Abstract

In plant immunity, the mutually antagonistic hormones salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) are implicated in resistance to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, respectively. Promoters that can respond to both SA and JA signals are urgently needed to engineer plants with enhanced resistance to a broad spectrum of pathogens. However, few natural pathogen-inducible promoters are available for this purpose. To address this problem, we have developed a strategy to synthesize dual SA- and JA-responsive promoters by combining SA- and JA-responsive cis elements based on the interaction between their cognate trans-acting factors. The resulting promoters respond rapidly and strongly to both SA and Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA), as well as different types of phytopathogens. When such a synthetic promoter was used to control expression of an antimicrobial peptide, transgenic plants displayed enhanced resistance to a diverse range of biotrophic, necrotrophic, and hemi-biotrophic pathogens. A dual-inducible promoter responsive to the antagonistic signals auxin and cytokinin was generated in a similar manner, confirming that our strategy can be used for the design of other biotically or abiotically inducible systems.

Key words: salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, dual hormone-responsive promoter, disease resistance, plant engineering, synergistic signal

To enable creation of transgenic plants with broad-spectrum resistance, this study proposes a strategy for the design of dual SA- and JA-responsive promoters by integrating cis elements based on the interaction between their cognate trans-acting factors. Synthetic promoters can rapidly and robustly respond to antagonistic signals and diverse phytopathogens. The strategy is also feasible for other antagonistic signals, such as cytokinin and auxin.

Introduction

Plants encounter attacks by a broad range of microbial pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and oomycetes (Pieterse et al., 2009). Based on their infection and feeding style, plant pathogens are generally classified into two major groups, biotrophs and necrotrophs. Biotrophic pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae and Erysiphe cichoracearum feed on living tissues without killing their hosts, whereas necrotrophic pathogens such as Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria brassicicola kill host cells and feed on the dead tissues (Kemen and Jones, 2012). There are also many hemi-biotrophic pathogens such as Fusarium oxysporum and Verticillium dahliae that have an initial biotrophic phase followed by a necrotrophic phase (Vleeshouwers and Oliver, 2014). Upon pathogen attack, plant synthesizes several key signaling molecules, including salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET), to coordinate the innate immune response (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002). Studies on model plant species such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) and Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) show that SA-mediated defense is typically associated with resistance to biotrophic pathogens, whereas JA and ET are usually implicated in resistance to necrotrophic pathogens. Interactions between SA and JA/ET signaling pathways are mutually antagonistic, suggesting that the plant adopts a binary strategy in which SA and JA/ET have opposing effects to trigger plant defenses in response to different pathogens (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002). Other plant hormones, such as auxins (AUXs), cytokinins (CKs), brassinosteroids (BRs), gibberellins (GAs), strigolactones (SLs), and abscisic acid (ABA), have also been reported to participate in plant innate defense, and they are believed to function by acting on the SA and JA/ET pathways (Shigenaga et al., 2017).

To prevent devastating losses due to plant disease, it is imperative to empower plants with enhanced and durable resistance against a broad range of pathogens. This can be achieved through ectopic expression of the plants’ own defense genes, such as the master immune regulatory gene NPR1 (Xu et al., 2017). A more straightforward approach is to express antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, and proteins involved in the production of antimicrobial metabolites (Wally and Punja, 2010), as well as double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) that interfere with the expression of target genes in the invading pathogens (Hua et al., 2018). An essential aspect of this approach is the choice of promoters. Constitutive promoter-driven expression of these genes can confer enhanced disease resistance on transgenic plants. However, high-level expression of a target gene in transgenic crops may have fitness and/or yield penalties (Chen and Chen, 2002; Fitzgerald et al., 2004). Inducible promoters are thus preferred to ensure precise control of transgene activity, and many native and synthetic inducible systems have been developed for temporal, spatial, and quantitative control of transgene expression (Gurr and Rushton, 2005; Corrado and Karali, 2009; Dey et al., 2015). In particular, a pathogen-inducible promoter can restrict gene expression to the specific time and/or site of infection (Gurr and Rushton, 2005). An ideal pathogen-inducible promoter should perceive a broad range of pathogens and remain inactive unless it is elicited by invading pathogens. Unfortunately, few natural pathogen-inducible promoters can meet these requirements (Hammond-Kosack and Parker, 2003; Gurr and Rushton, 2005). To address this problem, significant efforts have been made to construct synthetic promoters. However, few synthetic pathogen-inducible promoters can respond simultaneously to both SA and JA signals or perceive the presence of pathogens with diverse lifestyles, including biotrophs, necrotrophs, and hemi-biotrophs.

The interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and their target DNA cis-acting elements within promoters determine spatiotemporal transcription patterns. In this study, we present a novel strategy for design and construction of synthetic promoters based on TF interactions. The synthetic promoters can respond to both SA and JA stimuli as well as infection by diverse pathogens. The strategy begins with an evaluation of the interactions between neighboring TFs that bind to candidate cis-regulatory elements in SA- and JA-inducible promoters. Guided by these interactions, cis-regulatory elements are then assembled to construct a set of dual SA- and JA-responsive promoters. To validate the utility of such promoters in plant disease control, we used one of the best promoters to direct the expression of an antimicrobial peptide gene in tomato, tobacco, and cotton. Transgenic plants demonstrated enhanced resistance to powdery mildew in tobacco, early blight in tomato, and Verticillium and Fusarium wilts in cotton, representative diseases caused by biotrophic, necrotrophic, and hemi-biotrophic pathogens, respectively. To further assess this strategy, we also constructed synthetic dual-inducible promoters that were responsive to antagonistic cytokinin and auxin signals by combining the cytokinin-responsive box (2×CKRE) with the auxin-responsive element (AuxRE) on the basis of the interaction between the cytokinin-responsive trans-acting factor Arabidopsis response regulator (ARR) and the auxin-responsive trans-acting factors Auxin response factors (ARFs). The synthesized promoters attenuated the antagonistic effects of cytokinin and auxin and strengthened responses to both signals.

Results

Rational design and construction of dual SA- and JA-responsive promoters

To construct dual hormone-responsive promoters, we initially used a “Lego-blocks” strategy to fuse SA- and JA-responsive cis-regulatory elements with the minimal CaMV 35S promoter. The resulting synthetic promoters could respond to SA and JA stimulation simultaneously. However, they were not applicable in practice because of their high background activity and poor inducibility (Supplemental Figure 1). We therefore decided to use an alternative strategy: insertion of a JA- or SA-responsive box into the backbone of an SA- or JA-inducible promoter. To identify an ideal backbone promoter, we first evaluated six candidates: the JA-responsive promoter PDF1.2 of Arabidopsis (Manners et al., 1998) and five SA-responsive promoters, SWPA4 of sweet potato (Ryu et al., 2009), YPR10 of apple (Pühringer et al., 2000), PR-1a of tobacco (Van de Rhee and Bol, 1993), and LURP1 and PR-1 of Arabidopsis (Lebel et al., 1998; Knoth and Eulgem 2008). The six promoters were used to direct the expression of a reporter gene encoding β-glucuronidase (GUS), and the resulting constructs were transferred into tobacco for activity analysis. Because of its highly inducible activity and low background, the PR-1a promoter was chosen as the backbone for insertion of a JA-responsive cis-regulatory cassette (Supplemental Figure 2; Supplemental Table 1).

