Abstract

Background & Aims

Impaired gastric motor function in the elderly causes reduced food intake leading to frailty and sarcopenia. We previously found that aging-related impaired gastric compliance was mainly owing to depletion of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), pacemaker cells, and neuromodulator cells. These changes were associated with reduced food intake. Transformation-related protein 53–induced suppression of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK)1/2 in ICC stem cell (ICC-SC) cell-cycle arrest is a key process for ICC depletion and gastric dysfunction during aging. Here, we investigated whether insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), which can activate ERK in gastric smooth muscles and invariably is reduced with age, could mitigate ICC-SC/ICC loss and gastric dysfunction in klotho mice, a model of accelerated aging.

Methods

Klotho mice were treated with the stable IGF1 analog LONG R3 recombinant human (rh) IGF1 (150 μg/kg intraperitoneally twice daily for 3 weeks). Gastric ICC/ICC-SC and signaling pathways were studied by flow cytometry, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry. Gastric compliance was assessed in ex vivo systems. Transformation-related protein 53 was induced with nutlin 3a and ERK1/2 signaling was activated by rhIGF-1 in the ICC-SC line.

Results

LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment prevented reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and gastric ICC/ICC-SC decrease. LONG R3 rhIGF1 also mitigated the reduced food intake and impaired body weight gain. Improved gastric function by LONG R3 rhIGF1 was verified by in vivo systems. In ICC-SC cultures, rhIGF1 mitigated nutlin 3a–induced reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell growth arrest.

Conclusions

IGF1 can mitigate age-related ICC/ICC-SC loss by activating ERK1/2 signaling, leading to improved gastric compliance and increased food intake in klotho mice.

Keywords: IGF1, Aging, Interstitial Cells of Cajal, Stem Cells, ERK

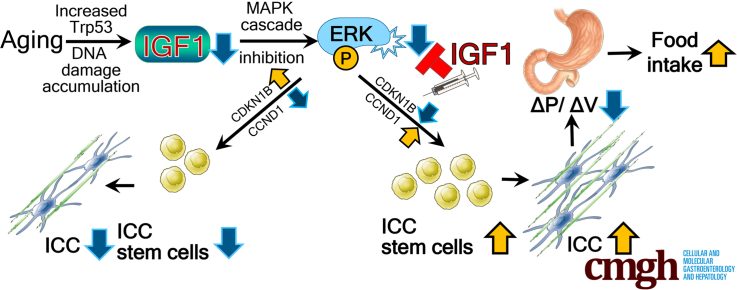

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Aging-associated suppression of extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase signaling in interstitial cells of Cajal (pacemaker cells of gastric motility) stem cells (ICC-SC) is a key process in ICC depletion and gastric motor dysfunction. Extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase activation by insulin-like growth factor 1 can mitigate age-related ICC/ICC-SC loss, leading to improved gastric motor function.

Aging is one of the major health challenges because the population aged 65 and older is increasing exponentially and projected to be 83.7 million in the United States in 2050 (www.census.gov). This exponential increase in the aging population will continue to have a negative impact on both society and health care systems. Aging results in a general decline of function in most organs, including the stomach, and a reduced capability to regenerate tissues.1,2 Age-related gastric motor dysfunction includes reduced nitrergic relaxation, compliance, and accommodation, leading to reduced food intake.3,4 Although these functional changes may be relatively subtle and often underestimated owing to nonspecific symptoms, complicated mechanisms, and insufficient medical attention, they have been shown to contribute to early satiety, increased satiation, and a consequent decrease in caloric/dietary intake.2 Previous reports have shown reduced food intake resulting from gastric dysfunction may negatively affect quality of life, sarcopenia, frailty, disability, and mortality in the advanced age,2,5, 6, 7, 8 which have been shown to be exacerbated further with coronavirus disease 2019 and its related restrictions.9 For these reasons, it is imperative to improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying age-related gastric dysfunction to improve healthy aging and longevity.

Previously, our group described a profound decrease of both interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), mesenchymal-derived pacemaker and neuromodulator cells in the gastrointestinal tract, and ICC progenitor or stem cells (ICC-SC) in the stomach of mice deficient in anti-aging protein α-Klotho (klotho mice; a model of accelerated aging) and naturally aged mice.10,11 Aging-related ICC loss is associated with gastric dysfunction such as impaired fundic relaxation and reduced gastric compliance, the hallmarks of ICC loss functionally verified from specific genetic causes.10, 11, 12 These changes occur in the absence of enteric neuron loss or down-regulation of nitric oxide synthase expression.10 These functional declines are linked to reduced food intake and may lead to frailty and sarcopenia in klotho mice.10,13 We also showed that age-associated ICC-SC decline plays a major role in age-related ICC loss and associated gastric dysfunctions.11 Age-associated ICC-SC decline is linked to suppression of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 and 1) signaling pathway.11 Reduced cyclin D1 (CCND1), together with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (CDKN1B also known as p27Kip1), down-regulated ICC-SC proliferation and self-renewal by interfering with cell-cycle entry.11 However, it remains unclear how to stimulate regeneration of aged ICC-SC in the stomach to restore impaired gastric function.

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) is the nutrient-sensing hormone that coordinates growth, differentiation, self-renewal, and metabolism in response to nutrient availability.14 IGF1 can activate the ERK signaling pathway in gastric smooth muscle15 and invariably is reduced with age.16 Indeed, a profound reduction in serum IGF1 has been observed in klotho mice and older individuals.6,10 Furthermore, reduced IGF1 signaling inhibits ICC-SC proliferation, leading to depletion of ICC.15,17 Taken together, these findings suggest aging-related ICC-SC/ICC decline may be mediated by reduced ERK phosphorylation owing to a decrease in IGF1 with age. Although down-regulation of IGF1 signaling has been shown to prolong the lifespan in model systems,18 IGF1 may be neuroprotective and facilitate aged skin, muscle, and hematopoietic stem cell regeneration, suggesting a protective role of IGF1 against age-related tissue dysfunction, especially in advanced age.16,19 Here we investigated the hypothesis that supplementation of IGF1 can regenerate a reduced age-associated ICC-SC pool by activating the ERK signaling pathway. Our findings in progeric klotho and naturally aged mice and in human gastric tissues obtained from young and aged donors show a link between reduced IGF1, ERK phosphorylation, and ICC decline with age. Our data also suggest that IGF1 supplementation in klotho mice can mitigate reduced aging-associated ERK phosphorylation, ICC/ICC-SC loss, impaired gastric compliance, and reduced food intake. ERK activation by IGF1 also seemed to result in improved overall appearance, increased body weight, and an extended lifespan of klotho mice. The effects of IGF1 are linked to the prevention of cell-cycle arrest of ICC-SC via activation of ERK signaling.

Results

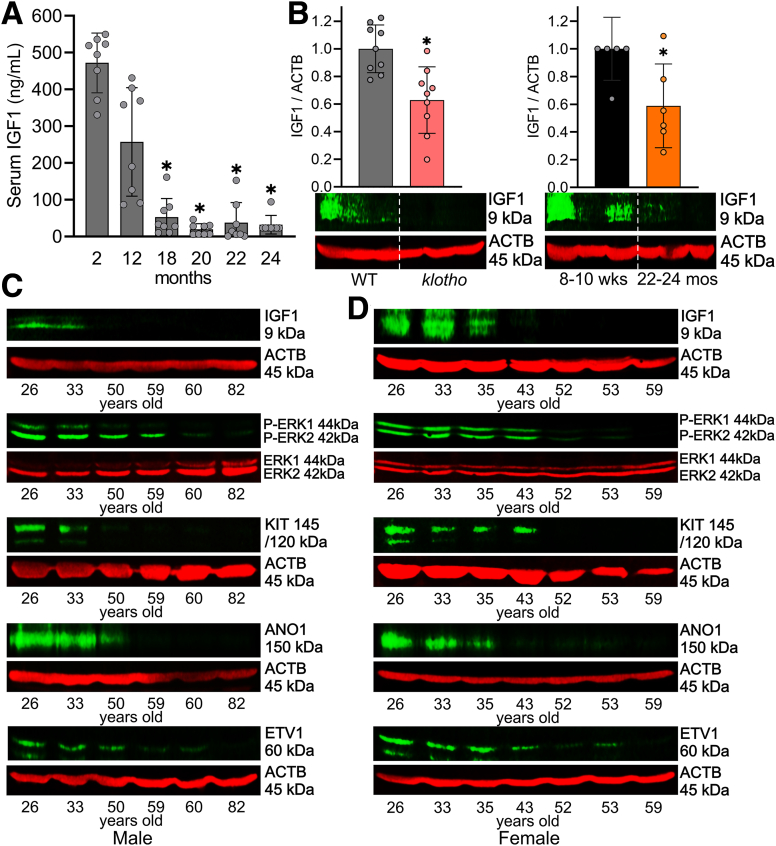

Aging-Related IGF1 Decline Is Associated With Reduced ICC and ERK Phosphorylation

