Abstract

The highly enantioselective and complete hydrogenation of protected indoles and benzofurans has been developed, affording facile access to a range of chiral three-dimensional octahydroindoles and octahydrobenzofurans, which are prevalent in many bioactive molecules and organocatalysts. Remarkably, we are in control of the nature of the ruthenium N-heterocyclic carbene complex and employed the complex as both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, providing new avenues for its potential applications in the asymmetric hydrogenation of more challenging aromatic compounds.

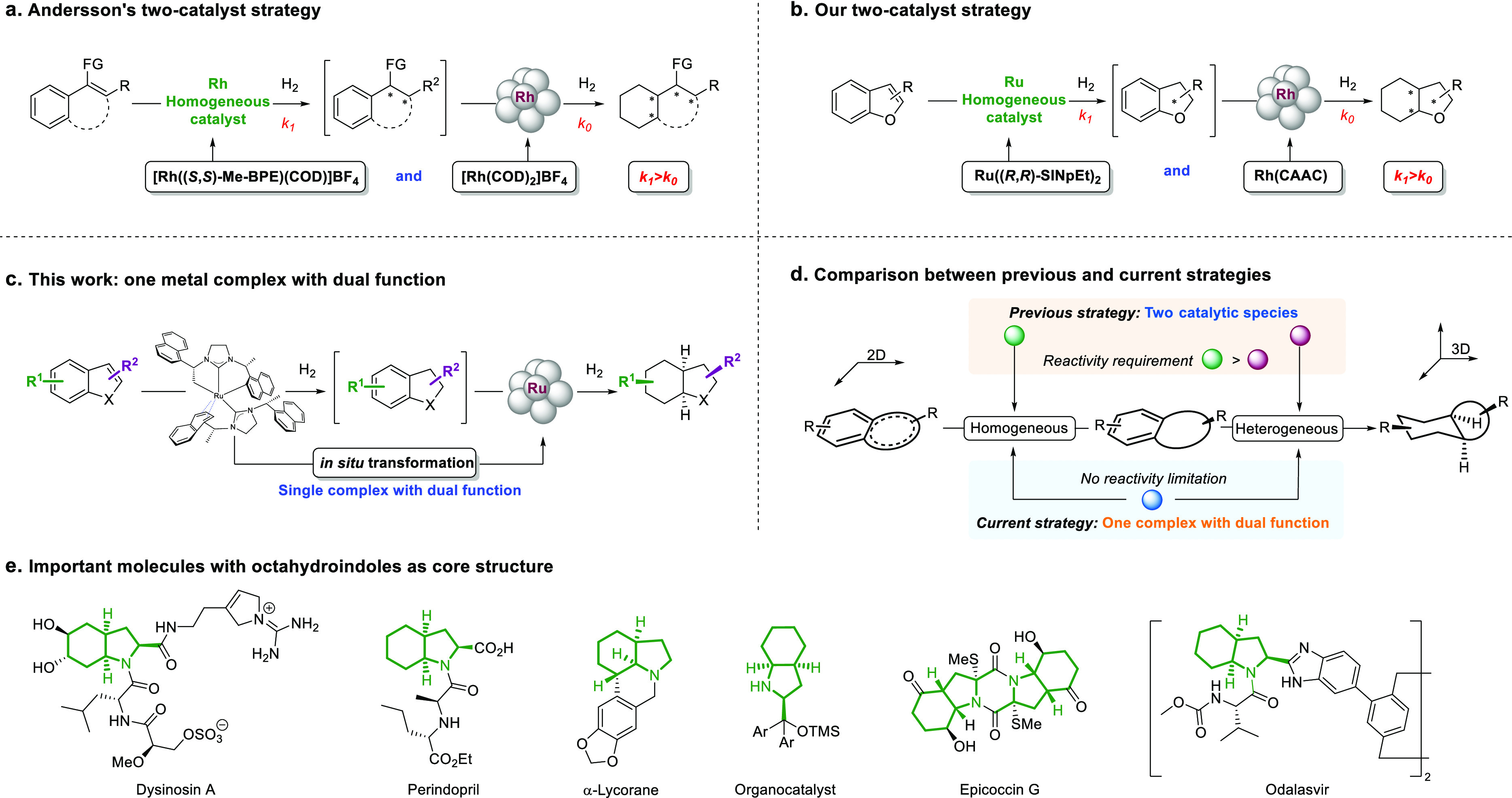

The transformation and utilization of inexpensive and readily available arenes have become a principal area of research.1−4 The complete hydrogenation of arenes5−10 is one of the most effective methods for converting planar molecules into saturated three-dimensional structures, which are critical building blocks in many aspects of life.4,11−22 However, asymmetric hydrogenation of arenes has historically been a major challenge due to the lack of enantioselective catalysts, and the successful cases have largely been confined to the rings with weak aromaticity, such as heteroaromatic rings5,23−30 and fused arenes.31−35 The combination of heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis has proven to be a promising method for hydrogenation of aromatic compounds.36−39 Recently, Andersson’s group utilized an excessive amount of ligands compared to the Rh precursor to generate both homo- and heterogeneous catalysts in the reaction. Subsequently, they took advantage of the high reaction rate of homogeneous hydrogenation and the induction period of heterogeneous hydrogenation to achieve an asymmetric and complete reduction of arenes (Figure 1a).38 Additionally, we realized an unprecedented protocol for asymmetric and complete reduction of the benzofuran through partial hydrogenation of the benzofuran ring using a homogeneous Ru catalyst, followed by the hydrogenation of the benzene ring catalyzed by an in situ generated Rh heterogeneous catalyst (Figure 1b).39