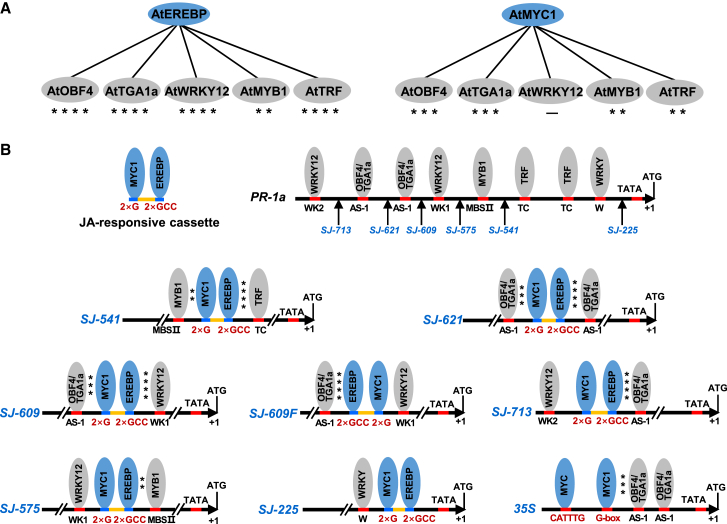

The next question was where to insert the JA box in the PR-1a promoter. To find suitable insertion sites, we needed to know whether trans-acting factors that bind to different JA or SA cis-acting elements can work synergistically to initiate transcription of a target gene. A survey of the PR-1a promoter revealed one W-box, MBSII, WK1, and WK2 and two TC-rich repeat and AS-1 elements (Figure 1B; Supplemental Figure 3A). Their cognate trans-acting factors were WRKY, MYB1, WRKY12, TRF, and OBF4/TGA1a, respectively (Figure 1B). AP2-EREBP and MYC1 have been recognized as trans-acting regulators for the GCC-box and G-box, two key cis-regulatory elements that respond to JA induction (Yang and Klessig, 1996; Strompen et al., 1998; Doerks et al., 2002; Xu and Timko, 2004; Van Verk et al., 2008; Ou et al., 2011). We used bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) (Hu et al., 2002) to evaluate the interactions between these JA- and SA-responsive trans-acting factors. For the JA-responsive trans-acting factor AtEREBP, strong interactions were observed with the SA-responsive trans-acting factors AtOBF4, AtTGA1a, AtWRKY12, and AtTRF, whereas a weak interaction was observed with AtMYB1 (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 4A). For AtMYC1, another key JA-responsive trans-acting factor, strong interactions were observed with AtOBF4 and AtTGA1a, followed by AtMYB1 and AtTRF, but no interaction was observed with AtWRKY12 (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 4B).

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of synthetic promoters that respond to SA and JA signals.

(A) Interactions between SA- and JA-responsive trans-acting factors. Interaction strength was estimated by the intensity of YFP fluorescence (Supplemental Figure 4).

(B) Schematic representations of PR-1a, 35S, and synthetic promoters constructed in this study. The JA-responsive cassette contains two G-box (2×G) and two GCC-box (2×GCC) elements with a 29-bp spacer sequence from the NtPMT promoter. MYC1 and EREBP are JA-responsive trans-acting factors that can bind to G- and GCC-boxes in the promoter sequences, respectively. The sequence of the JA-responsive cassette is shown in Supplemental Figure 3. The insertion site of the JA-responsive cassette in PR-1a is indicated by arrows. Numbers indicate the positions of the insertion sites relative to the start codon (ATG). WRKY12, OBF4/TGA1a, MYB1, and TRF are SA-responsive trans factors that can bind to WK1/WK2, AS-1, MBSII, and TC-rich repeats in the promoter sequences, respectively. TATA is the TATA box. ∗∗∗∗More than 10 fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2, ∗∗∗five to 10 fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2, ∗∗two to five fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2, ∗one fluorescent spot per 0.1 mm2, superscript minus sign (−) indicates no fluorescence signal. 35S is the CaMV 35S promoter.

A JA-responsive cassette (Figure 1B; Supplemental Figure 3B) containing duplicated GCC-boxes and G-boxes was then synthesized and inserted between two cis-regulatory elements within in the PR-1a promoter (Figure 1B; Supplemental Figure 3A; Supplemental Table 2). Six synthetic promoters were constructed and divided into three groups on the basis of interactions between neighboring trans-acting factors. In the first group, the JA cassette was inserted such that strong interactions between neighboring trans-acting factors could occur on both sides of the cassette (i.e., SJ-541, -609, and -621); in the second group, the interaction could occur on only one side of the cassette (i.e., SJ-713 and -575); and in the third, no interaction was observed (SJ-225) (Figure 1B).

Synthesized promoters respond quickly, strongly, and simultaneously to the antagonistic SA and JA signals

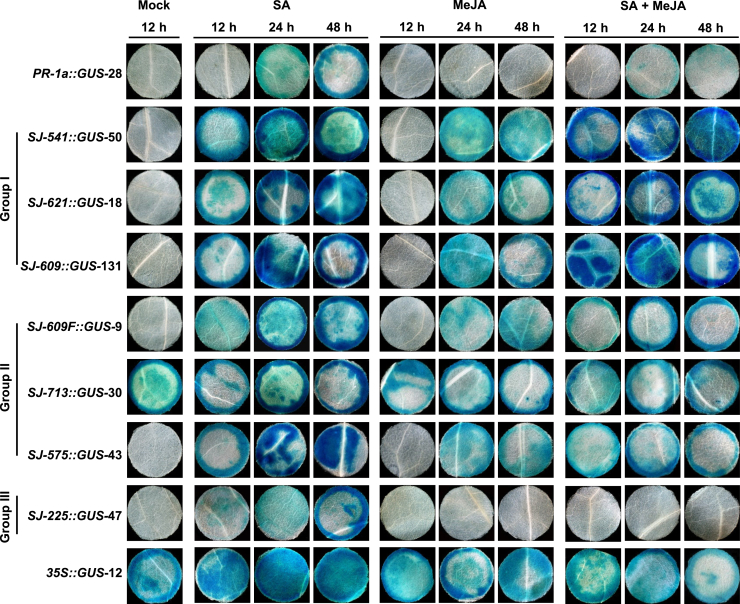

The synthetic promoters were fused with the GUS gene, and the resulting transgenic tobacco plants were treated with SA, Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA), or their combination. GUS analysis showed that the group I promoters (SJ-541, -609, and -621) responded quickly to SA or/and MeJA stimulation and exhibited high levels of inducible GUS activity without detectable background activity (Figure 2; Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Among the group II promoters, SJ-575 also responded to both SA and MeJA, but the GUS activity was clearly lower than that of group I after treatment with SA and MeJA together (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 4). SJ-713 exhibited significant background GUS activity like the 35S promoter (Figure 2). In the last group, the SJ-225 promoter responded only to SA, like the native PR-1a promoter (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 4). To confirm these results, we flipped the JA-responsive cassette at the site of SJ-609 and generated SJ-609F. Unlike SJ-609, in which interactions may occur on both sides (OBF4/TGA1a-MYC1 and EREBP-WRKY12), SJ-609F had interaction on only one side (EREBP-OBF4/TGA1a) (Figure 1B). GUS analysis showed that SJ-609F produced significantly lower GUS activity than SJ-609, particularly following treatment with both SA and MeJA (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 2.

Histochemical GUS staining of different transgenic tobacco lines treated with SA and MeJA alone or in combination.

The GUS gene was driven by the native PR-1a promoter, the 35S promoter, or one of seven synthetic promoters, as indicated. Detached tobacco leaves were treated with SA, MeJA, or both for 6 h. Leaf discs (Φ 6 mm) were then cut out and subjected to 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide (X-gluc) staining at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. Numbers of transgenic tobacco lines are as shown in Supplemental Table 3.

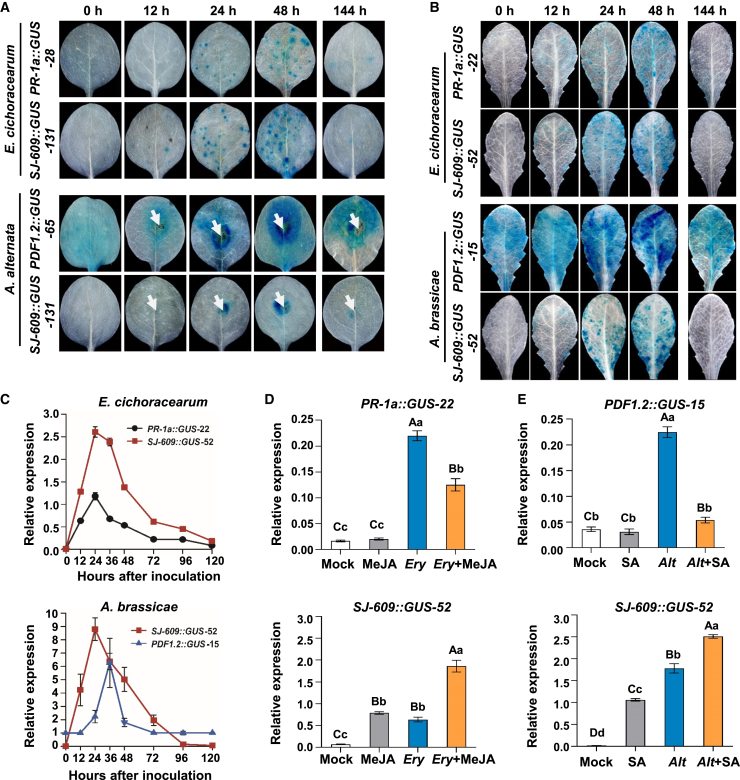

Figure 4.

