Abstract

Bacteria produce natural products (NPs) via biosynthetic gene clusters. Unfortunately, many biosynthetic gene clusters are silent under traditional laboratory conditions. To access novel NPs, a better understanding of their regulation is needed. γ-Butyrolactones, including the A-factor and Streptomyces coelicolor butanolides, SCBs, are a major class of Streptomyces’ hormones. Study of these hormones has been limited due to challenges in accessing them in stereochemically pure forms. Herein, we describe an efficient route to (R)-paraconyl alcohol, a key intermediate for these molecules, as well as a biocatalytic method to access the exocyclic hydroxyl group that differentiates A-factor-type from SCB-type hormones. Utilizing these methods, a library of hormones have been synthesized and tested in a green fluorescent protein reporter assay for their ability to relieve repression by the repressor ScbR. This allowed the most quantitative structure–activity relationship of γ-butyrolactones and a cognate repressor to date. Bioinformatics analysis strongly suggests that many other repressors of NP biosynthesis likely bind similar molecules. This efficient, diversifiable synthesis will enable further investigation of the regulation of NP biosynthesis.

Introduction

Natural products (NPs) have played a vital role in drug discovery, exhibiting a wide range of structures and bioactivities.1 NPs isolated from the Gram-positive soil-dwelling bacteria Streptomyces are important sources of antibiotic, antifungal, antiparasitic, and anticancer treatments, as well as many other medicines and agricultural chemicals.2 A multitude of uncharacterized NP biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) exist in Streptomyces strains,3−6 suggesting an untapped source of structurally diverse, bioactive NPs. Unfortunately, many of these NPs are “silent” (i.e., produced at undetectable levels) when grown in the laboratory.7 Having a molecular understanding of the regulatory systems that control production of NPs is essential for maximizing the NP potential from Streptomyces and identifying novel biological probes and leads for drug discovery.

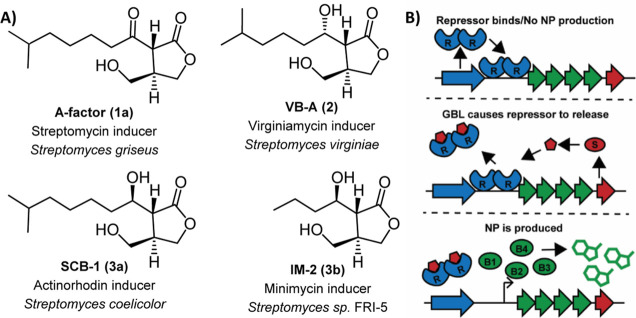

Small-molecule hormones are known to control transcription of BGCs.8Streptomyces utilizes small-molecule autoregulators such as γ-butyrolactones (GBLs), γ-butenolides, and methylenomycin furans (MMFs) to control transcription of NP BGCs.9−15 For example, auto-inducing factor (A-factor),16Streptomyces coelicolor butanolide 2 (SCB-2),10 virginiae butanolide A (VB-A),17 and IM-218 are GBLs that have been shown to regulate the production of streptomycin, actinorhodin, virginiamycin, and minimycin, respectively (Figure 1A). GBLs stimulate the production of NPs by binding to cluster-situated TetR-type repressors, releasing the repressors from upstream of the BGCs and inducing transcription (Figure 1B).19 Genetic evidence suggests that >60% of Streptomyces strains use GBL-type ligands,20 and more recent genomics analyses suggest that GBLs may be widespread in other bacteria including other Actinobacteria as well as Proteobacteria.21 However, only 19 GBLs and butenolides from 8 Streptomyces species, along with 2 from Salinispora species, have been identified to date.8,19,22 They differ in the length, branching, and stereochemistry of their fatty acid side chains. While early reports suggest that each repressor is highly specific for its ligand, more recent studies suggest that there may be crosstalk between bacterial strains via shared or similar ligands.10,16,23,24

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of GBL hormones that induce production of NPs. The NPs they induce along with the producing strain are listed below each structure. (B) Mechanism by which hormones derepress the repressors of NP biosynthesis. Receptors (R) prevent the production of NPs. Production of a hormone by its synthase (S) followed by binding to R results in the release of R and induction of NPs.