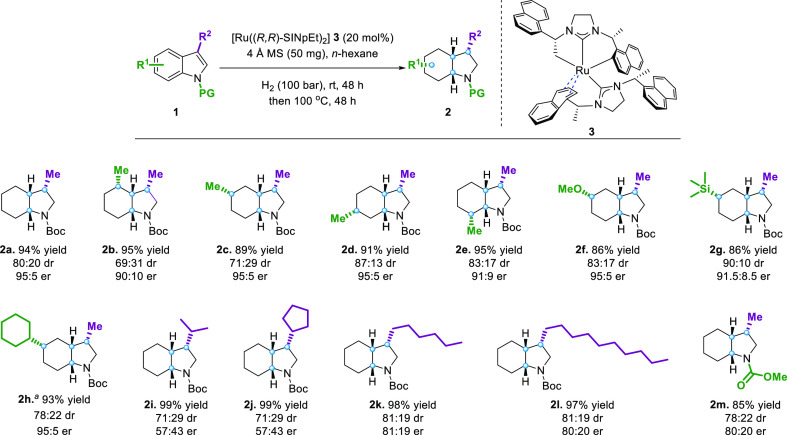

Figure 1.

(a–d) Development of a new synergistic catalytic system using one single molecular complex to access saturated octahydroindoles and octahydrobenzofurans. (e) Representative marketed pharmaceuticals, natural products, and catalysts containing octahydroindole moieties.

Due to the presence of two catalysts, the success of the aforementioned two examples (Figure 1a, 1b) is primarily attributed to the compatibility of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts. For instance, the reactivity of the homogeneous catalyst to the substrate has to be higher than that of the heterogeneous catalyst to avoid the racemic background reaction and achieve high enantioselectivity. Therefore, we propose a new approach that utilizes both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts in succession in one pot with only one species of catalyst in each stage. This would allow us to completely avoid the racemic background reduction independent of the reactivity of the substrate, thus expanding the potential substrate scope. To achieve this, the catalyst must be able to play different roles in different hydrogenation steps. For instance, in the first step, the catalyst should perform as an active homogeneous catalyst, catalyzing the partially enantioselective reduction and then transforming into a heterogeneous catalyst to hydrogenate the more challenging aromatic rings (Figure 1d).

Octahydroindoles are important structural motifs, prevalent in many marketed drugs,40,41 natural products,42,43 bioactive molecules,44 and organocatalysts (Figure 1e).45,46 Therefore the development of synthetic methods for chiral octahydroindoles is of high importance.47−55 Although there are some reports on the asymmetric partial hydrogenation of indoles,56−70 however, to the best of our knowledge, chiral octahydroindoles have not been accessed via complete, enantioselective hydrogenation of indoles despite the straightforwardness of the transformation.71−77 Therefore, we proposed a novel enantioselective hydrogenation utilizing dual catalysis driven by a single metal complex to access chiral octahydroindoles. Our group previously developed a Ru-chiral carbene catalyst (Ru((R,R)-SINpEt)2) with excellent reactivity and enantioselectivity in the hydrogenation of heterocyclic aromatic compounds.31,78−82 Drawing on the reported literature and our research on carbene chemistry, we envisioned that metal–carbene complexes could be promising to fulfill the requirements for an in situ transformable catalyst since these complexes can be converted into nanosized heterogeneous particles.7,83−86 We herein report highly enantioselective and diastereoselective complete hydrogenation of indoles, using Ru((R,R)-SINpEt)2 as a dual functional catalyst, to synthesize a wide range of chiral octahydroindoles (Figure 1c). In addition, this strategy was found to be generalized for the complete hydrogenation of benzofurans. The architecturally complex octahydrobenzofurans were thus obtained readily as well.

To help probe the one-pot dual-catalysis strategy using the Ru-NHC catalyst, we opted for N-Boc-protected 3-methyl-indole 1a as our model substrate. We initially conducted the experiment under 100 bar of H2 in n-hexane at room temperature (Table 1). After 48 h, the reaction temperature was increased to 100 °C to promote the aggregation of the Ru-NHC complex into Ru nanoparticles (Figure S1, SI). After 48 h, the desired octahydroindole 2a was obtained with 10% yield, 87:13 dr, and 95:5 er (entry 1). It was noted that some partially reduced intermediate generated from the first step had not been completely consumed, indicating that the in situ generated heterogeneous catalyst was not active enough. Previous reports have shown that metal nanoparticles are more likely to form and are more active when a porous solid support is present in the reaction system.87−90 This is because the porous solid acts as a heterogeneous support for the nucleation of the metal nanoparticles and restricts them from their subsequent agglomeration. In addition, the porous support also helps to facilitate the growth of the metal nanoparticles by acting as a carrier and enhancing the efficient substrate-active site interaction at the solid–liquid interfaces.90 Therefore, we tested some solid additives as heterogeneous support (entries 2–5) and found that 4 Å MS resulted in the best outcome, leading to 94% isolated yield, 80:20 dr, and 95:5 er (entry 2). Upon further evaluation of the solvents (entries 6–8), we determined hexane to be the optimal choice.