Circulating IGF1 levels decrease from age 20 until the end of life in human beings.14 Previously, we found that serum IGF1 is robustly reduced in progeric klotho mice compared with age-matched wild-type (WT) mice.10,20 To extend their validity to naturally aged mice, we first measured serum IGF1 from male C57BL/6J mice between 2 and 24 months of age using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Serum IGF1 decreased sharply between 12 and 18 months of age, and reached the minimum at approximately 20 months of age (Figure 1A). Local expression of IGF1 rather than circulating IGF1 could be responsible for the tissue-protective effect.21 Thus, we measured IGF1 protein levels in gastric tunica muscularis of progeric klotho to establish the tissue level significance by Western blot (WB). Relative to age- and sex-matched WT mice, gastric IGF1 protein levels of klotho mice were reduced significantly (Figure 1B, left panel). To extend their validity to naturally aged mice, we also measured gastric IGF1 protein levels in aged C57BL/6J mice (age, 22–24 mo, which is equivalent to ∼70-year-old human beings)22 and young C57BL/6J mice (age, age 8–10 wk, which is equivalent to ∼15-year-old human beings). Compared with young mice, gastric IGF1 protein levels of aged mice also were reduced significantly (Figure 1B, right panel). We also measured gastric IGF1 protein expression and ICC markers in human beings between 26 and 82 years of age in both men and women to correlate mouse findings to human beings. Gastric IGF1 protein gradually decreased with age, and this reduction was associated with the reduction of v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KIT) (stem cell factor receptor, a key ICC marker), anoctamin 1 (ANO1; a calcium-activated chloride channel and another key ICC marker), ets variant 1 (ETV1, a master regulator of the ICC transcriptional program) protein, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the stomachs of both men (Figure 1C) and women (Figure 1D) individuals. These findings suggest that reduced ERK phosphorylation as a result of IGF1 decline also occurs in human beings with age and likely contributes to ICC decline.

Figure 1.

Age-related IGF1 decline is associated with reduced KIT and ERK phosphorylation. (A) Age-associated reduction of serum IGF1 levels determined by ELISA between 2 and 24 months of age (8 mice/time point). ∗P < .05 vs 2-month-old using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance. (B) Reduced IGF1 protein in klotho mouse gastric lysates compared with WT controls and in old vs young mice (n = 6–9/group). The klotho and WT mice were used between 60 and 70 days of age. ACTB (actin beta) was used as a loading control. Statistical significance was determined using Mann–Whitney rank sum tests. ∗P < .05. Age-associated down-regulation of IGF1, ERK phosphorylation, KIT, ANO1, and ETV1 protein in gastric muscles of patients between 26 and 82 years of age in (C) men and (D) women.

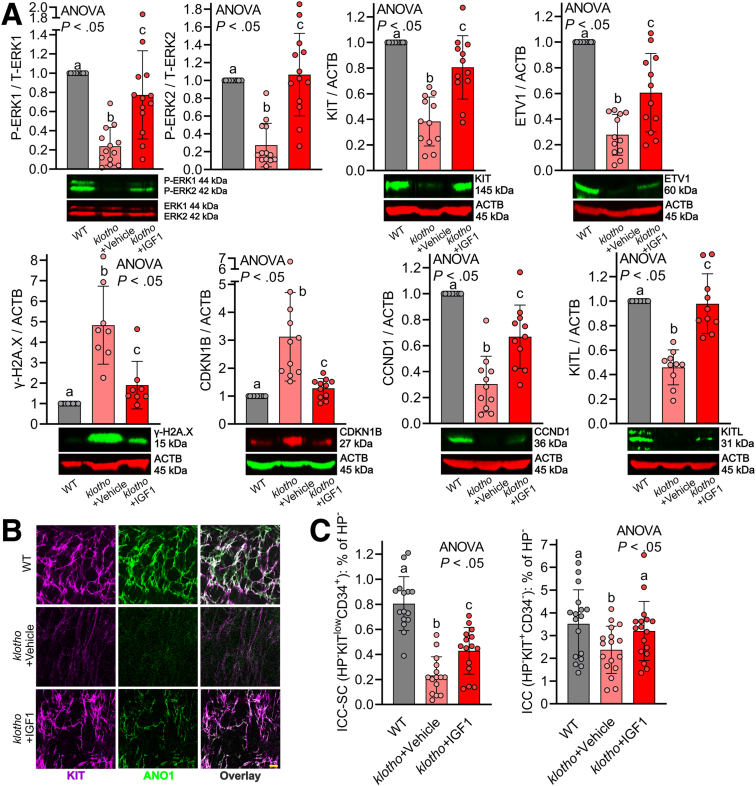

LONG R3 Recombinant Human IGF1 Treatment Restored Age-Related ICC/ICC-SC Decline via Activation of ERK1/2 Pathway in Klotho Mice

We tested whether LONG R3 recombinant human IGF1 (LONG R3 rhIGF1; 150 μg/kg intraperitoneally twice daily for 3 weeks), a stable IGF1 analog, can restore reduced ICC/ICC-SC and impaired gastric motor dysfunction in klotho mice. LONG R3 rhIGF1 or vehicle injections were initiated when the mice were approximately 6 weeks old; that is, at the time when klotho mice begin to display a wide array of premature aging phenotypes, which lead to their death at approximately 65 days of age.23 By WB, we found 3-week treatment with LONG R3 rhIGF1 was able to prevent reduction of ERK phosphorylation in klotho mice, verifying the effect of LONG R3 rhIGF1 on gastric muscles (Figure 2A, upper left panel). LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment also mitigated reductions in KIT and ETV1 proteins in the stomach of klotho mice, suggesting LONG R3 rhIGF1 mitigates ICC loss in these mice (Figure 2A, upper middle and right panels). Of note, the same treatment mitigated the increased DNA damage response (DDR)-associated histone modification γ-H2A.X (H2A.X phosphorylated at Ser 139, a marker for DNA damage accumulation) protein in the stomach of klotho mice (Figure 2A, lower left panel), suggesting LONG R3 rhIGF1 prevents the accumulation of DNA damage in klotho mice as occurs during aging. We previously found that the aging-related reduced ERK signaling pathway leads to cell-cycle arrest via up-regulated CDKN1B and down-regulated CCND1 (also known as cyclin D1).11 Thus, we also measured CDKN1B and CCND1 protein in these mice by WB. WB results showed that LONG R3 rhIGF1 mitigated up-regulated CDKN1B and down-regulated CCND1 protein expression in the klotho mice (Figure 2A, lower middle left and right panels), suggesting that LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment restores ICC/ICC-SC through the ERK–CDKN1B–CCND1 pathway in klotho mice. Previous studies from our group established that ICC do not express IGF1 or insulin receptors and IGF1/insulin effects are mediated by stem cell factor (or KIT ligand [KITL]) expressed by smooth muscle cells, which respond directly to insulin and IGF1.24,25 Furthermore, we also provided direct evidence indicating that IGF1 stimulates KITL in gastric smooth muscles.15 Thus, we also measured KITL protein expression in these mice. As shown in our previous study,10 KITL protein expression was reduced in klotho mice, and this reduction was significantly restored by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment (Figure 2A, lower right panel). Thus, reduced KITL also might contribute to the effect of IGF1 on ICC/ICC-SC decline with age. ICC networks were assessed by KIT and ANO1 immunostaining and confocal microscopy. Compared with age-matched WT mice, ICC networks were diffusely and grossly reduced throughout the klotho stomach, and LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment restored reduced ICC networks of klotho mice (Figure 2B), verifying KIT and ETV1 WB results. Because reduced tissue-specific stem cell numbers and functions are believed to underlie age-related organ dysfunction,26,27 we also enumerated KITlowCD44+CD34+ ICC-SCs as well as KIT+CD44+CD34- ICC in the hematopoietic marker–negative fraction in the gastric corpus + antrum of these mice using previously established and validated protocols.17,28,29 LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment significantly restored the reduced ICC-SC in klotho mice (Figure 2C). Consistent with WB and immunohistochemistry results, ICC was reduced in klotho mice and LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment also restored reduced ICC (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

