Abstract

Objective

Urinary incontinence (UI) is highly prevalent in antenatal and postnatal women while the prevalence of UI varied largely from 3.84% to 38.65%. This study was to assess the prevalence of UI, the associated factors, and the impact of UI on daily life in pregnant and postpartum women in Nanjing, China.

Methods

The prevalence of UI and the impact of UI on life were assessed by the validated Chinese version of International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence-short form and the validated Chinese version of urinary incontinence quality of life. The associated factors were estimated by using logistic regression analysis.

Results

UI affected 37.80% of pregnant women and 16.41% of postpartum women of the study population. Among the pregnant participants, the prevalence rates of stress UI, urge UI, and mixed UI were 25.77%, 4.47%, and 7.10%, respectively. Among the postpartum women, the prevalence rates of stress UI, urge UI, and mixed UI were 11.15%, 1.92%, and 2.69%, respectively. In both pregnant women and postpartum women, vaginal delivery had significantly increased the odds of reporting UI (p=0.007, p=0.003, respectively). The impact of UI on daily life was significantly greater in postpartum women compared to pregnant women especially in social embarrassment (p=0.000).

Conclusion

The prevalence rates of UI were high in pregnant women in Nanjing, China. Vaginal delivery significantly increased odds of reporting UI. UI has a great impact on pregnant and postpartum women's life, especially in social embarrassment.

Keywords: Postpartum women, Pregnant women, Prevalence, Risk factor, Urinary incontinence

1. Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine [1]. UI is prevalent in women, with prevalence ranging from 5% to 69% worldwide [2]. There are many risk factors for UI including age, body mass index, parity, and vaginal delivery [3]. The epidemiological evidence suggests that women who experienced pregnancy and delivery, especially vaginal delivery, are at increased risk of developing UI [4]. Many factors may be associated with UI during pregnancy including changes in hormone levels, increased abdominal pressure from the enlarging uterus and the pressure on pelvic floor muscle from the fetus [5]. The prevalence of UI was reported to be 26.7% during pregnancy and 9.5% at 6 weeks postpartum in China in 2009 [6]. However, the prevalence of UI varies from 7.73% [7] to 36.00% [8] in pregnant women and from 3.84% [9] to 38.65% [10] in postpartum women in different cities in China. Until now, only a 2009 master's thesis [8] reported the prevalence of UI in Nanjing, which is the capital city of Jiangsu Province in China with a population of approximately eight million people [11]. The study reported a prevalence of UI in pregnant women and postpartum women in Nanjing of 36.0% and 14.4%, respectively, which was conducted in 2009, and did not assess the impact of UI on women's quality of life (QoL) [8].

UI was found to have a great impact on women's QoL including social activities, physical exercises, and sexual relationships [12]. Pregnant women with UI have a significantly lower QoL than women without UI, and QoL worsens as gestational age increases [13]. Therefore, it is essential to assess the impact of UI on women's QoL as well as the prevalence and risk factors associated with UI.

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of UI, associated factors and the impact of UI on QoL in pregnant and postpartum women in Nanjing, China.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Design

This study was a population-based cross-sectional study. This study was part of a feasibility randomized controlled trial which aimed to assess the feasibility of delivering group-based pelvic floor muscle training programs to pregnant women in Nanjing, China. Therefore, the findings from the questionnaire-based phase of the study are presented.

2.2. Population and sample size

This study was conducted at Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, which is one of the biggest gynecology and obstetrics hospitals in Nanjing. The sample size was calculated according to the prevalence of UI in China obtained by Zhu et al. [6]. A 95% confidence interval, 4% degree of error allowance, and 30% estimated refusal rate were applied in this survey. A minimum sample size of 780 in each group was required based on the above data.

2.3. Recruitment and selection of participants

The pregnant and postpartum women were approached by midwives and screened to determine whether they were eligible to take part in the study against pre-determined criteria (Section 2.4) when they attended the prenatal clinic or postnatal clinic after delivery. Eligible participants were provided with a copy of information sheet and the survey questionnaire. Both digital and paper questionnaires were available for the participants. Participation was entirely voluntary and returning the completed survey implied consent to the study. The final participating sample was self-selected.

