Abstract

Streptomyces coelicolor produces four genetically and structurally distinct antibiotics in a growth-phase-dependent manner. S. coelicolor mutants globally deficient in antibiotic production (Abs− phenotype) have previously been isolated, and some of these were found to define the absB locus. In this study, we isolated absB-complementing DNA and show that it encodes the S. coelicolor homolog of RNase III (rnc). Several lines of evidence indicate that the absB mutant global defect in antibiotic synthesis is due to a deficiency in RNase III. In marker exchange experiments, the S. coelicolor rnc gene rescued absB mutants, restoring antibiotic production. Sequencing the DNA of absB mutants confirmed that the absB mutations lay in the rnc open reading frame. Constructed disruptions of rnc in both S. coelicolor 1501 and Streptomyces lividans 1326 caused an Abs− phenotype. An absB mutation caused accumulation of 30S rRNA precursors, as had previously been reported for E. coli rnc mutants. The absB gene is widely conserved in streptomycetes. We speculate on why an RNase III deficiency could globally affect the synthesis of antibiotics.

The streptomycetes are morphologically complex gram-positive soil bacteria. They are widely important in biotechnology because of the many bioactive secondary metabolites they produce; these include compounds used as antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor, antiparasitic, and immunosuppressive drugs. Production of these secondary metabolites is temporally and spatially regulated during the complex streptomycete life cycle, occurring in conjunction with the growth of a sporulating aerial mycelium.

Streptomyces coelicolor, the genetically best-characterized species, is a model streptomycete for study of antibiotic regulation (reviewed in references 8 and 15). It is known to produce four antibiotics: actinorhodin (Act), undecylprodigiosin (Red), methylenomycin (Mmy), and calcium-dependent antibiotic (CDA).

Growth-phase regulation of streptomycete secondary metabolites (or, generically, antibiotics) is subject to both global and antibiotic-specific regulation. Transcriptional regulation of each antibiotic’s biosynthetic gene cluster depends on a cluster-linked, antibiotic-specific, transcriptional regulator (reviewed in reference 8). The antibiotic-specific regulators, most of which are activators, are themselves subject to growth-phase regulation, being expressed after a period of vegetative growth has elapsed. For S. coelicolor, the characterized antibiotic-specific regulators are actII-ORF4 for Act and redD for Red.

Growth-phase-regulated expression, in both liquid and plate-grown cultures, is apparent for both actII-ORF4 and redD (reviewed in reference 7). Both undergo substantial increases in mRNA abundance after several days of incubation of plate cultures (1) or a period of quasi-exponential growth in defined medium-grown liquid cultures (25, 51). Accumulation of ppGpp is one factor known to be involved in regulating these genes’ expression (8, 38), especially in nitrogen-limited media (12). Other regulatory mechanisms that may participate in actII-ORF4 and redD regulation are poorly understood at present.

One approach to characterizing the genetic elements involved in antibiotic regulation has been to isolate mutants that fail to produce any of S. coelicolor’s known antibiotics but that do progress normally through the morphogenesis cycle. Screens for this phenotype, named Abs− (for antibiotic synthesis negative), yielded mutants of the absA (4) and absB (3) loci.

Examination of actII-ORF4 and redD transcription in absA and absB Abs− strains has shown that these mutants are substantially defective in the expression of the antibiotic regulators (1). The actII-ORF4 and redD expression defect likely accounts for the mutants’ Act− and Red− phenotypes. Expression of cda and mmy genes has not yet been assessed.

The Abs− phenotype of absA and absB mutants has suggested that these loci encode components of a regulatory pathway or network that functions, at least in some conditions, to coordinately, or globally, regulate S. coelicolor’s antibiotics. The predicted absA gene products, which comprise a two-component-type signal transduction system (10), would be candidates for global regulatory elements. Among other candidates for global regulatory elements are relA, which encodes ppGpp synthetase (12, 38), the two-component systems afsQ1/Q2 (28) and cutR/S (16), the afsRKS locus (23, 39, 40, 54), which encodes a serine threonine protein phosphotransfer system, and the mia (14), abaA (22), and abaB (50) loci, which encode products of unknown function. An additional set of genes, named bld, regulates morphogenesis (reviewed in references 15 and 17), as well as antibiotic synthesis. The functional relationships of these genes are not yet characterized.

We report here a characterization of the absB locus and identify the absB gene as the S. coelicolor homolog of RNase III-encoding genes (rnc). RNase III is an endonuclease that processes certain double-stranded RNA substrates and so regulates expression of a set of cellular and bacteriophage genes and also participates in rRNA processing (19). Sequence analysis of several mutant absB alleles revealed mutations that would likely functionally debilitate an RNase III-like protein. Constructed disruption mutations in absB, both in S. coelicolor and in its close relative Streptomyces lividans, caused the Abs− phenotypes. As in Escherichia coli RNase III mutants (rnc), an S. coelicolor absB mutant accumulated 30S rRNA precursors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Streptomyces cultures were propagated on R5 agar or in YEME broth (27) unless otherwise indicated. SMMS medium was as described previously (25, 51). Thiostrepton (10 μg/ml, final concentration) or hygromycin (100 μg/ml, final concentration) was added as needed. Conditions for growth of cultures and preparation of spore stocks were as described earlier (27). Escherichia coli cultures were grown on Luria-Bertani medium (48) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml, final concentration) as required to maintain plasmids.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | ||

| J1501 | hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 27 |

| M124 | cysD18 proA1 argA1 SCP1− SCP2− | 27 |

| M145 | Prototroph, SCP1− SCP2− | 27 |

| C120 | absB120 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 3 |

| C170 | absB170 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 3 |

| C175 | absB175 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 3 |

| C252 | absB252 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 3 |

| C23 | absB::pBK314 (Hygr) hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | This study |

| C120-310 | absB120::pBK310 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | This study |

| C542 | absA542 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 4 |

| C301 | bldA301 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 13 |

| C112 | bldB112 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 13 |

| C109 | bldH109 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 13 |

| C103 | bldG103 hisA1 uraA1 strA1 SCP1− SCP2− Pgl− | 13 |

| S. lividans | ||

| 1326 | Prototroph | 27 |

| C24 | absB::pBK314 (Hygr) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Gibco BRL | |

| ET12567 | dam dcm mutant | 37 |

| DM-1 | dam dcm mutant | Gibco BRL |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Construction and/or distinguishing characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces replicons | ||

| pTA108 | pIJ922 + 11-kb Sau3A fragment | 2 |

| pTA128 | pIJ922 + 7-kb Sau3A fragment | 2 |

| pIJ922 | Low-copy-number SCP2* derivative | 27 |

| pBK600 | 1.4-kb BglII fragment from pBK412 in pIJ922 | This study |

| pBK601 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK651 in pIJ922/BamHI | This study |

| pBK602 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK652 in pIJ922/BamHI | This study |

| pBK603 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK653 in pIJ922/BamHI | This study |

