Abstract

Maintaining the correct number of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) is critical for proper oxygenation of tissues throughout the body. Therefore, RBC homeostasis is a tightly controlled balance between RBC production and RBC clearance, through the processes of erythropoiesis and macrophage hemophagocytosis, respectively. However, during the inflammation associated with infectious, autoimmune, or inflammatory diseases this homeostatic process is often dysregulated, leading to acute or chronic anemia. In each disease setting, multiple mechanisms typically contribute to the development of inflammatory anemia, impinging on both sides of the RBC production and RBC clearance equation. These mechanisms include both direct and indirect effects of inflammatory cytokines and innate sensing. Here, we focus on common innate immune mechanisms that contribute to inflammatory anemias using examples from several diseases, including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, severe malarial anemia during Plasmodium infection, and systemic lupus erythematosus, among others.

Keywords: anemia, inflammation, hemophagocyte, malaria, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, sickle cell anemia

OVERVIEW OF RED BLOOD CELL HOMEOSTASIS

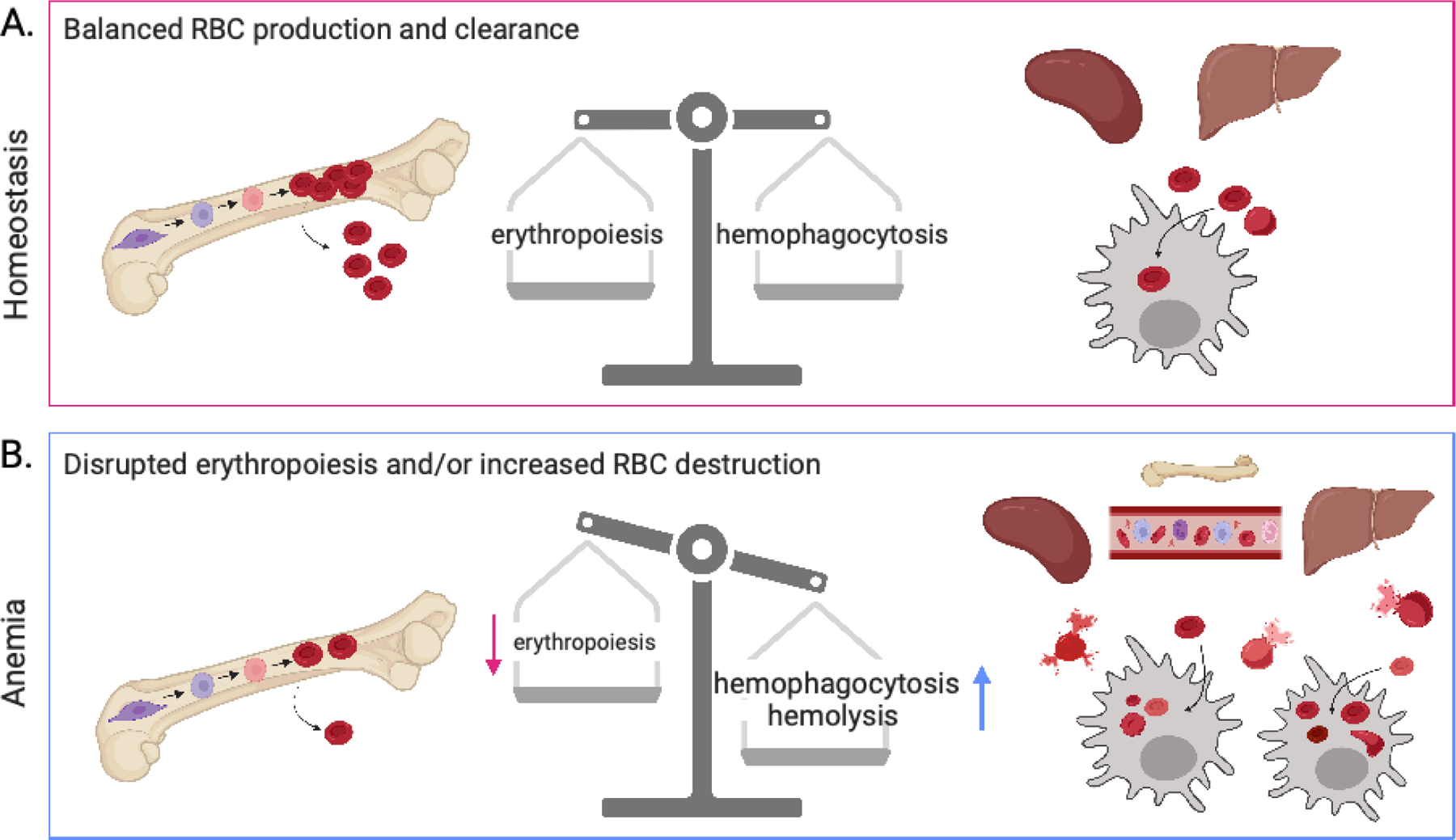

The number of circulating red blood cells (RBCs) is determined by the relative number of RBCs generated and RBCs destroyed (Figure 1). In the steady state, RBC generation occurs in the bone marrow through the process of erythropoiesis. Homeostatic RBC destruction occurs principally through the phagocytosis of damaged or senescent RBCs by splenic red pulp macrophages (RPMs) and liver Kupffer cells. This process is called hemophagocytosis or erythrophagocytosis. This cycle of production and clearance allows for a steady-state RBC life span of ~120 days in humans and ~60 days in mice, with close to 1% of RBCs turning over each day. Anemia, a condition defined by insufficient healthy RBCs, can be caused by several factors, including nutritional iron deficiency and inflammation (1–3). In this review, we focus on anemia that occurs during inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious diseases due to direct action of the immune response, with an emphasis on innate immune mechanisms including innate sensing and inflammatory cytokines.

Figure 1.

RBC homeostasis and anemia. The proper number of circulating, healthy red blood cells (RBCs) is sustained by a balance of RBC production and clearance. A disruption in either or both processes can lead to anemia. (a) At homeostasis, new RBCs are made in the bone marrow through erythropoiesis and subsequently released into circulation. Simultaneously, old and/or damaged RBCs are cleared from circulation through hemophagocytosis by resident phagocytes in the spleen and liver. (b) Anemia results when one or both sides of this RBC balance is disrupted. Suppressed or aberrant erythropoiesis leads to fewer new, healthy RBCs in circulation. Additionally, RBC destruction can result from infection- or immune-driven hemolysis as well as increased hemophagocytosis by phagocytes in the bone marrow, blood, spleen, and liver. Many immune mechanisms that contribute to anemia have been described and are discussed in this review; including inflammatory cytokines and interferons, autoantibodies to erythropoietin and its receptor, induction of monocyte-derived hemophagocytes, and regulation of positive and negative phagocytic receptors and ligands, among others. Figure adapted from images created with BioRender.com.