Induction of GUS activity in transgenic tobacco and Arabidopsis upon infection with biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens.

(A) GUS staining of leaves from representative PR-1a::GUS-28, SJ-609::GUS-131, and PDF1.2::GUS-65 transgenic tobacco lines infected with the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum or the necrotrophic pathogen A. alternata. White arrows indicate the site of A. alternata inoculation. To withdraw the pathogen challenge, fungicide (fenaminosulf) was sprayed onto infected leaves 72 h after inoculation. GUS staining was performed 72 h after withdrawal of the challenge. Ten transgenic tobacco lines per construct were used for analysis of GUS activity.

(B) GUS staining of leaves from representative PR-1a::GUS-22, SJ-609::GUS-52, and PDF1.2::GUS-15 transgenic Arabidopsis lines infected with the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum or the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria brassicae. Five transgenic Arabidopsis lines per construct were used for analysis of GUS activity.

(C)GUS expression patterns of representative PR-1a::GUS-22, PDF1.2::GUS-15, and SJ-609::GUS-52 transgenic Arabidopsis lines induced by E. cichoracearum (above) and A. alternata (below). Values are the means of three technical replicates with SD. Similar results were obtained for three repeated experiments. E. cichoracearum and A. alternata were sprayed as 107 spore/ml spore suspensions.

(D and E)GUS expression in PR-1a::GUS-22, PDF1.2::GUS-15, and SJ-609::GUS-52 transgenic Arabidopsis lines with the indicated treatments. Mock, deionized water as a mock control for SA treatment (E) or 0.1% ethyl alcohol as a mock control for MeJA treatment (D); MeJA, sprayed with 0.5 mM MeJA; Ery, inoculated with E. cichoracearum; Ery + MeJA, inoculated with E. cichoracearum, then sprayed with 0.5 mM MeJA 24 h later; SA, sprayed with 1 mM SA; Alt, inoculated with A. alternata; Alt + SA, inoculated with A. alternata, then sprayed with 1 mM SA 24 h later. Results in (D and E) are averages of three biological replicates with SD. Lowercase and capital letters above bars indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s multiple comparison procedure at the 0.05 (P < 0.05) or 0.01 level (P < 0.01), respectively. GUS expression levels in (C), (D), and (E) were quantified by qRT-PCR of cDNA prepared from RNA extracted from treated or infected leaves. AtACT2 served as the reference gene. GUS and AtACT2 primers for qRT-PCR are shown in Supplemental Table 9.

To further evaluate the activity of the synthetic promoters, we detected the GUS levels in transgenic tobacco by western blotting (WB). Following induction with SA, the GUS level of SJ-609::GUS and SJ-541::GUS tobacco (group I promoter) was similar to that of SJ-575::GUS and SJ-609F::GUS (group II promoter) tobacco. However, it was about 2.5–4.0 times higher than that of SJ-575::GUS and SJ-609F::GUS tobacco when induced with SA plus MeJA (Figure 3A–3D). The average GUS level of two SJ-541::GUS and SJ-609::GUS tobacco lines was about 14.5 and 12.3, 2.7 and 2.8 times higher than that of two PR-1a::GUS tobacco lines induced by SA plus MeJA and SA at 12 h and 48 h after treatment, respectively (Figure 3C and 3D). We also chose SJ-609 as a representative synthetic promoter and tested the GUS transcription level after treatment with SA or/and MeJA. The results confirmed that the SJ-609 promoter worked more sensitively and responded more quickly to SA or/and MeJA than the native promoters PR-1a and PDF1.2 (Supplemental Figure 5). These results suggested that dual hormone-responsive promoters could respond simultaneously to antagonistic SA and JA signals, indicating that trans-acting factors that interact with one another can work together synergistically to initiate transcription of target genes.

Figure 3.

GUS levels in transgenic tobacco induced by SA and MeJA, alone or in combination.

(A and B) WB analysis of GUS induced by SA and MeJA, alone or in combination. Four- to six-leaf tobacco seedlings were sprayed with SA and MeJA alone or in combination. After treatment for (A) 12 and (B) 48 h, leaves were collected for protein extraction. A total of 200 μg of protein was detected with rabbit monoclonal antibody to GUS. In all cases, actin antibodies were used for the loading control. Blots in (A) and (B) are representative of three biological replicates that showed similar results.

(C and D) GUS amount was quantified based on the band intensity, standardized to the actin signals. Results shown in the graphs (C and D) represent three biological replicates. Error bars indicate SD. Statistically significant differences were determined by Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01) compared with SA or MeJA alone. SA, sprayed with 1 mM SA; MeJA, sprayed with 0.5 mM MeJA; SA + MeJA, sprayed with 1 mM SA plus 0.5 mM MeJA; Mock, deionized water as a mock control for SA treatment or 0.1% ethyl alcohol as a mock control for MeJA and SA + MeJA treatment.

To investigate whether the synthetic promoters could sense the presence of invading pathogens, transgenic tobacco and Arabidopsis plants were challenged with biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogens. In tobacco, no GUS activity was observed in SJ-609::GUS-131 and PR-1a::GUS-28 transgenic lines prior to pathogen challenge (Figure 4A). After challenge with E. cichoracearum, a biotrophic pathogen of tobacco, GUS activity was observed in PR-1a::GUS-28 and SJ-609::GUS-131 tobacco. However, the signal appeared 12 h earlier in SJ-609::GUS-131 tobacco than that in PR-1a::GUS-28 tobacco (Figure 4A). Strong GUS activity was observed at 24 h post pathogen challenge in the SJ-609::GUS-131 line and at 48 h in PR-1a::GUS-28 transgenic tobacco. After withdrawal of pathogen challenge, almost no GUS activity was observed in SJ-609::GUS-131 and PR-1a::GUS-28 (Figure 4A). After challenge with the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria alternata, a typical inducible profile of GUS expression was observed in transgenic SJ-609::GUS-131 tobacco. However, apparent GUS activity was observed in PDF1.2::GUS-65 transgenic tobacco prior to pathogen challenge and after withdrawal of the challenge (Figure 4A). A similar profile of GUS expression was observed in transgenic Arabidopsis (Figure 4B and 4C). These observations demonstrate that SJ-609 is a typical pathogen-inducible promoter similar to PR-1a. However, the synthetic promoter works more sensitively and responds more quickly to pathogens than the native promoters. Interestingly, the E. cichoracearum-induced GUS activity of PR-1a::GUS-22 Arabidopsis plants was significantly suppressed when the pathogen challenge was accompanied by MeJA treatment (Figure 4D). A similar suppression phenomenon was observed in PDF1.2::GUS-15 Arabidopsis transgenic plants that were challenged with the necrotrophic pathogen A. alternata and treated with SA (Figure 4E). By contrast, GUS activity remained high or was even higher in SJ-609::GUS-52 Arabidopsis plants when pathogen challenges were accompanied by SA or MeJA treatment (Figure 4D and 4E). These results further confirm that SA and JA signals were synergistic rather than antagonistic when the synthetic promoter SJ-609 was used instead of native promoters.

