Abstract

Autistic adults are at high risk for co-occurring mental health problems and need access to effective and appropriate mental health treatment. However, the relative effectiveness or acceptability of specific mental health strategies among autistic adults has not been previously examined. The current study sought to gain a deeper understanding of autistic adults’ experiences and preferences regarding mental health strategies using a mixed methods approach. Autistic adults (n = 303, ages 21–77) completed online surveys and open-ended questions about their mental health and therapy experiences. Most (88.8%) had participated in therapy, with cognitive approaches being the most common. Regarding overall therapy experiences, qualitative analyses revealed 4 primary themes and 9 subthemes. Therapist acceptance and understanding were seen as critical for therapy success and many participants felt that therapy was helpful for personal growth. However, many participants found that talking in session was challenging and noted that aspects of the session format affected their ability to engage in therapy. Regarding specific strategies, 4 cross-cutting themes and 8 strategy-specific subthemes were identified. A variety of strategies were seen as helpful for reducing anxiety and improving mood. However, autistic adults reported trouble generalizing strategies to daily life and found some techniques to be difficult to implement due, in part, to their unique autism-related needs. As the first study of its kind, the results underscore the importance of establishing a safe and accepting therapeutic relationship, providing accommodations to support communication needs, and considering individual differences and preferences when selecting mental health strategies for autistic clients.

Keywords: autism, adults, psychotherapy, mental health, qualitative research, therapy

Approximately 2.2% of adults in the US have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Dietz et al., 2020), and are in need of high-quality services to support their health and well-being. Among these needs, mental health has been identified as a particularly important issue (Benevides, Shore, Palmer, et al., 2020; Crane et al., 2019; Gotham, Marvin, et al., 2015). Autistic adults are at much higher risk for co-occurring mental health conditions than the general population (Croen et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2019; Rydzewska et al., 2018). Meta-analytic results indicate that approximately 54% of autistic adults meet criteria for a co-occurring psychiatric disorder based on DSM or ICD diagnostic classifications (Lugo-Marín et al., 2019) and that lifetime prevalence of anxiety (42%) and depression (37%) are remarkably high (Hollocks et al., 2019). Recent large-scale caregiver- and self-report survey studies have found lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders ranging from 72% among dependent autistic adults (Fombonne et al., 2020) to 87% among independent autistic adults (Jadav & Bal, 2022), with lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders ranging from 41 to 66% and affective disorders ranging from to 28 to 58% (Fombonne et al., 2020; Jadav & Bal, 2022). Depression and anxiety have significant negative effects on well-being, quality of life, and day-to-day functioning (Gotham, Brunwasser, et al., 2015; Mason et al., 2018; Mazurek, 2014; Oakley et al., 2021), leading to increased risk for suicidality among autistic adults (Cassidy et al., 2018; Hedley et al., 2018; Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al., 2021), and underscoring the urgent need for effective and appropriate outpatient treatment.

Outpatient psychotherapy is a first-line treatment for depression and anxiety in the general population (Carpenter et al., 2018; Cuijpers et al., 2008, 2016; Hofmann et al., 2010, 2012), and many autistic adults also report a need and desire for psychotherapy (Baldwin & Costley, 2016; Crane et al., 2019). Despite growing interest in this topic in recent years, research on mental health interventions for autistic adults remains relatively sparse. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) have been the most widely studied mental health interventions in autism (Benevides, Shore, Andresen, et al., 2020; Spain et al., 2015; White et al., 2018). However, the comparative effectiveness of specific mental health strategies or individual predictors of treatment response among autistic adults have not been previously investigated. This is an important avenue for future research because these factors could directly inform personalized treatment and clinician decision-making.

CBT and MBT are both multi-component approaches involving different combinations of more specific treatment strategies (Hayes & Hofmann, 2017). Cognitive strategies focus on identifying and restructuring maladaptive thoughts (Beck & Haigh, 2014; Hofmann et al., 2013). By contrast, behavioral strategies focus on changing unhelpful patterns of behavior. For treatment of anxiety, the primary behavioral strategy is exposure, which involves repeatedly approaching and engaging with anxiety-provoking situations and stimuli to prevent avoidance and reduce anxiety over time (Abramowitz et al., 2019). The primary behavioral strategy for treating depression is behavioral activation, which focuses on enhancing mood through increased engagement in rewarding activities (Lejuez et al., 2001). In addition, CBT for anxiety often includes specific relaxation strategies that aim to reduce physiological arousal. These include deep breathing (slow paced diaphragmatic breathing) (Chen et al., 2017), progressive muscle relaxation (PMR; progressively tensing and releasing various muscle groups) (Bernstein & Borkovec, 1973), and guided imagery (imagining a pleasant, relaxing scene) (Daake & Gueldner, 1989). Finally, mindful meditation is a key strategy involved in MBT and multicomponent treatments such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes, 2004) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) (Kliem et al., 2010; Linehan et al., 2015). This strategy involves developing non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of present-moment experiences, including moment-to-moment sensations, thoughts, and feelings (Baer, 2003).

Surprisingly, previous studies have not examined the relative effectiveness of specific mental health strategies for autistic adults, and few studies have focused on the direct perspectives of autistic adults themselves. It is likely that the unique communication and information processing needs of autistic adults may make some of these strategies difficult to implement. For example, cognitive strategies require active monitoring of thoughts and feelings, which may be difficult for autistic adults who have difficulty identifying and describing emotions (Kinnaird et al., 2019). Other strategies may require sustained attention, focus, and out-of-session practice to maximize effectiveness, which may be challenging for autistic adults who often have co-occurring executive functioning difficulties (Johnston et al., 2019).

Understanding the perspectives of autistic adults is vitally important for gaining insight into the acceptability, feasibility, and relative helpfulness of specific mental health strategies. Brede and colleagues (2022) conducted a systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis of qualitative studies focused on autistic adults’ experiences accessing mental healthcare. Most studies had a relatively broad focus on services, with some mention of mental health. The results revealed many barriers to accessing care. Themes relevant to perceived helpfulness of mental health services also emerged, including clinician attitudes about autism, the importance of flexibility, and needs for individualizing treatment. The authors noted a lack of research focused on autistic adults’ experiences with specific mental health interventions and pointed to a need for future research on this topic (Brede et al., 2022).

