figure shows the IAA (red), ACCD (blue), siderophores (gray) and organic acids (light brown).

For both, ACC-deaminase and siderophore production, respectively 20 (31.7%) and 21 (33.3%) of the investigated strains tested positive (Fig. 2a); among those 75% of the Micromonospora and 100% of the Ralstonia were positive for production of siderophores. In case of ACC deaminase, most positive responses were found for strains belonging to Micromonospora, Ralstonia and Paenibacillus (Fig. 2b). Among the β-Proteobacteria, Ralstonia spp. demonstrated the highest number of positive responses for siderophore production. Among the Actinobacteria, Micromonospora spp. demonstrated equally high positive responses for all tested PGP traits (Fig. 2b). Detailed information about the in vitro PGP traits is presented in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Salt tolerance of cultivated bacteria

In order to confirm the salt tolerance of the isolated strains the modified Brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth63 was used. After 7–10 days observation all tested bacterial strains demonstrated salt tolerance (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Discussion

Salt marshes are natural habitats for many unique salt-tolerant plants64. Among these, the holoparasitic C. phelypaea can be highlighted. The heterotrophic lifestyle of parasitic plants was leading to several morphological, physiological and molecular adaptations with unique properties that make them an exciting group for study; the production of large numbers of very small seeds and the very specific conditions of germination are examples. Besides, they have significant effects on the ecosystems in which they occur15. The importance of wetlands, particularly salt marshes and the limited knowledge concerning the microbiology of such systems form the incentive for the current paper, focusing on the seed-associated endophytic bacterial community of the obligate root parasite C. phelypaea that is parasitizing on the roots of halophytic plant species6.

In a recent study32 we examined the bacterial seed endomicrobiome of another species from the genus Cistanche, C. armena, an endemic species growing in saline and arid habitats in Armenia. The seed endophytic bacterial community of C. armena is less diverse compared to that of C. phelypaea and consists mainly of spore forming, halophytic bacteria, with the Firmicutes as the predominating phylum (60.4%) (Table 3). From the seeds of C. armena, 10 bacterial phyla and 256 genera were identified. The structure and diversity of this endophytic bacterial community is related to the natural habitat of their host plant32.

Table 3.

Comparison of dominant bacterial phyla (> 1%) in seeds of Cistanche armena and C. phelypaea.

| Proteobacteria (%) | Firmicutes (%) | Actinobacteriota (%) | Bacterioitoda (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. armena32 | 32.9 | 60.5 | 6.5 | 1.0 |

| C. phelypaea | 48.8 | 5.2 | 42.8 | 1.2 |

The predominating phyla are indicated in bold.

In the present study we describe the structure and diversity of the endophytic bacterial community of seeds from an endemic C. phelypaea population growing in coastal salt marshes in Portugal. Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are well represented (> 1%) in surface sterile seeds (Fig. 1). Corresponding results were reported for the seeds of other holoparasitic Orobanchaceae species, C. armena32 and Phelypanche ramosa54.

Besides commonly known bacterial groups, the seeds C. phelypaea are also colonized by newly classified or unexplored bacterial phyla that have not been reported in such seeds before. Among these are Entotheonellaeota which, until now, were found mainly associated with marine sponges. Bacteria isolated from the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei Y are uncultured filamentous bacteria “Candidatus Entotheonella factor” and “Candidatus Entotheonella gemina”. Whole genome sequencing of Ca. Entotheonella demonstrated an extraordinarily rich genomic potential for the production of bioactive natural products with unique structures, uncommon biosynthetic enzymology and largely unknown properties65. Another interesting newly defined superphylum Patescibacteria has been found in groundwater, sediments, lakes, and other aquatic environments and was found associated with plants as well59,66. The role of Patescibacteria in plants is still unclear, although they have been discovered inside of tissues of different plants, in plant associated soils and in degrading plant biomass60,66. The phylum Armatimonadetes is assumed to harbor strains that are widely involved in degradation of plant material, substances based on polysaccharides60.

With 48.8%, the phylum Proteobacteria is the most abundant one in the seeds of C. phelypaea Fig. 1, Table 3). In seeds of C. armena Firmicutes were dominating (60.4%), followed by Proteobacteria with 32.9% (Table 3). In seeds of C. phelypaea, among the Proteobacteria, the γ-Proteobacteria were more diverse compared to α- and β-Proteobacteria (Table 1). In comparison, in C. armena seeds were only abundance by γ-Proteobacteria with as dominating orders Xanthomonadales, Pseudomonadales and Enterobacterales32. The dominating γ-Proteobacteria in seeds of C. phelypaea were Pseudomonadales and Enterobacterales. At family level, Morganellaceae, Aeromonadaceae, Shewanellaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Moraxellaceae were the most abundant (Table 1). Classes of Proteobacteria showed diverse distribution tendencies in different ecosystems. In sediments of marine wetland ecosystems, a wide distribution of γ-Proteobacteria has been reported, and most of them seemed involved in sulfur reduction67. However, a high abundance of α- and β-Proteobacteria appeared in freshwater sediments; this should be correlated with pH and nutrients68.