The SCB-type hormones from S. coelicolor are one of the best studied of the GBLs. Takano and co-workers performed initial studies, first with antibiotic stimulation assays and then with an engineered kanamycin resistance assay.9,10,25 While these works were essential for beginning to establish ground rules for repressor-ligand selectivity, they were limited in two important areas. First, the assays were only semi-quantitative, requiring analysis of growth halos for activity. Second, nearly all of the molecules examined were racemic mixtures, likely because of the challenge involved in developing asymmetric routes to these molecules. Unfortunately, stereochemical mixtures can have dramatic effects on observed results, as exhibited in a recent study of the induction of paulomycin in Streptomyces albus.24 Specifically, paulomycin production was induced upon heterologous production of natural SCBs, as confirmed by mass spectrometry. However, when a racemic mixture of synthetic SCB2 was used, no induction was observed. It is possible that the wrong enantiomer may inhibit activation or that timing of exposure to the SCBs differed between the heterologous expression and synthetic hormone experiments. Having access to enantiopure hormones would enable further understanding of these results.

In this work, we sought to develop an easily diversifiable, stereoselective route to A-factor-type and SCB-type hormones. An efficient and inexpensive route to the key intermediate (R)-paraconyl alcohol was developed, and the native SCB ketoreductase ScbB was successfully adapted as a biocatalyst for the reduction of A-factor-type hormones to SCB-type hormones. Access to enantiomerically and diastereomerically pure molecules, combined with the development of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter assay, enabled the first truly quantitative studies capable of exploring structure–activity relationships for hormones with the repressor ScbR. This work has also allowed us to probe crosstalk of the ScbR repressor with hormones originally isolated from other bacteria. Overall, the synthetic route to stereochemically pure GBLs in combination with a quantitative activity assay will enable future exploration of ligands for other repressors, especially those bioinformatically predicted to bind hormones structurally similar to those that bind ScbR.