| pIJ702 | High-copy-number pIJ101 derivative, Thior | 27 |

| pBK650 | 1.4-kb BglII fragment from pBK412 in pIJ702 | This study |

| pBK651 | 1.0-kb PCR-generated BglII fragment (primers A and D) from J1501 in pIJ702/BglII | This study |

| pBK652 | 1.0-kb PCR-generated BglII fragment (primers A and D) from C120 in pIJ702/BglII | This study |

| pBK653 | 1.0-kb PCR-generated BglII fragment (primers A and D) from C175 in pIJ702/BglII | This study |

| E. coli replicons | ||

| pBluescript KS(+) | Ampr, lacZ insertional inactivation KpnI-SacI MCS | Stratagene |

| pBluescript SK(+) | (pKS+) or SacI-KpnI MCS (pSK+) | |

| pKJ100 | 8.3-kb BglII fragment from pTA108 in pKS+ | This study |

| pBK200 | 3.3-kb PstI fragment from pTA108 in pKS+ | This study |

| pBK210 | 2.6-kb PstI fragment from pTA108 in pKS+ | This study |

| pBK212 | 1.4-kb PstI-ApaI fragment from pBK210 in pKS+ | This study |

| pBK213 | 1.2-kb ApaI-PstI fragment from pBK210 in pKS+ | This study |

| pBK802 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK651 in pSK+ | This study |

| pBK803 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK652 (absB120) in pSK+ | This study |

| pBK804 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment from pBK653 (absB175) in pSK+ | This study |

| pRK805 | 1.0-kb BglII fragment amplified from C252 pIJ2925 derivative with Hygr | This study |

| pIJ963 | ||

| pBK300 | 3.3-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment from pBK200 in pIJ963 | This study |

| pBK310 | 2.6-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment from pBK210 in pIJ963 | This study |

| pBK312 | 1.4-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment from pBK212 in pIJ963 | This study |

| pBK313 | 1.2-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment from pBK213 in pIJ963 | This study |

| pBK314 | 460-bp PCR-generated BglII fragment (primers B and IF) from J1501 in pIJ963 | This study |

| pIJ2925 | pUC19 derivative with modified multiple cloning site | 29 |

| pBK412 | 1.4-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment from pBK212 in pIJ2925 | This study |

Genetic techniques and DNA manipulations.

Streptomyces protoplasts were generated and transformed as described previously (27). Transformants were regenerated on R5, and the selective antibiotic was applied at 18 to 20 h. High-copy-number Streptomyces plasmid DNA was isolated either manually (27) or by using QIAgen Midi Plasmid Columns (Qiagen, Inc.). Low-copy-number plasmid (pIJ922) derivatives were isolated by using the procedure for SCP2* derivatives (27). Chromosomal DNA used for PCR and Southern hybridizations was isolated as described earlier (27). E. coli cultures were transformed as described previously (48). E. coli plasmid DNA was isolated by the alkaline lysis procedure (48) or by QIAprep spin columns (Qiagen, Inc.) when used in automated sequencing. All E. coli plasmids were passed through dam dcm mutant E. coli ET12567 (37) or DM-1 to generate unmethylated DNA suitable for introduction into Streptomyces.

For PCR amplification, Deep Vent polymerase was used (New England Biolabs), and reactions were carried out essentially as recommended by the manufacturer, with the addition of glycerol to a 10% final concentration per reaction. Cycling conditions were as follows: hold at 95°C for 5 min, denature at 96°C for 45 s, anneal at 70°C for 45 s, and extend at 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles.

Cloning the absB locus.

The isolation of the absB-encoding DNA was carried out by using a low-copy-number pIJ922 plasmid library (2). The library contained 10- to 30-kb fragments of Sau3A partially digested J1501 chromosomal DNA (10). The cloning scheme took advantage of the self-transmissible nature of pIJ922. M124 protoplasts were transformed with the pIJ922 plasmid library. Thior resistant transformants were replicated onto the lawns of the absB mutant C120 on R5 medium. After sporulation, the mating plates were replicated onto medium selective for C120 recipients and nonpermissive for the M124 host strain (i.e., glucose minimal medium containing uracil, histidine, thiostrepton, and streptomycin). The transconjugants were visually screened for the Act+ Red+ phenotype and subsequently tested for the CDA+ and Mmy+ phenotypes (in SCP1+ derivatives constructed as described in reference 4). Assays for Act, Red, Mmy, and CDA have been described previously (4).

Physical mapping of the absB locus.

The absB locus was localized on the S. coelicolor physical map (32, 46) as follows. AseI-digested J1501 chromosomal DNA was separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (32). The 3.3-kb PstI fragment from absB complementing clone pTA108 was random primed labeled (Boehringer Mannheim) with [α-32P]dCTP for hybridization to the membrane. High-stringency conditions were used (65°C; 2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] and 0.5× SSC washes), and the annealed probe was detected by film exposure for 24 h at −70°C.

Functional analysis of the absB locus through recombinational marker rescue and complementation.

Subfragments of the 11.0-kb insert of pTA108 were cloned into the E. coli vector pBluescript KS(+) (Stratagene). In recombinational rescue experiments, fragments were then ligated into the E. coli vector pIJ963 (33), which carries a Hygr gene suitable for selection in Streptomyces. Unmethylated pIJ963 derivatives were used to transform absB mutant strains. Hygr recombinants were isolated (indicating the occurrence of a single crossover event via homologous recombination within the insert) and scored for an Abs+ phenotype 3 to 4 days after transformation. In initial complementation studies, pTA108 fragments were cloned into pIJ2925, which has BglII sites flanking the multiple cloning site (29). After passage through ET12567, clones were digested with BglII to yield unmethylated fragments which were ligated into both the high-copy-number pIJ702 and the low-copy-number pIJ922. In subsequent experiments, the PCR-generated absB gene was amplified by using primers with heterologous BglII sites designed at the ends for cloning directly into pIJ702. In either case, ligation mixtures were used to transform absB mutant C120, and Thior transformants were scored for the Abs+ phenotype. Complementing clones from Abs+ transformants were isolated, and the constructs were confirmed by restriction mapping and Southern hybridization. Complementing clones (e.g., pBK802) were then used to retransform C120 and to transform other absB mutant strains, as well as wild-type J1501. PCR-generated absB mutant alleles were similarly cloned (e.g., pBK803 and pBK804) and introduced back into their respective absB mutant backgrounds as a negative control for complementation.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Automated sequencing of the absB locus from wild-type and absB mutant strains was performed at the Iowa State University and the Michigan State University sequencing facilities. Nested deletion clones from pBK210 and PCR-generated fragments were used as sequencing templates. PCR primers A and D (see Fig. 2) were used to generate templates of the absB gene from wild-type and mutant strains; these were functionally characterized by complementation (see above) and were also cloned into pBluescript SK(+) (pBK802 to pBK804 and pRK805) for sequencing with standard universal and reverse primers and primer B (see Fig. 2). All sequencing templates were purified by using QIAprep Spin Columns and were resuspended in water to a concentration of ≥200 ng/μl. When necessary, 10% glycerol or 10% dimethyl sulfoxide was added to the cycling reaction mixtures to aid sequencing through regions of complex secondary structure. Sequence data was compiled and analyzed by using the Wisconsin Package version 9 (Genetics Computer Group [GCG], Madison, Wis.).

