Abstract

Unilateral proptosis is an abnormality in which one eye sticks out forward more than the other. Bulging of the eye is commonly seen in Graves’ ophthalmopathy, but it’s mostly bilateral. Thyroid eye disease presents as the most common extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease, and rarely leads to unilateral proptosis. A 25-year-old female with a history of weight loss, menstrual irregularities, and palpitations presented with progressive right eye bulging, which was further confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging and biochemical investigations. Magnetic resonance imaging of the orbit revealed unilateral extraocular muscle enlargement and enhancement with sparing of the tendons. Timely therapy is crucial for reversing the ocular manifestations of thyroid eye disease.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, unilateral proptosis, autoimmune, Graves’ ophthalmopathy, thyroid eye disease

Introduction

The most common extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease (GD) is thyroid eye disease (TED) 1 observed in 25–50% of the Graves’ patients. A total of 75% of the patients with thyrotoxicosis develop Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) within a year of diagnosis. 2 TED is an autoimmune disorder that can cause a rise in retrobulbar pressure and proptosis due to inflammation, swelling, and fibrosis of the extraocular muscle (EOM). It is caused by thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins targeting the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSH-R), which can activate it and contribute to the development of TED. 3 In the majority of patients, both eyes are equally affected, although often in an asymmetric manner. 1 Unlike bilateral proptosis, which is mostly seen in thyroid disease, unilateral proptosis has a great variety of differential diagnoses, including orbital pseudotumor, orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, or intra-orbital neoplasms. 4 Unilateral ophthalmopathy mostly progresses to bilateral disease, while only 5–11% of cases show no progression, making pure unilateral ophthalmopathy rare. 1 Here, we present the case of a young female with GD who developed unilateral proptosis without any visual disturbances.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old female presented to the outpatient department with a history of weight loss, menstrual irregularities, and occasional palpitations for 2 months. She had no history of night sweats, fever, chest pain, cough, or shortness of breath. She complained of bulging of her right eye, which was insidious in onset and gradually progressive without any difficulty in vision. There was no history of pain, discharge, redness, or trauma associated with her condition. She had no remarkable prior medical history nor any history of allergies to medication or other substances. She was a nonsmoker but consumed alcohol occasionally.

