Abstract

In Azotobacter vinelandii, nitrogen fixation is regulated at the transcriptional level by an unusual two-component system encoded by nifLA. Certain mutations in nifL result in the bacterium releasing large quantities of ammonium into the medium, and earlier work suggested that this occurs by a mechanism that does not involve NifA, the activator of nif gene transcription. We have investigated a number of possible alternative mechanisms and find no evidence for their involvement in ammonium release. Enhancement of NifA-mediated transcription, on the other hand, by either elimination of nifL or overexpression of nifA, resulted in ammonium release, correlating with enhanced levels of nifH mRNA, raised levels of nitrogenase and acetylene-reducing activity, and increased concentrations of intracellular ammonium. Up to 35 mM ammonium can accumulate in the medium. Where measured, intracellular levels exceeded extracellular levels, indicating that rather than being actively transported, ammonium is lost from the cell passively, possibly by reversal of an NH4+ uptake system. The data also indicate that in the wild type the bulk of NifA is inactivated by NifL during steady-state growth on dinitrogen.

In the model diazotrophs Azotobacter vinelandii and Klebsiella pneumoniae, nitrogen fixation is controlled at the transcriptional level by the regulatory proteins encoded by nifLA (for a review, see reference 12). NifA is a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator required for expression of the Mo nitrogenase system (A. vinelandii has two ancillary systems based on different metals), and NifL inhibits NifA function in response to ammonium, high oxygen concentrations, and reduced energy charge (7, 14, 30). In A. vinelandii the expression of nifLA is not under the control of the nitrogen regulatory system, NtrBC, as it is in K. pneumoniae, and NifL provides the only means of nitrogen regulation of the nif regulon (7). The NifL protein consists of two principal domains (13), an N-terminal domain, which binds flavin adenine dinucleotide and is presumed to sense the redox status of the cell, and a C-terminal domain, which binds adenosine nucleotides and probably interacts with NifA (14, 19, 32, 35, 36). To inhibit nif transcription, NifL binds to NifA, and normal regulation occurs only when the proteins are present in approximately stoichiometric amounts. The C-terminal domain of NifL resembles the histidine autokinase domain of the two-component regulatory proteins, particularly in the case of the A. vinelandii protein, which unlike K. pneumoniae NifL retains the His residue that is phosphorylated in conventional two-component systems. However, the histidine residue is not required for normal function of the A. vinelandii NifLA system (39) and the regulatory domain of NifA shows no sequence similarity to the receiver domains of two-component response regulators (4).

Mutations in A. vinelandii nifL, including a cassette insertion truncating the C-terminal domain of the protein and an in-frame deletion removing the N-terminal domain, have been reported to result in release of up to 15 mM ammonium into the medium in stationary phase (2, 7). In contrast, K. pneumoniae nifL mutants release very little ammonium, even when nifLA expression is released from nitrogen control mediated by NtrBC (2). Certain A. vinelandii nifL point mutants in which nitrogen control is disrupted do not release ammonium, suggesting that in these organisms NifL might control ammonium transport through a mechanism that does not involve NifA (39). The hypothesis has an additional attraction in that if such a mechanism involves a canonical two-component response regulator, it might be controlled by NifL, explaining the latter’s close resemblance to a two-component histidine autokinase. Ammonium transport is thought to have an important role in recovering fixed nitrogen lost as NH3 by diffusion through the cell membrane, a process termed cyclic retention (9), which if disrupted can result in ammonium release.

The release of ammonium by soil diazotrophs, particularly those associated with roots, is of considerable agronomic interest (see reference 10). We have investigated possible mechanisms underlying ammonium release in A. vinelandii and find no evidence for NifL control of an ammonium transport system. Ammonium release seems due rather to the passive loss of the ammonium which accumulates to high intracellular concentrations as a result of prolonged and enhanced nitrogenase expression, caused either by loss of NifL function or by upsetting the NifL/NifA ratio through overexpressing the activator. Up to 35 mM ammonium accumulated in the medium when nifA was expressed from the tac promoter.

In this paper, following earlier authors, the term ammonium will be used to include both ammoniacal species and NH3 and NH4+ will be used to distinguish the uncharged and cationic forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of chromosomal mutants.

The KIXX cassette, excised with SmaI from pUC4-KIXX (Pharmacia), and the omega cassette (34), cut with SmaI from pHP45Ω, were inserted into plasmids bearing the nifLA region, cut at restriction sites as indicated in Fig. 1 and elsewhere in the text, and filled in with Klenow DNA polymerase where necessary. Plasmid DNA was linearized and transformed into competent A. vinelandii as previously described (2), and colonies expressing the cassette resistance marker were screened for loss of the vector resistance marker. To confirm the structures and genetic homogeneity of the chromosomal lesions, the strains were further examined by DNA blotting and by PCR with various combinations of primers flanking the insertion site and within the cassettes.