Results and Discussion

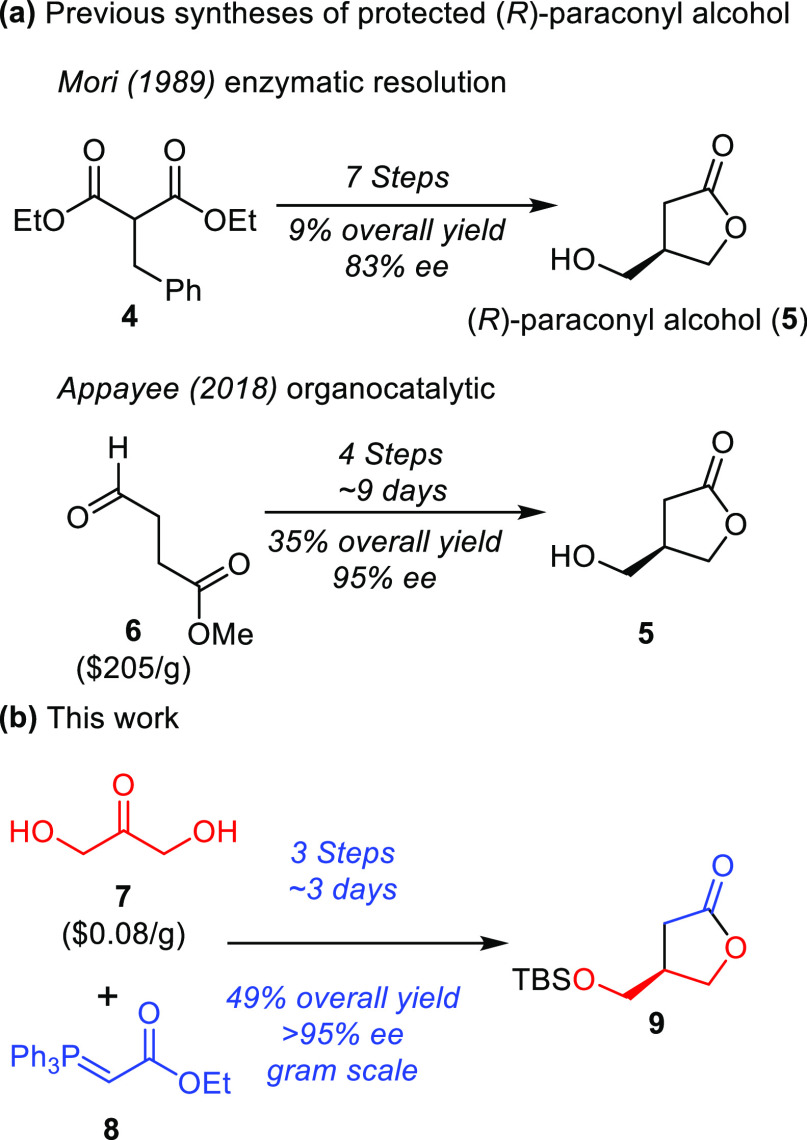

Accessing Protected (R)-Paraconyl Alcohol and Enantiopure A-Factor-Type GBLs

Chemical synthesis of GBLs typically involves the generation of the common core, paraconyl alcohol (5, Scheme 1A), followed by alcohol protection and incorporation of the required side chains via either an aldol reaction or acylation and subsequent reduction of the ketone.16,26−28 While many routes exist to access racemic paraconyl alcohol, few enantioselective syntheses have been reported.26,27,29,30 (R)-Paraconyl alcohol has previously been synthesized using a lipase enzymatic resolution strategy in 7 steps with a 9% overall yield and 83% ee.31 The low stereoselectivity of this process led Appayee and co-workers to explore a chiral auxiliary approach.26 Impressively, they were able to access (R)-paraconyl alcohol in just 4 steps with a 35% yield and 95% ee. However, this route requires a relatively expensive starting material (6, Scheme 1A) and long reaction times. Given the importance of (R)-paraconyl alcohol for the synthesis of stereochemically pure GBLs, as well as many other NPs, we sought an alternate route that could more rapidly provide (R)-paraconyl alcohol from inexpensive starting materials. Drawing inspiration from recent work on the synthesis of (S)-3-fluoromethyl-γ-butyrolactone,32 we envisioned a Wittig olefination of the cheap and commercially available dihydroxyacetone (7) with (carbethoxymethylene)triphenylphosphorane (10, Scheme 1B). Olefination and transesterification proceeded well, giving the free butenolide without the need for column chromatography (Scheme 2). Protection of the free alcohol afforded the protected butenolide (10) in 75% yield over 2 steps. With the protected butenolide in hand, various conditions for asymmetric reduction were explored. In the synthesis of (S)-3-fluoromethyl-γ-butyrolactone, Rh-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate reduction was utilized.32 While this yielded enantiopure products, we wished to avoid the need for high-pressure hydrogenation reactions. For this reason, hydrogenolysis with copper hydride was examined. Inspired by Buchwald and Lipschutz,33,34 (R)-p-tol-BINAP with polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS) was found to provide 9 in good yield (65% yield) and excellent stereoselectivity (>95% ee, Figure S1).

Scheme 1. Routes to (R)-Paraconyl Alcohol.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of A-Factor-Type γ-Butyrolactones.

This improved route to 9 allowed us to access a variety of stereochemically pure GBLs for biological evaluation. Specifically, we chose to target A-factor from Streptomyces griseus (1a), along with other A-factor-type hormones, including exocyclic ketone derivatives of IM-2 and the SCB hormones. Acylation of the core was carried out with NaHMDS and the respective acyl chlorides to give these molecules in yields ranging from 55 to 70%. Gratifyingly, a single diastereomer was isolated, as evidenced by 1H NMR and polarimetry. Silyl deprotection of compounds 11a–i allowed access to the natural A-factor (1a) and several A-factor-type hormones that have not previously been observed in nature (compounds 1b–i).

