Abstract

Pain, one of the most important problems in the field of medicine and public health, has great research significance. Opioids are still the main drugs to relieve pain now. However, its application is limited due to its obvious side effects. Therefore, it is urgent to develop new drugs to relieve pain. Multiple studies have found that IGF/IGF-1R pathway plays an important role in the occurrence and development of pain. The regulation of IGF/IGF-1R pathway has obvious effect on pain. This review summarized and discussed the therapeutic potential of IGF/IGF-1R signal pathway for pain. It also summarized that IGF/IGF-1R regulates pain by acting on neuronal excitability, neuroinflammation, glial cells, apoptosis, etc. However, its mechanisms of occurrence and development in pain still need further study in the future. In conclusion, although more deep researches are needed, these studies indicate that IGF/IGF-1R signal pathway is a promising therapeutic target for pain.

Keywords: Pain, IGF/IGF-1R pathway, Neuronal excitability, Neuroinflammation, Glial cell

1. Introduction

Pain is a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon, which is redefined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in 20201. Pain is mainly divided into acute pain and chronic pain according to the time definition. Acute pain, mainly caused by surgery, influences early mobilization as a prerequisite for improving recovery and reducing the risk of complications2. Acute severe pain increases the risk of transition to chronic postoperative pain3, 4 as well as the occurrence of postoperative delirium5. Therefore, it is particularly important to control acute pain in time. While chronic pain, as one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care, has a prevalence rate between 11% and 40%, which seriously affects the quality of patients' life6. It is estimated that 20.4% (50 million) of American adults suffer from chronic pain6. In addition to suffering from pain, chronic pain is also prone to comorbidity such as anxiety, depression and sleep disorders7-10. The economic cost of chronic pain is enormous. A report released by the Medical Research Institute in 2010 estimated that chronic pain afflicts about one third of Americans, causing medical expenses and productivity losses of 560 to 635 billion dollars each year11. Therefore, pain, as one of the most important problems in the field of medicine and public health, has great research significance. To date, the mechanisms of pain have not been clearly studied, so it is urgent to understand the mechanisms of pain in order to conduct better treatment.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF), the primary effector of the growth hormone (GH) axis, is an anabolic hormone produced mainly in the liver. It can also be produced by local autocrine and paracrine, such as skeletal myogenic cells12, ventricular fibroblasts13, glial cells14. It involves in regulating biological activities related to GH, such as insulin metabolism and cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis15. Existing studies have found that IGF plays an important role in various human diseases. Several studies show that IGF-1 is closely related to the metabolism of cancer16-19. The abnormal levels of IGF are associated with increased risk of diabetes20-23 and cardiovascular disease24-26. Besides, clinical evidence and animal studies indicate the role of IGF/GH pathway involved in the process of longevity and aging27-29. More research found that IGF has nutritional and anti-apoptotic effects on neurons and muscle cells30-33. In addition, whether acute or chronic pain, IGF plays an important role in its occurrence and development34, 35.

In this review, we emphasized the latest progress in understanding the mechanisms of IGF in acute and chronic pain, focusing on how IGF affects pain through changes in neuronal excitability, neuroinflammation, and glial cells. It clarifies the different roles of IGF in different pain types and different regions, and provides new ideas and targets for future pain treatment.

2. The overview of IGF/IGF-1R pathway

IGF system includes an ancient peptide family, which involves mammalian growth, development and metabolism, as well as cell processes, such as proliferation, survival, cell migration and differentiation. IGF family includes three known ligands (IGF-I, IGF-2 and insulin), six characteristic insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP-1-6) and cell surface receptors (IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IGF-II mannose 6-phosphate receptor) that mediate ligand action36-38. IGF acts through circulation and local secretion39. These molecules constitute a complex autocrine/paracrine network to regulate cell proliferation, survival and differentiation39. Among them, IGF-1 and IGF-2 are reported to be related to pain at present. IGF-1 is a single polypeptide chain consisting of 70 amino acids, which has a binding affinity to IGF-IR 100-fold higher than insulin. IGF-2 is composed of 180 amino acids. It also binds to IGF-IR with a binding affinity comparable to IGF-140, 41.

IGF-1 and IGF-2 are mainly mediated by IGF receptor type 1 (IGF-1R) to regulate pain. IGF-1R was first proved to exist in 197442. IGF-1R can be shown by SDS gel electrophoresis and consists of two α and two β chains linked together by disulfide bonds40, 43. When expressed in the presence of monensin, an inhibitor of posttranslational processing, the IGF-1R was proved to be synthesized as a 180-kDa precursor, which is glycosylated, dimerized and proteolytically to produce the mature α2β2 receptors. The next key finding is that IGF-1R, like insulin receptor (IR), is a tyrosine kinase which is activated and autophosphorylated following IGF binding44. The IGF-1R has a similar structure to the insulin receptor. The insulin receptor (and related IGF-1R) is a covalent dimer transmembrane allosteric enzyme45. IGF-1R is a member of the transmembrane tyrosine kinase family, including IR and orphan insulin receptor related receptor (IRR). It binds IGF-1 with high affinity and starts the physiological response to the ligand in vivo46. IGF-1R also binds to IGF-2, plays a part in the mitogenic effect of this polypeptide during fetal development47. The extracellular α-subunit forms IGF-1 binding pockets, while the intracellular domain (amino acids 956-1256) of the membrane-spanning β-subunit contains a kinase domain48, 49. Once activation, the tyrosine kinase activity of IGF-1R results in a continuous phosphorylation event at residues Y1135, Y1131, and Y1136, producing conformational changes in β subunits to create conformational changes occur in subunits, creating docking sites for downstream signal molecules and their phosphorylation49. The activation of IGF-1R triggers multiple signal cascades in a cell context dependent manner to regulate multiple cellular functions from proliferation and survival to differentiation into specific cell lineages39.

3. The relationship between IGF/IGF-1R and pain

3.1. The expression of IGF/IGF-1R in pain related regions

Multiple evidence indicates that IGF/IGF-1R can be expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG)50, 51, spinal dorsal horn52, 53 and brain54-56. These areas are closely related to pain. Dai et al found that IGF-1 immunoreactive products showed strongly stained brown deposits in the cytoplasm of large, medium and small DRG neurons. In layer II of L3 and L6 spinal cord, IGF-1 immunoreactive products were found in the nuclei of some neurons and glial cells52. IGF-1 and its receptor are preferentially expressed in DRG neurons harvested from sciatic nerve axotomy and streptozotocin (STZ) induced painful neuropathy in diabetes57. Besides, Takayama also reported that colocalization of IGF-1 in DRG is expressed in the neuronal bodies and fibers. IGF-1 is collocated with neuron, but not with satellite glial cell (SGC) of DRG in a rat disc herniation model58. However, single cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing and in situ hybridization analysis showed high expression of endogenous IGF-1 in non peptidergic neurons and SGC of DRG59, 60. IGF-1 expression in cerebral cortex and DRG was higher than that in sciatic nerve in mice59, 60. Besides, IGF-1R also widely expressed in hippocampus61-63 and frontal cortex64-66. In summary, IGF/IGF-1R are widely expressed in sites closely related to pain (DRG, spinal cord and brain), so we reasonably speculate that they are closely related to the occurrence and development of pain.