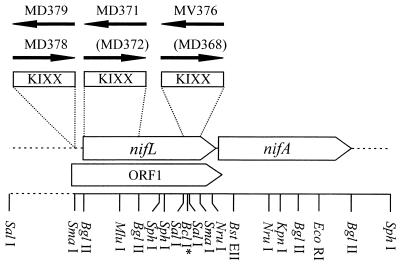

FIG. 1.

Map of the nifLA region of A. vinelandii showing restriction sites used for manipulations and the positions of KIXX inserts. The arrows marked with strain numbers indicate the directions of transcription of the KIXX promoters in the respective strains. Strain designations in parentheses designate constructs that could not be obtained in a genetically homogeneous form. The BclI site is not unique.

To obtain regulated overexpression of nifA by plasmid integration, a 664-bp NruI fragment carrying the NifA translation start site was cloned into the SmaI site of pDK6 (25), yielding pPW9709, which was transformed into competent A. vinelandii strains with selection for the vector marker. All transformants tested showed the expected dependence on IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for diazotrophy.

To construct the lacZ-tet cassette used in this study, a lacZ fragment was generated by PCR with the primers 5′-GCAAGATCTGATGACCATGATTACGGATTCA-3′ and 5′-TTTTAAGCTTATTTTTGACACCAGACCAAC-3′ and a tet fragment was generated with the primers 5′-TCATCGATAAGCTTTAATGC-3′ and 5′-CGGCAGATCTTCAGGTCGAGGTGGC-3′. The fragments were joined by cutting with HindIII, ligating, and extracting a fragment of the appropriate size from a gel. This fragment was then cleaved with BglII at its extremities and inserted into pBB385 at the BglII site containing the nifA stop codon, which, being preceded by A, also furnished the necessary initiation codon (underlined) for lacZ (ATGATCA). The tet promoter is not included in the cassette, so tet could be selected only following transformation into the A. vinelandii chromosome. Inserts in nifL and ptac-nifA cointegrates were then introduced into the nifA-lacZ-tet reporter strain.

Media, growth conditions, and assays.

A. vinelandii strains were grown aerobically at 30°C in Burk’s sucrose medium, with antibiotics when necessary, as described by Woodley and Drummond (39). Ammonium concentrations in the medium were measured by withdrawing a small sample, removing the cells by centrifugation, and assaying the supernatant by the indophenol method described by Bergersen (5). Intracellular concentrations were measured by weighing the cell pellet, resuspending it in a known volume of dilute acid, determining ammonium content by the indophenol method, and applying a correction factor to allow for the intercellular liquid, which was measured with Blue Dextran as described by Dilworth and Glenn (11). β-Galactosidase activities were measured as described by Miller (31). Nitrogenase activity in vivo was measured by the acetylene reduction method as described by Woodley and Drummond (39). Transcription of nifH was assessed by extracting RNAs from A. vinelandii cells with a Qiagen RNeasy kit, by loading a range of masses between 1 and 4 mg of RNA onto a nylon membrane with a Bio-Rad slot blot apparatus, and by hybridizing to a nifH DNA probe labelled with 32P with an Amersham RediPrime kit. Nitrogenase polypeptides were quantified by scanning laser densitometry of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels stained with Coomassie blue, considering UW136 cells grown on 15 mM ammonium as background.

RESULTS

Initially, the only NifL− strain in which release of ammonium could be confirmed was MV376 (2), in which the kanamycin resistance cassette KIXX is inserted between the SalI and SmaI sites (Fig. 1) thereby removing the C-terminal quarter of the native NifL sequence. A strain carrying a KIXX insert between the MluI site in nifL and the BstEII site in nifA, creating a functional ble′-′nifA protein fusion, is Nif+ but does not release ammonium. A third strain carrying an in-frame deletion removing the sensor domain of NifL earlier reported to release ammonium (MV440 [7]) could not be recovered from storage and could not be reconstructed by our earlier strategy of coselecting for the correction of a partial nifA deletion (39). A mutant with a more complete deletion of nifL between the BglII and BclI sites, removing residues Phe27 to Ile413, proved similarly unobtainable, for reasons we do not understand.

To eliminate the possibility that ammonium release in MV376 was associated with a secondary mutation rather than the nifL::KIXX insert itself, the strain was reconstructed de novo with pBB369 (Table 1) and the phenotype was confirmed. In so doing we found that a nifL mutant similar to MV376 but with the KIXX cassette in the opposite orientation was impossible to construct, as reported earlier (2). The frequency of transformation was much lower than in the reconstruction of MV376, and apparent transformants both grew more slowly and could be shown by DNA blotting to contain wild-type nifL as well as the mutant sequence. The KIXX cassette was also placed between the two BglII sites in the region encoding the sensor domain of NifL. The strain in which the aph promoter within KIXX directs transcription away from nifA, MD371, excreted ammonium, albeit to lower levels than MV376, while again the strain in which transcription from KIXX was in the same direction as nifA (MV372) could not be isolated free of wild-type nifL.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and A. vinelandii strains