2.4. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

For pregnant women, inclusion criteria included: (1) attending routine antenatal care in Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital; (2) aged 18 years and over; (3) after 16 gestational weeks; (4) no obstetric risk factors; (5) no pelvic surgery history; (6) Nanjing residents. Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of UI before pregnancy; (2) history of urological surgery or obstetric surgery; (3) pregnancy complications; (4) lower urinary tract infection.

For postpartum women, inclusion criteria were: (1) attending the 42-day routine postnatal examination in Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital; (2) aged 18 years and over; (3) Nanjing residents. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of urological surgery or obstetric surgery; (2) lower urinary tract infection.

2.5. Data collection

Data collection was conducted by midwives who were initially trained by the principal researcher (Yang X). Both pregnant and postpartum women were asked by their midwives to scan the code on the questionnaire and answered the questions on mobile phones or other mobile devices at their own convenience. The code was also displayed on the wall outside the midwives’ office in the clinic, which participants could scan. Participants could choose to take a paper questionnaire home and then return the completed questionnaire and submit this in a secure drop box in the reception area of the hospital, although no women in this study chose to participate in this way.

The questionnaire used in this survey included demographic and obstetric history, the validated Chinese version of International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence-short form (ICIQ-UI-SF), and the validated Chinese version of UI QoL (I-QoL). A knowledge, attitude, and practice questionnaire on pelvic floor muscle training was also included in this survey, and the results will be analyzed and presented in another report. The two validated outcome measures both have good psychometric properties [14,15]. The ICIQ-UI-SF consists of four questions. The first question is to assess the perceived cause of UI, which is a self-diagnostic question. The other three scored items are to assess frequency, severity, and perceived impact of UI, respectively [14]. The scores from the three scored items were added to obtain a sum score. The sum score ranges between 3 and 21 with higher scores indicating worse symptoms. The ICIQ-UI-SF defines scores from 1 to 7 as light impact, 8 to 13 as moderate impact, and 14 to 21 as severe impact [14]. The I-QoL consists of 22 items which all use a five-point scale. The sum score ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating a better QoL [15].

2.6. Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the overall prevalence of UI. The secondary outcomes were the prevalence of subtypes of UI, determined by ICIQ-UI-SF responses alone, including stress UI (SUI), urgency UI (UUI), and mixed UI (MUI), the associated factors, as well as the impact of UI on the QoL. The definition of UI used in this study was consistent with the International Urogynecological Association/the International Continence Society joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction [16].

2.7. Statistical analyses

SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis in this study. Categorical variables were presented by frequencies and percentages while means and standard deviations were used to summarize continuous variables. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the relationships between UI and nominal or ordinal sociodemographic characteristics, while Mann-Whitney U test was employed to evaluate the relationships between UI and continuous data. The characteristics which were found to be statistically associated with UI (p<0.05) were then entered into a logistic regression model. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent factors associated with UI. The results in logistic regression models were presented as crude odds ratio and adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. A p-value of 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

2.8. Ethical approval

This study was approved by Jiangsu Provincial Commission of Health (No. WJZ202014). Ethical approval was granted by Committee of King's College London (No. LRS-19/20-11016) and Committee of Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital (No. KY-028). Participants were informed before they received the questionnaire and returning the completed survey implied consent to the study.