3.2. The role of IGF/IGF-1R in pain

3.2.1. The IGF/IGF-1R pathway involved in aggravating acute pain

IGF/IGF-1R pathway plays an important role in acute pain (Table 1). Local administration of IGF-1 induces thermal and mechanical pain hypersensitivity in a dose-dependent manner, which is attenuated by inhibition of IGF-1R inhibitor picropodophyllin (PPP, 50 μg)34. In addition, the author also found that after plantar incision, the level of IGF-1 in tissues, but not in plasma, increased significantly. IGF-1R inhibitor (PPP, 50 μg) successfully alleviated mechanical allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and spontaneous pain behavior observed after plantar incision34. Another study also showed that intraplantar recombinant IGF-1 (rIGF-1, 50 μg/kg) developed hyperalgesia 2 hours later in mice. This IGF-1-induced hypersensitivity response is attenuated by pretreatment with IGF-1R antagonists (JB1, 6 μg)67. Clinical experiments also found that the serum IGF-2 level in patients with acute myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) was lower than that in healthy control group, with no gender difference, while the IGF-1 level in each group had no difference68. Above all, the dysregulation of IGF/IGF-1R can promote the occurrence of a variety of acute pain, and inhibition of their expression can relieve acute pain.

Table 1.

The pain model, expression, localization of the IGF/IGF-1R aggravating the pain.

| IGF/IGF-1R | Pain model | Expression | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF/IGF-1R | DRG neuron/CFA | DRG ↑ | Neuron | 70 |

| IGF-1R | CFA | DRG - | Neuron | 71 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | bone cancer pain. | tibia bone cavity ↑ | Neuron | 73 |

| IGF-1 | lumbar disc herniation (LDH) model | DRG ↑ | Neuron |

58

74 |

| IGF-1 | infraorbital nerve injury (IONI) induced neuropathic pain | TG ↑ infraorbital nerve ↑ |

Macrophage Satellite glial cell |

76 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | Spinal cord injury induced neuropathic pain | - | - | - |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | pain associated with endometriosis | peritoneal fluid (PF) ↑ | Macrophage (IBA1) | 77 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | TG neuron | TG | Neuron | 73 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | chronic constriction injury (CCI) | Spinal cord ↑ | Microglia (IGF-1) Astrocyte (IGF-1) Neuron (IGF-1) Neuron (IGF-1R) |

78 |

| IGF-1/ IGF-1R | plantar incision induced pain | DRG ↑ | Neuron (IGF-1R) Satellite glial cell (IGF-1R) |

34 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | Intraplantar recombinant (r) IGF-1 | DRG (IGF-1R) ↑ | TRPV1 neuron | 67 |

| IGF-2 | spared nerve injury (SNI) induced neuropathic pain | Spinal cord ↑ | Neuron CD11b microglia |

79

80 |

3.2.2. The IGF/IGF-1R pathway involved in relieving acute pain

However, Takemura et al found that IGF-1 expression increased in paw, but did not increase in DRG after plantar incision. Plantar injection of IGF-1 increased the expression of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) in ipsilateral DRG, which can relive the mechanical hyperalgesia. The application of IGF-1R inhibitor (250 µg/kg and 500 µg/kg) prevented the induction of GRK2 and the regression of hyperalgesia after plantar incision69 (Table 2). The reason why this study has different results from the above studies that Miura conducted may be closely related to the different observation time. This experiment mainly focuses on the state 7 days after the incision pain, while the above research focuses on the pain within 3 days after the incision.

Table 2.

The pain model, expression, localization of the IGF/IGF-1R relieving the pain.

| IGF/IGF-1R | Pain model | Expression | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF-1/ IGF-1R | plantar incision induced pain | Plantar tissue ↑ | DRG | 69 |

| IGF-1 | spinal nerve injury model | Spinal cord ↑ | CD11c+ microglia | 35 |

| IGF-1/IGF-1R | Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) | spinal cord↓ spinal cord neuron activity - |

IGF-1 (astrocyte) IGF-1R (Neuron) - |

82

83 |

| IGF-1 | Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) induced neuropathic pain | Serum ↓ spinal cord ↓ |

- astrocyte Neuron microglia (major) |

85

87 |

| IGF-1 | spinal cord compression injury (SCI) induced neuropathic pain | DRG - | - | 86 |

| IGF-1 | neuropathic pain following deafferentation injury | DRG - | - | 88 |

3.2.3. The IGF/IGF-1R pathway involved in aggravating chronic pain

There are also research findings reported that the IGF/IGF-1R signaling pathway can cause hyperalgesia in chronic pain (Table 1). IGF-1 increases T-type channel currents through the IGF-1R that is coupled with a G protein-dependent protein kinase C-α (PKC-α) pathway, thereby increasing the excitability and sensitivity of DRG neurons to induce pain70. Under complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) induced chronic inflammatory pain conditions, T-type Cav3.2 channel at least partially mediates the pain promotion through IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway in DRG71. Besides, IGF-1 activates IGF-1R to induce neuronal hyperexcitability in small trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons, decreasing A-type K+ currents (IA) to enhance the sensitivity of pain72.

Furthermore, IGF-1 in tibia bone marrow was increased in metastasized bone cancer pain model, while intraperitoneal injection IGF-1R inhibitor (PPP, 20 mg/kg/12 h) in vivo can reverse mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in rats with bone cancer pain73. Then the up-regulation of IGF-1 may be the key factor of painful radiculopathy induced by mechanical factors in a rat lumbar disc herniation (LDH) model74 58. IGF-1 knockdown leads to abnormal reduction of mechanical pain58. Subcutaneous injection of IGF-1 (2 mg/kg) induced a significant allodynia in treatment-induced painful neuropathy of diabetes (TIND)75. In addition, orofacial nerve injury (IONI) induced neuropathic pain can up-regulate the IGF-1, while subcutaneous injection of IGF-1 neutralizing antibody can recover the mechanical head withdrawal reflex thresholds (MHWTs) significantly76. Forster et al demonstrated that in a vitro model of endometriosis associated macrophages, disease modified macrophages showed increased expression of IGF-1, and confirmed the expression of damaged resident macrophages in mice. IGF-1R inhibition (linsitinib, 40 mg/kg) attenuates endometriosis induced hyperalgesia in mice77. Interestingly, abnormal IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling in spinal cord contributes to chronic constriction injury (CCI) induced neuropathic pain and IGF-1R antagonism (nvp-aew54, 15 μg/day) or IGF-1 neutralizing antibody (1 μg/day) can reduce pain behavior induced by CCI78. Similar to CCI, intrathecal administration of IGF-2 siRNA significantly inhibited spared nerve injury (SNI) induced neuropathic pain by inhibiting the expression of IGF-2 in the spinal cord79. Moreover, the treatment of pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) also alleviated neuropathic pain caused by SNI through downregulating the expression of IGF-2 in spinal dorsal horn80. Therefore, in multiple animal models of chronic pain, IGF/IGF-1R pathway can aggravate chronic pain.

Clinical data found that IGF-1 in peritoneal fluid (PF) significantly increased in patients with endometriosis, and its concentration was positively correlated with pain score77. Besides, in patients with breast cancer, increased IGF-1 concentration was reported new onset or worsening pain81. Specifically, the IGF-1: IGFBP-3 ratio increased in patients who experienced new pain episodes or pain exacerbations, while it decreased statistically significantly in patients who did not experience new pain or pain exacerbations81. Similar to the results of animal experiments, the high expression of IGF-1 in patients strongly associated with increased pain score. So, both animal and clinical experiments suggest that IGF/IGF-1R can aggravate chronic pain.