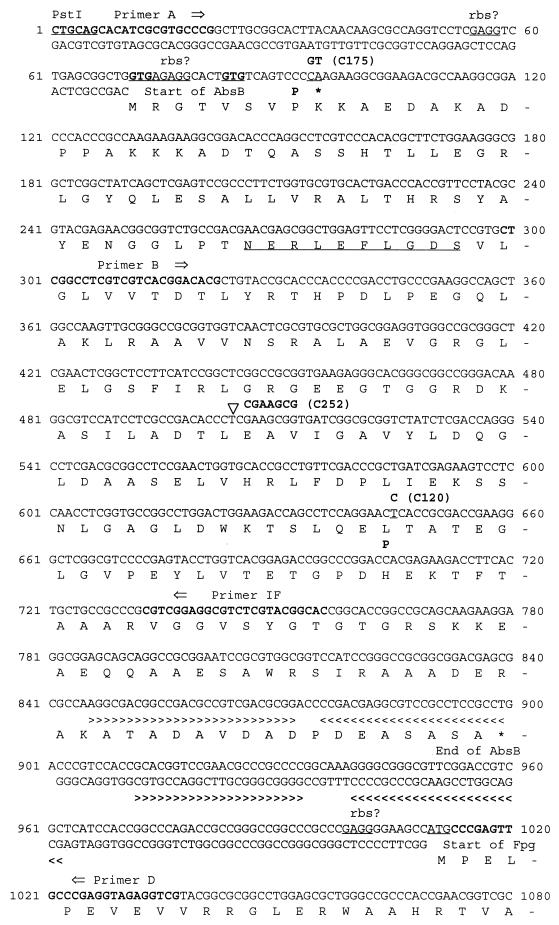

FIG. 2.

Sequence of the absB locus. Nucleotide and protein sequences of the absB gene and the 5′ end of the fpg gene are shown. PCR primer annealing sites are highlighted in boldface text. Putative ribosomal binding sites (rbs) and possible GTG start sites for AbsB and Fpg are underlined. The point mutations identified in absB mutants C120 and C175 are noted, as are the resulting amino acid changes. The frameshift in mutant C252 is also indicated. The highly conserved 10-amino-acid region common to all RNase III homologs is underlined. The double-stranded RNA binding domain, as defined in E. coli, is underlined. Stem-loop structures predicted by RNAFOLD are also indicated (>> <<).

Construction of the absB disruption mutants.

An internal fragment of the wild-type J1501 absB gene was generated by PCR with primers B and IF (see Fig. 2) to yield a 455-bp fragment. This fragment was gel purified (QIAquick), BglII digested, and ligated into pIJ963 to generate pBK314 (see Fig. 7). Unmethylated plasmid was generated from E. coli DM-1 and subsequently used to transform J1501 as well as S. lividans 1326. To increase efficiency of integrative transformation, alkali treatment of plasmid DNA was used, as described elsewhere (44). Hygr transformants were isolated, and disruption of the absB gene was confirmed by Southern hybridization by using the absB and Hygr genes as probes (data not shown).

Identifying absB homologs in other streptomycetes.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from various Streptomyces strains (27) and digested with BglII, BamHI, or PstI. Normalized amounts of digested DNA (50 μg/lane) were electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel. Southern blotting was performed as described previously (48). A 1.0-kb PstI fragment from E. coli clone pBK802 containing the wild-type absB gene was gel purified (QIAquick) and labeled with digoxigenin-UTP. Probe preparation, nonradioactive hybridization, and colormetric detection was performed by using the Genius Kit (Boehringer Mannheim) under high-stringency conditions according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

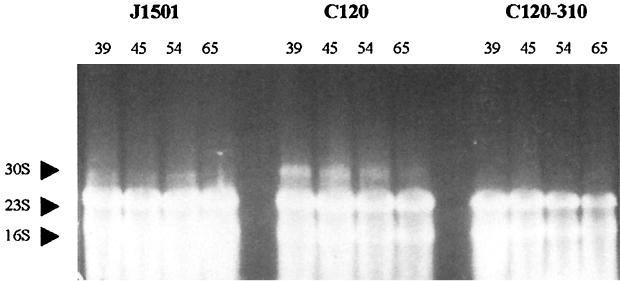

Identification of 30S precursor rRNA.

RNA samples isolated over a 65-h time course from J1501, C120 (absB), and C120-310 (absB120::pBK310) were isolated as described previously (1). Then, 50 μg of each RNA sample was run on 1.5% agarose at 25 V for 16 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The nucleotide sequence of absB has been assigned EMBL accession no. Q9ZBQ7.

RESULTS

Cloning and physical mapping of the absB locus.

Genetic analysis of a collection of absB mutants had suggested that a single mutant locus was responsible for the Abs− (e.g., Act− Red− Mmy− CDA−) phenotype of the strains (3). To clone the wild-type absB locus, a low-copy-number plasmid library of J1501 chromosomal DNA partially digested by Sau3A was screened for complementation of the C120 absB mutant strain (see Materials and Methods).

A number of clones that restored antibiotic synthesis were isolated. These clones might have contained the absB+ gene or they might have contained suppressing genes. Because of previous observations that the Act and Red biosynthesis deficiencies of absB mutants could be overcome by the introduction of extra cloned copies of certain antibiotic regulatory genes, among which were the pathway-specific regulators actII-ORF4 and redD and the pleiotropic regulator afsR (2, 14), it was important to exclude such suppressive clones from our screen for the absB+ gene.

To distinguish absB+ clones among the clones found to restore both Act and Red production, we applied several criteria. The first three of these derived from the characteristics of previously observed suppressive clones (2, 14): those clones were capable of restoring antibiotic production to diverse mutant strains, including absA, bldA, bldB, bldG, and bldH; antibiotic production occurred at a level higher than that seen in the wild-type parent strain; and the antibiotic-stimulatory effect was limited to Act and Red such that the other two antibiotics affected in absB mutants, CDA and Mmy, were not restored. Accordingly, to isolate absB+ clones, we sought clones that restored all four of the antibiotics to parental levels specifically in the absB mutants. A fourth criterion we applied to candidate absB+ clones was whether the location of the cloned DNA on the S. coelicolor physical map was consistent with that predicted by the previous genetic mapping of absB mutations (3).

Two independently isolated clones, pTA108 and pTA128, restored the production of all four antibiotics to the absB mutant C120 to levels characteristic of the J1501 parent strain. In contrast, no Act, Red, or CDA production resulted when these plasmids were transformed into other developmental mutants (Table 1) such as C542 (absA), C301 (bldA), C112 (bldB), C103 (bldG), or C109 (bldH).