| Plasmid(s) or strain | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pDK6 | pBR322-based lacIq ptac expression vector | 25 |

| pHP45Ω | Source of Strr Sper Ω cassette | 15 |

| pMD242 | General cloning vector | 16 |

| pTZ18, pTZ19 | General cloning vector | 28 |

| pUC4-KIXX | Source of aph-ble KIXX cassette | Pharmacia |

| pPW9609 | 4,463-bp SalI-KpnI fragment with two internal SalI sites carrying nifLA with a 591-bp BglII fragment deleted, cloned into pTZ19R | This work |

| pPW9709 | 664-bp NruI fragment carrying the 5′ end of nifA, cloned into the SmaI site of pDK6 | This work |

| pBB367 | 1,084-bp BglII-BstEII fragment polished and cloned into the NruI site of pMD242 | This work |

| pBB368 | 1.4-kb SmaI fragment (pUC4-KIXX) cloned into the SalI (polished) and SmaI sites of pBB367; KIXX+ | This work |

| pBB369 | Like pBB368 but KIXX− | This work |

| pBB370 | 1.4-kb SmaI fragment from pUC4-KIXX cloned into the BglII (polished) site of pPW9609; KIXX+ | This work |

| pBB371 | Like pBB370 but KIXX− | This work |

| pBB374 | 2.2-kb SmaI fragment from pHP45Ω cloned into the SalI (polished) and SmaI sites of pBB367; Ω+ | This work |

| pBB375 | Like pBB374; Ω− | This work |

| pBB378 | 2,589-bp SalI-MluI fragment carrying the 5′ end of nifL cloned into pMD242, with the pTZ18 linker between the EcoRI and SalI sites of the vector | This work |

| pBB379 | 1.4-kb SmaI fragment from pUC4-KIXX cloned into the SmaI site in ORF1 in pBB378 | This work |

| pBB380 | Like pBB379 but KIXX− | This work |

| pBB385 | 849-bp EcoRI-SphI fragment carrying the 3′ end of nifA cloned into pTZ18R | This work |

| pBB386 | lacZ-tet cassette inserted at the BglII site at the end of nifA in pBB385 | This work |

| A. vinelandii strains | ||

| UW136 | rif-1 (Nif+) | 6 |

| MV376 | rif-1 nifL1::KIXX | 2 |

| MV473 | rif-1 nifL (H305R) | 39 |

| MV479 | rif-1 nifL (H305P) | 39 |

| MV496 | rif-1 ptac-nifA | This work |

| MD367 | rif-1 nifL110::KIXX (= MV376) | This work |

| MD371 | rif-1 nifL112::KIXX (Fig. 1) | This work |

| MD378 | rif-1 nifL118::KIXX (Fig. 1) | This work |

| MD378 | rif-1 nifL119::KIXX (Fig. 1) | This work |

| UW136.1 | rif-1 nifA-lacZ-tet | This work |

| MV376.1 | rif-1 nifL1::KIXX nifA-lacZ-tet | This work |

| MD371.1 | rif-1 nifL112::KIXX nifA-lacZ-tet | This work |

| MV496.1 | rif-1 ptac-nifA-lacZ-tet | This work |

Superscript + and − indicate the orientations of cassette insertions, with + indicating where the cassette is transcribed in the direction of nifLA and − indicating the reverse orientation.

The apparent lethality of certain nifL mutants and the variation of ammonium accumulation with position of KIXX inserts in nifL were difficult to explain in terms of NifL function alone. We therefore considered the possible involvement of genes upstream from nifL and transcribed divergently from it which encode redox proteins thought to be involved in electron transport to nitrogenase (38). These genes might be overexpressed as a result of transcription from the aph promoter within KIXX, and this might result in fixation of more nitrogen than is required for growth, because electron transport can limit nitrogen fixation (26). We also noted the existence of a long open reading frame (ORF1) (Fig. 1) coextensive with nifL but displaced −1 bp, which would be disrupted by nifL::KIXX mutations but possibly not by point mutations that impair nifL function such as those reported earlier (39). The stop codon of ORF1 overlaps the start codon of nifA in a manner suggestive of genes that are translationally coupled, but no homologue of ORF1 could be found in existing databases and its codon usage was poor. The KIXX cassette was inserted in both orientations without difficulty at the SmaI site upstream from nifL, disrupting ORF1 but not nifL or its promoter. Mutant strains carrying inserts at this site are Nif+ and did not excrete ammonium to an appreciable extent (Fig. 2), irrespective of the orientation of KIXX. This result shows that neither ORF1 nor overexpression of the genes upstream from nifL was responsible for the ammonium release.