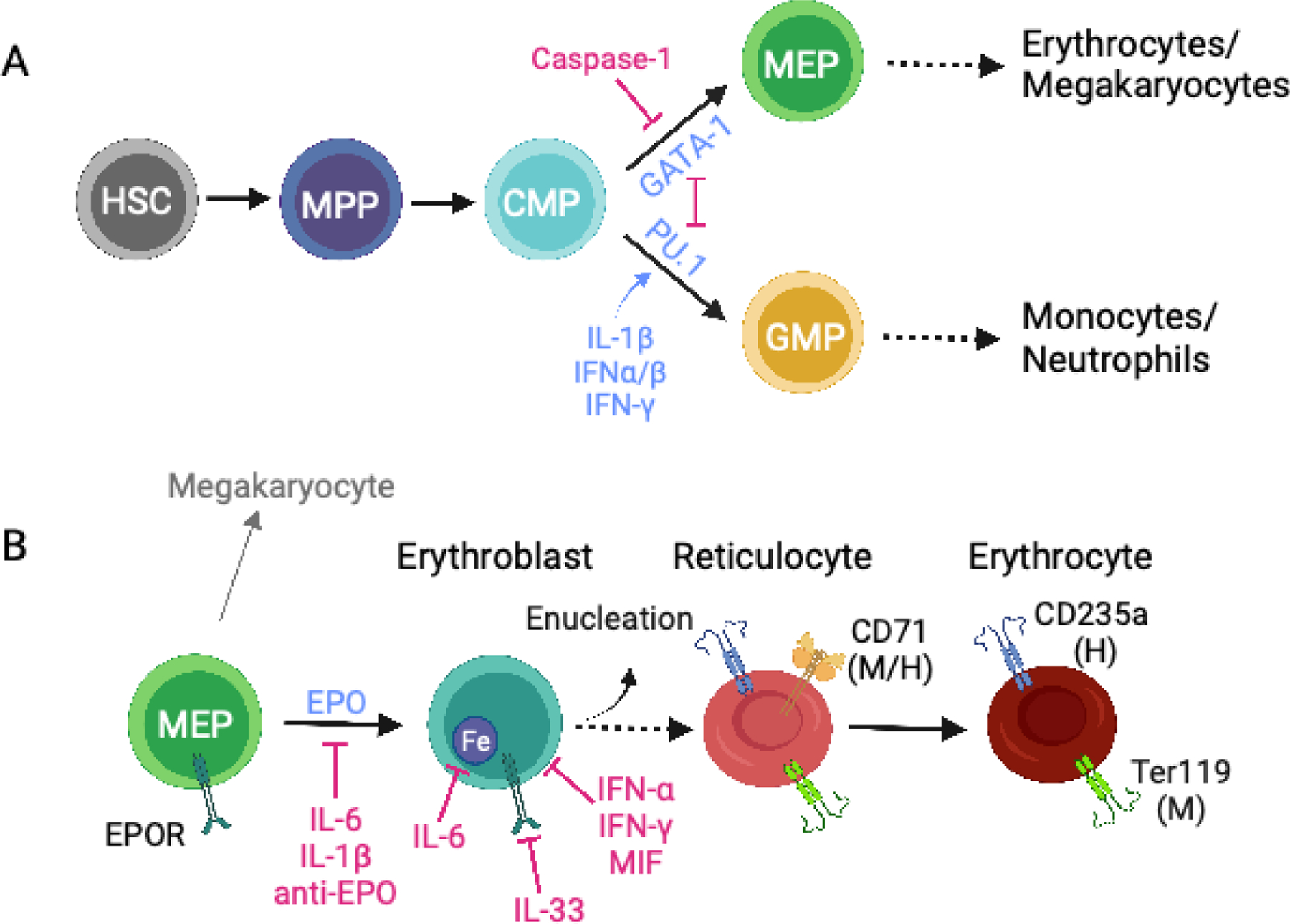

During homeostasis, RBC generation in the bone marrow is controlled by the key erythropoietic cytokine erythropoietin (EPO) binding to the EPO receptor (EPOR) on erythroid progenitors (Figure 2). There is an intimate connection between erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis because all myeloid cells that differentiate in the bone marrow share a common progenitor with erythrocytes. These common myeloid progenitors differentiate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and can proceed either down the megakaryocyte-erythrocyte differentiation pathway via megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs), which produce both megakaryocytes and erythrocytes, or down the myeloid differentiation pathway through granulocyte-macrophage progenitors, which generate monocytes, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (4–6). Though this model has been well accepted, newer findings suggest that megakaryocytes can also differentiate from an earlier multipotent progenitor rather than a shared MEP (7). Several key steps in erythroid development downstream of MEPs involve proliferation, differentiation, and formation of erythroblasts. Erythroblasts sequentially increase their hemoglobin production and condense and extrude their nuclei to become immature erythrocytes or reticulocytes, and subsequently they remodel their plasma membrane before becoming mature RBCs (8) (Figure 2). Macrophages are key cells in erythroblastic islands in the bone marrow, where they bind to developing erythrocytes, providing iron and other regulators of differentiation, and phagocytose and degrade extruded nuclei.

Figure 2.

Erythropoiesis during inflammatory anemia. (a) Development of megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) in the bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) differentiate into multipotent progenitors (MPPs) and, subsequently, into common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) that make a lineage choice between generating myeloid cells via GMPs or erythrocytes and megakaryocytes via megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs). Cross antagonism between the lineage-specifying transcription factors GATA-1 (erythroid lineage) and PU.1 (myeloid lineage) contributes to the relative production of RBCs and myeloid cells. During inflammation, several cytokines, including IFN-α/β, IFN-γ and IL-1β, increase PU.1 expression in CMPs, whereas activation of caspase-1 can cause GATA-1 cleavage, reducing GATA-1-dependent erythropoiesis; both of these activities promote myelopoiesis over erythropoiesis. (b) Interaction between the kidney-derived hormone erythropoietin (EPO) and the EPO receptor (EPOR) on MEPs results in erythroblast differentiation. During terminal erythroblast differentiation erythroblasts acquire iron for hemoglobin synthesis and nuclear condensation occurs. Erythroblasts enucleate and become reticulocytes (immature RBCs), which then exit the bone marrow and differentiate into erythrocytes (mature RBCs) in circulation. During inflammatory anemia, erythropoiesis can be inhibited through the action of many cytokines, including IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-33, and MIF, as well as anti-EPO or anti-EPOR autoantibodies. CD71 is expressed on mouse and human reticulocytes. Ter119 is expressed on mouse reticulocytes and erythrocytes; CD235a is expressed on human reticulocytes and erythrocytes. Figure adapted from images created with BioRender.com.

As RBCs age, their physical and molecular properties change in ways that promote their clearance via phagocytosis by specialized macrophages, principally in the spleen; however, liver macrophages can also contribute to this process (reviewed recently in 9). Some of the documented RBC changes with RBC aging include increased rigidity, altered shape and size, and modified distribution of cell surface proteins. As RBCs filter through the venous sinuses of the splenic red pulp, these altered properties cause them to become sequestered in the splenic cords, where they are phagocytosed by RPMs rather than reentering the circulation. Several signals that cause retention of aged RBCs in the splenic cords have been identified, including increased RBC interactions with the extracellular matrix. Signals inducing recognition and phagocytosis of aged RBCs by splenic RPMs are less well defined. CD47 on RBCs provides a well-recognized signal that inhibits phagocytosis through its interaction with SIRPα expressed on macrophages. The ability to overcome this negative signal is key to hemophagocytosis (10). However, whether this is due to reduced or altered CD47 membrane distribution or conformation on aged RBCs, or a different mechanism, is not clear (11, 12). Several positive signals for recognition of aged RBCs by macrophages have been implicated in phagocytosis, including opsonization with antibodies that recognize altered cell surface proteins on aged RBCs, opsonization with complement C3b, cell surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS), or CD47 itself (9). However, the relative contribution of these signals and their respective phagocytic receptors, in addition to other potential signals, is not well established in vivo.

ANEMIA DURING INFLAMMATORY, INFECTIOUS, AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES

During many inflammatory and immune responses, RBC production and/or clearance can be dysregulated, leading to anemia. Because circulating RBCs have a long life span of ~60–120 days, acute anemia principally results from increases in RBC destruction and/or clearance, whereas chronic anemia can be caused by decreases in RBC production, increases in RBC destruction/clearance, or a combination of these processes. However, acute anemia initially caused by increased RBC clearance may be reinforced or maintained by decreased RBC production, particularly as the homeostatic response to anemia is to increase erythropoiesis through increased EPO availability. Therefore, when examining how infection and inflammation lead to anemia, whether acute or chronic, it is important to consider both sides of this equation.

The terms “anemia of inflammation” and “anemia of chronic disease” are often used to describe anemia seen during infections or chronic inflammatory diseases. In this review, we discuss several infections and inflammatory diseases that are associated with either acute or chronic anemia, focusing on innate immune mechanisms that mediate either reduced RBC production or increased RBC clearance. These include infections by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV); bacteria such as Salmonella enterica; and parasites such as Plasmodium parasites, the causative agents of malaria, and Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of African sleeping sickness. For inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, we focus on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). We also consider the unique case of sickle cell anemia (SCA), which, while not typically considered inflammatory in nature, has some interesting similarities in the mechanisms of anemia with inflammatory diseases. While the infections and diseases discussed here do not account for all inflammation-associated anemias, many of the mechanisms we discuss are common to numerous other infections, inflammatory disorders, and autoimmune diseases. Below, we give brief introductions to the diseases on which we focus in this review and then discuss common and unique mechanisms amongst these diseases.

DISEASES OF PARTICULAR INTEREST

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Macrophage Activation Syndrome

HLH is a potentially fatal inflammatory syndrome characterized by high levels of inflammatory cytokines and cytopenias, including anemia, associated with the presence of hemophagocytes in bone marrow biopsies. Primary or familial HLH is due to loss-of-function mutations in the perforin-granzyme cytolytic pathway, whereas secondary HLH develops due to dysregulated immune responses to a range of triggers, including infections, hematologic malignancies, and autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (13–15). When presenting secondary to an autoimmune or inflammatory disorder, secondary HLH is often referred to as MAS. Although MAS has no clear hereditary link, heterozygous mutations in cytolytic genes and/or cytolytic pathway abnormalities have been identified in some patients with this disease (13, 16–18). Viral triggers are common in both primary and secondary HLH, where the current working model proposes that ineffective cytotoxicity results in the inability to clear infection, leading to chronic immune activation (19, 20). Several mouse models of primary and secondary HLH have been developed, which have in common chronic activation of viral sensing pathways. Infection of perforin-deficient mice with lymphochoriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a common model of primary HLH (21). Secondary HLH or MAS has been modeled using chronic activation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family of innate pattern recognition receptors, particularly the subset of virus-sensing TLRs. These models include repeated injections of TLR9 agonist CpG DNA, transgenic overexpression of the single-stranded RNA sensor TLR7, and injection of the TLR3 agonist polyI:C followed by injection of the TLR4 agonist LPS (22–25). Interestingly, gain-of-function mutations in NLCR4, encoding a key component in the NLCR4 inflammasome, have been found in some patients with secondary HLH (26, 27). This can be modeled in mice as well, suggesting that not only TLR activation but also inflammasome activation can drive HLH and anemia.

Plasmodium Infection and Severe Malarial Anemia

Infection with Plasmodium parasites, the causative agents of malaria, can result in mild to severe anemia (28). Severe malarial anemia (SMA) mostly affects young children and pregnant women. The life cycle of Plasmodium parasites includes infection of Anopheles mosquitos and mammalian hosts. In mammalian hosts, the parasite first infects hepatocytes followed by RBCs. Whereas the liver-stage infection is clinically silent, the blood-stage infection is responsible for malaria symptoms. Infection with Plasmodium species is distinct from many other infections in that RBCs are directly infected by these parasites during the symptomatic blood stage of infection. Within RBCs, Plasmodium parasites use hemoglobin as a source of amino acids, and as a result the parasites release free heme. Free heme is toxic due to its oxidative properties, and intraerythrocytic parasites convert free heme into the crystalline polymer hemozoin to temper the toxicity. Hemozoin itself and hemozoin complexed with other Plasmodium products act as innate immune activators inducing inflammatory cytokines from myeloid cells (28). Blood-stage infection of mice with rodent-specific Plasmodium species, such as P. yoelii or P. chabaudi, are used to model SMA and investigate the mechanisms contributing to disease.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE is an autoimmune disease that mainly affects young women and is characterized by circulating antinuclear antibodies that recognize nucleic acids and nucleic acid–binding proteins (29). Individuals with SLE can have a diverse set of symptoms, including skin rashes and arthritis and kidney disease. Almost any tissue can be the target of autoimmune attack in this disease. Anemia is also common in people with SLE, where it can vary from mild to severe (30). Many etiologies contribute to anemia in SLE, including autoimmune hemolytic anemia, caused by anti-RBC antibodies, anemia of chronic inflammation, and kidney disease. In SLE, dysregulated innate immune responses and impaired B cell tolerance lead to a feed-forward loop of innate immune activation, type I interferon secretion, and autoantibody production, all of which can promote anemia (31, 32).