The current study was designed to fill this gap by exploring the perspectives of autistic adults regarding specific mental health interventions. A convergent mixed methods design was selected to enable a quantitative understanding of relative helpfulness of a range of mental health strategies, as well as deeper insights into individual differences and aspects of therapeutic strategies that made them particularly helpful or challenging. As the first study on the topic, our approach was largely exploratory and was designed to be descriptive and informative for future clinical research and practice.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The study included a nationally representative United States sample of 303 autistic adults who were recruited through the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) Research Match process. SPARK is a large-scale study aiming to recruit, engage and retain a community of 50,000 individuals with ASD and their family members. SPARK participants enroll online, provide saliva samples for genetic analysis, and agree to be contacted for future research opportunities. Eligibility for the current study included being an autistic adult aged 21 years or older, being independent (not having a legal guardian), and having a previous professional diagnosis of ASD. Participants were recruited by email through the SPARK Research Match process, completed all measures online, and were compensated $15 for participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia; all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Measures

Participants completed a 14-item Demographic Survey. Items included age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, relationship status, living arrangements, and employment.

Autism characteristics were assessed using the Autism Spectrum Quotient–Short (AQ-Short) (Hoekstra et al., 2011), which is an abridged 28-item version of the original 50-item AQ (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001), a continuous self-report measure of autism spectrum traits in adults. Using the full range of item scoring (from 1 = definitely agree, to 4 = definitely disagree), total possible scores range from 28 to 112, with higher scores indicating greater autism traits. A clinical cutoff score of > 65 has sensitivity of .97 and specificity of .82 for ASD (Hoekstra et al., 2011).

Participants also completed a 20-item Mental Health and Therapy Experiences Survey designed for the current study. Items assessed prior mental health diagnoses, previous therapy or counseling experiences, therapist(s)’s knowledge of autism, and perceived importance of therapists’ knowledge of autism. Participants with prior therapy experience also answered a series of questions about specific therapeutic strategies (i.e., cognitive strategies, exposure, behavioral activation, deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery/visualization, and mindfulness meditation). If their previous therapy had included a specific strategy, follow-up questions included: “How helpful were these strategies?” (1 = not at all helpful, to 5 = very helpful), “How easy were these strategies to use? (1 = very difficult, to 5 = very easy), and “Please tell us more about how well these strategies worked for you” (open-ended). The survey concluded with two open-ended questions about overall therapy experiences: “What have you found to be most helpful in therapy?” and “What have you found to be least helpful in therapy?”

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize key variables. Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine potential relations among demographic variables and perceived helpfulness and ease of use of mental health strategies. Non-parametric methods were utilized due to the ordinal nature of the mental health strategy data. Spearman-rank correlations were calculated for age and highest level of education, Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White versus other), and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were calculated for gender identity and highest level of education. Spearman-rank correlations were calculated to examine the strength of association between autism characteristics and perceived helpfulness and ease of use of specific mental health strategies.

Open-ended responses to questions about mental health experiences were analyzed using a data-driven qualitative content analysis approach (Bengtsson, 2016; Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Flick, 2013; Schreier, 2012). In the first stage of the process, three members of the analytic team (MM, JP, and SB) familiarized themselves with the data by independently reading all responses and developing initial impressions of key topics and patterns. MM then developed a preliminary framework to assign meaning units (i.e., codes) to text using an iterative open coding process in which codes were generated inductively. JP and SB independently reviewed the data again and compared their impressions with this preliminary list of code categories. Through a series of regular meetings and discussion, MM, JP and SB worked together to iteratively refine these codes and develop an initial coding framework. Next, JP and SB independently coded all responses according to this structure and met to identify discrepancies. Discrepancies were further discussed among a larger group (MM, JP, SB, and ES) to ensure consistency, come to a better understanding of the codes, and modify the coding structure as needed. The team came to consensus on all codes and achieved 100% agreement across responses. Codes were then consolidated into conceptually similar categories through data visualization, examination of code frequency, and consideration of meaningful connections between codes. This resulted in development of a final set of broad conceptual themes and subthemes that reflect key concepts and insights.

Results

Participants ranged in age from 21 to 77 years (M = 37.1, SD = 12.0). AQ-Short scores ranged from 52 to 108 (M = 82.2, SD = 11.3), and age at autism diagnosis ranged from 2 to 72 (M = 25.7, SD = 15.5). The sample was largely White (85.8%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (94.7%) but was diverse in terms of gender identity and sexual orientation, with 19.1% identifying as transgender, non-binary, or other non-cisgender identity, and 39.3% identifying as having a non-heterosexual orientation. See Table 1 for sample characteristics. Regarding autism-specific terminology preferences, 40.9% preferred identity-first language (“autistic person”), 28.4% preferred “person on the autism spectrum,” 17.6% preferred “person with autism,” and 13.2% preferred other terms.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Number (Percent) | |

|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |

| Cisgender Woman | 150 (49.5%) |

| Cisgender Man | 95 (31.4%) |

| Transgender Woman | 6 (2.0%) |

| Transgender Man | 12 (4.0%) |

| Non-binary/non-conforming | 35 (11.6%) |

| Other | 5 (1.7%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Straight | 184 (60.7%) |

| Gay or lesbian | 20 (6.6%) |

| Bisexual or pansexual | 59 (19.5%) |

| Asexual | 24 (7.9%) |

| Other | 16 (5.3%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (5.3%) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.3%) |

| Asian | 5 (1.7%) |

| Black or African American | 15 (5%) |

| White or Caucasian | 260 (85.8%) |

| Multiracial | 21 (6.9%) |

| Residence | |

| Live alone | 79 (26.1%) |

| Live with parent(s) | 81 (26.7%) |

| Live with romantic partner or spouse | 112 (37.0%) |

| Live with roommate(s) | 30 (9.9%) |

| Other | 33 (10.9%) |

| Level of Education | |

| Less than High School | 7 (2.2%) |

| High School Graduate or GED | 77 (25.4%) |

| Associate or Technical Degree | 49 (16.2%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 103 (34.0%) |