Table 1. Investigations on Solvents and Additives of Ru-NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric, Complete Hydrogenation of 1aa.

| entry | solvent | additive | yield (%)b | drb | erc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n-hexane | no | 10 | 87:13 | 95:5 |

| 2 | n-hexane | 4 Å MS | 99 [94]d | 80:20 | 95:5 |

| 3 | n-hexane | NaCl | 46 | 87:13 | 94:6 |

| 4 | n-hexane | Celite | 15 | 87:13 | 94:6 |

| 5 | n-hexane | silica gel | 86 | 78:22 | 95:5 |

| 6 | Et2O | 4 Å MS | 98 | 78:22 | 82:18 |

| 7 | THF | 4 Å MS | 99 | 80:20 | 65:35 |

| 8 | DME | 4 Å MS | 99 | 80:20 | 61:39 |

General conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), additive (50 mg), and 3 (0.8 mL, 0.025 mmol/mL) in solvent (0.2 mL), and the hydrogenation was performed at 25 °C under 100 bar of H2 for 48 h, then at 100 °C under 100 bar of H2 for 48 h.

Determined by GC-FID.

Determined by HPLC on a chiral stationary phase.

Isolated yield including all diastereomers.

With the optimized condition established, we investigated the effect of the substituents’ position in the benzene ring (Figure 2). To our delight, substitution across different positions in the benzene ring was efficiently hydrogenated with high yields (2b–2e). Additionally, the enantioselectivity was preserved when the substituent was remotely situated from the heterocyclic ring in indole (6- or 7-substituted indole, 2c, 2d). Nevertheless, in the case of proximal substituents to the heterocyclic ring in indole (5- or 8-position, 2b, 2e), the er decreased slightly. Furthermore, when the substituents were at the 5- or 6-position (2b, 2c), diastereoselectivity was adversely affected. Subsequently, we investigated the effects of different substituents at the 6-position on the reaction output. To our delight, the functional group variation of the substituents at the 6-position did not have a noticeable impact on the reactions and resulted in complete hydrogenated products with similar yield, er, and dr. Remarkably, the reaction tolerated both the carbon–oxygen (2f) and carbon–silicon (2g) bonds. This provides a significant impact in synthetic chemistry, as silyl groups are widely used as synthetic handles for further downstream modifications91−96 Furthermore, a phenyl group as a substituent of arene was also reduced under the reaction conditions, giving the fully saturated product (2h). Next, we attempted to vary the substituent at position 3 of indoles. We observed that different groups had a slight effect on the yield and diastereoselectivity (2i–2l). However, a remarkable decline in enantioselectivity was observed in the case of bulky substituents (2i, 2j). Finally, the protecting group of indoles also influenced the reaction, since the er decreased when the Boc protecting group was replaced by the methyl ester (2m).

Figure 2.

Substrate scope of 3-alkyl-protected indoles. General conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 4 Å MS (50 mg), and 3 (0.8 mL, 0.025 mmol/mL) in n-hexane (0.2 mL), and the hydrogenation was performed at 25 °C under 100 bar of H2 for 48 h and then at 100 °C under 100 bar of H2 for 48 h. Yields of isolated products including all diastereomers are given. The major diastereomer is separable. er was determined by chiral HPLC or chiral GC-FID. dr was determined by GC-FID of the crude product mixture. aPhenyl-substituent-containing substrate was used.