Sickle Cell Anemia

SCA is due to a single point mutation in the HBB gene, encoding hemoglobin subunit β. The HBB mutation results in the production of a variant hemoglobin termed hemoglobin S (HbS) that can lead to sickling of RBCs (33). In SCA, deoxygenation of hemoglobin results in HbS polymerization causing increased RBC rigidity, altered RBC shape, and RBC sickling. Sickle RBCs exhibit abnormal microcirculatory flow and stick to the vasculature endothelium, driving vaso-occlusive disease in which tissues can repeatedly cycle through oxygen starvation and reperfusion. As a result, Sickle Cell Disease patients experience chronic pain, organ damage, and chronic inflammation and can develop anemia. The anemia results from loss of RBCs, whether it be due to premature apoptosis, hemolysis, or phagocytosis. The distribution of SCA closely overlaps with regions of high malaria burden. Interestingly, individuals carrying one copy of the allele encoding HbS (that is, sickle cell trait) have protection against severe malaria (33–35). This reduced severity of malaria is attributed to the fact that parasitemia is decreased in individuals carrying sickle cell trait, but the exact underlying mechanisms are unknown and could be due to reduced infectivity of sickle RBCs or increased hemophagocytosis of infected, sickle RBCs (36–38).

SUPPRESSION OF ERYTHROPOIESIS

Effects of Inflammatory Cytokines

During infection and inflammation, a wide variety of mechanisms can lead to reductions in erythropoiesis (Figure 2). Many of these mechanisms are due to the effects of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ, and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). All of these inflammatory cytokines are produced early during infection in response to innate sensing, although in some cases direct infection of mature RBCs or their progenitors leads to either RBC lysis or reduced erythropoiesis, contributing to anemia.

IL-6

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by many cells, including monocytes and macrophages, during many infections and sterile inflammatory disorders. IL-6 is a key mediator of RBC production because it regulates the hormone hepcidin, an acute-phase protein produced principally in the liver by hepatocytes. Hepcidin reduces iron export into the plasma by occluding or degrading the iron transporter ferroportin on hepatocytes, duodenal enterocytes, and hepatic and splenic iron-recycling macrophages (3, 39). Increased levels of hepcidin result in iron accumulation in enterocytes and recycling macrophages, which leads to low serum iron, restricting iron availability for erythropoiesis and contributing to anemia. IL-6 signals through JAK2-STAT3 to drive increased transcription of hepcidin in hepatocytes (40). IL-6 has also been documented to inhibit EPO expression in the kidney. Thus IL-6 has several mechanisms by which it can reduce erythropoiesis and contribute to anemia (41).

IL-6 and hepcidin play important roles in driving anemia in multiple infectious diseases. The association between IL-6, hepcidin, and the development of anemia during inflammation associated with bacterial infections has been recently reviewed (2, 39). Iron sequestration in tissues is one immune mechanism to inhibit growth of bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) (42). More recently, increased IL-6 and hepcidin have been linked to a heightened risk for anemia in patients with viral infections. Individuals with HIV infection who are on combination antiretroviral therapy are at increased risk of anemia if they have high serum IL-6 and hepcidin (43). In patients with severe COVID-19, increased serum hepcidin, anemia, and increased circulating IL-6 have been linked to increased mortality risk (44–46). Interestingly, patients who had critical COVID-19 had higher expression of HAMP, the gene encoding hepcidin, in their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) compared to patients with less severe COVID-19. Additionally, months after COVID-19 onset, ~17% of patients who had critical COVID-19 still had anemia, and these patients also had significantly higher serum IL-6 than nonanemic patients (47).

IL-1β and IL-1 Family Members

IL-1β is released from macrophages and neutrophils after activation of cytosolic innate sensors, including NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2, among others, leading to inflammasome formation and caspase-1 activation. These inflammasomes can form during both bacterial and viral infections, as well as during sterile inflammation. IL-1β contribution to anemia has been implicated via multiple mechanisms affecting erythropoiesis (Figure 2). This includes the inhibition of EPO expression by cells in the kidney (41), similar to that seen with IL-6, and the direct repression of erythroid progenitor proliferation. Additionally, IL-1β affects the balance of hematopoietic progenitor differentiation into erythroid versus myeloid cells by promoting myelopoiesis at the expense of erythropoiesis (48, 49). IL-1β exerts this effect by signaling through the NF-κB pathway, leading to increased expression of PU.1, the key myeloid lineage transcription factor (48). PU.1 directly inhibits DNA binding of the transcription factor GATA-1 (50), which is required for megakaryocyte/erythrocyte lineage commitment. Therefore, by inducing PU.1 expression, IL-1β shifts the balance of hematopoiesis during infection or inflammation toward myelopoiesis and away from erythropoiesis, a process often termed emergency myelopoiesis (4, 51) (Figure 2a). Similarly, the proinflammatory cytokine TNF induces PU.1 expression in HSCs through NF-κB signaling (52). While IL-1β plays an important role in emergency myelopoiesis and the response to acute inflammatory signals, chronic IL-1 signaling leads to HSC exhaustion and the potential for bone marrow failure (48). Several of these IL-1β-driven mechanisms leading to anemia have been documented in a mouse model for neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), the most severe form of cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndromes (CAPS), in which the NLRP3 inflammasome is constitutively active (53). This anemia, characterized by a reduction of RBCs and erythroid progenitors, required the expression of NLRP3 in myeloid cells and signaling via the IL-1 receptor, implicating IL-1β in this disease (53).

Additionally, a direct effect of inflammasome-induced caspase-1 activity on the balance between erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis has been demonstrated. Tyrkalska et al. (54) showed that inhibiting several inflammasome components in zebrafish embryos led to a reduction in myeloid cells and an increase in erythrocytes, while activating inflammasomes caused the opposite effect. Mechanistically, the authors found that caspase-1 cleaves GATA-1, increasing the PU.1/GATA-1 ratio and favoring myelopoiesis over erythropoiesis both during the steady state and during S. Typhimurium infection (Figure 2a). In a model of sterile neutrophilic dermatosis in zebrafish, caspase-1 inhibition rescued neutrophilia and anemia (54). Therefore, inflammasomes can cause anemia by direct inhibition of GATA-1 and indirect inhibition via IL-1β secretion from mature myeloid cells during infection and inflammatory disease.

IL-33, an IL-1 family member, can also promote anemia. Swann et al. (55) identified IL-33 as driving anemia in a mouse model of the autoimmune disease ankylosing spondylitis. They found that the ST2 receptor for IL-33 is highly expressed on erythroid progenitors, and following exposure to IL-33, erythroid progenitors had reduced differentiation into RBCs in vitro. In vivo administration of IL-33 in mice suppressed erythropoiesis, leading to anemia. Unlike some other cytokines discussed here, IL-33 suppressed erythropoiesis without inducing myeloid differentiation. Mechanistically, IL-33 prevented terminal differentiation of RBCs through NF-κB-dependent inhibition of EPOR signaling (Figure 2b), providing a novel mechanism by which this cytokine impacts erythropoiesis and drives anemia (55).

Interferons

Both type I (IFN-α, IFN-β) and type II (IFN-γ) interferons are produced during many infectious and inflammatory diseases. These cytokines have well-recognized roles in suppressing erythropoiesis by direct activity on human and mouse hematopoietic progenitors in vitro, including on those committed to the erythroid lineage, such as the highly proliferative erythroblast termed blast-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) (56–60) (Figure 2b). The critical role of IFN-γ in the development of anemia in vivo is highlighted in a CD70 transgenic mouse that develops anemia of inflammation in which T cells chronically produce IFN-γ in response to stimulation through CD27-CD70 interactions (61). Although anemia in this model is multifactorial, contributing factors include decreased RBC life span and decreased erythrocyte production. These effects were reversed in CD70 transgenic mice lacking IFN-γ, demonstrating that anemia in this model is IFN-γ dependent. Interestingly, treatment of MEPs with IFN-γ led to increased PU.1 expression via activation of the transcription factor IRF1 (61). Given that PU.1 directly inhibits GATA-1 function, this suggests that chronic IFN-γ skews bone marrow progenitor differentiation toward myeloid cells at the expense of erythrocytes (Figure 2a). Similarly, in a model of acute TLR9-driven secondary HLH in mice, Canna et al. (62) showed that administration of CpG DNA, a TLR9 agonist, led to decreased bone marrow erythropoiesis while promoting extramedullary erythropoiesis in the spleen. IFN-γ exacerbated anemia in this model by limiting extramedullary erythropoiesis. IFN-γ has also been implicated in promoting myelopoiesis during many bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections, including direct effects on hematopoietic progenitors and indirect effects on bone marrow stroma (reviewed in 60). Although many of these studies did not directly assess erythropoiesis, a similar mechanism as discussed above may be at play, where induction of PU.1 in hematopoietic progenitors such as common myeloid progenitors inhibits GATA-1 function, thereby promoting myelopoiesis over erythropoisis. Thus, in both acute and chronic sterile inflammatory diseases as well as a variety of infections, IFN-γ represses erythropoiesis.