3. Results

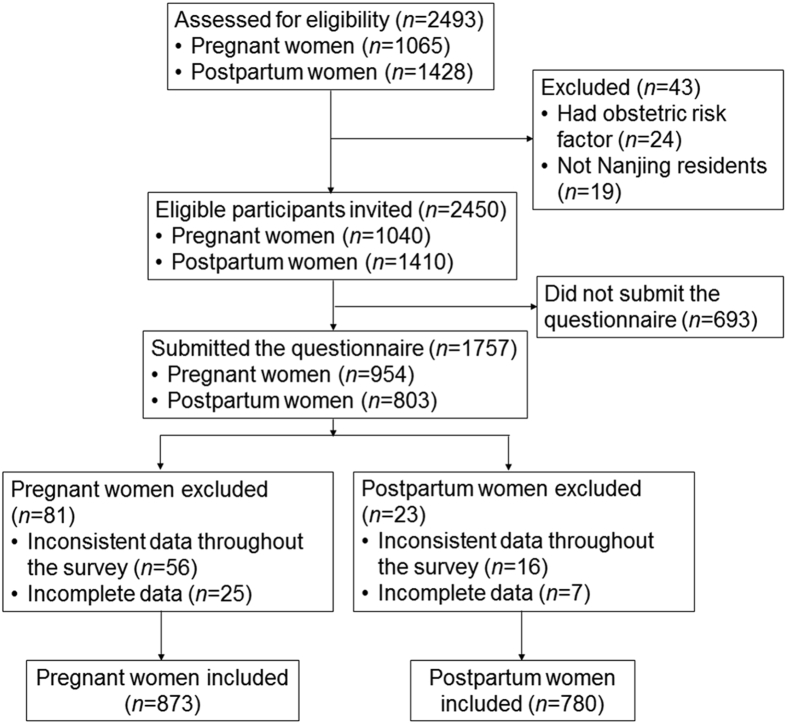

From June 2020 to September 2020, 2450 eligible women were invited to participate in the study and 1757 (71.71%) women submitted the questionnaire with a response rate of 91.73% (954/1040) in pregnant women and 56.95% (803/1410) in postpartum women. In total, 873 respondents of pregnant women and 780 respondents of postpartum women were included in the analysis after eliminating the unqualified questionnaires in which answers were incomplete or inconsistent throughout. The study flow chart is presented in Fig. 1. The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Characteristic | Pregnant women (n=873) | Postpartum women (n=780) |