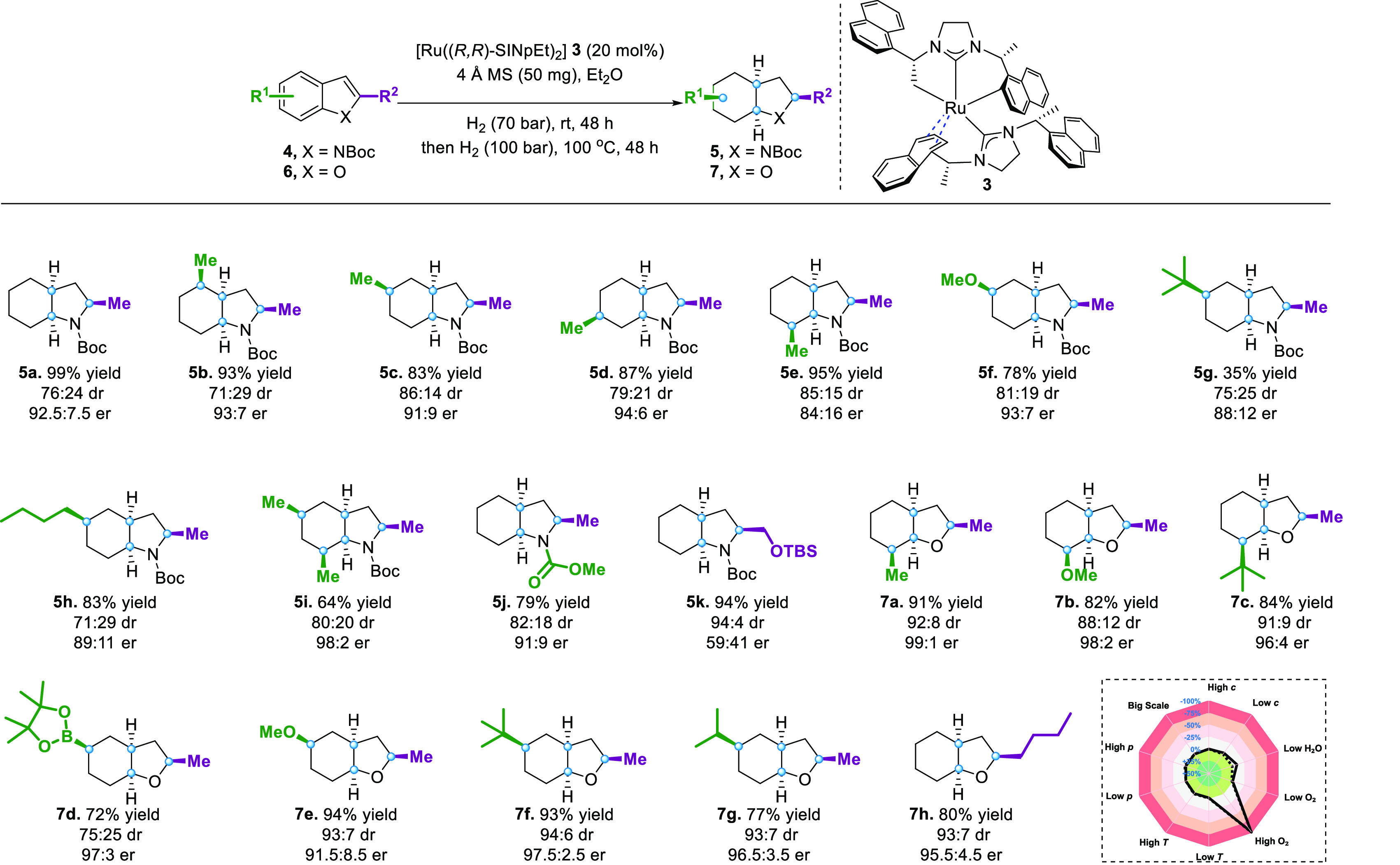

Subsequently, we examined 2-substituted protected indoles. However, we found the er of the desired product unsatisfactory under the already optimized conditions. Herein, we reoptimized the conditions and found that Et2O was the best solvent (Table S2, SI). First of all, we altered the position of the methyl group in the benzene ring (Figure 3, 5b–5e) and found that, except for the 8-substituted indole, which provided a relatively low er (5e), the substituents at other positions had a minimal effect on the results of the reaction’s yield and selectivity. Next, we conducted our hydrogenation with different substrates by varying substituents at the 6-position. We observed that the less bulky methoxyl group does not affect the reaction (5f). However, when tert-butyl (5g) and n-butyl (5h) were present at the 6-position, the enantiomeric ratios of the corresponding products decreased slightly. The bulky tert-butyl group also reduced the yield as some of the partially hydrogenated product was not completely consumed. To our delight, the 6,8-disubstituted indole was also suitable for our reaction (5i) and yielded the corresponding product with high enantioselectivity and yield. In contrast to 3-substituted indole (2m), altering the protecting group had no significant effect on the reaction (5j). Finally, the dr improved significantly with increasing bulk at the 2-position; however, the corresponding er dropped dramatically (5k).

Figure 3.

Substrate scope of 2-methyl-protected indoles and 2-alkyl-benzofurans. General conditions: 4 (0.1 mmol), 4 Å MS (50 mg), and 3 (0.8 mL, 0.025 mmol/mL) in Et2O (2.0 mL), and the hydrogenation was performed at 25 °C under 70 bar of H2 for 48 h and then at 100 °C under 100 bar of H2 for 48 h. Yields of isolated products including all diastereomers are given. The major diastereomer is inseparable. er was determined by chiral HPLC or chiral GC-FID. dr was determined by GC-FID of the crude product mixture. Reaction condition-based sensitivity assessment (within box).

We then applied our protocol to the complete hydrogenation of benzofuran to investigate the generality of the proposed dual-catalytic strategy with the successive combination of homo- and heterogeneous reaction conditions. We found that all substrates gave excellent results comparable to our previous report, which used two different catalysts (Figure 3, 7a–7h).39 Additionally, the current method also tolerates the carbon–boron bond well (7d), thus expanding its application in organic synthesis. To our surprise, the substituents with large steric hindrances, such as tert-butyl and isopropyl groups, did not affect the reaction, providing complete conversion of substrates with high yields and excellent dr and er (7c, 7f, 7g). Variation of the 2-substituent on the furan ring was well tolerated (7h). A further comparison between the current protocol with our previous method can be seen in the Supporting Information (Scheme S4, SI). The evaluation of the reaction-condition-based sensitivity screen of the developed protocol revealed a robust reaction (Figure S4, SI).97