LONG R3rhIGF1 treatment restored age-related ICC/ICC-SC decline via activation of the ERK1/2 pathway in klotho mice. (A) LONG R3 rhIGF1 (IGF1) restored the decline in ERK phosphorylation (upper left panel), KIT protein (upper middle panel), and ETV1 protein (upper right panel), and mitigated increased DNA damage response-associated γ-H2A.X (H2AXS139p) protein (lower left panel), increased CDKN1B protein (lower middle left panel), reduced CCND1 protein (lower middle right panel), and reduced KITL protein (lower right panel) in gastric tunica muscularis of klotho mice (n = 8–11/group). ACTB (actin beta) was used as a loading control. (B) Reduced gastric ICC networks in klotho mice were restored by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment. Representative confocal stacks showing KIT+ (magenta) and ANO1+ (green) ICC in corresponding regions of the gastric corpus (greater curvature, full thickness) of a WT and klotho mice. N = 3/group. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Restored ICC (KIT+CD34- cells) and ICC-SC (KITlowCD34+ cells) numbers detected by flow cytometry in the nonhematopoietic CD44+ fraction of gastric muscles of klotho mice (n = 15/group). Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA on ranks). HP, hematopoietic cells; P-ERK1, Pextracellular signal-regulated kinase 1; T-ERK1, T-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1.

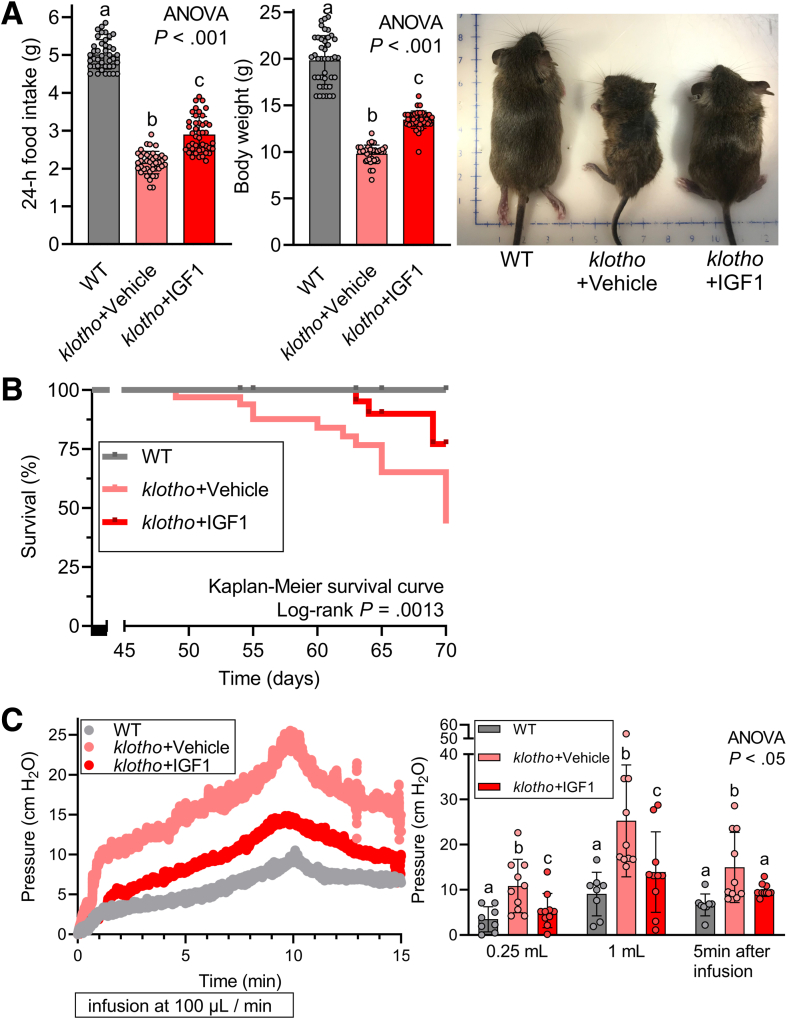

LONG R3 rhIGF1 Treatment Restored Reduced Food Intake, Impaired Body Weight Gain, and Gastric Compliance of Klotho Mice

Gastric ICC loss and gastric dysfunction are associated with impaired body weight gain and reduced food intake in klotho mice.10,11 Therefore, we also monitored body weight and food intake in the mice exposed to LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment. Indeed, both impaired body weight gain and reduced food intake were improved significantly by LONG R3 rhIGF1 in klotho mice (Figure 3A, left and middle panels), suggesting that restoring ICC loss also could improve gastric function such as impaired compliance. Of note, klotho mice treated with LONG R3 rhIGF1 looked healthier than vehicle-treated klotho mice (Figure 3A, right panel). More importantly and surprisingly, the lifespan of klotho mice treated with LONG R3 rhIGF1 was extended significantly compared with vehicle-treated klotho mice (Figure 3B), suggesting beneficial effects of LONG R3 rhIGF1 on the lifespan and health span of klotho mice.

Figure 3.

LONG R3rhIGF1 treatment restored reduced food intake, impaired body weight gain, and reduced gastric compliance of klotho mice. (A) Restoration of reduced food intake (left panel) and body weight gain (middle and right panels) in klotho mice by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment (n = 42–44/group). (B) Kaplan–Meier curves showing overall survival indicated in mice. Note the significantly improved lifespan of klotho mice by IGF1 treatment (P = .0013). Statistical significance of survival curves was analyzed with the log-rank test. (C) Reduced gastric compliance of intact stomachs excised from vehicle- or IGF1-treated klotho mice and age-matched WT mice (n = 8–10/group). Stomachs were inflated with 1 mL Krebs solution at 37°C at a rate of 0.1 mL/min while recording luminal pressure for 10 minutes. After a 10-minute infusion, the infusion was stopped and recorded for an additional 5 minutes. Note significantly improved reduced compliance of klotho mice by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment. Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA on ranks).

Next, to obtain mechanistic insights into the relationship between reduced ICC/ICC-SC and impaired body weight gain/food intake, we measured the ex vivo gastric compliance of these mice. This test was performed to examine the ability to allow the stomach to accept a volume load without a significant increase in gastric pressure. As we showed previously, gastric compliance of klotho mice was impaired compared with WT counterparts (Figure 3C). This impaired gastric compliance of klotho mice was improved significantly by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment, indicating the restored ability of the stomach to relax in response to filling (Figure 3C). Taken together, improved gastric compliance by LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment suggests the functional significance of ICC preservation and a potential link between the effect of IGF1 on ICC and food intake and body weight gain.

Restoration of Reduced ERK1/2 Activation by rhIGF1 Mitigates Transformation-Related Protein 53-Induced ICC-SC Loss

