Abstract

Background

community-based complex interventions for older adults have a variety of names, including Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, but often share core components such as holistic needs assessment and care planning.

Objective

to summarise evidence for the components and effectiveness of community-based complex interventions for improving older adults’ independent living and quality of life (QoL).

Methods

we searched nine databases and trial registries to February 2022 for randomised controlled trials comparing complex interventions to usual care. Primary outcomes included living at home and QoL. Secondary outcomes included mortality, hospitalisation, institutionalisation, cognitive function and functional status. We pooled data using risk ratios (RRs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

we included 50 trials of mostly moderate quality. Most reported using holistic assessment (94%) and care planning (90%). Twenty-seven (54%) involved multidisciplinary care, with 29.6% delivered mainly by primary care teams without geriatricians. Nurses were the most frequent care coordinators. Complex interventions increased the likelihood of living at home (RR 1.05; 95% CI 1.00–1.10; moderate-quality evidence) but did not affect QoL. Supported by high-quality evidence, they reduced mortality (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.77–0.96), enhanced cognitive function (SMD 0.12; 95% CI 0.02–0.22) and improved instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs) (SMD 0.11; 95% CI 0.01–0.21) and combined basic/instrumental ADLs (SMD 0.08; 95% CI 0.03–0.13).

Conclusions

complex interventions involving holistic assessment and care planning increased the chance of living at home, reduced mortality and improved cognitive function and some ADLs.

Keywords: aged, Geriatric Assessment, independent living, quality of life, Community Health Services, systematic review, older people

Key Points

Community-based complex interventions for older adults have heterogeneous components.

Most community-based complex interventions for older adults involved holistic assessment and care planning.

Nurses were the most frequent care coordinators in multidisciplinary care.

Complex interventions increased the chance of living at home, but not quality of life, amongst community-dwelling older adults.

Complex interventions also reduced their mortality, enhanced cognitive function and improved some activities of daily living.

Background

The world’s population is ageing rapidly [1]. Although the speed and pattern of population ageing vary by country, the growing proportion of older adults challenges hospital-centric healthcare systems [2]. Hospital admission is expensive, and the focus of most hospital care on single conditions is poorly aligned with the needs of older adults with multimorbidity, polypharmacy and frailty [3]. In hospital settings, a range of complex interventions has been developed to meet the care needs of older adults, including Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), other kinds of discharge planning and more complex reorganisations of care [4]. CGA takes a multidisciplinary approach to a holistic assessment of needs, with coordinated health and social care to address those needs. Although there is evidence that CGA is an effective intervention in hospital inpatients [5], the evidence of effectiveness in the community is less clear.

Community-based complex interventions decrease the risk of unplanned hospital admissions amongst older adults at risk of poor health outcomes [6], and there is some evidence they improve quality of life (QoL) and reduce caregiver burden [7]. However, previous reviews have not evaluated other critical outcomes regarding independent living, such as living at home and institutionalisation [6, 7]. Additionally, although reviews often focus on how researchers classify or name their interventions (e.g. in reviews of ‘CGA’), interventions with the same name are frequently heterogeneous in their intervention components, whereas interventions with different names often share core components [8]. Such heterogeneity may influence the adoption of evidence and hence the formulation of health and social care policies.

This systematic review with meta-analysis, therefore, aims to summarise current evidence on the effectiveness of community-based complex interventions (irrespective of how they are named) intended to improve independent living and QoL of older adults.

Methods

Full methods are reported in Box 1, Supplementary file, and briefly reported here. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021274017). Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in high-income countries which recruited community-dwelling adults that either explicitly targeted older adults or where the mean participant age was ≥65 years. Community-dwelling was defined as living independently at home (including in extra-care housing but excluding care/nursing home residents) regardless of the need for care assistance.

Interventions

Complex interventions include several interacting components [9], which we classified in terms of the Taxonomy of Health Systems Interventions published by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care [10] and the NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) multimorbidity guideline document [8] (Table S1). RCTs where the only intervention was health education workshops or group activities without individual assessment or delivery of care to individuals were excluded.

Comparators

The comparator was ‘usual care’ in the setting the study was based in. RCTs offering minor enhancements to usual care in the control arm, such as written educational materials, were also eligible if they explicitly stated the content of additional components.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes examined were living at home and QoL. Living at home was defined either as a reported outcome or the inverse of mortality and institutionalisation (admission to a care or nursing home) combined at the end of follow-up. QoL had to be measured by validated self-reported outcome instruments (any of Short Form (SF)-12, SF-36, EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, 15D, QUAL-E and Cantril’s Ladder). Secondary outcomes included mortality, hospitalisation (≥1 during follow-up), institutionalisation (≥1 during follow-up), cognitive function (measured by validated instruments) and functional status (measured by validated assessments of activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), combined ADLs/IADLs or physical mobility).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Six electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library) and three trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ICTRP) were searched from inception to February 2022. Search strategies are defined in Box 2, Supplementary file, with additional hand-searching of reference lists. Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/) was used for data management, with title, abstract and full-text screening done by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, involvement of a third reviewer.

Data extraction, risk of bias assessment and quality of evidence assessment

Characteristics and outcome data of the eligible studies were extracted by a single reviewer with validation by a second reviewer, using the pre-specified data extraction sheet. Risk of bias assessment was conducted for all included studies using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs-2 [11]. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was adopted for the assessment of the overall quality of evidence of meta-analyses [12].

Data synthesis

Meta-analysis

Dichotomous outcomes, including living at home, mortality, hospitalisation and institutionalisation were synthesised using risk ratios (RRs) and continuous outcomes, including QoL, cognitive function and functional status were pooled using standardised mean differences (SMDs). A fixed-effects model was used when the heterogeneity was low (I2 < 30%), and a random-effects model otherwise [13]. For RCTs with multiple periods of follow-up, only the outcome results from the longest follow-up were pooled in meta-analyses [13], and only results from intention-to-treat analyses were synthesised [14]. Results from per-protocol analyses and other unpooled results are shown in Table S2, with unpooled results also synthesised narratively.