Restriction mapping and Southern hybridization indicated that the inserts in pTA108 (11 kb) and pTA128 (7 kb) shared at least two internal PstI fragments. An 8.3-kb BglII fragment containing much of the insert from pTA108 was subcloned into pBluescript KS(+) and named pKJ100 (Table 2).

A physical map of ordered AseI and DraI fragments from the S. coelicolor A3(2) chromosome has been constructed and correlated with the genetic map (32). AseI digestion generates 17 fragments from chromosomal DNA, designated A to Q. To determine the chromosomal location of the cloned DNA in pKJ100, a 3.3-kb PstI fragment common to both pTA108 and pTA128 was cloned into pBK200 (Table 2), radioactively labeled, and hybridized to AseI-digested chromosomal DNA of S. coelicolor that had been separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. The probe hybridized to fragment B, which is located at roughly 5 o’clock relative to the genetic map (data not shown). This result was consistent with the genetic mapping data (2, 3) that had localized the absB mutations to the same region, between the cysD and mthB auxotrophic markers and near the genetically well-characterized bldB gene (13, 42).

Localization of absB within a complementing fragment.

To delimit the putative absB gene within the inserts of the complementing clones pTA108 and pTA128, the shared PstI fragments (which are the 3.3- and 2.6-kb PstI fragments in Fig. 1) were isolated from pKJ100 and tested for the ability to restore the wild-type phenotype (Abs+) to strain C120. Each was ligated into pBluescript KS(+) to assist in further cloning, yielding pBK200 (as described above) and pBK210, respectively. PstI fragments were then cloned from these vectors into pIJ963, an E. coli plasmid carrying an Hygr cassette suitable for selection in Streptomyces, to yield pBK300 and pBK310 (Fig. 1). Since pIJ963 cannot replicate in Streptomyces, Hygr colonies could arise only after homologous recombination within the cloned insert. Hygr colonies of the absB mutant C120 could be expected to display the Abs+ phenotype if the cloned insert contained at least one end of the absB gene and included the region spanning the absB mutation.

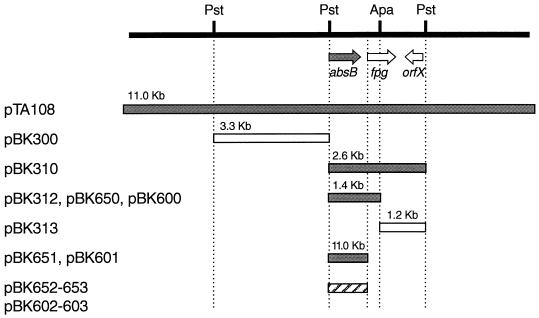

FIG. 1.

Defining absB-complementing sequences. Fragments from pTA108 used in cloning schemes outlined in the text are diagrammed. Those fragments capable of restoring the Abs+ phenotype to the absB mutants are shaded. Plasmid clones used in marker rescue experiments (pIJ963 derivatives) are designated pBK3xx, while clones derived from pIJ922 and pIJ702 are named pBK60x and pBK65x, respectively. The absB mutant alleles cloned into pIJ922 and pIJ702 that were unable to complement the absB mutants are designated by a hatched box. ORFs determined by sequence analysis are indicated by arrows. Relevant restriction sites are noted.

When pBK310 was introduced into the absB mutant C120, 39 of 40 Hygr recombinants were Abs+. In contrast, for pBK300, all of the Hygr recombinants were Abs−. This suggested that the absB+ DNA lay in the 2.6-kb PstI interval of Fig. 1. To further subdivide this interval, a convenient ApaI restriction site located within the 2.6-kb fragment was used to generate 1.4- and 1.2-kb PstI-ApaI fragments from pBK210, which were subcloned into pBluescript KS(+) to yield pBK212 and pBK213, respectively. Each insert was recovered as a KpnI-BamHI fragment and ligated into pIJ963 to yield pBK312 (1.4 kb) and pBK313 (1.2 kb) (Fig. 1). After transformation of C120, 16 of 25 of the recombinants from pBK312 were Abs+ and four of four of the pBK313 recombinants were Abs−. These results suggested that absB+ DNA was contained within the 1.4-kb PstI-ApaI fragment and may have been truncated or lacked the promoter.

To obtain some indication as to whether the 1.4-kb PstI-ApaI fragment had the ability to complement absB mutations in trans, the autonomously replicating Streptomyces plasmids pIJ702 (high copy number) and pIJ922 (low copy number) were used. The 1.4-kb PstI-ApaI fragment was cloned into pIJ2925, and a BglII fragment was recovered and cloned into both pIJ702 and pIJ922. Recombinant plasmid DNAs from both the low-copy-number pIJ922 clone (named pBK600) and the high-copy-number pIJ702 clone (pBK650) were then used to transform C120. All of the transformants grew as uniformly Abs+ colonies, suggesting that the 1.4-kb fragment contained the complete absB+ gene and did not require recombinational repair with the chromosome to produce a functional gene. Both pBK600 and pBK650 complemented other absB mutants as well. These results further suggested that all of the absB mutations had created recessive, loss-of-function alleles.

DNA sequence analysis of the 2.6-kb PstI fragment in pBK310 revealed three open reading frames (ORFs) by using CODON PREFERENCE (Fig. 1). The 3′ end of the 2.6-kb fragment contained a truncated 306-bp ORF, designated orfX, that showed no homology to any sequences in the protein databases. A second ORF, spanning the ApaI site in Fig. 1, showed homology (57.5% similarity and 31.6% identity) to several formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (fpg) genes in the databases. The Fpg protein (also named MutM in E. coli) is a DNA repair enzyme that excises the imidizole ring-opened form of N7-methylguanine from damaged DNA (7). We have similarly designated this ORF fpg.

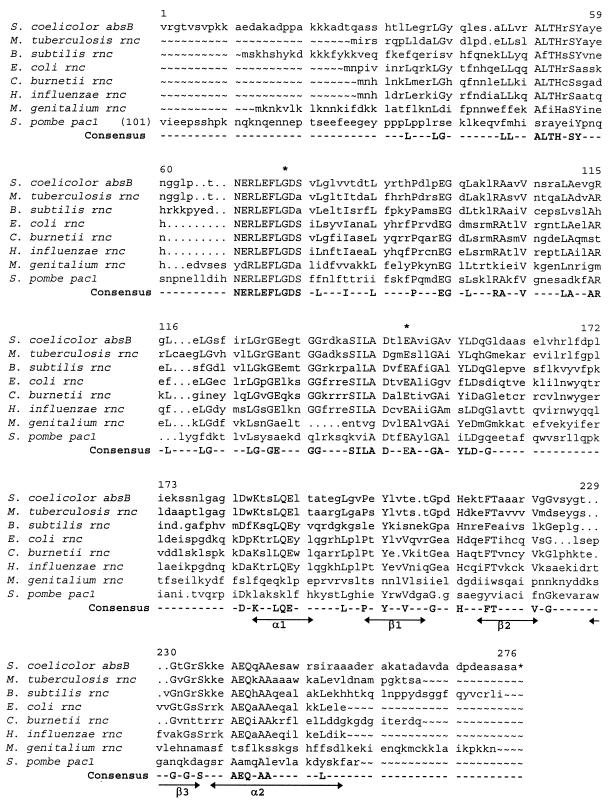

A third ORF (Fig. 2) was found to be contained entirely within the 1.4-kb PstI-ApaI fragment that recombinationally rescued and complemented absB mutants as discussed above; it therefore was a strong candidate for the absB gene. This 276-amino-acid ORF showed 41% identity to E. coli RNase III (Fig. 3), which is encoded by the rnc gene. Several other RNase III homologs were also found in the databases; amino acid alignments of six of these homologs are shown in Fig. 3. The double-stranded RNA binding domain (31) is strictly conserved in the S. coelicolor sequence, as are all of the functionally significant residues defined for the E. coli RNase III homolog (Fig. 3), notably, a 10-amino-acid box containing the amino acid which is altered in the well-studied rnc105 allele (42a), as well as the nearly invariant glutamic acid residue altered in the rnc70 allele (27a).