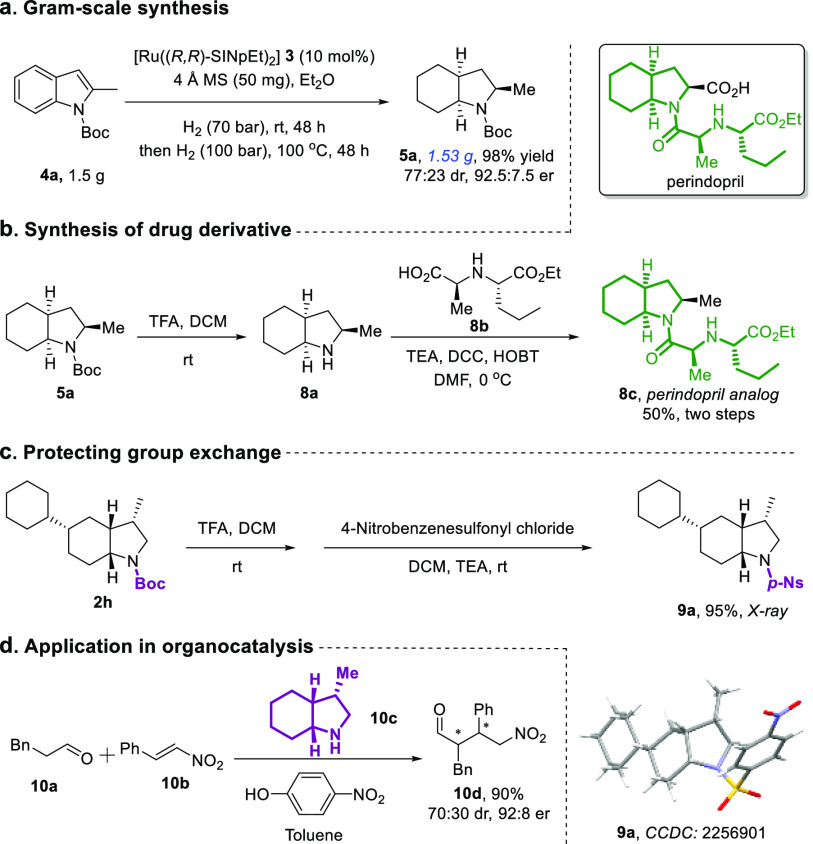

To demonstrate the utility of our protocol in organic synthesis, we successfully scaled up the reaction to the gram scale and obtained excellent results (Figure 4a). Next, we removed the protecting group of 5a, performed a coupling reaction with compound 8b, and successfully obtained the marketed drug perindopril analogue with 50% yield. In addition, compound 2h could undergo a one-pot reaction that facilitates the switching of protecting groups, leading to 9a. The single crystal of 9a (CCDC: 2256901) was also used to determine the absolute conformation of the products. It is well known that secondary amines are excellent organocatalysts. Hence, we applied compound 10c, obtained from the deprotection of compound 2a, to catalyze the intermolecular asymmetric 1,4-addition. We found that the secondary amine (10c) exhibited good catalytic activity, completing the reaction in only 30 min, with a high yield and enantioselectivity, as well as moderate diastereoselectivity.

Figure 4.

(a) Gram-scale synthesis of 5a. (b) Diversification of product 5a, synthesizing drug derivative 8c. (c) Protecting group exchange. (d) Organocatalytic application.

In conclusion, we have developed a ruthenium-NHC-catalyzed asymmetric, complete hydrogenation of protected indoles and benzofurans, which enabled the installation of up to five newly defined stereocenters. This protocol yielded a broad range of highly valuable octahydroindoles and octahydrobenzofurans in high yields and with good enantioselectivities and diastereoselectivities. Additionally, we rationally designed and implemented a new strategy that one metal complex can play two functions in succession by an in situ transformation. Our findings suggest the great potential of the new strategy to be expanded to further substrate classes. We are currently exploring this exciting direction and will disclose our discoveries in due course.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant Agreement No. 788558) for its generous financial support. We also thank Dr. Fupeng Wu, Dr. Tianjiao Hu, Dr. Akash Kaithal, Arne Heusler, Lukas Lückermeier, Marco Pierau, Steffen Heuvel, and Debanjan Rana for insightful discussions (all WWU).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c04983.