Synthetic promoters responsive to antagonistic auxin and cytokinin signals

Cytokinin and auxin act antagonistically to control meristem activities (Moubayidin et al., 2009). To further validate our strategy, we constructed a synthetic dual-inducible promoter responsive to both cytokinin and auxin. As before, we first tested the interaction between trans-acting factors responsive to auxin induction and those responsive to cytokinin induction. To this end, coding regions of the auxin-responsive trans-acting factors AtARF1 and AtARF5 and the cytokinin-responsive trans-acting factors AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12 were cloned from Arabidopsis, and interactions between these factors were tested by BiFC assays in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Interactions were observed for AtARF1 and AtARF5 with AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12 (Supplemental Figure 6). We then chose DR5 as the backbone (Chen et al., 2013) for construction of the dual hormone-responsive promoters (Supplemental Figures 7 and 8A). The cytokinin-responsive box (2×CKRE) was inserted into the promoter sequence at different sites where the cytokinin-responsive trans-acting factor ARR could putatively interact with the left and right neighboring auxin-responsive trans-acting ARFs (Supplemental Figures 7 and 8A).

The resulting promoters, RF1, RF2, and RF3, were individually fused with the GUS gene. Transgenic Arabidopsis lines were treated with Indole acetic acid (IAA) and Kinetin (KT) individually or in combination. At 12 h after treatment, GUS protein was detected in RF1::GUS, RF2::GUS, and RF3::GUS transgenic Arabidopsis. However, it was nearly undetectable in transgenic plants in which GUS was under the control of the auxin-inducible promoter (DR5::GUS) or cytokinin-inducible promoter (TCS::GUS), indicating that the synthetic promoters responded more rapidly than the DR5 or TCS promoters to IAA, KT, or their combination (Supplemental Figures 8B and 8D). At 24 h after treatment, GUS levels were increased in RF1::GUS, RF2::GUS, and RF3::GUS Arabidopsis treated with IAA and KT together but reduced in DR5::GUS and TCS::GUS Arabidopsis compared with those treated with IAA or KT alone (Supplemental Figures 8C and 8E). These results indicated that the synthetic promoters could attenuate the antagonistic effects of auxin and cytokinin and strengthen responses to these stimuli.

SJ-609-driven spCEMA expression confers resistance against to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens in tobacco and tomato

To test the effectiveness of our synthetic promoter in genetic engineering for plant disease control, SJ-609 was used to drive expression of the modified cationic antimicrobial peptide spCEMA, a derivative of CEMA that has been identified as a good candidate for plant disease-resistance engineering (Yevtushenko et al., 2005). Transgenic tobacco and tomato harboring SJ-609::spCEMA, PR-1a::spCEMA, and PDF1.2::spCEMA were generated. For each construct, fifteen lines were randomly selected from the transgenic tobacco and tomato and challenged with either a biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogen. For challenge with the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum, the disease resistance of transgenic tobacco was evaluated as the percentage of leaf area covered by the fungus (PACF) in the 15 lines. The average value of PACF in 15 SJ-609::spCEMA lines was 12.2%, compared with 25.8%, 34.8%, and 63.9% in PR-1a::spCEMA, PDF1.2::spCEMA, and the wild-type controls. In 15 transgenic tobacco lines, the number of lines without detectable disease symptoms (PACF = 0) was three, one, and zero in SJ-609::spCEMA, PR-1a::spCEMA, and PDF1.2::spCEMA lines, respectively (Figure 5A and 5B). For challenge with the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria solani, resistance was estimated using the disease index (DI). The average DI value of 15 SJ-609::spCEMA tomato lines was 18.9, compared with 36.5, 31.2, and 86.4 in PR-1a::spCEMA, PDF1.2::spCEMA, and the wild-type controls. In 15 transgenic tomato lines, the number of lines with DIs below 10 were four in SJ-609::spCEMA, one in PDF1.2::spCEMA, and zero in PR-1a::spCEMA (Figure 5C and 5D). Observation of disease symptoms revealed that powdery mildew mycelia on leaves of SJ-609::spCEMA tobacco and leaf spots associated with early blight on SJ-609::spCEMA tomato were significantly less abundant than those on PR-1a::spCEMA tobacco or PDF1.2::spCEMA tomato (Figure 5E and 5F). These results showed that spCEMA driven by SJ-609 exhibited better performance than that driven by native promoters in terms of resistance to a biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogen.

Figure 5.

PR-1a::spCEMA, SJ-609::spCEMA, and PDF1.2::spCEMA transgenic plants to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens.

(A and B) Resistance of transgenic tobacco lines to the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum, the causal agent of tobacco powdery mildew. Resistance was estimated as the average PACF (A) and the number of lines with different PACF (B) of 15 lines at 10 days after inoculation (DAI).

(C and D) Resistance of transgenic tomato lines to the necrotrophic pathogen A. solani, the causal agent of tomato early blight. Resistance was estimated as the average DI (C) and the number of lines with different DI (D) of 15 lines at 7 DAI.

(E) Symptoms of transgenic tobacco inoculated with E. cichoracearum at 10 DAI. PR-1a::spCEMA-13, SJ-609::spCEMA-20, and PDF1.2::spCEMA-7 are representative lines for each construct.

(F) Symptoms of transgenic tomato inoculated with A. solani at 7 DAI. PR-1a::spCEMA-7, SJ-609::spCEMA-26, and PDF1.2::spCEMA-17 are representative lines for each construct. Error bars denoting SDs of the mean are based on three independent experiments. The values of lines in each bar of (A), (B), (C), and (D) are the average PACF (A) or DI (C) of three independent tests, and the numbers of lines with different PACF or DI values are indicated by different colors (B and D). Lowercase and capital letters above bars in (A) and (C) indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s multiple comparison procedure at the 0.05 (P < 0.05) and 0.01 level (P < 0.01), respectively. WT, wild type.

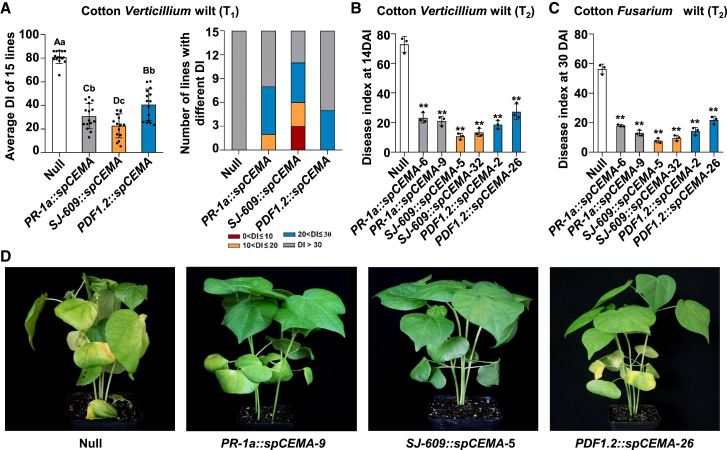

SJ-609-driven spCEMA expression confers resistance to hemi-biotrophic pathogens in cotton

We next asked whether SJ-609::spCEMA could also confer resistance to hemi-biotrophic pathogens. Fifteen (T1) lines of SJ-609::spCEMA, PR-1a::spCEMA, and PDF1.2::spCEMA transgenic cotton were randomly selected and challenged with the hemi-biotrophic pathogen V. dahliae. The average DI of 15 SJ-609::spCEMA lines was 22.6, compared with 30.9, 40.5, and 80.8 in PR-1a::spCEMA, PDF1.2::spCEMA, and non-transgenic plants (segregated from the T0 generation). Three transgenic SJ-609::spCEMA lines had DIs below 10, whereas all PR-1a::spCEMA and PDF1.2::spCEMA lines had DIs above 10 (Figure 6A), indicating that synthetic promoter–driven expression of spCEMA confers greater disease resistance than that driven by native promoters.

Figure 6.

Resistance of PR-1a::spCEMA, SJ-609::spCEMA, and PDF1.2::spCEMA transgenic cotton to the hemi-biotrophic pathogens V. dahliae and F. oxysporum.

(A) Resistance of T1 transgenic cotton to V. dahliae, the causal agent of cotton Verticillium wilt. Resistance was estimated as the average DI of 15 lines at 14 DAI. Error bars denoting SDs of the mean are based on three independent experiments. The values of lines in each bar are the average DIs of three independent tests (left), and the numbers of lines with different DIs are indicated by different colors (right). Lowercase and capital letters above the bars indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s multiple comparison procedure at the 0.05 (P < 0.05) and 0.01 level (P < 0.01), respectively.