FIG. 3.

Amino acid alignment of AbsB and RNase III homologs. Homologs are listed in the order of highest identity to AbsB (M. tuberculosis, 62.2%; B. subtilis, 40.9%; E. coli, 40.9%; C. burnetii, 39.7%; H. influenzae, 38.6%; M. genitalium, 35.0%; and S. pombe, 27.3%). Amino acid numbering is based on AbsB sequence (first 100 amino acids of S. pombe pac1 not shown) and was compiled by using PILEUP (University of Wisconsin GCG Group Package, version 9). The consensus is noted for amino acids conserved in ≥5 homologs. The dsRBD as defined for E. coli (α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 [31]) is noted; α-helices and β-sheets are highlighted with arrows. ∗, locations of amino acids altered in E. coli alleles rnc105 (G in a highly conserved 10-amino-acid box) and rnc70 (a highly conserved E).

Identification of the absB gene.

Of the ORFs located within the sequenced region, the one encoding the RNase III homolog was the best candidate for the absB gene. To specifically test this ORF for complementation of absB mutations, PCR primers A and D (Fig. 2) were used to generate a 1,046-bp fragment from wild-type strain J1501 which would contain the RNase III ORF and the noncoding regions on either side of the gene. The BglII-digested fragment’s sequence was confirmed, and it was ligated with the high-copy-number plasmid pIJ702. A representative plasmid, pBK651, was transformed into C120; it gave 100% Abs+ colonies (n = 264). Subsequent transformation into other absB mutants, C175 and C170, gave similar results. The BglII fragment from pBK651 was also cloned into low-copy-number pIJ922; the resulting clone, pIJ601, was able to restore the Abs+ phenotype to each of the absB mutants.

To determine whether absB mutants contained mutational alterations to the RNase III-like gene, this gene was sequenced in three absB mutants: C120, C252, and C175 (Table 1). Primers A and D (Fig. 2) were used to amplify the 1,046-bp fragment corresponding to that amplified from J1501 as described above; each reaction generated a fragment the same size as the J1501 fragment, indicating that no major deletions of the locus were responsible for the Abs− phenotype. PCR fragments generated in replicate from independent amplification reactions were sequenced. Sequence comparisons showed that the sequence amplified from each mutant contained an alteration (Fig. 2) and that these mutations could predictably disrupt the production or function of an RNase III-like protein. Strain C120 contained a C→T transition that would change Leu172 to a proline residue. This amino acid lies within the first α-helix of the putative double-stranded RNA binding domain (dsRBD) (32); the presence of a proline residue would likely disrupt the structural integrity of an α-helix. The C175 allele contained two adjacent base-pair changes, the second of which resulted in a nonsense mutation at Lys8. The C252 allele contained a 7-bp duplication of nucleotides (nt) 505 to 511; hence, this mutation would introduce a frameshift.

Two of the PCR-amplified absB mutant alleles were cloned into pIJ702 in both orientations for complementation testing. Representative clones were named pBK652 (absB120) and pBK653 (absB175). Unlike the wild-type allele, neither mutant allele was able to complement the absB mutant phenotype (C120, n = 137; C175, n = 88), as expected.

Genetic organization of the absB locus.

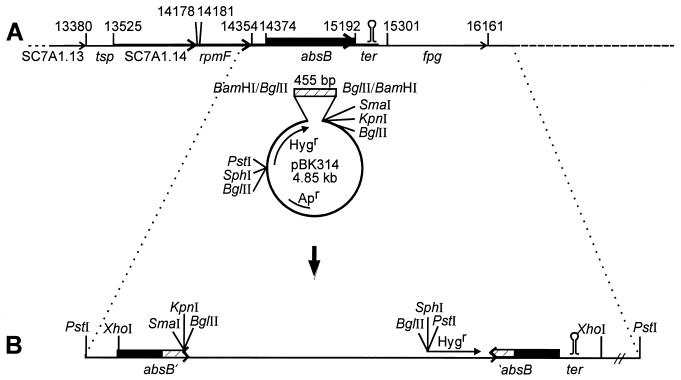

Comparison of the absB sequence to the S. coelicolor genome sequence (49) revealed that absB lay within cosmid 7A1 (46). The locations of neighboring ORFs suggested a possible absB operon structure: this may include the two ORFs upstream of absB (Fig. 4A). The ORF left of absB is predicted to encode the 50S ribosomal protein L32 and hence would be named rpmF; these two ORFs are separated by 20 nt and therefore may be cotranscribed. The ORF left of the rpmF gene (SC7A1.14) corresponds to an unknown Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene (49). This ORF is separated by only 3 nt from rpmF and so is likely to be cotranscribed with rpmF and absB. The region separating SC7A1.14 from the next neighboring (leftwards) ORF (SC7A1.13), which encodes another unknown protein, is 145 nt: this distance suggests independent transcription of the two genes. Finally, the 110-nt intergenic region separating absB from the rightwards fpg ORF contains a 20-bp perfect inverted repeat likely to function as a terminator of the absB transcript.

FIG. 4.

(A) Genetic organization of the S. coelicolor absB locus. Coordinates of the ORFs shown are those of the Sanger Center S. coelicolor Sequencing Project (49). The sequencing project ORF names are also shown. absB corresponds to ORF SC7A1.16. ter indicates the stem-loop, likely to be a terminator, shown in Fig. 2. tsp indicates a potential location for a transcription start site. (B) Disruption of the S. coelicolor absB gene by integration of pBK314 (see Materials and Methods). The zigzag indicates truncation of the absB coding region.

If the promoter that is responsible for absB transcription lies upstream of SC7A1.14 (Fig. 4), then the absB-complementing subclones shown in Fig. 1 and discussed above would lack the native promoter but could have been transcribed from vector promoters.

Disruption of absB in S. coelicolor and S. lividans.