| Master’s Degree | 55 (18.2% |

| Doctoral Degree | 12 (4.0%) |

| Employment | |

| Full Time Job | 119 (39.3%) |

| Part-Time Job, Student | 16 (5.3%) |

| Part-Time Job, Not Student | 47 (15.5%) |

| Not Employed, Student | 24 (7.9%) |

| Not Employed, Not Student | 97 (32%) |

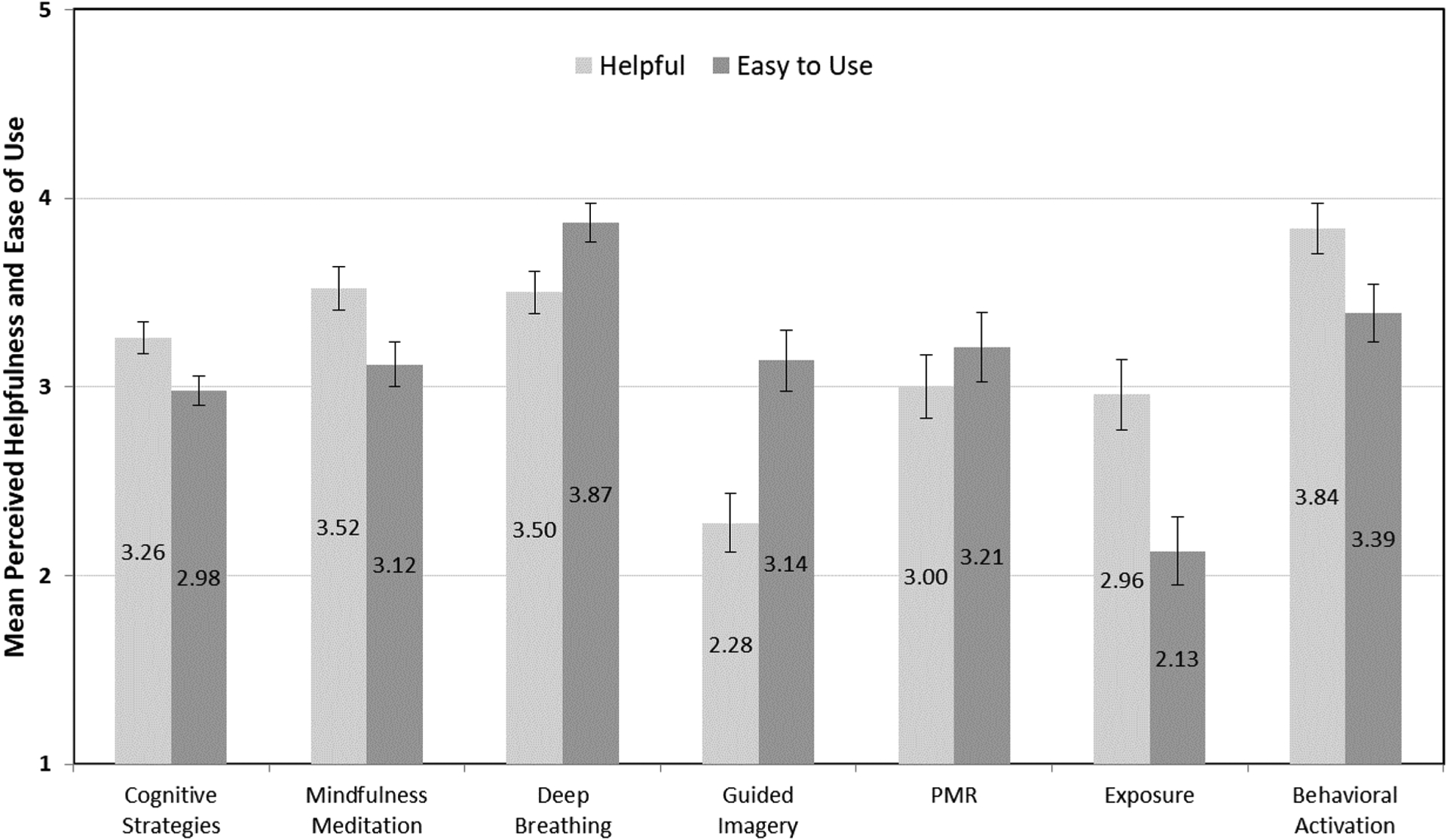

See Table 2 for mental health history. Most (89.8%) had been previously diagnosed with a co-occurring mental health condition, and the majority (88.8%) had previously participated in therapy. Notably, most (66.5%) participants felt that it was “very important” for their therapist to know a lot about autism. See Figure 1 for mean ratings of perceived helpfulness and ease of use of specific strategies. Regarding demographic factors, neither age nor level of education was associated with helpfulness or ease of use of any specific mental health strategies, except for a small correlation between age and ease of use of deep breathing strategies (r = −.169, p = .044). There were no statistically significant differences in either helpfulness or ease of use of mental health strategies based on gender identity or race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Mental Health and Therapy Experiences

| Number (Percent) or M (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Diagnoses | Ever Diagnosed | Currently a Problem |

| Anxiety Disorder | 225 (74.3%) | 178 (58.7%) |

| Depression | 227 (74.9%) | 148 (48.8%) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | 153 (50.5%) | 112 (37.0%) |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | 126 (41.6%) | 95 (31.4%) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) | 66 (21.8%) | 41 (13.5%) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 59 (19.5%) | 27 (8.9%) |

| Any of Above | 270 (89.1%) | 230 (75.9%) |

| Prior Therapy Experience | ||

| No | 34 (11.2%) | |

| Yes | 269 (88.8%) | |

| Importance of Therapist’s Autism Knowledge† | 4.48 (0.88) | |

| Type(s) of Therapist | Therapist Type | Autism Knowledge ‡ |

| Psychologist | 210 (69.3%) | 3.41 (1.21) |

| Social Worker | 126 (41.6%) | 3.05 (1.27) |

| Licensed Professional Counselor | 172 (56.8%) | 3.07 (1.25) |

| Other type of therapist | 35 (11.6%) | 3.15 (1.23) |

| Prior Use of Specific Therapy Strategies§ | ||

| Cognitive Strategies | 201 (74.7%) | |

| Mindfulness Meditation | 121 (45.0%) | |

| Deep Breathing | 144 (53.5%) | |

| Guided Imagery or Visualization | 83 (30.9%) | |

| Progressive Muscle Relaxation | 57 (21.2%) | |

| Exposure | 53 (19.7%) | |

| Behavioral Activation | 75 (27.9%) | |

“How important is it to you that your therapist knows a lot about autism?” Response options from 1 = not at all important to 5 = very important.

Among those with experience with this type of therapist, “How much did this therapist know about autism?” Response options from 1 = no knowledge to 5 = a great deal of knowledge.

Among the subsample (n = 269) of those with prior therapy experience.

Figure 1.

