Abstract

Background

We sought to identify what matters to older adults (60 years and older) presenting to the emergency department (ED) and the challenges or concerns they identify related to medication, mobility, and mentation to inform how the 4Ms framework could improve care of older adults in the ED setting.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted using the 4Ms to identify what matters to older adults (≥60 years old) presenting to the ED and what challenges or concerns they identify related to medication, mobility, and mentation. We conducted semi‐structured interviews with a convenience sample of patients in a single ED. Interview guide responses and interviewer field notes were entered into REDCap. Interviews were reviewed by the research team (2 coders per interview) who inductively assigned codes. A codebook was created through an iterative process and was used to group codes into themes and sub‐themes within the 4Ms framework.

Results

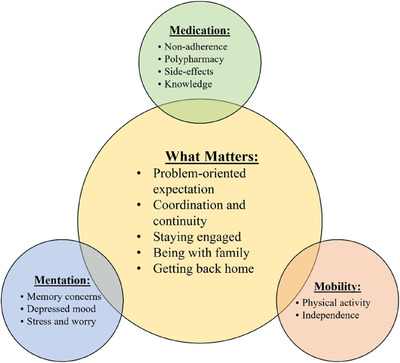

A total of 20 ED patients participated in the interviews lasting 30–60 minutes. Codes identified for “what matters” included problem‐oriented expectation, coordination and continuity, staying engaged, being with family, and getting back home. Codes related to the other 4Ms (medication, mobility, and mentation) described challenges. Medication challenges included: non‐adherence, side effects, polypharmacy, and knowledge. Mobility challenges included physical activity and independence. Last, mentation challenges included memory concerns, depressed mood, and stress and worry.

Conclusions

Our study used the 4Ms to identify “what matters” to older adults presenting to the ED and the challenges they face regarding medication, mobility, and mentation. Understanding what matters to patients and the specific challenges they face can help shape and individualize a patient‐centered approach to care to facilitate the goals of care discussion and handoff to the next care team.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Adults aged 65 and older accounted for 16.8% of the population or approximately 54 million people in the United States in 2021. 1 This population is expected to continue increasing such that the number of adults aged 65 and older is projected to reach over 80 million by 2050. 2 Older adults tend to carry multiple comorbid conditions, which are often complicated by social determinants of health and declining cognitive and functional status. 3 , 4 Delivery of high‐quality geriatric care is particularly challenging in the emergency department (ED) setting. Older adults comprise approximately 20% of ED visits annually, which amount to over 23 million ED visits per year in the United States. 3 Given the complexity of their care, older adults are at higher risk of poor outcomes 3 such as disability and death. As a result, older adults consume more resources in terms of diagnostic tests and procedures and are at greater risk for adverse outcomes including longer stay, return ED visits within 30 days, hospitalizations, functional decline, and nursing home admissions. 5 , 6 , 7

1.2. Importance

The Age‐Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) initiative, which arose from the partnership of the John A. Hartford Foundation, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and American Hospital Association, developed the 4Ms framework to improve outcomes of older adults across care settings by using an evidenced‐based, person‐centered approach. 9 The 4Ms framework focuses on 4 evidence‐based priorities of geriatric care: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility. What matters is the starting point of the 4Ms framework and focuses on older adults’ goals in their life and health care to provide care consistent with their priorities. Medication aims to address issues with polypharmacy and avoid high‐risk medications. Mentation refers to mood and memory, with specific attention to depression, dementia, and delirium. Mobility includes assessment of ambulation, functional status, and fall risk. The 4Ms framework is intended to be incorporated broadly throughout US hospitals and health systems. 9 Currently the 4Ms are being implemented in primary care 10 and both ambulatory and acute care settings.

The Bottom Line

In the context of an emergency department (ED) visit, older adults report "what matters" to them is addressing the medical issue at hand, care coordination, staying engaged, being with family, and getting back home. The concordance between patient and health care professionals is the main concern for the ED visit and was 82% but 15% on goals of care.