Type I interferons are key antiviral cytokines that have also been implicated in directly suppressing erythropoiesis in vitro, as discussed above, though the effects seen were typically less potent than those of IFN-γ (56, 57). The suppressive effects of type I interferons on erythropoiesis have been seen during chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV infections in people treated with pegylated IFN-α, through both direct and indirect mechanisms (63–65). In addition to suppressing erythropoiesis directly, IFN-α treatment induced hepcidin in PBMCs and hepatocytes in vitro. In vivo, treatment of HCV and HBV patients with pegylated IFN-α resulted in increased serum hepcidin, a dramatic reduction in circulating iron, and anemia (63–65). Interestingly, stronger IFN-α-associated hepcidin induction and anemia were associated with a larger reduction in viral load in these patients (63, 64). Type I interferons also promote myelopoiesis during inflammation. In a TLR7-overexpressing model of lupus-like disease (66), we found that type I interferons drive emergency myelopoiesis in vivo by increasing proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells, although we did not assess whether type I interferons also repress erythropoiesis in this model (67). Mechanistically, type I interferons enhanced common myeloid progenitor proliferation and macrophage lineage differentiation in synergy with TLR7 signaling while increasing mRNA encoding PU.1 and repressing GATA-1 mRNA (68).

Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor

MIF is a pleiotropic cytokine that is expressed in multiple tissues during infection and inflammatory diseases. MIF’s role appears to be complex and context dependent, as there is evidence that it can promote proinflammatory signaling and contribute to multiple human diseases (69), or promote repair and wound-healing (70). Similarly, the effect of MIF during parasitic infections, such as leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, malaria, and toxoplasmosis, has been studied, but its specific role appears to depend on the model studied (70, 71).

Phagocytosis of the Plasmodium by-product hemozoin induces MIF production by both mouse macrophages and human monocytes, and MIF is detected in serum of both P. chabaudi-infected mice and Plasmodium falciparum–infected people (72, 73). Supporting a pathological role of MIF in driving malarial anemia, recombinant MIF suppresses erythropoiesis from human bone marrow progenitors in vitro, and MIF-deficient mice had reduced anemia and prolonged survival compared to wild-type mice during P. chabaudi infection (72, 73). Interestingly, MIF-dependent suppression of erythropoiesis in vitro was synergistic with TNF and IFN-γ, also prevalent during Plasmodium infection (73) and which can also directly suppress erythropoiesis, as discussed above (Figure 2b).[AU: Do you mean “above” (in this article)?**]

MIF has also been associated with anemia and liver damage during African trypanosomiasis, commonly known as sleeping sickness, caused by Trypanosoma brucei protozoans (74). MIF made by inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils accumulates in the serum, liver, spleen, and bone marrow of mice throughout the course of T. brucei infection. Similar to infection with P. chabaudi, T. brucei–infected mice lacking MIF had reduced anemia and prolonged survival (75). MIF-deficient mice also had higher serum hemoglobin and iron levels, increased iron availability, and more efficient erythropoiesis compared to wild-type mice during infection (75). A similar role for MIF was found in Trypanosoma congolense infection, which leads to a more chronic disease (76). Altogether, these data implicate myeloid cell–derived MIF in the suppression of erythropoiesis in both Trypanosoma and Plasmodium infections both through direct effects on erythroid progenitors and through indirect induction of inflammatory cytokines that can suppress erythropoiesis. Interestingly, multiple protozoan parasites, including Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Leishmania, produce MIF homologs that have been implicated in disease pathology (77). Whether Plasmodium-derived MIF can inhibit erythropoiesis is unclear, although it would seem counterintuitive given the parasite’s requirement for infection of RBCs. MIF is also elevated in human autoimmunity and in mouse models of autoimmune disease, although whether in these settings MIF contributes to anemia has not been addressed (78).

Plasmodium Hemozoin

The Plasmodium by-product hemozoin not only induces myeloid-produced cytokines that are associated with repression of erythropoiesis, such as MIF, TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β (72, 79, 80), but also can suppress erythropoiesis through direct effects on erythroid progenitors. Thawani et al. (81) showed that during mouse malarial infection, the proportion of blood monocytes with intracellular hemozoin correlated with anemia severity. Additionally, Plasmodium-derived hemozoin, and to a lesser extent synthetic hemozoin, directly suppressed EPO-induced proliferation of mouse and human erythroblasts, but not RBC maturation, in vitro. Similar effects were seen in vivo, where injection of Plasmodium-derived, but not synthetic, hemozoin caused transient anemia in mice (81). The differential effects of synthetic versus Plasmodium-derived hemozoin may provide mechanistic hints as to how hemozoin leads to suppressed erythropoiesis. Several studies have used synthetic hemozoin in an attempt to better understand its proinflammatory properties, including induction of the inflammatory cytokines that can directly (IL-1β, TNF) or indirectly (IL-6) repress erythropoiesis (79). It is interesting, therefore, that mice injected with Plasmodium-derived hemozoin, but not synthetic hemozoin, showed a rapid but transient decrease in RBCs followed by a compensatory increase in reticulocytes (81). The differences between synthetic and Plasmodium-derived hemozoin have not been defined; however, additional Plasmodium components, such as DNA or RNA, complexed with hemozoin may be necessary to induce cytokine production above a certain threshold to inhibit erythropoiesis in vivo through activation of nucleic acid–sensing pathogen recognition receptors, such as TLRs (82–84). For example, 5ʹ-methythioinosine (MTI), a P. falciparum purine metabolic intermediate, can activate TLR8 and lead to IL-6 and IL-1β production through NF-κB activation in vitro (85). The addition of MTI and P. falciparum RNA to human monocytes leads to significantly increased NF-κB activation. It is tempting to speculate that MTI and hemozoin would have a similar synergistic effect and may contribute to anemia in vivo.

Alterations in EPO Abundance and Function

As discussed above, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β that are produced during infection and inflammatory disease can inhibit EPO production in the kidney, leading to decreased RBC production. Anemia commonly develops in patients with the autoimmune disease SLE and can be due to low serum EPO concentrations secondary to chronic kidney disease (30). In addition, anti-EPO autoantibodies are common in SLE patients, with studies documenting 20–50% of examined patients having these autoantibodies (86–90). In individuals with SLE, anemia and disease activity correlated with reduced serum EPO concentrations and the presence of anti-EPO antibodies presumably due to increased clearance of EPO (86, 87, 89). In addition to anti-EPO autoantibodies, antibodies to EPOR, have also been documented in anemic SLE patients (90).

Anti-EPO antibodies have also been identified in patients with HIV and chronic HCV. Although anti-EPO antibodies in both SLE and HIV can correlate with anemia, unlike in SLE, the presence of these antibodies during HIV infection correlated with increased EPO serum concentrations (91, 92). Tsiakalos et al. (93) mapped the specificity of the anti-EPO antibodies in HIV infected individuals and found reactivity against EPO epitopes at the interaction interface with EPOR, indicating that the EPO-EPOR interaction may be blocked, thereby preventing EPO from driving erythropoiesis. The same group also documented anti-EPO antibodies in a cohort of treatment-naive HCV-infected patients. In this cohort, ~20% of the anemic HCV-infected patients had anti-EPO antibodies, compared to only 5% of nonanemic HCV-infected patients. The presence of anti-EPO antibodies also correlated with significantly increased viral loads (93). Other studies have found that although patients with chronic HCV have elevated serum EPO, they also have reduced hemoglobin, RBC counts, and reticulocyte counts, suggesting that EPO is not effectively driving erythropoiesis in these chronic viral infections, potentially due to the anti-EPO antibodies (94).

High levels of anti-EPO autoantibodies have also been seen in multiple strains of mice with malaria. Only one of the mouse strains showed a correlation between anti-EPO antibody levels and the degree of anemia, as well as decreased EPO levels (95). In contrast, anti-EPO antibodies were found only in ~2% of Plasmodium-infected children, and high levels of circulating EPO were found in both anemic and nonanemic infected individuals (96). Because anemia during Plasmodium infection is multifactorial, anti-EPO antibodies may contribute to anemia in some contexts but not others.

In summary, alterations in EPO’s effectiveness during infectious or inflammatory diseases can be caused by reduced EPO production in the kidney or anti-EPO autoantibodies that either increase EPO clearance, leading to reduced serum EPO, or block the ability of EPO to bind to its receptor. It would be interesting to determine whether autoantibodies against EPOR also contribute to anemia in these diseases, particularly in cases where the level of serum EPO is high.