Biocatalytic Reduction of A-Factor-Type to SCB-Type Hormones

With the A-factor-type hormones in hand, reduction conditions were explored. Previously reported attempts at chemo-reduction of A-factor-type hormones via Luche and Noyori conditions resulted mixes of diastereomers (Figure 2A).26,35 Ketoreductases are widely used in numerous systems to afford improved stereoselectivity.36 Recently, Hyster and co-workers used a ketoreductase (KRED300) to reduce the exocyclic ketone of another β-ketolactone en route to the bicyclic darunavir side chain.37 While KRED300 efficiently and selectively reduces the exocyclic ketone, it unfortunately gives the opposite stereochemistry to that needed to access the SCB-type hormones. To identify an enzyme capable of this reduction, the biosynthetic pathway for the SCB hormones was explored (Figure 2B and Scheme S1). The biosynthesis of the SCB hormones begins with ScbA catalyzing a transacylation reaction between dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP, 17) and fatty acyl-CoA esters.38,39 After a spontaneous cyclization, ScbC reduces the butenolide to the butyrolactone and the phosphate is then removed by a phosphatase. Finally, the NADPH-dependent ketoreductase ScbB converts the A-factor-type molecules into the SCB hormones (Scheme S1). Heterologous expression of the enzyme ScbB in E. coli was successful at 30 mg/L (Figure S2A). Preliminary attempts to reduce kSCB2 (1c) with an excess of NADPH resulted in good conversion. For this reason, NADPH recycling systems were explored. The common glucose-6-phosphate/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6P/G6PDH) successfully generated the product (Figure S2B). A buffer scan was then performed and revealed that a HEPES buffer provided excellent conversion of the model substrate. Utilizing these optimal conditions, the remaining substrates were tested (Figure 3). Although isolated yields are low due to solubility issues in aqueous media and low levels of competing hydrolysis of the A-Factor type molecules, conversion of the substrates shows the efficiency of ScbB (Figure 3B). Side-chain lengths from 6 to 9 carbons were well tolerated as well as differing branching positions. Interestingly, kIM-2 (1b), which only has a 4-carbon chain, resulted in lower turnover, suggesting that a minimal chain length is necessary for optimal activity. Gratifyingly, the diastereomeric ratio is improved upon the previously reported conditions. The reduction is also scalable, with a 0.235 mmol reaction of kSCB8 (1i), resulting in 47% isolated yield. From the success observed with the endogenous ScbB, it is likely that other ketoreductases involved in hormone biosynthesis from Streptomyces species may be effective biocatalysts for accessing other understudied signaling hormones.