3.2.4. The IGF/IGF-1R pathway involved in relieving chronic pain

More studies have shown that IGF/IGF-1R signaling pathway is involved in the occurrence and development of chronic pain (Table 2). Kohno et al found that 21 days after peripheral nerve injury (PNI), the up-regulation of IGF-1 in CD11c+ microglia of the spinal dorsal horn can alleviate neuropathic pain, while knockout of IGF-1 in CD11c+microglia can make neuropathic pain lasts for at least 56 days in mice35. Pain thresholds had recovered to baseline on the 35th day after PNI, and intrathecal injection of IGF1-neutralizing antibody could cause pain recurrence35. In addition, in the rat neuropathic pain model of chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), the expression of IGF-1 protein in the spinal cord was significantly reduced. Intravenous or intraperitoneal injection of rIGF-1 (1 μg) alleviated pain like behavior induced by chemotherapy82. In painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) rat model, subcutaneous injection of IGF-1 (2.5mg/kg) can relieve neuropathic pain83. Nasal treatment with IGF-1 can relieve migraine-related pain in animal models84. Chu et al reported that the STZ treated mice developed hyperalgesia at the early stage, followed by hypoalgesia, and the systemic IGF-1 level was significantly reduced. Increasing circulating IGF-1 can significantly relieve neuropathic pain in diabetes85. Inhibition of IGF-1 (intrathecal injection of LV shIGF-1 lentivirus vector) can aggravate cord compression injury (SCI) induced neuropathic pain86. In addition, painful diabetic neuropathy significantly reduces the expression of IGF-1 in spinal cord. Intraperitoneal injection rIGF-1(1 μg/d) in mice alleviates pain-like behavior induced by diabetes87. Interestingly, electroacupuncture treatment can relieve neuropathic pain following nerve injury by activating the IGF-1 pathway88. Bagriyanik et al found that resveratrol (RVT) reduced CCI induced damage through IGF-1 immunoreactivity89.

Clinical experiments also show that serum IGF-1 level is related to pain. Low serum IGF-1 levels are associated with pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS)90-92. Koca et al reported that FMS patients showed lower IGF-1 serum levels, but with no related to disease severity93. However, another research found that women with FMS and low IGF-1 levels improved their overall symptoms and number of pain points after receiving daily growth hormone therapy for 9 months, indicating that increased IGF-1 level in serum can relieve FMS94. In a lasting 12-month study, the average number of pain points (pairs) decreased by 60% after human growth hormone treatment for FMS patients with low level IGF-190. Besides, a study recruited a total of 493 FMS patients with low IGF-1 to receive the growth hormone treatment. Twelve to eighteen months after stopping the treatment, the growth hormone treatment still had analgesic effect, showing its sustained action over time95. All of the above studies suggest that IGF/IGF-1R can relieve chronic pain. However, it has also been found in several reports to aggravate chronic pain. The reasons for the opposite results are mainly due to the different animal models, different observation time windows and different observation sites in each study. Therefore, more studies are needed to explore and find the pattern for the symptomatic management of pain.

4. Mechanisms of IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway related to pain

4.1. Relationship between IGF -1/IGF-1R pathway and neuronal excitability

DRG neurons that diameter less than 30 μM are mainly involved in nociceptive signal transduction96, 97. The incubation of IGF-1 (100 nM) enhanced the peak amplitude of T-type calcium channel current in small DRG neurons, while the amplitude was only partly recovered in 3 minutes after IGF-1 was washed away70. However, the current was eliminated when JB-1 (a selective IGF-1R antagonist, 1 μM) was used, indicating that IGF-1R is involved in IGF-1 mediating the influence on T- type calcium channel current in small DRG neurons. The author also found that JB-1 mainly affects the current of Cav3.2 in DRG neurons70. T-type Cav3.2 calcium channel belongs to low voltage activated Ca2+ channel and is an important contributor to nociceptive signal transmission in primary afferent pain pathway98, 99. Similar to this study, in another CFA induced chronic inflammatory pain mice model, T-type Cav3.2 channel can facilitate and amplify pain signals through the activation of IGF-1/ IGF-1R71. Lin et al also found that the expression of Cav3.2 and IGF-1R in lumbar DRG was up-regulated after sciatic neurotomy, indicating the interaction of T-type Cav3.2 channel and IGF-1 can contribute to pain hypersensitivity in primary sensory nerves100. Besides, there are two main types of outward voltage gated K+ channel (Kv) currents in nociceptive neurons to induced pain: IA and IDR101-103. Bath application of IGF-1 (0.1 μM) inhibited IA in small TG neurons. After the elution of IGF-1, the amplitude of IA partially recovered to the pretreatment level within 5 minutes. However, treating TG neurons with selective IGF-1R antagonist PQ-401 (10 μM) completely eliminated IGF-1 (0.1 μM) induced IA reduction72. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) current density increased in acutely isolated DRG neurons with MRMT-1 bone cancer pain in rats. Then the authors incubated DRG neurons with IGF-1 (30 or 100 ng/mL), which could increase the expression of total and membrane TRPV1 protein, indicating that IGF-1 can aggravate pain by increasing TRPV1 current73.

However, subcutaneous injections of IGF-1 (2.5 mg/kg) can relieve the pain behaviors induced by PDN, and reverse the hyperactivity of neurons in the spinal cord and ventrolateral PAG83. Therefore, IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway can regulate pain by regulating the excitability of nociceptors and spinal cord. The opposite effect of IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway in pain may be related to different pain models or different effect regions. The peripheral IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway may play a role in promoting pain, while the central (spinal cord) IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway may play a role in inhibiting pain.

4.2. Relationship between IGF /IGF-1R pathway and neuroinflammation as well as glial cells

4.2.1 IGF /IGF-1R pathway and neuroinflammation

P38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk), and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are the family of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)104, 105. These molecules transfer from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and activate many transcription factors, such as NF-kappaB (NF- κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), which can promote the release of various molecules, including p16, p21, IL-6 and interlukin-18 (IL-8). They can thus cause inflammation in pain related disease106, 107. Intraplantar injection of rIGF-1 (50 μg/kg) increase the expression of c-raf and p-ERK, while JB1 (6 μg/mouse) pretreatment significantly reduced p-ERK and c-raf levels in DRG67. Besides, PRF can inhibit ERK1/2 activity in microglia by down-regulating IGF-2 to relieve the neuropathic pain80. Antagonism of spinal IGF-1R (nvp-aew541, 15 μg) suppressed the overexpression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 that induced by up-regulation of mTOR in CCI neuropathic pain78.

Intrathecal or intraperitoneal injection of rIGF-1 (1 μg) inhibits neuropathic pain induced by oxaliplatin therapy, which can reduce the expression of IL-17A and TNF- α in spinal cord82. In addition, downregulation of miR-130a-3p increased the expression of IGF-1 and IGF-1R in spinal cord. When the expression of IGF-1 and IGF-1R were up-regulated, they can suppress the expression of NF- κB phosphorylation and IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in SCI rats86.