However, there is currently limited evidence regarding how to implement the 4Ms in the ED, including what matters to older adults presenting to the ED and common challenges or concerns related to medication, mentation, and mobility. It is important to learn the goals of care of older adults and the challenges they face to improve their clinical course, avoid unnecessary or unwanted care, and reduce the rate of adverse outcomes. One recent qualitative study identified themes regarding “what matters” to older adults in the ED, with attention to the feasibility of 4Ms implementation in the ED. 11 Our study attempts to expand on this work by including a focus on challenges regarding medications, mentation, and mobility from the perspective of the older person.

1.3. Goals of this investigation

Our objective was to identify what matters to older adults (60 and older) presenting to the ED and the challenges or concerns they identify related to medication, mobility, and mentation. We conducted a qualitative descriptive study using semi‐structured interviews with older ED patients and their caregivers.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview of study design

We used a qualitative descriptive approach to analyze semi‐structured interviews focused on what matters to older patients in a single academic ED and their challenges and concerns related to medication, mobility, and mentation. Our ED is currently implementing policies and procedures of an AFHS. We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist. The University of Iowa institutional review board approved this study.

2.2. Theoretical framework

Consistent with a directed approach to qualitative descriptive research, we analyzed data for themes and sub‐themes within an existing framework. 12 , 13 Specifically, we used framework analysis to organize themes and sub‐themes into the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility. 14 This framework was chosen as an ideal framework to understand the goals of care and challenges of older adults because of its focus on evidence‐based priorities of geriatric care.

2.3. Participants and sampling

Over a 6‐month period, we recruited a convenience sample of adults 60 years and older seeking care in the ED during weekdays, evenings, and weekends. The age limit was expanded to 60 to broaden the inclusion. Older adults in the ED were approached, provided with a brief description of the 4Ms and purpose of the interview, and asked to voluntarily participate in the interview. After obtaining informed verbal consent, we conducted the interview in the ED. We included patients in stable condition with decision‐making capacity per their treatment provider. In cases where family or caregivers were present, they were allowed to share their understanding of the patient's goals or challenges with the patient's consent. Caregivers and family were included to provide additional details regarding the older person's home life and support system.

2.4. Data collection

Two medical students (M.S. and M.M.) were trained by the principal investigator (S.L.) to conduct semi‐structured interviews using an interview guide developed by the research team (Appendix S1). Creation of the interview guide was based on an existing 4Ms worksheet with additional questions to meet our objectives. Interviews took place in ED patient examination rooms. The timing of the interviews varied but they usually occurred after an initial evaluation by the treating provider and before disposition. During the interview, the patients were first asked introductory, open‐ended questions about their visit to orient the interviewer and establish rapport. Next, patients were asked about the 4Ms in addition to their main concerns and goals of care regarding their ED visit. The interviews lasted 30–60 minutes, and data were electronically recorded into REDCap 15 immediately following the interview. In addition to the interview guide, the interviewer recorded field notes, and participants were asked to report their age and sex. Field notes included observations of the environment and interactions between the patient, care partner, and clinicians. After the patient interview, the patient's provider was interviewed about their perception of the patient's goals of care and how those goals were elicited during patient assessment.

2.5. Analysis

Consistent with a qualitative descriptive approach, the interview data were analyzed using an iterative process, wherein data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously. 16 Two research team members reviewed each interview and assigned codes. During regular meetings, coders shared their individual coding, and the team (M.S., M.M., D.L., and S.L.) discussed any discrepancies and developed a codebook containing the codes and the definitions of each code (Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or majority vote when necessary. Framework analysis 14 was then used to develop and categorize the codes within the 4Ms framework. Codes were refined and similar codes grouped and abstracted to develop sub‐themes and themes to describe the data. The team discussed the thematic structure to determine that themes were distinct and fully developed. The team also discussed whether any developing themes or sub‐themes did not fit within the 4Ms framework, but there were none. Data collection continued until no new data relevant to the main study questions were emerging.

2.6. Rigor

The research team included multiple perspectives (medical students, nurse researchers, and ED physicians), enhancing the rigor of the study 17 and reducing individual bias. The data from each interview were independently reviewed by 2 members of the team. The final codebook was developed through an iterative process involving team discussion and consensus. Interviews were not recorded due to feasibility constraints. However, the interviewers noted responses using the participants’ own words where possible and entered the data into REDcap immediately following the interview.