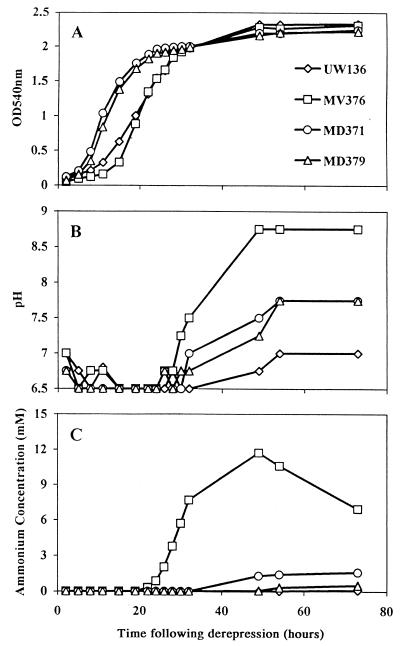

FIG. 2.

Optical densities (OD) (A), pHs of the medium (B), and ammonium concentrations in the medium (C) for various A. vinelandii strains as a function of time following derepression.

While we were characterizing MV376, MD371, and MD379, it became clear that measuring accumulated ammonium in the medium at a fixed point after nitrogen shift-down did not give a reproducible measure of a strain’s ability to release ammonium. The time courses of ammonium accumulation were therefore measured for a number of strains and correlated with growth of the cultures and the increase in pH of the medium resulting from ammonium release. Quantitative differences in the results obtained were often twofold between experiments and were occasionally greater, but the general pattern shown in Fig. 2 was always observed. After varied lag times the different strains grew at similar rates and reached comparable final densities, but the timing and extents of ammonium release varied. MV376 consistently produced more ammonium than MD371, the difference being particularly marked in the experimental results shown in Fig. 2. The disappearance of ammonium from the medium after prolonged culture of MV376 (Fig. 2) was due to loss of gaseous NH3, which could be quantitatively recovered by pumping air through the cultures and bubbling the exhaust gas through an acid trap. The pH of all the cultures fell half a unit in early log phase and remained at 6.5 until stationary phase, during which it rose roughly in proportion to the quantity of ammonium released into the medium. After 5 days, ammonium was detectable in the medium even of the wild-type strains CA and UW136, as previously observed (8), but all the nifL::KIXX mutants produced more.

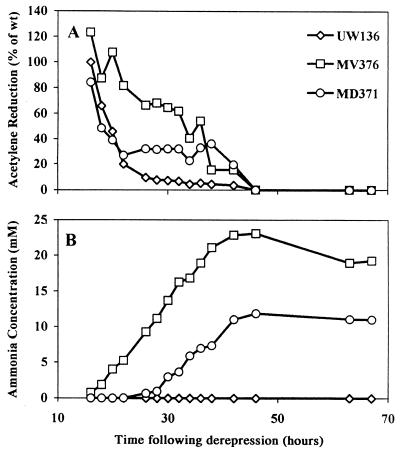

We considered two explanations for the phenotypic difference between MV376 and MD371. MV376 retains the coding sequence for the sensor domain of NifL and the subdomain TL (33). It may therefore produce a truncated form of NifL which may retain some function, for example, actively enhancing ammonium release while exhibiting the null phenotype with respect to inhibition of NifA activity. In this case strains releasing ammonium would contain normal levels of nitrogenase and reduced intracellular ammonium concentrations. Alternatively, transcription of nifA may vary between different mutants, which, in conjunction with loss of NifL function, may result in different levels of nitrogenase overexpression and hence ammonium accumulation. In this case strains releasing ammonium would contain raised levels of both nitrogenase and intracellular ammonium. To distinguish between these possibilities, the time courses of acetylene reduction and ammonium release were measured for a variety of nifL mutant, well into stationary phase. In the experiment shown in Fig. 3, ammonium release is associated with elevated and/or prolonged levels of nitrogenase activity. In the wild type, UW136, acetylene reduction fell to 10% of its maximal value in late log phase, whereas in MD371, it persisted at high levels up to 40 h, although not exceeding the levels of the wild type in log phase. MV376, on the other hand, reduced acetylene much more actively than the wild type in log phase, but the level of reduction fell rather sharply around 40 h. One culture of MV376 continued to excrete longer than the other, the final ammonium concentration exceeding 20 mM, which appeared deleterious to cell growth. These data indicate that failure to control nitrogenase synthesis, rather than a disruption of ammonium transport, is the probable cause of ammonium release.

FIG. 3.

Relative nitrogenase activities (A) and ammonium concentrations in the medium (B) for the wild type (wt) and nifL::KIXX mutants.