Perceived Helpfulness and Ease of Use of Specific Mental Health Strategies

Note: Ratings (M, SE) of helpfulness (1 = not at all helpful to 5 = very helpful) and perceived ease of use (1 = very difficult to 5 = very easy) among the subset of participants with experience with each strategy (see Table 2). PMR = Progressive Muscle Relaxation.

AQ Total Score was significantly negatively correlated with perceived helpfulness of exposure (r = −.353, p = .009) and guided imagery (r = −.253, p = .021). By contrast, AQ was not significantly correlated with helpfulness of other mental health strategies. AQ Total Score was significantly negatively correlated with ease of use of cognitive strategies (r = −.179, p = .011), exposure (r = −.319, p = .020), progressive muscle relaxation (r = −.306, p = .022), and guided imagery (r = −.282, p = .010), but not with ease of use of other mental health strategies.

Qualitative Results: Overall Therapy Experiences

Qualitative analyses of overall mental health experiences (i.e., “What have you found to be most helpful in therapy?” and “What have you found to be least helpful in therapy?”) revealed four primary themes and ten subthemes. Among those who had previously participated in therapy (n = 269), 87% answered the first open-ended question and 84% answered the second open-ended question. Results are presented in Table 3 along with illustrative quotes. The primary themes (indicated as subheading) and subthemes (indicated with italics) are described in more detail below.

Table 3:

Overall Helpfulness of Mental Health Therapy: Themes and Subthemes

| Theme | Subtheme | Number of Participants (%)† | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist acceptance and understanding is crucial | Feeling heard, accepted, and validated | 54 (20.1%) |

|

| Therapist understanding of autism | 31 (11.5%) |

|

|

| Therapy offers tools for personal growth | Importance of talking through and processing issues | 60 (22.3%) |

|

| Gaining new perspectives | 30 (11.2%) |

|

|

| Developing self-understanding | 15 (5.6%) |

|

|

| Talking in session can be difficult | Verbal communication expectations | 17 (6.3%) |

|

| Trouble talking about feelings | 20 (7.4%) |

|

|

| Session format can help or hinder progress | Session structure affects the therapy experience | 18 (6.7%) |

|

| Alternative activities can enhance therapy | 14 (5.2%) |

|

Number and percentage of participants whose responses are consistent with this theme out of the subsample with prior mental health experience (n = 269).

Overall Theme 1: Therapist Acceptance and Understanding is Crucial

Many participants (27% of those with therapy experience) observed that their therapist’s ability to demonstrate acceptance and understanding was central to therapeutic success. For many, feeling heard, accepted, and validated was the most essential element of the therapy experience. P129 found it “really helpful to have someone to talk to who you feel understands,” and for several respondents, this was key to their ability to feel comfortable and fully participate in therapy. P290 observed that “my current therapist makes me feel safe and like it’s okay to open up about how I’m really feeling.” Therapists’ validation of participant’s experiences was an important aspect of nonjudgmental acceptance. P172 explained that “[my therapist] seems to understand what I’m talking about and it makes me feel sane and normal.” P2 noted that his therapist’s “validation” has helped him understand “that I’m not weird.” By the same token, therapist invalidation or lack of understanding was considered especially detrimental to the therapy experience.

Therapist understanding of autism emerged as a separate but related aspect of therapist understanding. Several participants noted that their most helpful therapy experiences were with therapists who “understand autism” (P32). By contrast, therapists who “don’t understand your diagnosis” (P1) led to the least helpful experiences. P140 observed that therapy has not been effective for her because “my therapist frequently doesn’t understand my lens through which I view the world.” P27 recalled that her therapist “viewed [autism] in a stereotypical way and so didn’t really validate me and kept trying to respond to me through a neurotypical lens.”

Overall Theme 2: Therapy Offers Tools for Personal Growth

Many (32% of participants with therapy experience) reported that opportunities for personal growth were the most helpful aspect of therapy. A key aspect of this process was the importance of talking through and processing issues. Many participants simply noted the importance of “talking things through” with a therapist (P38). P28 observed that “talking about things helps me process and understand them,” and P239 added that she appreciates “talking to another person about my problems or feelings because it feels good to let it all out rather than bottling them inside.”

Several participants saw the benefit of gaining new perspectives. For example, P31 noted that her therapist helped her “look at things from a different angle.” P248 observed that “getting an outside opinion on my social interactions has been really helpful,” adding that “a lot of times I don’t understand why someone said [or] did something and asking my therapist about it helps me learn to recognize these behaviors.” P201 described similar benefits: “Having someone else make observations about my thought processes has been helpful to let me see multiple perspectives or maintain a logical perspective about things.”

For many participants, the most important aspect of the therapeutic process was developing self-understanding. P54 appreciated learning “why I feel the way I do” and P93 observed that “learning introspection” was very helpful. P115 observed that “gaining understanding of my motivations and learning why I respond to the world the way I do… has helped me learn strategies that work… and let go of maladaptive coping strategies.”

Overall Theme 3: Talking in Session Can Be Difficult

Several participants with therapy experience (14%) reflected on aspects of talk therapy that are difficult for them as autistic adults. Many noted that verbal communication expectations make therapy difficult. For example, P284 observed that “not knowing what to say” makes it hard for her to participate in therapy, P2 added that she has trouble when the therapist “expects you to do all the talking,” and P82 explained that “sometimes I have something I know I want to say, but most of the time my mind seems to go blank as soon as we sit down together.”

Many participants described having trouble talking about feelings. P70 observed that “talking about how I feel” is unhelpful because “I don’t feel any particular way usually. I have things that are going on and situations I am thinking about, but mostly it’s just stimuli not emotion.” P185 agreed, noting that when her therapist is “asking how something felt throughout the session” it is “hard to express and often makes me anxious to figure out what to say.” P10 observed that “therapies that rely on recording your emotions or describing them in depth” have been unhelpful because “I often felt like the therapist thought I wasn’t trying hard enough, but what was really happening was that I was unable to identify more than extremely basic emotions at the time and I found them quite confusing and the technique sort of pointless.”

Overall Theme 4: Session Format can Help or Hinder Progress

Some participants (11% of those with therapy experience) noted aspects of the session format that played a key role in therapy success. For some, the session structure affects the therapy experience. Having “a clear agenda with well-defined goals” (P19) was seen as especially helpful in providing structure and clear expectations. Providing organization and clear explanations of strategies was also seen as critical. P25 found it especially unhelpful when the therapist “does not explain the terms, concepts, organization, and… theory of the therapeutic modality.” Other aspects of session structure affected participants’ experiences in both positive and negative ways. For example, some participants found the group therapy format to be helpful, while others viewed it as challenging. P12 found that “the way I experience life” doesn’t have “much in common with the group,” while P201 had even more negative experiences of “being verbally assaulted and bullied by the non-autistic group members” because they “know and care nothing about autistic differences.”