INCREASES IN RED BLOOD CELL CLEARANCE

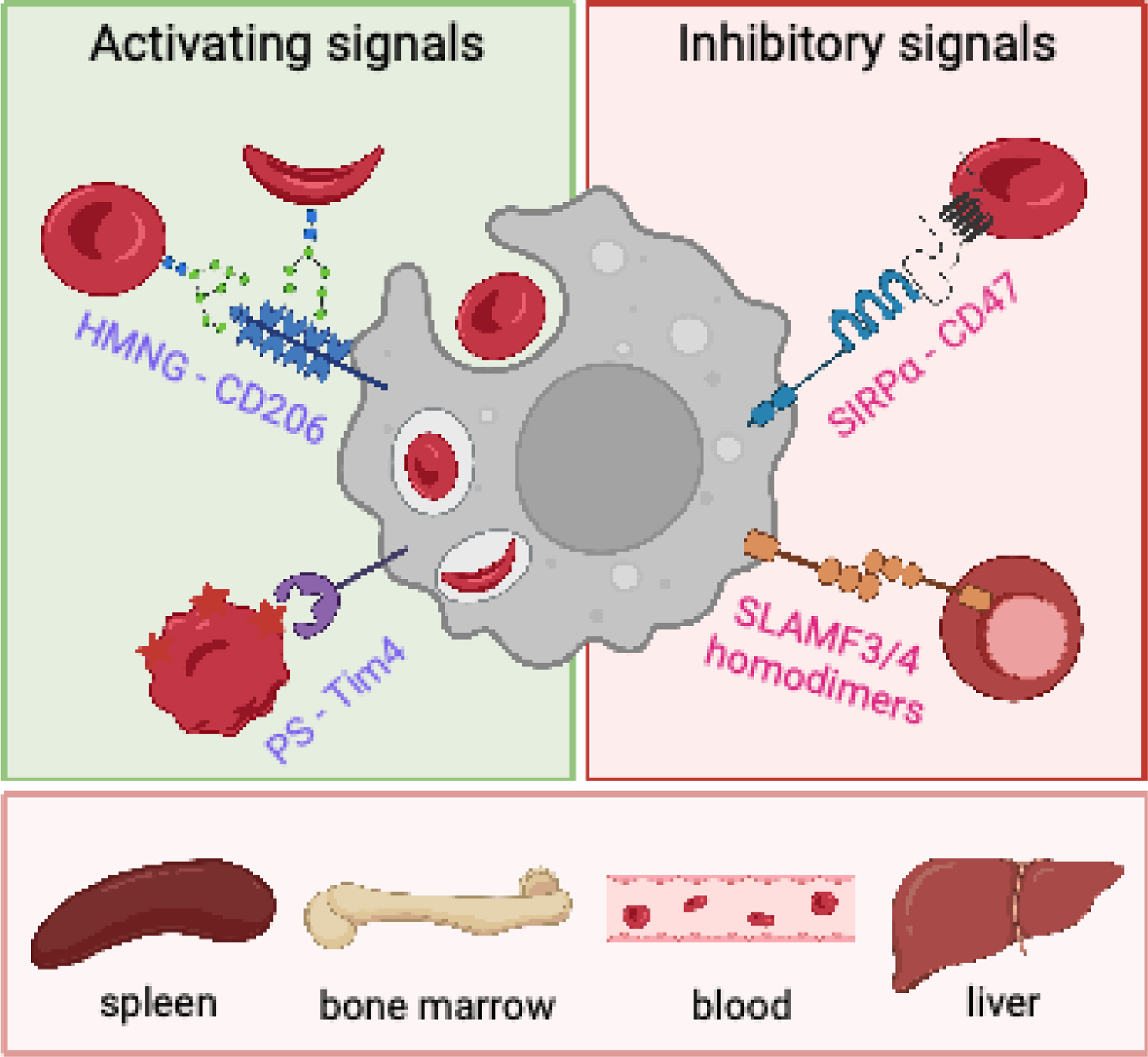

Increased RBC clearance by phagocytes represents the other side of the inflammatory anemia equation (Figure 1). During homeostasis, the spleen is the principal site of clearance via specialized tissue macrophages situated in the red pulp—red pulp macrophages (RPMs)—though liver phagocytes can also remove damaged RBCs (9, 97). During infection and inflammation, the hemophagocytic capacity of the spleen and liver increases, and in some cases of extreme inflammation, hemophagocytes are also seen in the bone marrow. Increased hemophagocytosis during inflammation can be mediated by tissue macrophages such as RPMs, and perhaps more importantly, de novo differentiation of circulating monocytes into macrophages with high hemophagocytic capacity. Anemia can also be due to direct destruction of RBCs seen during some infections (98) and in autoimmune hemolytic anemia (30). In this section, we discuss hemophagocytosis during inflammation, focusing on receptor-ligand pairs regulating hemophagocytosis (Figure 3), cytokines, and hemophagocyte differentiation.

Figure 3.

Signals regulating hemophagocytosis. During many inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune diseases, increased phagocytic destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) in the spleen, liver, blood, and bone marrow can contribute to anemia. During inflammation, hemophagocytes are licensed by cytokines to phagocytose RBCs (not shown). Prophagocytic signals that promote RBC phagocytosis (left) include the mannose receptor (MR, CD206) binding to high-mannose N-glycans (HMNGs) on RBCs, and Tim-4 binding to surface-exposed phosphatidylserine (PS). Conversely, signals that normally inhibit hemophagocytosis (right) may be absent or decreased during inflammation. For example, disruptions to the SIRPα-CD47 inhibitory axis, such as decreased CD47 expression on RBCs, can lead to hemophagocytosis. Similarly, disruptions of the homotypic interactions of SLAMF3 or SLAMF4 on phagocytes and nucleated erythroblasts can cause hemophagocytosis.

SIGNALS THAT REGULATE RED BLOOD CELL PHAGOCYTOSIS

CD47-SIRPα

The mechanisms by which RBCs are recognized and phagocytosed by macrophages during homeostasis or inflammation are not well understood(9). As discussed above, the recognition of CD47 on RBCs by the macrophage inhibitory receptor SIRPα protects healthy, young RBCs from phagocytosis (Figure 3). Several mechanisms have been suggested for how this inhibitory interaction is overcome upon RBC aging, including (a) a reduction in CD47 expression, (b) altered CD47 membrane distribution that disrupts strong cross-linking of SIRPα, and (c) conformational changes in CD47 with age that lead to a switch in signaling via SIRPα from inhibitory to activating (11, 12). Additionally, increases in RBC rigidity with age are associated with increased hemophagocytosis. In vivo, increased rigidity leads to trapping of aged RBCs in the splenic red pulp cords, which can lead to prolonged interactions with RPMs and increased likelihood of phagocytosis. The increase in rigidity in aged RBCs is associated with cytoskeletal changes that may also change the ability of CD47 to cluster and provide strong signals through SIRPα (9). However, the relative contributions of these mechanisms of RBC CD47 regulation along with positive phagocytic signals to RBC phagocytosis are not clear (Figure 3).

What is clear is that the CD47-SIRPα signaling axis contributes to protection from anemia during infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases. One interesting case is that of Plasmodium infection, where RBCs are directly infected, and thus phagocytosis of infected RBCs serves as a mechanism to clear the pathogen. In mouse models with several species of rodent Plasmodium, infection of CD47-deficient mice or mice with defective SIRPα signaling led to faster clearance of the parasites and increased survival (99, 100). CD47 expression is decreased on P. falciparum–infected human RBCs, and blockade of SIRPα promoted monocyte phagocytosis of P. falciparum–infected human RBCs. Interestingly, some Plasmodium species, such as P. yoelii, preferentially infect reticulocytes, which have higher CD47 expression, suggesting this may help protect the parasitized RBCs from phagocytic clearance (100).

Alterations in CD47 expression on RBCs also occur during systemic infection of mice with Mycobacteria avium, which is used as a model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and can lead to anemia associated with increased mortality risk (101). In this model, the development of poor-quality erythrocytes with features such as decreased cell size and surface expression of CD47 was IFN-γ-dependent. During M. avium infection, increased erythrophagocytosis was due to abnormal RBC properties, as opposed to macrophage changes in hemophagocytic potential (102). Therefore, through direct or indirect mechanisms, infections can lead to reduced CD47 expression on RBCs and allow for clearance by hemophagocytes. Because IFN-γ is commonly seen during infectious and inflammatory diseases, it is interesting to speculate that the generation of RBCs with reduced CD47, or other properties altered by IFN-γ that promote hemophagocytosis, is a common mechanism of anemia during inflammation. IFN-γ also has a complex role in regulating macrophages themselves for hemophagocytosis, as discussed below.

Another interesting case is that of secondary HLH. In a mouse model driven by repetitive TLR9 agonist injections, Kidder et al. (103) found that HLH disease was more severe in SIRPα-deficient mice and was accompanied by increased hemophagocytosis in the spleen. Curiously, CD47 deficiency only partly recapitulated the disease phenotype seen in the absence of SIRPα but was key in driving hemophagocytosis and anemia. Of note, CD47 downregulation on HSCs has been implicated in driving phagocytosis of HSCs by macrophages in primary HLH (104). Treating HSCs with a combination of M-CSF, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF caused downregulation of HSC CD47 and subsequent phagocytosis by macrophages, suggesting that a proinflammatory environment can lead to reduced CD47 expression. However, whether this process occurs in developing erythrocytes was not investigated, although MEPs did not show reduced CD47 in HLH patients (104). Therefore, while the CD47-SIRPα axis is implicated in driving overall reduced hematopoiesis due to phagocytic depletion of HSCs in HLH, a specific role in anemia and hemophagocytosis in this disease has not yet been established.

SLAM Family Receptors

SLAM family receptors, found on hematopoietic cells, are a family of seven receptors (SLAMF1–7) that have mainly homotypic interactions, except for SLAMF4, which binds SLAMF2 (105). Much of the focus for SLAMF receptors has been on their regulation of lymphocyte responses, although several family members are expressed on macrophages and their phagocytic targets, where they can regulate phagocytosis. SLAMF7 was identified as a macrophage phagocytic receptor for hematopoietic tumor cells when the SIRPα-CD47 interaction was blocked (106). However, SLAMF7 is not expressed in RBCs, suggesting that SLAMF7 homotypic interactions do not play a role in RBC phagocytosis. SLAMF7 has also been identified as a driver of macrophage activation during inflammatory diseases (107). In contrast, the SLAM family receptors SLAMF3 and SLAMF4 were recently identified as negative regulators of phagocytosis of hematopoietic cells, acting in concert with SIRPα-CD47 as don’t-eat-me signals (108). SLAMF3 and SLAMF4 are not expressed on mature RBCs and thus do not regulate phagocytosis of these cells, although they are expressed on nucleated erythroblasts, where they inhibit phagocytosis by macrophages. Therefore, SLAMF3 and SLAMF4 may prevent anemia by protecting erythroblasts from phagocytosis (Figure 3).