Despite the important functions of RNase III in processing ribosomal precursor RNAs, as well as many cellular RNAs, E. coli RNase III is not essential for viability (6, 53). In contrast, the Bacillus subtilis rnc gene could not be disrupted (55). Therefore, it was of interest to evaluate whether S. coelicolor required absB function. The viability of the nonsense and frameshift absB mutant strains, C175 and C252, respectively, strongly predicted that absB was not essential to S. coelicolor. However, it was conceivable that these strains might contain suppressive mutations. Therefore, a constructed disruption of the absB gene was produced.

To create a disruption in the absB gene, a 455-bp fragment internal to the gene was amplified by using primers B and IF (Fig. 2), as described in Materials and Methods. The fragment was ligated into pIJ963, a plasmid lacking a Streptomyces replicon (Table 1), to produce pBK314 (Fig. 4). A single crossover via homologous recombination of the cloned absB fragment and the chromosomal absB gene would create two truncated copies of absB flanking the plasmid vector (Fig. 4B). The absB 3′ truncation would eliminate the dsRNA binding motif, and the absB 5′ truncation would be expected to eliminate transcription and, moreover, the N-terminal 10-amino-acid conserved motif of any residually produced protein.

A representative S. coelicolor J1501 absB disruptant, named C23, displayed a phenotype much like that of the C175 and C252 nonsense and frameshift strains, being deficient in antibiotic production but able to form a sporulating aerial mycelium. These strains’ antibiotic-minus phenotype was more severe than that of the C120 missense strain, especially on complex media such as R5. Although C120 grew as well as the J1501 parent, C23, C175, and C252 formed smaller colonies on both R5 medium and minimal SMMS medium.

A representative disruptant of S. lividans 1326, named C24, also displayed an Abs− phenotype, failing to produce any observable pigment, but forming a sporulating aerial mycelium.

absB is conserved in various streptomycetes.

To determine whether the absB gene is conserved across species, a 1.0-kb PstI fragment from clone pBK802, containing the entire absB ORF, was used to probe the chromosomal DNA of various streptomycetes (data not shown). A PstI digest of prototrophic strain S. coelicolor M600 and PstI and BglII digests of the S. coelicolor parent strain J1501 were used as positive controls. For each digest, a single band was visible at 2.6 or 8.1 kb respectively, as predicted from the pTA108 restriction map (Fig. 1), indicating a single RNase III-encoding gene in S. coelicolor. In other streptomycete species, a single BamHI fragment hybridized to the probe under high-stringency conditions; fragments from Streptomyces albus (2.4 kb), Streptomyces ambofaciens 2035 (6.5 kb), Streptomyces avermitilis (9.1 kb), and Streptomyces cinnamonium (8.8 kb) were detected. The hybridization conditions used (0.5× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C) predictably exclude probe binding under 90% homology according to the manufacturer. The identity between the absB genes of S. coelicolor and the actinomycete M. tuberculosis is 62.2%, and it is not surprising that like genes of the streptomycetes would have greater degrees of homology.

30S rRNA precursors in absB mutant strain.

One distinguishing characteristic of an E. coli rnc mutant is the presence of the 30S precursor rRNA in total RNA preparations (6, 21). This precursor accumulates only in RNase III-minus mutants, owing to inefficient processing in the absence of the enzyme. To determine whether rRNA processing was deficient in an absB mutant, RNAs isolated at various time points from J1501, C120, and the Abs+ recombinant C120-310 were run on a 1.5% agarose gel. At each time point, an additional rRNA band with migration consistent with 30S rRNA (6) was seen in the absB mutant but not in either Abs+ strain (Fig. 5). The abundance of 30S precursor decreased at later times, an effect also observed in two independently isolated RNA time courses. This result provided evidence that the putative Streptomyces RNase III homolog has retained the rRNA processing function defined for other RNase III enzymes and that this function is inhibited in the absB mutant strain C120.

FIG. 5.

rRNA processing in the absB mutant. Normalized concentrations of RNA from wild-type strain J1501, absB mutant C120, and C120 rescued to the wild-type phenotype with pBK310 (C120-310) were isolated from four time points (shown as hours of culture incubation) and run on a 1.5% agarose gel at low voltage for 16 h and then stained with ethidium bromide. Sporulation occurred by 54 h in all strains. Antibiotic production was also evident by 54 h in J1501 and C120-310.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified and partially characterized the S. coelicolor absB gene and have presented evidence that it encodes the S. coelicolor homolog of RNase III, a dsRNA-specific endoribonuclease. Through recombinational rescue and complementation experiments, we have shown that S. coelicolor absB mutants can be restored to the wild-type Abs+ phenotype by the introduction of the wild-type RNase III-like gene. Sequence analysis of three absB mutant strains showed that each harbors a mutation in the putative RNase III-encoding gene. One mutation is an N-terminal nonsense mutation, the second introduces a frameshift upstream of the predicted dsRNA-binding motif, and the third would likely alter the secondary structure of the dsRNA-binding motif. In addition, disruption of the absB gene produced a mutant with a tight Abs− phenotype, e.g., the strain produced no detectable antibiotics but did sporulate like its parental strain, J1501.

What is the mechanism by which absB regulates production of all four S. coelicolor antibiotics? Previous work has shown that the defect in antibiotic production in absB mutants is at least partially the result of a defect in expression of the antibiotic genes (1). The levels of transcripts expressed from the actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin gene clusters, including act biosynthetic transcripts and the antibiotic-pathway-specific regulators actII-ORF4 and redD, were found to be notably decreased by the absB120 missense mutation. (We do not know if the C175, C252, and C23 strains would show even stronger effects on antibiotic gene expression.) Moreover, extra plasmid-cloned copies of actII-ORF or redD restored, respectively, abundant Act or Red production to absB mutants (2, 14). Perhaps AbsB is needed for stabilization of the pathway-specific regulator transcripts, possibly to achieve a certain threshold level, after which antibiotic biosynthetic gene transcription can occur. Alternatively, AbsB may regulate a regulator of actII-ORF4 and redD transcription. It should be noted that this work does not distinguish whether RNase III in S. coelicolor directly regulates antibiotic gene expression by specific mRNA processing or whether the antibiotic gene expression defect of the absB mutants is an indirect effect. However, the ability of the absB mutants to sporulate normally indicates the absence of a global perturbation to colony development and differentiation. Thus, absB may affect expression of a gene required for expression of the set of pathway-specific regulators.

Prediction of candidate targets for S. coelicolor RNase III is difficult: although many RNase III processing targets have been identified in E. coli and other systems, the specific structural and sequence determinants required for RNase III-dependent cleavage have eluded definition. Most substrates contain an ∼20-bp double-helical region. Stem-loop structures are found in almost all RNA molecules, but the vast majority are not processed by RNase III. RNase III apparently does not respond to a consensus sequence as a processing substrate. Rather, recent work suggests that certain Watson-Crick base pairs at specific sites in an RNase III substrate function as RNase III antideterminants, inhibiting enzymatic cleavage (56). In vivo, the wild-type RNase III may even be able to influence gene expression as a result of binding RNA, without RNA processing, as suggested in the case of cIII and int regulation in phage λ (20, 45).