In addition to logistical aspects of session structure and format, other participants noted that alternative activities can enhance therapy. P82 explained “sometimes I struggle with talking and to work around that my therapist has art projects for us to do. When I get absorbed in a creative task, it unlocks my throat and I can talk again.” P58 added that journaling as part of therapy helps them “get my thoughts and feelings out” and P263 observed that documenting things in writing “in the moment” was helpful so she “didn’t have to try to remember everything.” Other participants described personalized strategies that were helpful to them, including “pictures” (P270), “creative means to record my story” (118), and “toys to fidget with in the office” (P106).

Qualitative Results: Experiences with Specific Mental Health Strategies

Analyses of participants’ perspectives about specific mental health strategies (i.e., “Please tell us more about how well these strategies worked for you”) revealed four cross-cutting themes and seven more nuanced or strategy-specific subthemes.

Cross-Cutting Theme 1: Helpful for Reducing Anxiety and Improving Mood

A central theme across 6 out of 7 specific strategies (all except exposure) was that autistic adults found them to be helpful for preventing or reducing negative emotional reactions, including helping “calm myself down” (P63), “slow down the anxiety” (P2), and “avoid a meltdown” (P235). The subthemes provide insight into how specific strategies work for autistic adults. Several participants found that cognitive strategies helped them develop more positive thought patterns. For example, P28 explained that “the strategies helped me stop ruminating… [and] redirect negative thoughts.” P248 observed that “it helped learning that I am not my thoughts and I can change my thinking and reframe it.” By contrast, behavioral activation was seen as mood enhancing due to being a “distraction from any negative thoughts” (P163).

Some participants found behavioral activation and visualization to be both enjoyable and rewarding. For example, P237 explained that behavioral activation “would move me from a situation I was not enjoying into one I did enjoy” and P140 reflected that “making time to do things I enjoy is integral to healing when I am depressed.” Regarding visualization, P31 observed that “I love imagining things so picturing a happy place was very easy to me.”

Other strategies were described as having a calming effect due to physiological relaxation. P163 noted that mindfulness meditation “helps calm down my stress response and my body.” Similarly, P273 explained that PMR is “helpful, because it actually helps to calm the body somatically.” Participants found deep breathing to be especially helpful for reducing physiological anxiety and panic. P263 observed that it “helped calm me down when I was too over-stimulated” and P102 noted that it “helped me calm, stop, and prevent anxiety and panic attacks.”

Participants also reflected that mindfulness meditation and deep breathing were effective because of their focus on present-moment experiences. P290 explained that mindfulness meditation helps “let go of anxiety around my past and my future and to instead just focus on the here and the now.” Similarly, P264 observed that “breathing can help me return to the present and calm my nervous system” and P118 noted that “deep breathing can… help me calm down my thoughts/emotions and recenter myself.”

Cross-Cutting Theme 2: Trouble Generalizing to Daily Life

Another theme that was common across strategies (all except exposure) was difficulty generalizing the strategies, particularly in moments of crisis. Many tended to “forget to use them” (P32) in daily life. P55 explained that “it is hard for me to remind myself that I have those [cognitive] skills available to me” and P127 noted that “it’s hard for me to remember to implement [cognitive strategies] in my life.” P25 observed that “I struggle significantly generalizing the changes resulting from cognitive strategies to new situations when environmental changes occur.” P155 explained that “When I am calm… I understand intellectually the concepts of cognitive strategies. However, I find that I fail to be able to implement them when in crisis or when actively dealing with a difficult situation.” P289 added that “in the moment where I would need them, I am often too worked up for them to be useful.” Similarly, P176 observed that “it can be hard to remember to use the PMR strategies when you get too upset or overwhelmed.”

Cross-Cutting Theme 3: Difficult to Implement

Participants commonly found mental health strategies difficult to implement (all except deep breathing). However, responses revealed distinct subthemes that were largely strategy-specific. For cognitive strategies, implementation challenges were primarily due to difficulty identifying and changing thoughts. For example, P10 reflected that “identifying unhelpful thoughts and developing the ability to reframe thoughts was initially very, very difficult, largely because I struggle to recognize my own emotions and express them.” P85 observed that “I can identify the unhelpful thoughts, but it’s difficult for me to reframe or to see another point of view” and P120 added that “it’s hard to change my way of thinking.” Even when they tried changing thoughts, some had trouble believing them. As P138 noted, “it’s hard to convince myself of new thought patterns,” and P230 added, “I still believed my negative thoughts.”

Many participants found it hard to focus attention when trying implement mindfulness meditation. For example, P45 noted that “I am not able to shut my brain down enough to meditate,” and P263 observed that “it was difficult for me to stay focused and not start thinking about other things.” P203 added that “it is very difficult to tune out distractions” during meditation. Others noted that they were not able to focus effectively without support, as P201 expressed, it is “often not possible for me to… maintain focus enough to meditate without another person present helping me.”

Several participants had trouble implementing guided imagery because of difficulty visualizing. For example, P93 reported that “visualization is nearly impossible for me” and P199 noted that “I don’t envision things in my mind at all so I can’t imagine a beach or whatever the imagery calls for.” Others reported that although they could visualize scenes with some effort, they experienced problems with imagining a relaxing scene. For example, P163 observed that “sometimes I imagine a scene that’s too realistic… If I thought of a place with distractions it took me out of the exercise.”

The most challenging aspect of implementing behavioral activation for many participants was logistical barriers. For example, P118 explained that he “had a hard time with other things interfering with the schedules” and many autistic adults noted that it was difficult to “find the time” for additional activities. P201 further explained that “it is not often possible for me to do the activities I enjoy due to financial barriers and availability.”