|---|---|---|

| Agea, year | ||

| 18–20 | 1 (0.11) | 0 |

| 21–25 | 72 (8.25) | 75 (9.62) |

| 26–30 | 443 (50.74) | 367 (47.05) |

| 31–35 | 288 (32.99) | 261 (33.46) |

| 36–40 | 59 (6.76) | 64 (8.21) |

| Above 40 | 10 (1.15) | 13 (1.67) |

| Educationa | ||

| Primary school or below | 1 (0.11) | 2 (0.26) |

| Junior or senior school | 78 (8.93) | 29 (3.71) |

| University | 637 (72.97) | 547 (70.13) |

| Postgraduate or above | 157 (17.98) | 202 (25.90) |

| Job typea | ||

| Mental labor | 605 (69.30) | 545 (69.87) |

| Physical labor | 13 (1.49) | 16 (2.05) |

| Other | 255 (29.21) | 219 (28.08) |

| Body mass index, mean±SD, kg/m2 | 21.25±3.06 | 21.08±2.86 |

| Gestational weeks or weeks after delivery, ±SD | 35.8±4.22 | 8.8±1.8 |

| Gestational stagea | ||

| The first trimester | 9 (1.03) | NA |

| The second trimester | 42 (48.11) | NA |

| The third trimester | 822 (94.16) | NA |

| Time after delivery, week | ||

| 1–3 | NA | 35 (4.49) |

| 4–5 | NA | 77 (9.87) |

| 6–8 | NA | 318 (40.77) |

| 9–10 | NA | 288 (36.92) |

| Above 11 | NA | 62 (7.95) |

| Number of deliveries | ||

| Nulliparous | 531 (60.82) | 509 (65.26) |

| Given birth more than once | 342 (39.18) | 271 (34.74) |

| Parity, ±SD | 1.53±0.76 | 1.5±0.7 |

| Women had family history of urinary incontinencea | 12 (1.37) | 26 (3.33) |

| Women experienced vaginal deliverya | 137 (15.69) | 372 (47.69) |

| Smokea | ||

| 0 | 870 (99.66) | 776 (99.49) |

| 1 to 3 cigarettes a week | 2 (0.23) | 1 (0.13) |

| 4 to 6 cigarettes a week | 0 | 0 |

| 1 to 2 cigarettes a day | 0 | 0 |

| 3 to 5 cigarettes a day | 1 (0.11) | 1 (0.13) |

| 6 to 10 cigarettes a day | 0 | 1 (0.13) |

| Above 10 cigarettes a day | 0 | 1 (0.13) |

| Alcohol intakea | ||

| 0 | 871 (99.77) | 775 (99.36) |

| 1 to 3 glasses a week | 1 (0.11) | 2 (0.26) |

| 4 to 6 glasses a week | 0 | 2 (0.26) |

| 1 to 2 glasses a day | 0 | 0 |

| 3 to 5 glasses a day | 0 | 0 |

| 6 to 10 glasses a day | 1 (0.11) | 0 |

| Above 10 glasses a day | 0 | 1 (0.13) |

| Coffee intakea | ||

| 0 | 825 (94.50) | 703 (90.12) |

| 1 to 3 cups a week | 43 (4.93) | 57 (7.30) |

| 4 to 6 cups a week | 0 | 10 (1.28) |

| 1 to 2 cup a day | 4 (0.46) | 8 (1.03) |

| 3 to 5 cup a day | 0 | 1 (0.13) |

| Above 5 cup a day | 1 (0.11) | 1 (0.13) |

SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable.

Values are presented as n (%).

Of the 873 pregnant women and 780 postpartum women included in the analysis, 50.74% of the pregnant women and 47.05% of the postpartum women were aged between 26 and 30 years. Almost 72.97% of the pregnant women and 70.13% of the postpartum women had graduated with a diploma or a degree. The pregnant women who participated in the study were mainly at their third trimester of pregnancy (94.16%). While postpartum women were mainly in their 6th to 8th weeks after delivery (40.77%). Of the pregnant women, 60.82% were nulliparous while 34.74% of the postpartum women had given birth more than once. Most of the pregnant women (98.63%) and the postpartum women (96.67%) had no family history of UI. Only 15.69% of the pregnant women had an experience of vaginal delivery.

The distribution of SUI, UUI, MUI, and other types of UI are presented in Table 2. UI affected 37.80% (330/873) pregnant women and 16.41% (128/780) postpartum women of the study population. Among the pregnant participants, the prevalence of SUI, UUI, and MUI was 25.77%, 4.47%, and 7.10%, respectively. Among the postpartum women, the prevalence of SUI, UUI, and MUI was 11.15%, 1.92%, and 2.69%, respectively. SUI was the most common subtype of UI in both pregnant women and postpartum women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence rates of SUI, UUI, MUI, other types of UI, and UI.

| Type | Participant, n (%)a | Women who have UI symptoms, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUI | |||

| Pregnant | 225 (25.77) | 225 (68.18) | |

| Postpartum | 87 (11.15) | 87 (67.97) | |

| UUI | |||

| Pregnant | 39 (4.47) | 39 (11.82) | |

| Postpartum | 15 (1.92) | 15 (11.72) | |

| MUI | |||

| Pregnant | 62 (7.10) | 62 (18.79) | |

| Postpartum | 21 (2.69) | 21 (16.41) | |

| Other types of UI | |||

| Pregnant | 4 (0.46) | 4 (1.21) | |

| Postpartum | 5 (0.64) | 5 (3.91) | |

| UI | |||

| Pregnant | 330 (37.80) | NA | X2=98.883; p=0.000 |

| Postpartum | 128 (16.41) | NA | |

UI, urinary incontinence; SUI, stress UI; UUI, urgency UI; MUI, mixed UI; NA, not applicable.

The number of pregnant women and postpartum women is 873 and 780, respectively.