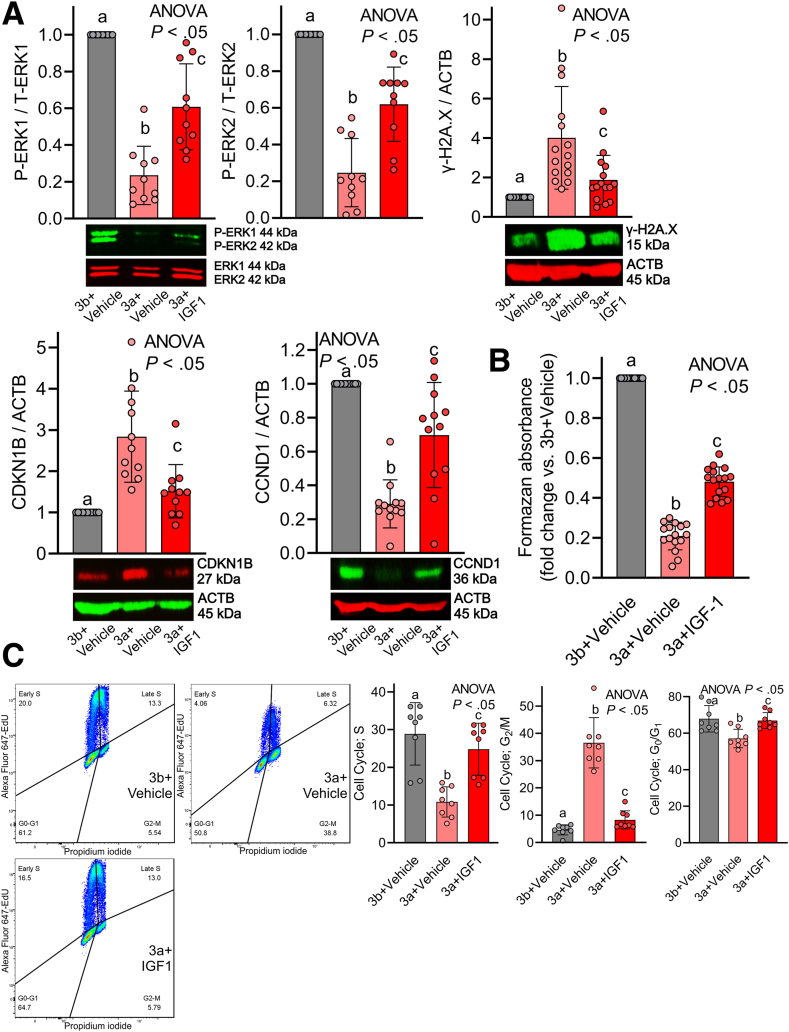

Our previous findings implicate that age-related, cell-cycle arrest of ICC-SC is a primary target of transformation-related protein (Trp53)-induced (a key protein of DDR and aging) suppression of ERK1/2.11 Therefore, we examined whether rhIGF1 could mitigate Trp53-induced reduced ERK and ICC-SC cell-cycle arrest. Trp53 was induced with the murine double minute 2 antagonist nutlin 3a (30 μmol/L), with the inactive enantiomer nutlin 3b (30 μmol/L) serving as a control in D2211B cells, in the ICC-SC line established previously in Dr Ordog’s laboratory (Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN).17,30 A total of 100 ng/mL rhIGF1 co-treatment mitigated nutlin 3a–induced reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, DNA damage accumulation assessed by the DDR marker γ-H2A.X, and reduced cell growth assessed by increased CDKN1B and reduced CCND1 (Figure 4A). We also assessed viable cell counts of ICC-SC by methyltetrazolium salt (MTS) assay. By MTS assay, rhIGF1 co-treatment significantly restored nutlin 3a–induced cell viability reduction of ICC-SC (Figure 4B). Next, we performed cell-cycle analysis by flow cytometry using Alexa Fluor 647–tagged 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation and propidium iodide (PI) labeling to examine the mechanism of rhIGF1 on nutlin 3a–induced ICC-SC growth arrest. As we showed previously,11 30 μmol/L nutlin 3a treatment revealed cell-cycle arrest in the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint (G2/M phase) with a concomitant reduction of cells in G0/G1 and a synthesis phase also known as the S phase in ICC-SC D2211B cells (Figure 4C). rhIGF1 co-treatment significantly mitigated nutlin 3a–induced G2/M cell-cycle arrest and a reduction of S phase (Figure 4C). Collectively, these findings indicate that rhIGF1 co-treatment stimulates cell-cycle progression by preventing the CDKN1B–CCND1 signaling pathway and mitigating DNA damage accumulation induced by nutlin 3a.

Figure 4.

Restoration of reduced ERK activation by rhIGF1 mitigates Trp53-induced ICC-SC loss in vitro. (A) rhIGF1 (100 ng/mL) mitigated nutlin 3a–induced (30 μmol/L) reduced ERK phosphorylation (upper left panel), and DNA damage accumulation (upper right panel), reduced CDKN1B (lower left panel), and reduced CCND1B (lower right panel) in ICC-SC line D2211B previously established in Dr Ordog’s laboratory (Rochester MN) and well characterized11,17 (n = 10–15/group). Trp53 was induced with the murine double minute 2 antagonist nutlin 3a (30 μmol/L), with the inactive enantiomer nutlin 3b (30 μmol/L) serving as a control. ACTB (actin beta) was used as a loading control. Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA on ranks). (B) rhIGF1 treatment restored nutlin 3a–induced reduction of ICC-SC cell viability by MTS assay (n = 16/group). Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way ANOVA (ANOVA on ranks). (C) rhIGF1 treatment prevented nutlin 3a–induced G2/M cell-cycle arrest of ICC-SC. Cell-cycle analysis by combined Alexa Fluor 647–EdU incorporation and PI labeling. Left panels: Representative Alexa Fluor 647 EdU vs PI (area) projections of events gated for single cells with at least diploid DNA content. Right panels: Cell frequencies in the cell-cycle phases identified in the quadrants (n = 8/group). Horizontal lines indicate mean frequencies. Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way ANOVA (ANOVA on ranks). P-ERK1, P-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1; T-ERK1, T-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1.