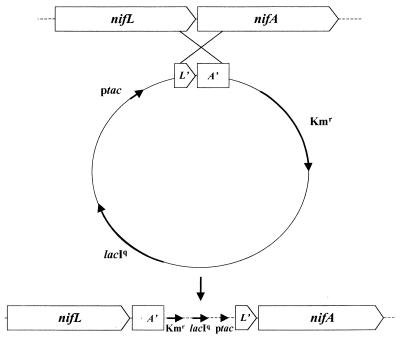

To establish whether a lesion of nifL was necessary or sufficient for ammonium release, we inserted the omega cassette into the chromosome at the same position as that occupied by KIXX in MV376. Unlike KIXX, the omega cassette is strongly polar in A. vinelandii, and transcription originating within it does not extend into flanking sequences. Strains bearing nifL::Ω were Nif−, presumably because nifA was not expressed. To obtain nifA expression, the strategy outlined in Fig. 4 was used. A short fragment including the nifA translation start site was cloned downstream from the tac promoter in the pBR322-based expression vector pDK6, which cannot replicate in A. vinelandii. The construct was transformed into A. vinelandii and integrated into the chromosome by selecting for the plasmid-borne drug marker, the single recombination event generating a short duplication of nifA with the tac promoter adjacent to the intact nifA gene. Because pDK6 also carries lacIq, nifA could then be regulated at the transcriptional level. Using a nifA-lacZ fusion we showed that a 100-fold induction of nifA transcription could be obtained with 200 μM IPTG (data not shown). In the absence of IPTG, ptac-nifA strains were Nif−, but in its presence they could grow diazotrophically and released ammonium whether or not omega was inserted in nifL. In one experiment, MV496, the ptac-nifA strain lacking the nifL insert, released the highest level of ammonium recorded in this work, its concentration in the medium exceeding 35 mM. This showed that a lesion in nifL was not necessary for ammonium release.

FIG. 4.

Strategy for obtaining regulated overexpression of nifA from the chromosome in A. vinelandii.

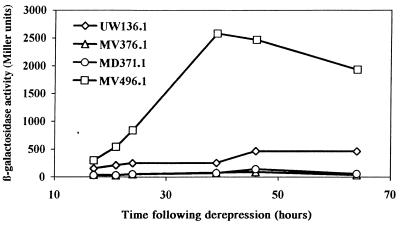

Our results did not, however, establish that nifA was overexpressed in the nifL::KIXX mutants, and indeed one hardly expects this to be so since in the nifL::KIXX mutants the relatively strong aph promoter points away from nifA and interruption of the nifL sequence would if anything reduce expression of the downstream gene. Reporter strains were constructed to examine nifA expression. Although not ς54 dependent, the nifLA promoter region contains a ς54 recognition sequence close to the transcription start site and has NifA binding sites further upstream, suggesting that NifA might have some autoregulatory function (7). The nifA coding sequence was therefore left intact and coupled to lacZ by inserting a specially constructed lacZ-tet cassette at the BglII site which fortuitously overlaps the nifA stop codon. As there is evidence for posttranscriptional regulation of nifA expression in some systems (20), the fusion was designed to make reporter expression dependent on nifA translation as well as transcription by overlapping the initiation codon of lacZ with the nifA stop codon. The data obtained with this reporter showed that nifA expression was reduced at least threefold in nifL::KIXX mutants with respect to the level of expression in the wild type (Fig. 5), whereas transcription from the tac promoter greatly enhanced nifA expression, as expected. NifA expressed from the chromosome could not be reliably quantified by protein blotting, but the variation in levels of nifA transcription is presumably reflected in the intracellular concentrations of the activator. It thus appears that the reduced levels of NifA present in the nifL::KIXX mutants result in higher levels of nif expression than in UW136, implying that most of the NifA protein in the wild type is inhibited by NifL even in derepressing conditions.

FIG. 5.

Activities of a nifA-lacZ reporter in various nif regulatory mutants. Expression of nifA in MV496.1 was induced with 200 μM IPTG at the start of derepression.

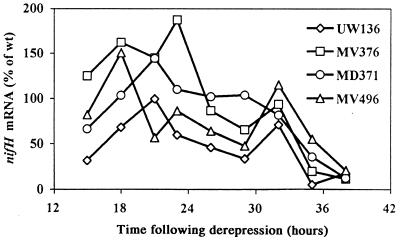

To confirm that the effects of the regulatory mutations were indeed on nif transcription rather than some other aspect of nitrogenase biosynthesis or activity, the relative levels of nifH mRNA were measured as a function of time in wild-type and mutant strains by hybridization to a 32P-labelled probe and quantification with a phosphorimager. The results (Fig. 6) show that in all the strains excreting ammonium, nifH mRNA was about twofold more abundant than in the wild type, consistent with our interpretation that the common result of the regulatory mutation was enhanced transcription of the nif regulon.

FIG. 6.

Relative levels of nifH mRNAs in various A. vinelandii strains. Expression of nifA in MV496 was induced with 200 μM IPTG at the start of derepression. wt, wild type.