The second most dominating bacterial phylum in seeds of C. phelypaea was the Actinobacteriota, with a more or less similar abundance as the Proteobacteria (43.0% against 48.8%). This is different from the seeds of C. armena in which Actinobacteriota represented only 6.5% (Table 3). The abundance of this phylum in the examined seeds is not unexpected, taking into account the habitat in which C. phelypaea is growing. Actinobacteriota indeed were reported more often as the most characteristic phylum in wetland ecosystems1,3,45,47,48. Until today, the community structure, diversity, biological activities and mechanisms of environmental adaptation of Actinobacteria to special and extreme environments have been poorly studied compared to more moderate and terrestrial environments69. In seeds of C. phelypaea, the most abundant genus of the Actinobacteriota was Micromonospora (38.1%). The genera Microbacterium and Curtobacterium also were dominating genera in seeds of C. armena growing in a saline, extremely arid environment in Armenia32. It seems that Curtobacterium has an overall distribution and is present in both, wet and arid ecosystems. Many studies mentioned Curtobacterium being a pathogen of economically important plants70. Moreover, this genus is known to harbor a highly diverse genomic potential for the degradation of carbohydrates, particularly with regard to structural polysaccharides71.

The seeds of C. phelypaea are colonized by rare Actinobacteria as well: Actinoplanes, Actinokineospora, Cryptosporangium, Kineosporia, Nocardia, Pseudonocardia. These bacteria are relatively difficult to isolate and cultivate in vitro due to difficulties in mimicking the conditions of their natural habitats. Rare Actinobacteria were isolated from different environments: the deep ocean, deserts, mangroves, plants, caves, volcanic rocks, and stones, which illustrates their wide distribution in the biosphere72. As reported by several authors, such bacteria are a potential source of novel bioactive compounds. Thus, it is essential to enhance our knowledge about their diversity and distribution in the environment46,60.

In case of C. armena seeds, Firmicutes was the predominating phylum with a total abundance of 60.5% (Table 3). The isolated Firmicutes belonged to the genera Paenibacillus (28%), Bacillus (41.9%) and some other genera (11.8%)32. Using a range of different growth media allowed us to isolate and cultivate a quite high diversity of bacterial strains from surface sterilized seeds of C. phelypaea (Table 2). Even though the total abundance of Firmicutes in seeds of C. phelypaea was quite low (5.2%), a majority of the cultivable bacterial strains belonged to this phylum (66.7%), followed by Actinobacteriota (15.9%), α-, γ- and β-Proteobacteria (14.3%) and unclassified bacteria (3.2%) (Tables 2, 3).

The potential PGP traits and salt tolerance of 63 isolated bacterial strains were examined (Fig. 2). It is often claimed that such PGP traits, e.g. production of siderophores, ACC deaminase, salicylic acid, and phytohormones such as auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, and abscisic acid are part of the mechanisms that assist plants to cope with abiotic stresses73–75.

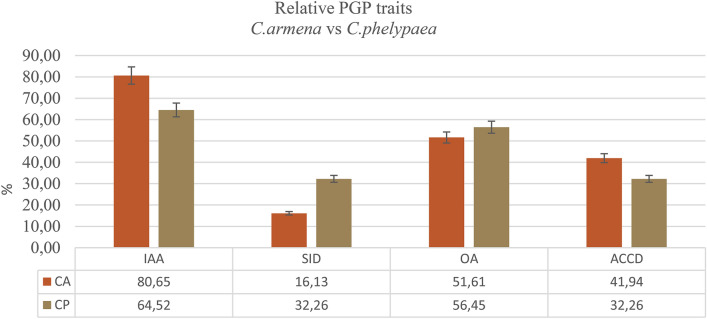

Based on in vitro tests, the selected bacterial isolates seem to possess several plant growth-promoting traits. 58.7% of the isolated strains belonging to various genera produced organic acids (OA), and also 65.1% showed able to produce IAA (Fig. 2a). Among those bacterial strains belonging to genera Ralstonia and Peribacillus showed the highest number of positive responses in the in vitro IAA production. In case of organic acids, the highest numbers of positive responses were found among Micromonospora, Peribacillus and Unclassified bacteria (Fig. 2b). Production of IAA and organic acids by many of the seed endophytes originating from coastal salt marshes (30–35% salt concentration) could be expected, since the seed endophytes isolated from C. armena from arid and saline habitats, also demonstrated high levels of IAA and organic acids production32. In the present study, 65.1% and 58.7% of isolates produce IAA and organic acids, respectively. Meanwhile, Petrosyan et al.32 demonstrated that most of bacterial strains isolated from the surface sterilized seeds of C.armena also could produce IAA (80.7%) and organic acids 51.6% (Fig. 3). Numerous studies have demonstrated that IAA-producing halotolerant bacteria increase the tolerance of plants to saline conditions. Organic acids production by rhizosphere microorganisms is one of the mechanisms to solubilize phosphorus (P) included in insoluble mineral compounds in soils76. Altogether, the seeds of both Cistanche species are inhabited by halotolerant bacteria that may have a role in mitigating the adverse effects of salt stress in the holoparasitic plant. However, it is still not clear if the PGP traits of these bacteria are beneficial only for the holoparasite either also for its host plant. It also remains unclear if the PGP capacities of seed endophytes may protect the embryo of the holoparasite against salt stress.

Figure 3.

PGP traits of endophytic bacterial strains (%) isolated from the surface sterile seeds of Cistanche armena and C. phelypaea.