Cross-Cutting Theme 4: Distressing or Anxiety-Provoking

Some participants reported that certain strategies were distressing to implement. This was most common for exposure (reported by 17% of those who had used exposure). Some reported that these strategies caused “undue stress” (P55), “panic” (P24), or “a meltdown” (P166). Others reported that they “made my issues worse” (P266), “caused more trauma” (P102), and “exacerbated my anxiety and depression” (P3). A smaller proportion of participants described similar concerns with other strategies. For example, a few autistic adults using cognitive strategies (2%) noted that they had the opposite intended effect. For example, P102 explained that “focusing on negative thoughts brought me a flare up of panic attacks.” A small number of participants using mindfulness (7%) and deep breathing (6%) also reported that the strategies made their anxiety worse. P106 reported that “meditation and mindfulness causes shutdowns. I get very upset with having some sort of external stimuli to think about.” P25 explained that “mindfulness when one also has sensory issues can result in overwhelm quickly.” During deep breathing, some participants reported feeling “dizzy” (P140) or that they were “going to hyperventilate” (P258), which led to feelings of anxiety or panic.

Discussion

The current study was conducted to gain a deeper understanding of autistic adults’ experiences and preferences regarding mental health therapy strategies. Consistent with prior research (Croen et al., 2015; Fombonne et al., 2020; Jadav & Bal, 2022; Lai et al., 2019; Lugo-Marín et al., 2019; Rydzewska et al., 2018), mental health problems were highly prevalent in the current sample. Over three-fourths of the sample had a current mental health condition, most commonly anxiety (58.7%) and depression (48.8%). Despite previously documented barriers to mental healthcare (Brede et al., 2022), most participants had received at least some previous counseling or therapy. However, their therapy experiences varied greatly. Overall, the results suggest that factors related to the therapist, the client, and the specific therapeutic approach likely interact to predict overall outcomes.

The findings provide convergent evidence that therapist acceptance, understanding, and validation are critical to therapy success for autistic adults. This is consistent with a larger body of research on the importance of the therapeutic relationship. In fact, therapist empathy and alliance have been found to be robust predictors of therapy success across multiple studies of different therapies and clinical populations (Elliott et al., 2018; Flückiger et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2000). Our results also revealed that the therapist’s understanding of autism is essential for therapeutic alliance with autistic clients, in line with prior research on broader healthcare experiences (Brede et al., 2022; Mazurek et al., 2021). Previous research has found that lack of societal understanding of autism and feeling misunderstood may contribute to stress, isolation, and depression among autistic adults (Cage et al., 2018; Gotham et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2012; Han et al., 2022). The cumulative effects of these broader negative social experiences may make it even more crucial for therapists to establish a safe, accepting, and autism-affirming therapeutic relationship.

For many autistic adults in our sample, therapy helped them develop greater self-understanding. However, the results also suggest that to set the stage for personal growth, therapists must attend to the specific needs of their autistic clients. For some, offering alternative means of communication, providing more structure in session, or providing an agenda to review before the session may help autistic adults gather their thoughts and be able to express themselves more fully. For others, providing alternative activities or adjusting the session format may help facilitate engagement. Although some previous treatment studies have included autism-specific modifications (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2020; Hesselmark et al., 2014; Russell et al., 2013; Sizoo & Kuiper, 2017; Spek et al., 2013), their effects have not been directly tested. Further research is needed to examine the acceptability and success of these accommodations.

This study also provides the first exploration of autistic adults’ experiences with specific types of mental health strategies. Although there was variability across participants, many found that these strategies were helpful for improving mood and reducing anxiety. Overall, the perceived mechanisms of effect were highly consistent with the theoretical framework of each approach. For example, cognitive strategies were described as helpful in developing more positive thoughts, consistent with the cognitive therapy model (Beck & Haigh, 2014; Hofmann et al., 2013). Similarly, participants explained that mindfulness mediation helped reduce anxiety by shifting focus to present-moment experiences, which is the intended mechanism (Baer, 2003). Finally, several strategies were perceived to have a calming physiological effect, including mindfulness meditation, PMR, and deep breathing. Notably, these strategies were perceived to be especially helpful for preventing panic and managing sensory reactivity.

Despite their success for many participants, others reported that they had trouble applying strategies in daily life. Generalization of treatment effects is a challenge across mental health therapies (Westen & Morrison, 2001), and may be even more difficult for autistic clients, who often struggle with generalizing skills to new situations (Klin et al., 2003; Plaisted, 2015). This suggests that therapists should work closely with autistic clients to intentionally focus on real-world generalization of therapeutic strategies. Potential strategies for enhancing generalization could include additional homework assignments (Kazantzis et al., 2000), in vivo practice in new settings (Abramowitz & Arch, 2014), or utilizing technology to provide out-of-session prompts and supports in the daily environment (Loo Gee et al., 2016; Swan et al., 2016).

The results also revealed that person-level factors may affect the success of specific strategies. Adults with higher levels of autistic traits found many strategies to be less helpful (exposure, guided imagery) and more difficult to implement (cognitive strategies, exposure, guided imagery, and PMR). Qualitative results shed some light onto these difficulties. For example, several participants reported that cognitive strategies were difficult because they had trouble changing their thoughts, which may be reflective of the challenges many autistic people experience with cognitive flexibility (Leung & Zakzanis, 2014). Neuropsychological factors may affect implementation of mindfulness-based strategies, as several participants had trouble focusing attention when attempting these techniques. Autistic adults who have problems with attention and concentration (Johnston et al., 2019) may need additional supports to facilitate focused awareness.

Overall, exposure-based strategies were the most difficult for participants to implement, and they were even more difficult and less helpful for those with higher autistic traits. Exposure therapy is an evidence-based treatment for anxiety and considered to be an essential element of CBT protocols (Parker et al., 2018; Pompoli et al., 2018). According to habituation and inhibitory learning models, exposure works by facilitating new learning through repeated exposure to fear-eliciting stimuli until anxiety naturally decreases (Benito & Walther, 2015; Craske et al., 2008). However, clinicians and clients are often reluctant to use these techniques because they evoke distress, even if temporary (Olatunji et al., 2009). Indeed, several participants found these techniques to be highly distressing. While some participants noted that exposure was helpful “in the long run,” others reported that their anxiety did not improve and sometimes worsened. Recent neuroscientific evidence may shed some light on these inconsistencies. For example, Green and colleagues (2019) found that autistic people with high sensory reactivity have atypical brain responses to sensory input, including difficulty with neural habituation and emotional down-regulation. Because exposure-based strategies are based on habituation to anxiety-inducing stimuli, personalized modifications to typical exposure protocols may be helpful for autistic individuals with heightened sensory responsivity (see (Landry et al., 2022).