3. RESULTS

We approached a total of 21 patients in the ED to participate in this study. One patient declined and 20 completed interviews. Participants ranged from 60 to 92 years of age and 11 (55%) were female (Table 1). Family and/or caregivers were present for 6 of 20 participant interviews.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics

| Demographic category | Demographic data, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participating patients | 20 |

| No. of female patients | 11 (55) |

| No. of male patients | 9 (45) |

| Age range, years | 60–92 |

| Mean age, years | 72 |

| No. with caregivers | 6 (30) |

Specific observations about environment and interactions were used as context from which to understand participant data and development of themes. The subject enrollment and data collection were completed as thematic saturation was achieved.

Themes were developed within each aspect of the 4Ms framework (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Themes of what matters and challenges or concerns related to medication, mobility, and mentation for older adults in the emergency department

3.1. What matters

Participants often presented to the ED in the context of a problem‐oriented visit, whether from an acute event (eg, fall) or concerns formed over time. They hoped to receive a diagnosis and treatment consistent with their care goals. However, motivations and factors driving their care goals and when to seek care appeared rooted in what matters to them. What matters included 5 themes: problem‐oriented expectation, coordination and continuity, staying engaged, being with family, and getting back home (Table S1). Overall, rates of concordance between patient and provider on the main concern for ED visit and underlying goals of care were 82.35% and 15.38%, respectively.

Participants described addressing a problem‐oriented expectation as an aspect of what matters to them. One participant (participant 7) shared that what matters most to her is that she gets her gallbladder out, so she is not sick anymore. Another participant (participant 15) came in with an expectation to address his abdominal pain and was most worried that whatever was causing his abdominal pain would “slow him down” and keep him from his active lifestyle. Participants described the importance of diagnosis and/or screening, which we classified as a sub‐theme under a problem‐oriented expectation. This fits the care environment because most primary problems in the ED are acute in nature. Diagnosis and/or screening mattered because participants wanted to either gain clarity on possible treatments or rule out concerning diagnoses: One participant (participant 7) was concerned that she had a myocardial infarction (MI) and hoped that was not the case.

Participants described coordination and continuity as a priority. It was described as a consistent patient‐ or provider‐driven collaboration within the multidisciplinary team. For example, the participant (participant 2) drove 1.5 hours away to receive care at this ED because the physicians knew her and her complex medical history.

Participants expressed the importance of staying engaged. In some ways, their illnesses limited their engagement in activities with their family or community. Participant 2, recently diagnosed with cancer, shared: “I want to live as long as I can [to stay engaged].” Participants also shared wanting to stay active as a priority, which we classified under staying engaged. They wanted to do physical activities, such as engaging in hobbies involving movement outdoors. This was often a challenge for individuals with chronic illnesses affecting their activity or mobility: participant 13 was worried that the consequences of her illness would keep her from walking her dog, kayaking, and playing sports like racquetball.

Participants described being with family as a theme‐related to what matters. It involved meaningful engagement with family, such as holiday gatherings and visiting children and grandchildren. For some, family was expressed as a reason to live longer. For example, for participant 17, spending time with his grandchildren was the most important thing, and he wanted to be able to live long enough to give his grandchildren fond memories of him.

Participants also described getting back home; they often wished to live at home as long as their health allowed. This was noted as especially important by participants who were previously unable to return home following hospitalizations or surgeries: participant 3 shared her biggest concern was getting home. She spent a few days in a nursing home recently and adamantly did not want to ever return to a nursing home.

3.2. Medication challenges

Problems with medications play a role in many ED visits for older adults. Side effects, polypharmacy, and non‐adherence were some issues identified by participants. Participants expressed interest in avoiding side effects, taking fewer medications, having easier schedules, and reducing the burden to keep up with daily medications (Table S2).

Participants exemplified non‐adherence challenges as they identified difficulty taking medications as prescribed. Taking prescription medications daily, or multiple times per day, seemed a significant burden, especially for those who led active lifestyles. Participant 1 stated, “Sometimes I get so busy I forget to take [medications]. When I realize, [I think] tomorrow is a new day, and I try to do better each day.” Some participants described receiving help with managing medications either from a caregiver or by using a tool such as a pillbox. This was considered an important strategy to mitigate difficulty managing daily medications. For example, participant 3 stated she has a pillbox to organize her medications and a daily routine for taking her medications as prescribed.