ACC deaminase capacity is another important trait of PGP endophytes. Many halophytic plants (Salicornia europaea, Halimione portulacoides, Prosopis strombulifera and Limonium sinense) are colonized by endophytes with ACC deaminase capacity77. ACC-deaminase can lower ethylene production under salt stress. Indeed, endophytes with ACC-deaminase capacity convert ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, the immediate precursor of ethylene in plants) into a-ketobutyrate and ammonia which helps the plants to reduce the negative effects of salinity stress on root development77. The major consequences of saline stress are nutrient imbalances and negative effects on plant physiology in general. Siderophores are high affinity iron-chelating compounds. Iron is a micronutrient, essential for plant growth and development, since it is an essential co-factor for a variety of reactions in plant cell metabolism and Fe-requiring enzymes. It is part of several metalloenzymes involved in photosynthesis and respiration. In saline soils, the bioavailability of Fe to plants is low. The role of microbial siderophores in Fe supply to plants and on the mitigation of saline stress in crop growth is well documented78. Respectively 33.3% and 31.7% of the isolated bacterial strains tested positive for siderophore and ACC deaminase production (Fig. 2a). Compared to C. armena that 16.1% were positive for siderophore and 42% scoped to positive for ACC deaminase (Fig. 3). Most positive responses were observed for Actinomycetia and β-Proteobacteria. It seems that β-Proteobacteria with Ralstonia spp. have a high siderophore producing capacity(Fig. 2b). Sphingomonas spp. (α-Proteobacteria) demonstrated the lowest level of positive responses for all in vitro tested PGP traits. Quite similar outcomes were observed for production of indole and organic acids. Also similar numbers of endophytes scored positive for ACC-deaminase and siderophore production (Fig. 2a). Among the Actinobacteria, Micromonospora spp. demonstrated the most positive responses for the in vitro tested PGP traits and thus might be considered as potentially the most favorable endophytes in C. phelypaea seeds. Janibacter strains, also belonging to the Micrococcales scored negative for all tested PGP assays (Supplementary Table S1).

Conclusion

The holoparasitic C. phelypaea, which is parasitizing halophytic host plants, is the only representative of the genus Cistanche that is found in coastal salt marshes in Portugal. We explored the seed endophytic bacterial community of this holoparasite. We succeeded to isolate 63 bacterial strains, whilst using Illumina paired-end sequencing 263 different bacterial genera from 23 bacterial phyla were identified as seed endophytes of C. phelypaea. The 63 cultivable strains appeared to be salt tolerant and to possess plant growth-promoting traits like production of organic acids, IAA, siderophores and ACC deaminase. The genus Micromonospora harbored the most beneficial bacteria. These halotolerant bacteria have potential to mitigate the adverse effects of salt stress in the holoparasite. Possibly, they may also protect the embryo of the holoparasite against salt stress and maintain the seeds a long time viable. However, to confirm this, further studies concerning the beneficial effects of PGP seed endophytes on the holoparasite are required. In addition, the seeds of C. phelypaea represent and underexplored reservoir of diverse and novel endophytic Actinobacteria that may be of potential interest in the discovery of new bioactive compounds.

Materials and methods

Site description and seed sampling

The holoparasitic Cistanche phelypaea (L.) Cout. (Orobanchaceae) is found at the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Portugal and Spain7. Ripe seeds were collected in sandy shores at the border of a salt marsh in Portugal, Algarve region, in the southwestern part of Alvor, in the estuary of the Rio de Alvor to the Atlantic Ocean, at about 10 m above sea level (37° 07′ 48.0′′ N, 8° 37′ 12.0′′ W). The Algarve coast is more sheltered with average high temperatures in summer around 25–28 °C and in winter minimal 11.5 °C. The average annual rainfall is about 500 mm. The area is an euhaline coastal lagoon with a salinity range from 30 to 35% and sandy-silty zones, periodically flooded and consists of coastal salt marshes79. A halophytic plant community is dominating including the C. phelypaea host species Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (Amaranthaceae), Sarcocornia fruticose (Amaranthaceae), Suaeda vera (Amaranthaceae), and Limoniastrum monopetalum (Plumbaginaceae)6 (Fig. 4). The Iberian Peninsula is typified as a hotspot area of biodiversity with a high level of endemism80. The Ria de Alvor is actually a priority conservation area, is part of the European Ecological Network, Natura 2000 and is a RAMSAR wetland of international importance since 199664.

Figure 4.

General habit of the studied species and its habitats: (a,b) Cistanche phelypaea in the coastal salt marshes in Portugal. Photos by R. Piwowarczyk.

Mature and dry seeds of C. phelypaea were collected from ripe fruits from at least 10 individual plants of the total population from the mentioned location in April 2012. Species were collected and identified by Renata Piwowarczyk. The herbarium materials were deposited in the Herbarium of the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (KTC), Poland. Vaucher specimens in the Herbarium KTC are not numbered yet. The herbarium materials are stored in a stable temperature of about 20 °C and a relative humidity of 30%. Field studies, the collection of plant and seeds material was complied with relevant local, institutional, national, and international guidelines, permissions, or legislation, and necessary permissions were obtained.