4.2.2 IGF /IGF-1R pathway and glial cell

It is well known that the neuroinflammatory response is almostly caused by exactly glial cells. Therefore, activation of glial cells is also closely associated with neuroinflammation. A study reported that IONI promoted macrophage infiltration into damaged ION and the corresponding TG. On the third day after IONI, the amount of IGF-1 released by macrophages in ION and TG increased significantly. In addition, subcutaneous injection of neutralization of IGF-1 (20 ng) partially inhibited the mechanical hypersensitivity induced by IONI76. In CCI mice, the number of astrocytes collocated with IGF-1 in the ipsilateral spinal dorsal horn was significantly more than that of the contralateral side. Intrathecal injection of IGF-1 neutralizing antibody (1 μg/day, 3 days) inhibits activation of spinal astrocytes. Besides, inhibition of IGF-1 expression also suppressed the expression of spinal cord neuroinflammation such as TNF-a, IL-B and IL-678. In endometriosis induced pain mice model, the mRNA expressions of Cox-2 and TNF-α that macrophages released in spinal cord increased and these levels decreased after depletion of macrophages with liposomal clodronate77.

The Science article found that PNI mice with exhausted spinal cord CD11c+microglia failed to recover spontaneously from this hypersensitivity reaction. Down-regulation of IGF-1 signal once again shows the pain hypersensitivity from the recovery. In mice with pain recovery, the depletion of CD11c+microglia or the interruption of IGF-1 signal led to the recurrence of pain hypersensitivity35. In PDN mice model, IGF-1 expression in spinal microglia decreased significantly. Intrathecal injection of rIGF-1 (1 μg/d, 3 days) prevents M1 microglia polarization (iNOS+Iba-1+microglia) and reduces the corresponding M1 neuroinflammation, such as iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α87. In summary, IGF/IGF-1R can widely affect the occurrence and development of pain by regulating glial cells and neuroinflammation. Therefore, the intervention of IGF/IGF-1R pathway may regulate pain by regulating neuroinflammation.

4.3. Relationship between IGF /IGF-1R pathway and other aspects

Bath application of IGF-1 (0.1 μM) reduced IA in small TG neurons. When selective IGF-1R antagonist PQ-401 (10 μM) was used to treat the TG neurons, it could completely eliminate IGF-1 induced IA reduction. While when TG neurons were pretreated with phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin (1 μM), IGF-1 had no impact on IA. Another PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM) had the similar results, indicating that PI3K contributes to IGF-1R mediated IA reduction72. PI3K, known as a conservative signal transduction enzyme family, is involved in regulating cell growth, cycle entry, migration and survival108, 109. Protein kinase B (PKB/AKT), was activated via PI3K pathway110, also plays an important role in the pain regulation of IGF/ IGF-1R pathway. Miura et al reported that after plantar incision, the expression of phosphorylated Akt in DRG neurons increased significantly and was inhibited by the single administration of picropodophyllin (an inhibition of IGF-1R, 50 μg) to the plantar skins. The increase of IGF-1 production in skin tissues sensitizes primary afferent neurons through IGF-1R/Akt pathway to promote pain hypersensitivity after tissue injury34.

Besides, dynamic regulation of GRK2 negatively regulates nociception in primary afferent neurons. Plantar injection of IGF-1 (1 μg) increased the expression of GRK2 in ipsilateral DRG. The application of IGF-1R inhibitor (picropodophyllin, 250 µg/kg) prevented the induction of GRK2 and the regression of hyperalgesia after plantar incision, indicating that the induction of GRK2 expression driven by tissue IGF-1 has an effective analgesic effect69. Hu et al reported that the expression levels of IGF-1, pPI3K and pAkt down-regulated in DRG, and overexpression of IGF-1 reduced the pain intensity by activating PI3K/Akt pathway in rat model of adjacent dorsal root ganglionectomies88. Furthermore, after PNI, AXL mRNA was expressed in CD11chigh SDH microglia, which is a member of the TAM (TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK) family of tyrosine kinase receptors involved in the engulfment of myelin debris. AXL participates in the appearance of CD11 chigh spinal dorsal horn microglia to induce the expression of IGF-1, promoting the relief of PNI induced neuropathic pain35. Therefore, IGF/IGF-1R regulates pain through a variety of ways. In addition to participating in the regulation of neuronal excitability and neuroinflammation, it also regulates pain in other ways, such as apoptosis, autophagy, etc.

5. Discussion and perspective

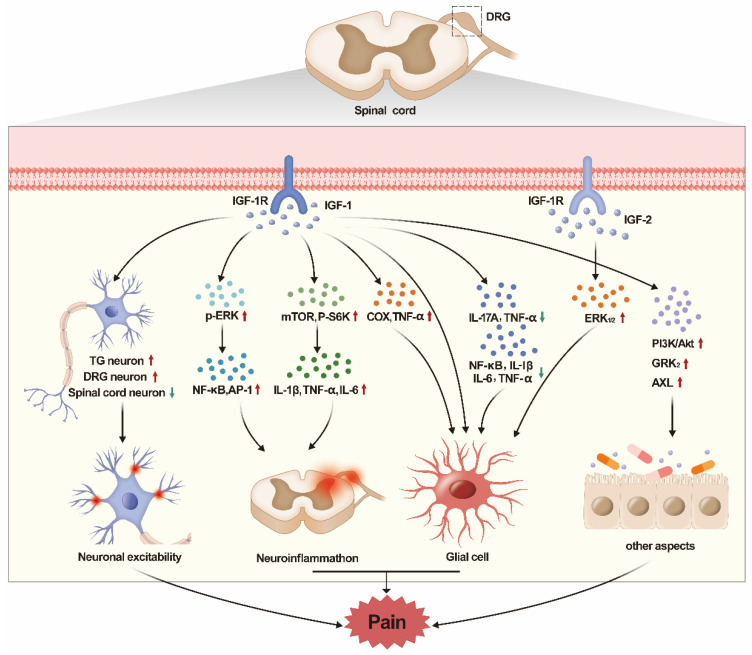

In this review, we summarized the role of IGF/IGF-1R pathway in various types of pain. It was found that IGF/IGF-1R played different roles in different types of pain. Besides, IGF/IGF-1R also played different roles in different regions. The peripheral IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway mainly plays a role in promoting pain, while the central (spinal cord) IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway mainly play a role in relieving pain. The mechanisms of IGF are different in different pain models. IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway increases excitability and pain sensitivity in peripheral neurons, but it can reverse the excitability of neurons at the spinal cord, thereby reducing pain sensitivity. Besides, another main mechanism of IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway is to affect pain by regulating glial cells and neuroinflammation. However, IGF-1/IGF-1R has different effects on inflammation in different pain models. Of course, the IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway can also regulate pain through autophagy, demyelination and PI3K/AKT pathway. At last, few studies reported the relationship between IGF-2 and pain (see Fig. 1 for summary).

Figure 1.

The graphic image of this review. The regulation of IGF/IGF-1R pathway in DRG and spinal cord has obvious effect on pain. The IGF/IGF-1R regulates pain by acting on neuronal excitability, neuroinflammation, glial cells, apoptosis, etc.

Currently, the main researches mainly focused on the relationship between IGF-1 and pain. Researches on IGF and pain mainly focus on peripheral (DRG, TG) and lower central (spinal cord) system. However, IGF-1R is expressed not only in DRG51 and spinal cord111, but also in brain such as hippocampus and cortex111-117. Chen et al indicated that rufinamide can improve cognitive function and increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the aged gerbil by increasing the IGF-1, IGF-1R and p-CREB expressions63. IGF-1R signals were damaged in Alzheimer's disease (AD) neurons in temporal cortex, which indicated that degenerated neurons in AD might be resistant to IGF-1R/IR signals118. In hippocampus, IGF-1 signaling axis can regulate traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced damage (cognitive as well as cellular)119. Therefore, IGF-1/IGF-1R also plays a regulatory role in various diseases in the brain. Pain, especially chronic pain, is closely related to the brain120-122. We speculate that the IGF-1/IGF-1R signal axis in the brain is also involved in pain regulation, which needs further research to confirm. Combined with the role of IGF/IGF-1R in DRG and spinal cord, IGF/IGF-1R in different regions of the brain may play different roles in regulating pain, which also needs further research in the future.