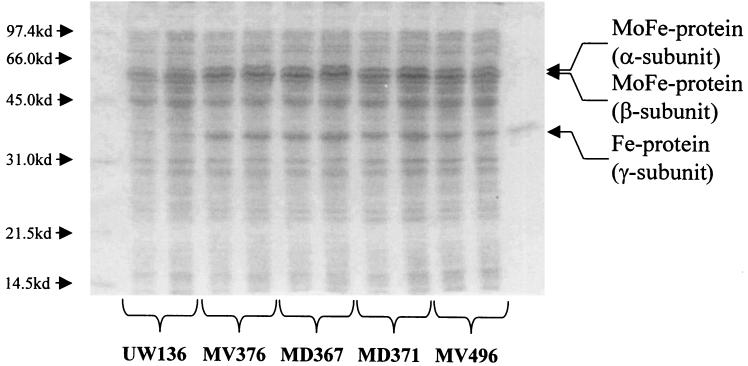

To establish more firmly the link between enhanced levels of nif mRNA and acetylene reduction, the abundance of nitrogenase polypeptides was measured densitometrically, also as a function of time. This showed that in the regulatory mutants, nitrogenase levels were also raised at least twofold (Fig. 7). The enhanced acetylene reduction observed in nifL mutants can thus be attributed to an increase in the intracellular levels of nitrogenase rather than to any modulation of its activity, though our data do not exclude the latter possibility.

FIG. 7.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel showing overexpression of nitrogenase polypeptides in various A. vinelandii strains 30 h after derepression. Duplicated lanes represent separate cultures of the same strain. The lane on the extreme right contains purified Fe protein. Expression of nifA in MV496 was induced with 200 μM IPTG at the start of derepression.

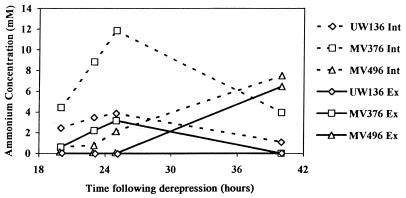

If ammonia release is a result of enhanced nitrogen fixation, then concentrations of intracellular ammonium in the nif regulatory mutants should exceed those in the wild type. Intracellular ammonium was therefore measured as a function of time. To establish whether ammonium leaked from the cell, or whether it was pumped out, intracellular and extracellular concentrations were compared. The data in Fig. 8 indicate that for a given strain, intracellular ammonium is more concentrated than that in the medium at any particular point and that ammonium release by regulatory mutants occurs only when intracellular concentrations exceed those found in the wild type.

FIG. 8.

Intracellular (Int) and extracellular (Ex) ammonium concentrations at various times following derepression. Expression of nifA in MV496 was induced with 200 μM IPTG at the start of derepression.

All the data presented above indicate that ammonium release is due to disruption of NifA-mediated control. However, we earlier reported that the A. vinelandii nifL point mutants MV473 and MV479, containing the substitutions His305Arg and His305Pro, lack nif regulation but do not release ammonium (39). To explore this apparent contradiction, we measured nif expression and ammonium release in MV473 and MV479 cultured for longer periods than in the earlier work. We confirmed that they do not release ammonium but found that in these mutants NifL activity is impaired rather than eliminated. As originally reported, 6 h after addition of 15 mM ammonium to fixing cultures, the mutants do not differ significantly from the nifL::KIXX mutant in levels of nitrogenase activity but after 18 h, nitrogenase activity falls to less than 5% of fully derepressed levels. This degree of repression is presumably sufficient to prevent the accumulation of intracellular ammonium.

DISCUSSION

Our objective in undertaking this work was to establish the basis of ammonium release in nifL mutants of A. vinelandii. K. pneumoniae nifL mutants release comparatively little ammonium, but the clues offered by differences between K. pneumoniae and A. vinelandii nifL sequences proved misleading. Although A. vinelandii NifL closely resembles a histidine autokinase, we found no evidence for a conventional response regulator that might control ammonium release independently of NifA. Similarly, neither the open reading frame overlapping A. vinelandii nifL nor upstream genes could be implicated in ammonium release, which may now be persuasively attributed to unregulated overexpression of nif genes resulting from disruption of the NifLA system. Such overexpression results in elevated levels of nitrogenase and high concentrations of intracellular ammonium, which is lost from the cell.

The apparent lethality of mutants with in-frame deletions of nifL and of nifL::KIXX mutants in which the KIXX promoter points downstream remains unexplained. It is tempting to speculate that in these strains NifA activity is so high that lethal levels of nitrogenase are produced, which would explain why a nifL::KIXX insert in this orientation can be obtained in a nifH-lacZ background (MV380 [2]). However, NifA activity in this strain is lower than in our nifL::Ω ptac-nifA construct, which is inconsistent with this interpretation.