Interestingly, concurrent deficiency in SLAMF2–6 exacerbated cytopenias in response to repeated TLR7 signaling in vivo, though RBCs were not quantified in these experiments. The authors also showed that SLAMF3 expression and SLAMF4 expression are decreased, whereas SLAMF7 expression is increased, in HLH patients (108). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that changes in SLAM family receptors may contribute to both anemia and other cytopenias in HLH and other inflammatory disorders.

Phagocytic Receptors and Ligands

Phagocytosis requires the activation of prophagocytic receptors in addition to the removal of inhibitory signals, as discussed above. Several receptor-ligand pairs mediating phagocytosis of RBCs during inflammation have been identified, though it is likely that more receptors participate in this process and have yet to be elucidated. Additionally, the relevant receptor-ligand pairs may vary by the inflammatory situation. The integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2), composed of a CD11b/CD18 heterodimer, was implicated as a hemophagocytic receptor in LPS-treated macrophages (109). Mac-1 binds several ligands, including complement component C3 and ICAM-1, although it is unlikely that ICAM-1 is a relevant ligand for hemophagocytosis of RBCs, because RBCs do not express this protein. In several situations described in the literature, exposure of PS on the surface of RBCs can promote RBC phagocytosis. PS is a phospholipid normally found on the inner leaflet of the membrane bilayer, and it can be externalized as RBCs age or during apoptosis. Surface PS is a quintessential eat-me signal on cells. Increased PS exposure was seen in RBCs during LCMV infection as well as after repeated TLR9 agonist administration, where it caused hemophagocytosis by monocyte-derived cells (110). Hemophagocytosis in these inflammatory situations was mediated via a combination of the PS-binding receptors Tim-1 and Tim-4, and αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins, which bind PS indirectly through thrombospondin (110) (Figure 3). Interestingly, in SCA patients up to 10% of deoxygenated HbSS RBCs have exposed PS (111, 112), which could enhance phagocytosis of these sickle RBCs via PS-binding receptors. Thus, recognition of prematurely exposed PS by phagocytic receptors during inflammation may contribute to inflammatory anemias.

Another factor that can lead to enhanced phagocytosis of RBCs is the generation of autoantibodies against RBC antigens, a phenomenon that occurs during a number of infections (113). Autoantibodies to PS produced by atypical B cells have been described in mice and humans infected with Plasmodium or T. brucei (114, 115). Anti-PS autoantibodies bind to exposed PS on the surface of RBCs from Plasmodium-infected mice. In vitro, these anti-PS antibodies enhanced phagocytosis of RBCs from infected, but not uninfected, mice despite high CD47 expression. Injection of purified anti-PS antibodies into mice with malaria led to prolonged anemia; conversely, blocking PS in mice infected with Plasmodium or T. brucei led to improved recovery from anemia (114, 115). Similarly, plasma anti-PS autoantibodies correlated with anemia in people with malaria or trypanosomiasis, suggesting a significant role of these autoantibodies in promoting RBC clearance in both parasitic infections via Fc receptor–mediated phagocytosis or RBC destruction through the complement pathway. Anti-PS autoantibodies are also seen in SLE, where their presence correlates with an increased risk of hemolytic anemia, presumably through complement-mediated destruction (116).

Changes in RBC surface glycosylation have also been implicated in allowing phagocytic recognition and increased hemophagocytosis in sickle cell disease and malaria. Cao et al. (117) showed that HbSS RBCs have patches of cell surface high-mannose N-linked glycans (HMNGs) not seen on HbAA RBCs. In vitro, these HMNGs induced hemophagocytosis by macrophages through CD206, the mannose receptor. Supporting this is a mechanism driving SCA in vivo; RBC count in individuals with SCA is correlated with high mannose expression on RBCs. High mannose expression was also increased in normal RBCs under conditions of oxidative stress and during P. falciparum infection, suggesting that this may be a more general mechanism for hemophagocytosis during certain inflammatory and infectious conditions that lead to RBC stress (117).

Changes in Red Blood Cell Physical Properties and Splenic Filtration

As discussed above, with age RBCs undergo changes in deformability and have increased rigidity. This increased rigidity leads to their retention in splenic red pulp cords and increased clearance by RPMs (118). Through in vitro assays, Sosale et al. (119) showed that rigid RBCs form stronger myosin-II bonds with THP-1 macrophages than normal RBCs. Even with intact CD47-SIRPα binding, strong myosin-II binding drives rapid phagocytosis. Some evidence also suggests that increased rigidity may contribute to the clearance of RBCs during infection. RBCs infected with P. falciparum are less easily deformed, depending on the stage of the parasite life cycle (120). These more rigid, P. falciparum–infected RBCs are retained and cleared in the red pulp of the spleen, as shown in an ex vivo human spleen model (121). Other pathogens that directly infect RBCs have also been described to alter RBC rigidity leading to increased phagocytic clearance, including Babesia parasites and Bartonella bacteria (reviewed in 98). During T. brucei infection, Szempruch et al. (122) found that extracellular vesicles released from the parasites fused with human and mouse RBCs, leading to altered RBC properties in vitro, including increased rigidity, incorporation of parasite glycoproteins on the RBC surface, and changes in membrane lipid composition. Together, these changes contributed to increased clearance of extracellular vesicle–fused RBCs infused into naive mice. Increased RBC rigidity is also seen in people with sickle cell disease, associated with increased RBC clearance.

Changes to RBC shape have also been associated with DNA binding. Binding of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) by RBCs was seen in vivo during inflammation, such as during COVID-19 pneumonia and sepsis in humans, as well as in mouse models of sepsis and infection with Legionella pneumophila and Toxoplasma gondii (123, 124). This is notable, as increased serum mtDNA has been associated with increased disease severity in critically ill patients in intensive care units (125). In vitro, mtDNA binding caused altered cytoskeletal proteins and a dramatic change in shape, reduced surface CD47 expression, and altered CD47 conformation. In vivo, binding of mtDNA to RBCs resulted in increased hemophagocytosis and rapid clearance in the spleen (124). Therefore, multiple direct and indirect signals lead to altered RBC properties and subsequent clearance during infection and inflammation.

During circulation RBCs are filtered through the splenic cords, and retention in this region can increase phagocytic clearance by RPMs. There is some evidence that this filtration process can change during infection. The Fulani, an ethnic group that lives in West Africa, are less susceptible to disease during P. falciparum infection compared to other sympatric ethnic groups as measured by incidence of symptomatic infection, parasitemia, and severity of symptoms (126, 127). However, a larger proportion of Fulani individuals with malaria have spleen enlargement and anemia compared to other ethnic groups (127–129). A study using a spleen-mimicking filtration system found that Fulani people had increased splenic filtration and increased clearance of infected, rigid RBCs (129). In support of the hyperstringent RBC filtration model, a genome-wide association study identified several SNPs in Fulani people, some of which are highly expressed in the spleen and could be related to increased filtration of RBCs. Notably, the authors suggested that some of the identified genes could play a role in increased splenic retention through increased extracellular matrix interactions and alterations in RBC rigidity, leading to increased phagocytosis (129). Therefore, increased splenic filtration may also promote clearance of RBCs, leading to anemia.

Cytokines

Downregulation of don’t-eat-me signals in the absence of inflammation may not be sufficient to promote hemophagocytosis, highlighting a role for cytokines in this process. In fact, mice lacking CD47 (130) or SIRPα (109) have normal RBC counts and no overt signs of disease. Similarly, in some of the inflammatory situations described above, newly formed erythrocytes had lower CD47 surface expression but were not completely devoid of CD47. Bian et al. (109) showed that at steady state, mice lacking SIRPα or CD47 did not show increased RBC clearance, nor did resting macrophages phagocytose CD47-deficient RBCs, with the exception of splenic RPMs. However, under a variety of inflammatory conditions in vivo, there was robust hemophagocytosis leading to anemia. These observations raised the question of how macrophages are licensed to phagocytose “self” RBCs during both homeostatic and inflammatory conditions. In combination with PKC- and Syk-dependent signaling, certain inflammatory signals could license macrophages for phagocytosis of CD47-deficient RBCs in vitro, including the cytokines IL-17, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF, as well as the TLR4 agonist LPS. This is particularly interesting in terms of secondary HLH, where many mouse models of disease also rely on stimulation of TLRs (22–25) that induce the production of these same cytokines that enhance hemophagocytosis. Interestingly, the cytokine MIF, which has potent inhibitory effects on erythropoiesis during parasitic infections, also promotes hemophagocytosis by macrophages, potentially due to MIF activation of NF-κB and Syk signaling (76, 131). Therefore, during inflammation, such as in infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases, a combination of reduced CD47 expression and macrophage licensing driven by cytokine signaling may allow for pathogenic hemophagocytosis.

As previously mentioned, IFN-γ is produced during many infections and inflammatory diseases, and increased IFN-γ is associated with primary and secondary HLH (132–136). However, whether IFN-γ is a primary driver of hemophagocytosis in inflammatory anemias is not clear. To address whether IFN-γ can directly cause hemophagocytosis and anemia, Zoller et al. (137) infused IFN-γ into mice, which led to increased hemophagocytosis by splenic RPMs and anemia in a STAT1- and IRF1-dependent manner. Importantly, IFN-γ signaling in macrophages themselves was required for hemophagocytosis in this model. IFN-γ caused increased macrophage membrane ruffling, actin polymerization, and pinocytosis, which were suggested to drive an overall increase in phagocytic capacity. A similar role for IFN-γ in driving hemophagocytosis and anemia in vivo was found in the CD70 transgenic overexpression model of anemia of chronic disease discussed above (61). This contrasts with the results of Bian et al. (109) described above, where IFN-γ was one of the few cytokines tested in vitro that could not license macrophage phagocytosis of CD47-deficient RBCs. In mouse models of primary and secondary HLH, dependence on IFN-γ for anemia and other pathologies associated with disease is variable. The primary HLH model using LCMV infection of perforin-deficient mice showed that anemia, hemophagocytosis, and a majority of the HLH immunopathology develop independently of IFN-γ signaling (138). However, treatment with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, rescued the mice from severe anemia and thrombocytopenia in this same model (139) Similarly, IFN-γ was dispensable for hemophagocytosis in the secondary HLH model driven by repeated injection of the TLR9 agonist CpG DNA, but this cytokine was required for development of anemia (22, 62). Together, these studies suggest that while IFN-γ can promote hemophagocytosis in vivo in some models of inflammatory anemia, in other models IFN-γ is not playing a role, is redundant with other signals, or causes anemia primarily by repressing erythropoiesis.