Restoration of Reduced ERK Activation by rhIGF1 Mitigates Trp53-Induced ICC Loss

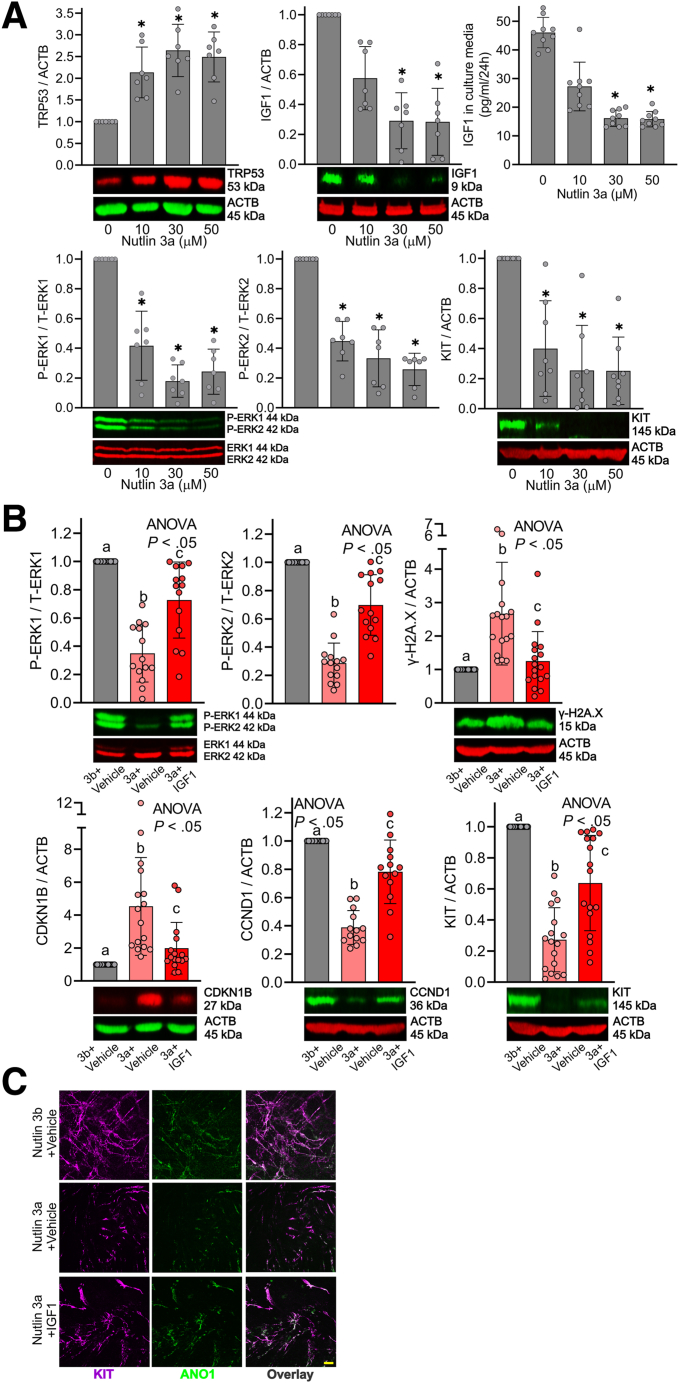

To extend in vitro findings to physiologically more relevant systems, we examined the effects of rhIGF1 in Trp53-induced ICC/ICC-SC loss using organotypic cultures (ex vivo culture systems) of gastric corpus + antrum muscles. In organotypic cultures, nutlin 3a applied for 3 days dose-dependently up-regulated Trp53 protein expression (Figure 5A, upper left panel). Interestingly, the same treatment reduced gastric IGF1 protein expression by WB and secreted IGF1 from gastric muscle cultures by ELISA in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A, upper middle and right panels). These findings suggest that Trp53 directly inhibits IGF1 levels in the stomach as previously proposed in Trp53 truncated isoform–overexpressing mice.31 Similar to findings obtained from ICC-SC cultures, Trp53 up-regulation by nutlin 3a was correlated with a reduction of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and KIT protein expression (Figure 5A, lower panels), suggesting ICC loss via reduced ERK1/2 activation in ex vivo cultures. A total of 30 μmol/L nutlin 3a seemed to achieve maximal effects in gastric organotypic cultures and we examined the effects of rhIGF1 co-treatment on 30 μmol/L nutlin 3a in the next set of experiments. Similar to ICC-SC cultures, rhIGF1 treatment significantly prevented nutlin 3a–induced reduced ERK phosphorylation, up-regulated γ-H2A.X protein (DNA damage accumulation), and reduced CCND1 and increased CDKN1B protein expression in gastric muscle cultures, all measured by WB (Figure 5B). Of note, rhIGF1 treatment also significantly mitigated reduced KIT protein expression (Figure 5B, lower right panel), suggesting preservation of ICC in ex vivo cultures by rhIGF1 in the presence of nutlin 3a. This finding was validated further by whole-mount KIT and ANO1 co-staining, showing that reduced ICC networks by nutlin 3a were restored by rhIGF1 co-treatment (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Restoration of reduced ERK activation by IGF1 mitigates Trp53-induced ICC loss. (A) The Trp53 activator Nutlin 3a applied for 3 days dose-dependently increased TRP53 protein, and reduced IGF1 protein, ERK phosphorylation, and KIT protein by WB (n = 7–12/group) in gastric corpus + antrum tunica muscularis organotypic cultures from 12- to 14-day-old C57BL/6J mice. The same treatment dose-dependently reduced IGF1 secreted from gastric organotypic cultures by ELISA (n = 8/group). ACTB (actin beta) was used as a loading control. ∗P < .05 vs vehicle control (0 μmol/L) using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA on ranks). (B) rhIGF1 (100 ng/mL) mitigated nutlin 3a–induced (30 μmol/L) reduced ERK phosphorylation (upper left panel), and DNA damage accumulation (upper right panel), increased CDKN1B (lower left panel), reduced CCND1 (lower right panel), and reduced KIT protein (lower right panel) in gastric corpus + antrum tunica muscularis organotypic cultures from 12- to 14-day-old C57BL/6J mice (n = 13–17/group). The inactive enantiomer nutlin 3b (30 μmol/L) served as a control for nutlin 3b. ACTB was used as a loading control. Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis 1-way ANOVA (ANOVA on ranks). (C) Reduced gastric ICC networks by nutlin 3a (30 μmol/L) in gastric corpus + antrum tunica muscularis organotypic cultures from 12- to 14-day-old C57BL/6J mice were restored by rhIGF1 treatment. Representative confocal stacks showing KIT+ (magenta) and ANO1+ (green) ICC in corresponding regions of the gastric corpus (greater curvature, full thickness) of nutlin 3b (30 μmol/L) + vehicle, nutlin 3a (30 μmol/L) + vehicle, and nutlin 3a (30 μmol/L) + rhIGF1 (100 ng/mL). n = 3/group. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Discussion

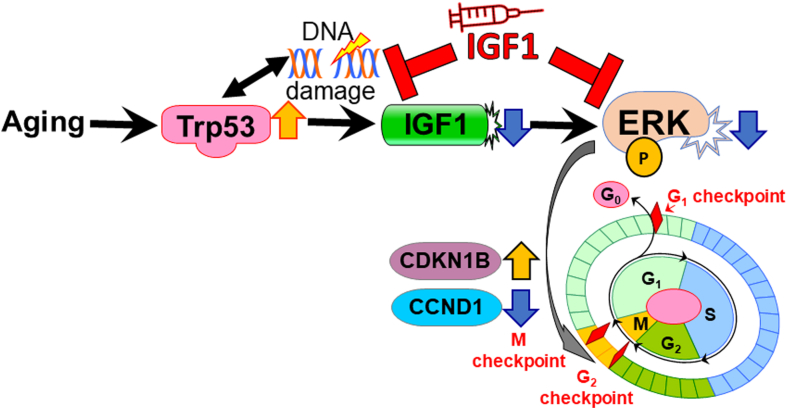

Loss of ICC and impaired gastric compliance are the 2 most common features of gastric aging.2,5,10,11,32,33 Previously, we linked the aging-associated overactive Trp53 to persistent ICC-SC cell-cycle arrest, which plays important roles in the decrease of ICC with age.11 In this study, we identified a decrease of IGF1 with age as a key trigger of ICC-SC depletion and furthermore that IGF1 reduction is the result of Trp53-induced DNA damage. The mechanism of the age-associated IGF1 decrease is corroborated by 2 previous in vivo studies using overexpressing Trp53 mice and a mitomycin-induced DNA damage model.31,34 Here, we suggest IGF1 treatment as a potential pharmacologic approach to restore gastric ICC/ICC-SC depletion and gastric dysfunction with age. Furthermore, we offer a potential mechanism understanding of the therapeutic effect of IGF1 as described earlier and as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanisms of IGF1 mediated prevention of aging-associated ICC-SC decline. During aging, increased Trp53 reduces IGF1 in part by accumulating DNA damage. Reduced IGF1 inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation (P), leading to ICC-SC growth arrest by increasing CDKN1B and decreasing CCND1. IGF1 supplementation mitigates the ICC-SC decline by restoring reduced ERK phosphorylation and preventing DNA damage accumulation.

Age-dependent organ dysfunction is closely associated with reduced regenerative potential of tissue-resident stem cells.26 This process is termed stem cell aging and proposed as one of the central players in the entire aging process.26,27,35 Indeed, our previous work supports this stem cell aging concept by showing that the ICC-SC decline with age is a key to ICC loss and associated gastric dysfunction.11 The tumor-suppressor Trp53 protein induced ICC-SC cell-cycle arrest via suppression of the ERK signaling pathway.11 Based on these findings, activation of ERK might be one of the potential targets for rejuvenation of aged ICC-SC. Indeed, supplementation of IGF1, an important growth hormone that is reduced with age in human beings and mice as shown in Figure 1, restored reduced ICC-SC in klotho mice by activating the ERK signaling pathway. The effect of IGF1 on ICC-SC is corroborated by ex vivo organotypic culture and in vitro ICC-SC culture studies showing IGF1 also could restore nutlin 3a–induced reduced ICC-SC proliferation by activating ERK signaling.

Organ aging is accompanied by DNA damage accumulation and DNA damage could impact stem cells during aging.27 As we have shown previously, Trp53-induced DNA damage accumulation is critical in ICC-SC depletion with age.11 In this study, we found LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment prevented DNA damage accumulation in the stomachs of klotho mice and the effect of the LONG R3 rhIGF1 effect was corroborated by in vitro (ICC-SC line) and ex vivo (organotypic culture) experiments showing that rhIGF1 treatment prevented Trp53-induced DNA damage accumulation. Similar to this study, a recent report also showed that in ex vivo culture IGF1 stimulation of middle-aged hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) decreased DNA damage accumulation via activation of IGF1 receptors and expanded functional HSCs.19 Although the precise mechanism of the effect of IGF1 on DNA damage remains unknown and warrants further investigation, one possible explanation, as previously proposed,36,37 might be that IGF1 restores old niche cells because the lack of production of growth or survival factors from niche cells negatively impacts stem cell numbers and function.