Experimental details including the synthetic procedures and analytical data for all new compounds, optimization data, gram-scale synthesis, sensitivity screen, mechanistic analysis data including the investigation of the heterogeneous catalyst, and copies of NMR spectra of the compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mortier J., Arene Chemistry: Reaction Mechanisms and Methods for Aromatic Compounds; John Wiley & Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huck C. J.; Sarlah D. Shaping Molecular Landscapes: Recent Advances, Opportunities, and Challenges in Dearomatization. Chem 2020, 6, 1589–1603. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C.; You S. L. Advances in Catalytic Asymmetric Dearomatization. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 432–444. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeldt M. P.; Nairoukh Z.; Dalton T.; Glorius F. Selective Arene Hydrogenation for Direct Access to Saturated Carbo- and Heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10460–10476. 10.1002/anie.201814471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gual A.; Godard C.; Castillón S.; Claver C. Soluble transition-metal nanoparticles-catalysed hydrogenation of arenes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 11499–11512. 10.1039/c0dt00584c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y.; Rao B.; Cong X.; Zeng X. Highly Selective Hydrogenation of Aromatic Ketones and Phenols Enabled by Cyclic (Amino)(alkyl)carbene Rhodium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9250–9253. 10.1021/jacs.5b05868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X.; Surkus A.-E.; Junge K.; Topf C.; Radnik J.; Kreyenschulte C.; Beller M. Highly selective hydrogenation of arenes using nanostructured ruthenium catalysts modified with a carbon–nitrogen matrix. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11326. 10.1038/ncomms11326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustra Z. X.; Ishibashi J. S. A.; Liu S.-Y. Homogeneous metal catalysis for conversion between aromatic and saturated compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 314, 134–181. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papa V.; Cao Y.; Spannenberg A.; Junge K.; Beller M. Development of a practical non-noble metal catalyst for hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 135–142. 10.1038/s41929-019-0404-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer W. H. B.; Schwarz M. K. Molecular Shape Diversity of Combinatorial Libraries: A Prerequisite for Broad Bioactivity. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 987–1003. 10.1021/ci025599w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters W. P.; Green J.; Weiss J. R.; Murcko M. A. What Do Medicinal Chemists Actually Make? A 50-Year Retrospective. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6405–6416. 10.1021/jm200504p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C. Heterocyclic chemistry in crop protection. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 1106–1114. 10.1002/ps.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldeghi M.; Malhotra S.; Selwood D. L.; Chan A. W. E. Two- and Three-dimensional Rings in Drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des 2014, 83, 450–461. 10.1111/cbdd.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafusa M.; Tsuchida Y.; Matsumoto K.; Kondo K.; Yoshizawa M. Three host peculiarities of a cycloalkane-based micelle toward large metal-complex guests. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6061. 10.1038/s41467-020-19886-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapf M.; Seichter W.; Mazik M. Cycloalkyl Groups as Subunits of Artificial Carbohydrate Receptors: Effect of Ring Size of the Cycloalkyl Unit on the Receptor Efficiency. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 4900–4915. 10.1002/ejoc.202000803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke P. Manufacturing Approaches of New Halogenated Agrochemicals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101513 10.1002/ejoc.202101513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaithal A.; Wagener T.; Bellotti P.; Daniliuc C. G.; Schlichter L.; Glorius F. Access to Unexplored 3D Chemical Space: cis-Selective Arene Hydrogenation for the Synthesis of Saturated Cyclic Boronic Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202206687 10.1002/anie.202206687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. D.; MacCoss M.; Lawson A. D. G. Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859. 10.1021/jm4017625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaku E.; Smith D. T.; Njardarson J. T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G.; Boström J. Analysis of Past and Present Synthetic Methodologies on Medicinal Chemistry: Where Have All the New Reactions Gone?. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann M. M.; Leach A. R.; Harper G. Molecular Complexity and Its Impact on the Probability of Finding Leads for Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2001, 41, 856–864. 10.1021/ci000403i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroaromatic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1357–1366. 10.1021/ar700094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.-S.; Chen Q.-A.; Lu S.-M.; Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroarenes and Arenes. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2557–2590. 10.1021/cr200328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Jin W.; Jiang Q. Bro̷nsted Acid Activation Strategy in Transition-Metal Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of N-Unprotected Imines, Enamines, and N-Heteroaromatic Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6060–6072. 10.1002/anie.201200963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.-A.; Ye Z.-S.; Duan Y.; Zhou Y.-G. Homogeneous palladium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 497–511. 10.1039/C2CS35333D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D.; Glorius F. Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Isoquinolines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9616–9618. 10.1002/anie.201304756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.-M.; Song F.-T.; Fan Q.-H. Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroaromatic Compounds. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 343, 145–190. 10.1007/128_2013_480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A. N.; Stoltz B. M. Recent Advances in Homogeneous Catalysts for the Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroarenes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 13834–13851. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano R. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 5-Membered Heteroaromatics. Heterocycles 2008, 76, 909–922. 10.3987/REV-08-SR(N)5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S.; Ortega N.; Glorius F. Ligand-Controlled Highly Regioselective and Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Quinoxalines Catalyzed by Ruthenium N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3803–3806. 10.1002/anie.201100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z.; Xie H.-P.; Shen H.-Q.; Zhou Y.-G. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of Carbocyclic Aromatic Amines: Access to Chiral Exocyclic Amines. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1094–1097. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b04060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.-X.; Zhu Z.-H.; Chen M.-W.; Yu C.-B.; Zhou Y.-G. Rhodium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of All-Carbon Aromatic Rings. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205623 10.1002/anie.202205623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viereck P.; Hierlmeier G.; Tosatti P.; Pabst T. P.; Puentener K.; Chirik P. J. Molybdenum-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Fused Arenes and Heteroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11203–11214. 10.1021/jacs.2c02007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.-X.; Xu C.; Yi N.; Li S.; He Y.-M.; Feng Y.; Fan Q.-H. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Hydrogenation of 9-Phenanthrols. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205739 10.1002/anie.202205739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee B.; Kalsi D.; Kaithal A.; Bordet A.; Leitner W.; Gunanathan C. One-pot dual catalysis for the hydrogenation of heteroarenes and arenes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 5163–5170. 