Small-study effects were examined using funnel plots and Egger’s regression tests [15]. For the primary outcomes, sensitivity analyses included leave-one-out analysis to explore whether findings were driven by single studies [16] and comparison of pooled results between studies at low/moderate versus high risk of bias [13]. For continuous outcomes, further sensitivity analysis compared pooled results between studies reported in change score from baseline against those reported in follow-up score [17]. For meta-analyses with ≥10 studies [13, 18], subgroup analyses were conducted stratified by: length of follow-up (short- versus medium- versus long-term follow-up); location of intervention delivered (home-only versus non-home settings ± home); frailty, disability or functional decline of participants (present versus absent); multidisciplinary care (scheduled versus not); home/telephone follow-up (scheduled versus not); and self-management (planned versus not).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

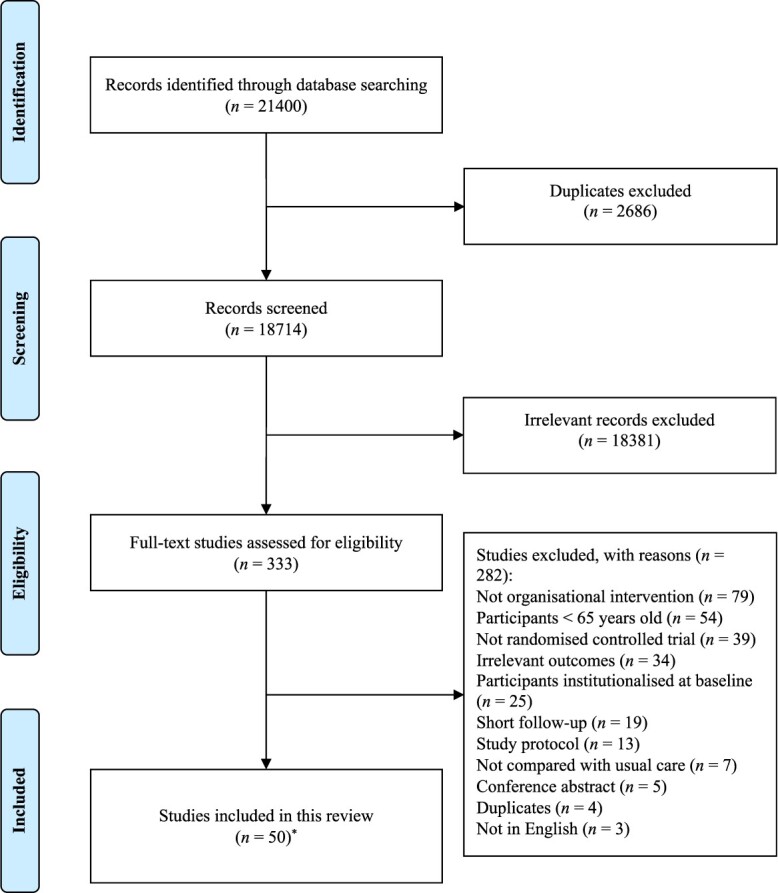

In total, 18,714 unique records were screened, 333 full texts assessed and 50 RCTs conducted between 1984 and 2019 were included in this review (Figure 1). The list of included articles is shown in Box 3, Supplementary file. Fifteen (30%) RCTs took place in the European Union, 14 (28%) in the United States and 3 (6%) in the United Kingdom (Table 1). The majority (n = 37; 74%) of studies adopted frailty, disability or functional decline as an inclusion criterion. Twenty-nine (58%) studies involved interventions provided in day hospitals, general practice surgeries or other health and community care providers. The duration of intervention ranged from 10 weeks to 48 months. A total of 31,659 participants were involved in the studies, with the average age (mean or median) ranging from 69.5 to 86.3 years.

Figure 1.

Flow of literature search and selection. *One RCT was reported across two included papers [19, 20]

Table 1.

Characteristic of included randomised controlled trials

| First author (publication year) | OECD country | Location of intervention delivery | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Duration of intervention | Sample size | Participant age mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beland (2006) | Canada |

|

|

|

22 months | I: 606 C: 624 |

I: Median 82.0; Range 74.0–104.0 C: Median 82.0; Range 64.0–104.0 |

| Bernabei (1998) | Italy |

|

|

Not reported | 12 months | I: 99 C: 100 |

I: 80.7 (7.1) C: 81.3 (7.4) |

| Bleijenberg (2016) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 790 (Screening group) I: 1,446 (Screening + Nurse-Led Care group) C: 856 |

I: 73.5 (8.2) (Screening group) I: 74.0 (8.2) (Screening + Nurse-Led Care group) C: 74.6 (8.8) |

| Blom (2016) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 288 C: 1,091 |

I: Median 82.0; IQR 78.8–86.9 C: Median 83.7; IQR 79.8–88.0 |

| Boult (2011) | United States |

|

|

Not reported | 20 months | I: 404 C: 446 |

I: 77.8; Range 66.0–96.0 C: 77.1; Range 66.0–106.0 |

| Boult (2013) | United States |

|

|

|

32 months | I: 485 C: 419 |

I: 77.2 (SD not reported) C: 78.1 (SD not reported) |

| Brettschneider (2015) | Germany |

|

|

|

18 months | I: 133 C: 145 |

I: 84.9; 3.5 C: 84.7; 3.5 |

| Burns (2000)a | United States |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 60 (Analysed: 49) C: 68 (Analysed: 49) |