Disruption of the NifLA system can occur in two ways, by impairing or eliminating NifL and by overexpressing NifA. In K. pneumoniae, NifA overexpression has long been known to eliminate regulation by NifL, an important early piece of evidence for the involvement of protein-protein binding in the mechanism of signal transduction in the NifLA couple. Our data clearly indicate that this is also true for A. vinelandii. The raised levels of nif mRNA in the deregulated cells suggest that nif transcription is normally limited by the availability of transcriptionally active NifA. Thus, during diazotrophic growth, the nifH promoter is not saturated with activator. We have not determined whether this is true for other nif promoters or which, if any, of the various nif products limit nitrogen fixation; in an efficiently coordinated system one would not expect any single product to be limiting.

In nifL::KIXX mutants, expression of nifA is much lower than in the wild type whereas NifA activity is higher. These findings suggest that in the wild type the bulk of NifA is inactivated by NifL to an extent which may be roughly quantified. The activity of a nifA-lacZ fusion was reduced about fivefold in a nifL::KIXX mutant, and provided that degradation of both β-galactosidase and NifA follow first-order kinetics, concentrations of the activator will also be about fivefold lower. The concentration of transcriptionally active NifA must be at last twofold higher to account for the doubling of nifH transcription, suggesting that a minimum of 90% of NifA in the wild type is inactivated by NifL during diazotrophic growth. This inactivation may be because intracellular levels of ammonium sufficient to inhibit nitrogenase expression are produced by fixation itself. Such product inhibition appears to occur in K. pneumoniae and Rhodopseudomonas palustris, because depriving nitrogen-starved cultures of dinitrogen raises nitrogenase levels two- to eightfold in these organisms (1, 18). Being a strict aerobe, Azotobacter is unlikely to experience limiting dinitrogen under natural conditions, but the maximal, uninhibited capacity for nitrogenase biosynthesis may confer a selective advantage when a source of fixed nitrogen is suddenly removed, resulting in very low levels of intracellular ammonium. Under these circumstances the constitutive expression of nifLA would also be an advantage since it would remove the lag necessary for activator expression. Thus, the feature most diagnostic of A. vinelandii’s capacity for ammonium release compared to that of K. pneumoniae is probably rapid derepression (18) rather than any particular detail of its nif regulatory mechanism.

Intracellular ammonium concentrations were 1 to 3 mM in the wild type, in good agreement with the previously published value of 2.9 mM (17). This concentration is fivefold more than that measured in K. pneumoniae, and because the intracellular pH of A. vinelandii is also higher, favoring deprotonation (pH 7.5 versus pH 8.1 [21, 27]) the intracellular concentration of NH3 would be about 20 times greater in A. vinelandii than in K. pneumoniae during diazotrophy. If the cell membrane is as permeable to NH3 as was postulated by Kleiner (23), the energetic cost of maintaining this ammonium concentration by cyclic retention would be three to five times greater than that required for its fixation, and it would be unnecessary, given the high affinity of glutamine synthetase for ammonium. Lower estimates of the permeability coefficient may therefore be more realistic (22, 37).

Strains releasing ammonium contained appreciably higher intracellular ammonium concentrations than the wild type, and these concentrations invariably exceeded that of extracellular ammonium, suggesting that loss of ammonium from the cell is passive; indeed it is difficult to see why a free-living soil bacterium should possess a system for the active export of ammonium. The highest extracellular concentration measured was 35 mM, and although correspondingly high intracellular levels were not measured in this experiment, they have precedents in other systems. Rhizobium leguminosarum growing on histidine as a carbon source can accumulate up to 90 mM intracellular ammonium without effect on growth or respiration (11).