Besides, combined with existing research findings, it was found that the regulation of IGF/IGF-1R pathway on pain is closely related to the time of pain occurrence. In the acute phase of pain, IGF/IGF-1R pathway mainly plays a role in promoting pain. While with the extension of time, IGF/IGF-1R pathway may alleviate pain. It suggests that IGF/IGF-1R may play different roles in different stages of pain occurrence and development. This is also the research that needs to be continued in the future.

Last, although some studies have confirmed that IGF-2 also played a regulatory role in pain, there are few studies at present about the relationship between them. Uchimura et al reported that IGF-2 inhibited the expression of IL-1β induced cartilage matrix loss and promoted cartilage integrity in experimental osteoarthritis (OA)123. In OA cartilage, the IGF-1, IGF-2, IGF-1R and IRS1 in the degenerated area declined compared with the reserved area124. Multiple study also indicated the role of IGF-2 in OA125-127. Therefore, IGF-2 may also play an important role in pain, which is also the direction for the further researches.

6. Conclusion

Multiple studies have found that IGF/IGF-1R pathway plays an important role in the occurrence and development of pain. IGF/IGF-1R regulates pain by acting on neuronal excitability, neuroinflammation, glial cells, apoptosis, etc. In conclusion, although more deep researches are needed in the future, these studies indicate that IGF/IGF-1R signal pathway is a promising therapeutic target for pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2018YFC2001802 to X. Chen); National Natural Science Foundation (grant 82071251 to X. Chen); Hubei Province Key Research and Development Program (grant 2021BCA145 to X. Chen).

Author contributions

This work was primarily conceived by XC and LM. Manuscript was written by LM, WZ, SH, FX, YW, DD, TZ, and XC. The figure was produced by LM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors warrant that the article has not received prior publication and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AP-1