RNase III has been best characterized in E. coli, where it was first identified by its ability to degrade long duplex RNA (reviewed in reference 19). Later, RNase III was shown to process phage T7 mRNA and to initiate the processing of the 30S rRNA precursor into the mature 16S and 23S subunits. The 30S rRNA precursor is seen only in strains devoid of RNase III activity, since the processing occurs very rapidly during transcription in wild-type strains.

In an initial functional characterization of the putative RNase III in S. coelicolor, we analyzed preparations of rRNA from the wild-type J1501 and the C120 absB mutant strain: a large RNA corresponding in size to the 30S rRNA precursor was seen in the absB mutant C120 but not in the wild-type J1501 or in C120 recombinationally rescued to the Abs+ phenotype with pBK310 (C120-310). This result suggested that the absB gene product processes 30S precursor rRNA in addition to its function in antibiotic production.

The gene that encodes RNase III in E. coli, rnc, is not essential for growth. In rnc mutant strains, the mature 16S rRNA is formed by a redundant mechanism and, although mature 23S rRNA never forms, the 50S ribosomes containing immature pre-23S rRNA are competent for translation (34). E. coli rnc mutants grow at a lower rate than rnc+ strains, with the extent of the growth defect varying depending on the culture medium and genetic background (6). In S. coelicolor, we have observed a smaller colony size in absB mutants, not only in the C23 absB disruption strain but also in the absB nonsense mutant C175 and the absB frameshift mutant C252, compared to those of the wild-type J1501 and the absB missense mutant C120. In contrast to E. coli and S. coelicolor, the B. subtilis RNase III may be essential for viability since extensive attempts to construct a null mutant were unsuccessful (55).

It is notable that the genetic organization of the absB locus is quite different than the E. coli or B. subtilis rnc operon structures. The B. subtilis operon organization is rnc smc srb (43); SMC is a chromosome condensing protein, and srb is a homologue of the mammalian SRP receptor α-subunit. In E. coli, rnc is cotranscribed (53) with era, an essential gene that encodes a GTPase involved in cell cycle progression, and with recO.

Besides its role in rRNA processing, RNase III affects the half-life and functional activity of numerous mRNAs. It has been estimated that the abundance of as many as 10% of E. coli proteins detectable by gel analysis are either under- or overproduced in the well-characterized rnc105 mutant (24). Through endonucleolytic cleavage of stem-loop structures within the 5′ or 3′ noncoding regions of certain mRNAs, RNase III is able to up- or downregulate the expression of genes posttranscriptionally (19). In some examples from phage, RNase III has been shown to cleave stem-loops in the leader RNA of the N protein transcript and in the 3′ end of the int gene transcript. Processing enhances λN gene expression by opening up a Shine-Dalgarno sequence for translation initiation but reduces λint gene expression by exposing the transcript to exonucleolytic degradation. The T7 phage early and late gene transcripts have RNase III processing signals in intercistronic regions; specific cleavages yield mature mRNAs that have increased translational activity and stability. In an exmaple from E. coli, RNase III processing of the alcohol dehydrogenase mRNA (adhE) is essential for its translation and, hence, for cell growth in anaerobic conditions (5a).

Among the E. coli cellular genes regulated by RNase III is rnc itself. This autoregulation involves processing of the rnc transcript’s 5′ leader (41). Measurements of RNase III protein levels suggest that RNase III molecules are present in an amount similar to that of ς factor (reviewed in reference 19). Fluctuations in substrate levels, especially rRNA, may therefore affect RNase III levels. Additional RNase III-independent, posttranscriptional, growth rate controls on RNase III levels have also been observed (11).

It will be interesting to determine whether the level or activity of the S. coelicolor absB gene or gene product varies with respect to growth phase. If absB is transcribed as part of an operon with the ribosomal protein rpmF (Fig. 4), regulation at that promoter would not be expected. However, a potential target for posttranscriptional autoregulation is the long stem-loop 3′-wards of the gene (Fig. 2).

The RNase III homologue described here adds to the growing list of streptomycete mRNA processing enzymes identified: others include polynucleotide phosphorylase (30) and RNase ES (26), a single-strand-specific endoribonuclease that has E. coli RNase E-like cleavage specificity and biochemical characteristics. These enzymes’ in vivo substrates have not yet been identified, but an interesting observation regarding RNase ES is that its activity increases as S. coelicolor cultures age. Moreover, the increase is dependent on a developmental gene, bldA (35), suggesting that the RNase E-like enzyme activity may be important to developmental regulation. Clearly, further analyses of the roles of RNA processing enzymes will be important in understanding developmental regulation.

Considering the wide distribution of putative RNase III genes among various streptomycetes, it will be interesting to determine whether mutations to the homologous genes perturb antibiotic synthesis, as occurs in S. coelicolor and its close relative, S. lividans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Helen Kieser for assistance in running the pulsed-field gels, Kelly Spencer for her contributions to restriction site mapping, Dave Aceti for RNA isolations, and Paul Brian and Jamie Ryding for assistance with sequence analysis.