10.1039/D0CY00928H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Hao W.; Yi N.; He Y.-M.; Fan Q.-H. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Naphthol and Phenol Derivatives with Cooperative Heterogeneous and Homogeneous Catalysis. CCS Chemistry 2023, 0, 1–31. 10.31635/ccschem.023.202303007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Yang J.; Peters B. B. C.; Massaro L.; Zheng J.; Andersson P. G. Asymmetric Full Saturation of Vinylarenes with Cooperative Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Rhodium Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20377–20383. 10.1021/jacs.1c09975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moock D.; Wagener T.; Hu T.; Gallagher T.; Glorius F. Enantio- and Diastereoselective, Complete Hydrogenation of Benzofurans by Cascade Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13677–13681. 10.1002/anie.202103910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst M.; Jarvis B. Perindopril: an updated review of its use in hypertension. Drugs 2001, 61, 867–96. 10.2165/00003495-200161060-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran D. N.; Zhdanko A.; Barroso S.; Nieste P.; Rahmani R.; Holan J.; Hoefnagels R.; Reniers P.; Vermoortele F.; Duguid S.; Cazanave L.; Figlus M.; Muir C.; Elliott A.; Zhao P.; Paden W.; Diaz C. H.; Bell S. J.; Hashimoto A.; Phadke A.; Wiles J. A.; Vogels I.; Farina V. Development of a Commercial Process for Odalasvir. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 832–848. 10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavre M.; Froese J.; Pour M.; Hudlicky T. Synthesis of Amaryllidaceae Constituents and Unnatural Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5642–5691. 10.1002/anie.201508227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Totokotsopoulos S.; Giguère D.; Sun Y.-P.; Sarlah D. Total Synthesis of Epicoccin G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8150–8153. 10.1021/ja2032635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. R.; Pierens G. K.; Fechner G.; De Almeida Leone P.; Ngo A.; Simpson M.; Hyde E.; Hooper J. N.; Bostrom S. L.; Musil D.; Quinn R. J. Dysinosin A: a novel inhibitor of Factor VIIa and thrombin from a new genus and species of Australian sponge of the family Dysideidae. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13340–1. 10.1021/ja020814a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arceo E.; Jurberg I. D.; Álvarez-Fernández A.; Melchiorre P. Photochemical activity of a key donor–acceptor complex can drive stereoselective catalytic α-alkylation of aldehydes. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 750–756. 10.1038/nchem.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayago F. J.; Laborda P.; Calaza M. I.; Jiménez A. I.; Cativiela C. Access to the cis-Fused Stereoisomers of Proline Analogues Containing an Octahydroindole Core. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 2011–2028. 10.1002/ejoc.201001710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brion F.; Marie C.; Mackiewicz P.; Roul J. M.; Buendia J. Stereoselective synthesis of a trans-octahydroindole derivative, precursor of trandolapril (RU 44 570), an inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 4889–4892. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)61225-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. G.; Kasi D.; Fushimi M.; Cuzzupe A.; Wipf P. Synthesis of Hydroxylated Bicyclic Amino Acids from l-Tyrosine: Octahydro-1H-indole Carboxylates. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7807–7810. 10.1021/jo801552j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansare S. V.; Lingampally R.; Kirby R. L. Stereoselective Synthesis of 3-Aryloctahydroindoles and Application in a Formal Synthesis of (−)-Pancracine. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 556–559. 10.1021/ol902761a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayago F. J.; Pueyo M. J.; Calaza M. I.; Jiménez A. I.; Cativiela C. Practical access to the proline analogs (S,S,S)- and (R,R,R)-2-methyloctahydroindole-2-carboxylic acids by HPLC enantioseparation. Chirality 2011, 23, 507–513. 10.1002/chir.20952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch C. H.; Brinck J. A.; Ramos J. E.; Habay S. A.; Yap G. P. A. Synthesis of cis-Octahydroindoles via Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of 2-Acyl-5-aminooxazolium Salts. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10416–10421. 10.1021/jo301600p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzakis D.; Triantafyllakis M.; Ioannou G. I.; Vassilikogiannakis G. One-Pot Transformation of Simple Furans into Octahydroindole Scaffolds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4020–4023. 10.1002/anie.201700620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros-Ceballos J. L.; Martínez-Toto E. I.; Eustaquio-Armenta C.; Cativiela C.; Ordóñez M. First and Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of Both Enantiomers of Octahydroindole-2-phosphonic Acid (OicP). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 6781–6787. 10.1002/ejoc.201701330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda J.; Široký M.; Martinková M.; Homolya S.; Vilková M.; Pilátová M. B.; Šesták S. Synthesis and biological activity of diastereoisomeric octahydro-1H-indole-5,6,7-triols, analogues of castanospermine. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 398–408. 10.1016/j.tet.2018.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marbán-González A.; Maravilla-Moreno G.; Vazquez-Chavez J.; Hernández-Rodríguez M.; Razo-Hernández R. S.; Ordóñez M.; Viveros-Ceballos J. L. Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Enantiopure cis-Fused Octahydroisoindolones via Chiral Oxazoloisoindolone Lactams. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 16361–16368. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano R.; Sato K.; Kurokawa T.; Karube D.; Ito Y. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroaromatic Compounds. Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7614–7615. 10.1021/ja001271c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano R.; Kashiwabara M. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of N-Boc-Indoles. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2653–2655. 10.1021/ol061039x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano R.; Kashiwabara M.; Sato K.; Ito T.; Kaneda K.; Ito Y. Catalytic asymmetric hydrogenation of indoles using a rhodium complex with a chiral bisphosphine ligand PhTRAP. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 521–535. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baeza A.; Pfaltz A. Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of N-Protected Indoles. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 2036–2039. 10.1002/chem.200903105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.-S.; Chen Q.-A.; Li W.; Yu C.-B.; Zhou Y.-G.; Zhang X. Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected Indoles Activated by Bro̷nsted Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8909–8911. 10.1021/ja103668q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.-S.; Tang J.; Zhou Y.-G.; Chen M.-W.; Yu C.-B.; Duan Y.; Jiang G.-F. Dehydration triggered asymmetric hydrogenation of 3-(α-hydroxyalkyl)indoles. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 803–806. 10.1039/c0sc00614a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y.; Li L.; Chen M.-W.; Yu C.-B.; Fan H.-J.; Zhou Y.-G. Homogenous Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected Indoles: Scope and Mechanistic Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7688–7700. 10.1021/ja502020b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Rico J. L.; Fernández-Pérez H.; Vidal-Ferran A. Asymmetric hydrogenation of unprotected indoles using iridium complexes derived from P–OP ligands and (reusable) Bro̷nsted acids. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1153–1157. 10.1039/c3gc42132e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touge T.; Arai T. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected Indoles Catalyzed by η6-Arene/N-Me-sulfonyldiamine–Ru(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11299–11305. 10.1021/jacs.6b06295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J.; Fan X.; Tan R.; Chien H.-C.; Zhou Q.; Chung L. W.; Zhang X. Bro̷nsted-Acid-Promoted Rh-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of N-Unprotected Indoles: A Cocatalysis of Transition Metal and Anion Binding. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2143–2147. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y.; Wang Z.; Han Z.; Ding K. Iridium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Indole and Benzofuran Derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15482–15486. 10.1002/chem.202002532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Zhang Z.; Feng X.; Yang J.; Du H. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Unprotected Indoles with Ammonia Borane. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5850–5854. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Yu Y.-J.; Wang X.-Q.; Bai Y.-Q.; Chen M.-W.; Zhou Y.-G. Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected 3-Substituted Indoles. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 10398–10407. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Zheng L.; Tian K.; Wang H.; Wa Chung L.; Zhang X.; Dong X.-Q. Ir-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unprotected Indoles: Scope Investigations and Mechanistic Studies. CCS Chemistry 2023, 0, 1–13. 10.31635/ccschem.022.202101643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. S.; Chen F.; He Y. M.; Yang N. F.; Fan Q. H. Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of Indolines: Asymmetric Hydrogenation at Ambient Temperature and Pressure with Cationic Ruthenium Diamine Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13863–13866. 10.1002/anie.201607890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent M.; Rémond G.; Portevin B.; Serkiz B.; Laubie M. Stereoselective synthesis of a new perhydroindole derivative of chiral iminodiacid, a potent inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 1677–1680. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)87188-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarisse D.; Fenet B.; Fache F. Hexafluoroisopropanol: a powerful solvent for the hydrogenation of indole derivatives. Selective access to tetrahydroindoles or cis-fused octahydroindoles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 6587–6594. 10.1039/c2ob25980j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. S. Facile syntheses of isotope-labeled chiral octahydroindole-2-carboxylic acid and its N-methyl analog. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2012, 292, 1371–1376. 10.1007/s10967-012-1619-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B.; Süss-Fink G. Ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogenation of aromatic amino acids in aqueous solution. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 812, 81–86. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2015.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenburg M.; Moock D.; Glorius F. Hydrogenation of Borylated Arenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6549–6553. 10.1002/anie.201810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer J.; Bachmann P.; Freiberger E. M.; Bauer U.; Steinrück H. P.; Papp C. Model Catalytic Studies of Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers: Indole/Indoline/Octahydroindole on Ni(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 22559–22567. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c06988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener T.; Pierau M.; Heusler A.; Glorius F. Synthesis of Saturated N-Heterocycles via a Catalytic Hydrogenation Cascade. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 3366–3371. 10.1002/adsc.202200601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröge T.; Glorius F. The Measure of All Rings—N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6940–6952. 10.1002/anie.201001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D.; Beiring B.; Glorius F. Ruthenium–NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Flavones and Chromones: General Access to Enantiomerically Enriched Flavanones, Flavanols, Chromanones, and Chromanols. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8454–8458. 10.1002/anie.201302573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki J.; Ortega N.; Glorius F. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Disubstituted Furans. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8751–8755. 10.1002/anie.201310985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D.; Beiring B.; Plois M.; Ortega N.; Kock S.; Schlüns D.; Neugebauer J.; Wolf R.; Glorius F. A Cyclometalated Ruthenium-NHC Precatalyst for the Asymmetric Hydrogenation of (Hetero)arenes and Its Activation Pathway. Organomet. 2016, 35, 3641–3646. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlepphorst C.; Wiesenfeldt M. P.; Glorius F. Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 356–359. 10.1002/chem.201705370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath K. V. S.; Kloesges J.; Schäfer A. H.; Glorius F. Asymmetric Nanocatalysis: N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Chiral Modifiers of Fe3O4/Pd nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7786–7789. 10.1002/anie.201002782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukhovitskiy A. V.; MacLeod M. J.; Johnson J. A. Carbene Ligands in Surface Chemistry: From Stabilization of Discrete Elemental Allotropes to Modification of Nanoscale and Bulk Substrates. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11503–11532. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. B.; Muratsugu S.; Wang F.; Tada M.; Glorius F. Tunable Heterogeneous Catalysis: N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Ligands for Supported Heterogeneous Ru/K-Al2O3 Catalysts To Tune Reactivity and Selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10718–10721. 10.1021/jacs.6b03821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moock D.; Wiesenfeldt M. P.; Freitag M.; Muratsugu S.; Ikemoto S.; Knitsch R.; Schneidewind J.; Baumann W.; Schafer A. H.; Timmer A.; Tada M.; Hansen M. R.; Glorius F. Mechanistic Understanding of the Heterogeneous, Rhodium-Cyclic (Alkyl)(Amino)Carbene-Catalyzed (Fluoro-)Arene Hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 6309–6317. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Xu X.; Tian Z.; Zong Y.; Cheng H.; Lin C. Selective heterogeneous nucleation and growth of size-controlled metal nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes in solution. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 2542–9. 10.1002/chem.200501010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree R. H. Resolving heterogeneity problems and impurity artifacts in operationally homogeneous transition metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1536–54. 10.1021/cr2002905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Yuan K.; Stack A. G.; Starchenko V. Numerical Study of Mineral Nucleation and Growth on a Substrate. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2022, 6, 1655–1665. 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W.; Hood Z. D.; Chi M. Interfaces in Heterogeneous Catalysts: Advancing Mechanistic Understanding through Atomic-Scale Measurements. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 787–795. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langkopf E.; Schinzer D. Uses of Silicon-Containing Compounds in the Synthesis of Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 1375–1408. 10.1021/cr00037a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I.; Barbero A.; Walter D. Stereochemical Control in Organic Synthesis Using Silicon-Containing Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2063–2192. 10.1021/cr941074u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash G. K. S.; Yudin A. K. Perfluoroalkylation with Organosilicon Reagents. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 757–786. 10.1021/cr9408991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook A. G. Molecular rearrangements of organosilicon compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1974, 7, 77–84. 10.1021/ar50075a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. R.; Landais Y. The oxidation of the carbon-silicon bond. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 7599–7662. 10.1016/S0040-4020(96)00038-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sore H. F.; Galloway W. R. J. D.; Spring D. R. Palladium-catalysed cross-coupling of organosilicon reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1845–1866. 10.1039/C1CS15181A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzer L.; Schäfers F.; Glorius F. Rapid Assessment of the Reaction-Condition-Based Sensitivity of Chemical Transformations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8572–8576. 10.1002/anie.201901935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.