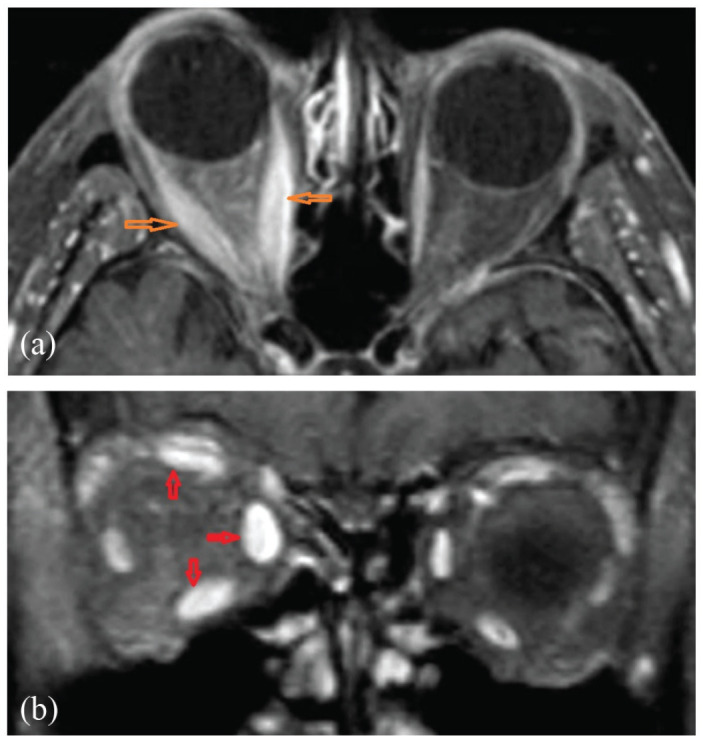

At the time of her presentation to the hospital, she had a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, oxygen saturation of 97% on room air, and a pulse rate of 125 beats/min. On ocular examination, her EOM movements were normal. The visual acuity was 6/6 in both eyes, with a clinical severity score of 3/7, Hertel’s exophthalmometry of 23 mm in the right eye and 21 mm in the left eye. Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 13.6 g/dL and a white blood cell count of 7400/mm3 with 57% neutrophils, 39% lymphocytes, and 3% monocytes. The free T3 level was 10.12 pmol/L (reference range: 3.10–6.80), free T4 level was 25.88 pmol/L (reference range: 12.0–22.0), TSH was 0.006 mIU/L (reference range: 0.27–4.20), and TSH receptor antibody (TRAb) was 3.56 IU/L (>1.75 (96% sensitivity and 99% specificity for GD)). The liver and renal function tests were within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit revealed unilateral EOM enlargement and enhancement with tendon sparing and relative right proptosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Orbital axial and (b) orbital coronal; post-contrast MRI showing unilateral EOM enlargement and enhancement with tendon sparing and relative right proptosis.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; EOM: extraocular muscle.

She was diagnosed with GD with GO and started on methimazole 5 mg twice daily with intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once weekly for 6 weeks, followed by 250 mg once weekly for 6 weeks for a total duration of 12 weeks. On follow-up after 3 months, she responded well to the medication, leading to the resolution of her eye symptoms.

Discussion

Our patient presents with proptosis, weight loss, menstrual irregularities, and palpitations, which are commonly seen in GD. However, our patients present with unilateral proptosis without any visual disturbances, and this is rare.

GD is an autoimmune disorder that is more frequent between 20 and 50 years of age and occurs in 2% of women.4,5 The annual incidence of GO is 16 per 100,000 women. 2 The symptoms of GO include a dry, gritty feeling in the eyes, photophobia, excessive tearing, double vision, and pressure feeling behind the eyes, as reported by nearly half of the patients of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. 6 The most typical symptoms of GO are proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, orbital congestion, eyelid edema, eyelid erythema, conjunctival chemosis, difficulty moving eyes, eyelid retraction, and less frequently, compression of the optic nerve. 5 Proptosis can cause corneal exposure and injury in severe cases, especially if the lids fail to shut during sleep, and in most cases, there is subclinical involvement of the eyes. 6

The most widely accepted cause of Graves’ orbitopathy is the formation of autoantibodies against thyrotropin receptors located in both the thyroid gland and the orbit. This activates T cells, resulting in the release of inflammatory mediators. 7 Inflammatory cells and hyaluronans infiltrate the muscle, causing enlargement of the EOMs, an increase in the orbital fat volume, and ultimately, collagen deposition leading to fibrosis. 8 The disease often progresses via two distinct phases: an active, inflammatory phase followed by a static, non-inflammatory phase with fibrosis. 3

The risk factors for TED as smoking, older age, extreme physical or psychological stress, prior treatment with radioactive iodine, and increased titers of antithyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies are well described in published literature. 9 However, unilateral proptosis can be attributed to several factors, such as an asymmetrical distribution of antigens, anatomical variations in blood flow or lymphatic drainage, the elasticity of orbital septa, or other localized conditions. Infections or differences in the ability to generate adipose tissue can be a potential trigger for unilateral proptosis. 10

The onset of symptoms and unilateral proptosis involves a variety of alternate diagnoses including inflammatory, neoplastic, infectious, vascular, or neuromuscular conditions. 11 Orbital cellulitis is an acute condition that progresses rapidly. Orbital cellulitis mimics GO most frequently but may have a subacute onset over days or weeks, may be associated with pain, and involve any EOM, including the tendons, on MRI of the orbit. 11 The appearance of the extraocular eye muscles in MRI aids in differentiating TED from other conditions such as lymphoma and idiopathic orbital inflammation where the tendons are involved. 9 Neoplastic involvement was a consideration in our patient as it may present as a painless, restrictive eye involvement and occurs gradually over weeks or months, with or without a mass effect. 11 Lymphomas account for more than 50% of malignant orbital tumors in people 60 years and older, making them the most prevalent primary orbital tumors. 11

Computerized tomography (CT) of the orbit, MRI, and TRAb help diagnose GO. Orbital imaging is indicated in a patient with GO, particularly in a patient with unilateral proptosis. 5 In our patient, TRAb was positive with a rise in serum-free T3 and free T4 levels and a fall in TSH, suggesting GO and the high level of antithyroid peroxidase, which may indicate transient hyperthyroidism due to Hashitoxicosis. 12 The TRAb and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor antibodies could have contributed to the pathogenesis of infiltrative ophthalmopathy. 2

Corticosteroids are usually used in the treatment of GO due to their anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. 13 Methimazole is an antithyroid medication for GD but does not directly affect extrathyroidal manifestations like GO. Our patient improved with combined therapy of corticosteroids and antithyroid medications.