By contrast, the effectiveness of other strategies may be less affected by autism-specific factors. For example, ratings of mindfulness meditation, deep breathing, and behavioral activation were not associated with level of autistic traits. In addition, behavioral activation was rated positively regarding helpfulness and ease of use, and it was described as both rewarding and enjoyable by several participants. As such, autistic clients may be more accepting of these strategies and better able to implement them relative to techniques that are perceived as more challenging, distressing, or difficult.

Limitations

There are some study limitations that should be noted. First, the sample may not be representative of the larger autism population. The sample was diverse in terms of gender identity and sexual orientation; however, a greater proportion identified as female compared to the larger autism population (Maenner, 2021). The sample also had limited racial/ethnic diversity. Only independent adults (without legal guardians) were eligible to participate, and the study required an ability to read and provide written responses to survey questions, so the findings may not apply to autistic adults with significant cognitive or communication impairments. Similarly, the nature of the study may have led to potential sampling or participation bias. It is possible that autistic adults with greater interests in self-reflection and/or mental health were more motivated to participate in a study focused on those topics and may have been over-represented in the current sample. As such, the results may not reflect the experiences and perspectives of all autistic adults who need access to mental health services.

Another limitation was that all measures were self-report, meaning that we were unable to verify autism diagnoses or directly assess mental health conditions. The study also relied on retrospective recall of previous mental health experiences, which may be subject to memory bias. Future research should use direct, comprehensive, and prospective assessment of these key constructs. It should also be noted that although most participants with prior therapy experience (87%) provided responses to open-ended survey questions, the length of their responses varied. Because the nature of the survey did not allow for in-depth exploration of participant experiences and perceptions, future research would benefit from inclusion of other qualitative methods, such as semi-structured interviews or focus groups. Finally, because this study did not directly assess the delivery of mental health services, we are unable to determine whether therapeutic strategies were implemented with fidelity. As such, the findings reflect autistic clients’ experiences in real-world clinical settings, but they may not reflect the optimal delivery of those interventions.

Conclusions

This study offers new insights into autistic adults’ perspectives and experiences with different mental health strategies. The results underscore the importance of establishing a safe and accepting therapeutic relationship, providing accommodations to support communication needs, and considering individual differences and preferences when selecting mental health strategies for autistic clients. Future research is needed to evaluate the acceptability, efficacy, and comparative effectiveness of a wider range of mental health strategies for this population. Additional research is also needed to examine individual and contextual predictors and moderators of treatment response.

Key Practitioner Message.

Autistic adults have high rates of co-occurring mental health problems, with depression and anxiety being the most common.

Many autistic adults find therapy to be helpful for personal growth and for addressing mood and anxiety.

It is important to autistic clients that their therapists work to understand autism and create an accepting and validating therapeutic relationship.

Autistic clients may need additional support from their therapists in applying mental health strategies in real-world settings.

Many autistic clients would benefit from accommodations to support their communication needs and from an individualized approach to selecting specific mental health strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the participants in this study, who so generously shared their valuable insights and experiences. We appreciate obtaining access to recruit participants through SPARK research match on SFARI Base. We are grateful to all of the families in SPARK, the SPARK clinical sites and SPARK staff.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Virginia and the iTHRIV Scholars Program. The iTHRIV Scholars Program is supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR003015and KL2TR003016.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of our institutional and governmental regulations, the Declaration of Helsinki, and US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Contributor Information

Micah O. Mazurek, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA.

Jessica Pappagianopoulos, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA

Sophie Brunt, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA

Eleonora Sadikova, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA

Rose Nevill, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA.

Michelle Menezes, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA

Christina Harkins, Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, 417 Emmet Street South, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) through the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) Research Match. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Approved researchers can obtain the SPARK population dataset described in this study by applying at https://base.sfari.org.