Activator protein-1

- CCI

Chronic constriction injury

- CFA

Complete Freund's adjuvant

- CIPN

Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglion

- Erk

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FMS

Fibromyalgia syndrome

- GH

Growth hormone

- GRK2

G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2

- IASP

International Association for the Study of Pain

- IGF

Insulin-like growth factor

- IGFBP-1-6

Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins-1-6

- IGF-1R

Insulin-like growth factor receptor type 1

- IL-18

Interlukin-18

- IONI

Orofacial nerve injury

- IR

Insulin receptor

- IRR

Insulin receptor related receptor

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- LDH

Lumbar disc herniation

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MHWTs

Mechanical head withdrawal reflex thresholds

- MPS

Myofascial pain syndrome

- NF- ΚB

NF-kappaB

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- PDN

Painful diabetic neuropathy

- PF

Peritoneal fluid

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PIND

Painful neuropathy of diabetes

- PKC-α

Protein kinase C-α

- PKB/AKT

Protein kinase B

- PNI

Peripheral nerve injury

- PPP

Picropodophyllin

- PRF

Pulsed radiofrequency

- rIGF-1

Recombinant IGF-1

- SCI

Spinal cord compression injury

- scRNA

Single cell RNA

- SGC

Satellite glial cell

- SNI

Spared nerve injury

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TG

Trigeminal ganglion

- TIND

Treatment-induced painful neuropathy of diabetes

- TRPV1

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- RVT

Resveratrol

References

- 1.Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S. et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161:1976–82. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlet H. Postoperative pain, analgesia, and recovery-bedfellows that cannot be ignored. Pain. 2018;159(Suppl 1):S11–s6. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS. Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet (London, England) 2019;393:1537–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niraj G, Rowbotham DJ. Persistent postoperative pain: where are we now? British journal of anaesthesia. 2011;107:25–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, Mullen EA, Leung JM. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006;102:1267–73. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000199156.59226.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L. et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018;67:1001–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boersma K, Södermark M, Hesser H, Flink IK, Gerdle B, Linton SJ. Efficacy of a transdiagnostic emotion-focused exposure treatment for chronic pain patients with comorbid anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019;160:1708–18. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaron RV, Fisher EA, de la Vega R, Lumley MA, Palermo TM. Alexithymia in individuals with chronic pain and its relation to pain intensity, physical interference, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2019;160:994–1006. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack TM, Walker VA, Morley SJ, Hanks GW, Finlay-Mills BM. Depression, anxiety and chronic pain. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:1235–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb05251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo RC, Wegener ST, Heins SE, Haythornthwaite JA, MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ. Longitudinal relationships between anxiety, depression, and pain: results from a two-year cohort study of lower extremity trauma patients. Pain. 2013;154:2860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steglitz J, Buscemi J, Ferguson MJ. The future of pain research, education, and treatment: a summary of the IOM report "Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research". Translational behavioral medicine. 2012;2:6–8. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0110-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haugk KL, Wilson HM, Swisshelm K, Quinn LS. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-related protein-1: an autocrine/paracrine factor that inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation but permits proliferation in response to IGF. Endocrinology. 2000;141:100–10. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu BS, Landeen LK, Aroonsakool N, Giles WR. An analysis of the effects of stretch on IGF-I secretion from rat ventricular fibroblasts. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;293:H677–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01413.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janowska J, Gargas J, Ziemka-Nalecz M, Zalewska T, Sypecka J. Oligodendrocyte Response to Pathophysiological Conditions Triggered by Episode of Perinatal Hypoxia-Ischemia: Role of IGF-1 Secretion by Glial Cells. Molecular neurobiology. 2020;57:4250–68. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahmkhatri VP, Prasanna C, Atreya HS. Insulin-like growth factor system in cancer: novel targeted therapies. BioMed research international. 2015;2015:538019. doi: 10.1155/2015/538019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasprzak A. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Signaling in Glucose Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Werner H, Bruchim I. IGF-1 and BRCA1 signalling pathways in familial cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:e537–44. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y, Wu C, Yang J, Zhao Y, Jia H, Xue M. et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1-induced enolase 2 deacetylation by HDAC3 promotes metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2020;5:53. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr A, Baxter RC. Noncoding RNA actions through IGFs and IGF binding proteins in cancer. Oncogene. 2022;41:3385–93. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong W, Zhang N, Cheng G, Zhang Q, He Y, Shen Y, Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch Extracts Prevent Bone Loss and Architectural Deterioration and Enhance Osteoblastic Bone Formation by Regulating the IGF-1/PI3K/mTOR Pathway in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Teppala S, Shankar A. Association between serum IGF-1 and diabetes among US adults. Diabetes care. 2010;33:2257–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings EA, Sochett EB, Dekker MG, Lawson ML, Daneman D. Contribution of growth hormone and IGF-I to early diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1341–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercader JM, Liao RG, Bell AD, Dymek Z, Estrada K, Tukiainen T. et al. A Loss-of-Function Splice Acceptor Variant in IGF2 Is Protective for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2017;66:2903–14. doi: 10.2337/db17-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsson SC, Michaëlsson K, Burgess S. IGF-1 and cardiometabolic diseases: a Mendelian randomisation study. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1775–82. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ezzat VA, Duncan ER, Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT. The role of IGF-I and its binding proteins in the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2008;10:198–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatenby VK, Kearney MT. The role of IGF-1 resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes-mellitus-related insulin resistance and vascular disease. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2010;14:1333–42. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.528930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekmekcioglu C. Nutrition and longevity - From mechanisms to uncertainties. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2020;60:3063–82. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1676698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higashi Y, Sukhanov S, Anwar A, Shai SY, Delafontaine P. Aging, atherosclerosis, and IGF-1. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2012;67:626–39. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Admasu TD, Chaithanya Batchu K, Barardo D, Ng LF, Lam VYM, Xiao L. et al. Drug Synergy Slows Aging and Improves Healthspan through IGF and SREBP Lipid Signaling. Developmental cell. 2018;47:67–79.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanwright PJ, Qiu C, Rath J, Zhou Y, von Guionneau N, Sarhane KA. et al. Sustained IGF-1 delivery ameliorates effects of chronic denervation and improves functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury and repair. Biomaterials. 2022;280:121244. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slavin BR, Sarhane KA, von Guionneau N, Hanwright PJ, Qiu C, Mao HQ. et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Peripheral Nerve Injury. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology. 2021;9:695850. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.695850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raimondo TM, Li H, Kwee BJ, Kinsley S, Budina E, Anderson EM. et al. Combined delivery of VEGF and IGF-1 promotes functional innervation in mice and improves muscle transplantation in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2019;216:119246. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao D, Tang T, Zhu J, Tang Y, Sun H, Li S. CXCL12 has therapeutic value in facial nerve injury and promotes Schwann cells autophagy and migration via PI3K-AKT-mTOR signal pathway. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019;124:460–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miura M, Sasaki M, Mizukoshi K, Shibasaki M, Izumi Y, Shimosato G. et al. Peripheral sensitization caused by insulin-like growth factor 1 contributes to pain hypersensitivity after tissue injury. Pain. 2011;152:888–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohno K, Shirasaka R, Yoshihara K, Mikuriya S, Tanaka K, Takanami K. et al. A spinal microglia population involved in remitting and relapsing neuropathic pain. Science (New York, NY) 2022;376:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.abf6805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler AA, Le Roith D. Control of growth by the somatropic axis: growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factors have related and independent roles. Annual review of physiology. 2001;63:141–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocrine reviews. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeRoith D, Baserga R, Helman L, Roberts CT Jr. Insulin-like growth factors and cancer. Annals of internal medicine. 1995;122:54–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-1-199501010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Bikle DD, Chang W. Autocrine and Paracrine Actions of IGF-I Signaling in Skeletal Development. Bone research. 2013;1:249–59. doi: 10.4248/BR201303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massagué J, Czech MP. The subunit structures of two distinct receptors for insulin-like growth factors I and II and their relationship to the insulin receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1982;257:5038–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown J, Jones EY, Forbes BE. Keeping IGF-II under control: lessons from the IGF-II-IGF2R crystal structure. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2009;34:612–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Megyesi K, Kahn CR, Roth J, Froesch ER, Humbel RE, Zapf J. et al. Insulin and non-suppressible insulin-like activity (NSILA-s): evidence for separate plasma membrane receptor sites. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1974;57:307–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(74)80391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhaumick B, Bala RM, Hollenberg MD. Somatomedin receptor of human placenta: solubilization, photolabeling, partial purification, and comparison with insulin receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:4279–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin JB, Shia MA, Pilch PF. Stimulation of tyrosine-specific phosphorylation in vitro by insulin-like growth factor I. Nature. 