I: 71.7; 6.3 C: 70.8; 3.7 |

| Buss (2016)a | Germany |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 32 (Analysed: 24–27) C: 33 (Analysed: 28–31) |

I: 81.8; 8.4 C: 83.0; 7.5 |

| Caplan (2004)b | Australia |

|

|

|

18 months | I: 370 (Analysed: 293–370) C: 369 (Analysed: 282–369) |

I: 82.1; 6.6 C: 82.4; 5.2 |

| Coleman (1999) | United States |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 96 C: 73 |

I: 77.3 (SD not reported) C: 77.4 (SD not reported) |

| Counsell (2007) | United States |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 474 C: 477 |

I: 71.8; 5.6 C: 71.6; 5.8 |

| Di Pollina (2017) | Switzerland |

|

|

|

36 months | I: 122 C: 179 |

I: 81.8; 8.2 C: 81.9; 8.2 |

| Dolovich (2019) | Canada |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 158 C: 154 |

I: 78.1; 6.3 C: 79.06; 6.6 |

| Engelhardt (1996) | United States |

|

|

|

16 months | I: 80 C: 80 |

I: 71.7; 6.8 C: 72.6; 5.8 |

| Fabacher (1994)a | United States |

|

|

Not reported | 12 months | I: 131 (Analysed: 100) C: 123 (Analysed: 95) |

I: 73.5; 4.3 C: 71.8; 7.0 |

| Ford (2019)a | United Kingdom |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 24 (Analysed: 18) C: 28 (Analysed: 23) |

I: 80.4; 8.7 C: 77.2; 9.4 |

| Fristedt (2019) | Sweden |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 31 C: 31 |

I: 84.0; 5.1 C: 86.0; 5.7 |

| Gitlin (2006) | United States |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 160 C: 159 |

I: 79.5; 6.1 C: 78.5; 5.7 |

| Godwin (2016)a | Canada |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 121 (Analysed: 95) C: 115 (Analysed: 86) |

I: 85.3; 4.5 C: 85.7; 3.6 |

| Hendriksen (1984) | Denmark |

|

|

Not reported | 36 months | I: 285 C: 287 |

I: Median 78.4; Range 75–96 C: Median 78.6; Range 75–95 |

| Hoogendijk (2016) | Netherlands |

|

|

Not reported | 24 months | I: 1,147 C: 1,147 |

I: 80.5; 7.5 C: 80.5; 7.5 |

| Kerse (2014)a | New Zealand |

|

|

|

36 months | I: 2,049 (Analysed: 1,553–2,049) C: 1,844 (Analysed: 1,428–1,844) |

I: 80.4; 4.6 C: 80.3; 4.5 |

| Kono (2012) | Japan |

|

|

Not reported | 24 months | I: 161 C: 162 |

I: 80.3; 6.7 C: 79.6; 6.4 |

| Lewin (2013) | Australia |

|

|

Not reported | 12 months | I: 375 C: 375 |

I: 82.7; 7.7 C: 81.8; 7.2 |

| Lihavainen (2012) | Finland |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 404 C: 377 |

I: 81.0; 4.9 C: 81.1; 5.1 |

| Liimatta (2019) | Finland |

|

|

Not reported | 24 months | I: 211 C: 211 |

I: 80.8; 4.3 C: 81.8; 4.3 |

| Markle-Reid (2010)a | Canada |

|

|

Not reported | 6 months | I: 54 (Analysed: 49) C: 55 (Analysed: 43) |

I: 75–85 (n = 28) I: 86 or older (n = 21) C: 75–85 (n = 22) C: 86 or older (n = 21) |

| Markle-Reid (2006)a | Canada |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 144 (Analysed: 120) C: 144 (Analysed: 122) |

I: 75–85 (n = 90) I: 86 or older (n = 30) C: 75–85 (n = 78) C: 86 or older (n = 44) |

| Metzelthin (2015) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 193 C: 153 |

I: 77.5; 5.3 C: 76.8; 4.9 |

| Newbury (2001)a | Australia |

|

|

Not reported | 12 months | I: 50 (Analysed: 45) C: 50 (Analysed: 44) |

I: Median 80; Range 75–91 C: Median 78.5; Range 75–88 |

| Parsons (2017) | New Zealand |

|

|

|

24 months | I: 56 C: 57 |

I: 82.7; 7.3 C: 83.5; 7.6 |

| Parsons (2013) | New Zealand |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 108 C: 97 |

I: 79.1; 6.9 C: 76.9; 7.6 |

| Ploeg (2010)b | Canada |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 361 (Analysed: 331–361) C: 358 (Analysed: 314–358) |

I: 81.0; 4.1 C: 81.3; 4.4 |

| Radwany (2014) | United States |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 40 C: 40 |

I: 69.5 (SD not reported) C: 68.8 (SD not reported) |

| Reuben (1999)a | United States |

|

|

|

15 months | I: 180 (Analysed: 176) C: 183 (Analysed: 175) |

I: 75.8; 6.1 C: 75.9; 5.7 |

| Rosstad (2017) | Norway |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 163 C: 141 |

I: 83.1; 5.7 C: 82.4; 5.7 |

| Sahlen (2006) | Sweden |

|

|

Not reported | 24 months | I: 248 C: 346 |

I: 79.7; 3.9 C: 79.8; 4.3 |

| Salisbury (2018) | United Kingdom |

|

|

|

15 months | I: 797 C: 749 |

I: 71.0; 11.6 C: 70.7; 11.4 |

| Shapiro (2002) | United States |

|

|

|

18 months | I: 40 C: 65 |

I: 77.7 (SD not reported) C: 77.1 (SD not reported) |

| Sherman (2016) | Sweden |

|

|

Not reported | 12 months | I: 176 C: 262 |

I: 75 (SD not reported) C: 75 (SD not reported) |

| Spoorenberg (2018) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 747 C: 709 |