The frequency of UI and the volume of leakage are presented in Table 3. There were 22.80% of the pregnant women reporting urine leakage once a week or less and 37.23% of the pregnant women reported they leaked only a small amount of urine. The ICIQ score ranged from 0 to 15 among the pregnant women with symptoms of UI and the mean score was 2.24 (standard deviation [SD]: 3.11). The mean score in postpartum women was 7.20 (SD: 2.88), which was significantly higher than that in pregnant women (p=0.000). According to the ICIQ score, the level of impact of UI on life in postpartum women was significantly different from pregnant women (p=0.000). About eighty percent (83.03%, 274/330) of the pregnant women thought that it had a light impact overall while 60.16% (77/128) of the postpartum women with UI thought it had a light impact on their life. About 35.16% (45/128) of the postpartum women compared to 15.76% of pregnant women (52/330) thought the symptom of UI had a moderate impact on their life. According to the information from the I-QoL instrument, QoL was negatively affected in three domains including social embarrassment, avoidance and limiting behavior, and psychosocial impacts. Among all these sub-domains, the scores in social embarrassment were the lowest in both pregnant and postpartum women (Table 3). The I-QoL score, social embarrassment score, and avoidance and limiting behavior score in pregnant women were significantly higher than those in postpartum women (p=0.000); and the psychosocial impacts score in pregnant women was significantly higher than that in postpartum women (p=0.034) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The results from ICIQ-UI-SF and I-QoL score.

| ICIQ-UI-SF and I-QoL questions | Pregnant | Postpartum | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence episodesa | X2=99.721; p=0.000 | ||

| Never | 543 (62.20) | 552 (70.77) | |

| About once a week or less often | 199 (22.80) | 168 (21.54) | |

| Two or three times a week | 88 (10.08) | 38 (4.87) | |

| About once a day | 26 (2.98) | 16 (2.05) | |

| Several times a day | 15 (1.72) | 3 (0.38) | |

| All the time | 2 (0.23) | 3 (0.38) | |

| Amount of leakagea | X2=286.729; p=0.000 | ||

| None | 543 (62.20) | 552 (70.77) | |

| Small | 325 (37.23) | 77 (9.87) | |

| Moderate | 5 (0.57) | 145 (18.59) | |

| Severe | 0 | 6 (0.77) | |

| Perceived impact of those reporting UI, mean±SD | 0.78±1.63 | 3.00±0.00 | Z=−8.079; p=0.000; |

| ICIQ-UI-SF score, mean±SD | 2.24±3.11 | 7.20±2.88 | Z=−8.580; p=0.000 |

| Impact on life (women who have the symptoms of UI)a | X2=31.253; p=0.000 | ||

| Light | 274 (83.03) | 77 (60.16) | |

| Moderate | 52 (15.76) | 45 (35.16) | |

| Severe | 4 (1.21) | 6 (4.69) | |

| Social embarrassment score, mean±SD | 96.55±6.43 | 95.75±9.05 | Z=−9.542; p=0.000 |

| Avoidance and limiting behavior score, mean±SD | 97.20±6.75 | 96.09±6.35 | Z=−4.000; p=0.000 |

| Psychosocial impact score, mean±SD | 97.74±5.34 | 96.76±6.82 | Z=−7.413; p=0.034 |

| I-QoL score, mean±SD | 97.27±5.52 | 96.29±6.57 | Z=−10.443; p=0.000 |

ICIQ-UI-SF, the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence-short form; I-QoL, urinary incontinence quality of life; UI, urinary incontinence; SD, standard deviation.

Values are presented as n (%).