Participants described concerns about polypharmacy, being on more medications than desired. Often participants preferred to be on as few medications as possible. This led to participants attempting to de‐prescribe on their own, which could be potentially harmful and precipitate events leading to ED visits. Participant 5 has been prescribed a lot of medications, and he would like to be on as few meds as possible. He took it on himself to stop taking some of his meds and was off a lot of his medications when he fell, which is the reason that brought him to the hospital.

Participants also described concerns about side effects. They shared unexpected or undesirable effects due to their medication. For example, participant 12 recently had a change to his blood pressure medication and thinks this is related to his dizziness symptoms.

Participants described limitations in medication knowledge, such as not knowing the name of the medication, indication, and frequency. For instance, participant 14 was on 10–12 medications and was unsure of the names of most of them, what they were for, and when to take them. We classified blind trust as a sub‐theme for knowledge. Some participants blindly trusted the provider or family caregiver with medications. For example, participant 3 was not sure what each medication was for but was not concerned because she trusted that “doctors wouldn't prescribe something [she doesn't] need.”

3.3. Mobility challenges

Participants experienced challenges with mobility, resulting in limitations that could impair independence. The desire to maintain a level of independence and the ability to perform activities of daily living emerged as a strong theme among older adults. Some patients achieved this goal by using devices and attending rehab programs, whereas others remained limited by functional status (Table S3).

Participants described the importance of physical activity for reasons beyond enjoying the activity. Physical activity mattered to them as it was linked to independence. Participant 3 shared that they would like to stay active so they can continue to live independently. Participants also described functional mobility—wanting to maintain or improve functional mobility to accomplish tasks. For example, participant 12 had a job that involved working with his hands, and arthritis limited his ability to work. Rehabilitation was important for participants to maintain and regain functional status. For example, participant 8 stated he enjoys going to cardiac rehab 2–3 times a week after a previous MI; he feels he is getting a lot out of it and it will help him stay active.

Participants described independence as the desire to move and complete activities of daily living, with or without assisted devices. Participants often had to overcome limitations to maintain their independence. Participant 11 shared she needs oxygen to go out and has difficulty carrying the oxygen tank with her. She has knee pain, diabetic neuropathy, and an unsteady gait. Because of this, she says that she rarely goes out, which limits her opportunity to interact with others. Participants used devices or other types of support to overcome limitations. Participant 3 shared that she likes to be independent by cooking and leaving home but has some difficulty with these activities. She reported being unable to carry a pot of water to the stove from the sink, so she uses her walker to carry water. She cannot drive, so she needs to call for a ride any time she wants to leave her home. The utilization of services such as public or paid transportation has helped promote independence.

3.4. Mentation challenges

Participants reported concerns about memory and the development of dementia. Additionally, older adults reported suffering from stress and depressed mood that seems to tie back to themes of losing independence or the ability to do what matters. Other participants reported cultivating a positive outlook and engaging in activities that help them relax (Table S4).

Participants described memory concerns that ranged in severity. Participant 3 reported that she would sometimes have difficulty recalling names, and she also reported entering rooms and realizing that she had forgotten to bring her walker. Other participants expressed worry about developing dementia or cognitive impairment. Participant 20 worried about getting dementia or Alzheimer's; she mentioned that she used to work in research but recently began a new job last year because she had become unable to multitask.

Participants described depressed mood, often related to their declining functional status due to chronic illness. Participant 4 expressed feelings of anger and depression that he could not be as self‐sufficient anymore. This theme emerged in reaction to the burden of chronic comorbidity and the loss of activity level.

Participants reported stress and worry related to their lives or illnesses. Participant 16 described stress and worry related to her new cancer diagnosis. Some participants sought to retain a positive outlook by doing activities to cultivate positivity. Participant 18 stated that she most often has a positive attitude and considers herself a “pretty understanding person” despite the challenges she has faced. Other participants described the use of relaxation strategies: Participant 15 played golf, read, and watched sports to relax.