(B and C) Resistance of T2 transgenic cotton to V. dahliae(B) and F. oxysporum(C), the causal agent of cotton Fusarium wilt. Resistance was estimated as the average DI. Error bars denote SDs of the mean (n = 3). The value of each bar is the average of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗P < 0.01) compared with the null control.

(D) Symptoms of T2 transgenic cotton inoculated with the V991 strain of V. dahliae at 14 DAI. Null, non-transgenic plants derived from transformants of cotton (T0).

To confirm the resistance phenotype exhibited in the T1 generation, two lines of each construct that showed the best resistance to Verticillium wilt were selected for further investigation. In the T2 generation, the SJ-609::spCEMA lines still showed better V. dahliae resistance than the others (Figure 6B and 6D). Challenged with F. oxysporum, another hemi-biotrophic pathogen of cotton, SJ-609::spCEMA transgenic lines again showed higher resistance than the other transgenic lines (Figure 6C). Although CaMV 35S promoter–driven expression of spCEMA did increase the resistance of cotton to V. dahliae, some 35S::spCEMA transgenic cotton plants were infertile owing to malformations in anther and pollen grains (Supplemental Figure 9). However, no obvious adverse effects on cotton development were observed in transgenic SJ-609::spCEMA cotton (Supplemental Figure 9). The transgenic cotton exhibited yield components and fiber quality comparable to those of the wild-type control (Supplemental Table 5). These results demonstrated that spCEMA driven by the SJ-609 promoter increased cotton resistance to multiple pathogens without sacrificing productivity.

Discussion

In most cases, the interaction between the SA- and JA/ET signaling pathways is mutually antagonistic in dicot plant species (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002). Exogenous application of SA can suppress JA-mediated resistance to necrotrophic pathogens, whereas JA and its analog can suppress SA-dependent defenses against biotrophic pathogens (Brooks et al., 2005; Spoel et al., 2007). During infection by biotrophic pathogens, pathogen-induced SA-mediated defenses can suppress JA signaling, thus making plants more susceptible to necrotrophic pathogens, and vice versa (Spoel et al., 2007). When using a transgenic approach to enhance resistance to a broad spectrum of diseases, we need a versatile promoter to direct the expression of target genes. This is particularly important for hemi-biotrophic diseases such as Verticillium wilt and Fusarium wilt of cotton and scab of wheat, both of which exhibit biotrophic and necrotrophic phases. Unfortunately, no such promoter capable of responding quickly and accurately to the two antagonistic hormones has been available. SA- and JA-responsive cis elements are usually located separately. In this study, guided by interaction assays of cognate trans-acting factors, we rationally assembled a JA-responsive cis-element box into the typical SA-responsive promoter PR-1a to construct synthetic promoters. These synthetic promoters are highly activated in the presence of SA, JA, or both hormones and show no detectable background activity. When the synthetic promoter was used to control expression of the antimicrobial peptide spCEMA, transgenic tobacco, tomato, and cotton displayed better resistance to different pathogens, including biotrophs, necrotrophs, and hemibiotrophs, than that obtained using natural pathogen-inducible promoters (i.e., PR-1a and PDF1.2). This SA and JA dual-responsive promoter can be used to engineer plants with resistance to multiple diseases. Although the efficacy of these synthetic promoters has been assessed only in Arabidopsis, tobacco, tomato, and cotton, this approach could be adapted for other dicot plants, and even monocot crops with modification of the regulators. Dual promoters responsive to both auxin and cytokinin were also generated in a similar manner, indicating the feasibility of this strategy for different antagonistic signals. Thus, the strategy is also useful for studying cross-talk between antagonistic signaling pathways, such as SA–JA and auxin–cytokinin.

Typically, a synthetic promoter is designed with variable cis-acting elements fused to a core promoter. While the core promoter directs basal transcription initiation, cis-regulatory elements determine the strength and temporal and spatial expression patterns of target genes (Liu and Stewart, 2016). Several strategies have been devised to generate synthetic promoters for plant biotechnology applications, including cis-motif engineering, TF engineering, and their combination (Liu and Stewart, 2016). The cis-motif engineering approach uses a Lego-blocks strategy to combine different cis-regulatory elements with a core promoter, such as the minimal CaMV 35S promoter (Ulmasov et al., 1997; Gurr and Rushton, 2005). However, there have been no synthetic promoters that can simultaneously respond to both SA and JA signals or perceive the presence of pathogens with diverse lifestyles. Here, we used cis-regulatory elements of the JA-responsive cassette (2×GCC-box and 2×G-box) as a building block and inserted it into the typical SA-responsive promoter PR-1a. The key to this strategy is selecting an appropriate location for the inserted element(s). Using yeast-two-hybrid and BiFC assays, Zhu and colleagues (Zhu et al., 2019) confirmed the existence of a protein–protein interaction between the transcription factors DkERF24 and DkWRKY1. They showed that the combination of DkERF24 and DkWRKY1 could significantly activate the DkPDC2 promoter, producing 13-fold higher activation than DkERF24 or DkWRKY1 individually. BiFC is an in vivo tool for imaging the interaction between proteins. In this study, we used BiFC to detect potential interactions between SA- and JA-responsive TFs (such as the combinations AtEREBP–AtOBF4/AtTGA1a/AtWRKY12/AtTRF and AtMYC1–AtOBF4/AtTGA1a). Based on the BiFC results, we arranged a JA-responsive cis element between two SA-responsive cis elements to simultaneously recruit their cognate trans-acting factors. After exposure to SA and SA + MeJA, the synthetic SJ-609 promoter exhibited 2.8- and 12.3-fold higher activity than the native promoter PR-1a. Likewise, based on the interaction between ARR and ARF determined by BiFC in plant cells, dual promoters that could respond to the antagonistic hormones auxin and cytokinin were successfully constructed, confirming the feasibility of this strategy. The synthetic dual SA- and JA-responsive promoters are capable of perceiving a broad range of phytopathogens with different lifestyles. This strategy depends on a basic understanding of native promoters, including identification of their cis-regulatory elements and cognate trans-acting factors. To this end, high-throughput screening methods are required.

Recent studies have revealed that the antagonism between SA and JA is controlled by the transcription cofactor NPR1 (Spoel et al., 2003). SA can stimulate transcription of NPR1, which interacts with the TGACG-binding factor (TGA) and activates the expression of SA-responsive genes, including PR1, WRKY38, and WRKY70. The SA-induced NPR1 can also work as a suppressor of JA-induced immunity by binding to MYC2, a key trans-acting regulator that responds to JA induction (Nomoto et al., 2021). We speculate that in artificial promoters such as SJ-609, in which the JA-responsive 2×G sequence is located proximately to the AS1 sequence, the former can recruit MYC and the latter can recruit TGA for binding. The interaction between MYC and TGA may interfere with the interaction between MYC and NPR1 but not interrupt the interaction of TGA with NPR1, thus breaking down the antagonism between SA and JA. Nonetheless, evaluation of this hypothesis will require additional data. Investigating the interaction between regulatory factors of the two signaling pathways will provide more insight into the mechanism that underlies SA–JA antagonism.

In plant genetic engineering, the CaMV 35S (35S) promoter is widely used to create transgenic plants. This promoter is constitutively active in most tissues throughout the life of the plant. However, it has been documented that global overexpression of target genes may produce undesirable phenotypes (Chen and Chen, 2002; Fitzgerald et al., 2004). Taking 35S-driven expression of antimicrobial proteins (AMPs) as an example, AMPs from throughout the animal and plant kingdoms have been widely used to control a variety of plant pathogens (Zasloff, 2002). Because natural AMPs have undesirable properties that limit their use in crop protection, synthetic AMPs have been rationally designed and generated for use in agriculture (Marcos et al., 2008). A well-documented instance is CEMA, a cecropin A-melittin chimeric peptide with strong antimicrobial activity. However, studies suggest that CEMA and its N-terminally modified derivative MsrA1 are toxic to plant cells (Osusky et al., 2000; Yevtushenko et al., 2005). In the present study, 35S was used to drive expression of the modified CEMA gene spCEMA in cotton. Some 35S::spCEMA transgenic cotton plants were infertile (Supplemental Figure 9). Unlike the 35S promoter, the SJ-609 promoter remains silent prior to a challenge but is rapidly and strongly activated in response to the stress (Figure 4). Importantly, SJ-609::spCEMA plants (including tomato, tobacco, and cotton) showed normal growth and development and significantly enhanced resistance to infection by pathogens with diverse lifestyles, demonstrating the feasibility of this strategy for control of different plant diseases.