Seed surface sterilization and homogenization

The aim of seed surface sterilization is to obtain only endophytic bacterial communities (culturable and unculturable). The surfaces of Cistanche seeds possess an alveolate ornamentation sculpture with polygonal and isodiametric cells with different sizes81. An efficient sterilization protocol is crucial. For this purpose, the seeds surface sterilization techniques described by Petrosyan et al.32 were used. The efficiency of the sterilization procedure was verified by plating 100 µl of the last rinsing water on 869 rich medium82. Subsequently, the surface sterilized seeds were mechanically homogenized in 0.5 ml 10 mM MgSO4 solution using a sterile pellet pestle (Kimble®). The homogenization process was accomplished using 5–6 metal stainless steel bead balls (2.8 mm) and a two-bladed mixer mill (Retsch MM400, Germany) for 15 min at 25 Hz. Part of the homogenous suspension was stored at − 80 °C for DNA extraction, another part was used for isolation of culturable bacteria (see below).

Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene fragment and preparation of the next-generation sequencing library

For isolation and identification of the total (cultivable and uncultivable) bacterial community, the homogenized suspension of the surface sterilized seeds was used. The DNA isolation was performed in 4 replicates using the Mobio PowerPlant protocol based on the PowerPlant® Pro DNA Isolation Kit and patented solution (Inhibitor Removal Technology® IRT) for removal of PCR inhibitors from plant extracts during the isolation process.

All isolated DNA samples were subjected to bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicon PCR. In the first round of 16S rRNA gene PCR, an amplicon of 291 bp was generated, using primers 515F-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA and 806R- GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT83, with an Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequence, resulting in the following sequences, 515F-adaptor: 5′-TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG-3′ and 806R-adaptor: 5′-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA G-3′. For the first round of polymerase chain reactions (PCR) the Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase system (M0491, NEB) was used. 16S rRNA gene PCR were performed in 25 μl volumes containing 1 μl of extracted DNA, 1 × Q5 Reaction Buffer with 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP mix, 1 × Q5 High GC Enhancer, 0.25 μM forward or reverse primer, 0.02 U µl−1 Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, 0.5 μl mitoPNA blocker (2 μM final concentration added from a 50 μM stock) and 0.5 μl plastidPNA blocker per sample84. Thermocycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 3 min, denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, all three steps were repeated for a total of 35 cycles and finally 7 min extension at 72 °C. The reaction was ended by cooling at 4 °C. The amplified DNA was purified using the AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and the MagMax magnetic particle processor (ThermoFisher, Leuven, Belgium). 5 μl of the cleaned PCR product was used for the second PCR attaching the Nextera indices. Indexing was performed using the Nextera XT™ library preparation kit ((Nextera XT Index Kit v2 Set A (FC-131-2001) and D (FC-131-2004), Illumina, Belgium). For these PCR reactions, 5 μl of the purified PCR product was used in a 25 μl reaction volume and prepared following the 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Guide. PCR conditions were the same as described above, but the number of cycles reduced to 20, and 55 °C as annealing temperature. PCR products were cleaned with the Agencourt AMPure XP kit, and then quantified in the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen). The libraries were pooled in equimolar concentrations to 4 nM using 10 mM Tris pH 8.5 prior to sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq. Samples were sequenced using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycle) (MS-102-3003) and 15% PhiX Control v3 (FC-110-3001). For quality control, a DNA-extraction blank, PCR blank and ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Mock Community Standard (D6300) to test efficiency of DNA extraction (Zymo Research) were included throughout the process.

Bioinformatic processing of reads

Sequences were demultiplexed using the Illumina Miseq software, and subsequently quality trimmed and primers removed using DADA2 1.10.185 in R version 3.5.1. Parameters for length trimming were set to keep the first 290 bases of the forward read and 200 bases of the reverse read, maxN = 0, MaxEE = (2,5) and PhiX removal. Error rates were inferred, and the filtered reads were dereplicated and denoised using the DADA2 default parameters. After merging paired reads and removal of chimeras via the RemoveBimeraDenovo function, an amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table was built and taxonomy assigned using the SILVA v138 training set86,87. The resulting ASVs and taxonomy tables were combined with the metadata file into a phyloseq object (Phyloseq, version 1.26.1)88. Contaminants were removed from the dataset using the package Decontam (version 1.2.1) applying the prevalence method with a 0.5 threshold value89. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a DECIPHER/Phangorn pipeline as described before90.

Data visualization and statistical analyses

The ASV table was further processed removing organelles (chloroplast, mitochondria), and prevalence filtered using a 2% inclusion threshold (unsupervised filtering) as described by Callahan85. Alpha-diversity metrics such as Chao1, Simpson’s and Shannon’s diversity indexes were calculated on unfiltered data using scripts from the MicrobiomeSeq package. Hypothesis testing was done using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey Honest Significant Differences method (Tukey HSD). When assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were not met, a Kruskal–Wallis Rank Sum test and a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was performed. The results were summarized in boxplots and relative abundances were calculated and visualized in bar charts using Phyloseq. All performed statistical tests were corrected for multiple testing and alpha < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All graphs and figures were generated in R version 4.0.4, Microsoft Office Excel 2010 software.