In this study, we found that LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment seems to result in improved overall appearance, increased body weight, and an extended lifespan of klotho mice. The role of IGF1 on longevity remains controversial and complicated owing to contrasting results from different studies. A recent meta-analysis showed a U-shaped relationship between serum IGF1 concentration and mortality,20 and this study indicated an optimal level of IGF1 seems to be important for preventing morbidities associated with either high IGF1 states including cancer, oxidative stress, or low IGF1 states such as cardiovascular disease, insulin insensitivity, neurodegenerative disease, and osteoporosis.16 Importantly, a direct link between high food intake, high IGF1 levels, and high mortality no longer was observed in individuals older than age 65 years,20 and this finding is consistent with previous reports that linked low dietary intake to increased cancer mortality and overall mortality in individuals older than age 65 years.6,20 In this study, we found that a 3-week treatment with LONG R3 rhIGF1 significantly extended the lifespan of klotho mice. This finding is consistent with a previous report showing that IGF1 infusion extended the lifespan of zinc metallopeptidase STE24– (gene encoding metalloproteinase involved in prelamin A) deficient mice displaying human progeroid syndromes.38 However, further investigation of the role of IGF1 in the longevity of wild-type mice is warranted because the lifespans of klotho and zinc metallopeptidase STE24–deficient mice are shorter than WT mice. In addition, a potential link between improved food intake and lifespan remains unclear because there are many discrepant reports in mice and human beings.6,8,39

Using the transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing technique, a recent study found that IGF1 stimulation increases chromatin accessibility of middle-aged mouse HSCs to activate the transcriptional program of mitochondrial function, metabolism, and cell cycle, leading to rejuvenation of their impaired functions.19 Although the current study also showed that IGF1 treatment confers beneficial effects of nutlin 3a–induced ICC-SC cell-cycle arrest, epigenetic alteration of ICC-SC during aging remains unclear. Further studies are needed to identify these effects because epigenetic alterations are reversible using drugs currently in use and in clinical trials.29,40

A limitation of our study was that most of the in vivo studies were performed in progeric klotho mice that display a shortened lifespan. A high IGF1 level is a risk factor for most common types of cancers and can lead to high mortality rates.41 Because of the short lifespan of klotho mice, it is not possible to study the tumorigenesis of IGF1 in these mice. Therefore, we cannot conclude that IGF1 treatment has beneficial effects on aging without increasing cancer risk in elderly individuals, and further detailed studies of these potential side effects are warranted.

In this study, we found that the age-related ICC-SC/ICC decrease can be countered by the IGF stimulation of the ERK signaling pathway. These effects of in vivo LONG R3 rhIGF1 are corroborated by ex vivo (organotypic culture) findings showing that rhIGF1 mitigated nutlin 3a–induced ICC depletion by preventing DNA damage accumulation. Restoration of ICC-SC/ICC by LONG R3 rhIGF1 led to improved gastric compliance, reduced food intake, and body weight gain of klotho mice. LONG R3 rhIGF1 treatment also extended the lifespan of klotho mice. These findings suggest that improved gastric function might affect the lifespan of klotho mice, which remains to be verified experimentally in more detail. In conclusion, we identify potential pharmacologic-targetable therapeutic approaches to restore gastric motor function that decreases with age. This study also might explore the novel concept that improving gastric motor functions might be an important therapeutic strategy to combat aging-associated disorders/diseases, improve quality of life, and increase longevity. Further definitive experiments are warranted to explore a potential link between gastric function and longevity.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

De-identified normal gastric corpus tissues were collected from nondiabetic patients aged 26–60 years undergoing bariatric surgery for medically complicated obesity (Institutional Review Board protocol 13-008138) and a nondiabetic 82-year-old patient undergoing gastrointestinal stromal tumor surgery (Institutional Review Board protocol 622-00). Studies on these tissues have not been reported previously. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocols were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (A48315).

Human Tissue Preparation

Full-thickness gastric tissues were obtained from both male and female nondiabetic patients. Pieces of gastric tunica muscularis were prepared by cutting away the mucosa and submucosa as described previously for mouse tissues.28 After removal, pieces of gastric tunica muscularis were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Animals

Homozygous klotho mice hypomorphic for α-Klotho and age-matched WT littermates (both sexes) were obtained from our heterozygous breeders and their genotype was verified by polymerase chain reaction as reported previously.10,11,23,42 The klotho mice were a generous gift from Dr Makoto Kuro-o and Dr Ming-Chang Hu (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX).

For gastric IGF1 protein expression by WB, experiments with klotho mice were performed between 60 and 70 days of age. Male 22- to 24-month-old and 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were killed by CO2 inhalation anesthesia or by decapitation performed under deep isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare) inhalation anesthesia. Gastric corpus + antrum muscles were prepared as described.28 C57BL/6J mice aged 12–14 days were obtained from our breeder pairs purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

Animal Experiments

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sex, age, genetic background, and numbers of animals, as well as methods of euthanasia are specified in the main text. Controls for genetically modified mice (klotho) were WT littermates co-housed with their mutant siblings. None of the mice were used in any previous experiments. Mice were housed at a maximum of 5 per cage using an Allentown, Inc (Allentown, NJ), reusable static caging system in the Mayo Clinic Department of Comparative Medicine Guggenheim Vivarium under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Bedding material was irradiated one-quarter inch corn cob with the addition of Bed-r’Nest (4 g; The Andersons, Inc, Maumee, OH) irradiated paper-twist nesting material as enrichment. Mice were kept on an irradiated PicoLab 5058 Mouse Diet 20 (≥20% protein, ≥9% fat, ≤4% fiber, ≤6.5% ash, and ≤12% moisture; LabDiet, Inc, St. Louis, MO). Food and water were available ad libitum. Before gastric compliance studies, mice were fasted overnight in a metabolic cage with free access to water. Animals were handled during the light phase.

Gastric Compliance

Ex vivo gastric compliance was determined according to previously described approaches11,43, 44, 45 with minor modifications. Briefly, intact stomachs were excised, placed in a heated water bath, and connected via the esophagus to a syringe pump (Model 975 Compact Infusion Pump; Harvard Apparatus, Ltd, Cambridge, MA) and a pressure transducer (MP100A-CE; BIOPAC Systems, Inc, Goleta, CA; amplifier: Transbridge 4M; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) through the pylorus. The stomachs then were filled with Krebs solution46 (37°C) to 1 mL at a rate of 100 μL/min for 10 minutes while recording pressure using ClampFit 10.7.0 software (Molecular Devices, LLC, San Jose, CA).

LONG R3 Recombinant Human IGF1 Treatment

The klotho mice received twice-daily intraperitoneal injections of LONG R3 recombinant human IGF1 (a potent IGF1 analog with reduced IGF-binding protein affinity, 150 μg/kg15; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in 100 mmol/L acetic acid (R&D Systems) for 3 weeks. The same amount of acetic acid vehicle (100 mmol/L) was injected as a control for IGF1 treatment. IGF1 or vehicle injections were initiated when the mice were 6–7 weeks old (ie, when klotho mice began to display a wide array of premature aging phenotypes), which lead to their death at approximately 70 days of age.23

Serum IGF1 Measurement

Blood samples were taken from the submandibular vascular bundle of male C57BL/6J mice between 2 and 24 months of age. Serum IGF1 was measured by the RayBio Mouse IGF1 ELISA Kit from RayBiotech (Peachtree Corners, GA).

ICC-SC Line

Isolation and maintenance of the murine ICC-SC cell lines D2211B were described previously and were a generous gift from Dr Tamas Ordog (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).17 Only cells with diploid DNA content and lacking expression of the temperature-sensitive, tsA58-mutant SV40 large T antigen were used.17 In this study, D2211B cells were cultured with Medium 199 with phenol red supplemented with 1% antibiotic–antimycotic, 1% L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech, Inc, Woodland, CA).

Cell Cultures and rhIGF1 Treatment

To examine the effects of rhIGF1 on nutlin 3a–induced ICC-SC growth arrest,11 D2211B cells were treated with 30 μmol/L nutlin 3a in combination with 100 ng/mL rhIGF1. The medium containing agents were changed every day for 3 days.