4. LIMITATIONS

The study has strengths in that we used a script during our semi‐structured interviews to maintain consistency between interviewers, but there is still potential for unintended influence due to variation in interviewer style. Our analytical approach aimed to mitigate bias by having 2 independent coders per interview. Also, we included detailed field notes so the research team would have rich contextual data for interpretation. We acknowledge the limitation of not recording interviews due to feasibility constraints. To enhance accuracy and level of detail, interviewers noted participant responses using their own words, where possible, and entered data in REDcap immediately following the interview. Transferability is somewhat limited due to degree of demographic data recorded and the study taking place in a single academic ED serving a Midwest patient population. However, this study is the first to examine all elements of the 4Ms as related to patient goals of care in the ED and provides a foundation for future research on the topic. Another potential limitation is whether timing of interviews during weekdays, evenings, or weekends influenced response. We believe this is beyond the scope of this article, but may be worth examining in future work.

5. DISCUSSION

This study provides an in‐depth description of what matters, unique challenges and opportunities regarding medication, mobility, and mentation, for older adults presenting to the ED. This study informs the implementation of the 4Ms framework in the ED. Our study findings address the knowledge gap in that we evaluated all 4Ms beyond what matters. The previous study by Gettel et al 11 evaluated “what matters” conversations in the ED. Kaldjian et al 18 identified several key themes for goals of care conversations in the palliative care setting using literature review. Ouchi et al 19 summarized the approaches to goals of care conversations in the ED. Our study findings indicate that what matters should be integrated into the other 4Ms because the remaining themes are integral to being able to do what matters. Themes identified in this study highlight the opportunities to address what matters and common challenges for older adults presenting to the ED using the 4Ms framework, which may serve as the framework for comprehensive geriatric assessment, for example.

We identified problem‐oriented expectation, coordination and continuity, staying engaged, being with family, and getting back home as what mattered to our participants. There are few studies using the 4Ms framework to investigate what matters to older adults in the ED setting. A literature review identified 6 categories describing the goals for the care of patients nearing the end of life, including being cured, living longer, improving or maintaining function and/or quality of life, and achieving life goals such as being with family and being home. 11 , 18 , 19 Several of our findings regarding what matters align well with previous categories. This suggests that what matters to older adults may be similar across clinical settings and stages of life and illness. Consequently, an understanding of what matters can be used to help shape a patient‐centered and individualized approach, regardless of clinical setting. Similar themes of what matters were identified in another study applying the 4Ms in the ED, including obtaining a diagnosis, reducing or resolving symptoms, maintaining self‐care and independence, and returning to the home environment. The ED visit can serve as an inflection point with the potential to change the trajectory of care to better align with patient priorities. However, best practices regarding conversations about what matters in the ED are not well understood. 19 Our results suggest the 4Ms as a useful framework, given its foundation in what matters to the older person, but further research is needed regarding the application and usability of the 4Ms framework in the ED setting.

We also identified non‐adherence, polypharmacy, side effects, and knowledge as medication challenges and concerns for participants. Medication harms, including adverse reactions, medication errors, and unintentional or intentional medication misuse, are estimated to result in 6.1 ED visits per 1000 population annually. 20 The same study showed population rates of ED visits for medication harms approximately double (12.1 vs. 5) for patients over 65 years and reported that 38.6% of ED visits for medication harms resulted in hospitalization. 20 We found that many patients had a lack of knowledge about their medications and had poor adherence, reflective of previous studies that have shown that, on average, patients are taking 3.8 more medications than self‐reported, and 31% are nonadherent. 21 Additionally, our participants expressed blind trust in providers and those helping with medications, which can reinforce the lack of medication knowledge and create missed opportunities for patients to voice concerns and engage in their care. Taken together, these factors can lead to an increased risk of prescribing potentially inappropriate medications and adverse drug events. Medication reconciliation by ED pharmacists significantly reduces medication discrepancies 22 and aids in reducing medication risk, but not all EDs have the advantage of pharmacists in the department. Our findings suggest that 4Ms conversations can elicit common concerns regarding medications contributing to medication harms and thus could be used to flag patients for detailed medication reconciliation.