Comparing all pregnant and postpartum women irrespective of UI, significant differences were found in family history of UI and experience of vaginal delivery in pregnant women (p=0.031, p=0.003, respectively) as well as parity and experience of vaginal delivery in postpartum women (p=0.058, p=0.002, respectively). These four factors were included in the logistic binary regression analysis. It was shown that in both pregnant women and postpartum women, the only significant factor was vaginal delivery which had significantly increased odds of reporting UI (p=0.007, p=0.003, respectively). A family of history in pregnant women and parity in postpartum women were not significantly associated with higher odds of UI after adjustment for confounders (p=0.057, p=0.073, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of associated factors in pregnant women and postpartum women.

| Risk factor | cOR |

aOR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | p-Value | Median (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Pregnant women | ||||

| Family history of UI | 4.256 (1.144–15.830) | 0.031 | 3.627 (0.963–13.654) | 0.057 |

| Experience of vaginal delivery | 1.734 (1.202–2.503) | 0.003 | 1.669 (1.153–2.417) | 0.007 |

| Postpartum women | ||||

| Parity | 1.264 (0.992–1.610) | 0.058 | 1.251 (0.980–1.599) | 0.073 |

| Experience of vaginal delivery | 1.827 (1.242–2.688) | 0.002 | 1.810 (1.229–2.665) | 0.003 |

cOR, crude odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; UI, urinary incontinence; CI, confidence interval.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to assess the prevalence of UI in Nanjing, China within the last 10 years. The prevalence rates of UI in pregnant women and postpartum women in this study were consistent with previous data from Nanjing, China in 2009 [8]. However, it is not possible to directly compare the prevalence of UI to the other cities in China due to different definitions of UI and different questionnaires employed in other published studies. In addition, published studies assessed the prevalence of UI in different stages during pregnancy or postpartum period (Supplementary Table 1). The prevalence of UI in postpartum women was significantly lower than that in pregnant women. The possible reason might be removal of the pressure from the fetus to the pelvic floor muscles and the natural recovery of the levator ani muscle [17]. The proportions of women reporting different subtypes of UI including SUI, UUI, and MUI in this study are in line with those reported in other studies, with SUI reported to be the most common type of UI in both pregnant and postpartum women [18,19,20]. The pregnant women included in this study were mainly after 28 gestational weeks and the postpartum women were invited in this study at the 42-day postpartum clinic; therefore, the included postpartum women were mainly at their 6th to 8th week after delivery. One possible reason for increased proportions of pregnant women completing the survey after 28 gestational weeks was that compared to women who were in their second trimester, women have increased risks of experiencing UI in their third trimester [17]; therefore, they may have more interest in participating in the study.

In this study, it was found that most of the participants had a university degree or above. In addition, only a small portion of the pregnant women and postnatal women smoked, drank alcohol or coffee. This suggests that the pregnant and postpartum women with high level of education who took part in the study lead a healthy lifestyle in relation to these behaviors. It was interesting that only 47.70% of postpartum women had experienced a vaginal delivery in Nanjing which is the capital city of Jiangsu province. In China, the cesarean delivery (CD) rate had increased to estimates of 40%–50%, with rates as high as 70% in some urban areas in 2009 [21]. However, about 10%–28% of all CD had reportedly been driven by maternal request instead of medical indication in 2008 [22]. The possible reasons included anxiety about labor, choice of a specific delivery date, fear of pain, or demand of a “perfect” birth outcome [23]. The CD rates have been declining with the implementation of training of healthcare providers and tightening of hospital regulations [24]. However, the one-child policy has been relaxed since 2007; as a result, the change of policy increased the deliveries of older women and women with previous CD which may have had impact on decisions about the method of delivery [25]. It was reported that the CD rate was 48.80% in Jiangsu Province [26]. In addition, it was found in Jiangsu Province that CD was more prevalent among more affluent women and women living in urban areas [27] which is consistent with the findings of this study.

It was found that UI had a great impact on women's QoL, and the impact was greater in postpartum women than it was in pregnant women. Most of the pregnant and postpartum women with UI symptoms both leaked urine once a week or less often, but the amount of moderate urine leakage in postpartum women (18.59%) was significantly higher than that in pregnant women (0.57%). The significant difference in amount of urine leakage may be one of the reasons for higher ICIQ score and lower I-QoL score in postpartum women. This may also be explained by many pregnant women believing UI was a common symptom with pregnancy and therefore did not consider this to be too serious [28]. However, when women found the symptom of UI persisted after delivery, they may find this symptom had a greater impact on their daily life which may contribute to lower I-QoL score in postpartum women in this study.