1983;305:438–40. doi: 10.1038/305438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Meyts P. Insulin/receptor binding: the last piece of the puzzle? What recent progress on the structure of the insulin/receptor complex tells us (or not) about negative cooperativity and activation. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2015;37:389–97. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeRoith D, Werner H, Beitner-Johnson D, Roberts CT Jr. Molecular and cellular aspects of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Endocrine reviews. 1995;16:143–63. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-2-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams TE, Epa VC, Garrett TP, Ward CW. Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2000;57:1050–93. doi: 10.1007/PL00000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasaki N, Rees-Jones RW, Zick Y, Nissley SP, Rechler MM. Characterization of insulin-like growth factor I-stimulated tyrosine kinase activity associated with the beta-subunit of type I insulin-like growth factor receptors of rat liver cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1985;260:9793–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Favelyukis S, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Miller WT. Structure and autoregulation of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor kinase. Nature structural biology. 2001;8:1058–63. doi: 10.1038/nsb721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Zhang P, Fu G, Li J, Liu H, Li Z. Alterations in tyrosine kinase receptor (Trk) expression induced by insulin-like growth factor-1 in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain research bulletin. 2013;90:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu H, Xue C, Yao M, Wang H, Zhang P, Qian T. et al. miR-129 controls axonal regeneration via regulating insulin-like growth factor-1 in peripheral nerve injury. Cell death & disease. 2018;9:720. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0760-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dai P, Wang ZJ, Sun WW, Pang JX, You C, Wang TH. Effects of electro-acupuncture on IGF-I expression in spared dorsal root ganglia and associated spinal dorsal horn in cats subjected to adjacent dorsal root ganglionectomies. Neurochemical research. 2009;34:1993–8. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawkes C, Kar S. Insulin-like growth factor-II/Mannose-6-phosphate receptor in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia of the adult rat. The European journal of neuroscience. 2002;15:33–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benarroch EE. Insulin-like growth factors in the brain and their potential clinical implications. Neurology. 2012;79:2148–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182752eef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang XW, Yuan LJ, Yang Y, Zhang M, Chen WF. IGF-1 inhibits MPTP/MPP(+)-induced autophagy on dopaminergic neurons through the IGF-1R/PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway and GPER. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2020;319:E734–e43. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00071.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kappeler L, De Magalhaes Filho C, Dupont J, Leneuve P, Cervera P, Périn L. et al. Brain IGF-1 receptors control mammalian growth and lifespan through a neuroendocrine mechanism. PLoS biology. 2008;6:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Craner MJ, Klein JP, Black JA, Waxman SG. Preferential expression of IGF-I in small DRG neurons and down-regulation following injury. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1649–52. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200209160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takayama B, Sekiguchi M, Yabuki S, Kikuchi S, Konno S. Localization and function of insulin-like growth factor 1 in dorsal root ganglia in a rat disc herniation model. Spine. 2011;36:E75–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d56208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, Abdo H, Lönnerberg P, Lou D. et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:145–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aghanoori MR, Agarwal P, Gauvin E, Nagalingam RS, Bonomo R, Yathindranath V. et al. CEBPβ regulation of endogenous IGF-1 in adult sensory neurons can be mobilized to overcome diabetes-induced deficits in bioenergetics and axonal outgrowth. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2022;79:193. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pretsch G, Sanadgol N, Smidak R, Lubec J, Korz V, Höger H. et al. Doublecortin and IGF-1R protein levels are reduced in spite of unchanged DNA methylation in the hippocampus of aged rats. Amino acids. 2020;52:543–53. doi: 10.1007/s00726-020-02834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sohrabi M, Floden AM, Manocha GD, Klug MG, Combs CK. IGF-1R Inhibitor Ameliorates Neuroinflammation in an Alzheimer's Disease Transgenic Mouse Model. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2020;14:200. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen BH, Ahn JH, Park JH, Song M, Kim H, Lee TK. et al. Rufinamide, an antiepileptic drug, improves cognition and increases neurogenesis in the aged gerbil hippocampal dentate gyrus via increasing expressions of IGF-1, IGF-1R and p-CREB. Chemico-biological interactions. 2018;286:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Basta-Kaim A, Szczesny E, Glombik K, Stachowicz K, Slusarczyk J, Nalepa I. et al. Prenatal stress affects insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) level and IGF-1 receptor phosphorylation in the brain of adult rats. European neuropsychopharmacology: the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24:1546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ogundele OM, Pardo J, Francis J, Goya RG, Lee CC. A Putative Mechanism of Age-Related Synaptic Dysfunction Based on the Impact of IGF-1 Receptor Signaling on Synaptic CaMKIIα Phosphorylation. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 2018;12:35. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nieto Guil AF, Oksdath M, Weiss LA, Grassi DJ, Sosa LJ, Nieto M. et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates dynamic changes in neuronal polarity during cerebral cortical migration. Scientific reports. 2017;7:7703. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang Z, Cao F, Zhang H, Tang J, Li H, Zhang Y. et al. Peripheral pain is enhanced by insulin-like growth factor 1 and its receptors in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes. 2019;11:309–15. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grosman-Rimon L, Vadasz B, Parkinson W, Clarke H, Katz JD, Kumbhare D. The Levels of Insulin-Like Growth Factor in Patients with Myofascial Pain Syndrome and in Healthy Controls. PM & R: the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2021;13:1104–10. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takemura H, Kushimoto K, Horii Y, Fujita D, Matsuda M, Sawa T. et al. IGF1-driven induction of GPCR kinase 2 in the primary afferent neuron promotes resolution of acute hyperalgesia. Brain research bulletin. 2021;177:305–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Qin W, Qian Z, Liu X, Wang H, Gong S. et al. Peripheral pain is enhanced by insulin-like growth factor 1 through a G protein-mediated stimulation of T-type calcium channels. Science signaling. 2014;7:ra94. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin SF, Yu XL, Wang B, Zhang YJ, Sun YG, Liu XJ. Colocalization of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and T type Cav3.2 channel in dorsal root ganglia in chronic inflammatory pain mouse model. Neuroreport. 2016;27:737–43. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H, Qin J, Gong S, Feng B, Zhang Y, Tao J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-mediated inhibition of A-type K(+) current induces sensory neuronal hyperexcitability through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathways, independently of Akt. Endocrinology. 2014;155:168–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Y, Cai J, Han Y, Xiao X, Meng XL, Su L. et al. Enhanced function of TRPV1 via up-regulation by insulin-like growth factor-1 in a rat model of bone cancer pain. European journal of pain (London, England) 2014;18:774–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takayama B, Sekiguchi M, Yabuki S, Fujita I, Shimada H, Kikuchi S. Gene expression changes in dorsal root ganglion of rat experimental lumber disc herniation models. Spine. 2008;33:1829–35. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181801d9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nicodemus JM, Enriquez C, Marquez A, Anaya CJ, Jolivalt CG. Murine model and mechanisms of treatment-induced painful diabetic neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2017;354:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sugawara S, Shinoda M, Hayashi Y, Saito H, Asano S, Kubo A, Increase in IGF-1 Expression in the Injured Infraorbital Nerve and Possible Implications for Orofacial Neuropathic Pain. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Forster R, Sarginson A, Velichkova A, Hogg C, Dorning A, Horne AW. et al. Macrophage-derived insulin-like growth factor-1 is a key neurotrophic and nerve-sensitizing factor in pain associated with endometriosis. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2019;33:11210–22. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900797R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen X, Le Y, He WY, He J, Wang YH, Zhang L. et al. Abnormal Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Signaling Regulates Neuropathic Pain by Mediating the Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin-Related Autophagy and Neuroinflammation in Mice. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2021;12:2917–28. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chan WH, Huang NC, Lin YW, Lin FY, Tsai CS, Yeh CC. Intrathecal IGF2 siRNA injection provides long-lasting anti-allodynic effect in a spared nerve injury rat model of neuropathic pain. PloS one. 2021;16:e0260887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yeh CC, Sun HL, Huang CJ, Wong CS, Cherng CH, Huh BK. et al. Long-Term Anti-Allodynic Effect of Immediate Pulsed Radiofrequency Modulation through Down-Regulation of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 in a Neuropathic Pain Model. International journal of molecular sciences. 2015;16:27156–70. doi: 10.3390/ijms161126013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gallicchio L, MacDonald R, Helzlsouer KJ. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and musculoskeletal pain among breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitor therapy and women without a history of cancer. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2013;139:837–43. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1391-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Le Y, Chen X, Wang L, He WY, He J, Xiong QM. et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is promoted by enhanced spinal insulin-like growth factor-1 levels via astrocyte-dependent mechanisms. Brain research bulletin. 2021;175:205–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morgado C, Silva L, Pereira-Terra P, Tavares I. Changes in serotoninergic and noradrenergic descending pain pathways during painful diabetic neuropathy: the preventive action of IGF1. Neurobiology of disease. 2011;43:275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Won L, Kraig RP. Insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibits nitroglycerin-induced trigeminal activation of oxidative stress, calcitonin gene-related peptide and c-Fos expression. Neuroscience letters. 2021;751:135809. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chu Q, Moreland R, Yew NS, Foley J, Ziegler R, Scheule RK. Systemic Insulin-like growth factor-1 reverses hypoalgesia and improves mobility in a mouse model of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2008;16:1400–8. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yao L, Guo Y, Wang L, Li G, Qian X, Zhang J. et al. Knockdown of miR-130a-3p alleviates spinal cord injury induced neuropathic pain by activating IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2021;351:577458. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen X, Le Y, Tang SQ, He WY, He J, Wang YH. et al. Painful Diabetic Neuropathy Is Associated with Compromised Microglial IGF-1 Signaling Which Can Be Rescued by Green Tea Polyphenol EGCG in Mice. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2022;2022:6773662. doi: 10.1155/2022/6773662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hu T, Lu MN, Chen B, Tong J, Mao R, Li SS. et al. Electro-acupuncture-induced neuroprotection is associated with activation of the IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway following adjacent dorsal root ganglionectomies in rats. International journal of molecular medicine. 2019;43:807–20. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bagriyanik HA, Ersoy N, Cetinkaya C, Ikizoglu E, Kutri D, Ozcana T. et al. The effects of resveratrol on chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve in rats. Neuroscience letters. 2014;561:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cuatrecasas G, Riudavets C, Güell MA, Nadal A. Growth hormone as concomitant treatment in severe fibromyalgia associated with low IGF-1 serum levels. A pilot study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007;8:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leal-Cerro A, Povedano J, Astorga R, Gonzalez M, Silva H, Garcia-Pesquera F. et al. The growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone-GH-insulin-like growth factor-1 axis in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1999;84:3378–81. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.9.5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bennett RM, Cook DM, Clark SR, Burckhardt CS, Campbell SM. Hypothalamic-pituitary-insulin-like growth factor-I axis dysfunction in patients with fibromyalgia. The Journal of rheumatology. 1997;24:1384–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koca TT, Berk E, Seyithanoğlu M, Koçyiğit BF, Demirel A. Relationship of leptin, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor levels with body mass index and disease severity in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Acta neurologica Belgica. 2020;120:595–9. doi: 10.1007/s13760-018-01063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bennett RM, Clark SC, Walczyk J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of growth hormone in the treatment of fibromyalgia. The American journal of medicine. 1998;104:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cuatrecasas G, Alegre C, Fernandez-Solà J, Gonzalez MJ, Garcia-Fructuoso F, Poca-Dias V. et al. Growth hormone treatment for sustained pain reduction and improvement in quality of life in severe fibromyalgia. Pain. 2012;153:1382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. The Journal of physiology. 1992;445:639–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM. The endogenous redox agent L-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:8766–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.García-Caballero A, Gadotti VM, Stemkowski P, Weiss N, Souza IA, Hodgkinson V. et al. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 modulates neuropathic and inflammatory pain by enhancing Cav3.2 channel activity. Neuron. 2014;83:1144–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bourinet E, Alloui A, Monteil A, Barrère C, Couette B, Poirot O. et al. Silencing of the Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel gene in sensory neurons demonstrates its major role in nociception. The EMBO journal. 2005;24:315–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin SF, Yu XL, Liu XY, Wang B, Li CH, Sun YG. et al. Expression patterns of T-type Cav3.2 channel and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in dorsal root ganglion neurons of mice after sciatic nerve axotomy. Neuroreport. 2016;27:1174–81. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Y, Wang X, Qi R, Lu Y, Tao Y, Jiang D. et al. Interleukin 33-mediated inhibition of A-type K(+) channels induces sensory neuronal hyperexcitability and nociceptive behaviors in mice. Theranostics. 2022;12:2232–47. doi: 10.7150/thno.69320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee MC, Nahorski MS, Hockley JRF, Lu VB, Ison G, Pattison LA. et al. Human Labor Pain Is Influenced by the Voltage-Gated Potassium Channel K(V)6.4 Subunit. Cell reports. 2020;32:107941. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang J, Rong L, Shao J, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Zhao S. et al. Epigenetic restoration of voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.2 alleviates nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Journal of neurochemistry. 2021;156:367–78. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fang JY, Richardson BC. The MAPK signalling pathways and colorectal cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2005;6:322–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Humo M, Ayazgök B, Becker LJ, Waltisperger E, Rantamäki T, Yalcin I. Ketamine induces rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects in chronic pain induced depression: Role of MAPK signaling pathway. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2020;100:109898. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Arthur JS, Ley SC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:679–92. doi: 10.1038/nri3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin ML, Lin WT, Huang RY, Chen TC, Huang SH, Chang CH. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency inhibited activation of spinal mitogen-activated protein kinases and ameliorated early neuropathic pain in rats. European journal of pain (London, England) 2014;18:659–70. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science (New York, NY) 2002;296:1655–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shi J, Yu J, Zhang Y, Wu L, Dong S, Wu L. et al. PI3K/Akt pathway-mediated HO-1 induction regulates mitochondrial quality control and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2019;99:1795–809. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hu H, Juvekar A, Lyssiotis CA, Lien EC, Albeck JG, Oh D. et al. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Regulates Glycolysis through Mobilization of Aldolase from the Actin Cytoskeleton. Cell. 2016;164:433–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Biondi O, Branchu J, Ben Salah A, Houdebine L, Bertin L, Chali F. et al. IGF-1R Reduction Triggers Neuroprotective Signaling Pathways in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Mice. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:12063–79. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0608-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Freude S, Hettich MM, Schumann C, Stöhr O, Koch L, Köhler C. et al. Neuronal IGF-1 resistance reduces Abeta accumulation and protects against premature death in a model of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:3315–24. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Omote Y, Deguchi K, Tian F, Kawai H, Kurata T, Yamashita T. et al. Clinical and pathological improvement in stroke-prone spontaneous hypertensive rats related to the pleiotropic effect of cilostazol. Stroke. 2012;43:1639–46. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Le Grevès M, Le Grevès P, Nyberg F. Age-related effects of IGF-1 on the NMDA-, GH- and IGF-1-receptor mRNA transcripts in the rat hippocampus. Brain research bulletin. 2005;65:369–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gazit N, Vertkin I, Shapira I, Helm M, Slomowitz E, Sheiba M. et al. IGF-1 Receptor Differentially Regulates Spontaneous and Evoked Transmission via Mitochondria at Hippocampal Synapses. Neuron. 2016;89:583–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hascup ER, Wang F, Kopchick JJ, Bartke A. Inflammatory and Glutamatergic Homeostasis Are Involved in Successful Aging. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2016;71:281–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jiang G, Wang W, Cao Q, Gu J, Mi X, Wang K. et al. Insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) enhances hippocampal excitatory and seizure activity through IGF-1 receptor-mediated mechanisms in the epileptic brain. Clinical science (London, England: 1979) 2015;129:1047–60. doi: 10.1042/CS20150312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, O'Connor R, Ravid R, O'Neill C. Defects in IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer's disease indicate possible resistance to IGF-1 and insulin signalling. Neurobiology of aging. 2010;31:224–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rubovitch V, Edut S, Sarfstein R, Werner H, Pick CG. The intricate involvement of the Insulin-like growth factor receptor signaling in mild traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurobiology of disease. 2010;38:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu X, Xie Z, Li S, He J, Cao S, Xiao Z. PRG-1 relieves pain and depressive-like behaviors in rats of bone cancer pain by regulation of dendritic spine in hippocampus. International journal of biological sciences. 2021;17:4005–20. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.59032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Del Rey A, Yau HJ, Randolf A, Centeno MV, Wildmann J, Martina M. et al. Chronic neuropathic pain-like behavior correlates with IL-1β expression and disrupts cytokine interactions in the hippocampus. Pain. 2011;152:2827–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ma L, Yue L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Han B, Cui S. et al. Spontaneous Pain Disrupts Ventral Hippocampal CA1-Infralimbic Cortex Connectivity and Modulates Pain Progression in Rats with Peripheral Inflammation. Cell reports. 2019;29:1579–93.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Uchimura T, Foote AT, Smith EL, Matzkin EG, Zeng L. Insulin-Like Growth Factor II (IGF-II) Inhibits IL-1β-Induced Cartilage Matrix Loss and Promotes Cartilage Integrity in Experimental Osteoarthritis. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2015;116:2858–69. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tanaka N, Tsuno H, Ohashi S, Iwasawa M, Furukawa H, Kato T. et al. The attenuation of insulin-like growth factor signaling may be responsible for relative reduction in matrix synthesis in degenerated areas of osteoarthritic cartilage. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2021;22:231. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04096-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Guan PP, Ding WY, Wang P. The roles of prostaglandin F(2) in regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-12 via an insulin growth factor-2-dependent mechanism in sheared chondrocytes. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2018;3:27. doi: 10.1038/s41392-018-0029-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fernihough JK, Innes JF, Billingham ME, Holly JM. Changes in the local regulation of insulin-like growth factors I and II and insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in osteoarthritis of the canine stifle joint secondary to cruciate ligament rupture. Veterinary surgery: VS. 2003;32:313–23. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2003.50037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Qi Y, Ma N, Yan F, Yu Z, Wu G, Qiao Y. et al. The expression of intronic miRNAs, miR-483 and miR-483*, and their host gene, Igf2, in murine osteoarthritis cartilage. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2013;61:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]