I: 80.6; 4.5 C: 80.8; 4.7 |

| Stuck (1995)b | United States |

|

|

|

36 months | I: 215 C: 199 |

I: 81.0; 3.9 C: 81.4; 4.2 |

| Suijker (2016) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

12 months | I: 1,209 C: 1,074 |

I: Median 82.6; Range 76.8–86.8 C: Median 82.9; Range 77.3–87.3 |

| Szanton (2011)a | United States |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 24 C: 16 |

I: 79.0; 8.2 C: 77.0; 7.1 |

| Thomas (2007) | Canada |

|

|

Not reported | 48 months | I: 175 (Intervention 1 group); 170 (Intervention 2 group) C: 175 |

I: 80.7; 4.3 (Intervention 1 group) I: 80.4; 4.4 (Intervention 2 group) C: 80.7; 4.5 |

| Tuntland (2015)a | Norway |

|

|

|

10 weeks | I: 31 (Analysed: 25–28) C: 30 |

I: 79.9; 10.4 C: 78.1; 9.8 |

| van Hout (2010) | Netherlands |

|

|

|

18 months | I: 331 C: 320 |

I: 81.3; 3.9 C: 81.5; 4.3 |

| Walters (2017) | United Kingdom |

|

|

|

6 months | I: 26 C: 25 |

I: 80.38; 6.89 C: 79.68; 6.36 |

| Zimmer (1985)a | United States |

|

|

Not reported | 6 months | I: 82 C: 76 |

I: 73.8 (SD not reported) C: 77.4 (SD not reported) |

C, control group; I, intervention group; INTERMED-E-SA, The INTERMED for the Elderly Self-Assessment; ISAR-PC, Identification of Seniors At Risk—Primary Care; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.

aStudies adopted per-protocol analysis for all outcomes.

bStudies adopted per-protocol analysis for some outcomes (further detailed in Table S2).

Descriptions of interventions and comparators

Intervention components for each included study are summarised in Table 2, with details documented in Table S3. Forty-seven (94%) RCTs reported using holistic assessment (non-disease-focused) as one of their intervention components, and 45 (90%) studies included care planning, including multidisciplinary care plans, self-management plans or developing care plans for routine primary care management. Amongst the 27 RCTs reporting multidisciplinary care, 8 (29.6%) had their interventions delivered mainly by primary care teams without the involvement of geriatricians or other specialist clinicians, 12 (44.4%) mainly by secondary care teams without the involvement of primary care professionals and 7 (25.9%) by primary and secondary care teams (Table 3). Over half of the studies involved nurses or advanced practice nurses (APNs; n = 20; 74.1%), general practitioners (GP; n = 15; 55.6%) and/or physiotherapists (n = 14; 51.9%) as care coordinators. In 18 (66.7%) studies, nurses or APNs were responsible for coordinating the multidisciplinary care. Fourteen (28%) and eight (16%) studies provided their participants with home and telephone follow-up only, respectively, with 10 (20%) others providing both. Finally, a total of 16 RCTs reported the adoption of planned self-management as an intervention component (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intervention components of the included randomised controlled trials

| Study | Component of intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holistic assessment | Multidisciplinary care | Care plan development | Home follow-up | Telephone follow-up | Self-management | |

| Beland (2006) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Bernabei (1998) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Bleijenberg (2016) | ●a | ● | ●a | ●a | ||

| Blom (2016) | ● | ● | ||||

| Boult (2011) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Boult (2013) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Brettschneider (2015) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Burns (2000) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Buss (2016) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Caplan (2004) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Coleman (1999) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Counsell (2007) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Di Pollina (2017) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Dolovich (2019) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Engelhardt (1996) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Fabacher (1994) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Ford (2019) | ● | ● | ||||

| Fristedt (2019) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Gitlin (2006) | ● | ● | ||||

| Godwin (2016) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Hendriksen (1984) | ● | |||||

| Hoogendijk (2016) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Kerse (2014) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Kono (2012) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Lewin (2013) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Lihavainen (2012) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Liimatta (2019) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Markle-Reid (2006) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Markle-Reid (2010) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Metzelthin (2015) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Newbury (2001) | ● | ● | ||||

| Parsons (2013) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Parsons (2017) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Ploeg (2010) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Radwany (2014) | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Reuben (1999) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Rosstad (2017) | ● | ● | ||||

| Sahlen (2006) | ● | ● | ||||

| Salisbury (2018) | ● | ● | ||||

| Shapiro (2002) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Sherman (2016) | ● | ● | ||||

| Spoorenberg (2018) | ●b | ●b | ●b | ●b | ● | |

| Stuck (1995) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Suijker (2016) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Szanton (2011) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Thomas (2007) | ● | |||||

| Tuntland (2015) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| van Hout (2010) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Walters (2017) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Zimmer (1985) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Number (%) of studies with each component | 47 (94) | 27 (54) | 45 (90) | 24 (48) | 18 (36) | 16 (32) |

aOnly applicable to Screening + Nurse-Led Care group.

bOnly applicable to Complex Care Needs group and Frail group.

Table 3.