Figure 2.

(A) Previous reduction methods for A-factor-type molecules. (B) Biosynthetic route for SCB-type GBLs.

Figure 3.

(A) General scheme for ScbB-catalyzed reduction of A-factor-type GBLs to SCB-type GBLs. (B) Substrate scope for ScbB-catalyzed reduction. dr = diastereomeric ratio.

GFP-Reporter Assay Allows Structure–Function Analyses for Relief of Repression of ScbR

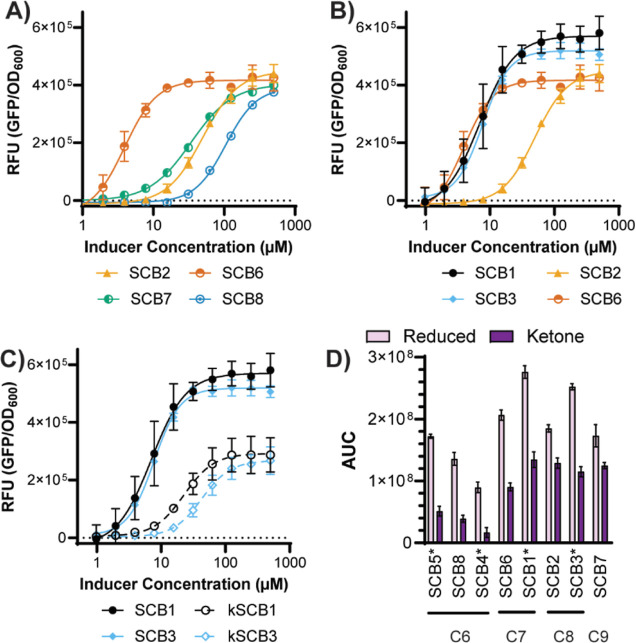

After establishing a route to stereochemically pure A-factor-type and SCB-type hormones, we chose to explore their abilities to act as ligands for the S. coelicolor repressor ScbR. Others have previously used fluorescence reporter assays to identify agonists and antagonists of transcription factors.40−43 Additionally, Voigt and Takano have utilized fluorescence reporter assays to explore ScbR as a component for genetic circuits.44,45 However, to date, no one has used such assays to quantitatively determine structure–activity relationships for ScbR ligands. Herein, a plasmid-based GFP reporter assay in E. coli was developed (Figure S3A,B). Comparison to a control plasmid with no repressor revealed a good range of activity (Figure S3C). Synthetic hormones were screened for their ability to relieve ScbR repression of gfp transcription in a dose-dependent manner, enabling determination of EC50, Emax, and Hill coefficient for each molecule (Figure 4A–C, Table S1, and Figure S4). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were also performed, and the results compared well with the GFP assay (Figure S5). Every active molecule had a Hill coefficient greater than 1, suggesting cooperativity of binding. This is consistent with ligand binding seen with other TetR-type repressors.43 The EC50 values are higher than those needed to see activation in the native system. This is not surprising, given that constitutive expression of ScbR from the strong promoter BBa_J23100 (Registry of Standard Biological Parts) leads to protein levels that are assuredly higher than in vivo expression in the native host. The higher protein levels of ScbR would need higher amounts of molecules to see relief of repression compared to the native system, which likely has much lower levels of ScbR. Overall, we chose to compare molecules based on the area under the curve (AUC) because it has previously been shown to best combine the information obtained from the EC50, Emax, and Hillslope (Figure 4D).40,46 Side-chain length was found to have a prominent effect on activation with a chain length of seven carbons (SCB6 and SCB1) being the most effective with six, eight, and nine carbons (SCB8, SCB2, and SCB7, respectively) having higher EC50 values but similar Emax values. Interestingly, this differs from previous work in which SCB2 was found to be more effective than SCB6.10 This difference could be due to previous use of racemic mixtures or the less quantitative kanamycin assay. Gratifyingly, the overall trend of shorter chains (e.g., six carbons) and longer chains (e.g., nine carbons) being less potent was consistent with the previous reports. In addition to chain length, chain branching was also explored. SCB1 and SCB3, both of which have a methyl branch at carbon 6 of the side chain, had similar potency to linear SCB6 but slightly higher Emax values. This is intriguing because Streptomyces utilizes primarily branched chain fatty acids, compared to other bacteria such as E. coli, and may suggest a method for selectivity. Unsurprisingly, branch position also plays an important role. SCB4 and SCB5, which have methyl branches at carbon 3 and 4 of the side chain, respectively, are much less potent. Finally, the exocyclic hydroxyl of the SCB-type hormones is essential for potent activation. When comparing reduced SCB1 and SCB3 to their oxidized counterparts kSCB1/A-factor and kSCB3, a significant reduction in Emax and increase in EC50 are observed (Figure 4D). This is particularly interesting, given that the A-factor controls production of streptomycin in S. griseus. This selectivity may protect against crosstalk between S. coelicolor and S. griseus.

Figure 4.

GFP reporter assay results for (A) hormones of varying chain lengths, (B) hormones with differing branching patterns, and (C) hormones with differing oxidation states. Data shown are averages of at least 3 biological replicates with standard error of the mean indicated. Graphs for all hormones along with EC50, Emax, and Hillslope can be found in the Figure S4 and Table S1. (D) AUC for both the SCB-type hormones (alcohol, light purple) and A-factor-type hormones (ketone, dark purple). Molecules are organized from the shortest side chain on the left to the longest side chain on the right with length indicated below the molecules (C6–C9). * indicates a hormone with a branched side chain.

In addition to exploring SCB-type and A-factor-type hormones, two other hormone types were explored. The MMFs are another type of hormone produced by S. coelicolor. While the MMFs and SCBs are biosynthesized from similar starting materials, they ultimately give structurally distinct hormones. Others have previously demonstrated that the MMF receptor is unable to respond to SCBs.14 Herein, we have demonstrated that the reverse is also true. MMFs are unable to relieve ScbR inhibition (Figures S4 and S5). This is supportive of individual Streptomyces strains having multiple orthogonal hormones that control different biosynthetic pathways. The acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) are quorum sensing molecules that are produced by Gram-negative bacteria. We were able to confirm previous reports that AHLs are incapable of relieving ScbR inhibition (Figures S4 and S5). This implies that these bacteria do not cross-activate each other. However, it remains to be seen if they are capable of inhibiting one another.

Bioinformatics Analyses of Bacterial Genomes Suggest that SCB-Type Hormones Are Widespread

Previous studies have suggested that the phylogenetic trees of hormone receptors can predict the types of molecules that they bind.19 The topology of these trees indicates that the receptors likely cluster based on the structure of their ligands and their DNA binding domains. However, these analyses were limited to fewer than one hundred strains. To further assess this hypothesis, we have generated the largest ScbR phylogenetic tree to date with 406 predicted TetR types repressors (Figure 5). We found that the known receptors separate well in the tree, supporting the fact that the receptor sequence could be predictive of ligand specificity. ScbR and FarA, which both bind SCB-type molecules, are in the same clade, along with many other receptors likely to bind SCB-type hormones. Interesting, JadR3, which also binds SCB-type hormones, is found in a different clade. This may be due to a difference in the DNA-binding portion of the enzyme. ArpA, the only receptor known to bind A-factor-type molecules (ArpA), is found in a separate clade with a handful of other receptors. Interestingly, BarA, which binds the VB hormones, appears to be alone in the phylogentic tree. However, that may be due to undersampling. Finally, the receptors that bind the butenolide-type hormones (SrrA and SabR1) are together in another clade, providing strong support for the hypothesis that the ligand structure may be predictable based on receptor phylogeny. The clusters containing ScbR, FarA, and JadR3 are large clades, suggesting that many receptors likely respond to SCB-type hormones. Analysis of hormone BGCs in the genome neighborhood of the predicted repressors further confirms their likely structural similarity.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree for repressors known (colored and indicated) and predicted to bind GBL hormones. The full tree with all repressors identified and with bootstrap values can be found in Figure S6.