When the medium becomes alkaline, passive loss probably requires diffusion of NH4+ as well as NH3, because, assuming intracellular pH is controlled, extremely high intracellular ammonium concentrations are required to give the NH3 concentrations necessary for ammonium release. For example, 35 mM ammonium in the medium at pH 8.7 would equilibrate with 140 mM intracellular ammonium at an intracellular pH of 8.1 if the membrane remains impermeable to the cation. On these grounds, it seems likely that ammonia is lost from the cell as NH4+, running a specific carrier backwards exergonically. Active transport of NH4+ into the A. vinelandii cell has been described by several groups (3, 17, 24, 27). The transporter may be encoded by the ammonium transport gene amtB (29), but in Salmonella typhimurium there is some evidence that the amtB product transports NH3 and does not concentrate it (37). These observations may be reconciled if more than one ammonium transport system exists in A. vinelandii, as some data suggest (17, 24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ray Dixon, Mike Merrick, Christina Kennedy, and Gavin Thomas for criticism of the manuscript and June Dye and Debbie Darling for typing it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arp D J, Zumft W G. Overproduction of nitrogenase by nitrogen-limited cultures of Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1322–1330. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1322-1330.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bali A, Blanco G, Hill S, Kennedy C. Excretion of ammonium by a nifL mutant of Azotobacter vinelandii fixing nitrogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1711–1718. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1711-1718.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes E M, Jr, Zimniak P. Transport of ammonium and methylammonium ions by Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:512–516. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.512-516.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett L T, Cannon F C, Dean D. Nucleotide sequence and mutagenesis of the nifA gene from Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergersen F J. Methods for evaluating biological nitrogen fixation. London, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop P E, Brill W J. Genetic analysis of Azotobacter vinelandii mutant strains unable to fix nitrogen. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:954–956. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.954-956.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco G, Drummond M, Kennedy C, Woodley P. Sequence and molecular analysis of the nifL gene of Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:869–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burk D, Burris R H. Biochemical nitrogen fixation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1941;10:587–618. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castorph H, Kleiner D. Some properties of Klebsiella pneumoniae ammonium transport negative mutant (Amt) Arch Microbiol. 1984;139:245–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colnaghi R, Green A, Luhong H, Rudnick P, Kennedy C. Strategies for increased ammonium production in free-living or plant associated nitrogen fixing bacteria. Plant Soil. 1997;194:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilworth M J, Glenn R. Movements of ammonia in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive NifL-NifA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in γ-proteobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond M, Whitty P, Wootton J. Sequence and domain relationships of ntrC and nifA from Klebsiella pneumoniae: homologies to other regulatory proteins. EMBO J. 1986;5:441–447. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eydmann T, Söderbäck E, Jones T, Hill S, Austin S, Dixon R. Transcriptional activation of the nitrogenase promoter in vitro: adenosine nucleotides are required for inhibition of NifA activity by NifL. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1186–1195. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1186-1195.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geissler S, Drummond M H. A counterselectable pACYC184-based lacZα-complementing plasmid vector with novel multiple cloning sites; construction of chromosomal deletions in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gene. 1993;136:253–255. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90474-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon J K, Moore R A. Ammonium and methylammonium transport by the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:435–442. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.435-442.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill S, Kavanagh E, Munn J A, Kahindi J, Campbell F, Yates M G, D’Mello R, Poole R K. Physiology of N2 fixation relating to N, O2, H2 status in free-living heterotrophs. In: Hegazi N A, Fayez M, Monib M, editors. Nitrogen fixation with non-legumes. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press; 1994. pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill S, Austin S, Eydmann T, Jones T, Dixon R. Azotobacter vinelandii NifL is a flavoprotein that modulates transcriptional activation of nitrogen-fixation genes via a redox-sensitive switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2143–2148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski P A, Desnoues N, Elmerich C. The expression of nifA in Azorhizobium caulinodans requires a gene product homologous to Escherichia coli HF-I, an RNA-binding protein involved in the replication of phage Qβ RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4663–4667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashket E R. Effects of aerobiosis and nitrogen sources on the proton motive force in growing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae cells. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:377–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.377-384.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiner D. The transport of NH3 and NH4+ across biological membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;639:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(81)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleiner D. Energy expenditure for cyclic retention of NH3/NH4+ during N2 fixation by Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEBS Lett. 1985;187:237–239. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleiner D. Ammonium uptake by nitrogen fixing bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1975;104:163–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00447319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleiner D, Paul W, Merrick M J. Construction of multicopy expression vectors for regulated overproduction of proteins in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other enteric bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1779–1784. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klugkist J, Haaker H, Wassink H, Veeger C. The catalytic activity of nitrogenase in intact Azotobacter vinelandii cells. Eur J Biochem. 1985;146:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laane C, Krone W, Kronings W, Haaker H, Veeger C. Short term effect of ammonium chloride on nitrogen fixation by Azotobacter vinelandii and by bacteroids of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Eur J Biochem. 1980;103:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mead D A, Szczesna-Scorupa E, Kemper B. Single stranded DNA “blue” promoter plasmids: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1:67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meletzus D, Rudnick P, Doetsch N, Green A, Kennedy C. Characterization of glnK-amtB operon of Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3260–3264. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3260-3264.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrick M, Hill S, Hennecke H, Hahn M, Dixon R, Kennedy C. Repressor properties of the nifL gene product of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;185:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narberhaus F, Lee H-S, Schmitz R A, He L, Kustu S. The C-terminal domain of NifL is sufficient to inhibit NifA activity. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5078–5087. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5078-5087.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacterial signalling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prentki P, Krisch H K. In vitro mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitz R A. NifL of Klebsiella pneumoniae carries an N-terminally bound FAD cofactor, which is not directly required for the inhibitory function of NifL. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Söderbäck E, Reyes-Ramirez F, Eydmann T, Austin S, Hill S, Dixon R. The redox- and fixed nitrogen-responsive regulatory protein, NifL, from Azotobacter vinelandii is comprised of discrete flavin and nucleotide-binding domains. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:179–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soupène E, Luhong H, Yan D, Kustu S. Ammonia acquisition in enteric bacteria: physiological role of the ammonium/methylammonium transport B (AmtB) protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7030–7034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodley, P. Personal communication.

- 39.Woodley P, Drummond M. Redundancy of the conserved His residue in Azotobacter vinelandii NifL, a histidine autokinase homologue which regulates transcription of nitrogen fixation genes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]