This work was supported by grants MCB9306676 and MCB9604055 to W.C. from the National Science Foundation. B.P. received support from a National Institutes of Health Biotechnology Training Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aceti D J, Champness W C. Transcriptional regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor pathway-specific antibiotic regulation by the absA and absB loci. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3100–3106. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3100-3106.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamidis A. Ph.D. dissertation. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamidis T, Champness W. Genetic analysis of absB, a Streptomyces coelicolor locus involved in global antibiotic regulation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4622–4628. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4622-4628.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamidis T, Riggle P, Champness W. Mutations in a new Streptomyces coelicolor locus which globally block antibiotic biosynthesis but not sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2962–2969. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2962-2969.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apirion D, Watson N. Mapping and characterization of a mutation in Escherichia coli that reduces the level of ribonuclease III specific for double-stranded ribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:317–324. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.317-324.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Aristarkov A, Mikulskis A, Belasco J G, Lin E C C. Translation of the adhE transcript to produce ethanol dehydrogenase requires RNase III cleavage in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4327–4332. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4327-4332.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babitzke D, Granger L, Olszewski J, Kushner S R. Analysis of mRNA decay and rRNA processing in Escherichia coli multiple mutants carrying a deletion in RNase III. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:229–239. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.229-239.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardwell J C, Regnier P, Chen S M, Nakamura Y, Grunberg-Manago M, Court D L. Autoregulation of RNase III operon by mRNA processing. EMBO J. 1989;8:3401–3407. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bibb M. 1995 Colworth Prize Lecture. The regulation of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiology. 1996;142:1335–1344. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boiteux S, Gajewski E, Laval J, Dizdaroglu M. Substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli Fpg protein (formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase): excision of purine lesions in DNA produced by ionizing radiation or photosensitization. Biochemistry. 1992;31:106–110. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brian P, Riggle P J, Santos R A, Champness W C. Global negative regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic synthesis mediated by an absA-encoded putative signal transduction system. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3221–3231. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3221-3231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britton R A, Powell B S, Dasgupta S, Sun Q, Margolin W, Lupski J R, Court D L. Cell cycle arrest in Era GTPase mutants: a potential growth rate regulated cell cycle checkpoint in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:739–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraburtty R, Bibb M. The ppGpp synthetase gene (relA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) plays a conditional role in antibiotic production and morphological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5854–5851. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5854-5861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champness W C. New loci required for Streptomyces coelicolor morphological and physiological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1168–1174. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1168-1174.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champness W, Riggle P, Adamidis T, Vandervere P. Identification of Streptomyces coelicolor genes involved in regulation of antibiotic synthesis. Gene. 1992;115:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champness, W. C., and K. F. Chater. 1994. Regulation and integration of antibiotic production and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces spp., p. 61–93. In P. J. Piggot, J. Moran, C. P., and P. Youngman (ed.), Regulation of bacterial differentiation. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Chang H-M, Chen J Y, Shieh Y T, Bibb M J, Chen C W. The cutRS signal transduction system of Streptomyces lividans represses the biosynthesis of the polyketide antibiotic actinorhodin. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1075–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chater K F. Taking a genetic scalpel to the Streptomyces colony. Microbiology. 1998;144:1465–1478. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-6-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chater K F, Bibb M J. Regulation of bacterial antibiotic production. In: Kleinkauf H, von Döhren H, editors. Products of secondary metabolism. Vol. 6. 1997. pp. 57–105. (Biotechnology). VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Court D. RNA processing and degradation by RNase III. In: Belasco J G, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasgupta S, Fernendez L, Kameyama L, Inada T, Kakamura Y, Pappas A, Court D L. Genetic uncoupling of the dsRNA binding and RNA cleavage activities of the Escherichia coli endoribonuclease RNase III—the effect of dsRNA binding on gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:629–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn J J, Studier F W. T7 early RNAs and Escherichia coli ribosomal RNAs are cut from large precursor RNAs in vivo by ribonuclease 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:3296–3300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernendez-Moreno M A, Martin-Triana A J, Martinez E, Niemi J, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. abaA, a new pleiotropic regulatory locus for antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2956–2967. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2958-2967.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floriano B, Bibb M J. afsR is a pleiotropic but conditionally required regulatory gene for antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:385–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6491364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gitelman D R, Apirion D. The synthesis of some proteins is affected in RNA processing mutants of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;96:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gramajo H E, Takano E, Bibb M J. Stationary phase production of the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) is transcriptionally regulated. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:837–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagige J M, Cohen S N. A developmentally regulated Streptomyces endoribonuclease resembles ribonuclease E of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1077–1090. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5311904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. 1st ed. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Inada T, Kawakami K, Chen S, Takiff H, Court D, Nakamura Y. Temperature-sensitive lethal mutant of Era, a G-protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5017–5024. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5017-5024.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishizuka H, Horinouchi S, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A, Beppu T. A putative two-component regulatory system involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7585–7594. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7585-7594.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janssen G R, Bibb M J. Derivatives of pUC18 that have BglII sites flanking a modified multiple cloning site and that retain the ability to identify recombinant clones by visual screening of Escherichia coli colonies. Gene. 1993;124:133–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90774-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones G H, Bibb M J. Guanosine pentaphosphate synthetase from Streptomyces antibioticus is also a polynucleotide phosphorylase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4281–4288. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4281-4288.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharrat A, Macias M J, Gibson T J, Nilges M, Pastore A. Structure of the dsRNA binding domain of E. coli RNase III. EMBO J. 1995;14:3572–3584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kieser H M, Kieser T, Hopwood D A. A combined genetic and physical map of the Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5496–5507. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5496-5507.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kieser, T. Personal communication.

- 34.King T C, Sirdeshmukh R, Schlessinger D. RNase III cleavage is obligate for maturation but not for function of Escherichia coli pre-23S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:185–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawlor E J, Baylis H A, Chater K F. Pleiotropic morphological and antibiotic deficiencies result from mutations in a gene encoding a tRNA-like product in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Genes Dev. 1987;1:1305–1310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lydiate D J, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A. The Streptomyces plasmid SCP2*: its functional analysis and development into useful cloning vectors. Gene. 1985;35:223–235. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacNeil D J, Gewain K M, Ruby C L, Dezeny G, Gibbons P H, MacNeil T. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene. 1992;111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Costa O, Arian H P, Romero N M, Parro V, Mellado R P, Malpartida F. A relA/spoT homologous gene from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) controls antibiotic biosynthetic genes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10627–10634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto A, Hong S K, Ishizuka H, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Phosphorylation of the AfsR protein involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species by a eukaryotic-type protein kinase. Gene. 1994;146:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto A, Ishizuka H, Beppu T, Horinouchi S. Involvement of a small ORF downstream of the afsR gene in the regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Actinomycetologica. 1995;9:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsunaga J, Simons E L, Simons R W. RNase III autoregulation: structure and function of rncO, the posttranscriptional “operator.”. RNA. 1996;2:1228–1240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merrick M J. A morphological and genetic mapping study of bald colony mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;96:299–315. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-2-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.Nashimoto H, Uchida H. DNA sequencing of the Escherichia coli ribonuclease III gene and its mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00397981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oguro A, Kakeshita H, Takamatsu H, Nakamura K, Yamane K. The effect of Srb, a homologue of the mammalian SRP receptor α-subunit, on Bacillus subtilis growth and protein translocation. Gene. 1996;172:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh S H, Chater K F. Denaturation of circular or linear DNA facilitates targeted integrative transformation of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): possible relevance to other organisms. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:122–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.122-127.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oppenheim A, Kornitzer O, Altuvia S, Court D. Posttranscriptional control of the lysogenic pathway in bacteriophage lambda. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1993;46:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redenbach M, Kieser H M, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood D A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito H, Richardson C C. Processing of mRNA by ribonuclease III regulates expression of gene 1.2 of bacteriophage T7. Cell. 1981;27:533–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanger Center Streptomyces coelicolor Sequencing Project. [Online.] Sanger Center. http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/. [31 August 1999, last date accessed.]

- 50.Schen A-K, Martínez E, Soliveri J, Malpartida F. abaB, a putative regulator for secondary metabolism in Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;177:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takano E, Gramajo H C, Strauch E, Andres N, White J, Bibb M J. Transcriptional regulation of the redD transcriptional activator gene accounts for growth-phase-dependent production of the antibiotic undecylprodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2797–2804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takiff H E, Chen S M, Court D L. Genetic analysis of the rnc operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2581–2590. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2581-2590.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vogtli M, Chang P-C, Cohen S N. afsR: a previously undetected gene encoding a 63-amino-acid protein that stimulates antibiotic production in Streptomyces lividans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:643–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang W, Bechhofer D H. Bacillus subtilis RNase III gene: cloning, function of the gene in Escherichia coli, and construction of Bacillus subtilis strains with altered rnc loci. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7379–7385. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7379-7385.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang K, Nicholson A W. Regulation of ribonuclease III processing by double-helical sequence antideterminants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13437–13441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]