A lot of factors are known to be associated with an increased likelihood of UI, for example, age, parity, family history of UI, and vaginal delivery [3]. In this study, after adjusting for confounders, it was found that an experience of vaginal delivery was the only factor significantly associated with a greater likelihood of UI in both pregnant and postpartum women, which was consistent with previous studies [29,30]. Although the link between the development of UI and vaginal delivery remains unclear, it was reported the muscle stretching during vaginal delivery has an adverse effect on the sphincter including intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, which may lead to UI [31].

Strengths of this study included a large sample size, high response rate, the questionnaire used in this study that was validated to assess the prevalence of UI, and the impact on life of UI. Another strength of the study is that the questionnaires were completed anonymously instead of via face-to-face interview; therefore, the participants were not hesitant to disclose the symptom of UI.

A limitation of this study is pregnant participants were mainly in their third trimester of pregnancy. Further study on prevalence of UI in early and middle trimester of pregnancy needs be carried out to assess the overall prevalence of UI in pregnant women. Another limitation is that most of the participants in this study had a university degree or above. This may be representative of a city population, but this cannot be generalized to the whole population in China. In addition, the subtypes of UI were not confirmed by other examinations which would have improved the reliability of data. However, the questionnaires were self-reported and anonymous; therefore, it was not possible to confirm the subtypes of UI. This limitation could be mitigated through the use of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence-short form, a validated tool widely used in assessing the prevalence of UI and the subtypes of UI. Finally, the participants were self-selecting which may skew the data because women with symptoms of UI were more likely to fill in the questionnaires. However, the response rate in this study was high and the sample size was considered large enough to minimize the effect which a self-selecting questionnaire brings.

5. Conclusion

The prevalence rates of UI in both pregnant and postpartum women are high in Nanjing, China and have a negative impact on women's QoL. An experience of vaginal delivery was found to be significantly associated with UI during both pregnancy (for multiparous women) and the postpartum period. In this affluent and well-educated urban population, the rate of caesarean section is also higher than that normally considered necessary. Epidemiological studies on prevalence of UI in pregnant women during the whole pregnancy and postpartum period in the long-term need to be conducted. Further secondary prevention trials are needed to investigate how to help pregnant and postpartum women to prevent UI or improve their experience of UI symptoms.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Xiaowei Yang, Sue Woodward.

Data acquisition: Xiaowei Yang.

Data analysis: Xiaowei Yang, Sue Woodward, Lynn Sayer, Sam Bassett.

Drafting of manuscript: Xiaowei Yang.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Xiaowei Yang, Sue Woodward, Lynn Sayer, Sam Bassett.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Tongji University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2022.03.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Multimedia component 1

References

- 1.D'Ancona C., Haylen B., Oelke M., Abranches-Monteiro L., Arnold E., Goldman H., et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:433–477. doi: 10.1002/nau.23897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammad F.T. Prevalence, social impact and help-seeking behaviour among women with urinary incontinence in the Gulf countries: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;266:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukacz E.S., Santiago-Lastra Y., Albo M.E., Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318:1592–1604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodley S.J., Lawrenson P., Boyle R., Cody J.D., Morkved S., Kernohan A., et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD007471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristiansson P., Samuelsson E., von Schoultz B., Svardsudd K. Reproductive hormones and stress urinary incontinence in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1125–1130. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu L., Li L., Lang J.H., Xu T. Prevalence and risk factors for peri- and postpartum urinary incontinence in primiparous women in China: a prospective longitudinal study. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:563–572. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Q., Cao J., Liu L., Ye L. [The prevalence and associated risk factors of urinary incontinence in pregnant and postnatal women in Wuhan city] Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2016;31:598–599. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y. Southeast University; 2009. [The prevalence of UI and associated factors towards UI in pregnant women and postpartum women] [D] [Thesis in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang M. Shanxi Medical University; Taiyuan: 2011. [Shanxi Jinzhong incontinence of primiparous women in epidemiological studies] [D] [Thesis in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng J., Lin S., Huang P., Chen J., Chen S., Xie Y. [Epidemiological investigation on female stress urinary incontinence at 42 days after delivery] Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2017;20:5103–5106. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Bureau of Jiangsu Province http://stats.jiangsu.gov.cn/2019/nj03.html Gross domestic product by cities.