Composition of multidisciplinary teams in the included randomised controlled trials

| Study | Level of care team | Involved health care or social care professionals | Case coordinator(s) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | APN | GP | Geriatrician | Other specialist doctors | Dentist | Social worker | Physiotherapist | Occupational therapist | Dietitian or nutritionist | Speech therapist | Pharmacist | Psychologist | |||

| Beland (2006) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | N or SW | |||||||

| Bernabei (1998) | Primary and Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | Details not reported | |||||||||

| Bleijenberg (2016)a | Primary | ● | ● | APN | |||||||||||

| Burns (2000) | Primary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN or GP or SW or Psy | ||||||||

| Caplan (2004) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | N | |||||

| Counsell (2007) | Primary and Secondary | ● | ● | ● | APN and SW | ||||||||||

| Di Pollina (2017) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | N | ||||||

| Engelhardt (1996) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | G | ||||||||||

| Fristedt (2019) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | G | |||||||||

| Hoogendijk (2016) | Primary and Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN and G | ||||||||

| Kerse (2014) | Primary and Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN and GP | |||||||

| Kono (2012) | Primary and Secondary | ● | ● | ● | APN and SW and CM | ||||||||||

| Lewin (2013) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | N and PT and OT | ||||||||||

| Lihavainen (2012) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | N | ||||||||

| Markle-Reid (2010) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | CM | |||||||||

| Metzelthin (2015) | Primary | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN | |||||||||

| Parsons (2013) | Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | N | |||||||||

| Ploeg (2010) | Primary | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN | ||||||||

| Spoorenberg (2018)b | Primary + Secondary | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN or SW | |||||||||

| Suijker (2016) | Primary | ● | ● | ● | ● | APN | |||||||||

| Szanton (2011) | Secondary | ● | ● | N and OT | |||||||||||

| Tuntland (2015) | Primary | ● | ● | PT and OT | |||||||||||

| Zimmer (1985) | Primary | ● | ● | ● | APN or GP or SW | ||||||||||

| Dolovich (2019) | Primary | Team composition not reported | GP | ||||||||||||

| Ford (2019) | Primary and Secondary | Team composition not reported | GP | ||||||||||||

| Markle-Reid (2006) | Secondary | Team composition not reported | N | ||||||||||||

| Shapiro (2002) | Secondary | Team composition not reported | CM | ||||||||||||

CM, care manager (profession not reported); G, geriatrician; N, nurse; OT: occupational therapist; Psy, psychologist; PT, physiotherapist; SW, social worker.

aOnly applicable to Screening + Nurse-Led Care group.

bOnly applicable to Complex Care Needs group and Frail group.

Three (6%) RCTs reported the use of additional components to enhance usual care, including the provision of health educational materials [19–21] and standard needs assessment [22].

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment is shown in Table S4. Overall, 11 were low risk of bias, 25 moderate and 14 at high risk. Twenty-seven studies had moderate risk of bias for not reporting details on randomisation and/or allocation sequence concealment, and one [23] was at high risk of bias for not concealing allocation sequence. Thirteen RCTs were at high risk of bias because they adopted per-protocol analysis for all outcomes, and three [24–26] had moderate risk of bias for not implementing the intention-to-treat analysis on all outcomes. Twenty-three studies had moderate risk of bias in the selection of reported results for not providing accessible study protocols.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

Living at home

In 11 RCTs with 4,538 participants, interventions were significantly superior to usual care in increasing the likelihood of older adults living at home (RR 1.05; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00–1.10; P = 0.048; I2 = 46%; GRADE moderate-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S1). In the sensitivity analysis, there was no significant difference (P = 0.46) between studies at low/moderate versus high risk of bias. The leave-one-out analysis found that the significance of the pooled results was sensitive to seven studies (results became non-significant) [22, 23, 27–31] (Table S5). Little evidence of small-study effects was observed (Egger’s test: P = 0.21).

Table 4.

Effect estimates and quality of evidence ratings for all outcomes

| Dichotomous outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Number of RCTs (Number of participants) |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Pooled result in RR (95% CI) |

P | I 2 | Quality of evidence |

| Living at home | 12 (4538) | No | Serious | No | No | Not detected | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) |

0.048 | 46% |

◯

◯Moderate |

| Mortality | 20 (9455) | No | No | No | No | Not detected | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) |

0.007 | 9% |

High |

| Hospitalisation | 15 (6244) | No | Very serious | No | No | Not detected | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) |

0.19 | 59% |

◯◯

◯◯Low |

| Institutionalisation | 15 (5231) | No | No | No | No | Not detected | 0.89 (0.75–1.04) |

0.14 | 23% |

High |

| Continuous outcomes | ||||||||||

| Outcome | Number of RCTs (Number of participants) |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Pooled result in SMD (95% CI) |

P | I 2 | Quality of evidence |

| QoL (overall) |

9 (9460) | No | No | No | No | Not assessed | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.05) |

0.72 | 0% |

High |

| QoL (physical component) |

6 (5902) | No | Very serious | No | No | Not assessed | 0.00 (−0.08 to 0.08) |

0.97 | 54% |

◯◯

◯◯Low |

| QoL (mental component) |

6 (5902) | No | Very serious | No | No | Not assessed | 0.07 (−0.02 to 0.16) |

0.11 | 59% |

◯◯

◯◯Low |

| Cognitive function | 5 (2149) | No | No | No | No | Not assessed | 0.12 (0.02–0.22) |

0.02 | 0% |

High |

| Functional status (ADL) |

6 (2476) | No | Serious | No | No | Not assessed | 0.10 (0.00–0.20) |

0.052 | 26% |

◯

◯Moderate |

| Functional status (IADL) |

4 (1687) | No | No | No | No | Not assessed | 0.11 (0.01–0.21) |

0.02 | 0% |

High |

| Functional status (Combined ADL and IADL) |

5 (7751) | No | No | No | No | Not assessed | 0.08 (0.03–0.13) |

0.002 | 0% |

High |

QoL (overall)

In nine RCTs with 9,460 participants, interventions made little or no difference to overall QoL in older adults (SMD 0.01; 95% CI –0.04 to 0.05; P = 0.72; I2 = 0%; GRADE high-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S2). Neither of the two unpooled RCTs reported significant results on the outcome (Table S2). In the leave-one-out analysis, the significance of the pooled results was not sensitive to any individual studies (Table S5).