Isolation and cultivation conditions of culturable endophytes

The first part of the obtained suspension (see above) was used for DNA extraction, the second part was for isolation of culturable bacteria. In order to cultivate as many as possible of the seed endophytes, 100 µL of the seed suspension was plated onto 1/869 rich82, Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) (Sigma-Aldrich), R2A (Sigma-Aldrich), 28491, Flour-yeast extract-sucrose-casein hydrolysate agar (Flour1) and extract-casein hydrolysate agar (YECD)92. Besides the undiluted macerate, serial dilutions were prepared from 10–1 to 10–3 cfu ml1.

After inoculation, the Petri dishes with the different media were incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. The bacterial growth and diversity of colonies were evaluated for both undiluted and diluted seed suspensions. For further experiments, single, morphological distinct colonies were picked and purified. Subsequently, they were grown (in triplicate) in 96-well master blocks at 30 °C for 7 days shaken at 150 rpm. One block was used for DNA-extraction, the second one for PGP assays and the third was stored at − 45 °C in 15% glycerol (75 g glycerol, 4.25 g NaCl, 425 ml dH2O) solution.

Genomic DNA extraction and taxonomic identification of the culturable endophytic bacterial strains

The DNA isolation was performed using standard procedure for DNA isolation from bacterial pellets with MagMAX Express 96 (APPLIED BIOSYSTEMS, Finland). DNA was quantified in a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, US) and a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, US) with an A260/A280 ratio of 1.7–2.0 was used for checking the purity. The near full-length sequences of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using 27f (5-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3) and 1492r (5-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3) primers. A reaction volume of 25 μl per sample was containing 1 μl of DNA, 1 × Q5 Reaction Buffer (2 mM MgCl2), 0.25 μM 27f and 1492r primers, 200 μM dNTP mix and 0.02 U µl−1 Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase and 1 × 5 × Q5 High GC Enhancer84. The 1/10 and 1/20 dilution for some DNA samples were done. PCR conditions were the same as described above, but the number of cycles reduced to 30, and 55 °C annealing temperature. The samples for 16S rRNA Sanger sequencing were shipped to Macrogen (https://www.macrogen-europe.com/). Sequences were quality filtered using Geneious v4.8 and were analyzed using the ribosomal database SILVA (https://www.arb-silva.de/aligner/). Bacteria were identified based on the PCR amplification of partial 16S rDNA gene sequences and annotated using the NCBI GenBank databases by the program Standard Nucleotide BLAST and RDP database (https://rdp.cme.msu.edu/seqmatch/seqmatch_intro.jsp).

Plant growth promoting (PGP) traits

Considering the growth conditions of C. phelypaea the endophytic bacterial isolates were tested for their in vitro plant growth promoting traits and salt tolerance in high salt concentration (6.5%). All tests were performed at least two times.

The tryptophanase activity and Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production ability was tested using the Salkowski reagent32. The organic acid production was determined using the method of Cunningham and Kuiack93. ACC-deaminase activity was tested in SMN medium with 5 mM ACC94. Production of siderophores was assessed by using the 284 medium with 0.25 μl optimal iron concentration with CAS solution95. The detailed descriptions of methods were presented previously32.

Salt tolerance

Salt tolerance ability of isolated bacteria was tested using the modified Brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth63 with composition: Peptic digest of animal tissue 10 g; Heart infusion 10 g; Glucose 1 g; Sodium chloride 65 g; Bromocresol purple 0,016 g per liter with pH 7.2. Bacteria were incubated for 5–7 days at 30 °C at 150 rpm agitation. After 7 days reaction time, the samples were observed for visible growth (turbidity) or color change. The bacterial growth (increase in turbidity) and/or change in the color of broth from purple to yellow was considered as positive. BHI without bacteria was chosen as negative control.

Taxonomic classification of isolates and delineation of molecular OTUs

Ribosomal RNA gene sequences from bacterial isolates were compared with reference sequences from the GenBank databases, using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) software (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) website (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/), and isolates were assigned to species or the highest taxonomic rank possible.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The paper was prepared under “Partnership agreement governing the joint supervision and awarding of a doctorate diploma between Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (Poland) and Hasselt University (Belgium)” (K.P.).

Author contributions

K.P. wrote the main manuscript text, R.P. conducted the field research and undertook the formal identification of the plant material, J.V. and S.T. provided the methodology and laboratory resources; K.P. research, S.T. NGS data curation and bioinformatics; R.P., W.K. and J.V. writing review and editing, K.R. technical check, R.P., J.V., W.K. and K.P. resources; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author acknowledges financial support through the project “Development Accelerator of the Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce”, co-financed by the European Union under the European Social Fund, with No. POWR.03.05.00-00-Z212/18 (K.P.). This study was supported by grants from the Jan Kochanowski University (W.K.; K.P., SUPB.RN.23.236, 2023–2024). This study was also supported by a BOF BILA grant from Hasselt University Belgium BOF21BL12 (2021–2022) (K.P./J.V.) and the Hasselt University Methusalem project (J.V., 08M03VGRJ).

Data availability

The sequence data available in the NCBI Genbank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) Sequence Read Archive with BioSample accession number SAMN26931786. The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences received from of all studied strains were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-38899-9.