- 12.Sensoy N., Dogan N., Ozek B., Karaaslan L. Urinary incontinence in women: prevalence rates, risk factors and impact on quality of life. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2013;29:818–822. doi: 10.12669/pjms.293.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Pol G., van Brummen H.J., Bruinse H.W., Heintz A.P., van der Vaart C.H. Is there an association between depressive and urinary symptoms during and after pregnancy? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1409–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L., Zhang S.W., Wu S.L., Ma L., Deng X.H. The Chinese version of ICIQ: a useful tool in clinical practice and research on urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:522–524. doi: 10.1002/nau.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X.Q. Peking Union Medical College; 2013. [Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the MBIS, I-QOL and UFS-QOL in patients with POP, urinary incontinence and uterine fibroid] [D] [Thesis in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haylen B.T., de Ridder D., Freeman R.M., Swift S.E., Berghmans B., Lee J., et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:5–26. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sangsawang B., Sangsawang N. Stress urinary incontinence in pregnant women: a review of prevalence, pathophysiology, and treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:901–912. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H., Ye Z., Chen S., Zhuang Y., Gu Q., Lin L. [The prevalence and risk factors associated with stress urinary incontinence in pregnant women] J Fujian Med Univ. 2016;50:3. [Article in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Cheng F., Wang H., Zhu Y. Risk factors associated with stress urinary incontinence in postpartum women. Pract Prev Med. 2020;27:1489–1491. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds W.S., Dmochowski R.R., Penson D.F. Epidemiology of stress urinary incontinence in women. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:370–376. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-04/17/content_1288030.htm The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China. Overview of administrative divisions in China.

- 22.Zhang J., Liu Y., Meikle S., Zheng J.C., Sun W.Y., Zhu L. Cesarean delivery on maternal request in southeast China. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1077–1082. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816e349e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang S., Li X., Wu Z. Rising cesarean delivery rate in primiparous women in urban China: evidence from three nationwide household health surveys. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1527–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang J., Mu Y., Li X., Tang W., Wang Y., Liu Z., et al. Relaxation of the one child policy and trends in caesarean section rates and birth outcomes in China between 2012 and 2016: observational study of nearly seven million health facility births. BMJ. 2018;360:k817. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng P.J., Duan T. China's new two-child policy: maternity care in the new multiparous era. BJOG. 2016;123(Suppl 3):7–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H.T., Luo S., Trasande L., Hellerstein S., Kang C., Li J.X., et al. Geographic variations and temporal trends in cesarean delivery rates in China, 2008–2014. JAMA. 2017;317:69–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan H., Gu H., You H., Xu X., Kou Y., Yang N.C.H. Social determinants of delivery mode in Jiangsu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:473. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2639-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuelsson E., Victor A., Tibblin G. A population study of urinary incontinence and nocturia among women aged 20–59 years. Prevalence, well-being and wish for treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:74–80. doi: 10.3109/00016349709047789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rortveit G., Daltveit A.K., Hannestad Y.S., Hunskaar S., Norwegian E.S. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:900–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X.R., Shi J.X., Zhai G.R., Zhang W.Y. [Postpartum stress urinary incontinence and associated obstetric factors] Chinese J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;45:104–108. [Article in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer S., Schreyer A., De Grandi P., Hohlfeld P. The effects of birth on urinary continence mechanisms and other pelvic-floor characteristics. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:613–618. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1