QoL (physical component)

In six RCTs with 5,902 participants, interventions had little or no effect on the physical component of QoL (SMD 0.00; 95% CI –0.08 to 0.08; P = 0.97; I2 = 54%; GRADE low-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S3). Neither of the two unpooled RCTs reported significant impacts on the outcome (Table S2). No significant difference (P = 0.41) was identified between studies reporting change scores from the baseline versus studies reporting follow-up scores. The significance of the pooled results was not sensitive to any individual study (Table S5).

QoL (mental component)

In six RCTs with 5,902 participants, interventions had little or no effect on the mental component of QoL (SMD 0.07; 95% CI –0.02 to 0.16; P = 0.11; I2 = 59%; GRADE low-quality evidence) (Table 4). The single unpooled RCT did not report significant results on the outcome (Table S2). There was a significant difference (P = 0.01) between studies (n = 3) reporting change scores from the baseline and the single study reporting scores at the end of follow-up (Figure S4), with the latter [32] having a positive result. The significance of the pooled results was sensitive to van Hout et al. [33] (results became significant) (Table S5).

Secondary outcomes

Mortality

In 20 RCTs with 9,455 participants, interventions reduced mortality in older adults (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.77–0.96; P = 0.007; I2 = 9%; GRADE high-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S5). Only one [19, 20] of the six unpooled RCTs reported that the interventions were superior to usual care in reducing mortality at 12-month follow-up (Table S2). Little evidence of small-study effects was observed (Egger’s test: P = 0.10).

Hospitalisation

In 15 RCTs with 6,244 participants, interventions had little or no effect on hospitalisation (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.84–1.03; P = 0.19; I2 = 59%; GRADE low-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S6). None of the five unpooled RCTs reported significant results for hospitalisation (Table S2). Little evidence of small-study effects was observed (Egger’s test: P = 0.56).

Institutionalisation

In 15 RCTs with 5,231 participants, interventions had little or no effect on institutionalisation (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.75–1.04; P = 0.14; I2 = 23%; GRADE high-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S7). None of the four unpooled RCTs reported significant results for institutionalisation (Table S2). Little evidence of small-study effects was observed (Egger’s test: P = 0.21).

Cognitive function

In five RCTs with 2,149 participants, interventions were effective in improving cognitive function (SMD 0.12; 95% CI 0.02–0.22; P = 0.02; I2 = 0%; GRADE high-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figure S8). One [34] of the two unpooled RCTs reported that the interventions were superior to usual care in slowing down cognitive decline at 12-month follow-up (Table S2).

Functional status (ADLs, IADLs and combined ADLs/IADLs)

In six RCTs with 2,476 participants, interventions had little or no effect on ADLs (SMD 0.10; 95% CI 0.00–0.20; P = 0.052; I2 = 26%; GRADE moderate-quality evidence) amongst older adults associated with complex interventions (Table 4 and Figure S9). However, one [35] of the two unpooled RCTs reported that the interventions were more effective than usual care in improving ADLs at 12-month follow-up (Table S2). Interventions had positive effects on IADLs (SMD 0.11; 95% CI 0.01–0.21; P = 0.02; I2 = 0%; four RCTs with 1,687 participants; GRADE high-quality evidence) and combined ADLs/IADLs (SMD 0.08; 95% CI 0.03–0.13; P = 0.002; I2 = 0%; five RCTs with 7,751 participants; GRADE high-quality evidence) (Table 4 and Figures S10 and S11). Although neither of the two unpooled RCTs measuring IADLs reported significant results, the unpooled RCT measuring combined ADLs/IADLs showed that the interventions were more effective than usual care at 12-month follow-up (Table S2). Amongst these three outcomes, no significant differences (P = 0.62; P = 0.74; P = 0.91) were identified between studies reporting change scores from the baseline versus studies reporting follow-up scores.

Functional status (physical mobility)

Four RCTs measured the change in physical mobility of 1,475 participants. Compared with usual care, interventions reduced self-reported difficulties in walking at 36-month follow-up [36], improved the Short Physical Performance Battery overall, balance and gait speed scores at 6-month follow-up [37] and increased the total hand grip strength at 6-month follow-up [38] (Table S2).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses found that the location of intervention delivered (P = 0.01), home/telephone follow-up (P = 0.03) and self-management (P = 0.03) modified the effect of community-based complex interventions on institutionalisation (Figures S12–S14). Home-based interventions were associated with a lower institutionalisation rate amongst older adults (RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.48–0.87; P = 0.004; I2 = 0%). Interventions involving scheduled home/telephone follow-up (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.60–0.93; P = 0.01; I2 = 17%) or self-management (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.38–0.88; P = 0.01; I2 = 0%) also reduced institutionalisation rate amongst the population. However, the covariates in the analyses were unevenly distributed, meaning that the findings should be interpreted with caution [18]. No significant difference was identified in analyses of subgroups defined by length of follow-up, frailty, disability or functional decline of participants, or multidisciplinary care.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This systematic review found that holistic assessment and care plan development are the core components of >90% community-based complex interventions for improving independent living and QoL of older adults. Meta-analyses showed that interventions increased the likelihood of living at home (moderate-quality evidence) but had little to no effect on improving QoL (high-quality evidence for overall QoL; low-quality evidence for physical and mental components of QoL). Interventions also reduced mortality (high-quality evidence) and improved cognitive function (high-quality evidence), IADLs (high-quality evidence) and combined ADLs/IADLs (high-quality evidence). Although there was no impact on institutionalisation in the main analysis, subgroup analysis found significant reductions in institutionalisation for interventions delivered at home, with scheduled home/telephone follow-up, or with planned self-management.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this review include the performance of a comprehensive literature search in multiple databases and the adoption of the GRADE approach to evaluate quality of evidence. The review is also distinctive in including a wide range of trials with similar intervention components rather than searching based on the labels given to the intervention by researchers (e.g. CGA). Although the heterogeneity of interventions was a potential limitation, considerable heterogeneity within studies with the same label was also present [4, 8].