Addressing and preventing memory concerns, depressed mood, and stress and worry were identified as mentation challenges and concerns. Memory concerns are relevant for delirium and dementia screening and can indicate potential challenges in the recall of discharge information. One study showed that approximately one‐fifth of older adults discharged from the ED could not state their diagnosis, and roughly half did not understand return precautions. 23 Communication breakdowns during discharge have the potential to contribute to adverse outcomes and repeat ED visits such as those suggested in a previous study where approximately 40% of older adults had repeat ED visits in 90 days, 30% were hospitalized, and 4% died. 23 Additionally, we found that many older adults expressed emotional stress and depressive symptoms, which can negatively impact cognition. 24 Conversely, others endorsed potential protective factors such as positive outlook and coping mechanisms such as relaxing. It is important to identify older adults with depressive symptoms as depression is a risk factor for cognitive decline, 25 impacts quality of life, and can contribute to isolation. Although the ED is often not the ideal setting for treating mood symptoms, patients with depression often present to the ED for help. 4Ms conversations can identify older adults with concerns about depression and stress, which can be used to connect them to the appropriate resources. Additionally, 4Ms conversations can reveal problems with memory that may be useful in ensuring the delivery of key clinical information and promoting cognitive screening in the ED.

We identified physical activity and independence as mobility challenges and concerns. Functional decline is often a reason older adults seek care in the ED. One study found that of older adults in the ED reporting a decline in activities of daily living, roughly 45% endorse that the functional decline contributed to their ED visit. 26 This is reflected in our results in that many patients expressed being limited by declining functional mobility in a way that interfered with doing what mattered. Additionally, some patients hoped to gain means of improving their functional status and to learn how to better care for themselves from their ED visit. Similar themes of patients’ desired outcomes, including maintaining self‐care and independence, gaining reassurance, and returning to the home environment, were reported in another 4Ms ED study. 11 Whereas this prior study identified outcomes desired by older adults, our study identified common concerns and challenges to achieving these outcomes from a patient perspective. By pairing patient concerns and desired outcomes using the 4Ms, it could be possible to identify patients at risk of declining functional status who would benefit from a focus on functional recovery in the ED and after discharge.

This study provides insights into patient factors that matter during AFHS implementation and how best to incorporate the 4Ms into the ED environment. This includes how we can use the goals of care and challenges identified in this study to inform care. There are some elements that intersect or connect across the 4Ms. For example, priorities of being with family and staying home potentially shape concerns about independence and memory loss, which could motivate a desire to stay active or increase stress and worry. The interplay between the 4Ms, such as medication being a culprit of delirium, an important component of mentation, could imply that EDs may need to be prepared for more comprehensive care for older adults. Future research could examine how these elements are linked across the 4Ms to deepen the understanding and utility of the framework. It is also important to consider challenges present when what matters to an older person is not consistent with their functional ability or health. We think that the collection of qualitative information about 4Ms from older ED patients can help to enhance the care of older adults in the ED. This may be done to understand their needs on entering the ED, or plan their disposition based on their needs. A streamlined process to identify patient needs related to the 4Ms and assessment of its impact needs evaluation.

In summary, our study identified what matters to older adults presenting to the ED and challenges or concerns related to medication, mobility, and mentation. Data show that using the 4Ms helps elucidate patient priorities and concerns, and incorporation of priorities and concerns into care has the potential to improve patient and care outcomes. Furthermore, by understanding patients more deeply, ED staff and administration can begin to respond appropriately in more systematic ways. For example, EDs can respond to concerns about memory loss by promoting brain health and early cognitive screening at discharge. The AFHS 4Ms framework can bring focus to areas where the ED can improve (e.g., medication education) and opportunities for health promotion (e.g., suggestions for screenings, advance directives, referrals, community resources, etc). The 4Ms framework has the potential to alter the care of older adults presenting to the ED to align with their values and improve outcomes while also guiding systematic improvements at the care provider and health system levels.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MS, MM, DL, and SL contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the, data, and drafting of the manuscript. MS and MM contributed to acquisition of the data. MS, MM, DL, AS, EKH, HB, HSR, and SL contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Abstract presented at American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Scientific Assembly, October, 1, 2022, San Francisco, California, USA.