Assay of Cell Viability of ICC-SC

Three thousand cells per well were plated in complete media in 96-well, flat-bottom plates. After 72 hours, cells were incubated as indicated. Viable cell counts were evaluated by MTS assay (CellTiter 96 AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay; Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

WB

Tissue and cell lysates were prepared and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting as described previously15 (see antibodies in Table 1). Target and reference proteins were detected simultaneously using LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE) secondary antibodies tagged with near-infrared and infrared fluorescent dyes (IRDye700, red pseudocolor; IRDye800CW, green pseudocolor). Blots were visualized using an Odyssey XF Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified using LI-COR Image Studio version 5.0.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used in WB Studies

| Target | Supplier | Host | Clone/ID | Isotype/lot number | Label | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | LI-COR | Mouse mAb | 926-42212 | IgG2b | 1:10,000 | |

| ACTB | LI-COR | Rabbit mAb | 926-42210 | IgG | 1:10,000 | |

| ANO1 | CST (Beverly, MA) | Rabbit mAb | D1M9Q | IgG/1 | 1:2000 | |

| CCND1 | CST | Rabbit pAb | 2922 | 7 | 1:1000 | |

| CDKN1B | BD | Mouse mAb | 57/Kip1/p27 | IgG1 | 0.125 μg/mL | |

| ERK1/2 | CST | Mouse mAb | 3A7 | IgG1 | 1:4000 | |

| ETV1 | Abcam (Cambridge, MA) | Rabbit pAb | Ab81086 | IgG/GR12174-15 | 0.5 μg/mL | |

| IGF1 | CST | Rabbit mAb | 73034 | IgG | 1:2000 | |

| KIT | R&D Systems | Goat pAb | AF1356 | IgG/IEO0217101 | 0.2 μg/mL for mice | |

| KIT | DAKO (Carpinteria, CA) | Rabbit pAb | A4502 | 100428020A | 1:4000 for human beings | |

| KITL | AbD Serotec | Rabbit pAb | AAM50 | IgG | 0.2 μg/mL | |

| P-ERK1/2 (202Y204 and T185/T187) | CST | Rabbit mAb | 197G2 | IgG | 1:1500 | |

| Secondary Ab: anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | LI-COR | Donkey pAb | #926-32223 | C90821-03 | IRDye 680 | 1:10,000 |

| Secondary Ab: anti-mouse IgG (H+L) | LI-COR | Donkey pAb | #926-32222 | C71204-03 | IRDye 680 | 1:10,000 |

| Secondary Ab: anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | LI-COR | Donkey pAb | #926-32213 | C70918-03 | IRDye 800CW | 1:10,000 |

| Secondary Ab: anti-goat IgG (H+L) | LI-COR | Donkey pAb | #926-32214 | C80207-07 | IRDye 800CW | 1:10000 |

Ab, antibody; ACTB, actin beta; H+L, highly cross-adsorbed; mAb, monoclonal antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody; P-ERK1/2, P-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2.

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

Whole mounts of freshly dissected intact gastric tunica muscularis tissues were processed using established techniques.24 Briefly, tissues were fixed with cold acetone (10 minutes) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). ICCs were detected with goat polyclonal antimurine KIT antibodies and rabbit polyclonal anti-ANO1 antibodies (72 hours at 4°C) (see Table 2 for detailed antibody information). Bound antibodies were detected with Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-goat and Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG (24 hours at 4°C) (see Table 2 for detailed antibody information). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at room temperature for 30 minutes. Whole-mount images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a 40× oil objective lens at a resolution of 212.3 × 212.3 × 0.21 μm per pixel and Zeiss Zen software (2012 SP1 black edition).

Table 2.

Antibodies Used in Mouse Immunohistochemistry Studies

| Target | Supplier | Host | Clone/ID | Isotype/lot number | Label | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANO1 | Abcam | Rabbit pAb | ab53212 | IgG/GP3295656-1 | 1:1500 | |

| KIT | R&D Systems | Goat pAb | AF1356 | IgG/IEO0217101 | 0.2 μg/mL | |

| Secondary Ab: anti-rabbit IgG | Life Technologies (Grant Island, NY) | Chicken pAb | A21441 | 1697089 | AF488 | 5 μg/mL |

| Secondary Ab: anti-goat IgG | Life Technologies | Chicken pAb | A21468 | 2318436 | AF594 | 5 μg/mL |

Ab, antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody

Multiparameter Flow Cytometry

Murine gastric KIT+CD44+CD34− ICC and KITlowCD44+CD34+ ICC-SC were enumerated using previously published and established protocols and reagents (Table 3 for antibodies).17,28 Samples were analyzed by using a Becton Dickinson LSR II flow cytometer (Table 4 for configuration) and FlowJo software (Treestar).

Table 3.

Antibodies Used for Flow Cytometry Analysis of Cells Freshly Dissociated From Murine Gastric Muscles

| Target | Supplier | Host/source | Clone/ID | Isotype | Label | Final concentration or μg/106 cellsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD16/32b | eBioscience (San Diego, CA) | Rat mc | 93 | IgG2a, λ | 1 μg | |

| CD11bc | eBioscience | Rat mc | M1/70 | IgG2b, κ | PE-Cy7 | 0.0312 μg |

| CD45 | eBioscience | Rat mc | 30-F11 | IgG2b, κ | PE-Cy7 | 0.0312 μg |

| F4/80 | eBioscience | Rat mc | BM8 | IgG2a, κ | PE-Cy7 | 0.0625 μg |

| CD44 antigen | BioLegend (San Diego, CA) | Rat mc | IM7 | IgG2b, κ | APC-Cy7 | 0.0625 μg |

| KIT | eBioscience | Rat mc | ACK2 | IgG2b, κ | APC | 5 μg/mL |

| KIT | eBioscience | Rat mc | 2B8 | IgG2b, κ | APC | 0.25 μg |

| CD34 antigen | eBioscience | Rat mc | RAM34 | IgG2a, κ | eFluor 450 or FITC | 0.2 μg |

APC, allophycocyanin; Cd45, protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C; Cy7, cyanine 7; mc, monoclonal; F4/80, epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like sequence 1; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

Amount added to 100 μL staining volume.

Cd16: Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity III; Cd32: Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity IIb.

Cd11b, integrin α M.

Table 4.

Configuration of the Becton Dickinson LSR II Flow Cytometer

| Laser | Excitation wavelength | Dichroic filter | Emission filter, nm (peak/bandwidth) | Detector type | Light scatter or fluorochromes used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coherent Sapphire 20 mW (BD biosciences) | 488 | Photodiode | Forward scatter | ||

| 488/10 | PMT | Side scatter | |||

| 505 LP | 530/30 | PMT | FITC | ||

| 550 LP | 575/26 | PMT | PE | ||

| 595 LP | 610/20 | PMT | Unused | ||

| 685 LP | 695/40 | PMT | Beads | ||

| 735 LP | 780/60 | PMT | PE-Cy7 | ||

| Coherent CUBE 100 mW (BD biosciences) |

407 | 450/50 | PMT | eFluor 450 | |

| 505LP | 525/50 | PMT | Unused | ||

| 535 LP | 590/40 | PMT | Unused | ||

| 595 LP | 610/20 | PMT | Unused | ||

| 630 LP | 670/30 | PMT | Unused | ||

| 670 LP | 710/50 | PMT | Unused | ||

| Coherent CUBE 40 mW (BD biosciences) |

640 | 660/20 | PMT | APC | |

| 685 LP | 712/20 | PMT | Beads | ||

| 735 LP | 780/60 | PMT | APC-Cy7 |

APC, allophycocyanin; Cy7, cyanine 7; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; LP, long pass; PE, phycoerythrin; PMT, photomultiplier tube.

Analysis of ICC-SC Proliferation by 5-EdU Incorporation and PI Labeling and Flow Cytometry

The Click-iT Edu Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as described previously with minor modifications.11,47 Briefly, EdU was added to cell culture medium to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L for 120 minutes. After a wash, cells were harvested, pelleted at 500 × g for 5 minutes, and fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature with Click-iT fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing and centrifugation, the cells were permeabilized with Click-iT saponin-based permeabilization buffer and incubated with 500 μL Click-iT reaction cocktail containing the Alexa Fluor 647 fluorochrome for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After a wash with the Click-iT permeabilization buffer, the cells were incubated with 20 mg/mL ribonuclease A and PI staining solution (50 μg/mL) for 45 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Samples were analyzed with a Becton Dickinson LSR II flow cytometer and FlowJo software (Treestar).

Organotypic Culture Studies

Intact gastric corpus + antrum tunica muscularis tissues from 12- to 14-day-old C57BL/6J mice were cultured with serum- and growth factor–free Medium 199 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% antibiotic–antimycotic, 1% L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described previously.15,17 Gastric tunica muscularis organotypic cultures were maintained for up to 3 days and fresh media containing nutlin 3b, nutlin 3a, and nutlin 3a + rhIGF1 were changed once a day. Tissues were harvested and used for WB and whole-mount staining, and cultured media were used for ELISA.