There are several further limitations. First, intervention components were variably and very likely incompletely reported by many studies. For this reason, we did not attempt network meta-analysis. Similarly, the limited number of studies and imbalanced covariates between subgroups meant that meta-regression could not be robustly applied [13]. Instead, we used subgroup analysis to explore potential effect modifiers of multifaceted interventions, but interpretation should be cautious given variable reporting, and some subgroup analyses were not possible (for example, further analysis of subgroups defined by multidisciplinary team make-up and the status or degree of frailty of the participants in the primary studies, because of lack of provision of this information in the original papers). Second, some studies did not report mortality, hospitalisation and institutionalisation in a way which could be pooled in meta-analyses, so could only be synthesised narratively. Third, mortality was not accounted for as a competing risk in individual study analyses [39]. Given the intervention impact on mortality, the interpretation of effects on hospitalisation and institutionalisation should be cautious. Fourth, given the variability in health and social care systems and infrastructures, the findings in this review may not be applicable in all settings. Finally, as only studies published in English were eligible for inclusion, the effect sizes in this review might have been overestimated or underestimated.

Comparisons with other reviews

Ellis et al. [5] found high-quality evidence that inpatient CGA increased the chance of living at home at discharge and decreased nursing home admissions but had no effect on mortality. Chen et al. [7] found that inpatient and community-based CGA improved the QoL of older adults, but the effects were not significant in the community-based subgroups. In reviews of interventions for community-dwelling older adults, Briggs et al. [6] found a decreased risk of hospital admissions but no effect on mortality and nursing home admissions, and Wong et al. [40] reported possible benefits on the mental component of QoL but not on overall and the physical component of QoL, or on ADL/IADL. The review [8] for the NICE multimorbidity guidelines mentioned that complex interventions had limited benefits in critical outcomes (e.g. mortality and QoL). Our study found evidence of benefits for some outcomes (living at home, mortality, cognitive function, IADLs and combined ADLs/IADLs) but not others (QoL, hospitalisation or institutionalisation). The more favourable findings may be because we included a larger range of complex interventions (with shared core components) rather than only including interventions with specific labels such as ‘CGA’ (which is not a homogeneous group either, given variable intervention components).

Implications for practice

We focused this review on complex interventions for community-dwelling older adults with similar components instead of relying on intervention labels, such as CGA. Two near ubiquitous components were identified: (i) holistic assessment (94% of trials) and (ii) care plan development (90% of trials), and these should therefore be considered as the cores for health services planning to implement such interventions. There was some evidence that scheduled home/telephone follow-up and self-management positively modified the effect of complex interventions on institutionalisation. There was no clear evidence that multidisciplinary care was beneficial, although its component was poorly reported by the included studies. Before implementing holistic assessment, organisers should ensure the trust between health and social care professionals carrying out the task and facilitate inter-professional communications [41]. The scope of assessment should also balance the needs of older adults with complicated problems and the limited assessment time [41]. However, specialist staff may not be necessary to in-home assessment for an ideal model of complex interventions [42, 43].

Implications for research

A weakness of the existing literature is poor reporting of both intervention components and ‘usual care’, including the lack of clarity about multidisciplinary team composition and the frequency and duration of intervention components. Detailed reporting using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication [44] or the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare 2 [45] checklists would significantly improve interpretation and future evidence synthesis. Similarly, the trials examined in this review varied considerably in the outcomes measured, and how outcomes were measured. The use of a core outcome set with standardised instruments in future trials would ensure that future evidence is more comparable and easier to synthesise [46]. The core outcome set development should involve a panel of key stakeholders who will utilise, deliver and/or evaluate the complex interventions (i.e. researchers, clinicians, policy-makers, older adults and caregivers) in the form of Delphi surveys or semi-structured group discussions [46]. Outcomes for research on geriatric rehabilitation [47], older adults with frailty [48] and participants with multimorbidity [49], including health-related QoL, ADL/IADL and mental health, may also be adopted.

Conclusions

Holistic assessment and care plan development are the common components of complex interventions for improving independent living and QoL of community-dwelled older adults. Complex interventions increased the likelihood of living at home but had little to no effect on improving QoL. They reduced mortality and improved cognitive function, IADLs and combined ADLs/IADLs. Subgroup analyses suggested that complex interventions involving scheduled home/telephone follow-up or self-management might reduce institutionalisation rate amongst older adults; however, further evidence is needed to confirm such findings.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Leonard Ho, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Stephen Malden, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Kris McGill, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Michal Shimonovich, MRC/CSO Social & Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

Helen Frost, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Navneet Aujla, Population Health Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Iris S-S Ho, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Susan D Shenkin, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; Ageing and Health Research Group, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Barbara Hanratty, Population Health Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Stewart W Mercer, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Bruce Guthrie, Advanced Care Research Centre, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

The study was funded by Legal and General PLC (as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility programme, providing a research grant to establish the independent Advanced Care Research Centre at the University of Edinburgh). The funder had no role in conduct of the study, interpretation or the decision to submit for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All study data is provided in the paper and supplementary material.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Ageing and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed 13 March 2023).

- 2. Lorenzoni L, Marino A, Morgan D, et al. Health Spending Projections to 2030. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/5667f23d-en (accessed 31 January 2023).