Mice infected with S. Typhimurium develop chronic, systemic infection and disease that closely resembles secondary HLH (140, 141). In addition to splenomegaly and anemia, infected mice had increased numbers of hemophagocytes in the spleen and extramedullary erythropoiesis. In vitro experiments showed that bone marrow–derived macrophages infected with S. Typhimurium had increased phagocytosis of healthy RBCs, similar to what occurred after treatment with LPS and IFN-γ (142). However, whether this increased hemophagocytosis in vivo was due to IFN-γ was not assessed. Interestingly, macrophages containing intracellular RBCs had an increased intracellular bacterial burden, which was also seen in liver macrophages in vivo. Increased hemophagocytosis by macrophages containing bacteria may promote bacterial growth through increased intracellular iron availability but may also be one mechanism that contributes to the development of anemia during S. Typhimurium infection.

Hemophagocytes

In the steady state, embryonic-derived splenic RPMs are the major population of hemophagocytes that phagocytose senescent RBCs and recycle heme-derived iron for new erythropoiesis. During many situations of infection and inflammation, increased hemophagocytes are seen by histology in blood-rich organs including the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. In many cases in the mouse, these cells are defined as F4/80+, indicating that they are RPMs in the spleen and Kupffer cells in the liver. While tissue macrophages, including RPMs and Kupffer cells, maintain their populations by proliferation in situ during the steady state, more recently it has been recognized that circulating Ly6Chi monocytes can differentiate into these hemophagocytes. This can occur when RPMs die and there is a need to replenish the niche, such as during blood-stage Plasmodium infection and during experimentally induced heme overload (143, 144). Interestingly, during Plasmodium infection, death of RPMs and Kupffer cells was documented to occur prior to detectable increases in hemophagocytosis seen at later stages of infection, potentially due to inflammatory Plasmodium products, such as hemozoin or glycosylphosphatidylinositol (144). In contrast, Theurl et al. (97) showed that even in the absence of inflammation, when there was a need for increased removal of damaged or stressed RBCs, Ly6Chi monocytes phagocytosed damaged RBCs in circulation. These RBC-laden monocytes then accumulated in the liver, where they differentiated into cells they termed transient macrophages, which upregulated genes associated with iron recycling, and then delivered iron to hepatocytes. While these transient macrophages were also seen in the spleen, they did not upregulate iron-recycling genes such as that encoding ferroportin in this organ. The authors also found that these transient macrophages differentiate in other mouse models of anemia, including anemia caused by experimental hemolysis, Brucella abortus infection, and in sickle cell disease, though they did not assess whether they contributed to the anemia seen in these settings (97).

We recently identified a unique population of specialized hemophagocytes in situations of inflammation associated with anemia, including in mouse models of MAS and severe malarial anemia (23). These inflammatory hemophagocytes (iHPCs) differentiated from Ly6Chi monocytes in response to endosomal TLR signaling. We first identified iHPCs in a lupus model driven by transgenic TLR7 overexpression (66), where we found that mice developed MAS-like disease, including severe anemia (23). In this TLR7 overexpression model, iHPC differentiation required cell-intrinsic overexpression of TLR7, demonstrating that direct signaling via this endosomal RNA sensor in Ly6Chi monocytes promotes hemophagocyte differentiation. iHPCs also differentiated in a model of SMA caused by blood-stage P. yoelii 17XNL infection. During Plasmodium infection, iHPC differentiation required cell-intrinsic MyD88 and UNC93b1 expression (23). Along with in vitro experiments, our findings implicate both endosomal TLR7 and TLR9 signaling, as well as the transcription factor IRF5 downstream of these receptors, in driving iHPC differentiation. How iHPCs relate to the transient macrophages described by Theurl et al. (97) is not clear. However, both populations of hemophagocytes were found in spleen, while transient macrophages were also seen in blood and liver and iHPCs were seen in bone marrow (23, 97). Interestingly, Ohyagi et al. (110) identified splenic monocyte-derived hemophagocytes during LCMV infection and repeated TLR9 agonist injection. However, these cells were described as monocyte-derived dendritic cells and their contribution to anemia was not assessed. Taken together, these studies support the idea that monocyte-derived hemophagocytes are more important in inflammatory anemia than tissue macrophages.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Here we have discussed a variety of immune mechanisms that contribute to inflammatory anemia, affecting both RBC production and RBC clearance. Though many of the diseases we discussed are quite distinct from each other, both common and unique mechanisms emerge from this review of the literature. Several inflammatory cytokines either directly repress erythropoiesis or do so indirectly by limiting iron availability, inhibiting EPO production and function, or promoting myelopoiesis at the expense of erythropoiesis during emergency myelopoiesis. Autoantibodies against the key RBC growth and differentiation factor EPO are also seen not only in the autoimmune disease SLE but also during several chronic viral infections and infections with Plasmodium parasites. Increased phagocytic RBC clearance is also common to most of the diseases discussed. This increased clearance in inflammatory settings is typically due to a combination of altered RBC properties, including changes in cell surface proteins, altered shape and rigidity, and enhanced hemophagocytic activity. This increased hemophagocytosis expands from the spleen as the principal site of RBC clearance during homeostasis to also include the liver, blood, and bone marrow during inflammation. Strikingly, the identity of the hemophagocytes also changes, from principally tissue-resident macrophages, such as RPMs, to principally monocyte-derived hemophagocytes during inflammation. Overall, there is a strong connection between decreased erythropoiesis and increased RBC removal through the process of emergency myelopoiesis, which both suppresses erythropoiesis and provides a large number of monocytes that can differentiate into hemophagocytes.