Biographies

Melissa Sheber, MS, is a medical student at University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, IA.

Mackenzie McKnight, Resident physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine.

Daniel Liebzeit, Assistant professor, College of Nursing, University of Iowa.

Aaron Seaman, Assistant professor of internal medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver Collge of Medicine.

Erica K. Husser, Assistant research professor, Penn State University College of Nursing

Harleah Buck, Sally Mathis Hartwig Professor in Gerotological Nursing at the University of Iowa and Director of the Csomay Center.

Heather S. Reisinger, Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

Sangil Lee, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

Sheber M, McKnight M, Liebzeit D, et al. Older adults’ goals of care in the emergency department setting: A qualitative study guided by the 4Ms framework. JACEP Open. 2023;4:e13012. 10.1002/emp2.13012

Supervising Editor: Maura Kennedy, MD, MPH.

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bureau USC . Quick Facts. 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

- 2. Institute of Medicine Food F . The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Providing healthy and safe foods as we age: workshop summary. National Academies Press (US). Copyright © 2010. National Academy of Sciences; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dresden SM, Lo AX, Lindquist LA, et al. The impact of Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations (GEDI) on health services use, health related quality of life, and costs: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;97:106125. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haseler‐Ouart K, Arefian H, Hartmann M, Kwetkat A. Geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to the emergency department: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2021;144:111184. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gruneir A, Silver MJ, Rochon PA. Emergency department use by older adults: a literature review on trends, appropriateness, and consequences of unmet health care needs. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68(2):131‐155. doi: 10.1177/1077558710379422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD006211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pines JM, Mullins PM, Cooper JK, Feng LB, Roth KE. National trends in emergency department use, care patterns, and quality of care of older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):12‐17. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shadyab AH, Castillo EM, Chan TC, Tolia VM. Developing and implementing a geriatric emergency department (GED): overview and characteristics of GED visits. J Emerg Med. 2021;61(2):131‐139. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7‐8):469‐481. doi: 10.1177/0898264321991658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emery‐Tiburcio EE, Berg‐Weger M, Husser EK, et al. The geriatrics education and care revolution: diverse implementation of age‐friendly health systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):E31‐E33. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gettel CJ, Venkatesh AK, Dowd H, et al. A qualitative study of “What Matters” to older adults in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(4):579‐588. (In eng) doi: 10.5811/westjem.2022.4.56115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334‐340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid‐nur9>3.0.co;2‐g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia KKS, Abrahão AA. Research development using REDCap software. Healthc Inform Res. 2021;27(4):341‐349. doi: 10.4258/hir.2021.27.4.341. In eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245‐1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1986;8(3):27‐37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaldjian LC, Curtis AE, Shinkunas LA, Cannon KT. Goals of care toward the end of life: a structured literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(6):501‐511. doi: 10.1177/1049909108328256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ouchi K, George N, Schuur JD, et al. Goals‐of‐care conversations for older adults with serious illness in the emergency department: challenges and opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(2):276‐284. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, Lind JN, Pollock DA. US emergency department visits attributed to medication harms, 2017–2019. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1299‐1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Briggs S, Pearce R, Dilworth S, Higgins I, Hullick C, Attia J. Clinical pharmacist review: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27(5):419‐426. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi YJ, Kim H. Effect of pharmacy‐led medication reconciliation in emergency departments: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(6):932‐945. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hastings SN, Barrett A, Weinberger M, et al. Older patients' understanding of emergency department discharge information and its relationship with adverse outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2011;7(1):19‐25. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31820c7678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shimada H, Park H, Makizako H, Doi T, Lee S, Suzuki T. Depressive symptoms and cognitive performance in older adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;57:149‐156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saiz‐Vazquez O, Gracia‐Garcia P, Ubillos‐Landa S, et al. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review of longitudinal meta‐analyses. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9). doi: 10.3390/jcm10091809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW. Does functional decline prompt emergency department visits and admission in older patients? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(6):680‐682. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.01.006. In eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information