Our study introduces a novel strategy to design dual hormone-responsive promoters for perception of a broad range of pathogens. We believe that this strategy will be widely applicable for the rational design of other inducible promoters that can respond to different biotic and/or abiotic stress signals, greatly expanding the promoter toolbox for plant synthetic biology.

Methods

Materials and growth conditions

Plant materials

Plant materials used in this study include A. thaliana (Columbia ecotype), N. tabacum Samson (tobacco) and Nicotiana benthamiana, Lycopersicon esculentum Micro-Tom (tomato), and Gossypium hirsutum cv. Jimian 14 (cotton).

Plant growth conditions

A. thaliana plants were grown on a turfy soil mixture with perlite and vermiculite (3:1:1) in a growth chamber under neutral daylength conditions (12-h:12-h, light:dark cycle) with a day:night temperature of 22°C:20°C and 70% relative humidity. Tobacco and tomato seedlings were grown on the same soil mixture in a growth chamber under a 16-h:8-h light:dark cycle with a day:night temperature of 26°C:22°C and 60% relative humidity. Cotton plants were cultivated in a growth chamber or in experimental plots at Southwest University, China.

Fungal culture

Fungal isolates were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 26°C for 7 days. For spore production, V. dahliae and F. oxysporum cultures were grown in potato dextrose broth (PDB) at 26°C with shaking at 120 rotations per minute (rpm) for 7 days. The cultures were harvested by filtering through Miracloth, and spore suspension was collected by centrifugation. Spores were washed with sterile distilled water and then re-suspended at a concentration of about 106 (F. oxysporum) and 107 (V. dahliae) spores/ml. For A. brassicicola, A. alternata, and A. solani, conidial suspensions were prepared by adding 15 ml of sterile distilled water to each plate and gently scraping the surface with a sterile spatula. The spore suspensions were filtered through a fluted filter, washed twice with sterile water by centrifugation (4000 g for 10 min), and re-suspended with 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80 solution. The conidial suspension was adjusted to 1–3 × 107 conidia/ml with 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80. For the biotrophic E. cichoracearum, the pathogen was propagated on living tobacco plants in a growth chamber. Spores collected from the infected plants were suspended with 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80 at a concentration of about 107 or 1010 spore/ml.

Construction of recombinant plasmids

Construction of plasmids for BiFC assay

Sequences of genes encoding the trans-acting factors AtEREBP, AtMYC1, AtOBF4, AtTGA1a, AtMYB1, AtWRKY12, AtTRF, AtARF1, AtARF5, AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12, which bind to the cis-acting elements GCC-box, G-box, AS-1, MBSII, W-box (WK1 and WK2), TC-rich repeat, AuxRE, and CKRE ((G/A)GAT(T/C)), respectively, were retrieved from the NCBI database. Coding regions without the stop codon were cloned by PCR using cDNA from V. dahliae-infected Arabidopsis as the template. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 6. PCR amplicons were inserted into the pDONR221 donor vector to create entry clones using Gateway BP Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The authenticity of PCR amplicons was verified by sequencing. To create the final Gateway expression constructs (see Supplemental Table 10 for details), all entry clones were cloned into the Gateway destination vectors pEG201 and pRG202 with Gateway LR Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). The resulting expression constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 via electroporation for BiFC analysis.

Construction of plasmids for promoter analysis

The native promoters YPR10 of apple (Pühringer et al., 2000), SWPA4 of sweet potato (Ryu et al., 2009), LURP1, PR-1, and PDF1.2 of Arabidopsis (Lebel et al., 1998; Manners et al., 1998; Knoth and Eulgem 2008), and PR-1a of tobacco (Van de Rhee and Bol, 1993) were cloned by PCR amplification using genomic DNA of apple, sweet potato, Arabidopsis, and tobacco as templates. All primers used to clone native promoters are listed in Supplemental Table 7. The synthetic promoters SJ-541, SJ-609, SJ-621, SJ-609F, SJ-575, SJ-713, and SJ-225 were obtained using gene splicing by overlap extension (SOE) as described previously (Horton et al., 1993). All primers used for synthetic promoter cloning are listed in Supplemental Table 8. The RF1, RF2, and RF3 promoters were synthesized by Wuhan Tianyu-Huayu Gene Sci-Tech. Recognition sequences of HindIII and BamHI were incorporated into appropriate primers to facilitate the subsequent cloning procedure. The amplified or synthesized fragments were digested with HindIII and BamHI and ligated into the corresponding sites of the pBI121 binary vector to drive expression of the GUS gene by replacing the CaMV 35S promoter.

Construction of vectors expressing an antimicrobial peptide gene

To construct a plant expression vector containing CaMV 35S promoter–driven spCEMA, the antimicrobial peptide sequence was inserted into the pBI121-GN plant expression vector (Luo et al., 2007) between the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites, resulting in formation of the recombinant plasmid pBI121-GN-spCEMA. To construct expression vectors in which the antimicrobial peptide was under the control of pathogen-inducible promoters, the 35S promoter sequence in pBI121-GN-spCEMA was replaced by PR-1a, SJ-609, or PDF1.2. The final plasmids were designated pBI121-GN-PR-1a::spCEMA, pBI121-GN-SJ-609::spCEMA, and pBI121-GN-PDF1.2::spCEMA.

Plant transformation

Plasmids and vectors constructed for promoter analysis and expression of the antimicrobial peptide were delivered into A. tumefaciens LBA4404 and GV3101 and then transferred into tobacco, Arabidopsis, tomato, or cotton. The floral dip method described by Clough and Bent (1998) was used for transformation of Arabidopsis (Col.), and the selection of transformants was performed as described by Harrison et al. (2006). The leaf disc method was used for tobacco (Samson) transformation as described by Zheng et al. (2007). Tomato transformation was performed as described by Zhang and Blumwald (2001). Cotton (cv. Jimian 14) transformation was performed according to the method reported by Luo et al. (2007).

BiFC analysis

For BiFC analysis of SA- and JA-responsive TFs, 4-week-old tobacco plants were infiltrated with different combinations of pEG201 and pRG202 recombinant plasmids as described by Hu et al. (2002). Combinations of trans-acting factors and their corresponding plasmid combinations are shown in Supplemental Table 11. According to the design of interactions between trans-acting factors (Supplemental Table 11), their corresponding plasmid combinations were delivered into N. benthamiana plants by agroinfiltration. YFP fluorescence signals were observed 36–48 h after injection using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000, Olympus) with excitation/emission wavelengths of 515/527 nm. Protein interactions were classified into four levels: ∗∗∗∗, more than 10 fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2; ∗∗∗, five to ten fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2; ∗∗, two to five fluorescent spots per 0.1 mm2; ∗, one fluorescent spot per 0.1 mm2. BiFC analysis of auxin- and cytokinin-responsive TFs was performed in Arabidopsis protoplasts using the preparation and infection procedures described by Yoo et al. (2007).

Promoter induction assay

Hormone treatment

SA was dissolved in deionized water. IAA, KT, and MeJA were dissolved in ethyl alcohol and diluted with deionized water. The deionized water was used as a mock control for SA treatment, and 0.1% ethyl alcohol was used as a mock control for MeJA, IAA, and KT treatment. The detached tobacco leaves were treated with 1 mM SA (Sigma) or 0.5 mM MeJA (Sigma), alone or in combination. Tobacco leaves were dipped into hormone solution for 6 h. The treated leaves were then incubated at 25°C with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod in a growth chamber. Samples were harvested at different time points after SA and MeJA treatment for GUS assay. Six- to eight-leaf Arabidopsis plants were sprayed with 25 μM IAA or 25 μM KT, alone or in combination. Samples were harvested at 12 and 24 h after IAA and KT treatment for GUS assay.