References

- 1.Bodelier PLE, Dedysh SN. Microbiology of wetlands. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:79. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tebbe DA, et al. Seasonal and zonal succession of bacterial communities in North Sea salt marsh sediments. Microorganisms. 2022;10(5):859. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10050859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gayathri S, Saravanan D, Radhakrishnan M, Balagurunathan R, Kathiresan K. Bioprospecting potential of fast-growing endophytic bacteria from leaves of mangrove and salt-marsh plant species. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:397–402. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piwowarczyk R, et al. Holoparasitic Orobanchaceae (Cistanche, Diphelypaea, Orobanche, Phelipanche) in Armenia: Distribution, habitats, host range and taxonomic problems. Phytotaxa. 2019;386(1):1–106. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.386.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiao XY, Wang HL, Guo YH. Study on conditions of seed germination of Cistanche. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2007;32(18):1848–1850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piwowarczyk R, Carlón L, Kasińska J, Tofil S, Furmańczyk P. Micromorphological intraspecific differentiation of nectar guides and landing platform for pollinators in the Iberian parasitic plant Cistanche phelypaea (Orobanchaceae) Bot. Lett. 2016;163(1):47–55. doi: 10.1080/12538078.2015.1124287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez-Pedraja Ó, et al. Index of Orobanchaceae. Grupo botánico cantábrico (GBC); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno Moral G, Sánchez Pedraja Ó, Piwowarczyk R. Contributions to the knowledge of Cistanche (Orobanchaceae) in the Western Palearctic. Phyton. 2018;57(1–2):19–36. doi: 10.12905/0380.phyton57-2018-0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe KH, Morden CW, Palmer JD. Function and evolution of a minimal plastid genome from a nonphotosynthetic parasitic plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89(22):10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wicke S, Naumann J. Chapter eleven—Molecular evolution of plastid genomes in parasitic flowering plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 2018;85:315–347. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2017.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joel DM, et al. Biology and management of weedy root parasites. Hort. Rev. 2007;33:267–349. doi: 10.1002/9780470168011.ch4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson O, Kainulainen K. The evolutionary ecology of dust seeds. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011;13(2):73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2011.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruraż K, Piwowarczyk R, Gajdoš P, Krasylenko Y, Čertík M. Fatty acid composition in seeds of holoparasitic Orobanchaceae from the Caucasus region: Relation to species, climatic conditions and nutritional value. Phytochemistry. 2020;179:112510. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaux PM, et al. Origin of strigolactones in the green lineage. New Phytol. 2012;195(4):857–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoneyama K, et al. Strigolactones, host recognition signals for root parasitic plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, from Fabaceae plants. New Phytol. 2008;179(2):484–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, Yoneyama K, Yoneyama K. The strigolactone story. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010;48:93–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahmy GM. Ecophysiology of the holoparasitic angiosperm Cistanche phelypaea (Orobancaceae) in a coastal salt marsh. Turk. J. Bot. 2013;37(5):908–919. doi: 10.3906/bot-1210-48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost A, López-Gutiérrez JC, Purrington CB. Fitness of Cuscuta salina (Convolvulaceae) parasitizing Beta vulgaris (Chenopodiaceae) grown under different salinity regimes. Am. J. Bot. 2003;90(7):1032–1037. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.7.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zagorchev L, Stöggl W, Teofanova D, Li J, Kranner I. Plant parasites under pressure: Effects of abiotic stress on the interactions between parasitic plants and their hosts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(14):7418. doi: 10.3390/ijms22147418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delavault P, et al. Isolation of mannose 6-phosphate reductase cDNA, changes in enzyme activity and mannitol content in broomrape (Orobanche ramosa) parasitic on tomato roots. Physiol. Plant. 2002;115(1):48–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noiraud N, Maurousset L, Lemoine R. Transport of polyols in higher plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2001;39(9):717–728. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(01)01292-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zagorchev L, Albanova I, Tosheva A, Li J, Teofanova D. Salinity effect on Cuscuta campestris Yunck. parasitism on Arabidopsis thaliana L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;132:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soldan R, et al. Bacterial endophytes of mangrove propagules elicit early establishment of the natural host and promote growth of cereal crops under salt stress. Microbiol. Res. 2019;223–225:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crump BC, Hopkinson CS, Sogin ML, Hobbie JE. Microbial biogeography along an estuarine salinity gradient: Combined influences of bacterial growth and residence time. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70(3):1494–1505. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1494-1505.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hua MDS, et al. Metabolomic compounds identified in Piriformospora indica-colonized Chinese cabbage roots delineate symbiotic functions of the interaction. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):9291. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08715-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walitang DI, et al. The influence of host genotype and salt stress on the seed endophytic community of salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant rice cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:51. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardoim PR, et al. The hidden world within plants: Ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of microbial endophytes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015;79(3):293–320. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00050-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103(3):626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg G, Smalla K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;68(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Truyens S, Weyens N, Cuypers A, Vangronsveld J. Bacterial seed endophytes: Genera, vertical transmission and interaction with plants. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2015;7(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston-Monje D, Gutiérrez JP, Lopez-Lavalle LAB. Seed-transmitted bacteria and fungi dominate juvenile plant microbiomes. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:737616. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.737616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrosyan K, et al. Characterization and diversity of seed endophytic bacteria of the endemic holoparasitic plant Cistanche armena (Orobanchaceae) from a semi-desert area in Armenia. Seed Sci. Res. 2022;32(4):264–273. doi: 10.1017/S0960258522000204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston-Monje D, Raizada MN. Conservation and diversity of seed associated endophytes in Zea across boundaries of evolution, ethnography and ecology. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez-López AS, et al. Community structure and diversity of endophytic bacteria in seeds of three consecutive generations of Crotalaria pumila growing on metal mine residues. Plant Soil. 2018;422:51–66. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3176-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engel AS, et al. Salt marsh bacterial communities before and after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83(20):e00784–e817. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00784-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao Z, et al. Bacterial community assembly in a typical estuarine marsh with multiple environmental gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;85(6):e02602–e02618. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02602-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westwood JH. The physiology of the established parasite–host association. In: Joel DM, Gressel J, Musselman LJ, editors. Parasitic Orobanchaceae: Parasitic Mechanisms and Control Strategies. Springer; 2013. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, et al. Insights into the endophytic bacterial community comparison and their potential role in the dimorphic seeds of halophyte Suaeda glauca. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauvêtre A, Schröder P. Uptake of carbamazepine by rhizomes and endophytic bacteria of Phragmites australis. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:83. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shehzadi M, et al. Ecology of bacterial endophytes associated with wetland plants growing in textile effluent for pollutant-degradation and plant growth-promotion potentials. Plant Biosyst. 2016;150(6):1261–1270. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2015.1022238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, et al. A review on microorganisms in constructed wetlands for typical pollutant removal: Species, function, and diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:845725. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.845725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truyens S, et al. The effect of long-term Cd and Ni exposure on seed endophytes of Agrostis capillaris and their potential application in phytoremediation of metal-contaminated soils. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2014;16(7–8):643–659. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2013.837027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Truyens S, et al. The effects of the growth substrate on cultivable and total endophytic assemblages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Soil. 2016;405(1/2):325–336. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2761-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson EB. The seed microbiome: Origins, interactions, and impacts. Plant Soil. 2018;422:7–34. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3289-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Azman AS, Othman I, Velu SS, Chan KG, Lee LH. Mangrove rare actinobacteria: Taxonomy, natural compound, and discovery of bioactivity. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:856. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiwari K, Gupta RK. Rare actinomycetes: A potential storehouse for novel antibiotics. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012;32(2):108–132. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2011.562482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zamora-Quintero AY, Torres-Beltrán M, Guillén Matus DG, Oroz-Parra I, Millán-Aguiñaga N. Rare actinobacteria isolated from the hypersaline Ojo de Liebre Lagoon as a source of novel bioactive compounds with biotechnological potential. Microbiology. 2022;168(2):001144. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barka EA, et al. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015;80(1):1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta N, Mishra S, Basak UC. Diversity of Streptomyces in mangrove ecosystem of Bhitarkanika. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2009;1(3):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang YJ, et al. Saccharopolyspora dendranthemae sp. nov. a halotolerant endophytic actinomycete isolated from a coastal salt marsh plant in Jiangsu, China. Antonie Van Leeuw. 2013;103(6):1369–1376. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9917-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang GL, et al. Isolation, identification and bioactivity of endophytic Actinomycetes from mangrove plants in Beilun River. J. Agric. Biotech. 2015;23(7):894–904. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu SW, et al. Phycicoccus endophyticus sp. nov., an endophytic actinobacterium isolated from Bruguiera gymnorhiza. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66(3):1105–1111. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen P, et al. Community composition and metabolic potential of endophytic actinobacteria from coastal salt marsh plants in Jiangsu, China. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1063. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huet S, et al. Populations of the parasitic plant Phelipanche ramosa influence their seed microbiota. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:1075. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durlik K, Żarnowiec P, Piwowarczyk R, Kaca W. Culturable endophytic bacteria from Phelipanche ramosa (Orobanchaceae) seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 2021;31(1):69–75. doi: 10.1017/S0960258520000343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farah, A. F. Some ecological aspects of Cistanche phelypaea (L.) Cout. (Orobanchaceae) in Al-Hasa Oasis, Saudi Arabia. In Proc. Fourth International Symposium on Parasitic Flowering Plants (eds Weber H. C. & Forstreuter, W.) 187–196 (Philipps University, 1987).