- 3. Aggarwal P, Woolford SJ, Patel HP. Multi-morbidity and polypharmacy in older people: challenges and opportunities for clinical practice. Geriatrics 2020; 5. 10.3390/geriatrics5040085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K et al. What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing 2018; 47: 149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 2017: Cd006211. 10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Briggs R, McDonough A, Ellis G et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for community-dwelling, high-risk, frail, older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022; 2022: Cd012705. 10.1002/14651858.CD012705.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Z, Ding Z, Chen C et al. Effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention on quality of life, caregiver burden and length of hospital stay: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21: 377. 10.1186/s12877-021-02319-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Multimorbidity: Clinical Assessment and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008; 337: a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cochrane Collaboration Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy 2021. 10.5281/zenodo.5105851 (accessed 14 July 2023). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019; 366: l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryan R, Hill S. How to GRADE the Quality of the Evidence. London, UK: Cochrane Collaboration, http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources (accessed 11 January 2023).

- 13. The Cochrane Collaboration . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. London, UK: Cochrane Collaboration, https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed 11 January 2023).

- 14. Leroy JL, Frongillo EA, Kase BE et al. Strengthening causal inference from randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ Glob Health 2022; 7: e008597. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol 2008; 37: 1148–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fu R, Holmer HK. Change score or follow-up score? Choice of mean difference estimates could impact meta-analysis conclusions. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 76: 108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richardson M, Garner P, Donegan S. Interpretation of subgroup analyses in systematic reviews: a tutorial. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2019; 7: 192–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Winter L et al. Effect of an in-home occupational and physical therapy intervention on reducing mortality in functionally vulnerable older people: preliminary findings. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 950–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Corcoran M, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Radwany SM, Hazelett SE, Allen KR et al. Results of the promoting effective advance care planning for elders (PEACE) randomized pilot study. Popul Health Manag 2014; 17: 106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parsons M, Senior H, Kerse N, Chen MH, Jacobs S, Anderson C. Randomised trial of restorative home care for frail older people in New Zealand. Nurs Older People 2017; 29: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewin G, De San MK, Knuiman M et al. A randomised controlled trial of the Home Independence Program, an Australian restorative home-care programme for older adults. Health Soc Care Community 2013; 21: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department--the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ploeg J, Brazil K, Hutchison B et al. Effect of preventive primary care outreach on health related quality of life among older adults at risk of functional decline: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1480. 10.1136/bmj.c1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A et al. A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kono A, Kanaya Y, Fujita T et al. Effects of a preventive home visit program in ambulatory frail older people: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012; 67A: 302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hendriksen C, Lund E, Strømgård E. Consequences of assessment and intervention among elderly people: a three year randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 1984; 289: 1522–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brettschneider C, Luck T, Fleischer S et al. Cost-utility analysis of a preventive home visit program for older adults in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 141. 10.1186/s12913-015-0817-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas R, Worrall G, Elgar F, Knight J. Can they keep going on their own? A four-year randomized trial of functional assessments of community residents. Can J Aging 2007; 26: 379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shapiro A, Taylor M. Effects of a community-based early intervention program on the subjective well-being, institutionalization, and mortality of low-income elders. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007; 298: 2623–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Hout HP, Jansen AP, van Marwijk HW, Pronk M, Frijters DF, Nijpels G. Prevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN05358495]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010; 65: 734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bernabei R, Landi F, Gambassi G et al. Randomised trial of impact of model of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. BMJ 1998; 316: 1348–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spoorenberg SLW, Wynia K, Uittenbroek RJ, Kremer HPH, Reijneveld SA. Effects of a population-based, person-centred and integrated care service on health, wellbeing and self-management of community-living older adults: a randomised controlled trial on embrace. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0190751. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lihavainen K, Sipilä S, Rantanen T, Kauppinen M, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Effects of comprehensive geriatric assessment and targeted intervention on mobility in persons aged 75 years and over: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2012; 26: 314–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parsons JG, Sheridan N, Rouse P, Robinson E, Connolly M. A randomized controlled trial to determine the effect of a model of restorative home care on physical function and social support among older people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 1015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walters K, Frost R, Kharicha K et al. Home-based health promotion for older people with mild frailty: the HomeHealth intervention development and feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess 2017; 21: 1–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buzkova P. Competing risk of mortality in association studies of non-fatal events. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0255313. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wong KC, Wong FKY, Yeung WF, Chang K. The effect of complex interventions on supporting self-care among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2018; 47: 185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sum G, Nicholas SO, Nai ZL, Ding YY, Tan WS. Health outcomes and implementation barriers and facilitators of comprehensive geriatric assessment in community settings: a systematic integrative review [PROSPERO registration no.: CRD42021229953]. BMC Geriatr 2022; 22: 379. 10.1186/s12877-022-03024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Donaghy E, Still F, Frost H et al. GP-led adapted comprehensive geriatric assessment for frail older people: a multi-methods evaluation of the `Living Well Assessment' quality improvement project in Scotland. BJGP Open 2023; 7. 10.3399/bjgpo.2022.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jones H, Anand A, Morrison I et al. Impact of mid-med, a general practitioner-led model of care for patients with frailty. Age Ageing 2023; 52: afad006. 10.1093/ageing/afad006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 348: g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Möhler R, Köpke S, Meyer G. Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). Trials 2015; 16: 204. 10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a ‘Core outcome set’ - a practical guideline. Trials 2016; 17: 449. 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Demers L, Ska B, Desrosiers J, Alix C, Wolfson C. Development of a conceptual framework for the assessment of geriatric rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2004; 38: 221–37. 10.1016/j.archger.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Prorok JC, Williamson PR, Shea B et al. An international Delphi consensus process to determine a common data element and core outcome set for frailty: FOCUS (The Frailty Outcomes Consensus Project). BMC Geriatr 2022; 22: 284. 10.1186/s12877-022-02993-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith SM, Wallace E, Salisbury C, Sasseville M, Bayliss E, Fortin M. A Core Outcome Set for Multimorbidity Research (COSmm). Ann Fam Med 2018; 16: 132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data is provided in the paper and supplementary material.