Although there have been many fundamental insights into how inflammatory anemias occur during infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases, many facets of the mechanisms contributing to inflammatory anemia remain to be elucidated. We still understand relatively little about hemophagocyte differentiation from monocytes and the range of signals that contribute to this process. Are unique transcription factors required for monocyte-derived hemophagocyte differentiation? What is the specific role of TLRs and other innate sensors in this process? Are all monocyte-derived hemophagocytes the same, or do they differ by the tissue and signal driving their differentiation? We also do not have a full understanding of the receptors and ligands that regulate hemophagocytosis during inflammation. In particular, it is likely that the receptor-ligand interactions promoting RBC phagocytosis both during homeostasis and during inflammation remain to be identified, and we do not yet have a precise understanding of the mechanistic switches that alter CD47-SIRPα interactions to allow for hemophagocytosis. A better understanding of the mechanisms of inflammatory anemias not only will give us fundamental knowledge of how inflammatory anemia occurs, but may also identify common intervention points that could be targeted therapeutically when this anemia becomes severe, such as in malaria, or MAS and HLH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to our those whose work could not be cited due to space constraints. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01AR076242, R01AI150178, and R21AI154841 to J.A.H.; F32HL154700 to S.L.O.; T32AR007108, T32HD007233, and F32HL156516 to S.P.C.; and F31A1172078 to N.K.T. Additional funding to J.A.H. was provided by the Lupus Research Alliance (Lupus Mechanisms and Targets Award) and to S.P.C. by the Arthritis National Research Foundation (Kelly Rouba-Boyd Fellowship), CARRA, and the Arthritis Foundation through financial support of CARRA (CARRA-Arthritis Foundation Career Development Award).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Chaparro CM, Suchdev PS. 2019. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1450(1):15–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nairz M, Weiss G. 2020. Iron in infection and immunity. Mol. Aspects Med 75:100864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. 2019. Anemia of inflammation. Blood 133(1):40–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultze JL, Mass E, Schlitzer A. 2019. Emerging principles in myelopoiesis at homeostasis and during infection and inflammation. Immunity 50(2):288–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doulatov S, Notta F, Laurenti E, Dick JE. 2012. Hematopoiesis: a human perspective. Cell Stem Cell 10(2):120–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieger MA, Schroeder T. 2012. Hematopoiesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 4(12):a008250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pucella JN, Upadhaya S, Reizis B. 2020. The source and dynamics of adult hematopoiesis: insights from lineage tracing. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 36:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zivot A, Lipton JM, Narla A, Blanc L. 2018. Erythropoiesis: insights into pathophysiology and treatments in 2017. Mol. Med 24(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neri S, Swinkels DW, Matlung HL, van Bruggen R. 2021. Novel concepts in red blood cell clearance. Curr. Opin. Hematol 28(6):438–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oldenborg P-A, Zheleznyak A, Fang Y-F, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. 2000. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science 288(5473):2051–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha B, Lv Z, Bian Z, Zhang X, Mishra A, Liu Y. 2013. “Clustering” SIRPα into the plasma membrane lipid microdomains is required for activated monocytes and macrophages to mediate effective cell surface interactions with CD47. PLOS ONE 8(10):e77615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv Z, Bian Z, Shi L, Niu S, Ha B, et al. 2015. Loss of cell surface CD47 clustering formation and binding avidity to SIRPα facilitate apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages. J. Immunol 195(2):661–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grom AA, Horne A, Benedetti FD. 2016. Macrophage activation syndrome in the era of biologic therapy. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 12(5):259–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bracaglia C, Prencipe G, Benedetti FD. 2017. Macrophage Activation Syndrome: different mechanisms leading to a one clinical syndrome. Pediatr. Rheumatol 15(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canna SW, Marsh RA. 2020. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 135(16):1332–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang K, Jordan MB, Marsh RA, Johnson JA, Kissell D, et al. 2011. Hypomorphic mutations in PRF1, MUNC13–4, and STXBP2 are associated with adult-onset familial HLH. Blood 118(22):5794–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulert GS, Zhang M, Fall N, Husami A, Kissell D, et al. 2016. Whole-exome sequencing reveals mutations in genes linked to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and macrophage activation syndrome in fatal cases of H1N1 influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 213(7):1180–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vastert SJ, van Wijk R, D’Urbano LE, de Vooght KMK, de Jager W, et al. 2010. Mutations in the perforin gene can be linked to macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 49(3):441–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, Cunningham K, Moreira R, Gould C. 2007. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect. Dis 7(12):814–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henter J, Ehrnst A, Andersson J, Elinder G. 1993. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and viral infections. Acta Paediatr 82(4):369–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. 2004. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Blood 104(3):735–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behrens EM, Canna SW, Slade K, Rao S, Kreiger PA, et al. 2011. Repeated TLR9 stimulation results in macrophage activation syndrome-like disease in mice. J. Clin. Investig 121(6):2264–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akilesh HM, Buechler MB, Duggan JM, Hahn WO, Matta B, et al. 2019. Chronic TLR7 and TLR9 signaling drives anemia via differentiation of specialized hemophagocytes. Science 363(6423):eaao5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang A, Pope SD, Weinstein JS, Yu S, Zhang C, et al. 2019. Specific sequences of infectious challenge lead to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like disease in mice. PNAS 116(6):2200–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strippoli R, Carvello F, Scianaro R, Pasquale LD, Vivarelli M, et al. 2012. Amplification of the response to Toll-like receptor ligands by prolonged exposure to interleukin-6 in mice: implication for the pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatism 64(5):1680–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canna SW, de Jesus AA, Gouni S, Brooks SR, Marrero B, et al. 2014. An activating NLRC4 inflammasome mutation causes autoinflammation with recurrent macrophage activation syndrome. Nat. Genet 46(10):1140–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romberg N, Moussawi KA, Nelson-Williams C, Stiegler AL, Loring E, et al. 2014. Mutation of NLRC4 causes a syndrome of enterocolitis and autoinflammation. Nat. Genet 46(10):1135–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White NJ. 2018. Anaemia and malaria. Malaria J 17(1):371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsokos GC. 2020. Autoimmunity and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Immunol 21(6):605–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giannouli S, Voulgarelis M, Ziakas PD, Tzioufas AG. 2006. Anaemia in systemic lupus erythematosus: from pathophysiology to clinical assessment. Ann. Rheumatic Diseases 65(2):144–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elkon KB, Wiedeman A. 2012. Type I IFN system in the development and manifestations of SLE. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol 24(5):499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muskardin TLW, Niewold TB. 2018. Type I interferon in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 14(4):214–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, Gaston MH, Ohene-Frempong K, et al. 2018. Sickle cell disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4(1):18010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aidoo M, Terlouw DJ, Kolczak MS, McElroy PD, ter Kuile FO, et al. 2002. Protective effects of the sickle cell gene against malaria morbidity and mortality. Lancet 359(9314):1311–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. 2013. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010–2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLOS Med 10(7):e1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uyoga S, Olupot-Olupot P, Connon R, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, et al. 2022. Sickle cell anaemia and severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a secondary analysis of the Transfusion and Treatment of African Children Trial (TRACT). Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal 6(9):606–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Archer NM, Petersen N, Clark MA, Buckee CO, Childs LM, Duraisingh MT. 2018. Resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in sickle cell trait erythrocytes is driven by oxygen-dependent growth inhibition. PNAS 115(28):7350–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams TN, Mwangi TW, Wambua S, Alexander ND, Kortok M, et al. 2005. Sickle cell trait and the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and other childhood diseases. J. Infect. Dis 192(1):178–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, Camaschella C. 2019. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Front Physiol 10:1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. 2006. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood 108(9):3204–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jelkmann W 1998. Proinflammatory cytokines lowering erythropoietin production. J. Interf. Cytokine Res 18(8):555–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skaar EP. 2010. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLOS Pathog 6(8):e1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Somia IKA, Merati TP, Bakta IM, Manuaba IBP, Yasa WPS, et al. 2019. High levels of serum IL-6 and serum hepcidin and low CD4 cell count were risk factors of anemia of chronic disease in HIV patients on the combination of antiretroviral therapy. HIV AIDS 11:133–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nai A, Lorè NI, Pagani A, Lorenzo RD, Modica SD, et al. 2021. Hepcidin levels predict Covid-19 severity and mortality in a cohort of hospitalized Italian patients. Am. J. Hematol 96(1):E32–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yağcı S, Serin E, Acicbe Ö, Zeren Mİ, Odabaşı MS. 2021. The relationship between serum erythropoietin, hepcidin, and haptoglobin levels with disease severity and other biochemical values in patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Lab. Hematol 43(Suppl. 1):142–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellmann-Weiler R, Lanser L, Barket R, Rangger L, Schapfl A, et al. 2020. Prevalence and predictive value of anemia and dysregulated iron homeostasis in patients with COVID-19 infection. J Clin Med 9(8):2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonnweber T, Boehm A, Sahanic S, Pizzini A, Aichner M, et al. 2020. Persisting alterations of iron homeostasis in COVID-19 are associated with non-resolving lung pathologies and poor patients’ performance: a prospective observational cohort study. Respir. Res 21(1):276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pietras EM, Mirantes-Barbeito C, Fong S, Loeffler D, Kovtonyuk LV, et al. 2016. Chronic interleukin-1 exposure drives haematopoietic stem cells towards precocious myeloid differentiation at the expense of self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol 18(6):607–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caiado F, Pietras EM, Manz MG. 2021. Inflammation as a regulator of hematopoietic stem cell function in disease, aging, and clonal selection. J. Exp. Med 218(7):e20201541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolff L, Humeniuk R. 2013. Concise review: erythroid versus myeloid lineage commitment; regulating the master regulators. Stem Cells 31(7):1237–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orozco SL, Canny SP, Hamerman JA. 2021. Signals governing monocyte differentiation during inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol 73:16–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Etzrodt M, Ahmed N, Hoppe PS, Loeffler D, Skylaki S, et al. 2019. Inflammatory signals directly instruct PU.1 in HSCs via TNF. Blood 133(8):816–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang C, Xu C-X, Alippe Y, Qu C, Xiao J, et al. 2017. Chronic inflammation triggered by the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells promotes growth plate dysplasia by mesenchymal cells. Sci. Rep 7(1):4880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyrkalska SD, Pérez-Oliva AB, Rodríguez-Ruiz L, Martínez-Morcillo FJ, Alcaraz-Pérez F, et al. 2019. Inflammasome regulates hematopoiesis through cleavage of the master erythroid transcription factor GATA1. Immunity 51(1):50–63.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swann JW, Koneva LA, Regan-Komito D, Sansom SN, Powrie F, Griseri T. 2020. IL-33 promotes anemia during chronic inflammation by inhibiting differentiation of erythroid progenitors. J. Exp. Med 217(9):e20200164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Broxmeyer HE, Lu L, Platzer E, Feit C, Juliano L, Rubin BY. 1983. Comparative analysis of the influences of human gamma, alpha and beta interferons on human multipotential (CFU-GEMM), erythroid (BFU-E) and granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) progenitor cells. J. Immunol 131(3):1300–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raefsky EL, Platanias LC, Zoumbos NC, Young NS. 1985. Studies of interferon as a regulator of hematopoietic cell proliferation. J. Immunol 135(4):2507–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang CQ, Udupa KB, Lipschitz DA. 1995. Interferon-γ exerts its negative regulatory effect primarily on the earliest stages of murine erythroid progenitor cell development. J. Cell. Physiol 162(1):134–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai CH, Price JO, Brunner T, Krantz SB. 1998. Fas ligand is present in human erythroid colony-forming cells and interacts with Fas induced by interferon gamma to produce erythroid cell apoptosis. Blood 91(4):1235–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Bruin AM, Voermans C, Nolte MA. 2014. Impact of interferon-γ on hematopoiesis. Blood 124(16):2479–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Libregts SF, Gutiérrez L, de Bruin AM, Wensveen FM, Papadopoulos P, et al. 2011. Chronic IFN-γ production in mice induces anemia by reducing erythrocyte life span and inhibiting erythropoiesis through an IRF-1/PU.1 axis. Blood 118(9):2578–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canna SW, Wrobel J, Chu N, Kreiger PA, Paessler M, Behrens EM. 2013. Interferon-γ mediates anemia but is dispensable for fulminant Toll-like receptor 9-induced macrophage activation syndrome and hemophagocytosis in mice. Arthritis Rheum 65(7):1764–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jia J, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Chen Z, Chen L, et al. 2022. Hepcidin expression levels involve efficacy of pegylated interferon-α treatment in hepatitis B-infected liver. Int. Immunopharmacol 107:108641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan JD, Altamura S, Devitt E, Mullins S, Lawless MW, et al. 2012. Pegylated interferon-α induced hypoferremia is associated with the immediate response to treatment in hepatitis C. Hepatology 56(2):492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rijnsoever M, Galhenage S, Mollison L, Gummer J, Trengove R, Olynyk JK. 2016. Dysregulated erythropoietin, hepcidin, and bone marrow iron metabolism contribute to interferon-induced anemia in hepatitis C. J. Interferon Cytokine Res 36(11):630–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]