- 57.Fahmy GM, El-Tantawy H, AbdElGhani MM. Distribution, host range, and biomass of two species of Cistanche and Orobanche cernua parasitizing the roots of some Egyptian xerophytes. J. Arid Environ. 1996;34:263–276. doi: 10.1006/jare.1996.0108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hegazy AK, Fahmy GM. Host-parasite allelopathic potential in arid desert plants. In: Macias FA, Galindo JCG, Molinillo JMG, Culter HG, editors. Recent Advances in Allelopathy: A Science for the Future. First World Congress on Allelopathy; 1999. pp. 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian R, et al. Small and mighty: Adaptation of superphylum Patescibacteria to groundwater environment drives their genome simplicity. Microbiome. 2020;8(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00825-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee KCY, Dunfield P, Stott M. The Phylum Armatimonadetes. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, editors. The Prokaryotes: Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and the Archaea. Springer; 2014. pp. 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waite DW, et al. Proposal to reclassify the proteobacterial classes Deltaproteobacteria and Oligoflexia, and the phylum Thermodesulfobacteria into four phyla reflecting major functional capabilities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020;70(11):5972–6016. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jose PA, Jebakumar SR. Non-streptomycete actinomycetes nourish the current microbial antibiotic drug discovery. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:240. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aryal, S. Updated 2023 by Prashant Dahal. Salt Tolerance Test-Principle, Procedure, Results, Uses. https://microbenotes.com/salt-tolerance-test/.