Pathogen challenge

Five microliters of A. alternata spore suspension (107 spore/ml) were dropped onto the main vein of sterile leaves of four-leaf tobacco plants. A spore suspension (107 spore/ml) of E. cichoracearum was sprayed onto sterile leaves of tobacco. Spore suspensions of A. brassicicola (107 spore/ml) and E. cichoracearum (107 spore/ml) were sprayed onto sterile leaves of eight-leaf Arabidopsis plants. All inoculated plants were incubated at 25°C with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod and 70% relative humidity. To withdraw the pathogen challenge, fungicide (fenaminosulf) was sprayed onto the infected leaves 72 h after inoculation.

Pathogen challenge accompanied by hormone treatment

Arabidopsis plants were smeared with a spore suspension (107 spore/ml) of the necrotrophic pathogen A. brassicicola. Half of the pathogen-challenged plants were treated with 1 mM SA after 24 h of infection. Arabidopsis plants were smeared with a conidial suspension (107 spore/ml) of the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum, and half of the plants were treated with 0.5 mM MeJA after 24 h of infection. Infected plants were incubated at 25°C with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod and 70% relative humidity. Leaves were harvested for GUS expression analysis 24 h after SA or MeJA treatment. The mock control plants were smeared with 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80 for pathogen challenge, 0.1% (v/v) ethyl alcohol for MeJA treatment, and deionized water for SA treatment.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Plant samples harvested after inoculation or treatment were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted following the instructions supplied by the manufacturer (Promega), and synthesis of first-strand cDNA was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TaKaRa). A 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μl of cDNA and SYBR Green Super-mix (Bio-Rad) was used for qRT-PCR following the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad), and data were analyzed using the supplier’s software (Bio-Rad). The thermal cycling consisted of a pre-treatment (94°C, 3 min) followed by 40 amplification cycles (94°C, 30 s; 57°C, 30 s; 72°C, 30 s). Tobacco 18S and Arabidopsis ACT2 genes served as the reference genes. qRT-PCR primers were designed using Primer 5.0 and are shown in Supplemental Table 9.

GUS assays

Leaves of Arabidopsis and tobacco were used for SA and MeJA treatment or pathogen inoculation. Leaves or leaf discs were immersed in staining solution (100 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0], 0.5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100, 1 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-glucuronic acid substrate in DMSO [diluted from a 25 mM stock solution]) as described by Jefferson (1987). After staining at 37°C for 12 h in the dark, samples were rinsed and fixed in 75% ethanol. Images were taken on an SZX-ILLB2-200 stereomicroscope imaging system (Olympus).

For protein analysis, plant leaves harvested after treatment were homogenized in liquid nitrogen using a grinding mill. Protein was extracted in the equivalent of 1 ml of protein extraction buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.4 mM NaCl, pH 7.3) per 250 mg of tissue. The homogenate was gently mixed at 4°C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min. Total protein was quantified and standardized for each gel using a BCA assay. About 200 μg of total protein was loaded onto a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel and run using the Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN Tetra vertical electrophoresis system. After electroblotting, the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was blocked for 2 h at room temperature with a 5% milk/TBS solution (25 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl). Plant actin monoclonal antibody generated in mouse was used as a loading control at a 1:5000 dilution (Abbkine ABM40122). GUS monoclonal antibody was generated against rabbit by Abcam and used at a 1:5000 dilution (ab166904). IPKine horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-mouse or mouse anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody according to the manufacturer’s instructions at a 1:2000 dilution (Abbkine A25012 and A25022). Membranes were scanned using ChemiCapture, and images were captured at 1 min (for actin) and 10 min (for GUS) after treatment with ECL. Adobe Photoshop was used to quantify band intensity.

Disease-resistance assays

The fourth leaves from the tip were sprayed with a spore suspension of E. cichoracearum (1010 spores/ml), and the tobacco plants were transferred to a growth chamber at 26°C with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod and 70% relative humidity. PACF was assessed after 10 days of inoculation, and the mean PACF of three independent experiments was used to evaluate plant disease resistance (Letessier et al., 2001).

For challenge with the necrotrophic pathogen A. solani, healthy mature trifoliate leaflets of tomato were sprayed with a conidial suspension of A. solani (1–3 × 107 conidia/ml). Infected leaflets were kept in a growth chamber at 26°C with a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod and 100% relative humidity. Disease-resistance level was estimated after 7 days and scored as follows: 0, no visible lesions on leaves; 1, 1–25% of leaf area affected; 2, 26%–50% of leaf area affected; 3, 51%–75% of leaf area affected; 4, 76%–100% of leaf area affected (Chaerani et al., 2007).

For challenge with V. dahliae or F. oxysporum, 14-day-old cotton seedlings were inoculated with V. dahliae V991 strain (107 spores/ml) by uprooting and root-dip inoculation as described by Fradin et al. (2009). The infected plants were returned to the pots under a 16-h light:8-h night photoperiod at 26°C with 70% relative humidity. The DI was assessed at 14 days after inoculation. Foliar damage was evaluated by rating symptoms on the cotyledons and leaves of inoculated plants according to the descriptions in Zhang et al. (2012). Evaluation standards for disease grades were as follows: 0, no symptoms (healthy); 1, <25% chlorotic/necrotic leaves; 2, 25%–50% chlorotic/necrotic leaves; 3, 50%–75% chlorotic/necrotic leaves; 4, >75% chlorotic/necrotic leaves, complete defoliation, or plant death. At least 30 individual plants per line were used for resistance analysis in each experiment. A similar inoculation method was used to measure F. oxysporum resistance. The DI was measured after 30 days in a growth chamber. After inoculation with F. oxysporum, foliar damage was evaluated by rating the leaf symptoms of inoculated plants according to the evaluation standards used for Verticillium wilt. For cotton and tomato, resistance was assessed as the average DI of three experiments.

For disease-resistance assays, 15 lines per construct were randomly selected and used for resistance analysis in each experiment. The experiment was repeated three to five times. The copy numbers of all transgenic line inserts were determined from the segregation ratio of the GUS gene in the T1 generation. Transgenic lines that exhibited a 3:1 segregation ratio of GUS-positive/-negative were classified as single-copy lines. Disease resistance of transgenic plants was assessed using single-copy lines.

The DI was calculated according to the formula

DI = (sum [disease grade × number of infected plants]/[total number of checked plants × 4]) × 100 (Zhang et al., 2012).

Statistical analysis

All numerical values are presented as average ± SD. Statistical differences between the null control and T2 transgenic lines were evaluated using two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences among PR-1a::spCEMA, SJ-609::spCEMA, PDF1.2::spCEMA, and the wild type or null were tested using Duncan’s multiple comparisons. The numbers of replicates are shown in the figure legends.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071463), the Chongqing Foundation for leaders of disciplines in science (cstc2014kjcxljrc005), and the Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology (cstc2017jcyjB0316).

Author contributions

Y.P. designed the experiments. X.L., G.N., Y.F., W.L., Q.W., C.Y., J.W., Y.X., L.H., D.J., S.C., R.H., and Y.Y. performed the experiments. Y.P., X.L., and G.N. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Guiliang Jian (Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing) for the gift of V. dahliae strain V991 and Prof. Xiangqun Zhang (Industrial Crop Research Institute, Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for the gift of F. oxysporum isolate. No conflict of interest is declared.

Published: March 30, 2023

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Accession numbers

Sequence data used in this study are from the NCBI database. The accession numbers are as follows: AtEREBP (AT2G44840), AtMYC1 (AT4G00480), AtOBF4 (AT5G10030), AtTGA1a (AT1G22070), AtMYB1 (AT3G09230), AtWRKY12 (AT2G44745), AtTRF (AT1G06910), AtARF1 (AT1G59750.1), AtARF5 (AT1G19850.1), AtARR1 (AT3G16857.2), AtARR10 (AT4G31920.1), AtARR12 (AT2G25180.1), AtACT2 (AT3G18780), and Nt18S (HQ384692.1).