References

- Abramowitz JS, & Arch JJ (2014). Strategies for improving long-term outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Insights from learning theory. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(1), 20–31. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, & Whiteside SP (2019). Exposure therapy for anxiety: Principles and practice. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S, & Costley D (2016). The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(4), 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, & Clubley E (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Haigh EA (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevides TW, Shore SM, Andresen M-L, Caplan R, Cook B, Gassner DL, Erves JM, Hazlewood TM, King MC, & Morgan L (2020). Interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults: A systematic review. Autism, 24(6), 1345–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevides TW, Shore SM, Palmer K, Duncan P, Plank A, Andresen M-L, Caplan R, Cook B, Gassner D, & Hector BL (2020). Listening to the autistic voice: Mental health priorities to guide research and practice in autism from a stakeholder-driven project. Autism, 24(4), 822–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson M (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Benito KG, & Walther M (2015). Therapeutic process during exposure: Habituation model. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 6, 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DA, & Borkovec TD (1973). Progressive relaxation training: A manual for the helping professions. Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brede J, Cage E, Trott J, Palmer L, Smith A, Serpell L, Mandy W, & Russell A (2022). “We Have to Try to Find a Way, a Clinical Bridge”-autistic adults’ experience of accessing and receiving support for mental health difficulties: A systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 93, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E, Di Monaco J, & Newell V (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JA, & Hofmann SG (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 35(6), 502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S, Bradley L, Shaw R, & Baron-Cohen S (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang X, Chien C, & Cheng J (2017). The effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing relaxation training for reducing anxiety. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 53(4), 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Adams F, Harper G, Welch J, & Pellicano E (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 23(2), 477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, & Baker A (2008). Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(1), 5–27. 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen LA, Zerbo O, Qian Y, Massolo ML, Rich S, Sidney S, & Kripke C (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 814–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, & Huibers MJ (2016). How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 245–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Andersson G, & Van Oppen P (2008). Psychotherapy for depression in adults: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daake DR, & Gueldner SH (1989). Imagery instruction and the control of postsurgical pain. Applied Nursing Research, 2(3), 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Rose CE, McArthur D, & Maenner M (2020). National and state estimates of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4258–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich-May J, Simpson G, Stewart LM, Kennedy SM, Rowley AN, Beaumont A, Alessandri M, Storch EA, Laugeson EA, Frankel FD, & Wood JJ (2020). Treatment of anxiety in older adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 84(2), 105–136. 10.1521/bumc_2020_84_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Bohart AC, Watson JC, & Murphy D (2018). Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngäs H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick U (2013). The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, & Horvath AO (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Green Snyder L, Daniels A, Feliciano P, & Chung W (2020). Psychiatric and medical profiles of autistic adults in the SPARK cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3679–3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Bishop SL, Brunwasser S, & Lord C (2014). Rumination and perceived impairment associated with depressive symptoms in a verbal adolescent–adult ASD sample. Autism Research, 7(3), 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Brunwasser SM, & Lord C (2015). Depressive and anxiety symptom trajectories from school age through young adulthood in samples with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Marvin AR, Taylor JL, Warren Z, Anderson CM, Law PA, Law JK, & Lipkin PH (2015). Characterizing the daily life, needs, and priorities of adults with autism spectrum disorder from Interactive Autism Network data. Autism, 19(7), 794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Hernandez L, Lawrence KE, Liu J, Tsang T, Yeargin J, Cummings K, Laugeson E, Dapretto M, & Bookheimer SY (2019). Distinct patterns of neural habituation and generalization in children and adolescents with autism with low and high sensory overresponsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(12), 1010–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith GM, Totsika V, Nash S, & Hastings RP (2012). ‘I just don’t fit anywhere’: Support experiences and future support needs of individuals with Asperger syndrome in middle adulthood. Autism, 16(5), 532–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han E, Scior K, Avramides K, & Crane L (2022). A systematic review on autistic people’s experiences of stigma and coping strategies. Autism Research, 15(1), 12–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, & Hofmann SG (2017). The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process‐based care. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Uljarević M, Wilmot M, Richdale A, & Dissanayake C (2018). Understanding depression and thoughts of self-harm in autism: A potential mechanism involving loneliness. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselmark E, Plenty S, & Bejerot S (2014). Group cognitive behavioural therapy and group recreational activity for adults with autism spectrum disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 18(6), 672–683. 10.1177/1362361313493681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra RA, Vinkhuyzen AA, Wheelwright S, Bartels M, Boomsma DI, Baron-Cohen S, Posthuma D, & Van Der Sluis S (2011). The construction and validation of an abridged version of the autism-spectrum quotient (AQ-Short). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 589–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJ, & Beck AT (2013). The science of cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, & Fang A (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, & Oh D (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollocks MJ, Lerh JW, Magiati I, Meiser-Stedman R, & Brugha TS (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 559–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadav N, & Bal VH (2022). Associations between co‐occurring conditions and age of autism diagnosis: Implications for mental health training and adult autism research. Autism Research, 15(11), 2112–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston K, Murray K, Spain D, Walker I, & Russell A (2019). Executive function: Cognition and behaviour in adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4181–4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokiranta-Olkoniemi E, Gyllenberg D, Sucksdorff D, Suominen A, Kronström K, Chudal R, & Sourander A (2021). Risk for premature mortality and intentional self-harm in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(9), 3098–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Deane FP, & Ronan KR (2000). Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(2), 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird E, Stewart C, & Tchanturia K (2019). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 55, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kröger C, & Kosfelder J (2010). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 936–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, & Volkmar F (2003). The enactive mind, or from actions to cognition: Lessons from autism. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1430), 345–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M-C, Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, Mandy W, Szatmari P, & Ameis SH (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry LN, Clayton RJ, Mcneel MM, Guzick A, Berry LN, Schneider SC, & Storch EA (2022). Exposure therapy for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders among individuals with autism spectrum disorder. In Clinical Guide to Exposure Therapy (pp. 109–124). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, & Hopko SD (2001). A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: Treatment manual. Behavior Modification, 25(2), 255–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung RC, & Zakzanis KK (2014). Brief report: Cognitive flexibility in autism spectrum disorders: A quantitative review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2628–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, McDavid J, Comtois KA, & Murray-Gregory AM (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(5), 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo Gee B, Griffiths KM, & Gulliver A (2016). Effectiveness of mobile technologies delivering Ecological Momentary Interventions for stress and anxiety: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 23(1), 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Marín J, Magán-Maganto M, Rivero-Santana A, Cuellar-Pompa L, Alviani M, Jenaro-Rio C, Díez E, & Canal-Bedia R (2019). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 59, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), 1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Garske JP, & Davis MK (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason D, McConachie H, Garland D, Petrou A, Rodgers J, & Parr JR (2018). Predictors of quality of life for autistic adults. Autism Research, 11(8), 1138–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO (2014). Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(3), 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Sadikova E, Cheak-Zamora N, Hardin A, Huerta I, Sohl K, & Malow BA (2021). They deserve the “same level of care that any other person deserves”: Caregiver perspectives on healthcare for adults on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 89, 101862. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley BF, Tillmann J, Ahmad J, Crawley D, San José Cáceres A, Holt R, Charman T, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, & Simonoff E (2021). How do core autism traits and associated symptoms relate to quality of life? Findings from the Longitudinal European Autism Project. Autism, 25(2), 389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Deacon BJ, & Abramowitz JS (2009). The cruelest cure? Ethical issues in the implementation of exposure-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(2), 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Parker ZJ, Waller G, Gonzalez Salas Duhne P, & Dawson J (2018). The role of exposure in treatment of anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 18(1), 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Plaisted KC (2015). Reduced generalization in autism: An alternative to weak central coherence. In Burack JA, Charman T, Yirmiya N, & Zelazo PR (Eds.), The development of Autism: Perspectives from Theory and Research (pp. 149–169). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, Imai H, Tajika A, & Salanti G (2018). Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: A systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(12), 1945–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AJ, Jassi A, Fullana MA, Mack H, Johnston K, Heyman I, Murphy DG, & Mataix-Cols D (2013). Cognitive behavior therapy for comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety, 30(8), 697–708. 10.1002/da.22053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzewska E, Hughes-McCormack LA, Gillberg C, Henderson A, MacIntyre C, Rintoul J, & Cooper S-A (2018). Prevalence of long-term health conditions in adults with autism: Observational study of a whole country population. BMJ Open, 8(8), e023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier M (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sizoo BB, & Kuiper E (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction may be equally effective in reducing anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 64, 47–55. 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, Murphy D, & Happe F (2015). Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: A review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 9, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Spek AA, van Ham NC, & Nyklíček I (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 246–253. 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan AJ, Carper MM, & Kendall PC (2016). In pursuit of generalization: An updated review. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 733–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, & Morrison K (2001). A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: An empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 875–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Simmons GL, Gotham KO, Conner CM, Smith IC, Beck KB, & Mazefsky CA (2018). Psychosocial treatments targeting anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum: Review of the latest research and recommended future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(10), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) through the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) Research Match. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Approved researchers can obtain the SPARK population dataset described in this study by applying at https://base.sfari.org.