- 64.Mateus M, et al. Conflictive uses of coastal areas: A case study in a southern European coastal lagoon (Ria de Alvor, Portugal) Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016;132:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lackner G, Peters EE, Helfrich EJ, Piel J. Insights into the lifestyle of uncultured bacterial natural product factories associated with marine sponges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114(3):E347–E356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616234114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hannula SE, et al. Persistence of plant-mediated microbial soil legacy effects in soil and inside roots. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):5686. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25971-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lenk S, et al. Novel groups of Gammaproteobacteria catalyse sulfur oxidation and carbon fixation in a coastal, intertidal sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13(3):758–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y, et al. Comparison of the levels of bacterial diversity in freshwater, intertidal wetland, and marine sediments by using millions of illumina tags. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78(23):8264–8271. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01821-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qin S, Li WJ, Klenk HP, Hozzein WN, Ahmed I. Editorial: Actinobacteria in special and extreme habitats: Diversity, function roles and environmental adaptations, second eition. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:944. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang H, Erickson R, Balasubramanian P, Hsieh T, Conner R. Resurgence of bacterial wilt of common bean in North America. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2009;31(3):290–300. doi: 10.1080/07060660909507603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chase AB, Arevalo P, Polz MF, Berlemont R, Martiny JB. Evidence for ecological flexibility in the cosmopolitan genus Curtobacterium. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1874. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayakawa M. Studies on the isolation and distribution of rare Actinomycetes in soil. Actinomycetologica. 2008;22(1):12–19. doi: 10.3209/saj.SAJ220103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta R, Kale P, Rathi M, Jadhav N. Isolation, characterization and identification of endophytic bacteria by 16S rRNA partial sequencing technique from roots and leaves of Prosopis cineraria plant. Asian J. Plant Sci. Res. 2015;5(6):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shrivastava P, Kumar R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015;22(2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh RP, Jha PN. The PGPR Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SBP-9 augments resistance against biotic and abiotic stress in wheat plants. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1945. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li Z, et al. A study of organic acid production in contrasts between two phosphate solubilizing fungi: Penicillium oxalicum and Aspergillus niger. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25313. doi: 10.1038/srep25313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fidalgo C, Henriques I, Rocha J, Tacão M, Alves A. Culturable endophytic bacteria from the salt marsh plant Halimione portulacoides: Phylogenetic diversity, functional characterization, and influence of metal(loid) contamination. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016;23(10):10200–10214. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang M, Li E, Liu C, Jousset A, Salles JF. Functionality of root-associated bacteria along a salt marsh primary succession. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2102. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pérez-Ruzafa A, Marcos C, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Pérez-Marcos M. Coastal lagoons: “Transitional ecosystems” between transitional and coastal waters. J. Coast. Conserv. 2011;15:369–392. doi: 10.1007/s11852-010-0095-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Araújo MB, Thuiller W, Pearson RG. Climate warming and the decline of amphibians and reptiles in Europe. J. Biogeogr. 2006;33(10):1712–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01482.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piwowarczyk R, Ruraż K, Krasylenko Y, Kasińska J, Sánchez-Pedraja Ó. Seed micromorphology of representatives of holoparasitic Orobanchaceae genera from the Caucasus region and its taxonomic significance. Phytotaxa. 2020;432(3):223–251. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.432.3.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eevers N, et al. Optimization of isolation and cultivation of bacterial endophytes through addition of plant extract to nutrient media. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015;8(4):707–715. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walters W, et al. Improved bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V4 and V4–5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys. mSystems. 2015;1(1):e00009. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00009-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kusstatscher P, et al. Microbiome-assisted breeding to understand cultivar-dependent assembly in Cucurbita pepo. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:642027. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.642027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Callahan BJ, et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13(7):581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Quast C, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA and all-species living tree project (LTP) taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D643–D648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davis NM, Proctor DM, Holmes SP, Relman DA, Callahan BJ. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murali A, Bhargava A, Wright ES. IDTAXA: A novel approach for accurate taxonomic classification of microbiome sequences. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0521-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schlegel HG, Kaltwasser H, Gottschalk G. Ein Sumbersverfahren zur Kultur wasserstoffoxidierender Bakterien: Wachstum physiologische Untersuchingen. Archiv. Mikrobiol. 1961;38:209–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00422356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Coombs JT, Franco CM. Isolation and identification of actinobacteria from surface-sterilized wheat roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69(9):5603–5608. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5603-5608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cunningham JE, Kuiack C. Production of citric and oxalic acids and solubilization of calcium phosphate by Penicillium bilaii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58(5):1451–1458. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1451-1458.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Belimov AA, et al. Cadmium-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacteria associated with the roots of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L. Czern.) Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005;37(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987;160(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data available in the NCBI Genbank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) Sequence Read Archive with BioSample accession number SAMN26931786. The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences received from of all studied strains were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers presented in Supplementary Table S1.