Materials

Nutlin 3a and nutlin 3b were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Dimethyl sulfoxide and TritonX-100 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and Tween20 was from Bio-Rad laboratories (Hercules, CA). LONG R3 rhIGF1 and rhIGF1 were from R&D Systems. 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mountant were from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Statistical Analyses

Data were expressed as means ± SD. Each graph contains an overlaid scatter plot showing all independent observations. The n in the figure legends refers to these independent observations. The statistical significance of survival curves was analyzed with the log-rank test. All other statistical analyses were performed by nonparametric methods including the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test and Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance on ranks followed by appropriate post hoc tests. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Lowercase letters [a, b, c] shown in these figures indicate a significant difference between the groups as follows: groups not sharing the same letter are different at P < .05 by the all-pairwise post hoc listed in the legend. In some experiments involving multiple ages of subjects or drug concentrations, groups were only compared with the control after obtaining significant analysis of variance P values. In these instances, groups significantly different from the control are marked by an asterisk.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Vy Truong Thuy Nguyen (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal)

Negar Taheri, MD (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Egan L Choi (Data curation: Supporting)

Kellogg A Todd, MD (Resources: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

David R Linden, PhD (Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Yujiro Hayashi, PhD (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Supporting; Visualization: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK121766 (Y.H.), P30 DK084567 to the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic Center for Biomedical Discovery Pilot Award (Y.H.), and American Gastroenterology Association–Allergan Foundation Pilot Research Award in Gastroparesis (Y.H.). The funding agencies had no role in the study analysis or writing of the manuscript. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors.

References

- 1.Kennedy B.K., Berger S.L., Brunet A., et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen V.T.T., Taheri N., Chandra A., et al. Aging of enteric neuromuscular systems in gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34 doi: 10.1111/nmo.14352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilleri M., Cowen T., Koch T.R. Enteric neurodegeneration in ageing. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:418–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilleri M., Cowen T., Koch T.R. Enteric neurodegeneration in ageing. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:185–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker B.A., Chapman I.M. Food intake and ageing--the role of the gut. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine M.E., Suarez J.A., Brandhorst S., et al. Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population. Cell Metab. 2014;19:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couzin-Frankel J. Nutrition. Diet studies challenge thinking on proteins versus carbs. Science. 2014;343:1068. doi: 10.1126/science.343.6175.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seidelmann S.B., Claggett B., Cheng S., et al. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e419–e428. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30135-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirwan R., McCullough D., Butler T., et al. Sarcopenia during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions: long-term health effects of short-term muscle loss. Geroscience. 2020;42:1547–1578. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izbeki F., Asuzu D.T., Lorincz A., et al. Loss of Kitlow progenitors, reduced stem cell factor and high oxidative stress underlie gastric dysfunction in progeric mice. J Physiol. 2010;588:3101–3117. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi Y., Asuzu D.T., Bardsley M.R., et al. Wnt-induced, TRP53-mediated cell cycle arrest of precursors underlies interstitial cell of Cajal depletion during aging. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;11:117–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns A.J., Lomax A.E., Torihashi S., et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12008–12013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuro-o M. Klotho and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roith D. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Insulin-like growth factors. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:633–640. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702273360907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi Y., Asuzu D.T., Gibbons S.J., et al. Membrane-to-nucleus signaling links insulin-like growth factor-1- and stem cell factor-activated pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J., Anzo M., Cohen P. Control of aging and longevity by IGF-I signaling. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardsley M.R., Horvath V.J., Asuzu D.T., et al. Kitlow stem cells cause resistance to Kit/platelet-derived growth factor alpha inhibitors in murine gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:942–952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzenberger M., Dupont J., Ducos B., et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young K., Eudy E., Bell R., et al. Decline in IGF1 in the bone marrow microenvironment initiates hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:1473–1482 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahmani J., Montesanto A., Giovannucci E., et al. Association between IGF-1 levels ranges and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Aging Cell. 2022;21 doi: 10.1111/acel.13540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinciguerra M., Santini M.P., Martinez C., et al. mIGF-1/JNK1/SirT1 signaling confers protection against oxidative stress in the heart. Aging Cell. 2012;11:139–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SanMiguel J.M., Young K., Trowbridge J.J. Hand in hand: intrinsic and extrinsic drivers of aging and clonal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 2020;91:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2020.09.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuro-o M., Matsumura Y., Aizawa H., et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horvath V.J., Vittal H., Lorincz A., et al. Reduced stem cell factor links smooth myopathy and loss of interstitial cells of Cajal in murine diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:759–770. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvath V.J., Vittal H., Ordog T. Reduced insulin and IGF-I signaling, not hyperglycemia, underlies the diabetes-associated depletion of interstitial cells of Cajal in the murine stomach. Diabetes. 2005;54:1528–1533. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi D.J., Jamieson C.H., Weissman I.L. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunet A., Goodell M.A., Rando T.A. Ageing and rejuvenation of tissue stem cells and their niches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:45–62. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00510-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorincz A., Redelman D., Horvath V.J., et al. Progenitors of interstitial cells of Cajal in the postnatal murine stomach. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1083–1093. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syed S.A., Hayashi Y., Lee J.H., et al. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2018. Ezh2-dependent epigenetic reprogramming controls a developmental switch between modes of gastric neuromuscular regulation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dave M., Hayashi Y., Gajdos G.B., et al. Stem cells for murine interstitial cells of Cajal suppress cellular immunity and colitis via prostaglandin E2 secretion. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:978–990. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gatza C.E., Dumble M., Kittrell F., et al. Altered mammary gland development in the p53+/m mouse, a model of accelerated aging. Dev Biol. 2008;313:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomez-Pinilla P.J., Gibbons S.J., Sarr M.G., et al. Changes in interstitial cells of Cajal with age in the human stomach and colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips R.J., Powley T.L. Innervation of the gastrointestinal tract: patterns of aging. Auton Neurosci. 2007;136:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niedernhofer L.J., Garinis G.A., Raams A., et al. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature. 2006;444:1038–1043. doi: 10.1038/nature05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh J., Lee Y.D., Wagers A.J. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Med. 2014;20:870–880. doi: 10.1038/nm.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maity P., Singh K., Krug L., et al. Persistent JunB activation in fibroblasts disrupts stem cell niche interactions enforcing skin aging. Cell Rep. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang B., Wu X., Meng F., et al. Progerin modulates the IGF-1R/Akt signaling involved in aging. Sci Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marino G., Ugalde A.P., Fernandez A.F., et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 treatment extends longevity in a mouse model of human premature aging by restoring somatotroph axis function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16268–16273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002696107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solon-Biet S.M., McMahon A.C., Ballard J.W., et al. The ratio of macronutrients, not caloric intake, dictates cardiometabolic health, aging, and longevity in ad libitum-fed mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19:418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim K.H., Roberts C.W. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:128–134. doi: 10.1038/nm.4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Key T.J. Diet, insulin-like growth factor-1 and cancer risk. Proc Nutr Soc Published online May. 2011;3 doi: 10.1017/S0029665111000127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asuzu D.T., Hayashi Y., Izbeki F., et al. Generalized neuromuscular hypoplasia, reduced smooth muscle myosin and altered gut motility in the klotho model of premature aging. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:e309–e323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hennig G.W., Brookes S.J., Costa M. Excitatory and inhibitory motor reflexes in the isolated guinea-pig stomach. J Physiol. 1997;501:197–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.197bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi T., Owyang C. Characterization of vagal pathways mediating gastric accommodation reflex in rats. J Physiol. 1997;504:479–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.479be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dixit D., Zarate N., Liu L.W., et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal and adaptive relaxation in the mouse stomach. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G1129–G1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00518.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi Y., Toyomasu Y., Saravanaperumal S.A., et al. Hyperglycemia increases interstitial cells of Cajal via MAPK1 and MAPK3 signaling to ETV1 and KIT, leading to rapid gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:521–535 e20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi Y., Bardsley M.R., Toyomasu Y., et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha regulates proliferation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells with mutations in KIT by stabilizing ETV1. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:420–432 e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]