Supplemental information

References

- Brooks D.M., Bender C.L., Kunkel B.N. The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005;6:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaerani R., Groenwold R., Stam P., Voorrips R.E. Assessment of early blight (Alternaria solani ) resistance in tomato using a droplet inoculation method. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2007;73:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen Z. Potentiation of developmentally regulated plant defense response by AtWRKY18, a pathogen-induced Arabidopsis transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:706–716. doi: 10.1104/pp.001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Yordanov Y.S., Ma C., Strauss S., Busov V.B. DR5 as a reporter system to study auxin response in Populus. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1378-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado G., Karali M. Inducible gene expression systems and plant biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009;27:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey N., Sarkar S., Acharya S., Maiti I.B. Synthetic promoters in planta. Planta. 2015;242:1077–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerks T., Copley R.R., Schultz J., Ponting C.P., Bork P. Systematic identification of novel protein domain families associated with nuclear functions. Genome Res. 2002;12:47–56. doi: 10.1101/gr.203201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald H.A., Chern M.S., Navarre R., Ronald P.C. Overexpression of (At)NPR1 in rice leads to a BTH- and environment-induced lesion-mimic/cell death phenotype. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:140–151. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradin E.F., Zhang Z., Juarez Ayala J.C., Castroverde C.D.M., Nazar R.N., Robb J., Liu C.M., Thomma B.P.H.J. Genetic dissection of Verticillium wilt resistance mediated by tomato Ve1. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:320–332. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurr S.J., Rushton P.J. Engineering plants with increased disease resistance: how are we going to express it? Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack K.E., Parker J.E. Deciphering plant-pathogen communication: fresh perspectives for molecular resistance breeding. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003;14:177–193. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S.J., Mott E.K., Parsley K., Aspinall S., Gray J.C., Cottage A. A rapid and robust method of identifying transformed Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings following floral dip transformation. Plant Methods. 2006;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton R.M., Ho S.N., Pullen J.K., Hunt H.D., Cai Z., Pease L.R. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 1993;217:270–279. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua C., Zhao J.H., Guo H.S. Trans-kingdom RNA silencing in plant-fungal pathogen interactions. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.D., Chinenov Y., Kerppola T.K. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R.A. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1987;5:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Kemen E., Jones J.D.G. Obligate biotroph parasitism: can we link genomes to lifestyles? Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoth C., Eulgem T. The oomycete response gene LURP1 is required for defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008;55:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel B.N., Brooks D.M. Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:325–331. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel E., Heifetz P., Thorne L., Uknes S., Ryals J., Ward E. Functional analysis of regulatory sequences controlling PR-1 gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1998;16:223–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letessier M.P., Svoboda K.P., Walters D.R. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) J. Phytopathol. 2001;149:673–678. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Stewart C.N., Jr. Plant synthetic promoters and transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;37:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Xiao Y., Li X., Lu X., Deng W., Li D., Hou L., Hu M., Li Y., Pei Y. GhDET2, a steroid 5a-reductase, plays an important role in cotton fiber cell initiation and elongation. Plant J. 2007;51:419–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manners J.M., Penninckx I.A., Vermaere K., Kazan K., Brown R.L., Morgan A., Maclean D.J., Curtis M.D., Cammue B.P., Broekaert W.F. The promoter of the plant defensin gene PDF1.2 from Arabidopsis is systemically activated by fungal pathogens and responds to methyl jasmonate but not to salicylic acid. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;38:1071–1080. doi: 10.1023/a:1006070413843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos J.F., Muñoz A., Pérez-Payá E., Misra S., López-García B. Identification and rational design of novel antimicrobial peptides for plant protection. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2008;46:273–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.121307.094843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moubayidin L., Di Mambro R., Sabatini S. Cytokinin-auxin crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto M., Skelly M.J., Itaya T., Mori T., Suzuki T., Matsushita T., Tokizawa M., Kuwata K., Mori H., Yamamoto Y.Y., et al. Suppression of MYC transcription activators by the immune cofactor NPR1 fine-tunes plant immune responses. Cell Rep. 2021;37:110125. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osusky M., Zhou G., Osuska L., Hancock R.E., Kay W.W., Misra S. Transgenic plants expressing cationic peptide chimeras exhibit broad-spectrum resistance to phytopathogens. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/81145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou B., Yin K.Q., Liu S.N., Yang Y., Gu T., Wing Hui J.M., Zhang L., Miao J., Kondou Y., Matsui M., et al. A high-throughput screening system for Arabidopsis transcription factors and its application to Med25-dependent transcriptional regulation. Mol. Plant. 2011;4:546–555. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C.M.J., Leon-Reyes A., Van der Ent S., Van Wees S.C.M. Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:308–316. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pühringer H., Moll D., Hoffmann-Sommergruber K., Watillon B., Katinger H., da Câmara Machado M.L. The promoter of an apple Ypr10 gene, encoding the major allergen Mal d 1, is stress- and pathogen-inducible. Plant Sci. 2000;152:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S.H., Kim Y.H., Kim C.Y., Park S.Y., Kwon S.Y., Lee H.S., Kwak S.S. Molecular characterization of the sweet potato peroxidase SWPA4 promoter which responds to abiotic stresses and pathogen infection. Physiol. Plantarum. 2009;135:390–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigenaga A.M., Berens M.L., Tsuda K., Argueso C.T. Towards engineering of hormonal crosstalk in plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017;38:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel S.H., Johnson J.S., Dong X. Regulation of tradeoffs between plant defenses against pathogens with different lifestyles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18842–18847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel S.H., Koornneef A., Claessens S.M.C., Korzelius J.P., Van Pelt J.A., Mueller M.J., Buchala A.J., Métraux J.P., Brown R., Kazan K., et al. NPR1 modulates cross-talk between salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent defense pathways through a novel function in the cytosol. Plant Cell. 2003;15:760–770. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strompen G., Grüner R., Pfitzner U.M. An as-1-like motif controls the level of expression of the gene for the pathogenesis-related protein 1a from tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;37:871–883. doi: 10.1023/a:1006003916284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T., Murfett J., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T.J. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1963–1971. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Rhee M.D., Bol J.F. Induction of the tobacco PR-1a gene by virus infection and salicylate treatment involves an interaction between multiple regulatory elements. Plant J. 1993;3:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Van Verk M.C., Pappaioannou D., Neeleman L., Bol J.F., Linthorst H.J.M. A Novel WRKY transcription factor is required for induction of PR-1a gene expression by salicylic acid and bacterial elicitors. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1983–1995. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers V.G., Oliver R.P. Effectors as tools in disease resistance breeding against biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic plant pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014;27:196–206. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0313-IA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wally O., Punja Z.K. Genetic engineering for increasing fungal and bacterial disease resistance in crop plants. GM Crops. 2010;1:199–206. doi: 10.4161/gmcr.1.4.13225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Timko M. Methyl jasmonate induced expression of the tobacco putrescine N -methyltransferase genes requires both G-box and GCC-motif elements. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004;55:743–761. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-1962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Yuan M., Ai C., Liu L., Zhuang E., Karapetyan S., Wang S., Dong X. uORF-mediated translation allows engineered plant disease resistance without fitness costs. Nature. 2017;545:491–494. doi: 10.1038/nature22372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Klessig D.F. Isolation and characterization of a tobacco mosaic virus-inducible myb oncogene homolog from tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:14972–14977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevtushenko D.P., Romero R., Forward B.S., Hancock R.E., Kay W.W., Misra S. Pathogen-induced expression of a cecropin A-melittin antimicrobial peptide gene confers antifungal resistance in transgenic tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:1685–1695. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S.D., Cho Y.H., Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Yang Y., Chen T., Yu W., Liu T., Li H., Fan X., Ren Y., Shen D., Liu L., et al. Island cotton Gbve1 gene encoding A receptor-like protein confers resistance to both defoliating and NonDefoliating isolates of Verticillium dahliae. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.X., Blumwald E. Transgenic salt-tolerant tomato plants accumulate salt in foliage but not in fruit. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:765–768. doi: 10.1038/90824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Deng W., Luo K., Duan H., Chen Y., McAvoy R., Song S., Pei Y., Li Y. The cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter sequence alters the level and patterns of activity of adjacent tissue- and organ-specific gene promoters. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:1195–1203. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.G., Gong Z.Y., Huang J., Grierson D., Chen K.S., Yin X.R. High-CO2/Hypoxia-Responsive transcription factors DkERF24 and DkWRKY1 interact and activate DkPDC2 promoter. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:621–633. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.