Conclusions

Regulation of production remains understudied for the majority of NPs. GBLs and the repressors they release are a common type of NP regulatory system. Herein, we have developed routes to stereochemically pure SCB-type and A-factor-type hormones. These syntheses enabled structure–function evaluation utilizing a GFP-based reporter assay. While the natural SCB-type hormones had the best activity, activity was still observed for others such as A-factor, suggesting that some crosstalk may occur. However, crosstalk to other classes of hormones such as the MMFs and AHLs appears to not occur. Bioinformatics analyses of uncharacterized clusters suggest that many repressors similar to those that respond to SCB-type and A-factor-type hormones exist and may also be activated by these hormones. Future studies will focus on identifying ligands for many of these currently uncharacterized receptors. The ability to synthesize stereochemically pure A-factor-type and SCB-type hormones will greatly expedite the studies of these repressors and ultimately lead to the discovery of regulation systems for many NPs.

Experimental Section

Experimental details can be found in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an NSF CAREER Award to E.I.P. (CHE 223689) and the ACS Herman Frasch Fund for Chemical Research to E.I.P. (934-HF22). L.E.W. was supported by a Purdue Research Foundation Ross-Lynn Grant. C.D.M. was supported by an NIH F32 postdoctoral fellowship (F32 GM140569-01). This work was supported in part by the Research Instrumentation Center in the Department of Chemistry at Purdue University. The authors acknowledge the support from the Purdue Center for Cancer Research, NIH grant P30 CA023168. The authors are grateful to A.K. Ghosh (Purdue University) for allowing us to use his polarimeter.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschembio.3c00241.

Materials and methods, enantiomeric excess, ScbB biocatalysis optimization, design of the GFP reporter assay, GFP reporter assay results, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, full phylogenetic tree, GFP assay result, primers used, strains and plasmids used, synthetic methods, and NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Author Contributions