Reported cases of unilateral proptosis in GO are shown in Table 1. Among the reported cases, four of them were euthyroid GD and two were hyperthyroid GD with subsequent eye symptoms. Our case reveals unilateral proptosis in hyperthyroid GD with no eye symptoms.

Table 1.

Reported cases of unilateral proptosis in GO.

| Articles | Age (years)/gender | Clinical features | Laboratory findings | Imaging findings | Treatment | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Examination | ||||||

| Michigishi et al. 14 | 39/Female | Left painless proptosis with retraction of upper eyelid | Hard nodule on the right thyroid lobe, Hertel exophthalmometer showed 25 and 18 mm in the left and right eyes, respectively | Normal thyroid function tests; thyroglobulin and TRAb elevated | Enlargement of the left eye muscles without swelling of their tendons in MRI | IV methylprednisolone; subtotal thyroidectomy | Full recovery |

| Arslan et al. 2 | 43/Male | Decreased vision in the right eye after eyelid swelling, burning, and stinging; chemosis; optic neuropathy; and smoker | Hertel exophthalmometer showed 21 and 18 mm in the right and left eyes, respectively | Normal thyroid function tests; Anti-thyroglobulin and anti-peroxidase antibodies negative; TRAb positive; suggest euthyroid GD | Mild enlargement of all EOMs of the right eye without the involvement of the tendons in MRI | Methylprednisolone | Fully recovered; restoration of normal visual acuity and visual field in the right eye |

| Locarzona et al. 15 | 62/Female | Progressive exophthalmos, dilated and tortuous conjunctival blood vessels (corkscrew hyperemia), and chemosis in the right eye | Visual acuity = 20/20 in each eye; asymmetry in the IOP, not increasing in up gaze (Bradley maneuver); normal extraocular motility and fundoscopy | Normal thyroid function; anti-thyroglobulin; and anti-peroxidase positive | Early and abnormal filling of the CS and an enlarged superior ophthalmic vein in neuroimaging suggesting a CCF | Interventional treatment | Recovered with no recurrence |

| Rubinstein 12 | 50/Female | Eye irritation, tearing, visual changes, orbital pain, and proptosis (left more than right) | Hertel exophthalmometer measurements were 20.5 OD, 22.5 OS, base 96 | Normal thyroid function test; Elevated thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin | Enlarged inferior and medial recti muscles (left more than right) without tendon involvement in CT | IV teprotumumab | Partial reduction in proptosis |

| Macovei and Azis 16 | 52/Male | Exophthalmos, eyelid retraction, corneal ulceration, chemosis, pannus formation in the left eye progressing to the right eye, decrease in visual acuity of the right eye, and blurred vision; smoker | Low-grade orbital pain on palpation, normal right eye in fundoscopy | Hyperthyroidism with high levels of FT3, FT4, and low TSH; high levels of TSH-R autoantibodies | Enhancement of the EOM sheaths and stranding of surrounding orbital fat on orbital imaging | IV methylprednisolone; topical broad-spectrum antibiotics; topical combination of timolol and dorzolamide; thyrozol and propranolol | Poor recovery due to delayed surgery: improvement of exophthalmos but decreased visual acuity in right eye due to cataract; drug-induced hypothyroidism |

| Stephen et al. 17 | 32/Female | Protrusion of the right eye, orbital pain, and double vision; | Visual acuity in both eyes = 6/6, exophthalmometer reading of 24 mm in the right eye and 20 mm in the left eye measured at 100 mm | Hyperthyroidism; features of PNET (MIC-2 gene positive) on biopsy and immunohistochemistry | The irregular mass lesion in the right orbit without bone erosion in CT; bulkiness in all 4-rectus muscles | En bloc excision of the lesion | Complaints gradually subsided with only minimal eye pain and no diplopia |

| Our case | 25/Female | Proptosis of the right eye; no visual difficulty; weight loss, menstrual irregularities, and occasional palpitations; nonsmoker | Visual acuity in both eyes = 6/6; clinical severity score 3/7; hertel exophthalmometer reading of 23 mm in the right eye and 21 mm in the left eye | Hyperthyroidism with high levels of FT3, FT4, and low TSH; TRAb positive; normal liver and renal function tests | Unilateral EOM enlargement and enhancement with tendon sparing and relative right proptosis on MRI of orbit | IV methylprednisolone, methimazole | Full recovery |

TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone;TSH-R: Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor; TRAb: Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GD: Graves’ disease; GO: Graves’ ophthalmopathy; TED: thyroid eye disease; EOM: extraocular muscle; CS: cavernous sinus; IOP: intraocular pressures; CCF: carotid cavernous fistula; CT: computerized tomography; PNET: primitive neuroectodermal tumor, OD: oculus dexter (right eye); OS: oculus sinister (left eye); IV: intravenous.

Conclusion

This clinical case is a diagnostic challenge because the true unilateral disease is rare, and bilateral asymmetric eye involvement is seen in GO. Numerous differential diagnoses should be considered and studied before diagnosing this uncommon entity, even though noticeable unilateral proptosis supports the atypical presentation of GO in GD. The patient’s response to treatment medications suggests that timely therapy is crucial for reversing the ocular manifestation of TED.

Acknowledgments

The authors do not have any acknowledgment to report for this article.

Footnotes

Author contributions: H.B.B., I.T., and S.D. wrote, reviewed, and edited the original article. P.B.S., M.B., B.P., S.K., S.L., S.G., and B.B. reviewed and edited the original article.

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Madhur Bhattarai  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6382-1082

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6382-1082

References

- 1. Strianese D, Piscopo R, Elefante A, et al. Unilateral proptosis in thyroid eye disease with subsequent contralateral involvement: retrospective follow-up study. BMC Ophthalmol 2013; 13(1): 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arslan E, Yavaşoǧlu I, Çildaǧ BM, et al. Unilateral optic neuropathy as the initial manifestation of euthyroid graves’ disease. Intern Med 2009; 48(22): 1993–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel A, Yang H, Douglas RS. A new era in the treatment of thyroid eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2019; 208: 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lacorzana J, Rocha-de-Lossada C, Ortiz-Perez S. A tricky case of unilateral orbital inflammation: carotid cavernous fistula in Graves-Basedow disease. Rom J Ophthalmol 2021; 65(2): 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Celik O, Buyuktas D, Islak C, et al. The association of carotid cavernous fistula with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol 2013; 61(7): 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(8): 726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boddu N, Jumani M, Wadhwa V, et al. Not all orbitopathy is Graves’: discussion of cases and review of literature. Front Endocrinol 2017; 8: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forbes G, Gorman CA, Brennan MD, et al. Ophthalmopathy of Graves’ disease: computerized volume measurements of the orbital fat and muscle. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1986; 7(4): 651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Topilow NJ, Tran AQ, Koo EB, et al. Etiologies of proptosis: a review. Intern Med Rev 2020; 6(3): 10.18103/imr.v6i3.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Panagiotou G, Perros P. Asymmetric Graves’ orbitopathy. Front Endocrinol 2020; 11: 985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boddu N, Jumani M, Wadhwa V, et al. Not all orbitopathy is Graves’: discussion of cases and review of literature. Front Endocrinol 2017; 8: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rubinstein TJ. Thyroid eye disease following COVID-19 vaccine in a patient with a history Graves’ disease: a case report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2021; 37(6): e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Men CJ, Kossler AL, Wester ST. Updates on the understanding and management of thyroid eye disease. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 2021; 13: 251584142110277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michigishi T, Mizukami Y, Shuke N, et al. An autonomously functioning thyroid carcinoma associated with euthyroid Graves’ disease. J Nucl Med 1992; 33(11): 2024–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lacorzana J, Rocha-de-Lossada C, Ortiz-Perez S. A tricky case of unilateral orbital inflammation: carotid cavernous fistula in Graves-Basedow disease. Rom J Ophthalmol 2021. ; 65(2): 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Macovei ML, Azis Ű. A case report of a patient with severe thyroid eye disease. Rom J Ophthalmol 2022; 66(2): 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stephen MA, Ahuja S, Jayasri P, et al. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the orbit in Graves’ ophthalmopathy – a rare presentation. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2023; 37(1): 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]