§ L.E.W. and H.E.H. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérdy J. Bioactive Microbial Metabolites. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 1–26. 10.1038/ja.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroghazi J. R.; Metcalf W. W. Comparative Genomics of Actinomycetes with a Focus on Natural Product Biosynthetic Genes. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 611. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroghazi J. R.; Albright J. C.; Goering A. W.; Ju K.-S.; Haines R. R.; Tchalukov K. A.; Labeda D. P.; Kelleher N. L.; Metcalf W. W. A Roadmap for Natural Product Discovery Based on Large-Scale Genomics and Metabolomics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 963–968. 10.1038/nchembio.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pye C. R.; Bertin M. J.; Lokey R. S.; Gerwick W. H.; Linington R. G. Retrospective Analysis of Natural Products Provides Insights for Future Discovery Trends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 5601–5606. 10.1073/pnas.1614680114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzolo A. M. E.; Simons C. L. W.; Burke M. D. The Natural Productome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 5564–5566. 10.1073/pnas.1706266114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge P. J.; Challis G. L. Discovery of Microbial Natural Products by Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 509–523. 10.1038/nrmicro3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel-Ivad M.; Pimentel-Elardo S.; Nodwell J. R. Control of Specialized Metabolism by Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation: Opportunities for New Platforms for Drug Discovery?. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 72, 25–48. 10.1146/annurev-micro-022618-042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano E.; Nihira T.; Hara Y.; Jones J. J.; Gershater C. J.; Yamada Y.; Bibb M. Purification and Structural Determination of SCB1, a Gamma-Butyrolactone That Elicits Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 11010–11016. 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao N.-H.; Nakayama S.; Merlo M. E.; de Vries M.; Bunet R.; Kitani S.; Nihira T.; Takano E. Analysis of Two Additional Signaling Molecules in Streptomyces Coelicolor and the Development of a Butyrolactone-Specific Reporter System. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 951–960. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K.; Tsuda N.; Taniguchi A.; Kinashi H. The Butenolide Signaling Molecules SRB1 and SRB2 Induce Lankacidin and Lankamycin Production in Streptomyces Rochei. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 1447–1457. 10.1002/cbic.201200149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy F. G.; Eaton K. P.; Limsirichai P.; Aldrich J. F.; Plowman A. K.; King R. R. Characterization of γ-Butyrolactone Autoregulatory Signaling Gene Homologs in the Angucyclinone Polyketide WS5995B Producer Streptomyces Acidiscabies. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4786–4797. 10.1128/JB.00437-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitani S.; Miyamoto K. T.; Takamatsu S.; Herawati E.; Iguchi H.; Nishitomi K.; Uchida M.; Nagamitsu T.; Omura S.; Ikeda H.; Nihira T. Avenolide, a Streptomyces Hormone Controlling Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces Avermitilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 16410–16415. 10.1073/pnas.1113908108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Bhukya H.; Malet N.; Harrison P. J.; Rea D.; Belousoff M. J.; Venugopal H.; Sydor P. K.; Styles K. M.; Song L.; Cryle M. J.; Alkhalaf L. M.; Fülöp V.; Challis G. L.; Corre C. Molecular Basis for Control of Antibiotic Production by a Bacterial Hormone. Nature 2021, 590, 463–467. 10.1038/s41586-021-03195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidda J. D.; Poon V.; Song L.; Wang W.; Yang K.; Corre C. Overproduction and Identification of Butyrolactones SCB1–8 in the Antibiotic Production Superhost Streptomyces M1152. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 6390–6393. 10.1039/C6OB00840B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov A. S.Problems of Studies of Specific Cell Autoregulators (on the Example of Substances Produced by Some Actinomycetes). Frontiers of Bioorganic Chemistry and Molecular Biology; Elsevier, 1980; pp 201–210.. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y.; Sugamura K.; Kondo K.; Yanagimoto M.; Okada H. The structure of inducing factors for virginiamycin production in Streptomyces virginiae. J. Antibiot. 1987, 40, 496–504. 10.7164/ANTIBIOTICS.40.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K.; Nihira T.; Sakuda S.; Yamada Y. IM-2, a butyrolactone autoregulator, induces production of several nucleoside antibiotics in Streptomyces sp. FRI-5. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1992, 73, 449–455. 10.1016/0922-338X(92)90136-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson L.; Nodwell J. R. The TetR Family of Regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 440–475. 10.1128/mmbr.00018-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkade A. V.; Mantri S. S.; Patwekar U. J.; Jangid K. Quorum Sensing: An Under-Explored Phenomenon in the Phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 131. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer K. E.; Kudo Y.; Moore B. S.; Jensen P. R. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Salinipostin γ-Butyrolactone Gene Cluster Uncovers New Potential for Bacterial Signalling-Molecule Diversity. Microb. Genomics 2021, 7, 000568. 10.1099/mgen.0.000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo Y.; Awakawa T.; Du Y. L.; Jordan P. A.; Creamer K. E.; Jensen P. R.; Linington R. G.; Ryan K. S.; Moore B. S. Expansion of Gamma-Butyrolactone Signaling Molecule Biosynthesis to Phosphotriester Natural Products. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 3253–3261. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. B.; Kitani S.; Shimma S.; Nihira T. Butenolides from Streptomyces Albus J1074 Act as External Signals to Stimulate Avermectin Production in Streptomyces Avermitilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02791 10.1128/AEM.02791-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wang M.; Tian J.; Liu J.; Guo Z.; Tang W.; Chen Y. Activation of Paulomycin Production by Exogenous γ-Butyrolactone Signaling Molecules in Streptomyces Albidoflavus J1074. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1695–1705. 10.1007/s00253-019-10329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano E.; Chakraburtty R.; Nihira T.; Yamada Y.; Bibb M. J. A Complex Role for the γ-Butyrolactone SCB1 in Regulating Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 41, 1015–1028. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkale A. M.; Kumar A.; Appayee C. Organocatalytic Approach for Short Asymmetric Synthesis of (r)-Paraconyl Alcohol: Application to the Total Syntheses of IM-2, SCB2, and a-Factor γ-Butyrolactone Autoregulators. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 4167–4172. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawforth J. M.; Fawcett J.; Rawlings B. J. Asymmetric Synthesis of A-Factor. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 10, 1721–1726. 10.1039/a708638e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nihira T.; Shimizu Y.; Kim H. S.; Yamada Y. Structure-Activity Relationships of Virginiae Butanolide C, an Inducer of Virginiamycin Production in Streptomyces Virginiae. J. Antibiot. 1988, 41, 1828–1837. 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K.; Chiba N. Preparative Bioorganic Chemistry, XI Preparation of the Enantiomers of Paraconic Acid Employing Lipase-Mediated Asymmetric Hydrolysis of Prochiral Diacetates as the Key Step. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1989, 1989, 957–962. 10.1002/jlac.198919890251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morin J. B.; Adams K. L.; Sello J. K. Replication of Biosynthetic Reactions Enables Efficient Synthesis of A-Factor, a γ-Butyrolactone Autoinducer from Streptomyces Griseus. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 1517–1520. 10.1039/c2ob06653j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffers E.; Golebiowski A.; Johnson C. R. Enantioselective Synthesis through Enzymatic Asymmetrization. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 3769–3826. 10.1016/S0040-4020(95)01021-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adam J.-M.; Foricher J.; Hanlon S.; Lohri B.; Moine G.; Schmid R.; Stahr H.; Weber M.; Wirz B.; Zutter U. Development of a Scalable Synthesis of ( S )-3-Fluoromethyl-γ-Butyrolactone, Building Block for Carmegliptin’s Lactam. Moiety. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2011, 15, 515–526. 10.1021/op200019k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes G.; Kimura M.; Buchwald S. L. Catalytic Enantioselective Conjugate Reduction of Lactones and Lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11253–11258. 10.1021/ja0351692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshutz B. H.; Servesko J. M.; Taft B. R. Asymmetric 1,4-Hydrosilylations of α,β-Unsaturated Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8352–8353. 10.1021/ja049135l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner P.; Jiang H.; Nielsen J. B.; Pasi F.; Jørgensen K. A. A Modular and Organocatalytic Approach to γ-Butyrolactone Autoregulators from Streptomycetes. Chem. Commun. 2008, 30, 5827–5829. 10.1039/b812698d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Snajdrova R.; Moore J. C.; Baldenius K.; Bornscheuer U. T. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic Synthesis for Industrial Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 88–119. 10.1002/ANIE.202006648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehl P. S.; Lim J.; Finnigan J. D.; Charnock S. J.; Hyster T. K. An Efficient Synthesis of the Bicyclic Darunavir Side Chain Using Chemoenzymatic Catalysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 2096–2101. 10.1021/acs.oprd.2c00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J.; Funa N.; Watanabe H.; Ohnishi Y.; Horinouchi S. Biosynthesis of Gamma-Butyrolactone Autoregulators That Switch on Secondary Metabolism and Morphological Development in Streptomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 2378–2383. 10.1073/pnas.0607472104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao N. H.; Söding J.; Linke D.; Lange C.; Hertweck C.; Wohlleben W.; Takano E. ScbA from Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2) Has Homology to Fatty Acid Synthases and Is Able to Synthesize γ-Butyrolactones. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1394–1404. 10.1099/MIC.0.2006/004432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. R.; Hasty J. Quorum Sensing Communication Modules for Microbial Consortia. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 969–977. 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdt J. P.; Wittenwyler D. M.; Combs J. B.; Boursier M. E.; Brummond J. W.; Xu H.; Blackwell H. E. Chemical Interrogation of LuxR-Type Quorum Sensing Receptors Reveals New Insights into Receptor Selectivity and the Potential for Interspecies Bacterial Signaling. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2457–2464. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlee B. R.; Geske G. D.; Blackwell H. E.; Handelsman J. Identification of Synthetic Inducers and Inhibitors of the Quorum-Sensing Regulator Lasr in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by High-Throughput Screening. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8255–8258. 10.1128/aem.00499-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S. K.; Tahlan K.; Yu Z.; Nodwell J. Investigation of Transcription Repression and Small-Molecule Responsiveness by TetR-Like Transcription Factors Using a Heterologous Escherichia Coli-Based Assay. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 6655–6664. 10.1128/jb.00717-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B. C.; Nielsen A. A. K.; Tamsir A.; Clancy K.; Peterson T.; Voigt C. A. Genomic Mining of Prokaryotic Repressors for Orthogonal Logic Gates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 99–105. 10.1038/nchembio.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biarnes-Carrera M.; Lee C.-K.; Nihira T.; Breitling R.; Takano E. Orthogonal Regulatory Circuits for Escherichia Coli Based on the γ-Butyrolactone System of Streptomyces Coelicolor. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 1043–1055. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.; Pang L. Comparing Statistical Methods for Quantifying Drug Sensitivity Based on in Vitro Dose-Response Assays. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2012, 10, 88–96. 10.1089/adt.2011.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.